Submitted:

23 August 2024

Posted:

26 August 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aphid Handling and RNA Preparation

2.2. cDNA Library Preparation, Cluster Generation and Sequencing

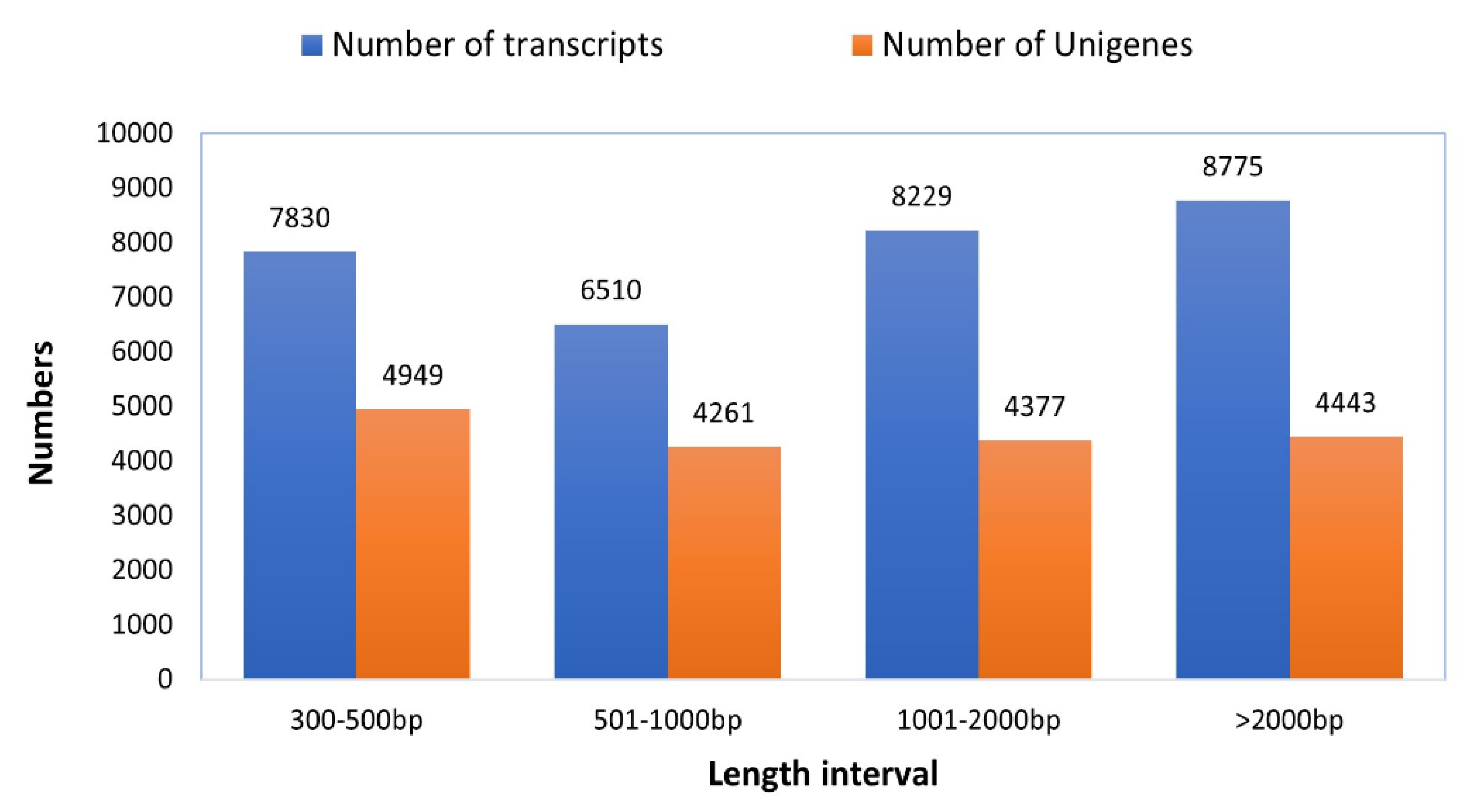

2.3. Quality Control, Transcriptome Assembly, and Gene Annotation

2.4. Prediction of Secretory Proteins

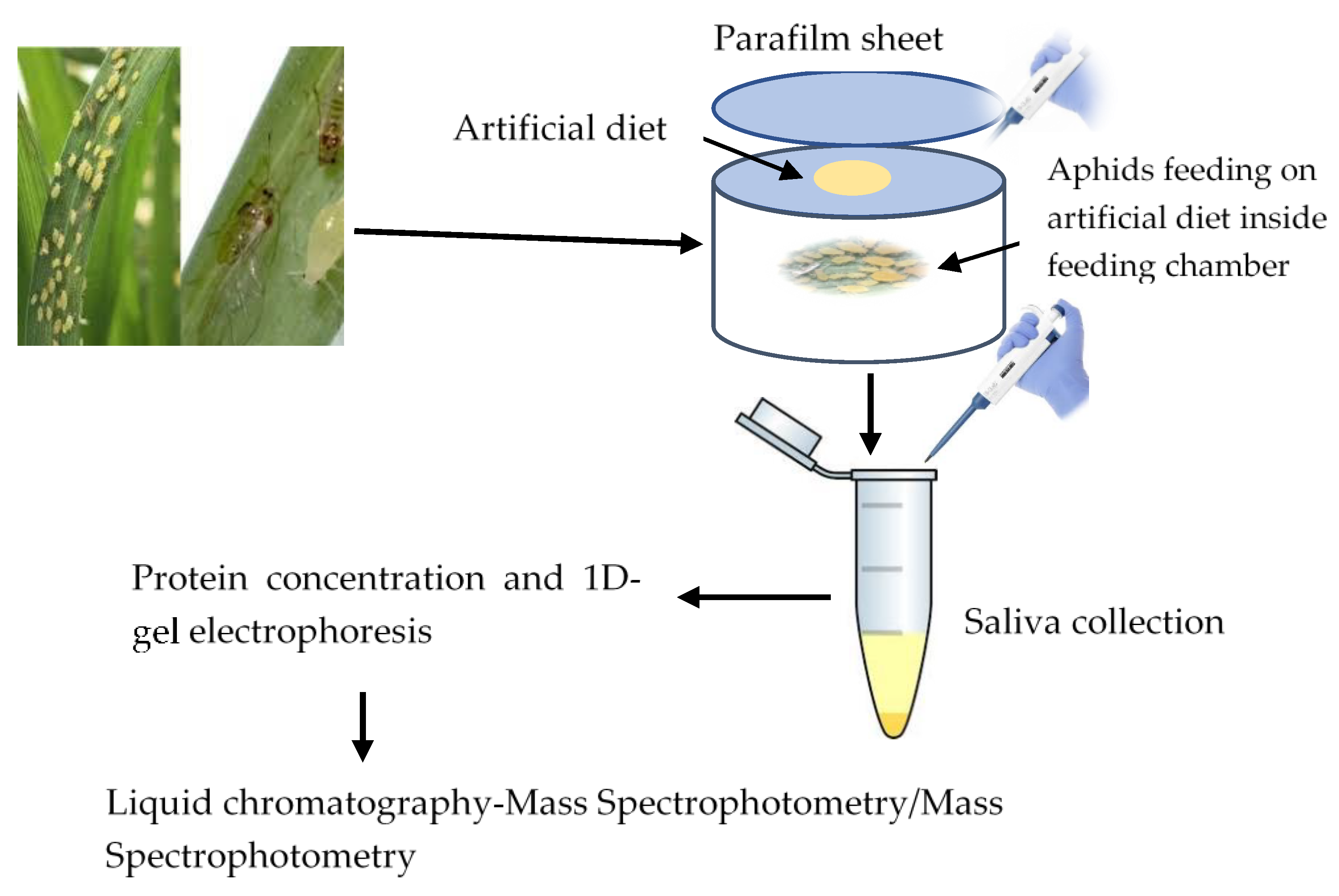

2.5. Saliva Collection, Extraction and Protein Identification

2.5.1. Saliva Collection and Extraction

2.5.2. Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

2.5.3. Proteomic Data Analysis and Similarity Search

3. Results

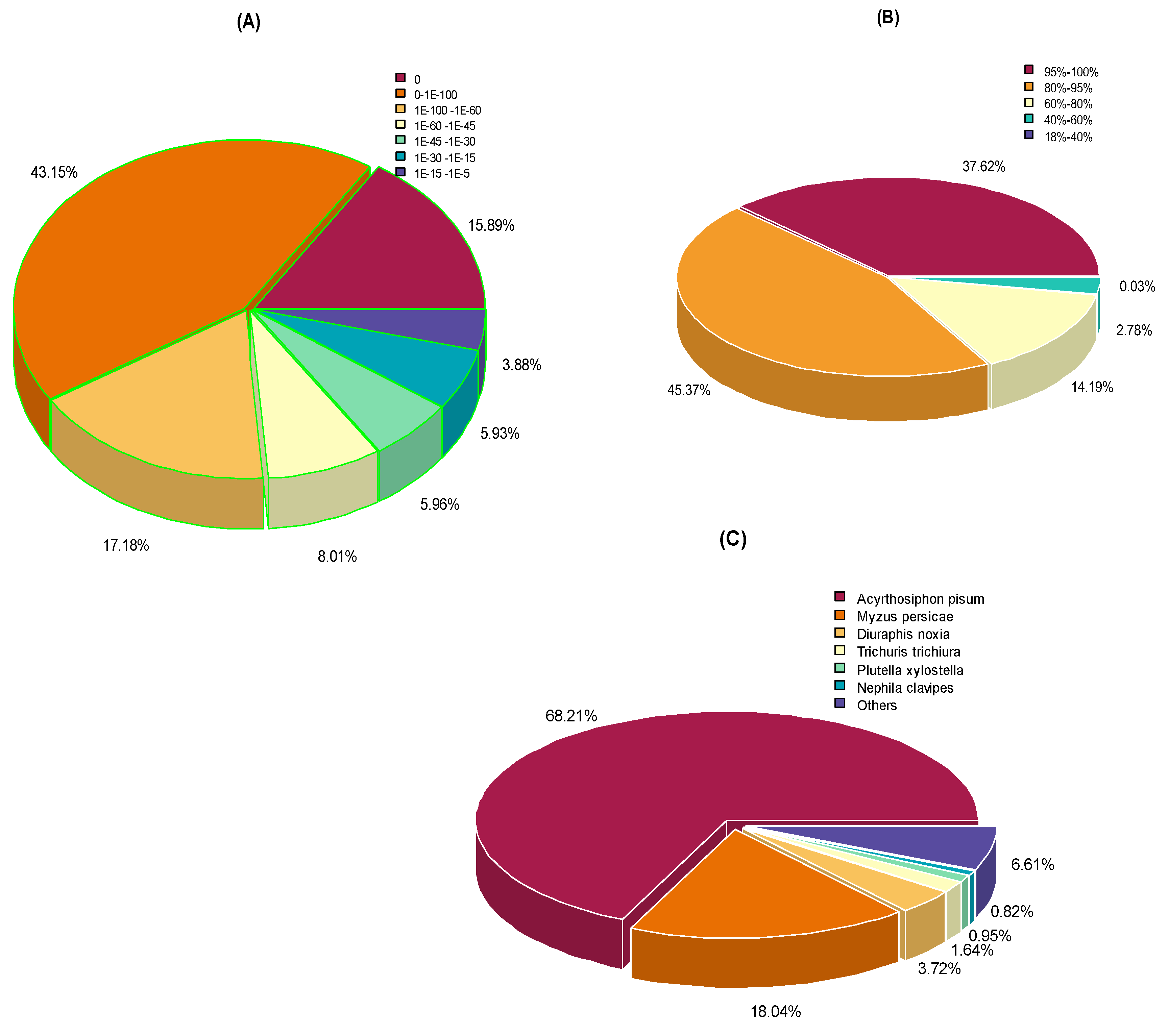

3.1. Functional Annotation of Gene Transcripts

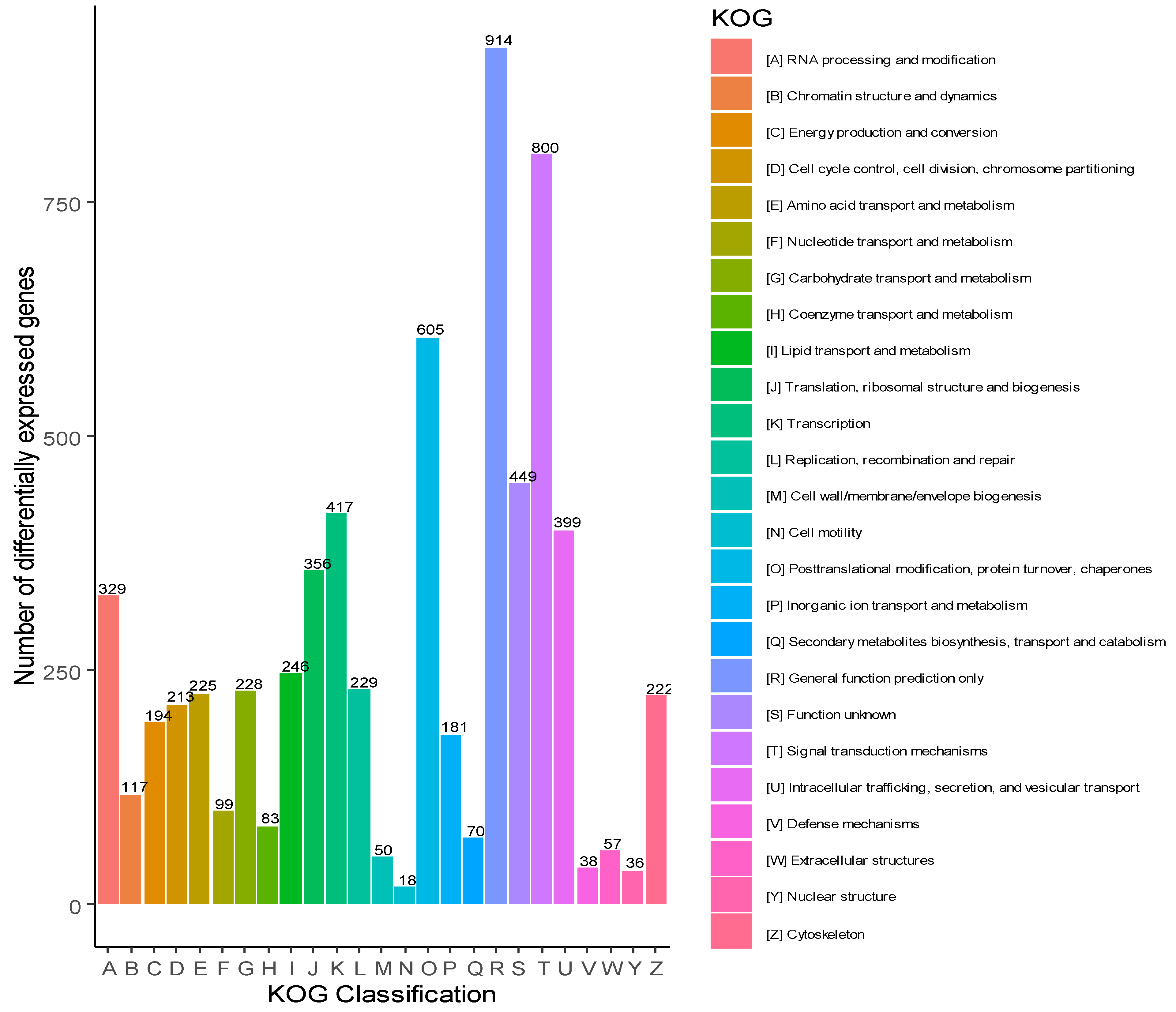

3.2. Gene Ontology and Eukaryotic Orthologous Groups classification (KOG)

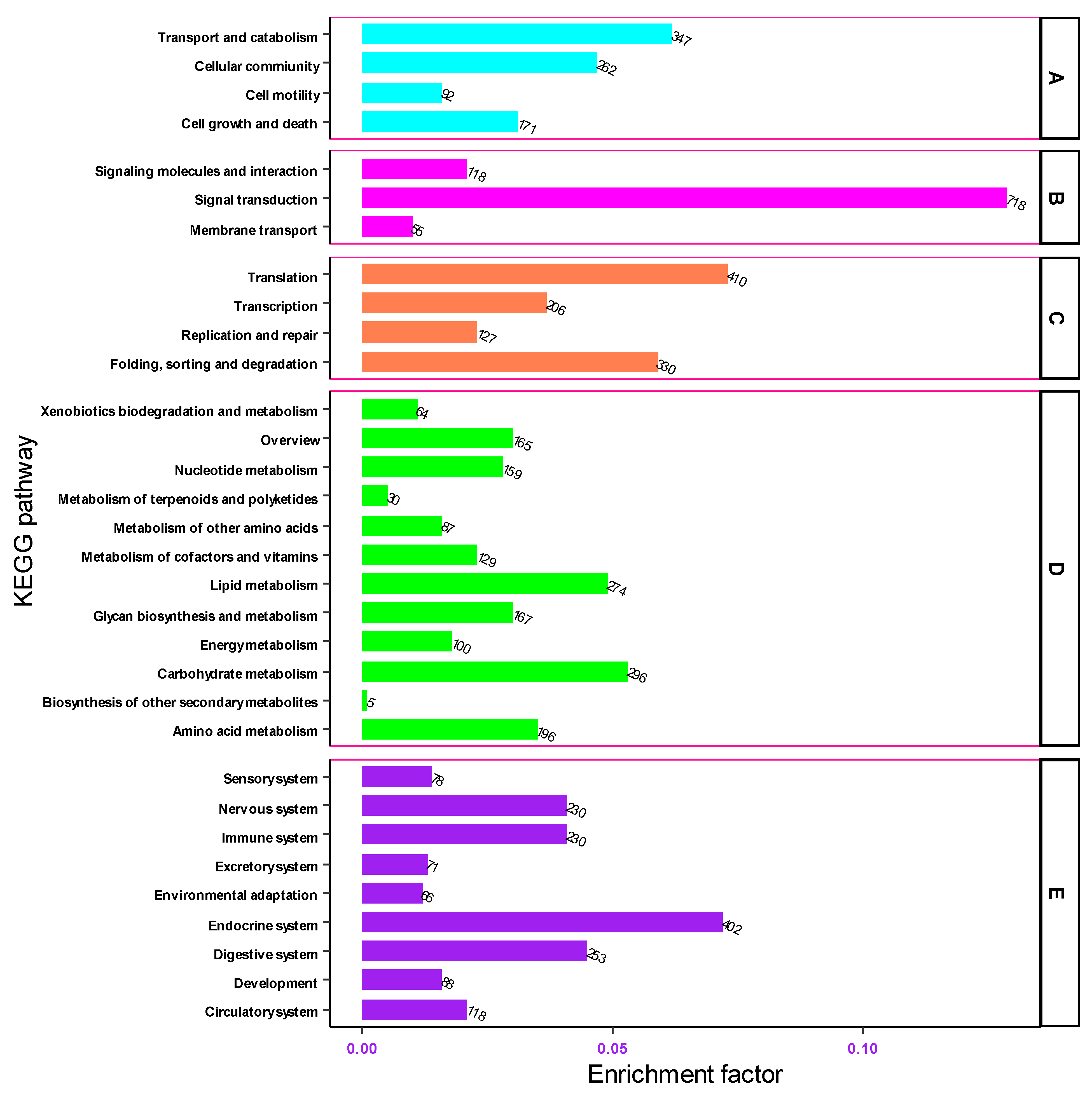

3.3. Metabolic Pathway Analysis by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

3.4. Prediction of Secretory Proteins

3.5. Salivary Proteins and Sequence Similarity among Aphid Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Putative Effectors

4.2. Detoxifying Secretory Proteins

4.3. Digestive Secretory Proteins

4.4. Ca2+ Binding Secretory Proteins

4.5. Zn-Binding Secretory Proteins

4.6. Reproduction and Development

4.7. Protein Synthesis and Secretion

4.8. Odorant Binding and Chemosensory Proteins

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

Supplementary Materials

Funding

References

- Stoletzki, N.; Eyre-Walker, A. The positive correlation between dN/dS and dS in mammals is due to runs of adjacent substitutions. Mol Biol Evol 2011, 28, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. Aphids on the world's crops. An identification and information guide. 2001.

- International Aphid Genomics Consortium. Genome Sequence of the Pea Aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS Biology 2010, 8, e1000313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favret, C.; Normandin, É.; Cloutier, L. The Ouellet-Robert Entomological Collection: new electronic resources and perspectives. The Canadian Entomologist 2019, 151, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, R.; Eastop, V. Aphids on the world herbaceous plants and shrubs: An identification and information guide. 2006.

- Harmel, N.; Létocart, E.; Cherqui, A.; Giordanengo, P.; Mazzucchelli, G.; Guillonneau, F.; De Pauw, E.; Haubruge, E.; Francis, F. Identification of aphid salivary proteins: a proteomic investigation of Myzus persicae. Insect molecular biology 2008, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, R.; Liu, Q.; Lu, J.; Qiao, G.; Huang, X. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses provide insights into host adaptation of a bamboo-feeding aphid. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggin, F.L. Plant–aphid interactions: molecular and ecological perspectives. Current opinion in plant biology 2007, 10, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carolan, J.C.; Caragea, D.; Reardon, K.T.; Mutti, N.S.; Dittmer, N.; Pappan, K.; Cui, F.; Castaneto, M.; Poulain, J.; Dossat, C. Predicted effector molecules in the salivary secretome of the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum): a dual transcriptomic/proteomic approach. Journal of proteome research 2011, 10, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogenhout, S.A.; Bos, J.I. Effector proteins that modulate plant--insect interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2011, 14, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Wang, W.; Luo, L.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Cui, F. Characterization of an aphid-specific, cysteine-rich protein enriched in salivary glands. Biophys Chem 2014, 189, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chandrasekar, R.; Luo, L.; Hiromasa, Y.; Sheng, C.; Peng, G.; Chen, S.; Tomich, J.M.; et al. Armet is an effector protein mediating aphid-plant interactions. Faseb j 2015, 29, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Luo, L.; Lu, H.; Chen, S.; Kang, L.; Cui, F. Angiotensin-converting enzymes modulate aphid-plant interactions. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Khan, A.; Subrahmanyam, S.; Raman, A.; Taylor, G.; Fletcher, M. Salivary proteins of plant-feeding hemipteroids–implication in phytophagy. Bulletin of entomological research 2014, 104, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamian, H.S.; Chaudhary, R.; Cin, V.D.; Bao, E.; Girke, T.; Kaloshian, I. In planta expression or delivery of potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae effectors Me10 and Me23 enhances aphid fecundity. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2013, 26, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.I.; Prince, D.; Pitino, M.; Maffei, M.E.; Win, J.; Hogenhout, S.A. A functional genomics approach identifies candidate effectors from the aphid species Myzus persicae (green peach aphid). PLoS genetics 2010, 6, e1001216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzinga, D.A.; De Vos, M.; Jander, G. Suppression of plant defenses by a Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) salivary effector protein. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2014, 27, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitino, M.; Hogenhout, S.A. Aphid protein effectors promote aphid colonization in a plant species-specific manner. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2013, 26, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, J.I.; Armstrong, M.R.; Gilroy, E.M.; Boevink, P.C.; Hein, I.; Taylor, R.M.; Zhendong, T.; Engelhardt, S.; Vetukuri, R.R.; Harrower, B.; et al. Phytophthora infestans effector AVR3a is essential for virulence and manipulates plant immunity by stabilizing host E3 ligase CMPG1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 9909–9914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, A.; Garzo, E.; Fernandez-Mata, G.; Kassem, M.; Aranda, M.; Fereres, A. Aphids secrete watery saliva into plant tissues from the onset of stylet penetration. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2011, 139, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, T.; Tjallingii, W.F.; Thönnessen, A.; van Bel, A.J. Molecular sabotage of plant defense by aphid saliva. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 10536–10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, P.J.; Grüning, B.A.; Paszkiewicz, K.; Pritchard, L. Galaxy tools and workflows for sequence analysis with applications in molecular plant pathology. PeerJ 2013, 1, e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.R.; Dillwith, J.W.; Puterka, G.J. Salivary proteins of Russian wheat aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Environmental entomology 2010, 39, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, L.; Wu, G.; Zhang, W. Correlation between mRNA and protein abundance in Desulfovibrio vulgaris: a multiple regression to identify sources of variations. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2006, 339, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Li, L.L.; Lu, H.B.; Lu, J.B.; Wang, X.; Ye, Z.X.; Zhang, Z.L.; He, Y.J.; Lu, G.; et al. Planthopper salivary sheath protein LsSP1 contributes to manipulation of rice plant defenses. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-J.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Li, L.-L.; Lu, H.-B.; Lu, J.-B.; Wang, X.; Ye, Z.-X.; Zhang, Z.-L.; He, Y.-J.; Lu, G. Planthopper salivary sheath protein LsSP1 contributes to manipulation of rice plant defenses. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunieda, T.; Fujiyuki, T.; Kucharski, R.; Foret, S.; Ament, S.; Toth, A.; Ohashi, K.; Takeuchi, H.; Kamikouchi, A.; Kage, E. Carbohydrate metabolism genes and pathways in insects: insights from the honey bee genome. Insect molecular biology 2006, 15, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.A.; Carolan, J.C.; Wilkinson, T.L. Proteomic profiling of cereal aphid saliva reveals both ubiquitous and adaptive secreted proteins. PloS one 2013, 8, e57413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, R.; Atamian, H.S.; Shen, Z.; Briggs, S.P.; Kaloshian, I. Potato aphid salivary proteome: enhanced salivation using resorcinol and identification of aphid phosphoproteins. Journal of Proteome Research 2015, 14, 1762–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, G.; Saito, H.; Watanabe, H. A digestive β-glucosidase from the salivary glands of the termite, Neotermes koshunensis (Shiraki): distribution, characterization and isolation of its precursor cDNA by 5′-and 3′-RACE amplifications with degenerate primers. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2002, 32, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, G.; Xiang, C.; Du, M.; Cheng, J.; Liu, S.; Lou, Y. β-Glucosidase treatment and infestation by the rice brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens elicit similar signaling pathways in rice plants. Chinese Science Bulletin 2008, 53, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Francis, F.; Liu, X.; Chen, J. Insight into watery saliva proteomes of the grain aphid, Sitobion avenae. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 2021, 106, e21752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavithran, S.; Murugan, M.; Mannu, J.; Yogendra, K.; Balasubramani, V.; Sanivarapu, H.; Harish, S.; Natesan, S. Identification of salivary proteins of the cowpea aphid Aphis craccivora by transcriptome and LC-MS/MS analyses. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2024, 165, 104060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, G.M.; Trono, D. Recombinant lipases and phospholipases and their use as biocatalysts for industrial applications. International journal of molecular sciences 2015, 16, 20774–20840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, B.O.; Munnik, T. The role of phospholipase D in plant stress responses. Current opinion in plant biology 2006, 9, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.A.; Wang, X.; Leach, J.E. Changes in the plasma membrane distribution of rice phospholipase D during resistant interactions with Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae. The Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grennan, A.K. The role of trehalose biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiology 2007, 144, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.M.; Villalobos, E.; Araújo, S.S.; Leyman, B.; Van Dijck, P.; Alfaro-Cardoso, L.; Fevereiro, P.S.; Torné, J.M.; Santos, D.M. Transformation of tobacco with an Arabidopsis thaliana gene involved in trehalose biosynthesis increases tolerance to several abiotic stresses. Euphytica 2005, 146, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordachescu, M.; Imai, R. Trehalose biosynthesis in response to abiotic stresses. Journal of integrative plant biology 2008, 50, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su YunLin, S.Y.; Li JunMin, L.J.; Li Meng, L.M.; Luan JunBo, L.J.; Ye XiaoDong, Y.X.; Wang XiaoWei, W.X.; Liu ShuSheng, L.S. Transcriptomic analysis of the salivary glands of an invasive whitefly. 2012.

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, J.; Sun, J.; Francis, F.; Chen, J. Transcriptome analysis of the salivary glands of the grain aphid, Sitobion avenae. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 15911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Chino, M. Collection of pure phloem sap from wheat and its chemical composition. Plant and Cell Physiology 1986, 27, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, L.M.; Devonshire, A.L. Evidence that the E4 and FE4 esterase genes responsible for insecticide resistance in the aphid Myzus persicae (Sulzer) are part of a gene family. Biochem J 1998, 330 ( Pt 1) Pt 1, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BK, S.K.; Moural, T.; Zhu, F. Functional and structural diversity of insect glutathione S-transferases in xenobiotic adaptation. International Journal of Biological Sciences 2022, 18, 5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermoten, S.; Harmel, N.; Mazzucchelli, G.; De Pauw, E.; Haubruge, E.; Francis, F. Comparative analyses of salivary proteins from three aphid species. Insect Molecular Biology 2014, 23, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-S.; Zhao, H.-X.; Zhu, Y.C.; Scheffler, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Hulbert, S.; Stuart, J.J. Analysis of transcripts and proteins expressed in the salivary glands of Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor) larvae. Journal of insect physiology 2008, 54, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belghazi, M. Extracellular superoxide dismutase in insects: characterization, function and interspecific variation in parasitoid wasps' venom. 2011.

- Shao, E.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, S.; Guan, X.; Huang, Z. Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of putative digestive proteases in the salivary gland and gut of Empoasca (Matsumurasca) onukii Matsuda. BMC genomics 2021, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, E.; Dinoi, G.; Imbrici, P.; De Luca, A.; Liantonio, A. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ buffer proteins: A focus on the yet-to-Be-explored role of sarcalumenin in skeletal muscle health and disease. Cells 2023, 12, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue WenXin, X.W.; Fan Jia, F.J.; Zhang Yong, Z.Y.; Xu QingXuan, X.Q.; Han ZongLi, H.Z.; Sun JingRui, S.J.; Chen JuLian, C.J. Identification and expression analysis of candidate odorant-binding protein and chemosensory protein genes by antennal transcriptome of Sitobion avenae. 2016.

- Carolan, J.C.; Fitzroy, C.I.; Ashton, P.D.; Douglas, A.E.; Wilkinson, T.L. The secreted salivary proteome of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum characterised by mass spectrometry. Proteomics 2009, 9, 2457–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, R.; Gakhar, S. Study and comparison of mosquito (Diptera) aminopeptidase N protein with other order of insects. International journal of Mosquito Research 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cabot, C.; Martos, S.; Llugany, M.; Gallego, B.; Tolrà, R.; Poschenrieder, C. A role for zinc in plant defense against pathogens and herbivores. Frontiers in plant science 2019, 10, 448458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.K.; Singh, H.; Dixit, S.; Mendu, V.; Verma, P.C. Molecular characterization of vitellogenin and vitellogenin receptor of Bemisia tabaci. PloS one 2016, 11, e0155306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wileman, H.J.; Perry, R.N.; Davies, K.G. Comparative phylogenetic analysis of vitellogenin in species of cyst and root-knot nematodes. Nematology 2023, 25, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.E.; Reichert, M.C.; Evans, T.A. In vivo functional analysis of drosophila Robo1 fibronectin type-III repeats. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 2018, 8, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Fang, J.; Ji, R. Planthopper-Secreted Salivary Disulfide Isomerase Activates Immune Responses in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 622513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, N.J.; Penka, E.; Vincentelli, R. The multi-domain structure of protein disulfide isomerase is essential for high catalytic efficiency. Journal of Molecular biology 1998, 276, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönbrunner, E.R.; Mayer, S.; Tropschug, M.; Fischer, G.; Takahashi, N.; Schmid, F.X. Catalysis of protein folding by cyclophilins from different species. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1991, 266, 3630–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.Y.; Sugio, A.; Simon, J.C. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Host Plant Specificity in Aphids. Annu Rev Entomol 2023, 68, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, P.; Cock, P.J.; Bos, J. Comparative transcriptomics and proteomics of three different aphid species identifies core and diverse effector sets. BMC genomics 2016, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missbach, C.; Vogel, H.; Hansson, B.S.; Groβe-Wilde, E. Identification of odorant binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in antennal transcriptomes of the jumping bristletail Lepismachilis y-signata and the firebrat Thermobia domestica: evidence for an independent OBP–OR origin. Chemical senses 2015, 40, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippel, S.; Oberhofer, G.; Kahnt, J.; Gerischer, L.; Opitz, L.; Schachtner, J.; Stanke, M.; Schütz, S.; Wimmer, E.A.; Angeli, S. Tissue-specific transcriptomics, chromosomal localization, and phylogeny of chemosensory and odorant binding proteins from the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum reveal subgroup specificities for olfaction or more general functions. BMC genomics 2014, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos, A.; Van Drenth, M.; Erives, A.; Markstein, M.; Levine, M. Whole-genome analysis of dorsal-ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Cell 2002, 111, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, P.A.; Stam, R.; Warbroek, T.; Bos, J.I. Mp10 and Mp42 from the aphid species Myzus persicae trigger plant defenses in Nicotiana benthamiana through different activities. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2014, 27, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.; Mohamed, A.; Cattaneo, A.M.; Huang, X.; Keyhani, N.O.; Gu, M.; Zang, L.; Zhang, W. Odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in Spodoptera frugiperda: From genome-wide identification and developmental stage-related expression analysis to the perception of host plant odors, sex pheromones, and insecticides. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S/N | Statistic | Read |

| 1 | Raw Reads (bp) | 47565328 |

| 2 | Clean Reads (bp) | 46238772 |

| 3 | Clean Bases (Gb) | 6.94Gb |

| 4 | Error (%) | 0.03 |

| 5 | Q20(%) | 97.61 |

| 6 | Q30(%) | 93.04 |

| 7 | N percentage (%) | 0 |

| 8 | Total length of transcripts | 48023560 |

| 9 | Total length of genes | 25480502 |

| 10 | Number of Transcripts | 31344 |

| 11 | Number of genes | 18030 |

| 12 | Mean Length of Transcript | 1532 |

| 13 | Mean Length of gene | 1413 |

| 14 | N50 Transcript | 2335 |

| 15 | N50 Genes | 2205 |

| 16 | GC Content (%) | 42.47 |

| s/n | Data base | Number of Genes | Percentage of Genes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nr | 12589 | 69.82 |

| 2 | Nt | 14253 | 79.05 |

| 3 | KO | 5587 | 30.98 |

| 4 | Swiss-Prot | 9467 | 52.5 |

| 5 | Pfam | 9314 | 51.65 |

| 6 | GO | 9314 | 51.65 |

| 7 | KOG | 5850 | 32.44 |

| 8 | All data bases | 3670 | 20.35 |

| 9 | At least one data base | 14887 | 82.56 |

| 10 | Total Genes | 18030 | 100 |

|

Proteins identified in the saliva of M. dirhodum |

Entry | Secretory nature | Similarity level | |||

| Yes | No | 100% | 90% | 50% | ||

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 (Fragment) | A0A2H8TGI4 | √ | x | 6 | 1611 | |

| 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating |

A0A9P0J6A7 | √ | x | x | 6 | |

| Actin related protein 1 isoform X1 | A0A6G0YHT2 | √ | 182 | 190 | 4066 | |

| ACYPI010077 protein | C4WWE5 | √ | 6 | 12 | 288 | |

| ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial | A0A6G0YU19 | √ | x | x | 6 | |

| DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit CC3 domain-containing protein |

A0A8R2JNU0 | √ | x | 3 | 4 | |

| Elongation factor 1-alpha | A0A2H8TTF1 | √ | 13 | 373 | 1691 | |

| Exoribonuclease II (Fragment) | A0A6G0WGD2 | √ | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Genome assembly, chromosome: | A0A9P0JBE8 | √ | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Genome assembly, chromosome: | A0A9P0NDC0 | √ | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Glucose dehydrogenase like-protein 1 | K0DCK7 | √ | x | 2 | 2 | |

| Glucose dehydrogenase like-protein 2 | K0D9J0 | √ | x | x | 2 | |

| Glycine hydroxy methyltransferase | C4WVD4 | √ | x | x | x | |

| Heat shock protein 70KD | A0A5E4MRQ3 | √ | √ | x | 14 | 331 |

| Histone H2A / H2B / H4 (Fragment) | A0A2S2NHS9 | √ | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Odorant receptor 49b-like | A0A6G0YXA8 | √ | x | x | x | |

| Peroxiredoxin 1 | A0A2S2NYR8 | √ | x | x | 4 | |

| PHD domain-containing protein | A0A6G0VQ84 | √ | x | x | x | |

| Protein slit | A0A2S2NEH5 | √ | x | x | 2 | |

| Putative sheath protein (Fragment) | K0D9J4 | √ | x | x | 2 | |

| RNA-directed DNA polymerase (Fragment) | A0A6G0VWQ4 | √ | x | x | x | |

| TTF-type domain-containing protein | A0A8R2H9Y1 | √ | x | 2 | 2 | |

| Tubulin beta chain | A0A6G0ZHT7 | √ | 6 | 39 | 391 | |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A6G0U7P0 | √ | x | x | x | |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A6G0YI97 | √ | x | x | x | |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A8R2HBC2 | √ | x | x | x | |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A8R2NN35 | √ | x | 8 | 14 | |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A8R2JL05 | √ | x | 4 | 45 | |

| Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) | A0A2S2P8E1 | √ | x | x | x | |

| Vitellogenin domain-containing protein | A0A8R2F8V9 | √ | x | x | 9 | |

|

Protein names identified from the saliva of M. dirhodum |

Accession number | Pulse Crop Aphids | Cereal Crop Aphids | ||||||||

| A. craccivora | A. glycines | A. pisum | A. gossypii | S. graminum | S. avenae | R. padi | M. persicae | M. sacchari | Sipha flava | ||

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | A0A2H8TGI4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | √ | √ |

| 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, | A0A9P0J6A7 | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Actin related protein 1 isoform X1 | A0A6G0YHT2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | x | √ | √ |

| ACYPI010077 protein | C4WWE5 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | √ | √ |

| ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial | A0A6G0YU19 | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit CC3 domain-containing protein |

A0A8R2JNU0 | √ | x | √ | × | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Elongation factor 1-alpha | A0A2H8TTF1 | x | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | √ | x |

| exoribonuclease II (Fragment) | A0A6G0WGD2 | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Genome assembly, chromosome: | A0A9P0JBE8 | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | √ | x |

| Genome assembly, chromosome: | A0A9P0NDC0 | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | √ | x |

| Glucose dehydrogenase like-protein 1 | K0DCK7 | x | x | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x |

| Glucose dehydrogenase like-protein 2 | K0D9J0 | x | x | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x |

| Glycine hydroxy methyltransferase | C4WVD4 | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Heat shock protein 70KD | A0A5E4MRQ3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Histone H2A / H2B / H4 (Fragment) | A0A2S2NHS9 | √ | √ | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| Odorant receptor 49b-like | A0A6G0YXA8 | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Peroxiredoxin 1 | A0A2S2NYR8 | x | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | √ |

| PHD domain-containing protein | A0A6G0VQ84 | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Protein slit | A0A2S2NEH5 | x | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| Putative sheath protein | K0D9J4 | x | x | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x |

| RNA-directed DNA polymerase | A0A6G0VWQ4 | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| TTF-type domain-containing protein | A0A8R2H9Y1 | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Tubulin beta chain | A0A6G0ZHT7 | √ | √ | x | √ | x | x | x | x | √ | √ |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A6G0U7P0 | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A6G0YI97 | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A8R2HBC2 | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A8R2NN35 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | √ | √ |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A8R2JL05 | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x | √ |

| Uncharacterized protein | A0A2S2P8E1 | x | x | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| Vitellogenin domain-containing protein | A0A8R2F8V9 | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | √ | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).