Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Main Text

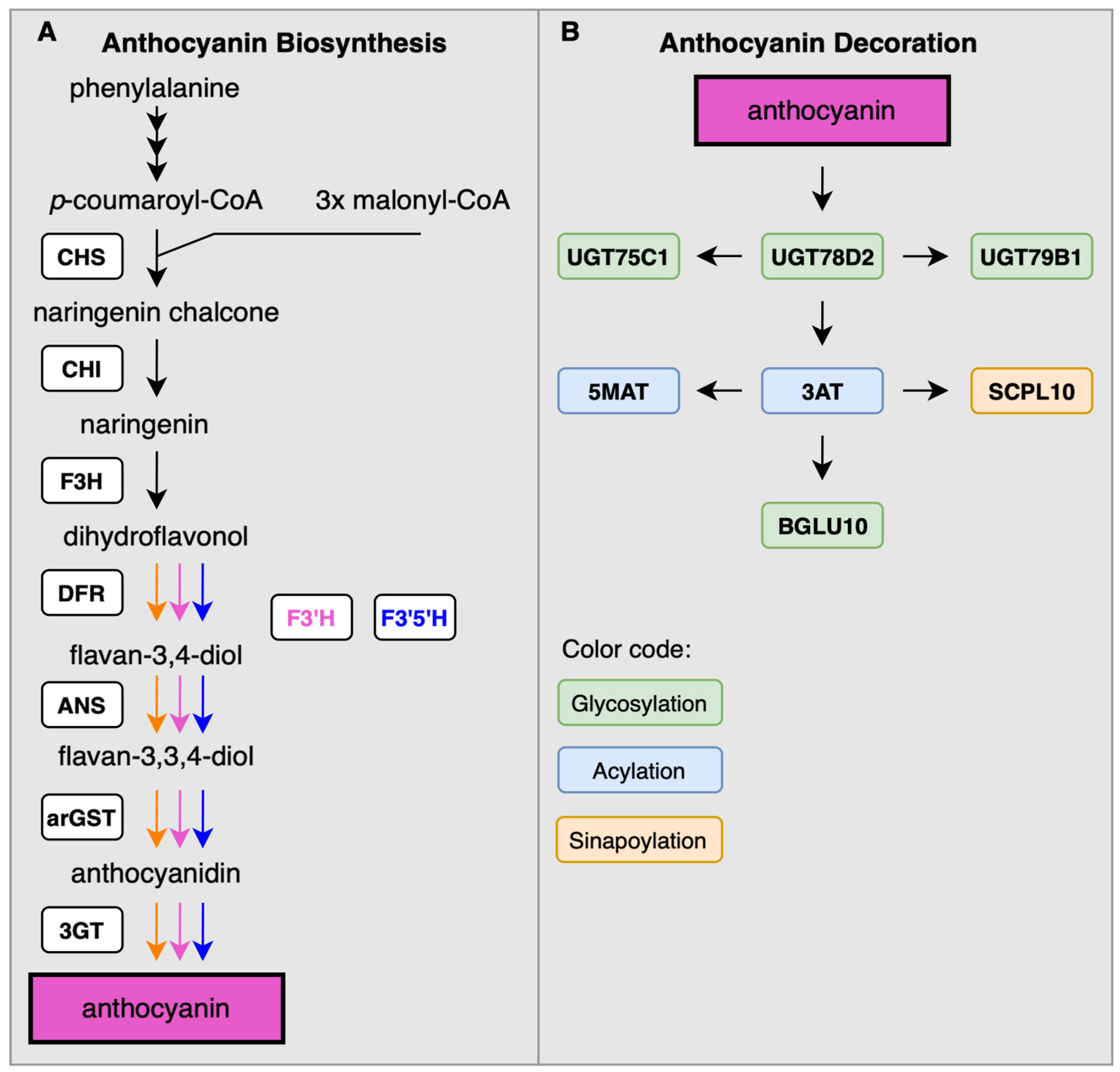

Biosynthesis of a Diverse Set of Anthocyanins

Enzyme Promiscuity Associated with the Anthocyanin Biosynthesis

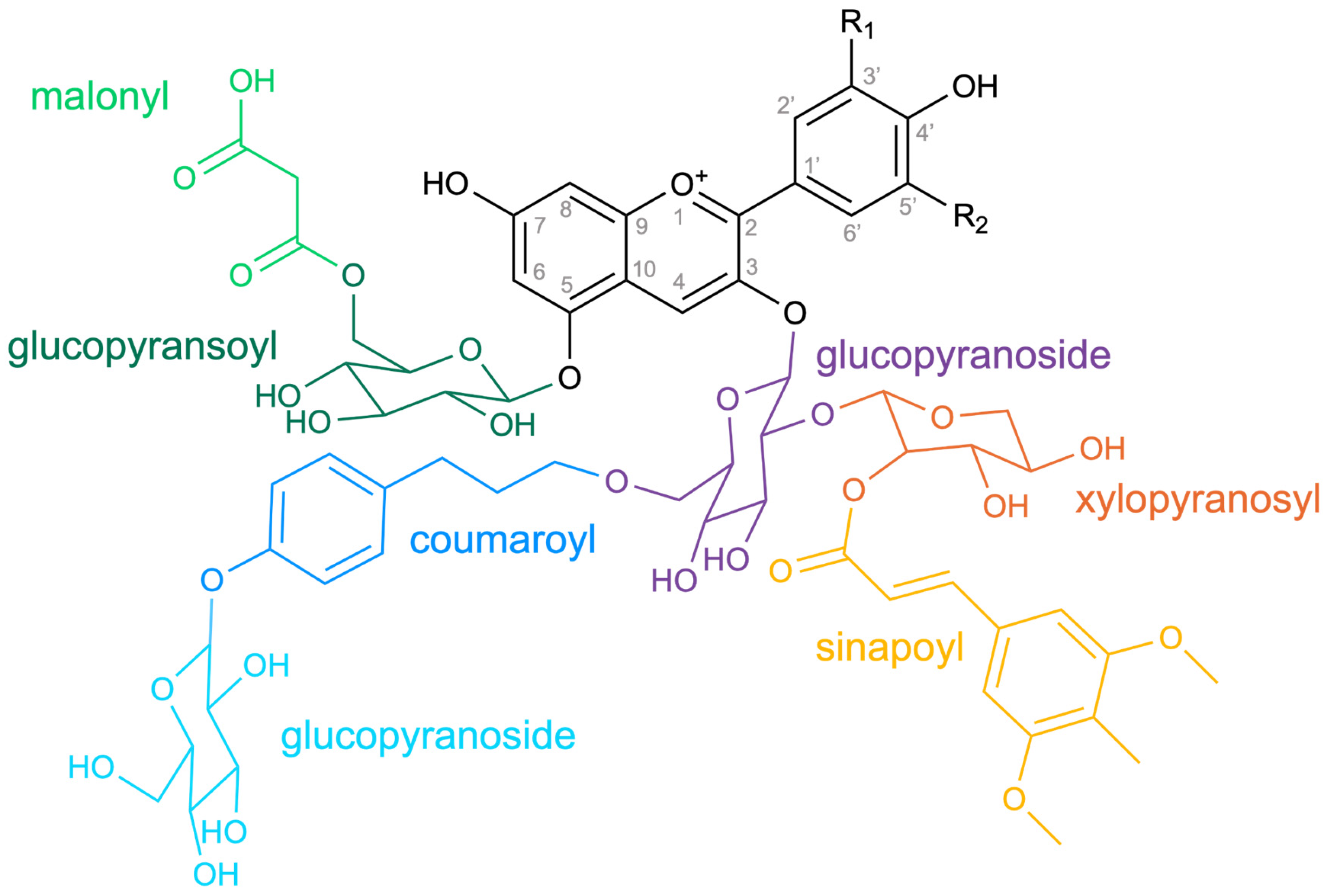

Diversity of Anthocyanin Decoration

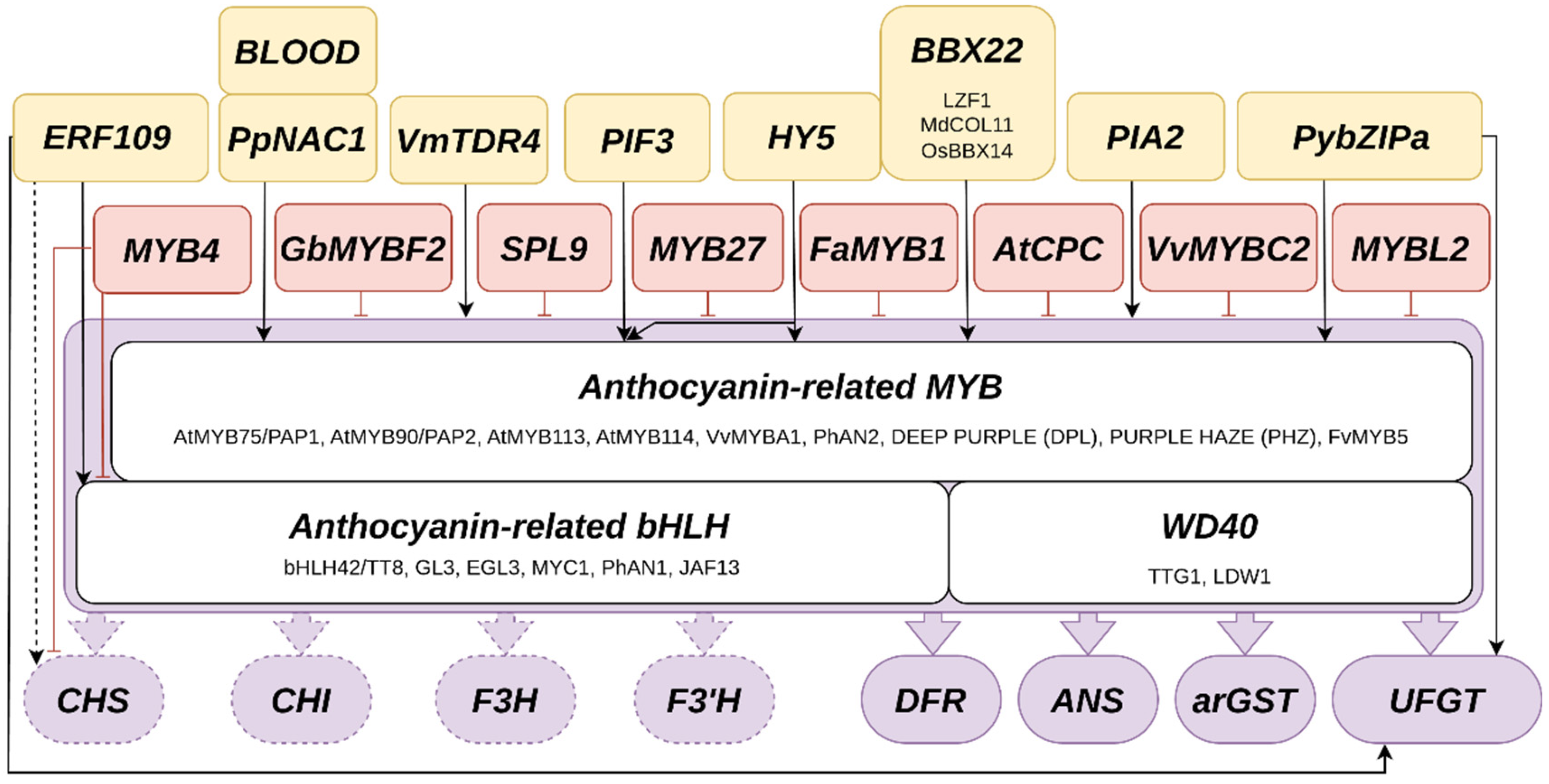

Transcriptional Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis

Lineage-Specific Differences in the MBW Complex

Additional Transcription Factors Influence Anthocyanin Biosynthesis

Regulatory RNAs in the Anthocyanin Biosynthesis

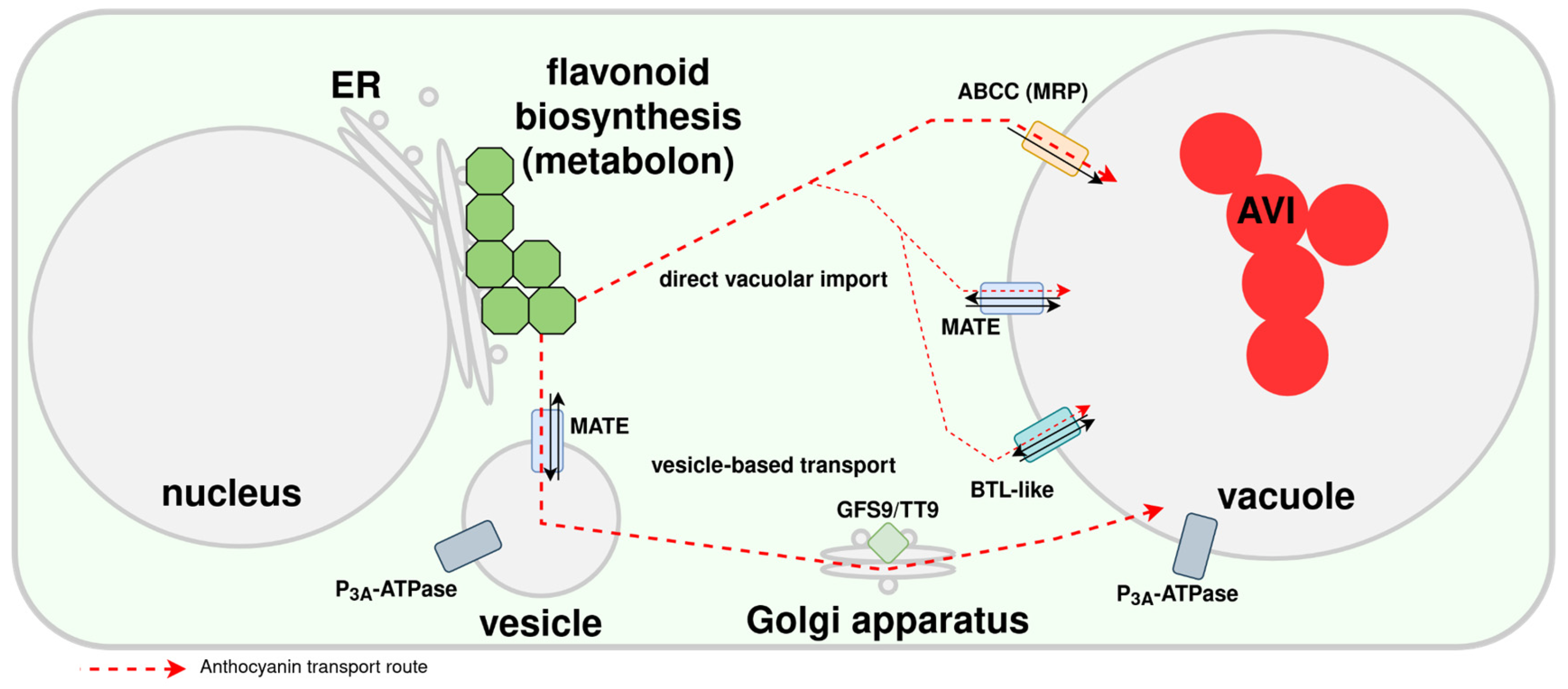

Transport of Anthocyanins

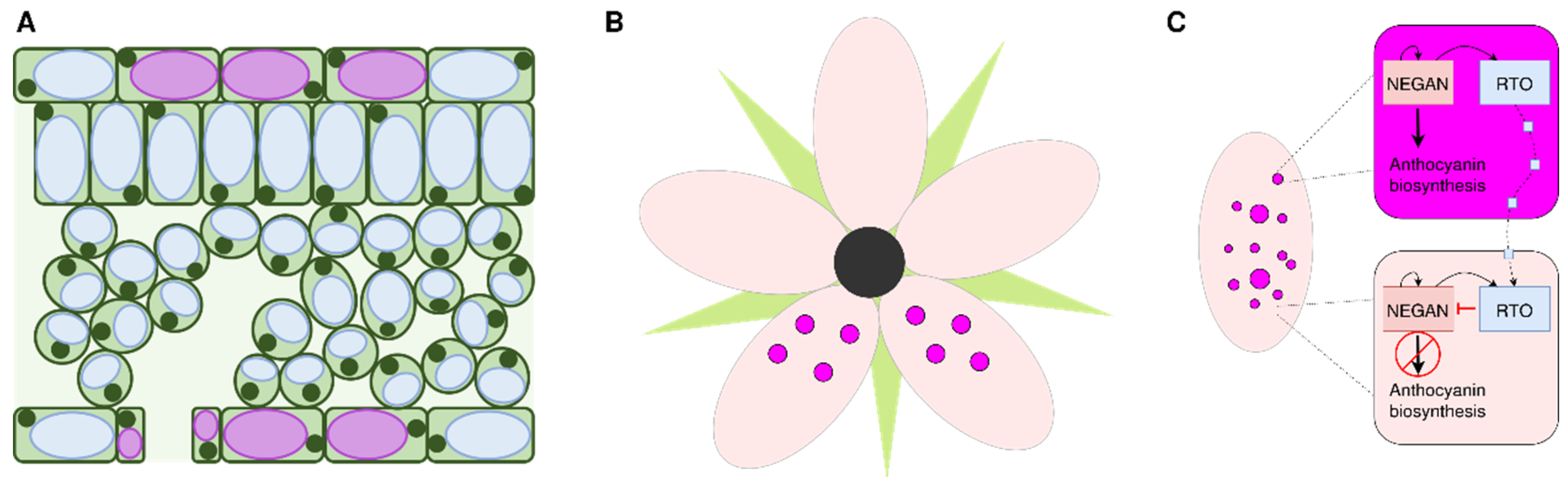

Cell-Specific Accumulation of Anthocyanins and Pigmentation Patterns

Ecological Functions of Anthocyanins

Protective Functions of Anthocyanins in Photosynthetically Active Plant Organs

Importance of Anthocyanins in Drought and Salt Stress Response

Cold Stress Response

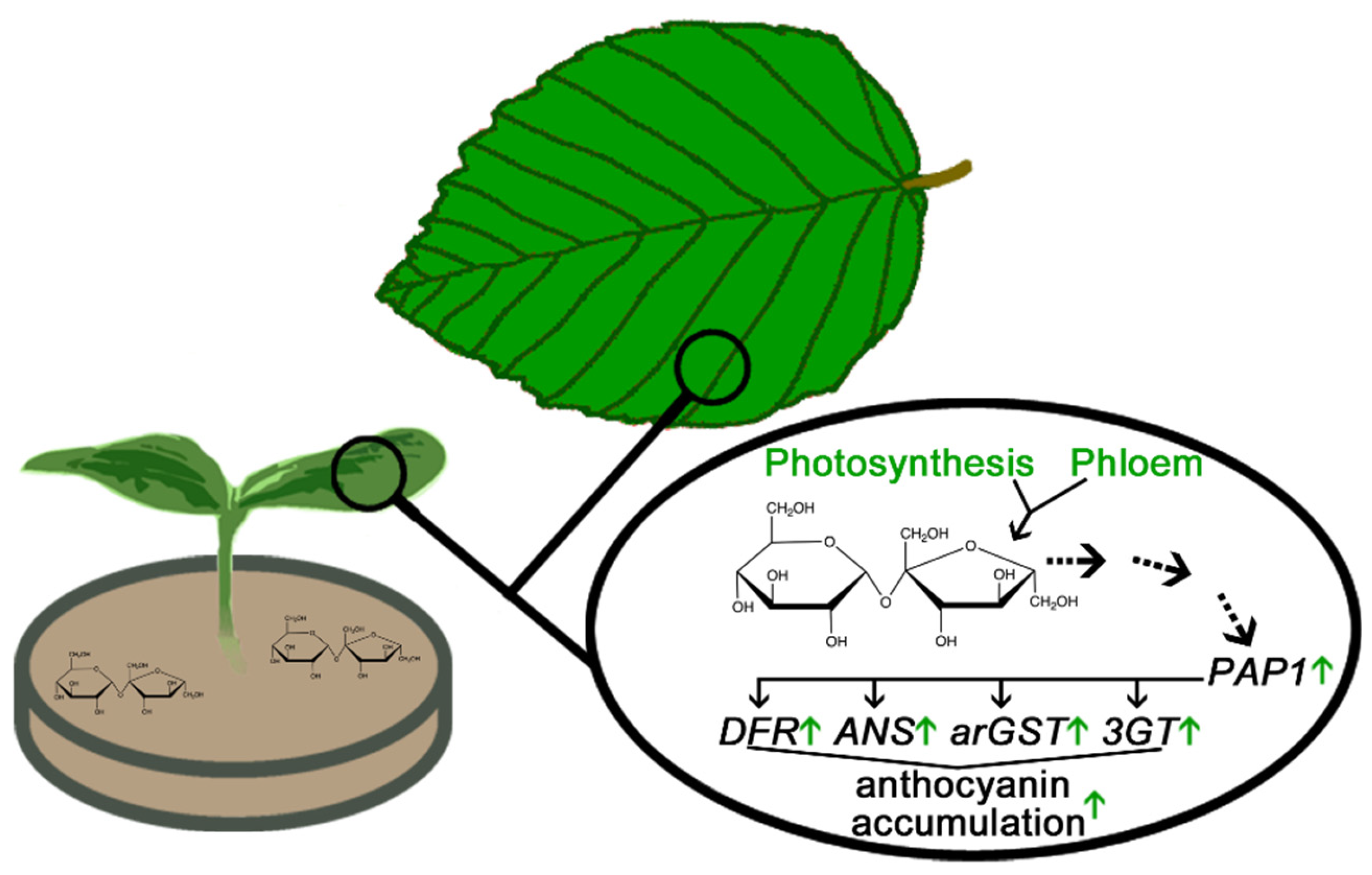

Anthocyanin Accumulation as Sign of Nutritional Imbalance

Pollinator Attraction

Seed Disperser Attraction

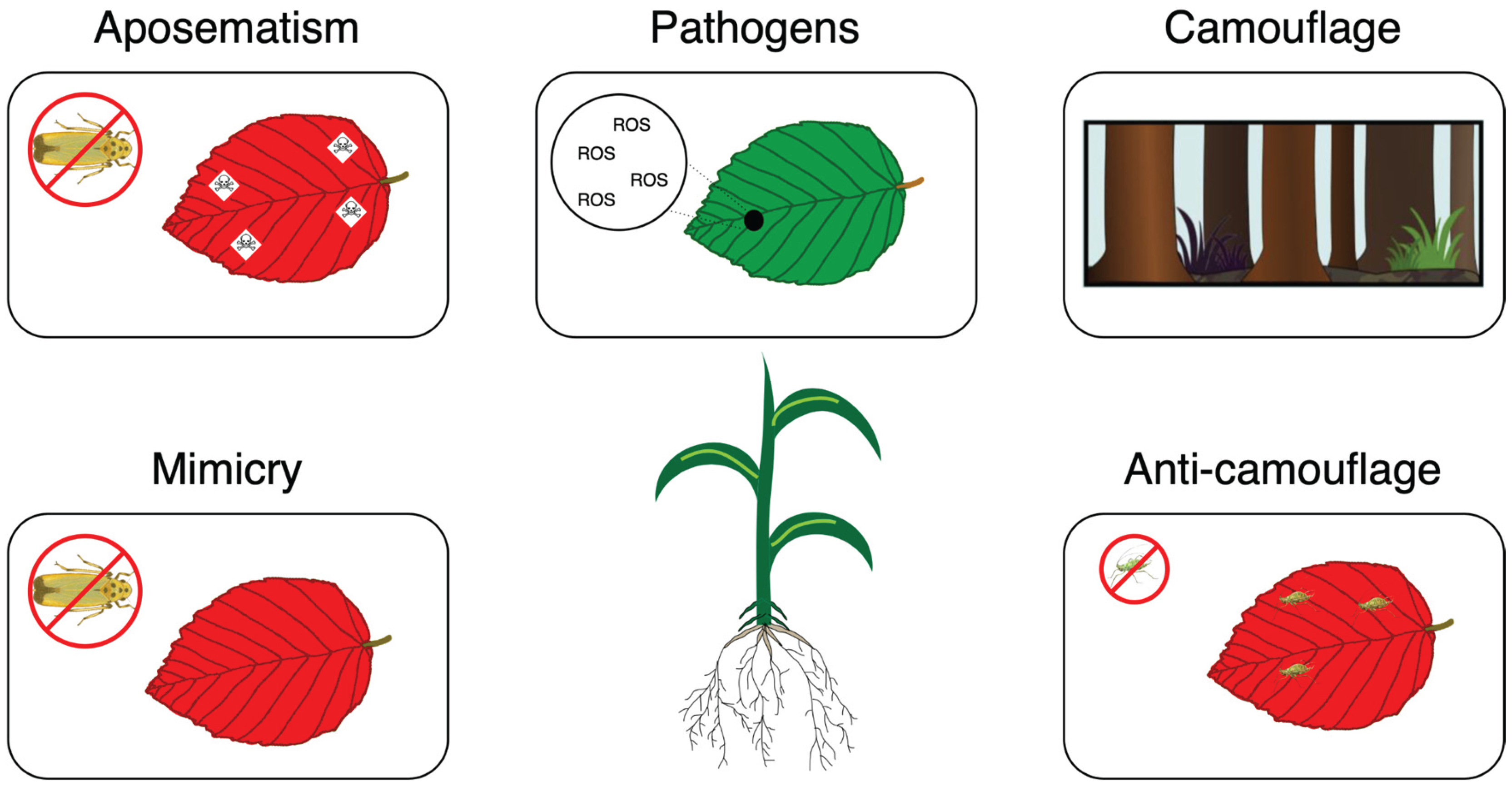

Herbivore Repellence and Pathogen Resistances

Conclusions

Funding

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

Authors’ contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Wheldale M. The anthocyanin pigments of plants. 1916.

- Gu K-D, Wang C-K, Hu D-G, Hao Y-J. How do anthocyanins paint our horticultural products? Sci Hortic. 2019;249:257–62. [CrossRef]

- Lozoya-Gloria E, Cuéllar-González F, Ochoa-Alejo N. Anthocyanin metabolic engineering of Euphorbia pulcherrima: advances and perspectives. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14.

- Cardi T, Murovec J, Bakhsh A, Boniecka J, Bruegmann T, Bull SE, et al. CRISPR/Cas-mediated plant genome editing: outstanding challenges a decade after implementation. Trends Plant Sci. 2023;28:1144–65. [CrossRef]

- Winkel-Shirley B. Flavonoid Biosynthesis. A Colorful Model for Genetics, Biochemistry, Cell Biology, and Biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:485–93. [CrossRef]

- Kopp A. METAMODELS AND PHYLOGENETIC REPLICATION: A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH TO THE EVOLUTION OF DEVELOPMENTAL PATHWAYS. Evolution. 2009;63:2771–89. [CrossRef]

- McClintock B. The Origin and Behavior of Mutable Loci in Maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1950;36:344–55.

- Marquardt C. Die Farben der Blüthen. Habicht; 1835.

- Mendel G. Versuche uber pflanzen-hybriden. Vorgelegt Den Sitzungen. 1865.

- Hellens RP, Moreau C, Lin-Wang K, Schwinn KE, Thomson SJ, Fiers MWEJ, et al. Identification of Mendel’s White Flower Character. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:e13230. [CrossRef]

- Moreau C, Ambrose MJ, Turner L, Hill L, Ellis THN, Hofer JMI. The B gene of pea encodes a defective flavonoid 3’,5’-hydroxylase, and confers pink flower color. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:759–68. [CrossRef]

- Narbona E, Del Valle JC, Whittall JB, León-Osper M, Buide ML, Pulgar I, et al. Transcontinental patterns in floral pigment abundance among animal-pollinated species. Sci Rep. 2025;15:15927. [CrossRef]

- Ho WW, Smith SD. Molecular evolution of anthocyanin pigmentation genes following losses of flower color. BMC Evol Biol. 2016;16:98. [CrossRef]

- Del Valle JC, Alcalde-Eon C, Escribano-Bailón MT, Buide ML, Whittall JB, Narbona E. Stability of petal color polymorphism: the significance of anthocyanin accumulation in photosynthetic tissues. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:496. [CrossRef]

- Wong DCJ, Wang Z, Perkins J, Jin X, Marsh GE, John EG, et al. The road less taken: Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase inactivation and delphinidin anthocyanin loss underpins a natural intraspecific flower colour variation. Mol Ecol. 2024;:e17334. [CrossRef]

- Marin-Recinos MF, Pucker B. Genetic factors explaining anthocyanin pigmentation differences. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24:627. [CrossRef]

- Smith SD, Goldberg EE. Tempo and mode of flower color evolution. Am J Bot. 2015;102:1014–25. [CrossRef]

- Timoneda A, Feng T, Sheehan H, Walker-Hale N, Pucker B, Lopez-Nieves S, et al. The evolution of betalain biosynthesis in Caryophyllales. New Phytol. 2019;224:71–85. [CrossRef]

- Mabry TJ, Turner BL. Chemical Investigations of the Batidaceae. TAXON. 1964;13:197–200. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan H, Feng T, Walker-Hale N, Lopez-Nieves S, Pucker B, Guo R, et al. Evolution of l-DOPA 4,5-dioxygenase activity allows for recurrent specialisation to betalain pigmentation in Caryophyllales. New Phytol. 2020;227:914–29. [CrossRef]

- Pucker B, Walker-Hale N, Dzurlic J, Yim WC, Cushman JC, Crum A, et al. Multiple mechanisms explain loss of anthocyanins from betalain-pigmented Caryophyllales, including repeated wholesale loss of a key anthocyanidin synthesis enzyme. New Phytol. 2024;241:471–89. [CrossRef]

- Khatun N, Jones A, Rahe A, Choudhary N, Pucker B. Evolutionary Rewiring of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Pathway in Poaceae. 2025;:2025.09.21.677584. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary N, Hagedorn M, Pucker B. Large-scale Phylogenomics Reveals Systematic Loss of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Genes at the Family Level in Cucurbitaceae. 2025;:2025.10.06.680802. [CrossRef]

- Pucker B, Reiher F, Schilbert HM. Automatic Identification of Players in the Flavonoid Biosynthesis with Application on the Biomedicinal Plant Croton tiglium. Plants. 2020;9:1103. [CrossRef]

- Hughes NM, Connors MK, Grace MH, Lila MA, Willans BN, Wommack AJ. The same anthocyanins served four different ways: Insights into anthocyanin structure-function relationships from the wintergreen orchid, Tipularia discolor. Plant Sci. 2021;303:110793. [CrossRef]

- Murai Y, Kokubugata G, Yokota M, Kitajima J, Iwashina T. Flavonoids and anthocyanins from six Cassytha taxa (Lauraceae) as taxonomic markers. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2008;36:745–8. [CrossRef]

- Andersen ØM, Jordheim M. The Anthocyanins. In: Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Applications. 2006.

- Saigo T, Wang T, Watanabe M, Tohge T. Diversity of anthocyanin and proanthocyanin biosynthesis in land plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2020;55:93–9. [CrossRef]

- Bloor SJ, Abrahams S. The structure of the major anthocyanin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2002;59:343–6. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S, et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D1373–80. [CrossRef]

- Grotewold E. The genetics and biochemistry of floral pigments. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:761–80. [CrossRef]

- Eichenberger M, Schwander T, Hüppi S, Kreuzer J, Mittl PRE, Peccati F, et al. The catalytic role of glutathione transferases in heterologous anthocyanin biosynthesis. Nat Catal. 2023;6:927–38. [CrossRef]

- Seitz C, Ameres S, Forkmann G. Identification of the molecular basis for the functional difference between flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase and flavonoid 3’,5’-hydroxylase. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3429–34. [CrossRef]

- Dudek A, Spiegel M, Strugała-Danak P, Gabrielska J. Analytical and Theoretical Studies of Antioxidant Properties of Chosen Anthocyanins; A Structure-Dependent Relationships. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:5432. [CrossRef]

- Rempel A, Choudhary N, Pucker B. KIPEs3: Automatic annotation of biosynthesis pathways. PLOS ONE. 2023;18:e0294342. [CrossRef]

- Moghe GD, Last RL. Something Old, Something New: Conserved Enzymes and the Evolution of Novelty in Plant Specialized Metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:1512–23. [CrossRef]

- Waki T, Mameda R, Nakano T, Yamada S, Terashita M, Ito K, et al. A conserved strategy of chalcone isomerase-like protein to rectify promiscuous chalcone synthase specificity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:870. [CrossRef]

- Ni R, Zhu T-T, Zhang X-S, Wang P-Y, Sun C-J, Qiao Y-N, et al. Identification and evolutionary analysis of chalcone isomerase-fold proteins in ferns. J Exp Bot. 2020;71:290–304. [CrossRef]

- Ban Z, Qin H, Mitchell AJ, Liu B, Zhang F, Weng J-K, et al. Noncatalytic chalcone isomerase-fold proteins in Humulus lupulus are auxiliary components in prenylated flavonoid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E5223–32. [CrossRef]

- Wolf-Saxon ER, Moorman CC, Castro A, Ruiz-Rivera A, Mallari JP, Burke JR. Regulatory ligand binding in plant chalcone isomerase-like (CHIL) proteins. J Biol Chem. 2023;299:104804. [CrossRef]

- Martens S, Forkmann G, Britsch L, Wellmann F, Matern U, Lukačin R. Divergent evolution of flavonoid 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases in parsley 1. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:93–8. [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt YH, Witte S, Steuber H, Matern U, Martens S. Evolution of Flavone Synthase I from Parsley Flavanone 3β-Hydroxylase by Site-Directed Mutagenesis. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1442–54. [CrossRef]

- Kawai Y, Ono E, Mizutani M. Evolution and diversity of the 2–oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily in plants. Plant J. 2014;78:328–43. [CrossRef]

- Li D-D, Ni R, Wang P-P, Zhang X-S, Wang P-Y, Zhu T-T, et al. Molecular Basis for Chemical Evolution of Flavones to Flavonols and Anthocyanins in Land Plants. Plant Physiol. 2020;184:1731–43. [CrossRef]

- Schilbert HM, Schöne M, Baier T, Busche M, Viehöver P, Weisshaar B, et al. Characterization of the Brassica napus Flavonol Synthase Gene Family Reveals Bifunctional Flavonol Synthases. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12.

- Busche M, Acatay C, Martens S, Weisshaar B, Stracke R. Functional Characterisation of Banana (Musa spp.) 2-Oxoglutarate-Dependent Dioxygenases Involved in Flavonoid Biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Davies KM, Andre CM, Kulshrestha S, Zhou Y, Schwinn KE, Albert NW, et al. The evolution of flavonoid biosynthesis. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2024;379:20230361. [CrossRef]

- Pucker B, Iorizzo M. Apiaceae FNS I originated from F3H through tandem gene duplication. PLOS ONE. 2023;18:e0280155. [CrossRef]

- Tohge T, Nishiyama Y, Hirai MY, Yano M, Nakajima J, Awazuhara M, et al. Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2005;42:218–35. [CrossRef]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Fukushima A, Nakabayashi R, Hanada K, Matsuda F, Sugawara S, et al. Two glycosyltransferases involved in anthocyanin modification delineated by transcriptome independent component analysis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2012;69:154–67. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, Nishiyama Y, Fuell C, Taguchi G, Elliott K, Hill L, et al. Convergent evolution in the BAHD family of acyl transferases: identification and characterization of anthocyanin acyl transferases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;50:678–95. [CrossRef]

- Kovinich N, Kayanja G, Chanoca A, Riedl K, Otegui MS, Grotewold E. Not all anthocyanins are born equal: distinct patterns induced by stress in Arabidopsis. Planta. 2014;240:931–40. [CrossRef]

- Fraser CM, Thompson MG, Shirley AM, Ralph J, Schoenherr JA, Sinlapadech T, et al. Related Arabidopsis Serine Carboxypeptidase-Like Sinapoylglucose Acyltransferases Display Distinct But Overlapping Substrate Specificities. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1986–99. [CrossRef]

- Ford CM, Boss PK, Høj PB. Cloning and Characterization of Vitis viniferaUDP-Glucose:Flavonoid 3-O-Glucosyltransferase, a Homologue of the Enzyme Encoded by the Maize Bronze-1Locus That May Primarily Serve to Glucosylate Anthocyanidins in Vivo *. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9224–33. [CrossRef]

- Kovinich N, Saleem A, Arnason JT, Miki B. Functional characterization of a UDP-glucose:flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase from the seed coat of black soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1253–63. [CrossRef]

- Modolo LV, Blount JW, Achnine L, Naoumkina MA, Wang X, Dixon RA. A functional genomics approach to (iso)flavonoid glycosylation in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;64:499–518. [CrossRef]

- Modolo LV, Li L, Pan H, Blount JW, Dixon RA, Wang X. Crystal Structures of Glycosyltransferase UGT78G1 Reveal the Molecular Basis for Glycosylation and Deglycosylation of (Iso)flavonoids. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:1292–302. [CrossRef]

- Jonsson LMV, Aarsman MEG, van Diepen J, de Vlaming P, Smit N, Schram AW. Properties and genetic control of anthocyanin 5-O-glucosyltransferase in flowers of Petunia hybrida. Planta. 1984;160:341–7. [CrossRef]

- Ogata J u. n., Sakamoto T, Yamaguchi M, Kawanobu S, Yoshitama K. Isolation and characterization of anthocyanin 5-O-glucosyltransferase from flowers of Dahlia variabilis. J Plant Physiol. 2001;158:709–14. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki M, Yamagishi E, Gong Z, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Fukui Y, Tanaka Y, et al. Two flavonoid glucosyltransferases from Petunia hybrida: molecular cloning, biochemical properties and developmentally regulated expression. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:401–11. [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuka T, Sato K, Takahashi H, Yamamura S, Nishihara M. Cloning and characterization of the UDP-glucose:anthocyanin 5-O-glucosyltransferase gene from blue-flowered gentian. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:1241–52. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Ji K, Liang B, Du Y, Jiang L, Wang J, et al. Suppressing ABA uridine diphosphate glucosyltransferase (SlUGT75C1) alters fruit ripening and the stress response in tomato. Plant J. 2017;91:574–89. [CrossRef]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Tohge T, Matsuda F, Nakabayashi R, Takayama H, Niida R, et al. Comprehensive Flavonol Profiling and Transcriptome Coexpression Analysis Leading to Decoding Gene–Metabolite Correlations in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2160–76. [CrossRef]

- Matsuba Y, Sasaki N, Tera M, Okamura M, Abe Y, Okamoto E, et al. A Novel Glucosylation Reaction on Anthocyanins Catalyzed by Acyl-Glucose–Dependent Glucosyltransferase in the Petals of Carnation and Delphinium[C][W]. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3374–89. [CrossRef]

- Miyahara T, Takahashi M, Ozeki Y, Sasaki N. Isolation of an acyl-glucose-dependent anthocyanin 7-O-glucosyltransferase from the monocot Agapanthus africanus. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169:1321–6. [CrossRef]

- Montefiori M, Comeskey DJ, Wohlers M, McGhie TK. Characterization and Quantification of Anthocyanins in Red Kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.). J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:6856–61. [CrossRef]

- Mato M, Ozeki Y, Itoh Y, Higeta D, Yoshitama K, Teramoto S, et al. Isolation and Characterization of a cDNA Clone of UDP-Galactose: Flavonoid 3-0-Galactosyltransferase (UF3GaT) Expressed in Vigna mungo Seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:1145–55. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z-S, Ma J, Wang F, Ma H-Y, Wang Q-X, Xiong A-S. Identification and characterization of DcUCGalT1, a galactosyltransferase responsible for anthocyanin galactosylation in purple carrot (Daucus carota L.) taproots. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27356. [CrossRef]

- Feng K, Xu Z-S, Liu J-X, Li J-W, Wang F, Xiong A-S. Isolation, purification, and characterization of AgUCGalT1, a galactosyltransferase involved in anthocyanin galactosylation in purple celery (Apium graveolens L.). Planta. 2018;247:1363–75. [CrossRef]

- Harborne JB. Anthocyanins and their Sugar Components. In: Zechmeister L, editor. Fortschritte der Chemie Organischer Naturstoffe / Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products / Progrès dans la Chimie des Substances Organiques Naturelles. Vienna: Springer; 1962. p. 165–99. [CrossRef]

- Tatsuzawa F, Saito N, Murata N, Shinoda K, Shigihara A, Honda T. 6-Hydroxypelargonidin glycosides in the orange–red flowers of Alstroemeria. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:1239–42. [CrossRef]

- Kamsteeg J, Brederode J van, Nigtevecht G van. Identification, Properties and Genetic Control of UDP-ʟ-Rhamnose: Anthocyanidin 3-O-Glucoside, 6″-O-Rhamnosyltransferase Isolated from Retals of the Red Campion (Silene dioica). Z Für Naturforschung C. 1980;35:249–57. [CrossRef]

- Brugliera F, Holton TA, Stevenson TW, Farcy E, Lu C-Y, Cornish EC. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone corresponding to the Rt locus of Petunia hybrida. Plant J. 1994;5:81–92. [CrossRef]

- Kroon J, Souer E, De Graaff A, Xue Y, Mol J, Koes R. Cloning and structural analysis of the anthocyanin pigmentation locus Rt of Petunia hybrida: characterization of insertion sequences in two mutant alleles. Plant J. 1994;5:69–80. [CrossRef]

- Frydman A, Liberman R, Huhman DV, Carmeli-Weissberg M, Sapir-Mir M, Ophir R, et al. The molecular and enzymatic basis of bitter/non-bitter flavor of citrus fruit: evolution of branch-forming rhamnosyltransferases under domestication. Plant J. 2013;73:166–78. [CrossRef]

- Frydman A, Weisshaus O, Bar-Peled M, Huhman DV, Sumner LW, Marin FR, et al. Citrus fruit bitter flavors: isolation and functional characterization of the gene Cm1,2RhaT encoding a 1,2 rhamnosyltransferase, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of the bitter flavonoids of citrus. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2004;40:88–100. [CrossRef]

- Hsu Y-H, Tagami T, Matsunaga K, Okuyama M, Suzuki T, Noda N, et al. Functional characterization of UDP-rhamnose-dependent rhamnosyltransferase involved in anthocyanin modification, a key enzyme determining blue coloration in Lobelia erinus. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2017;89:325–37. [CrossRef]

- Miyahara T, Sakiyama R, Ozeki Y, Sasaki N. Acyl-glucose-dependent glucosyltransferase catalyzes the final step of anthocyanin formation in Arabidopsis. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170:619–24. [CrossRef]

- Frommann J-F, Pucker B, Sielmann LM, Müller C, Weisshaar B, Stracke R, et al. Metabolic fingerprinting reveals roles of Arabidopsis thaliana BGLU1, BGLU3 and BGLU4 in glycosylation of various flavonoids. 2024;:2024.01.30.577901. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara H, Tohge T, Viehöver P, Fernie AR, Weisshaar B, Stracke R. Natural variation in flavonol accumulation in Arabidopsis is determined by the flavonol glucosyltransferase BGLU6. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:1505–17. [CrossRef]

- Jokioja J, Yang B, Linderborg KM. Acylated anthocyanins: A review on their bioavailability and effects on postprandial carbohydrate metabolism and inflammation. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021;20:5570–615. [CrossRef]

- Jaakola L. New insights into the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in fruits. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:477–83. [CrossRef]

- Albert NW, Davies KM, Lewis DH, Zhang H, Montefiori M, Brendolise C, et al. A conserved network of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates anthocyanin pigmentation in eudicots. Plant Cell. 2014;26:962–80. [CrossRef]

- LaFountain AM, Yuan Y-W. Repressors of anthocyanin biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2021;231:933–49. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay NA, Glover BJ. MYB-bHLH-WD40 protein complex and the evolution of cellular diversity. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:63–70. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez A, Zhao M, Leavitt JM, Lloyd AM. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2008;53:814–27. [CrossRef]

- Hichri I, Barrieu F, Bogs J, Kappel C, Delrot S, Lauvergeat V. Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:2465–83. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez A, Brown M, Hatlestad G, Akhavan N, Smith T, Hembd A, et al. TTG2 controls the developmental regulation of seed coat tannins in Arabidopsis by regulating vacuolar transport steps in the proanthocyanidin pathway. Dev Biol. 2016;419:54–63. [CrossRef]

- Chandler VL, Radicella JP, Robbins TP, Chen J, Turks D. Two regulatory genes of the maize anthocyanin pathway are homologous: isolation of B utilizing R genomic sequences. Plant Cell. 1989;1:1175–83. [CrossRef]

- Cone KC, Burr FA, Burr B. Molecular analysis of the maize anthocyanin regulatory locus C1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:9631–5. [CrossRef]

- Stracke R, Werber M, Weisshaar B. The R2R3-MYB gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:447–56. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd AM, Walbot V, Davis RW. Arabidopsis and Nicotiana Anthocyanin Production Activated by Maize Regulators R and C1. Science. 1992;258:1773–5. [CrossRef]

- Busche M, Pucker B, Weisshaar B, Stracke R. Three R2R3-MYB transcription factors from banana (Musa acuminata) activate structural anthocyanin biosynthesis genes as part of an MBW complex. BMC Res Notes. 2023;16:103. [CrossRef]

- Pesch M, Dartan B, Birkenbihl R, Somssich IE, Hülskamp M. Arabidopsis TTG2 Regulates TRY Expression through Enhancement of Activator Complex-Triggered Activation. Plant Cell. 2014;26:4067–83. [CrossRef]

- Verweij W, Spelt CE, Bliek M, de Vries M, Wit N, Faraco M, et al. Functionally Similar WRKY Proteins Regulate Vacuolar Acidification in Petunia and Hair Development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2016;28:786–803. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd A, Brockman A, Aguirre L, Campbell A, Bean A, Cantero A, et al. Advances in the MYB–bHLH–WD Repeat (MBW) Pigment Regulatory Model: Addition of a WRKY Factor and Co-option of an Anthocyanin MYB for Betalain Regulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58:1431–41. [CrossRef]

- An J-P, Zhang X-W, You C-X, Bi S-Q, Wang X-F, Hao Y-J. MdWRKY40 promotes wounding-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in association with MdMYB1 and undergoes MdBT2-mediated degradation. New Phytol. 2019;224:380–95. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Wu J, Hu K-D, Wei S-W, Sun H-Y, Hu L-Y, et al. PyWRKY26 and PybHLH3 cotargeted the PyMYB114 promoter to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis and transport in red-skinned pears. Hortic Res. 2020;7:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Karppinen K, Lafferty DJ, Albert NW, Mikkola N, McGhie T, Allan AC, et al. MYBA and MYBPA transcription factors co-regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in blue-coloured berries. New Phytol. 2021;232:1350–67. [CrossRef]

- Cavallini E, Zenoni S, Finezzo L, Guzzo F, Zamboni A, Avesani L, et al. Functional Diversification of Grapevine MYB5a and MYB5b in the Control of Flavonoid Biosynthesis in a Petunia Anthocyanin Regulatory Mutant. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:517–34. [CrossRef]

- Jiang L, Yue M, Liu Y, Zhang N, Lin Y, Zhang Y, et al. A novel R2R3-MYB transcription factor FaMYB5 positively regulates anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in cultivated strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa). Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21:1140–58. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Dong Y, Li D, Shi S, Zhao N, Liao J, et al. Eggplant transcription factor SmMYB5 integrates jasmonate and light signaling during anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2024;194:1139–65. [CrossRef]

- Walker AR, Lee E, Robinson SP. Two new grape cultivars, bud sports of Cabernet Sauvignon bearing pale-coloured berries, are the result of deletion of two regulatory genes of the berry colour locus. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;62:623–35. [CrossRef]

- Azuma A, Kobayashi S, Yakushui H, Yamada M, Mitani N, Sato A. VvmybA1 genotype determines grape skin color. VITIS - J Grapevine Res. 2007;46:154–154. [CrossRef]

- Jiu S, Guan L, Leng X, Zhang K, Haider MS, Yu X, et al. The role of VvMYBA2r and VvMYBA2w alleles of the MYBA2 locus in the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis for molecular breeding of grape (Vitis spp.) skin coloration. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19:1216–39. [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchio F, Verweij W, Kroon A, Spelt C, Mol J, Koes R. PH4 of Petunia is an R2R3 MYB protein that activates vacuolar acidification through interactions with basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factors of the anthocyanin pathway. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1274–91. [CrossRef]

- Zheng X, Om K, Stanton KA, Thomas D, Cheng PA, Eggert A, et al. The regulatory network for petal anthocyanin pigmentation is shaped by the MYB5a/NEGAN transcription factor in Mimulus. Genetics. 2021;217. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Huang K, Zheng G, Hou H, Wang P, Jiang H, et al. CsMYB5a and CsMYB5e from Camellia sinensis differentially regulate anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2018;270:209–20. [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Yang T, Li Y, Zhang J, Wu T, Song T, et al. The long noncoding RNA MdLNC499 bridges MdWRKY1 and MdERF109 function to regulate early-stage light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in apple fruit. Plant Cell. 2021;33:3309–30. [CrossRef]

- Yao G, Ming M, Allan AC, Gu C, Li L, Wu X, et al. Map-based cloning of the pear gene MYB114 identifies an interaction with other transcription factors to coordinately regulate fruit anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant J. 2017;92:437–51. [CrossRef]

- Morishita T, Kojima Y, Maruta T, Nishizawa-Yokoi A, Yabuta Y, Shigeoka S. Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor, ANAC078, regulates flavonoid biosynthesis under high-light. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:2210–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Lin-Wang K, Wang H, Gu C, Dare AP, Espley RV, et al. Molecular genetics of blood-fleshed peach reveals activation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by NAC transcription factors. Plant J. 2015;82:105–21. [CrossRef]

- Jaakola L, Poole M, Jones MO, Kämäräinen-Karppinen T, Koskimäki JJ, Hohtola A, et al. A SQUAMOSA MADS Box Gene Involved in the Regulation of Anthocyanin Accumulation in Bilberry Fruits. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1619–29. [CrossRef]

- Shin DH, Choi M, Kim K, Bang G, Cho M, Choi S-B, et al. HY5 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by inducing the transcriptional activation of the MYB75/PAP1 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1543–7. [CrossRef]

- An J-P, Qu F-J, Yao J-F, Wang X-N, You C-X, Wang X-F, et al. The bZIP transcription factor MdHY5 regulates anthocyanin accumulation and nitrate assimilation in apple. Hortic Res. 2017;4:17023. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Su J, Zhu Y, Yao G, Allan AC, Ampomah-Dwamena C, et al. The involvement of PybZIPa in light-induced anthocyanin accumulation via the activation of PyUFGT through binding to tandem G-boxes in its promoter. Hortic Res. 2019;6:134. [CrossRef]

- Chang CJ, Li Y-H, Chen L-T, Chen W-C, Hsieh W-P, Shin J, et al. LZF1, a HY5-regulated transcriptional factor, functions in Arabidopsis de-etiolation. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2008;54:205–19. [CrossRef]

- Bai S, Saito T, Honda C, Hatsuyama Y, Ito A, Moriguchi T. An apple B-box protein, MdCOL11, is involved in UV-B- and temperature-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis. Planta. 2014;240:1051–62. [CrossRef]

- Kim D-H, Park S, Lee J-Y, Ha S-H, Lee J-G, Lim S-H. A Rice B-Box Protein, OsBBX14, Finely Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2190. [CrossRef]

- Bai S, Tao R, Tang Y, Yin L, Ma Y, Ni J, et al. BBX16, a B-box protein, positively regulates light-induced anthocyanin accumulation by activating MYB10 in red pear. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17:1985–97. [CrossRef]

- Shin J, Park E, Choi G. PIF3 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in an HY5-dependent manner with both factors directly binding anthocyanin biosynthetic gene promoters in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007;49:981–94. [CrossRef]

- Yoo J, Shin DH, Cho M-H, Kim T-L, Bhoo SH, Hahn T-R. An ankyrin repeat protein is involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Physiol Plant. 2011;142:314–25. [CrossRef]

- Lotkowska ME, Tohge T, Fernie AR, Xue G-P, Balazadeh S, Mueller-Roeber B. The Arabidopsis Transcription Factor MYB112 Promotes Anthocyanin Formation during Salinity and under High Light Stress. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:1862–80. [CrossRef]

- Mur LA. Characterization of Members of the myb Gene Family of Transcription Factors from Petunia hybrida. PhD Thesis. 1995.

- Aharoni A, De Vos CHR, Wein M, Sun Z, Greco R, Kroon A, et al. The strawberry FaMYB1 transcription factor suppresses anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in transgenic tobacco. Plant J. 2001;28:319–32. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H-F, Fitzsimmons K, Khandelwal A, Kranz RG. CPC, a single-repeat R3 MYB, is a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2009;2:790–802. [CrossRef]

- Gou J-Y, Felippes FF, Liu C-J, Weigel D, Wang J-W. Negative Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by a miR156-Targeted SPL Transcription Factor. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1512–22. [CrossRef]

- Dubos C, Le Gourrierec J, Baudry A, Huep G, Lanet E, Debeaujon I, et al. MYBL2 is a new regulator of flavonoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2008;55:940–53. [CrossRef]

- Cavallini E, Matus JT, Finezzo L, Zenoni S, Loyola R, Guzzo F, et al. The Phenylpropanoid Pathway Is Controlled at Different Branches by a Set of R2R3-MYB C2 Repressors in Grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:1448–70. [CrossRef]

- Xu F, Ning Y, Zhang W, Liao Y, Li L, Cheng H, et al. An R2R3-MYB transcription factor as a negative regulator of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in Ginkgo biloba. Funct Integr Genomics. 2014;14:177–89. [CrossRef]

- Deng G-M, Zhang S, Yang Q-S, Gao H-J, Sheng O, Bi F-C, et al. MaMYB4, an R2R3-MYB Repressor Transcription Factor, Negatively Regulates the Biosynthesis of Anthocyanin in Banana. Front Plant Sci. 2021;11.

- Franco-Zorrilla JM, Valli A, Todesco M, Mateos I, Puga MI, Rubio-Somoza I, et al. Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1033–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang G, Chen D, Zhang T, Duan A, Zhang J, He C. Transcriptomic and functional analyses unveil the role of long non-coding RNAs in anthocyanin biosynthesis during sea buckthorn fruit ripening. DNA Res. 2018;25:465–76. [CrossRef]

- Meng J, Wang H, Chi R, Qiao Y, Wei J, Zhang Y, et al. The eTM–miR858–MYB62-like module regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis under low-nitrogen conditions in Malus spectabilis. New Phytol. 2023;238:2524–44. [CrossRef]

- Bradley D, Xu P, Mohorianu I-I, Whibley A, Field D, Tavares H, et al. Evolution of flower color pattern through selection on regulatory small RNAs. Science. 2017;358:925–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Zhang X, Wang H, Ye M, Liu Y, Song Z, et al. Identification and Analysis of Long Non-Coding RNAs Related to UV-B-Induced Anthocyanin Biosynthesis During Blood-Fleshed Peach (Prunus persica) Ripening. Front Genet. 2022;13.

- Liu H, Shu Q, Lin-Wang K, Allan AC, Espley RV, Su J, et al. The PyPIF5-PymiR156a-PySPL9-PyMYB114/MYB10 module regulates light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in red pear. Mol Hortic. 2021;1:14. [CrossRef]

- Chialva C, Blein T, Crespi M, Lijavetzky D. Insights into long non-coding RNA regulation of anthocyanin carrot root pigmentation. Sci Rep. 2021;11:4093. [CrossRef]

- Pucker B, Selmar D. Biochemistry and Molecular Basis of Intracellular Flavonoid Transport in Plants. Plants Basel Switz. 2022;11:963. [CrossRef]

- Goodman CD, Casati P, Walbot V. A Multidrug Resistance–Associated Protein Involved in Anthocyanin Transport in Zea mays. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1812–26. [CrossRef]

- Francisco RM, Regalado A, Ageorges A, Burla BJ, Bassin B, Eisenach C, et al. ABCC1, an ATP binding cassette protein from grape berry, transports anthocyanidin 3-O-Glucosides. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1840–54. [CrossRef]

- Behrens CE, Smith KE, Iancu CV, Choe J, Dean JV. Transport of Anthocyanins and other Flavonoids by the Arabidopsis ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter AtABCC2. Sci Rep. 2019;9:437. [CrossRef]

- Ichino T, Fuji K, Ueda H, Takahashi H, Koumoto Y, Takagi J, et al. GFS9/TT9 contributes to intracellular membrane trafficking and flavonoid accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2014;80:410–23. [CrossRef]

- Marinova K, Pourcel L, Weder B, Schwarz M, Barron D, Routaboul J-M, et al. The Arabidopsis MATE transporter TT12 acts as a vacuolar flavonoid/H+ -antiporter active in proanthocyanidin-accumulating cells of the seed coat. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2023–38. [CrossRef]

- Appelhagen I, Nordholt N, Seidel T, Spelt K, Koes R, Quattrochio F, et al. TRANSPARENT TESTA 13 is a tonoplast P3A-ATPase required for vacuolar deposition of proanthocyanidins in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Plant J. 2015;82:840–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Dixon RA. MATE Transporters Facilitate Vacuolar Uptake of Epicatechin 3′-O-Glucoside for Proanthocyanidin Biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2323–40. [CrossRef]

- Mueller LA, Goodman CD, Silady RA, Walbot V. AN9, a Petunia Glutathione S-Transferase Required for Anthocyanin Sequestration, Is a Flavonoid-Binding Protein. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1561–70. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura S, Shikazono N, Tanaka A. TRANSPARENT TESTA 19 is involved in the accumulation of both anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in Arabidopsis. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2004;37:104–14. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Li H, Huang J-R. Arabidopsis TT19 Functions as a Carrier to Transport Anthocyanin from the Cytosol to Tonoplasts. Mol Plant. 2012;5:387–400. [CrossRef]

- Nozue M, Yamada K, Nakamura T, Kubo H, Kondo M, Nishimura M. Expression of a Vacuolar Protein (VP24) in Anthocyanin-Producing Cells of Sweet Potato in Suspension Culture. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1065–72. [CrossRef]

- Irani NG, Grotewold E. Light-induced morphological alteration in anthocyanin-accumulating vacuoles of maize cells. BMC Plant Biol. 2005;5:7. [CrossRef]

- Verweij W, Spelt C, Di Sansebastiano G-P, Vermeer J, Reale L, Ferranti F, et al. An H+ P-ATPase on the tonoplast determines vacuolar pH and flower colour. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1456–62. [CrossRef]

- Doody E, Moyroud E. Evolution of petal patterning: blooming floral diversity at the microscale. New Phytol. 2025;247:2538–56. [CrossRef]

- Hempel de Ibarra N, Holtze S, Bäucker C, Sprau P, Vorobyev M. The role of colour patterns for the recognition of flowers by bees. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2022;377:20210284. [CrossRef]

- Davies KM, Albert NW, Schwinn KE, Davies KM, Albert NW, Schwinn KE. From landing lights to mimicry: the molecular regulation of flower colouration and mechanisms for pigmentation patterning. Funct Plant Biol. 2012;39:619–38. [CrossRef]

- Richter R, Dietz A, Foster J, Spaethe J, Stöckl A. Flower patterns improve foraging efficiency in bumblebees by guiding approach flight and landing. Funct Ecol. 2023;37:763–77. [CrossRef]

- Owen CR, Bradshaw HD. Induced mutations affecting pollinator choice in Mimulus lewisii (Phrymaceae). Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2011;5:235–44. [CrossRef]

- Albert NW, Davies KM, Schwinn KE. Gene regulation networks generate diverse pigmentation patterns in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;9:e29526. [CrossRef]

- Ding B, Patterson EL, Holalu SV, Li J, Johnson GA, Stanley LE, et al. Two MYB Proteins in a Self-Organizing Activator-Inhibitor System Produce Spotted Pigmentation Patterns. Curr Biol CB. 2020;30:802-814.e8. [CrossRef]

- Shang Y, Venail J, Mackay S, Bailey PC, Schwinn KE, Jameson PE, et al. The molecular basis for venation patterning of pigmentation and its effect on pollinator attraction in flowers of Antirrhinum. New Phytol. 2011;189:602–15. [CrossRef]

- Chopy M, Cavallini-Speisser Q, Chambrier P, Morel P, Just J, Hugouvieux V, et al. Cell layer–specific expression of the homeotic MADS-box transcription factor PhDEF contributes to modular petal morphogenesis in petunia. Plant Cell. 2024;36:324–45. [CrossRef]

- Abid MA, Wei Y, Meng Z, Wang Y, Ye Y, Wang Y, et al. Increasing floral visitation and hybrid seed production mediated by beauty mark in Gossypium hirsutum. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022;20:1274–84. [CrossRef]

- Fattorini R, Khojayori FN, Mellers G, Moyroud E, Herrero E, Kellenberger RT, et al. Complex petal spot formation in the Beetle Daisy (Gorteria diffusa) relies on spot-specific accumulation of malonylated anthocyanin regulated by paralogous GdMYBSG6 transcription factors. New Phytol. 2024;n/a n/a. [CrossRef]

- Glover BJ, Walker RH, Moyroud E, Brockington SF. How to spot a flower. New Phytol. 2013;197:687–9. [CrossRef]

- Horz JM, Wolff K, Friedhoff R, Pucker B. Genome sequence of the ornamental plant Digitalis purpurea reveals the molecular basis of flower color and morphology variation. 2024;:2024.02.14.580303. [CrossRef]

- Turing AM. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1952;237:37–72. [CrossRef]

- Gierer A, Meinhardt H. A theory of biological pattern formation. Kybernetik. 1972;12:30–9. [CrossRef]

- Koseki M, Goto K, Masuta C, Kanazawa A. The Star-type Color Pattern in Petunia hybrida ‘Red Star’ Flowers is Induced by Sequence-Specific Degradation of Chalcone Synthase RNA. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:1879–83. [CrossRef]

- Lee DW, Collins TM. Phylogenetic and Ontogenetic Influences on the Distribution of Anthocyanins and Betacyanins in Leaves of Tropical Plants. Int J Plant Sci. 2001;162:1141–53. [CrossRef]

- Gould KS. Nature’s Swiss Army Knife: The Diverse Protective Roles of Anthocyanins in Leaves. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2004;2004:314–20. [CrossRef]

- Shi M-Z, Xie D-Y. Features of anthocyanin biosynthesis in pap1-D and wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana plants grown in different light intensity and culture media conditions. Planta. 2010;231:1385–400. [CrossRef]

- Mark Hodges D, Nozzolillo C. Anthocyanin and Anthocyanoplast Content of Cruciferous Seedlings Subjected to Mineral Nutrient Deficiencies. J Plant Physiol. 1996;147:749–54. [CrossRef]

- Landi M, Tattini M, Gould KS. Multiple functional roles of anthocyanins in plant-environment interactions. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;119:4–17. [CrossRef]

- Weiss MR. Floral colour changes as cues for pollinators. Nature. 1991;354:227–9. [CrossRef]

- Willmer P, Stanley DA, Steijven K, Matthews IM, Nuttman CV. Bidirectional flower color and shape changes allow a second opportunity for pollination. Curr Biol CB. 2009;19:919–23. [CrossRef]

- Ruxton GD, Schaefer HM. Floral colour change as a potential signal to pollinators. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;32:96–100. [CrossRef]

- Garcia JE, Hannah L, Shrestha M, Burd M, Dyer AG. Fly pollination drives convergence of flower coloration. New Phytol. 2022;233:52–61. [CrossRef]

- Dellinger AS, Meier L, Smith S, Sinnott-Armstrong M. Does the abiotic environment influence the distribution of flower and fruit colors? Am J Bot. 2025;n/a n/a:e70044. [CrossRef]

- Narbona E, Arista M, Whittall JB, Camargo MGG, Shrestha M. Editorial: The Role of Flower Color in Angiosperm Evolution. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:736998. [CrossRef]

- Albert NW, Lewis DH, Zhang H, Irving LJ, Jameson PE, Davies KM. Light-induced vegetative anthocyanin pigmentation in Petunia. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:2191–202. [CrossRef]

- Araguirang GE, Richter AS. Activation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in high light – what is the initial signal? New Phytol. 2022;236:2037–43. [CrossRef]

- Gould KS, Kuhn DN, Lee DW, Oberbauer SF. Why leaves are sometimes red. Nature. 1995;378:241–2. [CrossRef]

- Chalker-Scott L. Environmental Significance of Anthocyanins in Plant Stress Responses. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;70:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Logan BA, Stafstrom WC, Walsh MJL, Reblin JS, Gould KS. Examining the photoprotection hypothesis for adaxial foliar anthocyanin accumulation by revisiting comparisons of green- and red-leafed varieties of coleus (Solenostemon scutellarioides). Photosynth Res. 2015;124:267–74. [CrossRef]

- Smillie RM, Hetherington SE. Photoabatement by Anthocyanin Shields Photosynthetic Systems from Light Stress. Photosynthetica. 1999;36:451–63. [CrossRef]

- Neill S, Gould KS. Optical properties of leaves in relation to anthocyanin concentration and distribution. Can J Bot. 2000;77:1777–82. [CrossRef]

- Landi M, Agati G, Fini A, Guidi L, Sebastiani F, Tattini M. Unveiling the shade nature of cyanic leaves: A view from the “blue absorbing side” of anthocyanins. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44:1119–29. [CrossRef]

- Feild TS, Lee DW, Holbrook NM. Why Leaves Turn Red in Autumn. The Role of Anthocyanins in Senescing Leaves of Red-Osier Dogwood. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:566–74.

- Agati G, Guidi L, Landi M, Tattini M. Anthocyanins in photoprotection: knowing the actors in play to solve this complex ecophysiological issue. New Phytol. 2021;232:2228–35. [CrossRef]

- Manetas Y, Petropoulou Y, Psaras GK, Drinia A. Exposed red (anthocyanic) leaves of Quercus coccifera display shade characteristics. Funct Plant Biol FPB. 2003;30:265–70. [CrossRef]

- Hughes NM, Vogelmann TC, Smith WK. Optical effects of abaxial anthocyanin on absorption of red wavelengths by understorey species: revisiting the back-scatter hypothesis. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:3435–42. [CrossRef]

- Gould KS, McKelvie J, Markham KR. Do anthocyanins function as antioxidants in leaves? Imaging of H2O2 in red and green leaves after mechanical injury. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:1261–9. [CrossRef]

- Kytridis V-P, Manetas Y. Mesophyll versus epidermal anthocyanins as potential in vivo antioxidants: evidence linking the putative antioxidant role to the proximity of oxy-radical source. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:2203–10. [CrossRef]

- Yabuta Y, Motoki T, Yoshimura K, Takeda T, Ishikawa T, Shigeoka S. Thylakoid membrane-bound ascorbate peroxidase is a limiting factor of antioxidative systems under photo-oxidative stress. Plant J. 2002;32:915–25. [CrossRef]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Spinach chloroplasts scavenge hydrogen peroxide on illumination. Plant Cell Physiol. 1980;21:1295–307. [CrossRef]

- Bienert GP, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:994–1003. [CrossRef]

- Agati G, Brunetti C, Di Ferdinando M, Ferrini F, Pollastri S, Tattini M. Functional roles of flavonoids in photoprotection: new evidence, lessons from the past. Plant Physiol Biochem PPB. 2013;72:35–45. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki H, Sakihama Y, Ikehara N. Flavonoid-Peroxidase Reaction as a Detoxification Mechanism of Plant Cells against H2O2. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1405–12. [CrossRef]

- Gould KS, Neill SO, Vogelmann TC. A unified explanation for anthocyanins in leaves? In: Advances in Botanical Research. Academic Press; 2002. p. 167–92. [CrossRef]

- Gould KS, Jay-Allemand C, Logan BA, Baissac Y, Bidel LPR. When are foliar anthocyanins useful to plants? Re-evaluation of the photoprotection hypothesis using Arabidopsis thaliana mutants that differ in anthocyanin accumulation. Environ Exp Bot. 2018;154:11–22. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z, Rothstein SJ. ROS-Induced anthocyanin production provides feedback protection by scavenging ROS and maintaining photosynthetic capacity in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2018;13:e1451708. [CrossRef]

- Gould KS, Dudle DA, Neufeld HS. Why some stems are red: cauline anthocyanins shield photosystem II against high light stress. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:2707–17. [CrossRef]

- Christie PJ, Alfenito MR, Walbot V. Impact of low-temperature stress on general phenylpropanoid and anthocyanin pathways: Enhancement of transcript abundance and anthocyanin pigmentation in maize seedlings. Planta. 1994;194:541–9. [CrossRef]

- Dodd IC, Critchley C, Woodall GS, Stewart GR. Photoinhibition in differently coloured juvenile leaves of Syzygium species. J Exp Bot. 1998;49:1437–45. [CrossRef]

- Merzlyak MN, Chivkunova OB. Light-stress-induced pigment changes and evidence for anthocyanin photoprotection in apples. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2000;55:155–63. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Huang Z, Tang L. Invisible red in young leaves: Anthocyanin likely plays a defensive role in some other way beyond visual warning. Flora. 2021;280:151833. [CrossRef]

- Krause GH, Virgo A, Winter K. High susceptibility to photoinhibition of young leaves of tropical forest trees. Planta. 1995;197:583–91. [CrossRef]

- Karageorgou P, Manetas Y. The importance of being red when young: anthocyanins and the protection of young leaves of Quercus coccifera from insect herbivory and excess light. Tree Physiol. 2006;26:613–21. [CrossRef]

- Matile Ph, Flach BM-P, Eller BM. Autumn Leaves of Ginkgo biloba L.: Optical Properties, Pigments and Optical Brighteners. Bot Acta. 1992;105:13–7. [CrossRef]

- Archetti M. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a scattered distribution of autumn colours. Ann Bot. 2009;103:703–13. [CrossRef]

- Archetti M, Döring TF, Hagen SB, Hughes NM, Leather SR, Lee DW, et al. Unravelling the evolution of autumn colours: an interdisciplinary approach. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:166–73. [CrossRef]

- Renner SS, Zohner CM. The occurrence of red and yellow autumn leaves explained by regional differences in insolation and temperature. New Phytol. 2019;224:1464–71. [CrossRef]

- Hoch WA, Zeldin EL, McCown BH. Physiological significance of anthocyanins during autumnal leaf senescence. Tree Physiol. 2001;21:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Lee DW, O’Keefe J, Holbrook NM, Feild TS. Pigment dynamics and autumn leaf senescence in a New England deciduous forest, eastern USA. Ecol Res. 2003;18:677–94. [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi R, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Urano K, Suzuki M, Yamada Y, Nishizawa T, et al. Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J. 2014;77:367–79. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Jiang W, Li C, Wang Z, Lu C, Cheng J, et al. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses elucidate the mechanism of flavonoid biosynthesis in the regulation of mulberry seed germination under salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24:132. [CrossRef]

- Feng X, Bai S, Zhou L, Song Y, Jia S, Guo Q, et al. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptome and Metabolome Provides Insights into Flavonoid Biosynthesis of Blueberry Leaves in Response to Drought Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:11135. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Miao Y, Ayyaz A, Huang Q, Hannan F, Zou H-X, et al. Anthocyanin accumulation enhances drought tolerance in purple-leaf Brassica napus: Transcriptomic, metabolomic, and physiological evidence. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;223:120149. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Li Y-J, Zhang F-J, Zhang G-Z, Jiang X-Y, Yu H-M, et al. The Arabidopsis UDP-glycosyltransferases UGT79B2 and UGT79B3, contribute to cold, salt and drought stress tolerance via modulating anthocyanin accumulation. Plant J. 2017;89:85–103. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Fan R, Guo S, Wang P, Zhu X, Fan Y, et al. The Arabidopsis MYB transcription factor, MYB111 modulates salt responses by regulating flavonoid biosynthesis. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;166:103807. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary N, Pucker B. Conserved amino acid residues and gene expression patterns associated with the substrate preferences of the competing enzymes FLS and DFR. PLOS ONE. 2024;19:e0305837. [CrossRef]

- Saad KR, Kumar G, Mudliar SN, Giridhar P, Shetty NP. Salt Stress-Induced Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Genes and MATE Transporter Involved in Anthocyanin Accumulation in Daucus carota Cell Culture. ACS Omega. 2021;6:24502–14. [CrossRef]

- Manetas Y. Why some leaves are anthocyanic and why most anthocyanic leaves are red? Flora. 2006;3:163–77. [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski SA, Isayenkov SV. The Role of Anthocyanins in Plant Tolerance to Drought and Salt Stresses. Plants. 2023;12:2558. [CrossRef]

- Dassanayake M, Larkin JC. Making Plants Break a Sweat: the Structure, Function, and Evolution of Plant Salt Glands. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8. [CrossRef]

- Oberbaueri SF, Starr G. The role of anthocyanins for photosynthesis of Alaskan arctic evergreens during snowmelt. In: Advances in Botanical Research. Academic Press; 2002. p. 129–45. [CrossRef]

- Hughes NM, Neufeld HS, Burkey KO. Functional role of anthocyanins in high-light winter leaves of the evergreen herb Galax urceolata. New Phytol. 2005;168:575–87. [CrossRef]

- Stiles EW. Fruit Flags: Two Hypotheses. Am Nat. 1982;120:500–9.

- Lee DW. Anthocyanins in autumn leaf senescence. In: Advances in Botanical Research. Academic Press; 2002. p. 147–65. [CrossRef]

- Naing AH, Ai TN, Lim KB, Lee IJ, Kim CK. Overexpression of Rosea1 From Snapdragon Enhances Anthocyanin Accumulation and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Tobacco. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9. [CrossRef]

- Jezek M, Allan AC, Jones JJ, Geilfus C-M. Why do plants blush when they are hungry? New Phytol. 2023;239:494–505. [CrossRef]

- Lawanson AO, Akindele BB, Fasalojo PB, Akpe BL. Time-course of anthocyanin formation during deficiencies of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in seedlings of zea mays Linn. var. E.S. 1. Z Für Pflanzenphysiol. 1972;66:251–3. [CrossRef]

- Hajiboland R, Farhanghi F. Remobilization of boron, photosynthesis, phenolic metabolism and anti-oxidant defense capacity in boron-deficient turnip (Brassica rapa L.) plants. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2010;56:427–37. [CrossRef]

- D’Hooghe P, Escamez S, Trouverie J, Avice J-C. Sulphur limitation provokes physiological and leaf proteome changes in oilseed rape that lead to perturbation of sulphur, carbon and oxidative metabolisms. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:23. [CrossRef]

- Tavares S, Vesentini D, Fernandes JC, Ferreira RB, Laureano O, Ricardo-Da-Silva JM, et al. Vitis vinifera secondary metabolism as affected by sulfate depletion: diagnosis through phenylpropanoid pathway genes and metabolites. Plant Physiol Biochem PPB. 2013;66:118–26. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi NI, Saito T, Iwata N, Ohmae Y, Iwata R, Tanoi K, et al. Leaf senescence in rice due to magnesium deficiency mediated defect in transpiration rate before sugar accumulation and chlorosis. Physiol Plant. 2013;148:490–501. [CrossRef]

- Naya L, Paul S, Valdés-López O, Mendoza-Soto AB, Nova-Franco B, Sosa-Valencia G, et al. Regulation of copper homeostasis and biotic interactions by microRNA 398b in common bean. PloS One. 2014;9:e84416. [CrossRef]

- Kaur S, Kumari A, Sharma N, Pandey AK, Garg M. Physiological and molecular response of colored wheat seedlings against phosphate deficiency is linked to accumulation of distinct anthocyanins. Plant Physiol Biochem PPB. 2022;170:338–49. [CrossRef]

- Wang T-J, Huang S, Zhang A, Guo P, Liu Y, Xu C, et al. JMJ17-WRKY40 and HY5-ABI5 modules regulate the expression of ABA-responsive genes in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2021;230:567–84. [CrossRef]

- Teng S, Keurentjes J, Bentsink L, Koornneef M, Smeekens S. Sucrose-Specific Induction of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis Requires the MYB75/PAP1 Gene. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1840–52. [CrossRef]

- Solfanelli C, Poggi A, Loreti E, Alpi A, Perata P. Sucrose-specific induction of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:637–46. [CrossRef]

- Weiss D. Regulation of flower pigmentation and growth: Multiple signaling pathways control anthocyanin synthesis in expanding petals. Physiol Plant. 2000;110:152–7. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd JC, Zakhleniuk OV. Responses of primary and secondary metabolism to sugar accumulation revealed by microarray expression analysis of the Arabidopsis mutant, pho3. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:1221–30. [CrossRef]

- Loreti E, Povero G, Novi G, Solfanelli C, Alpi A, Perata P. Gibberellins, jasmonate and abscisic acid modulate the sucrose-induced expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2008;179:1004–16. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Van den Ende W, Rolland F. Sucrose induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis is mediated by DELLA. Mol Plant. 2014;7:570–2. [CrossRef]

- Waterman PG, Ross JA, McKey DB. Factors affecting levels of some phenolic compounds, digestibility, and nitrogen content of the mature leaves of Barteria fistulosa (Passifloraceae). J Chem Ecol. 1984;10:387–401. [CrossRef]

- Lo Piccolo E, Landi M, Pellegrini E, Agati G, Giordano C, Giordani T, et al. Multiple Consequences Induced by Epidermally-Located Anthocyanins in Young, Mature and Senescent Leaves of Prunus. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9. [CrossRef]

- Zirngibl M-E, Araguirang GE, Kitashova A, Jahnke K, Rolka T, Kühn C, et al. Triose phosphate export from chloroplasts and cellular sugar content regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis during high light acclimation. Plant Commun. 2023;4:100423. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Man C, Li D, Tan H, Xie Y, Huang J. Arogenate Dehydratase Isoforms Differentially Regulate Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2016;9:1609–19. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, Sharma SS. Nutrient Deficiency-dependent Anthocyanin Development in Spirodela Polyrhiza L. Schleid. Biol Plant. 1999;42:621–4. [CrossRef]

- Neill SO, Gould KS, Kilmartin PA, Mitchell KA, Markham KR. Antioxidant activities of red versus green leaves in Elatostema rugosum. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:539–47. [CrossRef]

- Mollier A, Pellerin S. Maize root system growth and development as influenced by phosphorus deficiency. J Exp Bot. 1999;50:487–97. [CrossRef]

- Henry A, Chopra S, Clark DG, Lynch JP. Responses to low phosphorus in high and low foliar anthocyanin coleus (Solenostemon scutellarioides) and maize (Zea mays). Funct Plant Biol. 2012;39:255–65. [CrossRef]

- Sivitz AB, Reinders A, Ward JM. Arabidopsis Sucrose Transporter AtSUC1 Is Important for Pollen Germination and Sucrose-Induced Anthocyanin Accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:92–100. [CrossRef]

- Jeong S-W, Das PK, Jeoung SC, Song J-Y, Lee HK, Kim Y-K, et al. Ethylene Suppression of Sugar-Induced Anthocyanin Pigmentation in Arabidopsis1. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1514–31. [CrossRef]

- Meng L-S, Xu M-K, Wan W, Yu F, Li C, Wang J-Y, et al. Sucrose Signaling Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Through a MAPK Cascade in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2018;210:607–19. [CrossRef]

- Lasin P, Weise A, Reinders A, Ward JM. Arabidopsis Sucrose Transporter AtSuc1 introns act as strong enhancers of expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020;61:1054–63. [CrossRef]

- Kranz HD, Denekamp M, Greco R, Jin H, Leyva A, Meissner RC, et al. Towards functional characterisation of the members of the R2R3-MYB gene family from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 1998;16:263–76. [CrossRef]

- Broeckling BE, Watson RA, Steinwand B, Bush DR. Intronic Sequence Regulates Sugar-Dependent Expression of Arabidopsis thaliana Production of Anthocyanin Pigment-1/MYB75. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0156673. [CrossRef]

- Harmer SL, Hogenesch JB, Straume M, Chang HS, Han B, Zhu T, et al. Orchestrated transcription of key pathways in Arabidopsis by the circadian clock. Science. 2000;290:2110–3. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, He J, Zhang Y, Zhao H, Sun X, Chen X, et al. RHA2b-mediated MYB30 degradation facilitates MYB75-regulated, sucrose-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Commun. 2024;5:100744. [CrossRef]

- Broucke E, Dang TTV, Li Y, Hulsmans S, Van Leene J, De Jaeger G, et al. SnRK1 inhibits anthocyanin biosynthesis through both transcriptional regulation and direct phosphorylation and dissociation of the MYB/bHLH/TTG1 MBW complex. Plant J. 2023;115:1193–213. [CrossRef]

- Liang J, He J. Protective role of anthocyanins in plants under low nitrogen stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498:946–53. [CrossRef]

- Zhou L-L, Shi M-Z, Xie D-Y. Regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by nitrogen in TTG1-GL3/TT8-PAP1-programmed red cells of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2012;236:825–37. [CrossRef]

- Lea US, Slimestad R, Smedvig P, Lillo C. Nitrogen deficiency enhances expression of specific MYB and bHLH transcription factors and accumulation of end products in the flavonoid pathway. Planta. 2007;225:1245–53. [CrossRef]

- Peng M, Bi Y-M, Zhu T, Rothstein SJ. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis responsive transcriptome to nitrogen limitation and its regulation by the ubiquitin ligase gene NLA. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;65:775–97. [CrossRef]

- Koeslin-Findeklee F, Rizi VS, Becker MA, Parra-Londono S, Arif M, Balazadeh S, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of nitrogen starvation- and cultivar-specific leaf senescence in winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). Plant Sci Int J Exp Plant Biol. 2015;233:174–85. [CrossRef]

- Barker A, Pilbeam D. Handbook of plant nutrition. 2015.

- Kalaji HM, Bąba W, Gediga K, Goltsev V, Samborska IA, Cetner MD, et al. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool for nutrient status identification in rapeseed plants. Photosynth Res. 2018;136:329–43. [CrossRef]

- Jezek M, Zörb C, Merkt N, Geilfus C-M. Anthocyanin Management in Fruits by Fertilization. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:753–64. [CrossRef]

- Wolff K, Pucker B. Dark side of anthocyanin pigmentation. Plant Biol. n/a n/a. [CrossRef]

- Miller R, Owens SJ, Rørslett B. Plants and colour: Flowers and pollination. Opt Laser Technol. 2011;43:282–94. [CrossRef]

- Rausher MD. Evolutionary Transitions in Floral Color. Int J Plant Sci. 2008;169:7–21. [CrossRef]

- Van der Niet T, Peakall R, Johnson SD. Pollinator-driven ecological speciation in plants: new evidence and future perspectives. Ann Bot. 2014;113:199–212. [CrossRef]

- Gervasi DDL, Schiestl FP. Real-time divergent evolution in plants driven by pollinators. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14691. [CrossRef]

- Lunau K, Maier EJ. Innate colour preferences of flower visitors. J Comp Physiol A. 1995;177:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Hoballah ME, Gübitz T, Stuurman J, Broger L, Barone M, Mandel T, et al. Single Gene–Mediated Shift in Pollinator Attraction in Petunia. Plant Cell. 2007;19:779–90. [CrossRef]

- Smith SD. Using phylogenetics to detect pollinator-mediated floral evolution. New Phytol. 2010;188:354–63. [CrossRef]

- Reverté S, Retana J, Gómez JM, Bosch J. Pollinators show flower colour preferences but flowers with similar colours do not attract similar pollinators. Ann Bot. 2016;118:249–57. [CrossRef]

- Narbona E, Perfectti F, González-Megías A, Navarro L, del Valle JC, Armas C, et al. Heat drastically alters floral color and pigment composition without affecting flower conspicuousness. Am J Bot. 2025;n/a n/a:e70096. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan H, Moser M, Klahre U, Esfeld K, Dell’Olivo A, Mandel T, et al. MYB-FL controls gain and loss of floral UV absorbance, a key trait affecting pollinator preference and reproductive isolation. Nat Genet. 2016;48:159–66. [CrossRef]

- Stoddard MC, Eyster HN, Hogan BG, Morris DH, Soucy ER, Inouye DW. Wild hummingbirds discriminate nonspectral colors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:15112–22. [CrossRef]

- Briscoe AD, Chittka L. THE EVOLUTION OF COLOR VISION IN INSECTS. Annu Rev Entomol. 2001;46 Volume 46, 2001:471–510. [CrossRef]

- Kelber A, Vorobyev M, Osorio D. Animal colour vision--behavioural tests and physiological concepts. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2003;78:81–118. [CrossRef]

- Delph LF, Lively CM. THE EVOLUTION OF FLORAL COLOR CHANGE: POLLINATOR ATTRACTION VERSUS PHYSIOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS IN FUCHSIA EXCORTICATA. Evol Int J Org Evol. 1989;43:1252–62. [CrossRef]

- Oberrath R, Böhning-Gaese K. Floral color change and the attraction of insect pollinators in lungwort (Pulmonaria collina). Oecologia. 1999;121:383–91. [CrossRef]

- Nowak MS, Harder B, Meckoni SN, Friedhoff R, Wolff K, Pucker B. Genome sequence and RNA-seq analysis reveal genetic basis of flower coloration in the giant water lily Victoria cruziana. bioRxiv. 2024;:2024.06.15.599162. [CrossRef]

- Narbona E, del Valle JC, Arista M, Buide ML, Ortiz PL. Major Flower Pigments Originate Different Colour Signals to Pollinators. Front Ecol Evol. 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Rudall PJ. Colourful cones: how did flower colour first evolve? J Exp Bot. 2020;71:759–67. [CrossRef]

- Albert NW, Iorizzo M, Mengist MF, Montanari S, Zalapa J, Maule A, et al. Vaccinium as a comparative system for understanding of complex flavonoid accumulation profiles and regulation in fruit. Plant Physiol. 2023;192:1696–710. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer HM, McGraw K, Catoni C. Birds use fruit colour as honest signal of dietary antioxidant rewards. Funct Ecol. 2008;22:303–10. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer HM, Ruxton GD. Plant-Animal Communication. Oxford University Press; 2011. [CrossRef]

- Steyn WJ. Prevalence and Functions of Anthocyanins in Fruits. In: Winefield C, Davies K, Gould K, editors. Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. p. 86–105. [CrossRef]

- Turcek F. Color preference in fruit- and seed-eating birds. Proc Int Ornithol Congr. 1963;13:285–92.

- Renoult JP, Valido A, Jordano P, Schaefer HM. Adaptation of flower and fruit colours to multiple, distinct mutualists. New Phytol. 2014;201:678–86. [CrossRef]

- Ridley HN. The Dispersal Of Plants Throughout The World. Kent: L. REEVE & CO., LTD; 1930.

- Alabd A, Ahmad M, Zhang X, Gao Y, Peng L, Zhang L, et al. Light-responsive transcription factor PpWRKY44 induces anthocyanin accumulation by regulating PpMYB10 expression in pear. Hortic Res. 2022;9:uhac199. [CrossRef]

- Bai S, Tao R, Yin L, Ni J, Yang Q, Yan X, et al. Two B-box proteins, PpBBX18 and PpBBX21, antagonistically regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis via competitive association with Pyrus pyrifolia ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 in the peel of pear fruit. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2019;100:1208–23. [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun S, Gould KS. Role of Anthocyanins in Plant Defence. In: Winefield C, Davies K, Gould K, editors. Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. p. 22–8. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Arbulú C, Gianoli E, Gonzáles WL, Niemeyer HM. Feeding by the aphid Sipha flava produces a reddish spot on leaves of Sorghum halepense: an induced defense? J Chem Ecol. 2001;27:273–83. [CrossRef]

- Werlein H-D, Kütemeyer C, Schatton G, Hubbermann EM, Schwarz K. Influence of elderberry and blackcurrant concentrates on the growth of microorganisms. Food Control. 2005;16:729–33. [CrossRef]

- Barbehenn RV, Constabel CP. Tannins in plant-herbivore interactions. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:1551–65. [CrossRef]

- Gong W-C, Liu Y-H, Wang C-M, Chen Y-Q, Martin K, Meng L-Z. Why Are There so Many Plant Species That Transiently Flush Young Leaves Red in the Tropics? Front Plant Sci. 2020;11. [CrossRef]

- Johnson ET, Berhow MA, Dowd PF. Colored and White Sectors From Star-Patterned Petunia Flowers Display Differential Resistance to Corn Earworm and Cabbage Looper Larvae. J Chem Ecol. 2008;34:757–65. [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun S, Ne’eman G, Izhaki I. Unripe red fruits may be aposematic. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:836–41. [CrossRef]

- Cook AD, Atsatt PR, Simon CA. Doves and Dove Weed: Multiple Defenses against Avian Predation. BioScience. 1971;21:277–81. [CrossRef]

- Williamson GB. Plant mimicry: evolutionary constraints. Biol J Linn Soc. 1982;18:49–58. [CrossRef]

- Gerchman Y, Dodek I, Petichov R, Yerushalmi Y, Lerner A, Keasar T. Beyond pollinator attraction: extra-floral displays deter herbivores in a Mediterranean annual plant. Evol Ecol. 2012;26:499–512. [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun S. Visual-, Olfactory-, and Nectar-Taste-Based Flower Aposematism. Plants. 2024;13:391. [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun S. Aposematic (warning) Coloration Associated with Thorns in Higher Plants. J Theor Biol. 2001;210:385–8. [CrossRef]

- Ichiishi S, Nagamitsu T, Kondo Y, Iwashina T, Kondo K, Tagashira N. Effects of Macro-components and Sucrose in the Medium on in vitro Red-color Pigmentation in Dionaea muscipula Ellis and Drosera spathulata Laill. Plant Biotechnol. 1999;16:235–8. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Eberhardt SA, Weber MG, Gilbert KJ. Anthocyanin Impacts Multiple Plant-Insect Interactions in a Carnivorous Plant. Am Nat. 2025;205:502–15. [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun S. Avoiding rather than resisting herbivore attacks is often the first line of plant defence. Biol J Linn Soc. 2021;134:775–802. [CrossRef]

- Stone BC. Protective Coloration of Young Leaves in Certain Malaysian Palms. Biotropica. 1979;11:126. [CrossRef]

- Juniper B. Flamboyant flushes: a reinterpretation of non-green flush colours in leaves. Int Dendrol Soc Yearb. 1993;:49–57.

- Lev-Yadun S. Why do some thorny plants resemble green zebras? J Theor Biol. 2003;224:483–9. [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun S, Inbar M. Defensive ant, aphid and caterpillar mimicry in plants? Biol J Linn Soc. 2002;77:393–8. [CrossRef]

- Sinkkonen A. Red Reveals Branch Die-back in Norway Maple Acer platanoides. Ann Bot. 2008;102:361–6. [CrossRef]

- Givnish TJ. Leaf Mottling: Relation to Growth Form and Leaf Phenology and Possible Role as Camouflage. Funct Ecol. 1990;4:463–74. [CrossRef]

- Gould KS. Leaf Heteroblasty in Pseudopanax crassifolius: Functional Significance of Leaf Morphology and Anatomy. Ann Bot. 1993;71:61–70. [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun S, Dafni A, Flaishman MA, Inbar M, Izhaki I, Katzir G, et al. Plant coloration undermines herbivorous insect camouflage. BioEssays News Rev Mol Cell Dev Biol. 2004;26:1126–30. [CrossRef]

- Ide J-Y. Why do red/purple young leaves suffer less insect herbivory: tests of the warning signal hypothesis and the undermining of insect camouflage hypothesis. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2022;16:567–81. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer HM, Rolshausen G. Plants on red alert: do insects pay attention? BioEssays News Rev Mol Cell Dev Biol. 2006;28:65–71. [CrossRef]

- Gronquist M, Bezzerides A, Attygalle A, Meinwald J, Eisner M, Eisner T. Attractive and defensive functions of the ultraviolet pigments of a flower (Hypericum calycinum). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13745–50. [CrossRef]

- Armbruster WS. Can indirect selection and genetic context contribute to trait diversification? A transition-probability study of blossom-colour evolution in two genera. J Evol Biol. 2002;15:468–86. [CrossRef]

- Flachowsky H, Szankowski I, Fischer TC, Richter K, Peil A, Höfer M, et al. Transgenic apple plants overexpressing the Lc gene of maize show an altered growth habit and increased resistance to apple scab and fire blight. Planta. 2010;231:623–35. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Butelli E, De Stefano R, Schoonbeek H, Magusin A, Pagliarani C, et al. Anthocyanins Double the Shelf Life of Tomatoes by Delaying Overripening and Reducing Susceptibility to Gray Mold. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1094–100. [CrossRef]

- Wegener CB, Jansen G. Soft-rot Resistance of Coloured Potato Cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.): The Role of Anthocyanins. Potato Res. 2007;50:31–44. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).