Submitted:

26 August 2024

Posted:

27 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Salinity Index Construction

2.4. Model Construction and Accuracy Evaluation

2.4.1. Model Construction and Model Parameters Determination

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis between Spectral Indexes and Soil Salinity

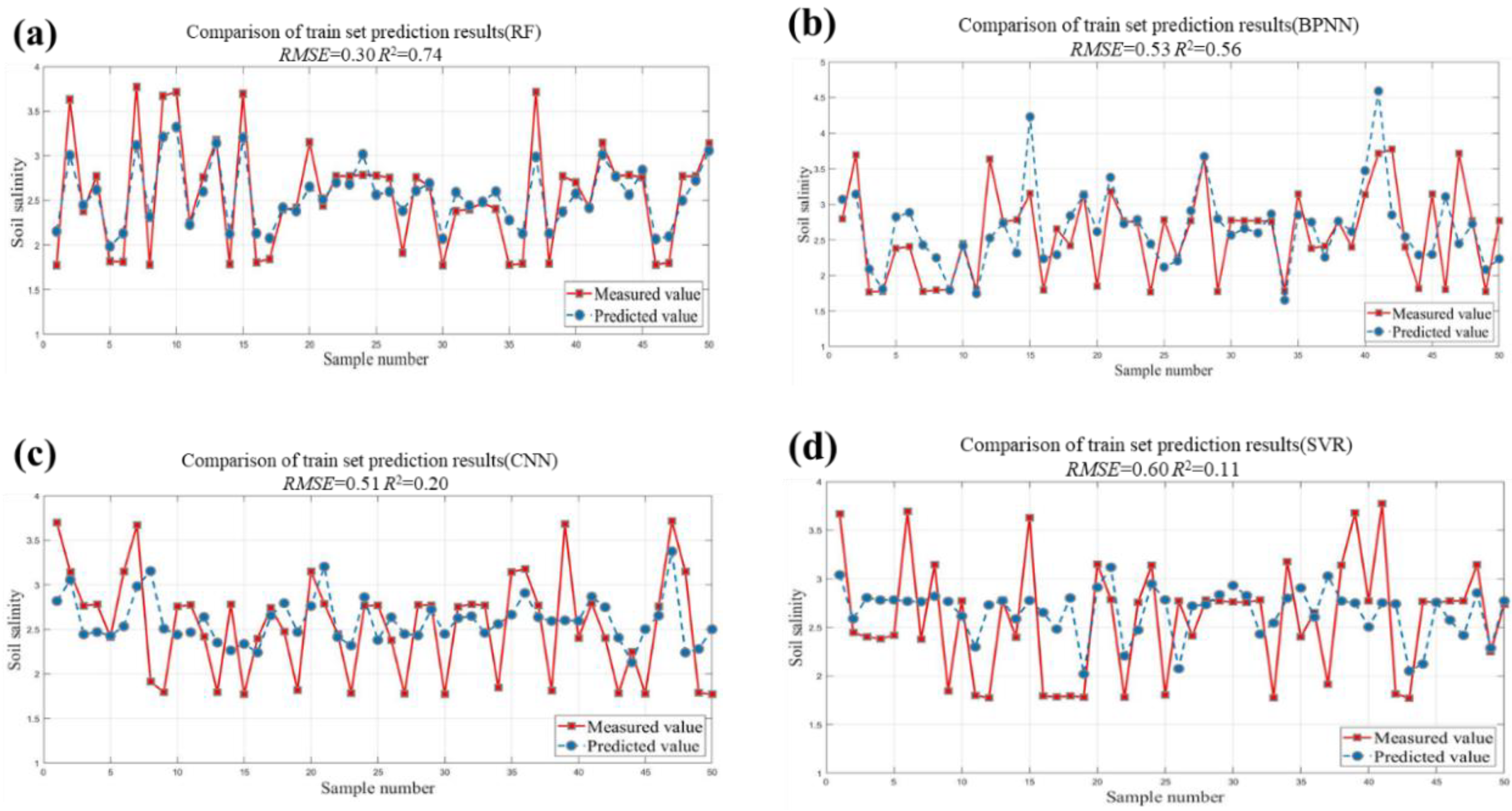

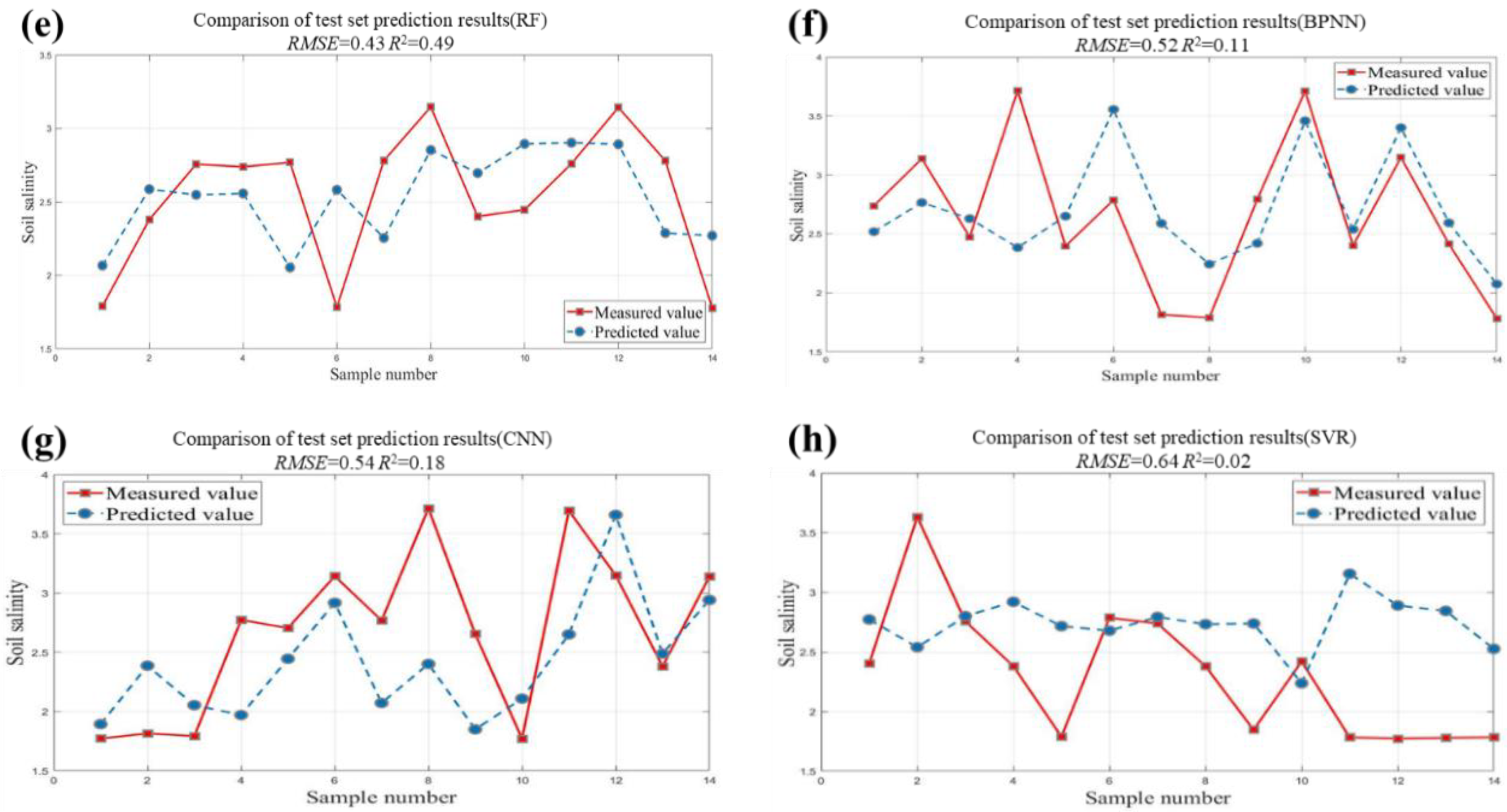

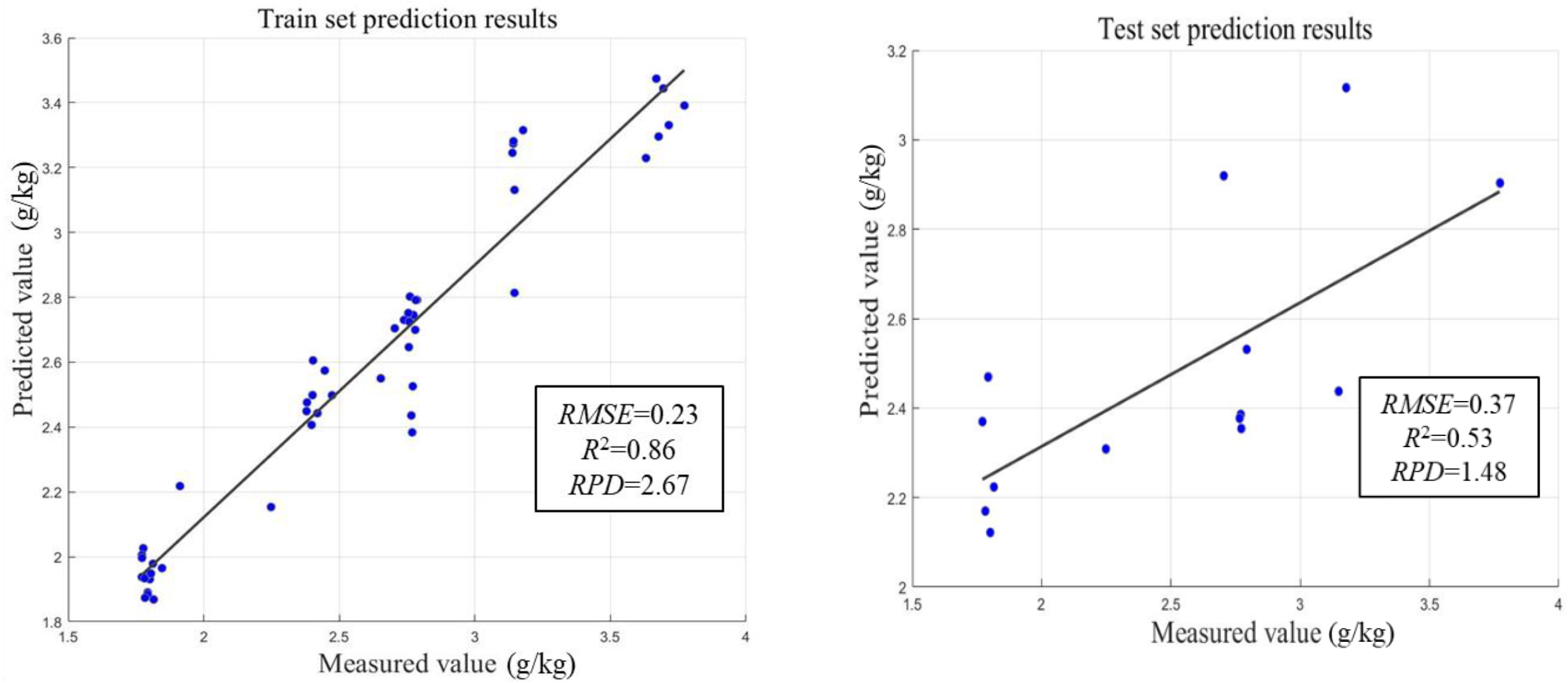

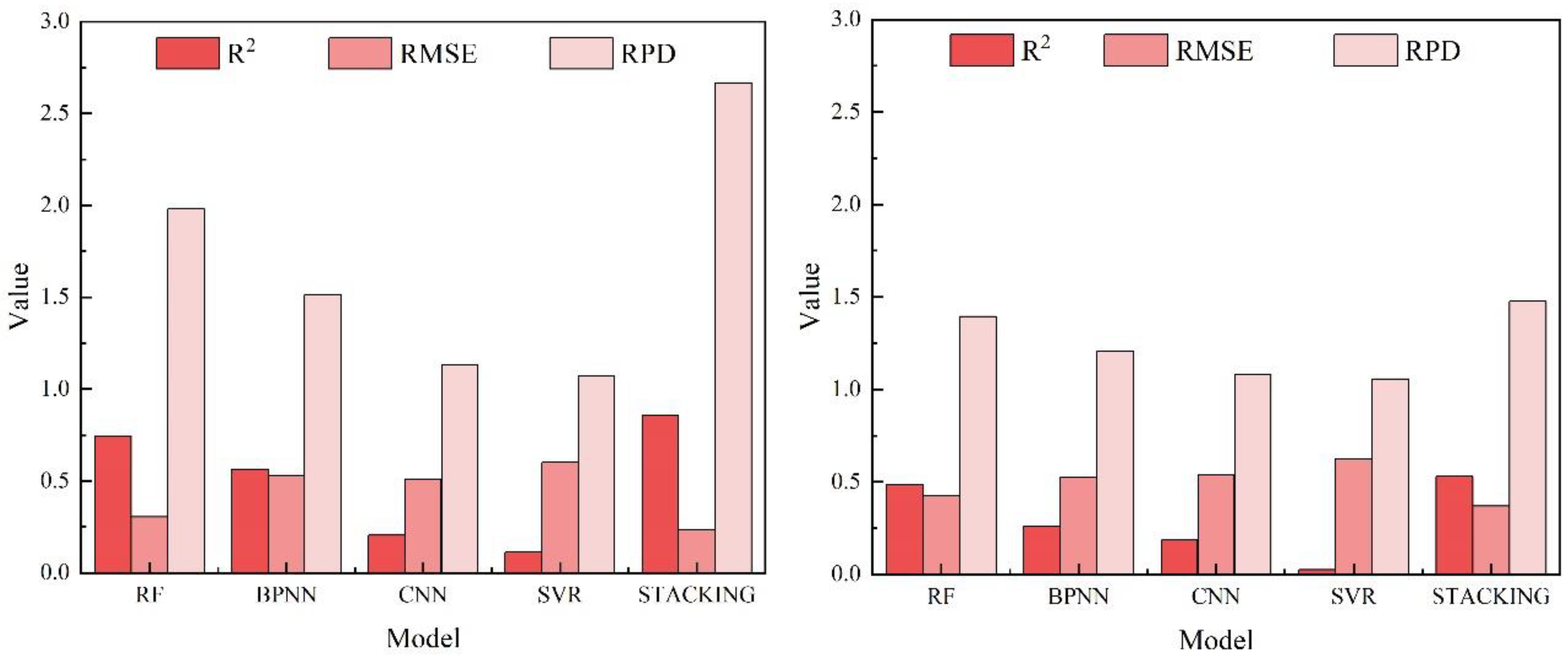

3.2. Evaluation of Machine Learning Regression Models

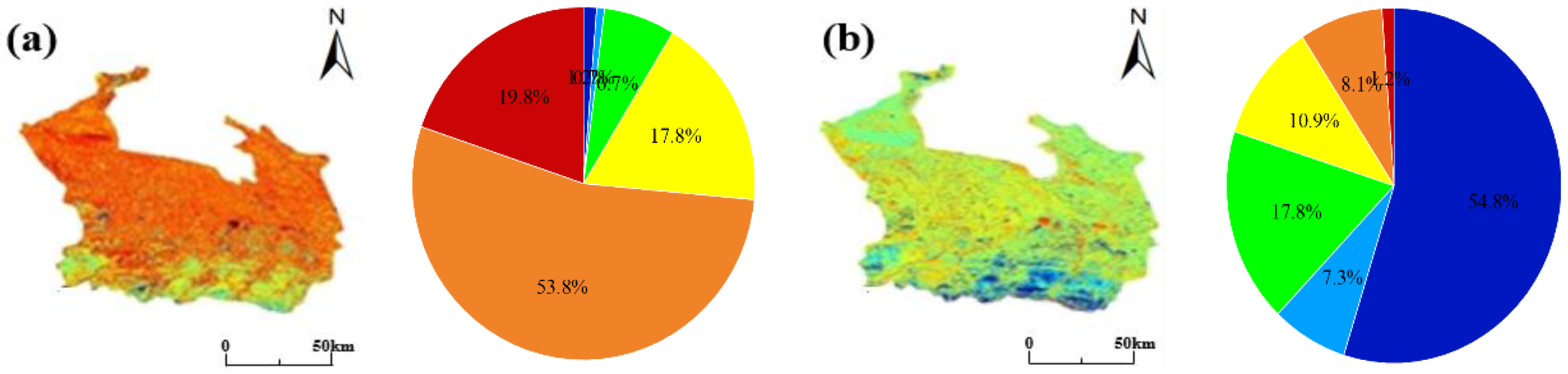

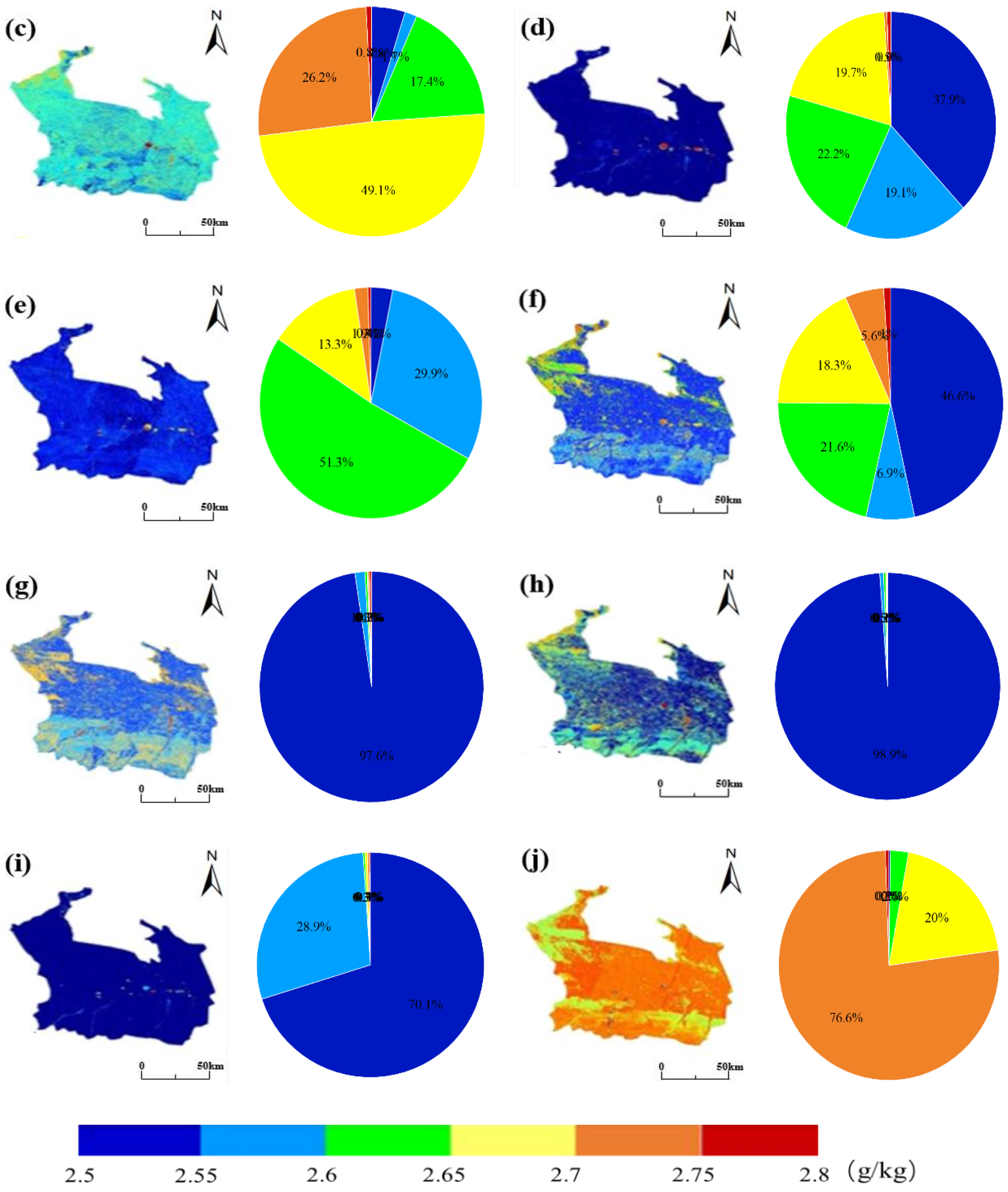

3.4. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Soil Salinity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivushkin K, Bartholomeus H, Bregt A K, et al. Global mapping of soil salinity change. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 231, 111260. [CrossRef]

- Allbed A, Kumar L, Aldakheel Y Y. Assessing soil salinity using soil salinity and vegetation indices derived from IKONOS high-spatial resolution imageries: Applications in a date palm dominated region. Geoderma 2014, 230-231, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Metternicht G I, Zinck J A. Remote sensing of soil salinity: potentials and constraints. Remote Sensing of Environment 2003, 85, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Zhao W, Zhou C, Zhou C, et al. Soil Salinity Inversion Model of Oasis in Arid Area Based on UAV Multispectral Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1804. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Biswas A, Jiang Q, et al. Estimating soil salinity from remote sensing and terrain data in southern Xinjiang Province, China. Geoderma 2019, 337, 1309-1319. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Zhang X, Zhang F, et al. Estimation of soil salt content using machine learning techniques based on remote-sensing fractional derivatives, a case study in the Ebinur Lake Wetland National Nature Reserve, Northwest China. Ecological Indicators 2020, 119, 106869. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Chen Y, Wang M, et al. SPA-Based Methods for the Quantitative Estimation of the Soil Salt Content in Saline-Alkali Land from Field Spectroscopy Data: A Case Study from the Yellow River Irrigation Regions. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 967. [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, Zhang J. Estimation of SPAD value in tomato leaves by multispectral images. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2020, 1634, 012128. [CrossRef]

- Narjary B ,Meena, M.D, Kumar S ,et al. Digital mapping of soil salinity at various depths using an EM38.Soil Use and Management, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Csillag F, Pásztor L, Biehl L L. Spectral band selection for the characterization of salinity status of soils. Remote Sensing of Environment 1993, 43, 231-242. [CrossRef]

- Eldeiry A A, Garcia L A. Detecting Soil Salinity in Alfalfa Fields using Spatial Modeling and Remote Sensing. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2008, 72, 201-211. [CrossRef]

- Kalra N K, Joshi D C. Potentiality of Landsat, SPOT and IRS satellite imagery, for recognition of salt affected soils in Indian Arid Zone. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1996, 17, 3001-3014. [CrossRef]

- Ding J, Yu D. Monitoring and evaluating spatial variability of soil salinity in dry and wet seasons in the Werigan–Kuqa Oasis, China, using remote sensing and electromagnetic induction instruments. Geoderma 2014, 235-236, 316-322. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Chen H, Zhao G, et al. Spectral Index Fusion for Salinized Soil Salinity Inversion Using Sentinel-2A and UAV Images in a Coastal Area. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 159595-159608. [CrossRef]

- Bannari A, El-Battay A, Bannari R, et al. Sentinel-MSI VNIR and SWIR Bands Sensitivity Analysis for Soil Salinity Discrimination in an Arid Landscape. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 855. [CrossRef]

- Dehni A, Lounis M. Remote Sensing Techniques for Salt Affected Soil Mapping: Application to the Oran Region of Algeria. Procedia Engineering 2012, 33, 188-198. [CrossRef]

- Aldabaa A A A, Weindorf D C, Chakraborty S, et al. Combination of proximal and remote sensing methods for rapid soil salinity quantification. Geoderma 2015, 239-240, 34-46. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang C, Wright A, et al. Combination of GF-2 high spatial resolution imagery and land surface factors for predicting soil salinity of muddy coasts. CATENA 2021, 202, 105304. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Smith S E, Grunwald S, et al. Estimating soil total nitrogen in smallholder farm settings using remote sensing spectral indices and regression kriging. CATENA 2018, 163, 111-122. [CrossRef]

- An D, Zhao G, Chang C, et al. Hyperspectral field estimation and remote-sensing inversion of salt content in coastal saline soils of the Yellow River Delta. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2016, 37, 455-470. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Y, Chen C, Han J, et al. Satellite remote sensing estimation modeling of soil salinity in the irrigation domain of Jiefangzha under vegetation cover conditions. Water Saving Irrigation 2019, 108-112. CNKI:SUN:JSGU.0.2019-10-024.

- Wu C, Liu G, Huang C. Prediction of soil salinity in the Yellow River Delta using geographically weighted regression. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2017, 63, 928-941. [CrossRef]

- Lin C Y, Lin C. Using Ridge Regression Method to Reduce Estimation Uncertainty in Chlorophyll Models Based on Worldview Multispectral Data[C]//IGARSS 2019-2019 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. 2019, 1777-1780.

- Adab H, Morbidelli R, Saltalippi C, et al. Machine Learning to Estimate Surface Soil Moisture from Remote Sensing Data. Water 2020, 12, 3223. [CrossRef]

- Tang S F, Tian Q J, Xu K J, et al. Inversion of larch forest age information by Sentinel-2 satellite. Journal of Remote Sensing 2020, 24, 1511-1524.

- Christensen S W. Ensemble Construction via Designed Output Distortion[M]//Windeatt T, Roli F. Multiple Classifier Systems: 2709. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2003, 286-295.

- Ghosh S M, Behera M D, Jagadish B, et al. A novel approach for estimation of aboveground biomass of a carbon-rich mangrove site in India. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 292, 112816. [CrossRef]

- Dietterich T G. Ensemble Methods in Machine Learning[C]//Multiple Classifier Systems. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2000, 1-15.

- Tao S, Zhang X, Feng R, et al. Retrieving soil moisture from grape growing areas using multi-feature and stacking-based ensemble learning modeling. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 204, 107537. [CrossRef]

- Qi J, Zhang X, McCarty G W, et al. Assessing the performance of a physically-based soil moisture module integrated within the Soil and Water Assessment Tool. Environmental Modelling & Software 2018, 109, 329-341. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Wu Y, Li R, et al. Remote sensing-based retrieval of soil moisture content using stacking ensemble learning models. Land Degradation & Development 2023, 34, 911-925. [CrossRef]

- Yang X H, Luo Y Q, Yang H C, et al. Inversion and spatial distribution characteristics of soil salinity in oasis farmland in Manas River basin. Arid Zone Resources and Environment 2021, 35, 156-161.

- Zhang L. Study on salinized land use change and utilization potential in oasis-desert area of Manas River Basin [D]. Xinjiang Agricultural University, 2013.

- Gu G A. Formation of salinized soil and its prevention and control in Xinjiang . Xinjiang Geography 1984, 1-16.

- Yang H C, Zhang F H, Wang D F et al. Trends of evapotranspiration from oases in the Mahe River Basin over the past 60 years and analysis of their influencing factors. Arid Zone Resources and Environment 2014, 28, 18-23.

- Xin M L, Lv T B, He X L, et al. Spatial analysis of soil salinity in Manas River irrigation area based on ROC curve. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage 2016, 35, 45-50.

- Tian F, Fensholt R, Verbesselt J, et al. Evaluating temporal consistency of long-term global NDVI datasets for trend analysis. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, 163, 326-340. [CrossRef]

- Forkel M, Carvalhais N, Verbesselt J, et al. Trend Change Detection in NDVI Time Series: Effects of Inter-Annual Variability and Methodology. Remote Sensing 2013, 5, 2113-2144. [CrossRef]

- Vaudour E, Gomez C, Lagacherie P, et al. Temporal mosaicking approaches of Sentinel-2 images for extending topsoil organic carbon content mapping in croplands. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 96, 102277. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha R P. Relating soil electrical conductivity to remote sensing and other soil properties for assessing soil salinity in northeast Thailand. Land Degradation & Development 2006, 17, 677-689. [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi M S, Glenn E P. Detecting date palm trees health and vegetation greenness change on the eastern coast of the United Arab Emirates using SAVI. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2008, 29, 1745-1765. [CrossRef]

- Yao Y, Ding J L, Zhang F, et al. Regional soil salinization monitoring model based on hyperspectral index and electromagnetic induction. Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 2013, 33, 1658-1664.

- Douaoui A E K, Nicolas H, Walter C. Detecting salinity hazards within a semiarid context by means of combining soil and remote-sensing data. Geoderma 2006, 134, 217-230. [CrossRef]

- Abbas A, Khan S, Hussain N, et al. Characterizing soil salinity in irrigated agriculture using a remote sensing approach. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 2013, 55-57, 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Khan N M, Rastoskuev V V, Shalina E V, et al. Mapping Salt-affected Soils Using Remote Sensing Indicators - A Simple Approach With the Use of GIS IDRISI. 2001.

- Liu H J, Yang H X, Xu M Y et al. Soil classification based on multi-temporal remote sensing image features and maximum likelihood method during bare soil period. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2018, 34, 132-139+304.

- Fu B L, Deng L C, Zhang L, et al. Remote sensing inversion of chlorophyll content in mangrove canopy with combined on-board hyperspectral imagery and stacked integrated learning regression algorithm. Journal of Remote Sensing 2022, 26, 1182-1205.

- Zhang F, Li X, Zhou X, et al. Retrieval of soil salinity based on multi-source remote sensing data and differential transformation technology. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2023, 44, 1348-1368. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z T, Tai X, Yang N, et al. Inversion of soil salinity by unmanned aerial vehicle multispectral remote sensing under different vegetation cover. Journal of Agricultural Machinery 2022, 53, 220-230.

- Hu J, Lv YH. Progress in stochastic modeling of soil moisture dynamics. Progress in Geoscience 2015, 34, 389-400.

- Chen H Y, Zhao G X, Chen J C, et al. Remote sensing inversion of saline soil salinity based on modified vegetation index in estuary area of Yellow River . Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2015, 31, 107-112+114+113.

- Tang X L, Lv X. Impacts of climate change on available precipitation in the Manas River Basin over the past 50 years. Hubei Agricultural Science 2011, 50, 4582-4585.

- Wei G, Li Y, Zhang Z, et al. Estimation of soil salt content by combining UAV-borne multispectral sensor and machine learning algorithms. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9087. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z T, Wei G F, Yao Z H, et al. Research on soil salinity inversion modeling based on multi-spectral remote sensing by unmanned aircraft. Journal of Agricultural Machinery 2019, 50, 151-160.

- Yang H, Hu Y, Zheng Z, et al. Estimation of Potato Chlorophyll Content from UAV Multispectral Images with Stacking Ensemble Algorithm. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2318. [CrossRef]

- Pham K, Won J. Enhancing the tree-boosting-based pedotransfer function for saturated hydraulic conductivity using data preprocessing and predictor importance using game theory. Geoderma 2022, 420, 115864. [CrossRef]

- Obsie E Y, Qu H, Drummond F. Wild blueberry yield prediction using a combination of computer simulation and machine learning algorithms. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 178, 105778. [CrossRef]

- Li W D, Shi X Y, Song J H et al. Analysis of the dominant factors of soil physicochemical properties and salt ion composition in different geomorphic types of Manas River Basin. Journal of Shihezi University (Natural Science Edition),2022,40(01).

- Zhang F H, Zhao Q, Pan X D, et al. Spatial differentiation of soil properties and rational development model of oasis in Mahe Basin, Xinjiang. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2005, 55-58.

- Xia J, Wang S M, Zhu H W, et al. Spatial variability of soil salinity in the middle and lower reaches of the Manas River basin. Xinjiang Agricultural Science 2012, 49, 542-548.

- Yan A, Jiang P A, Sheng J D, et al. Characterization of spatial variability of surface soil salinity in the Manas River Basin. Journal of Soil Science 2014, 51, 410-414.

- Chen J H, Wang S M, Cao G D, et al. Physical properties of soils under different landforms and vegetation types in the Manas River Basin. Xinjiang Agricultural Science 2012, 49, 354-361.

- Zhao Y C, HuDan T M E B, MaHeHuJiang A H M T et al. Characterization of intra- and inter-annual soil salinity changes in perennial drip-irrigated cotton fields in Northern Xinjiang. Research on arid region agriculture 2015, 33.

| Type of index | Spectral index | Abbrev | Formulas | Reference |

| Vegetation spectral indices (VI) | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | NDVI | Shrestha et al. 2006[40] | |

| Difference Vegetation Index | DVI | Shrestha et al. 2006[40] | ||

| Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index | SAVI | Alhammadi et al. 2008[41] | ||

| Ratio Vegetation Index | RVI | Alhammadi et al. 2008[41] | ||

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | GNDVI | Bannari et al. 2018[15] | ||

| Salinity spectral indices (SI) | Salinity Index | SI | Yao Y et al. 2013[42] | |

| Salinity Index 1 | SI1 | Allbed et al. 2014[2] | ||

| Salinity Index 2 | SI2 | Douaoui et al. 2005[43] | ||

| Salinity Index 3 | SI3 | Douaoui et al. 2005[43] | ||

| Salinity Index 7 | SI7 | Abbas et al. 2013[44] | ||

| Normalized Difference Salinity Index | NDSI | Khan et al. 2001[45] | ||

| Soil Salinity Remote Sensing index | SRSI | Alhammadi et al. 2008[41] | ||

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index | NDWI | Liu H J et al. 2018[46] | |

| BI | Brightness Index | BI | Khan et al. 2001[45] |

| Model | Train Set | Test Set | ||||

| R2 | RMSE | RPD | R2 | RMSE | RPD | |

| RF | 0.74 | 0.30 | 1.98 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 1.39 |

| BPNN | 0.56 | 0.53 | 1.51 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 1.21 |

| CNN | 0.20 | 0.51 | 1.13 | 0.18 | 0.54 | 1.08 |

| SVR | 0.11 | 0.60 | 1.07 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 1.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).