Submitted:

27 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

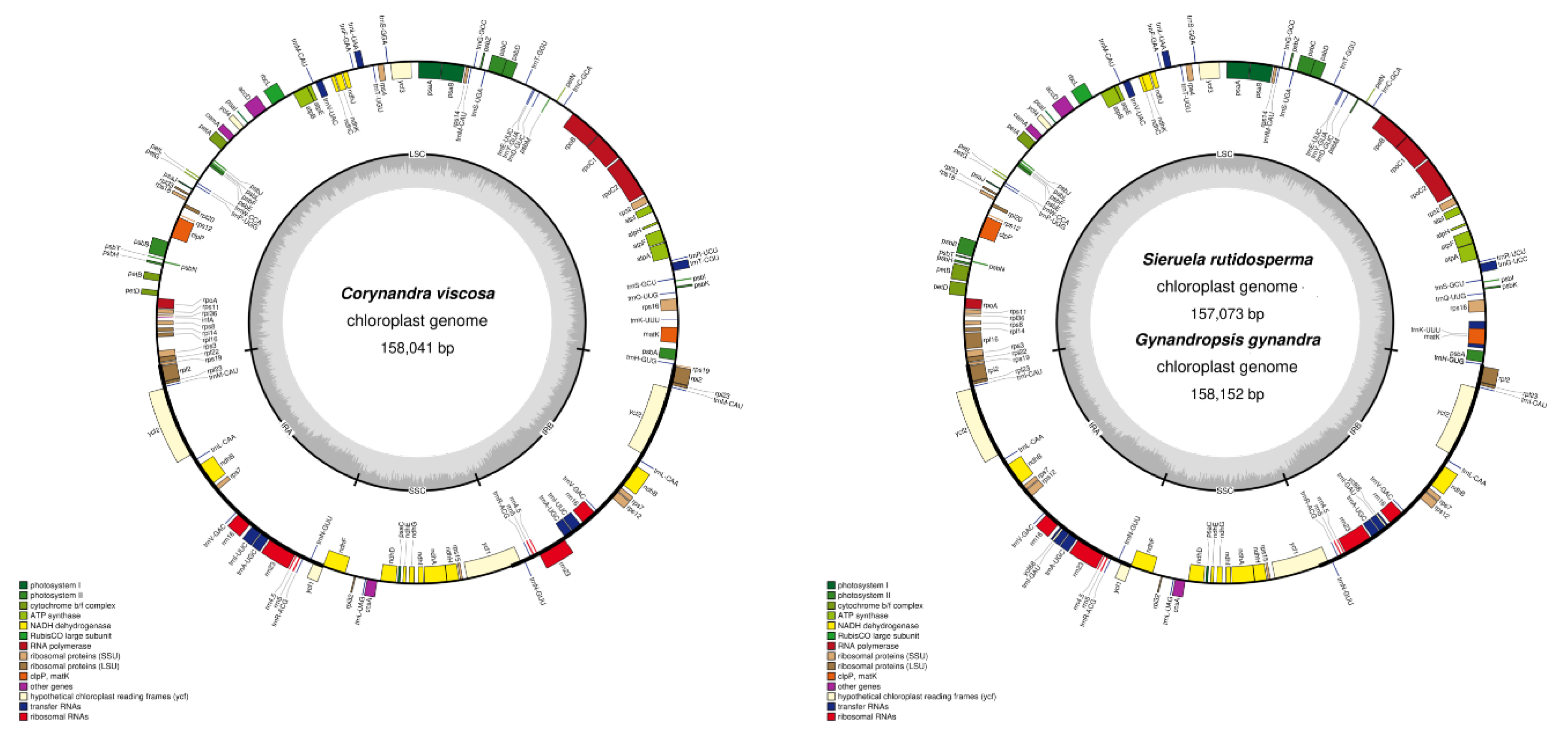

2.1. Characteristics of Three Cleomaceae Species Chloroplast Genomes

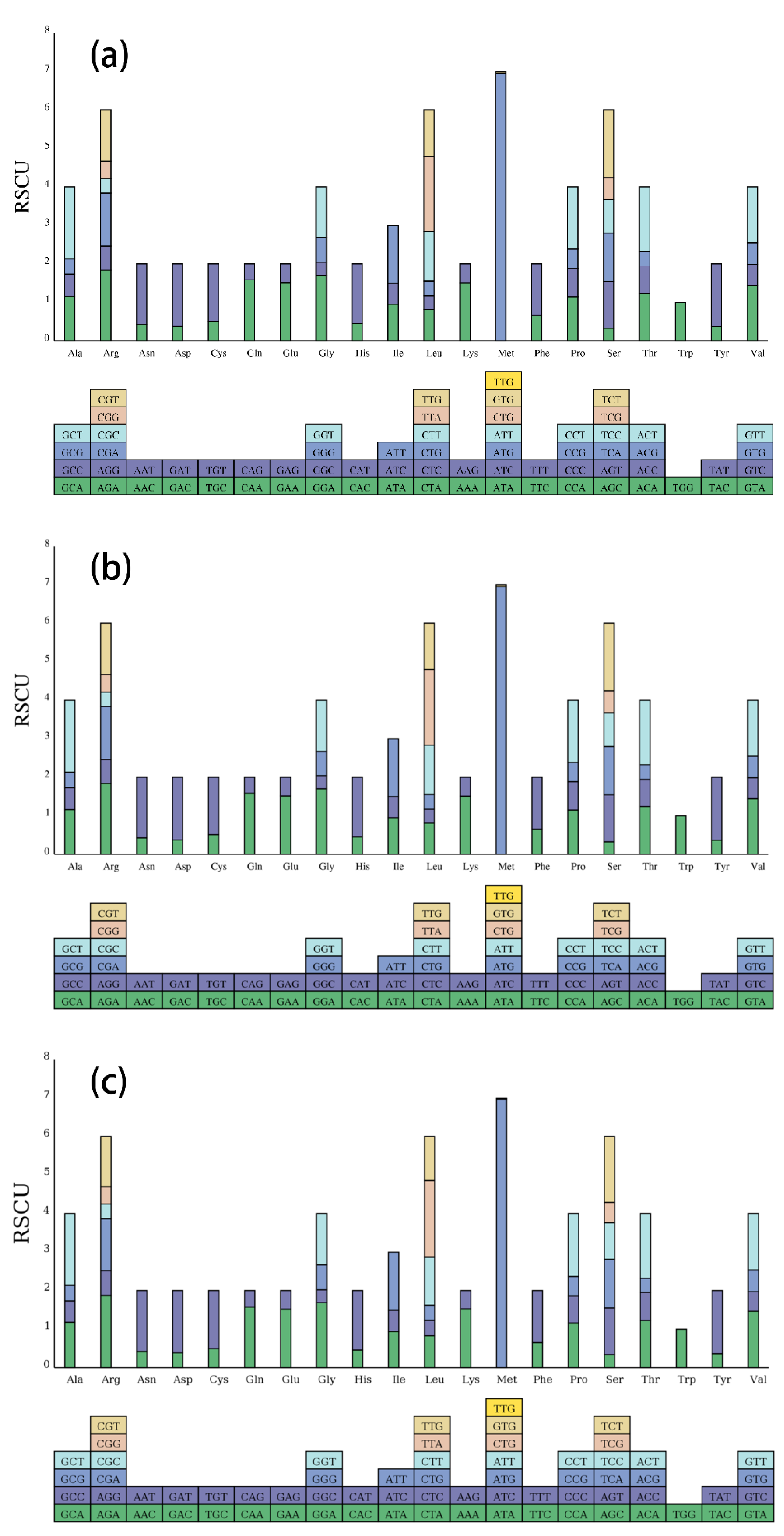

2.2. Codon Usage Statistics

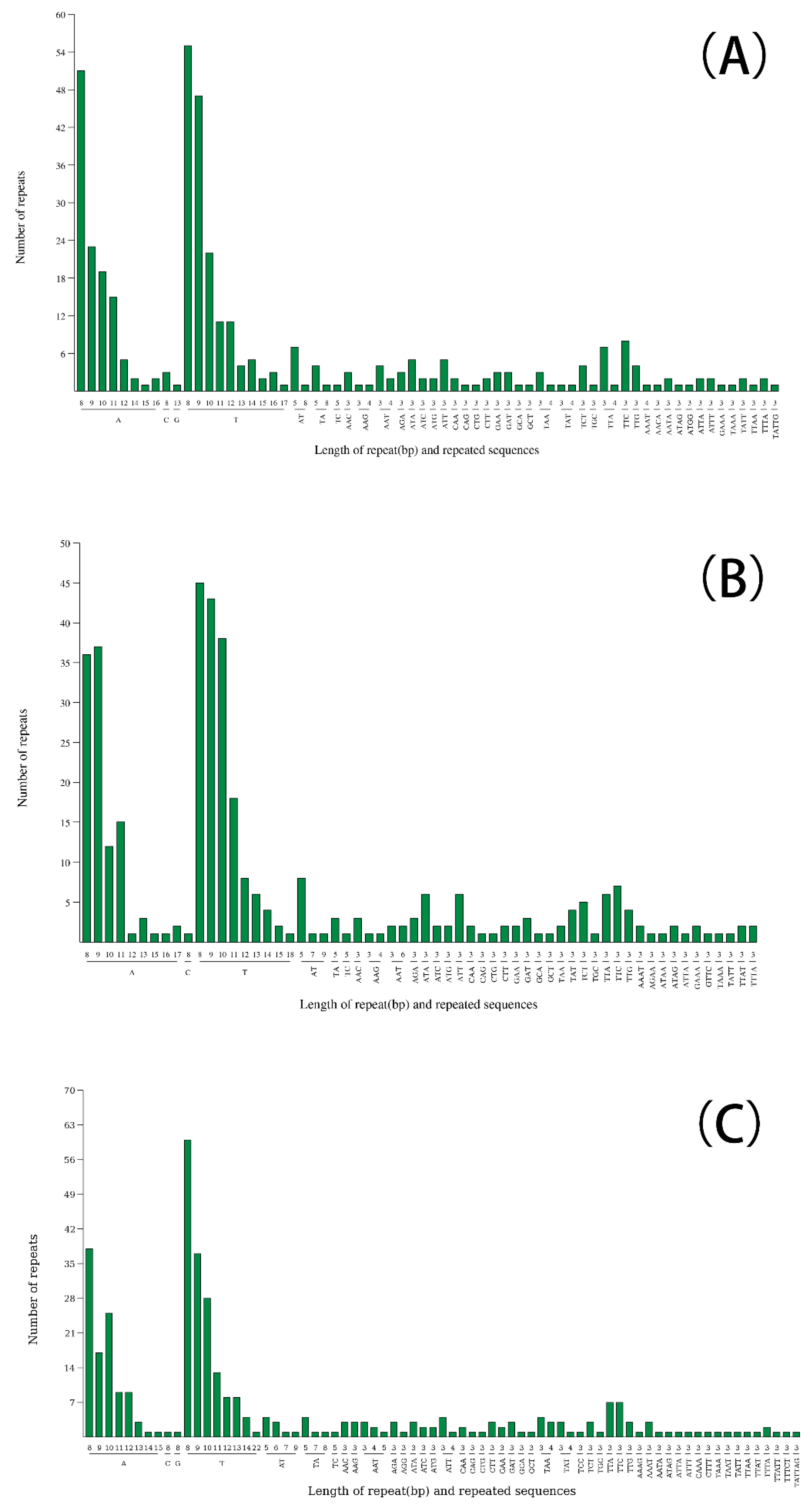

2.3. Repeat Sequence Analysis

2.4. SSR Analysis

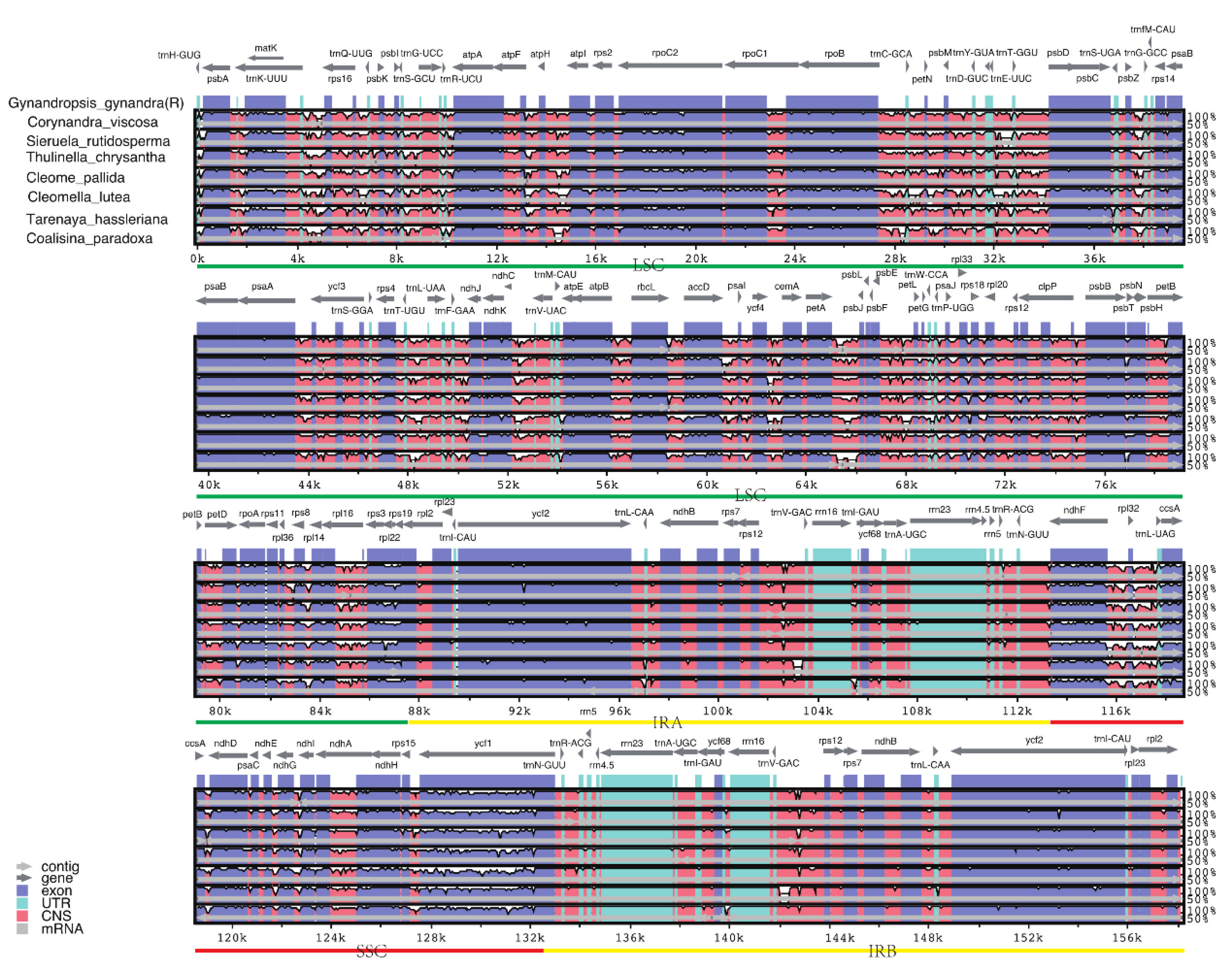

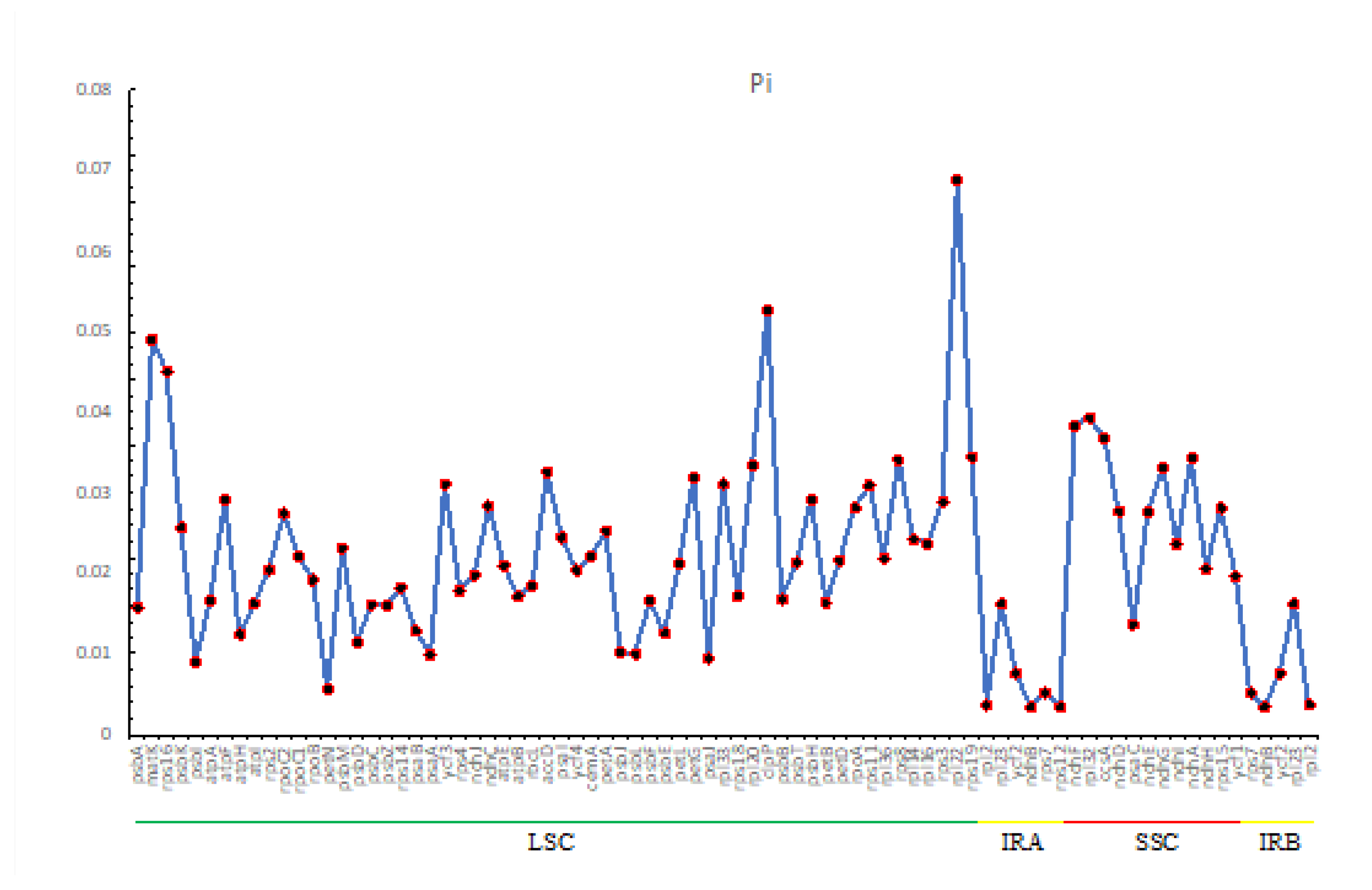

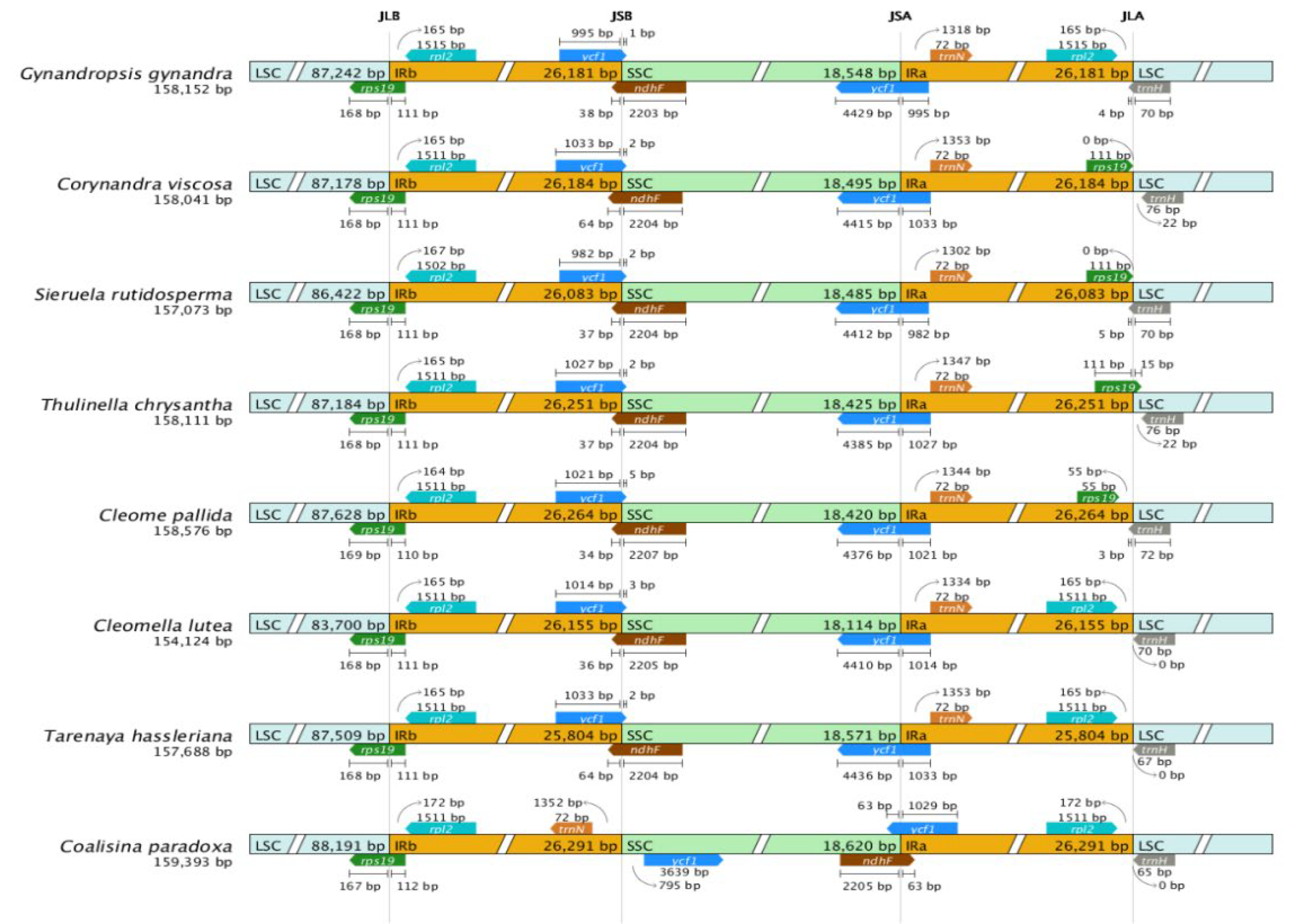

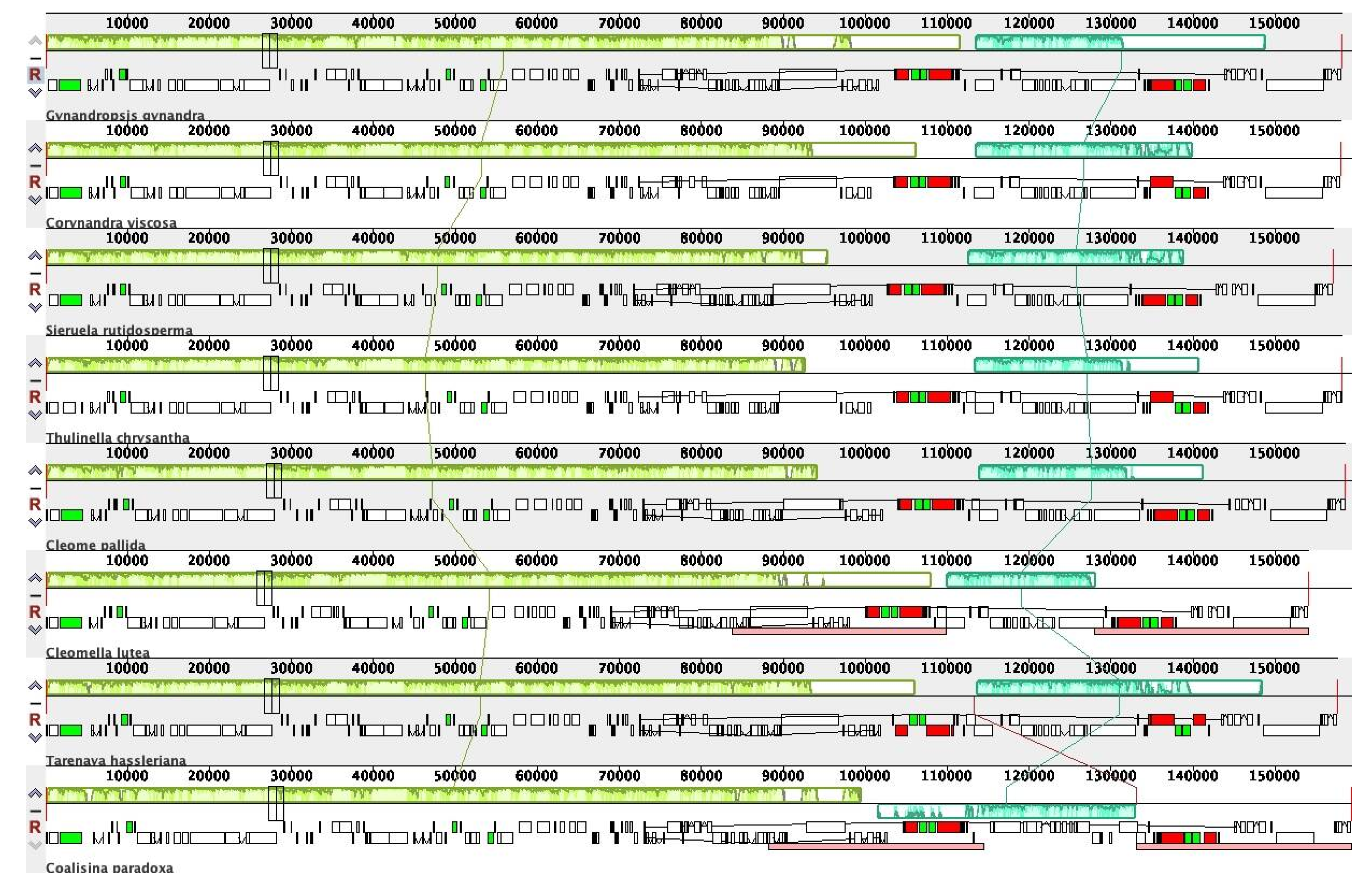

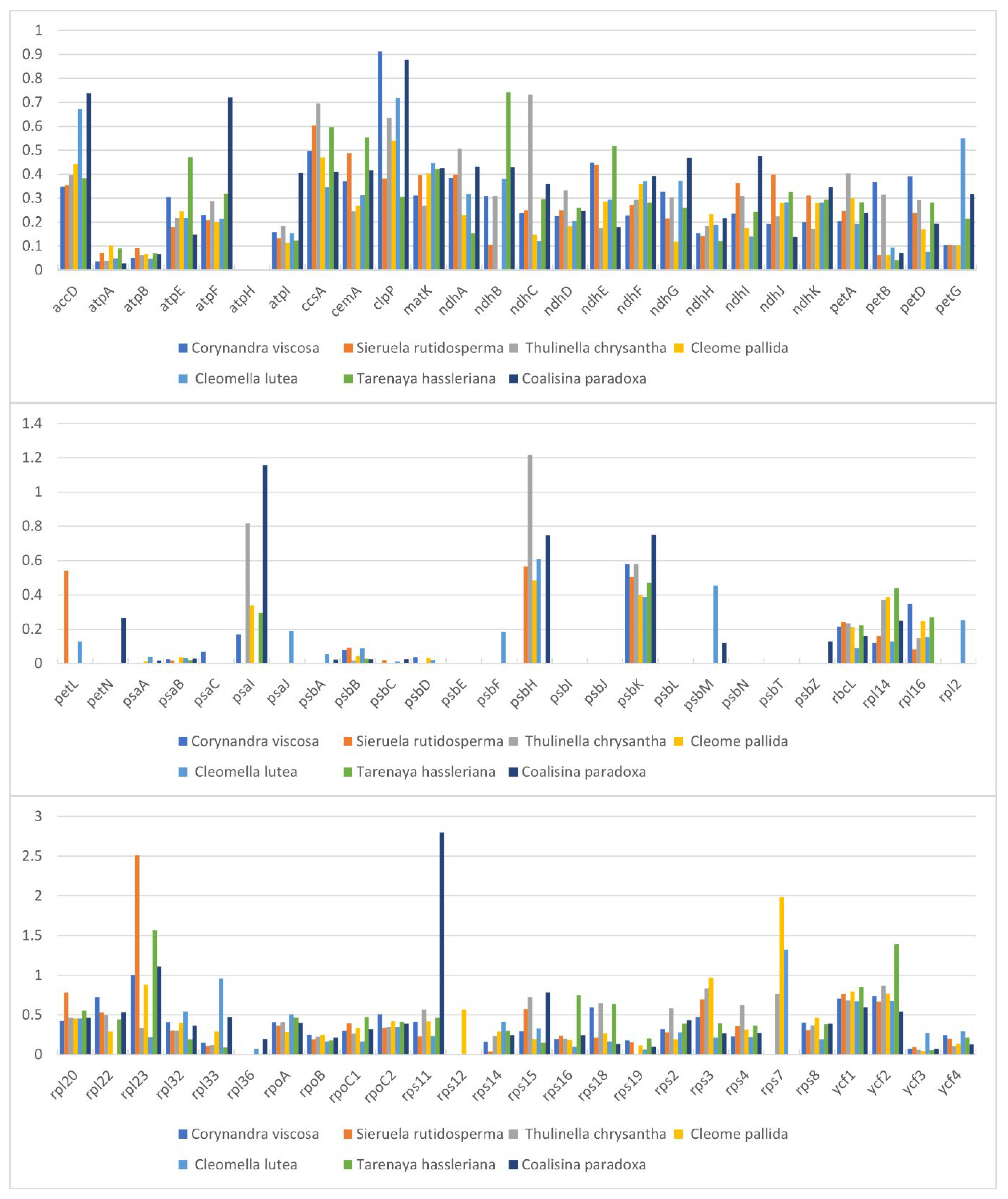

2.5. Comparative Genomic Analysis

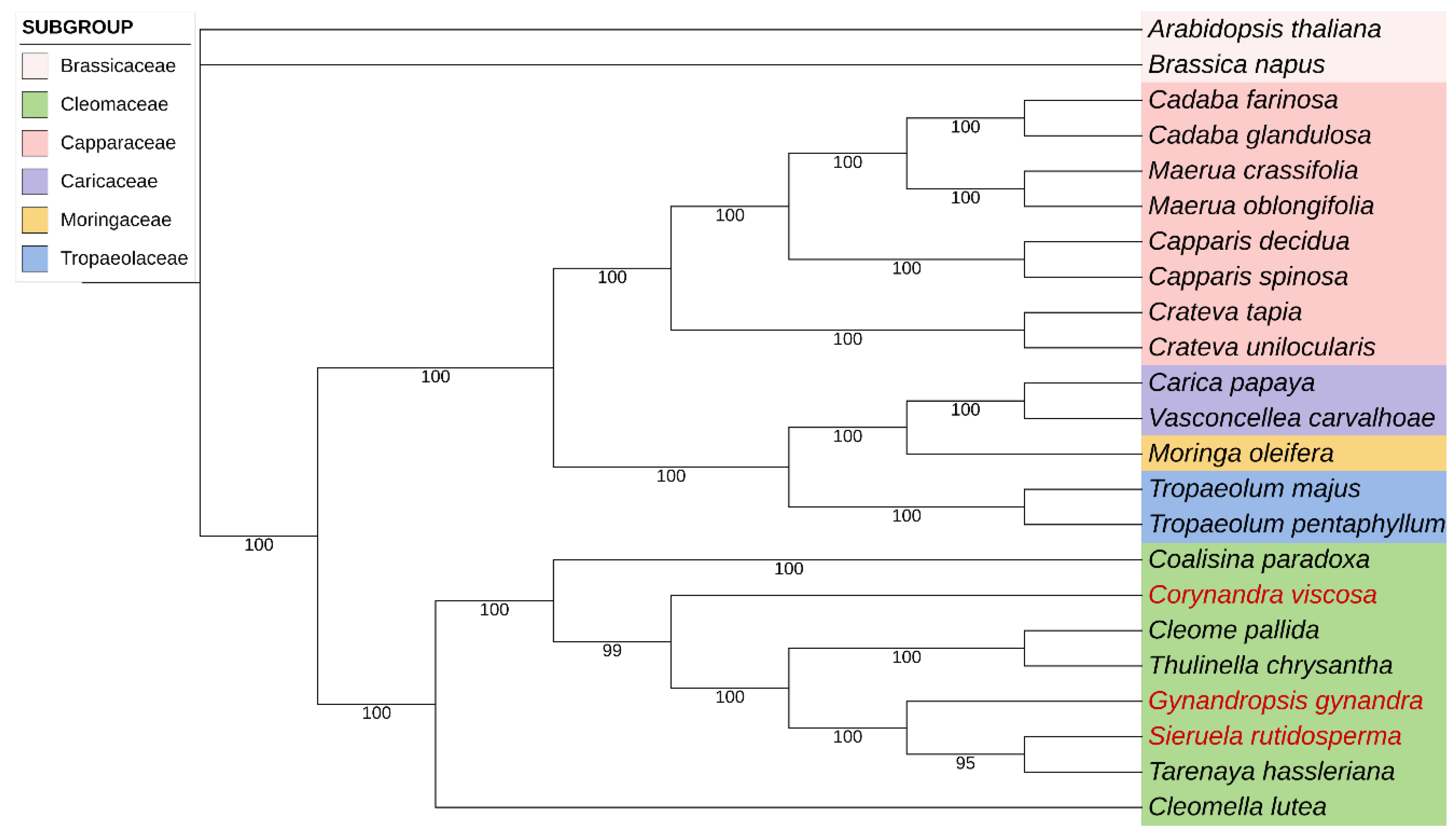

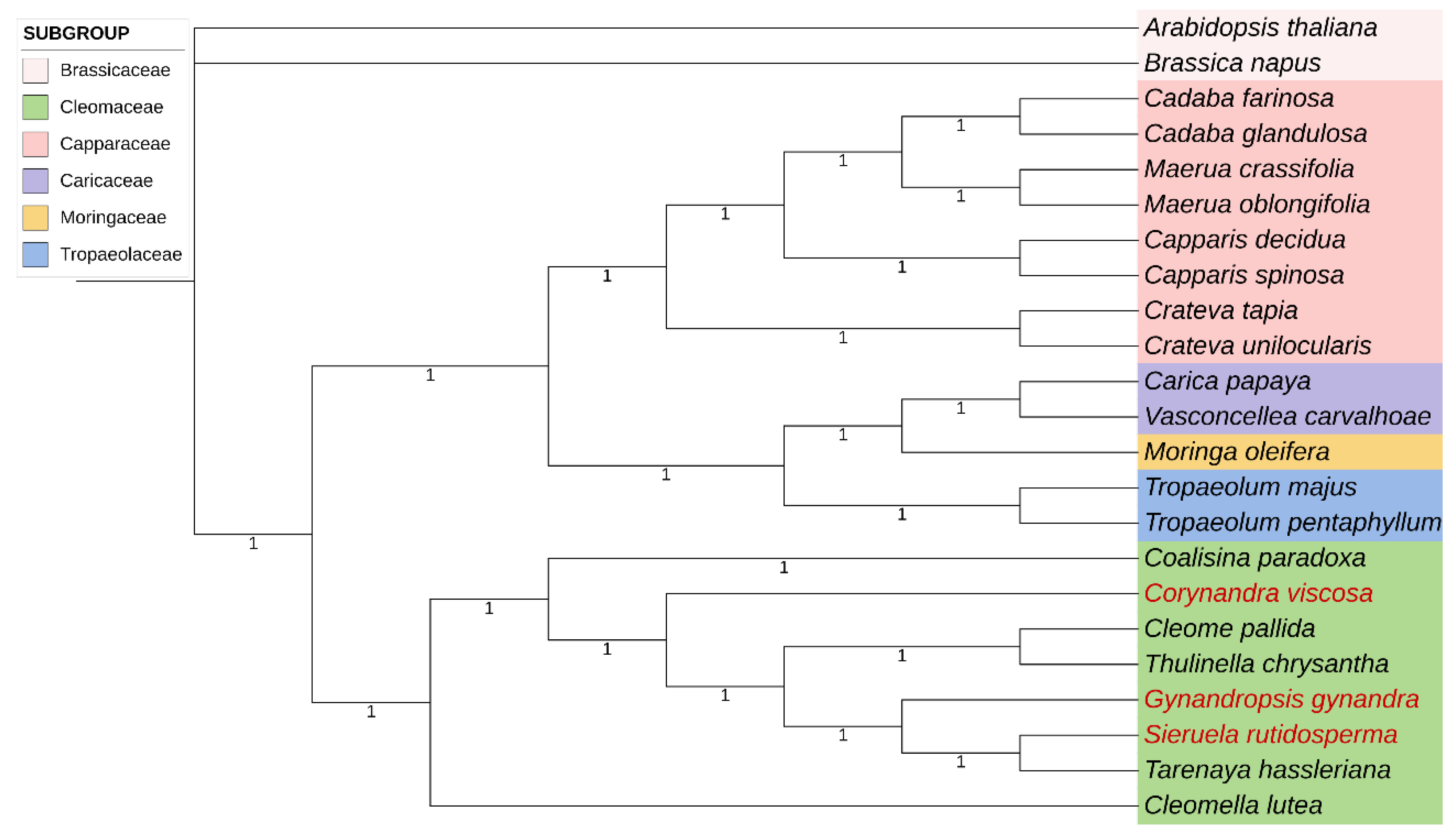

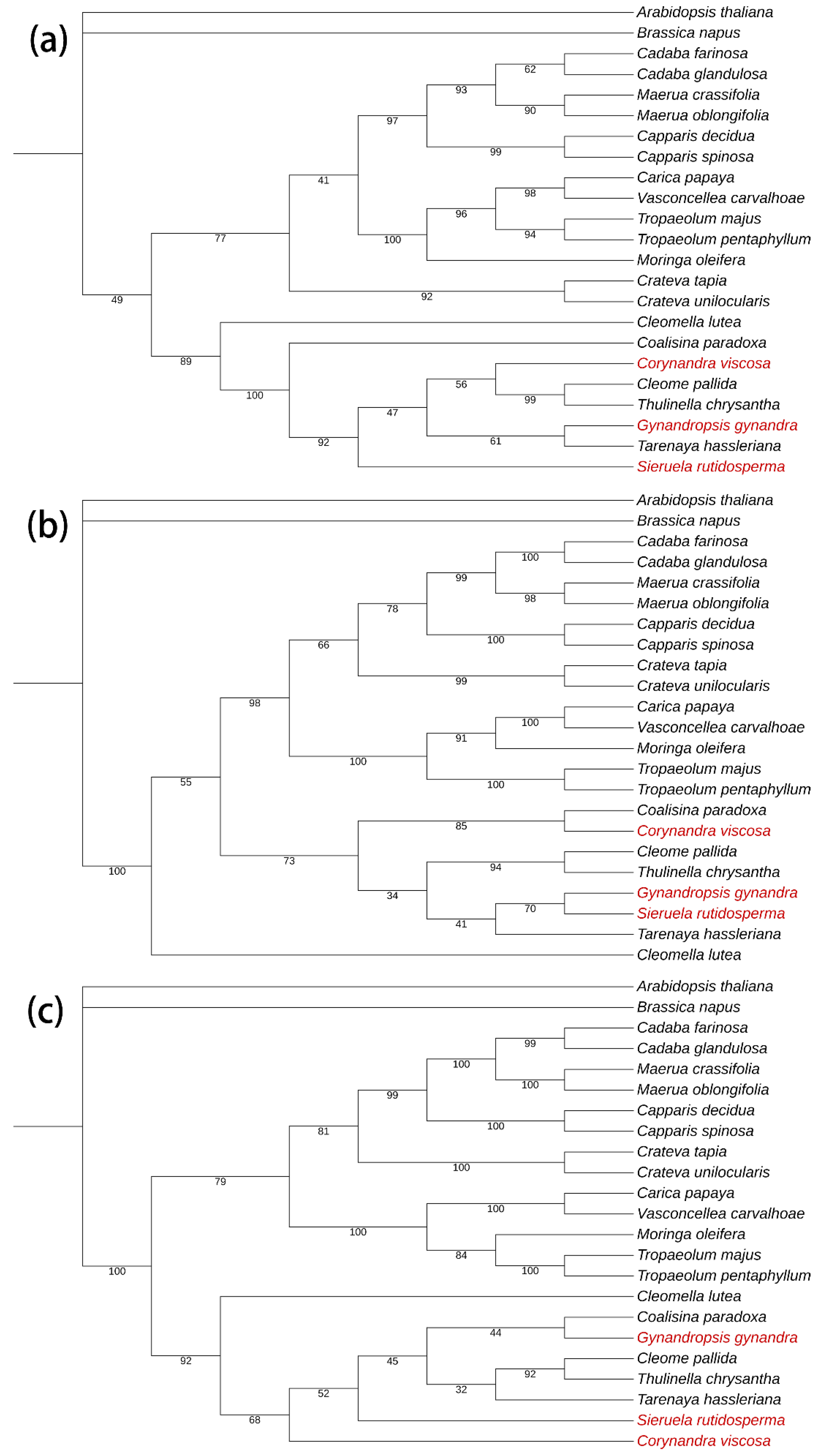

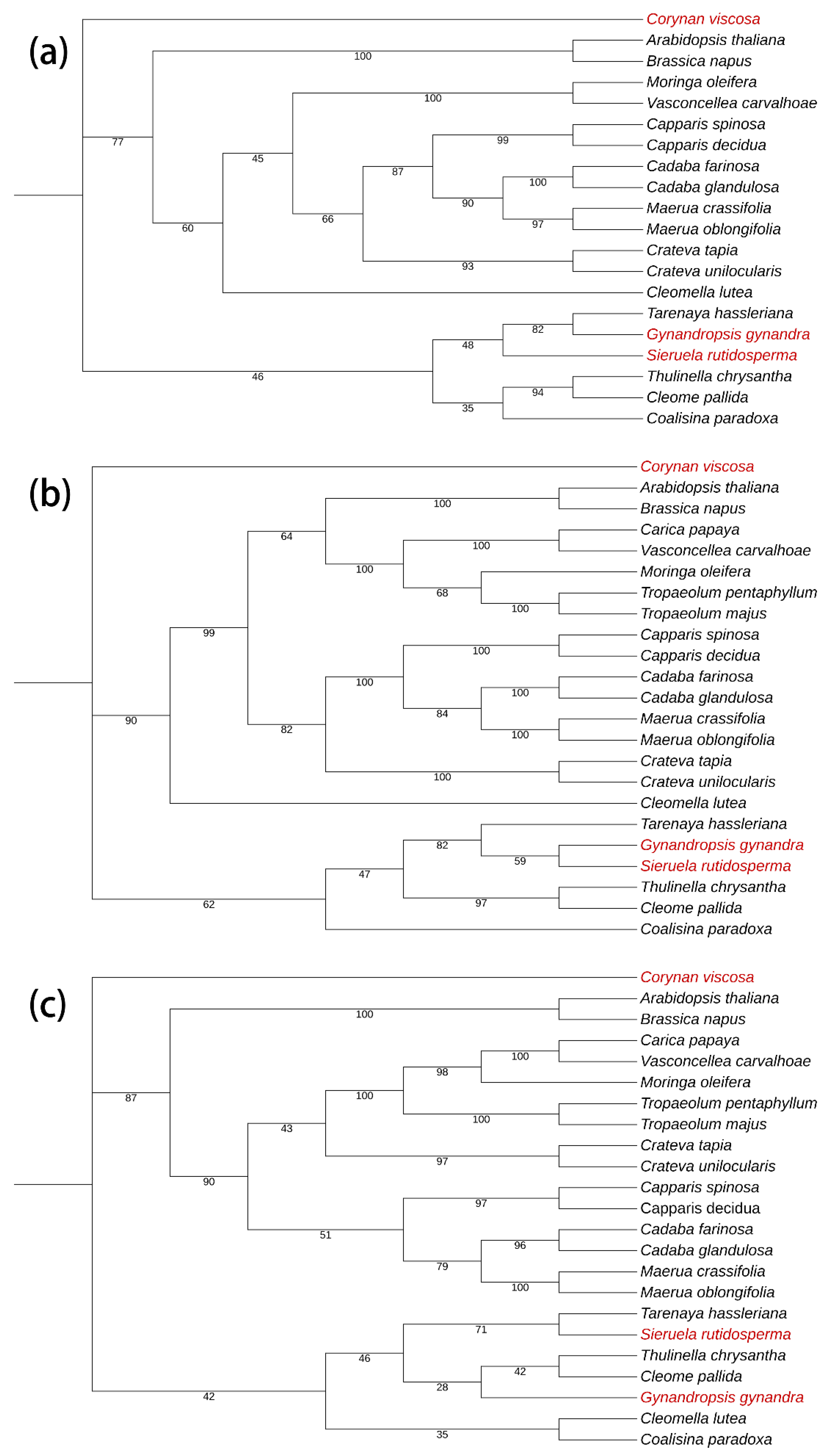

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, DNA Extraction, and Genome Sequencing

4.2. Chloroplast Genome Assembly And Annotation

4.3. Chloroplast Genome Comparison and IR Boundary Analysis

4.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patchell, M.J.; Roalson, E.H.; Hall, J.C. Resolved Phylogeny of Cleomaceae Based on All Three Genomes. Taxon 2014, 63, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozzolillo, C.; Amiguet, V.T.; Bily, A.C.; Harris, C.S.; Saleem, A.; Andersen, Ø.M.; Jordheim, M. Novel Aspects of the Flowers and Floral Pigmentation of Two Cleome Species (Cleomaceae), C. hassleriana and C. serrulata. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchell, M.J.; Bolton, M.C.; Mankowski, P.; Hall, J.C. Comparative Floral Development in Cleomaceae Reveals Two Distinct Pathways Leading to Monosymmetry. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2011, 172, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feodorova, T.A.; Voznesenskaya, E.V.; Edwards, G.E.; Roalson, E.H. Biogeographic Patterns of Diversification and the Origins of C4 in Cleome (Cleomaceae). Syst. Bot. 2010, 35, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.F.; Liu, W.Y.; Lu, M.Y.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Ku, M.S.B.; Li, W.H. Whole-Genome Duplication Facilitated the Evolution of C4 Photosynthesis in Gynandropsis gynandra. Mol. Bio.l Evol. 2021, 38, 4715–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; van den Bergh, E.; Zeng, P.; Zhong, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Hofberger, J.; de Bruijn, S.; Bhide, A.S.; Kuelahoglu, C.; et al. The Tarenaya hassleriana Genome Provides Insight into Reproductive Trait and Genome Evolution of Crucifers. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2813–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, J.; Panda, S.R.; Jain, S.; Murty, U.; Das, A.M.; Kumar, G.J.; Naidu, V. Phytochemistry and Polypharmacology of Cleome Species: A Comprehensive Ethnopharmacological Review of the Medicinal Plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 282, 114600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogbohossou, E.; Achigan-Dako, E.G.; Maundu, P.; Solberg, S.; Deguenon, E.; Mumm, R.H.; Hale, I.; Van Deynze, A.; Schranz, M.E. A Roadmap for Breeding Orphan Leafy Vegetable Species: A Case Study of Gynandropsis gynandra (Cleomaceae). Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Park, S. The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Aster spathulifolius (Asteraceae); Genomic Features and Relationship with Asteraceae. Gene 2015, 572, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Nie, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Song, J.; Yao, H. Comparative and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Paeonia Section Moutan Species (Paeoniaceae). Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Ma, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, Q. Integrated Analysis of Three Newly Sequenced Fern Chloroplast Genomes: Genome Structure and Comparative Analysis. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 4550–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yang, G.; Peng, J.; Peng, X. Initial Characterization of the Chloroplast Genome of Vicia sepium, an Important Wild Resource Plant, and Related Inferences About Its Evolution. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Huang, W.; Sun, H.; Yer, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, B.; Wang, Q.; Wen, Y.; Huang, M.; et al. Comparative Chloroplast Genome Analysis of Impatiens Species (Balsaminaceae) in the Karst Area of China: Insights into Genome Evolution and Phylogenomic Implications. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qi, J.; Zhang, L. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Hibiscus cannabinus and Comparative Analysis of the Malvaceae Family. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, E.I.; Putintseva, Y.A.; Oreshkova, N.V.; Krutovsky, K.V. Siberian Larch (Larix Sibirica Ledeb.) Chloroplast Genome and Development of Polymorphic Chloroplast Markers. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashnow, H.; Tan, S.; Das, D.; Easteal, S.; Oshlack, A. Genotyping Microsatellites in Next-Generation Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2015, 16, A5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucom, R.S.; Estill, J.C.; Leebens-Mack, J.; Bennetzen, J.L. Natural Selection on Gene Function Drives the Evolution of LTR Retrotransposon Families in the Rice Genome. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, A.H.; Bowers, J.E.; Bruggmann, R.; Dubchak, I.; Grimwood, J.; Gundlach, H.; Haberer, G.; Hellsten, U.; Mitros, T.; Poliakov, A.; et al. The Sorghum Bicolor Genome and the Diversification of Grasses. Nature 2009, 457, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SanMiguel, P.; Gaut, B.S.; Tikhonov, A.; Nakajima, Y.; Bennetzen, J.L. The Paleontology of Intergene Retrotransposons of Maize. Nat. Genet. 1998, 20, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnable, P.S.; Ware, D.; Fulton, R.S.; Stein, J.C.; Wei, F.; Pasternak, S.; Liang, C.; Zhang, J.; Fulton, L.; Graves, T.A.; et al. The B73 Maize Genome: Complexity, Diversity, and Dynamics. Science 2009, 326, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgante, M.; De Paoli, E.; Radovic, S. Transposable Elements and the Plant Pan-Genomes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Boo, H.O.; Ahn, T.; Bae, C.S. Protective Effects of Erythronium Japonicum and Corylopsis coreana Uyeki Extracts against 1, 3-Dichloro-2-Propanol-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Rats. Appl. Microsc. 2020, 50, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, G.; Ma, Q.; Ma, W.; Liang, L.; Zhao, T. The Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Betulaceae Species: Implications for Molecular Phylogeny and Historical Biogeography. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, B. The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Altingia chinensis (Hamamelidaceae). Mitochondr. DNA B. 2020, 5, 1808–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, E.; Külahoglu, C.; Bräutigam, A.; Hibberd, J.M.; Weber, A.P.; Zhu, X.G.; Schranz, M.E. Gene and Genome Duplications and the Origin of C4 Photosynthesis: Birth of a Trait in the Cleomaceae. Curr. Plant Biol. 2014, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, M.D.; Oggero, A.J. New Combinations in Tarenaya (Cleomaceae) for the Argentinian Flora. Phytotaxa 2016, 267, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami-Farouji, A.; Khosravi, A.R.; Çetin, Ö.; Mohsenzadeh, S. Unmasking the Phylogenetic Topology of Southwest Asian Cleomes (Cleomaceae) as a Precursor to Taxonomic Delimitation: Insights into Main Lineages and Important Morphological Characteristics. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 68, 2655–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zayat, M.A.S.; Ali, M.E.S.; Amar, M.H. A Systematic Revision of Capparaceae and Cleomaceae in Egypt: An Evaluation of the Generic Delimitations of Capparis and Cleome Using Ecological and Genetic Diversity. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2020, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iltis, H.H.; Cochrane, T.S. Studies in the Cleomaceae V: A New Genus and Ten New Combinations for the Flora of North America. Novon 2007, 17, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, S.; Schranz, M.E.; Roalson, E.H.; Hall, J.C. Lessons from Cleomaceae, the sister of crucifers. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Neto, R.L.; Thomas, W.W.; de Vasconcellos Barbosa, M.R.; Roalson, E.H. Diversification of New World Cleomaceae with Emphasis on Tarenaya and the Description of Iltisiella, a New Genus. Taxon 2020, 69, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, I.A.; Bakir, M.A.; Khan, H.A.; Al Farhan, A.H.; Al Homaidan, A.A.; Bahkali, A.H.; Al Sadoon, M.; Shobrak, M. A Brief Review of Molecular Techniques to Assess Plant Diversity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2079–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Xia, T.; Zhou, S. DNA barcoding: species delimitation in tree peonies. Sci. China C. Life Sci. 2009, 52, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.S.; Yang, J.Y.; Yang, T.J.; Kim, S.C. Evolutionary comparison of the chloroplast genome in the Woody Sonchus Alliance (Asteraceae) on the Canary Islands. Genes 2019, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.H.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.X.; Nie, L.P.; Lin, Y.L.; Wei, X.P.; Wang, Y.; Yao, H. Molecular structure and phylogenetic analyses of the complete chloroplast genomes of three original species of Pyrrosiae Folium. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, B.F.; Murphy, D.J.; Walsh, N.G.; Conran, J.G.; Pires, J.C.; Macfarlane, T.D.; Crisp, M.D.; Cook, L.G.; Birch, J.L. Genomic Data Resolve Phylogenetic Relationships of Australian Mat-Rushes, Lomandra (Asparagaceae: Lomandroideae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2024, 204, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xiong, Y.; He, J.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Lei, X.; Dong, Z.; Yang, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X. The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Two Important Annual Clover Species, Trifolium alexandrinum and T. resupinatum: Genome Structure, Comparative Analyses and Phylogenetic Relationships with Relatives in Leguminosae. Plants 2020, 9, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocelyn, C. H. Systematics of Capparaceae and Cleomaceae: an evaluation of the generic delimitations of Capparis and Cleome using plastid DNA sequence data. Botany 2008, 86, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Nie, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Song, J.; Yao, H. Comparative and Phylogenetic Analyses of the Chloroplast Genomes of Species of Paeoniaceae. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Ma, Q.; Liang, L.; Wang, G. Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetic Analysis Revealed the Chloroplast Genome Variation and Interspecific Relationships of Corylus (Betulaceae) Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Khan, A.L.; Khan, M.A.; Shahzad, R.; Lubna; Kang, S.M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Lee, I.J. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Comparative Analysis of Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda L.) with Related Species. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, M.T.; Gaut, B.S.; Learn Jr, G.H.; Morton, B.R. Rates and Patterns of Chloroplast DNA Evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91, 6795–6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chang, E.M.; Liu, J.F.; Huang, Y.N.; Wang, Y.; Yao, N.; Jiang, Z.P. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of Quercus bawanglingensis Huang, Li et Xing, a Vulnerable Oak Tree in China. Forests. 2019, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, M.C.; Cardoni, S.; Piredda, R.; Imperatori, F.; Avishai, M.; Grimm, G.W.; Denk, T. Comparative Systematics and Phylogeography of Quercus Section Cerris in Western Eurasia: Inferences from Plastid and Nuclear DNA Variation. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Ma, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, Q. Integrated analysis of three newly sequenced fern chloroplast genomes: Genome structure and comparative analysis. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 4550–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Bao, G.; Ao, W.; Kang, T. Characteristic and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Medicinal Plants of Schisandraceae. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3536761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, F.; Jakovlić, I.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.X.; Wang, G.T. PhyloSuite: An Integrated and Scalable Desktop Platform for Streamlined Molecular Sequence Data Management and Evolutionary Phylogenetics Studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lan, L.; He, H.; Chen, Z.; She, S.; Liu, Y.; Lü, B. Progress in the Studies of ClpP: From Bacteria to Human Mitochondria. Chin. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 36, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Guo, L.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, X.; Wu, M.; Hou, X. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of Paeonia ostii. Molecules 2018, 23, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naver, H.; Boudreau, E.; Rochaix, J.D. Functional Studies of Ycf3: Its Role in Assembly of Photosystem I and Interactions with Some of Its Subunits. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2731–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Khan, A.L.; Khan, M.A.; Waqas, M.; Kang, S.M.; Yun, B.W.; Lee, I.J. Chloroplast Genomes of Arabidopsis halleri ssp. gemmifera and Arabidopsis lyrata Ssp. Petraea: Structures and Comparative Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhunov, E.D.; Akhunova, A.R.; Anderson, O.D.; Anderson, J.A.; Blake, N.; Clegg, M.T.; Coleman-Derr, D.; Conley, E.J.; Crossman, C.C.; Deal, K.R.; et al. Nucleotide Diversity Maps Reveal Variation in Diversity among Wheat Genomes and Chromosomes. BMC Genomics 2010, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakhlova, O.; Bock, R. Elimination of Deleterious Mutations in Plastid Genomes by Gene Conversion. Plant J. 2006, 46, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Lickey, E.B.; Schilling, E.E.; Small, R.L. Comparison of Whole Chloroplast Genome Sequences to Choose Noncoding Regions for Phylogenetic Studies in Angiosperms: The Tortoise and the Hare III. Am. J. Bot. 2007, 94, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, P.M.; Forrest, L.L.; Spouge, J.L.; Hajibabaei, M.; Ratnasingham, S.; van der Bank, M.; Chase, M.W.; Cowan, R.S.; Erickson, D.L. ; others A DNA Barcode for Land Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 12794–12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Vázquez, L.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, G. Development of Chloroplast and Nuclear DNA Markers for Chinese Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus) and Assessment of Their Utility as DNA Barcodes. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lv, J.; Xu, J.; Zhu, S.; Li, M.; Chen, N. Development of chloroplast genomic resources for Oryza species discrimination. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, K.; Nobis, M.; Myszczyński, K.; Klichowska, E.; Sawicki, J. Plastid Super-Barcodes as a Tool for Species Discrimination in Feather Grasses (Poaceae: Stipa). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Lin, B.Y.; Lin, J.Y.; Wu, W.L.; Chang, C.C. Evaluation of Chloroplast DNA Markers for Intraspecific Identification of Phalaenopsis equestris Cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 203, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmueller, K.E.; Albrechtsen, A.; Li, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Korneliussen, T.; Vinckenbosch, N.; Tian, G.; Huerta-Sanchez, E.; Feder, A.F.; Grarup, N.; et al. Natural Selection Affects Multiple Aspects of Genetic Variation at Putatively Neutral Sites across the Human Genome. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrutenko, A.; Makova, K.D.; Li, W.H. The K(A)/K(S) Ratio Test for Assessing the Protein-Coding Potential of Genomic Regions: An Empirical and Simulation Study. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Huang, S.; Yu, J. (2011). Nonsynonymous substitution rate (Ka) is a relatively consistent parameter for defining fast-evolving and slow-evolving protein-coding genes. Biol. Direct 2011, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makałowski, W.; Boguski, M.S. Evolutionary Parameters of the Transcribed Mammalian Genome: An Analysis of 2,820 Orthologous Rodent and Human Sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 9407–9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drescher, A.; Ruf, S.; Calsa Jr, T.; Carrer, H.; Bock, R. The Two Largest Chloroplast Genome-Encoded Open Reading Frames of Higher Plants Are Essential Genes. Plant J. 2000, 22, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicke, S.; Schneeweiss, G.M.; Depamphilis, C.W.; Müller, K.F.; Quandt, D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 76, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Acebo, L. A Phylogenetic Study of the New World Cleome (Brassicaceae, Cleomoideae). Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2005, 92, 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Inda, L.A.; Torrecilla, P.; Catalán, P.; Ruiz-Zapata, T. Phylogeny of Cleome L. and Its Close Relatives Podandrogyne Ducke and Polanisia Raf. (Cleomoideae, Cleomaceae) Based on Analysis of Nuclear ITS Sequences and Morphology. Plant Syst. Evol. 2008, 274, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.C.; Sytsma, K.J.; Iltis, H.H. Phylogeny of Capparaceae and Brassicaceae Based on Chloroplast Sequence Data. Am. J. Bot. 2002, 89, 1826–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilla, O.; Dinssa, F.F.; Omondi, E.O.; Winkelmann, T.; Abukutsa-Onyango, M. Cleome gynandra L. origin, taxonomy and morphology: A review. Asian. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 14, 1568–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feodorova, T.A.; Voznesenskaya, E.V.; Edwards, G.E.; Roalson, E.H. Biogeographic Patterns of Diversification and the Origins of C4 in Cleome (Cleomaceae). Syst. Bot. 2010, 35, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamboli, A.S.; Patil, S.M.; Gholave, A.R.; Kadam, S.K.; Kotibhaskar, S.V.; Yadav, S.R.; Govindwar, S.P. Phylogenetic analysis, genetic diversity and relationships between the recently segregated species of Corynandra and Cleoserrata from the genus Cleome using DNA barcoding and molecular markers. C. R. Biol. 2016, 339, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvreur, T.L.; Franzke, A.; Al-Shehbaz, I.A.; Bakker, F.T.; Koch, M.A.; Mummenhoff, K. Molecular Phylogenetics, Temporal Diversification, and Principles of Evolution in the Mustard Family (Brassicaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, D.; Albokhari, E.; Yaradua, S.; Abba, A. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequences of Dipterygium glaucum and Cleome chrysantha and Other Cleomaceae Species, Comparative Analysis and Phylogenetic Relationships. Saudi, J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2476–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboul-Maaty, N.A.-F.; Oraby, H.A.S. Extraction of High-Quality Genomic DNA from Different Plant Orders Applying a Modified CTAB-Based Method. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; Pyshkin, A.V.; Sirotkin, A.V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G.; Alekseyev, M.A.; Pevzner, P.A. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acemel, R.D.; Tena, J.J.; Irastorza-Azcarate, I.; Marlétaz, F.; GómezMarín, C.; de la Calle-Mustienes, E.; Bertrand, S.; Diaz, S.G. , Aldea, D.; Aury, J.-M.; Mangenot, S.; Hol-land, P.W.H.; Devos, D.P.; Maeso, I., Escrivá, H.; Gómez-Skarmeta, J.L. A single three-dimensional chromatin compartment in amphioxus indicates a step-wise evolution of vertebrate Hox bimodal regulation. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boetzer, M.; Pirovano, W. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, M.; Drechsel, O.; Bock, R. Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW): A tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr. Genet. 2007, 52, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, C.; Brudno, M.; Schwartz, J.R.; Poliakov, A.; Rubin, E.M.; Frazer, K.A.; Pachter, L.S.; Dubchak, I. VISTA: Visualizing Global DNA Sequence Alignments of Arbitrary Length. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 1046–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.A.; Pachter, L.; Poliakov, A.; Rubin, E.M.; Dubchak, I. VISTA: Computational Tools for Comparative Genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W273–W279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kode, V.; Mudd, E.A.; Iamtham, S.; Day, A. The Tobacco Plastid accD Gene Is Essential and Is Required for Leaf Development. Plant J. 2005, 44, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubeson, L.A.; Peery, R.; Chumley, T.W.; Dziubek, C.; Fourcade, H.M.; Boore, J.L.; Jansen, R.K. Comparative Chloroplast Genomics: Analyses Including New Sequences from the Angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genomics 2007, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Tang, P.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H. The First Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequences in Actinidiaceae: Genome Structure and Comparative Analysis. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0129347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.C.; Mau, B.; Blattner, F.R.; Perna, N.T. Mauve: Multiple Alignment of Conserved Genomic Sequence with Rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic Orthology Inference for Comparative Genomics. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC bioinformatics 2009, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genome features | Corynandra viscosa | Sieruela rutidosperma | Gynandropsis gynandra |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total length (bp) | 158,041 | 157,073 | 158,152 |

| LSC length (bp) | 87,178 | 86,422 | 87,242 |

| SSC length (bp) | 18,495 | 18,485 | 18,548 |

| IRa length (bp) | 26,184 | 26,083 | 26,181 |

| IRb length (bp) | 26,184 | 26,083 | 26,181 |

| Genes | 131 | 131 | 132 |

| Protein-coding genes (CDS) | 84 | 84 | 86 |

| tRNA genes | 37 | 37 | 37 |

| rRNA genes | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| pseudo genes | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| GC% | 36.02 | 36.02 | 35.81 |

| total genome | 36.02 | 36.02 | 35.81 |

| LSC | 33.68 | 33.68 | 33.42 |

| SSC | 29.03 | 28.94 | 28.55 |

| IR | 42.38 | 42.43 | 42.36 |

| genes(total/different) | 131 | 131 | 132 |

| CDS(total/different) | 84/79 | 84/78 | 86/79 |

| tRNA(total/different) | 37/28 | 37/30 | 37/30 |

| Species | Region | A (%) | T (%) | C (%) | G (%) | AT (%) | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corynandra viscosa | LSC | 32.35 | 33.98 | 17.33 | 16.35 | 66.32 | 33.68 |

| SSC | 35.23 | 35.74 | 14.98 | 14.05 | 70.97 | 29.03 | |

| IR | 28.81 | 28.81 | 21.19 | 21.19 | 57.62 | 42.38 | |

| Total | 31.51 | 32.47 | 18.34 | 17.68 | 63.98 | 36.02 | |

| Sieruela rutidosperma | LSC | 32.25 | 34.08 | 17.36 | 16.32 | 66.33 | 33.68 |

| SSC | 35.47 | 35.59 | 15.00 | 13.95 | 71.06 | 28.94 | |

| IR | 28.79 | 28.79 | 21.21 | 21.21 | 57.58 | 42.42 | |

| Total | 31.48 | 32.50 | 18.36 | 17.67 | 63.98 | 36.02 | |

| Gynandropsis gynandra | LSC | 32.41 | 34.17 | 17.21 | 16.21 | 66.58 | 33.42 |

| SSC | 35.42 | 36.03 | 14.78 | 13.77 | 71.45 | 28.55 | |

| IR | 28.82 | 28.82 | 21.18 | 21.18 | 57.64 | 42.36 | |

| Total | 31.57 | 32.62 | 18.24 | 17.57 | 64.19 | 35.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).