1. Introduction

The deformation of long-span cable-stayed bridges experiences dynamic changes due to the combined effects of temperature, wind, train load, settlement, and creep during operation [

1]. In China, extensive railway cable-stayed bridges have main spans ranging from 200 m to over 1,000 m. As the main span increases, the cable-stayed bridge’s stiffness transitions from beam-strong to cable-strong [

2,

3,

4]. This shift in stiffness significantly impacts the deformation of large-span cable-stayed bridges, influencing the vibration acceleration of the car body. Therefore, a thorough investigation into the deformation characteristics of large-span cable-stayed bridges under various loads is essential.

Some scholars have investigated the stiffness of long-span cable-stayed bridges and girder-rail synergy. Chen et al. [

5] systematically summarized the large-span cable-stayed bridges of railroads constructed in China, and put forward the recommended vertical deflection-to-span ratios of large-span cable-stayed bridges of railroads and public-railways. Liu et al. [

6]investigated the effects of structural parameters such as the number of side-span auxiliary piers, side-to-center span ratio, main beam width-to-span ratio and height-to-span ratio on the stiffness and mechanical properties of cable-stayed bridges. Zheng et al. [

7,

8,

9] explored the effect of elastic matting stiffness on the deformation of main beams of large-span railroad cable-stayed bridges and the structural deformation of interlayer of ballasted track slabs on the bridges, and the uneven deformation of interlayer between the track slabs and the base slabs could be better coordinated through the setting of rubber matting. Taking a long-span cable-stayed bridge with a span ranging from 300 m to 1000 m as the research object, Zhu et al. [

10,

11] established a refined nonlinear model of large-span cable-stayed bridge-ballastless track, analyzed the deformation characteristics of the long-span cable-stayed bridge under the action of train load and temperature, and proposed that the measurement value of the mid-span chord with a length of 60m and 40m has a higher match with the vertical vibration acceleration of the car body.

Based on the principle of midpoint chord measurement method, Yang et al. [

12,

13] investigated the relationship between long-wave track irregularity and car body vertical acceleration in high-speed railroads, and proposed the 60m chord control standard of track irregularity under 250~350 km/h. Jin et al. [

14] measured the track unevenness statistics of different wavelength track unevenness and body acceleration relationship, the study shows that greater than 200m wavelength track irregularity on the train body acceleration effect is negligible. The correlation between track unevenness and vehicle vibration acceleration in the roadbed section was revealed by analyzing the track inspection data of the roadbed section. Some scholars [

15,

16] based on Fourier transform analysis, multi-span simply supported beam bridge deformation wavelength decomposition, analyze the bridge deformation and wavelength characteristics of the correlation, the study shows that the 32m wavelength deformation of the deformation of the Xu-changing easily caused by high-speed trains coupled with abnormal vibration of the bridge.

However, the actual number of large-span railway cable-stayed bridges in China is relatively small, and the feasibility study of long-span cable-stayed bridges laying ballastless track is basically based on the idea that one bridge corresponds to one solution. The deformational characteristics of large-span cable-stayed bridges and the mapping relationship between rail-bridge deformation under complex loads have not been systematically studied. It is difficult to determine the relationship between track irregularity and carbody vibration acceleration on long-span cable-stayed bridges. This paper investigates the wavelength characteristic and track-bridge deformation mapping of long-span railway cable-stayed bridge under complex loads. Additionally, the train dynamic simulation model has been simplified, enhancing the program simulation’s efficiency. Firstly, the finite element model of the rail structure to clarify the relationship between bridge deformation and rail deformation is established. Secondly, the structural arrangement scheme for a cable-stayed bridge with a main span ranging from 200 m to 600 m is designed. The deformation characteristic under complex loads is analyzed. Utilizing the research background of an actual long-span cable-stayed bridge, we establish an integrated model of the beam-rail system, examining the wavelength characteristics of vertical deformation and track-bridge deformation mapping on the cable-stayed bridge. Finally, the vehicle-rail-bridge dynamic coupling simulation model is simplify based on the mapping relationship and wavelength characteristics.

2. Mapping Relationship between Rail Deformation and Bridge Deformation

The track irregularity is classified by the length of the wave: short wave, medium wave and long wave. Long wave unevenness primarily stems from foundation deformations, including topographic relief, roadbed settlement, and bridge deformation. When scholars explore the correlation between train vibration response and track irregularities in long-span bridges, it’s crucial to initially establish the mapping relationship between the long-span bridge deformation and the track irregularity.

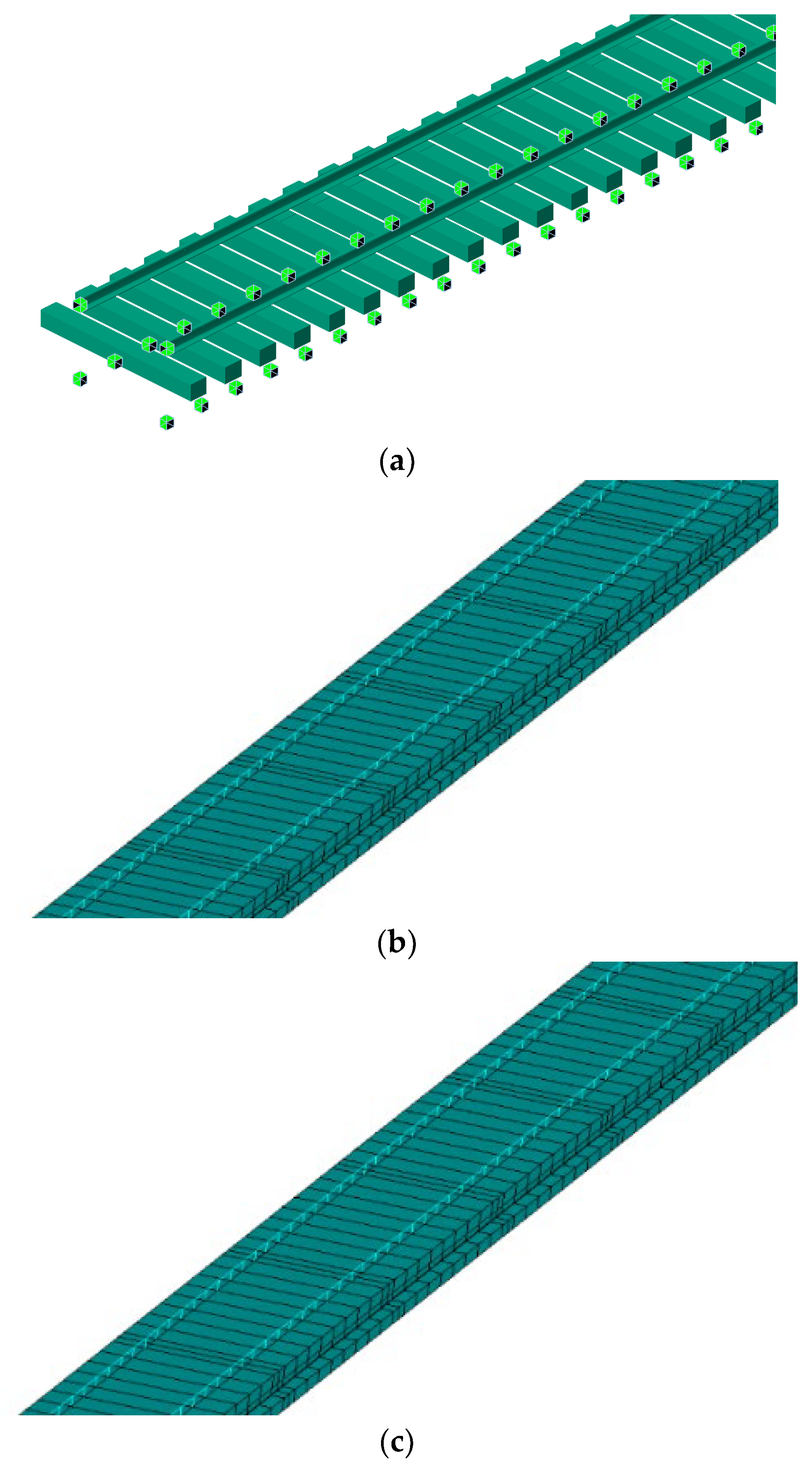

There are more types of the track structure used in China’s high-speed railways, mainly ballasted tracks and ballastless tracks. Ballastless tracks include the longitudinal ballastless track and the unit ballastless track. Finite element models of ballasted tracks, longitudinal ballastless tracks and unit ballastless tracks are established by ANSYS. The rail is modeled by BEAM188 element. Fastener is simulated by WJ-8 type fastener with three-way spring element. The fastener is modelled in the vertical and transverse directions with the COMBIN14 element, and in the longitudinal direction with the COMBIN39 element. The sleeper of ballasted track is simulated by BEAM188 element. The roadbed is simulated by three-way spring element. For the ballastless track, the track slab and base slab are simulated using SOLID 65 element. Their connection is modeled by nonliner spring elements with appropriate longitudinal, vertical, and lateral stiffness [

17]. The finite element model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

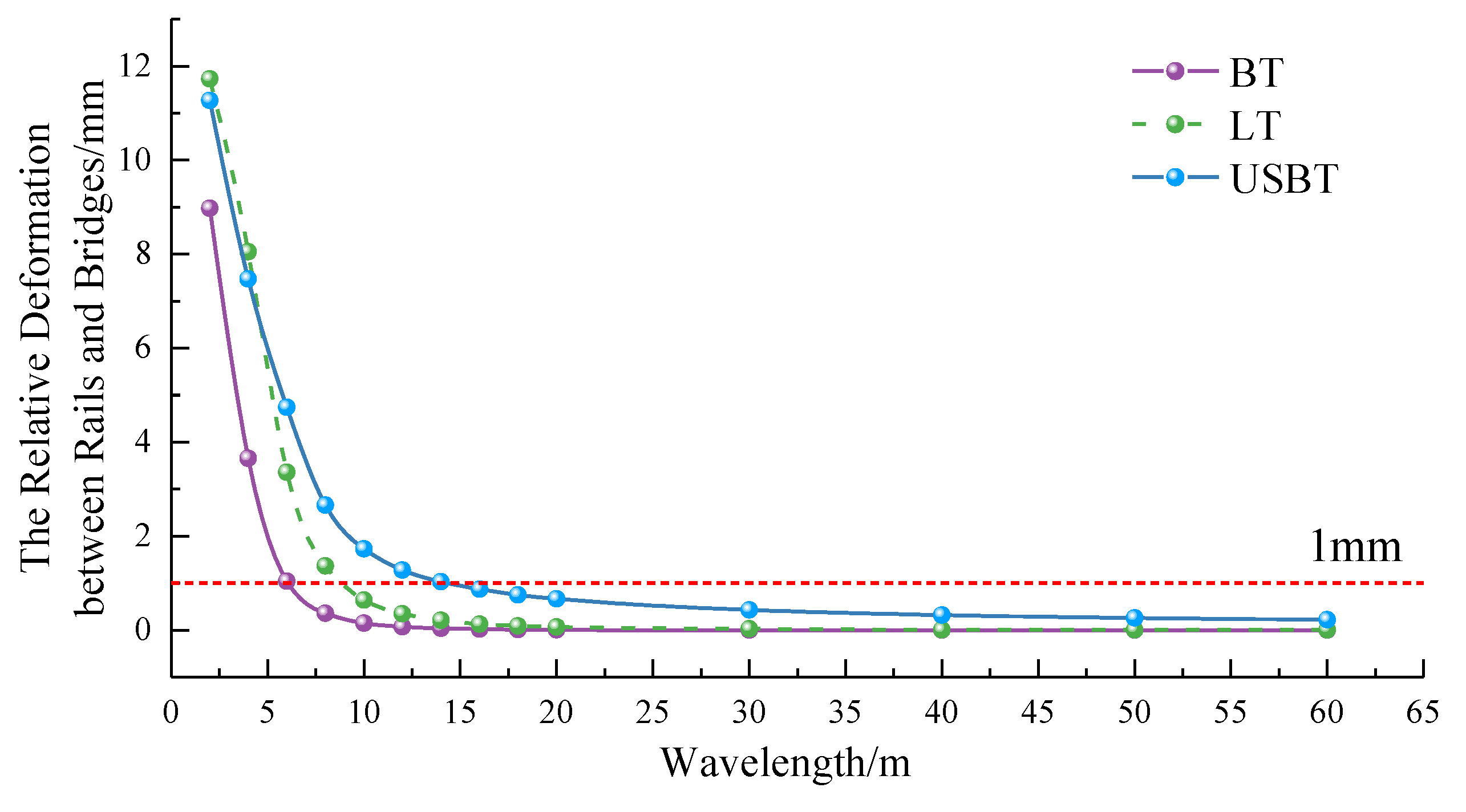

The deformation of the bridge can be analyzed by decomposing it into various wavelength deformations through the Fourier transform. To explore the difference between the rail deformation and the bridge deformation, continuous cosine waves with wavelengths ranging from 0.5 m to 120 m are applied to the bottom of track.

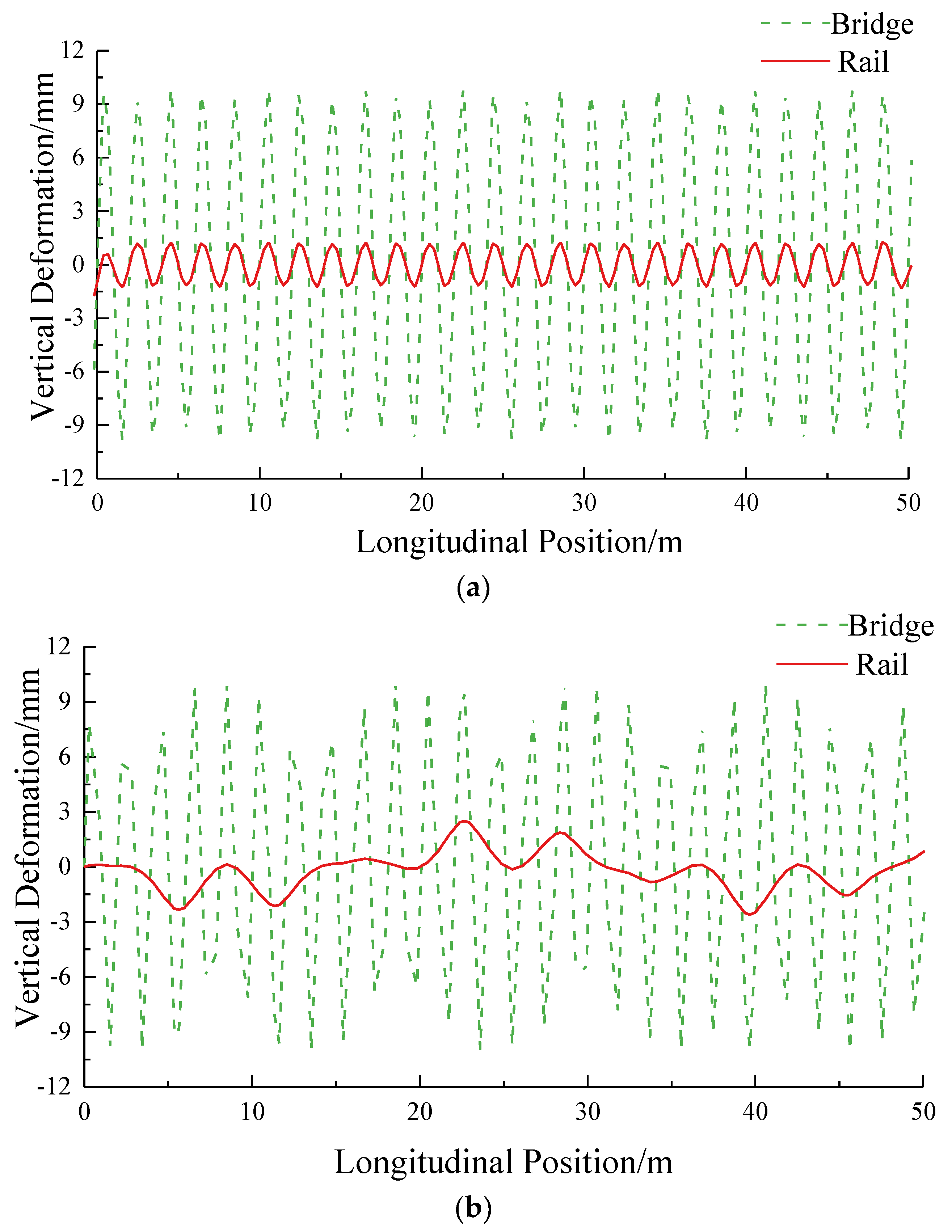

Figure 2 shows the deformation difference between rail deformation and deformation of the ballasted track (BT), longitudinal-connected track (LT), and unit slab-type ballastless track (USBT) influenced by continuous cosine waves with varying wavelengths. The figure reveals that when the bridge deformation wavelength exceeds 6m, 10m, and 16m for BT, LT, and USBT, the difference in deformation between the bridge and track is less than 1mm. Conversely, for bridge deformation wavelengths below 6m, 10m, and 16m, a substantial difference is observed in both track and bridge deformation.

Figure 3 shows the rail deformation and rail deformation under the cosine wave excitation of the 2m wavelength. For the BT, LT, and USBT, their deformation differences respectively are 8.97 mm, 11.73 mm and 11.27 mm.

For BT, LT, and USBT, the 1:1 mapping relationship of deformation between the rail and the bridge can be established when the bridge deformation respectively exceeds 6m, 10m, and 16m. The rail deformation precisely mirrors the bridge deformation. However, when the bridge deformation wavelength is less than 6m, 10m, and 16m, a significant difference of the deformation emerges between track and bridge. When the rail deformation can’t mirror the bridge deformation, it is necessary to establish a comprehensive rail-bridge model to accurately capture rail deformation.

3. Wavelength Characteristics of Vertical Deformation of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges under Complex Loads

To investigate the vertical deformation wavelength characteristics of long-span cable-stayed bridges with main span of 200 m to 600 m under complex loads. The process begins by establishing the structural parameters of cable-stayed bridges, focusing on designing large-span cable-stayed bridges with main spans ranging from 200 m to 600 m. Then, the calculation of the vertical deformation of the bridge deck for these large-span cable-stayed bridges takes place, considering the impact of the cable-stayed-beam stiffness ratio under complex loads. Finally, employing the high-pass filtering theory, the vertical deformation of bridge deck is decomposed. To obtain the range of vertical deformation wavelengths for long-span cable-stayed bridges, the minimum and maximum wavelengths, representing 1% and 99% of the deformation energy, are extracted from the vertical deformation of bridge.

3.1. Design of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges

After establishing the main beam span diameter, the primary step involves selecting the main beam material based on this span diameter. And the side span diameter, bridge tower height, and the spacing of the cable-stay arrangement are provided. Further, parameters such as the main beam cross-section, cable diameter, and tower cross-section are determined. In order to ensure the stiffness of the structure under complex loads, the design considers the vertical deflection of the main beam under static and live loads to keep it within the range of L/500.

Research suggests that cable-stayed bridges with a general main span of less than 400 m are best suited for concrete main beams. In the case of main spans ranging from 400 m to 500 m, the choice involves comparing composite beams and concrete beams. Spans exceeding 500 m are recommended to use steel main beams or a combination of steel and concrete beams. In this study, concrete main beams are considered for a main span of 200 m. For a main span of 400 m, both concrete beams and steel-concrete combination beams are contemplated. Additionally, a main span of 600 m is being considered for steel-concrete combination beams and steel main beams. Following the selection of the main span and the material of the main beam, the side span’s extent, the bridge tower’s height, and the spacing between the stay cables are determined based on the literature[

18]. These values are detailed in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

In the investigation of actual large-span cable-stayed bridges ranging from 200 m to 600 m, the common design choice is the utilization of double-tower double-side cable-stayed bridges, employing “H”-type concrete bridge towers. The cable-free zone near the bridge tower and abutment supports is set to a length of 2~3 times the diagonal cable spacing. These values are detailed in

Table 3. To mitigate the horizontal displacement of the mid-span moment of the main beam, strategically placed auxiliary piers are present at the side spans. The spanning ratio for a single auxiliary pier corresponding to the side spans is 4:6. And the ratio for double auxiliary piers corresponding to the side spans is 4:3:3. For the majority of cable-stayed bridges, a semi-floating system is employed, where dampers impose longitudinal shape constraints in the longitudinal direction. While these longitudinal dampers are active under seismic and wind loads, they have minimal impact on temperature-induced deformations. Consequently, no longitudinal restraints are introduced for the 200 m, 400 m, and 600 m cable-stayed bridges in this study.

Fifteen structural schemes for cable-stayed bridges, considering main beam types and auxiliary pier arrangements, are presented in

Table 4. Finite element models of cable-stayed bridges are established by Midas software. The main beam and bridge tower are modeled by beam element. The cable is simulated by truss element. The connection between the main beam and the support is modeled by a rigid arm unit. The support is rigidly connected with the foundation. The model of the long-span cable-stayed bridge is depicted in

Figure 4.

3.2. Vertical Deformation of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges under Complex Loads

3.2.1. Complex Loads

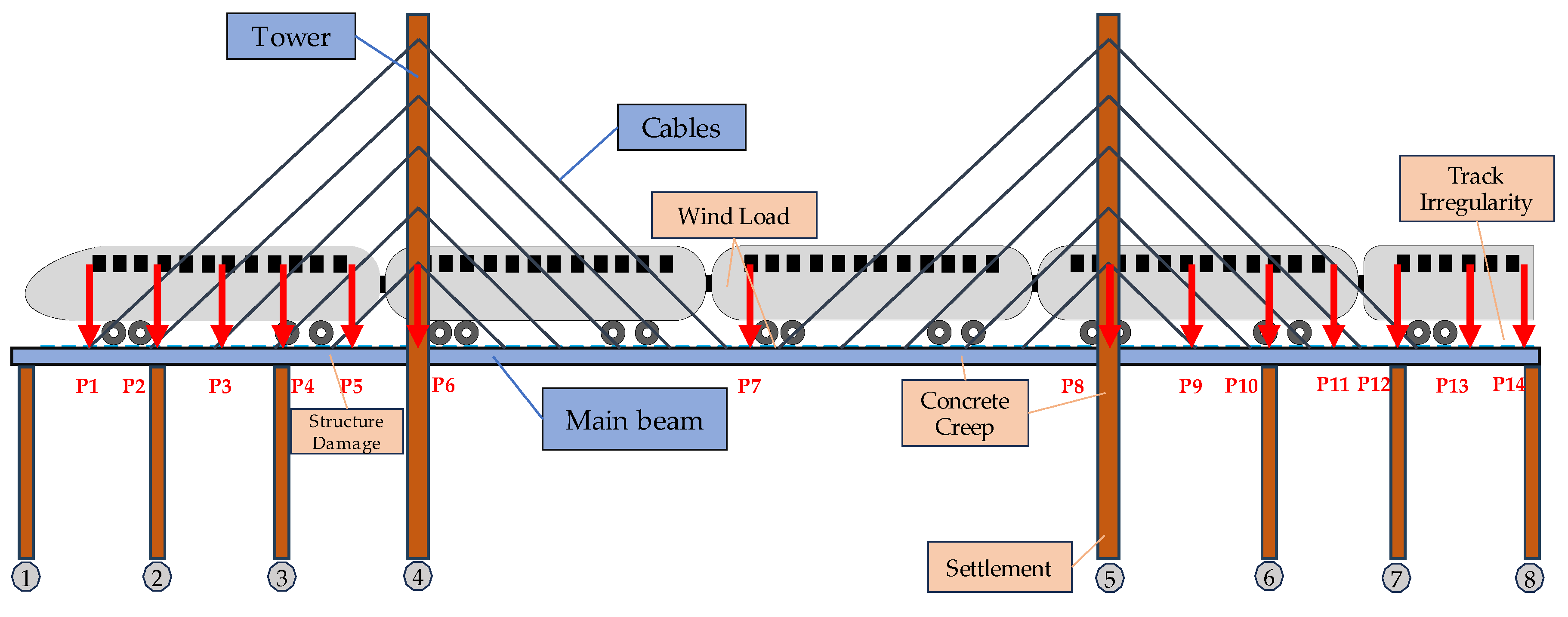

As shown in

Figure 5, complex loads for long-span cable-stayed bridges encompass train load, temperature, and pier settlement, with wind load effects currently excluded due to their minimal impact on vertical deformation. The vertical deformation and wavelength characteristics of cable-stayed bridges exhibit variations under different train formations. Train loads are considered for 8 cars with a length of 200 m and 16 cars with a length of 400 m. Temperature is factored in the overall lift of 20 ℃and the 15 ℃ of the cables. Considering the arrangement of piers, including side pier, bridge tower, auxiliary pier settlement, and settlement combinations, the settlement of piers is set at 5mm. As an example, a 7-span steel-concrete combined beam cable-stayed bridge with a main span of 400m is examined to investigate the distribution of vertical deformation under typical loads.

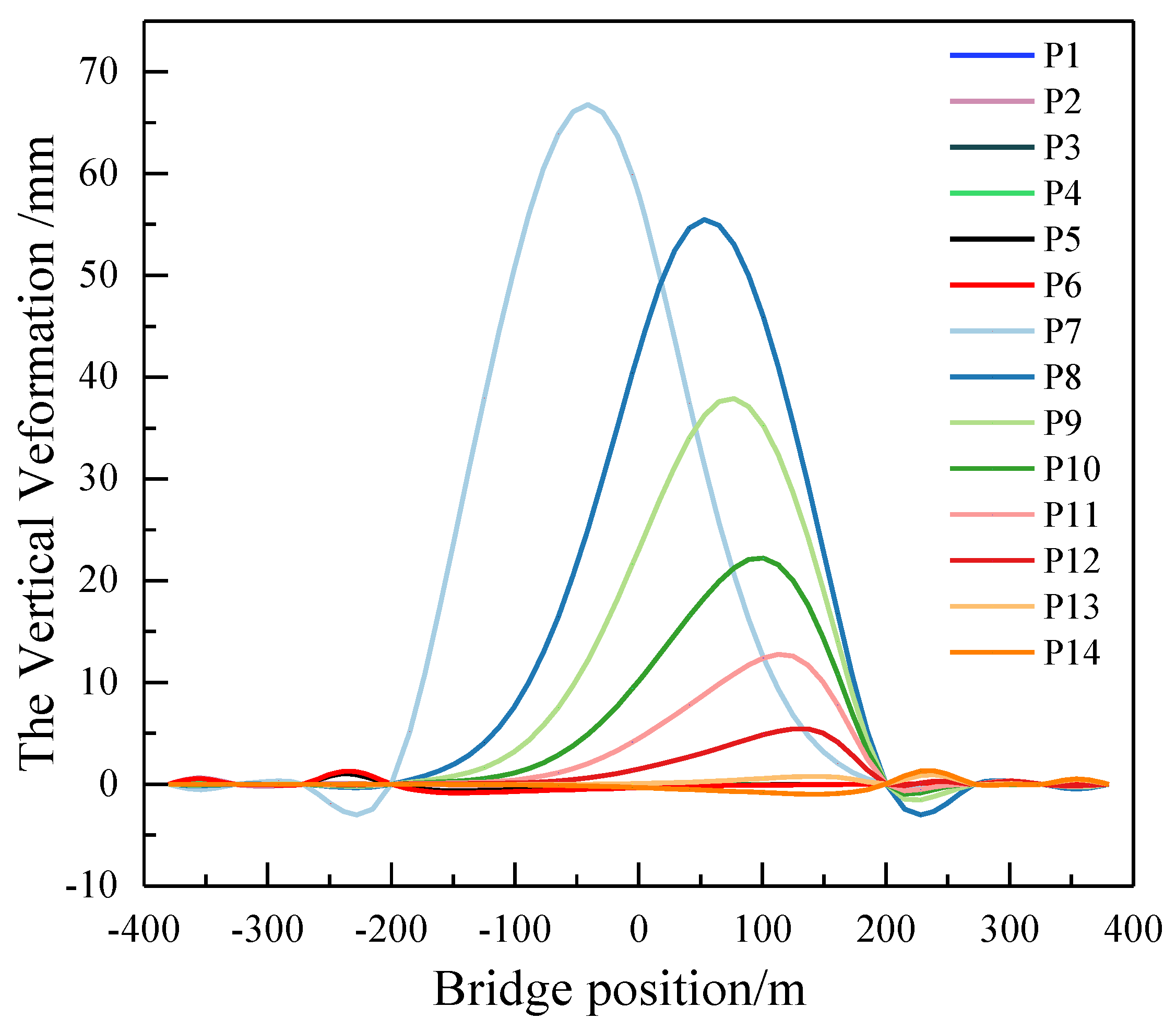

3.2.2. Train Loads

Figure 6 illustrates the vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge with the locomotive at different positions under the influence of 8 trains. From the Figure, the bridge floor deformation varies significantly as the train runs at different positions. When the train locomotive is on the middle span, the maximum deformation is 0.064 m near the middle span. As the locomotive moves to the right side, the maximum deformation position shifts to the right and continuously decreases. When the train runs on the left side span, the overall deformation of the bridge floor is relatively small. However, the deformation reverse bending points near the pier increase due to the presence of auxiliary piers.

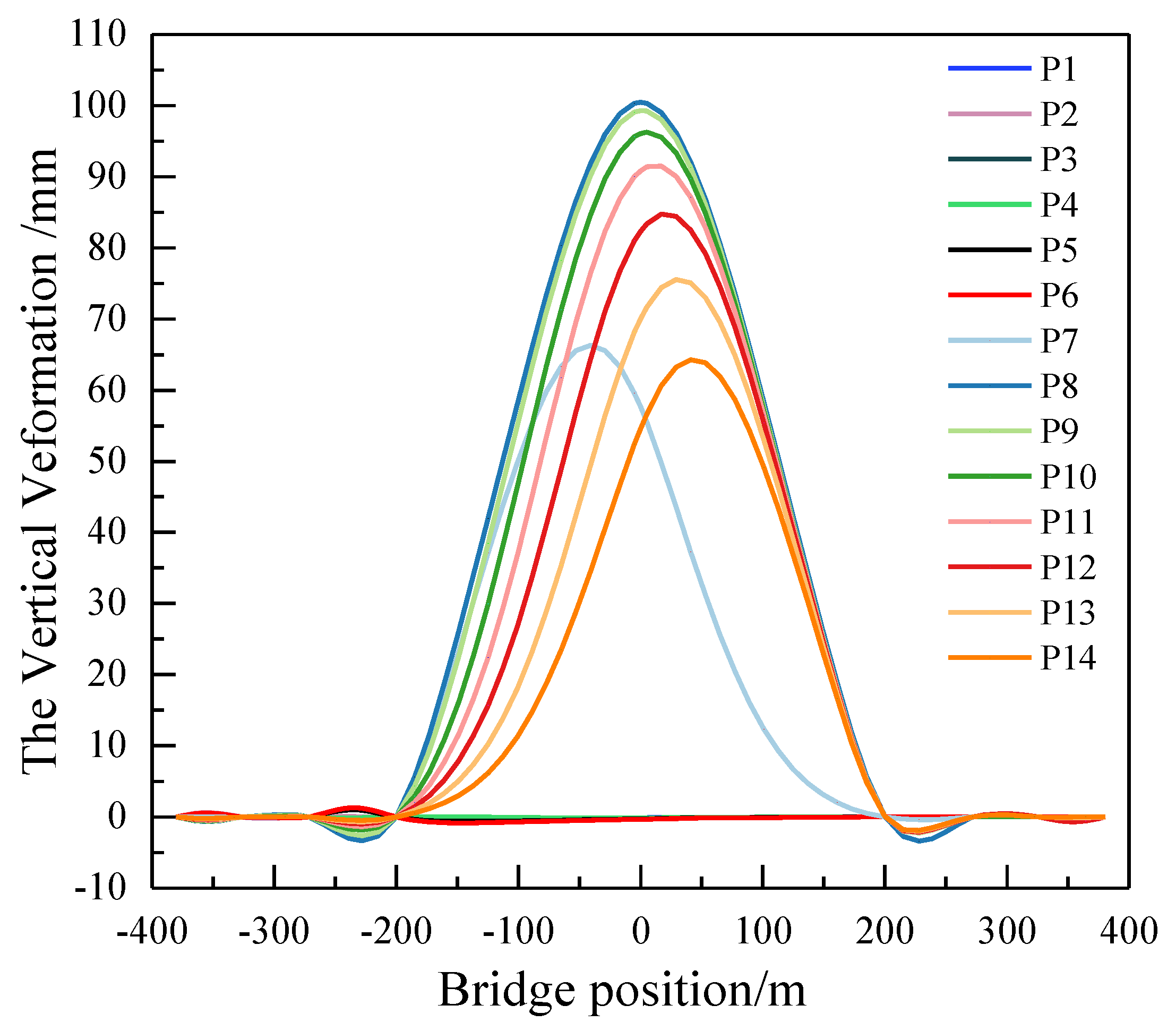

Figure 7 shows the vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge with the locomotive at different positions under the influence of 16 trains. The vertical deformation of the bridge floor increases overall when 16 vehicles are running on the cable-stayed bridge with a main span of 400 m. Since the length of the 16 trains is the same as the span of the main span of the bridge, the maximum deformation of the bridge floor is 0.097m when the trains are fully deployed in the middle span. Compared with the 8-car formation, the vertical deformation waveform of the bridge deck is significantly different when the 16-car formation is running in the middle span and the right span.

3.2.3. Integral Temperature Rise and Fall

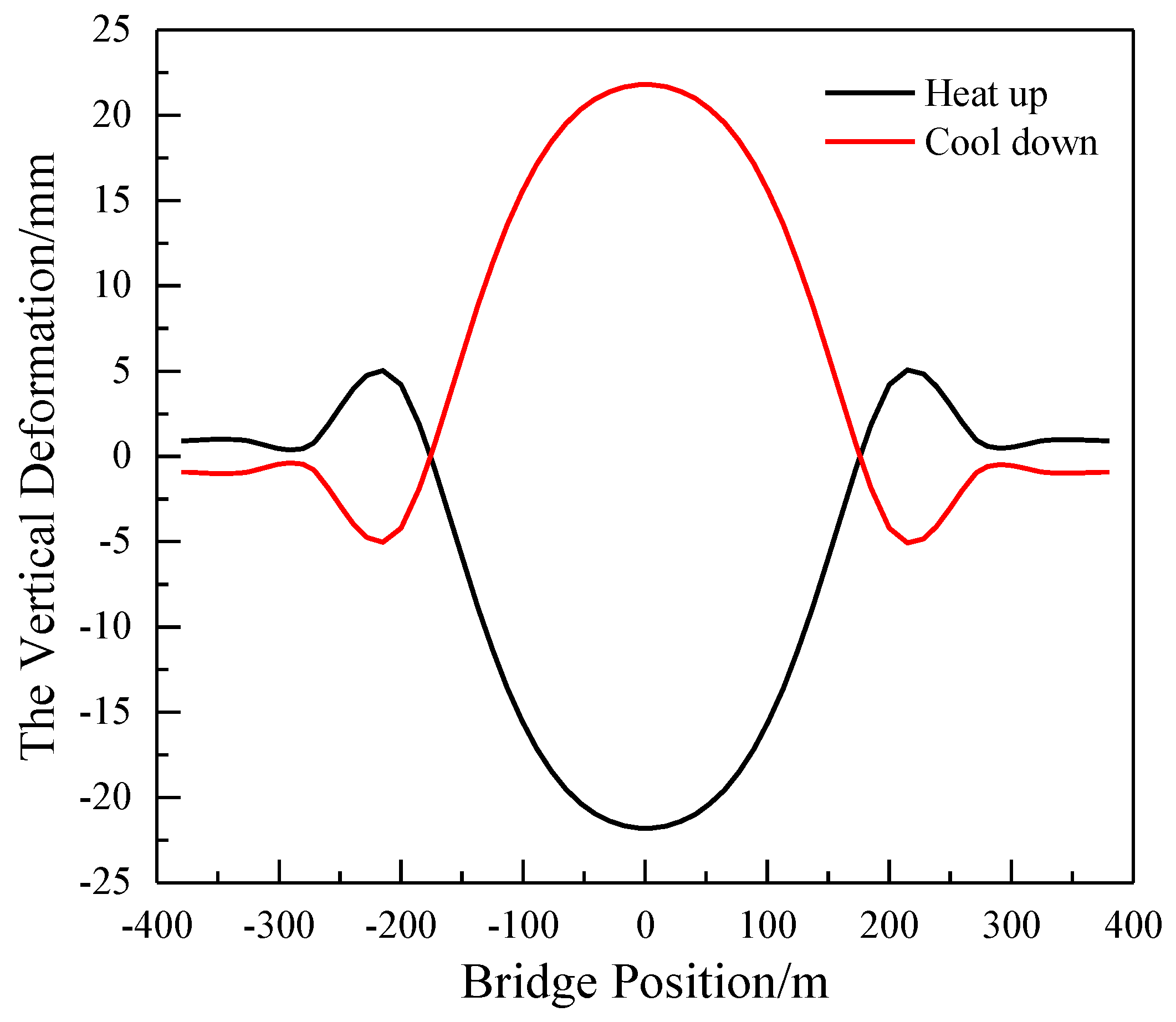

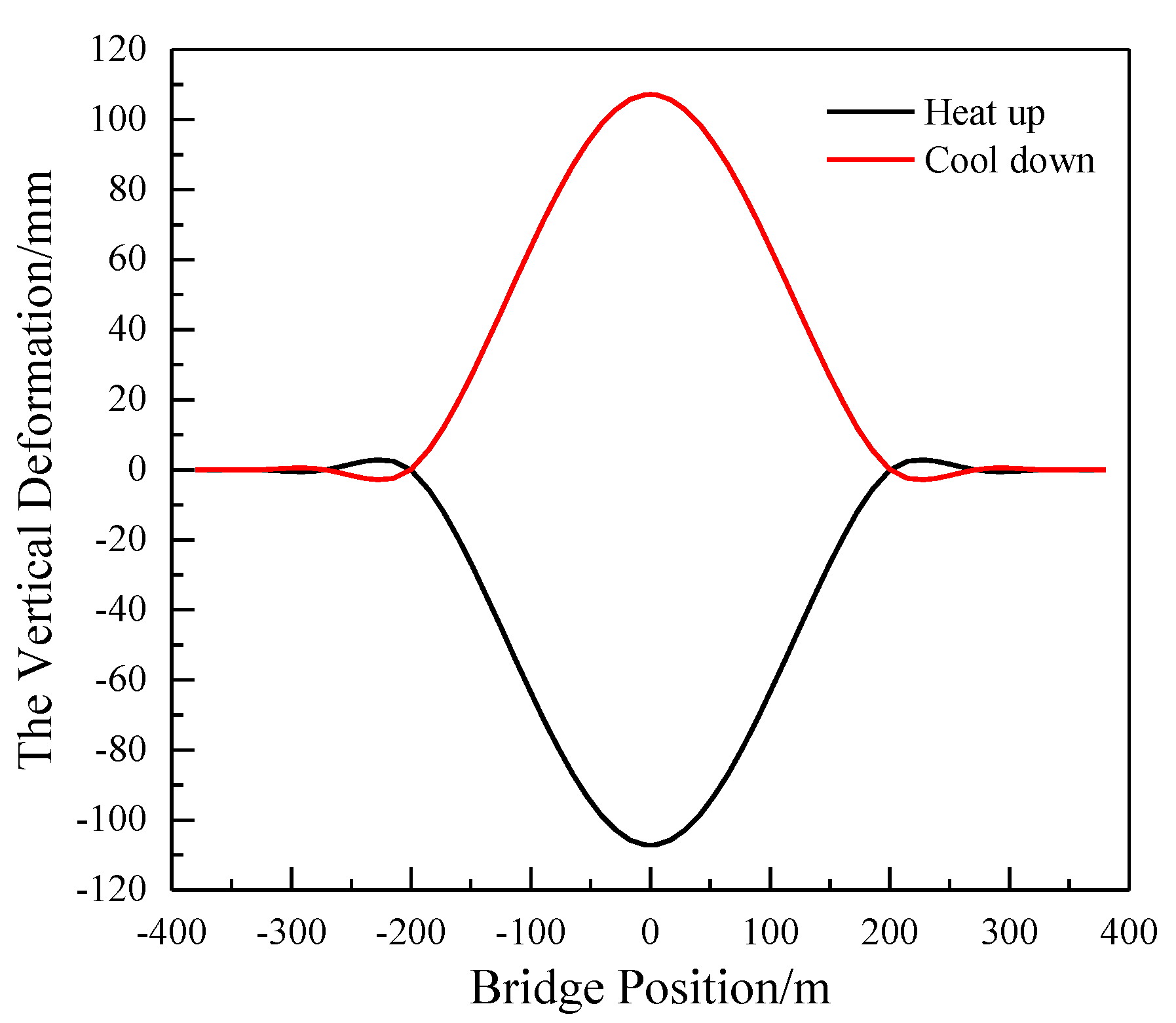

Considering an overall temperature increase of 20 ℃ for the cable-stayed bridge,

Figure 8 illustrates the vertical deformation of the main span 400 m cable-stayed bridge deck. The

Figure 8 unveils dynamic changes in the bridge’s deformation corresponding to temperature fluctuations. The side span and the main span of the continuous beam bridge collectively exhibit upward arching during warming and downward deflection during cooling, with larger vertical displacement in each span. The deformation waveform in the middle span demonstrates smoothness. While in the side spans and near the supports of auxiliary spans, extremum points are evident, indicating the prevalence of short-wave deformations in these locations.

3.2.4. Difference between Cable and Beam Temperature

Considering a temperature increase of 15 ℃ for cables,

Figure 9 shows the vertical deformation of the cable-stayed bridge deck. From the figure, the maximum vertical deformation of bridge is 0.1 m under a temperature increase of 15 ℃ for cables. In comparison with the overall temperature difference, the temperature effect on the cable-stayed beam causes a more substantial vertical deformation of the bridge deck. The presence of auxiliary piers imposes constraints on the bridge deformation, leading to a more pronounced short-wave deformation in the side span under the influence of the temperature difference in the cable-stayed beam.

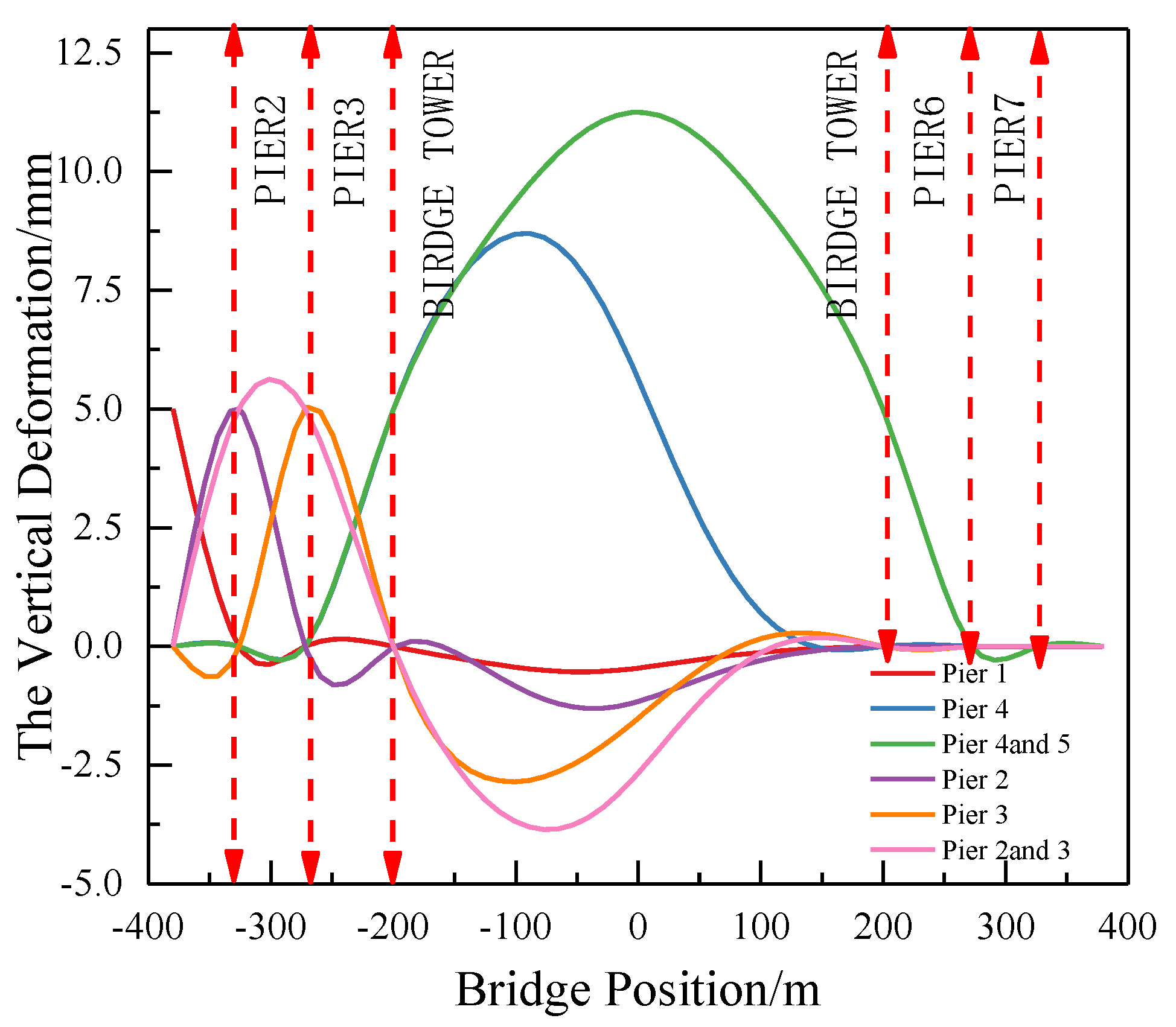

3.2.5. Settlement of Piers

The vertical deformation of the main beams in cable-stayed bridges displays significant variations under different forms of pier settlement. Settlement scenarios, such as single pier-assisted and multi-pier cross settlement, prove to be less favorable for achieving long-wave smoothness in the track. When considering settlement conditions individually for side piers, auxiliary piers, and the tower, the calculated vertical deformation of the main beam in a large-span cable-stayed bridge is presented in

Figure 10. When side span piers and auxiliary piers settle, the number of anti-bending points in the side span bridge deck increases, resulting in more pronounced short-wave deformation. Conversely, when settlement occurs uniformly across all components, the overall smoothness of the bridge deck deformation improves.

3.3. Wavelength Range of Vertical Deformation of 200 m~600 m Cable-Stayed Bridge

The aim is to examine the influence of the cable-stay stiffness ratio on the wavelength characteristic of vertical deformation in large-span cable-stayed bridges under typical loads. Two contrasting scenarios are explored: the strong beam with weak cables and the weak beam with strong cables. To evaluate the vertical deformation under these conditions, adjustments are made to the diameter of the tension cables, resulting in cable-beam stiffness ratios of 100 and 0.001. Employing the high-pass filtering principle, the vertical deformation of the bridge deck is decomposed into wavelengths ranging from 25 m to 1200 m at intervals of 50m. The minimum and maximum wavelengths are identified by intercepting those with 1% and 99% of the energy share in the bridge deformation. The resulting wavelength range of vertical deformation in long-span cable-stayed bridges is presented in

Table 5.

From the table, it becomes apparent that, for cable-stayed bridges sharing the same span arrangement, the stiffness of both the cable and the beam significantly influences the minimum and maximum wavelengths. Specifically, the weaker stiffness of beam result in the minimum values for both minimum and maximum wavelengths, while the stronger stiffness of beam lead to the maximum values. The substantial difference in the range of minimum and maximum wavelengths across these extremes underscores the profound impact of cable-stayed beam stiffness on the linear wavelength characteristics of the cable-stayed bridge.

Furthermore, an increase in the number of auxiliary piers contributes to a gradual decrease in the minimum and maximum wavelength. While the maximum wavelength remains relatively constant. For instance, in the case of a main span 200m cable-stayed bridge, the minimum and maximum wavelengths are 21.38m and 1268.29m. In the case of a main span 400m cable-stayed bridge, these values are 27m and 1268.81m. Finally, for a main span 600m cable-stayed bridge, the minimum and maximum wavelengths are 38.8m and 1270.74m.

4. Deformation Mapping Relationship between Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge and Ballastless Track Based on Engineering

4.1. Engineering Introduction

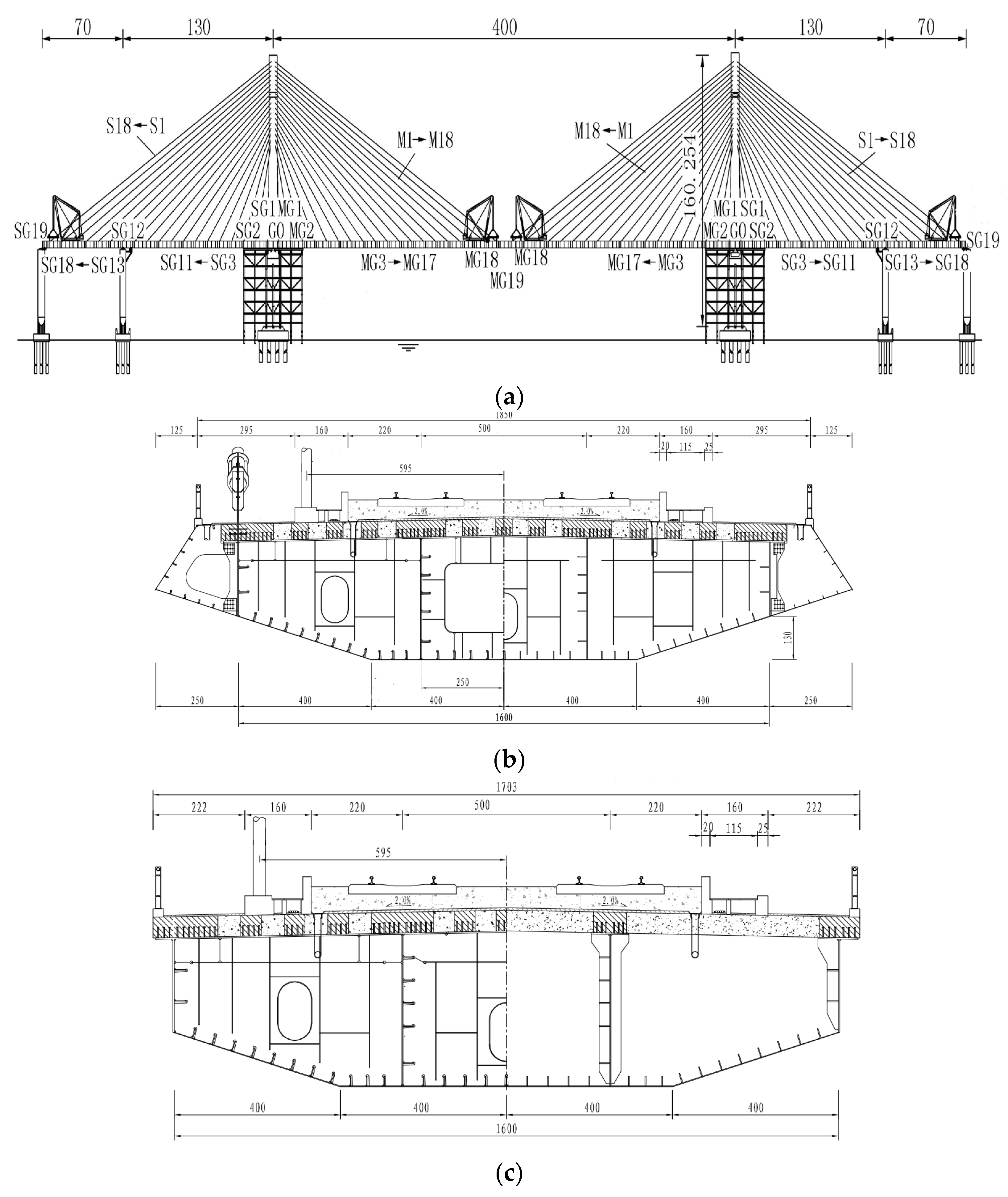

The sea-crossing bridge under consideration is a cable-stayed bridge with a main span of 400 m. Illustrated in

Figure 11, the bridge adopts a semi-floating system and adheres to a span arrangement of (70+130+400+130+70) m. The main beam, fashioned from a steel-concrete combination, maintains a standard section length of 10.5 m. Tower design follows an H-type configuration, with a tower height-to-main span diameter ratio of 1:3.649. The cable-stayed cables adopt a fan-shaped layout, totaling 72 pairs. Engineered for a speed of 350 km/h and featuring a two-lane configuration, the main line spacing is fixed at 5 m. The bridge integrates a ballastless track structure, laying seamless line.

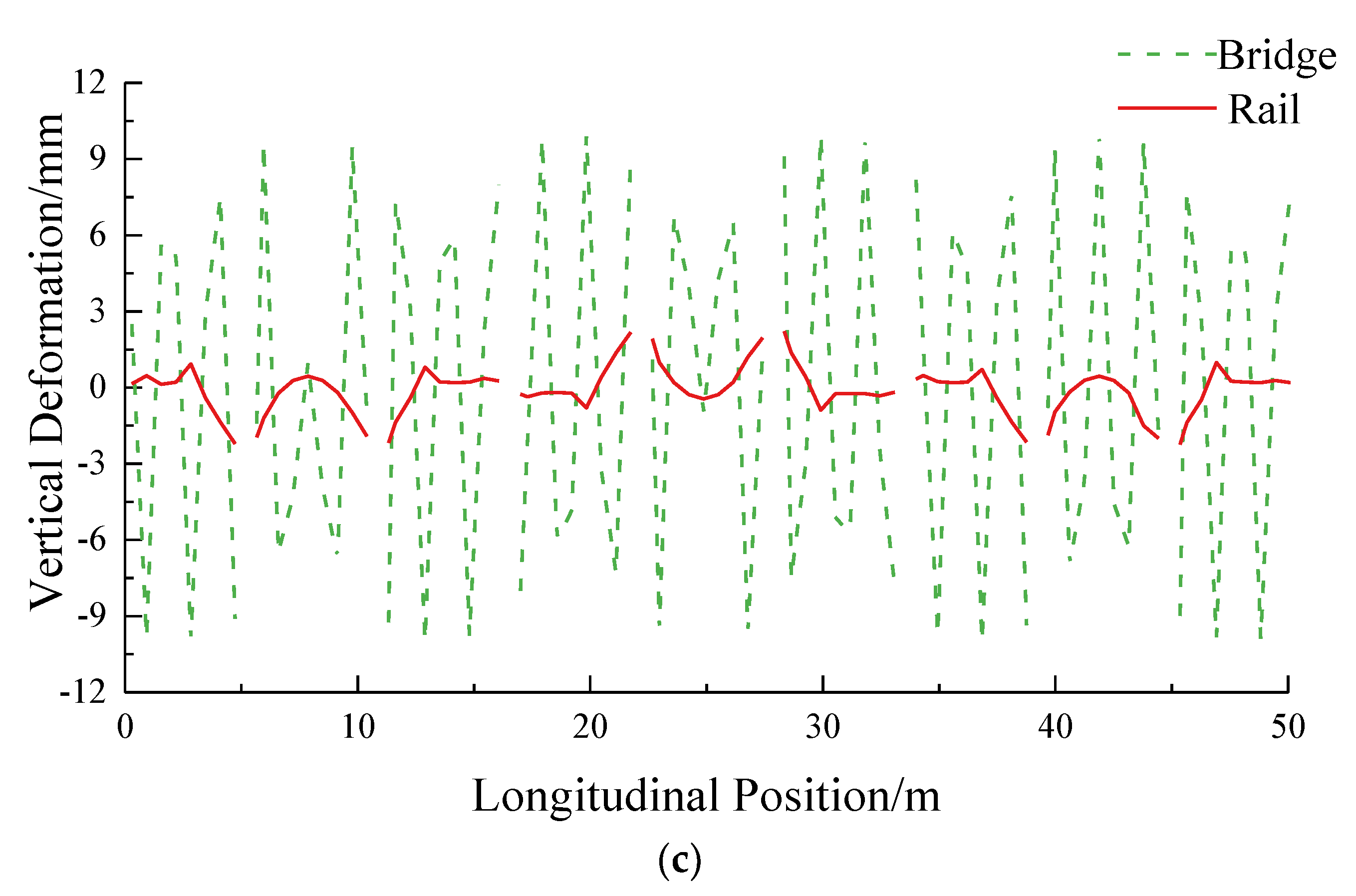

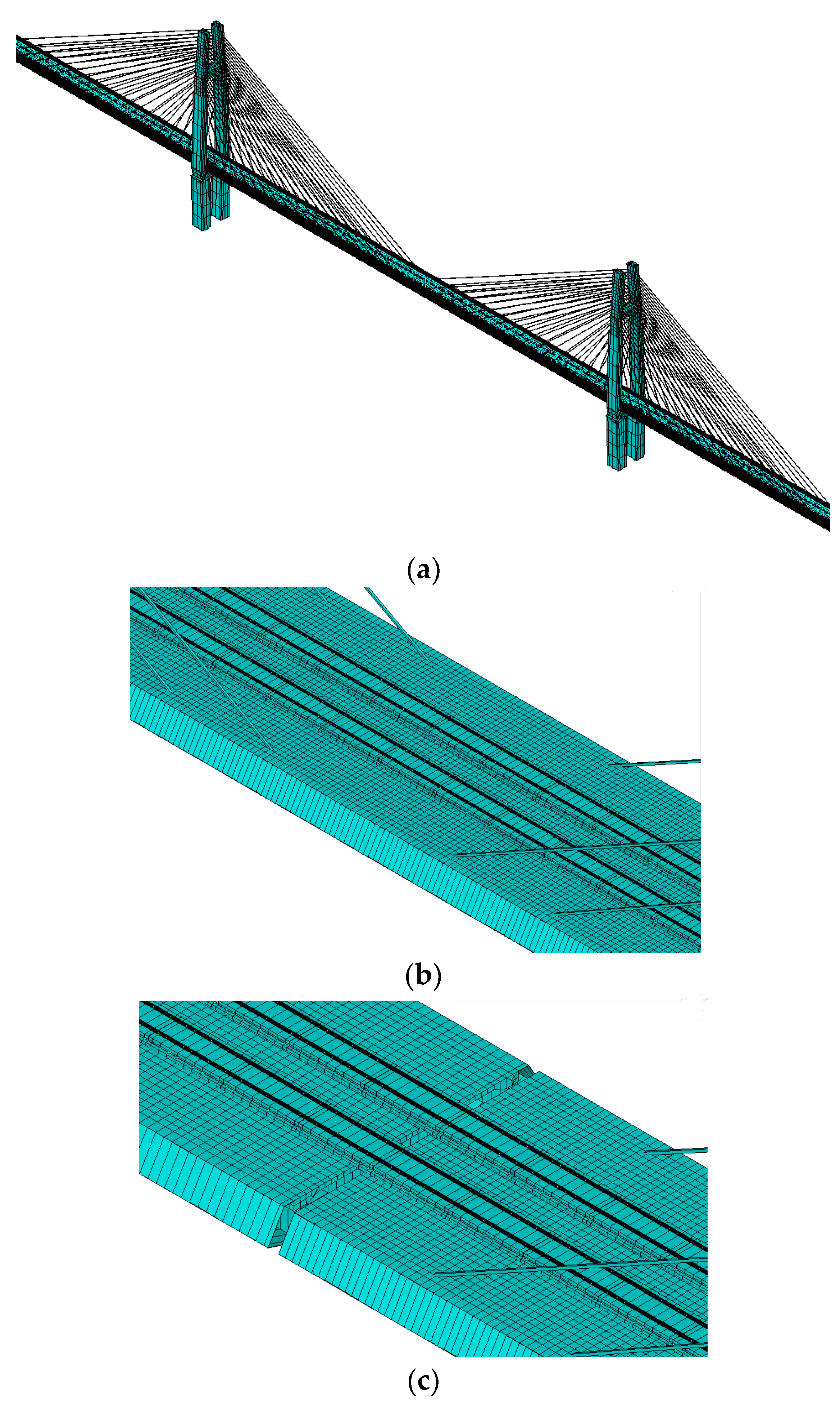

4.2. Finite Element Model of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge-Ballastless Track

The long-span cable-stayed bridge employs the multi-degree-of-freedom finite element method to establish the finite element model of long-span cable-stayed bridge-Ballastless track, as shown in

Figure 12.

The CRTSIII type plate ballastless track consists of rails, fasteners, track plates, self-compacting concrete, an isolation layer, and a base plate. To capture the complexity of the bridge model, cable-stayed cables are simulated using link elements, and the rest of the structure is represented by beam elements. A master-slave node is introduced to model the connection between the main beam and the abutment. The ballastless rail is simulated using beam elements, while track plates and base plates are represented by solid elements, and isolation layers and fasteners are depicted using three-way spring elements. To address the continuous deformation of the rail at the beam end position, a 3-span 32m simply supported beam bridge is established, following the side pier of the large-span cable-stayed bridge.

4.3. Characteristics of Deformation Wavelength of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges

As the train traverses the bridge and the auxiliary pier settles, the vertical deformation of the expansive cable-stayed structure becomes more pronounced within the wavelength range of less than 200 m. Moreover, the temperature differential between the cables and beams significantly impacts the vertical deformation of the main span. Considering these factors, a thorough examination is undertaken to explore the wavelength characteristics of vertical deformation in a long-span cable-stayed bridge. This investigation focuses specifically on scenarios involving a 5 mm settlement of auxiliary piers and a 15 ℃ temperature rise in tension cables, particularly during the train’s entry onto the bridge.

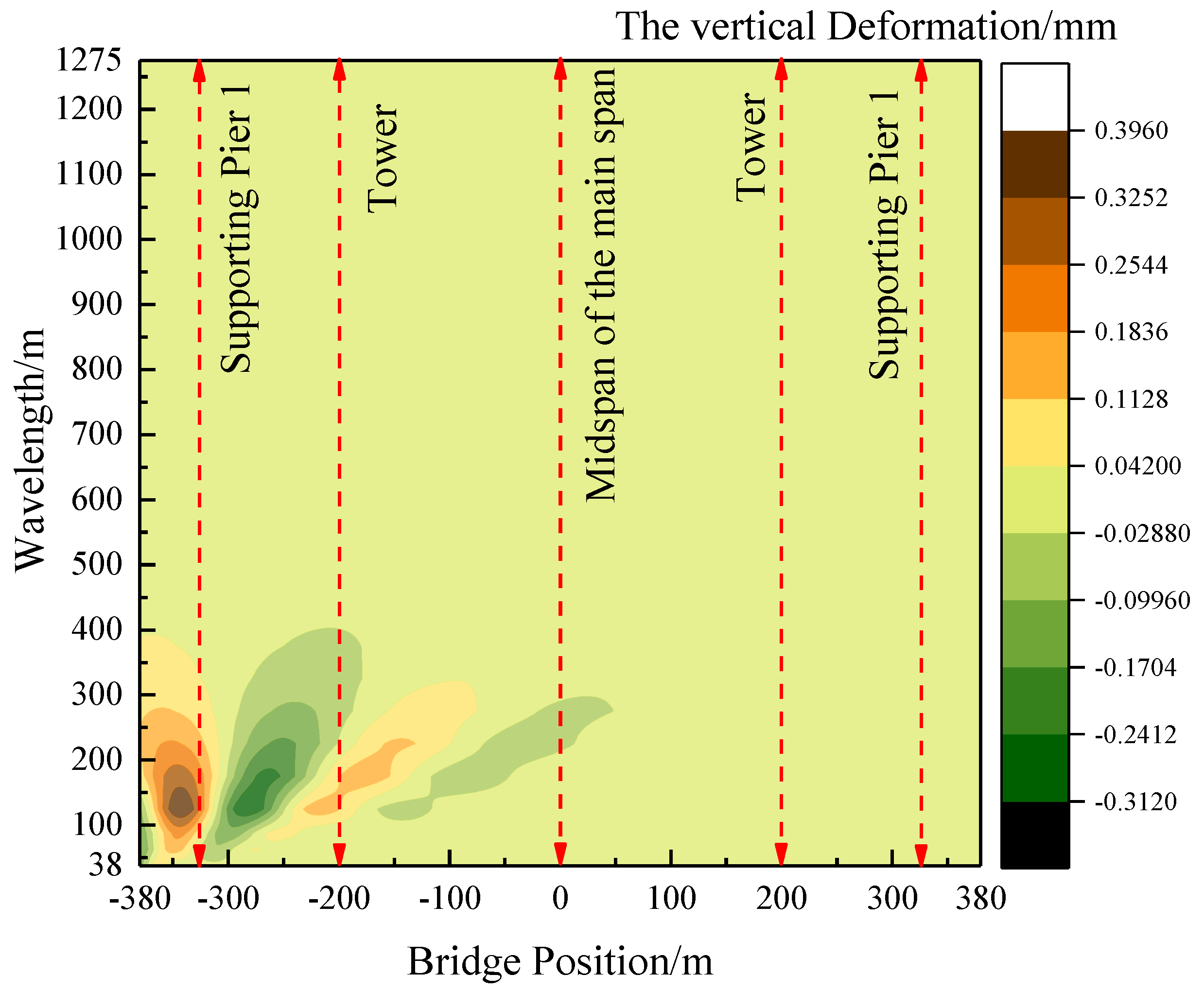

In

Figure 13, the distribution of vertical deformation in each wavelength section at different locations of the long-span cable-stayed bridge during the train’s entry is depicted. As the train approaches the bridge, noticeable variations in deformation wavelength characteristics emerge, particularly affecting the vertical deformation of the left span. Generally, the right span bears the predominant vertical deformation of the long-span cable-stayed bridge. The auxiliary span, on the other hand, predominantly undergoes deformation in wavelengths below 200 m, with larger deformation values. Notably, the deformation cutoff wavelength in the auxiliary span is set at 400 m.

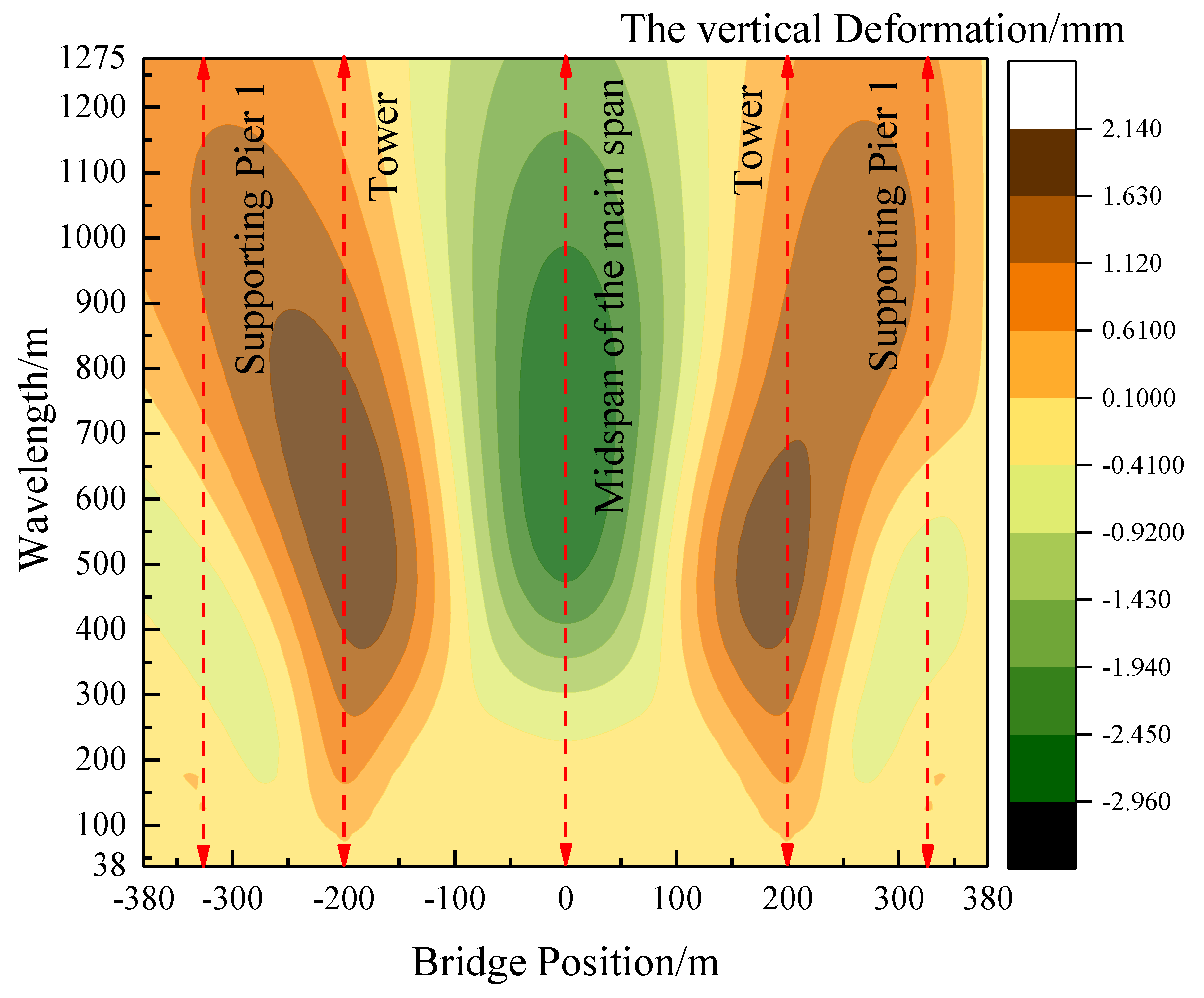

Figure 14 illustrates the distribution of vertical deformation in each wavelength section at different locations of the long-span cable-stayed bridge during the warming up of cables. The figure highlights a downward deflection in the main span and an upward arching in the side spans. In the wavelength section below 200 m, it is evident that the vertical deformation is more pronounced at the location of the bridge tower. This suggests that the long-wave smoothness of the bridge tower, under the influence of the warming up of cables, is relatively poor compared to other locations. The side span and mid-span locations are primarily dominated by long waves exceeding 200 m, with deformation concentrated in the wavelength range of 400 m ~1000 m.

In

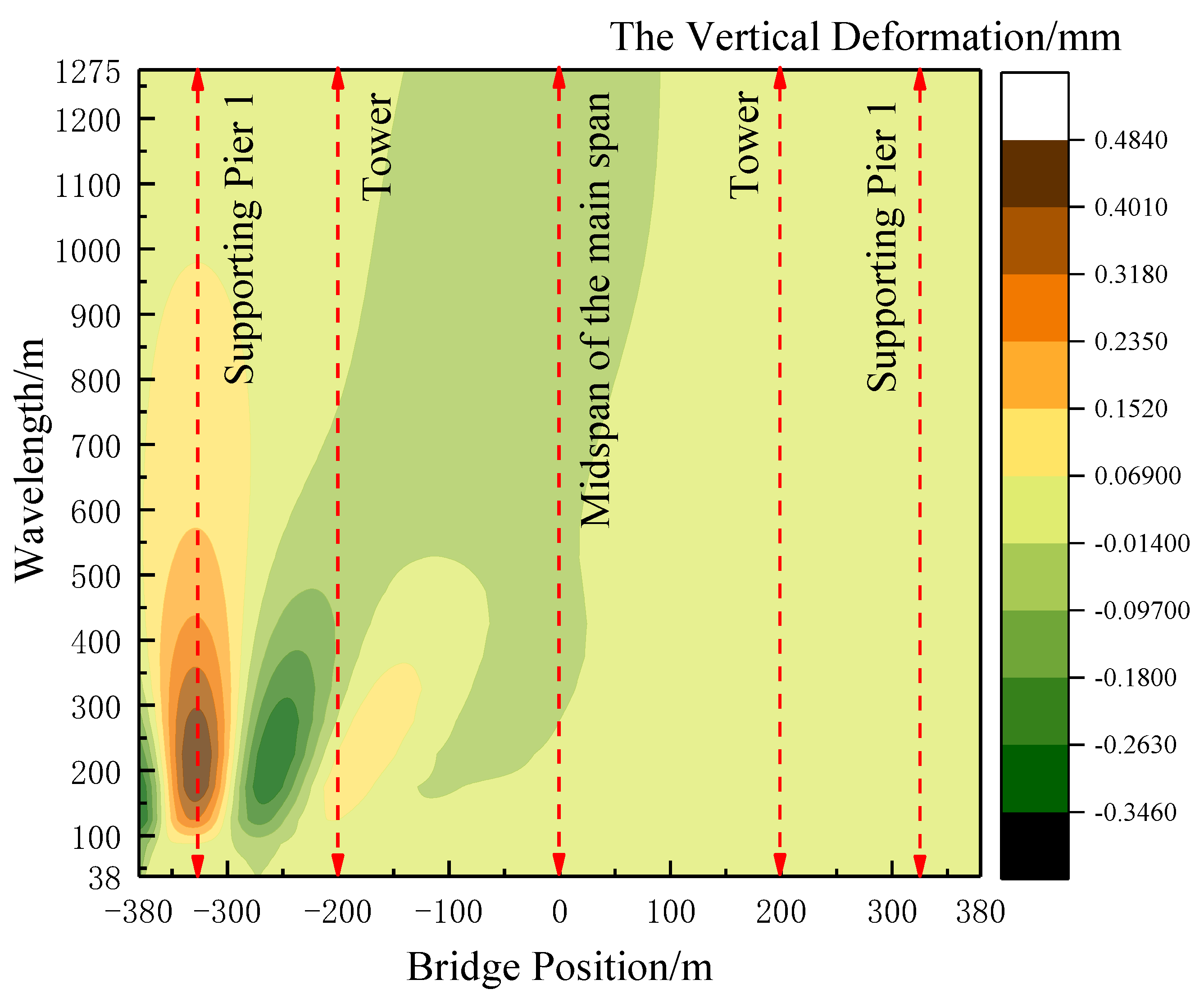

Figure 15, the vertical deformation distribution of each wavelength section at different locations of the long-span cable-stayed bridge is depicted when a settlement of 5 mm occurs in the left auxiliary pier. The figure illustrates that when the auxiliary piers settle, the vertical deformation primarily occurs at the location of the left side span and the left tower. Specifically, the vertical deformation of the left side span is concentrated in the 100m~450m wavelength section, with the maximum value of the wavelength decomposition deformation occurring around 200 m. Notably, the settlement of auxiliary piers has a lesser impact on the deformation at the bridge tower position.

4.4. The Mapping Relationship between Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge and Track Deformation

4.4.1. Temperature Difference between Cable and Beam

The impact of the temperature difference in cable-stayed beam on the vertical deformation of large-span cable-stayed bridges is notably significant.

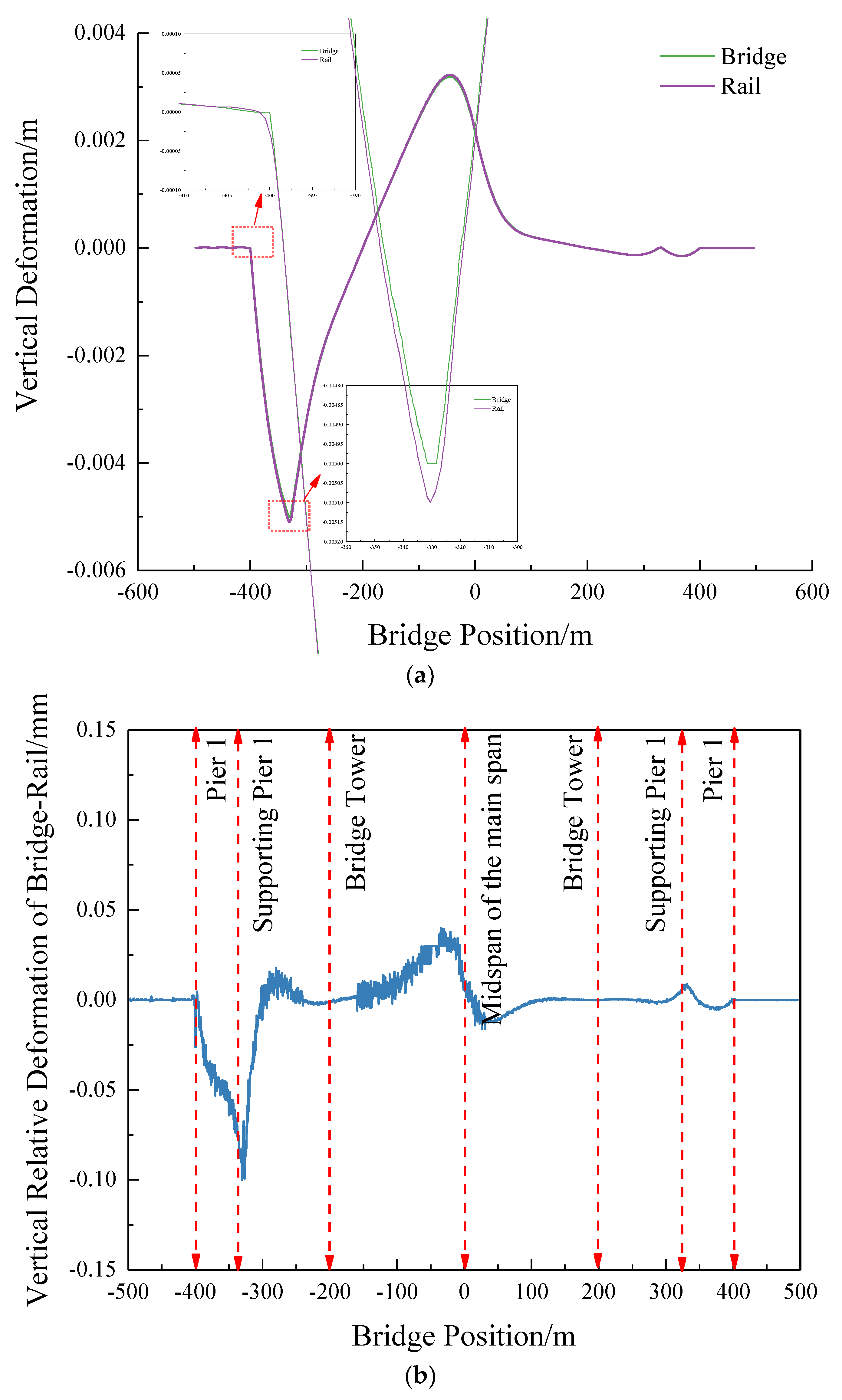

Figure 16 illustrates the mapping relationship between vertical deformation and rail deformation of the large-span cable-stayed bridge under the condition of a 15 ℃warming of the cable-stayed cables.

From the figure, the maximum vertical deformation occurs at the midpoint of the main span when the cable-stayed cables are warmed, and there is a distinct folding angle observed at the location of the bridge tower. Upon comparing the vertical deformation of the rail surface with that of the bridge, a slight deviation is evident between the main span and the bridge tower, measuring less than 1mm. The deformation in the rest of the positions remains relatively consistent. This observation suggests that the vertical deformation of the rail surface under the influence of the temperature difference in the cable-stayed beam is essentially consistent with the deformation of the cable-stayed bridge.

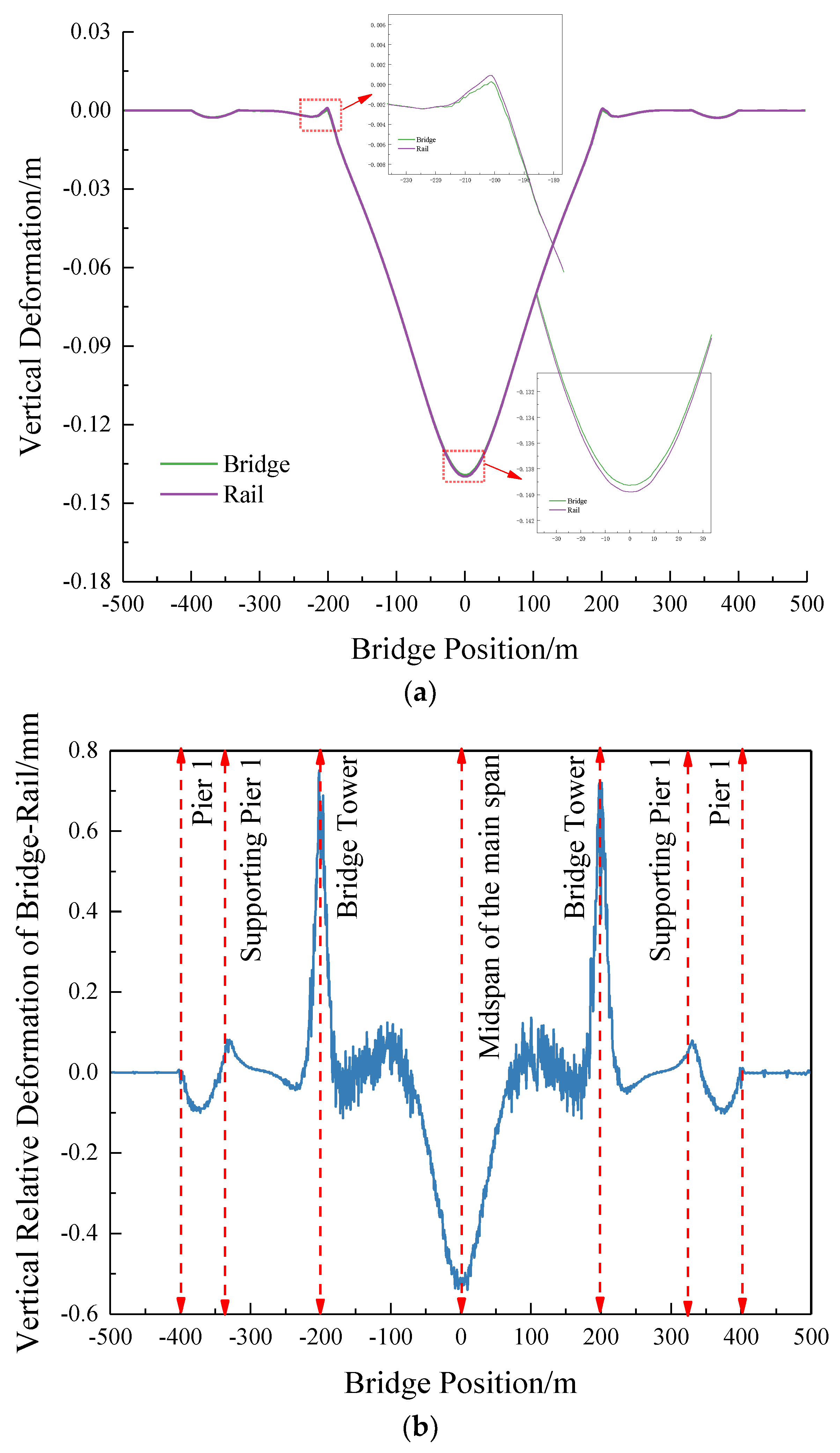

4.4.2. Settlement of Auxiliar Pier

For subsidiary pier settlements of less than 200m in long-span cable-stayed bridges, a significant proportion is attributed to short-wave deformations. The mapping relationship between track deformation and bridge deformation is examined by considering a 5mm settlement of the left span auxiliary pier, as depicted in

Figure 17.

From the figure, it is apparent that when the auxiliary pier settles by 5 mm, folding corners become evident at the beam ends, auxiliary piers, and the mid-span location of the main span. While there is a slight deviation between the track surface deformation and the bridge deck deformation at this location, impacting smoothness, overall, the two deformations remain relatively consistent. This suggests that when the auxiliary pier settles by 5mm, the vertical deformation of the rail surface aligns closely with the deformation of the cable-stayed bridge.

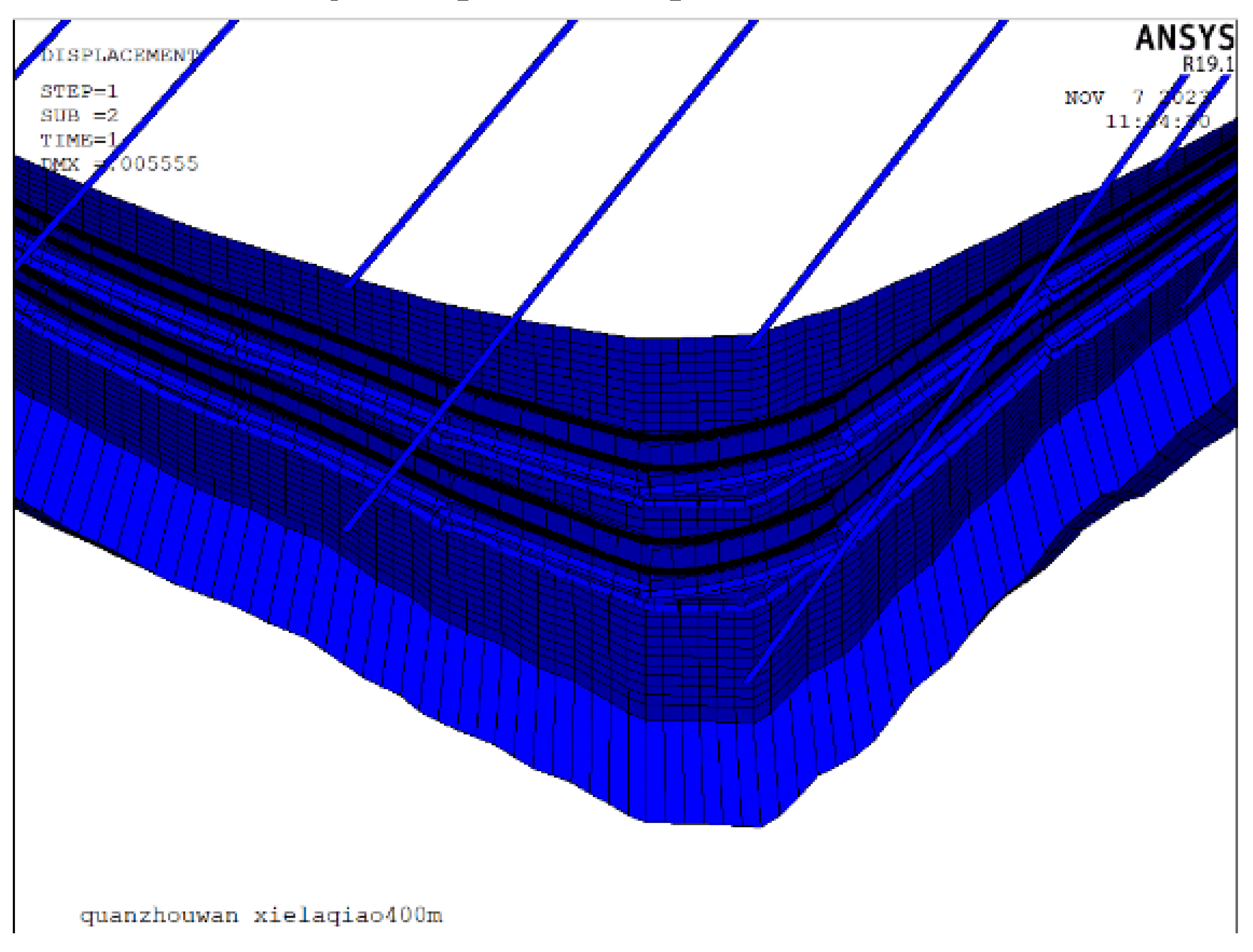

In

Figure 18, the cloud picture of bridge deck deformation and track deformation at the settlement location of the auxiliary pier is presented. The figure indicates a more pronounced vertical folding angle at the location of the auxiliary pier settlement. Notably, there is an evident difference in deformation between the track plate and base plate. Based on these observations, it is advisable to focus on the conditions of track service, especially at locations where there is a sudden change in abutment and other stiffness during the operational period.

5. Simplification of Train Dynamic Simulation Model based on Deformation Wavelength Characteristics of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges

5.1. Overview

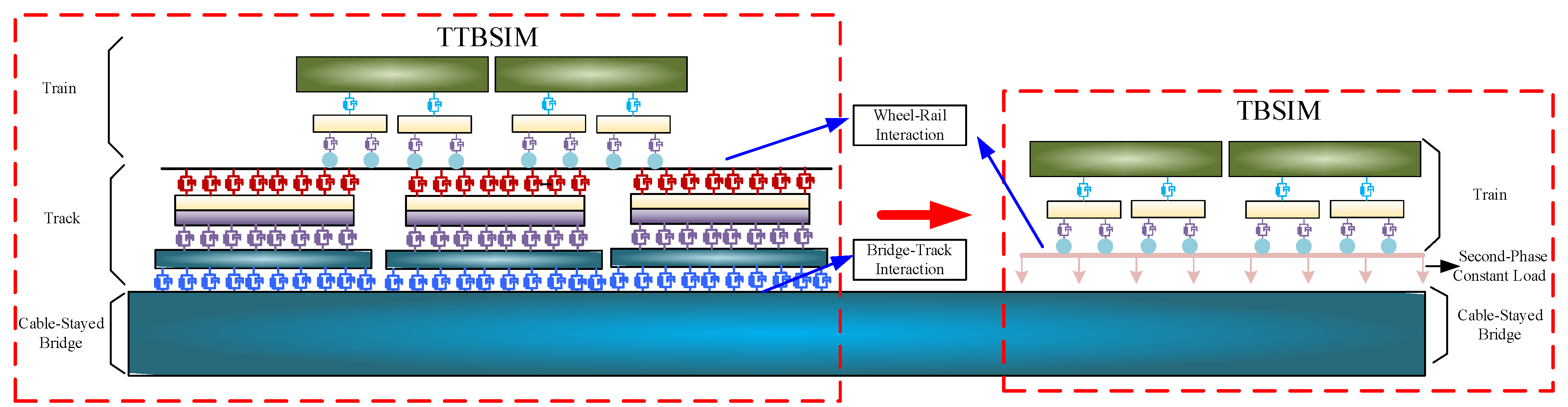

At present, most scholars have explored the effect of vertical deformation of long-span cable-stayed bridge on the car body vibration response by establishing the Train-Track-Bridge dynamic coupling simulation model. Although the dynamic response of bridge deformation to train can be analyzed through Train-Track-Bridge dynamic simulation, considering the large span of long-span bridge and the small load step of dynamic simulation calculation program, it is difficult to complete the research on the response of bridge deck deformation to train vibration under complex load conditions. Considering the track structure, the computational efficiency of dynamic simulation is reduced, and the complexity of Train-Bridge dynamic simulation model is increased. According to the analysis of the upper section, the vertical deformation of the long-span cable-stayed bridge can be mapped 1:1 to the deformation of the rail under complex loads. And the rail can completely follow the deformation of the long-span cable-stayed bridge floor. Therefore, the Train-Track-Bridge dynamic coupling simulation theory can be simplified. And the track structure can be simplified as a constant load. The Train-Bridge dynamic coupling simulation model is used to calculate the vehicle vibration response when the train passes the long-span cable-stayed bridge.

The accuracy of the Train-large-span cable-stayed Bridge dynamic simulation model is verified under conditions of track random irregularity, tension cable heating in lONG-span cable-stayed bridges, and auxiliary pier settlement deformation. This verification is conducted by comparing the vehicle vibration response calculated using the TTBSIM model and the TBSIM model.

5.2. Train Dynamic Response Simulation Model

5.2.1. Train-Track-Bridge Dynamic Coupling Model

In the dynamic coupling simulation model for the train-rail-bridge system, a two-system suspension multi-rigid body model with a total of 35 degrees of freedom is selected for the vehicle. The parameters of the vehicle model are sourced from literature [

19]. The track and bridge models are implemented using the discrete finite element method for finite element calculations, as shown in

Figure 19.

The train-track relationship is determined by the wheel-rail contact geometry and the resulting interaction forces[

20,

21]. The wheel-rail contact geometry is computed using the trace method, and the Hertz nonlinear elastic contact theory is applied for calculating the wheel-rail normal force. Longitudinal, transverse, and spin creep-slip forces between wheel tracks are initially solved using Kalker’s nonlinear modified creep theory.

The interaction relationship between the track and bridge is determined based on the line bridge action node numbers of the track structure and bridge structure. Numerical interpolation is employed to calculate the line bridge interaction forces and displacements. The vibration equations of the coupled dynamic model for the train-rail-bridge system are solved using the Newmark-β method, with a displacement convergence condition set at 10

-7m[

22].

5.2.2. Train -Bridge Dynamic Coupling Model

In the train-bridge dynamic coupling simulation model, the consideration of track structure parametric vibration effects is omitted. Instead, the track structure is simplified and applied to the bridge main beam as a second-phase constant load, as shown in

Figure 19.

The wheel-rail contact model in the train-bridge system utilizes a faster calculation method for the wheel-rail close-fitting model [

23], and the creep-slip force between the wheel and rail is initially determined based on the Kalker nonlinear correction creep-slip theory. For the vehicle, a two-system suspension multi-rigid body model with a total of 23 degrees of freedom is selected. The bridge model employs the discrete finite element method to establish the finite element calculation model. The vibration equations of the coupled dynamic model for the train-bridge system and the displacement convergence conditions are adopted from the train-track-bridge dynamic coupling model.

5.3. Train Vibration Response under Different Irregularity Excitation

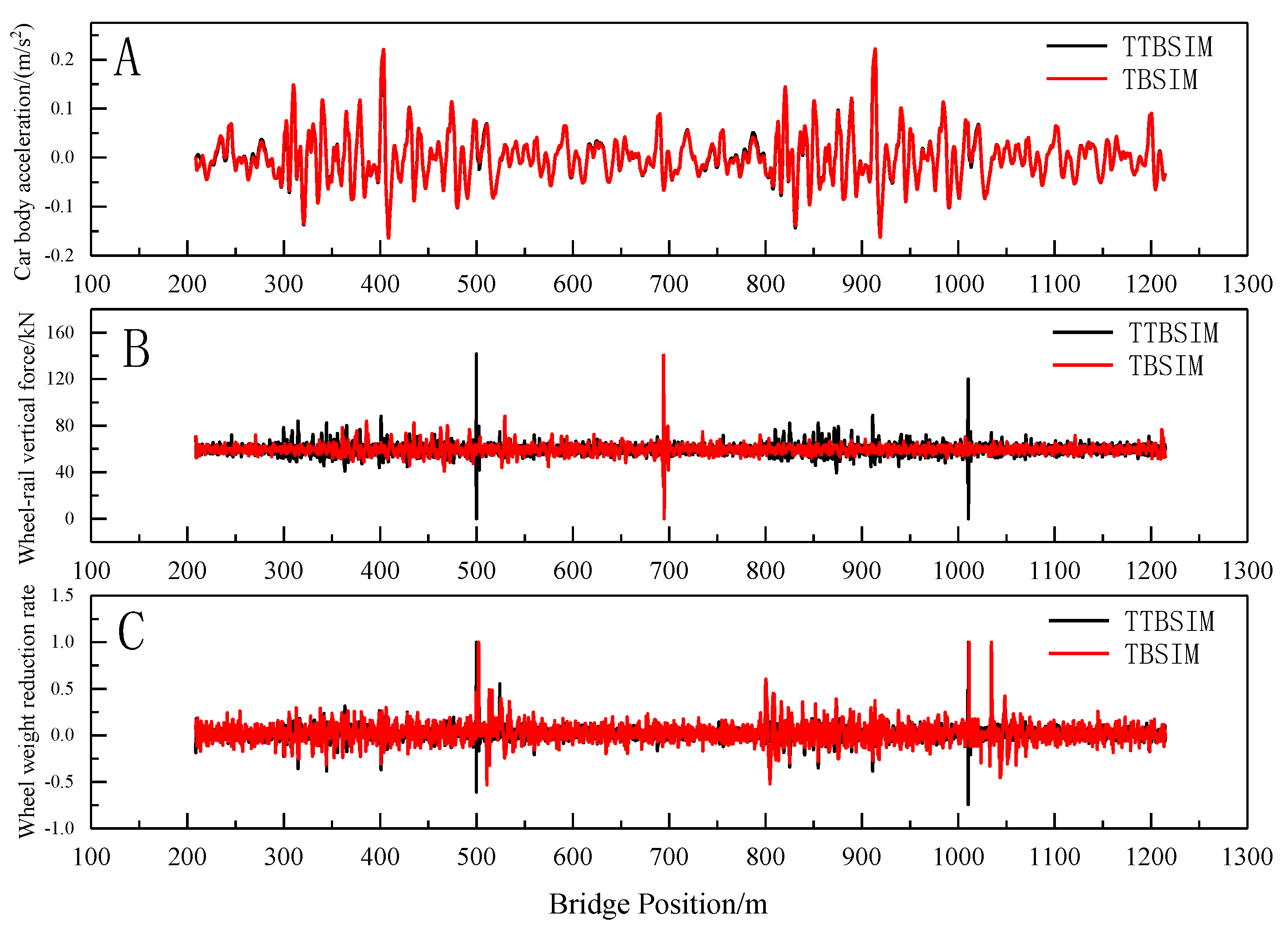

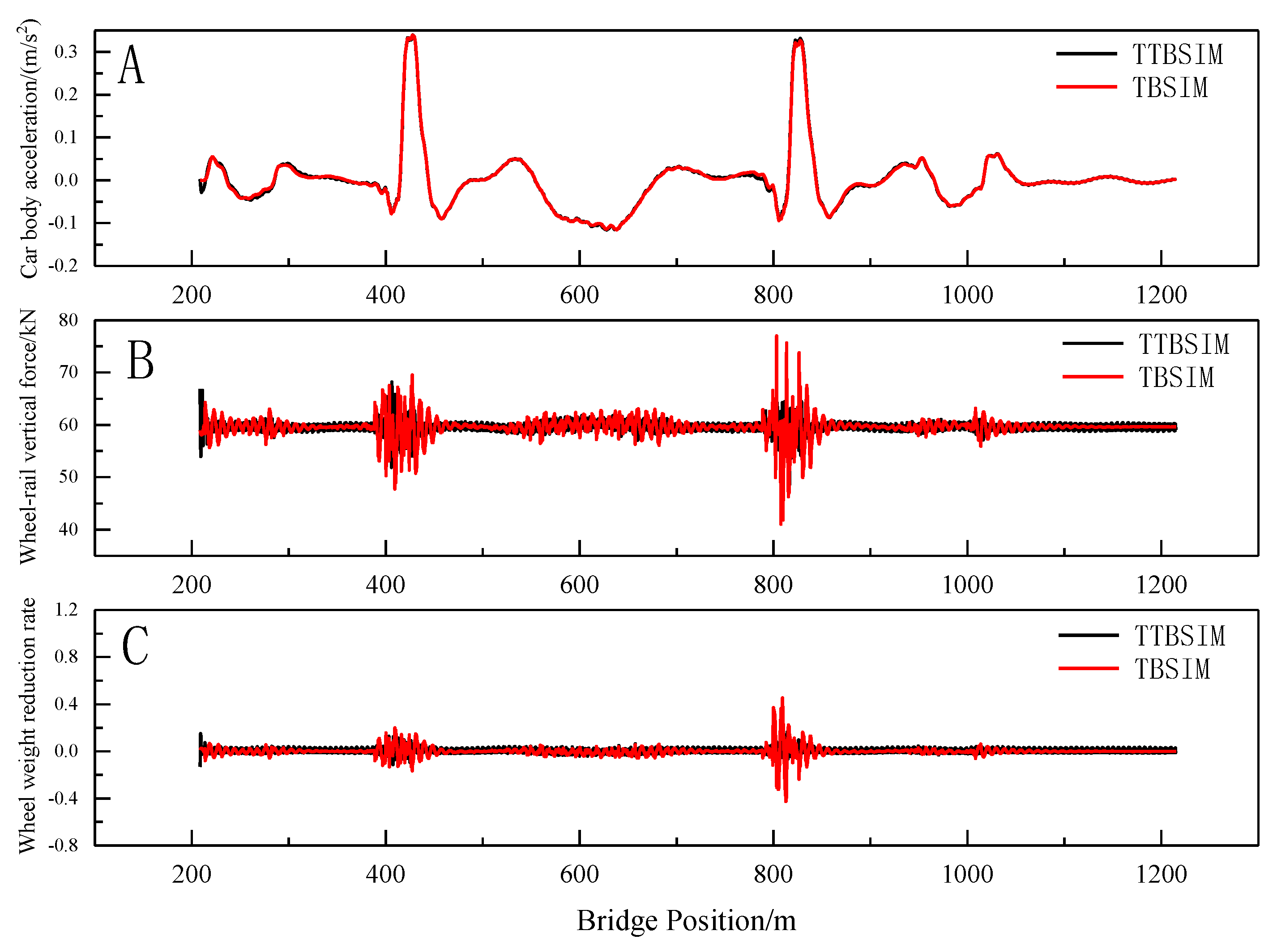

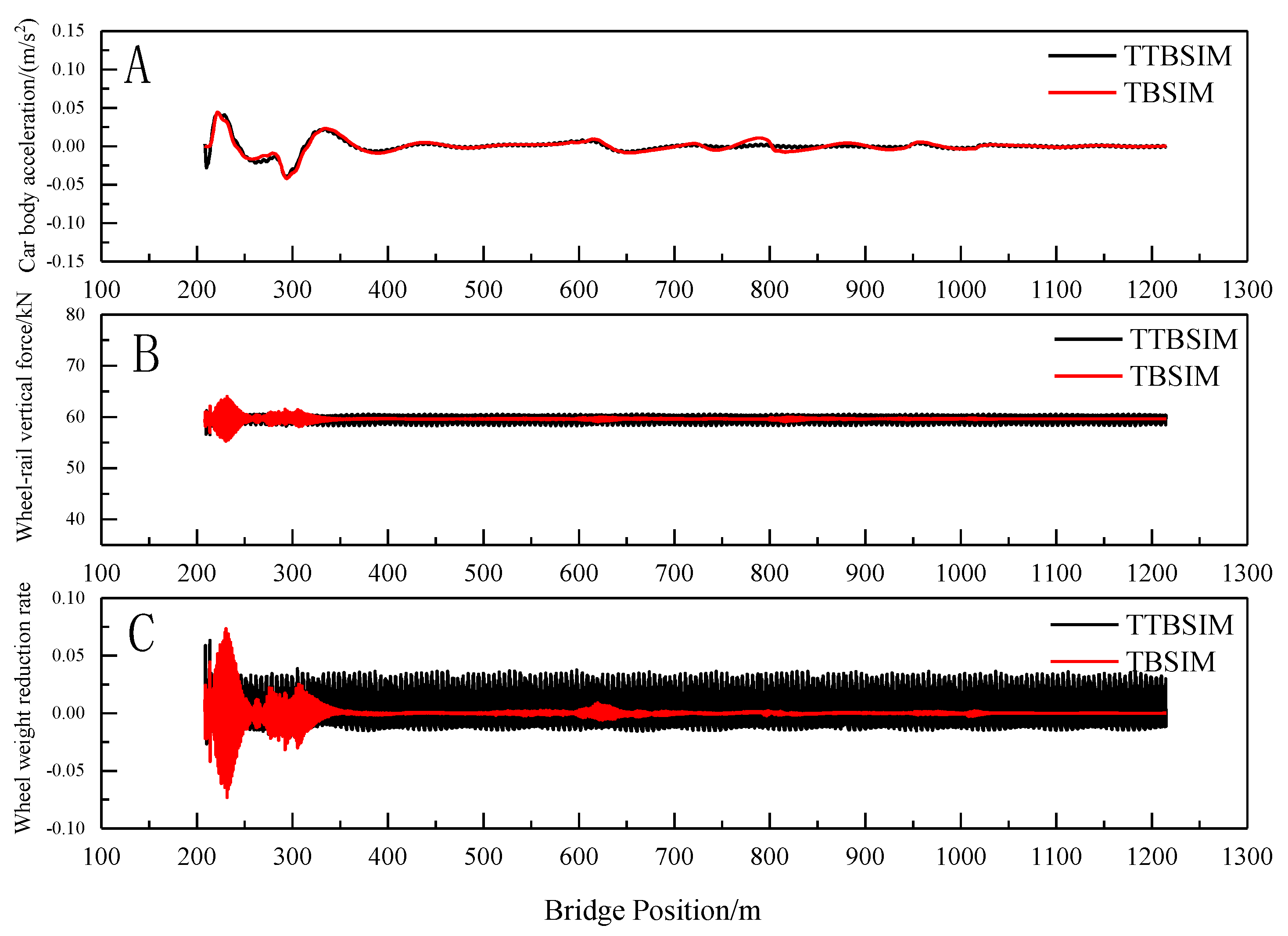

Under the influence of track random unevenness, temperature-induced deformation of the cable beam, and settlement deformation of the auxiliary pier, the TTBSIM and TBSIM power coupling simulation models were utilized to calculate the vertical acceleration of the car body, wheel-rail vertical force, and wheel-weight reduction rate during the entire process of the train entering and exiting the bridge, as illustrated in

Figure 20,

Figure 21 and

Figure 22.

From the figure, it is evident that when comparing the train vibration response under different excitation conditions, the distribution patterns of car body vertical acceleration calculated by both the TTBSIM model and the TBSIM model are essentially consistent. Similarly, the distribution patterns of wheel-rail vertical force and wheel weight reduction rate align closely. Notably, locations with sudden stiffness changes, such as the bridge tower, exhibit higher values for wheel-rail vertical force and wheel weight reduction rate as obtained from the train-bridge dynamic coupling model.

The long-wave vertical deformation of large-span cable-stayed bridges significantly influences the vibration acceleration of the car body and, consequently, affects ride comfort. To calculate the impact of this vertical deformation on the acceleration of the train body, a train-bridge dynamic coupling model is employed. In this model, the track structure is simplified as a second-phase constant load applied to the main beam. This simplification not only reduces model complexity but also enhances the computational efficiency of the program.

6. Conclusions

(1) For the BT, LT and USBT, if the minimum wavelength of bridge deformation exceeds 6, 10, and 16m, respectively, the rail deformation can accurately mirror the bridge deformation. Otherwise, it becomes essential to establish a comprehensive line-bridge model to accurately capture rail deformation.

(2) The minimum wavelength of a long-span cable-stayed bridge tends to decrease with an increase in the number of auxiliary piers and a decrease in the cable-stay stiffness ratio under typical loading conditions. While the addition of auxiliary piers in long-span cable-stayed bridges can effectively minimize mid-span displacements of the bridge towers and main spans, it does impact the smoothness of long waves in the bridge pier area. The vertical deformation wavelength range for long-span cable-stayed bridges with main spans ranging from 200 m to 600 m is observed to be between 21.38 m and 1270.74 m.

(3) The deformation of a cable-stayed bridge is primarily influenced by wavelengths greater than 200 m under the influence of overall loads such as temperature and overall settlement. However, during the ingress and egress of trains, as well as local loads like single auxiliary pier settlement, there may be vertical deformations with a wavelength of approximately 200 m near the piers, impacting the overall smoothness of the bridge’s long waves.

(4) Based on the line-bridge mapping relationship and the vertical deformation wavelength range of cable-stayed bridges, a comparison was made between the train vibration responses of the TBSIM model and the TTBSIM model under various excitations. The simulation results were found to be essentially consistent. The impact of the vertical deformation of a long-span cable-stayed bridge on the train’s vibration response can be accurately calculated using a train-bridge dynamic coupling model. In this model, the track structure is simplified and considered as the second-phase constant load, contributing to improved computational efficiency.

Author Contributions

Methodology and formal analysis, Z.P.(Zhiqiang Pang),M.G.(Mangmang Gao); software, G.L.(Guolong Li); formal analysis, J.Y.(Jingjing Yang); writing-review and editing, F.Y.(Fei Yang). All authors have readand agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Research and Development Project of China National Railway Corporation LTD, grant numbaer K2021G020, Science and Technology Research and Development Project of China Railway Research Institute Group Co., LTD, grant number 2023YG020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mao, W.-Q.; Hu, X.-W. Latest Developments and Prospects for Long-Span Bridges in China. Bridge Constr. 2020, 50, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bie, Y.; Xiao, H.; Shu, S. Overall Design of Hangzhou Bay Sea-Crossing Railway Bridge. Bridge Constr. 2023, 53, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Research on the Overall Design and Key Technology of Hangzhou Bay Cross-Sea Railway Bridge. J. Railw. Eng. Soc. 2022, 39, 7–12, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, B. Study on the Design Scheme of the Main Channel Bridge of the New Bream Yu Zhou Yangtze River Bridge for Anjiulong Railway. World Bridge 2018, 46, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wen, W. Railway Bridges in China (1980-2020); China Railway Publishing Company Limited: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-G.; Guo, H.; Zhao, X.-X. Analysis of the Overall Design Parameters of the Main Channel Bridge of Hutong Yangtze River Bridge. Bridge Constr. 2015, 45, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Sheng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, T. Experimental Study on Vibration Characteristics of Ballastless Tracks on Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge in High Speed Railway. Tumu Gongcheng Xuebao/China Civ. Eng. J. 2023, 56, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Sheng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, T. Effect of Reverse Bending Deformation of Large-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge on Ballastless Tracks’ Behaviors.

- Sheng, X.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, A.; Qin, Y. Ganjiang Bridge: A High-Speed Railway Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge Laying Ballastless Tracks. Struct. Eng. Int. 2021, 31, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ren, Z.; Zheng, W.; Liu, W.; Li, D.; Ma, G. Mechanical Behavior and Track Geometry Evaluation of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges with Ballastless Tracks. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yan, M.; Li, X.; Sheng, X.; Gao, Y.; Yu, Z. Deformation Adaptability of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge and Ballastless Track Structure. Zhongguo Tiedao Kexue/China Railw. Sci. 2019, 40, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhao, W.; Gao, M.; Sun, J. Static Measurement Method and Control Standard for Long-Wave Irregularity of High-Speed Railway Track during Operation Period. Zhongguo Tiedao Kexue/China Railw. Sci. 2020, 41, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gao, M.; Zhao, W.; Li, G.; Ke, Z.; Meng, J. Simplified Analysis Method of Car-Body Vibration Acceleration on Bridge Based on Long-Span Bridge Deformation. Zhongguo Tiedao Kexue/China Railw. Sci. 2023, 44, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q. Random irregularity of track on long-span bridge and its combination with bridge deformation. Master, Southwest Jiaotong University, 2024.

- Song, G.-H.; Gao, M. Cause Analysis and Control Index Study of Periodic Height Irregularity on Simple Supported Beam Bridge of High-Speed Railway. Railw. Constr. 2019, 59, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-X.; Li, S.; Chen, R. Characteristic Wavelength Analysis of Track Irregularity Spectrum on Simply-Supported Beam Bridge of High-Speed Railway. Railw. Constr. 2021, 61, 123–125, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Shi, X.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y. Research on the Influence of Geotextile and Elastic Cushion on the Static Performance of Ballastless Track on Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Railway Administration TB 10095-2020 Code for Design of Railway Cable-Stayed Bridges 2020.

- Gao, M.; Li, G.; Yang, F.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; You, M. Vertical Coupling Dynamic Analysis Method and Engineering Application of Vehicle-Track-Substructure Based on Forced Vibration. Zhongguo Tiedao Kexue/China Railw. Sci. 2021, 42, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Han, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ling, L.; Zhu, S. Train–Track–Bridge Dynamic Interaction: A State-of-the-Art Review. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2019, 57, 984–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-X.; Zhai, W.-M.; Yang, J.-Z.; Zhao, H.-Y. Train-Track-Ground Coupling Numerical Method for Railway Traffic Induced Ground Vibration. Zhendong Gongcheng Xuebao/J. Vib. Eng. 2008, 21, 488–492. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, M.; Ma, L.; Xuan, Y.; Li, H. Train-Bridge Coupled Vibration of Hutong Yangtze River Bridge’s Approach Bridge. J. Vib. Shock 2018, 37, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Tian, Y.; Xia, H. A Train-Bridge Dynamic Interaction Analysis Method and Its Experimental Validation. Engineering 2016, 2, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Finite models of track structure: (a) the ballasted track; (b) the longitudinal ballastless track; (c) the unit ballastless track.

Figure 1.

Finite models of track structure: (a) the ballasted track; (b) the longitudinal ballastless track; (c) the unit ballastless track.

Figure 2.

The Relative Deformation between Rails and Bridges.

Figure 2.

The Relative Deformation between Rails and Bridges.

Figure 3.

The Vertical Deformation between the Rail and Bridge: (a) BT; (b) LT; (c) USBT.

Figure 3.

The Vertical Deformation between the Rail and Bridge: (a) BT; (b) LT; (c) USBT.

Figure 4.

The finite element model of long-span cable-stayed bridges.

Figure 4.

The finite element model of long-span cable-stayed bridges.

Figure 6.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 6.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 7.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 7.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 8.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 8.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 9.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 9.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 10.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 10.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 11.

Elevation arrangement of large-span cable-stayed bridge across the sea (m): (a) overall bridge diagram (m); (b) steel-concrete composite beam cross-section (mid span) (mm); (c) steel-concrete composite beam cross-section (bridge tower) (mm).

Figure 11.

Elevation arrangement of large-span cable-stayed bridge across the sea (m): (a) overall bridge diagram (m); (b) steel-concrete composite beam cross-section (mid span) (mm); (c) steel-concrete composite beam cross-section (bridge tower) (mm).

Figure 12.

Finite element model of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge-Ballastless Track: (a) overall Bridge-Ballastless Track model; (b) Mid-span section of main span; (c) Cable-stayed bridge beam end section.

Figure 12.

Finite element model of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge-Ballastless Track: (a) overall Bridge-Ballastless Track model; (b) Mid-span section of main span; (c) Cable-stayed bridge beam end section.

Figure 13.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 13.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 14.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 14.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 15.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 15.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge.

Figure 16.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge: (a) The vertical deformation; (b) Vertical Relative Deformation of Bridge-Rail.

Figure 16.

The vertical deformation distribution of the cable-stayed bridge: (a) The vertical deformation; (b) Vertical Relative Deformation of Bridge-Rail.

Figure 17.

The Bridge deformation and rail deformation under the action of supporting pier settlement: (a) The vertical deformation; (b) Vertical Relative Deformation of Bridge-Rail.

Figure 17.

The Bridge deformation and rail deformation under the action of supporting pier settlement: (a) The vertical deformation; (b) Vertical Relative Deformation of Bridge-Rail.

Figure 18.

The track-bridge deformation at auxiliary pier location.

Figure 18.

The track-bridge deformation at auxiliary pier location.

Figure 19.

TTBSIM and TBSIM.

Figure 19.

TTBSIM and TBSIM.

Figure 20.

Train vibration response under random track irregularity excitation.

Figure 20.

Train vibration response under random track irregularity excitation.

Figure 21.

Train vibration response under the excitation of cable-girder temperature difference.

Figure 21.

Train vibration response under the excitation of cable-girder temperature difference.

Figure 22.

Train vibration response under settlement and deformation excitation of auxiliary pier.

Figure 22.

Train vibration response under settlement and deformation excitation of auxiliary pier.

Table 1.

Ratio of side span to main span diameter of double-tower cable-stayed bridges.

Table 1.

Ratio of side span to main span diameter of double-tower cable-stayed bridges.

| Type of Main Beam |

Side Span/Main Span |

Value |

| Steel Beam |

0.30~0.40 |

0.35 |

| Steel-Concrete Combination Beam |

0.40~0.50 |

0.45 |

| Concrete Beam |

0.40~0.50 |

0.45 |

Table 2.

Ratio of side span to main span diameter of double tower cable-stayed bridges.

Table 2.

Ratio of side span to main span diameter of double tower cable-stayed bridges.

| Tower Height/Main Span |

Value |

| 0.2~0.33 |

0.27 |

Table 3.

The distance between cables on the main beam and the bridge tower.

Table 3.

The distance between cables on the main beam and the bridge tower.

| Type of Main Beam |

Main Beam |

Tower |

| Value Range /m |

Value/m |

Value Range /m |

Value/m |

| Steel Beam |

8~15 |

12 |

2~5 |

3.5 |

| Steel-Concrete Combination Beam |

8~15 |

12 |

2~5 |

3.5 |

| Concrete Beam |

6~10 |

8 |

2~5 |

3.5 |

Table 4.

Structural schemes of long-span cable-stayed bridge with main span 200~600 m.

Table 4.

Structural schemes of long-span cable-stayed bridge with main span 200~600 m.

| Span of Main Beam/m |

200 |

400 |

600 |

| Deflection under move load/m |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

| Material of main beam |

concrete beam |

concrete beam |

Steel-concrete composite beam |

Steel beam |

Steel-concrete composite beam |

| Span of the side span/m |

100 |

180 |

180 |

210 |

270 |

| Height of the bridge tower/m |

54 |

108 |

108 |

162 |

162 |

| Spacing of cables/m |

Main beam |

The edge across the no-stay cable area |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Stay cables across side spans |

8 |

7 |

10.5 |

8 |

10.7 |

| The non-stay cables of the bridge tower |

15 |

19 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

| Stay cables in the main span |

8 |

8 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

| The no-stay cable in the span |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Bridge tower |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

| Height of the main beam/m |

3.84 |

3.84 |

5.76 |

| Width of bridge deck/m |

14 |

14 |

14 |

18 |

18 |

| Auxiliary span/m |

First |

0 |

0 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

54 |

0 |

0 |

54 |

0 |

0 |

63 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

| Second |

0 |

40 |

30 |

0 |

72 |

54 |

0 |

72 |

54 |

0 |

84 |

63 |

0 |

108 |

80 |

| Third |

100 |

60 |

40 |

180 |

108 |

72 |

180 |

108 |

72 |

210 |

126 |

84 |

270 |

162 |

110 |

Table 5.

Minimum and maximum wavelengths of deformation of 200m cable-stayed bridges.

Table 5.

Minimum and maximum wavelengths of deformation of 200m cable-stayed bridges.

| The Span of The Main Span/m |

Wavelength Type |

Minimum Wavelength/m |

Maximum Wavelength /m |

| Cable-Beam Stiffness Ratio |

0.001 |

100 |

0.001 |

100 |

| 200 |

Three-span |

63.48 |

170.62 |

692.88 |

1268.29 |

| Five-span |

31.74 |

151.37 |

756.29 |

1261.91 |

| Seven-span |

21.38 |

122.31 |

599.79 |

1260.02 |

| 400 |

Three-span |

38.64 |

304.22 |

1127.19 |

1268.81 |

| Five-span |

28.57 |

266.57 |

1053.87 |

1263.92 |

| Seven-span |

27.00 |

242.58 |

948.30 |

1262.22 |

| 600 |

Three-span |

61.50 |

419.12 |

1237.67 |

1270.37 |

| Five-span |

38.80 |

370.69 |

972.44 |

1270.74 |

| Seven-span |

39.87 |

345.21 |

904.67 |

1270.12 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).