1. Introduction

Acute immunologic reactions, including angioedema and allergic reactions, can cause alterations in the coagulation system.[

1,

2] Prior data from our study group indicate that the severity of immunologic reactions is related to the extent of maximum lysis (ML) measured by thromboelastography.[

3] More severe conditions are associated with higher ML in the extrinsic survey of ROTEM (EXTEM).[

3] In the aprotinin assay (APTEM), aprotinin is added to block fibrinolytic enzymes, allowing the clinician to distinguish true fibrinolysis from other processes and artifacts.[

4] The possible mechanisms behind the connection between fibrinolysis and immunologic conditions are described in detail in our primary publication.[

3]

Guidelines suggest monitoring patients with acute immunologic reactions for up to 8 hours.[

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] The reason behind this recommendation is that multiphasic reactions might occur.[

6] The latter implies that a patient’s clinical condition initially improves but afterward worsens again.[

6] In this context, there seems to be no proven connection between the severity of an immunologic reaction and the time a patient needs to recover fully.[

10] In this context, individuals with severe conditions might recover fast and permanently, while patients with light symptoms might need more time and encounter clinical setbacks, and vice versa.[

10] To optimize resource allocation, objective parameters that help to identify those with an increased risk of persistent or recurrent symptoms would be helpful. Clinical consequences may include close monitoring and readiness to re-administer treatment.

Blood lactate and tryptase levels are objective parameters of the severity of an immunologic reaction.[

6,

7,

11,

12] However, the latter are time- and resource-intensive to obtain, making them rather unsuitable for use under emergency circumstances. Thromboelastography assays, such as ROTEM, on the other hand, are point-of-care tests, relatively easy to perform, and available in many emergency and intensive care settings worldwide.[

13,

14,

15] Combining a patient’s clinical gestalt and thromboelastography might add valuable information for further management.

As far as we are informed, no clinical studies have investigated the dynamics of fibrinolysis using thromboelastography from presentation to follow-up in patients with acute immunologic reactions.

We aimed to investigate whether the thromboelastography results of emergency department patients with acute immunologic reactions who are still symptomatic after observation over two hours differ from those who are asymptomatic. Furthermore, we aim to investigate the association between the findings of thromboelastography at presentation and follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

This study analyzes the follow-up data of a patient population investigated in a prior prospective survey.[

3] All adult patients (>18 years of age) presenting to our academic emergency department due to acute immunologic reactions between July 2021 and April 2023 were offered to participate in the study if resources were available. Using a ROTEM

® Delta device (Werfen GmbH, Munich, Germany), study team members performed EXTEM and APTEM assays at presentation and approximately 2 hours thereafter. Details about thromboelastography's function and measurement technique can be found in our previously published work.[

3]

Clinically, we prospectively assessed immunologic symptoms at presentation, grading them as mild or severe, as described in our previous publication.[

3] At follow-up, we classified patients as symptomatic or asymptomatic. All patient records were screened by the same physician to ensure that the patients met the inclusion criteria and to check for consistency.

2.1. Primary Analysis

We compared EXTEM ML between patients with and without symptoms at follow-up 2 hours after presentation to the emergency department.

2.2. Sensitivity Analysis

Finally, to test the assumption that our findings from EXTEM were duly related to alterations in the coagulation cascade, we investigated ML in APTEM at follow-up between patients with and without persistent symptoms.

We used the nonparametric equality-of-medians test for all comparisons. We present median values as well as interquartile ranges (IQR) for the groups as well as p-values for the comparisons. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 is considered statistically significant. We utilized MS Excel 16.82 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) for data management and Stata SE 18.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) for calculations. The STROBE statement for this manuscript can be found in Supplement 1.[

16]

3. Results

Of the 31 patients included in the initial survey, 16 (10 (63%) female, mean age 50±14 years) individuals underwent follow-up. Of these, 6 (38%) were still symptomatic at follow-up.

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population.

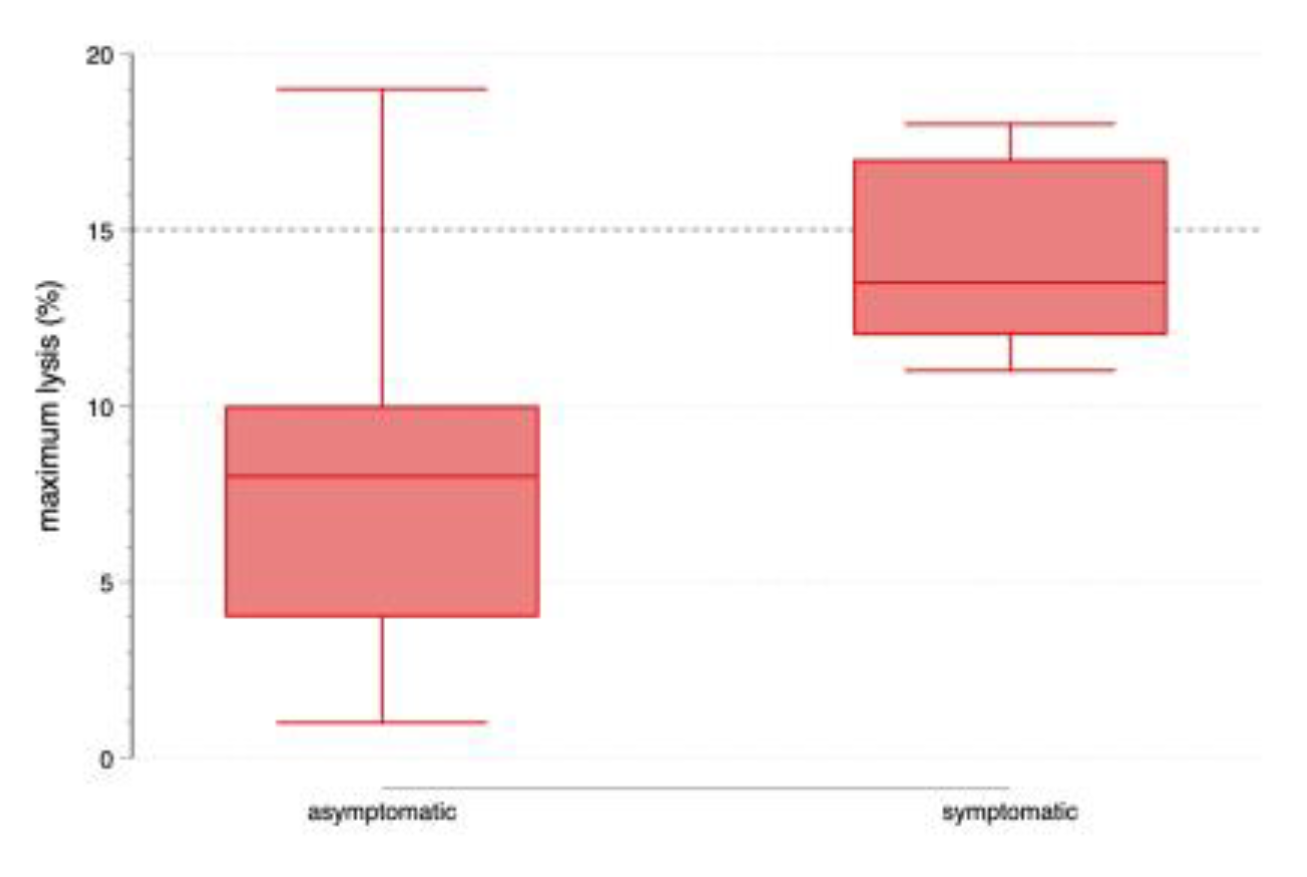

3.1. Primary Analysis

Patients who were still symptomatic at follow-up had significantly higher ML in the EXTEM assay than those who were asymptomatic (14% (IQR 12-17) vs. 8% (IQR 4-10), respectively, p=0.002). (see

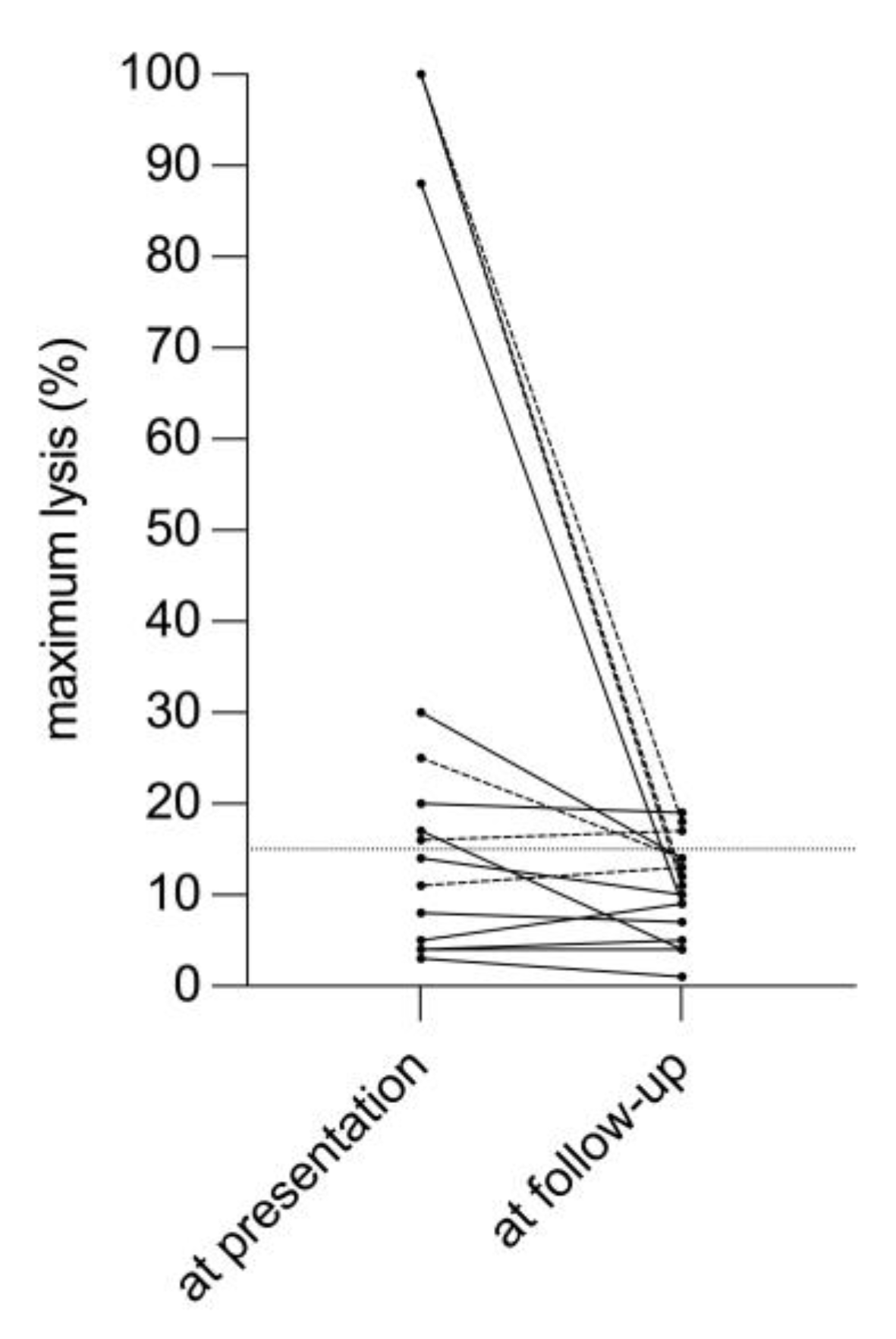

Figure 1) The dynamics of EXTEM ML from presentation to follow-up are displayed in

Figure 2.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

We did not detect a significant difference regarding ML in APTEM between patients with (12% (IQR 11-15)) and without persistent symptoms (9% (IQR 5-13), p=0.152).

Figure S1 shows ML at follow-up before and after inhibition of fibrinolysis with aprotinin.

4. Discussion

Our data suggest that thromboelastography reveals altered ML in patients with immunologic reactions who are still symptomatic two hours after presentation to the emergency department.

Many authors define hyperfibrinolysis as an ML>15%, which is reversed by adding aprotinin (i.e., an APTEM assay).[

4] To answer our study question, we did not take any formal definition of fibrinolysis into account. Only 3 of our patients had ML values slightly over 15%. Of these, 2 had persistent symptoms. However, ML measured with EXTEM was likely close enough to the normal range for the APTEM not to cause any further decreases. Nevertheless, our findings might be interesting: The release of tPA from the activated endothelium might be subtle but still detectable. In this context, one must keep in mind that the thromboelastography thresholds were originally tailored to the acutely bleeding trauma patient, where massive thrombolysis might occur. None of the individuals we included had any signs of inner or outer bleeding, which is seen in very severe or lethal cases.[

17] We believe that the conventional cutoffs of thromboelastography do not apply to our cohort of interest, where the assay is still experimental.

Our study has several limitations. One might argue that our sample size is relatively small, which is a valid concern. We initially aimed to control for covariates, including age and gender, in regression models but were unable to do so given the few patients included. However, in consideration of up-to-date literature, our cohort is comparably large. Data on the topic are generally scarce.

5. Conclusions

Patients with persistent immunologic reactions continue to have higher maximum lysis on thromboelastography than asymptomatic individuals a few hours after presentation to the emergency department.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Maximum lysis in ROTEM before (extrinsic test (EXTEM)) and after inhibition of fibrinolysis using aprotinin (aprotinin test (APTEM)). Dashed lines refer to patients with persisting symptoms at follow-up.; Table S1: STROBE statement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K., C.S., G.R., C.H. and H.H.; methodology, C.K., C.S., G.R., B.J., M.S. and H.H.; software, C.K.; validation, C.K., C.S., G.R., J.G., C.H., B.J., M.S. and H.H.; formal analysis, C.K.; investigation, C.K., C.S., G.R., J.G., C.H., B.J., M.S. and H.H.; resources, C.K., C.S., G.R., J.G. and C.H.; data curation, C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K.; writing—review and editing, C.S., G.R., J.G., C.H., B.J., M.S. and H.H.; visualization, C.K.; supervision, C.K., C.S. and H.H.; project administration, C.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (protocol code #1696/2020, 6. November 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Initial informed consent was waived in patients with markedly reduced consciousness.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethics committee regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mazzi, G.; Raineri, A.; Lacava, E.; De Roia, D.; Santarossa, L.; Orazi, B.M. Primary hyperfibrinogenolysis in a patient with anaphylactic shock. Haematologica 1994, 79, 283-285.

- Iqbal, A.; Morton, C.; Kong, K.-L. Fibrinolysis during anaphylaxis, and its spontaneous resolution, as demonstrated by thromboelastography. Br J Anaesth 2010, 105, 168-171. [CrossRef]

- Kienbacher, C.L.; Schoergenhofer, C.; Ruzicka, G.; Grafeneder, J.; Hufnagl, C.; Jilma, B.; Schwameis, M.; Herkner, H. Thromboelastography in acute immunologic reactions. A prospective pilot study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2024, 102425. [CrossRef]

- Longstaff, C. Measuring fibrinolysis: from research to routine diagnostic assays. J Thromb Haemost 2018, 16, 652-662. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.A.; Cremonesi, P.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Hollingsworth, J. Angioedema in the emergency department: a practical guide to differential diagnosis and management. Int J Emerg Med 2017, 10, 15-15. [CrossRef]

- Muraro, A.; Worm, M.; Alviani, C.; Cardona, V.; DunnGalvin, A.; Garvey, L.H.; Riggioni, C.; de Silva, D.; Angier, E.; Arasi, S.; et al. EAACI guidelines: Anaphylaxis (2021 update). Allergy 2022, 77, 357-377. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Anaphylaxis: assessment to confirm an anaphylactic episode and the decision to refer after emergency treatment for a suspected anaphylactic episode. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg134/documents/anaphylaxis-full-guideline2 (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Reese, I.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Beyer, K.; Fuchs, T.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; Klimek, L.; Lepp, U.; Niggemann, B.; Saloga, J.; Schäfer, C.; et al. German guideline for the management of adverse reactions to ingested histamine. Allergo Journal International 2017, 26, 72-79. [CrossRef]

- Simons, F.E.R.; Ardusso, L.R.F.; Bilò, M.B.; El-Gamal, Y.M.; Ledford, D.K.; Ring, J.; Sanchez-Borges, M.; Senna, G.E.; Sheikh, A.; Thong, B.Y.; et al. World Allergy Organization guidelines for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J 2011, 4, 13-37. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.F. The post-anaphylaxis dilemma: how long is long enough to observe a patient after resolution of symptoms? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2008, 8, 45-48. [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.Y.; Schwartz, L.B.; Curry, A.; Pesola, G.R.; Knight, R.J.; Lee, H.-S.; Bakalchuk, L.; Tenenbaum, C.; Westfal, R.E. Histamine and tryptase levels in patients with acute allergic reactions: an emergency department–based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000, 106, 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.B.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Miller, J.S.; Earl, H.; Sullivan, T. Tryptase levels as an indicator of mast-cell activation in systemic anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. N Engl J Med 1987, 316, 1622-1626. [CrossRef]

- Werfen. ROTEM® delta. Available online: https://www.werfen.com/na/en/coagulation-testing-rotem-delta (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Kuiper, G.J.; Kleinegris, M.C.; van Oerle, R.; Spronk, H.M.; Lancé, M.D.; Ten Cate, H.; Henskens, Y.M. Validation of a modified thromboelastometry approach to detect changes in fibrinolytic activity. Thromb J 2016, 14, 1. [CrossRef]

- Spiel, A.O.; Mayr, F.B.; Firbas, C.; Quehenberger, P.; Jilma, B. Validation of rotation thrombelastography in a model of systemic activation of fibrinolysis and coagulation in humans. J Thromb Haemost 2006, 4, 411-416. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008, 61, 344-349. [CrossRef]

- Gelbenegger, G.; Buchtele, N.; Schoergenhofer, C.; Grafeneder, J.; Schwameis, M.; Schellongowski, P.; Denk, W.; Jilma, B. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in anaphylaxis. Semin Thromb Hemost 2023, 569-579. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).