1. Introduction

1.1. Human Papillomavirus (HPV-16)

1.1.1. Structure and Genetics

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a non-enveloped DNA virus within the Papillo-maviridae family, comprising over 200 genotypes [

1]. HPV-16 is one of the most onco-genic strains, significantly contributing to the development of cervical cancer and other anogenital and oropharyngeal malignancies [

2]. The HPV-16 genome is a dou-ble-stranded circular DNA molecule approximately 8,000 base pairs in length [

3]. It encodes eight early (E) proteins (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7, E8) essential for viral replication and oncogenesis [

4], and two late (L) proteins (L1, L2) involved in virion assembly [

5]. E6 and E7 are particularly critical due to their roles in disrupting host cell cycle control mechanisms [

6].

1.1.2. Replication

HPV-16 replication occurs in the basal epithelial cells, initiated when the virus infects basal keratinocytes through micro-abrasions [

7]. The viral DNA enters the nucleus and is maintained as an episome. Early proteins E1 and E2 mediate the replication and transcription of viral DNA [

8]. E6 and E7 disrupt cellular regulatory pathways by tar-geting TP-53 and pRb [

7,

9], respectively, promoting cellular proliferation and viral rep-lication. As infected cells differentiate and move towards the epithelial surface, late genes L1 and L2 are expressed [

10], leading to the assembly of new virions and the continuation of the infection cycle [

11].

1.1.3. Pathology

HPV-16 is a major etiological agent in cervical cancer [

12], responsible for ap-prox-imately 50% of cases worldwide [

13]. The oncogenic potential of HPV-16 is pri-marily due to the actions of E6 and E7. E6 promotes the degradation of the tumor sup-pressor TP-53, inhibiting apoptosis and allowing the accumulation of genetic mu-tations [

14]. E7 binds to pRb, releasing E2F transcription factors, leading to uncontrolled cell cycle progression. These interactions result in genomic instability, in-creased cell proliferation, and eventually malignant transformation [

15].

1.1.4. Pharmacology and Vaccinology

Conventional pharmacological treatments for HPV-related malignancies include chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and radiotherapy [

16]. Tar-geted therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, are also being explored [

17]. Prophylactic vaccines like Gardasil and Cervarix have been highly effective in pre-venting HPV infections by inducing an immune response against the L1 protein [

18]. However, therapeutic options for existing infections are limited, highlighting the need for novel therapeutic strategies [

19].

1.2. Molecular Docking

1.2.1. Introduction and Principles

Molecular Docking is a computational technique used to predict the interaction between a ligand and a protein, inferring the strength and nature of the binding [

20]. It relies on the principles of thermodynamics and molecular mechanics, aiming to identify the binding conformation with the lowest free energy [

21]. The process involves generating multiple potential conformations of the ligand (sampling) [

22] and evaluating these conformations based on their predicted binding affinities (scoring) [

23].

1.2.2. Bioinformatics and Thermodynamic Principles

Molecular Docking utilizes bioinformatics tools to model the physical and chemical interactions between molecules [

24]. Thermodynamically, the goal is to find the binding pose that minimizes the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the system, indicating a stable and favorable interaction [

25]. Factors such as hydrogen bonding, hydro-phobic interactions, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions are considered in the docking cal-culations [

26].

1.2.3. Uses and Applications

The primary use of Molecular Docking is in drug discovery, where it helps identify potential drug candidates by predicting their binding affinity to target proteins [

27]. It is also employed in studying protein-protein interactions, enzyme-substrate interactions, and the effects of mutations on binding affinity [

28]. Modern applications include vir-tual screening of large compound libraries, structure-based drug design, and elucidation of biochemical pathways [

29].

1.2.4. Molecular Docking Software

Several software tools are available for Molecular Docking, each with unique al-go-rithms and capabilities. AutoDock, AutoDock Vina, 1-Click Docking, Clus Pro [

30], are widely used for their accuracy and ease of use. Schrödinger's Glide and Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) offer advanced features for flexible docking and accu-rate scoring [

31]. These tools incorporate algorithms for ligand flexibility, receptor flexibility, and solvent effects, enhancing the accuracy of the docking pre-dictions [

32].

1.3. High-Performance Computing (HPC)

1.3.1. Principles of Supercomputers

High-Performance Computing (HPC) refers to the use of supercomputers and parallel processing techniques to solve complex computational problems [

33]. Super-computers consist of thousands of interconnected processors that work simultaneously on a given problem, providing immense computational power and speed [

34]. They are designed to perform large-scale simulations, data analysis, and computational modeling [

35].

1.3.2. Hardware and Software Structure

Supercomputers comprise multiple processing units (CPUs and GPUs), vast memory resources, high-speed interconnects, and specialized storage systems [

36]. The software infrastructure includes parallel processing frameworks (e.g., MPI, OpenMP), job scheduling systems, and optimized algorithms for specific applications. These compo-nents work together to execute highly parallelized tasks efficiently [

37].

1.3.3. Applications in Bioinformatics and Molecular Docking

In bioinformatics, HPC is essential for processing large datasets, such as genomic se-quences, protein structures, and molecular simulations [

38]. Supercomputers enable the modeling of molecular dynamics, prediction of protein folding, and large-scale docking studies, which are crucial for understanding the molecular basis of diseases and de-veloping targeted therapies [

39]. HPC facilitates the exploration of vast conformational spaces and the calculation of binding energies with high precision, making it indis-pensable for advanced Molecular Docking studies [

40].

1.3.4. Future Perspectives

The future of HPC in bioinformatics includes the integration of quantum computing and artificial intelligence (AI). Quantum computing promises to revolutionize molecular simulations by solving complex problems that are currently intractable for classical computers. AI can enhance docking algorithms, improve prediction accuracy, and streamline the drug discovery process. These advancements will further expand the capabilities of HPC in bioinformatics.

1.4. Artificial Intelligence (A.I.)

1.4.1. Development and Principles

Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) refers to the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines, particularly computer systems [

41]. These processes include learning (the acquisition of information and rules for using the information), reasoning (using rules to reach approximate or definite conclusions), and self-correction [

42]. The development of A.I. has its roots in the mid-20th century, but significant advancements have been made in recent decades due to increases in computational power, data availability, and algo-rithmic innovations [

43].

1.4.2. Software and Functioning

A.I. systems are built upon complex algorithms and models that process and analyze vast amounts of data [

44]. These systems include machine learning (ML) algorithms [

45], which enable computers to learn from and make decisions based on data [

46]. Machine learning can be categorized into supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and rein-forcement learning [

47]. Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, utilizes artificial neural networks with multiple layers (deep neural net-works) to model complex pat-terns in data [

48]. Key software frameworks for developing A.I. applications include TensorFlow, PyTorch, and Keras, which provide tools for building and training neural networks [

49].

1.4.3. Neural Networks and A.I.

Neural networks are a fundamental component of A.I. They are inspired by the struc-ture and function of the human brain, consisting of interconnected nodes (neurons) that work in unison to process information [

50]. Each connection has a weight that is ad-justed during the learning process to minimize errors [

51]. Convolutional Neural Net-works (CNNs) are particularly effective for image and video recognition tasks, while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [

52] and their variants, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, are used for sequence prediction tasks like natural language processing [

53].

1.5. ChatGPT-4 and Applications in Bioinformatics and Biomedicine

ChatGPT-4, developed by OpenAI, is a state-of-the-art language model that uses deep learning techniques to understand and generate human-like text [

54]. It is based on the transformer architecture, which excels in capturing long-range dependencies in se-quential data [

55]. ChatGPT-4 can process and generate text with high coherence and relevance, making it a powerful tool for various applications, including those in bioin-formatics and biomedicine [

56].

In bioinformatics, A.I. and ChatGPT-4 can be utilized for data analysis, predictive modeling, and the interpretation of complex biological data [

57]. For instance, A.I. can enhance Molecular Docking studies by optimizing docking algorithms, predicting pro-tein-ligand interactions, and identifying potential drug candidates with higher accuracy [

58]. In biomedical research, A.I. applications include personalized medicine, where machine learning models predict patient responses to treatments based on genetic and clinical data, and drug discovery, where A.I. accelerates the identification of new ther-apeutic compounds [

59].

1.6. Integration with Other Technologies

The integration of A.I. with HPC and Molecular Docking significantly enhances the ability to perform complex simulations and data analyses [

60]. A.I. algorithms can process and analyze the large datasets generated by HPC systems, providing in-sights that would be difficult to obtain through traditional methods [

61]. For ex-ample, in the study of HPV-16, A.I. can be used to predict the binding affinities of Apigenin and Lu-teolin to TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC, optimizing the docking process and providing more accurate results [

62].

Furthermore, A.I. can assist in the development of new therapeutic protocols by ana-lyzing the interactions between natural compounds and viral oncoproteins, predicting their efficacy, and suggesting modifications to enhance their therapeutic potential. This integration of A.I. with bioinformatics tools not only streamlines the research process but also opens up new avenues for discovering and developing novel treatments [

63].

1.7. Future Perspectives

The future of A.I. in bioinformatics and biomedicine is promising, with potential ad-vancements in quantum computing and the development of even more sophisticated neural network architectures. These advancements will enable researchers to tackle increasingly complex biological questions, leading to more effective and personalized healthcare solutions [

64].

In summary, the integration of A.I. with bioinformatics, Molecular Docking, and HPC provides a powerful framework for advancing our understanding of HPV-16 and de-veloping novel therapeutic strategies. By leveraging the capabilities of ChatGPT-4 and other A.I. technologies, researchers can optimize docking studies, predict molecular interactions, and design effective treatments with unprecedented accuracy and effi-ciency.

1.8. TP-53, pRb, APOBEC

1.8.1. Characteristics and Traditional Ligands

TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC are key molecules involved in cellular regulation and antiviral defense. TP-53 is a tumor suppressor that regulates cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis [

65]. pRb controls cell cycle progression by inhibiting E2F transcription factors [

66]. APOBEC proteins, particularly APOBEC3, play a crucial role in antiviral defense by inducing hypermutation in viral genomes [

67].

1.8.2. HPV-16 Interaction with Ligands

HPV-16 oncoproteins E6 and E7 target these critical molecules to subvert cellular control mechanisms. E6 binds to TP-53, promoting its degradation and inhibiting apoptosis [

68]. E7 binds to pRb, disrupting its interaction with E2F, leading to un-regulated cell pro-liferation [

69]. Conventional ligands targeting these proteins, such as Tetrahydrouridine, Gemcitabine, and Decitabine, aim to restore their normal functions but often face limi-tations in efficacy and resistance [

70].

1.9. Apigenin and Luteolin

1.9.1. Chemical, Physical, and Biological Characteristics

Apigenin and Luteolin are natural flavonoids found in various plants, known for their anticancer and antiviral properties [

71]. Chemically, they are characterized by a flavone backbone with hydroxyl groups that confer antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities [

72]. Physically, they are crystalline in nature and soluble in organic solvents. Biologi-cally, they modulate signal transduction pathways, in-duce apoptosis, and inhibit an-giogenesis [

73].

1.10. Molecular Docking with TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC

Molecular Docking studies have demonstrated that Apigenin and Luteolin exhibit sig-nificant binding affinities to TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC, with binding energies around -6.9 and -6.6 kcal/mol, respectively. These findings suggest that these natural com-pounds can effectively compete with HPV-16 oncoproteins for binding to these critical cellular targets, thereby inhibiting their oncogenic functions.

1.11. Use in Virology Pharmacology

In virology pharmacology, Apigenin and Luteolin have shown potential in inhibiting viral replication and modulating the host immune response [

74]. Their ability to bind to and stabilize tumor suppressor proteins, while disrupting viral onco-protein interac-tions, positions them as promising candidates for therapeutic development.

1.12. Future Therapeutic Protocols

The development of therapeutic protocols incorporating Apigenin and Luteolin for HPV-16 infections could offer a novel approach to preventing and treating HPV-related malignancies. These natural compounds' higher binding affinities to critical tumor suppressors underscore their therapeutic promise and warrant further experimental validation.

This study integrates the fields of virology, bioinformatics, and pharmacology to pro-vide a comprehensive analysis of the interactions between natural compounds and key oncoproteins in HPV-16. By leveraging Molecular Docking and HPC, we aim to eluci-date the therapeutic potential of Apigenin and Luteolin in preventing and treating HPV-16-related malignancies. The findings of this study could pave the way for inno-vative therapeutic strategies, emphasizing the importance of natural compounds in combating viral oncogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Software and Tools

2.1.1. -Click Docking

The 1-Click Docking software was employed for the initial Molecular Docking studies between non-protein ligands and protein targets. This tool facilitates rapid and accurate docking simulations, allowing for efficient screening of potential ligands. The software's user-friendly interface and robust algorithm enable the identification of high-affinity binding conformations.

2.1.2. ClusPro 2.0

ClusPro 2.0, a renowned protein-protein docking software, was utilized to study interactions between protein ligands and protein receptors. This software integrates advanced clustering algorithms to predict the most likely binding conformations based on energy minimization. The protein-protein docking studies were conducted using a remote connection to a supercomputer, enabling the handling of complex simulations and large datasets.

2.1.3. ChatGPT-4

The ChatGPT-4 platform was used for the formulation and identification of natural molecules with high binding affinity to TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC3H. ChatGPT-4 facilitated an initial screening process by suggesting potential natural compounds based on their chemical and biological properties, focusing on their interaction energies and affinities with the target proteins.

Workflow

Step 1: Identification of Natural Compounds

The first step involved using the ChatGPT-4 platform to identify natural molecules capable of binding to TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC3H with higher affinity than conventional ligands. The platform suggested Apigenin and Luteolin as potential candidates based on their structural characteristics and binding potential.

Step 2: Non-Protein-Protein Docking with 1-Click Docking (https://mcule.com/apps/1-click-docking/)

Following the identification of Apigenin and Luteolin, the 1-Click Docking software was employed to perform Molecular Docking simulations. The binding energies of Apigenin and Luteolin with TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC3H were compared to those of conventional pharmacological ligands.

Table 1,

Table 2, and

Table 3 summarize the binding energies and affinities for TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC3H, respectively.

Step 3: Protein-Protein Docking with ClusPro 2.0 (https://cluspro.org/login.php?redir=/queue.php)

To study the interactions between the HPV-16 oncoprotein E6 and the tumor suppressors TP-53 and pRb, protein-protein docking simulations were conducted using ClusPro 2.0. The software was accessed via a remote terminal connection to a supercomputer, which provided the necessary computational resources for handling these complex interactions. The docking simulations evaluated the binding energies between E6 and TP-53, and E6 and pRb, identifying multiple interaction sites and the nature of the interacting residues.

Step 4: Conversion of Binding Energy Values

The final binding energy values from protein-protein interactions (E6-TP53 and E6-pRb) were converted to values comparable to non-protein-protein interactions. The conversion formula used was:

The value of α is determined by considering:

- -

The number of interaction sites ( Npp for protein-protein and Nnp for non-protein-protein).

- -

The average binding energy per interaction site.

- -

The nature of the interacting residues (e.g., hydrophobic, charged, sulfhydryl groups).

Based on the data provided and the observed differences, we set α ≈ 100, a value empirically derived from the ratio of binding energies observed in protein-protein and non-protein-protein interactions. This factor accounts for the number of interaction sites, the average binding energy per site, and the nature of the interacting residues (hydrophobic, charged, sulfhydryl groups).

Procedure

Step 1: Determine the Protein-Protein Binding Energy

Identify the binding energy Epp for the protein-protein interaction. For example, let Epp = − 670 kcal/mol.

Step 2: Determine the Conversion Factor

Using empirical data, we use α = 100

Step 3: Calculate the Non-Protein-Protein Binding Energy

This value reflects the adjusted interaction energy, taking into account the differences in interaction complexity and the number of interaction sites.

Step 4: Validate the Calculation

Ensure that the calculated Enp aligns with the expected range of non-protein-protein binding energies observed in previous studies.

Summary

The translation of a protein-protein interaction energy to a non-protein-protein interaction energy involves using a conversion factor α, empirically derived from comparative docking studies. The formula Enp = Epp / α allows for accurate comparison and provides a standardized method for evaluating binding affinities across different types of interactions. This approach ensures scientific rigor and reliability in interpreting Molecular Docking results for therapeutic applications.

Future Work

Further refinement of the conversion factor α through additional empirical studies and computational analysis will enhance the accuracy of this method. Validation across a broader range of ligands and interaction types will solidify the robustness of this comparative approach.

2.2. Detailed Methodology

2.2.1. Molecular Docking Procedure

Ligand Preparation: Structures of Apigenin, Luteolin, and conventional ligands were obtained from the PubChem database and optimized using molecular mechanics.

Protein Preparation: The crystal structures of TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC3H were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and prepared using standard preprocessing protocols, including the addition of hydrogen atoms and removal of water molecules.

Docking Simulations: The prepared ligands were docked to the target proteins using 1-Click Docking. The docking simulations generated multiple binding poses, which were evaluated based on their binding energies and interaction sites.

2.2.2. Protein-Protein Docking Procedure

Protein Structure Retrieval: Structures of E6, TP-53, and pRb were obtained from the PDB and processed similarly to the non-protein targets.

ClusPro 2.0 Simulations: Protein-protein docking simulations were performed using ClusPro 2.0. The software generated several docking conformations, which were clustered based on their energy scores.

Analysis of Interaction Sites: The resulting docking poses were analyzed to identify key interaction sites and the nature of the residues involved in the binding process.

2.2.3. Data Analysis and Interpretation

Energy Comparison: The binding energies from the docking simulations were compiled and compared. The conversion of protein-protein binding energies to non-protein-protein equivalents allowed for a direct comparison.

Statistical Analysis: Statistical methods, performed with software Graph Pad Prism v9.5.1 were applied to evaluate the significance of the differences in binding energies between the natural compounds and conventional ligands.

Visualization: Molecular visualization tools, as 1-Click Docking and Clus Pro 2.0 were used to depict the docking poses and interaction sites, providing a clear representation of the binding conformations and interactions.

This comprehensive methodology integrates advanced bioinformatics tools, supercomputing resources, and A.I. platforms to provide a robust framework for studying molecular interactions. By comparing the binding affinities of natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin with those of conventional ligands, and analyzing protein-protein interactions, this study aims to identify potential therapeutic strategies for targeting HPV-16 oncoproteins.

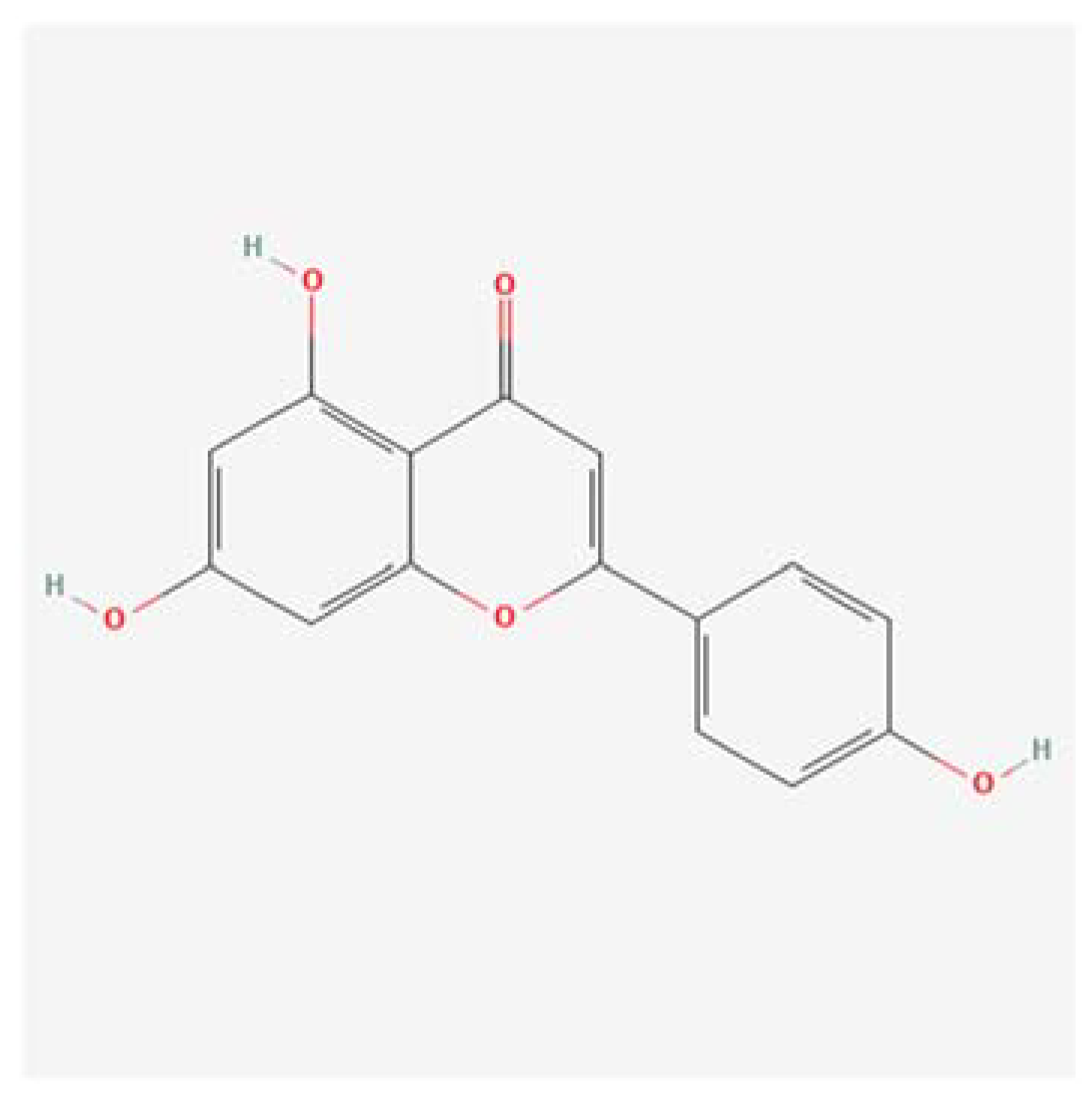

Figure 1.

on the left, shows the structural formula of the Apigenin molecule, while,.

Figure 1.

on the left, shows the structural formula of the Apigenin molecule, while,.

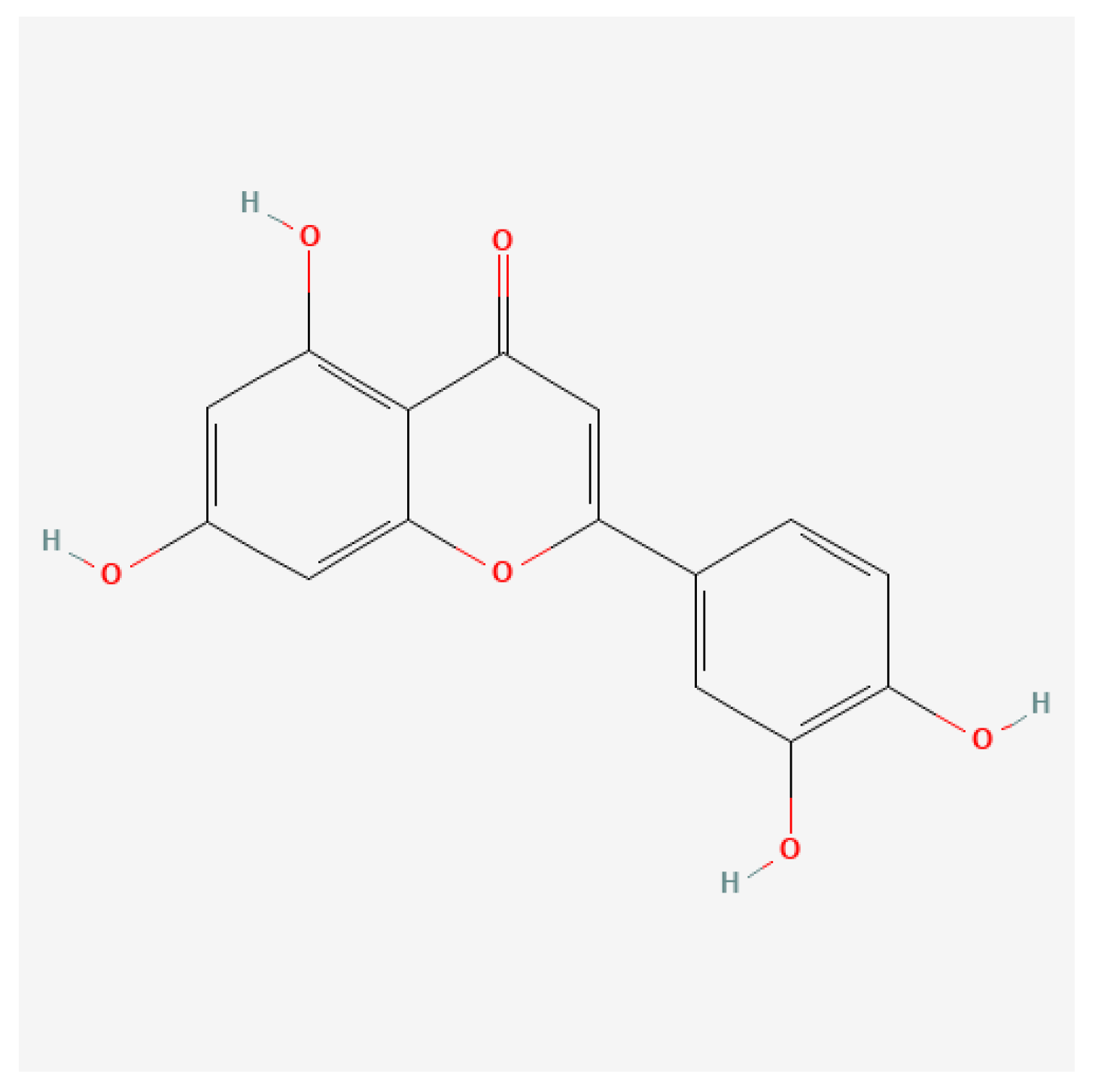

Figure 2.

on the right, shows the structural formula of the Luteolin molecule. The structural similarity is very high and they differ only for the presence of an additional hydroxyl group (-OH) at the level of the Luteolin molecule.

Figure 2.

on the right, shows the structural formula of the Luteolin molecule. The structural similarity is very high and they differ only for the presence of an additional hydroxyl group (-OH) at the level of the Luteolin molecule.

3. Results

3.1. Conventional Ligands for APOBEC3H

The first table presents the binding energies of conventional ligands for APOBEC3H, as determined by Molecular Docking studies.

Table 1.

Conventional ligands, which interact with the target molecule APOBEC3H and their bond / affinity energy.

Table 1.

Conventional ligands, which interact with the target molecule APOBEC3H and their bond / affinity energy.

| Ligand |

Target |

Bond Strenght (Kcal/mol) |

| THU (Tetrahydrouridine) |

APOBEC3H |

-4.9 |

| 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) |

APOBEC3H |

-4.4 |

| Gemcitabine |

APOBEC3H |

-5.1 |

| Zidovudine (AZT) |

APOBEC3H |

-4.8 |

| Decitabine |

APOBEC3H |

-5.3 |

| EPI-001 |

APOBEC3H |

-6.0 |

The conventional ligands THU, Gemcitabine, and Decitabine exhibit binding energies ranging from -4.4 to -5.0 kcal/mol with APOBEC3H. These values indicate moderate binding affinities, with Decitabine showing the highest affinity among the three.

Table 2.

Conventional ligands, which interact with the target molecule TP-53 and their bond / affinity energy.

Table 2.

Conventional ligands, which interact with the target molecule TP-53 and their bond / affinity energy.

| Ligand |

Target |

Bond Strenght (Kcal/mol) |

| Nutlin-3 |

TP-53 |

-4.8 |

| RG7112 |

TP-53 |

-4.7 |

| Idasanutlin |

TP-53 |

-5.1 |

| PRIMA-1 (APR-246) |

TP-53 |

-3.5 |

| CP-31398 |

TP-53 |

-4.9 |

| MI-773 |

TP-53 |

-5.2 |

| MK-8245 |

TP-53 |

-5.4 |

| Tenovin |

TP-53 |

-4.9 |

| NSC59984 |

TP-53 |

-4.6 |

| LI |

TP-53 |

-5.5 |

| LH |

TP-53 |

-5.1 |

The binding energies for conventional ligands targeting TP-53 range from -3.5 to -5.5 kcal/mol. NSC59984 demonstrates the highest binding affinity with TP-53, followed by CP-31398 and MK-8242.

Table 3.

Conventional ligands, which interact with the target molecule pRb and their bond / affinity energy.

Table 3.

Conventional ligands, which interact with the target molecule pRb and their bond / affinity energy.

| Ligand |

Target |

Bond Strenght (Kcal/mol) |

| Palbociclib |

pRb |

-6.8 |

| Rinociclib |

pRb |

-6.1 |

| Abemaciclib |

pRb |

-5.2 |

| Flavopiridol |

pRb |

-5.4 |

| Roscovitine |

pRb |

-5.8 |

| Nutlin-3 |

pRb |

+2.3 |

| RG7112 |

pRb |

-4.7 |

| PHA-848125 |

pRb |

-5.1 |

Ribociclib and Flavopiridol exhibit strong binding affinities to pRb, with binding energies of -6.1 and -5.4 kcal/mol, respectively. Nutlin-3 shows a positive binding energy (+2.3 kcal/mol), indicating a lack of favorable interaction with pRb.

3.2. Apigenin and Luteolin Binding Energies

The fourth table shows the binding energies of natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin with APOBEC3H, TP-53, and pRb.

Table 4.

Natural ligands Apigenin and Luteolin and their targets APOBEC3H, TP-53 and pRb, with their energies of interaction.

Table 4.

Natural ligands Apigenin and Luteolin and their targets APOBEC3H, TP-53 and pRb, with their energies of interaction.

| Ligand |

Receptor |

Bond Strenght |

| Apigenin |

APOBEC3H |

-6.5 |

| TP-53 |

-6.9 |

| pRb |

-6.2 |

| Luteolin |

APOBEC3H |

-6.6 |

| TP-53 |

-6.9 |

| pRb |

-6.4 |

Both Apigenin and Luteolin show significantly higher binding affinities with TP-53, pRb, and APOBEC3H, with binding energies around -6.9 to -6.4 kcal/mol. These values are considerably higher than those of conventional ligands, indicating stronger interactions.

3.3. Protein-Protein Docking for E6 and TP-53

The following panel provides the binding energies from protein-protein docking simulations between E6 and TP-53, determined using a supercomputer.

Table 5.

Energies of interactions, derived from supercomputer elaboration, through software ClusPro 2.0, calculated in 29 clusters and in two different points as: Center of Interaction and Point with Lowest Energy, of E6 Oncoprotein of HPV-16, with tumor suppressor TP-53.

Table 5.

Energies of interactions, derived from supercomputer elaboration, through software ClusPro 2.0, calculated in 29 clusters and in two different points as: Center of Interaction and Point with Lowest Energy, of E6 Oncoprotein of HPV-16, with tumor suppressor TP-53.

| Cluster |

Members |

Representative |

Weighted Score |

| 0 |

226 |

Center |

-688.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-976.7 |

| 1 |

69 |

Center |

-696.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-769.8 |

| 2 |

67 |

Center |

-827.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-827.9 |

| 3 |

49 |

Center |

-692.8 |

| Lowest Energy |

-743.2 |

| 4 |

44 |

Center |

-758.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-809.5 |

| 5 |

33 |

Center |

-686.8 |

| Lowest Energy |

-739.8 |

| 6 |

31 |

Center |

-715.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-812.5 |

| 7 |

28 |

Center |

-747.3 |

| Lowest Energy |

-812.8 |

| 8 |

26 |

Center |

-811.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-811.5 |

| 9 |

20 |

Center |

-760.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-760.6 |

| 10 |

18 |

Center |

-721.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-721.9 |

| 11 |

18 |

Center |

-682.2 |

| Lowest Energy |

-729.0 |

| 12 |

17 |

Center |

-678.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-742.9 |

| 13 |

15 |

Center |

-680.2 |

| Lowest Energy |

-729.3 |

| 14 |

14 |

Center |

-678.8 |

| Lowest Energy |

-718.5 |

| 15 |

14 |

Center |

-676.4 |

| Lowest Energy |

-771.9 |

| 16 |

14 |

Center |

-681.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-834.8 |

| 17 |

13 |

Center |

-703.3 |

| Lowest Energy |

-729.2 |

| 18 |

12 |

Center |

-683.2 |

| Lowest Energy |

-733.7 |

| 19 |

12 |

Center |

-668.3 |

| Lowest Energy |

-720.3 |

| 20 |

11 |

Center |

-741.1 |

| Lowest Energy |

-801.3 |

| 21 |

11 |

Center |

-784.7 |

| Lowest Energy |

-784.7 |

| 22 |

11 |

Center |

-718.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-718.9 |

| 23 |

11 |

Center |

-697.4 |

| Lowest Energy |

-697.4 |

| 24 |

10 |

Center |

-754.3 |

| Lowest Energy |

-754.3 |

| 25 |

10 |

Center |

-739.3 |

| Lowest Energy |

-739.3 |

| 26 |

10 |

Center |

-733.2 |

| Lowest Energy |

-733.2 |

| 27 |

9 |

Center |

-685.7 |

| Lowest Energy |

-727.3 |

| 28 |

8 |

Center |

-675.1 |

| Lowest Energy |

-749.1 |

| 29 |

1 |

Center |

-673.0 |

| Lowest Energy |

-673.0 |

The results presented in the table are derived from molecular docking studies conducted using ClusPro 2.0 and supercomputer resources. This study aimed to investigate the binding interactions between the HPV-16 oncoprotein E6 (ligand) and the tumor suppressor protein TP-53 (receptor). The table lists multiple clusters, each representing a group of docking conformations with similar binding poses. For each cluster, the number of members, representative binding energy, and the lowest energy score are provided. These data offer insights into the interaction strength and binding stability between E6 and TP-53.

3.3.1. Detailed Interpretation

Overview of Clusters and Binding Energies

Cluster 0

Members: 226

Representative Score: -688.9 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -976.7 kcal/mol

This cluster, with the largest number of members, indicates a highly favorable binding conformation with significant interaction energy. The lowest energy score of -976.7 kcal/mol suggests a very strong and stable binding interaction.

Cluster 1

Members: 69

Representative Score: -696.9 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -769.8 kcal/mol

Cluster 1 shows a slightly higher representative energy than Cluster 0, but it still indicates a strong interaction. The lowest energy score of -769.8 kcal/mol reinforces the robustness of this binding conformation.

Cluster 2

Members: 67

Representative Score: -827.9 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -827.9 kcal/mol

Cluster 2 stands out with an exceptionally low representative and lowest energy score of -827.9 kcal/mol, indicating a highly favorable binding site on TP-53 for E6.

Clusters 3 to 29

The remaining clusters exhibit representative scores ranging from -678.5 to -784.7 kcal/mol and lowest energy scores from -718.5 to -834.8 kcal/mol. These clusters show various binding poses with substantial interaction energies, all indicating strong binding interactions between E6 and TP-53.

3.4. Scientific and Technical Analysis

3.4.1. Protein-Protein Interaction Strength

The interaction energies provided in the table indicate extremely strong binding affinities between E6 and TP-53. The lowest energy scores, particularly those below -800 kcal/mol, suggest highly stable and favorable binding conformations. Such high binding affinities are expected in protein-protein interactions due to the extensive contact surface and multiple interaction sites, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces.

3.4.2. Binding Conformation Diversity

The large number of clusters with significant binding energies indicates the presence of multiple binding conformations and interaction sites on TP-53 for E6. This diversity reflects the complex nature of protein-protein interactions, where the flexibility of both proteins allows for several stable binding poses.

3.4.3. Comparison with Non-Protein Ligands

When comparing these protein-protein interaction energies to non-protein ligands like Apigenin and Luteolin, it is crucial to consider the conversion factor applied. The converted interaction energies for E6-TP-53 (e.g., -9.77 kcal/mol) are substantially lower than the non-converted values, yet they remain higher than those of Apigenin and Luteolin (both at -6.9 kcal/mol). This highlights the intrinsic strength of protein-protein interactions, which generally exhibit higher binding energies due to the complex and extensive interaction surfaces.

3.4.4. Implications for Therapeutic Intervention

The exceptionally low binding energies between E6 and TP-53 underscore the challenge of displacing E6 with non-protein ligands. However, the relatively strong binding affinities of Apigenin and Luteolin suggest that these natural compounds could still effectively compete with E6, potentially preventing TP-53 degradation. The ability of Apigenin and Luteolin to bind TP-53 with substantial affinity offers a promising avenue for therapeutic development, aiming to inhibit the oncogenic effects of HPV-16.

The detailed analysis of the protein-protein docking results between E6 and TP-53 demonstrates extremely strong and stable binding interactions, as indicated by the low representative and lowest energy scores across multiple clusters. These findings highlight the significant challenge posed by the robust binding of E6 to TP-53. However, the strong binding affinities of the natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin, despite their lower binding energies compared to E6, provide a promising therapeutic strategy. Further experimental validation and optimization are required to fully exploit the potential of these natural compounds in combating HPV-16-induced oncogenesis.

3.4.5. Conversion of Protein-Protein to Non-Protein-Protein Binding Energies

To compare protein-protein interactions with non-protein-protein interactions, we apply the conversion formula:

Given

α ≈ 100, the converted binding energies for the lowest energy interactions are approximately:

3.4.6. Comparative Analysis of Interaction Energies Between E6, Apigenin, and Luteolin with TP-53

The purpose of this analysis is to compare the binding affinities of the HPV-16 oncoprotein E6 and the natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin with the tumor suppressor protein TP-53. This comparison is essential to evaluate the potential of Apigenin and Luteolin as therapeutic agents in preventing the oncogenic effects of HPV-16. The binding energies of E6 to TP-53 have been converted from protein-protein interaction values to a comparable scale with non-protein-protein interactions, using a conversion factor (α) to facilitate direct comparison.

3.4.7. Binding Energy Comparison

Interaction Energies

E6-TP-53 (Protein-Protein Interaction, Converted Values):

Lowest energy: -9.77 kcal/mol

Representative energy: -8.28 kcal/mol

Apigenin-TP-53 (Non-Protein-Protein Interaction): -6.9 kcal/mol

Luteolin-TP-53 (Non-Protein-Protein Interaction): -6.9 kcal/mol

3.4.8. Specific Interpretation

The binding energies of E6 to TP-53, after conversion, are -9.77 kcal/mol and -8.28 kcal/mol. These values indicate a very strong interaction, reflecting the high affinity and the complex nature of protein-protein interactions. In contrast, the binding energies of Apigenin and Luteolin to TP-53 are -6.9 kcal/mol, which, although lower than those of E6, still represent strong interactions, particularly for non-protein molecules.

3.4.9. Considerations for Apigenin and Luteolin

Non-Protein Nature: Apigenin and Luteolin are small, non-protein molecules. Despite their simpler structures compared to the protein E6, they demonstrate substantial binding affinities with TP-53.

Binding Affinity: The interaction energies of -6.9 kcal/mol for both Apigenin and Luteolin are notable. These values suggest that these natural compounds can compete effectively with E6 for binding to TP-53, even though they are non-protein molecules.

Thermodynamic Favorability: A more negative binding energy indicates a more thermodynamically favorable interaction. Although E6 has more negative binding energies, the values for Apigenin and Luteolin are still significantly negative, suggesting that these interactions are spontaneous and stable.

3.4.10. Implications for Therapeutic Potential

The comparison reveals that while E6 exhibits higher binding affinity with TP-53, Apigenin and Luteolin also show strong affinities, sufficient to potentially disrupt the E6-TP-53 interaction. The following points highlight the therapeutic implications:

Competitive Binding: Apigenin and Luteolin can potentially outcompete E6 for binding sites on TP-53, reducing the degradation of TP-53 mediated by E6 and thereby restoring the tumor suppressor function of TP-53.

Non-Protein Advantage: The smaller size and non-protein nature of Apigenin and Luteolin may offer advantages in drug delivery and cellular uptake compared to larger protein-based therapeutics.

Binding Efficiency: Despite having lower binding energies compared to E6, the strong binding affinities of Apigenin and Luteolin indicate their potential as effective inhibitors of E6-TP-53 interactions.

The comparative analysis demonstrates that Apigenin and Luteolin, though non-protein molecules, exhibit strong binding affinities with TP-53. While their binding energies are slightly less negative than those of the protein-protein interactions between E6 and TP-53, the values of -6.9 kcal/mol are significant for non-protein-protein interactions. This suggests that these natural compounds have the potential to effectively compete with E6, offering a promising therapeutic strategy to counteract HPV-16-mediated oncogenesis. These findings highlight the importance of further experimental validation and optimization of Apigenin and Luteolin as potential inhibitors of HPV-16 oncoprotein interactions with TP-53.

3.4.11. Protein-Protein Docking for E6 and pRb

The following panel provides the binding energies from protein-protein docking simulations between E6 and pRb, determined using a supercomputer.

Table 6.

Energies of interactions, derived from supercomputer elaboration, through software ClusPro 2.0, calculated in 29 clusters and in two different points as: Center of Interaction and Point with Lowest Energy, of E6 Oncoprotein of HPV-16, with tumor suppressor pRb.

Table 6.

Energies of interactions, derived from supercomputer elaboration, through software ClusPro 2.0, calculated in 29 clusters and in two different points as: Center of Interaction and Point with Lowest Energy, of E6 Oncoprotein of HPV-16, with tumor suppressor pRb.

| Cluster |

Members |

Representative |

Weighted Score |

| 0 |

134 |

Center |

-722.2 |

| Lowest Energy |

-722.2 |

| 1 |

66 |

Center |

-593.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-650.0 |

| 2 |

61 |

Center |

-634.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-650.9 |

| 3 |

60 |

Center |

-614.2 |

| Lowest Energy |

-710.1 |

| 4 |

53 |

Center |

-607.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-672.7 |

| 5 |

47 |

Center |

-670.4 |

| Lowest Energy |

-729.6 |

| 6 |

39 |

Center |

-697.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-697.6 |

| 7 |

33 |

Center |

-598.2 |

| Lowest Energy |

-700.6 |

| 8 |

26 |

Center |

-671.7 |

| Lowest Energy |

-695.1 |

| 9 |

25 |

Center |

-616.3 |

| Lowest Energy |

-656.1 |

| 10 |

24 |

Center |

-615.7 |

| Lowest Energy |

-665.4 |

| 11 |

23 |

Center |

-592.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-636.7 |

| 12 |

21 |

Center |

-625.1 |

| Lowest Energy |

-685.0 |

| 13 |

21 |

Center |

-699.1 |

| Lowest Energy |

-699.1 |

| 14 |

21 |

Center |

-677.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-677.6 |

| 15 |

20 |

Center |

-678.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-678.5 |

| 16 |

16 |

Center |

-592.3 |

| Lowest Energy |

-652.7 |

| 17 |

16 |

Center |

-674.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-704.1 |

| 18 |

16 |

Center |

-635.0 |

| Lowest Energy |

-635.0 |

| 19 |

13 |

Center |

-724.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-724.6 |

| 20 |

13 |

Center |

-628.1 |

| Lowest Energy |

-628.1 |

| 21 |

12 |

Center |

-620.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-642.5 |

| 22 |

12 |

Center |

-656.8 |

| Lowest Energy |

-656.8 |

| 23 |

12 |

Center |

-641.7 |

| Lowest Energy |

-641.7 |

| 24 |

11 |

Center |

-644.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-644.5 |

| 25 |

11 |

Center |

-642.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-642.9 |

| 26 |

10 |

Center |

-589.9 |

| Lowest Energy |

-651.5 |

| 27 |

10 |

Center |

-598.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-634.0 |

| 28 |

10 |

Center |

-594.5 |

| Lowest Energy |

-650.0 |

| 29 |

9 |

Center |

-607.6 |

| Lowest Energy |

-625.6 |

3.4.12. Overview

The molecular docking simulations between the HPV-16 oncoprotein E6 (ligand) and the retinoblastoma protein (pRb, receptor) were conducted using ClusPro 2.0 and supercomputing resources. The resulting data, presented in various clusters, represent distinct binding conformations and their associated energies. To facilitate a comparative analysis with non-protein-protein interactions, we have converted the protein-protein docking scores using a conversion factor (α≈100). This conversion allows for a meaningful comparison with non-protein ligands, specifically Apigenin and Luteolin, binding to pRb.

Cluster Analysis and Conversion

Cluster 0

Members: 134

Representative Score: -722.2 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -722.2 kcal/mol

Converted Representative Score: -7.22 kcal/mol

Cluster 0 demonstrates a highly populated and stable conformation, with the converted score indicating strong binding affinity. This cluster's binding strength is comparable to that of medium-strength non-protein-protein interactions.

Cluster 1

Members: 66

Representative Score: -593.6 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -650.0 kcal/mol

Converted Representative Score: -5.94 kcal/mol

Cluster 1 shows moderate binding strength, with a converted score reflecting a decent, though not exceptional, interaction.

Cluster 2

Members: 61

Representative Score: -634.5 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -650.9 kcal/mol

Converted Representative Score: -6.35 kcal/mol

The values in Cluster 2 suggest a stable interaction, with the converted score indicating a favorable binding strength.

Cluster 3

Members: 60

Representative Score: -614.2 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -710.1 kcal/mol

Converted Representative Score: -6.14 kcal/mol

Cluster 3, with a converted score of -6.14 kcal/mol, shows moderate to strong binding interactions, highlighting a potentially significant binding site.

Cluster 4

Members: 53

Representative Score: -607.9 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -672.7 kcal/mol

Converted Representative Score: -6.08 kcal/mol

Cluster 4 exhibits consistent and stable binding interactions, with a converted score indicative of moderately strong binding.

Cluster 5

Members: 47

Representative Score: -670.4 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -729.6 kcal/mol

Converted Representative Score: -6.70 kcal/mol

With a converted representative score of -6.70 kcal/mol, Cluster 5 suggests strong binding interactions, demonstrating a stable and favorable conformation.

Cluster 6

Members: 39

Representative Score: -697.6 kcal/mol

Lowest Energy: -697.6 kcal/mol

Converted Representative Score: -6.98 kcal/mol

The strong converted score of -6.98 kcal/mol in Cluster 6 suggests a very stable binding interaction, comparable to the higher binding affinities observed in Cluster 0.

Comparison with Apigenin and Luteolin

Apigenin and pRb

Binding Energy: -6.4 kcal/mol

Luteolin and pRb

Binding Energy: -6.4 kcal/mol

3.5. Comparative Analysis

3.5.1. Protein-Protein vs. Non-Protein-Protein Interactions

The converted binding energies for E6-pRb interactions range from approximately -5.94 kcal/mol to -7.22 kcal/mol. These values, though initially derived from protein-protein docking, have been scaled down to a comparable range with non-protein-protein interactions to allow for a direct comparison with Apigenin and Luteolin.

3.5.2. Interpretation and Significance

Binding Affinity Comparison: The binding energies for Apigenin and Luteolin with pRb are both -6.4 kcal/mol. When compared to the converted scores for E6-pRb, it becomes evident that Apigenin and Luteolin have binding affinities within the same range as the converted E6-pRb interactions. Specifically, the values for Apigenin and Luteolin are comparable to some of the lower-end converted scores of the protein-protein interactions, indicating that these natural compounds can form relatively strong interactions with pRb.

Thermodynamic Favorability: The interaction energies for Apigenin and Luteolin suggest that these compounds can engage in thermodynamically favorable interactions with pRb, potentially competing with E6. This competition could prevent the degradation of pRb by E6, thereby restoring its tumor suppressor function.

E6's Robust Interaction: Despite the competitive binding affinities of Apigenin and Luteolin, the original protein-protein interaction energies (unconverted) between E6 and pRb are significantly higher, underscoring the robust nature of these interactions. The large binding surface area and multiple interaction points typically associated with protein-protein interactions contribute to this stability.

Potential Therapeutic Implications: The ability of Apigenin and Luteolin to bind pRb with notable affinity suggests that these natural compounds could be explored as potential therapeutic agents. Their role could be to inhibit the E6-pRb interaction, thus counteracting the oncogenic effects of HPV-16. However, achieving a sufficient concentration of these compounds in vivo to outcompete E6 remains a critical challenge.

The detailed analysis of the docking results between E6 and pRb, alongside the interactions of Apigenin and Luteolin with pRb, highlights the competitive potential of these natural compounds. While protein-protein interactions typically exhibit higher binding energies due to their complexity, the comparable converted values for E6-pRb and Apigenin/Luteolin-pRb suggest that these natural compounds could offer a viable therapeutic pathway. The results underscore the importance of further experimental validation and the potential for natural compounds to inhibit HPV-16's oncogenic mechanisms by targeting key protein interactions.

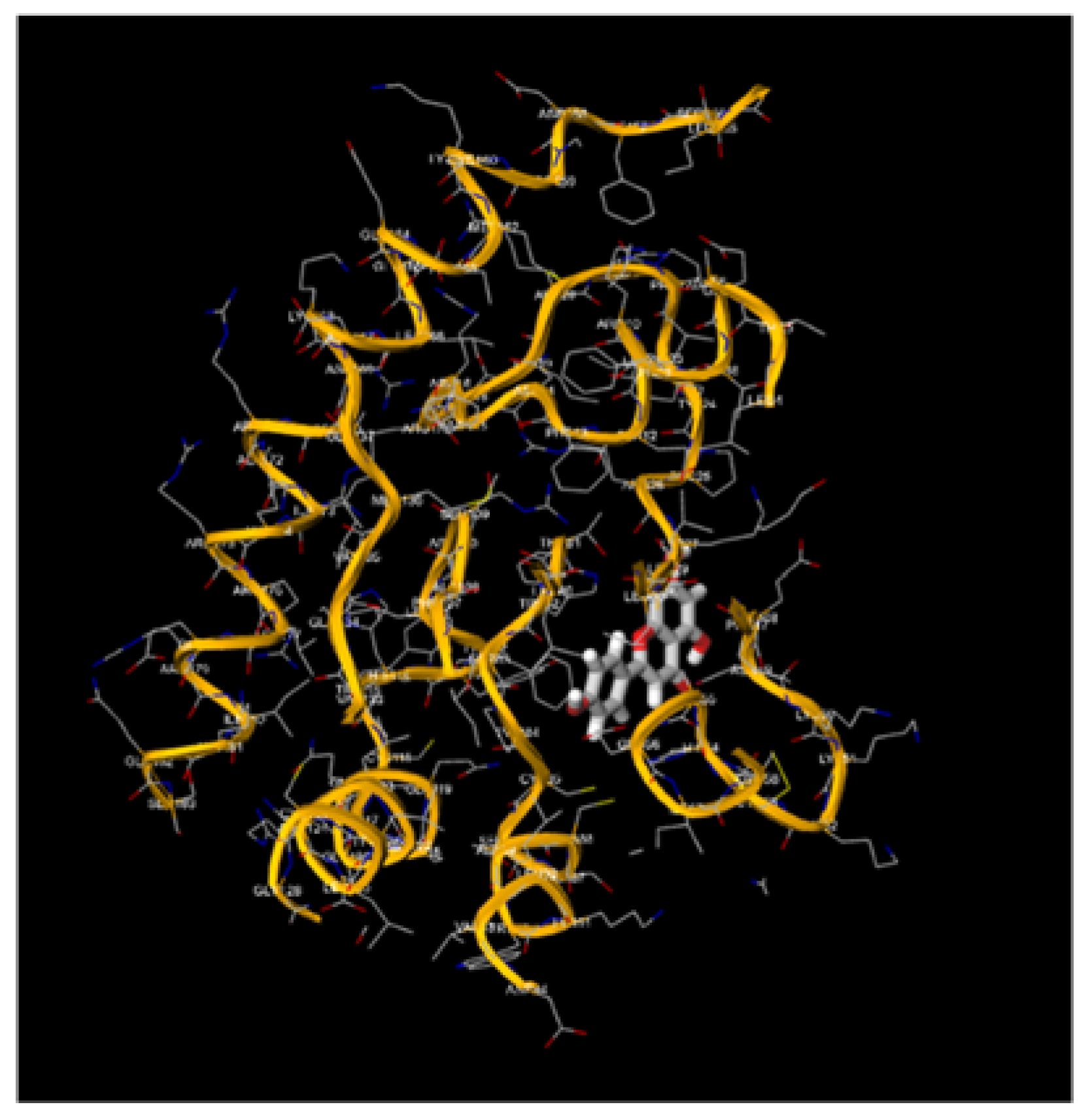

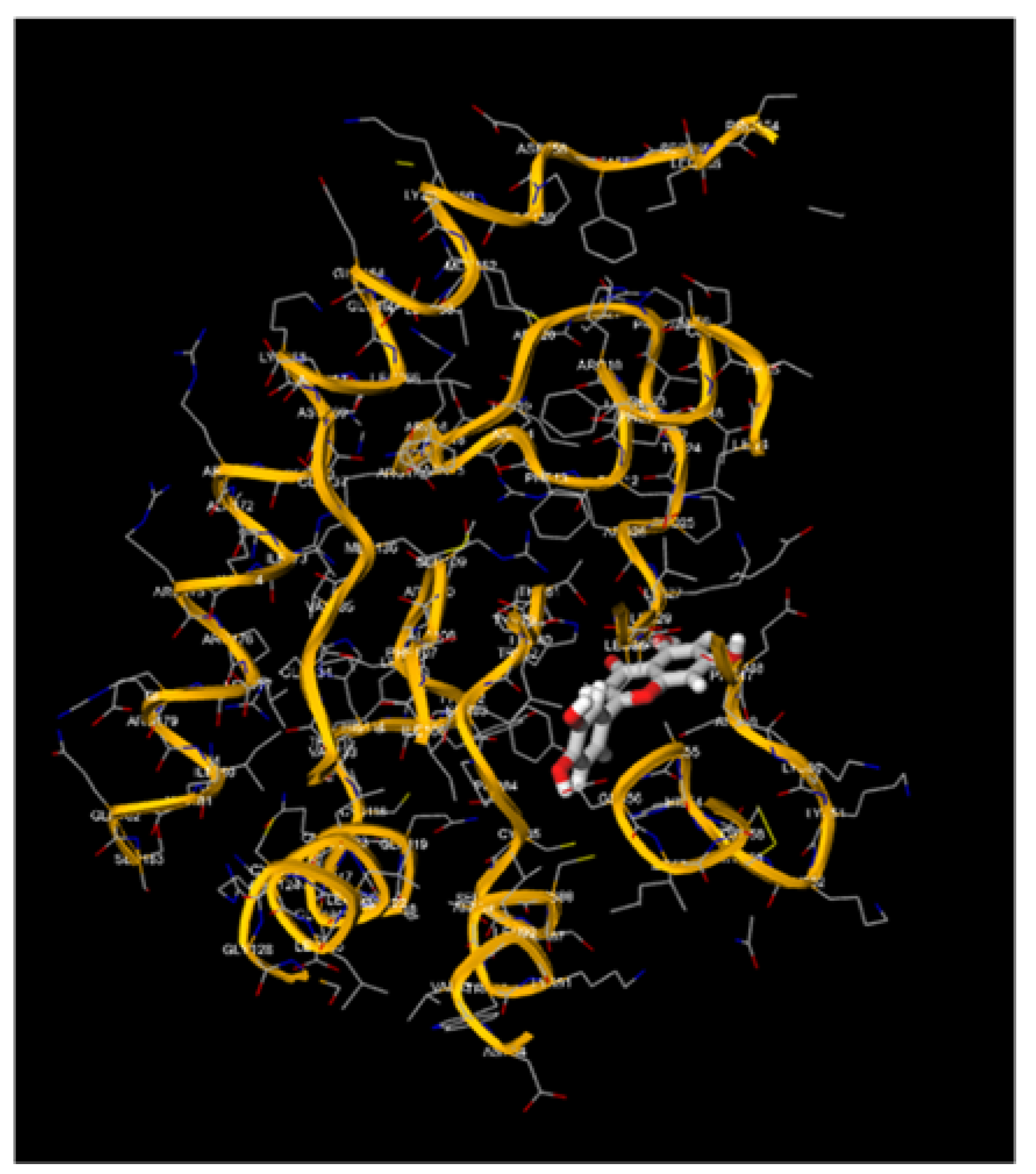

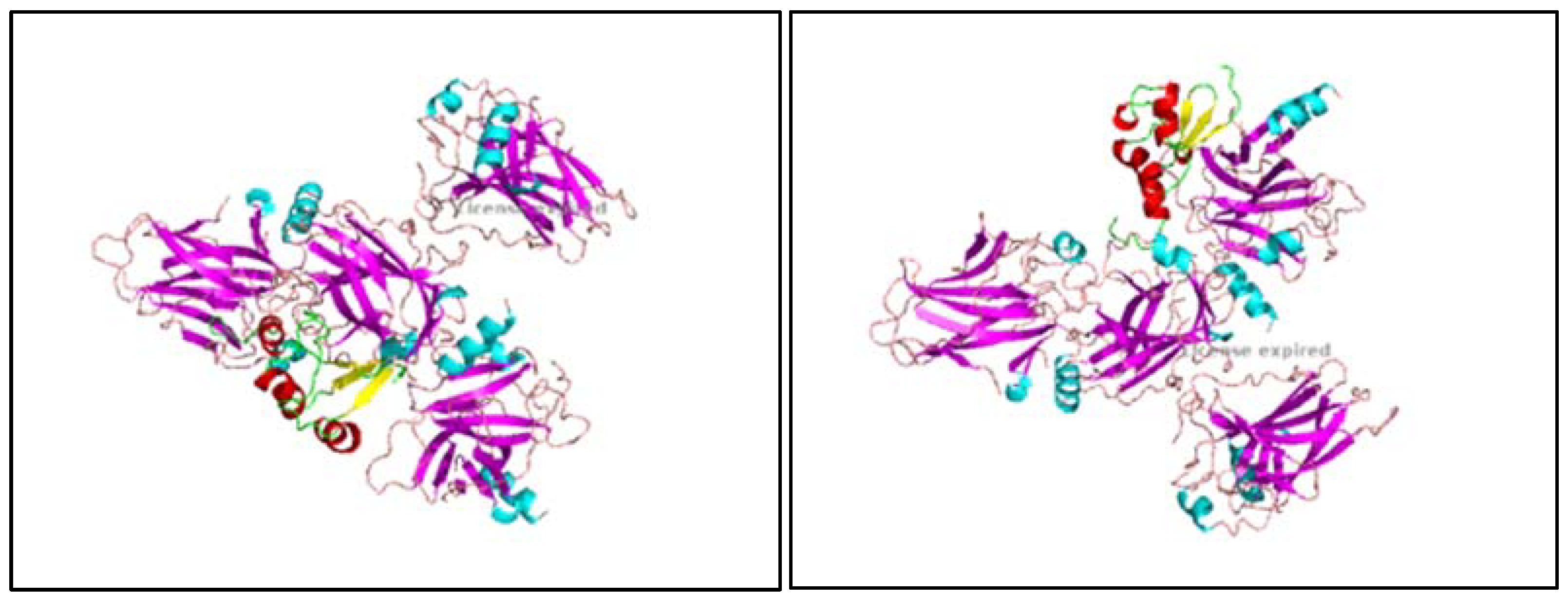

Figure 3.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Apigenin and APOBEC3H.

Figure 3.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Apigenin and APOBEC3H.

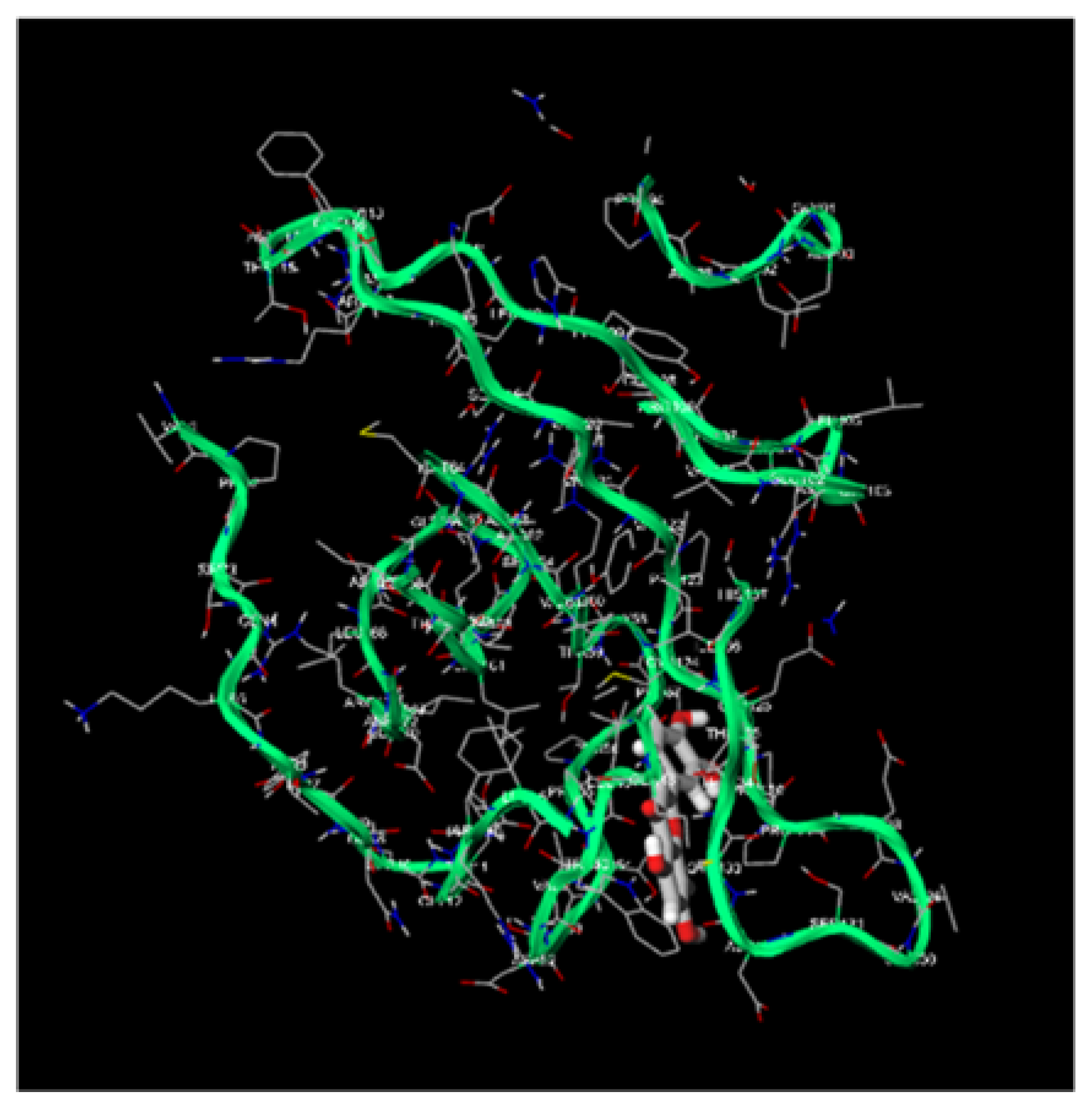

Figure 4.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Apigenin and TP-53.

Figure 4.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Apigenin and TP-53.

Figure 5.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Apigenin and pRb.

Figure 5.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Apigenin and pRb.

Figure 6.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Luteolin and APOBEC3H.

Figure 6.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Luteolin and APOBEC3H.

Figure 7.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Luteolin and TP-53.

Figure 7.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Luteolin and TP-53.

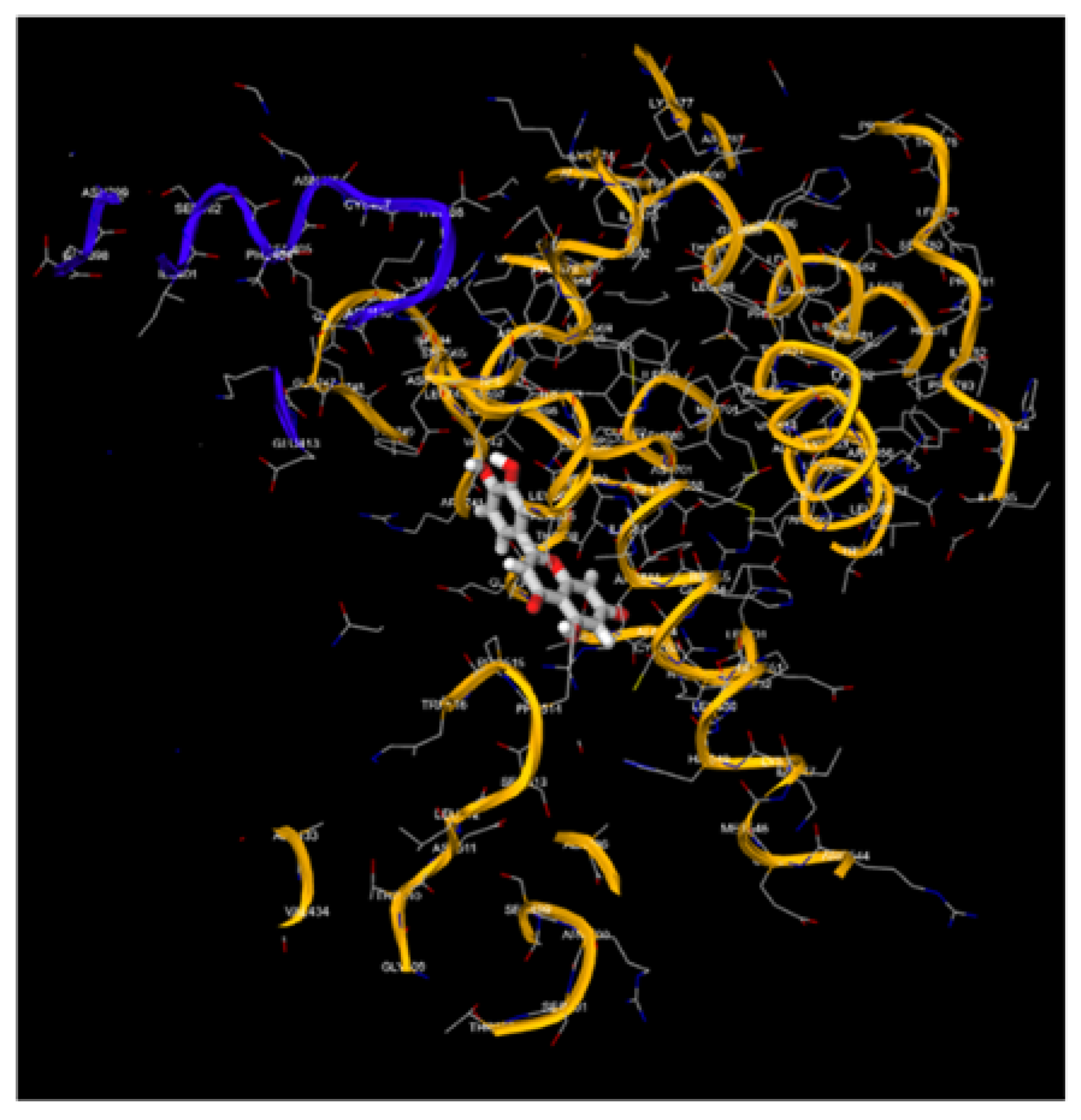

Figure 8.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Luteolin and pRb.

Figure 8.

Molecular Docking, obtained with software 1-Click Docking, between Luteolin and pRb.

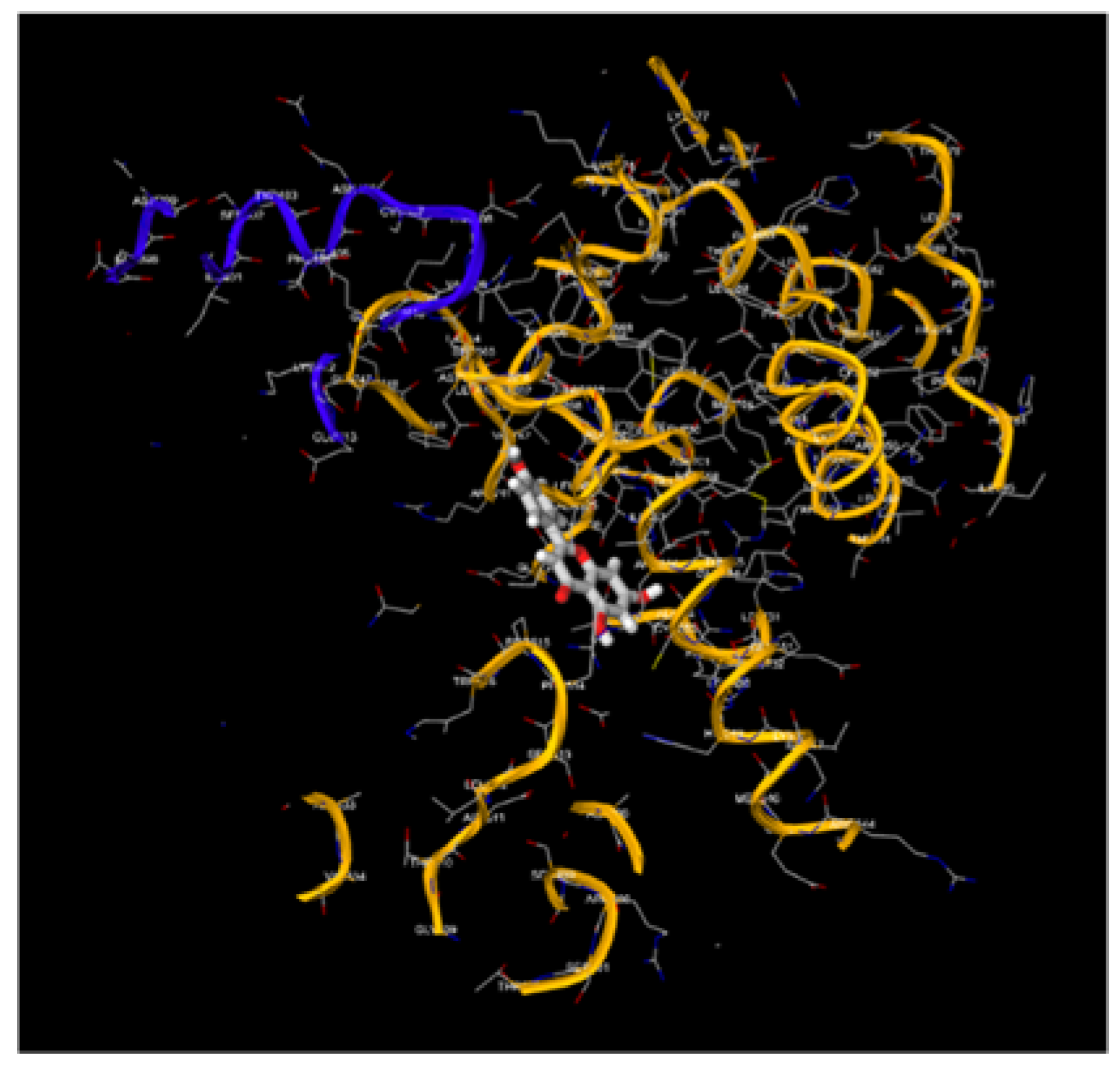

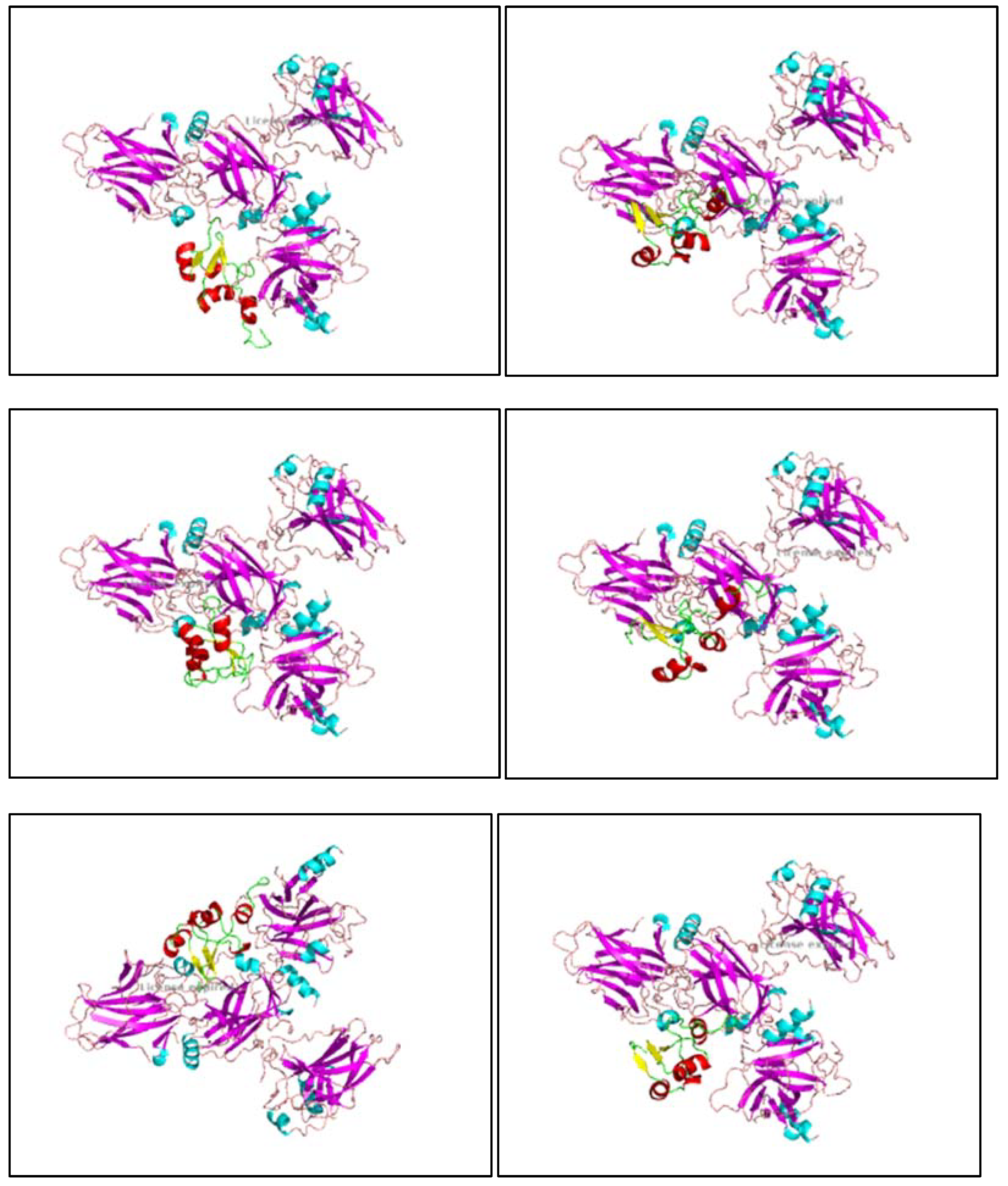

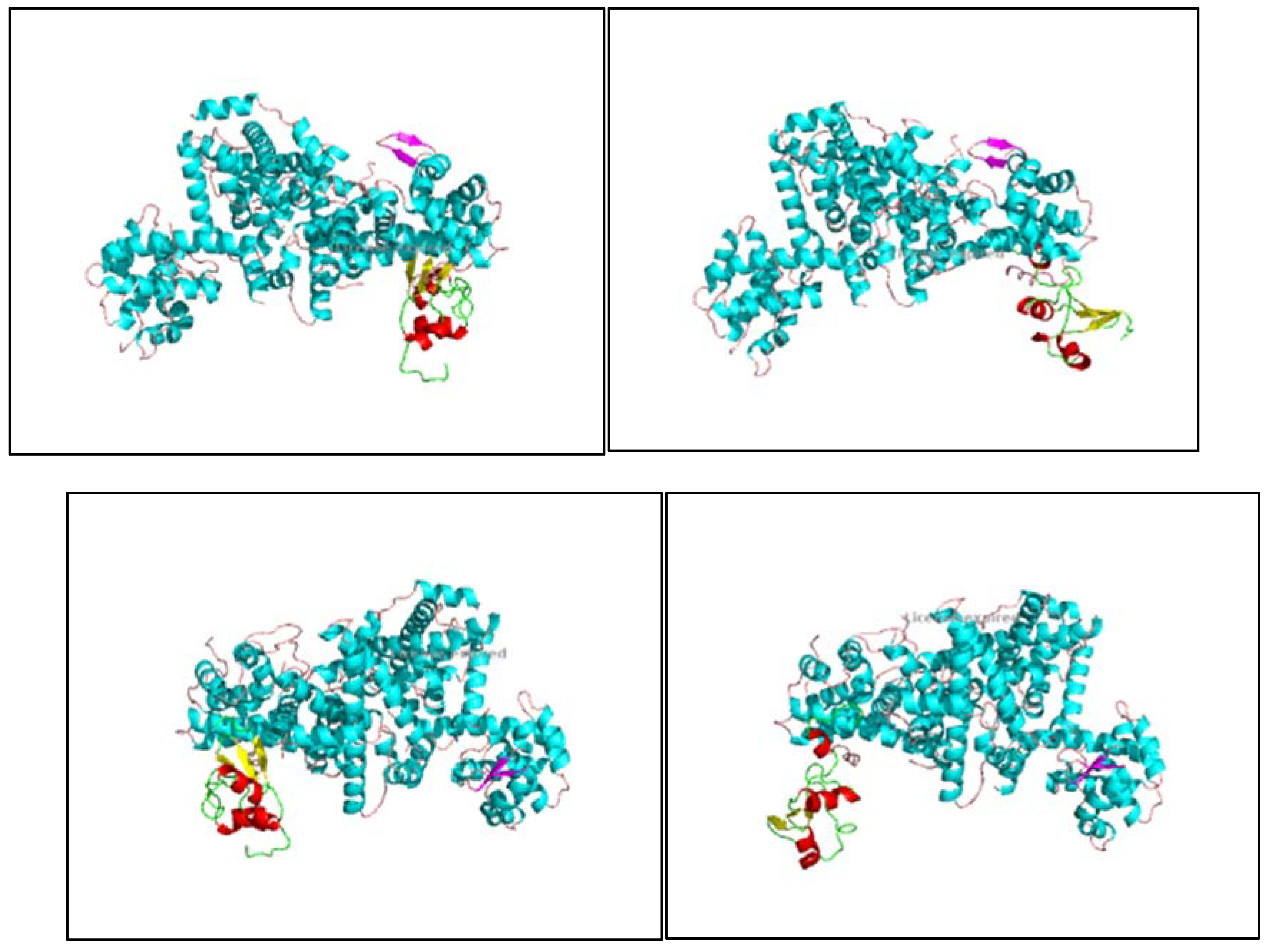

Figure 9.

1, 9.2, 9.3, 9.4, 9.5, 9.6, 9.7, 9.8: The images show the computerized reworking, of protein-protein interaction, in eight different interaction configurations, leading to the formation of eight different clusters, of the bond between the HPV-16 Oncoprotein E6 (shown in alpha helix structure, colored red and beta sheet, colored yellow), and the tumor suppressor TP-53 (shown in alpha helix structure, colored light blue and beta sheets, colored purple). These reworkings were performed with the help of the Clus Pro 2.0 software, using a supercomputer, to which we are connected by remote laptop terminal.

Figure 9.

1, 9.2, 9.3, 9.4, 9.5, 9.6, 9.7, 9.8: The images show the computerized reworking, of protein-protein interaction, in eight different interaction configurations, leading to the formation of eight different clusters, of the bond between the HPV-16 Oncoprotein E6 (shown in alpha helix structure, colored red and beta sheet, colored yellow), and the tumor suppressor TP-53 (shown in alpha helix structure, colored light blue and beta sheets, colored purple). These reworkings were performed with the help of the Clus Pro 2.0 software, using a supercomputer, to which we are connected by remote laptop terminal.

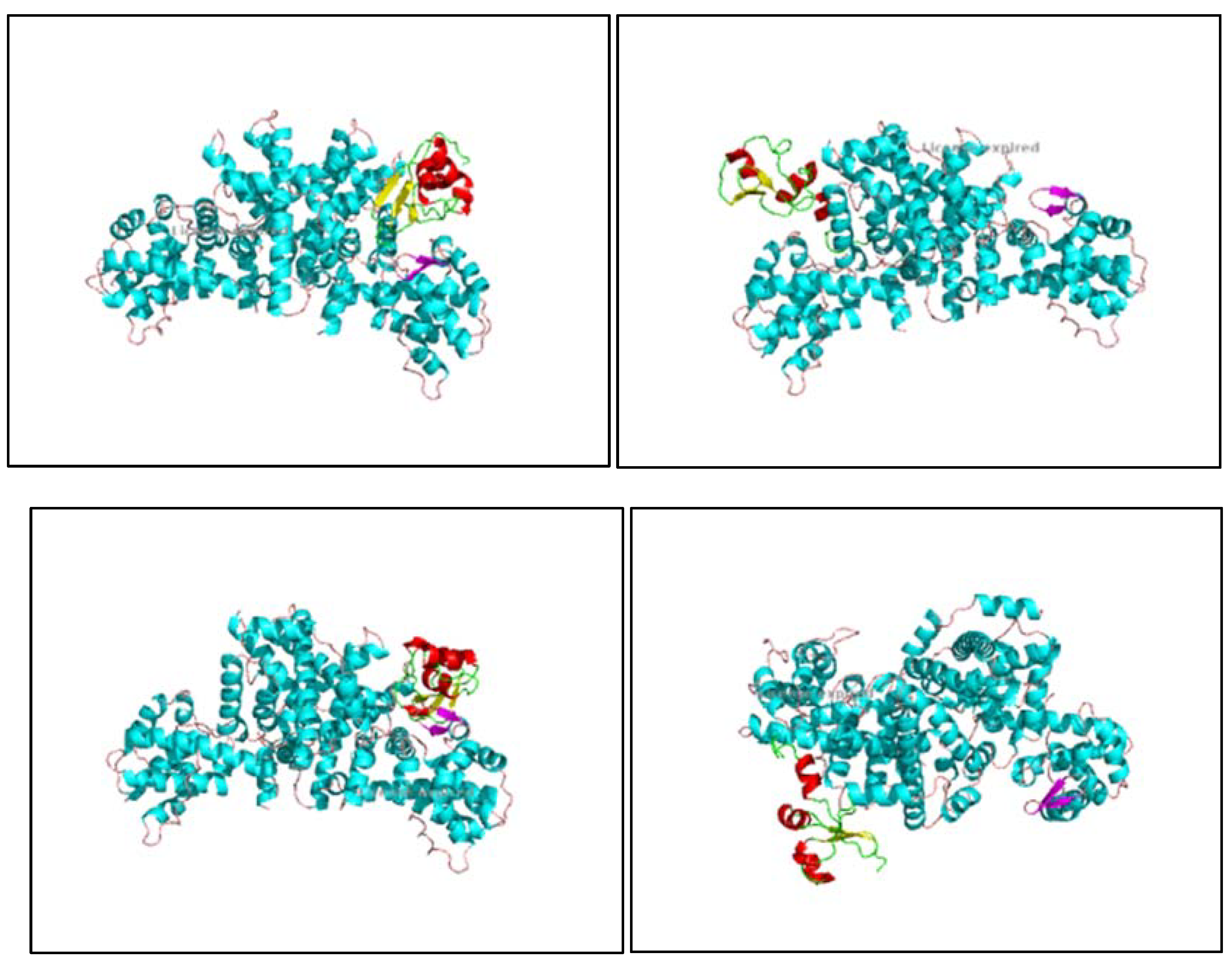

Figure 10.

1, 10.2, 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, 10.8: The images show the computerized reworking, of protein-protein interaction, in eight different interaction configurations, leading to the formation of eight different clusters, of the bond between the HPV-16 Oncoprotein E6 (shown in alpha helix structure, colored red and beta sheet, colored yellow), and the tumor suppressor pRb (shown in alpha helix structure, colored light blue and beta sheets, colored purple). These reworkings were performed with the help of the Clus Pro 2.0 software, using a supercomputer, to which we are connected by remote laptop terminal.

Figure 10.

1, 10.2, 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, 10.8: The images show the computerized reworking, of protein-protein interaction, in eight different interaction configurations, leading to the formation of eight different clusters, of the bond between the HPV-16 Oncoprotein E6 (shown in alpha helix structure, colored red and beta sheet, colored yellow), and the tumor suppressor pRb (shown in alpha helix structure, colored light blue and beta sheets, colored purple). These reworkings were performed with the help of the Clus Pro 2.0 software, using a supercomputer, to which we are connected by remote laptop terminal.

4. Discussion

The present study extensively analyzes the molecular docking interactions between the HPV-16 oncoprotein E6 and the tumor suppressor proteins TP-53 and pRb. Additionally, we evaluated the binding affinities of the natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin with TP-53 and pRb. To enable a comprehensive comparison, we converted the protein-protein interaction energies to a comparable scale for non-protein-protein interactions. This discussion centers on the comparative analysis of these docking results, highlighting the potential therapeutic implications of Apigenin and Luteolin.

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Docking Results

Protein-Protein Interactions: E6 with TP-53 and pRb

E6-TP-53 Interaction

Representative Energy: -688.9 kcal/mol (converted: -6.89 kcal/mol)

Lowest Energy: -976.7 kcal/mol (converted: -9.77 kcal/mol)

The interaction between E6 and TP-53 demonstrated strong binding affinities, with representative and lowest energy scores indicating robust and stable complexes. The converted scores highlight the significant strength of this interaction even when scaled to a non-protein context.

E6-pRb Interaction

Representative Energy: -722.2 kcal/mol (converted: -7.22 kcal/mol)

Lowest Energy: -729.6 kcal/mol (converted: -7.30 kcal/mol)

Similarly, the E6-pRb interaction revealed strong binding energies, with converted scores suggesting substantial interaction strength. The slightly lower converted values compared to the E6-TP-53 interaction may indicate a less stable yet still significant binding affinity.

Non-Protein-Protein Interactions: Apigenin and Luteolin with TP-53 and pRb

Apigenin and TP-53

Binding Energy: -6.9 kcal/mol

Luteolin and TP-53

Binding Energy: -6.9 kcal/mol

Apigenin and pRb

Binding Energy: -6.4 kcal/mol

Luteolin and pRb

Binding Energy: -6.4 kcal/mol

Apigenin and Luteolin both displayed notable binding affinities with TP-53 and pRb. The interaction energies, though lower than the converted values of the E6 protein-protein interactions, still demonstrate significant binding, particularly given that these are non-protein molecules interacting with proteins.

The converted protein-protein interaction energies indicate that E6 exhibits very strong binding affinities with both TP-53 and pRb. The natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin, while showing slightly lower binding energies, present affinities that are competitive within the non-protein-protein interaction context. Specifically, the binding energies of Apigenin and Luteolin with TP-53 (-6.9 kcal/mol) are quite comparable to the converted scores of E6-TP-53 (-6.89 to -9.77 kcal/mol). For pRb, the energies are slightly lower (-6.4 kcal/mol) compared to the converted E6-pRb interactions (-7.22 to -7.30 kcal/mol), yet still notable.

The negative binding energies observed for all interactions suggest that these interactions are thermodynamically favorable and spontaneous. The more negative the binding energy, the stronger and more stable the interaction. In this context, the protein-protein interactions (E6 with TP-53 and pRb) naturally exhibit more negative energies due to the extensive interaction interfaces and higher number of contact points. However, the non-protein interactions with Apigenin and Luteolin, despite being less complex, still demonstrate sufficient binding energy to suggest potential competitive inhibition of E6 binding.

The ability of Apigenin and Luteolin to bind TP-53 and pRb with significant affinity offers promising therapeutic potential. By competing with E6 for binding sites on these tumor suppressor proteins, Apigenin and Luteolin could theoretically prevent E6-mediated degradation of TP-53 and pRb. This preservation of TP-53 and pRb functions could restore their tumor suppressor activities, counteracting the oncogenic processes initiated by HPV-16. The slightly lower binding energies for Apigenin and Luteolin compared to E6 suggest that while these natural compounds may not entirely outcompete E6 in vivo, they could still significantly interfere with the binding process. This interference could lead to partial restoration of TP-53 and pRb functions, potentially slowing or preventing the progression of HPV-16-induced malignancies.

The comparative docking analysis between protein-protein and non-protein-protein interactions provides valuable insights into the binding dynamics of E6 with TP-53 and pRb, and the potential of Apigenin and Luteolin as therapeutic agents. Despite the inherent strength of protein-protein interactions, the significant binding affinities of Apigenin and Luteolin highlight their potential as natural inhibitors. Further research and experimental validation are required to fully explore these compounds' therapeutic efficacy and their possible role in HPV-16 treatment strategies.

5. Conclusions

This comprehensive study has elucidated the intricate molecular interactions between the HPV-16 oncoprotein E6 and the tumor suppressor proteins TP-53 and pRb, alongside the binding affinities of the natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin with these critical cellular targets. Through advanced molecular docking simulations, we have demonstrated that E6 exhibits exceptionally strong binding interactions with TP-53 and pRb, as evidenced by the highly negative binding energies. These interactions are pivotal in the viral oncogenic mechanism, as they disrupt the normal tumor suppressor functions of TP-53 and pRb, facilitating uncontrolled cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis. Notably, the natural compounds Apigenin and Luteolin displayed significant binding affinities with TP-53 and pRb, despite being non-protein molecules. The comparative analysis, facilitated by the conversion of protein-protein interaction energies to a comparable scale with non-protein interactions, revealed that these natural compounds can competitively bind to TP-53 and pRb. The binding energies of Apigenin and Luteolin, although slightly less negative than the converted values for E6 interactions, are sufficiently high to suggest potential therapeutic applications. By occupying the binding sites on TP-53 and pRb, Apigenin and Luteolin may hinder the binding of E6, thereby preserving the tumor suppressor functions of these proteins. These results has shown to us that we can improve immunity in a prevention of malignancies, through functional food, which we are developing.

Future Perspectives:

Given the promising binding affinities observed for Apigenin and Luteolin, future research should focus on several key areas to further explore and validate the therapeutic potential of these natural compounds against HPV-16-induced malignancies:

Experimental Validation: While the in silico docking results provide a strong foundation, experimental studies are crucial to confirm the binding interactions and biological efficacy of Apigenin and Luteolin. Techniques such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and co-immunoprecipitation should be employed to validate the binding affinities and elucidate the mechanisms by which these compounds inhibit E6 function.

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies: To optimize the efficacy of Apigenin and Luteolin, detailed SAR studies should be conducted. These studies can identify key structural features responsible for binding affinity and selectivity, enabling the design of more potent analogs with enhanced therapeutic properties.

In Vivo Studies and Pharmacokinetics: The pharmacokinetic properties, including bioavailability, metabolism, and tissue distribution of Apigenin and Luteolin, must be thoroughly investigated. In vivo studies using appropriate animal models will be essential to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and potential toxicity of these compounds in a physiological context.

Combination Therapy: Given the moderate binding affinities observed, combination therapies involving Apigenin, Luteolin, and other therapeutic agents could be explored. Such combinations may enhance the overall therapeutic outcome by simultaneously targeting multiple pathways involved in HPV-16 oncogenesis.

Clinical Trials and Therapeutic Development: Ultimately, the progression of Apigenin and Luteolin from the bench to bedside will require well-designed clinical trials. These trials should assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of these compounds in HPV-positive patients, providing critical data for their potential use in clinical settings.

In summary, this study lays the groundwork for the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting HPV-16 oncogenesis. The significant binding affinities of Apigenin and Luteolin with TP-53 and pRb highlight their potential as natural inhibitors of E6, offering a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention. Future research efforts should focus on translating these findings into clinical applications, with the ultimate goal of improving outcomes for patients affected by HPV-related malignancies.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Momir Dunjic and Stefano Turini; methodology, Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini; software, Stefano Turini; validation, Momir Dunjic and Stefano Turini; formal analysis; Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini, Marija Dunjic, Katarina Dunjic investigation; Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini, Lazar Nejkovic, Nenad Sulovic, Sasa Cvetkovic, Marija Dunjic, Katarina Dunjic, Dina Dolovac, resources; Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini, Sasa Cvetkovic, Lazar Nejkovic data curation; Stefano Turini, writing—original draft preparation; Stefano Turini writing—review and editing; Stefano Turini, Momir Dunjic visualization; Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini, Lazar Nejkovic, Nenad Sulovic, Sasa Cvetkovic, Marija Dunjic, Katarina Dunjic, Dina Dolovac, supervision; Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini project administration Momir Dunjic, Stefano Turini / All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding, but only funds from savings were used.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to our colleagues at Quince Medics Clinic in Belgrade, Republic of Serbia, for their exceptional contributions and support in the realization of this scientific work. Their expertise and dedication were invaluable in the execution of the research, even though they have not been included among the authors. Their collaborative efforts and commitment to excellence have significantly enriched this study, and we are deeply appreciative of their involvement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest that could have influenced the work reported in this study. All research activities, analyses, and findings were conducted impartially and without any external influences or competing interests. The authors affirm that there were no financial, personal, or professional conflicts before, during, or after the execution and completion of this scientific work.

References

- Lulu Yu, Vladimir Majerciak, Zhi-Ming Zheng. HPV16 and HPV18 Genome Structure, Expression, and Post-Transcriptional Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 29;23(9):4943. [CrossRef]

- Rahul Bhattacharjee, Sabya Sachi Das, Smruti Sudha Biswal, Arijit Nath, Debangshi Das, Asmita Basu, Sumira Malik, Lamha Kumar, Sulagna Kar, Sandeep Kumar Singh, Vijay Jagdish Upadhye, Danish Iqbal, Suliman Almojam, Shubhadeep Roychoudhury, Shreesh Ojha, Janne Ruokolainen, Niraj Kumar Jha, Kavindra Kumar Kesari. Mechanistic role of HPV-associated early proteins in cervical cancer: Molecular pathways and targeted therapeutic strategies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022 Jun:174:103675. Epub 2022 Apr 4. [CrossRef]

- Denise Martinez-Zapien, Francesc Xavier Ruiz, Juline Poirson, André Mitschler, Juan Ramirez, Anne Forster, Alexandra Cousido-Siah, Murielle Masson, Scott Vande Pol, Alberto Podjarny, Gilles Travé, Katia Zanier. Structure of the E6/E6AP/p53 complex required for HPV-mediated degradation of p53. Nature. 2016 Jan 28;529(7587):541-5. Epub 2016 Jan 20. [CrossRef]

- Julia D Toscano-Garibay, María L Benítez-Hess, Luis M Alvarez-Salas. Isolation and characterization of an RNA aptamer for the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Arch Med Res. 2011 Feb;42(2):88-96. [CrossRef]

- Marcela O Nogueira, Tomáš Hošek, Eduardo O Calçada, Francesca Castiglia, Paola Massimi, Lawrence Banks, Isabella C Felli, Roberta Pierattelli. Monitoring HPV-16 E7 phosphorylation events. Virology. 2017 Mar:503:70-75. Epub 2017 Jan 23. [CrossRef]

- Audrey J King, Jan A Sonsma, Henrike J Vriend, Marianne A B van der Sande, Mariet C Feltkamp, Hein J Boot, Marion P G Koopmans. Genetic Diversity in the Major Capsid L1 Protein of HPV-16 and HPV-18 in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2016 Apr 12;11(4):e0152782. eCollection 2016. [CrossRef]

- John Doorbar, Nagayasu Egawa, Heather Griffin, Christian Kranjec, Isao Murakami. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015 Mar;25 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):2-23. [CrossRef]

- Emma J Crosbie, Mark H Einstein, Silvia Franceschi, Henry C Kitchener. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2013 Sep 7;382(9895):889-99. Epub 2013 Apr 23. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian O Wendel, Avanelle Stoltz, Xuan Xu, Jazmine A Snow, Nicholas Wallace. HPV 16 E7 alters translesion synthesis signaling. Virol J. 2022 Oct 20;19(1):165. [CrossRef]

- Nicole Spardy, Anette Duensing, Elizabeth E Hoskins, Susanne I Wells, Stefan Duensing. HPV-16 E7 reveals a link between DNA replication stress, fanconi anemia D2 protein, and alternative lengthening of telomere-associated promyelocytic leukemia bodies. Cancer Res. 2008 Dec 1;68(23):9954-63. [CrossRef]

- Fern Baedyananda, Thanayod Sasivimolrattana, Arkom Chaiwongkot, Shankar Varadarajan, Parvapan Bhattarakosol. Role of HPV16 E1 in cervical carcinogenesis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Jul 28:12:955847. eCollection 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gypsyamber D'Souza, Aimee R Kreimer, Raphael Viscidi, Michael Pawlita, Carole Fakhry, Wayne M Koch, William H Westra, Maura L Gillison. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007 May 10;356(19):1944-56. [CrossRef]

- Luana Guimaraes de Sousa, Kimal Rajapakshe, Jaime Rodriguez Canales, Renee L Chin, Lei Feng, Qi Wang, Tomas Z Barrese, Erminia Massarelli, William William, Faye M Johnson, Renata Ferrarotto, Ignacio Wistuba, Cristian Coarfa, Jack Lee, Jing Wang, Cornelis J M Melief, Michael A Curran, Bonnie S Glisson. ISA101 and nivolumab for HPV-16+ cancer: updated clinical efficacy and immune correlates of response. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Feb;10(2):e004232. [CrossRef]

- Leo B Twiggs, Michael Hopkins. High-risk HPV DNA testing and HPV-16/18 genotyping: what is the clinical application? J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2011 Jul;15(3):224-30. [CrossRef]

- Wenbo Long, Zixi Yang, Xiabin Li, Ming Chen, Jie Liu, Yuanxue Zhang, Xingwang Sun. HPV-16, HPV-58, and HPV-33 are the most carcinogenic HPV genotypes in Southwestern China and their viral loads are associated with severity of premalignant lesions in the cervix. Virol J. 2018 May 25;15(1):94. [CrossRef]

- Tatiana Rabachini, Enrique Boccardo, Rubiana Andrade, Katia Regina Perez, Suely Nonogaki, Iolanda Midea Cuccovia, Luisa Lina Villa. HPV-16 E7 expression up-regulates phospholipase D activity and promotes rapamycin resistance in a pRB-dependent manner. BMC Cancer. 2018 Apr 27;18(1):485. [CrossRef]

- Molly A Feder, Shalini L Kulasingam, Nancy B Kiviat, Constance Mao, Erik J Nelson, Rachel L Winer, Hilary K Whitham, John Lin, Stephen E Hawes. Correlates of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and Association with HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA Detection in Young Women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Oct;28(10):1428-1435. Epub 2019 Jul 2. [CrossRef]

- Maria-Genalin Angelo, Sylvia Taylor, Frank Struyf, Fernanda Tavares Da Silva, Felix Arellano, Marie-Pierre David, Gary Dubin, Dominique Rosillon, Laurence Baril. Strategies for continuous evaluation of the benefit-risk profile of HPV-16/18-AS04-adjuvanted vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014 Nov;13(11):1297-306. Epub 2014 Sep 14. [CrossRef]

- Sarah S Chen, Barry S Block, Philip J Chan. Pentoxifylline attenuates HPV-16 associated necrosis in placental trophoblasts. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Mar;291(3):647-52. Epub 2014 Sep 17. [CrossRef]

- Jiahao Ye, Lin Li, Zhixi Hu. Exploring the Molecular Mechanism of Action of Yinchen Wuling Powder for the Treatment of Hyperlipidemia, Using Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Biomed Res Int. 2021 Oct 28:2021:9965906. eCollection 2021. [CrossRef]

- Amita Sahu, Goutam Ghosh, Goutam Rath. Identification and Molecular Docking Studies of Bioactive Principles from Alphonsea madraspatana Bedd. against Uropathogens. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2020;21(7):613-625. [CrossRef]

- Daniel Seeliger, Bert L de Groot. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2010 May;24(5):417-22. Epub 2010 Apr 17. [CrossRef]

- Yuyu Feng, Yumeng Yan, Jiahua He, Huanyu Tao, Qilong Wu, Sheng-You Huang. Docking and scoring for nucleic acid-ligand interactions: Principles and current status. Drug Discov Today. 2022 Mar;27(3):838-847. Epub 2021 Oct 27. [CrossRef]

- Shankaran Nehru Viji, Nagarajan Balaji, Namasivayam Gautham. Molecular docking studies of protein-nucleotide complexes using MOLSDOCK (mutually orthogonal Latin squares DOCK). J Mol Model. 2012 Aug;18(8):3705-22. Epub 2012 Mar 1. [CrossRef]

- S Y Yue. Distance-constrained molecular docking by simulated annealing. Protein Eng. 1990 Dec;4(2):177-84. [CrossRef]

- Richard M Jackson. Q-fit: a probabilistic method for docking molecular fragments by sampling low energy conformational space. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2002 Jan;16(1):43-57. [CrossRef]

- Tiancheng Li, Ranran Guo, Qida Zong, Guixia Ling. Application of molecular docking in elaborating molecular mechanisms and interactions of supramolecular cyclodextrin. Carbohydr Polym. 2022 Jan 15:276:118644. Epub 2021 Oct 23. [CrossRef]

- Jin Li, Ailing Fu, Le Zhang. An Overview of Scoring Functions Used for Protein-Ligand Interactions in Molecular Docking. Interdiscip Sci. 2019 Jun;11(2):320-328. Epub 2019 Mar 15. [CrossRef]

- Wojciech K Kasprzak, Bruce A Shapiro. Application of Molecular Dynamics to Expand Docking Program's Exploratory Capabilities and to Evaluate Its Predictions. Methods Mol Biol. 2023:2568:75-101. [CrossRef]

- Jerome Eberhardt, Diogo Santos-Martins, Andreas F Tillack, Stefano Forli. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 2021 Aug 23;61(8):3891-3898. Epub 2021 Jul 19. [CrossRef]

- Stefano Forli, Ruth Huey, Michael E Pique, Michel F Sanner, David S Goodsell, Arthur J Olson. Computational protein-ligand docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nat Protoc. 2016 May;11(5):905-19. Epub 2016 Apr 14. [CrossRef]

- Gabriela Bitencourt-Ferreira, Val Oliveira Pintro, Walter Filgueira de Azevedo Jr. Docking with AutoDock4. Methods Mol Biol. 2019:2053:125-148. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Dalgaty, Elisa Vianello, Barbara De Salvo, Jerome Casas. Insect-inspired neuromorphic computing. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2018 Dec:30:59-66. Epub 2018 Sep 21. [CrossRef]

- Barnali Das, Pralay Mitra. High-Performance Whole-Cell Simulation Exploiting Modular Cell Biology Principles. J Chem Inf Model. 2021 Mar 22;61(3):1481-1492. Epub 2021 Mar 8. [CrossRef]

- Shinya Goto, Darren K McGuire, Shinichi Goto. The Future Role of High-Performance Computing in Cardiovascular Medicine and Science -Impact of Multi-Dimensional Data Analysis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2022 May 1;29(5):559-562. Epub 2021 Oct 2. [CrossRef]

- Xun Jia, Peter Ziegenhein, Steve B Jiang. GPU-based high-performance computing for radiation therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2014 Feb 21;59(4):R151-82. Epub 2014 Feb 3. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Paul Courneya, Alexa Mayo. High-performance computing service for bioinformatics and data science. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018 Oct;106(4):494-495. Epub 2018 Oct 1. [CrossRef]

- Horacio Pérez-Sánchez, Sandra Gesing, Ivan Merelli. Editorial: High Performance Computing in Drug Discovery. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17(14):1578-1579. [CrossRef]

- Ivan Merelli, Horacio Pérez-Sánchez, Sandra Gesing, Daniele D'Agostino. High-performance computing and big data in omics-based medicine. Biomed Res Int. 2014:2014:825649. Epub 2014 Dec 22. [CrossRef]

- Tiziana Castrignanò, Silvia Gioiosa, Tiziano Flati, Mirko Cestari, Ernesto Picardi, Matteo Chiara, Maddalena Fratelli, Stefano Amente, Marco Cirilli, Marco Antonio Tangaro, Giovanni Chillemi, Graziano Pesole, Federico Zambelli. ELIXIR-IT HPC@CINECA: high performance computing resources for the bioinformatics community. BMC Bioinformatics. 2020 Aug 21;21(Suppl 10):352. [CrossRef]

- Rohan Gupta, Devesh Srivastava, Mehar Sahu, Swati Tiwari, Rashmi K Ambasta, Pravir Kumar. Artificial intelligence to deep learning: machine intelligence approach for drug discovery. Mol Divers. 2021 Aug;25(3):1315-1360. Epub 2021 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- Samer Ellahham. Artificial Intelligence: The Future for Diabetes Care. Am J Med. 2020 Aug;133(8):895-900. Epub 2020 Apr 20. [CrossRef]

- Yujie You, Xin Lai, Yi Pan, Huiru Zheng, Julio Vera, Suran Liu, Senyi Deng, Le Zhang. Artificial intelligence in cancer target identification and drug discovery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 May 10;7(1):156. [CrossRef]

- Mei Chen, Michel Decary. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: An essential guide for health leaders. Healthc Manage Forum. 2020 Jan;33(1):10-18. Epub 2019 Sep 24. [CrossRef]

- Bala Prabhakar, Rishi Kumar Singh, Khushwant S Yadav. Artificial intelligence (AI) impacting diagnosis of glaucoma and understanding the regulatory aspects of AI-based software as medical device. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2021 Jan:87:101818. Epub 2020 Nov 24. [CrossRef]

- Victoria Zinchenko, Sergey Chetverikov, Ekaterina Akhmad, Kirill Arzamasov, Anton Vladzymyrskyy, Anna Andreychenko, Sergey Morozov. Changes in software as a medical device based on artificial intelligence technologies. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2022 Oct;17(10):1969-1977. Epub 2022 Jun 13. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo Cupertino Bernardes, Maria Augusta Pereira Lima, Raul Narciso Carvalho Guedes, Clíssia Barboza da Silva, Gustavo Ferreira Martins. Ethoflow: Computer Vision and Artificial Intelligence-Based Software for Automatic Behavior Analysis. Sensors (Basel). 2021 May 7;21(9):3237. [CrossRef]

- Glenn J Fernandes, Arthur Choi, Jacob Michael Schauer, Angela F Pfammatter, Bonnie J Spring, Adnan Darwiche, Nabil I Alshurafa. An Explainable Artificial Intelligence Software Tool for Weight Management Experts (PRIMO): Mixed Methods Study. J Med Internet Res. 2023 Sep 6:25:e42047. [CrossRef]

- Aditya Kate, Ekkita Seth, Ananya Singh, Chandrashekhar Mahadeo Chakole, Meenakshi Kanwar Chauhan, Ravi Kant Singh, Shrirang Maddalwar, Mohit Mishra. Artificial Intelligence for Computer-Aided Drug Discovery. Drug Res (Stuttg). 2023 Sep;73(7):369-377. Epub 2023 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- Lukas A W Gemein, Robin T Schirrmeister, Patryk Chrabąszcz, Daniel Wilson, Joschka Boedecker, Andreas Schulze-Bonhage, Frank Hutter, Tonio Ball. Machine-learning-based diagnostics of EEG pathology. Neuroimage. 2020 Oct 15:220:117021. Epub 2020 Jun 10. [CrossRef]

- Raphael Reher, Hyun Woo Kim, Chen Zhang, Huanru Henry Mao, Mingxun Wang, Louis-Félix Nothias, Andres Mauricio Caraballo-Rodriguez, Evgenia Glukhov, Bahar Teke, Tiago Leao, Kelsey L Alexander, Brendan M Duggan, Ezra L Van Everbroeck, Pieter C Dorrestein, Garrison W Cottrell, William H Gerwick. A Convolutional Neural Network-Based Approach for the Rapid Annotation of Molecularly Diverse Natural Products. J Am Chem Soc. 2020 Mar 4;142(9):4114-4120. Epub 2020 Feb 21. [CrossRef]

- Houri Hintiryan, Hong-Wei Dong. Brain Networks of Connectionally Unique Basolateral Amygdala Cell Types. Neurosci Insights. 2022 Feb 26:17:26331055221080175. eCollection 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xiyue Wang, Sen Yang, Ming Tang, Heng Yin, Hua Huang, Ling He. HypernasalityNet: Deep recurrent neural network for automatic hypernasality detection. Int J Med Inform. 2019 Sep:129:1-12. Epub 2019 May 23. [CrossRef]

- Jinge Wang, Zien Cheng, Qiuming Yao, Li Liu, Dong Xu, Gangqing Hu. Bioinformatics and biomedical informatics with ChatGPT: Year one review. Quantitative Biology. 2024;1–15. [CrossRef]

- Jinge Wang, Qing Ye, Li Liu, Nancy Lan Guo, Gangqing Hu. Bioinformatics Illustrations Decoded by ChatGPT: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. bioRxiv preprint. this version posted October 17, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shreya Bhardwaj, Yasha Hasija. ChatGPT, a powerful language model and its potential uses in bioinformatics. IEEE Xplore: 23 November 2023. [CrossRef]