Submitted:

13 August 2024

Posted:

14 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Essential Oil Mixture Preparation

| Type of oil | Scientific Name | Mode of production |

|---|---|---|

| Cocoa Oil | Theobroma cacao | Cold Pressed Oil |

| Celery Oil | Apium graveolens | Cold Pressed Oil |

| Apricot Seed Oil | Prunus armeniaca | Cold Pressed Oil |

| Myrrha Oil | Commiphora myrrha | Etheric Oil |

| Type of oil | Scientific Name | Main Molecule/s / Ligands |

|---|---|---|

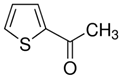

| Cacao Oil | Theobroma cacao | 2-Acetylpyrrole |

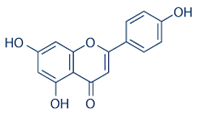

| Celery Oil | Apium graveolens | Apigenin |

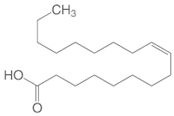

| Apricot Seed Oil | Prunus armeniaca | Oleic Acid |

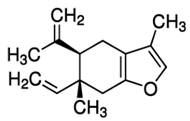

| Myrrha Oil | Commiphora myrrha | Curzerene |

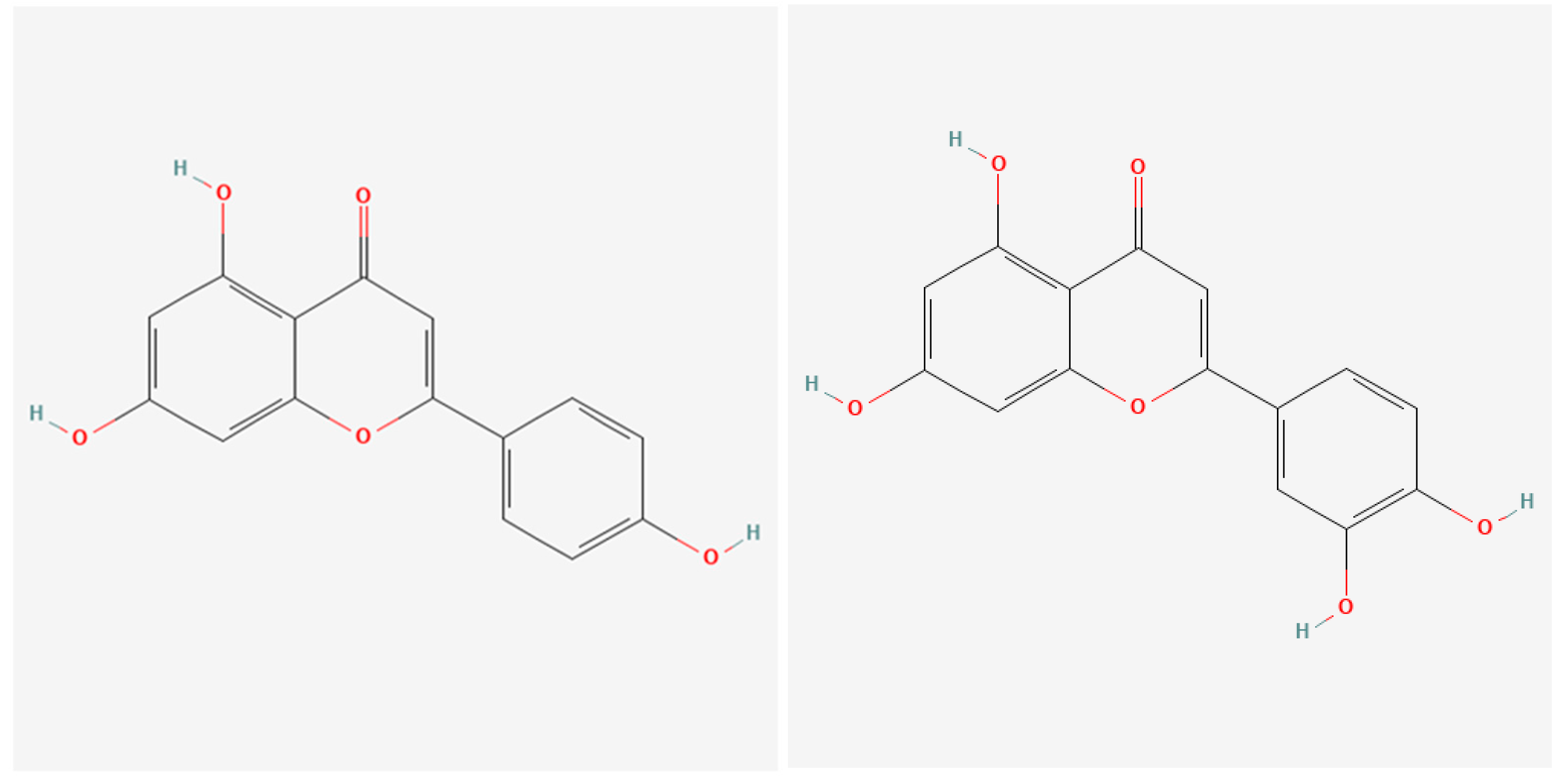

| Main Molecule/s | Structure Formula |

|---|---|

| 2-Acetylpyrrole |  |

| Apigenin |  |

| Oleic Acid |  |

| Curzerene |  |

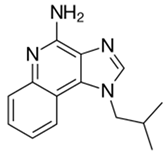

| Imiquimod |  |

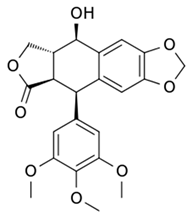

| Podofilox |  |

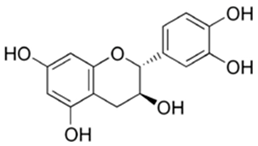

| Sinecatechins |  |

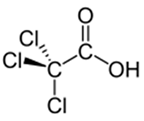

| Trichloroacetic Acid |  |

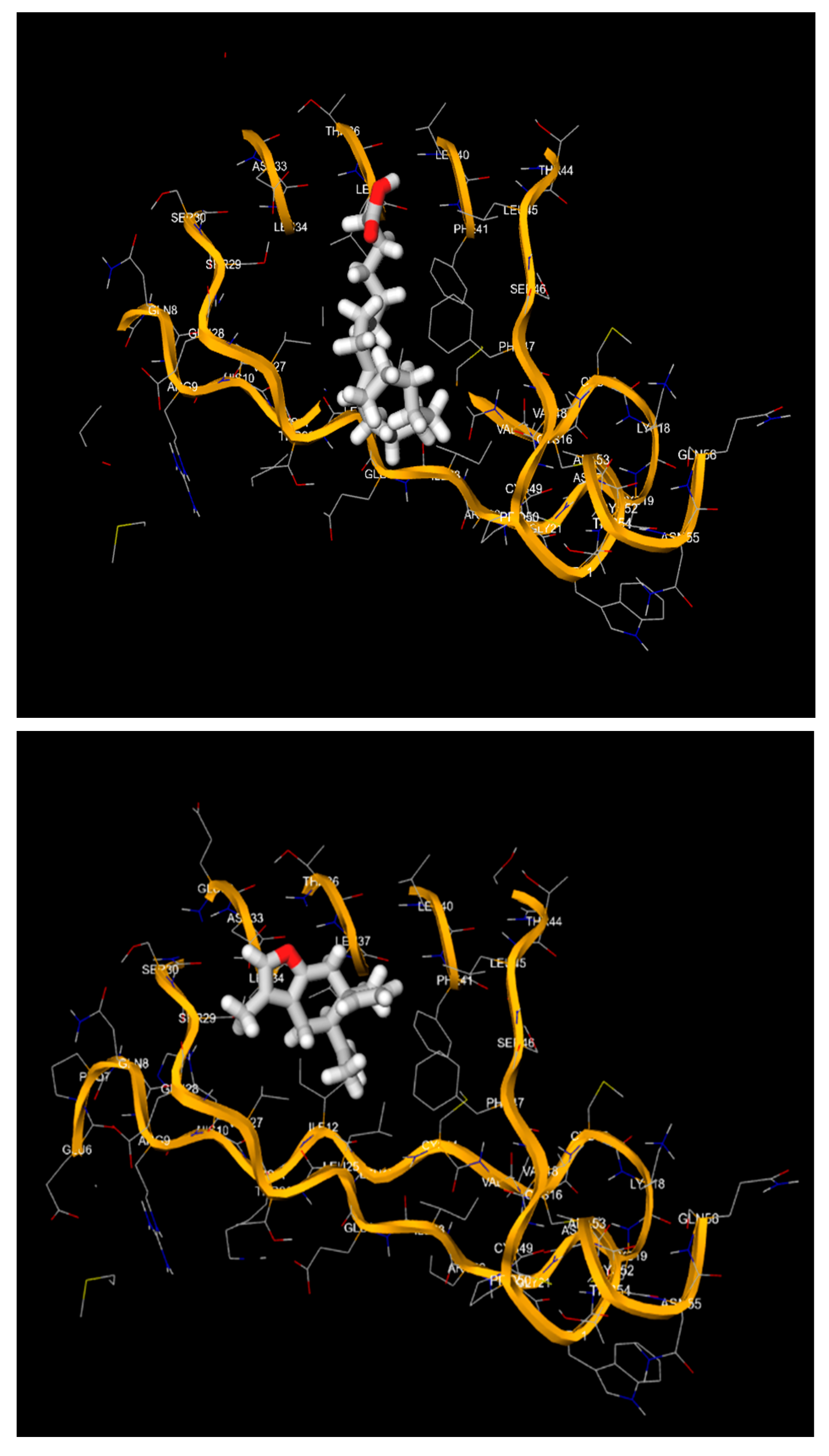

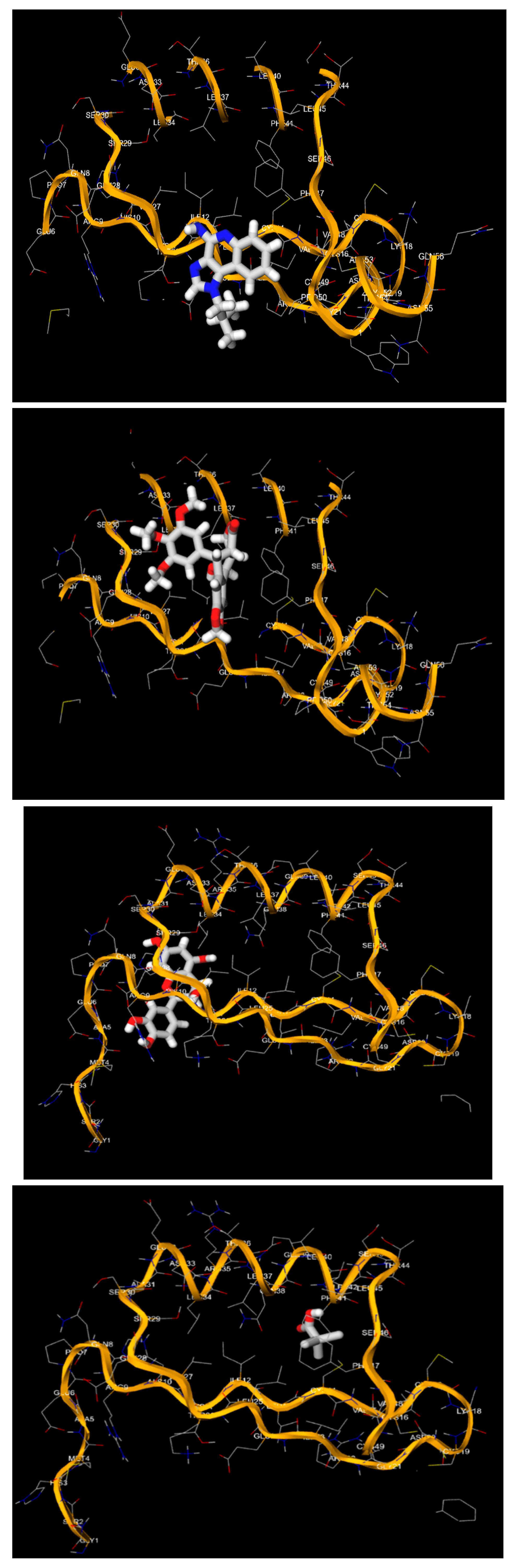

| Molecule / Protein / Target | 3D Structure |

|---|---|

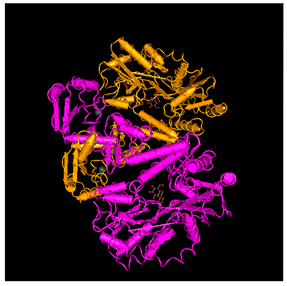

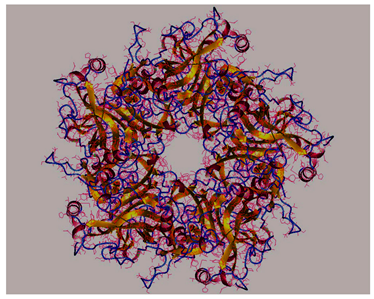

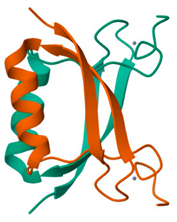

| E6 Oncoprotein of HPV-16 strain |  |

| Major Capsid Protein L1 of HPV-16 strain |  |

| E7 Oncoprotein of HPV-16 strain |  |

Molecular Docking

- °

- The 3D structures of the HPV-16 E6, E7 oncoproteins, and L1 major capsid protein were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Table 4).

- °

- The chemical structures of the ligands (essential oil components) were obtained from PubChem and optimized for docking using energy minimization techniques.

- °

- Molecular docking was conducted using 1-Click Docking (https://mcule.com/apps/1-click-docking/), a widely used docking software.

- °

- The docking grid was defined to encompass the active sites of the target proteins, ensuring that all potential binding interactions could be evaluated.

- °

- The binding affinity of each ligand to the target protein was quantified using the Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔG).

- °

- The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) is a thermodynamic parameter that indicates the spontaneity of the binding process. A more negative ΔG value suggests a stronger and more favorable binding interaction.

- °

- ΔG was calculated using the equation: ΔG = ΔH – TΔS where ΔH is the enthalpy change, T is the temperature, and ΔS is the entropy change.

- °

- The binding affinities (in kcal/mol) and the specific amino acid residues involved in the interactions were recorded.

- °

- The docking scores were analyzed to identify the most potent ligands based on their binding energies and interaction patterns.

- Software: 1-Click-Docking

- Target Proteins: HPV-16 E6 oncoprotein, E7 oncoprotein, and L1 major capsid protein

- Ligands: Components of the essential oil mixture

3. Results

| Ligand | Target (HPV-16) | Bond Strenght (Kcal/mol) | Aminoacidic Residues Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

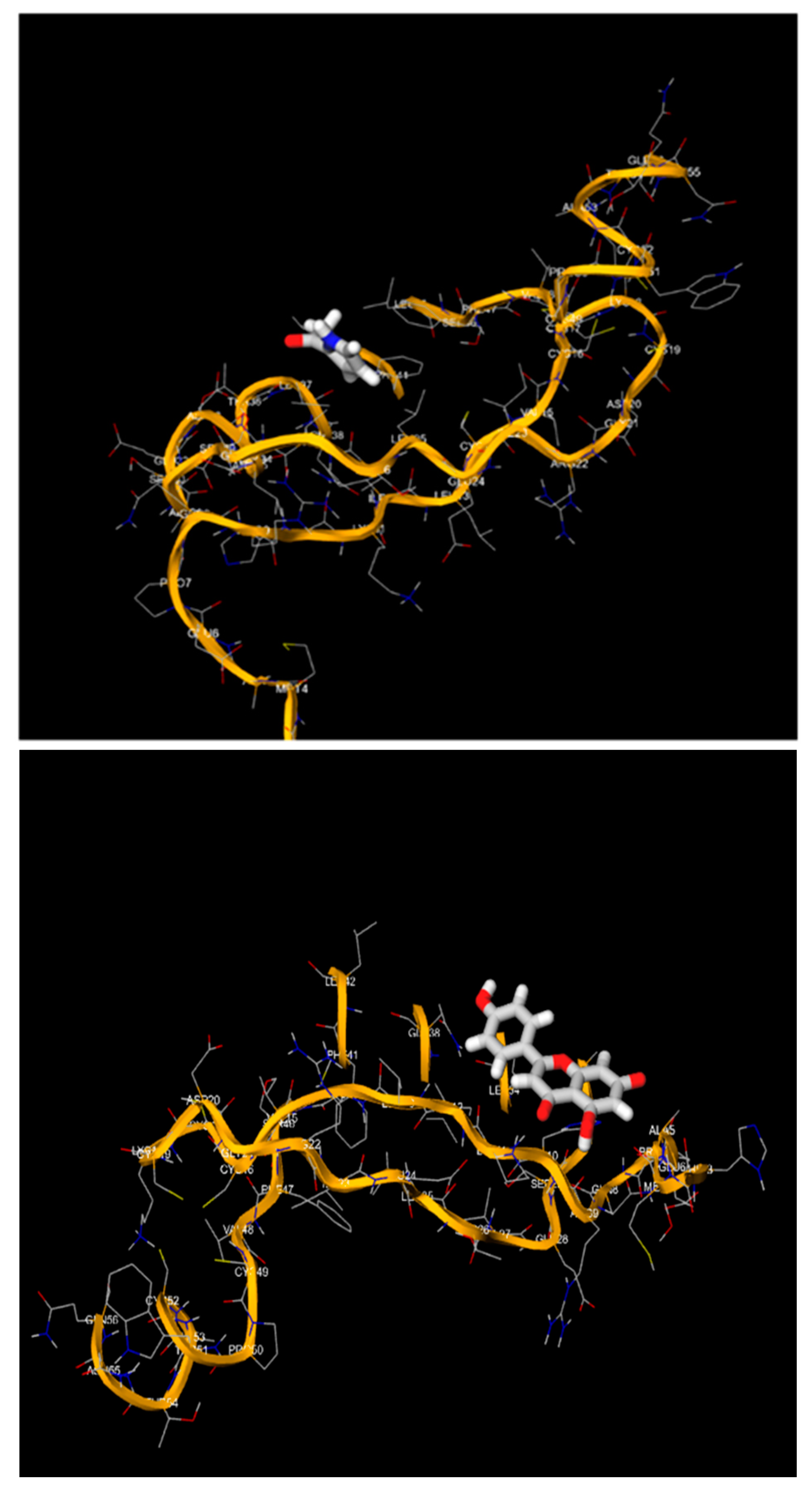

| 2-acetylpyrrole | E6 Oncoprotein | -4.4 | le 23, Ile 24, Ala 28, Ile 47, Gly 48, Gly 49 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -3.3 | Asp 33, Val 27, Leu 25, Phe 47 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -2.6 | His 56, Asp 125, Gly 130, Gly 134 | |

| Apigenin | E6 Oncoprotein | -7.8 | Gly 27, Ala 28, Gly 49, Pro 81, Val 82 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -5.6 | Pro 7, Ala 5, Ile 12, Leu 37, His 10, Asp 33 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -3.7 | Asp 125, Gly 127, Gly 130, Phe 257 | |

| Oleic Acid | E6 Oncoprotein | -4.1 | Gly 48, Gly 51, Ile 53, Phe 53, Ile 54, Pro 81 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -3.7 | Phe 47, Ser 46, Phe 41, Leu 45, Glu 24 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -1.9 | Asp 120, Gly 130, Gly 231, Phe 257 | |

| Curzerene | E6 Oncoprotein | -6.2 | Leu 22, Asp 26, Gly 27, Ala 28 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -5.0 | Asn 33, Phe 41, Ile 12, Glu 28, Trp 36 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -3.0 | Asp 125, Gly 127, Asp 224, Val 226 | |

| Imiquimod | E6 Oncoprotein | -4.1 | Thr 86, Thr 87, Arg 124, Tyr 124 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -4.9 | Pro 50, Leu 25, Val 27, Glu 28, Ser 29 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -3.6 | Val 126, Ser 129, His 256, Phe 257 | |

| Podofilox | E6 Oncoprotein | -4.5 | Thr 86, His 121, Tyr 127, Pro 221 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -5.5 | Ser 30, Asp 33, Leu 40, Glu 39, Ser 29 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -3.8 | Val 126, Gly 127, Asn 128, Phe 257 | |

| Sinecatechins | E6 Oncoprotein | -4.5 | Thr 84, Thr 87, His 126, Val 183 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -5.3 | Pro 7, Gln 8, His 10, Ile 12, Ala 5, Met 4 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -3.8 | Gly 130, Asn 143, His 256, Phe 257 | |

| Trichlooacetic Acid | E6 Oncoprotein | -2.6 | Thr 87, Tyr 124, Arg 124, Phe 125 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -2.9 | Ser 46, Phe 41, Leu 45, Cys 14, Val 45 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -2.4 | Tyr 123, His 256, Phe 257, Phe 258 |

- °

- Apigenin has the highest binding affinity for E6 Oncoprotein at -7.8 kcal/mol.

- °

- Curzerene follows with -6.2 kcal/mol for E6 Oncoprotein.

- °

- Both Apigenin and Podofilox exhibit strong binding to E7 Oncoprotein (-5.6 and -5.5 kcal/mol respectively).

- °

- Trichloroacetic Acid exhibits the weakest binding across all targets, with binding energies around -2.6 to -2.9 kcal/mol.

- °

- E6 Oncoprotein: Commonly involves residues such as Gly 27, Ala 28, and Gly 49 across multiple ligands.

- °

- E7 Oncoprotein: Residues like Val 27, Leu 25, and His 10 are frequently involved.

- °

- L1 Major Capsid Protein: Gly 130 and Phe 257 appear consistently across different ligand interactions.

- °

- The residues Gly 27 and Gly 49 in E6 Oncoprotein are crucial for multiple ligand bindings, indicating a potential hotspot for targeting.

- °

- For E7 Oncoprotein, His 10 and Val 27 are frequently interacting residues, suggesting their importance in ligand binding.

- °

- Null Hypothesis: There is no significant difference in the binding energies across different targets.

- °

- Alternative Hypothesis: There is a significant difference in the binding energies across different targets.

- °

- Null Hypothesis: The involvement of amino acid residues is independent of the ligand type.

- °

- Alternative Hypothesis: There is a dependence between ligand type and specific amino acid residues involved in binding.

- °

- The ANOVA test results are as follows:

- °

- F-statistic: 6.073

- °

- ρ-value: 0.0073

- °

- Since the p-value is less than the typical significance level of 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis. This indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in the binding energies across the different targets (E6 Oncoprotein, E7 Oncoprotein, and L1 Major Capsid Protein)

- °

- Apigenin: -7.8 Kcal/mol (strongest binding observed)

- °

- Comparison: Other ligands show weaker binding (e.g., Curzerene: -6.2 Kcal/mol, Podofilox: -4.5 Kcal/mol)

- °

- Apigenin: -5.6 Kcal/mol (second strongest binding after Podofilox)

- °

- Comparison: Other ligands show weaker binding (e.g., Curzerene: -5.0 Kcal/mol, Imiquimod: -4.9 Kcal/mol)

- °

- Apigenin: -3.7 Kcal/mol

- °

- Comparison: Other ligands show similar or weaker binding (e.g., Podofilox: -3.8 Kcal/mol, Sinecatechins: -3.8 Kcal/mol)

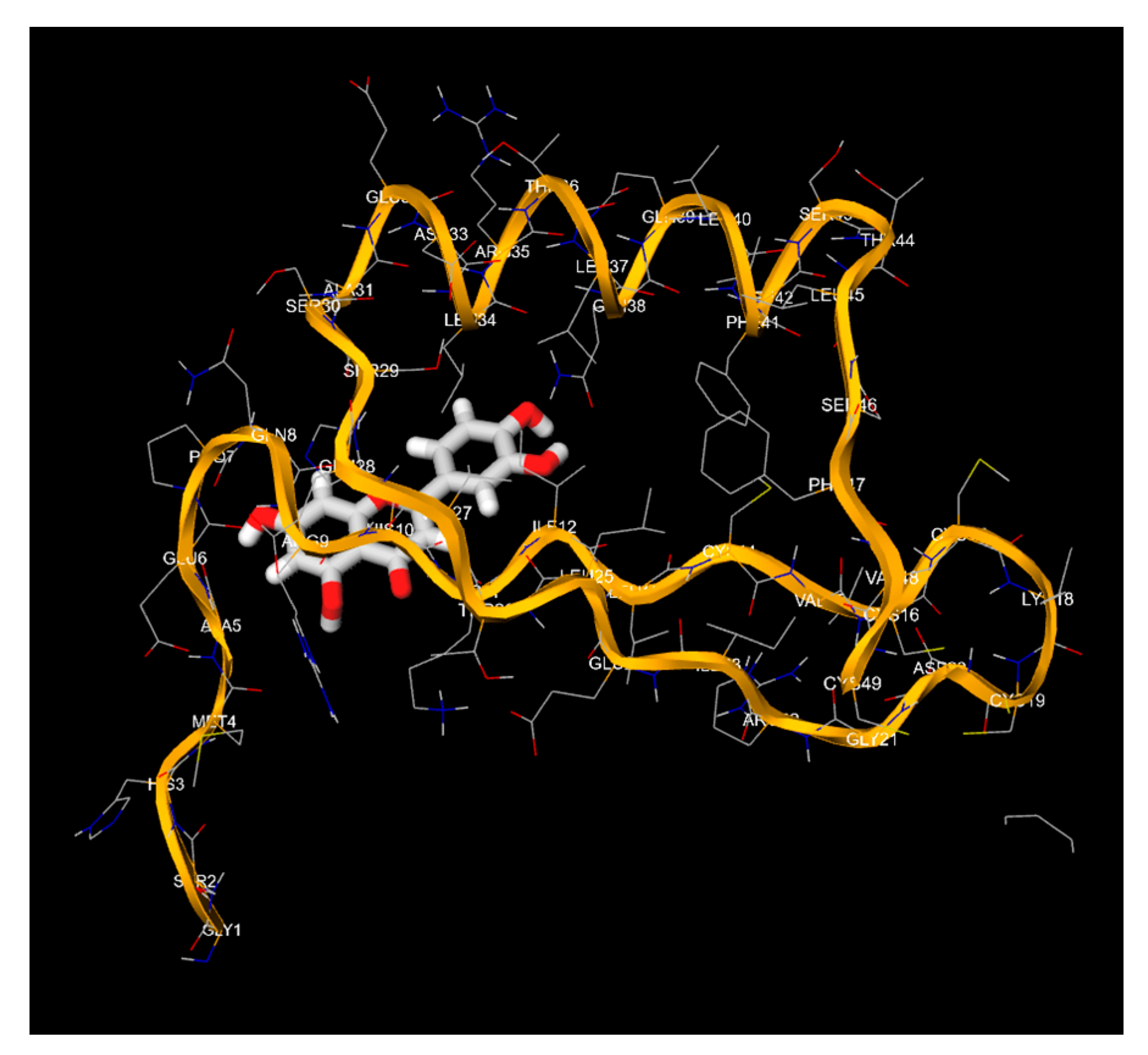

| Ligand | Target (HPV-16) | Bond Strenght (Kcal/mol) | Aminoacidic Residues Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luteolin | E6 Oncoprotein | -8.1 | Gln 49, Ser 44, Lys 21, Glu 121, His 144 |

| E7 Oncoprotein | -5.6 | Arg 29, Ile 12, Glu 25, Lys 27, His 10, Thr 36 | |

| L1 Major Capsid Protein | -7.9 | Pro 8, His 4, Asp 112, Asn 45 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bzhalava D, Guan P, Franceschi S, Dillner J, Clifford G (October 2013). "A systematic review of the prevalence of mucosal and cutaneous human papillomavirus types". Virology. 445 (1–2): 224–31. [CrossRef]

- Meyers J, Ryndock E, Conway MJ, Meyers C, Robison R (June 2014). "Susceptibility of high-risk human papillomavirus type 16 to clinical disinfectants". J Antimicrob Chemother. 69 (6): 1546–50. [CrossRef]

- Nowińska K, Ciesielska U, Podhorska-Okołów M, Dzięgiel P (2017). "The role of human papillomavirus in oncogenic transformation and its contribution to the etiology of precancerous lesions and cancer of the larynx: A review". Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 26 (3): 539–547. [CrossRef]

- Antonsson A, Forslund O, Ekberg H, Sterner G, Hansson BG (December 2000). "The ubiquity and impressive genomic diversity of human skin papillomaviruses suggest a commensalic nature of these viruses". Journal of Virology. 74 (24): 11636–41. [CrossRef]

- Sinal SH, Woods CR (October 2005). "Human papillomavirus infections of the genital and respiratory tracts in young children". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 16 (4): 306–16. [CrossRef]

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, Markowitz LE, Thomas CC, Thompson TD, et al. (July 2016). "Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers – United States, 2008–2012". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (26): 661–6. [CrossRef]

- Parfenov M, Pedamallu CS, Gehlenborg N, Freeman SS, Danilova L, Bristow CA, et al. (October 2014). "Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (43): 15544–9. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11115544P. [CrossRef]

- Hafner, Antonina; Bulyk, Martha L.; Jambhekar, Ashwini; Lahav, Galit (April 2019). "The multiple mechanisms that regulate p53 activity and cell fate". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 20 (4): 199–210. [CrossRef]

- Ault KA (2006). "Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections in the female genital tract". Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006 Suppl: 40470. [CrossRef]

- Doorbar, John; Quint, Wim; Banks, Lawrence; Bravo, Ignacio G.; Stoler, Mark; Broker, Tom R.; Stanley, Margaret A. (November 2012). "The Biology and Life-Cycle of Human Papillomaviruses". Vaccine. 30: F55–F70. [CrossRef]

- Abudula, Abulizi; Rouzi, Nuermanguli; Xu, Lixiu; Yang, Yun; Hasimu, Axiangu (2019). "Tissue-based metabolomics reveals potential biomarkers for cervical carcinoma and HPV infection". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 20 (1): 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Drake, Virginia; Fakhry, Carole; Windon, Melina J.; Stewart, C. Matthew; Akst, Lee; Hillel, Alexander; Chien, Wade; Ha, Patrick; Miles, Brett; Gourin, Christine G.; Mandal, Rajarsi; Mydlarz, Wojciech K.; Rooper, Lisa; Troy, Tanya; Yavvari, Siddhartha (11 January 2021). "Timing, number, and type of sexual partners associated with risk of oropharyngeal cancer". Cancer. 127 (7): 1029–1038. [CrossRef]

- Heymann MD (2015). Control of Communicable Diseases Manual (20th ed.). Washington D.C.: Apha Press. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-0-87553-018-5.

- Schmitt M, Depuydt C, Benoy I, Bogers J, Antoine J, Arbyn M, Pawlita M (May 2013). "Prevalence and viral load of 51 genital human papillomavirus types and three subtypes". International Journal of Cancer. 132 (10): 2395–403. [CrossRef]

- Tay SK, Ho TH, Lim-Tan SK (August 1990). "Is genital human papillomavirus infection always sexually transmitted?" (Free full text). The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 30 (3): 240–2. [CrossRef]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W (January–February 2004). "Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 36 (1): 6–10. [CrossRef]

- Desai M, Woodhall SC, Nardone A, Burns F, Mercey D, Gilson R (August 2015). "Active recall to increase HIV and STI testing: a systematic review". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 91 (5): 314–23. [CrossRef]

- Deleré Y, Wichmann O, Klug SJ, van der Sande M, Terhardt M, Zepp F, Harder T (September 2014). "The efficacy and duration of vaccine protection against human papillomavirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 111 (35–36): 584–91. [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Zavaleta L, Ambrosio JP, de Lourdes Mora-Garcia M, Cruz-Talonia F, Hernandez-Montes J, Weiss-Steider B, et al. (September 2004). "Detection of antibodies against a human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 peptide that differentiate high-risk from low-risk HPV-associated low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions". The Journal of General Virology. 85 (Pt 9): 2643–50. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez BY, McDuffie K, Goodman MT, Wilkens LR, Thompson P, Zhu X, et al. (February 2006). "Comparison of physician- and self-collected genital specimens for detection of human papillomavirus in men". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 44 (2): 513–7. [CrossRef]

- Pan C, Issaeva N, Yarbrough WG (2018). "HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer: current knowledge of molecular biology and mechanisms of carcinogenesis". Cancers of the Head & Neck. 3: 12. [CrossRef]

- Schiffman M, Castle PE (August 2003). "Human papillomavirus: epidemiology and public health" [1 January 2017]. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 127 (8): 930–4. [CrossRef]

- Zanier K, Charbonnier S, Sidi AO, McEwen AG, Ferrario MG, Poussin-Courmontagne P, et al. (February 2013). "Structural basis for hijacking of cellular LxxLL motifs by papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins". Science. 339 (6120): 694–8. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..694Z. [CrossRef]

- Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini, Slavisa Stanisic, Leonida Vitkovic. An Integrative Approach, by Using a Bi-Digital O-Ring Test (BDORT), Advanced Bioinformatics, and Clinical Testing for the Development of New Effective Treatment of Infections Caused by Human Papillomaviruses (HPV). March 2023, Acupuncture & Electro-Therapeutics Research 48(2). [CrossRef]

- Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini, Slavisa Stanisic, Katarina Dunjic. New Approach to create an Effective Natural Treatments of Infections caused by Human Papillomavirus. December 2021, Journal of Molecular Docking 1(2):68-77. [CrossRef]

- Feig M, Onufriev A, Lee MS, Im W, Case DA, Brooks CL (Jan 2004). "Performance comparison of generalized born and Poisson methods in the calculation of electrostatic solvation energies for protein structures". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 25 (2): 265–84. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Pang YP (September 2007). Romesberg F (ed.). "Preference of small molecules for local minimum conformations when binding to proteins". PLOS ONE. 2 (9): e820. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..820W. [CrossRef]

- Suresh PS, Kumar A, Kumar R, Singh VP (Jan 2008). "An in silico [correction of insilico] approach to bioremediation: laccase as a case study". Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 26 (5): 845–9. [CrossRef]

- Hartshorn MJ, Verdonk ML, Chessari G, Brewerton SC, Mooij WT, Mortenson PN, Murray CW (Feb 2007). "Diverse, high-quality test set for the validation of protein-ligand docking performance". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 50 (4): 726–41. [CrossRef]

- Gohlke H, Hendlich M, Klebe G (January 2000). "Knowledge-based scoring function to predict protein-ligand interactions". Journal of Molecular Biology. 295 (2): 337–356. [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira NM, Bras NF, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ (January 2009). "MADAMM: a multistaged docking with an automated molecular modeling protocol". Proteins. 74 (1): 192–206. [CrossRef]

- Mostashari-Rad T, Arian R, Mehridehnavi A, Fassihi A, Ghasemi F (June 13, 2019). "Study of CXCR4 chemokine receptor inhibitors using QSPR andmolecular docking methodologies". Journal of Theoretical and Computational Chemistry. 178 (4). [CrossRef]

- Kitchen DB, Decornez H, Furr JR, Bajorath J (Nov 2004). "Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 3 (11): 935–49. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, V.L.S.; Gomes, J.R.B.; Ribeiro da Silva, M.D.M.C. Experimental and computational thermochemical studies of 9-R-xanthene derivatives (R = OH, COOH, CONH2). J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2012, 54, 108–117. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.M.P.F.; Freitas, V.L.S.; Gonçalves, J.F.R.; Barbosa, M.; Chickos, J.S.; Ribeiro da Silva, M.D.M.C. The influence of the hydroxy and methoxy functional groups on the energetic and structural properties of naphthaldehyde as evaluated by both experimental and computational methods. Struct. Chem. 2015, 26, 137–149. [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.W., Jr. NIST-JANAF Thermochemical Tables; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1998; pp. 1–1951. Available online: https://janaf.nist.gov/ (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Ribeiro da Silva, M.A.V.; Ribeiro da Silva, M.D.M.C.; Pilcher, G. Enthalpies of combustion of 1-hydroxynaphthalene, 2-hydroxynaphthalene, and 1,2-, 1,3-, 1,4-, and 2,3-dihydroxynaphthalenes. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1988, 20, 969–997. [CrossRef]

- Lin H, Li S, Xu R, Liu Y, Wu X, Yang W, Wei Y, Lin Y, He Z, Hui H, He K, Hu S, Zhang C, Li C, Lv G, Yuan L, Zou Y, Wang C (2022). "In situ detection of water on the Moon by the Chang'E-5 lander". Science Advances. 8 (1): eabl9174. Bibcode:2022SciA....8.9174L. [CrossRef]

- Clancy RT, Sandor BJ, García-Muñoz A, Lefèvre F, Smith MD, Wolff MJ, Montmessin F, Murchie SL, Nair H (2013). "First detection of Mars atmospheric hydroxyl: CRISM Near-IR measurement versus LMD GCM simulation of OH Meinel band emission in the Mars polar winter atmosphere". Icarus. 226 (1): 272–281. Bibcode:2013Icar..226..272T. [CrossRef]

- Kanno, Taro; Nakamura, Keisuke; Ikai, Hiroyo; Kikuchi, Katsushi; Sasaki, Keiichi; Niwano, Yoshimi (July 2012). "Literature review of the role of hydroxyl radicals in chemically-induced mutagenicity and carcinogenicity for the risk assessment of a disinfection system utilizing photolysis of hydrogen peroxide". Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 51 (1): 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Piccioni, G.; Drossart, P.; Zasova, L.; Migliorini, A.; Gérard, J.-C.; Mills, F. P.; Shakun, A.; García Muñoz, A.; Ignatiev, N.; Grassi, D.; Cottini, V.; Taylor, F. W.; Erard, S. (2008-04-01). "First detection of hydroxyl in the atmosphere of Venus". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 483 (3). EDP Sciences: L29–L33. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D; Cuendet, M; Vigo, JS; et al. (2001). "A novel cyclooxygenase-inhibitory stilbenolignan from the seeds of Aiphanes aculeata". Organic Letters. 3 (14): 2169–71. [CrossRef]

- López-Lázaro M. (2009). "Distribution and biological activities of the flavonoid luteolin". Mini Rev Med Chem. 9 (1): 31–59. [CrossRef]

- Kayoko Shimoi; Hisae Okada; Michiyo Furugori; et al. (1998). "Intestinal absorption of luteolin and luteolin 7-O-[beta]-glucoside in rats and humans". FEBS Letters. 438 (3): 220–24. [CrossRef]

- A. Ulubelen; M. Miski; P. Neuman; T. J. Mabry (1979). “Flavonoids of Salvia tomentosa (Labiatae)”. Journal of Natural Products. 42 (4): 261–63. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).