Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

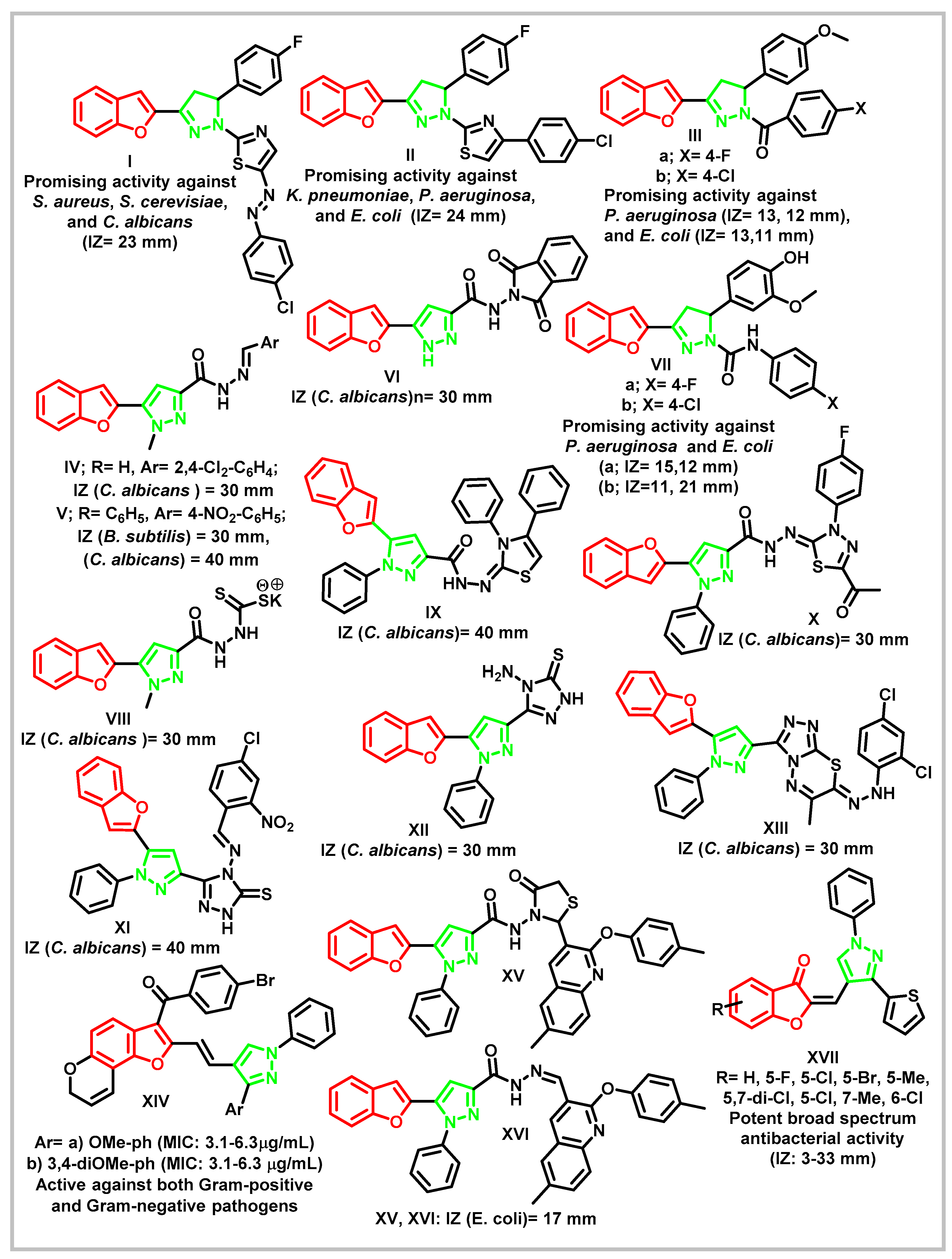

1. Introduction

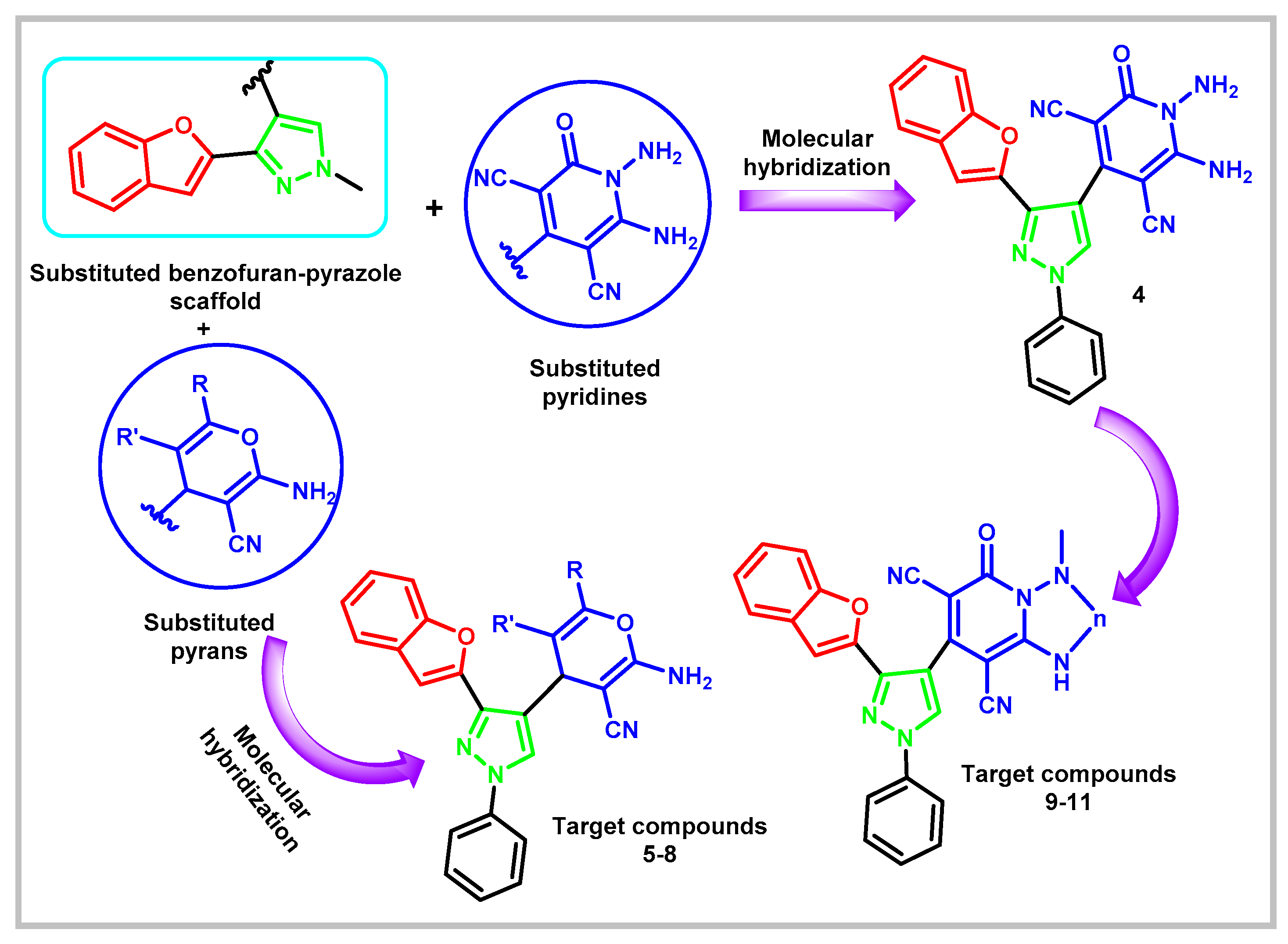

1.1. Design rationale

2. Results and Discussion

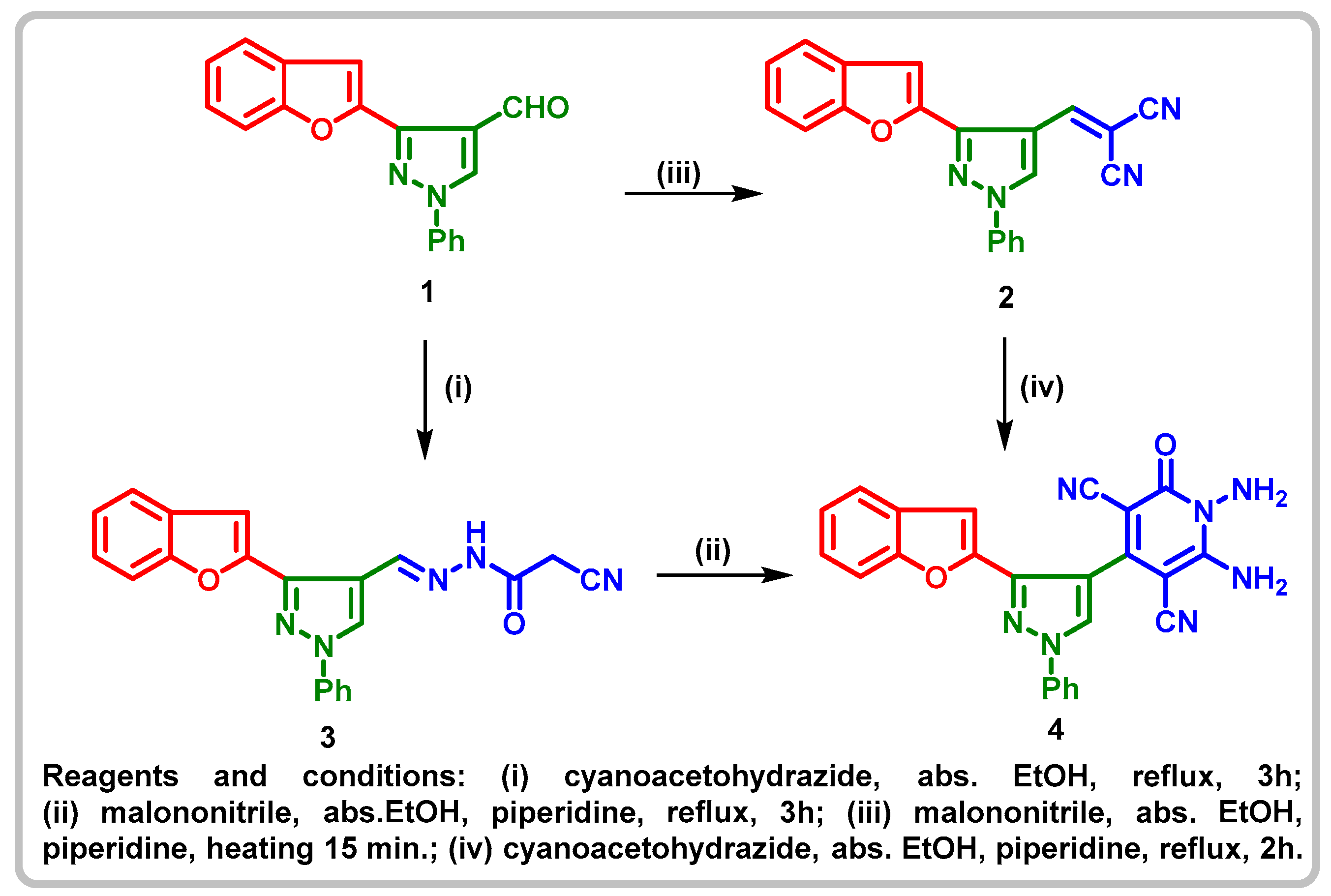

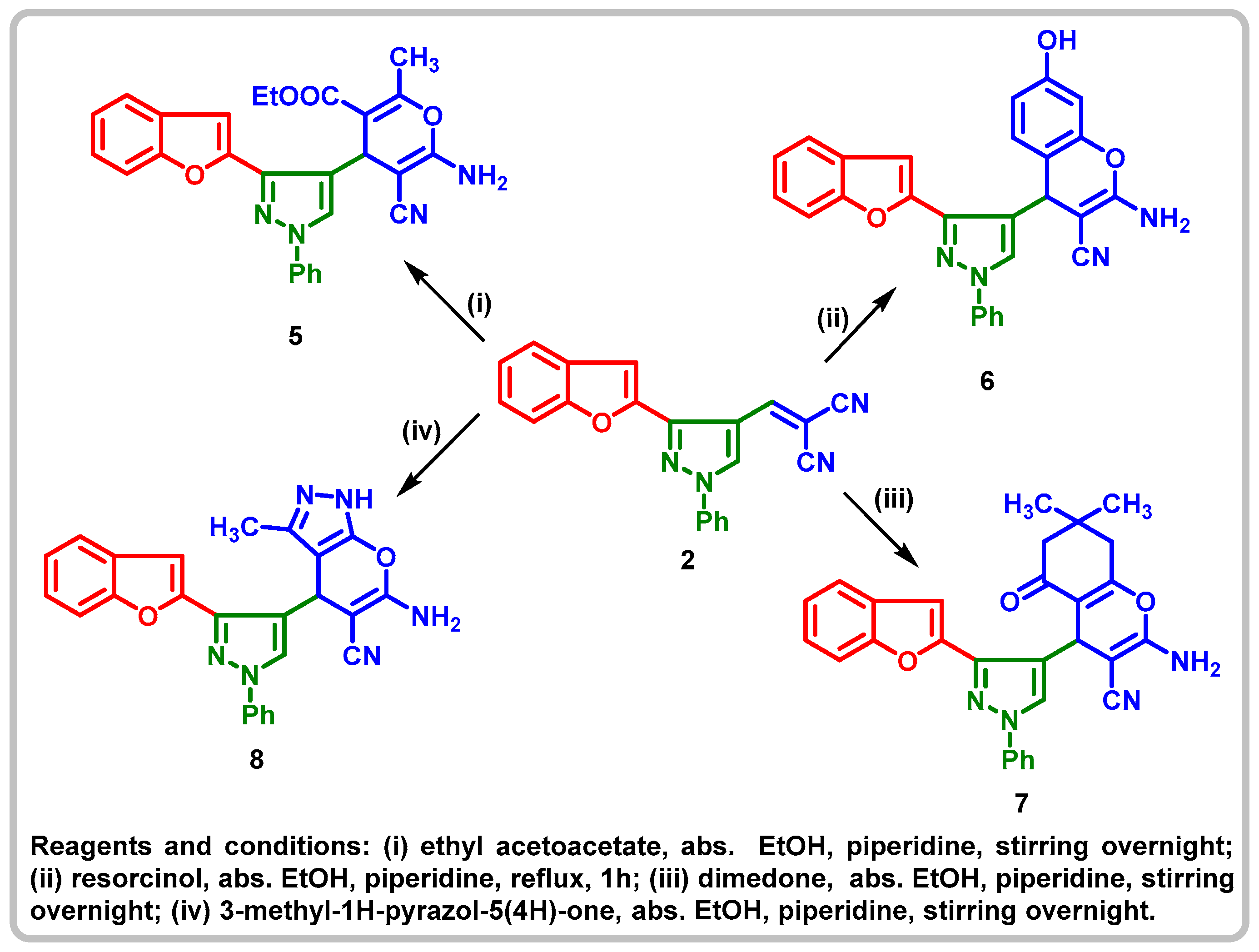

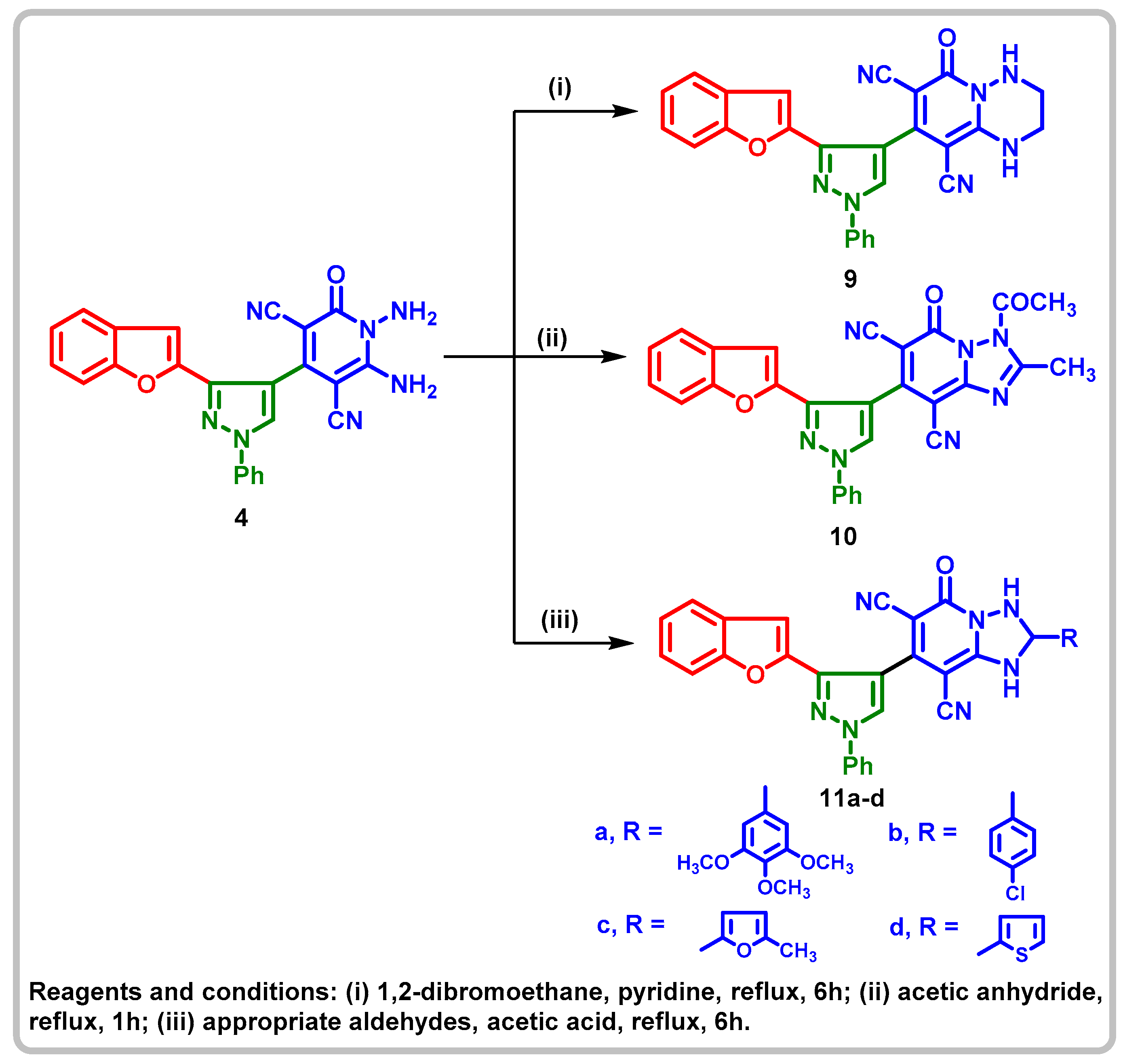

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Biological Evaluation

2.2.1. Antimicrobial Activity Determination

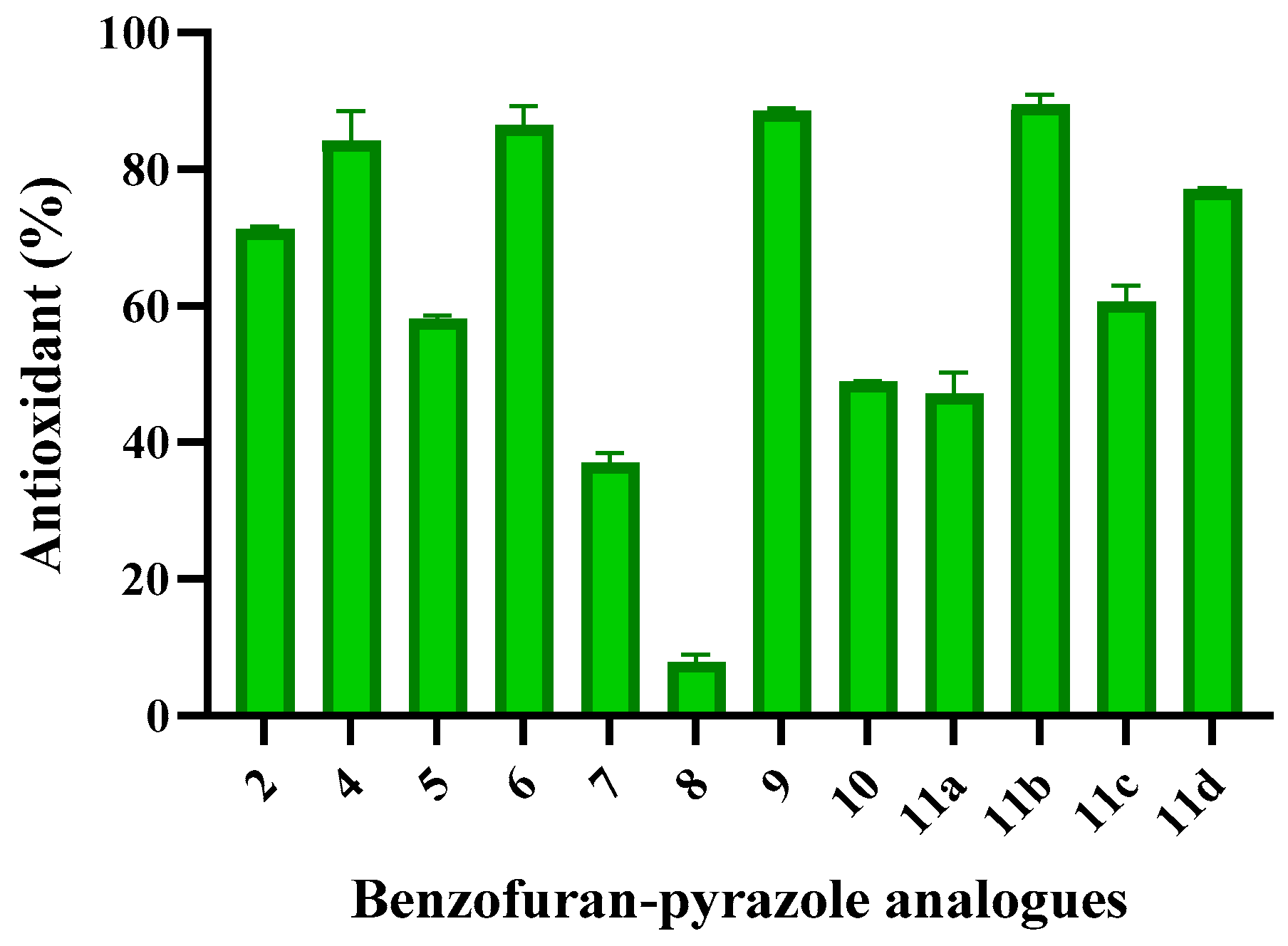

2.2.2. Antioxidant Activity

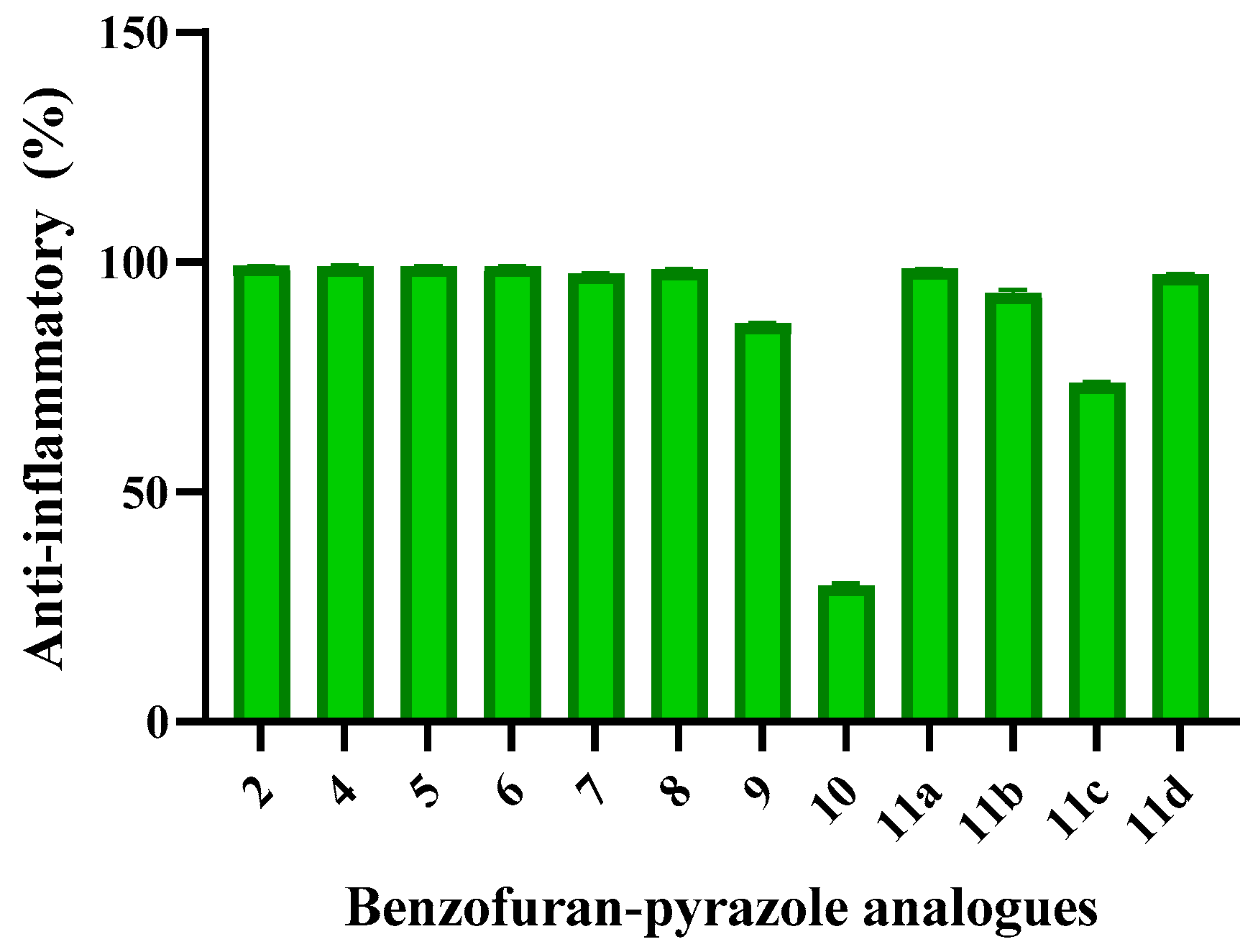

2.2.3. Anti-Inflammatory Assay

| Compound No. |

Anti-inflammatory | Antioxidant activity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Hemolysis | % Protection | %DPPH radical scavenging activity | |

| 2 | 0.82±0.108 | 99.25±0.108 | 71.19±0.43 |

| 4 | 0.67±0.194 | 99.19±0.194 | 84.16±4.41 |

| 5 | 0.76±0.151 | 99.13±0.151 | 58.10±0.52 |

| 6 | 0.76±0.086 | 99.18±0.086 | 86.42±2.85 |

| 7 | 2.38±0.173 | 97.50±0.173 | 37.06±1.38 |

| 8 | 1.43±0.173 | 98.44±0.173 | 7.89±1.04 |

| 9 | 13.12±0.259 | 86.70±0.259 | 88.56±0.43 |

| 10 | 70.68±0.496 | 29.67±0.496 | 48.93±0.09 |

| 11a | 1.37±.086 | 98.57±0.086 | 47.16±3.03 |

| 11b | 6.16±0.755 | 93.30±0.755 | 89.42±1.56 |

| 11c | 26.60±0.388 | 73.67±0.388 | 60.61±2.34 |

| 11d | 2.84±0.259 | 97.35±0.259 | 77.00±0.26 |

| Aspirin | 1.98±0.173 | 97.90±0.173 | ---- |

| Diclofenac | 0.46±0.043 | 99.51±0.043 | ----- |

| Ascorbic acid | ---- | ---- | 100±0.00 |

2.2.4. E. coli DNA Gyrase B Suppression Effect

2.2.5. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

2.3. In Silico Studies

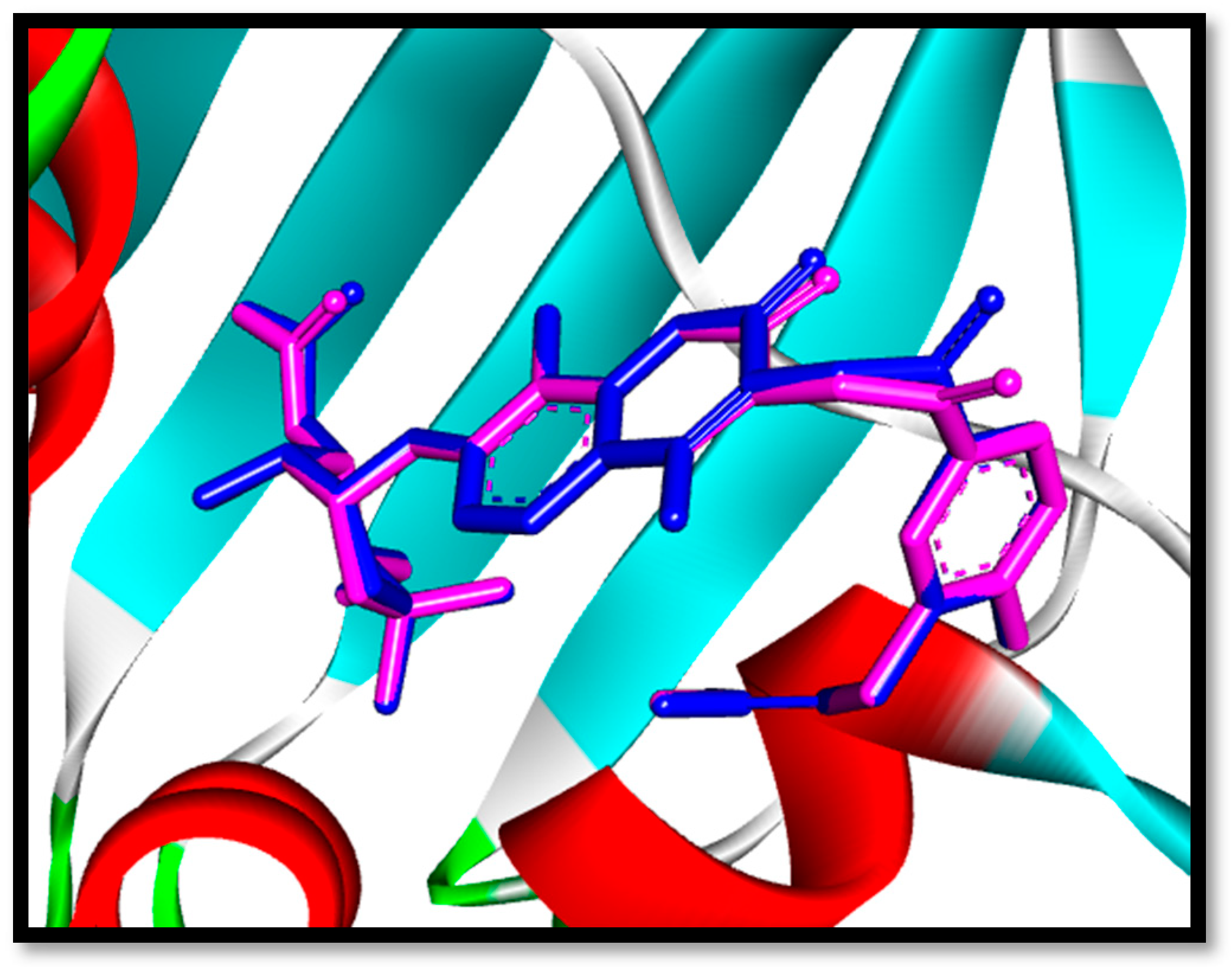

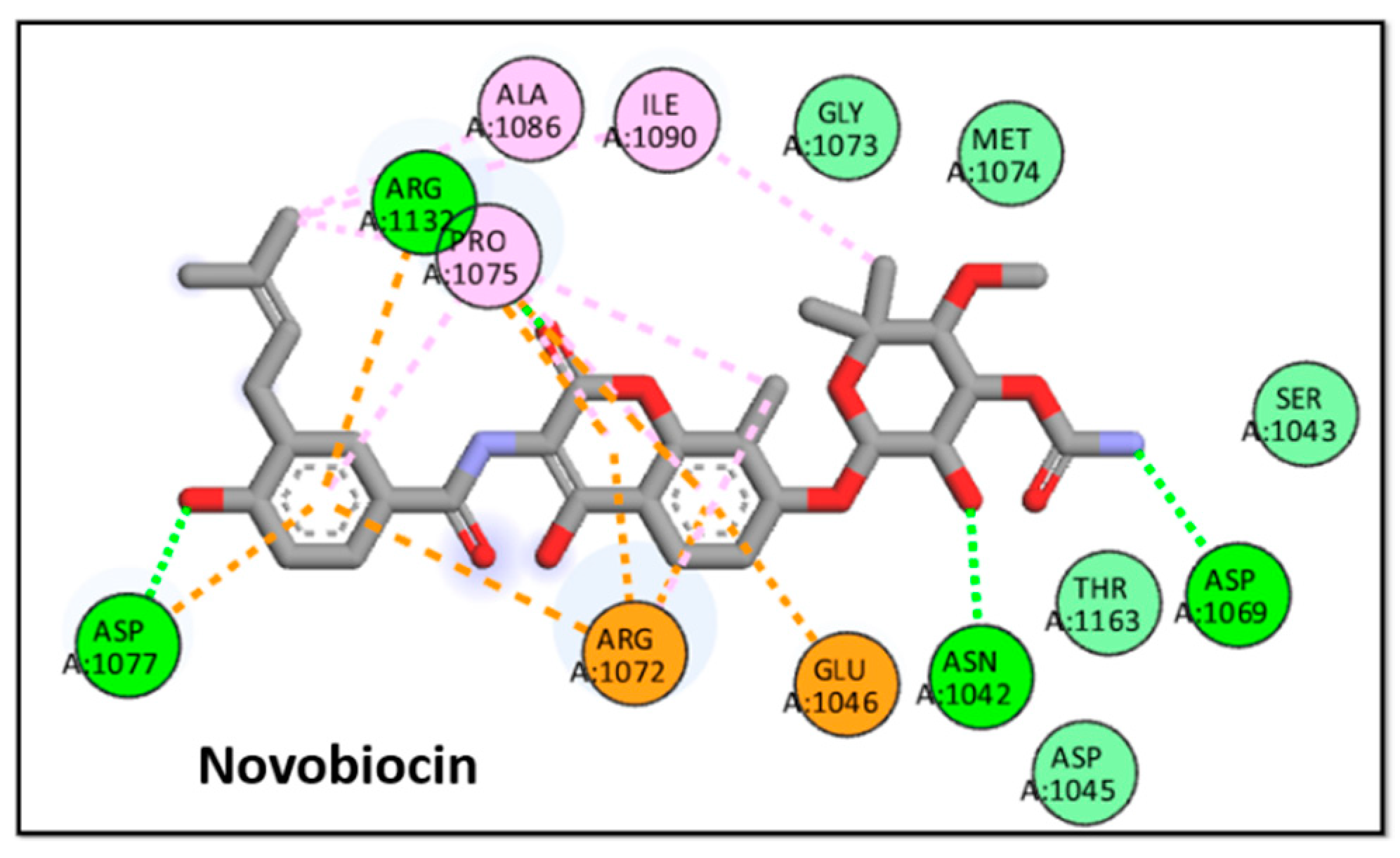

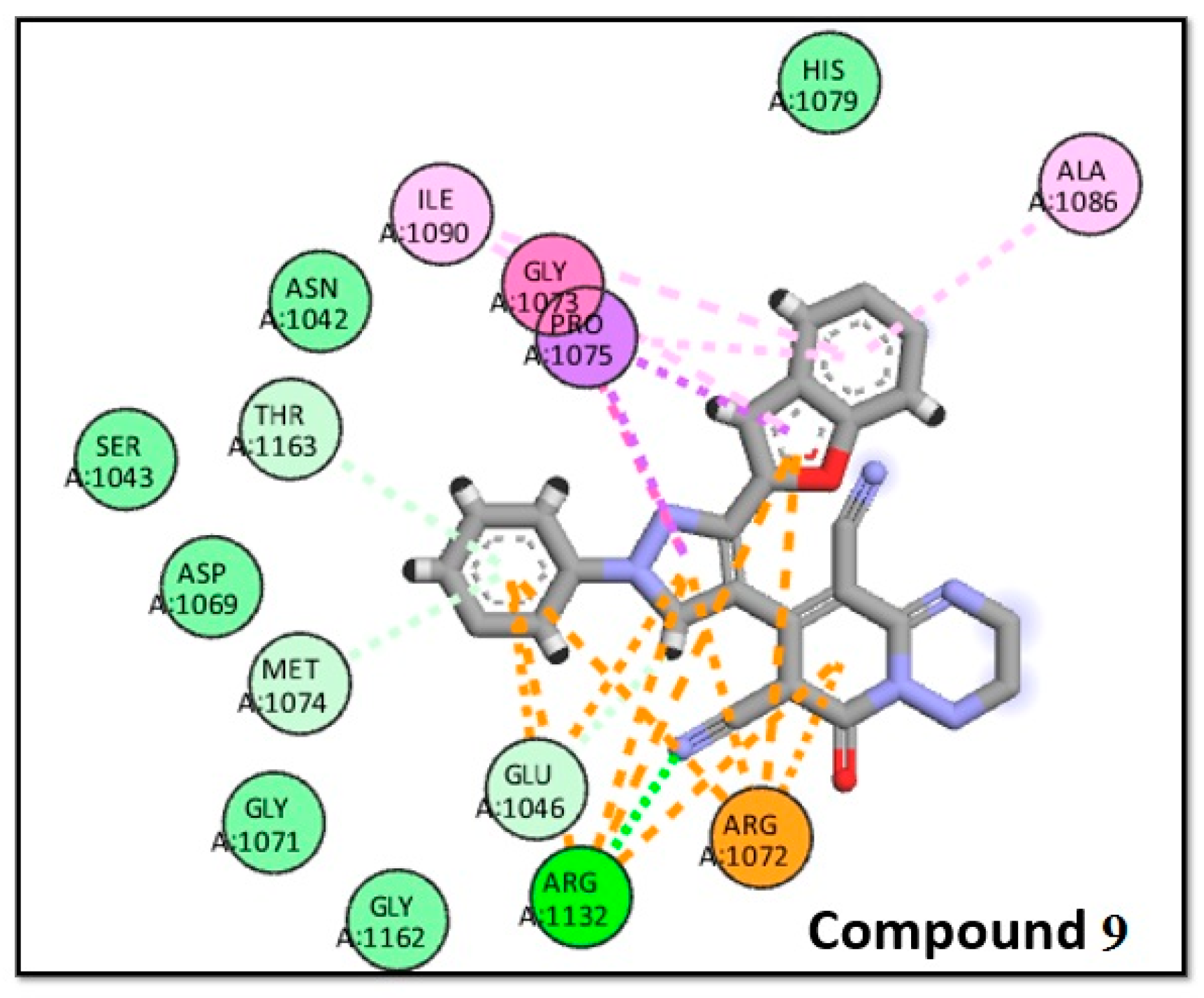

2.3.1. Molecular Docking

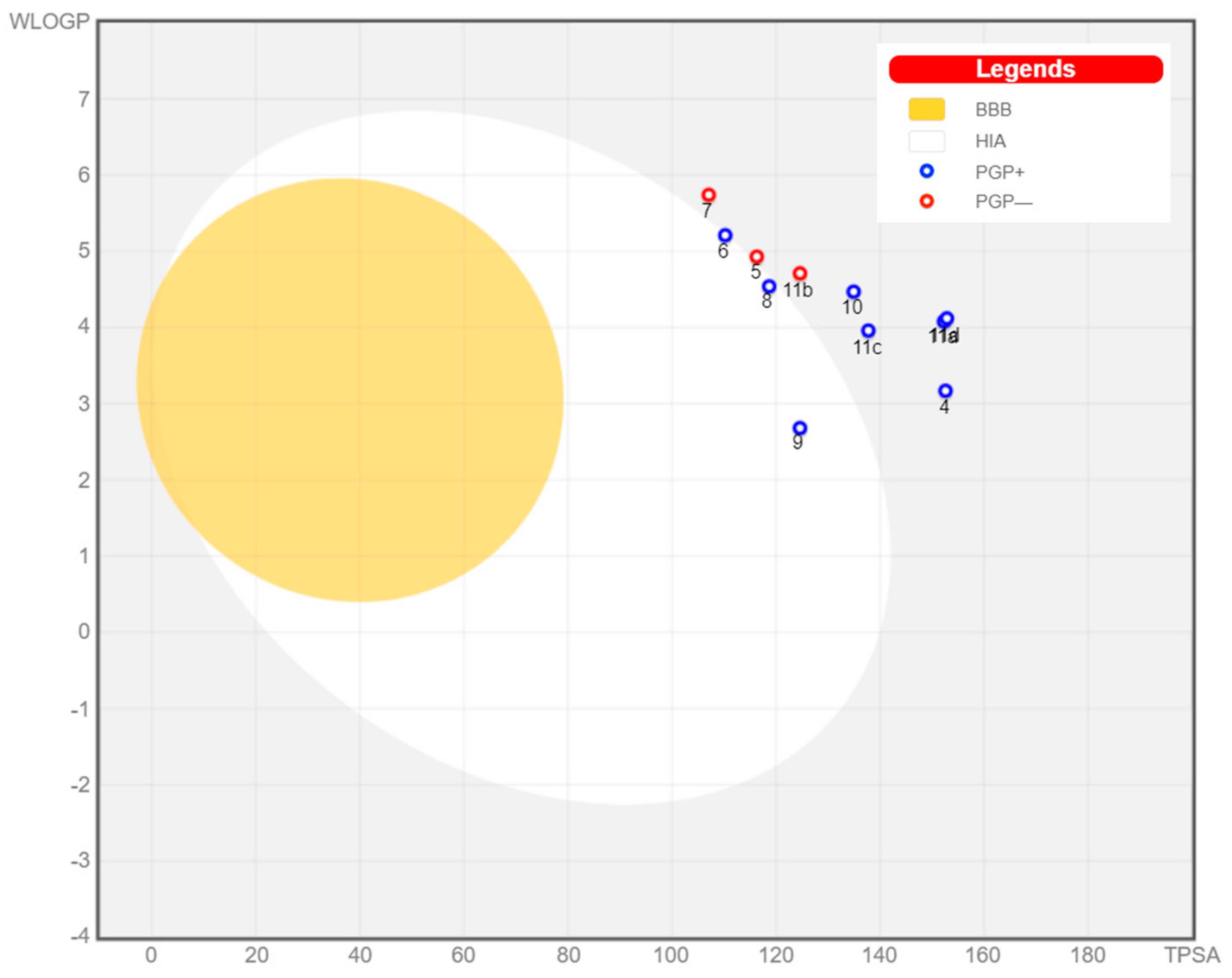

2.3.2. ADMET Studies

| Compound No. | Molecular Weight | # Rotatable bonds | # H-bond acceptors | # H-bond donors | Molar Refractivity | TPSA | Log P | GI absorption | BBB permeant | P-gp substrate | Lipinski #violations | Bioavailability Score | Synthetic Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 433.42 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 122.44 | 152.58 Ų | 2.33 | Low | No | Yes | 0 | 0.55 | 3.7 |

| 5 | 466.49 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 128.77 | 116.30 Ų | 3.78 | Low | No | No | 0 | 0.56 | 4.61 |

| 6 | 446.46 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 126.22 | 110.23 Ų | 3.92 | High | No | Yes | 0 | 0.55 | 4.44 |

| 7 | 476.53 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 134.92 | 107.07 Ų | 4.24 | Low | No | No | 0 | 0.56 | 4.78 |

| 8 | 434.45 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 121.31 | 118.68 Ų | 3.44 | High | No | Yes | 0 | 0.55 | 4.44 |

| 9 | 459.46 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 136 | 124.60 Ų | 2.67 | High | No | Yes | 0 | 0.55 | 3.96 |

| 10 | 499.48 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 138.1 | 134.91 Ų | 3.14 | Low | No | Yes | 0 | 0.55 | 3.92 |

| 11a | 611.61 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 175.16 | 152.29 Ų | 3.69 | Low | No | Yes | 2 | 0.17 | 5.12 |

| 11b | 555.97 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 160.69 | 124.60 Ų | 4.27 | Low | No | No | 1 | 0.55 | 4.66 |

| 11c | 525.52 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 152.92 | 137.74 Ų | 3.51 | Low | No | Yes | 1 | 0.55 | 4.72 |

| 11d | 527.56 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 153.56 | 152.84 Ų | 3.81 | Low | No | Yes | 1 | 0.55 | 4.60 |

3. Conclusions

4. Experimental protocols

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. N'-((3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-2-cyanoacetohy drazide (3)

4.1.2. 1,6-. Diamino-4-(3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1,2-dihydro-2-oxopyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile (4)

4.1.3. Ethyl-6-amino-4-(3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-cyano-2-methyl-4H-pyran-3-carboxylate (5)

4.1.4. 2-Amino-4-(3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-7-hydroxy-4H-chromene- 3-carbonitrile (6)

4.1.5. 2-Amino-4-(3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile (7)

4.1.6. 6-Amino-4-(3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3-methyl-1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole-5-carbonitrile (8)

4.1.7. 8-(3-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-6-oxo-1,3,4,6-tetrahydro-2H-pyrido[1,2-b][1,2,4]triazine-7,9-dicarbonitrile (9)

4.1.8. 3-Acetyl-7-(3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3,5-dihydro-2-methyl-5-oxo-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile (10)

4.1.9. 7-(3-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1,2,3,5-tetrahydro-2-(substituted)-5-oxo-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile 11a-d

4.1.10.1. 7-(3-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1,2,3,5-tetrahydro-2- (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-5-oxo-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile (11a)

4.1.11.2. 7-(3-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,2,3,5-tetrahydro-5-oxo-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile (11b)

5.1.12.3. 7-(3-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1,2,3,5-tetrahydro-2-(5- methylfuran-2-yl)-5-oxo-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile (11c)

5.1.13.4. 7-(3-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1,2,3,5-tetrahydro-5-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile (11d)

4.2. Biological Evaluation

4.2.1. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity

4.2.2. Human Red Blood Cell Stabilization Method

4.2.3. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

4.2.4. E. coli DNA Gyrase B Suppression Effect

4.2.5. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

4.2.6. Molecular Docking

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgments

Sample Availability

References

- Xue, W.; Zuo, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xia, J.; Cheng, M.; Yang, H. Bioisosteric replacement strategy leads to novel DNA gyrase B inhibitors with improved potencies and properties. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 147, 107314. [CrossRef]

- Princiotto, S.; Casciaro, B.; Temprano, A.G.; Musso, L.; Sacchi, F.; Loffredo, M.R.; Cappiello, F., Sacco, F.; Raponi, G.; Fernandez, V.P.;Iucci, T. The antimicrobial potential of adarotene derivatives against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 107227. [CrossRef]

- Vouga, M.; Greub, G. Emerging bacterial pathogens: the past and beyond. Clinical Microbiology and Infection (CMI). 2016, 22(1):12-21. [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Xuan, W.; Zhen, X..; He, L.; Lan, L.; Yang, S.; Wu, N.; Qin, J.; Qin, J.; Lan, J.; Lu, H.; Liang, C.; Li, Y.; Hamblin, M.R.; Huang, L. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for oral Candida infection in adult AIDS patients: A pilot clinical trial Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102310. [CrossRef]

- Chalkha, M.; Akhazzane, M.; Moussaid, F.Z.; Daoui, O.; Nakkabi A.; Bakhouch, M.; Chtita, S.; Elkhattabi, S.; Housseini, A.I.; El Yazidi, M. Design, synthesis, characterization, in vitro screening, molecular docking, 3D-QSAR, and ADME-Tox investigations of novel pyrazole derivatives as antimicrobial agents. New J Chem. 2022, 46(6), 2747-60. [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.W.; Millar, B.C.; Moore, J.E. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Br J Biomed Sci. 2023, 80, 11387. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ma, S. Recent development of membrane-active molecules as antibacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 184, 111743. [CrossRef]

- Richa, K.; Namarata, S.; Negi, A.; Kumar, E.; Zangrando, R.; Saini, V. Synthesis, characterization and utility of a series of novel copper(II) complexes as excellent surface disinfectants against nosocomial infections. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 13699–13711. [CrossRef]

- Founou, R.C.; Blocker, A.J.; Noubom, M.; Tsayem, C.; Choukem, S.P.; Dongen, M.V.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic: a Threat to Antimicrobial Resistance Containment. Future Sci. 2021, 7(8), FSO736. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Shakya R.; Asati, V.; Kurmi, B.D.; Verma, S.K.; Gupta, G.D.; Rajak, H. Furan and benzofuran derivatives as privileged scaffolds as anticancer agents: SAR and docking studies (2010 to till date). J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1299,137098. [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Y.U.; Batur, Ö.Ö.; Boulebd, H. Design, synthesis, theoretical studies, and biological activity evaluation of new nitrogen-containing poly heterocyclic compounds as promising antimicrobial agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1299, 137115. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, K.M. An update on benzofuran inhibitors: a patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2019, 29 (11), 841–870. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.A.; Dawood, K.M. Anticancer therapeutic potential of benzofuran scaffolds. RSC Adv. 2023, 13 (16), 11096–11120. [CrossRef]

- Khanam, H. Bioactive Benzofuran derivatives: A review. Eur j med chem. 2015, 97, 483-504. [CrossRef]

- Nevagi, R.J.; Dighe, S.N.; Dighe, S.N. Biological and medicinal significance of benzofuran. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 561–581. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Zahoor, A.F.; Kamal, S.; Raza, Z.; Bhat, M.A. Unfolding the antibacterial activity and acetylcholinesterase inhibition potential of benzofuran-triazole hybrids: Synthesis, antibacterial, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, and molecular docking studies. Molecules. 2023, 28(16), 6007. [CrossRef]

- El-Zahar, M.I.; Abd El-Karim, S.S.; Anwar, M.M. Synthesis and cytotoxicity screening of some novel benzofuranoyl-pyrazole derivatives against liver and cervix carcinoma cell line. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2009, 62, 189-199.

- Abd El-Karim, S.S.; Anwar, M.M.; Mohamed, N.A.; Nasr, T.; Elseginy, S.A. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking studies of novel benzofuran–pyrazole derivatives as anticancer agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2015, 63, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.M.; Abd El-Karim, S.S.; Mahmoud, A.H.; Amr, A.G.E.; Mohamed, A. A. A Comparative study of the anticancer activity and PARP-1 inhibiting Effect of benzofuran–pyrazole scaffold and its nano-sized particles in human breast cancer cells. Molecules. 2019, 24, 2413. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.J.; Idrees. M. Condensation-cyclodehydration of 2,4-dioxobutanoates: Synthesis of new esters of pyrazoles and isoxazoles and their antimicrobial screening. Der Pharm. Chem. 2014, 6, 406-410. https://derpharmachemica.com/vol6-iss6/DPC-2014-6-6-406-410.pdf.

- Liu, J.B.; Jiang, F.Q.; Jiang, X.Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.J.; Liu, W.L.; Fu. L. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of 3-methanone-6-substitutedbenzofuran derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 54 879-886. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, D.; Srinivas, G.V.; Kumar, A.; Gandhi. D.M. Microwave-assisted synthesis and evaluation of indole based benzofuran Scaffolds as antimicrobial and antioxidant Agents. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2016, 42, 560-566.

- Venkatesh, T.; Bodke, Y. D.; Joy, M.N.; Dhananjaya, B.L.; Venkataraman. S. Synthesis of some benzofuran derivatives containing pyrimidine moiety as potent antimicrobial agents. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 17, 75-86.

- Yu, Z.; Shi, G.; Sun, Q.; Jin, H.; Teng, Y.; Tao, K.; Zhou, G.; Liu, W.; Wen, F.; Hou. T. Design, synthesis and in vitro antibacterial/antifungal evaluation of novel 1-ethyl-6-fluoro-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-7(1-piperazinyl)quinoline-3-carboxylic acid derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 4726-4733. [CrossRef]

- Chougala, B.M.; Shastri, S.L.; Holiyachi, M.; Shastri, L.A.; More, S.S.; Ramesh. K.V. Synthesis, anti-microbial and anti-cancer evaluation study of 3-(3-benzofuranyl)-coumarin derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 4128-4136. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; Di, H.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, X.; Wei, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Sheng, C.; Lan, L.; Li. J. Discovery of potent benzofuran-derived diapophytoene desaturase (CrtN) inhibitors with enhanced oral bioavailability for the treatment of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 3215-3230. [CrossRef]

- Venkateshwarlu, T.; Nath, A.R.; Chennapragada. K.P. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of novel benzo[b]furan derivatives. Der Pharm. Chem. 2013, 5, 229-234. https://derpharmachemica.com/archive.html.

- Verma, R.; Verma S.K.; Rakesh, K.P.; Girish, Y.R.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Kumar, K.S.; Rangappa, K.S. Pyrazole-based analogs as potential antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistance staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and its SAR elucidation. Eur j med chem. 2021, 212, 113134. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Fayed, E.A.; Rizk, H.F.;Desouky, S.E.; Ragab, A. Hydrazonoyl bromide precursors as DHFR inhibitors for the synthesis of bis-thiazolyl pyrazole derivatives; antimicrobial activities, antibiofilm, and drug combination studies against MRSA. Bioorg chem. 2021, 116, 105339. [CrossRef]

- Laamari, Y.; Fawzi, M.; Hachim, M.E.; Bimoussa, A.; Oubella, A.; Ketatni, E.M.; Saadi, M.; El Ammari, L.; Itto, M.Y.; Morjani, H.; Khouili, M. Synthesis, characterization and cytotoxic activity of pyrazole derivatives based on thymol. J Mol Struct. 2024, 1297, 136864, . [CrossRef]

- Mortada, S.; Karrouchi, K.; Hamza, E.H.; Oulmidi, A.; Bhat, M.A.; Mamad, H.; Aalilou ,Y.; Radi, S.; Ansar, M.H.; Masrar, A.; Faouzi, M.E. Synthesis, structural characterizations, in vitro biological evaluation and computational investigations of pyrazole derivatives as potential antidiabetic and antioxidant agents. Sci Rep. 2024, 14(1), 1312. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Tahlan, S.; singh, K.; Verma, P.K. Synthetic Update on Antimicrobial Potential of Novel Pyrazole Derivatives: A Review. Curr. Org. Chem. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.A.; Abdel-Latif, E.; Abdel-Wahab, B.F.; Awad, G.E. Novel antimicrobial agents: fluorinated 2-(3-(benzofuran-2-yl) pyrazol-1-yl) thiazoles. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, J.; Kumar, H.V.; Harini, S.T.; Naik, N. Synthesis of benzofuran based 1, 3, 5-substituted pyrazole derivatives: As a new class of potent antioxidants and antimicrobials-A novel accost to amend biocompatibility. Bioorg. Med. Chem. lett. 2012, 22(14), 4773-7. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Karim, S.S.; Mahmoud, A.H.; Al-Mokaddem, A.K.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Alkahtani, H.M.; Zen, A.A.; Anwar, M.M. Development of a New Benzofuran–Pyrazole–Pyridine-Based Molecule for the Management of Osteoarthritis. Molecules 2023, 28, 6814. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, R.; Yuan, R.; Huo, L.; Gao, H.; Zhuo, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, S. Discovery of New Heterocyclic/Benzofuran Hybrids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of the Inhibitory Activity of Their Related Inflammatory Factors Based on NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(4), 3575. [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, J.; Kumar, H.V.; Harini, S.T.; Naik, N. Functionalized 3-(benzofuran-2-yl)-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4, 5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole scaffolds: A new class of antimicrobials and antioxidants. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S2685-96. [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, J.; Kumar, H.V.; Harini, S.T.; Naik, N. Synthesis of benzofuran based 1, 3, 5-substituted pyrazole derivatives: As a new class of potent antioxidants and antimicrobials-A novel accost to amend biocompatibility. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Let. 2012, 22(14), 4773-7. [CrossRef]

- Pommier, Y.; Leo, E.; Zhang, H.; Marchand, C. DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial drugs. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 421–433. [CrossRef]

- Toyting, J.; Miura, N.; Utrarachkij, F.; Tanomsridachchai, W.; Belotindos, L.P.; Suwanthada, P.; Kapalamula, T.F.; Kongsoi, S.; Koide, K.; Kim, H.; Thapa, J. Exploration of the novel fluoroquinolones with high inhibitory effect against quinolone-resistant DNA gyrase of Salmonella Typhimurium. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.C.; Jacoby, G.A. Topoisomerase inhibitors: fluoroquinolone mechanisms of action and resistance, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kerru, N.; Gummidi, L.; Maddila, S.; Gangu, K.K.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. A review on recent advances in nitrogen-containing molecules and their biological applications. Molecules. 2020, 25(8), 1909. [CrossRef]

- Aatif, M.; Raza, M.A.; Javed, K.; Nashre-ul-Islam, S.M.; Farhan, M.; Alam, M.W. Potential nitrogen-based heterocyclic compounds for treating infectious diseases: a literature review. Antibiotics. 2022, 11(12), 1750. [CrossRef]

- Egbujor, M.C.; Tucci, P.; Onyeije, U.C.; Emeruwa, C.N.; Saso, L. NRF2 Activation by Nitrogen Heterocycles: A Review. Molecules. 2023, 28(6), 2751. [CrossRef]

- Egbujor, M.C.; Tucci, P.; Onyeije, U.C.; Emeruwa, C.N.; Saso, L. NRF2 Activation by Nitrogen Heterocycles: A Review. Molecules. 2023, 28(6), 2751. [CrossRef]

- Peerzada, M.N.; Hamel, E.; Bai, R.; Supuran, C.T.; Azam, A. Deciphering the key heterocyclic scaffolds in targeting microtubules, kinases and carbonic anhydrases for cancer drug development. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 225, 107860. [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Y.U.; Batur, Ö.Ö.; Boulebd, H. Design, synthesis, theoretical studies, and biological activity evaluation of new nitrogen-containing poly heterocyclic compounds as promising antimicrobial agents. J Mol Struct. 2024, 1299, 137115. [CrossRef]

- Faleye, O.S.; Boya, B.R.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, I.; Lee, J. Halogenated Antimicrobial Agents to Combat Drug-Resistant Pathogens. Pharmacol Rev. 2024, 76(1), 90-141. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, H.S.; Naglah, A.M.; Al-Omar, M.A.; Moustafa, G.O.; Awad, H.M.; Bakheit, A.H. Synthesis, docking, computational studies, and antimicrobial evaluations of new dipeptide derivatives based on nicotinoylglycylglycine hydrazide, Molecules. 2020, 25 (16), 3589. [CrossRef]

- Princiotto, S.; Casciaro, B.; Temprano, A.G.; Musso, L.; Sacchi, F.; Loffredo, M.R.; Cappiello, F.; Sacco, F.; Raponi, G.; Fernandez, V.P.; Iucci, T. The antimicrobial potential of adarotene derivatives against Staphylococcus aureus strains, Bioorg Chem. 2024, 145, 107227. https://ejchem.journals.ekb.eg/.

- Gulcin, I.; Alici, H.A.; Cesur, M. Determination of in vitro antioxidant and radical scavenging activities of propofol. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53281–285. [CrossRef]

- Pervin, M.; Hasnat, M.A.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, D.H.; Jo, J.E.; Lim, B.O. Antioxidant activity and acetylcholinesterase inhibition of grape skin anthocyanin (GSA). Molecules. 2014, 19, 9403–9418. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Kim, J.; Kang, Y. M.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, M.; Ji-Hyun L., Young-Mog K., Myung-S., Min-Ho J., Chang-Bum A., Jae-Young J. Antioxidant activity and γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) content in sea tangle fermented by Lactobacillus brevis BJ20 isolated from traditional fermented foods. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 271–276. [CrossRef]

- Üstündağ, H. The role of antioxidants in sepsis management: a review of therapeutic applications. Eurasian Mol Biochem Sci. 2023, 2(2), 38-48.

- Murugasan, N.; Vember, S.; Damodharan, C. Studies on erythrocyte membrane IV. vitro haemolytic activity of Oleander extract. Toxicol Lett. 1981, 8, 33-38. [CrossRef]

- Chirumamilla, P.; Taduri, S. Assessment of in vitro anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antidiabetic activities of Solanum khasianum Clarke. Vegetos. 2023, 36(2), 575-82. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, U.A.; Phadke, A.S.; Nair, A.M.; Mungantiwar, A.A.; Dikshit, V.J.; Saraf, M.N. Studies on the anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Cedrus deodara (Roxb.) Loud. wood oil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 65(1), 21-7. [CrossRef]

- Oyedapo, O.O.; Akinpelu, B.A.; Akinwunmi, K.F.; Adeyinka, M.O.; Sipeolu, F.O. Red blood cell membrane stabilizing potentials of extracts of Lantana camara and its fractions. International Journal of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry (IJPPB). 2010, 2(4), 46-51. t http://www.academicjournals.org/ijppb.

- Chopade, S.G.; Kulkarni, K.S.; Kulkarni, A.D.; Topare, N.S. Solid heterogeneous catalysts for production of biodiesel from trans-esterification of triglycerides with methanol: a review. Acta Chimica and Pharmaceutica Indica. 2012, 2(1), 8-14.

- Hashem, H.E.; Amr, A.E.; Nossier, E.S.; Elsayed, E.A.; Azmy, E.M. Synthesis, antimicrobial activity and molecular docking of novel thiourea derivatives tagged with thiadiazole, imidazole and triazine moieties as potential DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV inhibitors. Molecules. 2020, 25(12), 2766. [CrossRef]

- Jakopin, Z.; Ilas, J.; Barancokova, M.; Brvar, M.; Tammela, P.; Dolenc, M.S.; Tomasic, T.; Kikelj, D. Discovery of substituted oxadiazoles as a novel scaffold for DNA gyrase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 130, 171-184. [CrossRef]

- Gjorgjieva, M.; Tomašič, T.; Barančokova, M.; Katsamakas, S.; Ilaš, J.; Tammela, P.; Mašič, L.P.; Kikelj, D. Discovery of benzothiazole scaffold-based DNA Gyrase B inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 8941−8954. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983, 65, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, M.Y.; Takamatsu, Y.; Ichinose, T.; Nakamura, K.; Itai, A. Effective handling of induced-fit motion in flexible docking. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2006, 63, 878–891. [CrossRef]

- Sharom, F.J. The P-glycoprotein efflux pump: How does it transport drugs?, J. Membr. Biol. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007 Vane JR, Botting RM. New insight into the mode of action of anti-inflammatory drugs. Inflamm Res (1995), 44:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lahuerta Zamora, L.; Perez-Gracia, M.T. Using digital photography to implement the McFarland method. J. R. Soc. Interface (JRSICU). 2012, 9(73), 1892-7. [CrossRef]

| Mean diameter of zones of inhibition (Mean ± SEM) (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd. No. |

Gram +ve Bacteria |

Gram -ve Bacteria |

Fungi | |||

| S. aureus ATCC 6538 |

B. cereus ATCC-11778 |

E. coli ATCC-25922 |

P. aeruginosa ATCC-27853 | F. solani |

C. albicans ATCC-10231 |

|

| 2 | 15 | 13 | 18 | 20 | 12 | 12 |

| 3 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 18 | 12 | 13 |

| 4 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 17 | 15 |

| 5 | 15 | 12 | 14 | 20 | 12 | 11 |

| 6 | 14 | 12 | 15 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 16 |

| 8 | 20 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 15 |

| 9 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 20 | 16 | 20 |

| 10 | 22 | 19 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| 11a | 15 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 15 | 0 |

| 11b | 20 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 15 | 16 |

| 11c | 20 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 12 | 15 |

| 11d | 20 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 19 |

| N٭ | 20 | 20 | 25 | 24 | - | - |

| C٭ | - | - | - | 20 | 14 | |

| Compd. No. |

Gram +ve Bacteria |

Gram -ve bacteria |

Fungi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus ATCC 6538 |

B. cereus ATCC-11778 |

E. coli ATCC-25922 |

P. aeruginosa ATCC-27853 | F. solani |

C. albicans ATCC-10231 |

|

| 4 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 27 | 25 |

| 7 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 27 | 30 |

| 8 | 20 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 35 | 25 |

| 9 | 2.50 | 4.65 | 5.79 | 17.60 | 20 | 16 |

| 10 | 3.49 | 8.80 | 4.65 | 20 | 16 | 14 |

| 11b | 5.11 | 8.60 | 8.69 | 17.0 | 15 | 16 |

| 11c | 5.90 | 7.79 | 16.0 | 16.90 | 15 | 19 |

| 11d | 5.11 | 15 | 16.0 | 20 | 15 | 19 |

| N* | 3.49 | 6.98 | 4.65 | 18.6 | - | - |

| C* | - | - | - | - | 20 | 14 |

| Compound No. | IC50 (mean±SEM) (µM) | |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DNA gyrase B | Cytotoxicity WI38 | |

| 9 | 9.80±0.21 | 163.3± 0.17 |

| 10 | 32.20 ± 0.10 | 170 ± 0.40 |

| Ciproloxacin | 8.03 ±0.03 | 86.2± 0.03 |

| Compound No. | Energy Score (kcal/mol.) |

Compound No. | Energy Score (kcal/mol.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | -8.2 | 10 | -8.7 |

| 5 | -8.4 | 11a | -8.4 |

| 6 | -8.6 | 11b | -8.1 |

| 7 | -8.1 | 11c | -7.9 |

| 8 | -8.3 | 11d | -8.2 |

| 9 | -8.9 | Novobiocin | -9.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).