1. Introduction

A social robot is an autonomous robot endowed with social skills, i.e., able to interact with humans, or, more generally, with other social agents, by understanding social norms and the corresponding compliance processes. Social Robotics aims at studying the processes by which these artificial entities can be integrated in the social systems of living creatures.

The extraordinary boost social robotics is currently displaying further boosts expectations and concerns. R&D from areas not directly affiliated with Robotics started migrating examples and presenting case studies on social robotics. The augmentation of a cellphone with a finger in [

1] is one such example, showing how interaction concerns are bringing the social flavour to a regular robotics problem.

Unsurprisingly robot developers are being forced to think social. The linguistic separation between robot developers and users (or potential users), which in other technologies would amount to a normal separation between technological and regular language, is being eliminated by users as they are forcing robotics developers to incorporate knowledge of social aspects. Ordinary users will refer to a robot using familiar terms, including social language, and it is up to the robot developers to decode it.

The general community has acknowledged the potential of Robotics for sustainable development (see, for instance, the United Nations report in [

2]). This potential is even boosted by the combination of Robotics and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Still, in the Intelligent Communication Technology (ICT) area, which bears strong connections with robotics, some authors point out that too much attention is being given to technical aspects and not enough to consumer acceptance, making some innovations fail [

3]. The determinants for ordinary people to accept ICT technologies may not be the same as those for Social Robotics. However, as discussed ahead in the paper, the interaction capabilities of current ICT devices are improving and integrating them into social robots seems a natural step.

In contrast to other areas, social robotics is still looking for practical applications that the general public finds appealing and valuable. For example, service robots, such as Roomba from iRobot, have been commercialised successfully and accepted by users in their homes. In the case of social robotics, this application is not available yet, but many candidates might appear in a coming future (e.g., hotel receptionist or assisting elders with cognitive tasks). The emergence of such applications is likely to contribute to making the social robotics business sustainable in the long run.

The expectations about a smartphone or a new app are intrinsically different from those regarding a social robot. Three factors in the TAM

1 framework (perceived usefulness, perceived ease-of-use, and perceived enjoyment) are easily assessed by ordinary people in the case of smartphones and apps. Personalised human-like communication, trust, and control are critical factors for acceptance [

5,

6]. These are factors already covered by TAM and further suggest a consensus in the research community that social robot acceptance follows generic technology acceptance factors. An extension of TAM to include measures of social responses using Wizard-of-Oz experiments and a single robot has been proposed in [

7]. Thire findings confirm the importance of the TAM factors but leave open topics, namely on the significance of psychological reactance, i.e., the resistance to influence that people may develop when perceiving some form of manipulation (see, for example, [

8], p. 367). Furthermore, there is a strong feedback connection between acceptance and self-efficacy (see, for instance, [

9] or [

10]). Estimating self-efficacy indexes is linked to high-level control techniques (quoting [

11], p. 308, on human self-efficacy, “Proficient performance is partly guided by high-order self-regulatory skills”, or [

12], p. 257, “people’s beliefs about their capabilities to exercise control over their own level of functioning and over events that affect their lives”) and involves subjective measures, e.g., as in the case of measuring the compliance with social norms.

Social robotics will also have to deal with two essential phenomena of digital technologies. There is a latent underlying trend towards dematerialisation (following [

13], “dematerialization of societies is under way”, also, [

14] refer to dematerialization as being “brought about by social robots”). That is the digitisation of all behaviours traditionally carried out physically: reading an e-book instead of going to libraries, watching movies on Netflix instead of going to the cinema, or using virtual worlds, such as the so-called metaverse, instead of interacting with real physical robots.

The other phenomenon that will probably have to be dealt with is techniques that allow social robots to capture users’ attention and increase engagement in the interaction. Other electronic devices, such as smartphones, are already doing this through variable rewards and constant notifications [

15]. They have managed to get consumers into the habit of using them daily, imposing strong lifestyle changes.

Social robotics is also about absorbing influences from other technology pushes. The current developments in machine learning are bringing to the field techniques to process sensing data close to end-to-end principles (where robot developers are relieved from the work of having to understand the data fully and, instead, a block of code maps raw data into meaningful results). Examples on emotion recognition and personality estimation are widely available [

16,

17], even as commercial, off-the-shelf, products.

Social robotics is also about absorbing influences from other technology pushes. The current developments in machine learning are bringing to the field techniques to process sensing data close to end-to-end principles (where robot developers are relieved from the work of having to understand the data fully and, instead, a block of code maps raw data into meaningful results). Examples on emotion recognition and personality estimation are widely available [

16,

17], even as commercial, off-the-shelf, products.

The increasing presence of software agents in our daily lives, e.g., with the assistants by Google, or Microsoft, though potentially contributing to wellbeing and other sustainability goals (see, for instance, the United Nations Sustainability Goals, [

18]), may dampen/amplify the expectations about real physical social robots. The media hype on social robots, fueled by a few stunts (e.g., the Sophia robot appearances), and an intrinsic desire of emotionally intelligent humans to connect with other species, even if they are artificial, keeps society unbalanced about the roles of social robots. On this topic, see, for instance, [

19] on the empathy from humans towards robots, [

20] towards animals, and [

21] on empathy towards inanimate objects, namely when including anthropomorphic features.

The current state of the art in sensing, namely that related to the human-like senses, is improving fast. Anthropomorphic interfaces, e.g., related to sound recognition

2 (which directly affects the quality of interaction), have been showing interesting performances (around 3% of word error rate in clean speech, see, for instance, [

22]). However, reaching the human level is yet to be achieved. Social robots are deployed with non-perfect interfaces, which may create trust issues in peoples’ perception [

23]. Conversely, studies demonstrated that interface errors (e.g., speech errors), after a first phase of engagement with human users with the subjects, improved the users’ perception of the familiarity of the robot [

24].

The objective of the paper is to assess the sustainability of social robots and the effects of social robots on people’s lives. The methodology is to raise questions for which either there are no definitive answers or only reduced evidence can be presented (and hence answers are left for the reader to infer). The five questions selected are:

Will human societies accommodate social robots, given the current development rate?

Are we under a novelty effect?

Can (and should) social robots compete with intelligent agents (e.g., unembodied software robots) for the attention of humans?

Will the current development of machine learning be the motor of social robotics?

What kind of robotics products and culture can we expect that will emerge?

These questions address acceptance dynamics (2), human-robot dynamics in social environments (1,3), effects of technology trends (4), and expectations related to the field of social robots (5). These are not the only ones that may be relevant, but the literature provides no assertive answers. An example is the dichotomy between social robots and social gadgets such as smartphones. Also, the role of machine learning in all aspects of everyday life remains controversial/elusive (see, for instance, the consistent failures in deploying social robots as personal assistants, receptionists, or even in showcase robots such as Sophia). Long-term social experiments in non-lab environments, e.g., as the ones reported in [

25], have shown that effectiveness can be slight (even though some of the experiments were using Wizard-of-Oz techniques and hence compensating for lack of sensory skills in the robots). This methodology results in a sequence of sections deemed relevant, each embedding its literature review. The results are a listing of possible pathways Social Robotics may evolve.

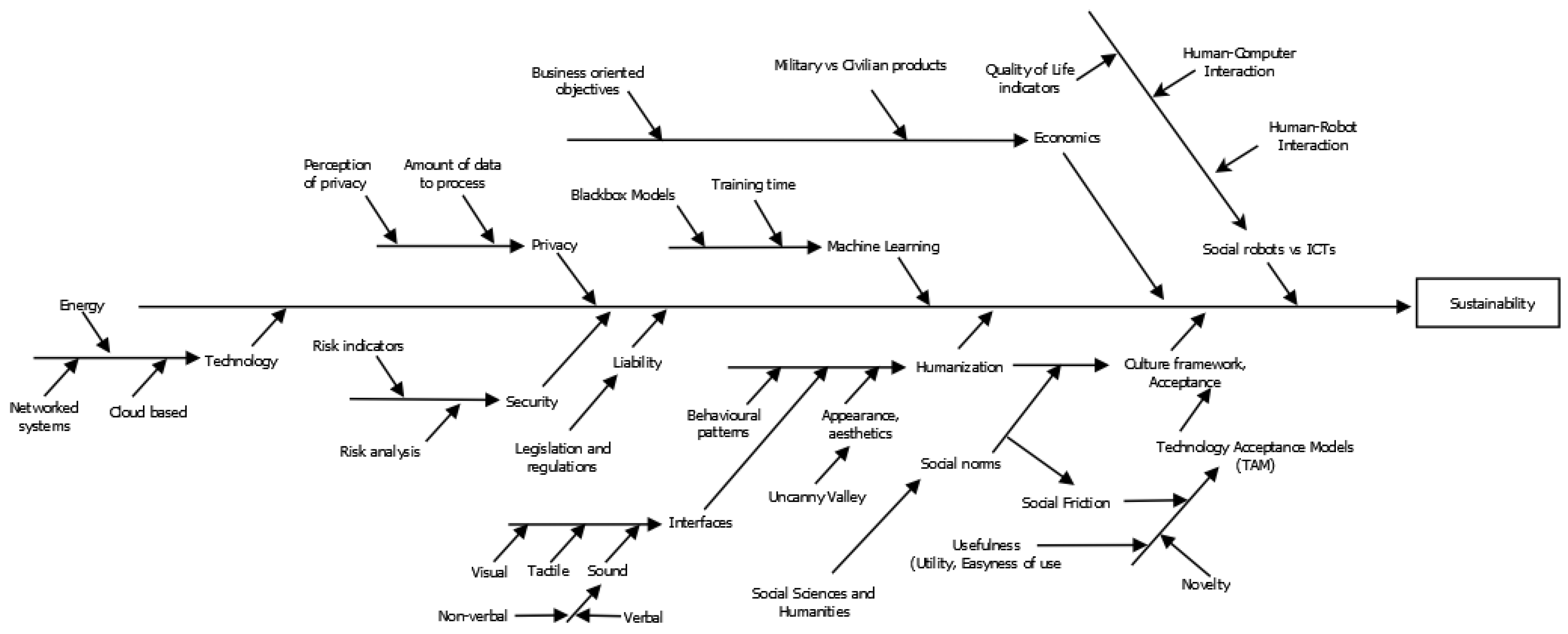

Figure 1 shows a composed Ishikawa diagram [

26] with the links between the concepts addressed. There are multiple aspects related to the sustainability of social robots and the interrelationships between them that are often neglected in the literature. The spine blocks were selected from sampling the literature for topics and concepts associated with sustainability and technology acceptance. Tradeoffs at the core of Social Robotics can be identified from the factors contributing to the head block in the diagram, i.e., sustainability. The diagram is far from complete, though it already shows the complexity and interdisciplinarity. This tool can be applied to any problem and represents a “guide to concrete action” [

26] p. 28). It can be in constant evolution as more information about the problem is fed into it, often through brainstorming processes. Techniques such as the 6M

3 are often used to construct the diagram. Social Robotics problems tend to have a structure that is not so well defined as optimising production scenarios (where Ishikawa diagrams are commonly used), making the classification of relevant factors in each of the M factors elusive, e.g., measuring compliance with a social norm, and hence building the diagram in

Figure 1 relies on the apparent interdependence of most of the factors identified in the literature. Nevertheless, factors such as risk indicators or quality of life can be associated with the Measurement class.

The paper structure is as follows.

Section 2 discusses ICT devices and social robots.

Section 3 addresses social friction factors.

Section 4 discusses humanisation. Social, economic, and technological sustainability are discussed in

Section 5 to

Section 7.

Section 8 links social robots to culture. The final remarks, in

Section 9, answer the questions stated in the abstract in light of the discussion along the paper.

2. The Boundary Layer between ICT Devices and Social Robots

As ICT devices become increasingly skilled, in social terms, an emergent question refers to the added value of social robots. In general, technologies that do not generate added value are not sustainable. A social ICT device is a computational device normally with visual, tactile, and sound interfaces, enabling it to interact with the environment, and equipped with software endowing it with social skills.

Currently, the boundary between ICT and social robotics is not widely accepted. For example, [

27] claim that a physical presence impacts the perception of a social presence. Emotions have been claimed to establish the boundary [

14]. However, the commonly accepted idea is that a larger body of evidence is required pointing to significant ad-vantages of social robots vs other social ICT devices.

Embodied robots thus have an edge on non-autonomous (static, non-robotic) ICT devices. However, the penetration of social ICT devices is much larger than that of social robots. If ICT devices have a clear edge over social robots, that should have been easily identifiable by now. Furthermore, this boundary may have different flavours, depending on the context. For example, in rehabilitation activities, some studies point to people quickly losing interest as the activities tend to be repetitive/boring [

28]. However, studies such as [

29] in the health-related ICTs point to the acceptance by seniors if they give them independence, safety, and security. Here, robots have the edge over ICT devices; body motion is a powerful tool, e.g., to convey emotions [

30].

In addition, anthropomorphic interfaces, e.g., touch, may be used to convey meaningful nonverbal information [

31]. Even though smartphones are gaining anthropomorphic characteristics, as exemplified in [

1], it seems clear that the embodiment of a social robot will outperform that of an ICT device as the number/diversity of anthropomorphic degrees will be bigger (though, in the limit, a smartphone can “converge” to a robot embodiment).

While both social robots and ICT devices are analysed as single, independent entities, the boundary between the two is somewhat rigid. However, this boundary may be smoothed when interactions of the type human-ICT device-robot are considered. ICT devices, e.g., smartphones, are already equipped with interesting (even socially skilled) voice-enabled technologies and facial recognition, which may simplify interaction with humans. Additionally, ICT devices, such as tablets, can be seen as complementary for robots as many social robots tend to integrate such devices to extend their interaction capabilities, for example, by incorporating the possibilities provided by touch screens to provide information as tactile interfaces.

3. Social Friction?

Generic robotics has been associated with the fear of rising unemployment. These fears are unjustified as this has not happened so far, though the expected improvements in robots and AI are likely to cause changes in the job markets (see the report [

2], p. xviii). Moreover, they are not grounded in social causes, i.e., the reasons are not interaction difficulties.

In what concerns social robotics, such fears emerged even in simple social robotics experiments in real-world scenarios. For instance, the EU-funded Monarch project

4 focused on interaction with children in hospitals. During the experiments where, despite the non-conflicting behaviours used by the robot, some staff members expressed concerns about the future of their jobs. Indirect societal frictions may also arise as policies to integrate emerge, e.g., the taxing of robot technologies or robot personalities. Similarly, in the ROBSEN

5 project, a social robot aimed at supporting caregivers and relatives while performing cognitive stimulation for elders with mild cognitive impairment. During the test phase, relatives, carers and therapists at some points were worried about the possibility that the robot could replace them.

Depending on the target users, another friction point appears related to the adequacy and adaptation of the robot’s tasks and interaction capabilities to the users’ needs. For example, the robots from the ROBSEN project aimed at socialising with older people. These robots were endowed with different skills, such as storytelling. In a preliminary round of tests, one of these robots was deployed in a nursing home and started an interaction session with a group of elders. After 10 minutes, a significant number of people fell asleep. Further analysis, in collaboration with experts, found that long activities are not suitable for people with cognitive impairment as they tend to lose focus. Also, at that point, the robot’s voice lacked inflexion and expressiveness, which also contributed to the issue. This experience contributed to the development of user-centred skills, adapted to the profiles of the users with enhanced Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) mechanisms that allowed better expressiveness [

32].

Social robots that fail may also lead to some intolerance and, possibly, to some social friction. As expectations about the performance of social robots increase, there is a possibility that people start to identify behavioural patterns with human personality traits (much in accordance with the definition of personality as the characteristic set of behaviours, cognitions and emotional patterns in [

33]

6), e.g., as robots actively start questioning and emphatically disagreeing with humans. As already indicated in

Figure 1, the need to integrate multidisciplinary knowledge, from Robotics and Social Sciences, is thus clear.

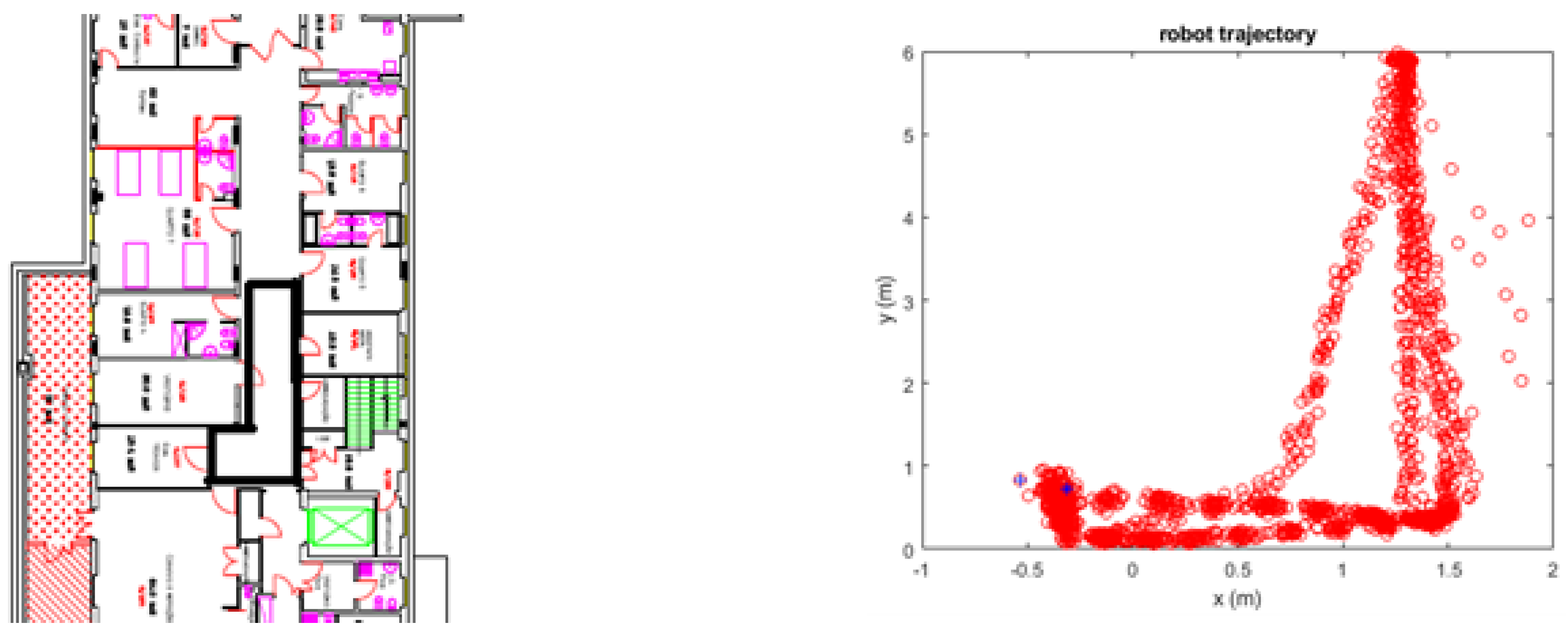

Figure 2 shows an example of an (unintentional) software glitch that refers to a Monarch robot during a long-term (several months) experiment. The lefthand image shows a blueprint of the hospital ward where this experiment occurred. The area enclosed in the thick dark line represents the location of the trajectory shown in the righthand image. The software glitch made the robot undock from its resting position (the blue star marks in

Figure 2b represent starting and end positions) during the night period, when no activity was expected, and wander around in the area, moving as shown in the trajectory in the righthand plot. This abnormal behaviour lasted for several months before being detected in a routine check of some log files. The hospital ward staff, inpatients, and visitors, never signalled that the robot was behaving in a poor social manner. Nevertheless, when asked about the situation, they acknowledged that it was strange to see the robot active off-hours (some people referred to it as annoying).

The social friction resulting from the situation illustrated in

Figure 2 may be minimised if the perception of the social value of the robot is positive (consistent with the Technology Acceptance Models (TAM) factors). However, while smartphones and apps (as examples) are technologies of individual usage, a social robot may be used in scenarios where multiple people are interacting. Therefore, besides robot-human social friction, it is also necessary to account for human-human friction resulting from the presence and/or behaviour of the robot.

Friction among people due to social robots is also to be accounted for. Different rates of bonding between people and technology have been shown to lead to social clusters. The natural example is social networks and the groups formed within these networks. The extension of these dynamics to scenarios including social robots has yet to be studied, but an extrapolation suggests the formation of similar clusters of people with identical bonding skills (or even clusters of people with very different bonding skills – similarly to some social groups in which people with very different, e.g., complementary, social skills coexist). Social psychologists have widely documented this type of behaviour in what is known as the autokinetic effect [

35].

A key goal of social robots is establishing affective bonds with people. The frequent interactions, as well as endowing robots with empathetic features, help to create these bonds. Researchers have put a lot of effort into studying how to develop and strengthen these bonding (see [

36,

37,

38]), but what happens when the bond is broken has received little attention. Especially after long-term experiments, the social bonds between users and robots might be powerful, and it is needed to study how people deal with removing social robots from their environments. When the robot has to leave (e.g., because of a malfunction or because the project has expired), users might feel its absence, like losing a pet or even a friend. For example, in the Monarch project, researchers were asked to keep the robot longer after the end of the project, even if this was not considered in the project planning.

On the contrary, some participants may be willing to interact longer when users are constrained to short interactions (for example, during a controlled experiment). However, this not being possible can cause frustration or anger in the participants and constrain their acceptance of the robot [

39]. Therefore, researchers must think carefully about how to design human-robot interactions and consider the emerging bonding effects and potential sources of frustration [

40]. In the case of child-robot interactions [

41] reported that emotion-based adaptive behaviours are more effective than game-based ones.

4. Humanising Environments?

The role of social robots in humanising environments has been discussed in the literature [

42], and it has been recently extravasated to the media. Though humanisation strictly means making an environment to abide by social norms typically followed by humans, some authors question the idea of humanising robots by claiming that humans first have to ask where the limits of humanisation are [

43], and even point to people who perceive themselves as more technologically skilled being more likely to humanise robots [

44]. The creator of the Sophia robot claims that making humanoids can make us more human [

45], which certainly contributes to acceptance [

46]. Appearance brings additional challenges. For example, soft robots may induce a perception that may trigger very different types of interaction, from caring to aggressive. However [

47] report no correlation between the perception of naturalness and softness. While a fur-bodied robot may suggest warm interactions (as observed in some animal species), an elastic-type bodied robot may suggest compliance towards rougher interactions. This points to the need for developers to control a tradeoff between emotional manipulation and tactile engagement during interaction [

48].

The intense competition social robots face nowadays from social static devices (e.g., smartphones or other ICT devices), is pushing for new research directions, namely finding when a (social) digital entity becomes a partner entity. Recent research has revealed that mind perception toward robots is enhanced when the robot is receiving a benevolent behaviour. Also, another study showed that similar psychological processes occur when children interact with humans and robots. Moreover, it has been argued that the more the robot’s face is human-like, the more people are likely to empathise and attribute positive characteristics to it.

Despite the controversy on whether or not robots should be humanised, robots may have a humanising role, even if their interaction capabilities are limited. Examples such as those presented in [

42,

49] show real situations that, otherwise the natural ambiguity, can be perceived as favouring the bonding between robots (the examples refer to a Monarch robot) and people. Transferring the positive moods generated by this human-robot bonding to interpeople interactions contributes to humanising the environment. Moreover, the nowadays recognised addictive effect of the internet and ICT devices increases the feeling of loneliness among young people and potentially causing social disconnection (for example, screen time has been negatively correlated with social skills development [

50,

51,

52], may be attenuated/reverted through social robots. Interactions such as the one shown in

Figure 3 are likely to contribute to moderating the addiction to ICT devices.

Similar behaviours towards a Roomba vacuum cleaner may not seem so natural. The robot’s embodiment has been recognised as essential to shape observers’ perception.

The potential of communication forms for both humanising and dehumanising has long been recognised (see, for instance, [

53]). While the role of social robots towards humanisation remains debatable, ICT devices with increasingly sophisticated apps targeting social aspects, e.g., emotion recognition, are becoming ubiquitous (in the so-called affective computing [

54]). Suppose that a laptop computer, equipped with a camera and microphone, is programmed to constantly analyse what it sees and hears and socially interacts with the people being observed. In that case, ethics and privacy issues naturally emerge.

Recently, research has begun to explore how privacy issues condition the social acceptance of social robots [

55]. These robots acquire information related to users (e.g., images, voice, preferences) and have more mobility and autonomy than other devices, such as smartphones, which causes users’ perceptions to change significantly with respect to other technological devices. In the context of home-care robots (carebots), privacy has been reported as one of the main concerns of professionals [

56], thus confirming the broad range of stakeholders directly concerned. Privacy is currently a multidisciplinary subject encompassing disciplines such as robotics, computer science, psychology, sociology, economics, and law, among others. The involvement of these disciplines further complicates finding common ground to define what is meant by privacy. In this sense, it is possible to refer to

physical privacy, related to access to users’ private space, and

information privacy, related to robots’ knowledge about users. Information privacy encompasses social information privacy, related to the users’ perception of how the information shared with the social robot is used. This includes issues such as the limits of information sharing (such as confidential information or passwords) between robots and users. Social information privacy is not only related to the interaction between the user and the robot, but also to the relationship between users through a robot (e.g., in a telepresence environment, the robot can be hacked).

Humanising robots is closely tied to people’s attributions to robots. In this sense, the perception of the robot’s behaviour is a key component. [

57] showed how objects that do not look alive when they are standing still can receive human (or animal) attributions, such as “hitting”, “chasing”, or “leading”, when they move. Thus, researchers have to consider the perception that users will have when interacting with a social robot that behaves in a particular way, even if this behaviour is straightforward. For example, in the case of a robot that must interact through touch, the communication may depend on how strong the contact is, i.e., inducing different perceptions and emotional states. This may be especially important with soft robots [

48].

An alternative strategy to humanise robots is to endow them with typical human features, such as humour or cheating behaviours. This will help users to attribute higher cognitive and mental capabilities than they have. For example, when a robot cheats in a game, it implies that it has the motivation to win. These higher functionalities are not real, but users attribute them to the robot. This brings a new question: are we (researchers) allowed to deceive the users’ perception?

5. Social Sustainability of Social Robots

Social sustainability, in general, has been recognised to be very complex, and this complexity (resulting from the colaboration and/or competition of multiple aspects) extends to the domain of service robots [

58] and hence to social robots.

The sustainability of a robotics culture has been related to different modalities of acceptance. [

59] recognise that the roles of robots are evolving towards social entities, and this exposes human vulnerabilities. Forecasting may thus be dependent on how people handle such vulnerabilities.

Human behaviour changes and adaptations by humans are likely to be required as social robots become integrated into human societies. This integration is expected to deliver interesting results, but it also comes at the cost, for example, of the sheer energy consumption (which, following [

60] on generic robots, at this point can no longer be neglected). While a manufacturing robot is designed (and expected) to be fully dedicated to the manufacturing process, 100% of its time, making its utilisation close to 1 (with a minimal number of stops expected), a social robot will hardly reach such a level of utilisation.

The current thinking paradigms about social robots are still evolving, shaped by the diversity of human cultures (e.g., Asian cultures tend to focus on improving daily life, whereas Western cultures spend significant efforts in defence/military robotics – see the discussion in [

59]).

Moreover, the sustainability of social robotics must not overlook social aspects, such as biases and discrimination. Equitable access to social robots may not be a necessary condition for acceptance and sustainability, but it is certainly a value-creation factor.

6. Economic Sustainability of Social Robots

As results from the discussion in the previous sections, a novel class of artificial citizens is expected. With their integration in multiple activities, these artificial citizens bring social benefits and also leave relevant economic footprints that shape the associated business cycles.

The energy required by a social robot can be bounded, roughly, estimated to be comparable with that of a human

7, around 2000/2500 kCal (or 8368/ 10460 kJ or 2.32/2.91 kWh) per day, for women/men, respectively, [

62], p. 401). A Monarch robot [

63], operating on batteries requires, roughly 3.8 kWh / per day (upper bound assuming a continuous operation, but strongly dependent on the activity level; the value drops to approximately 1/3 if an 8-hour activity period is considered). This is a strong indicator that a robot, robust enough to endure the long-term operation in real-world scenarios, leaves an energy footprint comparable (if not more significant) to that of average humans.

These energy requirements may grow significantly as the use of cloud services to handle computationally complex functions becomes the norm

8. Though the use of services distributed in the cloud has been deemed reasonable from an economic perspective, the recent explosion of AI techniques with its data-intensive strategies may be one of the critical factors influencing energy consumption. In the period 2010-2018, the computational power installed had a sixfold increase though the energy consumption only grew about 6% [

64]. However, a threefold or fourfold increase is expected for the current decade [

65].

This issue has been primarily discussed in the context of ICT devices, i.e., devices that are not robots but can, nevertheless, perform social tasks (smartphones fall in this category, though their usage model – and the respective energy consumption – strongly differs from robots, namely they do not require energy to move).

The immediate consequence is that the massification of these new beings will have dire implications for energy systems. Following [

60], generic robotics will have to adapt (or be adapted) to principles of sustainable development with limited energy and material resources. Robot economies, as called in [

66], may be around the corner and bring productivity increases and concerns and challenges, namely contradicting typical human values.

However, the economic sustainability of social robots needs to be analysed from the perspective of their applications too. For example, social robots assisting people in need would have a positive impact on national healthcare systems, considering the limited resources (e.g., professionals, beds in hospitals or places, or day-care centres).

7. Technological Sustainability of Social Robots

To date, few social robots have achieved mass, everyday use [

67]. In no case have they reached the levels of diffusion and integration into citizens’ habits that other smart devices such as phones, tablets or watches have achieved. The possible reasons for not having overcome these challenges may be due in part to the lack of maturity of some of the technologies involved in the development of these social robots. But undoubtedly, another key factor, and one that is being given relatively little consideration, is the aspect of human psychology in the design and development of these technological devices. This is especially relevant when the potential user is a dependent person.

The technology presents challenges that need to be overcome to improve the sustainability of social robots. Interaction mechanisms need more sophisticated devices to enable interaction with different types of users, including those with disabilities. Social robots tend to integrate advances from other fields (such as projectors, touch screens, or even aug-mented reality) to improve their interaction capabilities.

One area that has benefited most from technological advances has been perception. In recent years, multiple low-cost devices capable of capturing 3D and RGB information have emerged. Additionally, audio acquisition also benefited from recent advances in capture devices, such as the omnidirectional microphones that initially appeared in smart speakers. These capture devices have great potential to enable the development of perception systems that mimic human capabilities.

The technological sustainability of social robots may involve the inclusion of different devices that allow them to extend their capacities beyond the robot’s own body. In this sense, the sensing and actuation capabilities of social robots can be complemented with external devices such as wearables or IoT devices. The former will provide real-time information about the state of the users, allowing the robots to analyse and predict future problems associated with the users’ health. IoT devices will monitor the user’s environment, allowing the robot to add a layer of safety and security to its abilities.

As the capabilities of social robots increase, one problem has begun to emerge: computing constraints. Social robots differ from conventional equipment in that their aesthetic design often means that hardware elements must be small enough to be integrated into the robot’s body. This severely restricts the computing equipment that can be mounted inside the robots. Today we are in the era of deep learning, and high-performance graphics cards are available on the market to extend the computational power of social robots. However, these tend to be large, which prevents them from being integrated into such robots. Another constraint that can affect social robots is the power consumption of integrated devices. Computationally intensive devices tend to require large amounts of energy, reducing the robots’ autonomy.

Nowadays, there are computational alternatives, both integrated into the robot and in the cloud. On the one hand, there are low-power computing devices, such as the NVidia Jetson

9, Intel Neural Stick

10 or Google Coral

11, which are small but have features similar to graphics processors, although without reaching their performance. Their small size and low power consumption would allow them to be integrated into the internal space of social robots. On the other hand, cloud computing is postulated as a possible solution for managing the processing requirements of social robots without requiring the integration of new hardware devices. The reduction in the latency of communications networks, boosted by the emergence of new wireless technologies such as 5G, allows decentralised processing without the user noticing latencies. These cloud technologies bring new challenges regarding cost, security, and privacy. In terms of cost, cloud processing entails a recurring expense that users should bear. In addition, there are concerns about data security and privacy

12 as the data is no longer on the robot itself but is processed on external servers. In this sense, it is the task of developers to integrate the necessary protocols to ensure the protection of users’ data. Even so, it remains unclear whether users would trust their data, collected by a robot autonomously (which may already raise concerns), to be sent to external servers in the cloud.

8. In Need of a Framework for Culture Generation by Social Robots

Sustainability and culture have been recognised to have complex relations (see [

68] for a discussion on definitions of both terms). However, the recognition that culture impacts the life of societies and sustainability must occur within a cultural context [

69]; hence creating a social robotics culture can be a pathway for sustainable social robotics.

Currently, social robots have few creative skills and hence miss one of the three skills often associated with culture producers (creative, managerial, and communication systems, see [

8], chap. 15). However, these are not strict boundaries, and if a robot is perceived as being creative that may be due to some liveliness/randomness characteristics – see, for instance, some painting creations produced by robots. Creating robots able to produce culture is thus a challenging endeavour. [

70] defines culture as a mechanism that promotes group success through cooperation, for which trust is a fundamental value. The current state of the art in social robots may foster deception and hence the loss of trust.

The ongoing technology development is not targeting, explicitly, culture generation. Instead, culture is seen as a byproduct of behavioural skills, emotions, social norms, and other factors linked to individual social skills.

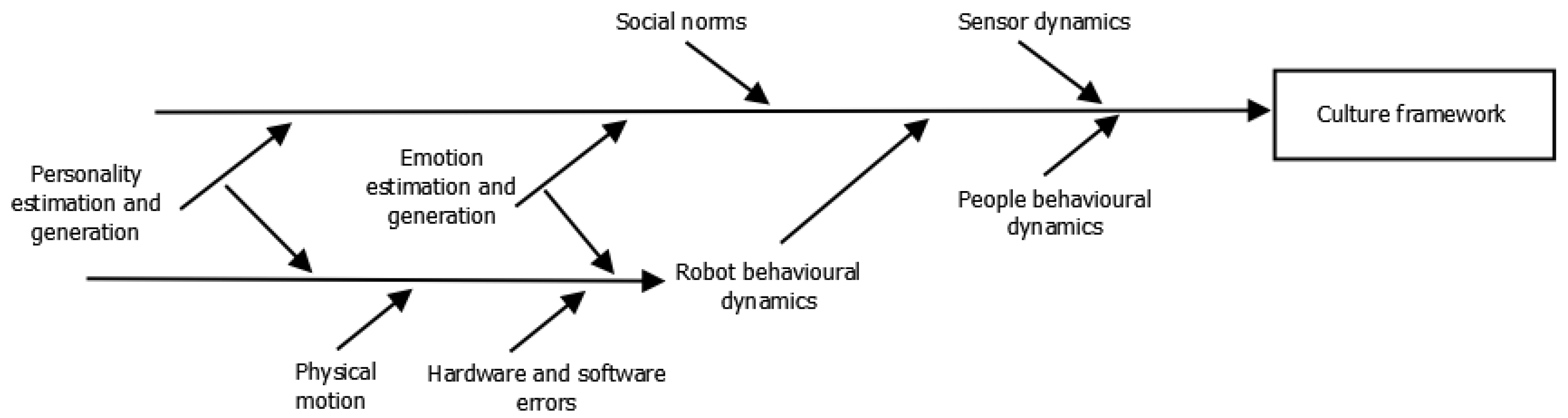

Figure 4 shows a selection of the main factors, we argue, that are involved in culture production, following the interpretation of the definition in [

71]

13. The selection of the spine blocks results from a sampling of the literature on SR for the main topics currently addressed by researchers. While SR is blossoming, it is not expectable that it will affect political systems, a wide requirement for a harmonious development of societies and hence sustainability [

68].

Another possibility is to look at social robots themselves as culture. Social robotics, and robotics in general, is part of a creative process that is intrinsic to the creative process of engineering. But the main difference of social robotics, in comparison to other disciplines, is its underlying multidisciplinary. Creating social robots can require the participation of engineering, psychologist, designers, sociologists, and other profiles, depending on the robot application. The combination of the insights from these profiles in a unique, novel piece of technology can be seen as technological art that contributes to the success of science and technology in the progress of humankind.

9. Final Remarks

Current social robotics is facing multiple possible pathways. Most of the literature focuses on acceptance in limited scenarios, and there is a lack of experiments on proper social integration and the potential changes in lifestyle, i.e., with a diverse human population, of large enough size and long enough duration (factors already recognised as important in [

25]). These issues influence sustainability can be tracked to the questions asked along the paper.

Though a Gartner Hype Cycle

14 (GHC) for Social Robots is currently not available (and extrapolation from AI and/or emerging technologies cycles may not be acceptable), the questions in the abstract, supported by the arguments developed along the paper, can be given straight answers.

This question is semantically equivalent to acceptance. Throughout the paper, multiple factors constraining acceptance were identified. Some of these are already vastly studied in the literature; others are mostly ignored. The arguments developed point to an unequivocally “yes” answer and reinforce the confidence of the community.

People develop expectations towards novel technologies. The questions raised along the paper, the lack of definitive results on the effectiveness of social robots in some applications, e.g., in education, and the growth of the social robotics community, suggest that the answer be “yes” and that social robotics in the initial positive slope of a GHC. The lack of long-term experiences where humans and robots coexist in daily environments leads to speculations about how these novelty effects will fade out. In practical terms, being under a novelty effect means that the interest in social robots is going to fade away, which prompts researchers to work predictively on alternative solutions. In terms of a Gartner curve, we may be at the peak and the valley of delusion will follow soon. Reaching the plateau of productivity may depend on the ability of research to propose novel paradigms.

The paper answers this question by pointing to the difficulty in establishing a boundary between social robots and ICT devices and acknowledging the lack of consensus in the scientific community. Therefore, there is already an ongoing intrinsic competition between the two classes, although some researchers opt for combining both technologies. Social robots like the Paro baby seal [

72] have shown the advantages of having people interacting with embodied devices. It is unlikely that a baby seal app, implemented in a smartphone, would have the same results. However, a smartphone covered in artificial skin may be made to operate as an alternative sort of creature (possibly bearing no relation with any living animal) and still please humans. Social robots and ICTs can evolve along parallel directions.

As the perception of intelligence resulting from ML applications increases, it can be expected that acceptance of social robots increases, hence powering social robotics. The answer is thus “yes”. Boosting the perception of intelligence is linked to having robots interacting and perceiving data similarly to humans. This means having speech recognition in real-world conditions, speech synthesis consistent with human behavioural patterns, and tactile and vision recognition functioning similarly to humans.

The paper shows that the boundary between social robots and ICT devices can be blurred. ICT devices, being closer to people and possibly less intimidating than social robots, may have a substantial effect on people’s perception of usefulness and hence help modulate a culture of acceptance of complex devices with which people must learn to interact (other than reading an instruction manual). Therefore, the answer is “yes, new products will emerge”. Assistant robots, with social skills that make them useful for people, can be reasonably expected, e.g., robots able to navigate around older adults, constantly analysing their movements to assess the risk of falls, or simply social companion robots, extending the concept started with the Paro robot [

72] to anthropomorphic robots. Experimenting with social robots is likely to generate ideas that can also be used by ICTs, e.g., the smartphone covered with artificial skin. Classes of people with similar acceptance levels may easily form subcultures. Following [

73], cultural behaviour is not programmable into a robot, but instead the interactions are responsible for cultural behaviour.

Social robotics sustainability is not endangered. The factors and their respective relations (i.e., the game played) affecting sustainability have been identified in the literature. Therefore, reaching some equilibrium that maximises the utility for society is just a question of playing the gamble well. The answers above confirm some pathways, e.g., the rising influence of AI in social robotics, and suggest other pathways, e.g., the need to develop novel forms of bringing knowledge on human behaviour into Social Robotics.

However, the ongoing game can be dangerous for Robotics (as a scientific area) as it risks embedding Cargo Cult

15 science. With the number of papers on the crossing of Social Sciences, Artificial Intelligence, and Robotics on an extraordinary increase, we may be losing something about what it means to be human and why humans really want/need robots. The game being played by robotics researchers may turn out to be a gamble.

By creating truly useful robots of high social acceptance we are uncovering computational models that explain human social behaviours. It is almost paradoxical that humans gain knowledge about themselves by creating artificial creatures. This may be simply because of the desire, intrinsic to humans, to replicate themselves.

It is expected that, after achieving sustainable social robots, our lifestyle will change. Social robots will populate many environments and business where people need services that require some sort of social interaction.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the projects: “LARSyS-FCT UIDB/50009/2020”, from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), Portugal, “Robots sociales para mitigar la soledad y el aislamiento en mayores (SOROLI), PID2021-123941OA-I00”, funded by Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, “Robots sociales para reducir la brecha digital de las personas mayores (SoRoGap), TED2021-132079B-I00”, funded by Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. This publication is part of the R&D&I project PDC2022-133518-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Teyssier, M. Anthropomorphic Devices for Affective Touch Communication. PhD thesis, Institut Polytechnique de Paris, France, 2020. Doctoral dissertation, HAL Id: tel-02881894. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02881894.

- United Nations. Technology and Innovation Report 2021. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 2021. Geneva.

- Verdegem, P.; De Marez, L. Rethinking determinants of ICT acceptance: Towards an integrated and comprehensive overview. Technovation 2011, 31, 411–423. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13, 319–339. [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.; Prakash, A.; Mitzner, T.; Rogers, W. Understanding Robot Acceptance. Technical report, Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology School of Psychology, 2011. Technical Report HFA-TR-1103, Human Factors and Aging Laboratory, http://hdl.han-dle.net/1853/39672.

- Whelan, S.; Murphy, K.; Barrett, E.; Krusche, C.; Santorelli, A.; Casey, D. Factors Affecting the Acceptability of Social Robots by Older Adults Including People with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment: A Literature Review. International Journal of Social Robotics 2018, 10, 643–668. [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, A.; Ham, J.; Bararova, E.; Markopoulos, P. Persuasive Robots Acceptance Model (PRAM): Roles of Social Responses Within the Acceptance Model of Persuasive Robots. International Journal of Social Robotics 2020, 12, 1075–1092. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.; Bamossy, G.; Askegaard, S.; Hogg, M. Consumer Behavior. A European Perspective, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall and Pearson Education Ltd, 2006.

- Latikka, R.; Turja, T.; Oksanen, A. Self-Efficacy and Acceptance of Robots. Computers in Human Behavior 2019, 93, 157–163. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.; Hicks, T.; Suddrey, G.; Kavanagh, D. The Robot Self-Efficacy Scale: Robot Self-Efficacy, Likability and Willingness to Interact Increases After a Robot-Delivered Tutorial. In Proceedings of the 29th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 2020. Naples, Italy, 31 August 2020 - 04 September.

- Bandura, A. Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Information Age Publishing, 2005; pp. 307–337.

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 248–287.

- Wernik, I.; Herman, R.; Govind, S.; Ausubel, J. Materialization and Dematerialization: Measures and trends. Daedalus 1996, 125, 171–198.

- Sugiyama, S.; Vincent, J. Social Robots and Emotion: Transcending the Boundary Between Humans and ICTs. Intervalla 1 2013. ISSN: 2296-3413.

- Eyal, N. Hooked: How to build habit-forming products; Business Books, 2014.

- Castillo, J.; Castro-González, Á.; Fernández-Caballero, A.; Latorre, J.; Pastor, J.; Fernández-Sotos, A.; Salichs, M. Software architecture for smart emotion recognition and regulation of the ageing adult. Cognitive Computation 2016, 8, 357–367. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, M.; Cao, W.; Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, R.; Mao, J. A facial expression emotion recognition-based human-robot interaction system. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2017, 4, 668–676. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals, 2021. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/, [Retrieved August 2021].

- Rosenthal-von der Pütten, A.; Krämer, N.; Hoffmann, L.; Sobieraj, S.; Eimler, S. An Experimental Study on Emotional Reactions Towards a Robot. International Journal of Social Robotics 2013, 5, 17–34. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R.; Costa, A.; Megías-Robles, A.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Faria, L. Relationship between emotional intelligence and empathy towards humans and animals. PeerJ 2021, 9. article e11274. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. Lovable Lamps and Sad Umbrellas: Empathising with Inanimate Objects in Animated Films, 2021. Master’s thesis, Electronics theses and Dissertations, https://hdl.handle.net/2104/11414.

- Georgescu, A.; Pappalardo, A.; Cucu, H.; Blott, M. Performance vs. hardware requirements in state-of-the-art auto-matic speech recognition. EURASIP Journal on Audio, Speech, and Music Processing 2021, 28. [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.; Kaniarasu, P.; Medvedev, M.; Steinfeld, A.; Yanco, H. Impact of robot failures and feedback on real-time trust. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 2013, pp. 251–258. Tokyo, Japan, 3-6 March. [CrossRef]

- Gompei, T.; Umemuro, H. A robot’s slip of the tongue: Effect of speech error on the familiarity of a humanoid robot. In Proceedings of the 24th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 2015, pp. 331–336. Kobe, Japan, 31 August - 4 September. [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Ishiguro, I. Human-Robot Interaction in Social Robotics; CRC Press, 2013.

- Ishikawa, K. Guide to quality control, 1976.

- Bainbridge, W.; Hart, J.; Kim, E.; Scassellati, B. The benefits of interactions with physically present robots over video-displayed agents. International Journal of Social Robotics 2011, 3, 41–52. [CrossRef]

- Guneysu Ozgur, A.; Wessel, M.; Johal, W.; Sharma, K.; Özgür, A.; Vuadens, P.; Mondada, F.; Hummel, F.; Dillenbourg, P. Iterative design of an upper limb rehabilitation game with tangible robots. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 2018, pp. 241–250. Chicago, Illinois, USA, 5-8 March.

- Vassili, L.; Farshchian, B. Acceptance of Health-Related ICT among Elderly People Living in the Community: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 2018, 34, 99–116. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hossain Bari, A.; Gavrilova, M. Emotion recognition from body movement. IEEE Access 2019. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Vogel, D.; Madon, S.; Edwards, S. The Power of Touch: Nonverbal Communication Within Married Dyads. The Counselling Psychologist 2011, 39, 764–787. [CrossRef]

- Salichs, M.; Encinar, I.; Salichs, E.; Castro-González, Á.; Malfaz, M. Study of scenarios and technical requirements of a social assistive robot for Alzheimer’s disease patients and their caregivers. International Journal of Social Robotics 2016, 8, 85–102. [CrossRef]

- Corr, P.; Matthews, G. The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology; Cambridge University Press, 2009. Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology.

- Ramezani, M.; Feizi-Derakhshi, M.; Balafar, M.; Asgari-Chenaghlu, M.; Feizi-Derakhshi, A.; Nikzad-Khasmakhi, N.; Ranjar-Khadivi, M.; Jahanbakhsh-Nagadeh, Z.; Zafarani-Moattar, E.; Rahkar-Farshi, T. Automatic Personality Prediction; an Enhanced Method Using Ensemble Modelling, 2021. arXiv:2007.04571v3 [cs.CL] 21 Feb 2021.

- Gregory, R.; Zangwill, O. The Origin of the Autokinetic Effect. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 1963, 15, 252–261. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Nuno, N.; Saez-Pons, J.; Pardo, D.; Angulo, C. Building up child-robot relationship for therapeutic purposes: From initial attraction towards long-term social engagement. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG), 2011, pp. 927–932. Santa Barbara, California, USA, 21-25 March.

- Willemse, C.; Van Erp, J. Social touch in human-robot interaction: Robot-initiated touches can induce positive responses without extensive prior bonding. International Journal of Social Robotics 2019, 11, 285–304.

- Schellin, H.; Oberley, T.; Patterson, K.; Kim, B.; Haring, K.; Tossell, C.; Phillips, E.; de Visser, E. Man’s new best friend? Strengthening human-robot dog bonding by enhancing the doglikeness of Sony’s Aibo. In Proceedings of the 2020 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), 2020, pp. 1–6. Charlottsville, Virginia, USA, 24 April.

- Jirak, D.; Aoki, M.; Yanagi, T.; Takamatsu, A.; Bouet, S.; Yamamura, T.; Sandini, G.; Rea, F. Is It Me or the Robot? A Critical Evaluation of Human Affective State Recognition in a Cognitive Task. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2022, 16. [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, A.; Rußweinkel, N. The Role of Frustration in Human-Robot Interaction – What is Needed for a Successful Collaboration? Frontiers in Psychology 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Mubin, O.; Orlando, J. Adaptive Social Robot for Sustaining Social Engagement during Long-Term Children-Robot Interaction. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2017, 33, 943–962. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, J. Can Social Robots make societies more human? Information 2018. Special issue on Roboethics (ISSN 2078-2489).

- Giger, J.; Piçarra, N.; Alves-Oliveira, P.; Oliveira, R.; Arriaga, P. Humanisation of robots: Is it really such a good idea? Human Behavior & Emerging Technologies 2019, 1, 111–123. [CrossRef]

- Mays, K. Humanising Robots? The Influence of Appearance and Status on Social Perceptions of Robots. PhD thesis, Boston University, College of Communication, 2021. Doctoral Dissertation, Boston University Libraries, OpenBU, https://hdl.handle.net/2144/41877.

- Hanson, D. Humanising Robots. How Making Humanoids Can Make Us More Humans, 2007. Doctor Dissertation Public edition, ISBN 13: 9781549659928.

- Robert, L. The Growing Problem of Humanizing Robots. International Robotics & Automation Journal 2017, 3. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, J.; Bojesen, K.; Jochum, E. Is a Soft Robot More “Natural”? Exploring the Perception of Soft Robotics in Human-Robot Interaction. International Journal on Social Robotics 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, T.; Scheutz, M. The Tactile Ethics of Soft Robotics: Designing Wisely for Human-Robot Interaction. Soft Robotics 2017, 4, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, J. Developing a Social Robot – A Case Study. In Robotics in Healthcare – Field Examples and Challenges; Sequeira, J., Ed.; Springer Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1170, Springer, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Lee, E.; Hesketh, K.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Predy, M.; Rhodes, R.; Rinaldi, C.; Spence, J.; Hinkley, T. Physical activity and sedentary behavior across three time-points and associations with social skills in early childhood. BMC Public Health 2019, pp. 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.; Spitzberg, B.; Campbell, W. Less in-person social interaction with peers among US adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2019, 36, 1892–1913. [CrossRef]

- Uhls, Y.; Michikyan, M.; Morris, J.; Garcia, D.; Small, G.; Zgourou, E.; Greenfield, P. Five days at outdoor education camp without screens improves preteen skills with nonverbal emotion cues. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 39, 387–392. [CrossRef]

- Guthermuth, P. Humanising and Dehumanising Potentials in Communication Technology: Towards A Value Based Perspective. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 2001, 87, 9–19. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/24536199.

- Picard, R. Affective computing; MIT press, 2000.

- Lutz, C.; Tamó-Larrieux, A. The robot privacy paradox: Understanding how privacy concerns shape intentions to use social robots. Human-Machine Communication 2020, 1, 87–111. [CrossRef]

- Suwa, S.; Tsujimura, M.; Ide, H.; Kodate, N.; Ishimaru, M.; Shimamura, A.; Yu, W. Home-care Professionals’ Ethical Perceptions of the Development and Use of Home-care Robots for Older Adults in Japan. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2020, 36, 1295–1303. [CrossRef]

- Heider, F.; Simmel, M. An experimental study of apparent behavior. American Journal of Psychology 1944, 57, 243–259. [CrossRef]

- Kohl, J.; van der Schoor, M.; Syré, A.; Goblich, D. Social Sustainability in the Development of Service Robots. In Proceedings of the International Design Conference - DESIGN 2020, 2020. Cavtat, Croatia, 26-29 October. [CrossRef]

- Samani, H.; Saadatian, E.; Pang, N.; Polydorou, D.; Fernando, O.; Nakatsu, R.; Koh, J. Cultural Robotics: The Culture of Robotics and Robotics in Culture. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2013, 10. [CrossRef]

- Bugmann, G.; Siegel, M.; Burcin, R. A role for robotics in sustainable development? In Proceedings of the Africon 2011. IEEE, 2011. Victoria Falls, Livingston, Zambia, 13-15 September. [CrossRef]

- FNB. Recommended Dietary Allowances, 1989. National Research Council (US) Subcommittee on the Tenth Edition of the Recommended Dietary Allowances.

- Stefanick, M. Obesity – The Role of Physical Activity in Adults. In Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease; Coulson, A.; Boushey, C., Eds.; Elsevier, 2008. Chapter 23, 2nd edition.

- Alvito, P.; Marques, C.; Carriço, P.; Sequeira, J.; Gonçalves, D. Monarch Robots Hardware, 2014. Deliverable D2.2.1, European Project FP7-ICT-2011-9-601033, January.

- Lohr, S. Cloud Computing Is Not the Energy Hog That Had Been Feared, 2020. The New York Times, February 28.

- Masanet, E.; Shehabi, A.; Lei, N.; Smith, S.; Koomey, J. Recalibrating global data center energy-use estimates. SCIENCE 2020, 367, 984–986. [CrossRef]

- Arduengo, M.; Senties, L. The Robot Economy: Here It Comes. International Journal of Social Robotics 2021, 13, 937–947. [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, A.; Wood, N. The Paro seal robot: demeaning or enabling. In Proceedings of the AISB’14, The 50th Aniversary Convention of the AISB, 2014. University of London, 1-4 April.

- Throsby, D. Sustainability and culture some theoretical issues. International Journal of Cultural Policy 1997, 4, 7–19. [CrossRef]

- ESCAP. The importance of culture in achieving sustainable development, 2013. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). Sustainable Development Brief, 8th March 2013/SDWG.

- Saetra, H. Social robot deception and the culture of trust. Paladyn Journal of Behavioral Robotics 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, R. Culture, cultural factors and psychiatric diagnosis: review and projections. World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Shibata, T. Living with Seal Robots - Its Sociopsychological and Physiological Influences on the Elderly at a Care House. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2007, 23, 972–980.

- Ornelas, M.; Smith, G.; Mansouri, M. Redefining culture in cultural robotics. AI & Society 2022.

| 1 |

Technology Acceptance Model, see for instance [ 4]. |

| 2 |

Including verbal and non-verbal sound recognition. |

| 3 |

Mnemonic representing 6 factors, relevant in production scenarios, Manpower, Machine, Method, Material, Milieu, and Measurement. |

| 4 |

The European Project FP7-ICT-2011-9-601033 Monarch – Multi- Robot Cognitive Systems Operating in Hospitals. |

| 5 |

The Project Development of social robots to help seniors with cognitive impairment (ROBSEN), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. |

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

There are multiple factors influencing energy requirements (see for instance [ 61]). |

| 8 |

Eurostat data indicates that 41% of European companies used cloud services in 2020 and in 2021 there was a 5% increase. |

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

“Culture is defined as set of behavioral norms, meanings, and values or reference points utilized by members of a particular society to construct their unique view of the world, and ascertain their identity”, [ 71], p. 133. |

| 14 |

Yearly technology trends published by the Gartner Inc. (gartner.com). |

| 15 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).