Introduction

The experimental investigation on which the current exposition is based has been previously reported [

1]. The data and calculated properties are reproduced in

Appendix A. This earlier work identifies the emergence of spontaneous diamagnetism and paramagnetism in the behaviour of nanoscale clathrate hydrate structures (or water ice cages) as critical phenomena responsible for work output in a kinetic system. The accompanying analysis centres upon a superconducting phase transition where the scaling laws reveal the emergence of a critical correlation length

ξ (3.05 m). It is shown [

1] that relativistic length expansion and time contraction on a Lorentz manifold describe the critical correlation length

ξ (calculation reproduced in

Appendix B). The Ginzburg-Landau parameter

κ (0.65 ≤

κ ≤ 0.707), as defined in

Appendix C, is also uncovered together with topological ordering. Additionally, it is noted that the Ginzburg-Landau theory of superconductors invokes gauge-invariant coupling of a scalar field

Φ to the Yang-Mills action in QCD. These relativistic and quantum aspects of the findings are examined here in further detail within the context of the Berry geometrical phase, complex energy band gaps and the QCD mass gap.

Situations can arise in thermodynamics whereby a physical system is prevented from attaining its lowest energy and highest entropy state through the existence of an energy barrier. False vacuum conditions can result from such metastability in the extreme so that on short timescales a positive, non-minimum energy density cannot be raised or lowered in response to external interactions. Where an energy barrier is maintained through dynamic inhomogeneities, a system can be isolated from external interactions through local stability conditions, as characterized by a non-concave entropy function [

2]. The process of thermodynamic isolation is also described by the characteristic of asymptotic freedom in particle physics [

3]. Opposition to dynamical change is established through complex reorganization of individual system components, e.g. degenerate hydrogen bonding in dissipative condensed matter systems [

1]; gluon splitting and recombining in the case of colour confinement; and gluon exchange in quark confinement [

3,

4]. The experimental results reported in [

1] reveal that water ice cages under negative pressure can give rise to false vacuum behaviour, as revealed through an excess negative energy potential

ue. These conditions are held responsible for the emergence of non-additive and non-extensive energy contributions within the system.

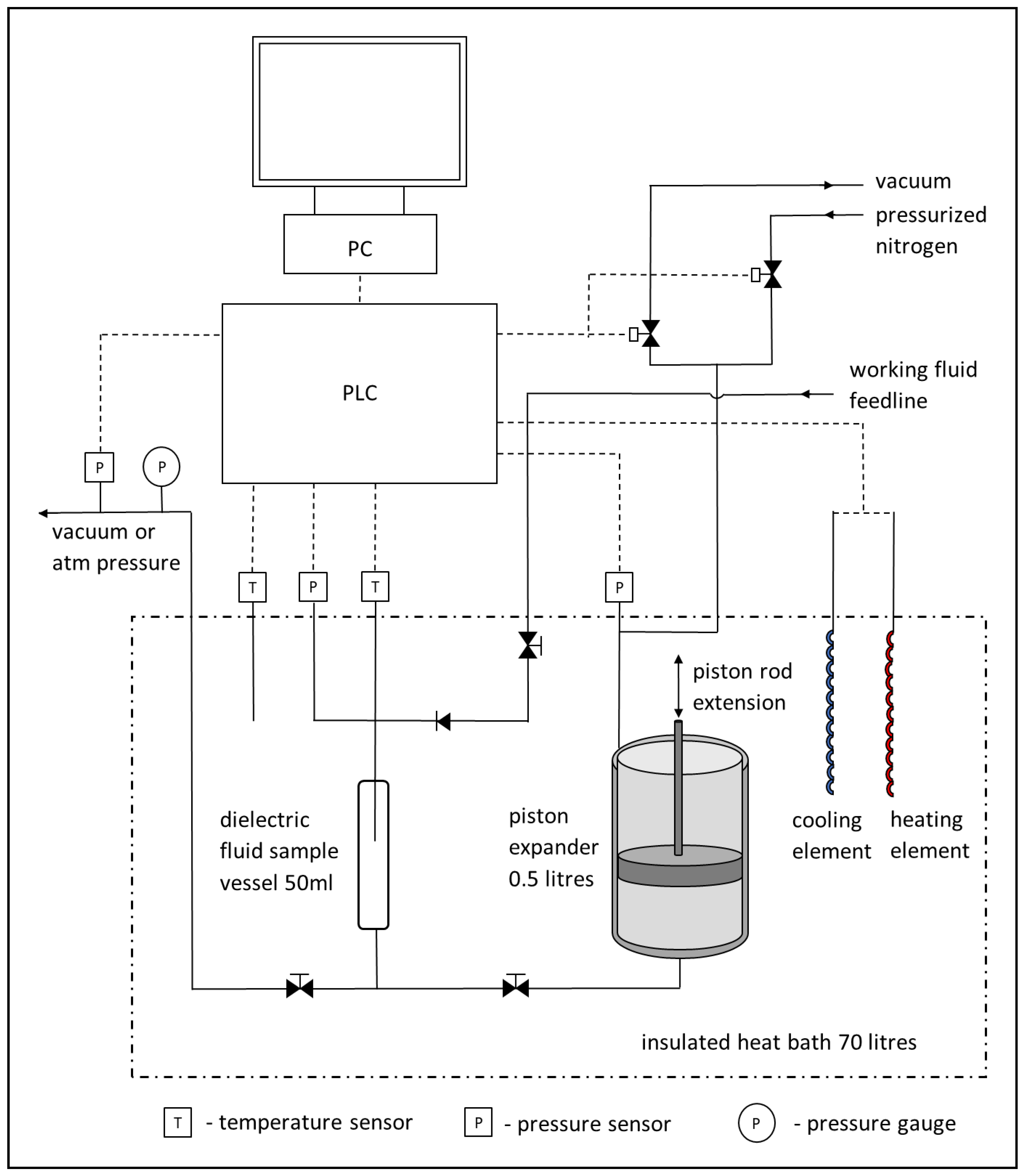

The low-energy system reported encompasses both a crystal-fluid material and its embedding vacuum manifold whereby hyperbolic curvature K (- 0.46 ≤ K ≤ - 0.22 m2s-2) and variable volume V (0.005 ≤ V ≤ 0.5 litre), rather than any fluid mechanical response, are responsible for the work performed by the system. The chemical and physical properties associated with water ice cage structures are also shown to elicit magnetic phenomena that induce the Berry phase and associated dual superconductivity whilst the material maintains almost constant density. The geometric phase emerges out of a cyclic evolution of the system Hamiltonian where the state returns to its origin but gains an additional phase factor.

The crystal-fluid is composed of dissipative, reorganizing, water ice cage structures suspended within a polar dielectric inhibitor solvent. The formulation results in false vacuum behaviour [

5] such that the material part of the system is effectively isolated from any external thermodynamic interactions. However, despite the presence of strong local stability conditions, it is possible to perturb the system through external pressure interaction to induce a ‘rolling’ critical response [

6]. This critical state represents a large-scale correlation in magnetic charge driven by a symmetry-related energy gain, i.e. from the exposure of an additional energy source within the system.

Hyperbolic Gaussian curvature K originates in the negative potential of the false vacuum established by the highly degenerate system. The Gaussian radius of hyperbolic curvature Rg of the crystal-fluid is a direct consequence of the embedding manifold geometry. For the crystal-fluid, conservation of angular momentum requires that a reducing effective radius results from an acceleration whilst an increasing effective radius results from a deceleration, i.e. variability in the material inertia is evident. Quantum interactions leading to non-additivity can be identified in both instances. The associated changes in swept volume dV arising from the condensation of magnetic entities are non-extensive.

During the ‘rolling’ critical response, the magnetic and superconducting behaviours are quantified by a distinctive universality class of critical exponents [

1]. Formation of a magnetic condensate induces a phase transition from Type-II superconductivity to a dual of Type-I superconductivity where the spontaneous magnetic field H

s, as an ‘auxiliary’ order parameter, reduces to zero [

7]. Following this, ordering is attributed to an emergent complex parameter field, similar to the topological ordering of spin ices as described by Castelnovo et al. [

8].

A definitive theory of quark confinement remains elusive despite experimental and lattice gauge theory/ computer simulation successes. The QCD large lattice technique is based upon strong coupling conditions so that perturbative techniques are deemed impractical. From a mathematical perspective, the confinement problem is known as the mass gap problem. A promising solution originally proposed by ‘t Hooft [

9] and Mandelstam [

10] claims that the ground-state of QCD is a dual superconductor in which quarks are confined by chromoelectric vortices. These vortices are analogous to the Abrikosov vortices seen in Type-II superconductors. In the current exposition these QCD descriptions are also relevant to the macro-scale Type-I dual superconductor uncovered.

In a dual superconductor, the roles of the electric and magnetic fields are exchanged so that in this case the electric field is excluded. The significance of dual superconductivity in furthering an understanding of the strong interaction is examined in comprehensive reviews by Ripka [

11] and Kondo et al. [

12]. The superconducting phase transition established is consistent with Ginzburg-Landau theory suggesting gauge-invariant coupling of a scalar field

Φ to the Yang-Mills action in QCD [

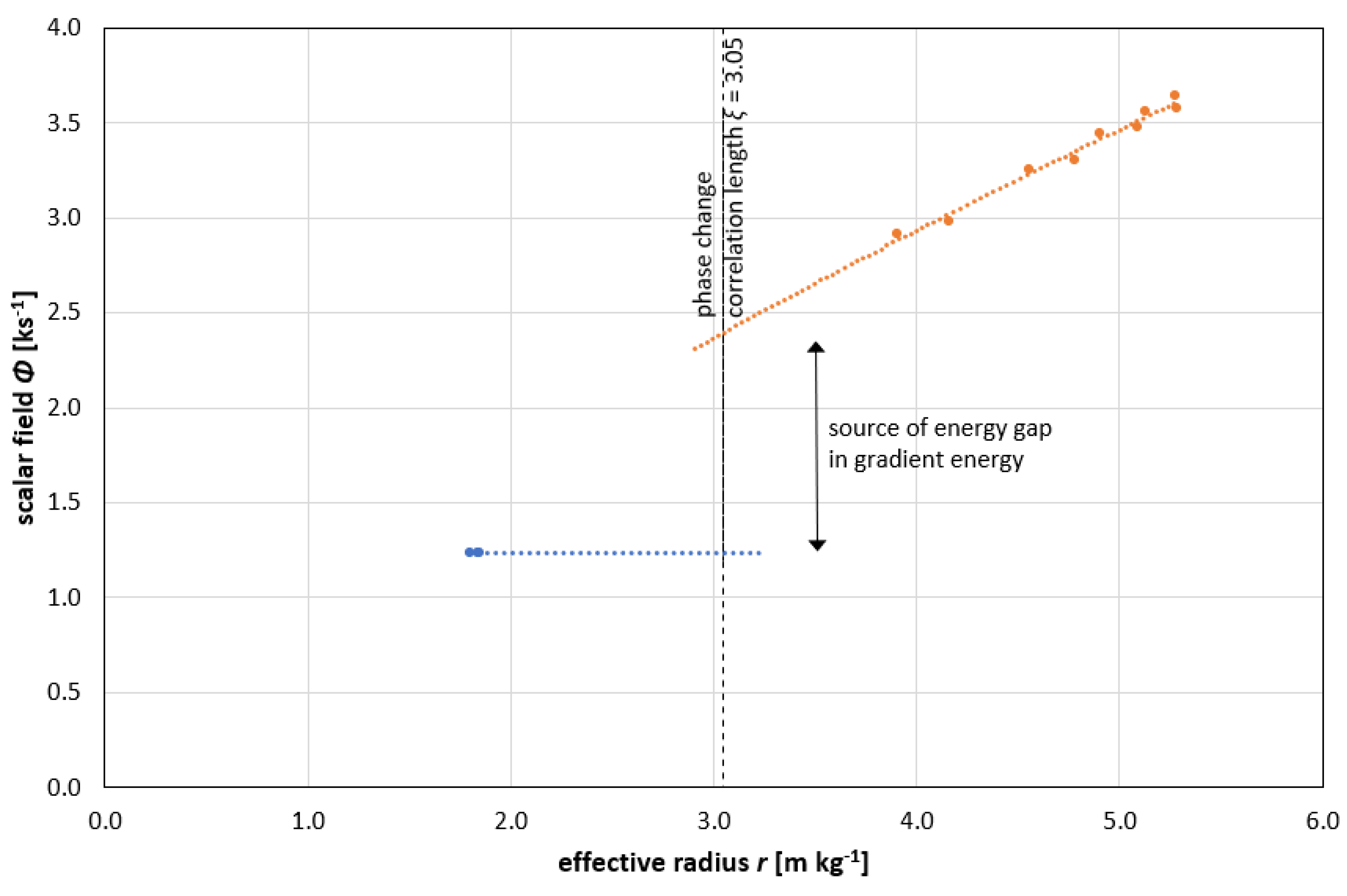

12]. The emergent scalar field (1.2 ≤

Φ ≤ 3.6 ks

-1) is associated with an apparent broken symmetry with gradient energy seemingly determined by the hyperbolic surface of the system where the electric field is excluded. However, gauge symmetry is revealed not to be broken but rather decomposed and synchronized to become more capacious in extent.

A model for the emergent gauge symmetry is presented here to account for energy gains quantifiable through the geometric action of the vacuum manifold, and also subsequently quantifiable in the ‘rolling’ critical behaviour, in terms of Noether-conserved quantities, i.e. energy and angular momentum for the case being considered. Since a topological phase factor, or Berry phase, reveals gauge structure in quantum mechanics [

13], the existence of a parity-time (PT) symmetry may account for quantum mechanical interactions manifesting as real energy [

14] in the work performed by a reciprocating piston expander [

1].

Emergence of the gauge connection field corresponds to a critical correlation length

ξ that represents long-range ordering of magnetic spins, i.e. a magnetic condensate. This divergence is responsible for an energy gap in the gradient energy term analogous to complex energy band gaps reported in non-Hermitian PT symmetric systems [

15]. Also, the existence of a mass gap in QCD is necessary to explain why the strong interaction is strong but only short-ranged. Confirmation of a mass gap would account for the fact that quantum particles have positive masses even though classical waves travel at the speed of light [

16]. Evidence of a Berry phase and the Ginzburg-Landau parameter

κ [

1] thus enables insights into the Yang-Mills action and the mass gap phenomenon in QCD. The current work attempts to elucidate the QCD mass gap problem primarily through the phenomenology of dual superconductivity and magnetic monopole topology.

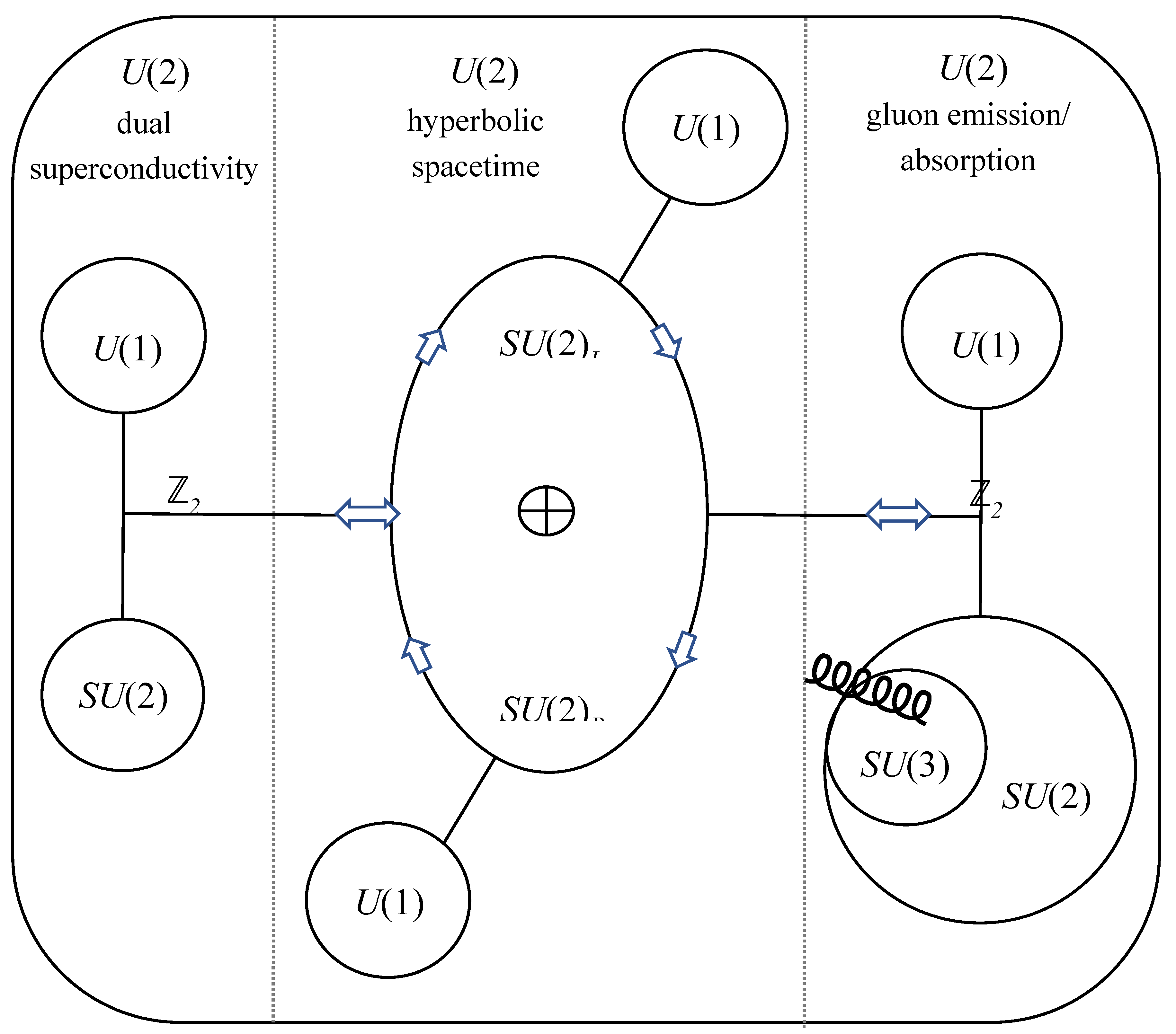

A potential solution is reached through the decomposition and synchronization of multiple processes spanning the domains of dual superconductivity, Minkowski spacetime and fundamental particles. Whilst condensed matter and fundamental particles are conventionally always separated by a TeV threshold, macro-scale QCD phenomena appear to be emergent under the coordinated

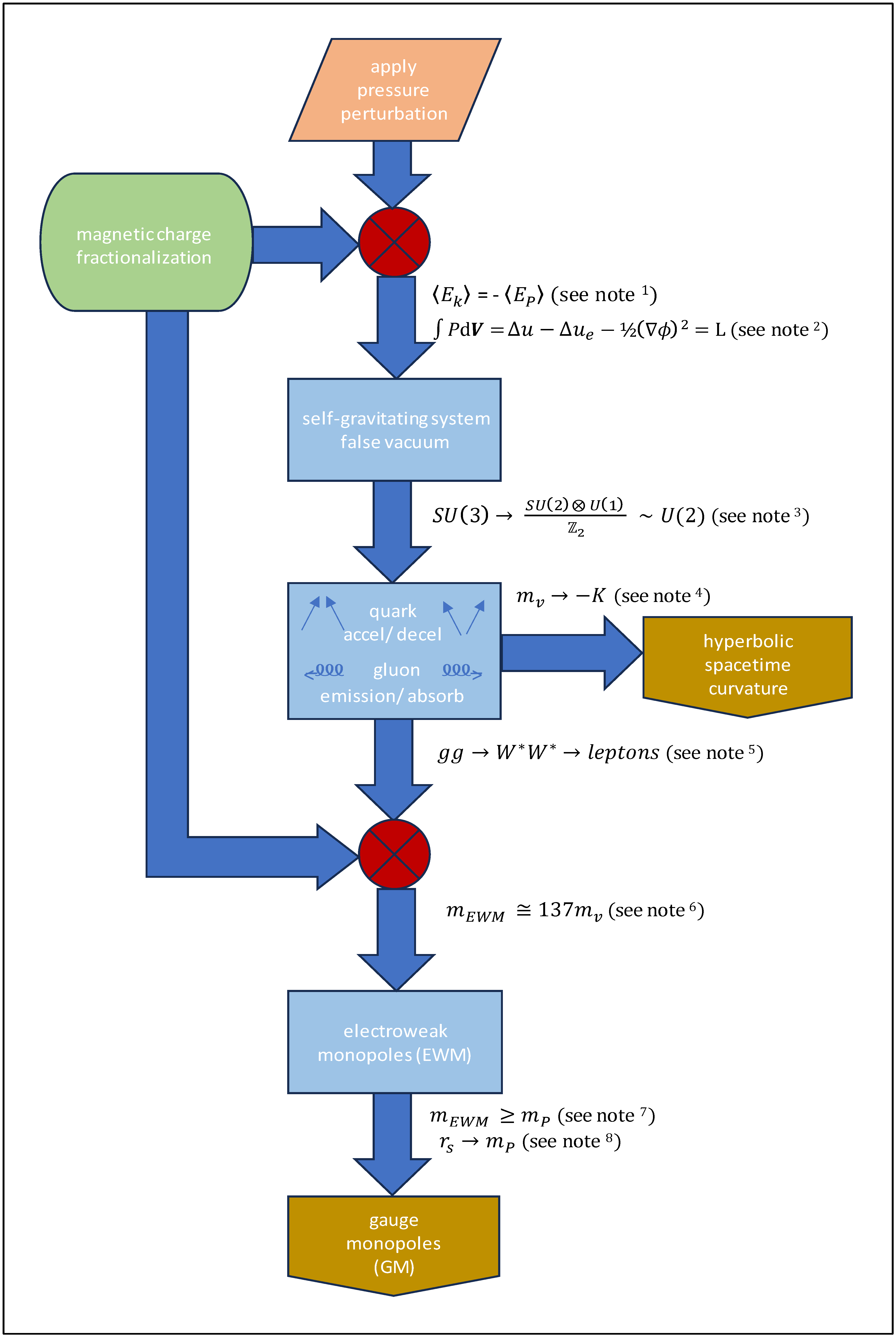

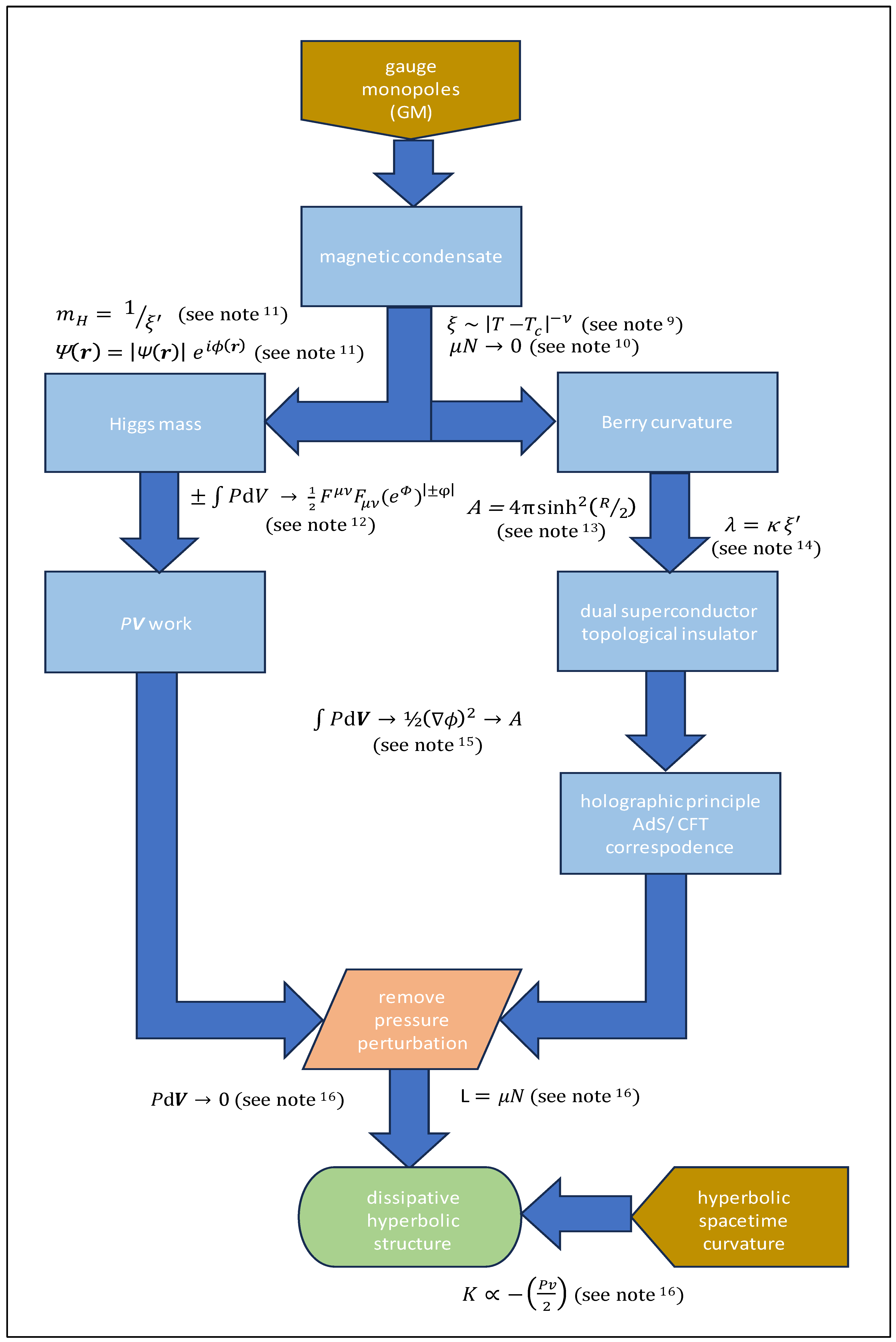

U(2) symmetry group examined below. The accompanying exposition identifies self-organized criticality as the key phenomenon that acts to integrate a complex network of fundamental processes within an internally-consistent model able to account for the macro-scale QCD phenomena uncovered. A process model overview is presented in

Figure 1a and

Figure 1b.

1 Application of the virial theorem reveals self-gravitating behaviour that manifests as false vacuum conditions in the metastable, non-equilibrium system. During pressure perturbation, the time-average kinetic energy ⟨

Ek⟩ is equal to the time-average negative potential energy ⟨

EP⟩, revealing a constant Hamiltonian function for the negative pressure system. The system is identified as a quasi-micro-canonical ensemble in that

N,

E and

v (rather than

V) are constant when work associated with the walls of the vessel is excluded. See Ref. [

5] and §§ 2.2 - 2.3.

2 However, further analysis exposes non-additivity in the fundamental thermodynamic relation of the system. Although increasing internal energy ∆

u is mirrored by an increasing negative excess energy potential ∆

ue, i.e. it describes false vacuum confinement, an additional term is necessary to account for the

PV action. Incorporation of a gradient energy term -½(∇

Φ)

2 (where

Φ represents a scalar field) establishes energy conservation for the Lagrangian function L. See Ref [

1], § 2.4 and

Appendix A.

3 Hyperbolic geometry and group theory are applied to demonstrate isomorphic mapping of momentum between the condensed matter system and QCD particle physics via Minkowski spacetime. Isolated symmetry groups are decomposed and synchronized to establish a common U(2) gauge group able to represent electroweak interactions within a ℤ2 Abelian topology, as requisite for describing gauge monopole condensation. See §§ 3.1 - 3.3.

4 Derivation of the vector boson mass

mV from the scaling laws and Ginzburg-Landau theory is mapped to the thermodynamic description of hyperbolic curvature

K. Both

mV and

K are measured in units m

2s

-2. See §§ 3.1 – 3.3 and

Appendix B.

5 The

U(2) electroweak interaction is fundamental to both hyperbolic manifold curvature

K and the emergence of electroweak monopoles (EWM). Energy conservation across the synchronized

U(2) gauge group allows for quark acceleration/ deceleration leading to indirect gluon emission/ absorption. Simply expressed, a gluon-gluon fusion process

gg would generate intermediate bosons

W*W* that decay into leptons. See §§ 3.2 – 3.4 and

Appendix D and

Appendix E.

6 The interaction of leptons with the fractionalized magnetic charges of the geometrically frustrated crystal-fluid is deemed responsible for the establishment of electroweak monopoles (EWM). The virtual mass

mEWM is of order 137

mV, where 137 is the inverse fine structure constant 1/α, and

mV is the mass of the intermediate

W-boson in the Georgi-Glashow model. The fundamental constant 137 determines the strength of electromagnetic force derived from lepton interaction with fractionalized magnetic charge. See §§ 3.2 – 3.4 and

Appendix D and

Appendix E.

7 Where

mEWM exceeds the Planck mass

mP, gauge monopoles can emerge such that a magnetic condensate is formed. The acquired mass of the complex gauge monopole condensate is the non-extensive Higgs mass

mH (as note

11). See § 3.2 and

Appendix D and

Appendix E.

8 The Schwarzschild radius

rs can then be equated to the Planck mass

mP, with two Planck masses necessary to establish a dipole pair of gauge monopoles within each emergent Euclidean volume. See

Appendix E.

9 Self-organized criticality establishes a ‘rolling’ critical response during pressure perturbation. The magnetic correlation length

ξ is determined through the difference between system temperature

T and the critical temperature

Tc, which is subject to the critical length exponent

ν. See Ref [

1], §§ 2.3 - 2.4, 3.1, 3.3 and

Appendix B.

10 The critical behaviour of the magnetic condensate cuts-off dipolar correlations to allow a correlation length

ξ to be defined. Under these circumstances the interaction potential

μ dissipates so that the interaction energy

μN → 0. See Ref. [

1], §§ 2.3, 3.2.

11 The coherence length

ξ’ describes the magnetic condensate whilst its inverse gives the Higgs mass

mH and associated non-extensive volume changes d

V.

ξ’ also defines the distance over which the dual superconductor can be represented by a macroscopic wavefunction

Ψ(

r). In this case

ξ’ is equal to

ξ with both parameters derived from the scaling laws and Ginzburg-Landau theory. The metastable critical mass

mH is exposed in the exponential coupling of the Higgs-like scalar field

Φ to the magnetization vector field M

s, as represented by the correlation length exponent

ν. The coupling energy exp(3

vΦ) maps to the gauge connection field (as note

12) and is expressed in units of kJ per kg of

mH. See §§ 3.1 – 3.4 and

Appendix A,

Appendix B,

Appendix C,

Appendix D and

Appendix E.

12 PV work is mapped to a complex field

Φ having associated rapidity angle

φ that is coupled to an electromagnetic pseudo-scalar ½

FμνFμν. Lorentz invariance results from the product of the contravariant gradient potential

Fμν and covariant vector

Fμν. Minkowski spacetime vectors can be incorporated into the extended physical decomposition to reveal the coupling energy interface, i.e. the hyperbolic manifold. Cyclic evolution of the gauge field exp(

Φ|±φ|) results from the effective adiabatic property of the constrained false vacuum system that establishes a novel form of the Berry phase, See Ref. [

1], §§ 3.1 - 3.4 and

Appendix B.

13 Hyperbolic surface area

A is derived from the Gaussian radius of curvature

Rg which is in turn derived thermodynamically from system pressure

P and specific volume

v. These parameters also allow for the effective radius

R of a hollow pseudo-sphere to be conjectured. During pressure perturbation, additional surface area may be attributed to a non-equilibrium, superconducting phase-change process, i.e. the topological defects/ vortices arising through gauge monopole pairs and the Euclidean volumes emergent within the hyperbolic manifold. See Ref. [

1], §§ 2.2 - 2.4, 3.1 - 3.2 and

Appendix A and

Appendix E.

14 The scaling laws and Ginzburg-Landau theory reveal a superconducting phase transition from Type II to dual Type I with the associated Ginzburg-Landau parameter

κ. Since the coherence length

ξ’ is also known, the penetration depth

λ of the macro-scale dual superconductor can be found. This determines the extent of QCD vacuum suppression whilst its inverse gives an effective vector boson mass

mv that maps to non-additive hyperbolic curvature

K. See Ref. [

1], §§ 2.3, 3.1 - 3.2, 3.4 and

Appendix C.

15Gradient energy -½(∇

Φ)

2 can be mapped to hyperbolic surface area

A in an expression of holographic duality or the anti-de Sitter/ Conformal Field Theory (AdS/ CFT) correspondence. This hyperbolic geometry results from a renormalization group flow/ scaling flow. In other words, a scaling flow from the boundary surface to the interior is encoded in the geometrical properties of the hyperbolic manifold in accordance with the Einstein field equations. See §§ 3.2 – 3.4 and

Appendix A and

Appendix B.

16 When pressure perturbation ceases, the gradient energy -½(∇

Φ)

2 appears to be conserved in the sterically-induced interaction energy

μN of the crystal-fluid, subject to some limited dielectric relaxation. Since hyperbolic manifold curvature

K is retained in the crystal-fluid structure, there is negligible net loss of mass as

mH and

mV dissipate. The macroscopic wavefunction

Ψ(

r) exists only for the duration of pressure perturbations whilst the Hamiltonian remains constant. However, the rest states of the Lagrangian function L are ‘propped’ and metastabilized through dissipative structuring of the crystal-fluid. See Ref. [

1] §§ 2.2 and 3.2.

Conclusions

Experimental investigations uncover a macro-scale dual superconductor linked to the emergence of a gauge field and the associated synchronization of a U(2) symmetry group that encompasses dual superconductivity, Minkowski spacetime and quantum interactions. Combining Ginzburg-Landau theory with the scaling laws reveals a penetration depth and a coherence length that characterize the macro-scale dual superconductor. The penetration depth determines the extent of QCD vacuum suppression whilst its inverse gives the effective vector boson mass resulting in hyperbolic curvature. The coherence length describes the gauge monopole condensate whilst its inverse gives the Higgs mass and non-extensive volume changes. The macro-scale dual superconductor signifies long-range entanglement within a magnetic condensate displaying relativistic behaviour, whilst hyperbolic curvature of the vacuum manifold is attributed to additional quantum interactions.

A ‘rolling’ critical response is enabled through structural anisotropy in a crystal-fluid held under false vacuum conditions. Self-organized criticality establishes a U(2) electroweak symmetry that spans both a macro-scale dual superconducting system and a micro-scale quark-gluon system via electroweak interactions. Under external pressure perturbation, dissipative restructuring of the metastable crystal-fluid allows for angular momentum to be transferred to or from the quark-gluon system to establish a gauge monopole condensate with associated dual superconductivity.

The complex reorganization of systems with high energy degeneracy is responsible for asymptotic freedom, as characterized by the emergence of variable negative potential that maintains constant total energy. In these systems, the excess negative potential arises from an effective vector boson mass that imposes variable hyperbolic curvature on the embedding manifold thus creating strong local gravitational effects. This ‘strong gravity’ produces variable effective magnetic permeability, establishing the pre-conditions for spontaneous magnetism with associated spontaneous magnetic field to emerge. Associated electroweak interactions appear responsible for the creation of electroweak monopoles that go on to form a condensate of complex gauge monopoles, thus completing the requirements necessary for spontaneous magnetism to either emerge from or return to the embedding manifold. Changes in the associated Higgs mass are responsible for either positive expansion or negative contraction work in the piston expander.

Conservation of energy and angular momentum across the condensed matter and quantum domains is linked to time and space symmetries in agreement with Noether’s theorem. It has been widely conjectured that gauge monopoles are associated with the U(2) group and ℤ2 topology, which enables a critical correlation length to be established. For the synchronized U(2) group, the effective vector boson mass is attributed to indirect quark emission/ vacuum absorption of gluons from acceleration, and indirect vacuum emission/ quark absorption of gluons from deceleration.

The emergent gauge structure combines with the effective adiabatic property of the constrained false vacuum system to establish an ‘excited-states’, degenerate Berry phase. Since the parameter space of the quantum mechanics is the spacetime manifold of an Abelian gauge theory, the closed cycle of the Berry phase is formally identical to both Wilson loop and ‘t Hooft loop observables describing the negative potential of the gluon field. This geometrical phase is responsible for topological ordering in the dual Type-I superconductor. The excluded electric field represents the gapless surface of a topological insulator that is protected from external perturbations through ℤ2 Abelian topology.

The gradient energy term of the Lagrangian maps to a macroscopic wavefunction through which the energy spectrum becomes entirely real and observable. Such behaviour is also found in PT symmetric systems that are not isolated from the environment (i.e. non-adiabatic) but subject to highly constrained interactions. Conservation of energy and momentum are determined through the symmetry of Lorentz boosts, i.e. symmetries in both time and space, in a system containing both Hermitian and non-Hermitian elements. A net energy gain is linked to changing symmetry relations that enable the emergence of the Higgs mass from changes in quantum confinement energies.

The complex parameter field is revealed as the order parameter that emerges to signify a superconducting phase transition from Type-II to a dual of Type-I. The phase transition is consistent with Ginzburg-Landau theory that describes gauge-invariant coupling of a scalar field to the Yang-Mills action in QCD. The Higgs-like scalar field emerges out of the transition from gapped Type-II superconductivity to gapless dual Type-I superconductivity to establish a reciprocal gap in the gradient energy. The gradient energy identifies with the scaling flow of an AdS/ CFT correspondence encoded into the geometrical properties of the hyperbolic manifold. The point at which the critical coherence length and penetration depth emerge in the macro-scale dual superconductor is conjectured as the low-energy, infrared bound of the micro-scale SU(3) QCD mass gap.

Emergence of a Higgs mass displaying a magnitude one hundred times greater than the initial sample mass is consistent with the necessity for electroweak magnetic monopoles in the Standard Model of particle physics. It is proposed that the transient Higgs mass as identified derives from the interaction of the Higgs-like scalar field with the gauge monopole condensate of the Type-I dual superconductor.

The complex parameter field exists only during pressure perturbations, although the Hamiltonian remains constant during perturbation. The resting values of total energy are then ‘propped’ and metastabilized through dissipative structuring of water ice cages. The gradient energy is thereby conserved in the sterically-induced interaction energy of the crystal-fluid material such that it becomes real and observable.

Appendix A. Recorded Data and Calculated Properties As Reproduced from Reference [1]

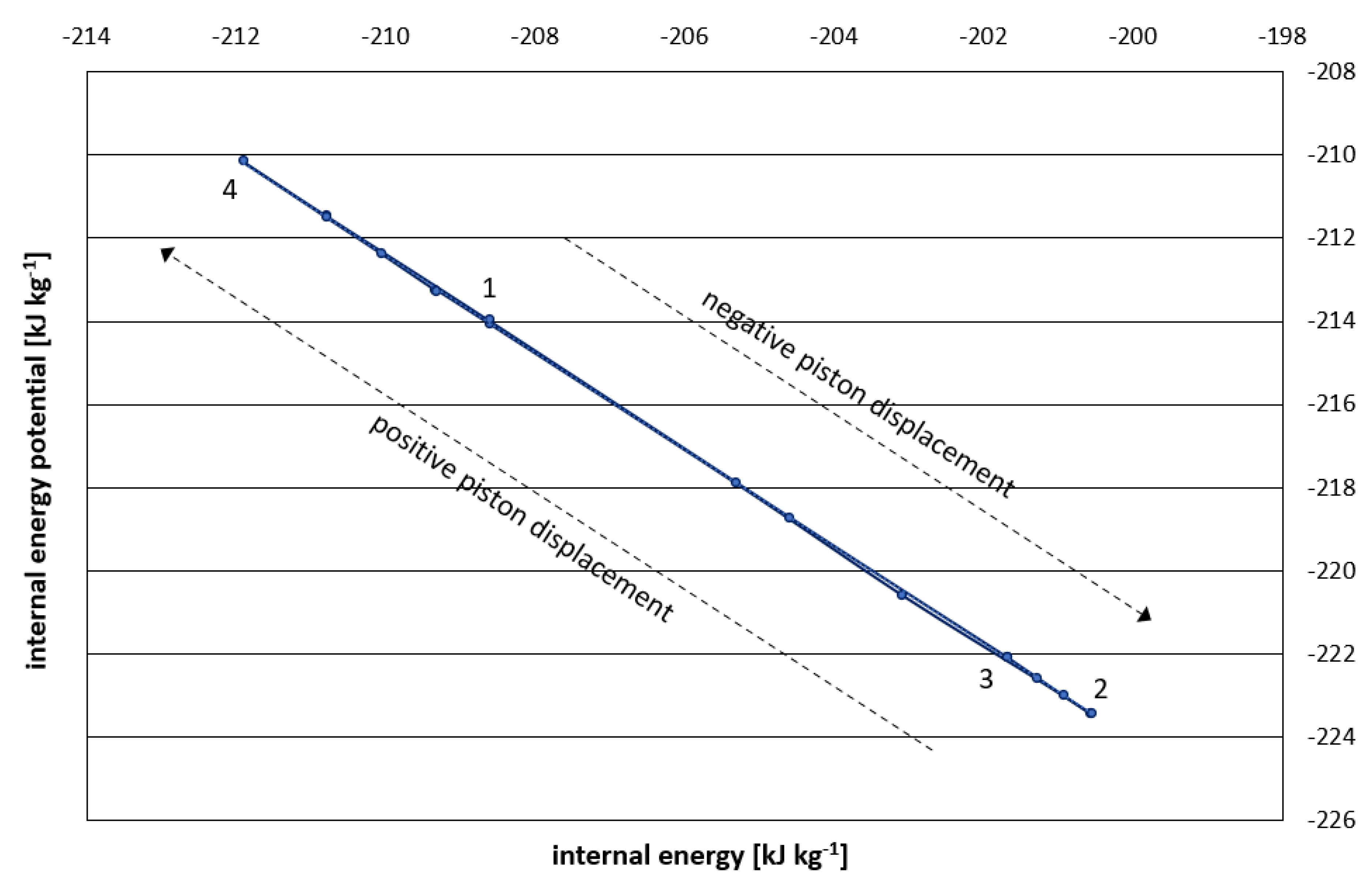

Points 1-4 identify particular stages of the work cycle in a low-energy system; Stage 1-2 corresponds to negative displacement of the 0.5 litre piston expander and Stage 3-4 corresponds to positive displacement.

Table A1.

Recorded and calculated thermodynamic properties of a typical piston expander cycle.

Table A1.

Recorded and calculated thermodynamic properties of a typical piston expander cycle.

| |

Temperature

T (K)

|

Pressure

P (MPa)

|

specific volume

v (m3 kg-1)

|

| Point 1 |

269.3 |

0.29 |

0.0015 |

| Point 2 |

271.7 |

0.62 |

0.0015 |

| Point 3 |

271.4 |

0.61 |

0.0015 |

| Point 4 |

268.6 |

0.25 |

0.0015 |

| |

internal energy

u (kJ kg-1)

|

entropy

s (kJ kg-1 K-1)

|

Volume

V (m3)

|

| Point 1 |

-209.3 |

0.79 |

0.000505 |

| Point 2 |

-200.6 |

0.83 |

0.000005 |

| Point 3 |

-201.7 |

0.82 |

0.000005 |

| Point 4 |

-211.9 |

0.78 |

0.000505 |

| displacement |

∆Ts heat

(kJ kg-1)

|

∆Pv work

(kJ kg-1)

|

∆PV work

(kJ kg-1)

|

| -ve 1-2 |

1.93 |

0.0015 |

642.9 |

| +ve 3-4 |

-2.23 |

-0.0015 |

-568.6 |

| |

enthalpy

h (kJ kg-1)

|

Gibbs free energy

G (kJ kg-1)

|

Helmholz free energy

F (kJ kg-1)

|

| Point 1 |

-208.9 |

-422.5 |

-423.0 |

| Point 2 |

-199.6 |

-424.0 |

-424.9 |

| Point 3 |

-200.7 |

-423.8 |

-424.7 |

| Point 4 |

-211.5 |

-422.1 |

-422.4 |

| |

1 |

2 |

1 – 2 |

| |

Pvfrom

TD potentials

(kJ kg−1)

|

Pvfrom REFPROP

(kJ kg−1)

|

ExcessPv

(kJ kg−1)

|

| Point 1 |

0.43 |

0.44 |

-0.01 |

| Point 2 |

0.94 |

0.93 |

0.01 |

| Point 3 |

0.92 |

0.92 |

0 |

| Point 4 |

0.37 |

0.38 |

-0.01 |

| |

1 |

2 |

1 – 2 |

| |

Ts from

TD potentials

(kJ kg−1)

|

Ts from REFPROP

(kJ kg−1)

|

excess Ts

(kJ kg−1)

|

| Point 1 |

-422.1 |

213.7 |

-635.8 |

| Point 2 |

-423.0 |

224.4 |

-647.4 |

| Point 3 |

-422.8 |

223.0 |

-645.8 |

| Point 4 |

-421.7 |

210.5 |

-632.2 |

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 – 2 + 3 |

| |

excess Ts

(kJ kg−1)

|

excessPv

(kJ kg−1)

|

G

(kJ kg-1)

|

excess u

(kJ kg−1)

|

| Point 1 |

-635.8 |

-0.01 |

-422.5 |

-1058.3 |

| Point 2 |

-647.4 |

0.01 |

-424.0 |

-1071.4 |

| Point 3 |

-645.8 |

0 |

-423.8 |

-1069.6 |

| Point 4 |

-632.2 |

-0.01 |

-422.1 |

-1054.3 |

Table A2.

Gradient energy where the Gibbs energy is associated with a phase-change process.

Table A2.

Gradient energy where the Gibbs energy is associated with a phase-change process.

| |

1 |

2 |

1 - 2 |

| |

u (from TD potentials) - G

(kJ kg−1)

|

internal energy

u

(kJ kg-1)

|

Excess u

(kJ kg−1)

|

| Point 1 |

-422.6 |

-209.3 |

-213.3 |

| Point 2 |

-424.0 |

-200.6 |

-223.4 |

| Point 3 |

-423.8 |

-201.7 |

-222.1 |

| Point 4 |

-422.0 |

-211.9 |

-210.1 |

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 - 2 - 3 |

| |

internal energy u

(kJ kg-1)

|

excess u

(kJ kg−1)

|

(kJ kg−1)

|

gradient energy §

½(∇Φ)2

(kJ kg−1)

|

| Point 1 |

-209.3 |

-213.3 |

651.8 |

-647.9 |

| Point 2 |

-200.6 |

-223.4 |

8.9 |

-5.0 |

| Point 3 |

-201.7 |

-222.1 |

8.3 |

-4.4 |

| Point 4 |

-211.9 |

-210.1 |

576.9 |

-578.7 |

Table A3.

Calculation of hyperbolic surface area.

Table A3.

Calculation of hyperbolic surface area.

| |

1 |

2 |

1 - 2 |

|

| |

outer radius

r1 = 5/(2Pv)

(m kg−1)

|

inner

radius r2

(m kg−1)

|

effective radius

R = r1 – r2

(m kg−1)

|

surface area

4πsinh2(R/2)

(m2 kg−1)

|

| Point 1 |

5.8 |

0.5 |

5.3 |

606.2 |

| Point 2 |

2.7 |

0.8 |

1.8 |

14.0 |

| Point 3 |

2.7 |

1.0 |

1.7 |

11.6 |

| Point 4 |

6.8 |

1.5 |

5.3 |

611.9 |

Derivation of the effective system radii is detailed in

Appendix B of [

1].

Table A4.

Response functions and critical exponent family as calculated by REFPROP [

17].

Table A4.

Response functions and critical exponent family as calculated by REFPROP [

17].

| |

density

ρ (kg m-3)

|

specific heat

capacity

Cv (kJ kg-1 K-1)

|

specific heat

capacity

Cp (kJ kg-1 K-1)

|

isothermal

compressibility

KT (kPa-1)

|

| Point 1 |

665.1 |

2.871 |

3.714 |

0.4557 |

| Point 2 |

663.7 |

2.850 |

3.698 |

0.4484 |

| Point 3 |

663.9 |

2.844 |

3.694 |

0.4462 |

| Point 4 |

665.6 |

2.869 |

3.712 |

0.4547 |

| |

Critical Exponent |

| displacement |

heat capacity

α (Cv / Cp)

|

order parameter

β

|

susceptibility

ϒ

|

-ve 1-2

(T – Tcrit)

|

0.222 / 0.286 |

0.384 |

0.916 |

+ve 3-4

(T – Tcrit)

|

0.223 / 0.287 |

0.515 |

0.765 |

| |

Critical Exponent |

| displacement |

equation of

state

δ

|

correlation

length

ν (Cv / Cp)

|

power law

decay

ρ (Cv / Cp)

|

- ve 1-2

(T – Tcrit)

|

3.385 |

0.593 / 0.571 |

0.455 / 0.396 |

+ve 3-4

(T – Tcrit)

|

2.485 |

0.592 / 0.571 |

0.708 / 0.660 |

Table A5.

Magnetic properties derived from critical exponents.

Table A5.

Magnetic properties derived from critical exponents.

| |

reduced volume (V-Vc)/Vc |

spontaneous magnetism

Ms

(A m-1 kg-1)

|

spontaneous magnetic induction Bs

(T kg-1)

|

spontaneous external field

Hs

(A m-1 kg-1)

|

| Point 1* |

0.198 |

1.418 |

3.265 |

1.846 |

| Point 2 |

0.952 |

1.011 |

1.036 |

0.026 |

| Point 3* |

25.0 |

0.394 |

0.099 |

-0.295 |

| Point 4 |

0.329 |

1.380 |

1.380 |

0.845 |

| |

1 |

2 |

│2│ +│1│ |

│1│ : │2│ |

| displacement |

(kJ kg-1)

|

(kJ kg-1)

|

inequality

(kJ kg-1)

|

ratio |

| -ve 1-2 |

1.23 x 10-3

|

-5.52 x 10-3

|

6.75 x 10-3

|

1 : 4.5 |

| +ve 3-4 |

5.07 x 10-4

|

-3.17 x 10-3

|

3.68 x 10-3

|

1 : 6.3 |

| |

3 |

4 |

│3│ + │4│ |

│3│ : │4│ |

| displacement |

(kJ kg-1)

|

(kJ kg-1)

|

inequality

uvac

(kJ kg-1)

|

ratio |

| -ve 1-2 |

-1.23 x 10-3

|

2.75 x 10-4

|

1.51 x 10-3

|

4.5 : 1 |

| +ve 3-4 |

-2.74 x 10-3

|

4.39 x 10-4

|

3.18 x 10-3

|

6.3 : 1 |

The difference in the inequalities is attributed to timing inconsistencies when recording the magnetic properties noted in

Table A5. Values for vacuum energy contributions would be based upon the following relationship:.

Table A7.

Effective Euclidean volume vs. hyperbolic volume.

Table A7.

Effective Euclidean volume vs. hyperbolic volume.

| |

net radius

r = r1 – r2

|

Euclidean volume

~ exp(3r)

|

Euclidean volume

factor (f1) vs.

min. at Point 3Ϯ

|

| Point 1 |

5.3 |

7409663 |

44271 |

| Point 2 |

1.8 |

250 |

1.3 |

| Point 3 Ϯ |

1.7 |

167 |

1.0 |

| Point 4 |

5.3 |

7618473 |

45519 |

Vacuum permeability

μ0 is, historically, a universal constant with a value of 4π x 10

-7 T-m A

-1 in flat, free space [

22]. However, the increase in effective Euclidean volume directly relates to the increase in effective permeability, i.e. the vacuum energy potential increases proportionally with effective Euclidean volume.

|

|

|

|

| displacement |

space density factor (f1) |

ln (f1) |

ln (f1)/ 3.5 SOC steps |

| -ve 1-2 |

44271 |

10.70 |

3.06 ǂ

|

| +ve 3-4 |

45519 |

10.73 |

3.06 ǂ

|

ǂ SOC – self-organized criticality – values consistent with the derived correlation length

ξ = 3.05, as detailed in

Appendix B.

Table A8.

Comparison of calculated gradient energy with calculated coupling energy.

Table A8.

Comparison of calculated gradient energy with calculated coupling energy.

| |

gradient energy ^

½(∇Φ)2

[kJ kg-1]

|

scalar potential ^

∇Φ

[km s-1]

|

scalar field

Φ

[ks-1]

|

coupling energy

exp(3vΦ)

[kJ kg-1]

|

| Point 1 |

-651.8 |

-36.1 |

3.6 |

651.8 |

| Point 2 |

-8.9 |

-4.2 |

1.2 |

8.9 |

| Point 3 |

-8.3 |

4.1 |

1.2 |

8.3 |

| Point 4 |

-576.9 |

34.0 |

3.6 |

576.9 |

Gradient energy and coupling energy are associated with the emergent Higgs mass mH of 0.33 kg.

Appendix B. Critical Correlation Length and Lorentz Rotations

Lorentz rotations correspond to changes in hyperbolic surface area. The concept of rapidity [

60] is commonly used as a measure of relativistic velocity and simplifies the Lorentz rotational transformation formulae. Rapidity ϕ is defined as the hyperbolic angle that differentiates two frames of reference in relativistic motion with each frame having time and distance coordinates. Since the distance coordinate on a hyperbolic manifold is determined by the critical exponent for correlation length

ν, then

ν can be taken as the dimensionless group parameter of rapidity, i.e. d

ν → ϕ.

Since tanh(ϕ) = v/

c, the 3-dimensional result is:

The Lorentz transformation for length contraction/ expansion x′ then gives:

such that x′ = correlation length

ξ = 3.05 and d

V = 28.4.

│T – Tc│ ≈ 0.15K which, in terms of self-organized criticality, represents approximately 3.5 equal steps with an average critical approach temperature of 0.15K.

The calculated overall volume correlation ratio is (3.5 x 28.4 = 99.4) as compared to the experimentally derived value of 100 recorded in

Table A1. In

Appendix C, the derived Higgs mass

mH is also approximately 100 times greater than the initial mass of the crystal-fluid. The result is consistent with predictions from the Standard Model of particle physics where the Higgs mass

mH of the unobserved electroweak magnetic monopole is approximately 137 times greater than the

W-boson [

72]. Discovery of this elementary particle represents the electroweak generalization of the Dirac monopole [

73]. Further analysis can be found in

Appendix D and

Appendix E.

Appendix C. Ginzburg-Landau Theory

The Ginzburg-Landau (GL) theory of superconductors is founded upon a general approach to continuous phase transitions that are accompanied by a change in symmetry [

20]. Landau proposed that these phase transitions are characterized by an order parameter that is zero in the disordered state above

Tc but obtains a non-zero value below

Tc. For the relatively simple case of a magnet, its magnetization M(

r) provides a suitable order parameter.

For a superconducting system, GL postulates the existence of a complex order parameter

Ψ, assumed to be an unspecified physical quantity that characterizes the state of the system. For the normal metallic state above the superconductor

Tc it is zero, whilst for the superconducting state below

Tc it is non-zero, such that:

However, for the non-metallic dual superconducting state observed experimentally, the system is instead characterized by:

where M

s is the spontaneous magnetism and

Ψ represents the complex form of the coupling energy (e

iΦ)

3v, i.e. the gauge connection field. For 0 < M

s < 1 the system is characterized by an ‘auxiliary’ order parameter H

s, the spontaneous magnetic field.

GL assumes that the real free energy of the superconductor varies smoothly and can only depend upon the complex value of |

Ψ| so that the free energy density is given by:

where:

fs(T) and fn(T) are the superconducting state and normal state free energy densities, respectively

and

α(T) and β(T) are generally phenomenological, temperature dependent parameters.

The order parameter

Ψ(

r) is found by minimizing the free energy of the system (i.e. during a phase transition) which, through further mathematical manipulation, yields an effective non-linear Schrödinger equation:

where:

ℏ is the reduced Planck’s constant,

and

m* determines the energy cost associated with gradients in the order parameter

Ψ(

r) to define an effective mass for the quantum system where

m* = 2

me and

me is the bare electron mass in the normal metallic state (or

m* = mH of a virtual condensed complex monopole in the dual superconductor- see

Appendix D).

The non-linearity introduced by the second term in the bracket of (39) ensures that the quantum mechanical principle of superposition does not apply, i.e. it cannot be normalized to zero.

GL theory is developed further to incorporate: inhomogeneous systems introducing a gradient into the order parameter; the effect of external perturbations; and the effect of a magnetic field. The free energy density of the superconductor then takes the form [

20]:

where:

2e is the net charge for a Cooper pair of electrons with positive sign convention

and

A is the electromagnetic vector potential

The full GL equations (not included here) are obtained by minimizing the free energy with respect to fluctuations in the order parameter and the vector potential

A. These equations predict the existence of two characteristic lengths in a superconductor [

20]:

the coherence length

ξ’(

T):

(the distinction between coherence length

ξ’(

T) and correlation length

ξ(

T) is explained in [

43])

and the London penetration depth

λ(

T):

where:

α(T) = ά|T – Tc|

Both lengths diverge as Tc → T.

The ratio κ = λ(T)/ξ’(T) is known as the Ginzburg-Landau parameter where κ > 1/√2 identifies a Type-II superconductor whilst κ < 1/√2 identifies a Type-I superconductor. The ratio is dimensionless and independent of temperature within GL theory.

The transition from Type-II to Type-I and the effect of Abrikosov vortices is related to the experimental results described in [

1] from which

Figure 6 is updated to reflect the latest findings:

Figure 6.

Critical exponents reveal a magnetic phase transition and superconductor-like behaviour for a negative pressure perturbation. The initial response between 0 < Ms < 0.5 appears as diamagnetism (Hs < 0) and peaks at a lower critical field point Mc1, a result of high susceptibility χ such that Ms >> Bs. Diamagnetism is then completely destroyed at Ms = 1, which represents an upper critical field point Mc2. For Ms > 1 both Mc1 and Mc’ become ‘rolling’ critical values.

Figure 6.

Critical exponents reveal a magnetic phase transition and superconductor-like behaviour for a negative pressure perturbation. The initial response between 0 < Ms < 0.5 appears as diamagnetism (Hs < 0) and peaks at a lower critical field point Mc1, a result of high susceptibility χ such that Ms >> Bs. Diamagnetism is then completely destroyed at Ms = 1, which represents an upper critical field point Mc2. For Ms > 1 both Mc1 and Mc’ become ‘rolling’ critical values.

For H

s < 0, the profile resembles Type-II superconductor behaviour, although it is large rather than negative values of susceptibility

χ that are held responsible for the diamagnetic effect. The diamagnetism peaks at M

c1, the lower critical field, corresponding to minimal magnetic flux density B

s. Moving beyond M

c1 towards M

c2 the upper critical field, B

s increases until all superconducting behaviour is destroyed at M

s = 1, H

s = 0. For 0 < M

s < 1, the Ginzburg-Landau parameter

κ is determined:

i.e. a Type-II superconductor classification.

For Ms > 1, Hs takes positive values as the susceptibility χ falls below unity. A new value for the critical field Mc’ is deemed to be established at or to the right of the Mc2 value. Both Mc2 and Mc’ become ‘rolling’ critical values such that 0.9 ≤ Mc2/ Mc’ ≤ 1.0 as determined by calculations of κ below. For this region κ < 1/√2 which is consistent with Type-I superconducting behaviour. Here, large values of excluded Bs coincide with exclusion of the electric field E to establish dual superconducting behaviour.

If Mc’ has a minimum value of 1.0 Am-1kg-1 then at the positive displacement phase transition κ = 0.707.

Since ξ’(T) is equal to 3.05 m, the penetration depth λ(T) = 2.2 m

to give the vector boson mass mV (1/ λ(T)) ≤ 0.46 kg

in the constant energy Hamiltonian, kg ∝ m-2s2 as derived through dimensional analysis with E = mc2

so that mV can be expressed in units of Gaussian curvature m2s-2, i.e. the reciprocal

then comparing to the Gaussian curvature calculations using equation (21):

K ∝ -

Pv/2 which at Point 3 gives - (610 x 0.0015)/ 2 = - 0.46 m

2s

-2 [

1]

and at Point 1 gives - (290 x 0.0015)/ 2 = - 0.22 m

2s

-2 [

1]

∴ 0.22 m2s-2 ≤ mV ≤ 0.46 m2s-2, i.e. the conjugate transpose

(for unitary group U(2), the conjugate transpose is equal to the reciprocal)

and 0.65 ≤ κ ≤ 0.707

The Higgs mass mH (1/ ξ’(T)) = 0.33 kg

which determines the non-extensive volume dV (mH/ ρ)

where

ρ is the density of the crystal-fluid material with an approximate value of 664 kg m

-3 [

1]

to give dV = 0.33/ 664 x 10-3 = 0.5 litre, i.e. the swept volume of the piston expander.

Also, mH is approximately 100 times greater than the initial mass of the crystal-fluid (at 3.5 grams, approx.), supporting the hypothesis that mH quantifies changes in quantum confinement energies resulting from the conservation of angular momentum under critical false vacuum conditions.

For spontaneous diamagnetism seen where H

s < 0, and below the critical correlation length

ξ in

Figure 4, the system appears to be in a gapped superconducting state with H

s acting as an ‘auxiliary’ order parameter. The effects of topological defects in the dual superconductor seem to reflect those of magnetic impurity states that fill-in the energy gap in conventional superconductors. Topological defects may be created by chromoelectric flux tubes, or penetrating vortices, resulting from the chromomagnetic condensation of gauge monopoles, which in turn enables the formation of quark-antiquark pairs together with an inherent confinement mechanism. Where H

s > 0, and above the critical correlation length

ξ, the system can be described as being in a protected gapless superconducting state with

Ψ(

r) as the complex order parameter. Similarly, it has been shown [

74,

75] that the transition between the gapped and gapless superconducting states in the Abrikosov-Gor’kov theory of a superconducting alloy with paramagnetic impurities is of the Lifshitz type, i.e. a topological phase transition where the number of the components of topological connectivity on the Fermi surface undergoes changes under the influence of different factors; pressure, magnetic field, doping, etc.

Appendix D. Electroweak Monopole Analysis

The 3.5 grams of sample comprises 0.22 mol. approx. or: 1.3 x 1023 molecules

Energy of Higgs mass mH (0.33 kg): 1.85 x 1026 GeV/c2

‘t Hooft [

76] constructs an electroweak monopole mass of order 137

mV, where

mV is the mass of the intermediate

W-boson in the Georgi-Glashow model [

77]. The stated value of < 53 GeV/

c2 in an

SO(3) compact Lie group has now been superseded by the experimentally determined value of 80 GeV/

c2 from the LHC at CERN.

Next, the ratio of

mH to

mV in Ginzburg-Landau theory (see

Appendix C) is: 1 : ≤ √2

To give mH of a virtual* condensed complex monopole as (80 x 137)/ √2 : ≥ 7.75 TeV/c2

(NB: compare (137/√2 = 96.9) with the x100 value given in reference [

72])

Then, the quantity of complex monopoles (1.85 x 1023/ 7.75) : ≥ 2.39 x 1022

Ratio of (complex monopoles : molecules) : 1 : ≤ 5.4

to deliver a sensible result for the tetrahedrally frustrated crystal-fluid

* total number of monopoles must exceed the Planck mass in order to condense.

Appendix E. Gauge Monopoles and the Planck Mass

0.33 kg of Higgs mass (i.e. condensed complex gauge monopole mass): 1.85 x 1026 GeV/c2

Planck mass: 1.22 x 1019 GeV/c2

To give a Planck mass factor: 15.2 x 106

Average critical ‘space density’ or ratio of Euclidean to hyperbolic volume: 7.51 x 106

To give an emergent Planck mass factor per Euclidean volume: 2.02

A similar result is obtained when expressed in terms of the Schwarzschild radius:

Avg. work of the piston expander: 614 kJ kg-1

Avg. work from 0.33 kg Higgs mass mH : 202.7 kJ

With associated power: 8.5 kW

From W = F x d, the force is calculated: 2896 kN

Then F = mH x a gives the acceleration: 8776 x 103 m s-2

Since hyperbolic curvature of the system establishes ‘strong gravity’, a → G

To give the Schwarzschild radius based upon the Higgs mass rs = 2a mH /c2 :

rs = (2 x 8776 x 103 x 0.33/ c2): 6.44 x 10-11 m

The swept volume of the piston expander is 0.5 litre such that:

Unit vol. of single Planck mass (0.5 litre/ 15.2 x 106): 3.29 x 10-11 m3

where the Planck mass factor has been determined previously above.

Ratio of rs to unit volume: 1.96 : 1

The Schwarzschild radius is thereby equated to the Planck mass, with two Planck masses necessary to establish a dipole pair of gauge monopoles within each emergent Euclidean volume. It then follows that the number of electroweak monopoles required to form a Planck mass, i.e. a

U(2) gauge monopole is approximately: