Submitted:

29 August 2024

Posted:

02 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. CFD Numerical Wave Tanks

- NWTs allow testing at any scale (including full scale). Whereas, PWTs inherently suffer scaling effects, being scaled down versions of the real ocean environment.

- Easy, non-invasive measurements of all variables. PWTs require measurement equipment, which are prone to noise and measurement error, in addition to possibly interfering the dynamics of the system being measured. NWTs allow all variables to be measured everywhere at any time.

- Specialist equipment and construction of prototype devices are not required. Seabed topographies can easily and rapidly be installed and altered. Easy and automated variation of any parameter. Things requiring days/weeks to physically manufacture and install in the real world for PWTs, can be generated in seconds/minutes in NWTs.

- Availability and accessability. There are limited PWT facilities globally, whose availability is generally booked-out months in advance. NWTs are constrained only by the availability of computational resources, which are vastly more accessible than PWT accessibility. Multiple NWT experiments can run at the same time.

1.2. Exploiting Axisymmetry for Accelerated Simulations

1.3. Significance of High-Accuracy Validation Data

1.4. Outline of Paper

2. Heaving Sphere Study

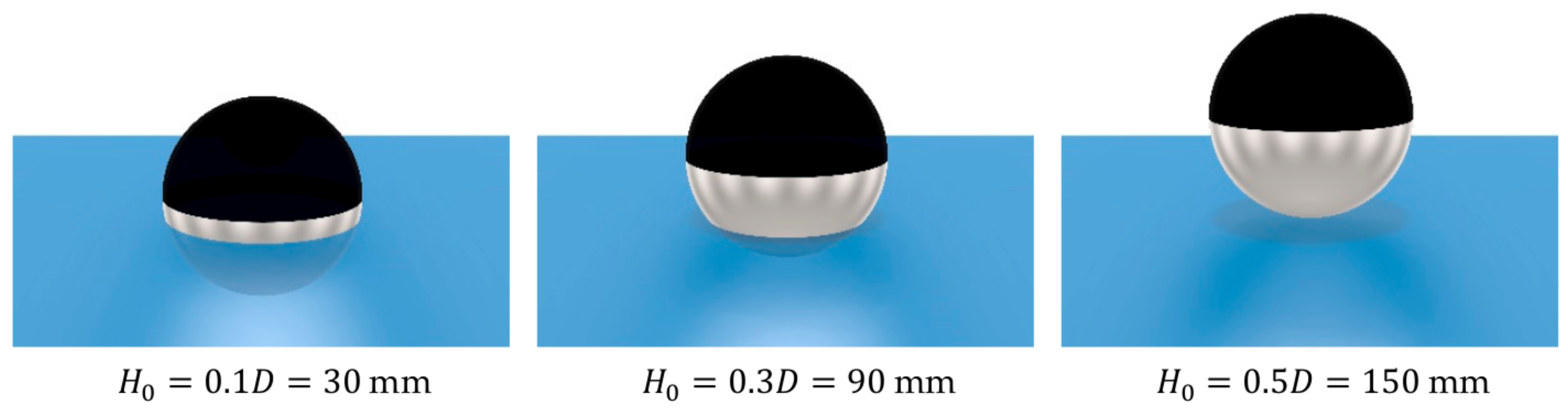

2.1. Test Case

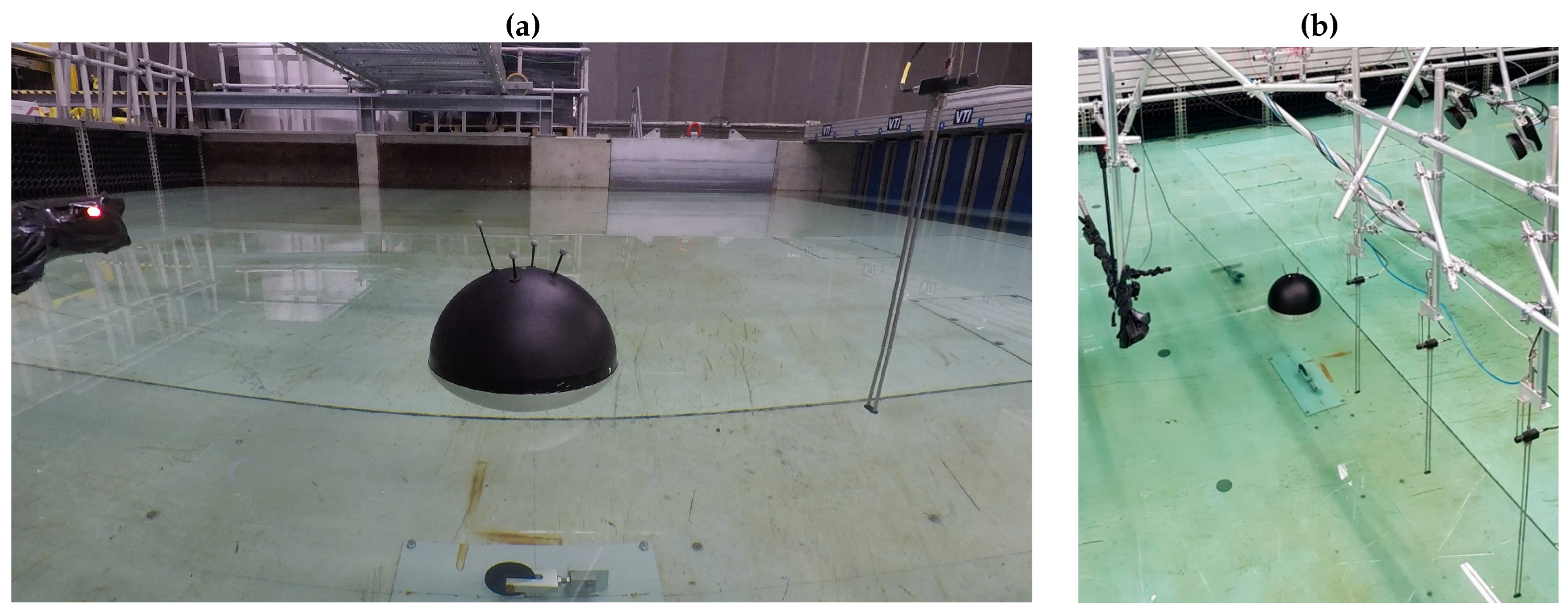

2.2. Description of Physical Experiments

2.2.1. Properties of the Sphere and the PWT

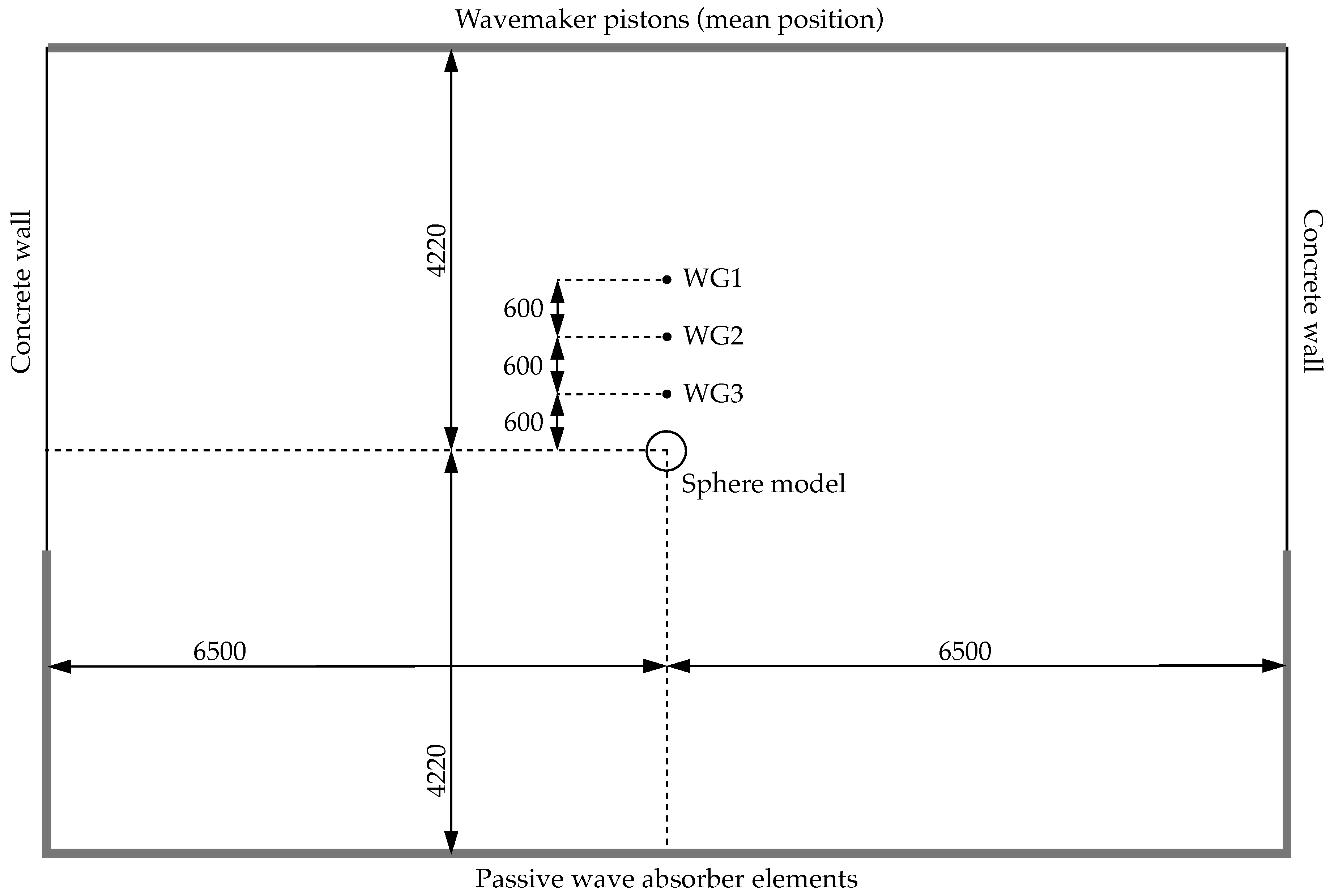

2.2.2. Measurement Equipment

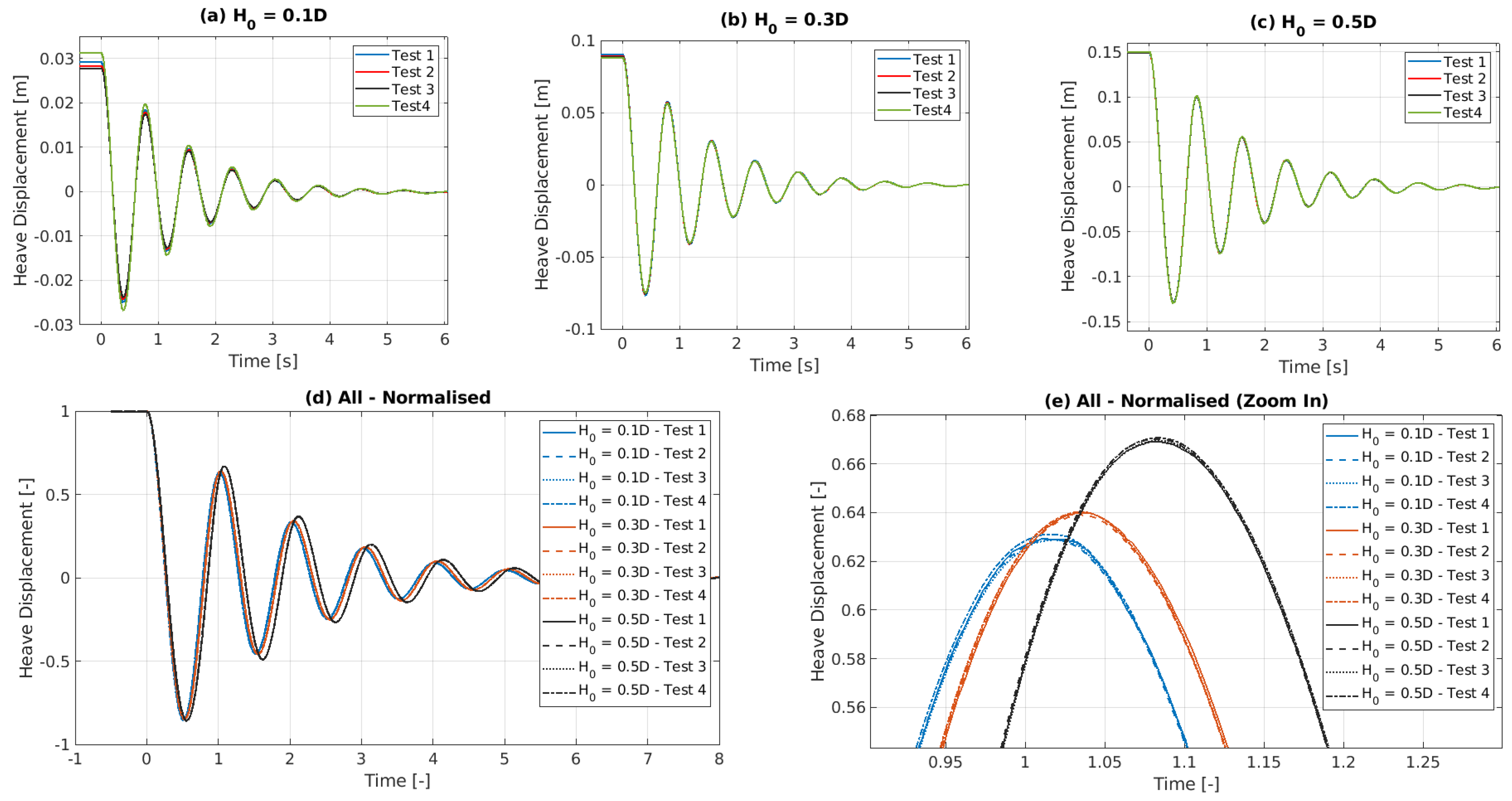

2.2.3. Heave Motion Results

2.2.4. Wave Radiation Results

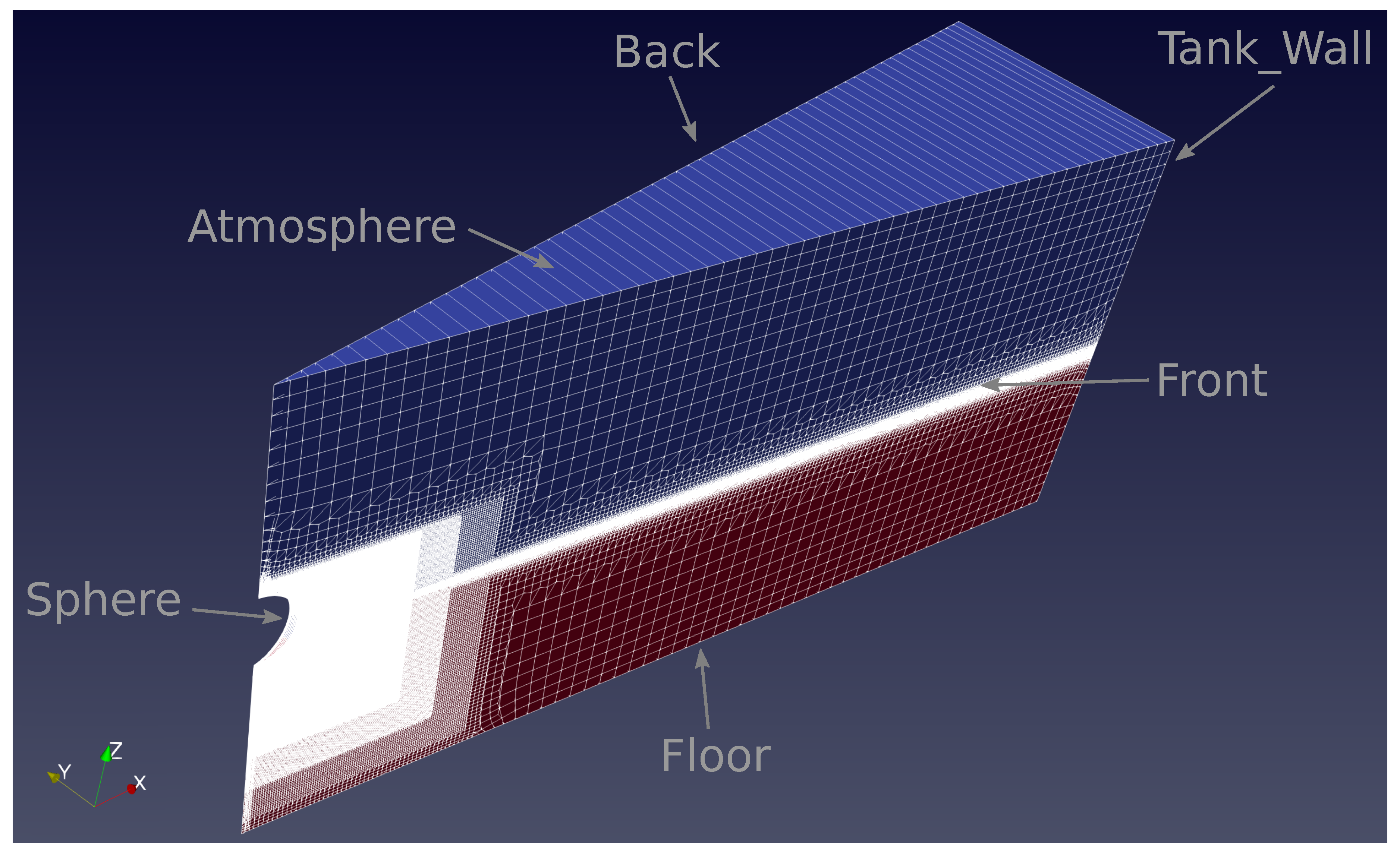

2.3. Description of the Axisymmetric Numerical Wave Tank

2.3.1. Implementation

2.3.2. Differences to the RANS5 model

- Objective: The primary objective of the present A-NWT is to accurately capture both the heave motion of the sphere and the radiated wave field. In contrast, the RANS5 model focused solely on the sphere’s heave motion. This difference necessitates a more refined meshing strategy, especially around the free surface, and adjustments to various solver parameters to accommodate the additional complexity of wave radiation.

- OpenFoam version: The RANS5 model was implemented using the OpenFOAM v7 (Foundation) version of OpenFOAM, whereas the present study uses the OpenFOAM v2312 (ESI) version.

- Sphere Motion Solver: The RANS5 model employs OpenFOAM’s sixDoFRigidBodyMotion solver, whereas the present study uses OpenFOAM’s rigidBodyMotion solver.

-

Water Depth and Tank Configuration: In the RANS5 model, the water depth was set to 6D to mitigate issues related to mesh deformation and the stability of the heaving sphere simulations. The deeper tank was chosen to avoid mesh compression problems beneath the sphere during large vertical displacements, which could lead to simulation crashes due to poor mesh quality.However, this increased depth was a compromise that potentially neglected the hydrodynamic effects of the tank floor on the sphere’s motion and the radiated wave field. In the current study, the A-NWT has been configured to use a water depth of 3D, matching the physical experiments. Extensive debugging and optimization were performed to stabilize the simulations with this more realistic tank depth, ensuring that the tank floor’s influence on wave radiation is accurately captured.

- Mesh Generation: The RANS5 model used a combination of OpenFOAM mesh generation tools of blockMesh and snappyHexMesh. However, this approach encountered issues in the present study when using the wedge boundary condition. Specifically, the mesh points generated around the sphere did not lie perfectly in a plane, causing conflicts with the axisymmetry requirements of the wedge boundary condition. To address this, the mesh generation was switched to cfMesh, which could ensure that the front face of the mesh maintained perfect alignment with the axisymmetric plane - a critical requirement for the wedge boundary condition and overall simulation accuracy.

3. Results

3.1. Sphere Motion

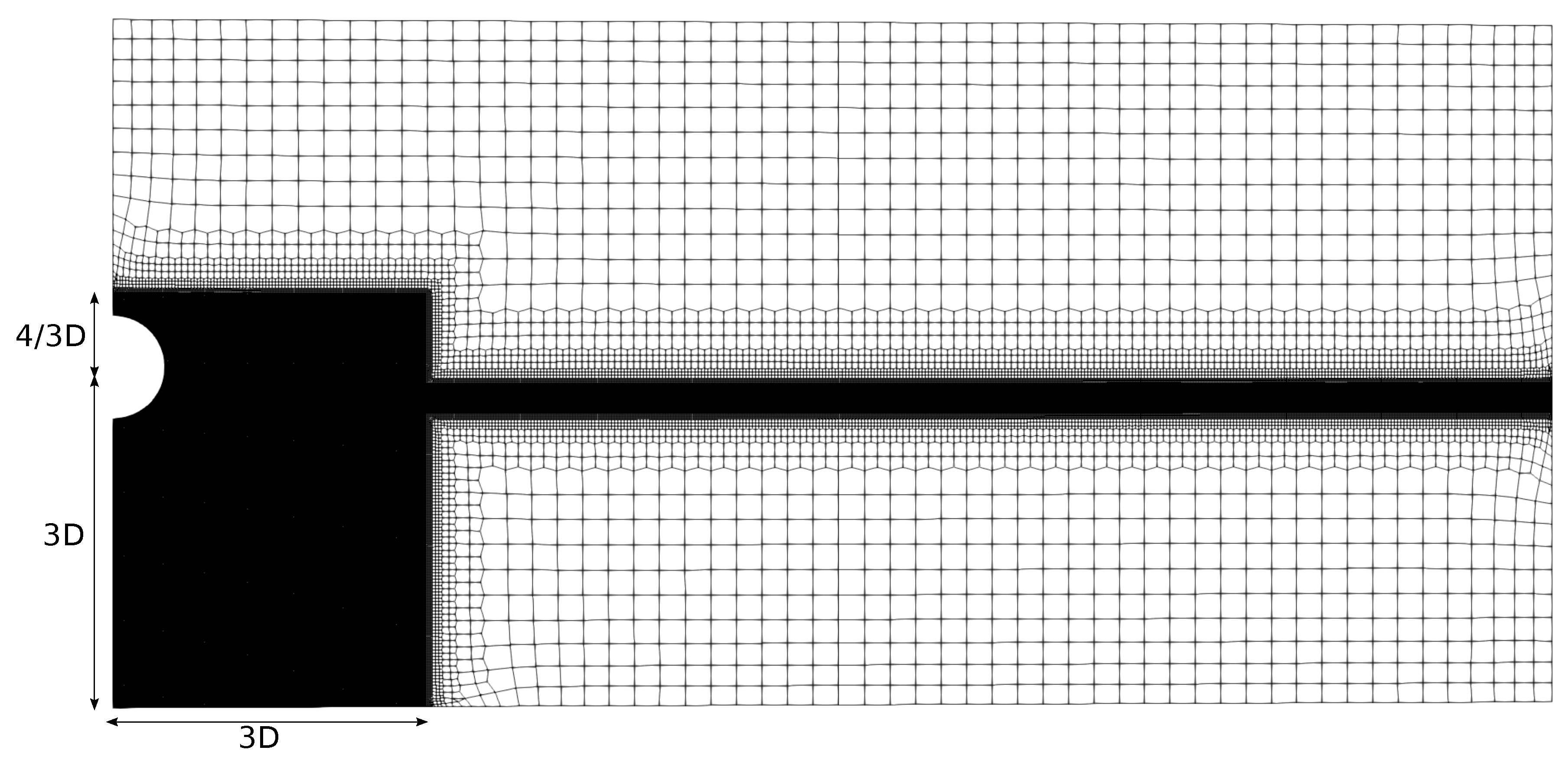

3.1.1. Temporal and Spatial Discretisation

- Time Step

- Adaptive Time Step Method: Based on a maximum Courant number, C, criterion with refinement levels of .

- Fixed Time Step Method: Using fixed time steps of .

- Mesh Setup

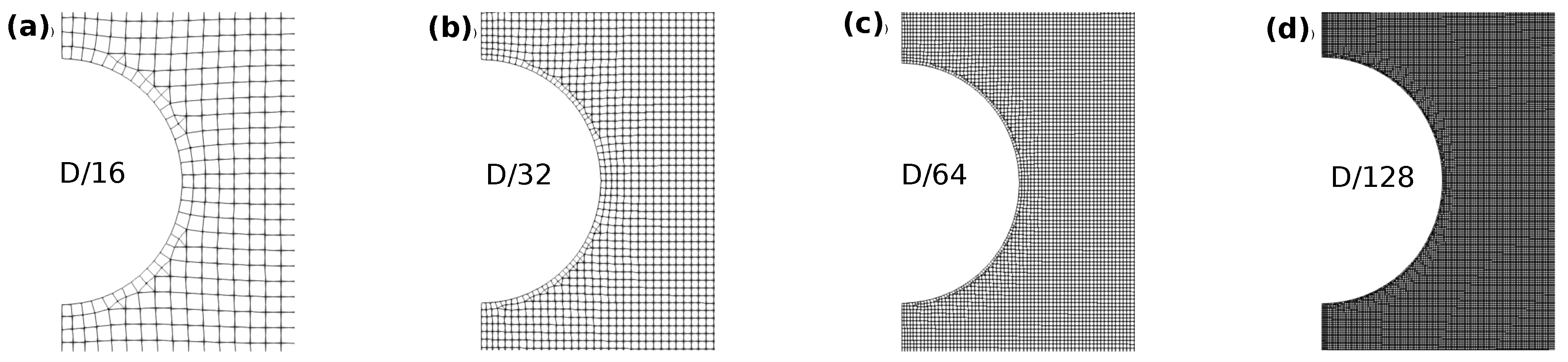

- Mesh Resolutions

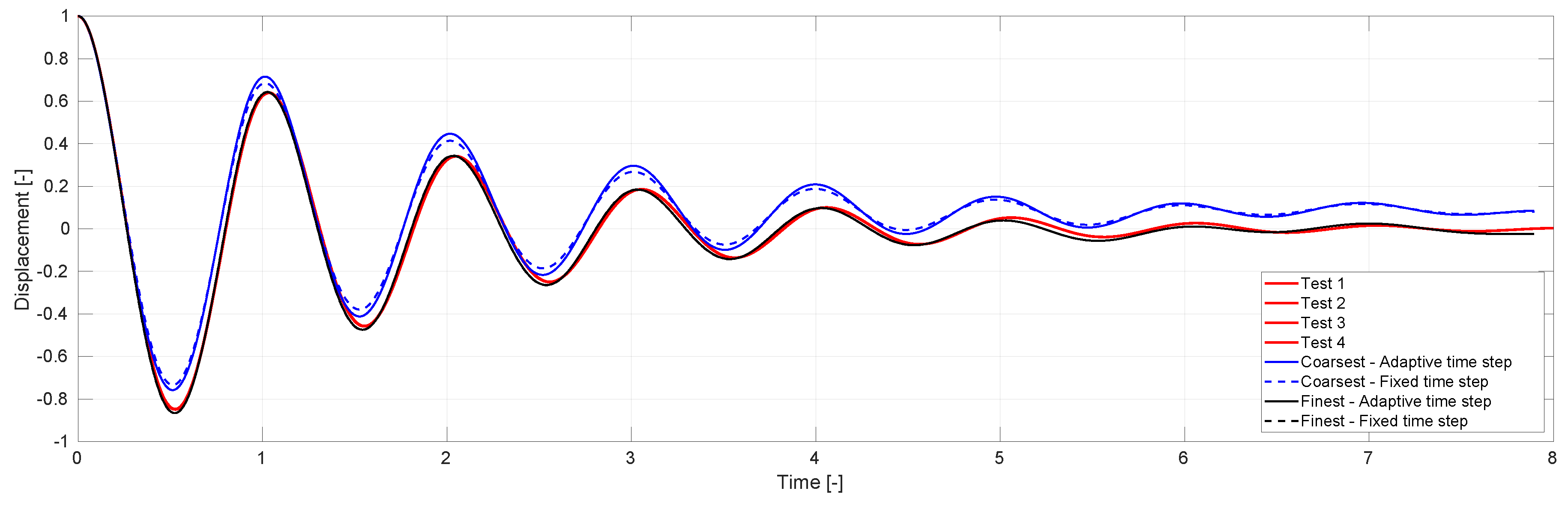

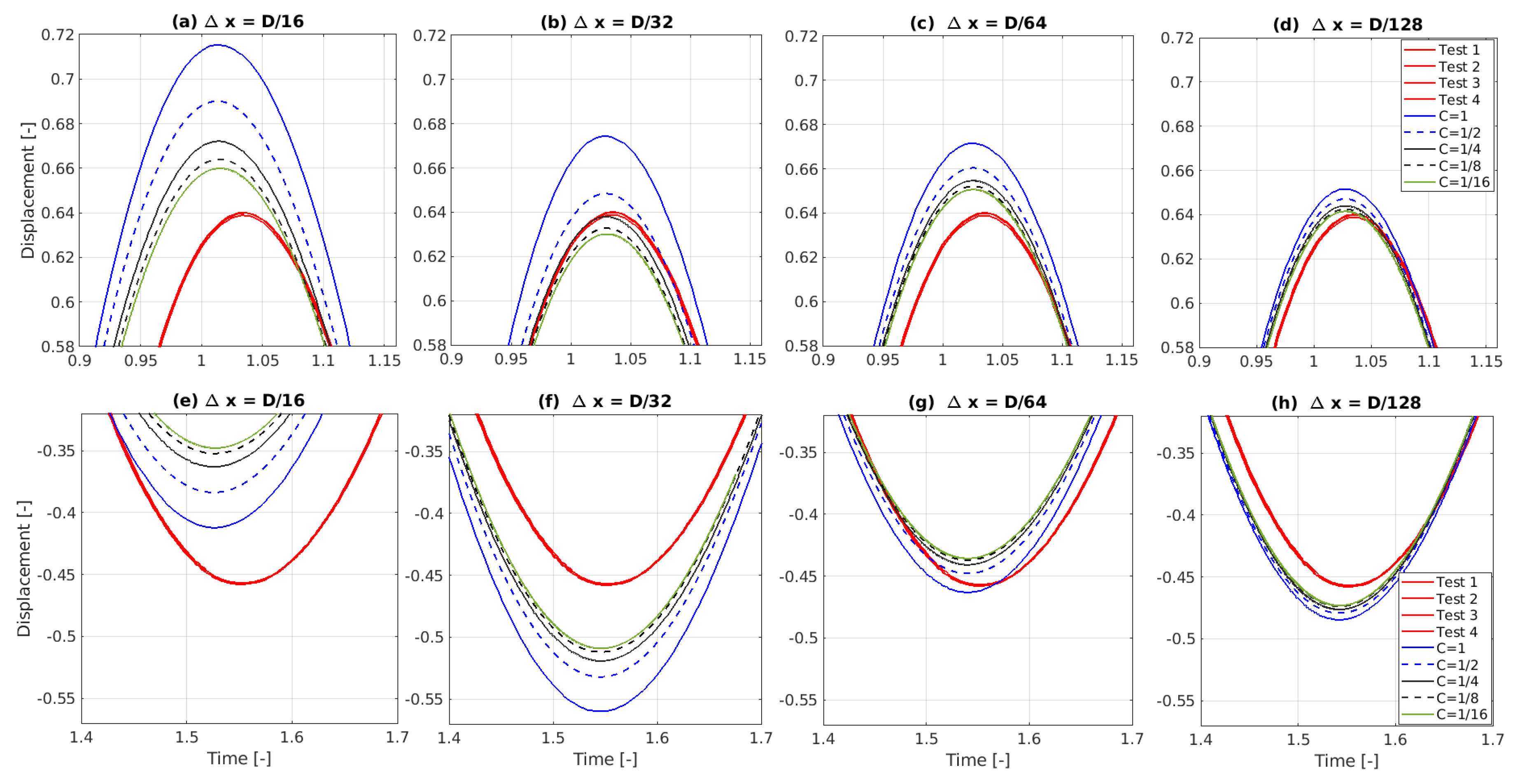

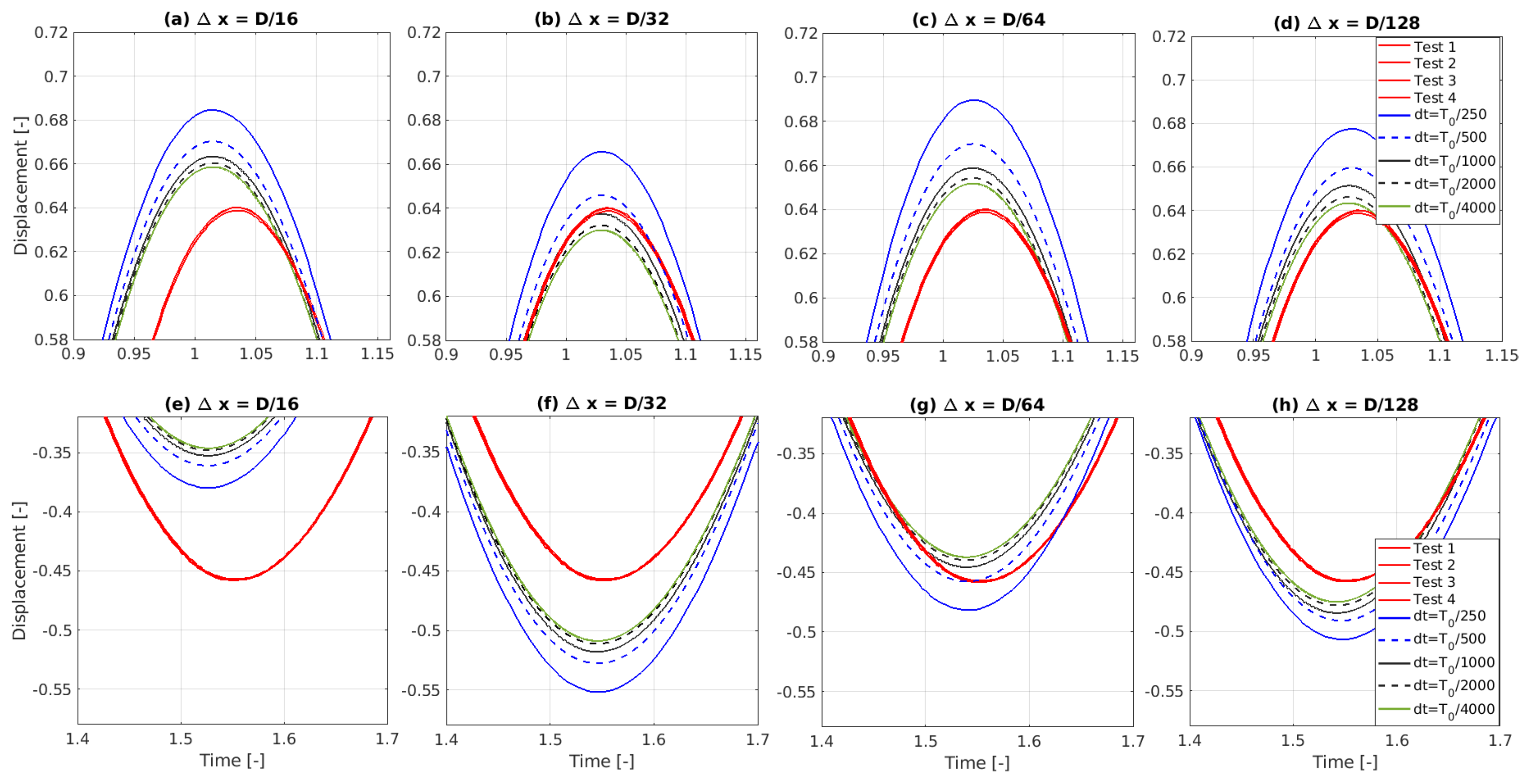

- Results of Parametric Study

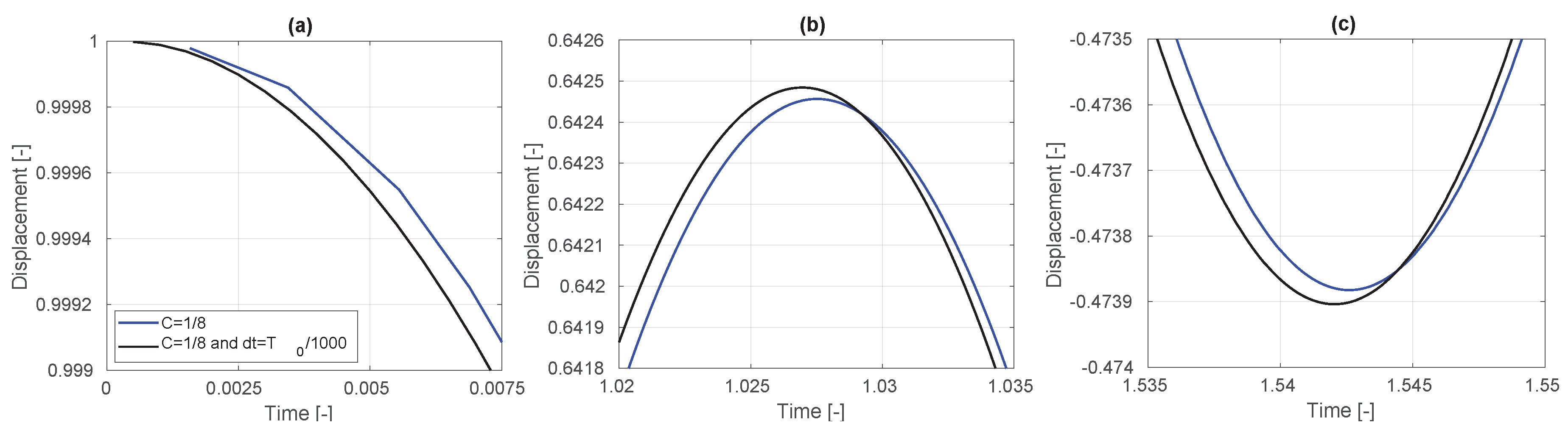

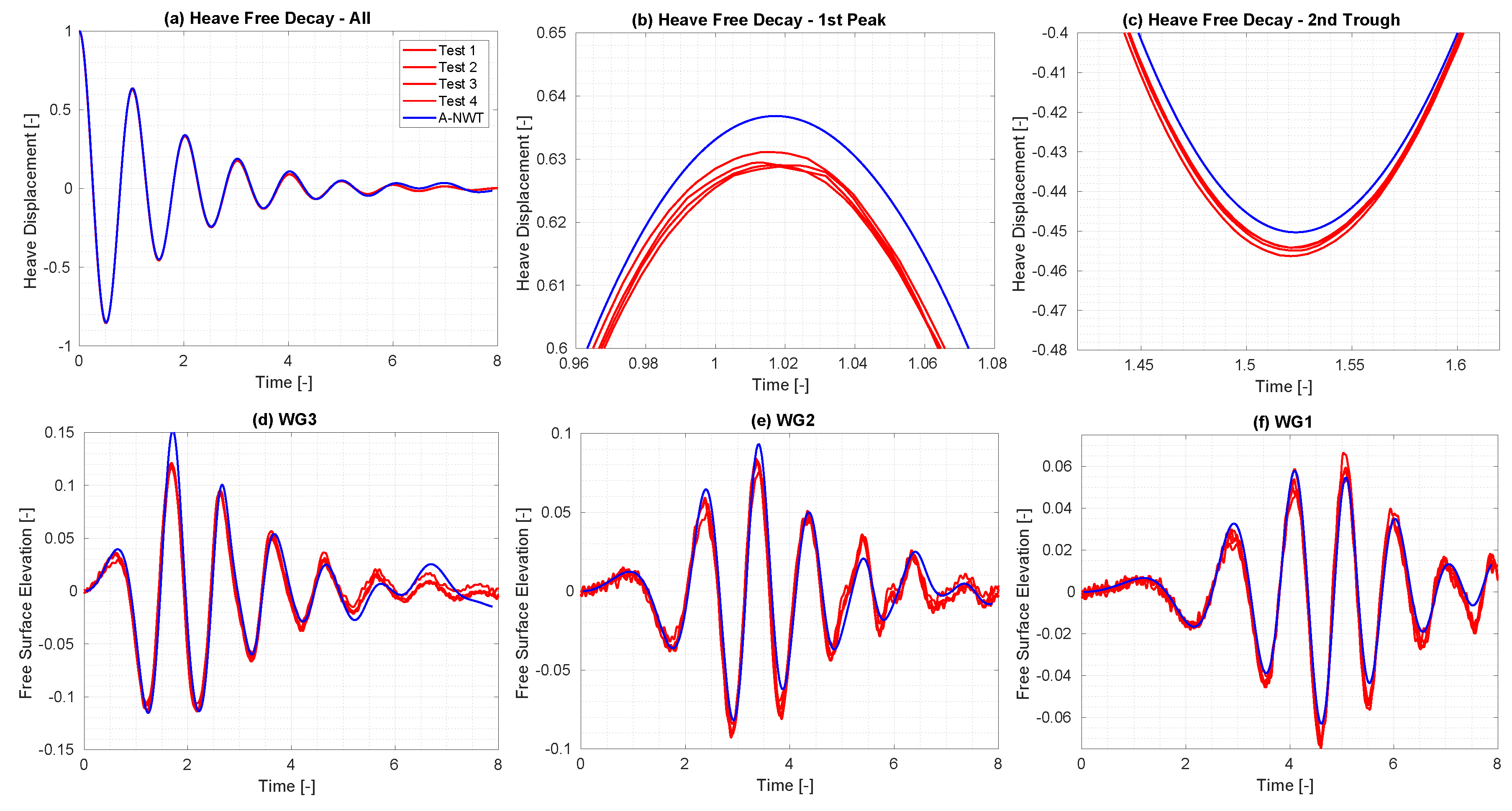

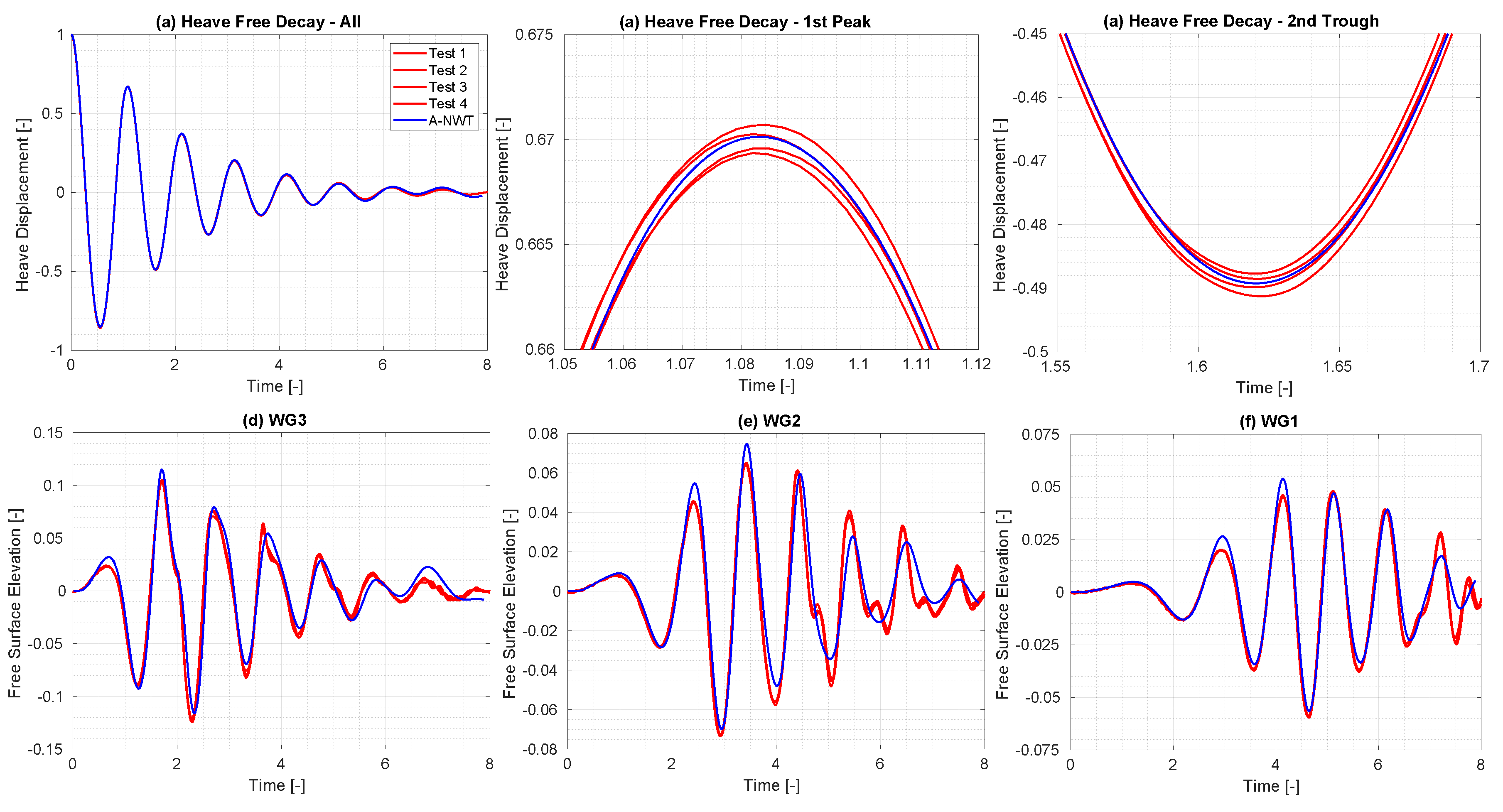

- Temporal Discretisation: The amplitude of the A-NWT results decrease with finer temporal discretisation, converging to a solution for time steps of approximately and .

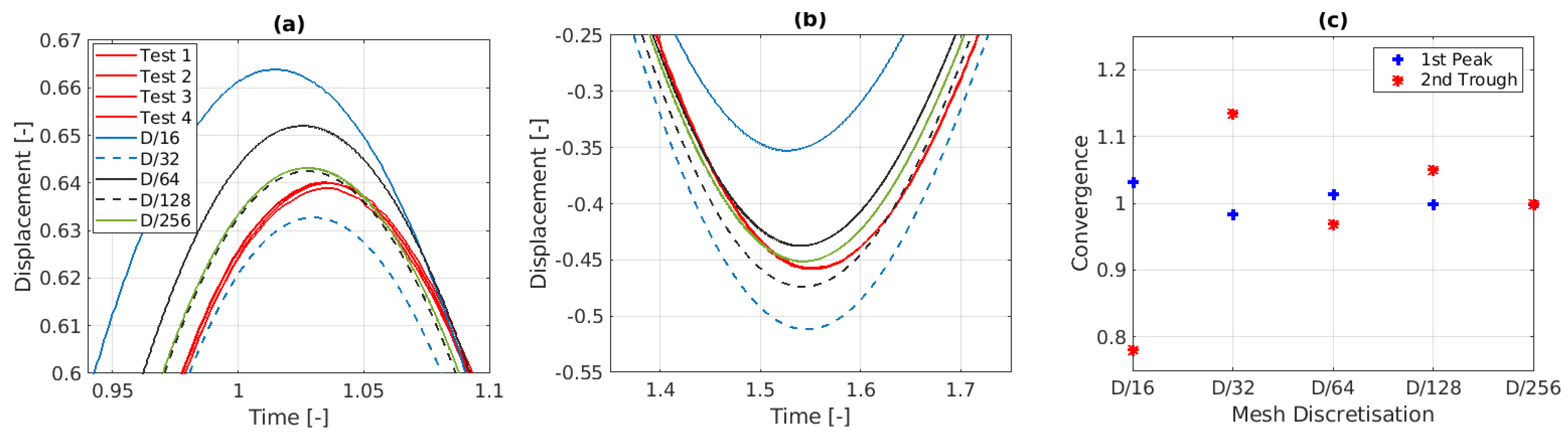

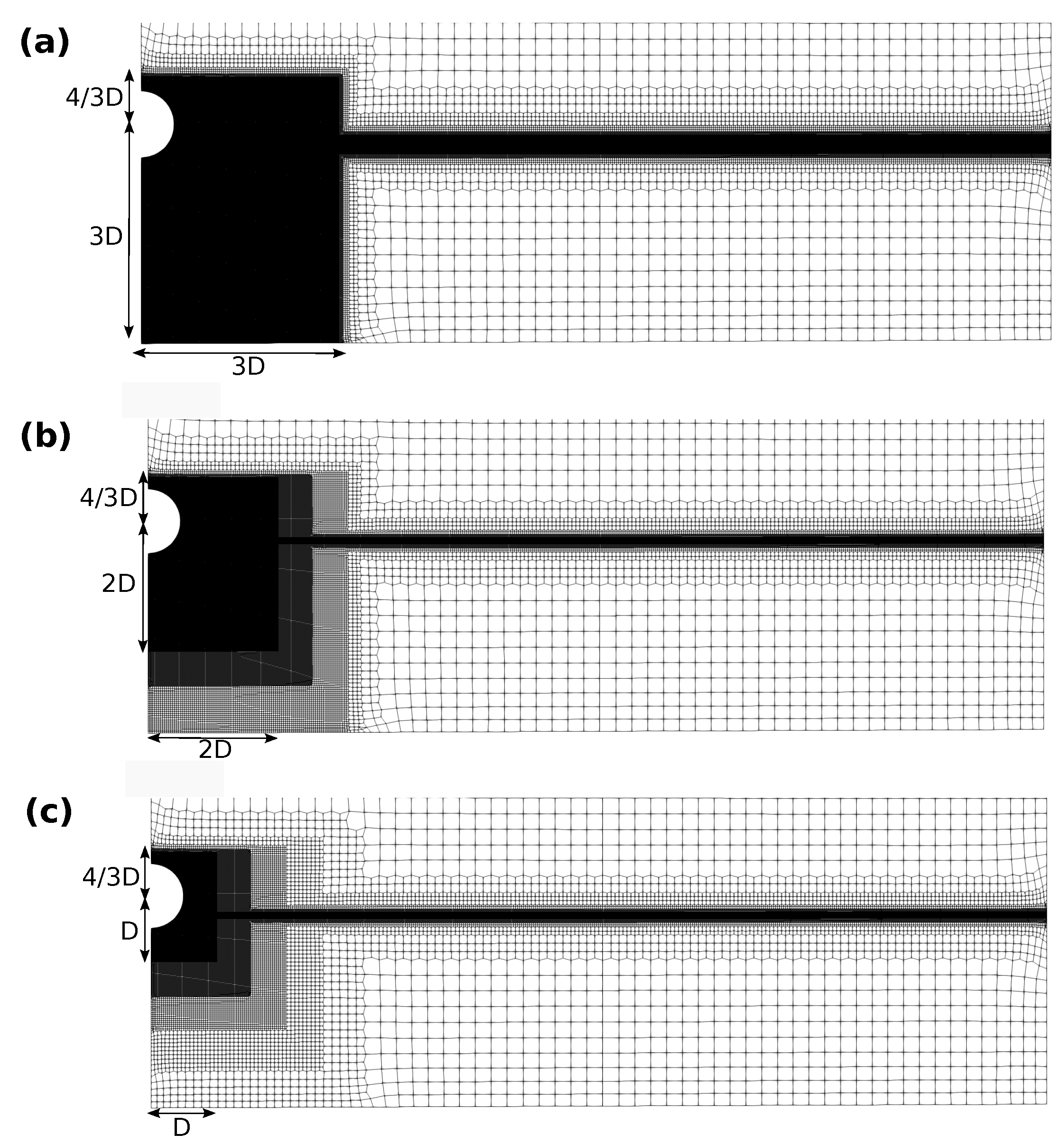

- Spatial Discretisation: The A-NWT results are seen to converge as the mesh cell size is decreased, however the convergence appears oscillatory. The oscillatory convergence is further illustrated in Figure 12, where results for all spatial discretisations (including an additional refinement level of ) are plotted for the same temporal discretisation (). The amplitude of the first peak for the mesh is within 0.15% of the amplitude for the mesh. For the second trough however, the difference is significantly larger, with the amplitude being 5.1% larger for the mesh compared to the mesh.

- Accuracy: The results appear to converge very closely to the experimental results. Both the amplitude and phase of the first peak and second trough appear to converge within 1% of the experimental results. Refinements to the solver settings, later in this Section, will look to further improve this accuracy.

- Selected Discretisation

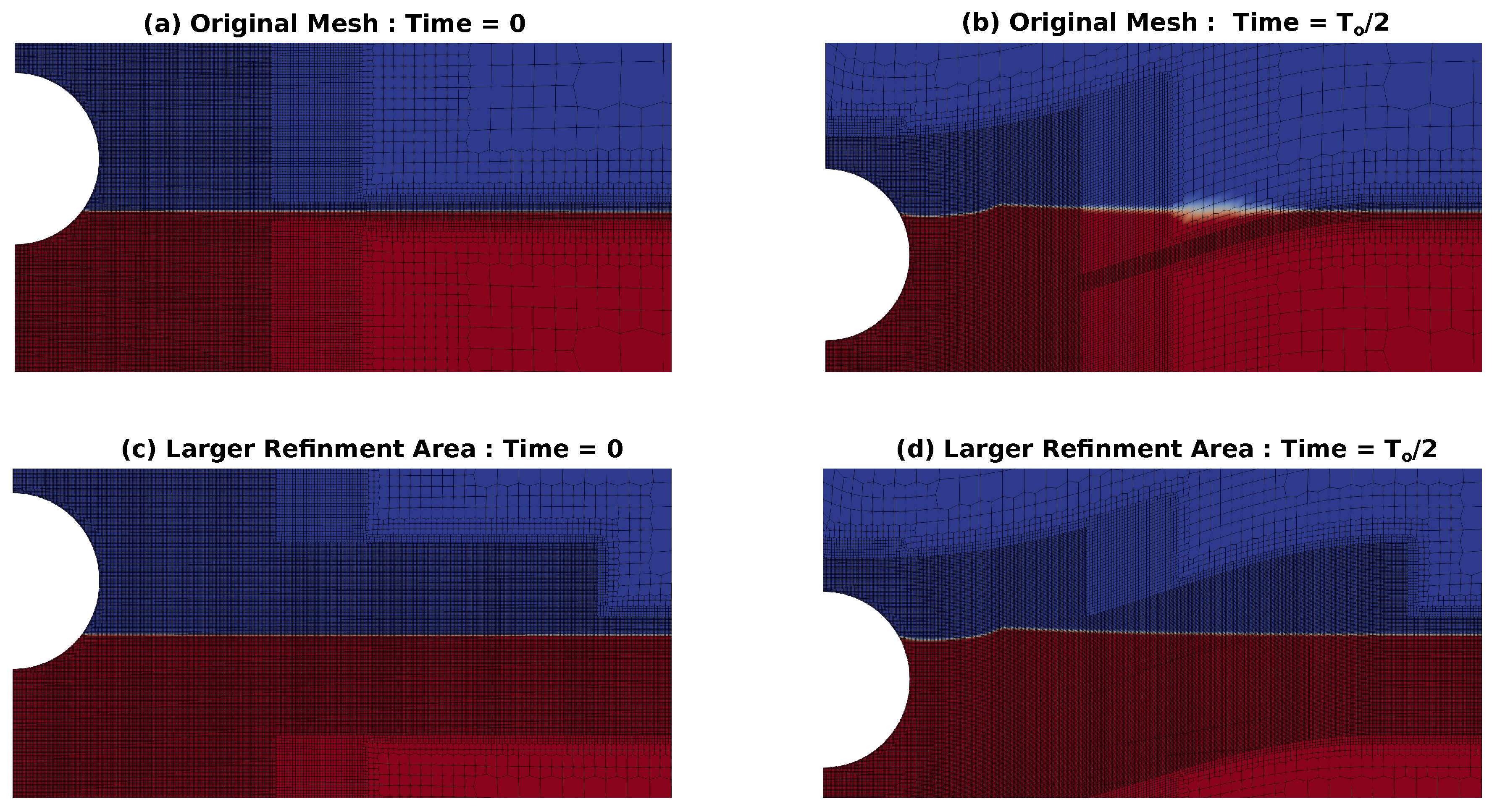

3.1.2. Mesh Refinement Area

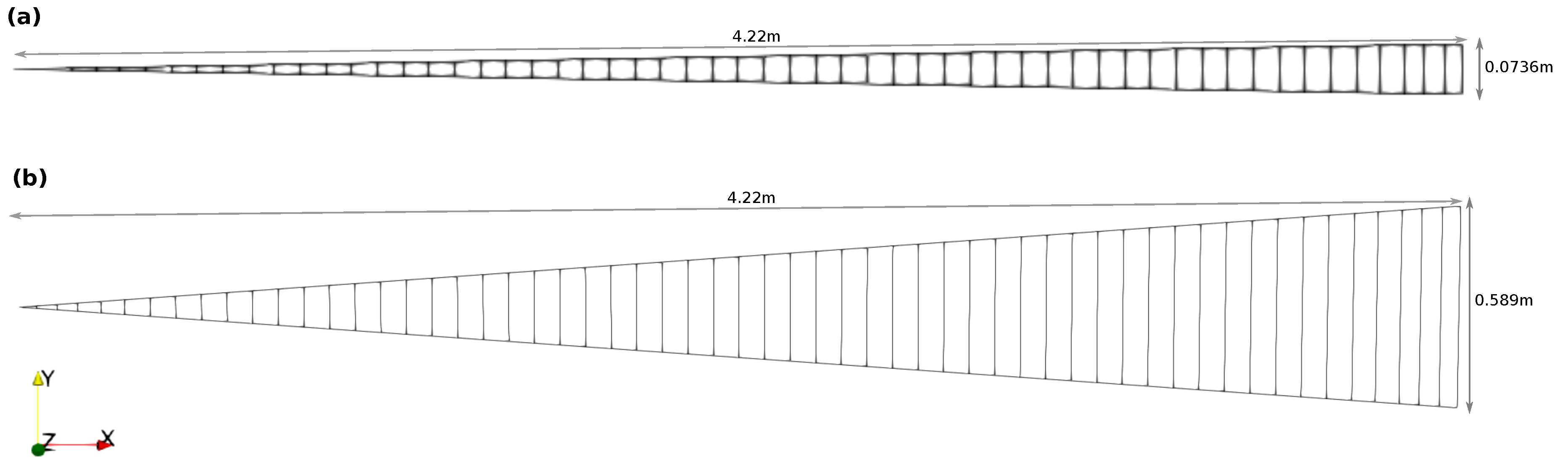

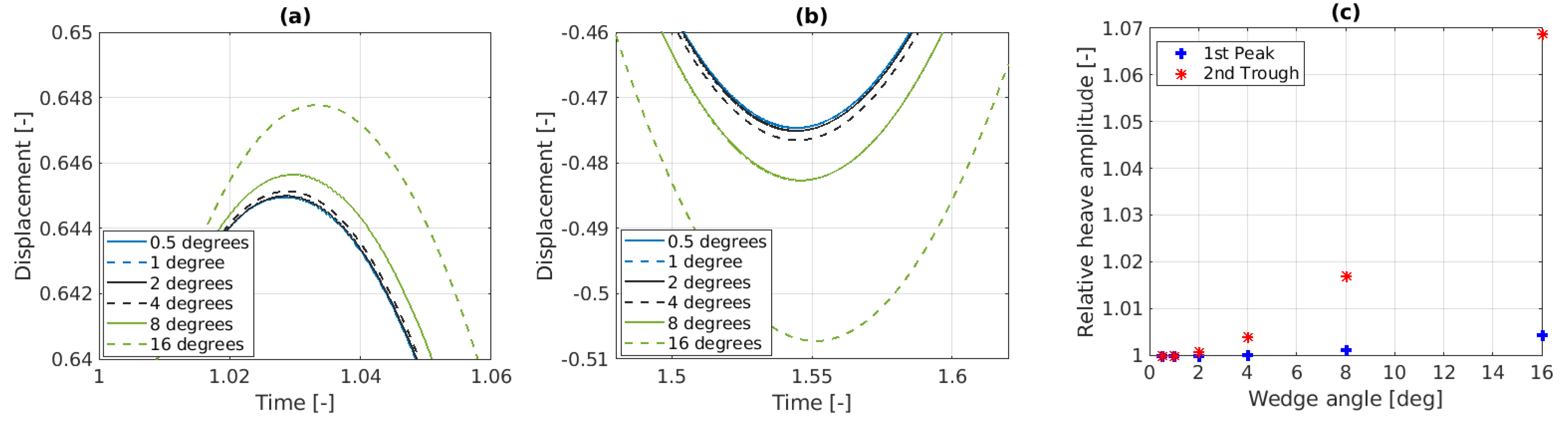

3.1.3. Wedge Angle

3.1.4. Solver Settings

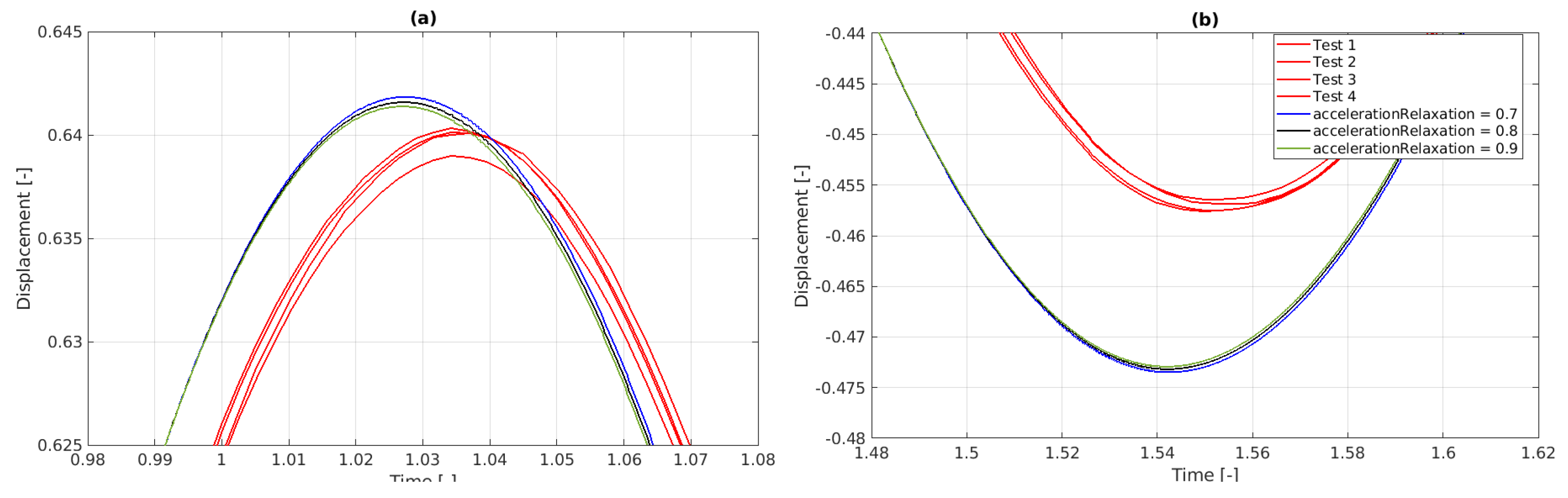

- Acceleration Relaxation

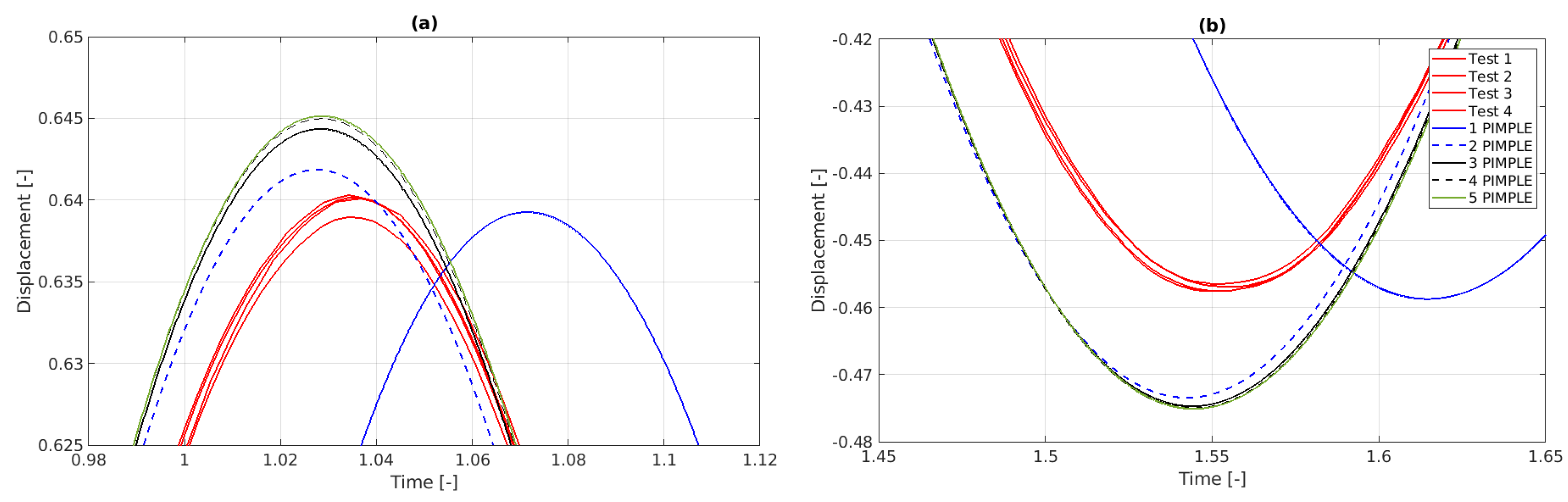

- PIMPLE Iterations

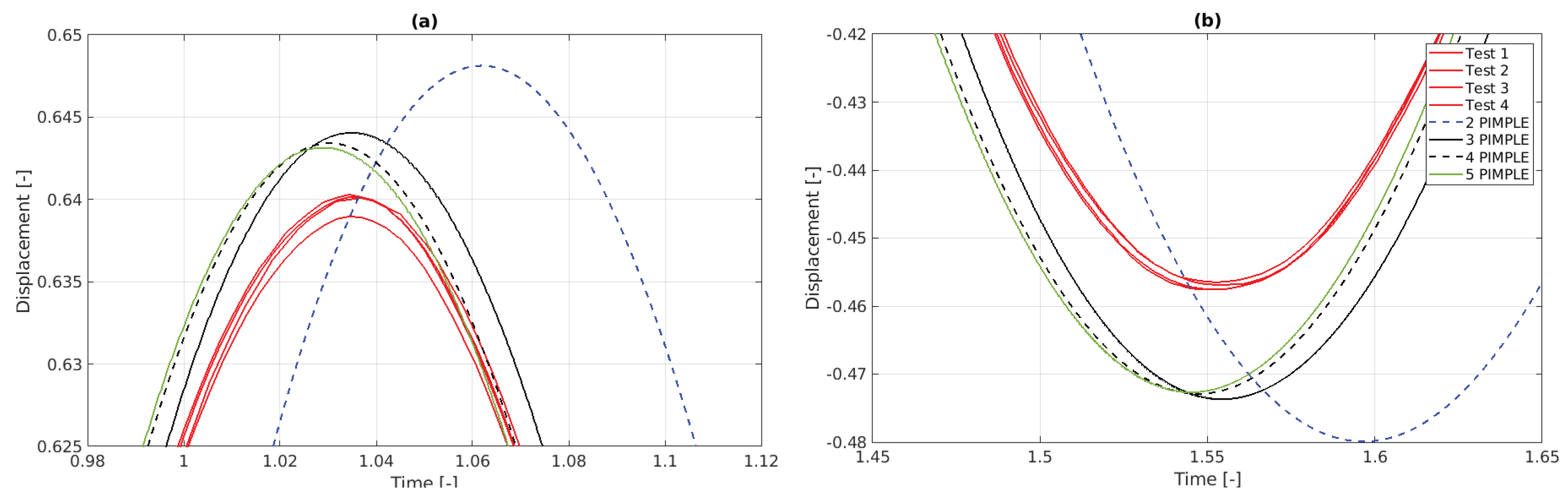

- PIMPLE Iterations + Inner Loop Mesh Motion

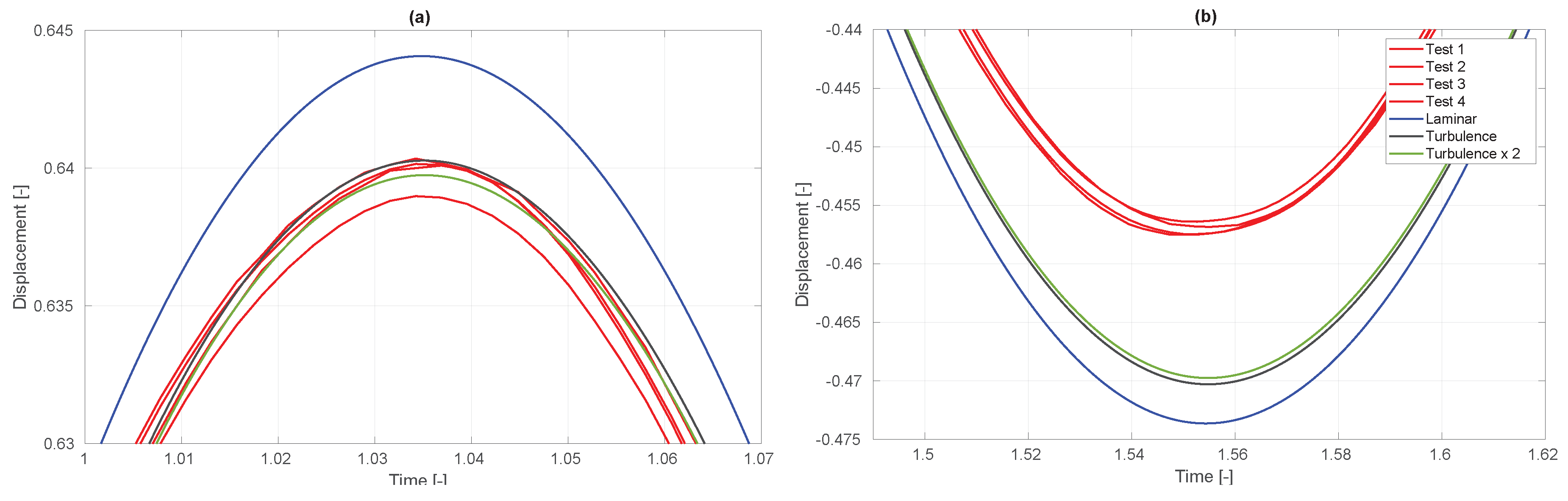

- Turbulence Modelling

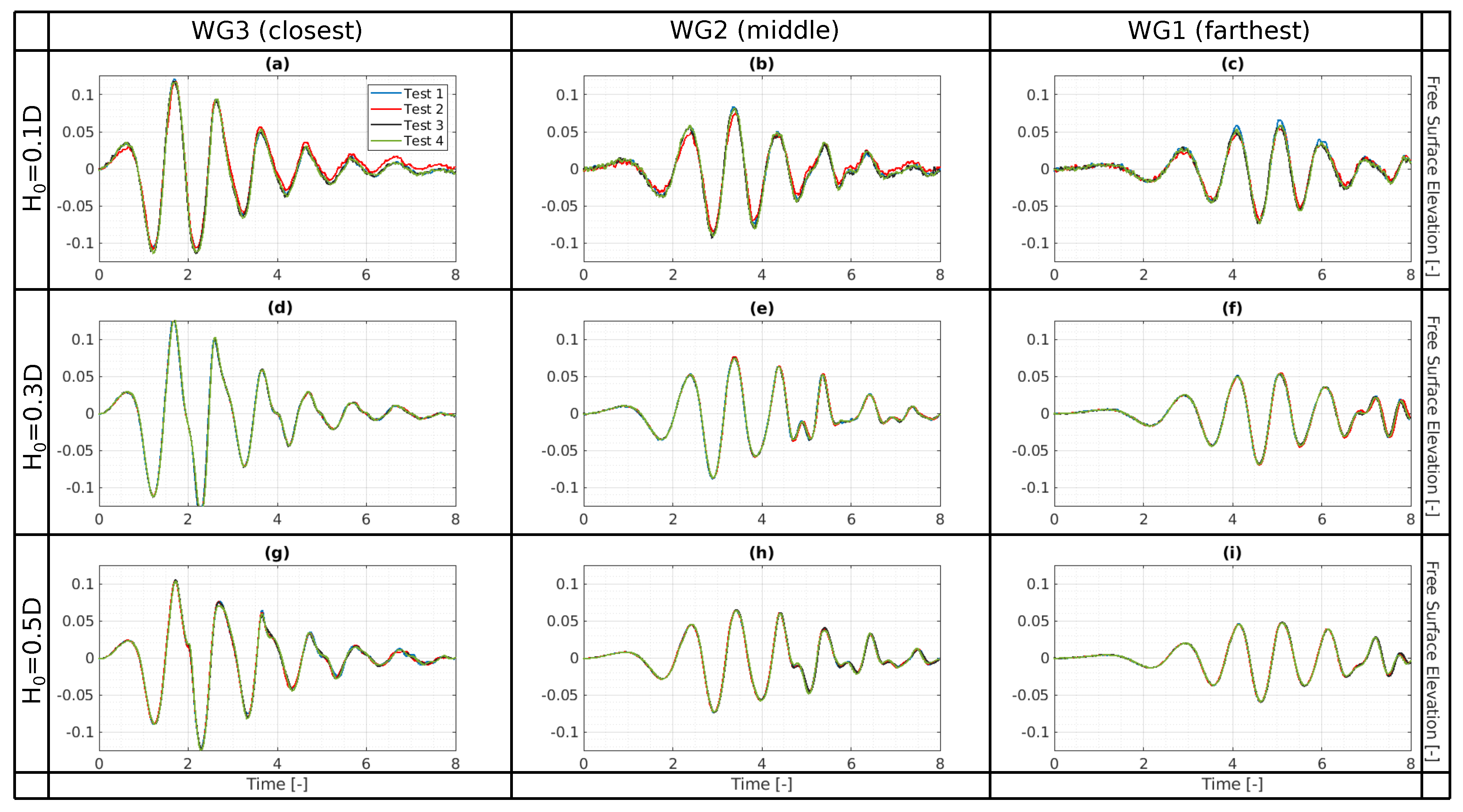

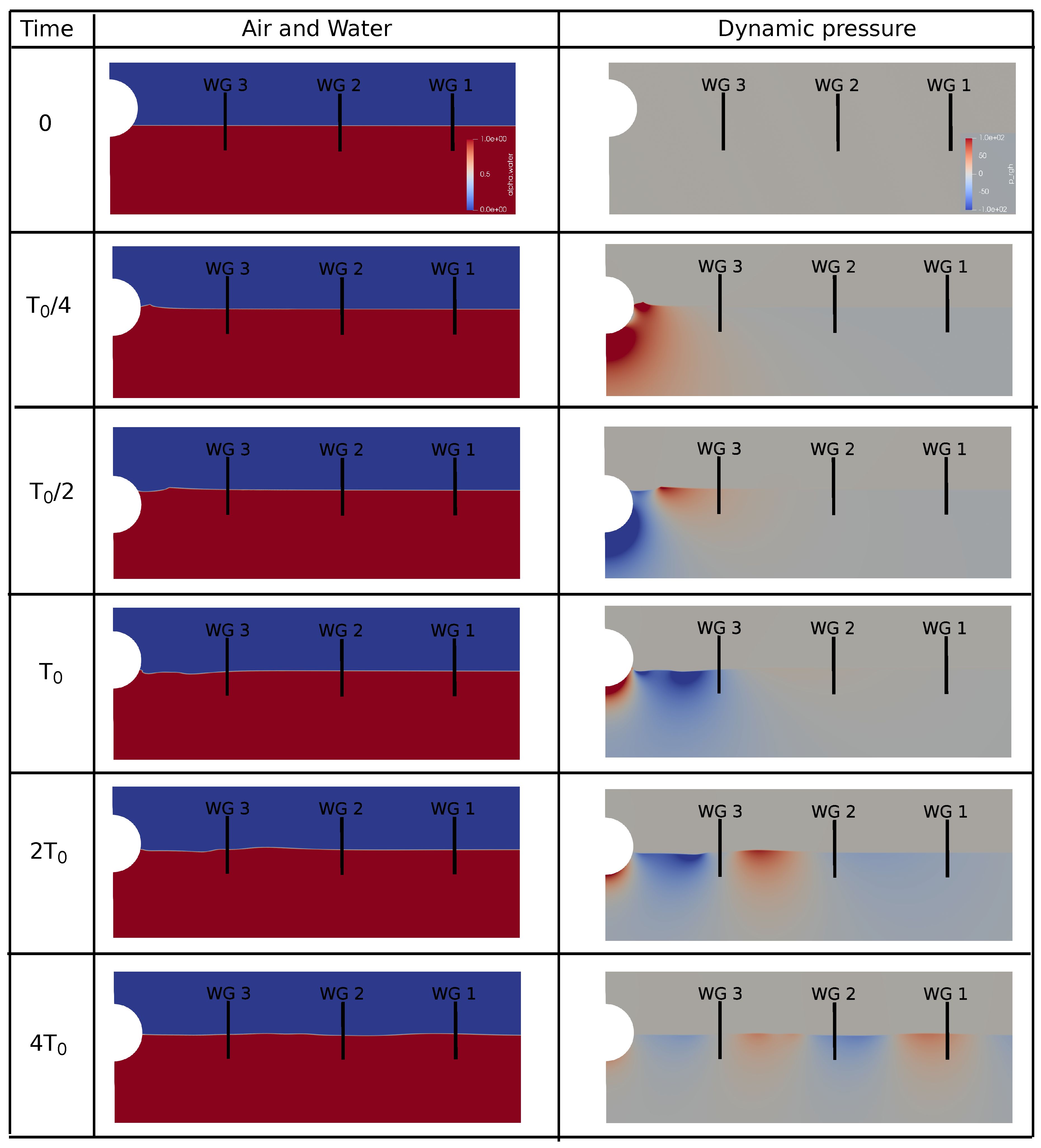

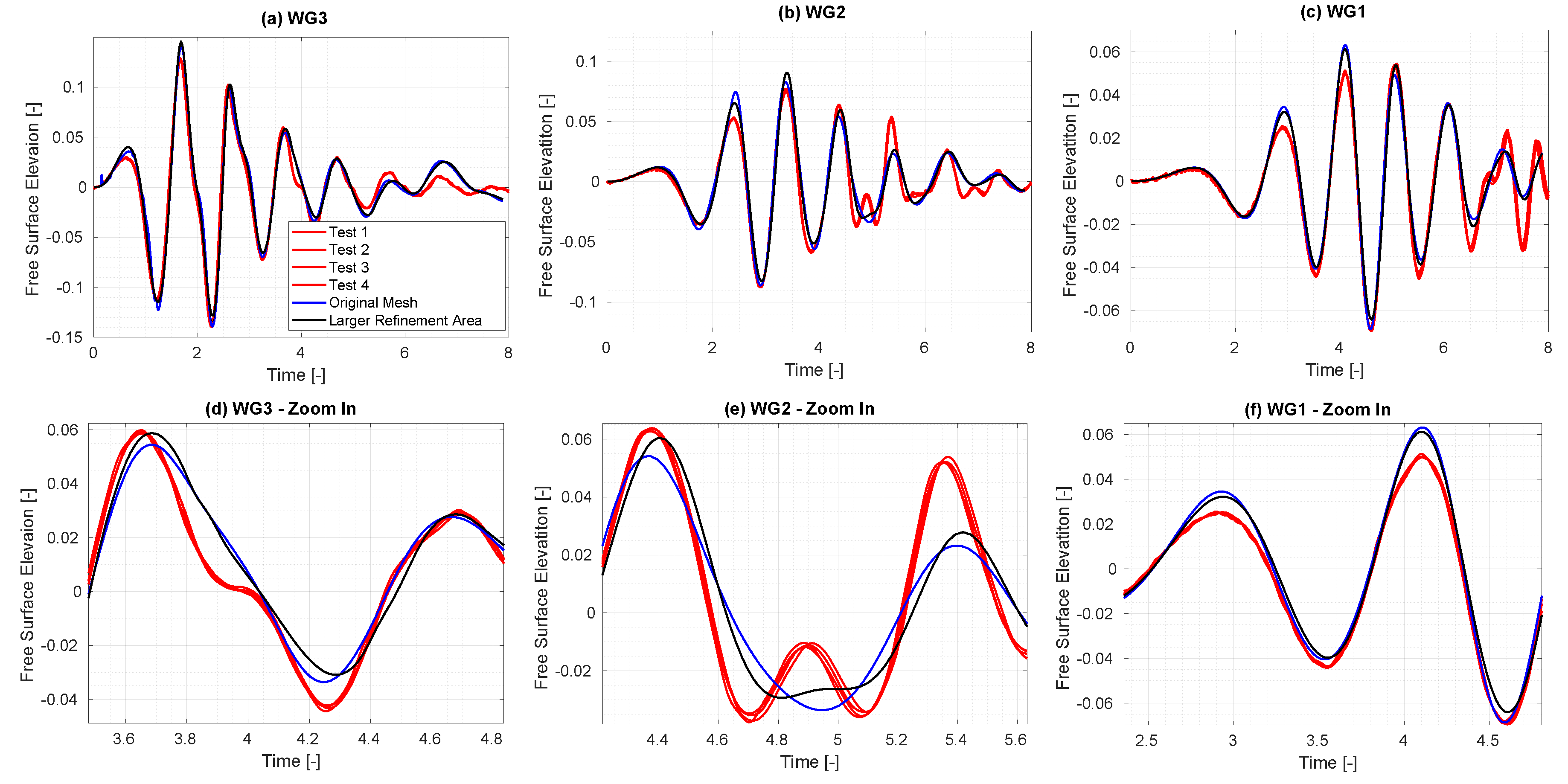

3.2. Radiated Wave

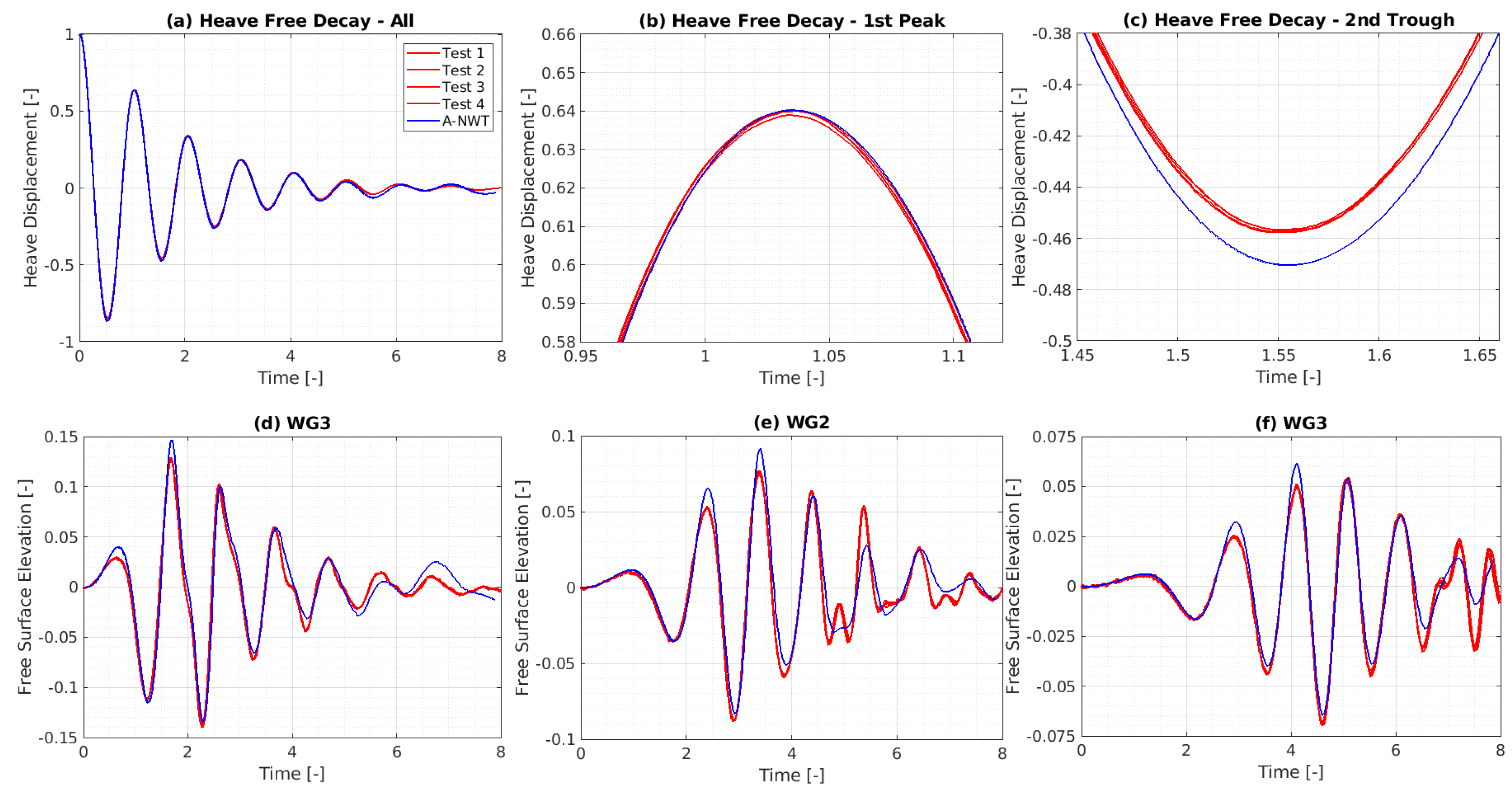

3.3. The A-NWT Results

3.4. Validation Against Other Drop Heights

4. Discussion

4.1. The A-NWT performance

-

Accuracy : The A-NWT results demonstrated excellent accuracy across multiple initial drop heights. For the heave motion, the alignment between A-NWT results and experimental data improved with increasing initial drop height. The A-NWT results for the largest drop height () fell within the range of the four repeated tests in the PWT, showcasing exceptional accuracy. For the middle drop height (), the peaks matched the experimental results well, though the troughs were slightly overpredicted. The smallest drop height () exhibited minor discrepancies for both peaks and troughs.Regarding wave radiation, the A-NWT successfully captured the dominant trend of the free surface elevation at the three different wave gauge locations. However, a second harmonic component, evident in the experimental results, was not as pronounced in the A-NWT simulations. Additionally, discrepancies increased towards the end of the signals, likely due to the breakdown of axisymmetry in the PWT as the earliest radiated waves reflected off the tank walls and returned to the wave gauges.

- Computational Expense : The A-NWT’s computational efficiency is a significant advantage. The final A-NWT mesh comprised approximately 150,000 cells, and simulation runtimes were manageable even on modest computational resources. Running the A-NWT simulations on 24 cores required 10.7 [h], on 12 cores 16.7 [h] and on 6 cores 25.8 [h]. To estimate the computational expense when moving to a three-dimensional simulation, the plot in Figure 18(c) offers some insight where the results appear to begin diverging between 2 - 4°2. Angularly discretising 360° by such sized wedges requires between 90 - 180 cells in the third dimension, thus the total cell count for the three dimensional NWT could be around 15M. To run a simulation within a day, would require a HPC with more than 600 cores3.

4.2. Initial Time Steps

4.3. Future Studies

- Mesh Optimisation – Further studies can work to reduce the required number of mesh cells whilst retaining the accuracy of the results. Increasing the aspect ratio of cells in certain regions, to increase/decrease the spatial discretisation resolution more in one direction without also increasing in the other direction, might be of interest.

- Time-Step Refinement – While the chosen time step of was found to be effective, it was selected based on a trial with a discretization level of 2. Future work could explore intermediate values between and , potentially identifying an optimal balance that allows for even larger time steps without compromising accuracy.

- Overset Mesh - Compare performance of the current mesh morphing with the overset method. While the mesh morphing is seen to work well in heave, for other degrees of freedom, in particular pitch, roll and yaw, the mesh morphing gets twisted and simulations crash [38]. For these cases, the overset approach is necessary within OpenFOAM, therefore it would be of interest to understand how well it performs, in terms of accuracy and simulation time, compared to the mesh morphing method.

- Wave Radiation - Further investigation to improve the simulation of the wave radiation, in order to replicate the smaller initial peak values and and the emergence of a second harmonic observed in experimental data. Future studies could benefit from analyzing wave radiation in the frequency domain, allowing for a more detailed comparison and understanding of these phenomena.

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A-NWT | Axisymmetric Numerical Wave Tank |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| D | Diameter of Sphere |

| NWT | Numerical Wave Tank |

| PWT | Physical Wave Tank |

| RANS | Reynolds Averaged Navier Stokes |

| WEC | Wave Energy Converter |

| 1 | Default refers to the parameter values used in the interFoam tutorial cases: DTCHull, DTCHullMoving and motorBike, included in the OpenFOAM version 2306 release, that employ the SST model. |

| 2 | It should be noted that the mesh cells comprise straight lines only. Capturing the curvature of the radial faces with a spline instead may alter this result. |

| 3 | Running the simulation on 6 cores took approximately 24 hours, with 25k cells peer core. Therefore, parallelising the 15M cells to 25k cells per core would require 600 cores |

References

- Ortloff, C.; Krafft, M. Numerical Test Tank: Simulation of Ocean Engineering Problems by Computational Fluid Dynamics. Offshore Technology Conference. OTC, 1997, pp. OTC–8269.

- Kim, C.; Clement, A.; Tanizawa, K. Recent research and development of numerical wave tanks-a review. International Journal of Offshore and Polar Engineering 1999, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, F.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Sadat-Hosseini, H.; Mousaviraad, M.; Bhushan, S.; Diez, M.; Sung-Hwan, Y.; Wu, P.C.; Yeon, S.M.; others. Recent progress in CFD for naval architecture and ocean engineering. Journal of Hydrodynamics 2015, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Windt, C.; Davidson, J.; Ringwood, J.V. High-fidelity numerical modelling of ocean wave energy systems: A review of computational fluid dynamics-based numerical wave tanks. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 93, 610–630. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Xue, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wan, D. A review of high-fidelity computational fluid dynamics for floating offshore wind turbines. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, 10, 1357. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Calderon-Sanchez, J.; Duque, D.; Souto-Iglesias, A. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) applications in Floating Offshore Wind Turbine (FOWT) dynamics: A review. Applied Ocean Research 2024, 150, 104075. [Google Scholar]

- Draycott, S.; Davey, T.; Ingram, D.; Day, A.; Johanning, L. The SPAIR method: Isolating incident and reflected directional wave spectra in multidirectional wave basins. Coastal Engineering 2016, 114, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windt, C.; Untrau, A.; Davidson, J.; Ransley, E.J.; Greaves, D.M.; Ringwood, J.V. Assessing the validity of regular wave theory in a short physical wave flume using particle image velocimetry. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 2021, 121, 110276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windt, C.; Davidson, J.; Schmitt, P.; Ringwood, J.V. On the assessment of numerical wave makers in CFD simulations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar]

- van Essen, S.; Scharnke, J.; Bunnik, T.; Düz, B.; Bandringa, H.; Hallmann, R.; Helder, J. Linking experimental and numerical wave modelling. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2020, 8, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, P.; Doherty, K.; Clabby, D.; Whittaker, T. The opportunities and limitations of using CFD in the development of wave energy converters. Marine & Offshore Renewable Energy 2012, pp. 89–97.

- Kim, J.W.; Jang, H.; Baquet, A.; O’Sullivan, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, B.; Read, A.; Jasak, H. Technical and economic readiness review of CFD-based numerical wave basin for offshore floater design. Offshore Technology Conference. OTC, 2016, p. D011S014R002.

- Davidson, J.; Costello, R. Efficient nonlinear hydrodynamic models for wave energy converter design—A scoping study. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2020, 8, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Ferziger, J.H.; Perić, M.; Street, R.L. Computational methods for fluid dynamics; springer, 2019.

- Miquel, A.M.; Kamath, A.; Alagan Chella, M.; Archetti, R.; Bihs, H. Analysis of different methods for wave generation and absorption in a CFD-based numerical wave tank. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2018, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.M.M.; Lopes, A.M.G.; Ferreira, A.D. Numerical simulation of regular waves: Optimization of a numerical wave tank. Ocean Engineering 2018, 170, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.E.; Fuhrman, D.R.; Roenby, J. Performance of interFoam on the simulation of progressive waves. Coastal Engineering Journal 2019, 61, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bouscasse, B.; Ducrozet, G.; Gentaz, L.; Le Touzé, D.; Ferrant, P. Spectral wave explicit navier-stokes equations for wave-structure interactions using two-phase computational fluid dynamics solvers. Ocean Engineering 2021, 221, 108513. [Google Scholar]

- Windt, C.; Davidson, J.; Ringwood, J.V. Numerical analysis of the hydrodynamic scaling effects for the Wavestar wave energy converter. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2021, 105, 103328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, H.C.; Koop, A.; Vaz, G. Verification and validation of CFD simulations for semi-submersible floating offshore wind turbine under pitch free-decay motion. Ocean Engineering 2021, 242, 109993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, B.; Lara, J.L.; Barajas, G.; Losada, Í.J. Wave and structure interaction using multi-domain couplings for Navier-Stokes solvers in OpenFOAM®. Part I: Implementation and validation. Coastal Engineering 2021, 164, 103799. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo, B.; Lara, J.L.; Barajas, G.; Losada, I.J. Waves and structure interaction using multi-domain couplings for Navier-Stokes solvers in OpenFOAM®. Part II: Validation and application to complex cases. Coastal Engineering 2021, 164, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.B.; Andersen, J.; Thomas, S.; Bendixen, F.B.; Bingham, H.; Read, R.; Holk, N.; Ransley, E.; Brown, S.; Yu, Y.H.; others. Highly accurate experimental heave decay tests with a floating sphere: A public benchmark dataset for model validation of fluid–structure interaction. Energies 2021, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskilsson, C.; Shiri, A.; Katsidoniotakis, E. Solution verification of WECs: comparison of methods to estimate numerical uncertainties in the OES wave energy modelling task. Proceedings of the 15th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Bilbao, Spain, 2023.

- Palm, J.; Eskilsson, C. Verification and validation of MoodyMarine: A free simulation tool for modelling moored MRE devices. Proceedings of the 15th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Bilbao, Spain, 2023.

- Eskilsson, C.; Pashami, S.; Holst, A.; Palm, J. Hierarchical approaches to train recurrent neural networks for wave-body interaction problems. ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference. ISOPE, 2023, pp. ISOPE–I.

- Eskilsson, C.; Pashami, S.; Holst, A.; Palm, J. A hybrid linear potential flow-machine learning model for enhanced prediction of WEC performance. Proceedings of the European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, 2023, Vol. 15.

- Eskilsson, C.; Pashami, S.; Holst, A.; Palm, J. Estimation of nonlinear forces acting on floating bodies using machine learning. In Advances in the Analysis and Design of Marine Structures; CRC Press, 2023; pp. 63–72.

- Zafeiris, S.; Papadakis, G. An Overset Algorithm for Multiphase Flows using 3D Multiblock Polyhedral Meshes. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2305.17074 2023.

- Bengtsson, M.; Delvret, M. Motion Decay of a Floating Object. Master’s thesis, Chalmers Universtiy of Technology, 2021.

- Colling, J.K.; Jafari Kang, S.; Dehdashti, E.; Husain, S.; Masoud, H.; Parker, G.G. Free-decay heave motion of a spherical buoy. Fluids 2022, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J. Hydrodynamic Modelling of Offshore Renewables: Experimental Benchmark Datasets and Numerical Simulation; PhD Dissertation, Aalborg Universitetsforlag, 2023. [CrossRef]

- IEA. IEA OES Wave Energy Converters Modelling Verification and Validation, 2016. https://www.ocean-energy-systems.org/oes-projects/wave-energy-converters-modelling-verification-and-validation/.

- Andersen, J.; Kramer, M.B. Wave excitation tests on a fixed sphere: Comparison of physical wave basin setups. Proceedings of the European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, 2023, Vol. 15.

- Jasak, H. OpenFOAM: Open source CFD in research and industry. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 2009, 1, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Benites-Munoz, D.; Windt, C.W.; Feichtner, A.; Tavakoli, S.; Davidson, J.; Paredes, R.; Quintuna, T.; Ransley, E.; others. A Review on the Modelling of Wave-Structure Interactions Based on OpenFOAM. OpenFOAM® Journal 2022, 2, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Cathelain, M.; Guillemet, L.; Le Huec, T.; Ringwood, J. Implementation of an openfoam numerical wave tank for wave energy experiments. Proceedings of the 11th European wave and tidal energy conference. European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J.; Karimov, M.; Szelechman, A.; Windt, C.; Ringwood, J. Dynamic mesh motion in OpenFOAM for wave energy converter simulation. 14th OpenFOAM Workshop, 2019, Vol. 740.

- Menter, F.R.; Kuntz, M.; Langtry, R.; Hanjalic, K.; Nagano, Y.; Tummers, M.J. Ten Years of Industrial Experience with the SST Turbulence Model. 4th Internal Symposium on Turbulence, Heat, and Mass Transfer; Begell House,;: New York, 2003; Vol. 4, pp. 625–632. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | D | m | CoG | g | d | ||

| Unit | mm | kg | mm | m/ | mm | kg/ | mm |

| Value | 300 | 7.056 | (0, 0, -34.8) | 9.82 | {30, 90, 150} | 998.2 | 900 |

| Name | Type | alpha.water | point-Displacement | p_rgh | U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Wedge | wedge | wedge | wedge | wedge |

| Back | Wedge | wedge | wedge | wedge | wedge |

| Floor | Stationary Wall | zeroGradient | fixedValue | fixedFlux-Pressure | fixedValue |

| Atmosphere | Inlet/Outlet | inletOutlet | fixedValue | totalPressure | pressureInlet-OutletVelocity |

| Tank_Wall | Stationary Wall | zeroGradient | fixedValue | fixedFlux-Pressure | fixedValue |

| Sphere | Moving Wall | zeroGradient | calculated | fixedFlux-Pressure | movingWall-Velocity |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| D/128 | |

| < and C<1/8 | |

| Mesh Refinement Area | 1.5D + free surface in mesh motion area |

| Wedge Angle | 2° |

| PIMPLE settings | 3 iterations + move mesh on inner loop |

| Turbulence | – default values |

| accelerationRelaxation | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).