1. Introduction

There exists a close analogy between the mechanism at the heart of the mass generation for scalar and vector bosons in the Standard Model [

1,

2] and the mechanism responsible for superconductivity [

3,

4]. In both cases, the spontaneous breaking of a continuous symmetry comes along with the emergence of new elementary excitations. In the context of superconductors they are identified with the collective fluctuations of the macroscopic (complex) order parameter. These comprise the massless phase fluctuations, which in a charged superconductor are pushed to the plasma frequency via the Anderson-Higgs mechanism [

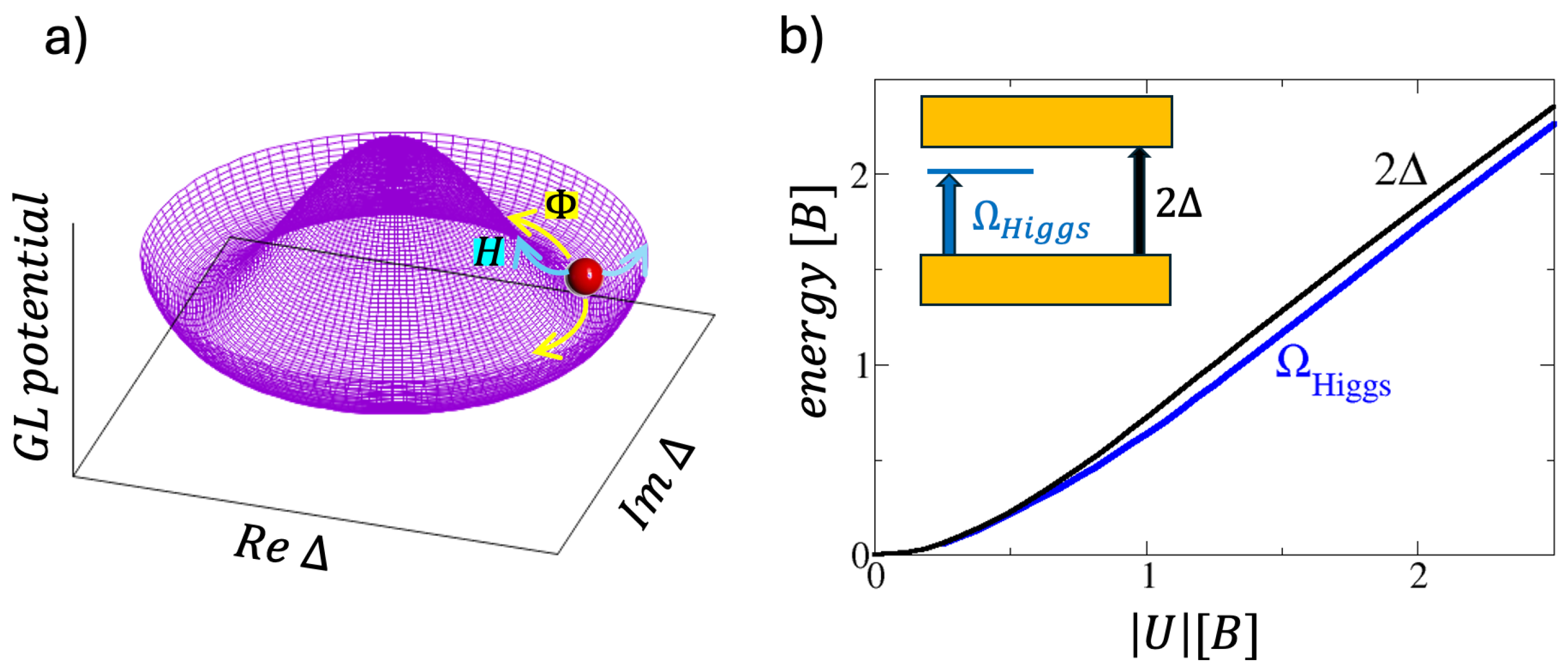

5]. Moreover, amplitude fluctuations represent the analogous to the Higgs field in the Standard Model and therefore are also labeled as ’Higgs’ modes in a superconducting system, cf.

Figure 1a. In conventional (weakly-coupled or BCS) superconductors the energy of the Higgs mode coincides with the spectral gap

for single-particle excitations which influence on its dynamics, leading to a non-relativistic strongly overdamped mode. In addition, its effects can be hardly probed experimentally, unless one strongly perturbs the system out of equilibrium [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In a recent paper [

13] we have shown that in the limit of strong coupling the Higgs mode is shifted inside the spectral gap which leads to undamped Higgs oscillations, cf.

Figure 1b. Such a situation could be realized in cold atomic Fermion condensates and in fact, a well-defined collective mode throughout the entire crossover from BCS to Bose-Einstein condensation has been observed recently [

14] in a system with weak modulation of the confinement. Our previous work was based on the time-dependent Gutzwiller approximation (TDGA) [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] which allows for the investigation of dynamical properties of systems with a strong local interaction

U (i.e. Hubbard-type models). By evaluating both the spectral gap

and the energy of the Higgs mode it could be shown that both quantities start to separate when the magnitude of the local attraction

becomes larger than the bandwidth. However, within this numerical approach, it is difficult to analyze the situation at weak coupling. In particular, it is hard to distinguish between the situation where a critical coupling has to be exceeded for the Higgs mode to be pushed inside the spectral gap or a scenario where at weak coupling the difference between Higgs mode energy and

becomes exponentially small.

Here we analyze analytically the situation in the weak-coupling limit of the TDGA and show that the latter scenario is realized in this case.

Section 2 introduces the model and first discusses the appearance of amplitude modes within the standard BCS+RPA approach. The analysis of the Higgs excitation within the TDGA is then performed in

Section 4 in the weak coupling limit and we finally conclude our discussion in

Section 5.

2. Model and BCS Approximation

We exemplify the evaluation of amplitude modes within the single-band attractive Hubbard hamiltonian

where in the following we denote the Fourier transform of

as the dispersion

.

Decoupling in the pair channel yields the usual BCS Hamiltonian

with

,

and

N denotes the number of lattice sites.

Eq. (

2) can be diagonalized with the Bogoljubov transformation

and one obtains

where

,

, and

. The self-consistency condition (zero temperature) reads

3. Collective Modes Beyond Weak-Coupling BCS Theory

The mean-field decoupling neglects the following fluctuation contributions in the pairing channel

with

and we have defined

and

.

In the same way the the fluctuation contribution in the charge channel is obtained as

with

3.1. Correlation Functions and RPA Resummation

We denote correlation functions by

where in the following

,

correspond to either pair or charge fluctuations Eqs. (

8,9,

11).

It is convenient to define the

matrices

where the superscript ’0’ indicates that the elements are computed with the bare BCS wave function and are given in the appendix.

The correlations of the interacting system are then defined by an analogous matrix

but without superscript. From Eqs. (

7,

10) the matrix for the local interaction is given by

The RPA resummation can then be written as

which is solved by

3.2. Amplitude and Phase Correlations

Introducing amplitude

and phase operators

the amplitude and phase correlation functions are obtained from

and analogously for the mixed correlations between amplitude, phase, and charge.

The susceptibility and interaction matrices can now be transformed to the amplitude-phase representation by introducing the matrix

so that

and the RPA equation Eq. (

14) also holds in the transformed representation. Therefore the interaction in the amplitude channel is attractive whereas it is repulsive in the phase channel.

3.3. The Ph-Symmetric Case in the Limit

In the case of particle-hole symmetry and for

(where

,

) one finds a decoupling of amplitude from phase and charge fluctuations, i.e.

As a consequence, the amplitude correlations decouple from the phase-charge sector in the RPA equation Eq. (

14), and one finds

and from Eq. (

15) together with the bare correlation functions listed in the appendix one obtains

Noting that

it becomes apparent that the ’pole’ of Eq. (

23) is given by

because this is identical to the self-consistency equation Eq. (

6).

Therefore the energy of the amplitude mode at is given by and coincides with the onset of quasiparticle excitations. Thus it is not a pole but rather a branch cut in the amplitude correlation function.

Note also that a similar result appears in the case of the repulsive Hubbard model where the amplitude excitations of the SDW order parameter appear at the energy of the SDW gap as has been shown in Ref. [

24].

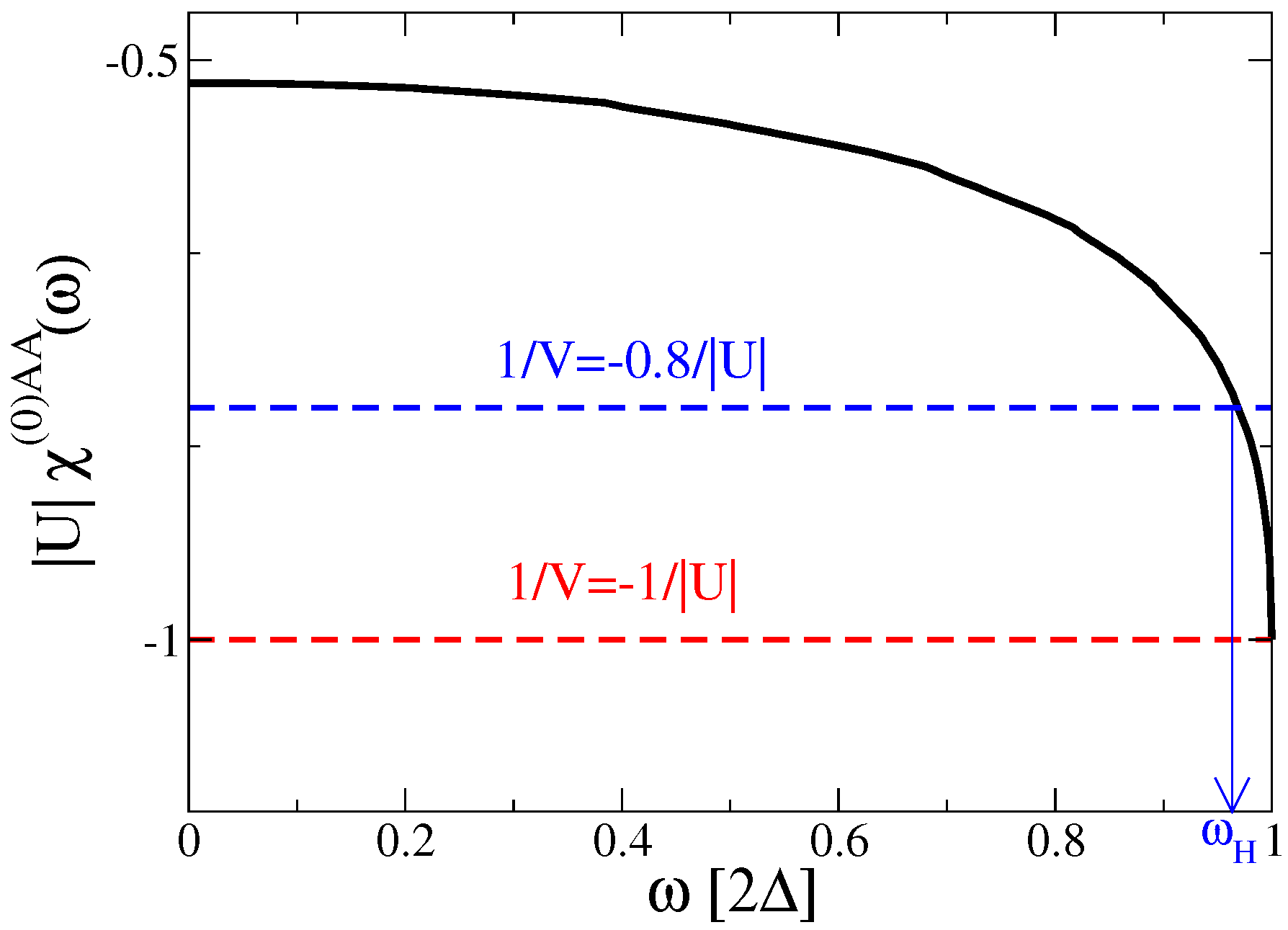

Figure 2 visualizes the condition to find the Higgs pole in Eq. (

23) for a two-dimensional system. As a function of

the (negative) bare amplitude correlation function Eq. (

25) is a continuously decreasing function which at

reaches the value

which leads to the Higgs pole exactly at

. This can change if we hypothesize an interaction between quastiparticles

V different from the static interaction

U that appears in the BCS equation. In case

V would be more negative than

U (blue dashed line in

Figure 2), the pole of Eq. (

23) would occur at

and therefore would correspond to a bound state inside the spectral gap. We will show in the following section that this is exactly the situation that is realized within the TDGA because in this variational scheme the denominator of Eq. (

23) is not related to the self-consistency condition for the spectral gap when

. This can understood as vertex corrections in the effective interaction between quasiparticles in the same spirit as Ref. [

25].

4. TDGA

The TDGA ground state is obtained by optimizing the number of doubly occupied sites in the underlying BCS state

by applying the ’Gutzwiller projector’

, i.e.

The variational energy

depends on the double occupancy

D and the anomalous correlations

, cf. e.g. [

26]. A first step in the application of the TDGA is the evaluation of the so-called Gutzwiller hamiltonian, defined as the derivative of

with respect to the density matrix [

15,

16]. One obtains (for the homogeneous system,

N lattice sites) [

26]

where now the quasiparticle energy in

is renormalized by

and

is related to the density

n via

. In contrast to weak-coupling BCS theory, where the spectral gap parameter is given by

, in the TDGA this quantity is obtained from the variational principle as

On the other hand, the equation for the anomalous correlations still resembles the corresponding BCS result and reads

4.1. Ground State for the Half-Filled Case

Similar to the BCS case we focus in the following on the half-filled system where analytical results can be obtained in the weak-coupling limit. The renormalization factor simplifies to

and expanding Eq. (

30) for small

(weak coupling) yields

Furthermore, for the half-filled system we can write

and obtain in lowest order in

,

We proceed by evaluating Eqs. (

28,

29) for a constant DOS,

for

. For Eq. (

29) we obtain

and in the last line, we used the limit of weak coupling.

In the same limit the anomalous correlations Eq. (

28) are obtained as

Inserting Eq. (

34) into Eq. (

33) finally yields

where it should be noted that

with

being the bare bandwidth. The dependence of

and

on

U is encoded in the dependence on

d with

,

when

.

We are now in the position to evaluate the total Gutzwiller approximated energy

and the minimization

leads to the equation

Contribution ’1’ determines the double occupancy in the absence of SC, i.e.

.

On the other hand, it can be seen from

Figure 3 that for small

d the contributions ’

’ in Eq. (

37) are exponentially small, so that by setting

the leading correction for small

is given by

i.e. the double occupancy decreases with the onset of SC order.

4.2. TDGA for the SC Half-Filled Case

Within the TDGA and employing the weak-coupling limit the effective interaction in the amplitude channel can be evaluated by expanding the renormalized kinetic energy (per site)

in terms of the fluctuations

and

.

In the spirit of the anti-adiabaticity principle [

15] we eliminate the high-energy double occupancy fluctuations from Eq. (

40) using the condition

which yields

. The resulting interaction in the amplitude channel alone (note that

, cf.

Section 3.2) is given by

with

or when we use

From Eqs. (

35,

38) it turns out that in the considered limit (half-filling, weak coupling) the TDGA provides an exponentially small correction to the bare interaction

.

We proceed by investigating the consequences for the resulting Higgs mode within the TDGA. Similar to the BCS+RPA case the amplitude mode occurs as a pole in Eq. (

23),

with

where now

contains the renormalization of

by the GA factors

.

Comparison of Eq. (

26) and Eq. (

28) reveals that the Higgs mode would occur at

when the effective interaction would be given by

. From Eq. (

33) one finds

or when we make use of

Thus

i.e.

is more negative than

in the small coupling limit so that according to the analysis related to

Figure 2 one obtains the pole for the Higgs mode below the spectral gap

.

Expanding the amplitude correlation function Eq. (

43) around the spectral gap

yields the pole from the resonance condition

at

i.e. the shift of the Higgs mode inside the spectral gap is exponentially small in weak coupling.

5. Conclusions

We have shown, that the TDGA applied to the weak coupling limit of the attractive Hubbard model leads to amplitude (’Higgs’) modes which are split-off from the quasiparticle continuum at

but the corresponding binding energy is exponentially small in the attractive interaction. This is different from the BCS+RPA approach where the ’Higgs’ excitation always appears at

and therefore is damped due to the interference with quasiparticle excitations. When the interaction becomes comparable with the bandwidth the Higgs binding energy becomes sizeable [

13] and thus long-lived amplitude modes could be observed in the crossover regime from BCS to BEC. In fact, recent investigations on cold atomic fermion condensates [

14] confirm this picture although in this experiment also the modulation of the confinement seems to play a role. Our theory also goes beyond the applicability to superconductors and should also have relevance in magnetic systems where the collective modes comprise the amplitude excitation of the magnetic order. In fact, in Ref. [

13] we have proposed an experimental setup where the predicted bound state of the antiferromagnetic amplitude mode in undoped cuprates may be observed via magneto-optical methods. Of course, the main difference between superconducting and magnetic systems is the absence of low-lying excitations in the former due to the Anderson-Higgs mechanism which pushes the Bogoljubov-Goldstone mode to the plasma energy. On the other hand, in a magnetic system, the decay channel of the amplitude mode into low-lying magnon excitations persists. In this regard, it is interesting that strong correlations can also stabilize quantum matter [

27] so that the proposed split-off magnetic amplitude modes may have a lifetime long enough to be detected via a frequency-dependent Faraday rotated optical signal [

13].

Funding

J.L. acknowledges support from MUR, Italian Ministry for University and Research through PRIN Project No. 20207ZXT4Z. The work of G.S. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft under SE806/20-1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lara Benfatto, Claudio Castellani, Mattia Udina, Paolo Barone, O.P. Sushkov and Dirk Manske for useful discussions.

Appendix A. BCS Correlation Functions

The correlation functions in the non-interacting BCS limit read

References

- S. Weinberg. The Quantum Theory of Fields – Vol. 2: Modern Applications. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- P. W. Higgs. Broken symmetries, massless particles and gauge fields. Phys. Lett. 1964, 12 132-133. [CrossRef]

- N. Nagaosa. Quantum Field Theory in Condensed Matter Physics. Springer, 1999.

- D. Pekker; C. M. Varma. Amplitude/Higgs Modes in Condensed Matter Physics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2015, 6, 269-297. [CrossRef]

- P. W. Anderson. Coherent Excited States in the Theory of Superconductivity: Gauge Invariance and the Meissner Effect. Phys. Rev. 1958, 110, 827-835. [CrossRef]

- T. Papenkort; V. M. Axt; T. Kuhn. Coherent dynamics and pump-probe spectra of BCS superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 224522. [CrossRef]

- Ryusuke Matsunaga; Yuki I. Hamada; Kazumasa Makise; Yoshinori Uzawa; Hirotaka Terai; Zhen Wang; Ryo Shimano. Higgs Amplitude Mode in the BCS Superconductors Nb1-xTixN Induced by Terahertz Pulse Excitation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 057002.

- Ryusuke Matsunaga; Naoto Tsuji; Hiroyuki Fujita; Arata Sugioka; Kazumasa Makise; Yoshinori Uzawa; Hirotaka Terai; Zhen Wang; Hideo Aoki; Ryo Shimano; Light-induced collective pseudospin precession resonating with Higgs mode in a superconductor, Science 2014, 345, 1145-1149. [CrossRef]

- B. Mansart; J. Lorenzana; A. Mann; A. Odeh; M. Scarongella; M. Chergui; F. Carbone. Coupling of a high-energy excitation to superconducting quasiparticles in a cuprate from coherent charge fluctuation spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 4539-4544. [CrossRef]

- H. Krull; N. Bittner; G. S. Uhrig; D. Manske; A. P. Schnyder. Coupling of Higgs and Leggett modes in non-equilibrium superconductors. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 11921. [CrossRef]

- R. Shimano; N. Tsuji. Higgs Mode in Superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2020, 11, 103-124. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Kemper; M. A. Sentef; B. Moritz; J. K. Freericks; T. P. Devereaux. Direct observation of Higgs mode oscillations in the pump-probe photoemission spectra of electron-phonon mediated superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 224517. [CrossRef]

- J. Lorenzana; G. Seibold. Long-Lived Higgs Modes in Strongly Correlated Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 026501. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Cabrera; R. Henke; L. Broers; J. Skulte; H. P. Ojeda Collado; H. Biss; L. Mathey; H. Moritz. Effect of strong confinement on the order parameter dynamics in fermionic superfluids. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12645.

- G. Seibold; J. Lorenzana. Time-Dependent Gutzwiller Approximation for the Hubbard Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 2605. [CrossRef]

- G. Seibold; F. Becca; J. Lorenzana. Inhomogeneous Gutzwiller approximation with random phase fluctuations for the Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 085108. [CrossRef]

- G. Seibold; F. Becca; P. Rubin; J. Lorenzana. Time-dependent Gutzwiller theory of magnetic excitations in the Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 155113. [CrossRef]

- G. Seibold; F. Becca; J. Lorenzana. Theory of Antibound States in Partially Filled Narrow Band Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 016405. [CrossRef]

- G. Seibold; F. Becca; J. Lorenzana. Time-dependent Gutzwiller theory of pairing fluctuations in the Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 045114. [CrossRef]

- S. Ugenti; M. Cini; G. Seibold; J. Lorenzana; E. Perfetto; G. Stefanucci. Particle-particle response function as a probe for electronic correlations in the p-d Hubbard model, Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 075137. [CrossRef]

- M. Schiró; M. Fabrizio. Time-Dependent Mean Field Theory for Quench Dynamics in Correlated Electron Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 076401. [CrossRef]

- M. Schiró; M. Fabrizio. Quantum quenches in the Hubbard model: Time-dependent mean-field theory and the role of quantum fluctuations. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 165105. [CrossRef]

- J Bünemann; M. Capone; J. Lorenzana; G. Seibold. Linear-response dynamics from the time-dependent Gutzwiller approximation. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 053050. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Schrieffer; X. G. Wen; S.C. Zhang. Dynamic spin fluctuations and the bag mechanism of high-Tc superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 16, 11663. [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Vilk; A. M. S. Tremblay. Non-perturbative many-body approach to the Hubbard model and single-particle pseudogap. Journal de Physique I 1997, 7, 1309-1368.

- G. Seibold; J. Lorenzana. Nonequilibrium dynamics from BCS to the bosonic limit. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 144502. [CrossRef]

- R. Verresen; R. Moessner; F. Pollmann. Avoided quasiparticle decay from strong quantum interactions. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 750-753. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).