Submitted:

26 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

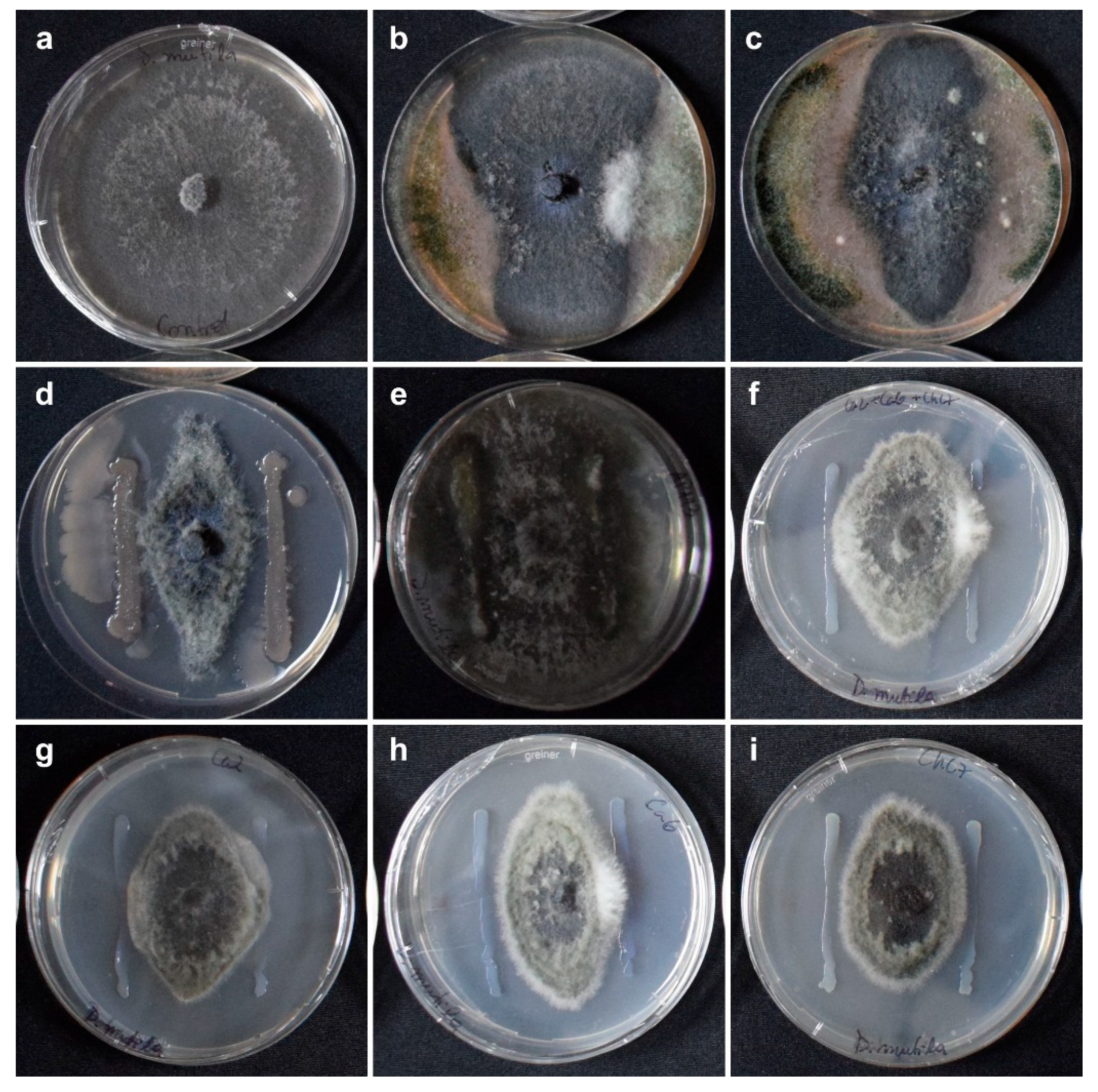

2.1. Selection of Active Ingredients of Chemical and Biological Fungicides

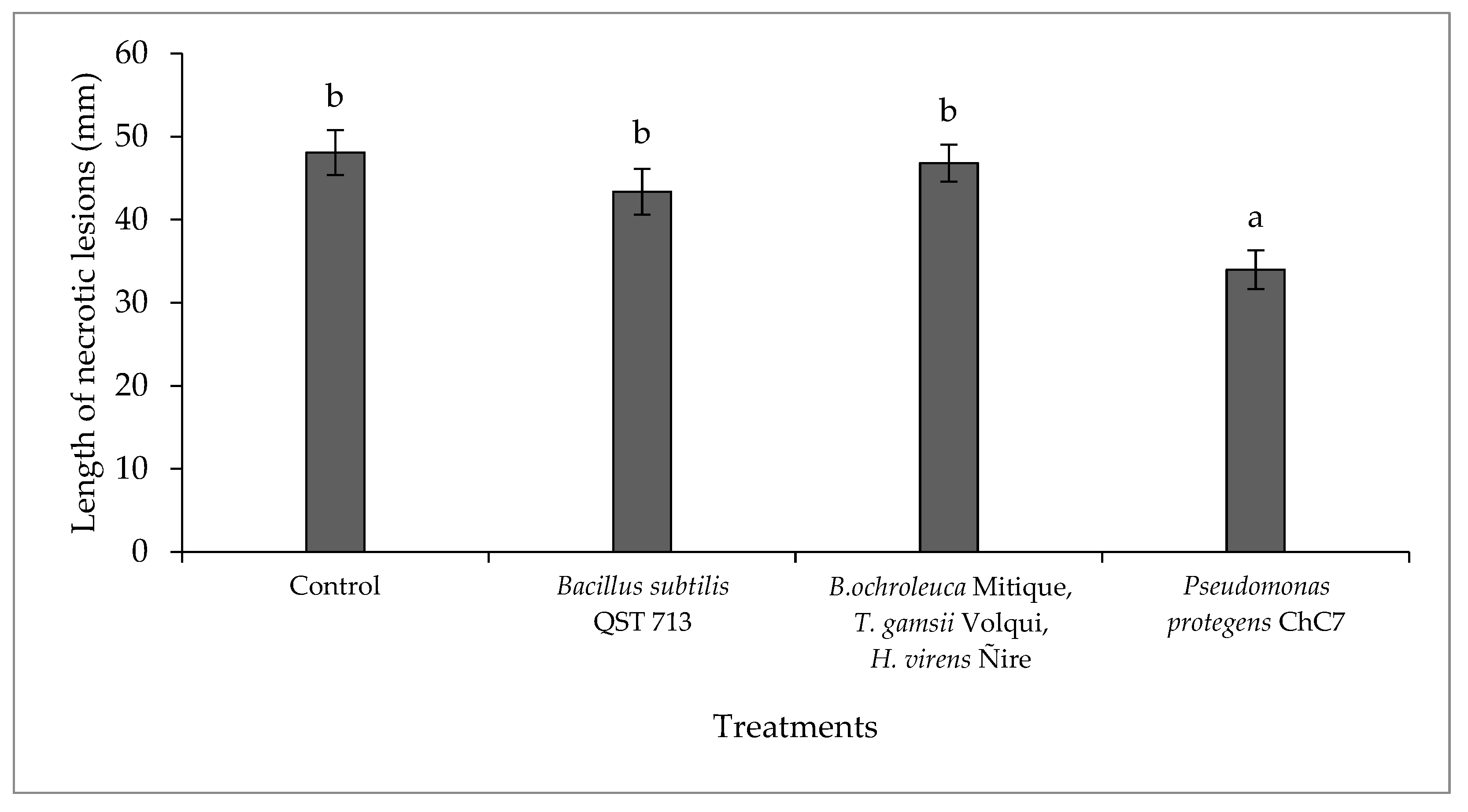

2.2. Assessment of Effectiveness of Chemical and Biological Fungicides against Diplodia mutila in Hazelnut Plants under Pot-Controlled Conditions

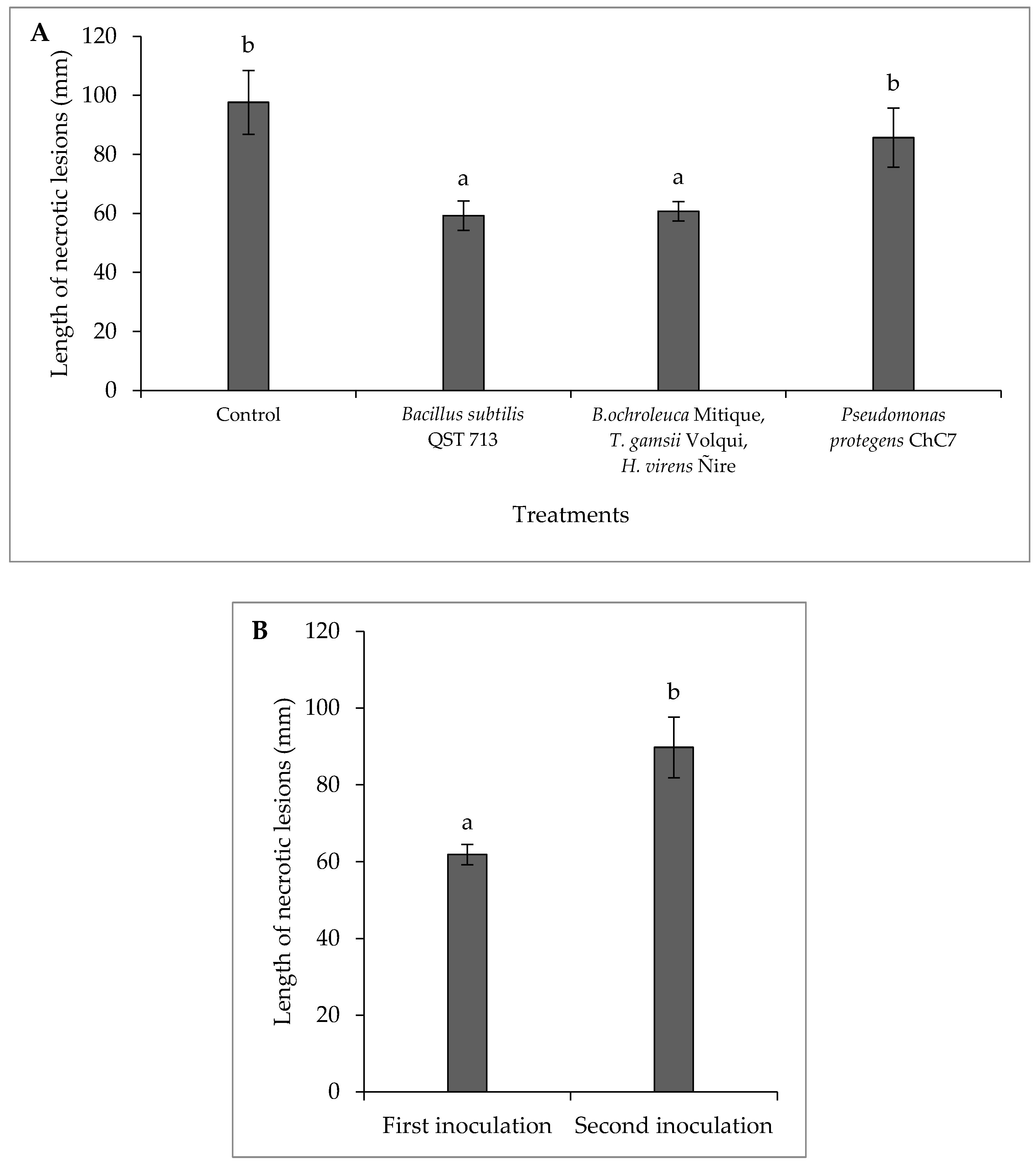

2.3. Assessment of Effectiveness of Chemical and Biological Fungicides against Diplodia mutila under Field Conditions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phytopathogenic Fungus

4.2. In Vitro Pathogen Control Assays

4.3. Selection of Treatments with Fungicidal Activity against Diplodia mutila

4.4. Assessment of Effectiveness of Chemical and Biological Fungicides against D. mutila in Hazelnut Plants under Controlled Conditions

4.5. Assessment of Effectiveness of Chemical and Biological Fungicides against D. mutila under Field Conditions

4.5.1. Study Area

4.5.2. Fungal Inoculations in Hazelnut Trees

4.6. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centro de Información de Recursos Naturales (CIREN) Catastro Frutícola Región Metropolitana 2023 2023.

- Latorre, B. Compendio de las enfermedades de las plantas; Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2018; ISBN 978-956-14-2297-1. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, G.A.; Zoffoli, J.P.; Ferrada, E.E.; Lolas, M. Identification and Pathogenicity of Diplodia, Neofusicoccum, Cadophora, and Diaporthe Species Associated with Cordon Dieback in Kiwifruit Cultivar Hayward in Central Chile. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 1308–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larach, A.; Torres, C.; Riquelme, N.; Valenzuela, M.; Salgado, E.; Seeger, M.; Besoain, X. Yield Loss Estimation and Pathogen Identification from Botryosphaeria Dieback in Vineyards of Central Chile over Two Growing Seasons. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 2020, 59, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, I.; Besoain, X.; Saa, S.; Peach-Fine, E.; Cadiz Morales, F.; Riquelme, N.; Larach, A.; Morales, J.; Ezcurra, E.; Ashworth, V.E.T.M.; et al. Identity and Pathogenicity of Botryosphaeriaceae and Diaporthaceae from Juglans Regia in Chile. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2022, 61, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Fabi, A.; Varvaro, L. Summer Heat and Low Soil Organic Matter Influence Severity of Hazelnut Cytospora Canker. Phytopathology® 2014, 104, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisario, A.; Maccaroni, M.; Coramusi, A. First Report of Twig Canker of Hazelnut Caused by Fusarium Lateritium in Italy. Plant Disease 2005, 89, 106–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, I.; Monchiero, M.; Gullino, M.L.; Guarnaccia, V. Characterization and Pathogenicity of Fungal Species Associated with Hazelnut Trunk Diseases in North-Western Italy. J Plant Pathol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiman, N.G.; Webber, J.B.; Wiseman, M.; Merlet, L. Identity and Pathogenicity of Some Fungi Associated with Hazelnut (Corylus Avellana L.) Trunk Cankers in Oregon. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Contreras, J.; Galdames Gutierrez, R.; Ogass Contreras, K.; Pérez Fuentealba, S. First Report of Diaporthe Foeniculina Causing Black Tip and Necrotic Spot on Hazelnut Kernel in Chile. Plant Disease 2020, 104, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.A.; Pérez, S.M. First Report of Shoot Blight and Canker Caused by Diplodia Coryli in Hazelnut Trees in Chile. Plant Disease 2013, 97, 144–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolas, M.A.; Latorre, B.A.; Ferrada, E.; Grinbergs, D.; Chilian, J.; Ortega-Farias, S.; Campillay-Llanos, W.; Díaz, G.A. Occurrence of Neofusicoccum Parvum Causing Canker and Branch Dieback of European Hazelnut in Maule Region, Chile. Plant Disease, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Elizondo, E.; San Martín, J.; Ruiz, B.; Rojas, K.; Lisperguer, M.J.; De Gregorio, T. Fungi Associated with Wood Damage in Hazelnut ( Corylus Avellana L.) between the Maule and Araucanía Regions of Chile. Acta Hortic. [CrossRef]

- Moya-Elizondo, E.A.; Ruiz, B.E.; Gambaro, J.R.; San Martin, J.G.; Lisperguer, M.J.; De Gregorio, T. First Report of Diplodia Mutila Causing Wood Necrosis in European Hazelnut in Chile. Plant Disease 2023, 107, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slippers, B.; Crous, P.W.; Jami, F.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Wingfield, M.J. Diversity in the Botryosphaeriales: Looking Back, Looking Forward. Fungal Biology 2017, 121, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl, J.W.M.; Slippers, B.; Roux, J.; Wingfield, M.J. Cankers and Other Diseases Caused by the Botryosphaeriaceae. In Infectious forest diseases; Gonthier, P., Nicolotti, G., Eds.; CABI: UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-78064-040-2. [Google Scholar]

- Slippers, B.; Wingfield, M.J. Botryosphaeriaceae as Endophytes and Latent Pathogens of Woody Plants: Diversity, Ecology and Impact. Fungal Biology Reviews 2007, 21, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaldeddu, B.T.; Deidda, A.; Scanu, B.; Franceschini, A.; Alves, A.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Phillips, A.J.L. Phylogeny, Morphology and Pathogenicity of Botryosphaeriaceae, Diatrypaceae and Gnomoniaceae Associated with Branch Diseases of Hazelnut in Sardinia (Italy). Eur J Plant Pathol 2016, 146, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, W.M.; Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Trouillas, F.P. Dothiorella Vidmadera, a Novel Species from Grapevines in Australia and Notes on Spencermartinsia. Fungal Diversity 2013, 61, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.A.; Latorre, B.A.; Ferrada, E.; Lolas, M. Identification and Characterization of Diplodia Mutila, D. Seriata, Phacidiopycnis Washingtonensis and Phacidium Lacerum Obtained from Apple (Malus x Domestica) Fruit Rot in Maule Region, Chile. Eur J Plant Pathol 2019, 153, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.A.; Auger, J.; Besoain, X.; Bordeu, E.; Latorre, B.A. Prevalence and Pathogenicity of Fungi Associated with Grapevine Trunk Diseases in Chilean Vineyards. Cienc. Inv. Agr. 2013, 40, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.A.; Latorre, B.A.; Ferrada, E.; Gutiérrez, M.; Bravo, F.; Lolas, M. First Report of Diplodia Mutila Causing Branch Dieback of English Walnut Cv. Chandler in the Maule Region, Chile. Plant Disease 2018, 102, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besoain, X.; Guajardo, J.; Camps, R. First Report of Diplodia Mutila Causing Gummy Canker in Araucaria Araucana in Chile. Plant Disease 2017, 101, 1328–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, C.; Bacchetta, L.; Bellincontro, A.; Cristofori, V. Advances in Cultivar Choice, Hazelnut Orchard Management, and Nut Storage to Enhance Product Quality and Safety: An Overview. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 101, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondello, V.; Songy, A.; Battiston, E.; Pinto, C.; Coppin, C.; Trotel-Aziz, P.; Clément, C.; Mugnai, L.; Fontaine, F. Grapevine Trunk Diseases: A Review of Fifteen Years of Trials for Their Control with Chemicals and Biocontrol Agents. Plant Disease 2018, 102, 1189–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission Active Substances Considered Approved According to Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 2023.

- Ragazzi, A.; Moricca, S.; Vagniluca, S.; Dellavalle, I. Antagonism of Acremonium Mucronatum towards Diplodia Mutila in Tests in Vitro and in Situ. European Journal of Forest Pathology 1996, 26, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, M.C.; Lutz, M.C.; Lódolo, X.; Basso, C.N. In Vitro and in Vivo Activity of Chemical Fungicides and a Biofungicide for the Control of Wood Diseases Caused by Botryosphaeriales Fungi in Apple and Pear. International Journal of Pest Management 2022, 68, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenfaoui, J.; Lahlali, R.; Laasli, S.-E.; Lahmamsi, H.; Goura, K.; Radouane, N.; Taoussi, M.; Fardi, M.; Tahiri, A.; Barka, E.A.; et al. Unlocking the Potential of Rhizobacteria in Moroccan Vineyard Soils: Biocontrol of Grapevine Trunk Diseases and Plant Growth Promotion. Biological Control 2023, 186, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyl, K. Effect of Pseudomonas Spp. on Inoculation of Young Plants of Fraxinus Excelsior Stem with Diplodia Mutila. Dendrobiology 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.K.; Wells, H.D.; Markham, C.R. In Vitro Antagonism of Trichoderma Species Against Six Fungal Plant Pathogens. Phytopathology 1982, 72, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, A.; Cibelli, F.; Lops, F.; Raimondo, M.L. Characterization of Botryosphaeriaceae Species as Causal Agents of Trunk Diseases on Grapevines. Plant Disease 2015, 99, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, A.L.; Gil, P.M.; Latorre, B.A.; Rosales, I.M. Characterization and Pathogenicity of Botryosphaeriaceae Species Obtained from Avocado Trees with Branch Canker and Dieback and from Avocado Fruit with Stem End Rot in Chile. Plant Disease 2019, 103, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.A.; Valdez, A.; Halleen, F.; Ferrada, E.; Lolas, M.; Latorre, B.A. Characterization and Pathogenicity of Diplodia, Lasiodiplodia, and Neofusicoccum Species Causing Botryosphaeria Canker and Dieback of Apple Trees in Central Chile. Plant Disease 2022, 106, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.A.; Rooney-Latham, S.; Brown, A.A.; McCormick, M.; Baston, D. Pathogenicity of Three Botryosphaeriaceae Fungi, Diplodia Scrobiculata, Diplodia Mutila, and Dothiorella Californica, Isolated from Coast Redwood ( Sequoia Sempervirens ) in California. Forest Pathology 2022, 52, e12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassiadou, M; Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Brancato, A.; Bura, L.; Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Chaideftou, E.; Chiusolo, A.; Crivellente, F.; et al.; European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Peer Review of the Pesticide Risk Assessment of the Active Substance Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens Strain QST 713 (Formerly Bacillus Subtilis Strain QST 713). EFS2 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Elizondo, E.; Cattan, N.; Ruiz, B.; San Martin, J. Ability of Chilean Bacteria to Control Pseudomonas Syringae Pv. Actinidiae in Kiwifruit by Antibiosis and Induction of Resistance. J Plant Pathol 2019, 101, 849–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Elizondo, E.; Lindow, S.; Sands, D.; Reifschneider, F.; Vanneste, J.; Lopes, C.; Rossato, M. The Plant Health, a View from the Plant Bacteriology; Moya-Elizondo, E.; Chillán, Chile., 2019; ISBN 978-956-401-337-4.

- Castro Tapia, M.P.; Madariaga Burrows, R.P.; Ruiz Sepúlveda, B.; Vargas Concha, M.; Vera Palma, C.; Moya-Elizondo, E.A. Antagonistic Activity of Chilean Strains of Pseudomonas Protegens Against Fungi Causing Crown and Root Rot of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Elizondo, E.A.; Cattan, N.C.; Arismendi, N.L.; Doussoulin, H.A. Determination of 2, 4-Diacetylphloroglucinol (2, 4-DAPG) and Phenazine-Producing Pseudomonas Spp. in Wheat Crops in Southern Chile. In Proceedings of the Phytopathology; AMER PHYTOPATHOLOGICAL SOC 3340 PILOT KNOB ROAD, ST PAUL, MN 55121 USA, 2013; Vol. 103, pp. 100–100.

- Ramette, A.; Frapolli, M.; Saux, M.F.-L.; Gruffaz, C.; Meyer, J.-M.; Défago, G.; Sutra, L.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Pseudomonas Protegens Sp. Nov., Widespread Plant-Protecting Bacteria Producing the Biocontrol Compounds 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol and Pyoluteorin. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2011, 34, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, D.M.; Mavrodi, D.V.; Van Pelt, J.A.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van Loon, L.C.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced Systemic Resistance in Arabidopsis Thaliana Against Pseudomonas Syringae Pv. Tomato by 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol-Producing Pseudomonas Fluorescens. Phytopathology® 2012, 102, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Shan, X.; Duan, Y. Endophytic Bacterium Pseudomonas Protegens Suppresses Mycelial Growth of Botryosphaeria Dothidea and Decreases Its Pathogenicity to Postharvest Fruits. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1069517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertuzzi, T.; Leni, G.; Bulla, G.; Giorni, P. Reduction of Mycotoxigenic Fungi Growth and Their Mycotoxin Production by Bacillus Subtilis QST 713. Toxins 2022, 14, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Bacillus Subtilis Strain QST 713 (PC Code 006479) Biopesticide Registration Action Document 2006.

- Silva-Valderrama, I.; Toapanta, D.; Miccono, M.D.L.A.; Lolas, M.; Díaz, G.A.; Cantu, D.; Castro, A. Biocontrol Potential of Grapevine Endophytic and Rhizospheric Fungi Against Trunk Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 614620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesguida, O.; Haidar, R.; Yacoub, A.; Dreux-Zigha, A.; Berthon, J.-Y.; Guyoneaud, R.; Attard, E.; Rey, P. Microbial Biological Control of Fungi Associated with Grapevine Trunk Diseases: A Review of Strain Diversity, Modes of Action, and Advantages and Limits of Current Strategies. JoF 2023, 9, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.; Pérez, S. First Report of Diaporthe Australafricana -Caused Stem Canker and Dieback in European Hazelnut ( Corylus Avellana L.) in Chile. Plant Disease 2013, 97, 1657–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramaje, D.; Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Sosnowski, M.R. Managing Grapevine Trunk Diseases With Respect to Etiology and Epidemiology: Current Strategies and Future Prospects. Plant Disease 2018, 102, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntzmann, P.; Villaume, S.; Bertsch, C. Conidia Dispersal of Diplodia Species in a French Vineyard. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 2009, 48, 150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Morgan, D.P.; Hasey, J.K.; Anderson, K.; Michailides, T.J. Phylogeny, Morphology, Distribution, and Pathogenicity of Botryosphaeriaceae and Diaporthaceae from English Walnut in California. Plant Disease 2014, 98, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverri, P.; Samuels, G.J.; Stewart, E.L. Hypocrea Virens Sp. Nov., the Teleomorph of Trichoderma Virens. Mycologia 2001, 93, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinu, K.; Sati, P.; Pandey, A. Trichoderma Gamsii (NFCCI 2177): A Newly Isolated Endophytic, Psychrotolerant, Plant Growth Promoting, and Antagonistic Fungal Strain. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, E. THE REPRODUCTION OF HAZELNUT (CORYLUS AVELLANA L.): A REVIEW. Acta Hortic. 1994, 195–210. [CrossRef]

- Pasqualotto, G.; Carraro, V.; De Gregorio, T.; Huerta, E.S.; Anfodillo, T. Girdling of Fruit-Bearing Branches of Corylus Avellana Reduces Seed Mass While Defoliation Does Not. Scientia Horticulturae 2019, 255, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolpe, N. Descripciones de Los Principales Suelos de La VIII Región de Chile; Publicaciones - Departamento de Suelos y Recursos Naturales; Trama Impresores S.A: Chillán, Chile.; Vol. 1;

- Aćimović, S.G.; Harmon, C.L.; Bec, S.; Wyka, S.; Broders, K.; Doccola, J.J. First Report of Diplodia Corticola Causing Decline of Red Oak ( Quercus Rubra ) Trees in Maine. Plant Disease 2016, 100, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, S.; Billones-Baaijens, R.; Steel, C.C.; Stodart, B.J.; Savocchia, S. Pathogenicity and Progression of Botryosphaeriaceae Associated with Dieback in Walnut Orchards in Australia. Eur J Plant Pathol 2024, 168, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradinas, A.; Ramade, L.; Mulot-Greffeuille, C.; Hamidi, R.; Thomas, M.; Toillon, J. Phenological Growth Stages of ‘Barcelona’ Hazelnut (Corylus Avellana L.) Described Using an Extended BBCH Scale. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 296, 110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarini, M.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Casanoves, F.; Di Rienzo, J.; Robledo, C. InfoStat. User’s Manual 2008.

| Incubation time | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungicide group / Active ingredient | 48 hours | 5 days | 14 days |

| (B) Methyl benzimidazole carbamate (MBC) fungicides | |||

| Methyl thiophanate | (++++)1 | (++++) | (++) |

| (C) Quinone outside inhibitor (QoI) Fungicides | |||

| Pyraclostrobin | (++) | (-) | (-) |

| Azoxystrobin/Difenoconazole | (++) | (+) | (-) |

| Trifloxystrobin | (+) | (-) | (-) |

| Kresoxim methyl/Miclobutanil | (++) | (-) | (-) |

| Kresoxim methyl/Tebuconazole | (+++) | (+) | (-) |

| (C) Succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor (SDHI) fungicides | |||

| Penthiopyrad | (++) | (-) | (-) |

| Fluxapyroxad/Pyraclostrobin | (+++) | (++) | (++) |

| Fluopyram/Tebuconazole | (+++) | (++) | (++) |

| (C) Not grouped | |||

| Fluazinam | (++++) | (+++) | (++) |

| (D) Anilinopyrimidine (AP) fungicides | |||

| Pyrimethanyl/Difenoconazole | (++) | (-) | (-) |

| (G) Demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicides (SBI: Class I) | |||

| Difenoconazole2 | (++) | (+) | (-) |

| Difenoconazole3 | (++) | (-) | (-) |

| Difenoconazole4 | (++) | (+) | (-) |

| Miclobutanil | (++) | (-) | (-) |

| Difenoconazole/Kresoxim methyl | (++) | (-) | (-) |

| Tebuconazole | (+++) | (++) | (++) |

| Prochloraz | (+++) | (+++) | (++) |

| (M) Dithiocarbamates and relatives (electrophiles) | |||

| Mancozeb | (++++) | (-) | (-) |

| Natural extracts & salts | |||

| Potassium Hydrogenicarbonate | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Extracts of Quillaja saponaria and Yucca schidigera | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Plant extracts and natural fatty acids | (+++) | (-) | (-) |

| Bacterial strain | Percentage of mycelial inhibition | |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas protegens Ca2 | 41.4 | abc |

| Pseudomonas protegens Ca6 | 37.9 | ab |

| Pseudomonas protegens ChC7 | 45.3 | bc |

| P. protegens strains Ca2+Ca6+ChC7 | 42.2 | abc |

| Pantoea sp. AP113 | 6.3 | a |

| Bacillus subtilis QST 713 | 51.9 | c |

| Interquartile range (IQR) | 28.2 | |

| P-value | 0.02 | |

| Treatments | Mean length (mm) of necrotic lesions ж in inoculated branches | |

|---|---|---|

| Water control | 50.9 | d |

| Bacillus subtilis QST 713 | 33.9 | bc |

|

Bionectria ochroleuca Mitique Trichoderma gamsii Volqui Hypocrea virens Ñire |

23.1 | ab |

| Pseudomonas protegens ChC7 | 26.9 | bc |

| Fluazinam | 23.9 | ab |

| Fluopyram/Tebuconazole | 25.7 | abc |

| Fluxapyroxad/Pyraclostrobin | 19.9 | a |

| Prochloraz | 34.6 | c |

| Tebuconazole | 31.1 | bc |

| Coefficient of variation | 9.5 | |

| P-value | <0.01 | |

| Mean length of necrotic lesions (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Inoculation on the day of fungicide application | Inoculation 24 h after fungicide application |

| Control | 48.1 | 45.4 |

| Fluazinam | 46.7 | 45.6 |

| Fluopyram/Tebuconazole | 60.7 | 36.0 |

| Fluxapyroxad/Pyraclostrobin | 45.0 | 32.5 |

| Prochloraz | 45.4 | 41.5 |

| Tebuconazole | 50.9 | 39.3 |

| Average | 49.5 B | 40.1 A |

| Coefficient of variation | 6.34 | |

| P-value Inoculation time | 0.008 | |

| Mean length of necrosis (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Inoculation on the day of fungicide application | Inoculation 24 h after fungicide application | ||||

| Control | 71.8 | c | A | 123.8 | b | B |

| Fluazinam | 60.2 | bc | A | 108.6 | b | B |

| Fluopyram/Tebuconazole | 45.3 | a | A | 87.8 | a | B |

| Fluxapyroxad/Pyraclostrobin | 48.7 | a | A | 80.8 | a | B |

| Penthiopyrad | 45.5 | a | A | 121.8 | b | B |

| Prochloraz | 54.3 | ab | A | 113.0 | b | B |

| Tebuconazole | 47.9 | a | A | 76.9 | a | B |

| Average | 72.2 | 101.8 | ||||

| Coefficient of variation | 2.75 | |||||

| P-value T x I | < 0.01 | |||||

| Active ingredient | Formulation | Trade name | Manufacturer | Commercial dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluazinam | 500 g L-1 SC | Shirlan ® 500 | Syngenta | 75 mL hL-1 (Apple trees) |

| Fluopyram/Tebuconazole | 200/200 g L-1 SC | Luna ® Experience 400 | Bayer | 40 mL hL-1 (Stone and pome trees) |

| Fluxapiroxad/Pyraclostrobin | 250/250 g L-1 SC | Elmus ® | BASF | 40 mL hL-1 (Stone and pome trees) |

| Penthiopyrad | 200 g L-1 SC | Fontelis ® | Corteva | 40 mL hL-1 (Apple trees) |

| Prochloraz | 400 g L-1 EC | Mirage 40% | Adama | 120 mL hL-1 (Wheat and barley) |

| Tebuconazole | 430 g L-1 SC | Tebuconazole 430 | Agrospec | 40 mL hL-1 (Stone trees) |

| Bacillus subtilis QST 713 | 13,68 g L-1 SC (1 x 109 cfu g-1) |

Serenade ® ASO | Bayer | 600 mL hL-1 (Stone and pome trees) |

|

Bionectria ochroleuca Mitique Trichoderma gamsii Volqui Hypocrea virens Ñire |

10/10/10 g kg-1 WG (3 x 108 cfu g-1) |

Mamull ® | Bio Insumos Nativa |

100 g hL-1 (Stone and pome trees) |

| Pseudomonas protegens ChC7 | 1 x 107 | N/D1 | N/D | 1000 mL hL-1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).