1. Introduction

Nowadays, the rapid progression of artificial intelligence (AI) has a great impact on a variety of sectors. Contemporary AI technologies such as generative models and large language models (LLMs) are being absorbed into the educational practices. These advancements go beyond providing automated responses to students’ queries: development of lesson plans, creation of appropriate contents, active guidance of learning pathways, and just-in-time evaluation and feedback. This reform represents a significant shift away from traditional computer-based learning, which fell short of the interactive and adaptive capabilities of modern AI systems.

However, there has been considerable debate among educators about the use of AI in education. The proponents argue that AI can increase accessibility, personalise instruction, and expedite administrative work, freeing teachers to focus more on engaging with students (Chaudhry & Kazim 2021; Chen et al. 2020; Crompton & Burke 2023; Huang et al. 2023; Zou et al. 2020). On the other hand, the opponents express concerns that over-reliance on AI could diminish the human element of education, leading to social isolation among students and undermining the importance of human interaction in the learning process (Humble & Mozelius 2022; Selwyn 2019). In addition, there are worries about the potential replacement of teaching positions by AI systems as they develop the capability to perform tasks traditionally carried out by teachers (Hopcan et al. 2024).

Notwithstanding these divisive opinions, empirical research on the actual effects of AI integration on learners’ cognitive and affective states is notably scarce. A few of studies suggest that there will be gains in academic performance and engagement, but others highlight the risk of cognitive complacency, in which students may rely too much on AI technologies without properly comprehending the underlying ideas (Luckin 2018; Williamson & Eynon 2020; Zou et al. 2020). The emergence of generative AI conflicts with traditional educational paradigms, which stress rote memorisation and the gradual development of foundational learning skills. These traditional methods support students in steadily building their learning abilities. However, as AI can perform complex mathematical computations and problem-solving tasks, there is a risk that students may become overly reliant on it, bypassing the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Furthermore, the unexpectedly rapid advancement of AI has led to fears that it might lead to dystopian futures often depicted in films, where AI eventually rules human society. These worries often stem from misconceptions about AI’s potential and overlook the significant human influence embedded in these technologies. Ironically, the ideas, techniques, and processes of human learning have served as a major source of inspiration for the AI systems that are currently viewed as threats. Our understanding of how the human brain learns and adapts serves as the foundation for concepts like neural networks, reinforcement learning (RL), and adaptive algorithms (McCulloch & Pitts 1943; Rumelhart et al. 1986; Sutton & Barto 2018).

This study aims to address various debates and concerns surrounding AI by discussing its potential impact on education through several key topics. By comparing the learning processes of AI and humans, the study seeks to explore the significance of AI as an agent in teaching and learning, the changes in educational environments brought about by the advent of AI, and the resulting shifts in perspectives on human learning. Additionally, it addresses concerns about the potential replacement of teachers and students by AI. Through this exploration, the study hopes to offer insights into the essence of learning in response to changes in future educational environments.

2. Is AI Merely a Meaningless Statistical Machine?

There has been considerable discussion about the nature of AI and whether it is merely a statistical machine or something akin to a conscious being. Unlike previous technologies such as calculators, the internet, or tablets in the classroom, contemporary AI systems can interact with humans in ways that mimic consciousness. Many AI models today produce results in various fields that are astonishing and impressive, sometimes appearing to possess imagination and creativity akin to that of humans. These developments lead us to question whether AI is simply a statistical tool or something capable of understanding meaning, similar to a conscious entity. On the other hand, some critics dismiss AI as a machine that mindlessly produces results based on probability. In this vein, it is worth considering whether AI is closer to being an aware entity or just a complex tool. This question leads us to explore the nature of consciousness and how closely AI can replicate human-like thinking and behaviour.

2.1. AI, Consciousness, and Reasoning

In order to understand how both humans and AI learn, it is crucial to effectively perceive and interpret stimuli from the external world, making judgements and predictions appropriately. In this process, perceiving and responding to the external world is what we call consciousness. To obtain the right answers investigated in this study, it is essential to define consciousness and understand its characteristics.

Consciousness is one of the significant topics discussed in the field of neuroscience, and one of the most prevalent theories is the Global Workspace Theory (GWT) advocated by Bernard Baars (1988). This theory suggests that consciousness arises from the integration of information in the brain through a “global workspace.” In this model, the brain processes information in parallel through various specialised modules that operate unconsciously (Edelman 1990). When information needs to be consciously accessed or shared across different parts of the brain, it is broadcast through this global workspace, allowing it to be accessed by other cognitive systems. This broadcasting process (reticular activating system) is thought to be what we experience as conscious awareness (Kandel et al. 2012; Taran et al. 2023). The theory highlights the role of attention in selecting information to enter the global workspace and the importance of working memory in maintaining this information. GWT posits that consciousness facilitates flexible decision-making and problem-solving by allowing information to be combined and manipulated in novel ways.

Another prominent theory is the Integrated Information Theory. According to Tononi (2008), consciousness arises as a consequence of information being integrated into a system characterised by a high level of informational integration that cannot be broken down into its component parts. Whilst the Global Workspace Theory holds a materialist view of consciousness, Integrated Information Theory regards consciousness an outcome of physical networks of neurons. Koch (2004) investigates the neural correlates of consciousness, concentrating on pinpointing certain brain regions and functions responsible for conscious experience. He argues that the brain’s capacity to process complex information is fundamental to consciousness and that specific neural circuits are crucial for generating awareness.

Despite advances in understanding human consciousness, AI models, including LLMs like GPT-4, do not possess consciousness in the same way humans do (Buttazzo & Manzotti 2008). AI is devoid of subjectivity and self-awareness, functioning solely on algorithms and data. However, LLMs challenge the notion that AI is merely a collection of statistical computations thanks to their sophisticated processing abilities. Large-scale datasets are used to train LLMs so they can produce responses that are contextually relevant and coherent, much like human language. Even though their results are based on statistical correlations, they exhibit a higher order of thinking than mere computations. This has led to discussions about AI’s capacity for human-like thinking and its implications for understanding intelligence (Russell & Norvig 2021).

Studies on AI reasoning capabilities articulate how these models might support human learning. Research indicates that LLMs can function as efficacious pedagogical instruments by furnishing students with tailored feedback and elucidations. These models improve the learning process by identifying knowledge gaps and providing content that is specifically suited to the learner (Holstein et al. 2018, 2019). Because AI can mimic reasoning and decision-making processes, it can provide insights into cognitive processes and be used to investigate ways in which AI can enhance human learning (Luckin 2017). AI systems have also been used to simulate and comprehend human thought processes. There are similarities between the ways that AI learning mechanisms and human cognition approach adaptation and problem-solving, according to the research (Laird et al. 2017). This convergence highlights the potential benefits of integrating AI into educational contexts, where it can support learners in developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

The ability of AI to reason can improve our knowledge of human cognition by producing models that closely resemble some features of human mental processes. This continuous investigation of the advantages and disadvantages of AI flourishes the discussion around consciousness and intelligence by upending preconceived notions and broadening our definition of what it means to think.

2.2. Similarities between Human and AI Learning

Our knowledge of human learning and cognition has had a major impact on the development of AI. The functions and structure of neural systems have a great contribution for the development of AI algorithms, which were inspired by scientific knowledge from biophysics and neuroscience. The fundamental principle of machine/deep learning in these days is based on Hebb’s rule suggested by Donal Hebb (1949). Hebb’s rule explains that when two neurons are activated at the same time, the connection between them becomes stronger. This principle helps to explain how learning and memory formation occur in the brain, as repeated simultaneous activation leads to more robust neural pathways. According to this theory, learning happens in the brain when synaptic connections between neurons that are engaged at the same time get stronger (Kim & Sankey, 2023). Hebb’s rule established the foundation for neural network models in AI, where the weights between nodes are modified based on input data.

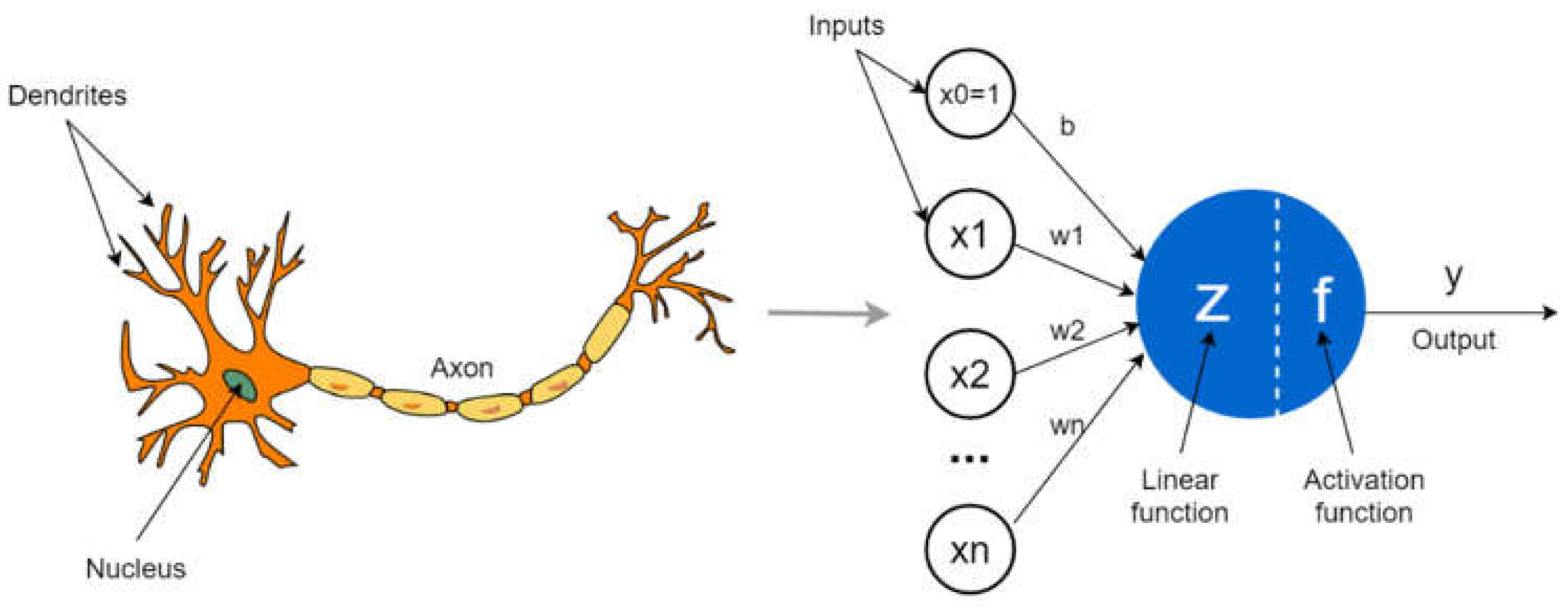

The perceptron, first introduced by Frank Rosenblatt, is an early neural network model that mimics the operation of a biological neuron (Rosenblatt 1958). Similar to human neurons, the perceptron processes inputs received from its dendrite-like input nodes, aggregates them, and passes the signal through an axon-like connection to the output node. The strength of each connection is modulated by adjustable weights, which determine the influence of each input on the final output. This process is guided by an activation function, analogous to a neuron’s threshold, which decides whether the perceptron will fire an output signal based on the weighted sum of its inputs. The perceptron was a significant advancement toward creating AI systems that imitate human learning processes, illustrating key principles of neural processing (Rosenblatt 1958).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the structure of a neuron and a perceptron.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the structure of a neuron and a perceptron.

Deep neural network training requires backpropagation. In order to modify the weights, the error gradient must be propagated backward through the network. This process is comparable to how the human brain grows better at understanding things over time by learning from mistakes. With the help of this approach, neural networks can improve their prediction accuracy by fine-tuning their parameters in response to training failures (Rumelhart et al. 1986).

The term “neuroplasticity” describes the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself throughout life by creating new neural connections. Adaptive AI systems, which exhibit a sort of flexibility akin to human learning, have been prompted by this concept and are capable of modifying their parameters to improve their performance (Kandel et al. 2012). Neural networks employ dropout to cope with the overfitting problem. Randomly “dropping out” units is what it entails throughout training. By preventing the network from being overly reliant on any one node, this technique fosters robust learning. The idea is similar to how the brain might reinforce several neural pathways in order to avoid depending too much on one particular neural circuit (Srivastava et al. 2014).

Deep learning (DL) models emulate the stratified structure of the human cerebral cortex by employing numerous layers to process data. In the same way that distinct cortical layers analyse sensory data, each layer in a DL model isolate features from the input data. The cerebral cortex is composed of multiple interconnected layers and regions, with complex neuronal connections facilitating communication and integration of information. Similarly, DL networks consist of interconnected layers, where each layer processes and transforms the input data before passing it to the next. The close resemblance between biological and artificial intelligence learning processes is highlighted by this structural similarity, demonstrating how both systems efficiently extract and integrate information from their environments (LeCun et al. 2015).

Only with a little amount of training data, AI models can provide precise predictions or judgments such as one-shot or few-shot learning techniques, exhibiting learning efficiency similar to that of human beings. These methods allow AI to generate outputs from a small number of examples, mirroring the flexibility of human cognition, which is something that human learners frequently accomplish (Lake et al. 2017). The human mirror neuron system aids in learning by activating during both observation and execution of actions, enabling quick generalisation and imitation. Mirror neurons, located primarily in the premotor and parietal cortices, facilitate this process by responding to observed behaviours, allowing humans to learn new skills and understand others’ actions with minimal direct experience. This system plays a crucial role in social learning and empathy, reflecting the way AI models can learn efficiently from limited examples (Gallese & Goldman 1998; Rizzolatti & Craighero 2004).

DL models are frequently criticised for being opaque, or “black boxes,” due to their complex structure of many nodes and layers, making it challenging to track all computations. This term refers to systems whose internal operations are difficult to comprehend or explain. The opacity of DL models makes it difficult to understand how they come to specific conclusions or predictions. This problem complicates the direct comparison of AI processes and human cognition because the fundamental mechanisms of AI remain obscure. However, Explainable AI (XAI) has recently made strides toward addressing this issue. XAI approaches aim to increase the transparency of AI systems by revealing the decision-making process of models. Techniques such as feature attribution and model visualization help clarify the elements driving AI predictions, bridging the comprehension gap between humans and machines. Additionally, a new field called “in-context learning” aims to improve the interpretability of AI by providing examples and cues to help AI systems complete tasks within a specific context. This method enables more natural interactions with AI, as humans can guide the system’s learning and decision-making processes (Samek et al. 2017).

According to the neuroscientific notion of “predictive processing,” the brain continuously creates and modifies predictions regarding sensory inputs. The actual sensory data is compared to these predictions, and any differences (prediction mistakes) are utilized to improve the predictions made in the future. Adaptive behaviour and effective information processing are made possible by this system. AI systems use predictive processing methods as well, especially DL models. For instance, generative models such as GPT-4 forecast the subsequent word in a sentence by analysing the context of the words that come before it. The production of writing that is both logical and appropriate for the situation is made possible by this predictive ability (Friston, 2005). The idea that predictive processing in AI has similarities to human cognition is supported by research comparing AI learning with human cognitive processes, such as EEG investigations. These findings emphasize the convergence of biological and artificial learning systems by demonstrating how humans and AI use comparable mechanisms to predict and respond to inputs (van Gerven et al. 2009).

Research indicates that AI systems are converging on predictive processing architectures similar to those used in the human brain. Schrimpf et al. (2021) highlight that specific artificial neural networks (ANNs) approximate the brain’s language processing mechanisms through predictive modelling. Additionally, Luczak et al. (2022) propose a model where neurons themselves act as predictive units, aligning closely with how DL models operate. Schütt et al. (2024) explore efficient coding in the brain, which parallels how AI optimises information processing through prediction. These studies provide compelling evidence that both artificial and biological intelligences engage in similar predictive activities, reinforcing the notion that predictive processing is a shared mechanism for processing complex information. This convergence underscores the potential for AI to model and possibly enhance human cognitive processes, bridging the gap between artificial and biological systems.

Knowing what “thinking” is all about is essential to appreciating AI’s potential. In his ground-breaking book “Thought and Language,” Lev Vygotsky stated that thought and language are distinct entities, but they are intricately intertwined and rarely exist independently of each other. Language, in his view, offers the structure for cognition and makes it possible for sophisticated cognitive processes (Vygotsky 1986). Even though AI does not possess consciousness, today’s multimodal AI can perform mathematical calculations, logical reasoning, and make predictions in various scientific contexts, all centred around language. Even a novice user, not an AI expert, may produce different forms of representations once he/she gives a prompt to the system. Contemporary AI models pretend to be a thinking agent by showing up excellent performances based on texts, according to Vygotsky’s perspective. This suggests that AI’s capability to engage in complex interactions is reminiscent of cognitive processes.

In conclusion, the idea that AI is merely a statistical machine and fundamentally different from humans is challenged by its ability to emulate and integrate human-like functions in various ways. Therefore, rather than dismissing AI as a mere tool, it is crucial to examine the similarities and differences between humans and AI closely. By doing so, we can understand the complexities of both systems and explore new approaches to enhance learning and cognitive development.

3. Does AI’s Emergence Undermine Human Learning?

The emergence of AI is acting as a pivotal moment for a significant shift in long-established learning practices. Behaviourist and constructivist learning theories have dominated educational debate for the past century. Both constructivism—which emphasises the active production of knowledge through interaction with the environment—and behaviourism—which focuses on observable behaviours and stimuli-response relationships—have contributed significantly to our understanding of the learning process. But the speed at which AI is being incorporated into classrooms demands that these theories be re-examined, particularly from the standpoints of cognitive science and neuroscience.

According to behaviourism, a theory developed by psychologists such as Skinner and Watson, learning involves conditioning to acquire new behaviours (Schneider & Morris 1987). This theory is based on classical and operant conditioning, which suggest that behaviours can be shaped by rewards or penalties to reinforce desirable actions or reduce undesirable ones. Behaviourism has significantly influenced educational methods by emphasizing reinforcement, repetition, and the use of stimuli to elicit desired responses. RL represents the intersection of behaviourism and AI. Alan Turing’s early concept of AI as systems capable of experiencing pleasure and pain laid the foundation for this approach, suggesting that machines could learn in a manner akin to living organisms (Turing, 1950). In RL, an AI agent learns decision-making skills by interacting with its environment to maximise cumulative rewards. This approach mirrors the behaviourist method of learning through rewards and punishments. AI agents use RL algorithms to navigate complex environments, discover optimal strategies, and improve performance over time through trial and error (Sutton & Barto 2018).

Although behaviourism has made a substantial contribution to our understanding of how learning occurs, it is sometimes criticized for its oversimplified conception of human intellect as a blank slate (tabula rasa). The complexity of innate cognitive processes and individual variability in learning capacities may be overlooked by this viewpoint. Similarly, the complex relationships within cognitive processes may not be adequately explained by certain interpretations of the Global Workspace Theory that centre on materialistic components of awareness. However, DL in AI highlights the complexity and diversity inherent in learning, implying that behaviourism only partially reflects the full picture of human cognition (Dehaene 2014). DL can yield a variety of outcomes from similar training data. Furthermore, the application of RL in AI raises ethical concerns, especially in automated decision-making systems, where the impact of algorithmic decisions on individuals and society must be carefully considered.

Proponents of constructivism, such Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, contend that through interactions and experiences, students actively create their own knowledge and understanding of the outside world. According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, children learn by absorbing new information and integrating it into their preexisting cognitive structures as they move through the learning process (Piaget 1977). With the introduction of ideas like the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and scaffolding, Vygotsky’s social constructivism addresses the importance of social interaction and cultural context in learning (Vygotsky 1978).

The Information Processing Theory, which likens the human mind to a computer that processes, stores, and retrieves information, is closely related to cognitive perspectives on learning. This approach places a strong emphasis on the learner’s active participation in creating knowledge via interaction and engagement. Although constructivism has gained widespread acceptance, it is criticised for ignoring the importance of external tools and technologies in contemporary learning contexts and for failing to address subconscious variables that affect learning. It is also restricted to biological brains. State-of-the-art technology, such virtual reality platforms and intelligent tutoring systems, opens new possibilities for experiential learning outside of traditional classroom settings. By offering options for customised learning experiences that adjust to unique learning preferences and styles, these technologies improve constructivist methods. As digital tools and AI technologies become increasingly integral to the learning process, constructivist practices must evolve to incorporate these advancements, enhancing traditional methods of exploration, problem-solving, and social interaction (Anderson 1983; Papert 1993).

George Siemens and Stephen Downes developed the connectivism hypothesis, which expands on the idea of learning to encompass networks of connections between individuals as well as digital tools and information. In the digital age, where learning takes place across a web of interconnected nodes and information sources, this theory captures the shifting terrain of knowledge acquisition (Siemens 2005). The Integrated Information Theory (IIT) of consciousness, which holds that integrated information inside a system is the source of consciousness, is strongly associated with connectivism. According to IIT, cognitive processes are not limited to individual brains but rather are dispersed over networks of interacting components. This viewpoint is consistent with connectivism, which highlights the role that networks and connections have in the learning process (Tononi 2004).

The widespread use of digital technology has blurred the boundaries of cognitive thinking by extending our capabilities through external connections. These abilities are expanded by AI, which provides important benefits in addressing difficult, open-ended problems quickly. Traditional assessment techniques need to change as learning paradigms do, emphasising people’ capacity to navigate and capitalise on these interconnected networks rather than only focusing on discrete problem-solving abilities (Luckin 2018). Connectivism raises concerns about data privacy and the veracity of information inside digital networks, stressing the value of digital literacy and the capacity to critically assess information from a variety of sources. Teachers and students need to be prepared with the abilities needed to use and manage these networks in an ever-changing information environment. Effective evaluation must now consider individuals as part of interconnected networks, emphasising their ability to navigate and leverage these connections. AI’s role in education should not be seen as undermining human learning but as augmenting it by providing new tools and methods for knowledge acquisition and application (Siemens 2005).

4. Will AI Ultimately Replace Teachers and Render Learners Obsolete?

Concerns about AI potentially replacing teachers and diminishing the role of human learners have arisen due to the rapid progress in the AI field. To address these concerns, it is important to understand the distinct roles of AI and human instructors, as well as the unique qualities of human learning. Although AI can enhance learning environments, it is unlikely to fully replace the unique contributions of human teachers or the active engagement of students.

AI currently cannot fully satisfy the diverse range of skills and qualities that human educators bring to the learning process: empathy, emotional intelligence, and the ability to form strong connections with students. Instructors can adjust their teaching methods in real-time by responding to students’ emotional cues and immediate feedback. Beyond the capabilities of AI, human teachers provide mentorship, inspire creativity, and cultivate critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Social Learning Theory emphasises the significance of observational learning, in which pupils acquire skills by observing and imitating others (Bandura 1977). According to this theory, which highlights the importance of social interactions in the learning process, students benefit from having access to role models and opportunities for group projects. Teachers play a critical role in this process by modelling appropriate behaviour, leading group activities, and stimulating discussions to help students improve their social and cognitive abilities. AI can assist teachers by managing administrative duties, generating personalised learning materials, and providing data-driven insights into student performance. However, the relational and motivational components of teaching firmly remain in the human realm. AI cannot replace human teachers because it lacks the ability to provide the physical presence, diverse perceptions, and sensory responses that are essential for observational learning and imitation. For instance, while AI can grade assignments and offer instant feedback, it cannot understand the nuances of a student’s emotional state or provide the encouragement and support needed to foster a positive learning environment. Additionally, AI’s inability to physically interact and engage with students limits its role in modelling and guiding social behaviours.

By enabling customised training, giving personalised education, and granting access to a multitude of tools and information, AI has the potential to drastically improve the educational experience. AI-driven systems enable more individualised learning by optimising instructional content to match each student’s needs. These platforms have the ability to adjust to each student’s unique learning rate, offer practice tasks that are specifically tailored to them, and pinpoint areas that require more help. The idea of lifelong learning is further supported by AI, which increases accessibility to education. People who do not have access to traditional educational settings can nonetheless benefit from learning opportunities offered by online courses, virtual classrooms, and AI tutors. By democratising education, we can close the achievement gap and provide students the skills they need to thrive in a world that is changing quickly. However, careful evaluation of AI’s limits is necessary for its effective application in education. Although AI is capable of processing and analysing enormous volumes of data, it is not as sensitive to context and subtleties as humans are. This restriction may make it difficult to understand complicated or ambiguous information and may force one to rely more on surface-level comprehension than on in-depth cognitive engagement.

Although AI shows up impressive capabilities, it cannot replace human learners. A key distinction between AI and humans is the ability to make independent decisions and possess self-awareness. Despite AI’s advancements in fields such as autonomous driving, automated navigation, and disease diagnosis, the widespread adoption of these technologies is often delayed due to questions of accountability and decision-making responsibility. Humans are uniquely distinguished by their self-awareness, ability to make decisions, and accountability, which are qualities that set them apart from other beings and objects. Although AI can seem to respond with a semblance of consciousness, it lacks meaning without human oversight and judgment. The increasing prominence of AI is also related to the concept of distributed cognition. Distributed cognition, a theory in cognitive science and psychology, posits that cognitive processes are not limited to an individual’s mind but are distributed across people, tools, artefacts, and the environment (Hutchins, 1995). This means that cognition extends beyond the biological brain to include the body, external objects, and other entities, with AI serving as a cognitive component interacting with humans. However, the ultimate responsibility for assessing and making decisions about the value of information rests with humans. Therefore, traditional learning remains essential, as the ability to evaluate and understand the appropriateness of AI outputs is critical. Learning is still indispensable because AI’s effectiveness can differ significantly depending on whether it is utilised by experts or novices.

AI in education should be viewed as a way to enhance human learning rather than to replace it. Learning environments can be made more dynamic and productive by educators by taking use of AI’s skills in data analysis and targeted training. The secret is to employ AI as a tool to augment and supplement human instruction and learning. Studies have indicated that the integration of AI tools with conventional teaching methods in blended learning settings can enhance student performance. AI, for instance, can give students immediate feedback on their assignments, enabling them to spot and fix mistakes right away. Simultaneously, educators can make use of AI-generated insights to guide their teaching approaches and offer focused assistance to students who require it most. AI can also help with collaborative learning by putting students in touch with international experts and peers. Students can collaborate on projects, have meaningful discussions, and exchange ideas in virtual classrooms and online discussion boards. These exchanges can promote a sense of belonging and community while also assisting in the development of critical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

In summary, AI has the potential to revolutionize education by offering individualized learning experiences and increasing accessibility to educational materials, but it is unlikely to supplant human teachers or make students obsolete. Human educators possess certain abilities that cannot be replaced, such as empathy, flexibility, and the capacity to uplift and motivate students. We can improve student learning, assist educators, and build a more just and efficient educational system by incorporating AI into the educational process. The best results for students can be achieved through the complementary use of artificial and human intelligence in education, which is the way of the future.

5. Conclusions and Implications

The introduction of cutting-edge technologies, led by AI, is creating new opportunities in education but also poses unforeseen challenges. This has led to differing opinions among educational experts regarding the integration of AI. This study seeks to explore the role of AI in education, focusing on its potential benefits and inherent limitations. By examining these aspects, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of how AI can be effectively utilised within educational systems while acknowledging the concerns that accompany its adoption.

Re-conceptualisation of conventional learning theories and methods is necessary in light of the opportunities and problems that the integration of AI into educational systems brings. The analysis of AI’s place in respect to human learning highlights several important points.

The debate over whether AI is merely a statistical tool or something akin to a conscious being highlights AI’s capacity to mimic human-like thinking and decision-making processes, especially in fields like autonomous driving and disease diagnosis. Despite lacking consciousness, AI models like LLMs exhibit sophisticated reasoning abilities that challenge traditional views of intelligence. The discussion involves concepts such as the Global Workspace Theory and Integrated Information Theory, which explore consciousness and cognition, drawing parallels with AI’s capabilities. AI can support human learning by providing tailored feedback and insights into cognitive processes, showing potential for educational applications. Moreover, the development of AI has implications for traditional educational theories like constructivism and behaviourism, which must adapt to incorporate digital tools and AI technologies. Concepts like distributed cognition, where cognitive processes extend beyond the individual to include interactions with AI and the environment, further emphasize AI’s role as a cognitive component. However, AI’s limitations in self-awareness and emotional understanding mean that the ultimate responsibility for decision-making rests with humans. By acknowledging AI’s strengths and weaknesses, we can explore how it complements human learning and cognition, leading to innovative approaches to education and problem-solving.

The emergence of AI is transforming long-standing educational practices and theories, challenging traditional behaviourist and constructivist approaches. Behaviourism, which emphasises conditioning through rewards and punishments, has influenced AI through reinforcement learning, where AI systems learn by maximising cumulative rewards, similar to behaviourist principles. However, AI also highlights the limitations of behaviourism by demonstrating the complexity of learning processes that go beyond simple stimulus-response relationships. Constructivism, which focuses on active knowledge creation through interaction and experience, must evolve to incorporate AI and digital technologies, enhancing experiential learning beyond traditional classrooms. The development of connectivism emphasises learning as a networked process involving digital tools and information, aligning with theories like Integrated Information Theory, which sees cognitive processes as distributed across networks. As digital technology and AI blur the boundaries of cognitive thinking, education must adapt to equip learners with the skills to navigate interconnected networks and critically assess information. AI should be viewed not as undermining human learning but as a tool that augments it, providing new methods for knowledge acquisition and application while highlighting the need for updated assessment techniques and digital literacy (Siemens 2005; Luckin 2018).

The rapid development of AI in education raises concerns about its potential to replace teachers and diminish the role of human learners. However, AI cannot replicate the unique skills and qualities of human educators, such as empathy, emotional intelligence, and the ability to build strong connections with students. Social Learning Theory emphasises the importance of these human interactions for effective learning. While AI can assist in managing tasks and providing personalised education, it lacks the ability to engage physically and emotionally with students. AI offers significant benefits in customising learning experiences, improving accessibility, and enhancing educational environments by leveraging its data processing capabilities. Despite this, AI’s limitations in understanding complex contexts and providing emotional support mean that traditional human-led learning remains essential. AI should be viewed as a tool to augment human learning rather than replace it, offering new methods for knowledge acquisition and enhancing educational experiences. By integrating AI with traditional teaching, educators can create more dynamic and effective learning environments. Ultimately, the complementary use of AI and human intelligence promises to enrich education, providing students with critical thinking and problem-solving skills while ensuring that human educators continue to play a vital role.

The integration of AI into education represents not merely the adoption of new technologies but a profound shift in how we perceive learning itself. As AI continues to evolve, it is essential to scrutinise its impact on both educators and learners carefully. While AI holds the promise of personalised education and unprecedented access to resources, it also presents challenges that require vigilant oversight. We must evaluate whether these technologies genuinely enhance educational outcomes or inadvertently create new barriers. This evaluation should include examining potential biases within AI algorithms and ensuring equitable access for all students. A thorough understanding of these dynamics is crucial for fostering an educational environment that leverages AI’s strengths while mitigating its limitations.

Moreover, the future of education with AI opens up numerous avenues for research. There is potential to explore how AI can support diverse learning styles, assist in teaching complex problem-solving skills, and facilitate collaborative learning environments. Research can also investigate the long-term effects of AI integration on student engagement and achievement, examining how these tools impact learners from various backgrounds. Additionally, interdisciplinary studies that combine insights from cognitive science, education, and computer science can provide a more holistic understanding of AI’s role in learning. By pursuing these research opportunities, educators and policymakers can ensure that AI serves as a transformative force that enriches the educational landscape, ultimately preparing students for a rapidly changing world.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (RS-2024-00335268).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that it does not involve the collection or analysis of data from human or animal subjects. The research focuses on the theoretical and conceptual analysis of artificial intelligence in educational settings.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- (Anderson 1983) Anderson, J. R. 1983. The Architecture of Cognition. Psychology Press.

- (Baars 1988) Baars, B. J. 1988. A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press.

- (Bandura 1977) Bandura, A. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall.

- (Buttazzo and Manzotti 2008) Buttazzo, G., and R. Manzotti. 2008. “Artificial Consciousness: Theoretical and Practical Issues.” Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 44 (2): 79–82. [CrossRef]

- (Chaudhry and Kazim 2021) Chaudhry, M. A., and E. Kazim. 2021. “Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIEd): A High-Level Academic and Industry Note 2021.” AI and Ethics 2: 157–165. [CrossRef]

- (Chen, Chen, and Lin 2020) Chen, L., P. Chen, and Z. Lin. 2020. “Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review.” IEEE Access 8: 75264–75278. [CrossRef]

- (Crompton and Burke 2023) Crompton, H., and D. Burke. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: The State of the Field.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 20: 22. [CrossRef]

- (Dehaene 2014) Dehaene, S. 2014. Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts. Penguin Books.

- (Edelman 1990) Edelman, G. 1990. The Remembered Present: A Biological Theory of Consciousness. Basic Books.

- (Friston 2005) Friston, K. 2005. “A Theory of Cortical Responses.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 360 (1456): 815–836. [CrossRef]

- (Gallese and Goldman 1998) Gallese, V., and A. Goldman. 1998. “Mirror Neurons and the Simulation Theory of Mind-Reading.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2 (12): 493–501. [CrossRef]

- (Hebb 1949) Hebb, D. O. 1949. The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. Wiley.

- (Holstein, McLaren, and Aleven 2018) Holstein, K., B. M. McLaren, and V. Aleven. 2018. “Student Learning Benefits of a Mixed-Reality Teacher Awareness Tool in AI-Enhanced Classrooms.” Artificial Intelligence in Education 2018.

- (Holstein, McLaren, and Aleven 2019) Holstein, K., B. M. McLaren, and V. Aleven. 2019. “Co-Designing a Real-Time Classroom Orchestration Tool to Support Teacher–AI Complementarity.” Journal of Learning Analytics 6 (2): 27–52. [CrossRef]

- (Hopcan, Türkmen, and Polat 2024) Hopcan, S., G. Türkmen, and E. Polat. 2024. “Exploring the Artificial Intelligence Anxiety and Machine Learning Attitudes of Teacher Candidates.” Education and Information Technologies 29: 7281–7301. [CrossRef]

- (Huang, Lu, and Yang 2023) Huang, A. Y. Q., O. H. T. Lu, and S. J. H. Yang. 2023. “Effects of Artificial Intelligence–Enabled Personalized Recommendations on Learners’ Learning Engagement, Motivation, and Outcomes in a Flipped Classroom.” Computers & Education 194: 104684. [CrossRef]

- (Humble and Mozelius 2022) Humble, N., and P. Mozelius. 2022. “The Threat, Hype, and Promise of Artificial Intelligence in Education.” Discover Artificial Intelligence 2: 22. [CrossRef]

- (Hutchins 1995) Hutchins, E. 1995. Cognition in the Wild. MIT Press.

- (Kandel et al. 2012) Kandel, E. R., J. H. Schwartz, T. M. Jessell, S. A. Siegelbaum, and A. J. Hudspeth. 2012. Principle of Neural Science. McGraw-Hill.

- (Kim and Sankey 2023) Kim, M., and D. Sankey. 2023. The Science of Learning and Development in Education: A Research-Based Approach to Educational Practice. Cambridge University Press.

- (Koch 2004) Koch, K. 2004. The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach. W. H. Freeman.

- (Laird, Lebiere, and Rosenbloom 2017) Laird, J. E., C. Lebiere, and P. S. Rosenbloom. 2017. “A Standard Model of the Mind: Toward a Common Computational Framework Across Artificial Intelligence, Cognitive Science, Neuroscience, and Robotics.” AI Magazine 38 (4): 13–26. [CrossRef]

- (Lake et al. 2017) Lake, B. M., T. D. Ullman, J. B. Tenenbaum, and S. J. Gershman. 2017. “Building Machines That Learn and Think Like People.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 40: e253. [CrossRef]

- (LeCun, Bengio, and Hinton 2015) LeCun, Y., Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton. 2015. “Deep Learning.” Nature 521: 436–444. [CrossRef]

- (Luckin 2017) Luckin, R. 2017. “Towards Artificial Intelligence-Based Assessment Systems.” Nature Human Behaviour 1: 0028. [CrossRef]

- (Luckin 2018) Luckin, R. 2018. Machine Learning and Human Intelligence: The Future of Education for the 21st Century. UCL IOE Press.

- (Luczak, McNaughton, and Kubo 2022) Luczak, A., B. L. McNaughton, and Y. Kubo. 2022. “Neurons Learn by Predicting Future Activity.” Nature Machine Intelligence 4: 62–72. [CrossRef]

- (McCulloch and Pitts 1943) McCulloch, W. S., and W. Pitts. 1943. “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity.” The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 5: 115–133. [CrossRef]

- (Papert 1993) Papert, S. A. 1993. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. Basic Books.

- (Piaget 1977) Piaget, J. 1977. The Development of Thought: Equilibration of Cognitive Structures. Viking Press.

- (Rizzolatti and Craighero 2004) Rizzolatti, G., and L. Craighero. 2004. “The Mirror-Neuron System.” Annal Review of Neuroscience 27: 169–192. [CrossRef]

- (Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams 1986) Rumelhart, D. E., G. E. Hinton, and R. J. Williams. 1986. “Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors.” Nature 323: 533–536. [CrossRef]

- (Russell and Norvig 2021) Russell, S., and P. Norvig. 2021. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. Pearson.

- (Samek, Wiegand, and Müller 2017) Samek, W., T. Wiegand, and K.-R. Müller. 2017. “Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Understanding, Visualizing and Interpreting Deep Learning Models.” arXiv. [CrossRef]

- (Schneider and Morris 1987) Schneider, S. M., and E. K. Morris. 1987. “A History of the Term Radical Behaviorism: From Watson to Skinner.” The Behavior Analyst 10 (1): 27–39. [CrossRef]

- (Schrimpf et al. 2021) Schrimpf, M., I. A. Blank, G. Tuckute, C. Kauf, E. A. Hosseini, N. Kanwisher, J. B. Tenenbaum, and E. Fedorenko. 2021. “The Neural Architecture of Language: Integrative Modeling Converges on Predictive Processing.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (45): e2105646118. [CrossRef]

- (Schütt, Kim, and Ma 2024) Schütt, H. H., D. Kim, and W. J. Ma. 2024. “Reward Prediction Error Neurons Implement an Efficient Code for Reward.” Nature Neuroscience 27: 1333–1339. [CrossRef]

- (Selwyn 2019) Selwyn, N. 2019. Should Robots Replace Teachers? AI and the Future of Education. Polity.

- (Siemens 2005) Siemens, G. 2005. “Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age.” International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 2 (1): 3–10.

- (Srivastava et al. 2014) Srivastava, N., G. Hinton, A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and R. Salakhutdinov. 2014. “Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 15 (1): 1929–1958.

- (Sutton and Barto 2018) Sutton, R. S., and A. G. Barto. 2018. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. Bradford Books.

- (Taran et al. 2023) Taran, S., P. Gros, T. Gofton, G. Boyd, J. N. Briard, M. Chassé, and J. M. Singh. 2023. “The Reticular Activating System: A Narrative Review of Discovery, Evolving Understanding, and Relevance to Current Formulations of Brain Death.” Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 70 (4): 788–795. [CrossRef]

- (Tononi 2004) Tononi, G. 2004. “An Information Integration Theory of Consciousness.” BMC Neuroscience 5: 42. [CrossRef]

- (Tononi 2008) Tononi, G. 2008. “Consciousness as Integrated Information: A Provisional Manifesto.” The Biological Bulletin 215 (3): 216–242. [CrossRef]

- (Turing 1950) Turing, A. M. 1950. “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” Mind 59: 433–460. [CrossRef]

- (van Gerven et al. 2009) van Gerven, M., A. Bahramisharif, T. Heskes, and O. Jensen. 2009. “Selecting Features for BCI Control Based on a Covert Spatial Attention Paradigm.” Neural Networks 22 (9): 1271–1277. [CrossRef]

- (Vygotsky 1978) Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

- (Vygotsky 1986) Vygotsky, L. S. 1986. Thought and Language. MIT Press.

- (Williamson and Eynon 2020) Williamson, B., and R. Eynon. 2020. “Historical Threads, Missing Links, and Future Directions in AI in Education.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (3): 223–235. [CrossRef]

- (Zou et al. 2020) Zou, B., S. Liviero, M. Hao, and C. Wei. 2020. “Artificial Intelligence Technology for EAP Speaking Skills: Student Perceptions of Opportunities and Challenges.” In New Language Learning and Teaching Environments, edited by M. R. Freiermuth and N. Zarrinabadi, 433–463. Springer. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).