1. Introduction

Due to the rapid increase of the population, a shift of the market to fast fashion, and the consumers' sensitivity to low prices; the clothing consumption patterns are considered unsustainable all over the world, including in developed countries (Borusiak et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2013; MacArthur, 2017; McNeill & Venter, 2019; Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020; Yoon & Yoon, 2018). Many of today’s environmental problem is a direct consequence of human consumption (Fischer et al., 2021; Hosta & Zabkar, 2021; Vlastelica & Kosti, 2023). The world consumes 80 billion new pieces of clothing every year, and 73% of the clothes produced are estimated to end up in a landfill (Soyer & Dittrich, 2021). In addition to meeting the increased clothing demand and the consumer's high responsiveness to lower prices, the sector uses different chemicals, pesticides, fertilizers, and unethical manufacturing systems; this leads to a reduction of soil fertility, water pollution, and severe health problems related to exposure to toxic pesticides. For instance, cotton manufacturers worldwide use approximately $2.6 billion worth of pesticides every year (Muthukumarana et al., 2018). A similar study (Rausch & Kopplin, 2021b) states that Around 2791 million tons of CO2 emissions, and 118 billion cubic meters of water are consumed yearly. The sector accounts for 35.6% of the overall global energy consumption, and is expected to grow at an annual rate of 1.2%, produces 10% of the world’s carbon emissions (Muthukumarana et al., 2018), and 20% of all water pollution (Sudhakara Reddy & Kumar Ray, 2011), making it the second most pollution-releasing sector globally.

Since the root of environmental problems is highly associated with human consumption, it is advisable to overcome these environmental problems starting from the consumer level (Tantawi et al., 2009). One of the proposed concepts for overcoming environmental issues by involving consumers’ participation is sustainable consumption (Tanner & Kast, 2003). To achieve sustainability, the role of consumers is very essential (Rizkalla, 2018). In addition, consumers influence the industry through their product choices (Sheikh Qazzafi, 2019). Now consumers use the sustainability attribute to some extent as an evaluation criterion for their purchasing decision in addition to the product attribute (Kumar et al., 2021). According to (Zheng & Chi, 2015) 66.5% of US Customers are accounting for sustainable consumption intention. A study conducted in the UK (Young et al., 2010) found that 30% of consumers are very concerned but they are struggling to translate this into purchases. A study conducted in Kuwaiti found that the consumers have a low level of knowledge about the environmental impacts of the apparel and textile industry, and did have positive intentions to purchase environmentally sustainable apparel (ESA) in the future (Albloushy & Hiller Connell, 2019). According to (Amit Kumar, 2021) Indian consumers are aware of green apparel, have a positive attitude, and show a responsible purchase intention.

Furthermore, solid wastes are constantly growing due to the nature of fast fashion and short-lived style (Liang & Xu, 2018). Fore instances Americans produce an average of 16 million tons of textile and apparel waste every year, of which only 15% is recycled (Chi et al., 2021). In the UK clothing waste is estimated to be 2 million tons; of this, 63% (1.2 million tons) ends up in landfills (Hur & Cassidy, 2019). Clothing and textile wastes increased from 24 million tons in 2012 to 26.2 million tons in 2016. Therefore, there is an urgent need to make consumers change their patterns of consumption and encourage them to consume more sustainably. In order to decrease the impact of clothing on the environment, fast fashion companies invested in and advertised their sustainability commitments in efforts to satisfy the concerns of environmentally conscious consumers while continuously fostering over-consumption and making no attempt to change their business model (Bick et al., 2018; Carol Cavender, 2018). Market data indicate that, in 2021, the share of sustainable clothing within total sales in the global apparel market amounted to approximately 3.9% and is expected to increase up to 6.1% in 2026 (Vlastelica & Kosti, 2023). This is due to consumer engagement, so without truly consumers participating in the sustainability movement will not be achieved (Zheng & Chi, 2015). Hence, it is important to understand the purchase intention of the environmentally-conscious consumer in the context of apparel purchasing; the study intended to answer;

Do consumer consider sustainability attributes as an evaluation criteria for their purchasing decision?

Does environmentally responsible purchase intention matter for consumers when buying apparel products?

What are the factors that significantly affect Ethiopian consumers’ environmentally sustainable apparel product purchase intention and behavior?

To answer those questions, this study investigates the consumer’s most important attribute that they employ when they make a purchasing decision and analyzes it by using mean value to answer the first question. The relevance of potential environmentally responsible concerns of consumers in the context of apparel purchasing in the Ethiopian setting was examined to answer the second question. Finally, a structural equation model was employed to investigate the significant of each factor to the sustainable purchasing intention and behavior for the third research question.

Numerous studies (Lewis et al., 2017; Mariadoss et al., 2016; Moretto et al., 2018; H. G. Park & Lee, 2015; J. Park & Ha, 2014; M. J. Park et al., 2017; Sandin & Peters, 2018) have been conducted on consumer perceptions with additional determinants to identify the purchasing pattern of environmental sustainable apparels but very limited research has been published on the developing countries context (Albloushy & Hiller Connell, 2019). The existing literatures mainly focus on the cases of societies in developed countries including the United States and the United Kingdom (Chang & Watchravesringkan, 2018; Vlastelica & Kosti, 2023). Only limited studies have been conducted in Ethiopia. Moreover, studies related to the investigating of the actual buying behavior of the consumer and consumers' over-consumption are scarce (White et al., 2017).

The study bridges this gap by exploring the consumer’s environmentally sustainable apparel purchasing intention by using the extended theory of planned behavior (TPB) model. The study also contributes to enhancing the explanatory power of the TPB in ESA product consumption by incorporating relevant variables. The structural equation model, supported by SPSS, was applied to assess the empirical strength of the relationship of the factors in the proposed hypotheses. The present study will help to develop the basic knowledge and awareness among consumers towards environmentally sustainable conscious lifestyles. However, the concepts and variables under investigation will also help to design the marketing policies for those wishing to enter into the Ethiopian marketplace with ESA’s.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Review

According to Lake (2009), consumer behavior represents the study of individuals and the activities that take place to satisfy their realized needs. Different determinants are used to predict the purchasing behavior of consumers (Minbale et al., 2024). In this manner, scholars adopt different theories as a models to express the intention-behavior relation and to look into the causes of such behavioral intentions. This study adopts a theory of planned behavior to design a theoretical framework and extend it by adding a relevant variable.

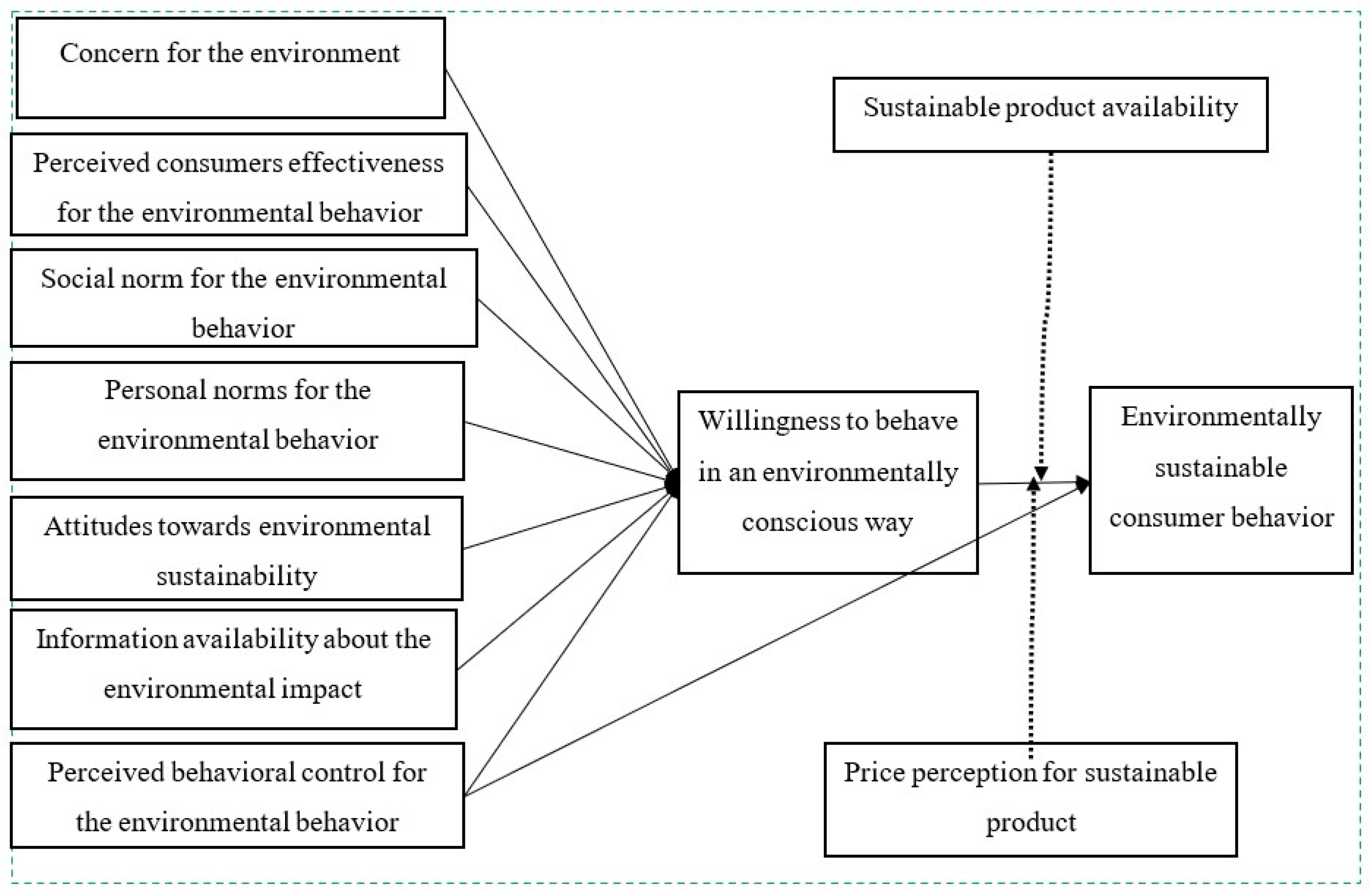

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been applied to examine consumer apparel purchasing behavior in several studies (Minbale et al., 2024). The TPB model is effective in predicting consumers’ apparel purchase intention and behavior. TPB is a theory designed to forecast a person's behavior formulated at a very general level and applies to any behavior of interest to social and behavioral scientists (Ajzen, 2020). The TPB model states that behavioral intentions are determined by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control (Ajzen, 1991, 2002, 2020). Further in this study, the theory is extended by adding variables (Concern for the environment, Perceived consumer effectiveness, Information availability) and the mediating variables, Sustainable product availability, and Price perception for sustainable products. The model is extended for better prediction of intention, which in consequence leads to actual behavior.

As environmentally sustainable apparel is a unit study of this research, we added relevant variables to the model to achieve the objective and to increase the accuracy of the model in predicting consumer behavior. A product that has little to no impact on the environment during manufacturing, use, or disposal is regarded as an environmentally friendly product and a consumer who consumes a green product is called an environmentally conscious consumer (Islam & Khan, 2014). Sustainable consumption behavior refers to “the pattern of reduced consumption of natural resources, changing lifestyle and consumption of environment-friendly products (P. Wang et al., 2014). It covers a wide range of issues like meeting the needs of the consumers sustainably, enhancing resource efficiency, improving the quality of life, and minimizing waste (Fedrigo & Hontelez, 2010; P. Wang et al., 2014). So, based on the literature, relevant variables are added to the model for better prediction. Based on the theoretical review the model was prolonged by adding relevant variables called Concern for the environment, Perceived consumer effectiveness, Information availability and the mediating variables, Sustainable product availability, and Price perception for sustainable products and constructing an extended theory of planned behavior model to structure the study framework and the research hypotheses (H).

2.2. Related Work and Hypotheses

2.2.1. Determinants of Intention to Sustainable Consumption

2.2.1.1. Environmental Concern

Environmental concern is an individual's extent of concern and emotional attachment toward environmental issues, environmental threats, and environmental protection (Apaolaza et al., 2022; Rausch & Kopplin, 2021a). It is the individual's sense of responsibility and involvement regarding environmental protection (Kim & Choi, 2005; Roberts & Bacon, 1997). Studies have shown that environmental concern has a positive contribution to the purchase of eco-friendly apparel (Alam & Abunar, 2023; Demirbaş, 2016; Gallo et al., 2023; Ghaffar & Islam, 2023; Rumaningsih et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2023). However, according to (Hasbullah et al., 2022), environmental concerns have a diminishing effect on consumers purchasing decisions. Additionally, the level of personal involvement and psychographics can also impact consumers' pro-environmental purchasing activities, with socio-demographic variables like gender, age, education, profession, and the like. Overall, a strong concern for the environment can lead to more sustainable consumer choices and behaviors. Based on the above, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H1: Environmental Concern has a positive and strong impact on environmentally responsible willingness to behave.

2.2.1.2. Attitude (ATT) towards Environmental Sustainability

Attitude is defined as a psychological path that an individual can consistently favor or disfavor to a specific object (Eagly, 2007), and how they habitually evaluate a given scenario's potential costs and benefits (Lavuri, 2023). Attitude plays a critical role in forming consumer purchase intention (Khare, 2019; Paul et al., 2016). Many previous researchers found that attitude is an essential variable while predicting consumers’ purchase intention (Lavuri, 2023; Zhang et al., 2019), and one of the strongest predictors of environmentally sustainable purchasing intention and behavior (Khare, 2019; Nayak et al., 2019; Polonsky et al., 2012; Taufique et al., 2017). In the specific context of green apparel, environmental attitude has also been found to have a significant positive association with intentions to purchase green apparel (Hong et al., 2017; Jacobs, 2018; Lavuri, 2023; Nayak et al., 2019; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). Consumer attitude significantly affects the consumer's tendency to buy sustainable apparel (Rausch & Kopplin, 2021b), and their willingness to spend money on green products (Kaur et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019). The attitude was found a positive antecedent for sustainable purchasing intention but does not have a positive effect on sustainable purchasing behavior (Ceylan, 2019). Therefore, we theorize the following hypothesis

H2. Environmental attitude has a positive association with consumer’s environmentally sustainable apparel purchasing intention.

2.2.1.3. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness

`Perceived consumer effectiveness is a “domain-specific belief that the efforts of an individual can make a difference in the solution to a problem” (Ellen et al., 1991; Rizkalla, 2018). Studies (Chi et al., 2021; Kim & Oh, 2020; Kovacs & Keresztes, 2022; T. Lin et al., 2022; J. Wang & Hsu, 2019) have shown that perceived consumer effectiveness significantly impacts consumers' intentions to purchase sustainable clothing. The highly perceived consumer effectiveness group shows a consistent attitude-purchase intention relationship ( Kumar and, Singh 2022; L. Hannah et al., 2021). Overall, perceived consumer effectiveness emerges as a key determinant shaping individuals' intentions to engage in sustainable consumption practices. Meanwhile, other studies found that the effect of PCE on behavior was mediated by attitudes (Kim & Choi, 2005). Therefore:

H3: Perceived consumer effectiveness has a positive influence on environmentally responsible willingness to behave.

2.2.1.4. Subjective Norms

Subjective norm (SN) is defined as the perceived social pressure on an individual to do or not to do a specific behavior (Ajzen, 1991, 2020; Zhang et al., 2019), social influence on a particular behavior (Kim et al., 2010). Personal norms and social norms play crucial roles in influencing sustainable apparel purchasing intentions. Research indicates that personal norms, positively affect consumers' sustainable apparel purchasing intention (Hassan et al., 2022; Lavuri et al., 2023; C. Lin et al., 2023; P. Nguyen et al., 2022; Tandon et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2022). However, according to (Olbrich et al., 2011) Personal norms of sustainability have no significant impact on willingness to behave. Additionally, social norms, shaped by cultural influences and social learning, significantly affect consumption patterns and sustainability choices within a society (Boson et al., 2023; P. M. Nguyen et al., 2022). Social norms positively affect consumers' sustainable apparel purchasing intention (Hassan et al., 2022; Lavuri, 2022; Lavuri et al., 2023; Niu et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2022). But other studies found that social norm has an insignificant effect on consumers purchasing intention (Varshneya et al., 2017; Okur and Saricam, 2019; Tabas, 2023). Also, other studies found that social norm has negative (Canova et al., 2022) and indirect effect (Carfora et al., 2022) on sustainable purchasing intention. Studies emphasize that when individuals perceive a strong alignment between their personal values and social expectations regarding sustainable consumption, they are more likely to purchase green apparel, highlighting the interconnectedness of personal and social norms in driving sustainable purchasing behaviors. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed:

H4: Social norms have a positive and significant influence on environmentally responsible willingness to behave.

H5: Personal norms have a positive and significant influence on environmentally responsible willingness to behave.

2.2.1.5. Availability of Information

The availability of information plays a crucial role in influencing consumers' sustainable purchasing behavior (Debnath et al., 2023; Fischer et al., 2021; Fu et al., 2023; Saeed et al., 2019). Information can be defined as those given to consumers through different sources about the product’s and company's environmental impact/actions throughout the life-cycle of a product. Information availability influences consumers' sustainable purchasing intention and behavior (Azzahro et al., 2022; Caferra et al., 2023; Kasim, 2022; O’Rourke & Ringer, 2016). Consumers lack a holistic understanding of sustainability due to limited information (Bui et al., 2022; Weniger et al., 2023). Consumers make trade-offs based on available information on clothing attributes (Blas et al., 2022), show a higher willingness to pay with sustainability information (Hwang et al., 2021), and consumers prioritize product and service quality over information availability (Gallo et al., 2023; Maciaszczyk et al., 2022). Although recognized as one of the common obstacles to more responsible behavior, information is rarely included in ethical research with some exceptions in the fair trade context research (Irene & Gil-saura, 2020; Rizkalla, 2018). In line with the above:

H6: Information availability has a positive influence on environmentally responsible consumer behavior.

2.2.1.6. Ethical Obligation

Ethical obligation plays a significant role in influencing sustainable purchasing intentions among consumers. Studies have shown that ethical obligation positively impacts consumers' purchase intentions toward sustainable products (Chen, 2020; Floriano & de Matos, 2022; R. Kumar et al., 2023; Madar et al., 2013). Furthermore, ethical obligation has a significant influence on brand image, customer engagement, and sustainable purchase intentions (Anwar et al., 2019; Berki-Kiss D., 2022; Hussain and Dar, 2021). Understanding and promoting ethical obligation can thus be a crucial aspect of encouraging sustainable consumption behaviors and driving positive environmental impacts. Align with this the following hypothesis is extracted:

H7: A consumer’s ethical obligation towards sustainability has a positive and significant effect on a consumer’s sustainable purchasing intention.

2.2.1.7. Perceived Behavior Control (PBC)

PBC measures an individual’s perception of how simple or challenging it is to perform a behavior (Ajzen, 2020). Research indicates that PBC has a direct impact on green attitudes (M. Hasan, 2022; T. Nguyen, 2023). PBC is the strongest predictor followed by attitude and subjective norms (Anastasia & Santoso, 2020; çivgin & kizanlikli, 2022; M. Hasan, 2022). Studies also found no positive impact of Perceived Behavior Control (Astika Nithasyah et al., 2023; Lavuri et al., 2023). In addition, PBC control has a small influence on purchase intention (Gonçalves et al., 2022). Perceived behavioral control also differs from actual control, although when a person has the right opportunities and resources (time, money, skills, and information), it can also be used as a substitute for actual control (Chang & Watchravesringkan, 2018). Therefore, the following hypothesis was established:

H8 : Perceived behavioral control will positively influence consumers’ willingness to behave.

H9 : Perceived behavioral control will positively influence consumers’ actual sustainable apparel consumption.

2.2.2. Mediating Variables

2.2.2.1. Product Availability

The availability of sustainable products significantly influences consumers' sustainable purchasing behavior. Mummeries research indicates that the lack of product availability is a major factor hindering consumers from purchasing sustainable products (Gierszewska & Seretny, 2019; Pinkse & Bohnsack, 2021; Weniger et al., 2023). In addition product availability influences sustainable product purchase intention (Kaczorowska et al., 2019; Kasim, 2022; Maciaszczyk et al., 2022; Misron et al., 2023; Sargın and Dursun, 2023; Setyawan et al., 2018; Stoll et al., 2019; Tang & Bhamra, 2009; Weniger et al., 2023; Yi, 2019). Lack of availability hinders consumers from purchasing sustainable products (Arul et al., 2021). But according to (Tomkins et al., 2018; Orzan et al., 2018) consumers are not influenced by the availability of the product instead they are influenced by package information. Also, there is limited empirical research on this relationship exists (Arul et al., 2021). In line with the above discussion, the following hypotheses are suggested.

H10: Sustainable product availability has a significant mediating role on consumers’ sustainable purchasing intention and behavior.

2.2.2.2. Price Perception

The relationship between price perception for sustainable products and consumers' sustainable purchasing behavior is a crucial aspect influenced by various factors. Studies have shown that price perceptions directly affect consumer attitudes and buying interest (Sutanto & Wulandari, 2023), while affordable prices play a significant role in driving sustainability behavior. Price perception significantly influences sustainable purchasing behavior (Anquez et al., 2022; Gallo et al., 2023; Ghaffar & Islam, 2023; Kovacs & Keresztes, 2022; Misron et al., 2023; H. Park & Lin, 2018). In some cases, consumers may be unwilling to pay for sustainable products (Gallo et al., 2023). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H11: Consumer’s price perception towards a sustainable apparel product has a significant mediating effect on consumer’s sustainable purchasing intention and behavior.

2.2.3. Sustainable Consumption Willingness to Behave and Purchasing Behavior

A consumer purchasing intention refers to the consumer’s tendency, degree of willingness to act and consume by sacrifices to pay, and a situation where a consumer tends to buy a certain product in a certain condition (Mirabi et al., 2015; Raza et al., 2021; Ringle et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019). Purchase intention is a kind of decision-making that studies the reason to buy a particular brand by the consumer (Shah et al., 2012; A. Hasan, 2024)). This essentially is a signal of consumer purchasing behavior (Raza et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019). Prior studies showed that when consumers are aware of the significance of environmentally sustainable apparel products they will become more likely to incorporate and tolerate sustainability issues in their purchase decision-making (Chang & Watchravesringkan, 2018; Chi et al., 2021; Durrani et al., 2023; C. A. Lin et al., 2023; T. H. Nguyen, 2023). Therefore, we posit the following.

H12: Consumer’s environmentally sustainable apparel product purchasing intention has a significant and positive effect on consumer’s sustainable purchasing behavior.

2.3. Conceptual Frame Work of the Study

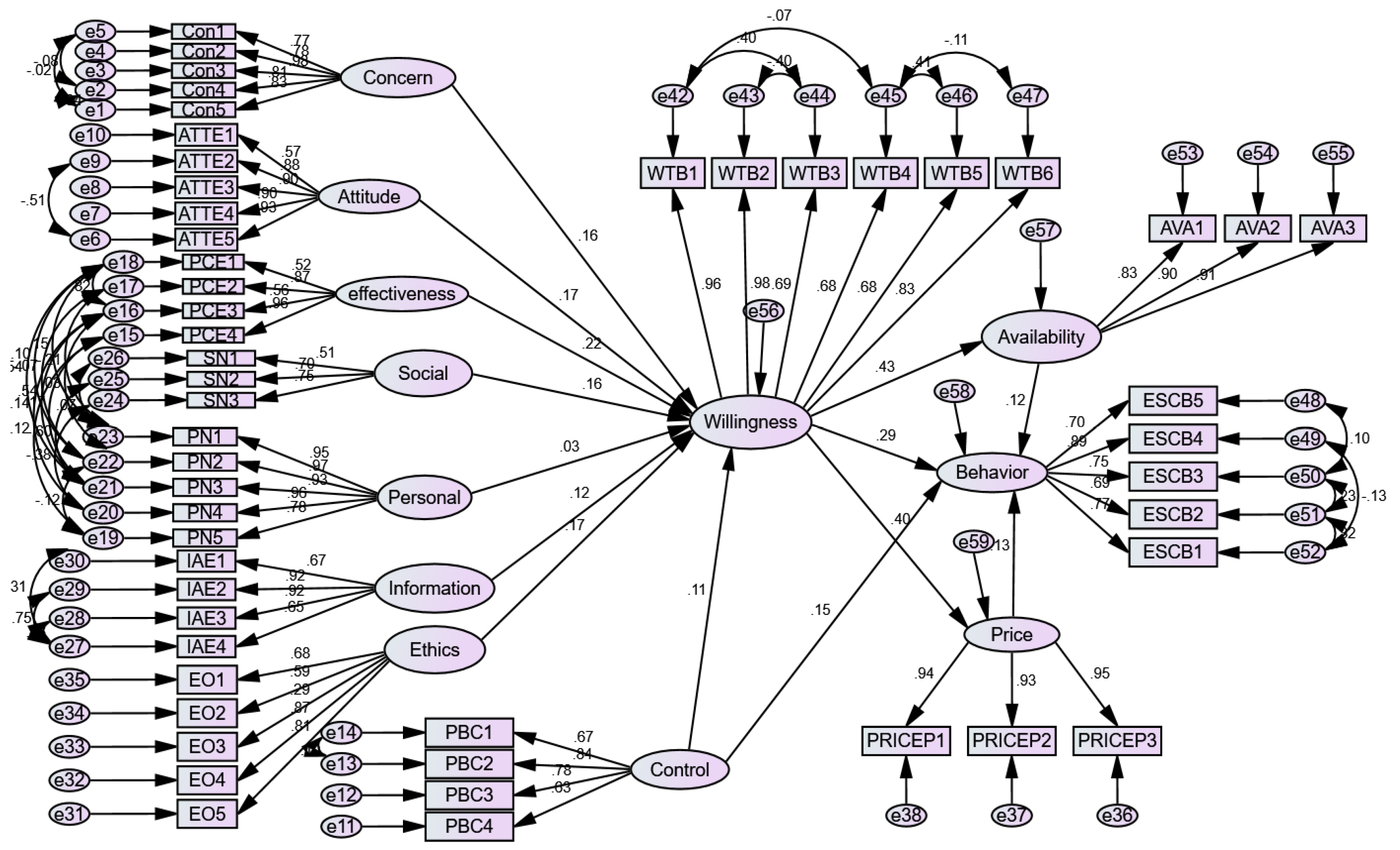

In line with observations, the environmental dimension of behavior was investigated by using different antecedents of responsible behavior. When explaining the process of responsible consumer behavior, the theory of planned behavior is most commonly used (Rizkalla, 2018). And for the sake of increasing the accuracy of predicating the actual consumption behavior of a consumer, a model was extended by adding relevant variables see

Figure 1 below. In this study, the consumers' intention was substituted by willingness, as suggested by (Abdul-Muhmin, 2007) because the availability of environmental facilities and sustainable product alternatives is lower. So, the studied variables in the model were developed from the review of previous studies, and then we developed and revised them based on the qualitative research results to suit the context of sustainable consumption.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This research is a descriptive, explanatory, and crossectional survey type, and adopts both qualitative and quantitative approaches. A theory of planned behavior has been used to construct a theorthicalframe work of a study. The study used both first-hand and second-hand data sources. The source of the data of this study was Ethiopian apparel consumers who lived in Addis Ababa, Bahir Dar, and Adama City.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

To check the measuring items' completeness, language, clarity, structure, and appropriateness a pilot test was conducted using 60 respondents. The main data were collected from Addis Ababa, Bahir Dar, and Adama city by following a convenience sampling technique through physically distributed questionnaires. For the data collection, the most populated retail areas of each city were identified. The data was filled in by those willing customers walking to the selected clothing retail places during working hours. The data were collected in three months from February to April 2024. A total of 578 questionnaires were distributed to respondents, with 523 complete and usable responses received accounting for a 90.5 percent response rate.

3.3. Sample Size Determination

As the population of a study site is too large, an unknown population sample formula is recommended to determine the sample size of a study. In using the formula 95% confidence level, 0.5 standard deviation, and confidence interval of +/- 5% are used. From the standard table Z- score of 95% confidence level is 1.96. The formulation is as follows:

SS= (Z-score) 2 * StdDev*(1-StdDev) / (margin of error) 2 (Eng, 2003; Lenth, 2001)

Where SS stands for Sample size

The author uses this formula to determine the sample size.

SS= (Z-score) 2 * StdDev*(1-StdDev) / (margin of error) 2

SS = (1.96) ² * 0.5*(1-0.5) / (0.05) ²

SS = 3.8416 * 0.25 / 0.0025

SS = 384.16 ~ 385

In a survey study, many factors will happen such as missing data, non-response, unable to contact the respondents, missing during collection, and others, so to compensate for such factors the researcher will add a 10 - 50% allowance to the calculated sample size as suggested by (Dell et al., 2002; Lenth, 2001). Therefore, for this study, 50% were added, and 50% of 385 respondents became 193. Totally 578 respondents were needed. |

Therefore this study surveyed 578 consumers. A sample was selected based on the consumers’ willingness to participate in the survey. Each participant was instructed about the study, and their doubts were also cleared by the data collectors and researcher.

3.4. Data Collection Instruments

Measurement items of constructs were collected from different literature. Construct and measurement items that are most frequently used and tested by different literature are selected as a variable and metrics for this study. A study adopted a theory of planned behavior model as a framework and extended it by adding relevant variables for the sake of increasing the accuracy of the prediction of a model. To collect data a systematic questionnaire was utilized by using a 7-point Likert scale (strongly agree = 7, strongly disagree = 1). There were three sections in the questionnaire. The sources of the selected constructs are summarized in

Table 1. In the last section, the participants were asked to list any other variables that they considered while purchasing clothing.

3.5. Data Analysis

To assess the reliability of measurement items a Cronbach's alpha was used, and a result of 0.927 was obtained, which is greater than the threshold of 0.7 (B. Byrne, 2013; Hair et al., 2021). To check the validity of a construct questionnaire's Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and the Bartlett test of sphericity were used. The overall scale's KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.75, which was higher than the suggested value of 0.60. (Williams et al., 2010). The sphericity test by Bartlett was found to be significant [ = 1164.40, df = 66, and p =.000] (Tobias & Carlson, 1969).

Before a statistical test was applied to the collected data, missing data, normality, and multi-collinearity tests were conducted. The missing value in this study ranges from 0.1% to 0.3% per item, indicating that the values are within the threshold range (Edeh et al., 2023; Hair et al., 2021). So, missing values were replaced using the estimated mean through SPSS. The skewness and kurtosis were also found at the normal range (all values were within limits ±1 and ± 3) (Kline, 2015). The tolerance range values were between .62 and .97 and the variance inflation factor (VIF) ranges from 1.03 and 1.62, thus, are in the acceptable range (B. Byrne, 2011; Kline, 2015). The result showed that none of the independent variables is highly correlated with any other exogenous variable. So, there is no problem of high correlation among the variables.

Maximum likelihood estimation methodology was selected as the most suitable way for conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This study also used covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM). CB-SEM is better for factor-based models and provides better model fit indices (Dash & Paul, 2021). The model fit was assessed in this study using the comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the χ2 values. Furthermore, paired sample t-tests were used to compare the mean score differences between the variables of a respondent.

4. Result

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 2 outlines the respondent’s descriptive statistics and characteristics. Among the respondents, males account for 51.1 %, whereas female respondents comprise 48.9% of the sample size. Regarding age, the highest number of respondents falls within the age range of 25-34 which is around 44.4% of the sample size. Concerning the educational qualifications level of the respondents, a large proportion of the research participants (73%) have completed their university degrees. The majority of the respondents (58.1%) are first-degree holders. The respondent’s monthly income level is also another aspect that has been investigated as part of the questionnaire. The majority of the respondents fall in Upper-middle level the monthly income which accounts for 35.2%. Regarding the marital status of the respondents, 57.7% are unmarried, 40% of respondents are married, and the rest 2.5% are divorced.

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

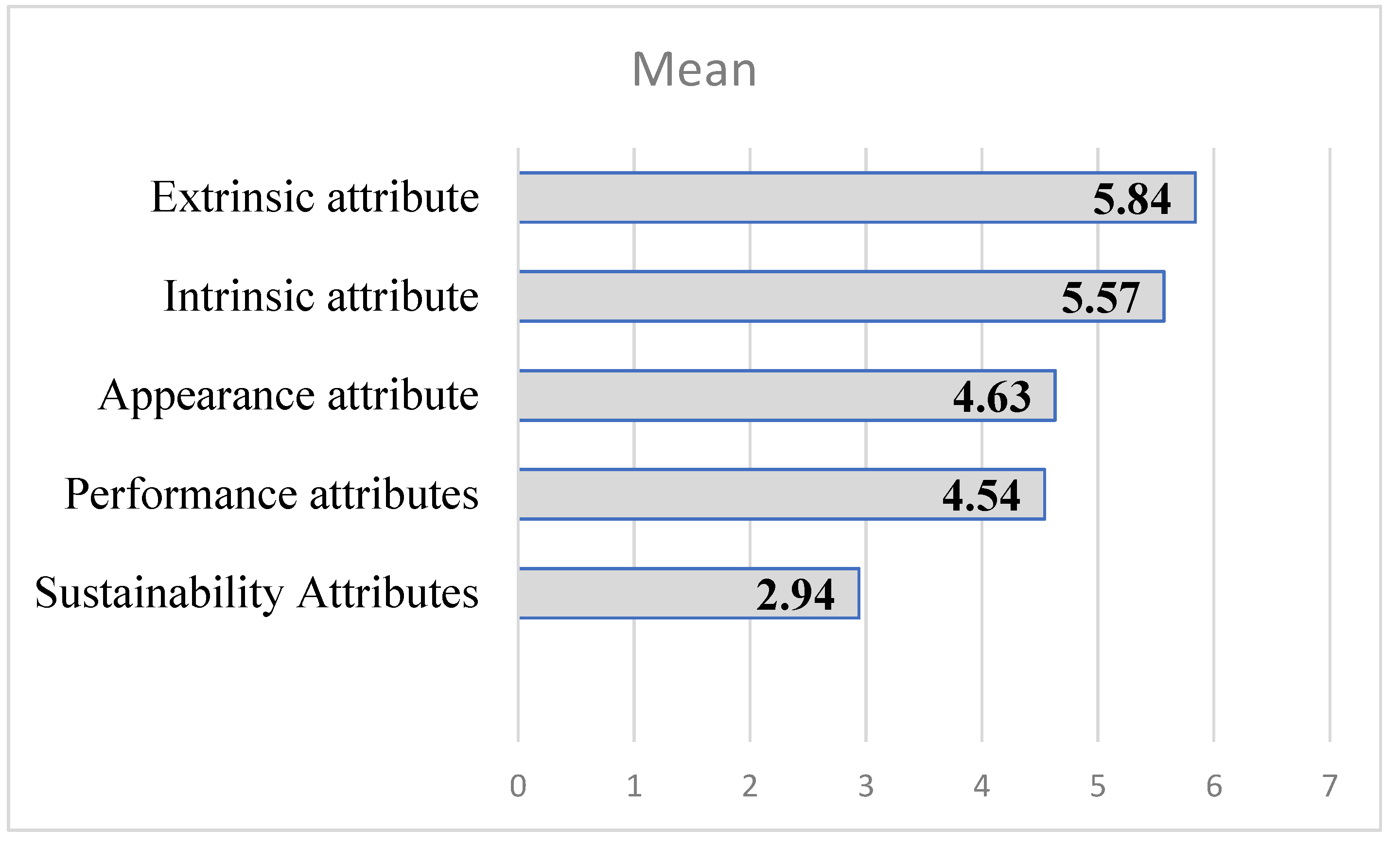

To know whether Ethiopian consumers consider the sustainability attribute while purchasing apparel, the respondents were requested to rate the importance level of the product attribute. The result is presented in

Figure 2. As the mean values indicate, Ethiopian consumers, use Extrinsic attributes [Brand of a product, Price, made-in label, approvals of others, and a like] (Mean = 5.84) as the most important attribute and there is low consideration of sustainability attributes according to a 7-point Likert scale mean scale (Ahmad & Amin, 2012).

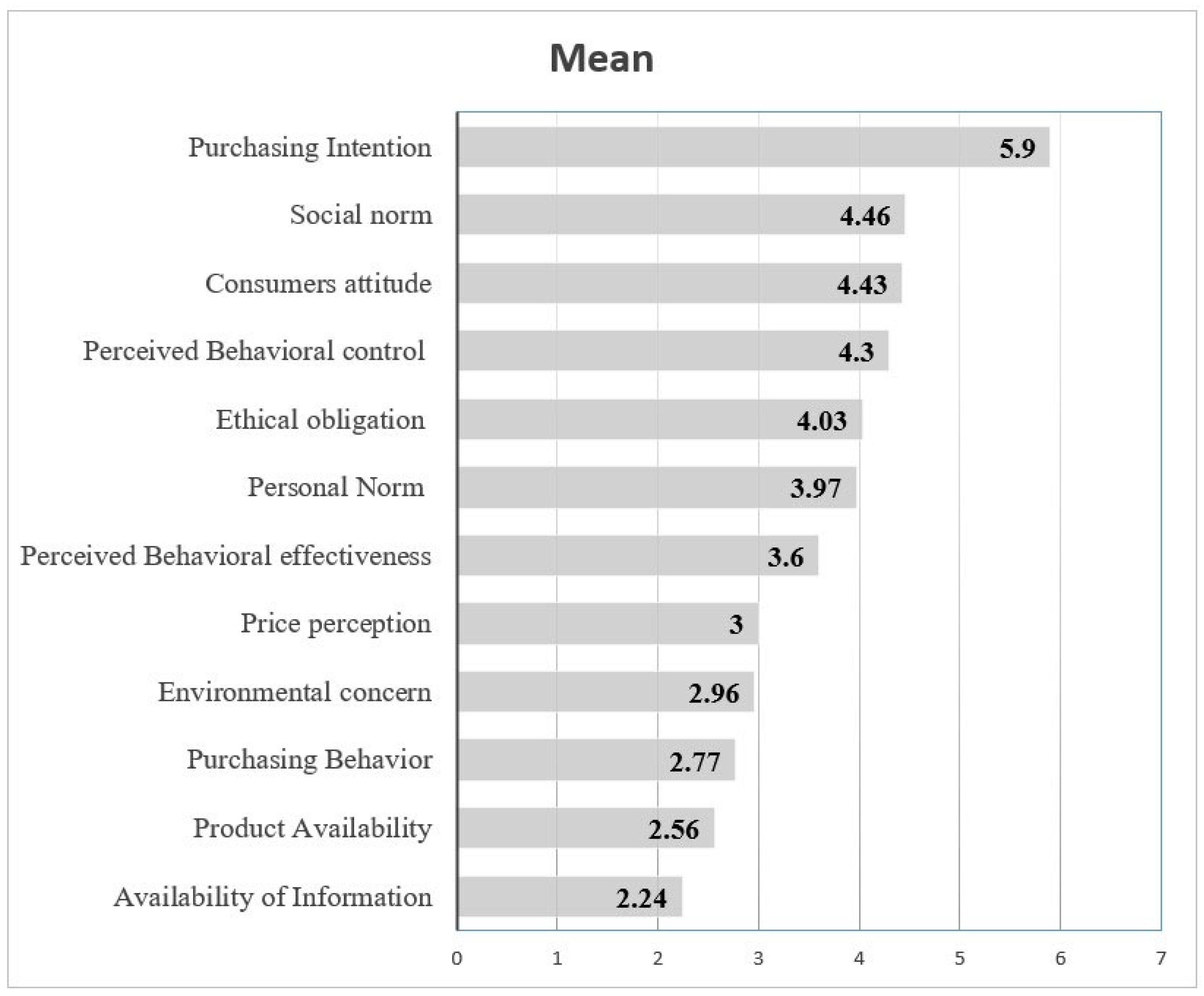

In addition, to investigate Ethiopian consumer’s environmental concerns and awareness levels, a comparison mean was conducted for each studied variable. According to (Ahmad & Amin, 2012) mean score results ranging from 1.0 - 2.19 is Very low, (2.20 - 3.39) is Low, (3.40 - 4.59) is Moderate, (4.60 - 5.79) is High and (5.80 - 7.0) is Very High. As seen in

Figure 3 the consumers' environmental concern (M=2.96), availability of information about sustainability (M=2.24), Price perception (M=3.00), sustainable Product Availability (M=2.56), and consumers' environmental sustainable apparel product purchasing behavior (M=2.77) are rated a low level see

Figure 3. The mean score of Consumer attitude, Perceived Behavioral Control, Perceived Behavioral effectiveness, Social norm, Personal Norm, and Ethical obligation are rated at a moderate level. The consumers' purchasing intention towards environmentally sustainable apparel is rated at a high level.

4.3. Model Validations and Verifications

The validity and reliability of each item were evaluated in separate confirmatory factor models before assessing a research model. According to Byrne, (2013), CFA can be used to determine whether the sample data is compatible with the hypothesized model of the study or not.

4.3.1. Final CFA Model Measurement Scale

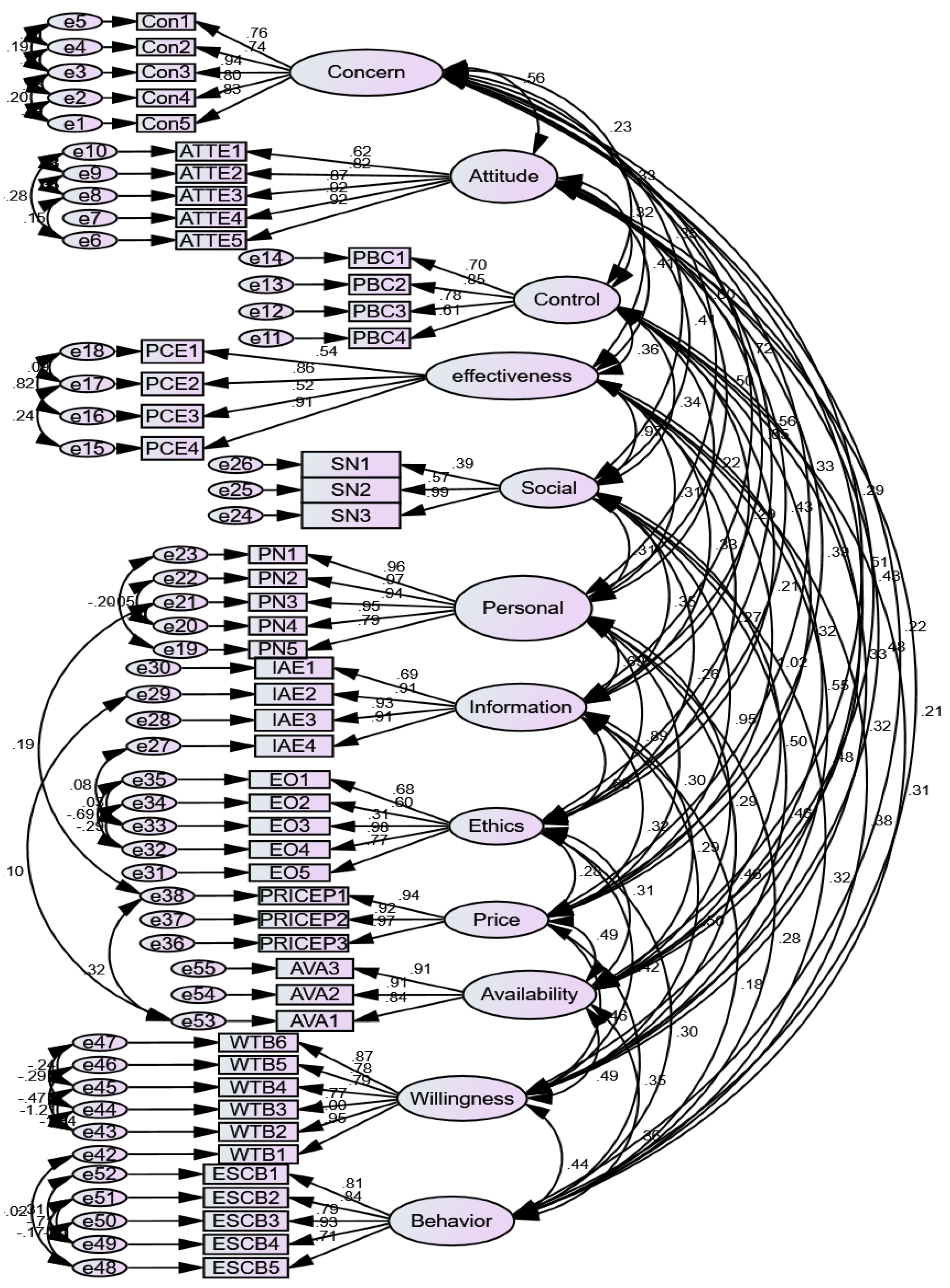

The convergent validity of the measurement model can be assessed by the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Composite Reliability (CR) (Alarcón et al., 2015). A summary of the model is presented in

Table 3.

According to the obtained AVE values see

Table 3 above, all values exceeded 0.50 (cut-off value) with p = 0.001, indicating that discriminant validity was supported for all constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The composite reliability (CR) measures exceeded the suggested level of 0.6 which suggests high reliability of the scales (Hair et al., 2021; Rožman et al., 2020). All the loadings were significant. On the other hand, all the factors recorded a CR of above 0.6. These results indicate that the CFA path model had achieved convergent validity see

Table 3.

Figure 4.

CFA Path Analysis.

Figure 4.

CFA Path Analysis.

Discriminant validity is proven when a latent variable explains more variance in the indicator variables that it is linked to than it does with other constructs in the same model (B. Byrne, 2011; Henseler et al., 2015). According to (Hair Jr et al., 2010), for discriminant validity, the value of the correlation must be lower when compared to AVE^2 for all the constructs. In the testing of the CFA model, and as indicated in

Table 3 above, all factor correlation values were lower than the AVE^2 thus achieving the required thresholds for discriminant validity.

4.3.1.1. Structural Model Analysis (SEM)

Finally, a research model was tested by using CB-SEM. AMOS version 26 was used to estimate the parameters and assess the fit of the model. A summary of goodness fit indices for the measurement model showed that all values were acceptable presented in

Table 4, whereas the results of factor analysis, convergent validity, and the overall values for AVE, CR, and DV all were acceptable see

Table 4 and

Figure 5.

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

The p-value was used to assess the significance of the relationship between the independent variable with the dependent one. From the model estimates, all variables had a positive and significant effect on the dependent variables at p<0.05, which means all hypotheses are supported except the hypothesized path of personal norms with an environmentally responsible willingness to behave. The results of SEM analysis are presented in

Table 5 below.

4.5. Content Analysis to Open-Ended Questions

In addition, respondents were provided with open-ended questions about environmentally sustainable apparel products. From the respondent’s responses to the open-ended question, we can conclude that Ethiopian consumers are unaware of environmentally sustainable apparel, even the impacts of the life cycle of the apparel product on the environment. They mentioned the lack of information about sustainability, lack of availability of sustainable products, lack of promotion, and price sensitivities of Ethiopian consumers as a drawback.

4.6. Discussions and Implications of the Study

4.6.1. Determinants of Sustainable Consumption Willingness to Behave

Marketing and consumption of apparel products result in negative environmental impacts due to the massive production volume of clothing items. In this regard, the study anticipates the antecedents of a consumer’s willingness to behave in environmentally responsible apparel products. Consumers’ willingness to behave means the consumers' tendency to favor a product and is a crucial tool to predict purchasing behavior. Different determinants of consumers’ willingness to behave were investigated.

4.6.1.1. Environmental Concern with Consumers’ Willingness to Behave

Consumers' concern towards the environment means an individual's extent level of concern and emotional attachment toward environmental issues. The β std regression coefficient for the consumers' concern towards the environment → consumers’ Willingness to behave in an environmentally conscious way is 0.16 at a significance level of 0.05, which indicates a positive and significant linkage between environmental concern and consumers’ willingness to behave and hypotheses one (H1) is supported. This is in line with other studies (Demirbaş, 2016; Gallo et al., 2023; Ghaffar & Islam, 2023; Zeng et al., 2023). This is due to Ethiopian consumers' positive emotional attachment to the environment. And that’s why millions of Ethiopians participate in planting a tree per year. However other studies find that this environmental concern has a mediating effect on purchasing intention (Hasbullah et al., 2022).

4.6.1.2. Consumer Attitude with Consumers’ Willingness to Behave

The β std regression coefficient for Consumer Attitude → consumers’ Willingness to behave in an environmentally conscious way is 0.17 at a significance level of 0.02, which indicates a positive and significant linkage between Consumer Attitude and consumers’ willingness to behave and hypotheses two (H2) is supported. The result is somehow similar (Nayak et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2017; Jacobs, 2018; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). Attitude not only has a positive and significant effect on purchasing intention but also affects their level of eco-consciousness (Lavuri, 2022; Rusyani et al., 2021), their propensity to buy sustainable apparel (Rausch & Kopplin, 2021b), and their willingness to spend money on green products (Kaur et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019). In another way (Ceylan, 2019) found that attitude has a positive effect on sustainable purchasing intention but does not have a positive effect on sustainable purchasing behavior (Ceylan, 2019).

4.6.1.3. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness with Consumers’ Willingness to Behave

The β std regression coefficient for Perceived consumer effectiveness → consumers’ Willingness to behave in an environmentally conscious way is 0.22 at a significance level of 0.01, which indicates a positive and significant linkage between Perceived consumer effectiveness and consumers’ willingness to behave in environmentally responsible apparel product and H3 is supported. The result is in sync with (Chi et al., 2021; Kim & Oh, 2020; Kovacs & Keresztes, 2022; T. Lin et al., 2022; J. Wang & Hsu, 2019).

4.6.1.4. Subjective Norm with Consumers’ Willingness to Behave

The β std regression coefficient for Personal norm and social norm → environmentally responsible willingness to behave is 0.03, and 0.16 at a significance level of .714, and .022, which indicates that a personal norm has an insignificant effect with environmentally responsible willingness to behave, sync with (Olbrich et al., 2011), it is because of that Ethiopian consumers mainly consider price as an important attribute to their purchasing decision (Minbale et al., 2024). Social norm was found as a positive and significant predictor of consumers’ willingness to behave with environmentally responsible apparel products, sync with (Hassan et al., 2022; Lavuri, 2022; Niu et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2022). In this scenario H4 is unsupported and H5 is supported.

4.6.1.5. Availability of Information with Consumers’ Willingness to Behave

The β std regression coefficient for the availability of information → environmentally responsible willingness to behave is 0.12, at a significance level of .05, which indicates a positive and significant effect on environmentally responsible willingness to behave, sync with (Saeed et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2023; Siraj et al., 2022). However, the quality of available information highly affects the purchasing intention. So, H6 is supported. As we seen the mean value of the availability of information is 2.24, which means the availability of information is too low in the Ethiopian scenario.

4.6.1.6. Ethical Obligation with Consumers’ Willingness to Behave

The β std regression coefficient for Ethical obligation → environmentally responsible willingness to behave is 0.17, at a significance level of .05, which indicates a positive and significant effect on environmentally responsible willingness to behave, sync with (Chen, 2020; Floriano & de Matos, 2022; R. Kumar et al., 2023). And H7 is supported.

4.6.1.7. Perceived Behavior Control with Consumers’ Willingness to Behave

The β std regression coefficient for PBC → environmentally responsible willingness to behave is 0.11 at a significance level of 0.01. This would indicate a positive and significant path between PBC and environmentally responsible willingness to behave and support H8. This is in line with (M. Hasan, 2022; T. Nguyen, 2023). The study also found that perceived consumer effectiveness is the most influential predicator of Ethiopian consumers’ environmentally responsible willingness to behave followed by attitude and ethical obligation, environmental concern and social norms, availability of information, perceived behavioral control, and personal norms respectively. Personal norm is found as insignificant predicators.

4.6.2. The Mediating Effects of Product Availability and Price Perception

This study uses sustainable product availability and consumers' Price perception towards sustainable apparel products as mediating variables. The SEM result also showed that both product availability and price perception significantly and positively affect the sustainable purchasing intention and behavior of consumers. The total effects, direct effects, and indirect effects are 4.38, .315, and .125 respectively at a p-value of .001. This indicates the mediating effects of price perception and product availability on purchasing intention and behavior are significant and positive. Hence, H10 and H11 are supported.

4.6.3. Determinants of Sustainable Consumption Behavior

This study uses consumers’ willingness to behave and perceived behavioral control as a direct predictor of sustainable consumption behavior. The β std regression coefficient for the path perceived behavioral, and environmentally responsible willingness to behave → sustainable consumption behavior are .15, and .29 respectively at a significance level of .01, which indicates a positive and significant effect on sustainable consumption behavior, and H9 and H12 are supported. The finding is in sync with (Koszewska, 2016). From the determinate factors of sustainable consumption behavior, the outcome of the research indicated that the consumers’ willingness to behave environmentally responsible apparel products has the highest impact on sustainable consumption behavior. The result sync with (Rausch & Kopplin, 2021). PBC was found as a lower effect on the prediction of consumers' sustainable consumption behavior, agreed with other studies (Giantari et.al, 2013; Valaei et.al, 2017).

Promoting sustainable consumption is a crucial aspect of sustainable development (Sesini & Castiglioni, 2020), and a critical force that leads to sustainable production (Borovskikh & Albareda, 2020). Money consumers have a positive attitude toward sustainable products; but their attitude did not change in purchasing (Khare, 2019. In recent decades, the consumer's consumption habits have changed rapidly (Testa et al., 2020). Now sustainability attributes play a significant effect on consumers' purchasing decisions (Testa et al., 2020). Improving sustainable behavior in the context of apparel consumption demands changing consumers’ mindsets away from overconsumption of fashion-trend-related clothes to investing in ecologically produced clothes and items that aim to last longer. However, consumers’ knowledge and attitudes do not always translate into actual behavior due to different internal and external barriers to those behaviors. Therefore, to better understand clothing consumption behavior—and, thus, to identify methods to promote behavioral modifications—it is necessary to identify how and why consumers engage in a particular behavior and which factors influence that (Vlastelica & Kosti, 2023).

5. Conclusions

Inline with the above discussion, it can be conclude that there is low level of awereness about the impact of clothing consumpstion and disposal to the environment by Ethiopian consumers. In addition the considertation of sustainability attributes while making a purchasing decision is low. The sustainability attributes were found the least important factor for Ethiopian consumers purchasing decisions with a mean value of 2.94. According to the (Ahmad & Amin, 2012) mean score scale, the importance level of the sustainability attribute for Ethiopian consumers is low and insignificant. The study found that consumer willingness to purchase sustainable apparel is significantly influenced by environmental concern, perceived consumer effectiveness, social norms, ethical obligation, perceived behavioral control, and information availability, but the personal norms were found insignificant at the p-value of <0.05. Perceived behavioral effectiveness was found the most significant effect at a magnitude of .22. The extended TPB model successfully incorporates these additional variables, highlighting that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are crucial in predicting sustainable purchasing behaviors. Moreover sustainable consumption behavior is significantly influenced by perceived behavioral control, and willingness to behave at p vale of 0.05, and the consumers’ willingness to behave was found as the most significant effect at a magnitude of .29. Moreover, the availability and affordability of sustainable products play mediating roles in transforming purchase intentions into actual behaviors. The findings suggest that enhancing the supply and affordability of sustainable apparel, along with targeted educational and marketing strategies, can significantly promote sustainable consumption among Ethiopian consumers. This research provides valuable insights for policymakers and businesses aiming to foster sustainable practices in the apparel industry.

5.1. Managerial and Practical Implications

Research on sustainable consumption behavior has important implications for policymakers, businesses, and individuals, by highlighting the importance of providing accurate information on the environmental impact of products, creating a culture of sustainability, and considering the whole life cycle of products. These findings can help promote sustainable consumption behaviors and reduce negative environmental impacts. Moreover, this research may be used to understand Ethiopian consumers’ sustainable buying behaviors and investigate their intentions regarding purchasing sustainable products. The findings could be helpful to environmentally friendly product manufacturers, marketers, and distributors; they can establish strategies based on the findings by assisting and identifying the levels of buying intention. The results also reveal that extrinsic attributes like price play a vital role in consumers’ ability to purchase sustainable products. The possibility is reduced since the price is higher. As a result, businesses need to develop pricing strategies that consider the financial circumstances of the consumers who fall into this demographic. This study provides the environmentally sustainable apparel manufacturing industry with information that can be used to build marketing strategies that promote awareness among consumers regarding the impact of price and availability on the consumption of green products. These findings provide valuable insights for brand managers, marketers, and policymakers in Ethiopia to develop initiatives that encourage environmentally-conscious apparel purchasing behavior among consumers.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This research makes various theoretical implications to the extant literature in multiple ways. First, this research broadens the past literature by empirically testing and validating the underlying mechanism through environmental concern, perceived consumer effectiveness, ethical obligation, and information availability, influencing sustainable behavior intention toward sustainable consumption. Second, our study examined the sustainable product availability and price perception (PP) for sustainable apparel of moderating the effect between sustainable behavior intention and sustainable consumption and contributing to the past literature on sustainable consumption behavior. Third, this research advances the literature on sustainable consumption behavior in the developing countries context, particularly in the case of Ethiopia. Finally, this study shades a literature gap in developing countries.

5.3. Limitation

The research contains important limitations. First, only selected predictors were included; thus, there is room for future researchers to consider more predictors of purchasing behavior, such as product packaging, government policies, cultural acceptability, personality, lifestyle, religion, and social media influencers. Second, the findings may only apply to the specific population studied and may not represent the larger population or other demographic groups. The study may only examine sustainable consumption patterns in a limited context. The third limitation is that the unit study used a generic apparel product; the results may differ if a specific apparel product is used. Fourth, the study investigated pre-purchasing consumers' apparel evaluation intentions and purchasing behaviors toward environmentally sustainable apparel, leaving room for future researchers to incorporate consumer post-purchasing behavior. Fifth, the majority of the respondents were below 50 years of age, and the elderly and seniors were not captured in the sample.

5.4. Future Research

There is space for the forthcoming researchers to look into the various factors influencing a consumer’s intention to make a green purchase, particularly emphasizing financial, social, and cultural factors’ role in defining consumers’ sustainable consumption behaviors. There is also room for a wider study to investigate pre-purchasing, purchasing, and post-purchasing behaviors in evaluating consumers' sustainable apparel intentions in Ethiopia. More personal, cultural, social, psychological, and marketing factors may also be incorporated as predictors of purchasing behavior to evaluate consumers' sustainable apparel purchasing intentions. In future studies, the age groups may also be expanded to include the elderly and senior citizens to provide more insights and new marketing options for this segment of sustainable apparel consumption.

Note

The terms "environmentally sustainable apparel product" and "green apparel product" are used interchangeably in this study. The terms “willingness to behave” and “purchasing intention” are used interchangeably in this study.

Funding

This research is funded by the Ethiopian Institute of Textile and Fashion Technology (EiTEX, Bahir Dar University.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thankfully acknowledge the EiTEX, Bahir Dar University, and all people who responded to the survey for their time, remarks, and views.

References

- Abdul-Muhmin, A. G. (2007). Explaining consumers’ willingness to be environmentally friendly. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(3), 237–247. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, U. N. U., & Amin, S. M. (2012). The Dimensions of Technostress among Academic Librarians. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65(ICIBSoS), 266–271. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. Journal OfApplied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683.

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior : Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologie, April, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. Z., & Abunar, S. (2023). Appraising the Buyers Approach Towards Sustainable Development with Special Reference to Buying Habits and Knowledge Source of Green Packaging: A Cross-Sectional Study. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development, 19, 400–411. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, D., Sánchez, J. A., & De Olavide, U. (2015). Assessing convergent and discriminant validity in the ADHD-R IV rating scale: User-written commands for Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT). Spanish STATA Meeting, 39.

- Albloushy, H., & Hiller Connell, K. Y. (2019). Purchasing environmentally sustainable apparel: The attitudes and intentions of female Kuwaiti consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(4), 390–401. [CrossRef]

- Amit Kumar, G. (2021). Framing a model for green buying behavior of Indian consumers: From the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 295, 126487. [CrossRef]

- Anastasia, N., & Santoso, S. (2020). Effects of Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioral Control, Perceived Risk, and Perceived Usefulness towards Intention to Use Credit Cards in Surabaya, Indonesia. SHS Web of Conferences, 76, 01032. [CrossRef]

- Anquez, E., Raab, K., Cechella, F. S., & Wagner, R. (2022). Consumers’ Perception of Sustainable Packaging in the Food Industry. Revista Direitos Culturais, 17(41), 251–265. [CrossRef]

- Antil, J. H. (1984). Socially Responsible Consumers: Profile and Implications for Public Policy. Journal of Macromarketing, 4(2), 18–39. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, K., Adi, P. H., & Afif, N. C. (2019). The Effect of Consumer Ethical Beliefs on Green Buying Intention : Social Dilemma as a Mediating Variable. International Conference on Rural Development and Enterpreneurship, 5(1), 252–261.

- Apaolaza, V., Paredes, M. R., Policarpo, M. C., Souza, C. D., & Hartmann, P. (2022). Sustainable clothing : Why conspicuous consumption and greenwashing matter. Business Strategy and The Environment, 2023(23), 3766–3782. [CrossRef]

- Astika Nithasyah, Farhana, Z., & Rahayu, F. (2023). Consequences of Environmental Concern, Health Consciousness, and Perceived Behavior Control. The Management Journal of Binaniaga, 8(1), 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Bick, R., Halsey, E., & Ekenga, C. C. (2018). The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 17(1), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Borovskikh, V., & Albareda, A. L. (2020). SUSTAINABILITY IN FASHION INDUSTRY : STRATEGY AND PRACTICE.

- Borusiak, B., Szymkowiak, A., Horska, E., Raszka, N., & Zelichowska, E. (2020). Towards building sustainable consumption: A study of second-hand buying intentions. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(3), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Boson, L. T., Elemo, Z., Engida, A., & Kant, S. (2023). Assessment of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Sustainable Business in Ethiopia Assessment of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Sustainable Business in Ethiopia. Logistics and Operation Management, 2(1), 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Bui, T., Lim, M. K., Sujanto, R. Y., Ongkowidjaja, M., & Tseng, M. (2022). Building a Hierarchical Sustainable Consumption Behavior Model in Qualitative Information : Consumer Behavior Influences on Social Impacts and Environmental Responses. Sustainability, 14(9877), 1–22.

- Byrne, B. m. (2011). Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus_ Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming.

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural Equation Modeling with M plus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming.

- Caferra, R., Imbert, E., Schirone, D. A., Tiranzoni, P., & Morone, A. (2023). Consumer analysis and the role of information in sustainable choices: A natural experiment. Frontiers in Environmental Economics, 1. [CrossRef]

- Carol Cavender, R. (2018). Exploring the Influence of Sustainability Knowledge and Orientation to Slow Consumption on Fashion Leaders’ Drivers of Fast Fashion Avoidance. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Business, 4(3), 90. [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, Ö. (2019). Knowledge, attitudes and behavior of consumers towards sustainability and ecological fashion. Textile and Leather Review, 2(3), 154–161. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. J., & Watchravesringkan, K. (Tu). (2018). Who are sustainably minded apparel shoppers? An investigation to the influencing factors of sustainable apparel consumption. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 46(2), 148–162. [CrossRef]

- Chi, T., Gerard, J., Yu, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021). A study of U.S. consumers’ intention to purchase slow fashion apparel: understanding the key determinants. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 14(1), 101–112. [CrossRef]

- ÇIVGIN, H., & KIZANLIKLI, M. (2022). Davranışsal Niyetin Yeşil Satın Alma Niyeti Üzerindeki Etkisinde Kontrol İnançların Aracı Rolü: Turizm Sektöründe Bir Araştırma. Güncel Turizm Araştırmaları Dergisi, 6(2), 536–553. [CrossRef]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173(June), 121092. [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B., Siraj, T., Harun, K., Rashid, O., Bari, A. B. M. M., Lekha, C., & Al, R. (2023). Sustainable Manufacturing and Service Economics Analyzing the critical success factors to implement green supply chain management in the apparel manufacturing industry : Implications for sustainable development goals in the emerging economies. Sustainable Manufacturing and Service Economics, 2(September 2022), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Dell, R. B., Holleran, S., & Ramakrishnan, R. (2002). Sample size determination. ILAR Journal, 43(4), 207–212. [CrossRef]

- DEMİRBAŞ, E. (2016). PRO-ENVIRONMENTAL CONCLUSIONS of CONSUMERS’ ENDURING INVOLVEMENT with RECYCLED PRODUCTS: ECO-AWARE PURCHASING BEHAVIOR and PSYCHOGRAPHICS. Journal of Administrative Sciences, 21(48), 275–309.

- Dhir, A., Sadiq, M., Talwar, S., Sakashita, M., & Kaur, P. (2021). Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services Why do retail consumers buy green apparel ? A knowledge-attitude-behaviour-context perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59(September 2020), 102398. [CrossRef]

- Durrani, S., Sohail, M., & Rana, M. W. (2023). The Influence of Shopping Motivation On Sustainable Consumption: A Study Related To Eco-Friendly Apparel. Journal of Social Sciences Review, 3(2), 248–268.

- Eagly, A. H. (2007). THE ADVANTAGES OF AN INCLUSIVE DEFINITION OF ATTITUDE. Social Cognition, 25(5), 582–602.

- Edeh, E., Lo, W.-J., & Khojasteh, J. (2023). Review of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal (Vol. 30, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P. S., Wiener, J. L., & Cobb-Walgren, C. (1991). The Role of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness in Motivating Environmentally Conscious Behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10(2), 102–117. [CrossRef]

- Eng, J. (2003). Sample size estimation: How many individuals should be studied? Radiology, 227(2), 309–313. [CrossRef]

- Fedrigo, D., & Hontelez, J. (2010). Sustainable consumption and production. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 14(1), 10–12. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D., Reinermann, J., Guillen, G., Desroches, C. T., Diddi, S., & Vergragt, P. J. (2021). Sustainable consumption communication : A review of an emerging fi eld of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 300, 126880. [CrossRef]

- Floriano, M. D. P., & de Matos, C. A. (2022). Understanding Brazilians’ Intentions in Consuming Sustainable Fashion. Brazilian Business Review, 19(5), 525–545. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

- Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(1), 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S., Ma, R., He, G., Chen, Z., & Liu, H. (2023). A study on the influence of product environmental information transparency on online consumers’ purchasing behavior of green agricultural products. Frontiers in Psychology, 14(April), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, T., Pacchera, F., Cagnetti, C., & Silvestri, C. (2023). Do Sustainable Consumers Have Sustainable Behaviors? An Empirical Study to Understand the Purchase of Food Products. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(5). [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A., & Islam, T. (2023). Factors leading to sustainable consumption behavior : an empirical investigation among millennial consumers. Kybernetes. [CrossRef]

- Gierszewska, G., & Seretny, M. (2019). Sustainable Behavior-The Need of Change in Consumer and Business Attitudes and Behavior. Foundations of Management, 11(1), 197–208. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J., Santos, A. R., Kieling, A. P., & Tezza, R. (2022). The influence of environmental engagement in the decision to purchase sustainable cosmetics: An analysis using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Revista de Administração Da UFSM, 15(3), 541–562. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling ( PLS-SEM ) Using R.

- Hasan, A. A. (2024). Theory of sustainable consumption behavior ( TSCB ) to predict renewable energy consumption behavior : A case of eco-tourism visitors of Bangladesh. Renewable Energy Consumption Behavior, 35(1), 101–118. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. (2022). Application of Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Application of Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Sustainable Clothing Consumption: Testing the Effect of Sustainable Clothing Consumption: Testing the Effect of Materialism and Sustainability . 7–7. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1600.

- Hasbullah, N. N., Sulaiman, Z., & Mas, A. (2022). Drivers of Sustainable Apparel Purchase Intention : An Empirical Study of Malaysian Millennial Consumers. Sustainability, 14(1945), 1–24.

- Hassan, S. H., Yeap, J. A. L., & Al-Kumaim, N. H. (2022). Sustainable Fashion Consumption: Advocating Philanthropic and Economic Motives in Clothing Disposal Behaviour. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(3), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J., Zhang, Y., & Ding, M. (2017). Sustainable supply chain management practices, supply chain dynamic capabilities, and enterprise performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Hosta, M., & Zabkar, V. (2021). Antecedents of Environmentally and Socially Responsible Sustainable Consumer Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(2), 273–293. [CrossRef]

- Hur, E., & Cassidy, T. (2019). Perceptions and attitudes towards sustainable fashion design: challenges and opportunities for implementing sustainability in fashion. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 12(2), 208–217. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., Lee, S., Jo, M., Cho, W., & Moon, J. (2021). The effect of sustainability-related information on the sensory evaluation and purchase behavior towards salami products. Food Science of Animal Resources, 41(1), 95–109. [CrossRef]

- Irene, S., & Gil-saura, I. (2020). Ethically Minded Consumer Behavior, Retailers ’ Commitment to Sustainable Development, and Store Equity in Hypermarkets. Sustainability, 12(8041), 1–17.

- Islam, M. M., & Khan, M. M. R. (2014). Environmental Sustainability Evaluation of Apparel Product: A Case Study on Knitted T-Shirt. Journal of Textiles, 2014, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A. M. (2018). The Gutenberg English Poetry Corpus: Exemplary Quantitative Narrative Analyses. Frontiers in Digital Humanities, 5(5), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, J., Rejman, K., Halicka, E., & Prandota, A. (2019). Influence of B2C Sustainability Labels in the Purchasing Behaviour of Polish Consumers in the Olive Oil Market. Olsztyn Economic Journal, 14(3), 299–311. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., Liu, C., & Kim, S. H. (2013). Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(4), 442–452. [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A. (2022). Sustainability and Consumer Behaviour. In Sustainability and Consumer Behaviour. [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. (2019). Green Apparel Buying : Role of Past Behavior, Knowledge and Peer Influence in the Assessment of Green Apparel Perceived Benefits Green Apparel Buying : Role of Past Behavior, Knowledge and Peer Influence. Journal of International Consumer Marketing ISSN:, 1530. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., & Choi, S. M. (2005). Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior: An Examination of Collectivism, Environmental Concern, and PCE. Advances in Consumer Research Volume 32, 36, 592–599. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/9156/volumes/v32/NA-32 [copyright.

- Kim, Y., & Oh, K. W. (2020). Effects of perceived sustainability level of sportswear product on purchase intention: Exploring the roles of perceived skepticism and perceived brand reputation. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(20), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kline, B. (2015). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling.

- Koszewska, M. (2016). Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes (Vol. 1).

- Kovacs, I., & Keresztes, E. R. (2022). Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Willingness to Pay for Credence Product Attributes of Sustainable Foods. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(7), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B., Manrai, A. K., & Manrai, L. A. (2017). conceptual framework and empirical study crossmark. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34(August 2015), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Kumar, K., Singh, R., Sá, J. C., Carvalho, S., & Santos, G. (2023). Modeling Environmentally Conscious Purchase Behavior: Examining the Role of Ethical Obligation and Green Self-Identity. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(8), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. (2022). Extending the theory of planned behavior: factors fostering millennials’ intention to purchase eco-sustainable products in an emerging market. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 65(8), 1507–1529. [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. (2023). Exploring the sustainable consumption behavior in emerging countries : The role of pro-environmental self-identity, attitude, and environmental protection emotion. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(8), 5174–5186. [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R., Jindal, A., Akram, U., Naik, B. K. R., & Halibas, A. S. (2023). Exploring the antecedents of sustainable consumers’ purchase intentions: Evidence from emerging countries. Sustainable Development, 31(1), 280–291. [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R. V. (2001). Some practical guidelines for effective sample size determination. American Statistician, 55(3), 187–193. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T. L., Park, H., Netravali, A. N., & Trejo, H. X. (2017). Closing the loop: a scalable zero-waste model for apparel reuse and recycling. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 10(3), 353–362. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., & Xu, Y. (2018). Second-hand clothing consumption: A generational cohort analysis of the Chinese market. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(1), 120–130. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. A., Wang, X., & Yang, Y. (2023). Sustainable Apparel Consumption: Personal Norms, CSR Expectations, and Hedonic vs. Utilitarian Shopping Value. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(11). [CrossRef]

- Lin, T. T., Yeh, Y., & Hsu, S. (2022). Analysis of the Effects of Perceived Value, Price Sensitivity, Word-of-Mouth, and Customer Satisfaction on Repurchase Intentions of Safety Shoes under the Consideration of Sustainability. Sustainability, 14(16546), 1–19.

- Maciaszczyk, M., Kwasek, A., Kocot, M., & Kocot, D. (2022). Determinants of Purchase Behavior of Young E-Consumers of Eco-Friendly Products to Further Sustainable Consumption Based on Evidence from Poland. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Madar, A., Huang, H. H., & Tseng, T.-H. (2013). Do Ethical Purchase Intentions Really Lead to Ethical Purchase Behavior? A Case of Animal-Testing Issues in Shampoo. International Business Research, 6(7), 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Mariadoss, B. J., Chi, T., Tansuhaj, P., & Pomirleanu, N. (2016). Influences of Firm Orientations on Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3406–3414. [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L., & Venter, B. (2019). Identity, self-concept and young women’s engagement with collaborative, sustainable fashion consumption models. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(4), 368–378. [CrossRef]

- Minbale, E., Bizuneh, B., Seife, W., Eyasu, A., Asfaw, T., & Sharew, S. (2024). Ethiopian Consumer ’ s Behavior towards Purchasing Locally Produced Apparel Products : An Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Complexity, 2024, 8745919.

- Minh, T. C., Nguyen, N., & Quynh, T. (2024). Factors affecting sustainable consumption behavior : Roles of pandemics and perceived consumer effectiveness. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 12(December 2023), 100158. [CrossRef]

- Mirabi, V., Akbariyeh, H., & Tahmasebifard, H. (2015). A Study of Factors Affecting on Customers Purchase Intention Case Study : the Agencies of Bono Brand Tile in Tehran. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology, 2(1), 267–273.

- Misron, A., Che Musa, N., & Mohd Salleh, M. S. (2023). A Conceptual Analysis of Sustainability Labeling on Packaging: Does it Impact Purchase Behavior? International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(5), 2327–2342. [CrossRef]

- Moretto, A., Macchion, L., Lion, A., Caniato, F., Danese, P., & Vinelli, A. (2018). Designing a roadmap towards a sustainable supply chain: A focus on the fashion industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 193, 169–184. [CrossRef]

- Muthukumarana, T. T., Karunathilake, H. P., Punchihewa, H. K. G., Manthilake, M. M. I. D., & Hewage, K. N. (2018). Life cycle environmental impacts of the apparel industry in Sri Lanka: Analysis of the energy sources. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 1346–1357. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R., Panwar, T., & Van Thang Nguyen, L. (2019). Sustainability in fashion and textiles: A survey from developing country. In Sustainable Technologies for Fashion and Textiles. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P. M., Vo, N. D., & Ho, N. N. Y. (2022). Exploring Green Purchase Intention of Fashion Products: A Transition Country Perspective. Asian Journal of Business Research, 12(2), 87–107. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H. (2023). Impact of behavioural factors on sustainable fashion usage intention: Evidence from consumers in Ho Chi Minh City. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 11(06), 4939–4955. [CrossRef]

- Niu, N., Fan, W., Ren, M., Li, M., & Zhong, Y. (2023). The Role of Social Norms and Personal Costs on Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16(May), 2059–2069. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, D., & Ringer, A. (2016). The Impact of Sustainability Information on Consumer Decision Making. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 20(4), 882–892. [CrossRef]

- Olbrich, R., Quaas, M. F.., & Baumgärtner, S. (2011). Personal norms of sustainability and their impact on management – The case of rangeland management in semi-arid regions (Issue 209).

- Orcan, F. (2018). Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Which One to Use First? Journal of Measurement and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 9(4), 414–421. [CrossRef]

- Park, H. G., & Lee, Y. J. (2015). The Efficiency and Productivity Analysis of Large Logistics Providers Services in Korea. Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 31(4), 469–476. [CrossRef]

- Park, H. J., & Lin, L. M. (2018). Exploring attitude – behavior gap in sustainable consumption : comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. Journal of Business Research, November 2017.

- Park, J., & Ha, S. (2014). Understanding Consumer Recycling Behavior: Combining the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 42(3), 278–291. [CrossRef]

- Park, M. J., Cho, H., Johnson, K. K. P., & Yurchisin, J. (2017). Use of behavioral reasoning theory to examine the role of social responsibility in attitudes toward apparel donation. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(3), 333–339. [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Modi, A., & Patel, J. (2016). Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29, 123–134. [CrossRef]

- Pinkse, J., & Bohnsack, R. (2021). Sustainable product innovation and changing consumer behavior: Sustainability affordances as triggers of adoption and usage. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(7), 3120–3130. [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M. J., Vocino, A., Grau, S. L., Garma, R., & Ferdous, A. S. (2012). The impact of general and carbon-related environmental knowledge on attitudes and behaviour of US consumers. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(3–4), 238–263. [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T. M., & Kopplin, C. S. (2021a). Bridge the gap : Consumers ’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123882. [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T. M., & Kopplin, C. S. (2021b). Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123882. [CrossRef]

- Raza, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Zhu, N., Hassan, Z., Gul, H., & Hussain, S. (2021). Sustainable Supply Management Practices and Sustainability Performance : The Dynamic Capability Perspective. SAGE Open, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Saari, U. A., Damberg, S., & Fr, L. (2021). Sustainable consumption behavior of Europeans : The influence of environmental knowledge and risk perception on environmental concern and behavioral intention. Ecological Economics, 189(107155). [CrossRef]

- Rizkalla, N. (2018). Determinants of Sustainable Consumption Behavior: An Examination of Consumption Values, PCE Environmental Concern and Environmental Knowledge. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. A., & Bacon, D. R. (1997). Exploring the Subtle Relationships between Environmental Concern and Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior. Journal of Business Research, 40(1), 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Rožman, M., Tominc, P., & Milfelner, B. (2020). A Comparative Study Using Two SEM Techniques on Di ff erent Samples Sizes for Determining Factors of Older Employee ’ s Motivation and Satisfaction. Sustainability Article, 12.

- Rumaningsih, M., Zailani, A., Suyamto, & Darmaningrum, K. (2022). Analysing consumer behavioural intention on sustainable organic food products. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147- 4478), 11(9), 404–415. [CrossRef]

- Rusyani, E., Lavuri, R., & Gunardi, A. (2021). Purchasing Eco-Sustainable Products : Interrelationship between Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Concern, Green Attitude, and Perceived Behavior. Sustainability, 13(4601), 1–12.

- Saeed, M. A., Farooq, A., Kersten, W., & Ben Abdelaziz, S. I. (2019). Sustainable product purchase: does information about product sustainability on social media affect purchase behavior? Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Sandin, G., & Peters, G. M. (2018). Environmental impact of textile reuse and recycling – A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 184, 353–365. [CrossRef]

- Sesini, G., & Castiglioni, C. (2020). New Trends and Patterns in Sustainable Consumption : A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability, 15(5939).

- Setyawan, A., Noermijati, N., Sunaryo, S., & Aisjah, S. (2018). Green product buying intentions among young consumers: Extending the application of theory of planned behavior. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 16(2), 145–154. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh Qazzafi. (2019). Consumer Buying Decision Process. International Journal of Scientific Research and Engineering Development-, 2(5), 130–133. https://bizfluent.com/how-does-5438201-consumer-buying-decision-process.html.

- Soyer, M., & Dittrich, K. (2021). Sustainable consumer behavior in purchasing, using and disposing of clothes. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(15). [CrossRef]

- Stoll, R. G., Borges, G. D. R., & Buron, T. A. (2019). a Influência Do Consumo Sustentável Na Decisão De Compra De Produtos Orgânicos ## the Influence of Sustainable Consumption in the Decision To Purchase Organic Products. Amazônia, Organizações e Sustentabilidade, 8(1), 129. [CrossRef]

- Sudhakara Reddy, B., & Kumar Ray, B. (2011). Understanding industrial energy use: Physical energy intensity changes in Indian manufacturing sector. Energy Policy, 39(11), 7234–7243. [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, I. S., & Wulandari, R. (2023). The Effect of Price Perception and Product Quality on Consumer Purchase Interest with Attitude and Perceived Behavior Control as an Intervention Study on Environmentally Friendly Food Packaging (Foopak). International Journal of Science and Management Studies (IJSMS), 6(1), 85–99. [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A., Sithipolvanichgul, J., Asmi, F., Anwar, M. A., & Dhir, A. (2023). Drivers of green apparel consumption: Digging a little deeper into green apparel buying intentions. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(6), 3997–4012. [CrossRef]

- Tang, T., & Bhamra, T. A. (2009). Understanding Consumer Behaviour to Reduce Environmental Impacts through Sustainable Product Design. Design Research Society Conference, 1970(July), 16–19. http://shura.shu.ac.uk/550/.

- Tanner, C., & Kast, S. W. (2003). Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Determinants of Green Purchases by Swiss Consumers. Psychology and Marketing, 20(10), 883–902. [CrossRef]

- Tantawi, P., Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, & Khaled Gad. (2009). Tantawi-Green Consciousness of Consumers in a Developing Country_ A Study of Egyptian Consumers.pdf.

- Taufique, K. M. R., Vocino, A., & Polonsky, M. J. (2017). The influence of eco-label knowledge and trust on pro-environmental consumer behaviour in an emerging market. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 25(7), 511–529. [CrossRef]

- Testa, F., Pretner, G., Iovino, R., Bianchi, G., & Tessitore, S. (2020). Drivers to green consumption: a systematic review. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 0123456789.

- Thøgersen, J. (2006). Norms for environmentally responsible behaviour: An extended taxonomy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 26(4), 247–261. [CrossRef]