Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

27 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cosmology

3. Reconstruction of Gravity

3.1. Emergent Cosmological Model

3.2. Intermediate Cosmological Model

3.3. Logamediate Cosmological Model

3.4. Power Law Model

- Case 1: varying k and m with

- Case 2: varying k and m with

- Case 3: varying m and n as negative values

4. Thermodynamics of Gravity

4.1. GSL Using First Law

4.2. GSL without Using the First Law

5. Conclusions

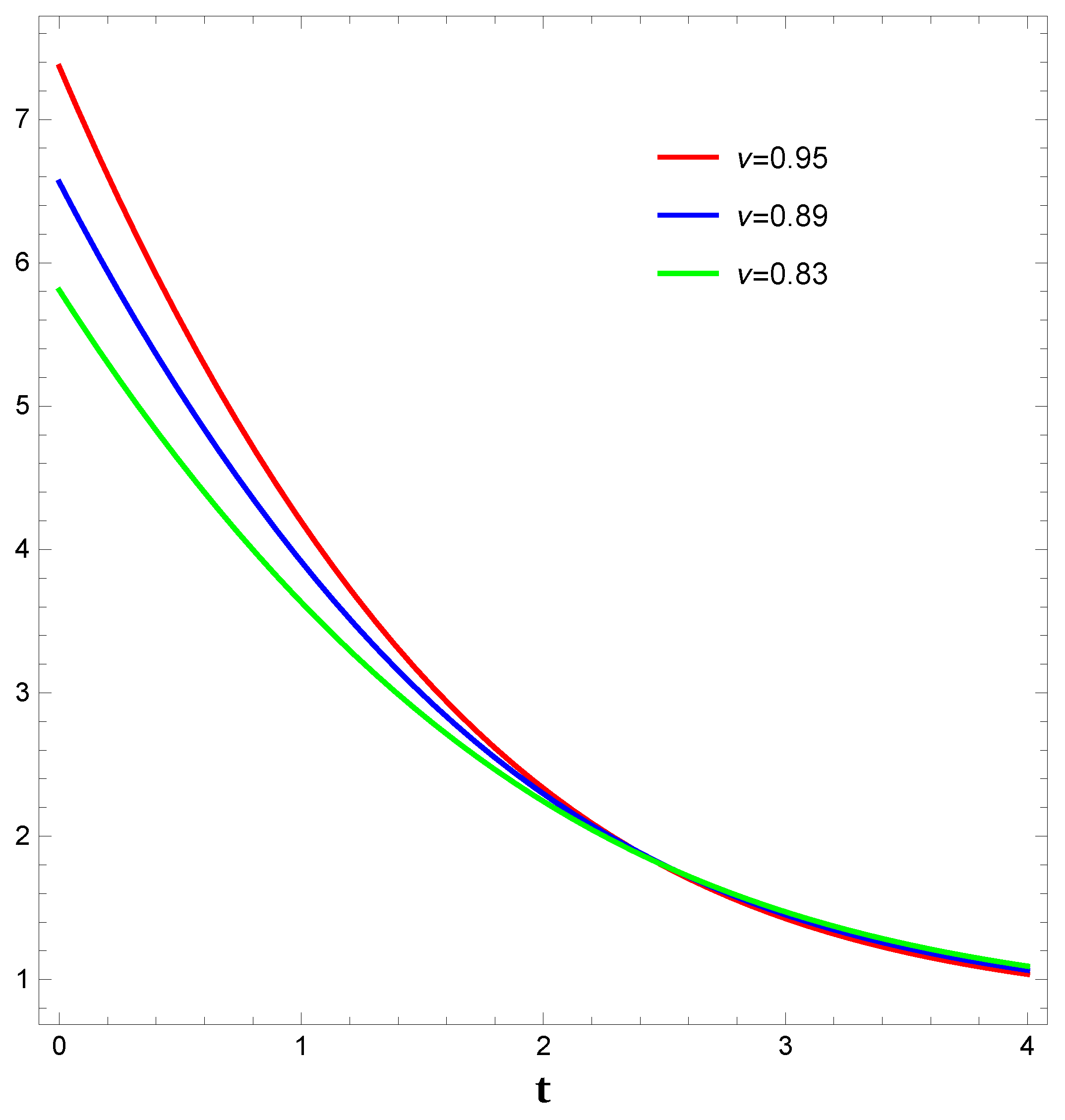

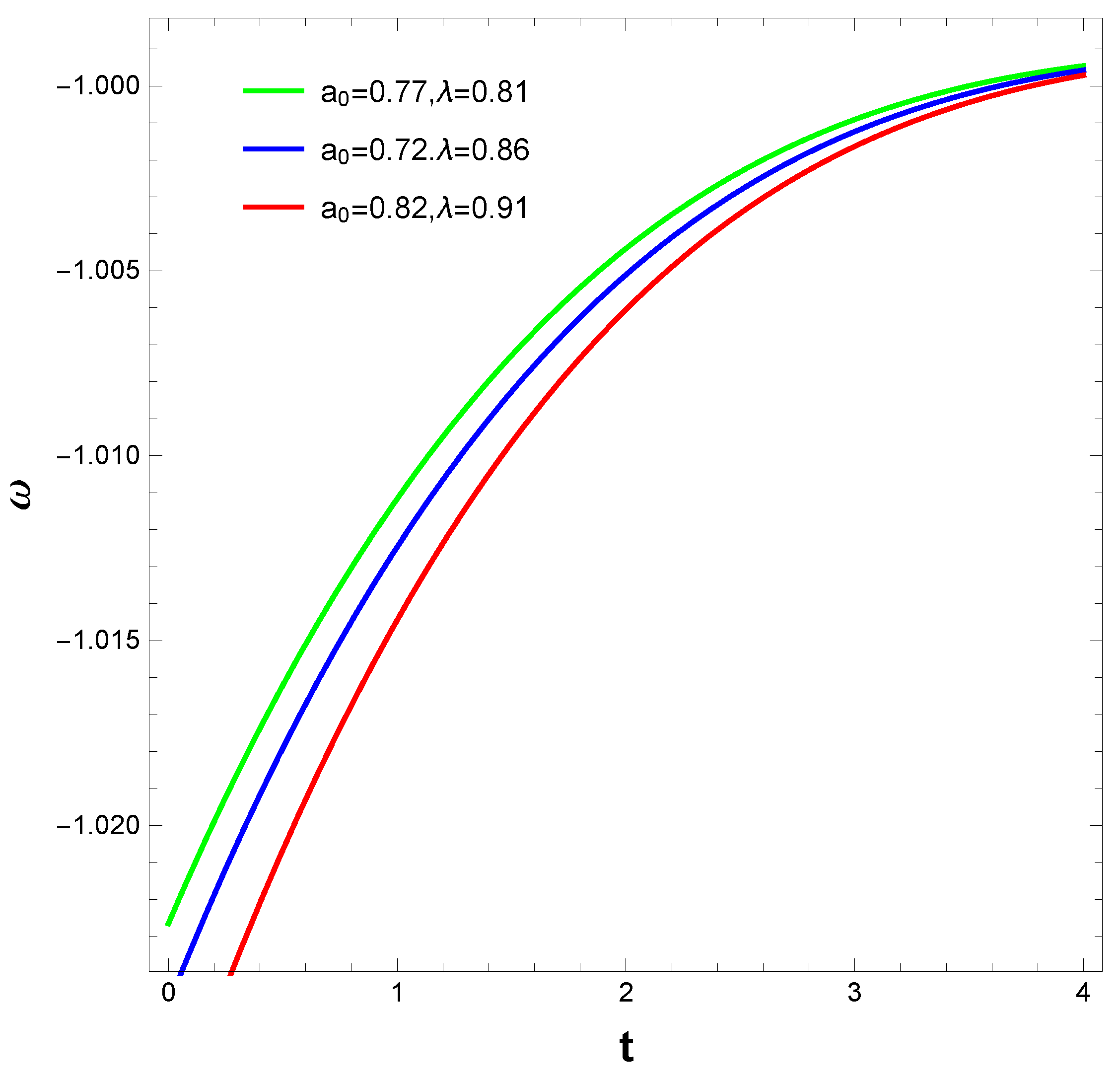

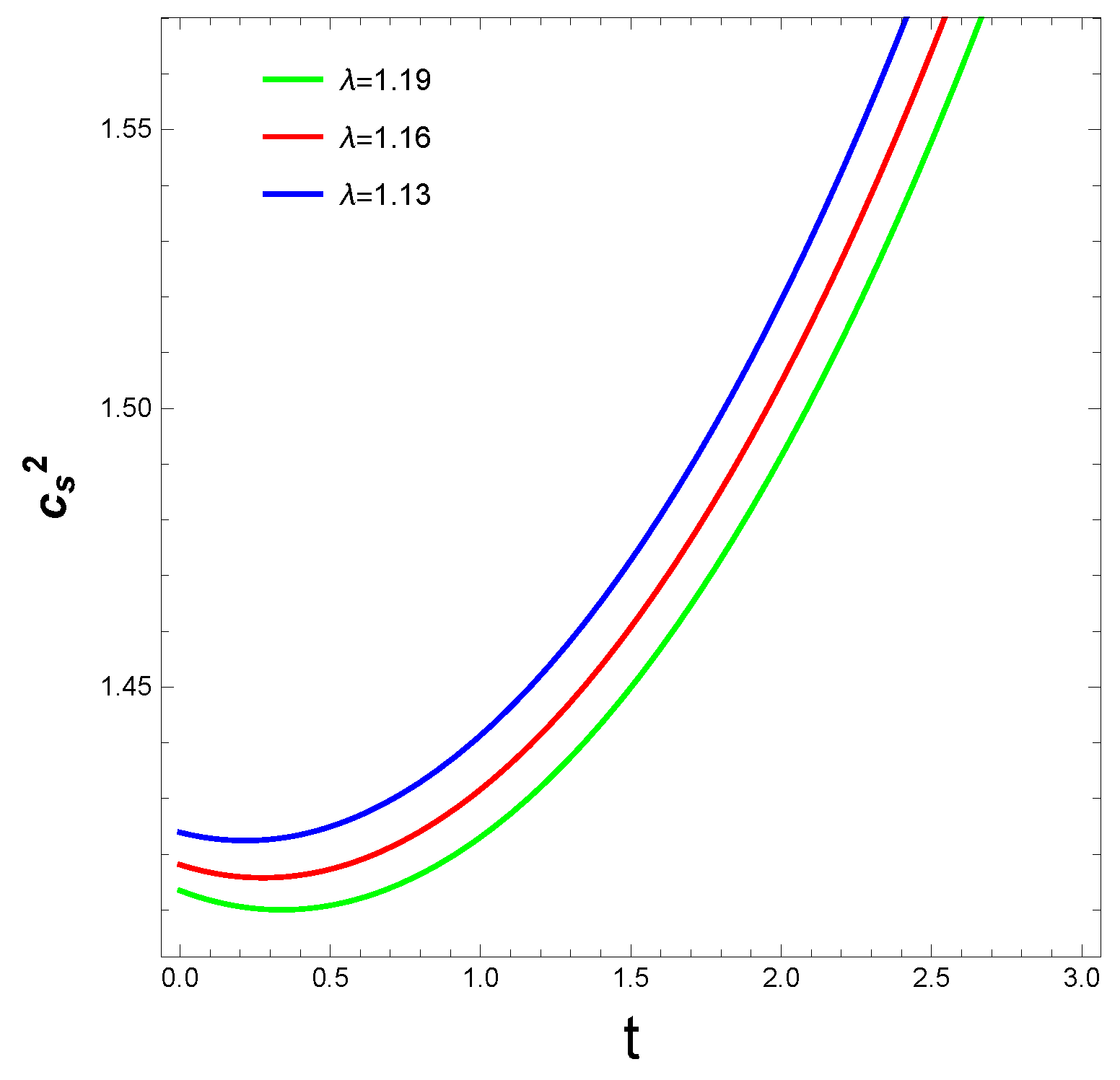

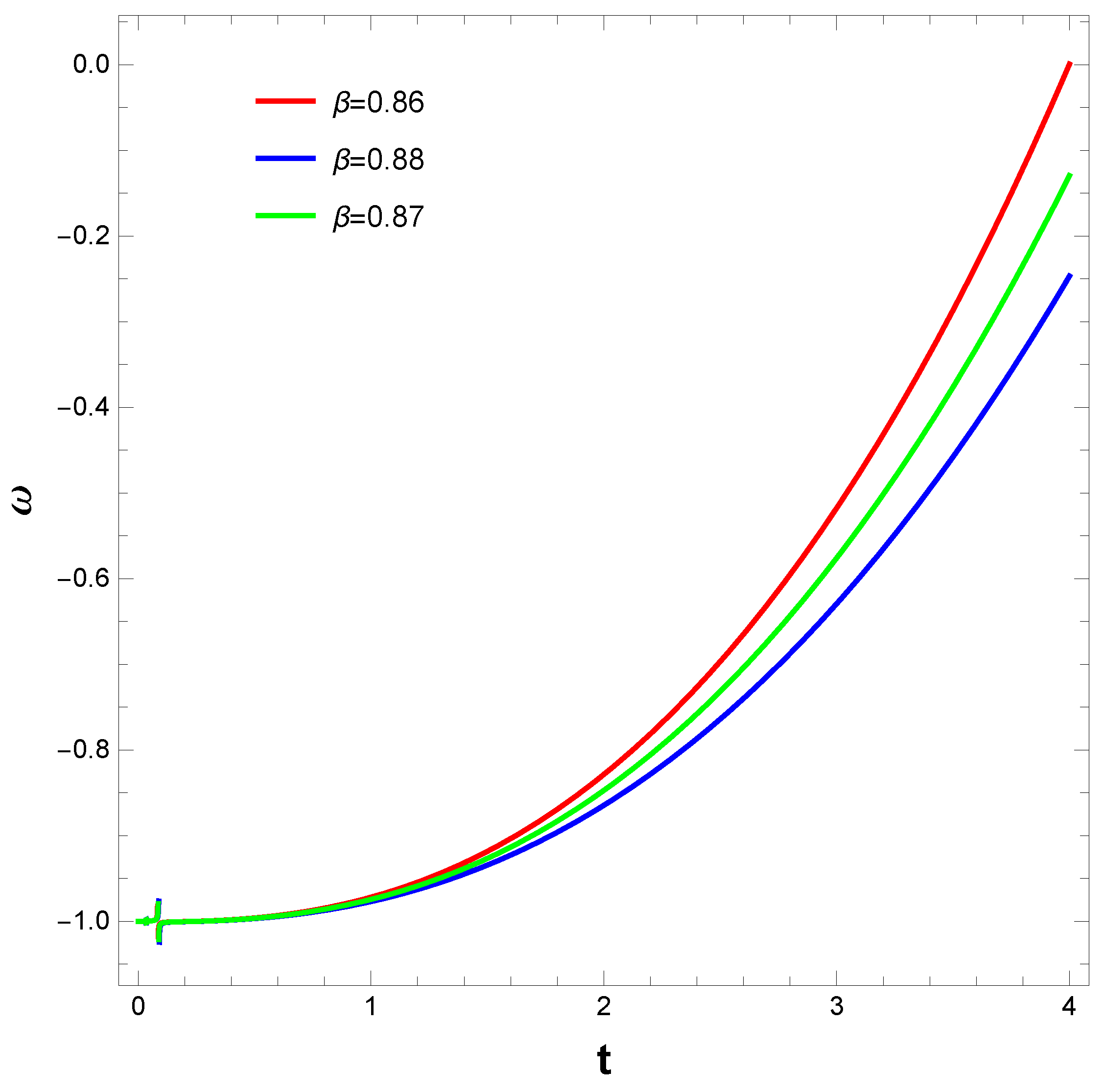

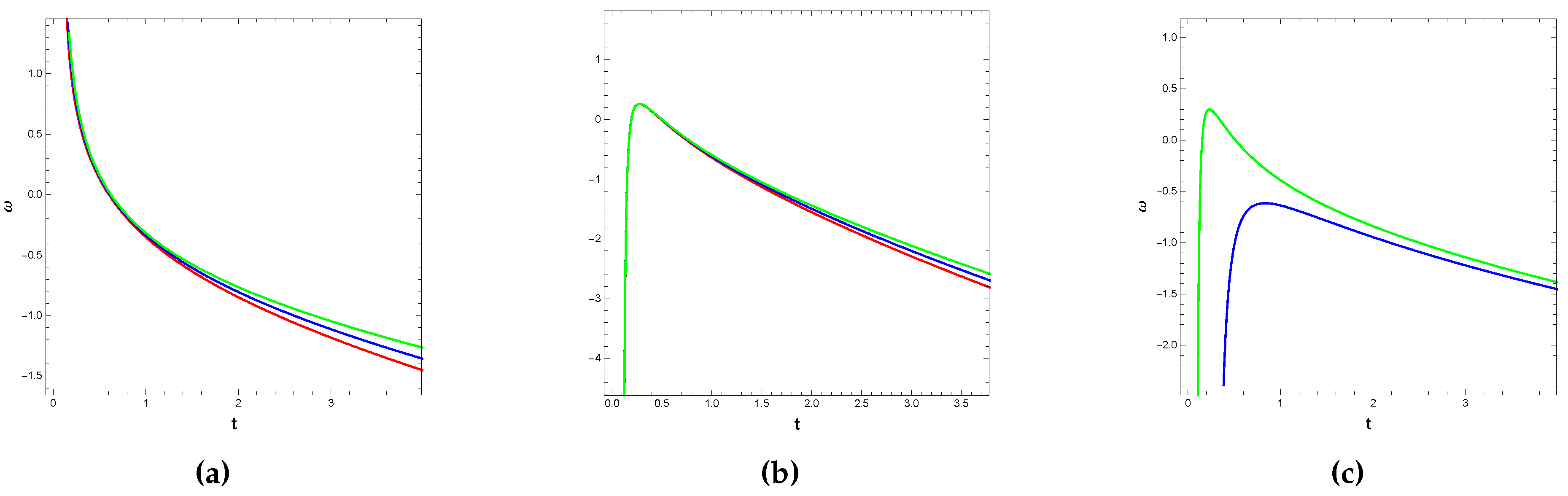

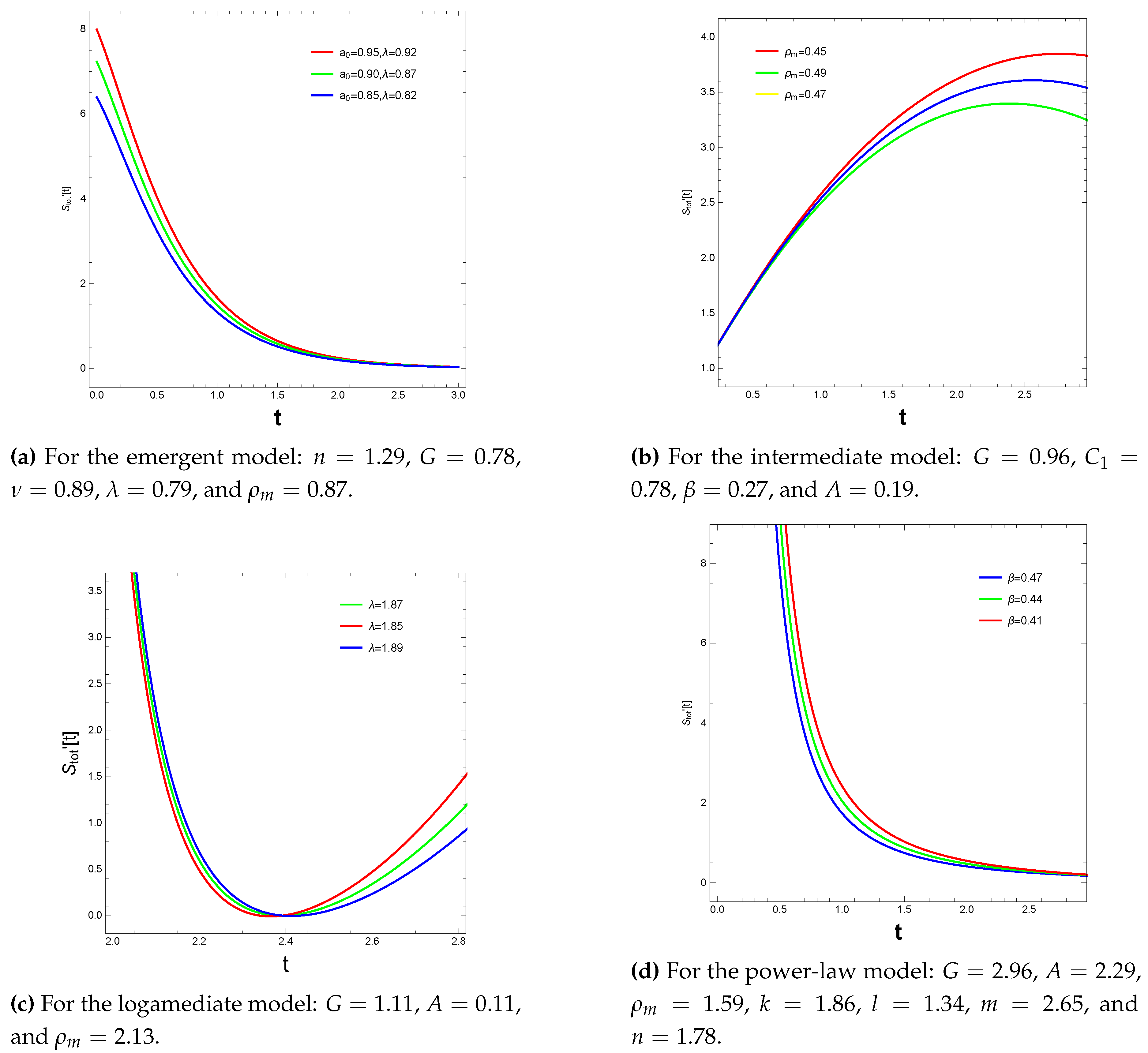

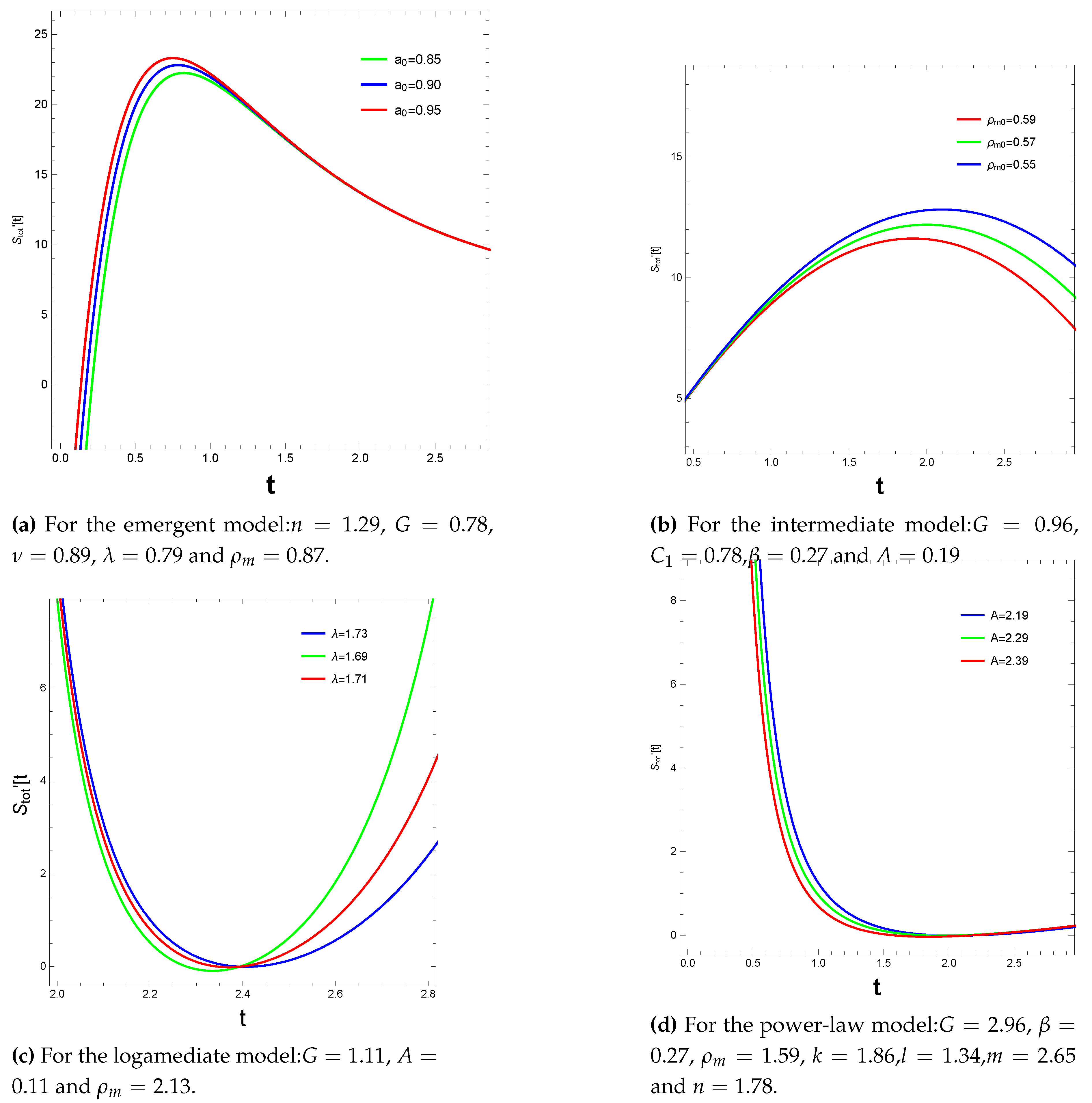

- In the case of the emergent scale factor, we see(cf. Figure 1) that the function is a decreasing function which is asymptotically tending towards 1 with the increase in t. The EoS parameter (see Figure 2) shows a phantom behaviour and tends to with the increase in time t. The squared speed of sound shows a decrease in value with time but stays positive which indicates the stability of the density perturbations and possibly, the model.

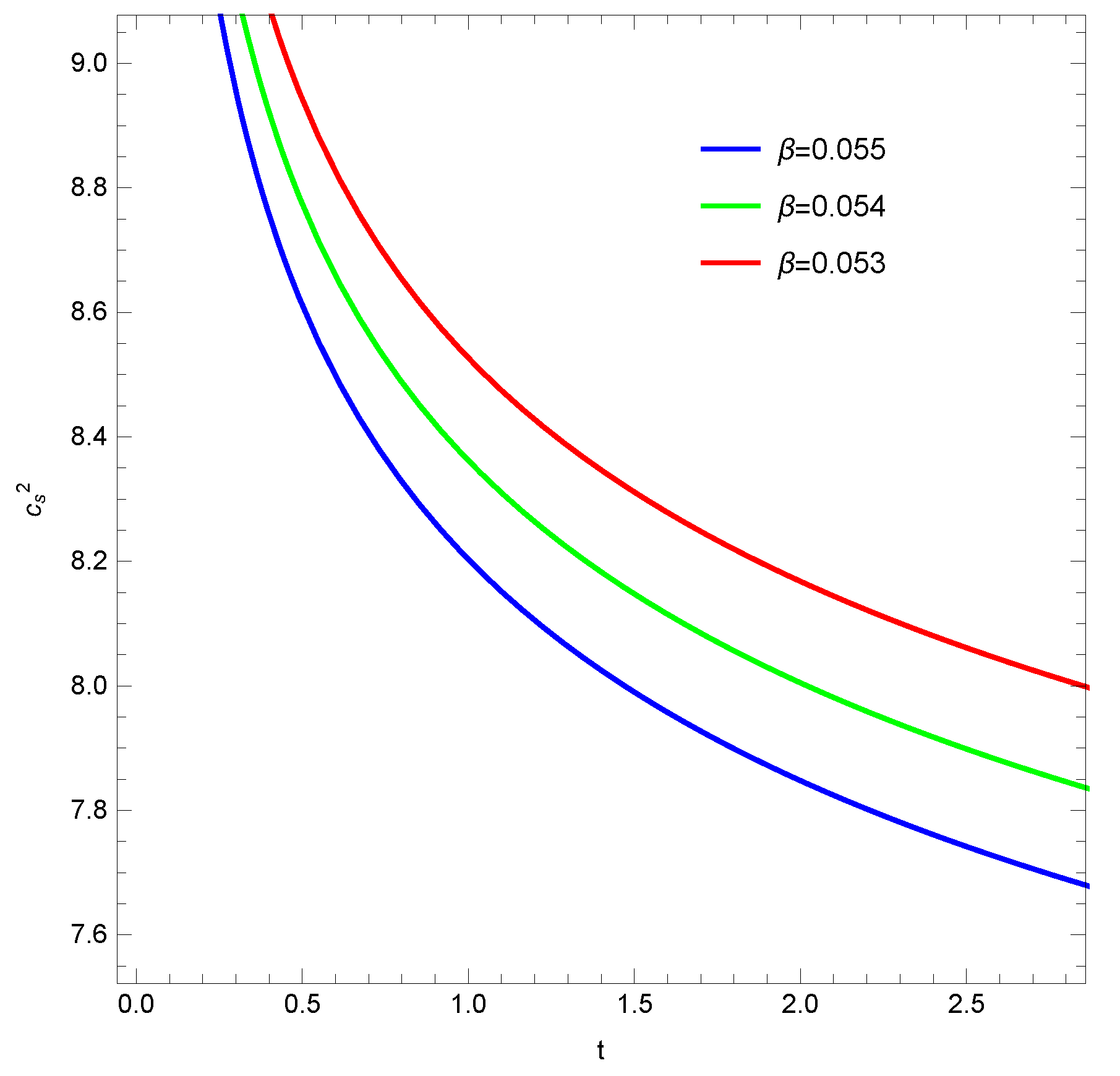

- For the second model with the intermediate scale factor we observe that the function f increases with time(cf. Figure 4). From Figure 5, we see that the EoS parameter shows a quintessence behaviour at a later stage and shows acceleration() in the early stage. The squared speed of sound is greater than 0 when plotted against time(cf. Figure 6).

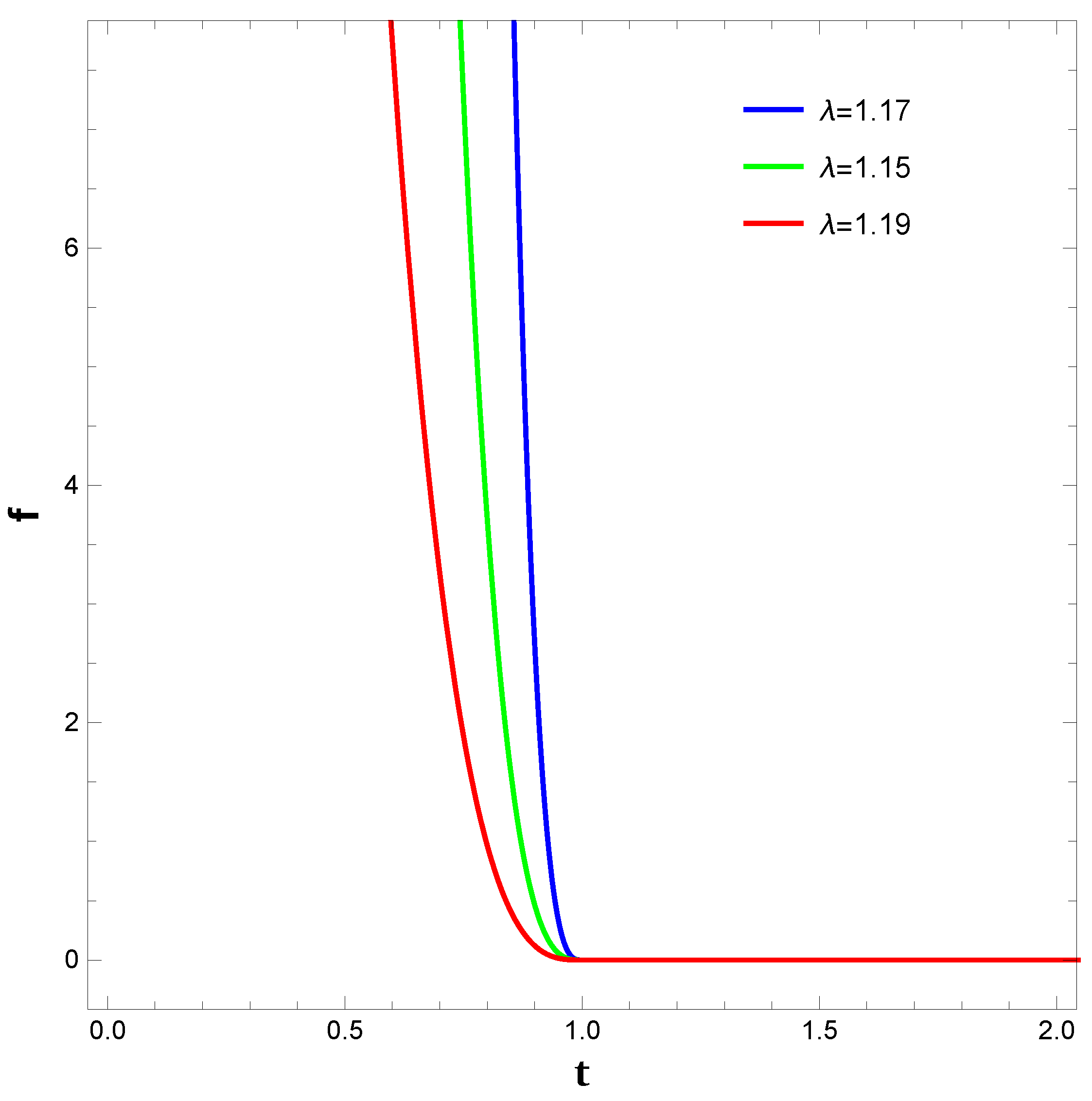

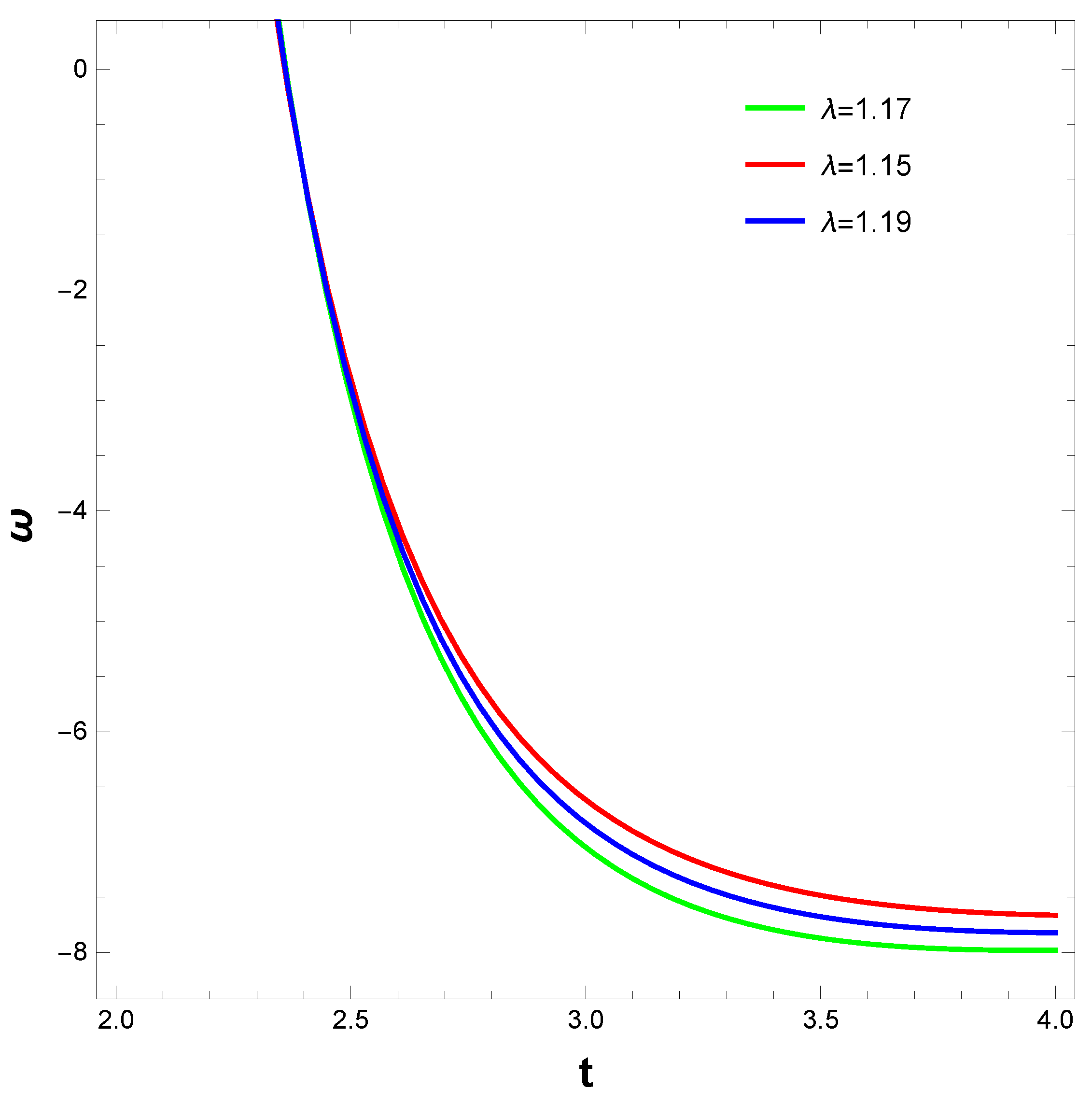

- In our third model, we have chosen the logamediate scale factor and proceeded with the reconstruction of gravity like the previous two models. The reconstructed function when plotted against time (cf. Figure 7) shows a monotonic decrease with time and asymptotically tends to 0 at . A transition from quintessence to phantom behaviour is exhibited by the EoS parameter in this case(see Figure 8)

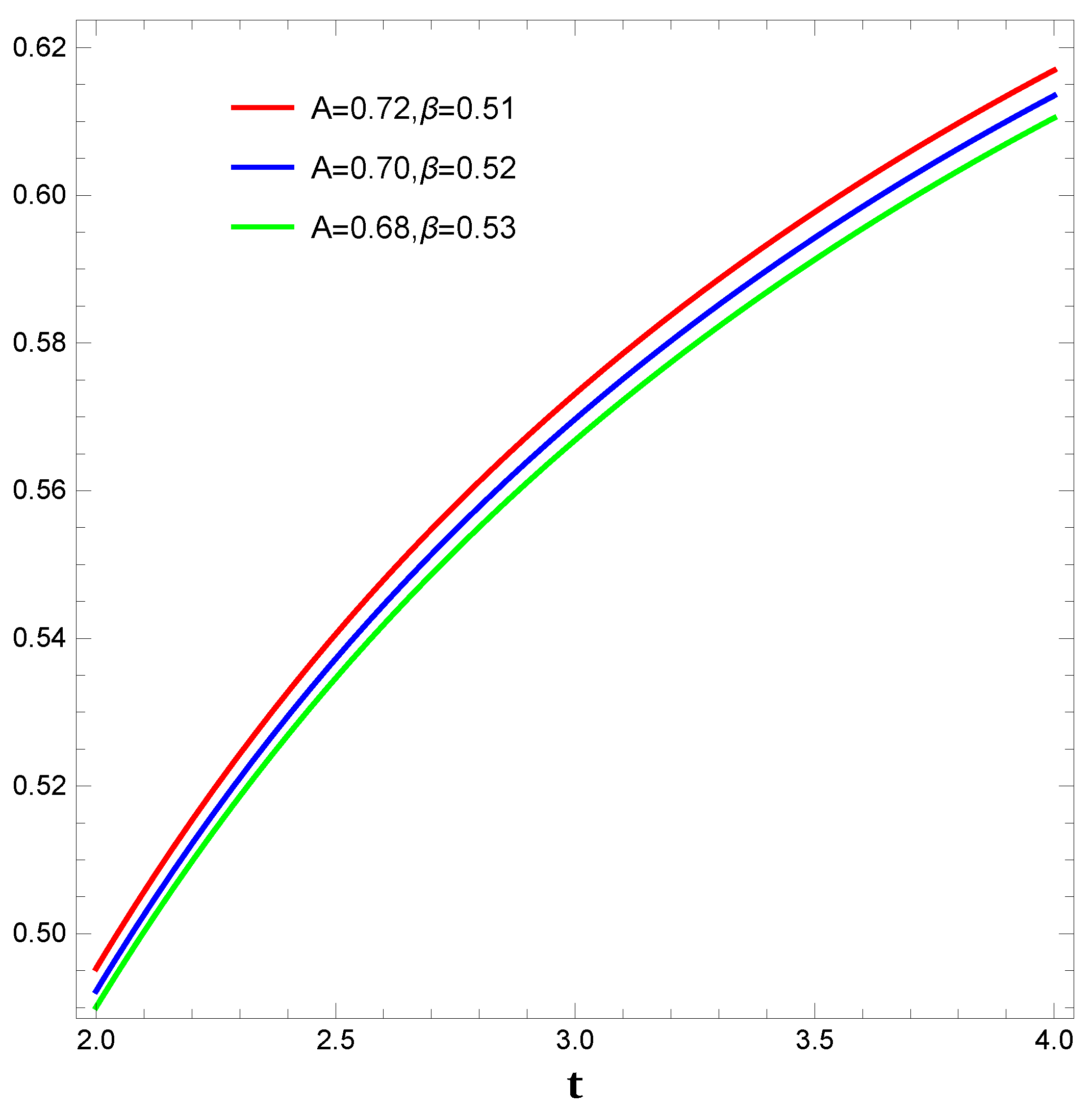

- For our fourth cosmological model, we have taken a power-law-like function for the torsion and boundary scalar. Choosing the intermediate scale factor, we have reconstructed the EoS parameter, the methodology for which have been discussed in subSection 3.4. We have obtained the EoS parameters for 3 different cases based on the constants in the functional form of that we assumed. The figures (cf. Figure 9) show that for different cases, the behavior of the EoS parameter is mainly phantom-like, a result that is similar to the findings by [131].

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sami, M. and Myrzakulov, R. Late-time cosmic acceleration: ABCD of dark energy and modified theories of gravity. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2016, 25, 163001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, S.A.; Gangopadhyay, M.R.; Sami, M. and Sharma, M. K. Late-time acceleration due to a generic modification of gravity and the Hubble tension Phys. Rev. D 2021, 10, 163001. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Zurek, K.M. and Watson, S. Unified approach to cosmic acceleration Phys. Rev. D 2010, 81, 124008. [Google Scholar]

- Nojiri, S.I. and Odintsov, S.D. Unifying phantom inflation with late-time acceleration: Scalar phantom–non-phantom transition model and generalized holographic dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 38, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; Clocchiatti, A.; Diercks, A.; Garnavich, P.M.; Gilliland, R.L.; Hogan, C.J.; Jha, S.; Kirshner, R.P. and Leibundgut, B.R.U.N.O. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. AJ 1998, 116, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permutter, S.; Aldering, G.; Goldhaber, G.; Knop, R.A.; Nugent, P. and Castro, P.G. Measurements of omega and lambda from 42 high redshift supernovae. ApJ 1999, 517, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, D.H.; Mortonson, M.J.; Eisenstein, D.J.; Hirata, C.; Riess, A.G. and Rozo, E. Observational probes of cosmic acceleration. Phys. Rep. 2013, 530, 87–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridasu, B.S.; Luković, V.V.; D’Agostino, R. and Vittorio, N. Strong evidence for an accelerating universe. Phys. Rep. 2017, 600, L1. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, E.J.; Sami, M.; and Tsujikawa, S. Dynamics of dark energy. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2006, 15, 1753–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.D.; Wang, S and Wang, Y. Dark Energy. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2011, 563, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dark Energy Survey Collaboration:, Abbott, T. ; Abdalla, F.B.; Aleksić, J.; Allam, S.; Amara, A.; Bacon, D.; Balbinot, E.; Banerji, M.; Bechtol, K.; and Benoit-Lévy, A. The Dark Energy Survey: more than dark energy–an overview. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 460, 270–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Amendola, L. and Tsujikawa, S. Dark energy: theory and observations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frieman, J.A.; Turner, M.S. and Huterer, D. Strong evidence for an accelerating universe. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 46, 385–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huterer, D. and Turner, M.S. Probing dark energy: Methods and strategies. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 64, 123527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.M. The cosmological constant. Living Rev. Relativ. 2001, 4, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, P.J.E. and Ratra, B. The cosmological constant and dark energy Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 559. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon, R.; Shafieloo, A.; Hazra, D.K. and Sohn, W. On the consistency of Λ CDM with CMB measurements in light of the latest Planck, ACT and SPT data. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2023, 2023, 059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L. and Cao, S. Comparing the scalar-field dark energy models with recent observations. Phys. Dark Universe 2022, 36, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagni, G. and Liddle, A.R. Tachyon dark energy models: Dynamics and constraints. Phys. Rev. D. 2006, 74, 043528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Güdekli, E. and Chattopadhyay, S. Some versions of Chaplygin gas model in modified gravity framework and validity of generalized second law of thermodynamics. Z NATURFORSCH A 2024, 79, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S. A study on the bouncing behavior of modified Chaplygin gas in presence of bulk viscosity and its consequences in the modified gravity framework. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2017, 14, 1750181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokyi, K.K. and Chattopadhyay, S. A truncated scale factor to realize cosmological bounce under the purview of modified gravity. Astron. Nachr. 2023, 344, e220119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S. and Chattopadhyay, S. Realization of bounce in a modified gravity framework and information theoretic approach to the bouncing point. Universe 2023, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqua, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. and Myrzakulov, R. Consequences of three modified forms of holographic dark energy models in bulk–brane interaction Can. J. Phys. 2018, 96, 112-125.

- Brax, P.; van de Bruck, C. and Davis, A.C. Brane world cosmology. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2004, 67, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, U. and Zhuk, A. Phenomenology of brane-world cosmological models. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, M. Testing general relativity in cosmology. Living Rev. Relativ. 2019, 22, 1–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shankaranarayanan, S. and Johnson, J.P. Modified theories of gravity: Why, how and what? Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2022, 54, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, F.S. The dark side of gravity: Modified theories of gravity. arXiv arXiv:0807.1640.

- Paul, B.C.; Debnath, P.S. and Ghose, S. Accelerating universe in modified theories of gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 083534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbisà, F. Modified Theories of Gravity. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.3384. 2014, arXiv:1406.3384. [Google Scholar]

- Capozziello, S. and De Laurentis, M. Extended theories of gravity. Phys. Rep. 2011, 509, 167–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Lobo, F.S. and Mimoso, J.P. Generalized energy conditions in extended theories of gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 124019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S. and Francaviglia, M. Extended theories of gravity and their cosmological and astrophysical applications. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 40, 357–420. [Google Scholar]

- Nojiri, S.I. and Odintsov, S. D. Introduction to modified gravity and gravitational alternative for dark energy Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2007, 4, 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wands, D. Extended gravity theories and the Einstein–Hilbert action Class. Quantum Gravity 1994, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Cardone, V.F. and Salzano, V. Cosmography of f (R) gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 78, 063504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, T.P. and Faraoni, V. Modified Theories of Gravity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 451–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. and Radinschi, I. A holographic reconstruction scheme for f (R) gravity and the study of stability and thermodynamic consequences. New Astron. 2020, 76, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.C. and Noh, H. f(R) gravity theory and CMBR constraints. Phys. Lett. B 2001, 506, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bamba, K.; Nojiri, S.I. , Odintsov, S.D. and Saez-Gomez, D. Inflationary universe from perfect fluid and F(R) gravity and its comparison with observational data. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 124061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, J. and Vilja, I. f (R) gravity constraints from gravitational waves. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2017, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Piedipalumbo, E.; Rubano, C. and Scudellaro, P. Testing an exact f (R)-gravity model at Galactic and local scales. Astron. Astrophys. 2009, 505, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ky, N.A.; Van Ky, P.; and Van, N.T.H. Testing the f(R)-theory of gravity. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.04013. 2019, arXiv:1904.04013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.D. and Oikonomou, V. Modified gravity theories on a nutshell: Inflation, bounce and late-time evolution. Phys. Rep. 2017, 692, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S. A study on the interacting Ricci dark energy in f (R, T) gravity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India - Phys. Sci. 2014, 84, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqua, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. and Myrzakulov, R. arXiv preprint arXiv:1306.0991. 2013, arXiv:1306.0991. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M. and Zubair, M. Study of thermodynamic laws in f (R, T, RμνTμν) gravity. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2013, 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. Unifying framework for scalar-tensor theories of gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 081501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y. and Maeda, K.I. The scalar-tensor theory of gravitation.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wagoner, R.V. Scalar-tensor theory and gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. D 1970, 1, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I. and Odintsov, S.D. Unified cosmic history in modified gravity: from F (R) theory to Lorentz non-invariant models. Phys. Rep. 2011, 505, 59–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, V.C.; Guillen, L.C.T. and Pereira, J.G. Teleparallel gravity: an overview. In he Ninth Marcel Grossmann Meeting: On Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity, Gravitation and Relativistic Field Theories, 2002; pp. 1022-1023.

- Bahamonde, S. , Böhmer, C.G. and Krššák, M. New classes of modified teleparallel gravity models. Phys. Lett. B 2017, 775, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garecki, J. Teleparallel equivalent of general relativity: a critical review. arXiv preprint arXiv:1010.2654. 2010, arXiv:1010.2654. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. and Khan, G. From Hessian to Weitzenböck: Manifolds with torsion-carrying connections. Inf. Geom. 2019, 2, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Y.C.; Izumi, K.; Nester, J.M. and Chen, P. Problems with propagation and time evolution in f (T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 024019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sotiriou, T.P. and Barrow, J.D. f (T) gravity and local Lorentz invariance. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 83, 064035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.J. New types of f (T) gravity EUR. PHYS. J. C 2011, 71, 59–144. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. and Reboucas, M.J. New types of f (T) gravity Phys. Rev. 2012, 86, 083515. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.J. New types of f (T) gravity EUR. PHYS. J. C 2011, 71, 59–144. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Miao, R.X. and Miao, Y.G. Degrees of freedom of f (T) gravity. J. High Energy Phys 2011, 2011, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krššák, M. and Saridakis, E.N. The covariant formulation of f (T) gravity Class. QuantumGravity. 2016, 33, 11509. [Google Scholar]

- Bahamonde, S.; Böhmer, C.G. and Krššák, M. New classes of modified teleparallel gravity models Phys. Lett. B 2017, 775, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tamanini, N. and Boehmer, C.G. Good and bad tetrads in f (T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 044009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, S.; Böhmer, C.G. and Wright, M. Modified teleparallel theories of gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 92, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salako, I.G.; Rodrigues, M.E.; Kpadonou, A.V.; Houndjo, M.J.S. and Tossa, J. ΛCDM model in f (T) gravity: reconstruction, thermodynamics and stability. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2013, 2013, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Setare, M.R. and Mohammadipour, N. Can f (T) gravity theories mimic ΛCDM cosmic history. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2013, 1, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L. The world as a hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.R.; Hooft, G.T. and Whiting, B.F. Black hole evaporation without information loss. Class. Quantum Gravity 1994, 11, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Anti de Sitter space and holography. arXiv preprint hep-th/9802150. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L. and Witten, E. The holographic bound in anti-de Sitter space. arXiv preprint hep-th/9805114. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, W. and Susskind, L. Holography and cosmology. arXiv preprint hep-th/9806039. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D. and Paul, T. Different faces of generalized holographic dark energy. Symmetry 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhi, A. Holographic scalar field models of dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 107302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M. and Lepe, S. Modeling holographic dark energy with particle and future horizons. Nucl. Phys. B 2020, 956, 115017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, E. and Khurshudyan, M. An interacting new holographic dark energy model: Observational constraints. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2019, 28, 1950152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradpour, H.; Ziaie, A.H. and Zangeneh, M.K. Generalized entropies and corresponding holographic dark energy models. EUR. PHYS. J. C 2020, 80, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, Y.S. and Seo, M.G. Origin of holographic dark energy models. Phys. Lett. B 2009, 671, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.D.; Wang, S. and Zhang, X. Holographic dark energy models: A comparison from the latest observational data. Nucl. Phys. B 2009, 2009, 036. [Google Scholar]

- Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D.; Oikonomou, V.K. and Paul, T. Unifying holographic inflation with holographic dark energy: A covariant approach. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 102, p.023540.

- Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D. and Paul, T. Holographic realization of constant roll inflation and dark energy: An unified scenario. Phys. Lett. B 2023, 841, 137926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wu, F.; Chen, X. and Shen, Y.G. Holographic dark energy model from Ricci scalar curvature. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 043511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I. and Odintsov, S.D. Covariant generalized holographic dark energy and accelerating universe. EUR. PHYS. J. C 2017, 77, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I. and Odintsov, S.D. Unifying phantom inflation with late-time acceleration: Scalar phantom–non-phantom transition model and generalized holographic dark energy. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2006, 38, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.J. Ricci dark energy in Brans-Dicke theory. arXiv preprint arXiv:0806.0673. 2008, arXiv:0806.0673. [Google Scholar]

- Odintsov, S.D.; Paul, T. and SenGupta, S. Second law of horizon thermodynamics during cosmic evolution. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 104, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.G. and Kim, S.P. First law of thermodynamics and Friedmann equations of Friedmann-Robertson-Walker universe. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 2005, 050. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, M. and Cai, R.G. Thermodynamic behavior of the Friedmann equation at the apparent horizon of the FRW universe. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 75, 084003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhi, A.; Wang, B. and Cai, R.G. Deep connection between thermodynamics and gravity in Gauss-Bonnet braneworlds. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 023515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhi, A.; Wang, B. and Cai, R.G. Thermodynamical properties of apparent horizon in warped DGP braneworld. Nucl. Phys. B 2007, 779, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.G. and Cao, L.M. Unified first law and the thermodynamics of the apparent horizon in the FRW universe. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 75, 064008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M. and Cai, R.G. Thermodynamic behavior of field equations for f (R) gravity. Phys. Lett. B 2007, 648, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.G.; Cao, L.M.; Hu, Y.P. and Kim, S.P. Generalized Vaidya spacetime in Lovelock gravity and thermodynamics on the apparent horizon. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 78, 124012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D.; Paul, T. and SenGupta, S. Horizon entropy consistent with the FLRW equations for general modified theories of gravity and for all equations of state of the matter field Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 043532. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, R.X.; Li, M. and Miao, Y.G. Violation of the first law of black hole thermodynamics in f (T) gravity. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2011, 2011, 033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, K.; Jamil, M.; Momeni, D. and Myrzakulov, R. Generalized second law of thermodynamics in f (T) gravity with entropy corrections. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2013, 344, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, K. and Abdolmaleki, A. Generalized second law of thermodynamics in f (T) gravity. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2012, 2012, 007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, G. and Said, J.L. Stability of the flat FLRW metric in f (T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 124054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, M.; Farrugia, G. and Levi Said, J. Cosmological bouncing solutions in f (T, B) gravity. EUR. PHYS. J. C 2020, 80, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, S. and Capozziello, S. Noether symmetry approach in f (T, B) teleparallel cosmology EUR. PHYS. J. C 2017, 77,1-10.

- Franco, G.A.R.; Escamilla-Rivera, C. and Levi Said, J. Stability analysis for cosmological models in f (T, B) gravity. EUR. PHYS. J. C 2020, 80, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Rivera, C. and Said, J.L. Cosmological viable models in f (T, B) theory as solutions to the H0 tension. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 165002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S. and Pasqua, A. Various aspects of interacting modified holographic Ricci dark energy. Indian J. Phys. 2013, 87, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.F. and Maartens, R. The emergent universe: Inflationary cosmology with no singularity. Class. Quantum Gravity 2003, 21, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G.F.; Murugan, J. and Tsagas, C.G. The emergent universe: an explicit construction. Class. Quantum Gravity 2003, 21, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Mulryne, D.J.; Tavakol, R.; Lidsey, J.E. and Ellis, G.F. An emergent universe from a loop. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 71, 123512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.M. and Neupane, I.P. Thermodynamics and stability of higher dimensional rotating (Kerr-) AdS black holes. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 1043534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Paul, B.C.; Dadhich, N.K.; Maharaj, S.D. and Beesham, A. Emergent universe with exotic matter. Class. Quantum Gravity 2006, 23, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S. and Debnath, U. Role of generalized Ricci dark energy on a Chameleon field in the emergent universe. Can. J. Phys. 2011, 89, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannestad, S. Constraints on the sound speed of dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 71, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, D.J. Dark energy and cosmic sound. New Astron. Rev. 2005, 49, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. Graduated inflationary universes. Phys. Lett. B 1990, 235, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H. A brief analysis of de Sitter universe in relativistic cosmology. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2017, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tutusaus, I.; Lamine, B.; Blanchard, A.; Dupays, A.; Zolnierowski, Y.; Cohen-Tanugi, J.; Ealet, A.; Escoffier, S.; Le Fèvre, O.; Ilić, S. and Pisani, A. Power law cosmology model comparison with CMB scale information. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. and Saich, P. The behaviour of intermediate inflationary universes. Phys. Lett. B 1990, 249, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. and Liddle, A.R. Perturbation spectra from intermediate inflation. Phys. Lett. B 1993, 47, R5219. [Google Scholar]

- Rezazadeh, K.; Abdolmaleki, A. and Karami, K. Logamediate inflation in f (T) teleparallel gravity. Astrophys. J. 2017, 836, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. Varieties of expanding universe. Class. Quantum Gravity 1996, 13, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. and Parsons, P. Inflationary models with logarithmic potentials. Phys. Rev. D 1995, 52, 5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. and Nunes, N.J. Dynamics of “logamediate” inflation. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 043501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, S. and Capozziello, S. Noether symmetry approach in f (T, B) teleparallel cosmology. EUR. PHYS. J. C 2017, 77, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. and Debnath, U.. Validity of the generalized second law of thermodynamics in the logamediate and intermediate scenarios of the Universe. Found. Phys. 2012, 42, 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Pasqua, A. and Chattopadhyay, S. Generalized second law of thermodynamics in the emergent universe for some viable models of f (T) gravity. EUR. PHYS. J. C 2013, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, G.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Güdekli, E. and Radinschi, I. Thermodynamics of Barrow holographic dark energy with specific cut-off. Symmetry 2021, 13, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, S.; Zubair, M. and Abbas, G. Thermodynamics and cosmological reconstruction in f (T, B) gravity. Phys. Dark Universe 2018, 19, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D. and Paul, T. Different faces of generalized holographic dark energy. Symmetry 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D. and Paul, T. Barrow entropic dark energy: A member of generalized holographic dark energy family. Phys. Lett. B 2022, 825, 136844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D. and Saridakis, E.N. Modified cosmology from extended entropy with varying exponent. EUR. PHYS. J. C 2019, 79, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.I. and Odintsov, S.D. Unifying phantom inflation with late-time acceleration: Scalar phantom–non-phantom transition model and generalized holographic dark energy. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2006, 38, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Rivera, C. and Said, J.L. Cosmological viable models in f (T, B) theory as solutions to the H0 tension. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 165002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetry, B.; Dutta, J. and Abdolmaleki, A. Thermodynamics of event horizon with modified Hawking temperature in scalar-tensor gravity. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2018, 50, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haro, J.; Nojiri, S.I.; Odintsov, S.D. , Oikonomou V.K. and Pan, S Finite-time cosmological singularities and the possible fate of the Universe. Phys. Rep. 2023, 1034, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).