Introduction

Cervical cancer is a significant global health concern, ranking as the fourth most common cancer among women [

1,

2]. However, the menace can be minimized, because the causative agent is well known to be persistent Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, particularly with high-risk strains such as HPV 16 and 18 been the primary factor driving the progression of this disease [

3]. The virus encodes oncoproteins E6 and E7, which are pivotal in cervical carcinogenesis, exerting their oncogenic effects by inactivating the tumour suppressor protein. These interactions facilitate the evasion of crucial cellular processes that normally regulate growth and apoptosis, thereby driving the malignancy of cervical cells [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Likewise, as carcinogenesis progresses, E6 and E7 remain central to the initiation and advancement of cervical cancer. These oncoproteins induce the six primary hallmarks of cancer, as defined by Hanahan and Weinberg: sustained proliferative signalling, evasion of growth suppressors, resistance to cell death, enabling replicative immortality, induction of angiogenesis, and activation of invasion and metastasis [

7,

8]. Specifically, the E7 oncoprotein was the first to be identified and is known for its ability to bind and inactivate the Rb protein, leading to unchecked cellular proliferation [

9]. Conversely, the E6 protein targets p53 for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, allowing cells to bypass apoptosis and accumulate genomic instability [

8]. Together, these oncoproteins are the driving force behind the progression from HPV infection to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and eventually to invasive cervical cancer [

8,

9].

Given the critical role of E6 and E7 in cervical carcinogenesis, therapeutic strategies aimed at inhibiting these oncoproteins have the potential to halt the progression from HPV infection to invasive cervical cancer. In recent years, phytochemicals have garnered significant attention as promising anticancer agents due to their ability to modulate multiple signalling pathways involved in cancer progression. These naturally occurring compounds, derived from plants, offer a broad spectrum of bioactivities that could be leveraged to target the key drivers of cervical cancer [

10,

11,

12].

In this study, we explored the anticancer potential of seven phytochemicals Capsaicin, Catechins, Lycopene, Benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC), Phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC), Isoflavone, and Piperlongumine against the HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins in cervical cancer. These compounds were selected based on their documented anticancer activities and their potential to target various cancer hallmarks [

13].

We employed a comprehensive in silico approach that included molecular docking to predict binding affinities, ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) predictions to assess pharmacokinetic profiles, and molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate the stability of the protein-ligand complexes. Additionally, visualization of hydrogen bonding and molecular interactions provided insights into the specific interactions between these phytochemicals and the HPV 16 oncoproteins. Our findings contribute to the growing body of research aimed at developing novel therapeutic strategies for cervical cancer by targeting the oncogenic drivers E6 and E7

Materials and Methods

Ligand Preparation

The structures of HPV 16 E6 and E7 inhibitors were obtained from PubChem database in SDF format and were then subjected to geometric refinement using the Schrödinger LigPrep module, which facilitates the conversion of 2D structures into their corresponding 3D formats. This step is essential for ensuring that the ligands are in a suitable conformation for further analysis [

14]. Following this, energy minimization of the ligands was performed using the OPLS_2003 force field. This step is crucial to guarantee that the ligands reach a stable conformation, indicated by a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.00 Å, signifying that the structures are optimized and ready for subsequent analysis [

15,

16]. After energy minimization, the ligand preparation for docking involved using AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 to add hydrogen atoms to the ligands. Non-polar hydrogen atoms were merged, and Gasteiger charges were assigned to prepare the ligands adequately [

17]. This thorough preparation phase ensures that the inhibitors are optimized prior to docking, enhancing the reliability of the subsequent docking studies and the potential identification of effective HPV inhibitors. The prepared ligand was saved in PDBQT format for docking studies.

Protein Preparation

The target proteins in this study were the HPV-16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins. The preparation steps were as follows: HPV-16 E6 Protein: The crystal structure of the HPV-16 E6 protein was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 2LJZ). HPV-16 E7 Protein: The structure of the HPV-16 E7 protein was predicted using the Swiss-Model server due to the absence of a resolved crystal structure in the PDB. The protein structure underwent processing, which involved assigning bond orders, adding hydrogen atoms, creating zero-order bonds to metal ions, filling inside chains, and completing missing loops using the Prime protein structure prediction program (Schrödinger LLC, New York, NY, USA). Subsequently, the protein was energy minimized using the OPLS3 force field. The protein was prepared by loading it into AutoDock Tools 1.5.6, where water molecules were removed, polar hydrogens attached to heteroatoms were added and Kollman charges were assigned to the proteins. Finally, the prepared proteins were then saved in PDBQT format ready for Molecular docking.

Molecular Docking

Blind docking was conducted using AutoDock Vina to identify potential binding sites across the entire protein surfaces. The grid boxes were configured to encompass the whole proteins: HPV-16 E7 Protein: Center_x16.995, Center_y 22.469, Center_z 39.118, Size_x 100, Size_y 100, Size_z 100. HPV-16 E6 Protein: Center_x -47.202, Center_y -38.847, Center_z -43.862, Size_x 94, Size_y 110, Size_z 88. The grid boxes were designed to cover the entire proteins, enabling blind docking. The docking exhaustiveness was set to 8 to ensure thorough sampling. Docking simulations were performed, and the resulting docked poses were ranked based on their binding affinities (kcal/mol). The top binding poses were selected for further analysis.

Pharmacophore Modelling

The key properties contributing to the interaction of the top-scoring compounds with the HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins were elucidated through pharmacophore modelling. Using the Phase tool in Schrödinger Maestro 14.0, an e-pharmacophore hypothesis was generated based on the receptor-ligand complex (Schrödinger Release 2020-4: Phase, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2020). This approach allowed us to identify critical interaction features, including hydrogen bond acceptors and donors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings, which are essential for binding affinity and specificity.

ADMET Predictions

SwissADME Analysis: The SwissADME tool (Daina, Michielin, & Zoete, 2017) was employed to assess various pharmacokinetic properties, including drug-likeness, bioavailability, and potential for gastrointestinal absorption. This tool provided insights into the compounds' molecular properties, lipophilicity, water solubility, pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and medicinal chemistry friendliness (

http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php).

PROTOX-II Analysis: For toxicity predictions, the PROTOX-II web server was utilized (Banerjee et al., 2018). This tool predicted various toxicological endpoints such as hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, respiratory toxicity, cardiotoxicity, immunotoxicity, mutagenicity, and carcinogenicity, among others (

https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/). The results provided an estimation of the compounds' LD50 values, toxicity classes, and potential organ-specific toxicities.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

To gain deeper insights into the stability and dynamic behavior of the capsaicin-HPV oncoprotein complexes, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted. The best-docked poses of capsaicin with HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins were selected for the simulation. The selected protein-ligand complexes were prepared using GROMACS tools, employing the CHARMM36 force field for the proteins, and the CGenFF server to generate parameters for capsaicin.

Each complex was placed in a cubic box with a minimum distance of 10 Å from any edge of the box to the complex and was then solvated using the TIP3P water model. Sodium and chloride ions were added to neutralize the system, with an additional concentration of 0.15 M NaCl to mimic physiological conditions. The systems were subjected to energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm until the maximum force fell below 1000 kJ/mol/nm, removing any steric clashes or bad contacts.

Subsequent equilibration involved an NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for 1 ns at 300 K using the V-rescale thermostat, followed by an NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for 1 ns at 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. The production MD simulations were then carried out for 100 ns, with an integration time step of 2 fs and coordinates saved every 10 ps for analysis. The LINCS algorithm was used to constrain all bond lengths, permitting the use of a larger time step.

The resulting trajectories were analyzed using GROMACS tools. Key parameters analyzed included the root mean square deviation (RMSD) to monitor the structural stability of the complexes over time. We further conducted a pioneering combined molecular dynamics simulation by validation of the system's deformability, NMA mobility, variance, and covariance using the iMODS server. This analysis enables a detailed assessment of the macromolecule's structural dynamics and stability, offering valuable insights into its flexibility and motion patterns.

Results and Discussion

In this study, we aimed to identify potential inhibitors of the HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins through molecular docking and dynamic simulation approaches. A comprehensive virtual screening was conducted on several naturally occurring compounds, namely Capsaicin, Catechins, Lycopene, Benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC), PEITC, Isoflavone, and Piperlongumine, to assess their binding affinity and drug-likeness properties.

Molecular Docking and Binding Energy

The molecular docking results indicated that all tested compounds exhibited favorable binding energies with the HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins, suggesting their potential as effective inhibitors, as summarized in

Table 1. However, binding energy alone is insufficient to designate a compound as a viable drug candidate. Therefore, we further assessed the drug-likeness of these compounds based on established criteria, including Lipinski's, Ghose's, Veber's, Egan's, and Muegge's rules. These rules are commonly employed to predict the oral bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of drug-like molecules, ensuring that the compounds not only bind effectively to their targets but also possess suitable properties for further development as therapeutic agents. In previous studies, it has been demonstrated that effective inhibitors of HPV E6 protein can significantly impact the interaction with tumour suppressor proteins, such as p53, which is crucial in the context of cervical cancer treatment [

16,

18]. The binding energies observed in our docking studies align with findings from other research that highlights the importance of molecular interactions in the efficacy of potential inhibitors [

19,

20]. Moreover, the application of drug-likeness rules serves as a critical step in the drug development pipeline, allowing for the selection of compounds that are more likely to succeed in clinical settings due to their favourable pharmacokinetic profiles [

21]. This comprehensive evaluation shows the necessity of integrating binding affinity with drug-likeness assessments to identify promising candidates for further investigation in HPV-related therapies.

Drug-likeness Analysis

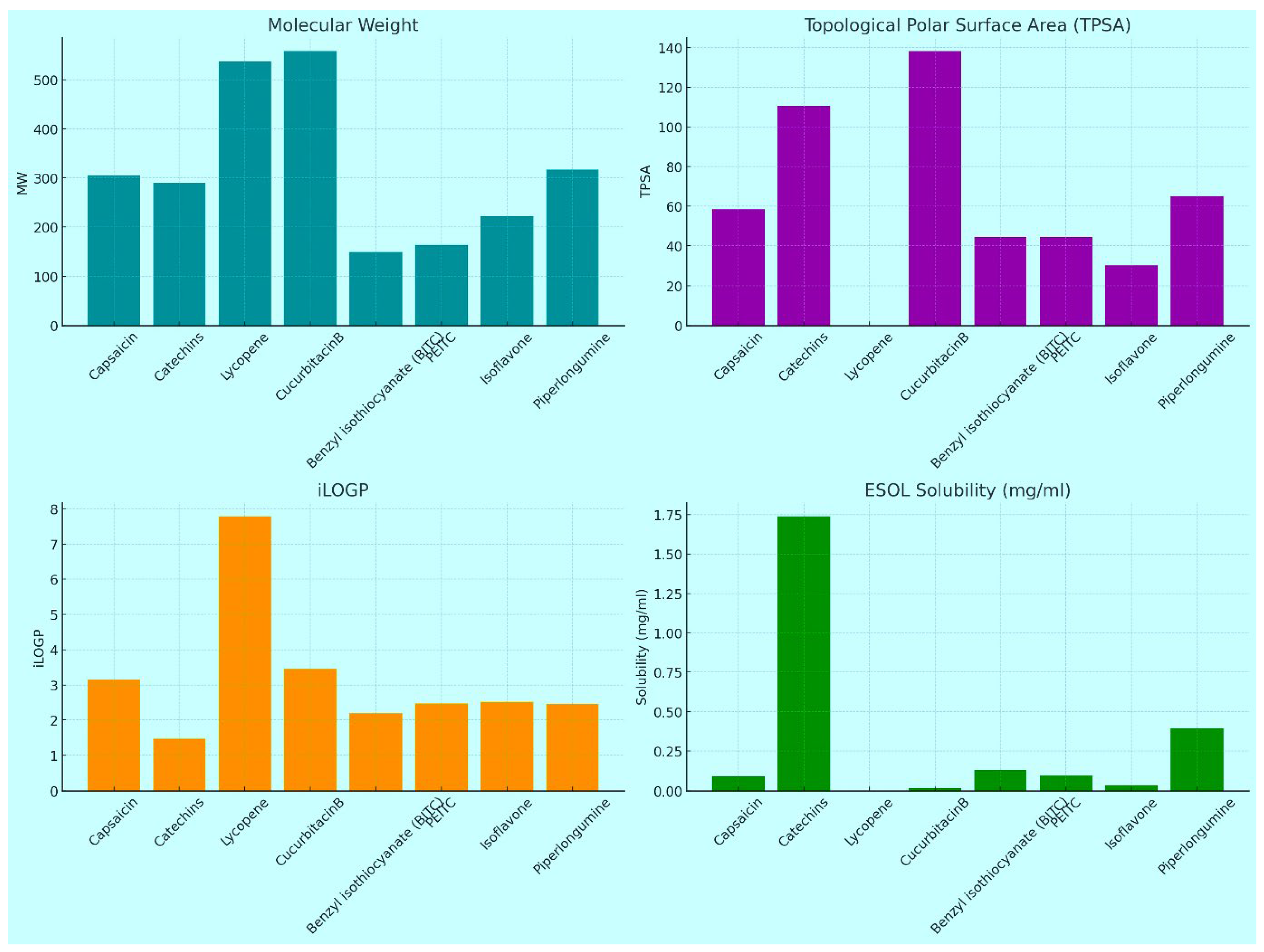

The ADMET study results provide valuable insights into the pharmacokinetic properties of various compounds, highlighting their potential as therapeutic agents. As shown in

Figure 1 most compounds exhibit moderate molecular weights, favouring good absorption and distribution. Notably, Capsaicin and Lycopene have a higher number of heavy atoms, suggesting enhanced interaction with biological targets and improved metabolic stability. Capsaicin also has a higher fraction of sp³ hybridized carbons, which is linked to favourable pharmacokinetic properties, while Lycopene's lower saturation may hinder its solubility and absorption. In terms of solubility, Capsaicin, Catechins, and Benzyl Isothiocyanate show moderate to high solubility, beneficial for absorption, whereas Lycopene's insolubility poses challenges for formulation and bioavailability. The Log P values indicate varying lipophilicity, with Lycopene demonstrating poor aqueous solubility, while lower Log P values in Catechins suggest better solubility. Furthermore, our findings revealed that among the tested compounds, Capsaicin, Catechins, Isoflavone, and Piperlongumine did not violate any of the commonly used drug-likeness rules, such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge criteria [

22,

23,

24]. This suggests that these compounds possess favourable physicochemical properties and are more likely to exhibit good oral bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profiles, making them promising candidates for further investigation as potential HPV 16 E6 and E7 inhibitors. On the other hand, Lycopene, CucurbitacinB, BITC, and PEITC exhibited several violations of these drug-likeness rules as shown

Figure 2. Violations of these rules, which assess parameters like molecular weight, lipophilicity, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and polar surface area, could potentially affect the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of these compounds [

3]. As a result, their bioavailability and efficacy as drug candidates may be compromised. This stringent selection process, which combines molecular docking with drug-likeness evaluation, shows the importance of considering pharmacokinetic properties in the early stages of drug discovery [

25]. By applying these criteria, researchers can focus their efforts on compounds with a higher probability of success, ultimately saving time and resources in the drug development pipeline [

20]. Only compounds with favourable drug-likeness profiles should be considered for further validation through in vitro and in vivo studies.

Interaction with HPV Oncoproteins

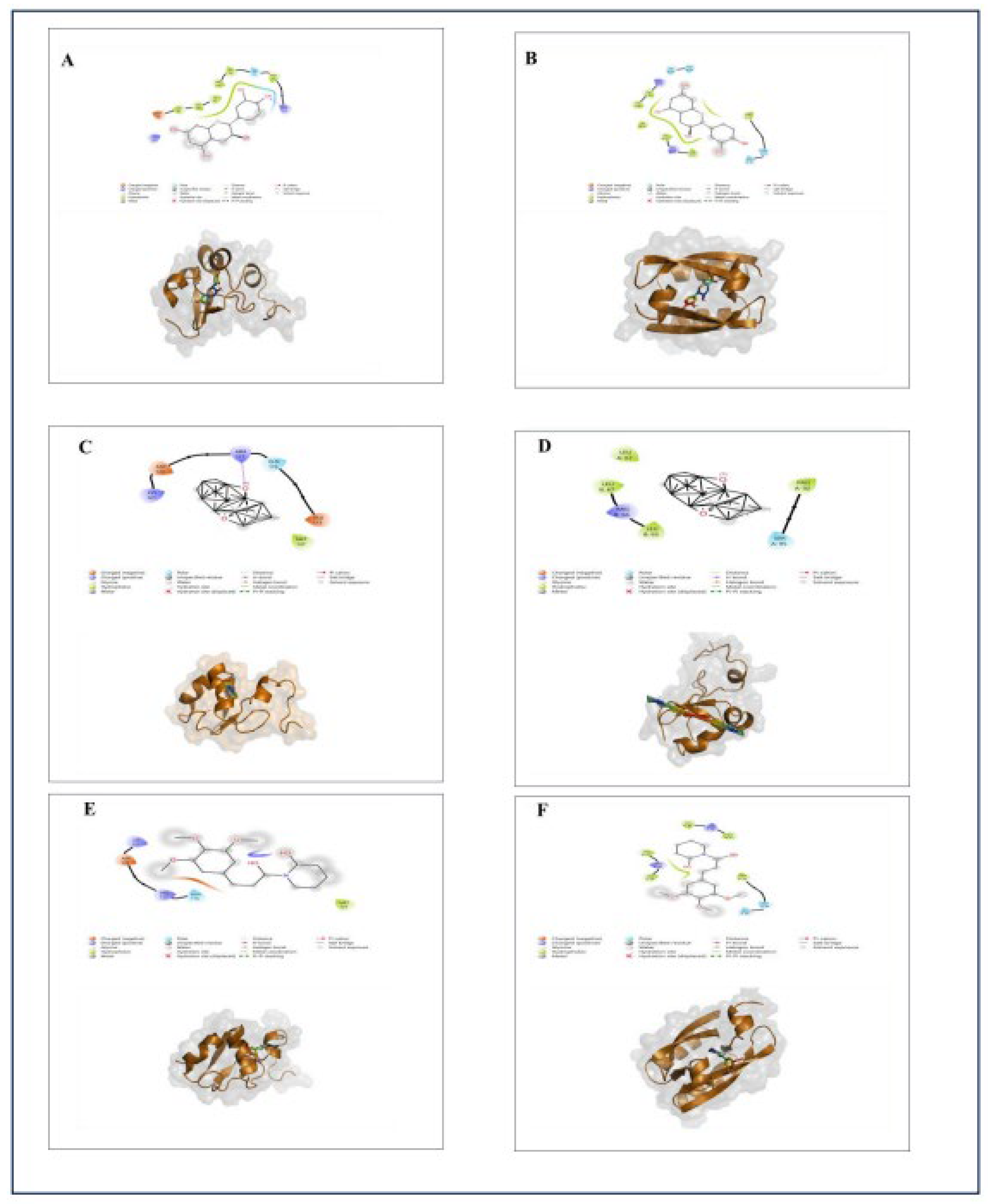

Given the promising drug-likeness profiles of Capsaicin, Catechins, Isoflavone, and Piperlongumine, we further investigated their interactions with the HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins as shown in

Figure 4. Notably, Capsaicin demonstrated a unique ability to form stable hydrogen bond interactions with both oncoproteins, thereby showing its strong and specific binding affinity. Capsaicin formed one hydrogen bond with ASP-98 of the HPV 16 E6 protein and another with PHE-57 of the HPV 16 E7 protein as illustrated in

Figure 3. These amino acids are in the carboxy-terminal regions of the E6 and E7 proteins, which contain crucial motifs essential for their biological functions.

The carboxy-terminal region of the E7 protein includes zinc-binding motifs vital for its structural integrity and dimerization capabilities. This structural configuration allows E7 to interact effectively with cellular proteins involved in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis [

26,

27,

28]. Similarly, the E6 protein interacts with several host proteins, including p53, to promote the degradation of tumor suppressors and evade apoptosis, facilitating the oncogenic process.

Inhibiting the activity of E6 and E7 at their carboxy-terminal regions could disrupt these critical interactions, potentially restoring normal cell cycle control and apoptosis mechanisms. This mechanism of action positions Capsaicin as a promising candidate for therapeutic intervention in HPV-related cervical cancer. Capsaicin's interaction with the ASP-98 of E6 and PHE-57 of E7 is particularly significant, as these residues are integral to the oncoproteins' ability to hijack host cellular machinery.

Research indicates that targeting E6 and E7 can lead to significant therapeutic outcomes. For instance, ribozyme targeting of HPV16 E6 and E7 transcripts has been shown to suppress cell growth and enhance sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in cervical cancer cells [

8,

28]. Furthermore, understanding the pathways modulated by E6 and E7 can aid in identifying potential biomarkers for early detection and treatment response. These oncoproteins are involved in dysregulating various cellular pathways, including those related to DNA damage response and immune evasion [

8,

27].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

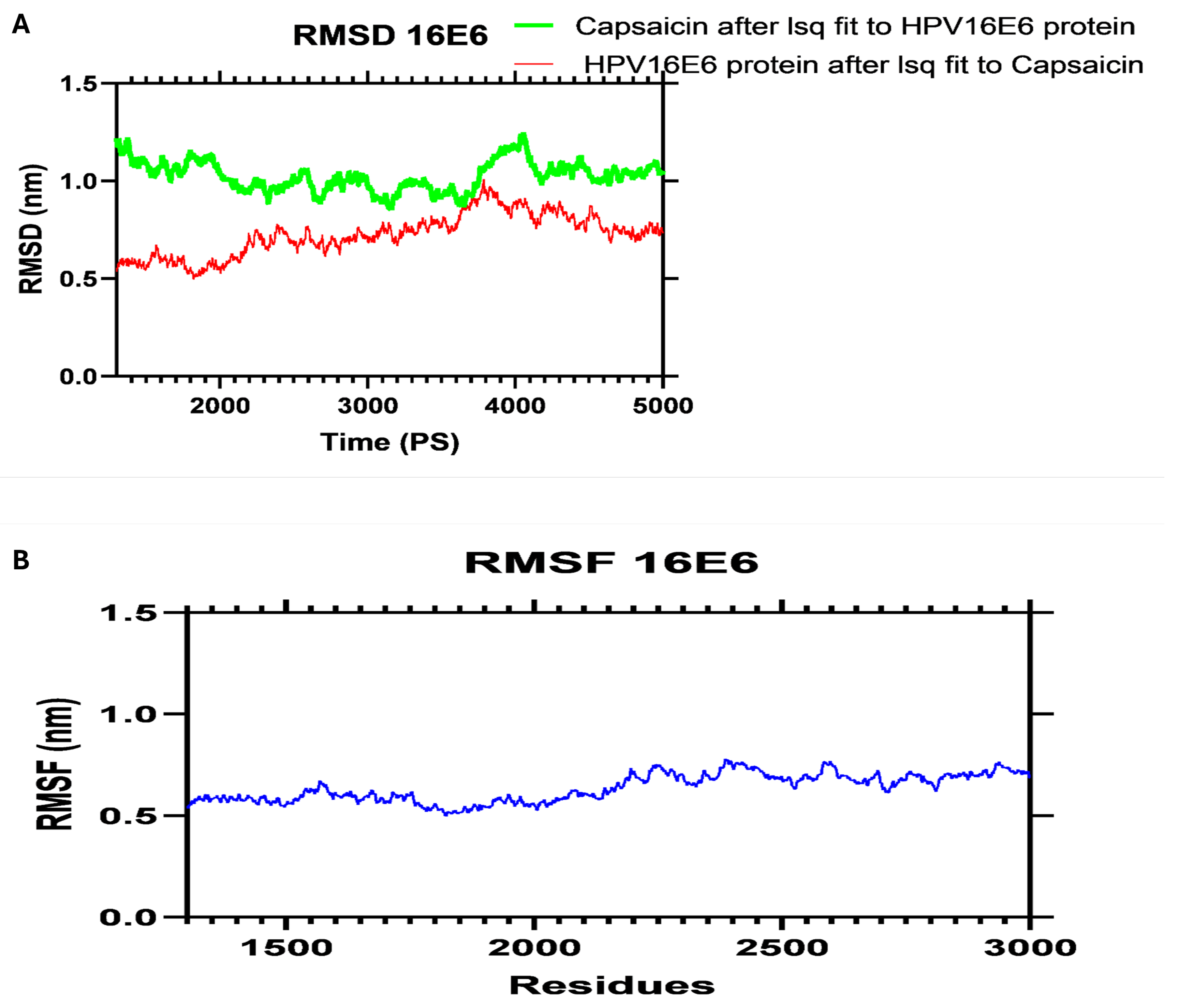

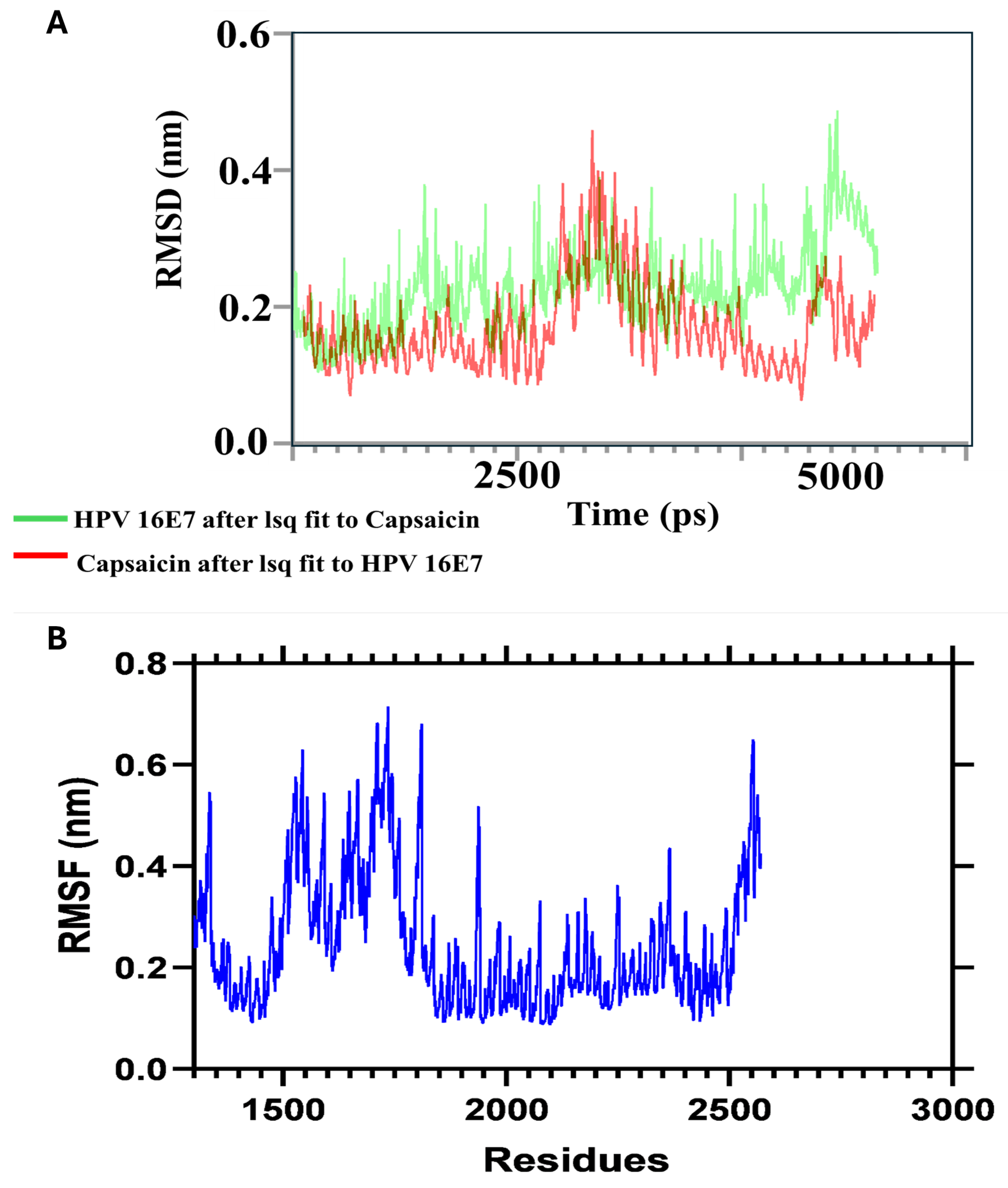

To further validate the stability of Capsaicin's binding to the HPV oncoproteins, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The results of these simulations demonstrated that Capsaicin maintained stable interactions with both HPV 16 E6 and E7 throughout the simulation period, indicating a good binding mode that is crucial for effective inhibition of the oncoproteins' function in a biological setting as represented in

Figure 5 and 6 respectively. Comparable studies have employed MD simulations to assess the stability of natural compound interactions with HPV oncoproteins. For instance, a study by Mohabatkar et al. (2020) investigated the molecular interactions of plant-derived inhibitors against HPV 16 E6 using MD simulations [

15]. The researchers found that the compounds Ginkgetin, Hypericin, and Apigetrin formed stable interactions with the E6 protein, with Ginkgetin demonstrating the lowest binding energy of -8.45 kcal/mol [

16]. This aligns with our findings regarding Capsaicin's stable binding to E6, highlighting the importance of MD simulations in validating the durability of inhibitor-oncoprotein interactions. Furthermore, a study by Basukala and Banks (2021) discussed the potential of natural compounds, such as curcumin and indole-3-carbinol, in inhibiting HPV activity by restoring p53 function [

18]. The sustained interaction between Capsaicin and the HPV oncoproteins throughout the simulation period suggests that it may effectively disrupt the oncoproteins' ability to inactivate p53, a critical tumor suppressor, thereby restoring normal cellular processes. In this work, in conjunction with GROMACS we also performed a simulation analysis utilizing the iMODS webserver to assess the system's stability. The iMODS server uses Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) to characterize macromolecules' collective functional movements [

29]. Each normal mode has a frequency that corresponds to the magnitude of relative motion as well as a deformation vector that specifies the direction of atomic displacement, which aids in determining molecular flexibility within the cellular environment.

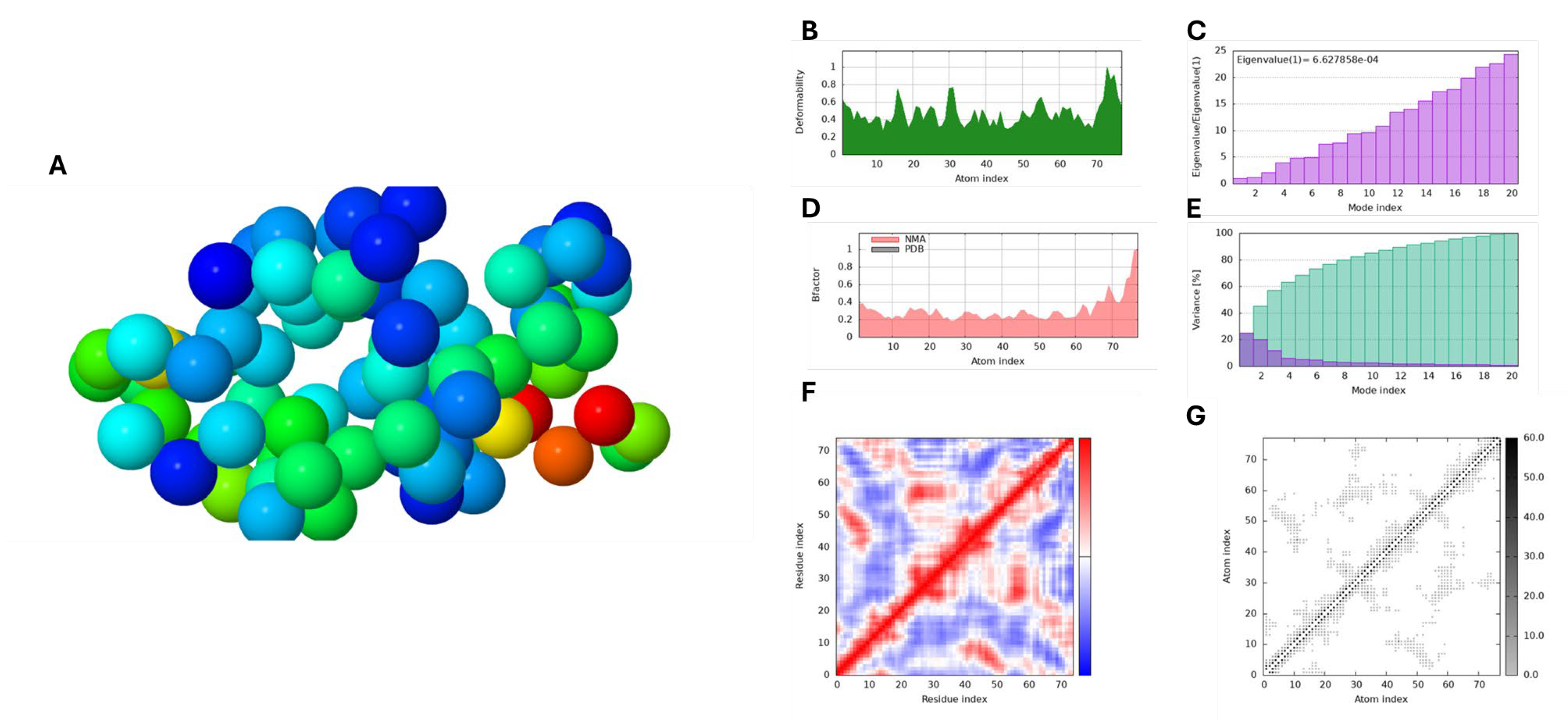

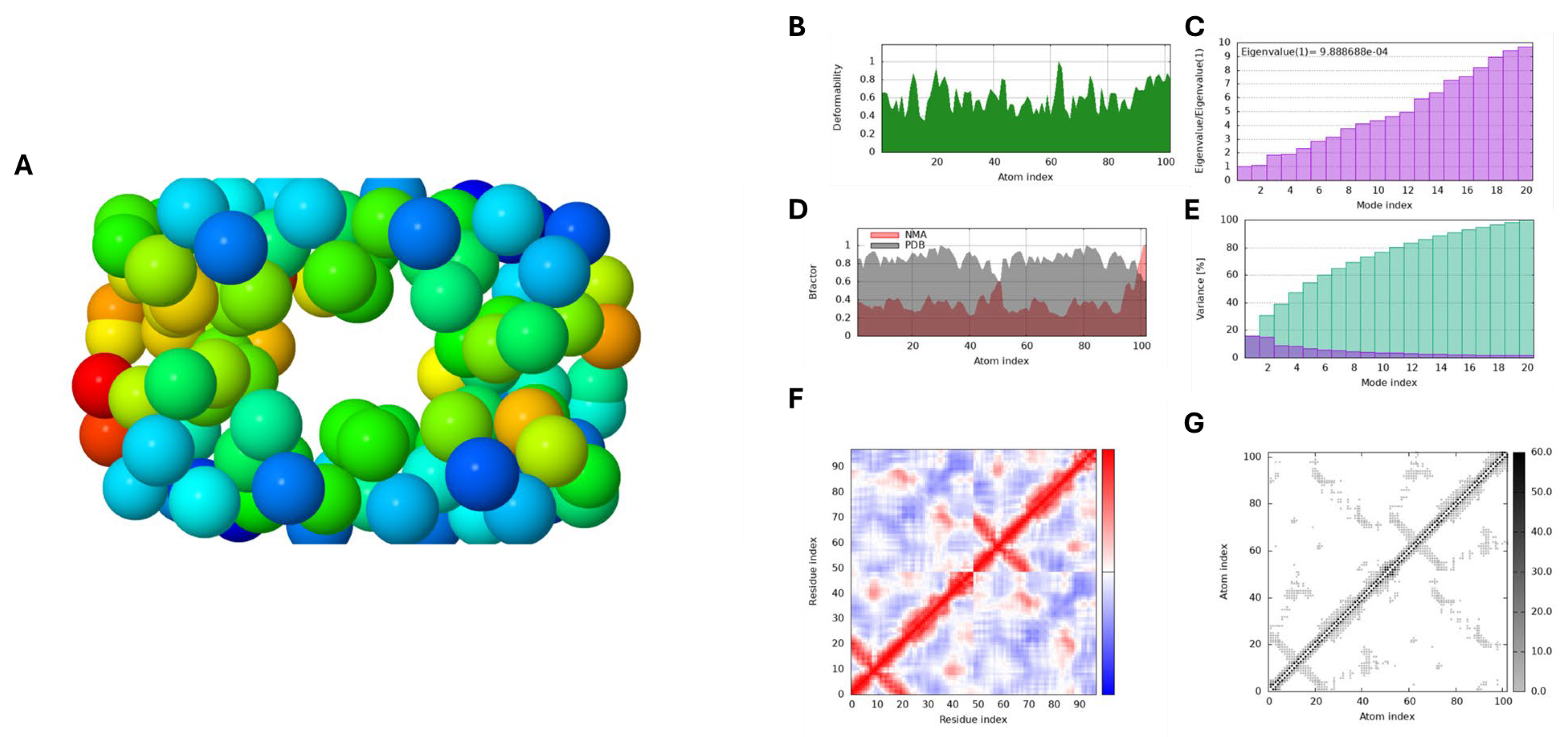

Figure 7A and

Figure 8A represents the findings of the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and NMA of the Capsaicin/HPV 16 E6 and E7 protein complex. To simulate following transitions, we iteratively distorted the input structure along the lowest modes, reducing the root mean square deviation (RMSD) by superimposing the structures locally and globally. Main-chain deformability measures atomic displacements summed across all modes at each atomic site, allowing us to identify deformable areas within the protein. As seen in

Figure 7B and

Figure 8B, peaks on the deformability graph represent flexible parts, such as hinges or linkers, whereas lower values correlate to more stiff regions of the main chain.

The B-factor derived from NMA assesses the relative amplitude of atomic displacements around the equilibrium conformation of the molecular complex. As shown in

Figure 7D and

Figure 8D, the B-factor graph reveals the correlation between the mobility of the docked complex and PDB scores, which represent the average RMSD. Additionally, each normal mode’s eigenvalue indicates the stiffness of the associated motion, directly relating to the energy required for structural deformation. A lower eigenvalue signifies easier deformation of the carbon alpha atoms. For the Capsaicin and HPV 16 E6 and E7 protein complex, the eigenvalues were 6.627858e-04 and 9.888688e-04, respectively, reflecting the stability of the complex as represented in

Figure 7C and

Figure 8C.

However, the Elastic Network Model (ENM) depicted in

Figure 7G and

Figure 8G illustrates the interconnectivity of different regions within the macromolecule and how these connections contribute to its overall structural integrity. It effectively visualizes the network of interactions that sustain the stability and rigidity of the structure, highlighting areas of varying stiffness. In this model, each dot represents a spring connecting a pair of atoms, with colours indicating their stiffness; darker shades of grey correspond to stiffer regions, while lighter dots signify more flexible areas. In our study, the analysis revealed that HPV 16 E7 exhibits a greater proportion of stiffer regions compared to HPV 16 E6, indicating enhanced structural rigidity. Despite this difference, both proteins demonstrated good structural integrity throughout the simulations. Furthermore, as seen in

Figure 7E and

Figure 8E the variance panel illustrates the distribution of variance across different modes, with purple bars indicating the variance for individual components and green bars representing cumulative variance. This visualization reveals the contribution of each mode to the overall motion of the macromolecule. Additionally, the covariance matrix panel depicts the relationships between the movements of paired residues. Correlated movements, shown in red, indicate residues that move together, while uncorrelated movements in white suggest independent motion. Anti-correlated movements, represented in blue, highlight residues that move in opposite directions. Understanding these motion patterns is essential for comprehending the dynamic interactions among different regions of the macromolecule.

Thus, our findings shed light on the dynamic behaviour and stability of the Capsaicin and HPV 16 E6 and E7 protein complexes. This sustained interaction between Capsaicin and the oncoproteins shows its potential as a durable and effective inhibitor, with implications for restoring normal cellular function and suppressing oncogenic processes driven by HPV

Toxicity Studies

The toxicity classification results as summarized in

Table 2, reveal that the compound has a moderate likelihood of hepatotoxicity, with a probability of 0.69, while showing low risks for nephrotoxicity (0.90) and cardiotoxicity (0.77). In terms of toxicity endpoints, it has a moderate risk of carcinogenicity (0.62) but a high potential for immunotoxicity (0.96). It is unlikely to cause mutagenicity (0.97), cytotoxicity (0.93), or clinical toxicity (0.56), and exhibits low nutritional toxicity (0.74). The compound is classified as Toxicity Class 4, indicating low overall toxicity, with a predicted LD50 of 1190 mg/kg, suggesting a high dose is needed for lethal effects in 50% of the test population. While the findings highlight potential concerns regarding hepatotoxicity and immunotoxicity, the overall toxicity profile appears acceptable, supporting its therapeutic application.

Conclusions

Based on the molecular docking, drug-likeness analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation, Capsaicin emerged as the most promising candidate for inhibiting both HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins. Its ability to form stable hydrogen bonds and maintain consistent binding interactions throughout the simulation period makes it a compelling candidate for further investigation.

We propose that Capsaicin be validated in wet lab experiments to confirm its efficacy in inhibiting HPV 16 oncoproteins in cellular and animal models. Additionally, its pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and potential for therapeutic application should be thoroughly investigated. The insights gained from this study provide a strong foundation for the development of Capsaicin-based therapeutics for the treatment of HPV-related cervical cancer.

References

- Arbyn, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Bruni, L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Saraiya, M.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis [published correction appears in Lancet Glob Health. 2022 Jan;10,e41]. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e191–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Castellsagué, X.; de Sanjosé, S.; Bruni, L.; Saraiya, M.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J. Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 2675–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haręża DA, Wilczyński JR, Paradowska E. Human papillomaviruses as infectious agents in gynecological cancers. Oncogenic properties of viral proteins. International journal of molecular sciences. 2022 Feb 5;23(3):1818.

- Jones, E.; Wells, S. Cervical Cancer and Human Papillomaviruses: Inactivation of Retinoblastoma and Other Tumor Suppressor Pathways. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghittoni, R.; Accardi, R.; Hasan, U.; Gheit, T.; Sylla, B.; Tommasino, M. The biological properties of E6 and E7 oncoproteins from human papillomaviruses. Virus Genes 2009, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Signaling pathways in HPV-associated cancers and therapeutic implications. Rev. Med. Virol. 2015, 25 (Suppl. 1), 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Kundu, R. Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7: The Cervical Cancer Hallmarks and Targets for Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelin, J.; Sabol, I.; Tomaić, V. Do or Die: HPV E5, E6 and E7 in Cell Death Evasion. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf L, Bala JA, Aliyu IA, Kabir IM, Abdulkadir S, Doro AB, Kumurya AS. Phytotherapy as an alternative for the treatment of human papilloma virus infections in Nigeria: a review. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology. 2020 May 26;21(3):175-84.

- Franconi, R.; Massa, S.; Paolini, F.; Vici, P.; Venuti, A. Plant-Derived Natural Compounds in Genetic Vaccination and Therapy for HPV-Associated Cancers. Cancers 2020, 12, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.; Yadav, J.; Chhakara, S.; Janjua, D.; Tripathi, T.; Chaudhary, A.; Chhokar, A.; Thakur, K.; Singh, T.; Bharti, A.C. Phytochemicals as Potential Chemopreventive and Chemotherapeutic Agents for Emerging Human Papillomavirus-Driven Head and Neck Cancer: Current Evidence and Future Prospects. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Ramachandran, S.; Gupta, N.; Kaushik, I.; Wright, S.; Srivastava, S.; Das, H.; Srivastava, S.; Prasad, S.; Srivastava, S.K. Role of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Sabanayagam, R.; Schwenk, G.; Feng, E.; Ji, H.-F.; Muthusami, S. Pharmacophore based virtual screening for identification of effective inhibitors to combat HPV 16 E6 driven cervical cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 957, 175961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci-López, J.; Vidal-Limon, A.; Zunñiga, M.; Jimènez, V.A.; Alderete, J.B.; Brizuela, C.A.; Aguila, S. Molecular modeling simulation studies reveal new potential inhibitors against HPV E6 protein. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0213028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Jena, L.; Galande, S.; Daf, S.; Mohod, K.; Varma, A.K. Elucidating Molecular Interactions of Natural Inhibitors with HPV-16 E6 Oncoprotein through Docking Analysis. Genom. Informatics 2014, 12, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baleja, J.D.; Cherry, J.J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, H.; Nicklaus, M.C.; Voigt, J.H.; Chen, J.J.; Androphy, E.J. Identification of inhibitors to papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein based on three-dimensional structures of interacting proteins. Antivir. Res. 2006, 72, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabati, F.; Moradi, M.; Mohabatkar, H. In silico analyzing the molecular interactions of plant-derived inhibitors against E6AP, p53, and c-Myc binding sites of HPV type 16 E6 oncoprotein. 2020, 9, 71–82. [CrossRef]

- Aarthy, M.; Panwar, U.; Singh, S.K. Structural dynamic studies on identification of EGCG analogues for the inhibition of Human Papillomavirus E7. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, S.; Razzaghi-Asl, N.; Mirzayi, S.; Mahnam, K.; Adhami, V. In silico screening and molecular dynamics simulations toward new human papillomavirus 16 type inhibitors. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 17, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci-López, J.; Vidal-Limon, A.; Zunñiga, M.; Jimènez, V.A.; Alderete, J.B.; Brizuela, C.A.; Aguila, S. Molecular modeling simulation studies reveal new potential inhibitors against HPV E6 protein. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0213028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoni, C.; Olotu, F.A.; Ramharack, P.; Soliman, M.E. Druggability and drug-likeness concepts in drug design: are biomodelling and predictive tools having their say? J. Mol. Model. 2020, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G. Prediction of drug-like properties. InMadame curie bioscience database [Internet] 2013. Landes Bioscience.

- Tian, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Xu, L.; Hou, T. The application of in silico drug-likeness predictions in pharmaceutical research. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 86, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerton, G.R.; Paolini, G.V.; Besnard, J.; Muresan, S.; Hopkins, A.L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basukala, O.; Banks, L. The Not-So-Good, the Bad and the Ugly: HPV E5, E6 and E7 Oncoproteins in the Orchestration of Carcinogenesis. Viruses 2021, 13, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ukić, A. Interactions of HPV E6 Oncoproteins with Binding Partners: Implications on E6 Stability and Cellular Functions (Doctoral dissertation, University of Rijeka. Department of Biotechnology).

- Tomaić, V. Functional Roles of E6 and E7 Oncoproteins in HPV-Induced Malignancies at Diverse Anatomical Sites. Cancers 2016, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Blanco JR, Aliaga JI, Quintana-Ortí ES, Chacón P. iMODS: internal coordinates normal mode analysis server. Nucleic acids research. 2014 Jul 1;42(W1):W271-6.

Figure 1.

ADMET study results for the selected molecules. This figure presents the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles of all the docked compounds. The results illustrate the pharmacokinetic properties and potential toxicological effects, aiding in the assessment of the drug-likeness and safety of these molecules.

Figure 1.

ADMET study results for the selected molecules. This figure presents the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles of all the docked compounds. The results illustrate the pharmacokinetic properties and potential toxicological effects, aiding in the assessment of the drug-likeness and safety of these molecules.

Figure 2.

Rule violations for various molecules. This figure displays the number and types of pharmacokinetic rule violations, such as Lipinski's rule of five, for the studied molecules. The analysis highlights which compounds deviate from standard drug-likeness criteria.

Figure 2.

Rule violations for various molecules. This figure displays the number and types of pharmacokinetic rule violations, such as Lipinski's rule of five, for the studied molecules. The analysis highlights which compounds deviate from standard drug-likeness criteria.

Figure 3.

Molecular docking interactions of Capsaicin with HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins. The figure illustrates the binding of Capsaicin within the active sites of both A. HPV 16 E6 and B. HPV 16 E7 proteins, highlighting key interactions and the stabilization of the ligand within the protein structures.

Figure 3.

Molecular docking interactions of Capsaicin with HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins. The figure illustrates the binding of Capsaicin within the active sites of both A. HPV 16 E6 and B. HPV 16 E7 proteins, highlighting key interactions and the stabilization of the ligand within the protein structures.

Figure 4.

Molecular docking interactions of Catechin, Isoflavone, and Piperlongumine with HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins. A. Interaction of Catechin with HPV 16 E6 protein. B. Interaction of Catechin with HPV 16 E7 protein. C. Interaction of Isoflavone with HPV 16 E6 protein. D. Interaction of Isoflavone with HPV 16 E7 protein. E. Interaction of Piperlongumine with HPV 16 E6 protein. F. Interaction of Piperlongumine with HPV 16 E7 protein.

Figure 4.

Molecular docking interactions of Catechin, Isoflavone, and Piperlongumine with HPV 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins. A. Interaction of Catechin with HPV 16 E6 protein. B. Interaction of Catechin with HPV 16 E7 protein. C. Interaction of Isoflavone with HPV 16 E6 protein. D. Interaction of Isoflavone with HPV 16 E7 protein. E. Interaction of Piperlongumine with HPV 16 E6 protein. F. Interaction of Piperlongumine with HPV 16 E7 protein.

Figure 5.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of HPV 16 E6 Protein in Complex with Capsaicin. (A) Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) Profile, Indicating the Stability of the Protein-Ligand Complex Over 5ns. (B) Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) Profile, Highlighting the Flexibility of Residues in the HPV 16 E6 Protein Upon Binding with Capsaicin.

Figure 5.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of HPV 16 E6 Protein in Complex with Capsaicin. (A) Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) Profile, Indicating the Stability of the Protein-Ligand Complex Over 5ns. (B) Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) Profile, Highlighting the Flexibility of Residues in the HPV 16 E6 Protein Upon Binding with Capsaicin.

Figure 6.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of HPV 16 E7 Protein in Complex with Capsaicin. (A) Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) Profile Demonstrating the Stability of the Protein-Ligand Complex Over a 5 ns Simulation. (B) Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) Profile, Illustrating the Flexibility of Residues in the HPV 16 E7 Protein Upon Binding with Capsaicin.

Figure 6.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of HPV 16 E7 Protein in Complex with Capsaicin. (A) Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) Profile Demonstrating the Stability of the Protein-Ligand Complex Over a 5 ns Simulation. (B) Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) Profile, Illustrating the Flexibility of Residues in the HPV 16 E7 Protein Upon Binding with Capsaicin.

Figure 7.

The figure shows Molecular Dynamics Simulation results of Capsaicin against HPV 16 E6 analysed via the iMODS server. Panel A illustrates NMA stability, Panel B displays structural deformability, and Panel C shows eigenvalues indicating motion. Panel D presents B-factors reflecting atomic fluctuations. Panel E depicts variance with individual (purple) and cumulative (green) components. Panel F shows the covariance matrix, indicating correlated (red), uncorrelated (white), and anti-correlated (blue) motions of paired residues. Panel G visualizes the Elastic Network Model, highlighting structural connectivity.

Figure 7.

The figure shows Molecular Dynamics Simulation results of Capsaicin against HPV 16 E6 analysed via the iMODS server. Panel A illustrates NMA stability, Panel B displays structural deformability, and Panel C shows eigenvalues indicating motion. Panel D presents B-factors reflecting atomic fluctuations. Panel E depicts variance with individual (purple) and cumulative (green) components. Panel F shows the covariance matrix, indicating correlated (red), uncorrelated (white), and anti-correlated (blue) motions of paired residues. Panel G visualizes the Elastic Network Model, highlighting structural connectivity.

Figure 8.

The Molecular Dynamics Simulation results of Capsaicin against HPV 16 E7 analysed via the iMODS server. Panel A illustrates NMA stability, Panel B displays structural deformability, and Panel C shows eigenvalues indicating motion. Panel D presents B-factors reflecting atomic fluctuations. Panel E depicts variance with individual (purple) and cumulative (green) components. Panel F shows the covariance matrix, indicating correlated (red), uncorrelated (white), and anti-correlated (blue) motions of paired residues. Panel G visualizes the Elastic Network Model, highlighting structural connectivity.

Figure 8.

The Molecular Dynamics Simulation results of Capsaicin against HPV 16 E7 analysed via the iMODS server. Panel A illustrates NMA stability, Panel B displays structural deformability, and Panel C shows eigenvalues indicating motion. Panel D presents B-factors reflecting atomic fluctuations. Panel E depicts variance with individual (purple) and cumulative (green) components. Panel F shows the covariance matrix, indicating correlated (red), uncorrelated (white), and anti-correlated (blue) motions of paired residues. Panel G visualizes the Elastic Network Model, highlighting structural connectivity.

Table 1.

Molecular Docking Results and Hydrogen Bond Interactions of Selected Compounds with HPV 16 E6 and E7 Oncoproteins.

Table 1.

Molecular Docking Results and Hydrogen Bond Interactions of Selected Compounds with HPV 16 E6 and E7 Oncoproteins.

| Compounds |

16E6 |

16E7 |

| Vina results (kcal/mol) |

Hydrogen binding interaction |

Vina results (kcal/mol) |

Hydrogen binding interaction |

| Capsaicin |

-7.3 |

ASP-98 |

-5.6 |

PHE-57 |

| Catechins |

-6.5 |

LYS-115 |

-7.7 |

- |

| Lycopene |

-9.3 |

- |

-9.5 |

- |

| CucurbitacinB |

-11.5 |

- |

-12.7 |

- |

| Benzylisothiocyanate (BITC) |

-4.2 |

- |

-4.1 |

- |

| PEITC |

-3.9 |

- |

-4.1 |

- |

| Isoflavone |

-6.3 |

ARG-117 |

-7.4 |

- |

| Piperlongumine |

-5.5 |

- |

-5.9 |

- |

Table 2.

summary of the predictions for various toxicity endpoints, along with the predicted LD50 and toxicity class.

Table 2.

summary of the predictions for various toxicity endpoints, along with the predicted LD50 and toxicity class.

| Classification |

Target |

Prediction |

Probability |

| Organ toxicity |

Hepatotoxicity |

Active |

0.69 |

| Organ toxicity |

Nephrotoxicity |

Inactive |

0.90 |

| Organ toxicity |

Cardiotoxicity |

Inactive |

0.77 |

| Toxicity end points |

Carcinogenicity |

Inactive |

0.62 |

| Toxicity end points |

Immunotoxicity |

Active |

0.96 |

| Toxicity end points |

Mutagenicity |

Inactive |

0.97 |

| Toxicity end points |

Cytotoxicity |

Inactive |

0.93 |

| Toxicity end points |

Clinical toxicity |

Inactive |

0.56 |

| Toxicity end points |

Nutritional toxicity |

Inactive |

0.74 |

| Predicted LD50 |

|

1190 mg/kg |

|

| Predicted Toxicity Class |

|

Class 4 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).