Submitted:

30 August 2024

Posted:

03 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Ink Formulation

2.3. Sample Fabrication

2.4. Testing and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

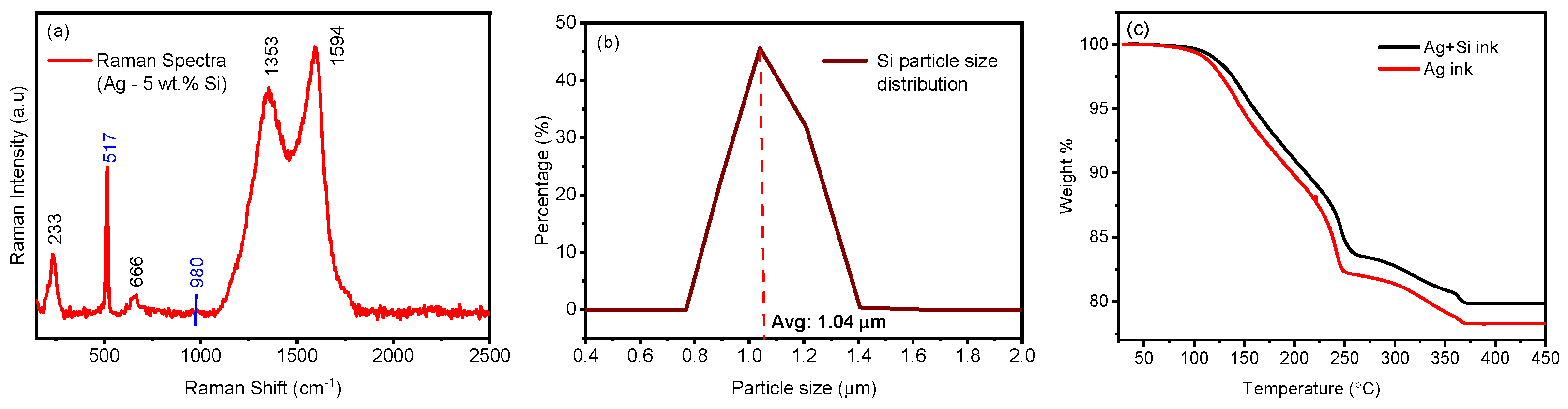

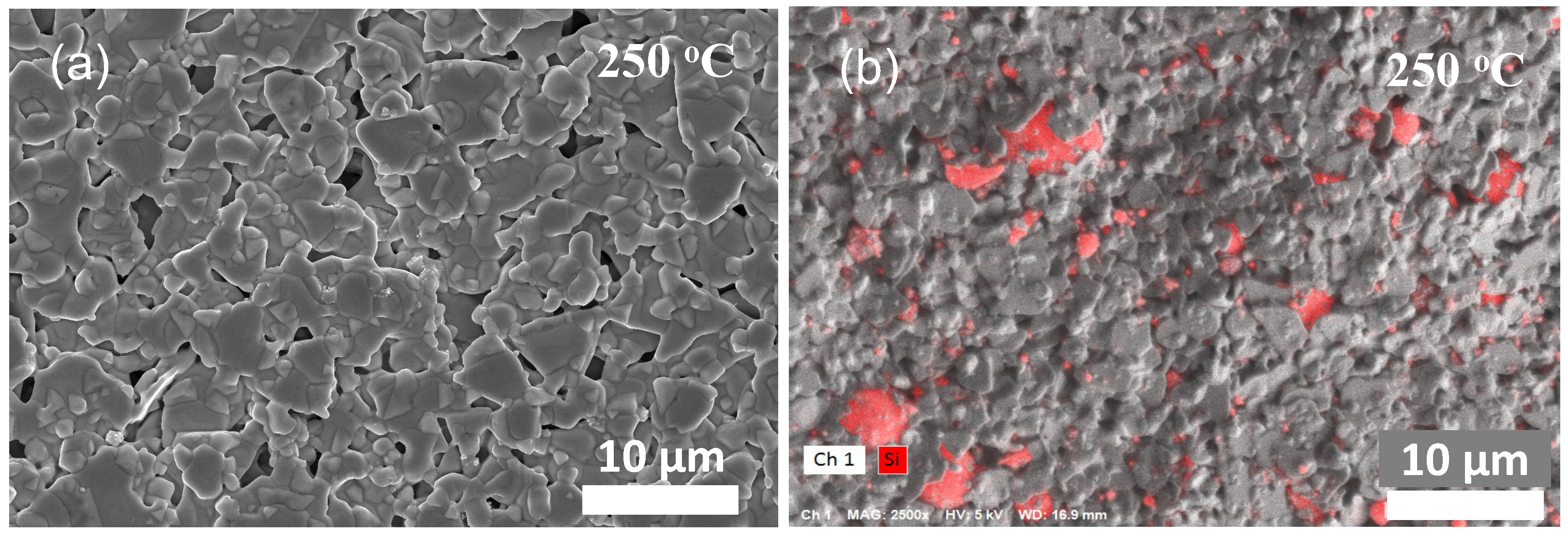

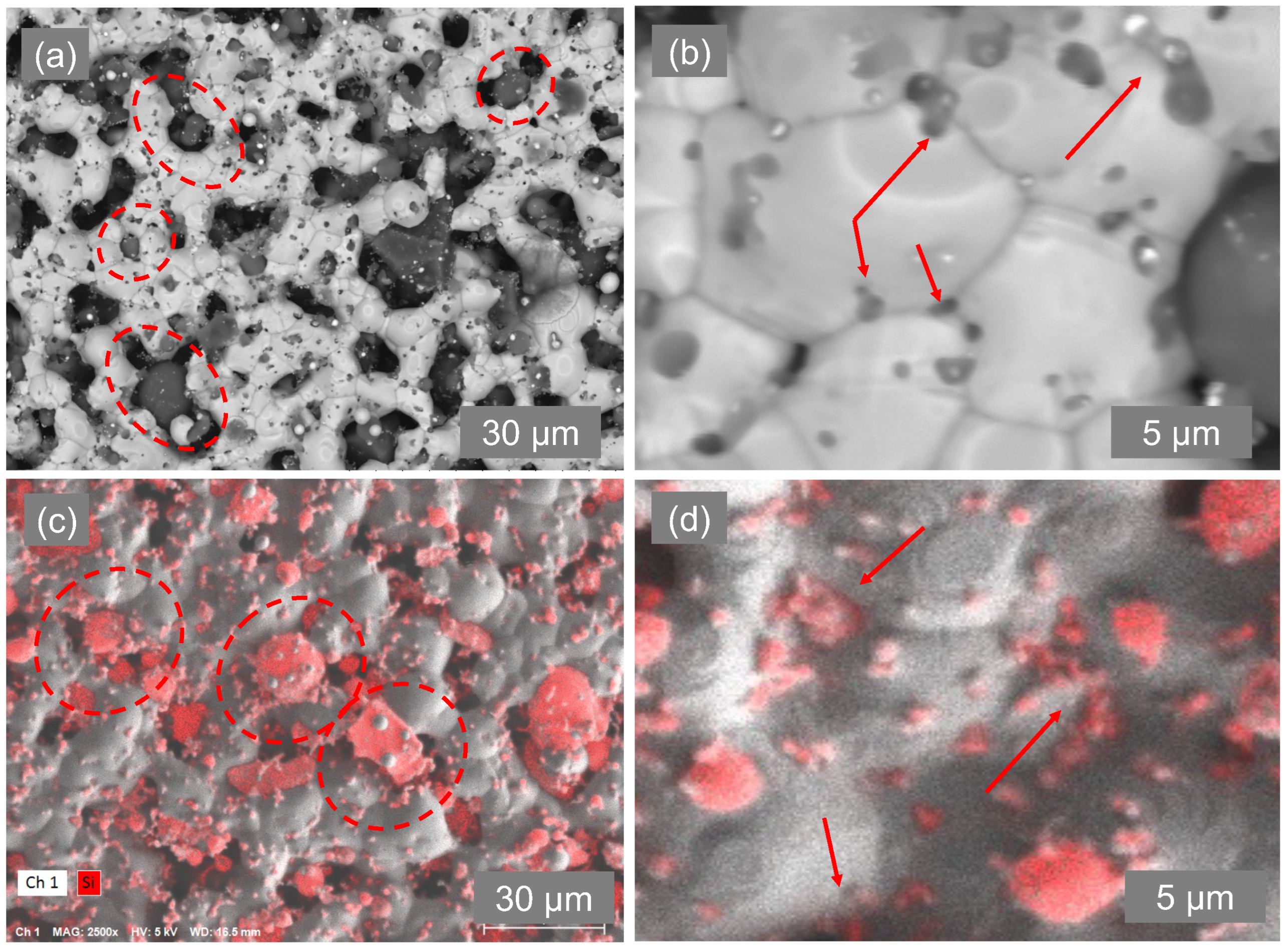

3.1. Material Characterization

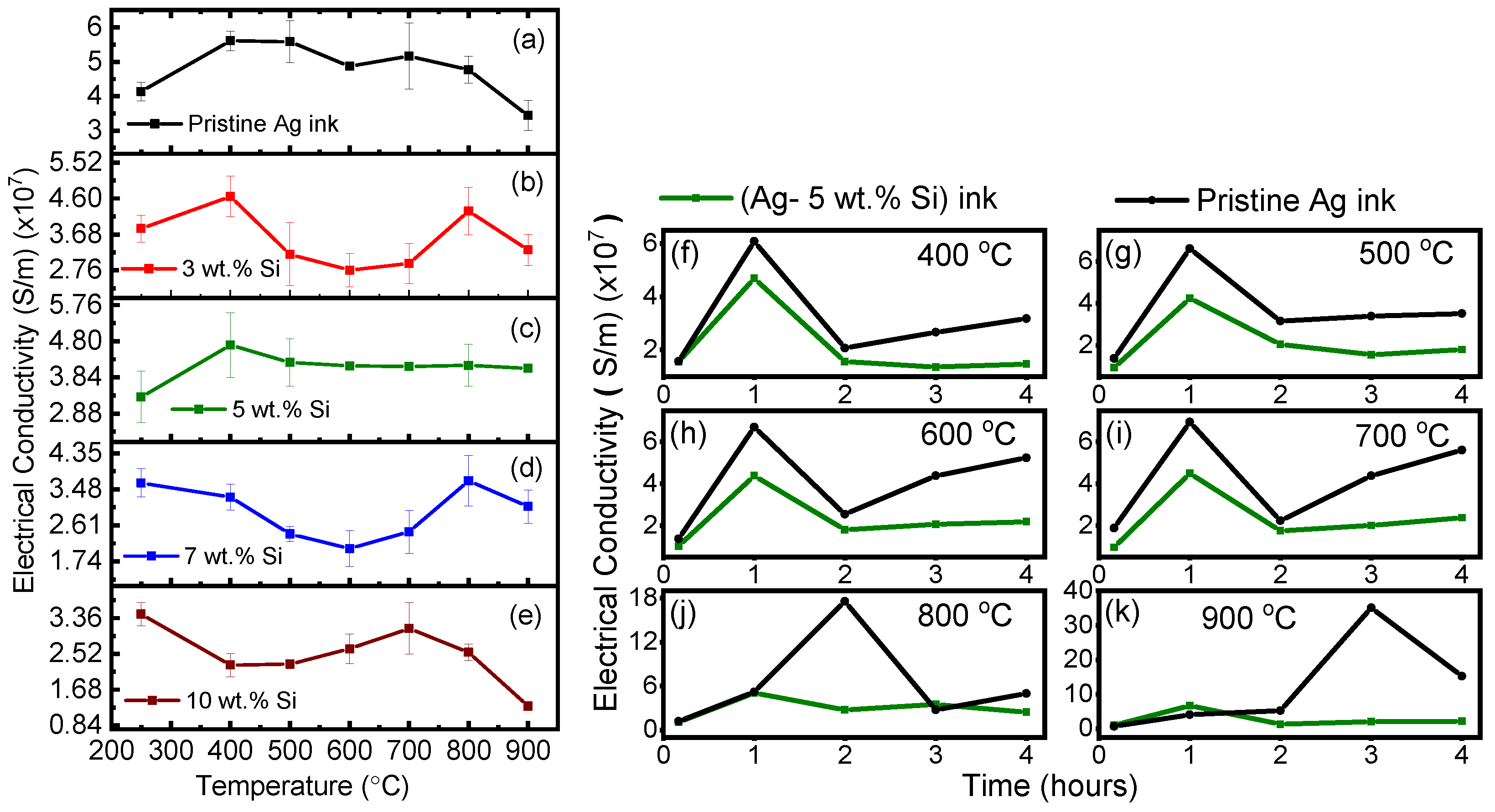

3.2. Evolution of Electrical Conductivity

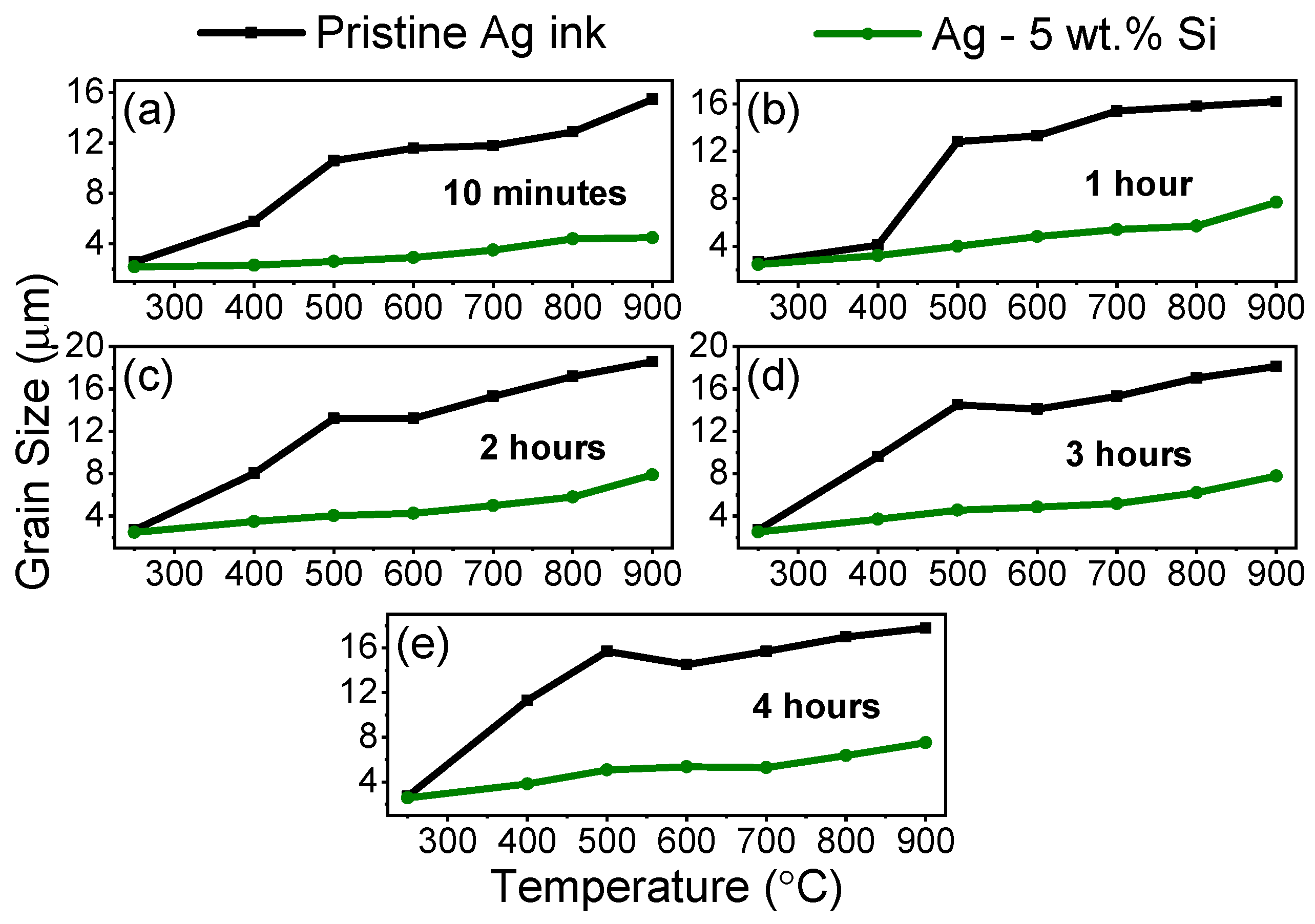

3.3. Evolution of Grain Size

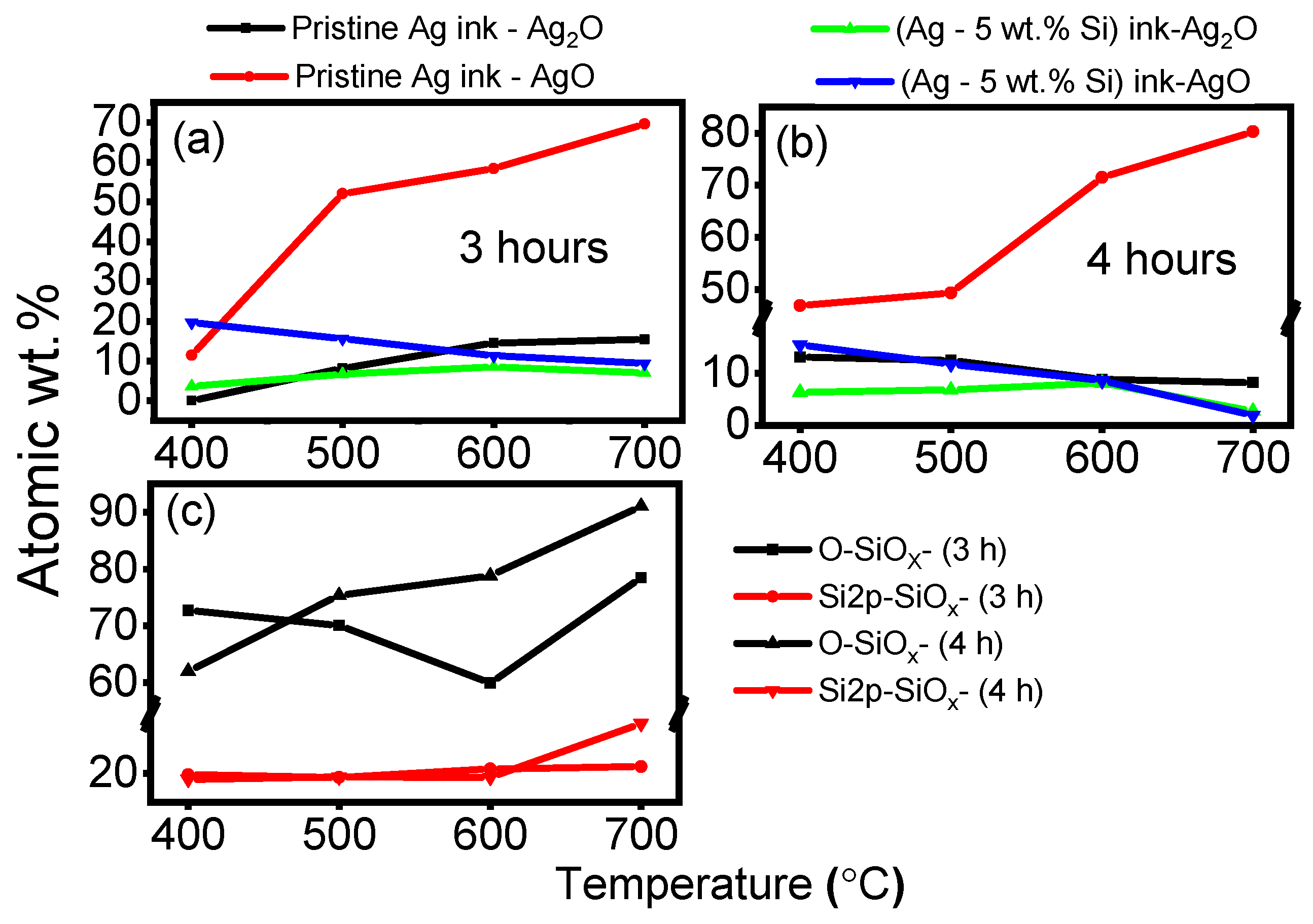

3.4. Oxidation States

- The physical grain-pinning effect due to the silicon inclusions ions present along silver grain boundaries and preventing silver domains from recombining (Zener pinning).

- The scavenger effect of the silicon particles to preferentially oxidize as opposed to silver particles, hence redirecting the incoming thermal energy towards silicon-oxygen bonds formation.

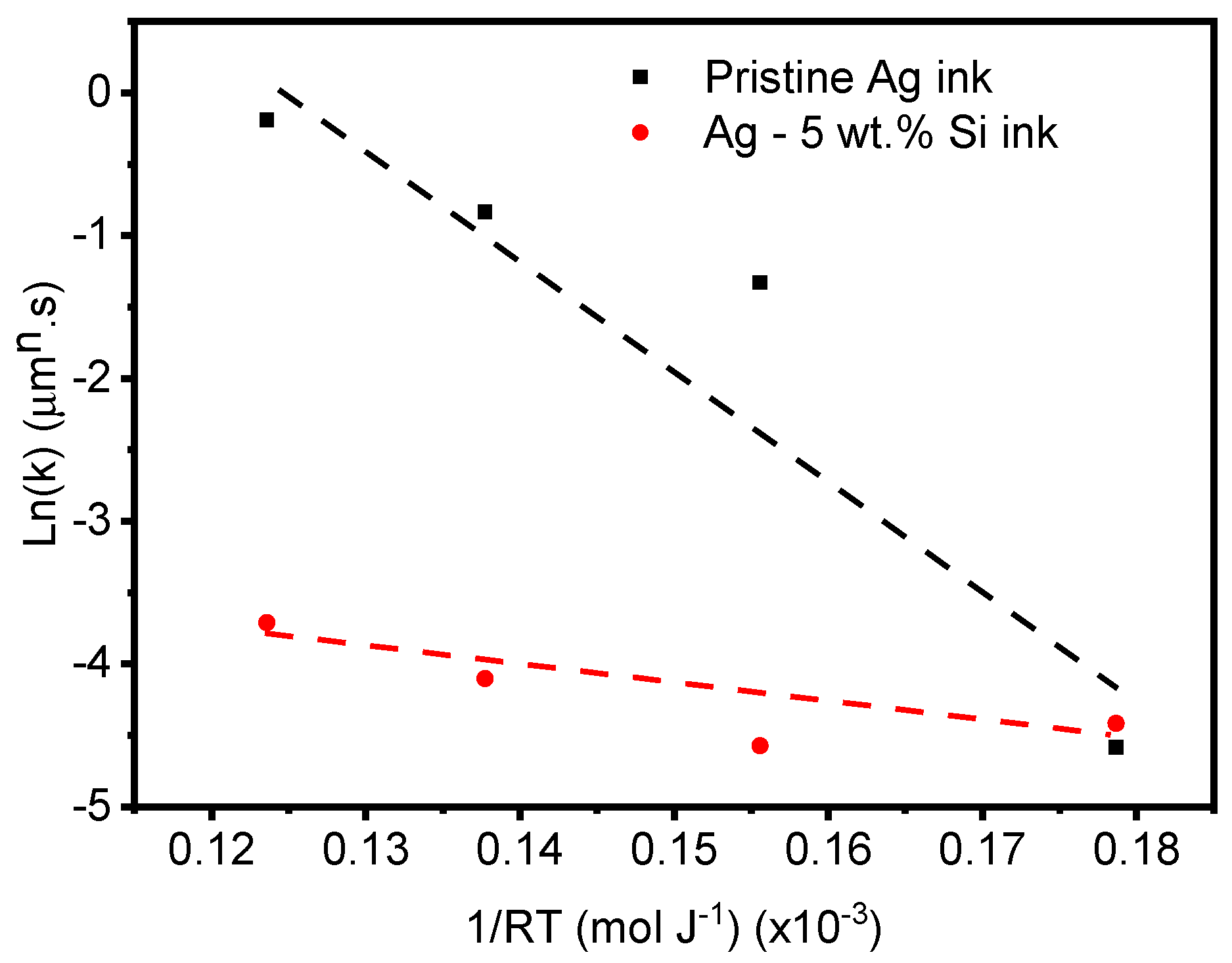

3.5. Grain Growth Kinetics

4. Conclusions

- Between 400 to 700 , the modified undergoes a 2x increase in overall grain size exhibiting normal grain growth. Whereas the pristine silver ink undergoes a 7x increase in grain size and exhibits abnormal grain growth.

- The electrical conductivity of both inks reaches a maximum at 1 hour of isothermal exposure to each temperature point indicating a transition point from sintering to grain growth. Between 1 and 2 hours of exposure, the electrical conductivity reduced indicating grain growth.

- Beyond 3 hours the pristine silver ink shows an erratic rise in electrical conductivity indicating grain growth transitioning to bulk material phase. This phenomenon is significant at higher exposure temperature ( 800 - 900 ).

- On the other hand, beyond 2 hours the electrical conductivity of the modified ink remains stable due to the Zener pinning effect.

- XPS data confirms a stark rise in silver oxide species in the pristine silver ink with increase in exposure temperatures while the silicon particles in the modified ink preferentially bond with the oxygen behaving like scavengers there by retarding the oxidation of the silver ink.

- The calculated activation energy for the modified inks is between 38 – 43 kJ mol which is significantly lower than the pristine ink.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Khuje, S.; Chivate, A.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Y.; An, L.; Shao, Z.; Wang, J.; Chang, S.; Ren, S. Printable Copper Sensor Electronics for High Temperature. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2020, 2, 1867–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhendi, M.; Alshatnawi, F.; Abbara, E.M.; Sivasubramony, R.; Khinda, G.; Umar, A.I.; Borgesen, P.; Poliks, M.D.; Shaddock, D.; Hoel, C.; Stoffel, N.; Lam, T.K.H. Printed electronics for extreme high temperature environments. Additive Manufacturing 2022, 54, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.I.; Cha, J.R.; Gong, M.S. Preparation of flexible resistive micro-humidity sensors and their humidity-sensing properties. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2013, 183, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, A.; Khuje, S.; Yu, J.; Petit, D.; Parker, T.; Zhuang, C.G.; Kester, L.; Ren, S. Ultrahigh Temperature Copper-Ceramic Flexible Hybrid Electronics. Nano Letters 2021, 21, 9279–9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, Q.; Norton, M. Thick Film Platinum Temperature Sensors. Microelectronics International 1986, 3, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebenklau, L.; Gierth, P.; Paproth, A.; Irrgang, K.; Lippmann, L.; Wodtke, A.; Niedermeyer, L.; Augsburg, K.; Bechtold, F. Temperature sensors based on thermoelectric effect 2015. p. 5.

- Arsenov, P.V.; Vlasov, I.S.; Efimov, A.A.; Minkov, K.N.; Ivanov, V.V. Aerosol Jet Printing of Platinum Microheaters for the Application in Gas Sensors. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 473, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenov, P.V.; Efimov, A.A.; Ivanov, V.V. Optimizing Aerosol Jet Printing Process of Platinum Ink for High-Resolution Conductive Microstructures on Ceramic and Polymer Substrates. Polymers 2021, 13, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y. (71) Applicant: Xerox Corporation, Norwalk, CT (US) (72) Inventors: Sarah J. Vella, Milton (CA); Guiqin Song, Milton (CA); Chad Smithson,.

- Li, Z.; Scheers, S.; An, L.; Chivate, A.; Khuje, S.; Xu, K.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chang, S.; Olenick, K.; Olenick, J.; Choi, J.H.; Zhou, C.; Ren, S. All-Printed Conformal High-Temperature Electronics on Flexible Ceramics. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2020, 2, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionkin, A.S.; Fish, B.M.; Li, Z.R.; Lewittes, M.; Soper, P.D.; Pepin, J.G.; Carroll, A.F. Screen-Printable Silver Pastes with Metallic Nano-Zinc and Nano-Zinc Alloys for Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2011, 3, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.A.; Ye, S.; Kim, M.J.; Reyes, C.; Yang, F.; Flowers, P.F.; Wiley, B.J. Multigram Synthesis of Cu-Ag Core–Shell Nanowires Enables the Production of a Highly Conductive Polymer Filament for 3D Printing Electronics. Particle & Particle Systems Characterization 2018, 35, 1700385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.; Kockerbeck, Z.A.; Jo, S.B.; Park, S.S. Hybrid Copper-Silver-Graphene Nanoplatelet Conductive Inks on PDMS for Oxidation Resistance Under Intensive Pulsed Light. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2017, 9, 37160–37165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Brown, L.; Levendorf, M.; Cai, W.; Ju, S.Y.; Edgeworth, J.; Li, X.; Magnuson, C.W.; Velamakanni, A.; Piner, R.D.; Kang, J.; Park, J.; Ruoff, R.S. Oxidation Resistance of Graphene-Coated Cu and Cu/Ni Alloy. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Ge, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Soomro, A.M.; Hong, Q.; Yang, X.; Xu, F.; Li, S.; Chen, L.J.; Cai, D.; Kang, J. Cu Nanowires Passivated with Hexagonal Boron Nitride: An Ultrastable, Selectively Transparent Conductor. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 6761–6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.K.; Hsu, H.C.; Tuan, W.H. Oxidation Behavior of Copper at a Temperature below 300 °C and the Methodology for Passivation. Materials Research 2016, 19, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Conductive Ink Market By Product (Dielectric Ink and Conductive Silver Ink), By Application (Membrane Switches, Photovoltaic, Automotive, and Displays), By Region and Companies - Industry Segment Outlook, Market Assessment, Competition Scenario, Trends and Forecast 2023-2033Conductive Ink Market Size, Share | CAGR of 6.3%. Market.us, 6745; 7.

- Ibrahim, N.; Akindoyo, J.O.; Mariatti, M. Recent development in silver-based ink for flexible electronics. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices 2022, 7, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Guo, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, Y.; Xin, Z.; Chen, Z.; Hu, K.; Han, L.; Li, L. Silver Nanoparticles Based Ink with Moderate Sintering in Flexible and Printed Electronics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.; Roppolo, I.; Chiappone, A.; Bocchini, S.; Perrone, D.; Chiolerio, A. Silver nanoparticle ink technology: state of the art. Nanotechnology, Science and Applications 2016, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Raya, C.; Denchev, Z.Z.; Cruz, S.F.; Viana, J.C. Chemistry of solid metal-based inks and pastes for printed electronics – A review. Applied Materials Today 2019, 15, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Karakoç, A.; Palko, T.; Yiğitler, H.; Ruttik, K.; Jäntti, R.; Paltakari, J. A Review on Printed Electronics: Fabrication Methods, Inks, Substrates, Applications and Environmental Impacts. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2021, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. A Review of Sintering-Bonding Technology Using Ag Nanoparticles for Electronic Packaging. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliber, E.A.; Cugno, C.; Moreno, M.; Esquivel, M.; Haberkorn, N.; Fiscina, J.E. Sintering of porous silver compacts at controlled heating rates in oxygen or argon 2003. p. 8.

- Chen, C.; Suganuma, K. Microstructure and mechanical properties of sintered Ag particles with flake and spherical shape from nano to micro size. Materials & Design 2019, 162, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkman, S.K.; Yin, S.; Bakhishev, T.; Puntambekar, K.; Subramanian, V.; Toney, M.F. Mechanistic Studies on Sintering of Silver Nanoparticles. Chemistry of Materials 2011, 23, 4634–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Hu, A.; Gerlich, A.P.; Zou, G.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.N. Joining of Silver Nanomaterials at Low Temperatures: Processes, Properties, and Applications. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2015, 7, 12597–12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.Z. (Ed.) Sintering of advanced materials: fundamentals and processes; Woodhead Publishing in materials, WP, Woodhead Publ: Oxford, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Long, X.; Du, C.; Hu, B.; Li, M. Comparison of sintered silver micro and nano particles: from microstructure to property. 2018 20th International Conference on Electronic Materials and Packaging (EMAP), 2018, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Roberson, D.A.; Wicker, R.B.; Murr, L.E.; Church, K.; MacDonald, E. Microstructural and Process Characterization of Conductive Traces Printed from Ag Particulate Inks. Materials 2011, 4, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, D.C.; Kim, T.W. Degradation mechanisms of silver nanowire electrodes under ultraviolet irradiation and heat treatment. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.V.; Carel, R. Stress and grain growth in thin films. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 1996, 44, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, W.E.; Hu, S.; Overman, N.; Lavender, C.; Joshi, V.V. Short communication on Kinetics of grain growth and particle pinning in U-10 wt.% Mo. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2018, 498, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarpour, M.; Farvizi, M.; Kim, H. Microstructural and kinetic investigation on the suppression of grain growth in nanocrystalline copper by the dispersion of silicon carbide nanoparticles. Materials & Design 2017, 119, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Ahn, S.J.; Ha, T.H.; Kim, H.S. Grain-size effect on the electrical properties of nanocrystalline indium tin oxide thin films. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2015, 199, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Lee, T.M.; Kim, J. A study on the electrical and mechanical properties of printed Ag thin films for flexible device application. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2014, 596, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahandeh, S.; Militzer, M. Grain boundary curvature and grain growth kinetics with particle pinning. Philosophical Magazine 2013, 93, 3231–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmiller, J.; Woo, N.C.; Spolenak, R. Microstructure–property relationship in highly ductile Au–Cu thin films for flexible electronics. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2010, 527, 7731–7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Khuje, S.; Sheng, A.; Kilczewski, S.; Parker, T.; Ren, S. High-Temperature Copper–Graphene Conductors via Aerosol Jetting. Advanced Engineering Materials 2022, 24, 2200284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratello, V.; Nino, G.; Wadhwa, A.; Kent, L. (54) REFRACTORY METAL INKS AND RELATED SYSTEMIS FOR AND METHODS OF MAKING HIGH-MELTING-POINT ARTICLES.

- Rahman, M.T.; McCloy, J.; Ramana, C.V.; Panat, R. Structure, electrical characteristics, and high-temperature stability of aerosol jet printed silver nanoparticle films. Journal of Applied Physics 2016, 120, 075305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SALEMI, A. Silicon Carbide Technology for High- and Ultra-High-Voltage Bipolar Junction Transistors and PiN Diodes. Doctoral Thesis, in Information and Communication Technology, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shyjumon, I.; Gopinadhan, M.; Ivanova, O.; Quaas, M.; Wulff, H.; Helm, C.A.; Hippler, R. Structural deformation, melting point and lattice parameter studies of size selected silver clusters. The European Physical Journal D - Atomic, Molecular, Optical and Plasma Physics 2006, 37, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, B.; Sun, Y.; Xia, Y. Synthesis of Silver Nanostructures with Controlled Shapes and Properties. Accounts of Chemical Research 2007, 40, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvizo, R.R.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Kudgus, R.A.; Giri, K.; Bhattacharya, R.; Mukherjee, P. Intrinsic therapeutic applications of noble metal nanoparticles: past, present and future. Chemical Society Reviews 2012, 41, 2943–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Qiao, X.; Qiu, X.; Chen, J. Synthesis and electrical properties of uniform silver nanoparticles for electronic applications. Journal of Materials Science 2009, 44, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Chewchinda, P.; Ohtani, H.; Odawara, O.; Wada, H. Effects of Laser Energy Density on Silicon Nanoparticles Produced Using Laser Ablation in Liquid. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2013, 441, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Chang, Y.H. Growth without Postannealing of Monoclinic VO2 Thin Film by Atomic Layer Deposition Using VCl4 as Precursor. Coatings 2018, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, S.; Goh, G.L.; Dinh Le, T.S.; An, J.; Peh, Z.K.; Yeong, W.Y.; Kim, Y.J. Wearable Bandage-Based Strain Sensor for Home Healthcare: Combining 3D Aerosol Jet Printing and Laser Sintering. ACS Sensors 2019, 4, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, E.; Hamblyn, S.; Claypole, T.; Gethin, D. Deposition of High Conductivity Low Silver Content Materials by Screen Printing. Coatings 2015, 5, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Koo, J.B.; Baeg, K.J.; Noh, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Jung, S.W.; Ju, B.K.; You, I.K. Effect of Curing Temperature on Nano-Silver Paste Ink for Organic Thin-Film Transistors. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2012, 12, 3272–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Ryu, J.; Kim, H.S.; Hahn, H.T. Sintering of Inkjet-Printed Silver Nanoparticles at Room Temperature Using Intense Pulsed Light. Journal of Electronic Materials 2011, 40, 2268–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqida, S.N.; Ghazali, M.I.; Hashim, J. Effects Of Porosity On Mechanical Properties Of Metal Matrix Composite: An Overview. Jurnal Teknologi A, P: 17–32. Number: 40A Publisher.

- Baker, S.P.; Saha, K.; Shu, J.B. Effect of thickness and Ti interlayers on stresses and texture transformations in thin Ag films during thermal cycling. Applied Physics Letters 2013, 103, 191905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.Q.; Chen, Z.H.; Zou, J.P.; Zhang, Z.J. Grain Growth and Microstructure of Silver Film Doped Finite Glass on Ferrite Substrates at High Annealing Temperature. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2022, 96, 1519–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, D.; Goudeli, E. Oxidation Rate and Crystallinity Dynamics of Silver Nanoparticles at High Temperatures. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2023, 127, 13389–13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.U.; Kim, K.S.; Jung, S.B. Effects of oxidation on reliability of screen-printed silver circuits for radio frequency applications. Microelectronics Reliability 2016, 63, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, W.K.; Lim, H.M.; Huh, S.H.; Park, S.E.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, S.H. Effect of the average particle size and the surface oxidation layer of silicon on the colloidal silica particle through direct oxidation. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2009, 163, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, R.; Iijima, S. Oxidation property of silicon small particles. Applied Physics Letters 1991, 58, 1662–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’vov, B.V. Kinetics and mechanism of thermal decomposition of silver oxide. Thermochimica Acta 1999, 333, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Inami, K.; Motoyama, K.; Sano, T.; Hirose, A. Silver oxide decomposition mediated direct bonding of silicon-based materials. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 10472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. E, B.; D, T. Recrystallization and grain growth. Progress in Metal Physics 1952, Volume 3, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, R.; Stach, E.A.; Groza, J.R.; Dresser, B.J. In-situ TEM observations of abnormal grain growth, coarsening, and substrate de-wetting in nanocrystalline Ag thin films. Thin Solid Films 2000, 370, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Cui, E.; Sun, Z.; Yu, H. Grain growth kinetics and grain refinement mechanism in Al2O3/WC/TiC/graphene ceramic composite. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2021, 41, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollett, A.D.; Gottstein, G.; Shvindlerman, L.S.; Molodov, D.A. Grain boundary mobility – a brief review. Zeitschrift für Metallkunde 2004, 95, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C. Grain Growth in Polycrystalline Thin Films. MRS Proceedings 2011, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenker, T.; Valero, M.; Schock, H.; Werner, J. Grain growth studies of thin Cu(In, Ga)Se2 films. Journal of Crystal Growth 2004, 264, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, J. DETERMINATION OF THE GRAIN GROWTH KINETICS AS A BASE PARAMETER FOR NUMERICAL SIMULATION DEMAND. | MM Science Journal | EBSCOhost, 2015. 6: ISSN: 1803-1269 Pages, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwalani, B.; Salloom, R.; Alam, T.; Valentin, S.G.; Zhou, X.; Thompson, G.; Srinivasan, S.G.; Banerjee, R. Composition-dependent apparent activation-energy and sluggish grain-growth in high entropy alloys. Materials Research Letters 2019, 7, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mičian, M.; Frátrik, M.; Moravec, J.; Švec, M. Determination of Grain Growth Kinetics of S960MC Steel. Materials 2022, 15, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarpour, M.R.; Hesari, F.A. Characterization and hardness of TiCu–Ti 2 Cu 3 intermetallic material fabricated by mechanical alloying and subsequent annealing. Materials Research Express 2016, 3, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.N.; Godfrey, A.; Hansen, N.; Zhang, X.D. Microstructure and mechanical strength of near- and sub-micrometre grain size copper prepared by spark plasma sintering. Materials & Design 2017, 117, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.N.; Enayati, M.H.; Karimzadeh, F. Nanoscale Grain Growth Behaviour of CoAl Intermetallic Synthesized by Mechanical Alloying. Bulletin of Materials Science 2014, 37, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillert, M. On the theory of normal and abnormal grain growth. Acta Metallurgica 1965, 13, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.B.; Yoon, D.Y. The dependence of normal and abnormal grain growth in silver on annealing temperature and atmosphere. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2001, 32, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.P.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Zheng, L.Q.; Ding, X.H. Behaviors of ZnO-doped silver thick film and silver grain growth mechanism. Solid State Sciences 2011, 13, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature | Ag only ink | (Ag-5 wt.% Si) ink | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | k | n | k | |

| 400 | 1.58 | 0.010 | 2.41 | 0.012 |

| 500 | 3.01 | 0.264 | 2.01 | 0.010 |

| 600 | 3.57 | 0.433 | 2.20 | 0.016 |

| 700 | 4.15 | 0.826 | 2.36 | 0.024 |

| Growth rate | Abnormal | Normal | ||

| Q (kJ mol) | 80.2 ± 19.15 | 38.52 ± 7.345 | ||

| R | 0.9 | 0.93 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).