1. Introduction

The addition of poly-ADP-ribose molecules to proteins (PARylation) is a post-translational modification in response to DNA damage [

1]. PARylation is carried out by members of the PAR polymerase (PARP) enzyme family [

2]. Removal of ADP-ribose (ADPR) from PARylated proteins is carried out by enzymes such as PAR glycohydrolase (PARG) [

3], ADP ribosylhydrolase 3 (ARH3) [

4,

5] as well as the macro domain (MacroD) containing terminal ADPR protein glycohydrolase 1 (TARG1) [

6].

PARylation plays a role in several DNA repair pathways, possibly by providing a landing point or scaffold for multiple DNA repair factors [

7]. PARP-1 binds to DNA via its zinc-finger domain [

7]. During double strand break repair, PARP-1 is involved in both homologous recombination repair (HR) repair and in non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), the latter both in classical and alternative pathways [

1]. After single strand breaks, PARP-1 is involved in base excision repair (BER), both in short patch repair and in long patch repair. During short-patch repair, PARP-1 binds to the BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminal) domain of XRCC1 (X-ray repair cross-complementing 1) protein [

7]. Via a second BRCT domain, XRCC1 protein is also bound to DNA ligase III [

7].

PARylation is also a central factor in a special form of cell death named parthanatos [

8]. During parthanatos, an early transient hyperactivation of PARylation occurs [

9], which leads to NAD+ and ADP depletion and collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential. After that, PARP-1 is cleaved by caspases which occurs immediately after caspase activation [

10]. Caspase cleavage leads to 24- and 89 kDa fragments of PARP-1 [

11]. The 24 kDa fragment remains bound to DNA lesions whereas the 89 kDa fragment is attached to PAR and – via PAR – to apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) [

11]. In addition to the functions described, PARP-1 can also regulate inflammatory mediators, cellular energetics, gene transcription, mitosis and cellular signaling such as sex hormone and ERK (extracellular signal regulated kinase) signaling [

12].

Due to their role in DNA repair, PARP inhibitors are successfully used in tumor therapy, e.g. in the treatment of breast, ovarian, pancreatic and prostate cancers [

13]. However, a synthetically lethal interaction with the mutation in another DNA repair protein is required, namely mutations in BRCA1/2 (breast cancer growth suppressor protein 1 or 2) which are required for HR [

13]. PARP inhibitors exert their action by PARP trapping at sites of DNA damage with subsequent collapse of the replication forks, disrupted processing of Okazaki fragments, up-regulation of p53 but also increased replication fork speed [

13]. Due to the biologic synergy of PARPi and IR, PARPi act as radiosensitizers [

14,

15].

IR induces and double strand breaks and PARP family members are among the first proteins arriving at the site of damage by binding to DNA via its zinc finger domain [

16]. By acting as a scaffold, PARP attracts other DNA repair proteins. In addition, a number of immediate-early genes are induced as a stress response [

17,

18,

19]. These processes occur during tumor therapy both in tumor and in normal tissue. The affected tissue displays a sterile inflammation which – e.g. in the lung - is called radiation pneumonitis (RP) [

20]. After the acute damage has been repaired, there is usually a gap period where nearly no macroscopic and microscopic changes occur in the tissue. This gap period can take several weeks to years. Then, the phase of chronic radiation damage starts involving destruction of organ-typic cells, endothelial cells and formation of scar tissue. In the lung, this process is called fibrosing alveolitis (FA) with the final result being pulmonary fibrosis (PF), also called radiation fibrosis (RF) [

21]. Several inflammatory mediators, cytokines and growth factors are involved in the lung injury, such as TNFalpha [

22], TGFbeta1 [

23,

24,

25]. Impaired regeneration due to growth factor deficiency has been attempted to be treated with the administration of exogenous growth factors, such as KGF (keratinocyte growth factor) [

26]. Although the gap period shows little changes in lung architecture, signaling pathways seem to deteriorate. In a well-characterized model of IR induced FA, we found a continuous increase in NF-kappaB DNA binding activity reaching its highest level at 12 weeks after IR. When fibrosing alveolitis starts, which takes place around 2 months after irradiation, NF-kappaB activity is sub-maximal [

27]. In contrast, the transcription factors Sp1 and AP-1 lose their DNA binding activity after IR [

28,

29]. At 4.5 weeks after IR, AP-1 starts to lose its DNA binding activity which is completely lost at 5.5 weeks after IR. Thus, 8 weeks after IR, with early FA and submaximal NF-kappaB activity and 12 weeks (3 months) after IR when NF-kappaB levels reach its maximum are critical time points to study molecules that might influence the process of FA.

As mentioned earlier, radiosensitization can be exerted by PARP-1 inhibitors. In this study, we wanted to find out, whether IR may sensitize normal tissue to PARP-inhibition. In the above-mentioned rat model of IR, we found a nearly complete loss of PARP-1 in radiation-damaged lung tissue, a condition that may aggravate tissue damage caused by PARP inhibitors.

2. Materials and Methods

Animal models. For the external irradiation (eIR), the right lungs of female Fischer rats were irradiated with a single dose of 20 Gy IR as described [

29]. These animal experiments have been approved by the animal ethics committee of the State of Saxony (approval number AZ 24-9168.11-1/2014-1). For internal irradiation (iIR), 188Re-microspheres were injected intravenously into adult Wistar rats as described [

30]. These animal experiments were approved by the Gouvernment of Saxony (Approval No. AZ 24-9168.11-1-2004-8). In these experiments, doses up to 54 Gy were applied. Tissue was fixed in 4 % neutrally buffered formaldehyde overnight and subsequently embedded in paraffin or was snap frozen and stored at -80 °C.

Western blotting (WB). Nuclear and crude cytoplasmic protein extracts were prepared as described [

31]. Membrane and organelle (M/O) fractions were prepared by pelleting the crude cytoplasmic fraction at 20,817 x g (14000 rpm) and resuspending the pellet in nuclear extraction buffer. Proteins were separated with denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [

32] and blotted using a semi-dry apparatus (TE77XP, Hoefer, Bridgewater, USA) onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Primary antibodies and their dilutions are listed in the supplementary informations (

Table S1). Secondary antibodies were labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) at a 10-fold dilution compared to the primary antibodies. Luminescence was induced by incubation with Super Signal West Femto substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Erlangen, Germany). Signals were detected on a ChemoCam Imager (INTAS, Göttingen, Germany). Bands were quantified with the programs Labimage 1D (INTAS, Göttingen, Germany) or with ImageJ [

33]. Ponceau S stained PVDF membranes served as loading controls. Molecular weights (MW) of fragments were calculated with Microsoft Excel or Labimage 1D.

Immunohistochemistry (IH) and Immunofluorescence (IF) stainings. Both IH and IF stainings were performed on sections from paraffin-embedded material. The dilutions of the primary antibodies are given in

Table S1. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibodies were used at a concentration of about 5 µg/ml. IH was developed with the Vectastain Elite Kit (Biozol, Eching, Germany) and IF was developed with TSA (Tyramide signal ampflification) Superboost 488 or 594 kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Erlangen, Germany), both according to the manufacturers instructions. IH pictures were obtained with an Axioskop 2 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using the ZEN blue software of the same company. IF pictures were obtained on a Leica SP5 laserscanning microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

4. Discussion

A Due to the important role of PARP-1 in DNA repair, PARP-1 inhibitors are used therapeutically in malignant tumors [

14]. A combination of both PARP-1 inhibition and IR renders tumor cells more susceptible to cell death since unrepaired SSB are converted to DSB when repair is inhibited, e.g. by mutations in BRCA proteins [

14]. In addition, BRCA proteins are down-regulated after a combination of PARP-1 inhibition with Olaparib and radiation [

34]. Yet, PARP-1 inhibition works best in BRCA deficient tumors providing also a selectivity of cell damage in tumors compared to normal tissue. In this study, we asked whether there may be sensitization of irradiated tissue to PARP-1 inhibition in the long run. We used two well-characterized rat models of radiation-induced lung damage [

29,

30], namely eIR and iIR. In both models, there was a strong decrease in FL PARP-1 protein levels after 2 and 3 months (eIR) or about 2.5 months (iIR). The effect was especially strong after eIR reaching a decrease to 0.28 % of the control level corresponding to a more than 350-fold decrease in FL PARP-1 (

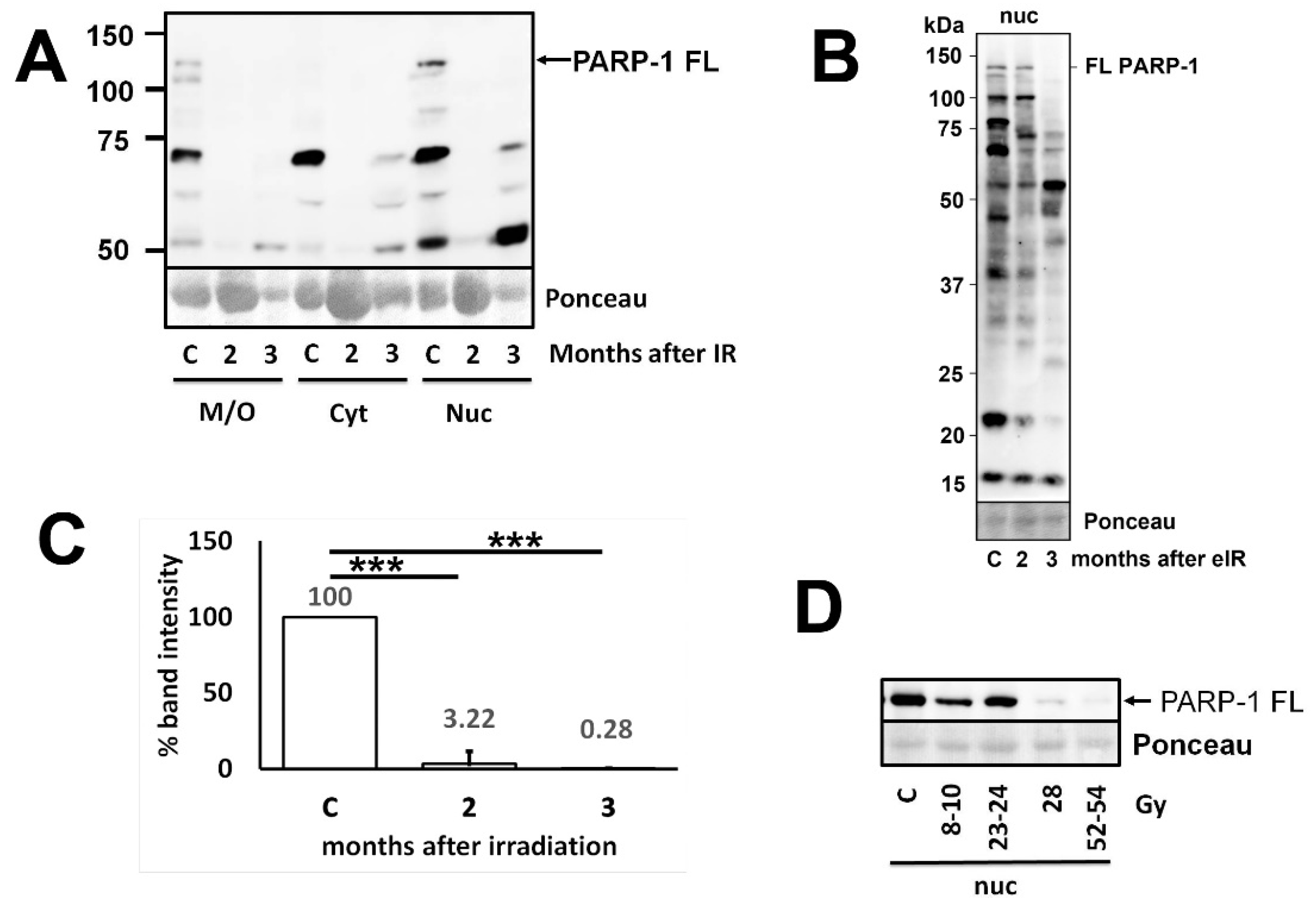

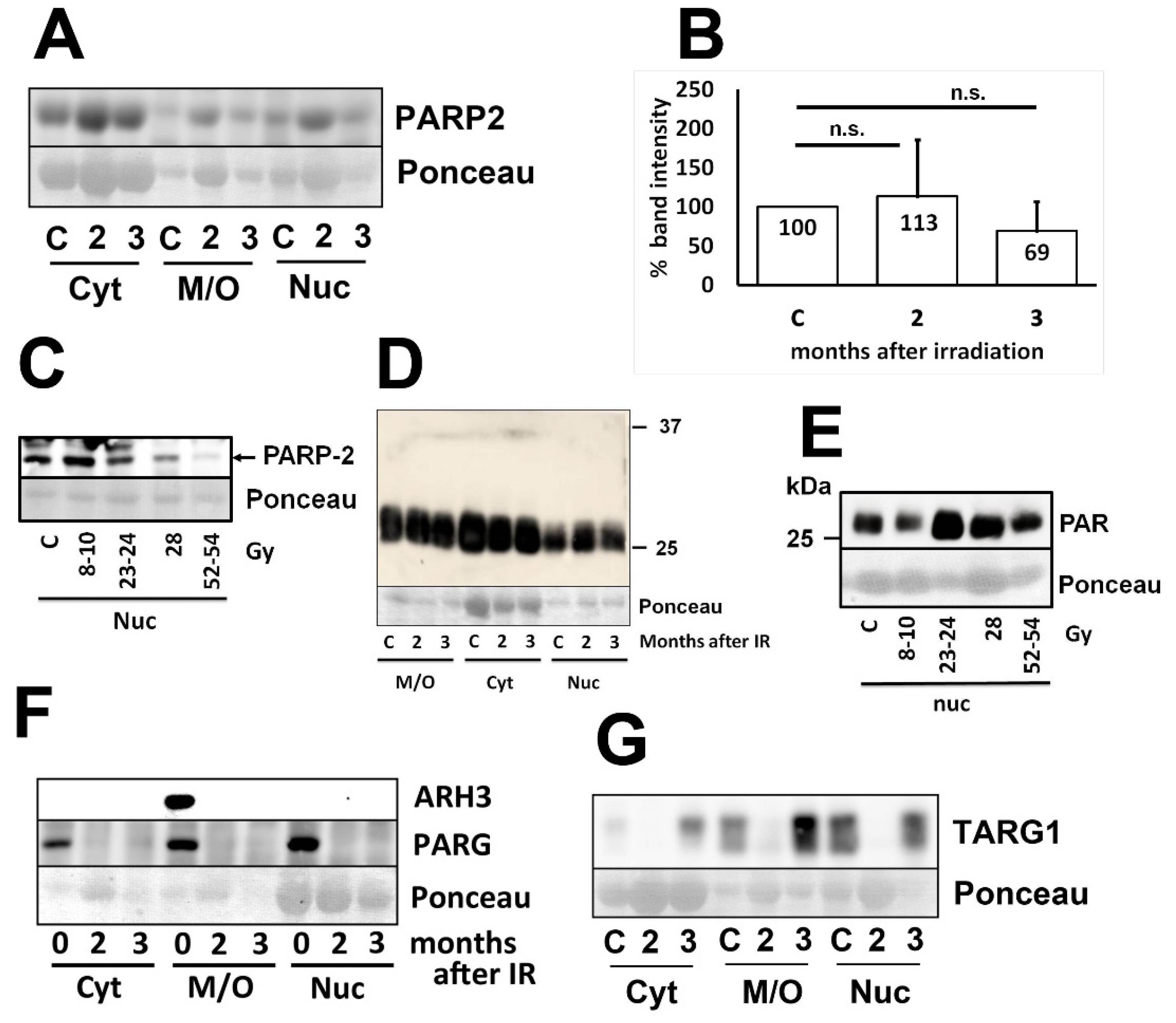

Figure 1). In contrast, PARP-2 levels remained quite constant after eIR and decreased slightly but not significantly after iIR (

Figure 2A,C) which suggests that PARP-2, a protein similar in function and sequence [

2], is unlikely to compensate for the loss of PARP-1 function. However, PARylation remains constant in all cellular fractions and in both models (

Figure 2D,E). These PAR results were in contrast to the expectations. Therefore, we also analyzed the levels of deparylation enzymes. Both ARH3 and PARG are strongly down-regulated in the lung 2 and 3 months after eIR (

Figure 2F) whereas TARG1 is transiently but strongly down-regulated at 2 months after IR (

Figure 2G). Thus, both PARylation and de-PARylation enzymes are down-regulated and thereby explain why total PARylation remains constant. This also means that PARylation looses much of its flexibility. Cellular processes like DNA repair require a quick flexibility to direct PARylation to sites of DNA damage. These data suggest that this “frozen” state of PARylation leads to a severe disturbance of DNA repair, but also to the other functions of PARP mentioned above including inflammation, cellular energetics and mitosis [

12]. Therefore, these data predict the accumulation of DNA damage also months after IR. Since the proteins studied are present in all indigenous lung cells, namely type I and type II pneumocytes and bronchiolar epithelial cells, the data suggest that this disturbance of PARylation takes place in all these cells.

Western blotting revealed that not only FL PARP-1, but also a number of fragments are present in the cells (

Figure 1B). It had been shown that some of these fragments occur under specific conditions and have distinct functions. 85 and 24/25 kDa fragments have been detected in various types of cell death [

35], the latter obviously corresponding to the 26 kDa fragments in our study. During apoptosis, PARP is cleaved by caspase 3 directly [

9]. A 24 kDA N-terminal fragment has been described to bind tightly to DNA, and it has been supposed that this would impair DNA repair [

36]. Indeed, it has been shown that this N-terminal fragment strongly inhibits PARP-1 activity [

36,

37]. In our study, this ~24-26 kDa fragment is increased at 3 months after eIR (

Figure 1B) which is likely to result in even more reduction in PARP-1 activity (and in more reduction in DNA repair). PARP-1 can also be cleaved during necrosis, producing a 50 kDa fragment by the activity of cathepsins [

38]. We see a ~55 kDa band which may correspond to the 50 kDa fragment mentioned which is somewhat increased at 3 months after IR (

Figure 1B). Thus, the increased ~55 kDa band 3 months after IR may be caused by an increased activity of cathepsins.

Taken together, we demonstrate a strong decrease in PARylation and dePARylation enzymes in the rat lung at 2 and 3 months after irradiation, a condition which should correspond to a severe disturbance in all PARylation dependent processes, most importantly DNA repair. Thus, radiation damage of normal tissue may interfere with side effects of therapies with PARP-1 inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Western blots showing loss of PARP-1 in lung after eIR and iIR. A: Representative experiment showing the expression of full length (FL) PARP-1 protein as well as some of its fragments in different cellular compartments of the lung after external irradiation (eIR) at 2 and 3 months after IR (M/O, membrane/organelles; C, cytoplasm; N, nucleus). B: Blot of nuclear PARP-1 showing fragments down to 15 kDa size in lung tissue after eIR. C: Quantification of nuclear PARP-1 of eight independent experiments of eIR. D: Repesentative western blot showing loss of PARP-1-FL after iIR at or above doses of 28 Gy.

Figure 1.

Western blots showing loss of PARP-1 in lung after eIR and iIR. A: Representative experiment showing the expression of full length (FL) PARP-1 protein as well as some of its fragments in different cellular compartments of the lung after external irradiation (eIR) at 2 and 3 months after IR (M/O, membrane/organelles; C, cytoplasm; N, nucleus). B: Blot of nuclear PARP-1 showing fragments down to 15 kDa size in lung tissue after eIR. C: Quantification of nuclear PARP-1 of eight independent experiments of eIR. D: Repesentative western blot showing loss of PARP-1-FL after iIR at or above doses of 28 Gy.

Figure 2.

Western blots of lung tissue showing PARP-2 and PAR as well as different deparylating enzymes after IR. A: Expression of PARP2 protein in different cellular fractions of the lung after eIR together with the quantification diagram (B) demonstrating no significant (n.s.) changes. C: Slight but not significant reduction of PARP2 after iIR. D, E: No major changes in PARylated protein both after eIR (D) and iIR (E). F: Strong reduction in the deparylating enzymes ARH3 and PARG after eIR. G: Transient reduction of the deparylating enzyme TARG1 after eIR.

Figure 2.

Western blots of lung tissue showing PARP-2 and PAR as well as different deparylating enzymes after IR. A: Expression of PARP2 protein in different cellular fractions of the lung after eIR together with the quantification diagram (B) demonstrating no significant (n.s.) changes. C: Slight but not significant reduction of PARP2 after iIR. D, E: No major changes in PARylated protein both after eIR (D) and iIR (E). F: Strong reduction in the deparylating enzymes ARH3 and PARG after eIR. G: Transient reduction of the deparylating enzyme TARG1 after eIR.

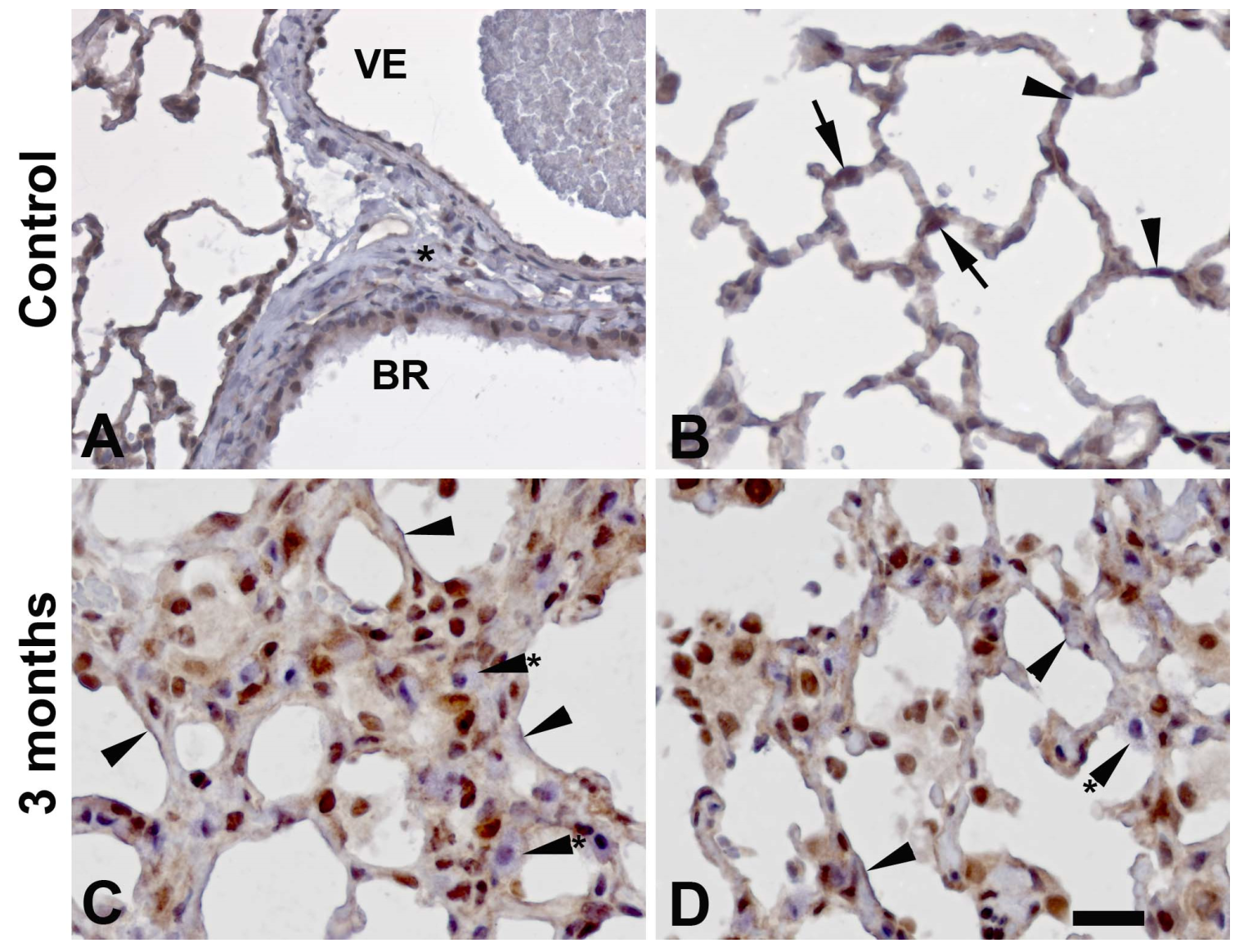

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry stainings demonstrating the distribution of PARP-1 protein in the control rat lung (A, B) and in rat lung 3 months after eIR (C, D). Staining is predominantly nuclear, especially in the irradiated lungs. Type II pneumocytes display strong to very strong staining (arrows) whereas staining in type I pneumocytes (arrwoheads) is weak to moderate. Mast cells (arrowheads with asterix) are usually negative. Venules (VE) show strong or very strong staining (cells are very flat), whereas bronchioles show a weak to moderate staining intensity. In the connective surrounding vessels or bronchioles, only few cells are weakly positive. Bar is 20 µm in A, B and 10 µm in C, D.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry stainings demonstrating the distribution of PARP-1 protein in the control rat lung (A, B) and in rat lung 3 months after eIR (C, D). Staining is predominantly nuclear, especially in the irradiated lungs. Type II pneumocytes display strong to very strong staining (arrows) whereas staining in type I pneumocytes (arrwoheads) is weak to moderate. Mast cells (arrowheads with asterix) are usually negative. Venules (VE) show strong or very strong staining (cells are very flat), whereas bronchioles show a weak to moderate staining intensity. In the connective surrounding vessels or bronchioles, only few cells are weakly positive. Bar is 20 µm in A, B and 10 µm in C, D.

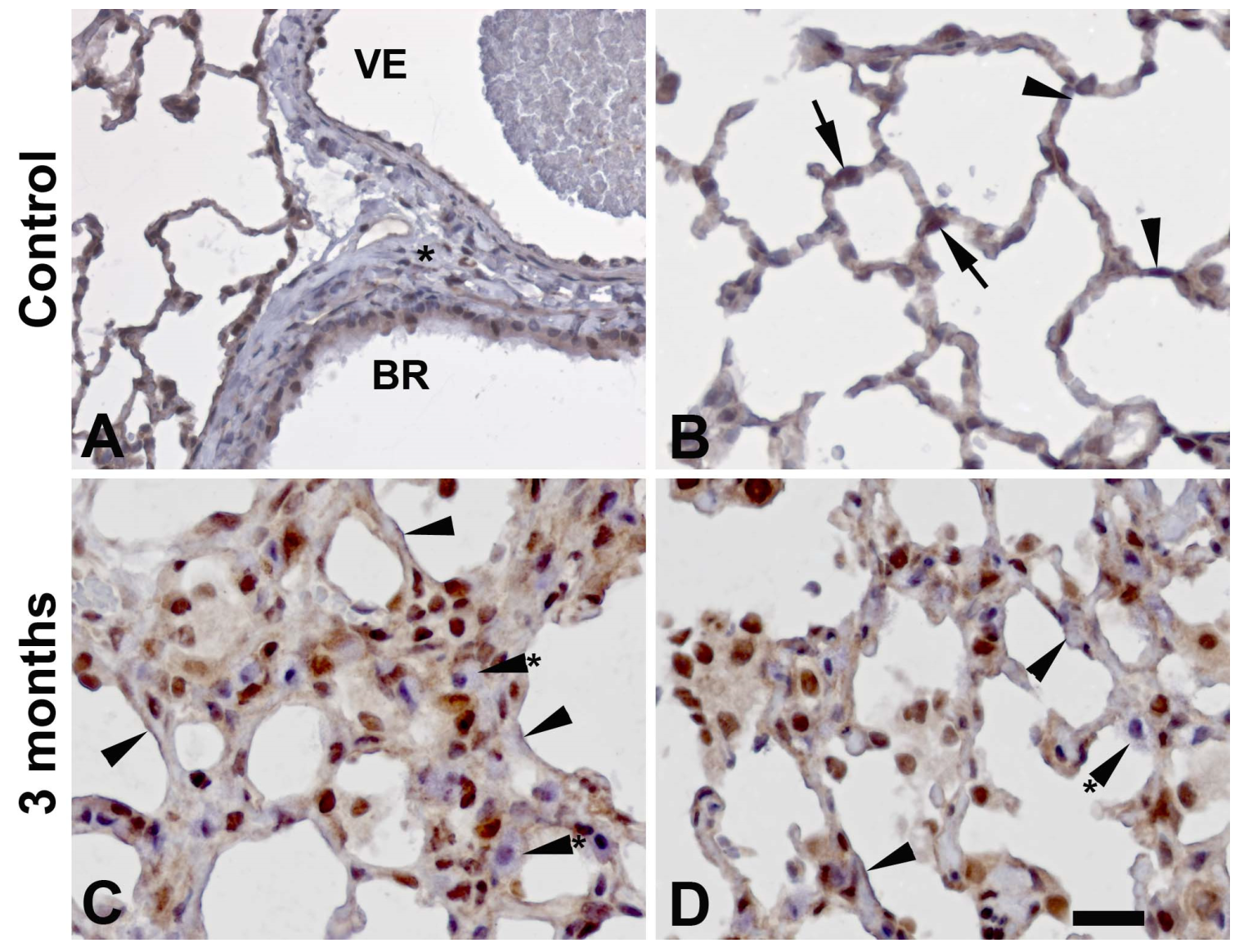

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry stainings demonstrating the distribution of PARP-2 protein in the control rat lung (A, B) and in rat lung 3 months after eIR (C, D). Arrows point at positive type II pneumocytes and arrowheads to type I pneumocytes. Arrowheads with asterix point at alveolar macrophages which are moderately to strongly stained. Bronchiolar epithelium (BR) is also moderately to strongly stained whereas endothelial cells of venules (VE) are weakly stained. Bar is 20 µm in A, B and 10 µm in C, D.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry stainings demonstrating the distribution of PARP-2 protein in the control rat lung (A, B) and in rat lung 3 months after eIR (C, D). Arrows point at positive type II pneumocytes and arrowheads to type I pneumocytes. Arrowheads with asterix point at alveolar macrophages which are moderately to strongly stained. Bronchiolar epithelium (BR) is also moderately to strongly stained whereas endothelial cells of venules (VE) are weakly stained. Bar is 20 µm in A, B and 10 µm in C, D.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry stainings demonstrating the distribution of PAR in the control rat lung (A, B) and in rat lung 3 months after eIR (C-F). Arrows point at type II pneumocytes, arrowheads at type I pneumocytes. Bronchioli (BR) are moderately to strongly stained. The endothelium of blood vessels such as venules (VE) is also moderately stained. Cells in the alveolar walls containing granular or foamy cytoplasm (arrowheads with asterix) probably represent tissue residing macrophages. Bar is 20 µm in A, B and 10 µm in C-F.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry stainings demonstrating the distribution of PAR in the control rat lung (A, B) and in rat lung 3 months after eIR (C-F). Arrows point at type II pneumocytes, arrowheads at type I pneumocytes. Bronchioli (BR) are moderately to strongly stained. The endothelium of blood vessels such as venules (VE) is also moderately stained. Cells in the alveolar walls containing granular or foamy cytoplasm (arrowheads with asterix) probably represent tissue residing macrophages. Bar is 20 µm in A, B and 10 µm in C-F.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence double-labelling of SFTPC, a marker of type II pneumocytes, and PARP-1 (A-C) as well as PAR (D-F) in rat lungs. A-C: Most of the type II pneumocytes contain PARP-1 (arrwos), but there are some type II pneumocytes which are PARP-1 negative (arrowheads). PAR is expressed as a thin line on the surface of alveoli, but also at the surface of type II pneumoytes (arrows, such the cell in the center). Bar corresponds to 50 µm.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence double-labelling of SFTPC, a marker of type II pneumocytes, and PARP-1 (A-C) as well as PAR (D-F) in rat lungs. A-C: Most of the type II pneumocytes contain PARP-1 (arrwos), but there are some type II pneumocytes which are PARP-1 negative (arrowheads). PAR is expressed as a thin line on the surface of alveoli, but also at the surface of type II pneumoytes (arrows, such the cell in the center). Bar corresponds to 50 µm.

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescence double-labelling of PAR with aquaporin 5 (Aqp5), a marker of type I pneumocytes (A-C) and with CD68, a marker of macrophages (D-F). A-C: The surface of the alveoli is labelled by both PAR (arrowheads) and Aqp5 (arrowheads with asterix), but in a mutually exclusive way. D-F: Macrophages (arrows) are mostly PAR negative or very weakly positive (arrowheads), but there are also some PAR positive macrophages as for example the cell above the cell labelled with an arrow. Bar corresponds to 50 µm.

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescence double-labelling of PAR with aquaporin 5 (Aqp5), a marker of type I pneumocytes (A-C) and with CD68, a marker of macrophages (D-F). A-C: The surface of the alveoli is labelled by both PAR (arrowheads) and Aqp5 (arrowheads with asterix), but in a mutually exclusive way. D-F: Macrophages (arrows) are mostly PAR negative or very weakly positive (arrowheads), but there are also some PAR positive macrophages as for example the cell above the cell labelled with an arrow. Bar corresponds to 50 µm.

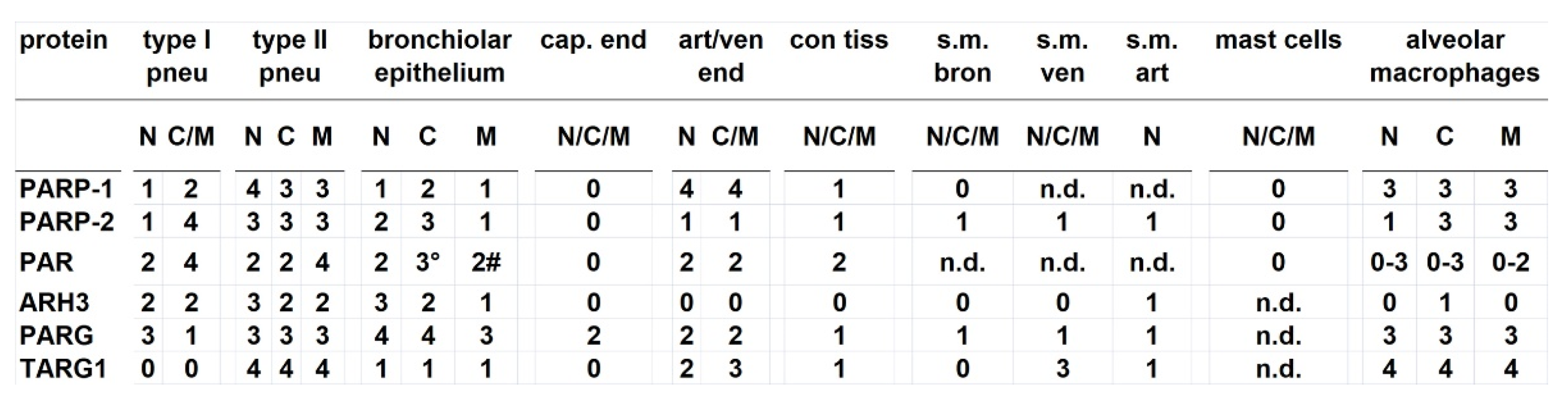

Table 1.

Expression pattern of PARylation related proteins in the rat lung.

Compartments: N, nuclear, C, cytoplasmic, M, membrane or organelles; °, retronuclear; #, apical. Staining intensity: 0, not detectable; 1, weak or rare staining; 2, medium staining; 3, strong staining; 4, very strong staining. Abbreviations for the cell types: art, arteriole; bron, bronchiolar; cap, capillary; con, connective; endo, endothelium; m, muscle; pneu, pneumocytes; s.m., smooth muscle; tiss, tissue; ven, venule.

Table 1.

Expression pattern of PARylation related proteins in the rat lung.

Compartments: N, nuclear, C, cytoplasmic, M, membrane or organelles; °, retronuclear; #, apical. Staining intensity: 0, not detectable; 1, weak or rare staining; 2, medium staining; 3, strong staining; 4, very strong staining. Abbreviations for the cell types: art, arteriole; bron, bronchiolar; cap, capillary; con, connective; endo, endothelium; m, muscle; pneu, pneumocytes; s.m., smooth muscle; tiss, tissue; ven, venule.