1. Introduction

The use of anti-obesity medications (AOMs) is on the rise in the United States with the introduction of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists to the pharmaceutical market. In clinical studies GLP-1 agonists have been shown to impact patients eating habits by reducing appetite, slowing down gastric emptying, and shifting food preferences [

1,

2]. GLP-1 agonists have demonstrated a plethora of potential benefits, including treatment for diabetes, weight loss, and treatment for other obesity-related conditions [

3]. With continued success in clinical trials, medications such as semaglutide, liraglutide and tirzepatide (which also features glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, a second key ingredient) are quickly becoming popular treatments for weight loss [

4]. GLP-1 agonist use has been increasing in prevalence with about 12% of US adults reporting having taken at least one dose of a GLP-1 medication and 6% reporting active use, along with 59% adults claiming to have heard “some” or “a lot” about these medicines [

5]. Our study explores whether the intake of this medication also has a significant relationship with food waste.

Food waste is a pressing global issue with significant environmental, economic, and social implications [

6]. This waste not only represents a substantial inefficiency in the food supply chain but also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and depletes natural resources [

7]. Various factors contribute to food waste, including consumer behavior, improper storage, and over-purchasing [

8,

9], which are each intricately intertwined with consumers’ dietary decisions. With the increasing prevalence of anti-obesity medications, which are known to alter eating habits by reducing appetite and changing food preferences [

10], there is a potential intersection between AOMs and food waste. As individuals on these medications may purchase and consume less food, and possibly change the types of food that they consume [

1,

2], understanding how these changes impact food waste is crucial. By examining this intersection, we hope to provide insights that could prepare new AOM patients with strategies for reducing food waste and help predict aggregate food waste trends as AOMs become more widely prescribed.

2. Materials and Methods

We surveyed 505 U.S. adults who reported current use of GLP-1 agonist medications. The self-administered online questionnaire focused on sociodemographic factors such as age, income, and race, as well as questions inquiring about changes in dietary habits, weight, and food waste since beginning the AOM. Human subjects’ approval was granted by the Ohio State University Internal Review Board (2024E0009) and all participants provided informed consent. Data were collected from respondents from throughout the United States during April 2024 via Qualtrics software with participants recruited via the Prolific recruitment platform. The questionnaire is available in the

Supplementary Materials as are the data used in the current analyses.

The focal (dependent) variable is a respondent’s answer to the question: “Indicate your level of agreement with the following statement (strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree): Since beginning this medication I have found I waste more of the food that I purchase.” Responses were coded as integers where strongly disagree was coded -2, somewhat disagree as -1, neither agree nor disagree as 0, somewhat agree as 1, and strongly agree as 2.

One key set of explanatory variables includes whether respondents indicated suffering from a list of known side effects associated with GLP-1 agonists since beginning the medication including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, constipation, injection site redness, low blood sugar or other side effects. Indicated side effects were coded as a 1 and all others as 0. Another set of explanatory variables include responses to a question about changes in consumption of particular food categories including carbohydrates, proteins, alcohol, healthy fats, fried foods, savory foods, sweet foods, fruits, vegetables, fish, meats, dairy, and pasta and rice. Participants could indicate that, since beginning the medication, they consumed more (coded 1), about the same amount (coded 0) or less (coded -1) of each food category. Another set of explanatory variables includes whether respondents started adherence to a particular dietary regimen since beginning the medication with the options being paleo, Atkins, Dukan, intermittent fasting, vegetarian, vegan, pescatarian, Mediterranean, Kosher, halal, low fat or other, with those who started such a diet since beginning the AOM coded as 1 and 0 otherwise.

Additional control variables include the type of medication (semaglutide, liraglutide, tirzepatide or other/unsure), the length of time on the medication (<90 days, 90-180 days, 181-365 days, or >365 days), and the respondent’s sex, age, education, race, ethnicity, employment status and medical insurance status. Respondent weight change since beginning the medication was strongly correlated with respondent length of time on medication, and hence was omitted to avoid multi-collinearity in the regression analysis and because weight change was not reported by all respondents.

The relationship between the dependent variable and the explanatory variables is assessed via ordinary least squares (OLS) regression where inferences concerning statistical significance are based upon robust standard errors. Given the inherently ordinal nature of the dependent variable, we also estimated an ordinal logit model, which leads to qualitatively similar inferences. For brevity and ease of interpretation, we present only the OLS results. All statistical work is conducted using Stata (version 18.0). Statistical significance is set at the 0.05 level with results at the 0.10 level deemed marginally significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

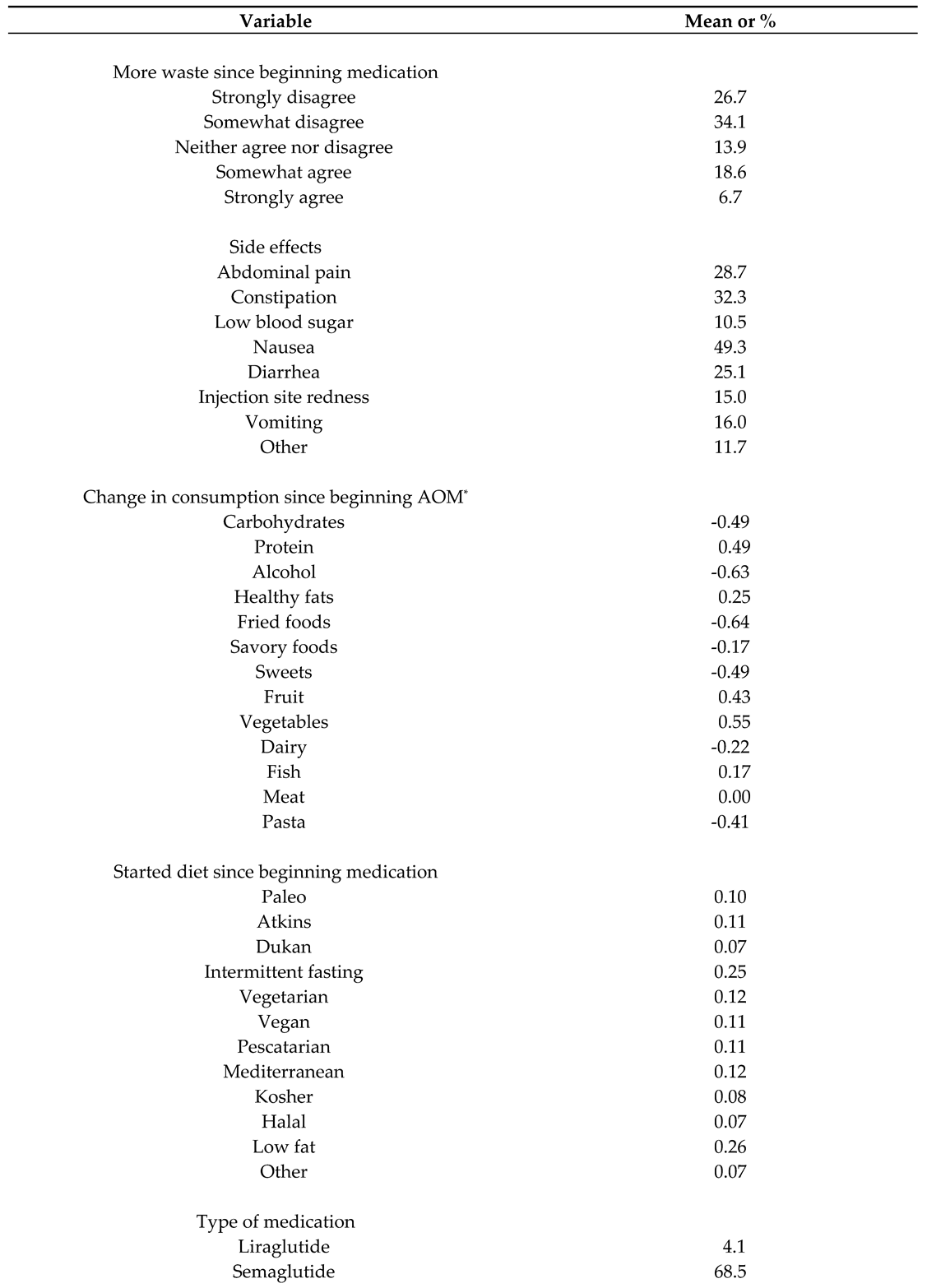

The sample of 505 U.S. consumers includes substantial demographic and economic diversity (

Table 1). In terms of racial composition 63.8% identify as white/Caucasian, 25.3% identify as Black or African American and 10.9% provide a different racial identification; in terms of ethnic identification, 9.3% identify as Hispanic or Latina/o. About half identify as male with about one-third reporting age less than 35. In terms of economics, about 20% report annual household incomes below

$50,000 while 76.8% report full time employment and 89.1% report having medical insurance. About 73% report having a bachelor’s degree or beyond.

The sample lists substantial dietary variation since beginning their AOM. Food categories that were eaten less since the onset of medication use include carbohydrates, pasta, alcohol, fried foods, savory foods, sweets, and dairy, while there was little movement in terms of meat consumption. Increased consumption was reported for all proteins, fish, healthy fats, fruit, and vegetables. The most popular diets started since beginning AOMs included low fat and intermittent fasting.

In terms of medication-related variables, about two-thirds of respondents reported semaglutide as their medication with more than a quarter reporting they had been on the medication for more than a year. The most frequently reported side effects from the medication include nausea (49%), constipation (32%), abdominal pain (29%) and diarrhea (25%).

3.2. Food Waste

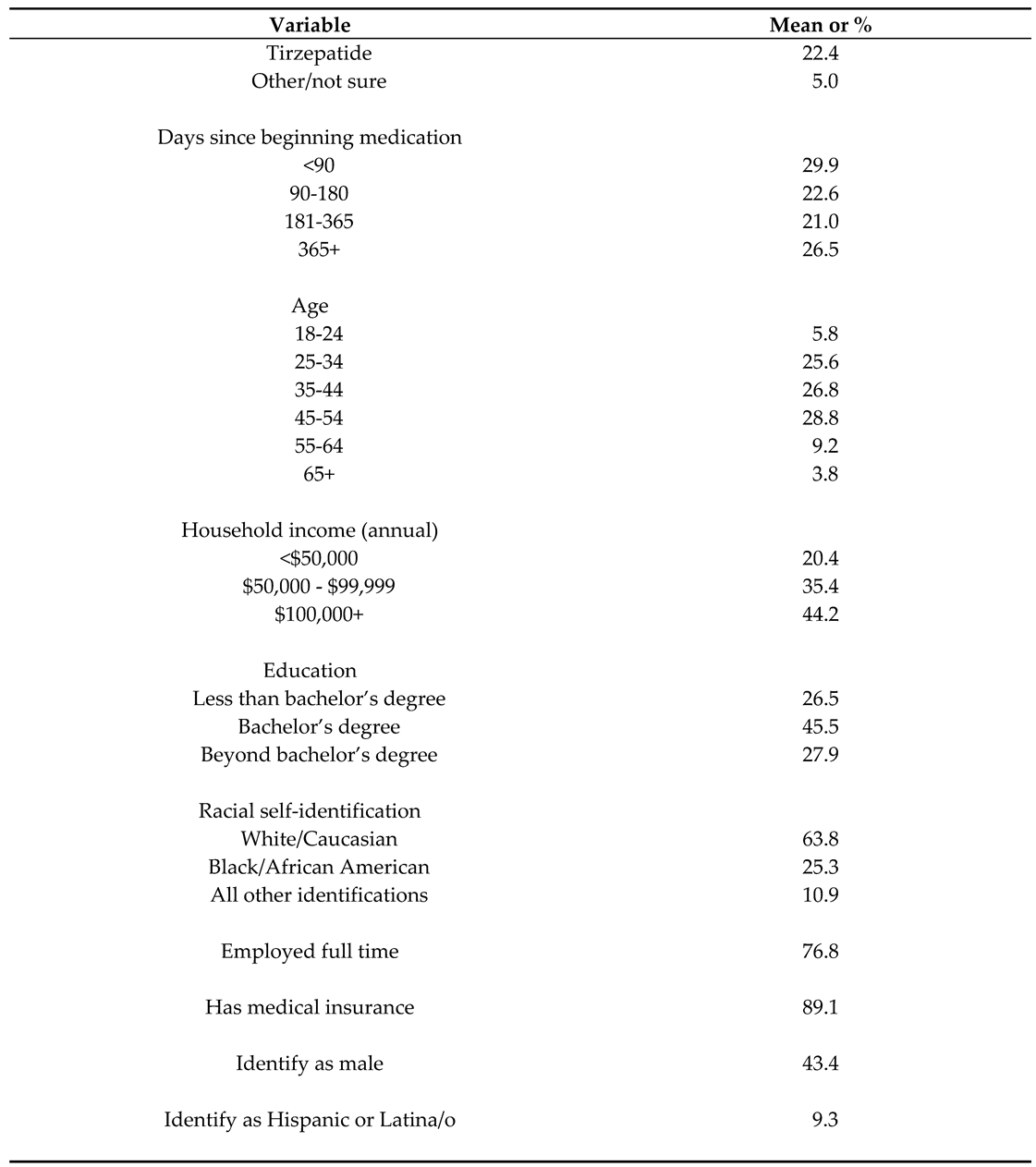

About one-quarter of respondents agreed with the statement that they waste more of the food they purchase since beginning their AOM, while about 61% disagree. The regression analysis (

Table 2) reveals that respondents with nausea are significantly more likely to report agreement, while those who have been taking the medication for more than a year are significantly less likely to voice agreement than those who began the medication less than 90 days ago. Respondents who report increasing their vegetable intake since beginning the medication are significantly less likely to report an increase in food waste, while those who have started a vegan diet since commencing use of an AOM are marginally less likely to agree. The only respondent demographic characteristic that is significantly associated with the food waste variable pertains to education level with those who have earned a bachelor’s degree having a significant negative relationship with the food waste variable as compared to those with more or less formal education. No other demographic or economic variables are significantly related to the food waste variable.

4. Discussion

The findings provide insight into the relationship between self-assessed changes in food waste since the onset of a respondent’s use of a GLP-1 medication and plausible drivers of such behavior. Notably, individuals who experienced nausea were significantly more likely to report an increase in food waste. This association suggests that adverse medication effects can have an impact on food consumption and waste patterns. Nausea should lead to a reduction in appetite and, hence, an increased likelihood of having food that is no longer desired and thus discarded, which contributes to food waste.

The number of days on medication is also significantly related to perceived changes in food waste with those with a longer duration of use reporting less agreement that food waste has increased since commencing medication. This pattern is consistent with an acclimation of food purchasing and preparation behaviors in light of new dietary demands and preferences.

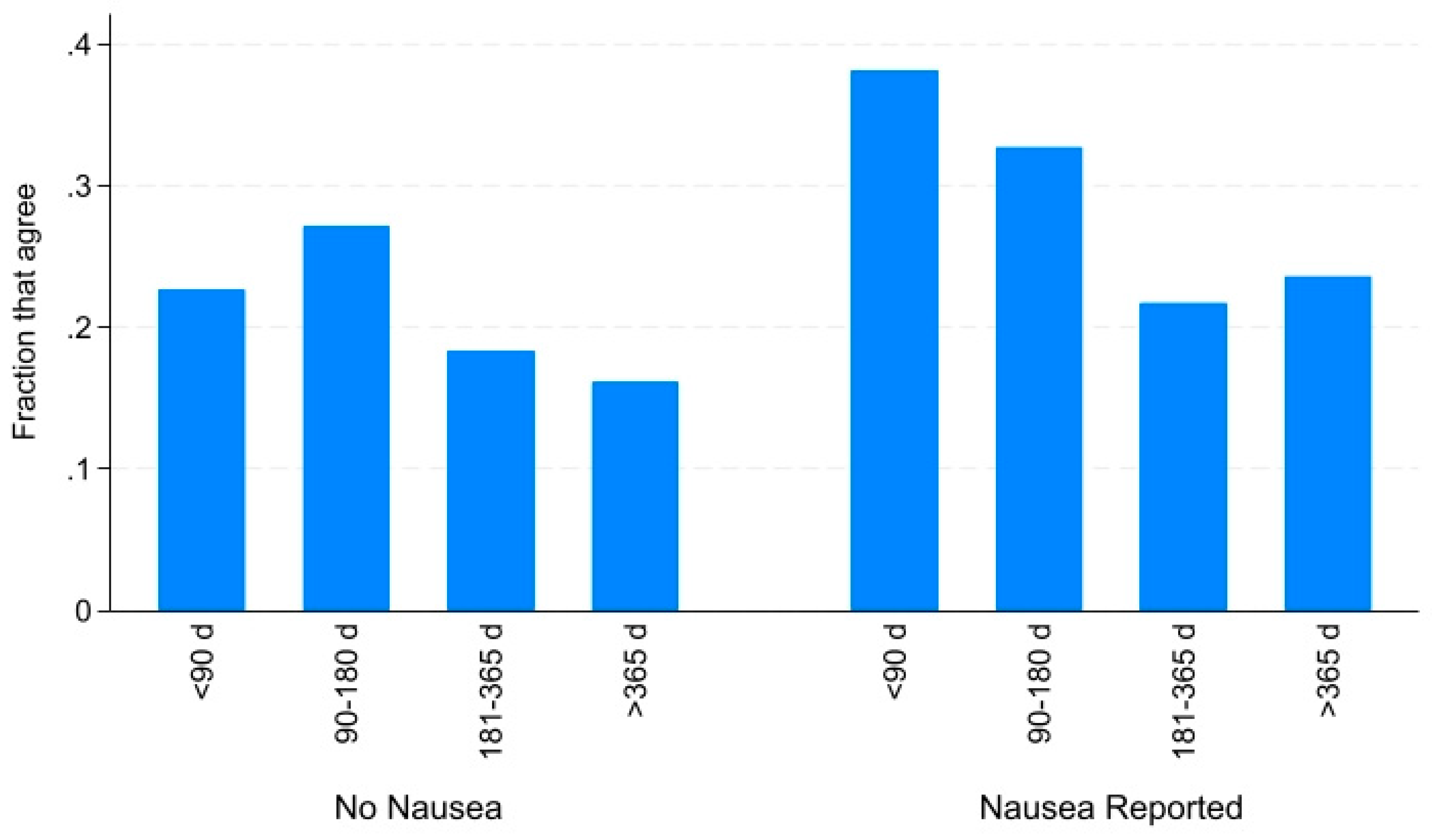

Figure 1 displays the fraction of the sample that agrees with the statement concerning increased food waste since medication onset by the duration of their experience with the medication. Whether the respondent reported the side effect of nausea or not, those who have been on their AOM for more than half a year report less agreement though the magnitude of the effect appears larger among those who also report nausea from taking the medication.

One conjecture is that more food is wasted during initial exposure to the medication due to changes in dietary preferences and habits. Indeed, we find in

Table 1 than the average diet of respondents changed to include more produce, protein, fish and healthy fats, and less alcohol, carbohydrates (including pasta), sweets, and dairy products. In particular,

Table 2 reveals that individuals who reported consuming more vegetables as part of their post medication dietary transition – either by reporting via the categorical variable as eating more vegetables or by reporting the commencement of a vegan diet – were significantly less likely to agree that they increased food waste since beginning GLP-1 medications. This suggests a potential increased vegetable consumption may help combat food waste for those beginning GLP-1 medications. Vegetables are among the most wasted of all food categories in the United States [

11]. Transitioning to a more vegetable intense diet may increase likelihood of incorporating these items into meals rather than discarding them. This observation is consistent with previous literature showing that healthy lifestyle changes – namely preparation of food inside the household – contributes to reducing food waste [

12].

5. Conclusions

Reducing food waste [

6] and carrying less weight [

13] are both supportive of improved sustainability. It would appear that there is an additional sustainability-supporting interaction between these trends in that only about a quarter of U.S. consumers report increasing food waste after taking anti-obesity medications, and this is further mitigated as patients are able to treat typical symptoms (nausea) and as they acclimate to the medication and the concomitant dietary changes over time. Hence, making new AOM patients aware that the uptake of the medication can lead to some additional waste, particularly if they suffer from nausea, may help them reduce expenditures on foods they will be unlikely to consume. Further, as more people turn to GLP-1 agonists over the coming years, we might look for impacts on the amount of food waste emerging from households so that models of food waste reduction goal attainment might be better calibrated.

This study is limited in several dimensions that should be addressed in subsequent research. First, greater granularity should be obtained concerning the amounts and types of food that are wasted as patients progress through AOM treatment. Second, a prospective study design, that assesses behavior prior to and then at different stages of medication use, would provide increased confidence in these results. Third, study designs that test messaging or other interventions designed to mitigate food waste among AOM patients would provide insights into approaches to enhance sustainability among this growing segment of the population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Consumer Survey, Data, Statistical code.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and B.R.; methodology, B.R.; software, J.M. and B.R.; formal analysis, J.M. and B.R.; investigation, B.R.; resources, B.R.; data curation, J.M. and B.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M. and B.R; writing—review and editing, J.M. and B.R.; visualization, B.R.; supervision, B.R.; project administration, B.R.; funding acquisition, B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC was funded by Ohio State University’s Van Buren fund (no grant number).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ohio State University (2024E0009, 5 January 2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Linda Jula for her assistance in administering the survey used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aldawsari M., Almadani F.A., Almuhammadi N., Algabsani S., Alamro Y., Aldhwayan M. The efficacy of GLP-1 analogues on appetite parameters, gastric emptying, food preference and taste among adults with obesity: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity. 2023 Dec 31:575-95. [CrossRef]

- Eren-Yazicioglu C.Y., Yigit A., Dogruoz R.E., Yapici-Eser H. Can GLP-1 be a target for reward system related disorders? A qualitative synthesis and systematic review analysis of studies on palatable food, drugs of abuse, and alcohol. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2021 Jan 18;14:614884. [CrossRef]

- Couzin-Frankel J. Obesity meets its match. Science. 2023 Dec;382(6676):1226-7. [CrossRef]

- Lafferty R.A., Flatt P.R., Irwin N. GLP-1/GIP analogs: potential impact in the landscape of obesity pharmacotherapy. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2023 Mar 24;24(5):587-97. [CrossRef]

- Montero, A., Sparks, G., Presiado, M., Hamel, L. KFF health tracking poll May 2024: the public’s use and views of GLP-1 drugs. 2024, May 10. Available online at: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/kff-health-tracking-poll-may-2024-the-publics-use-and-views-of-glp-1-drugs/ (accessed 25 August 2024).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. A National Strategy to Reduce Wasted Food at the Consumer Level. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Babbitt C.W., Neff R.A., Roe B.E., Siddiqui S., Chavis C., Trabold T.A. Transforming wasted food will require systemic and sustainable infrastructure innovations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2022 Feb 1;54:101151. [CrossRef]

- Schanes K., Dobernig K., Gözet B. Food waste matters-A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018 May 1;182:978-91. [CrossRef]

- Hebrok M., Boks C. Household food waste: Drivers and potential intervention points for design–An extensive review. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2017 May 10;151:380-92. [CrossRef]

- Friedrichsen M., Breitschaft A., Tadayon S., Wizert A., Skovgaard D. The effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly on energy intake, appetite, control of eating, and gastric emptying in adults with obesity. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2021 Mar;23(3):754-62. [CrossRef]

- Li R., Shu Y., Bender K.E., Roe B.E. Household food waste trending upwards in the United States: Insights from a National Tracking Survey. Journal of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. 2023 Jun;2(2):306-17. [CrossRef]

- Savelli E., Francioni B., Curina I. Healthy lifestyle and food waste behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2020 Mar 11;37(2):148-59. [CrossRef]

- Hallström E., Gee Q., Scarborough P., Cleveland D.A. A healthier US diet could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from both the food and health care systems. Climatic Change. 2017 May;142:199-212. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).