Submitted:

21 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Related Studies

1.3. Contribution

- From images experimentally obtained from the integrated camera on the unmanned underwater vehicle, damages on the underwater pipeline were successfully detected using deep learning algorithms.

- The navigation and autopilot of the unmanned underwater vehicle were experimentally performed.

- Autonomous features were added to the remotely operated unmanned underwater vehicle: A series of preliminary tests were conducted to enable the unmanned underwater vehicle to track the underwater pipeline autonomously, independent of remote control. These tests resulted in configuring the necessary input information for the vehicle’s right, left, and vertical thrusters, deriving the relationship between pulse width modulation and linear-angular movements, and setting up the input data required for the vehicle to follow the desired path.

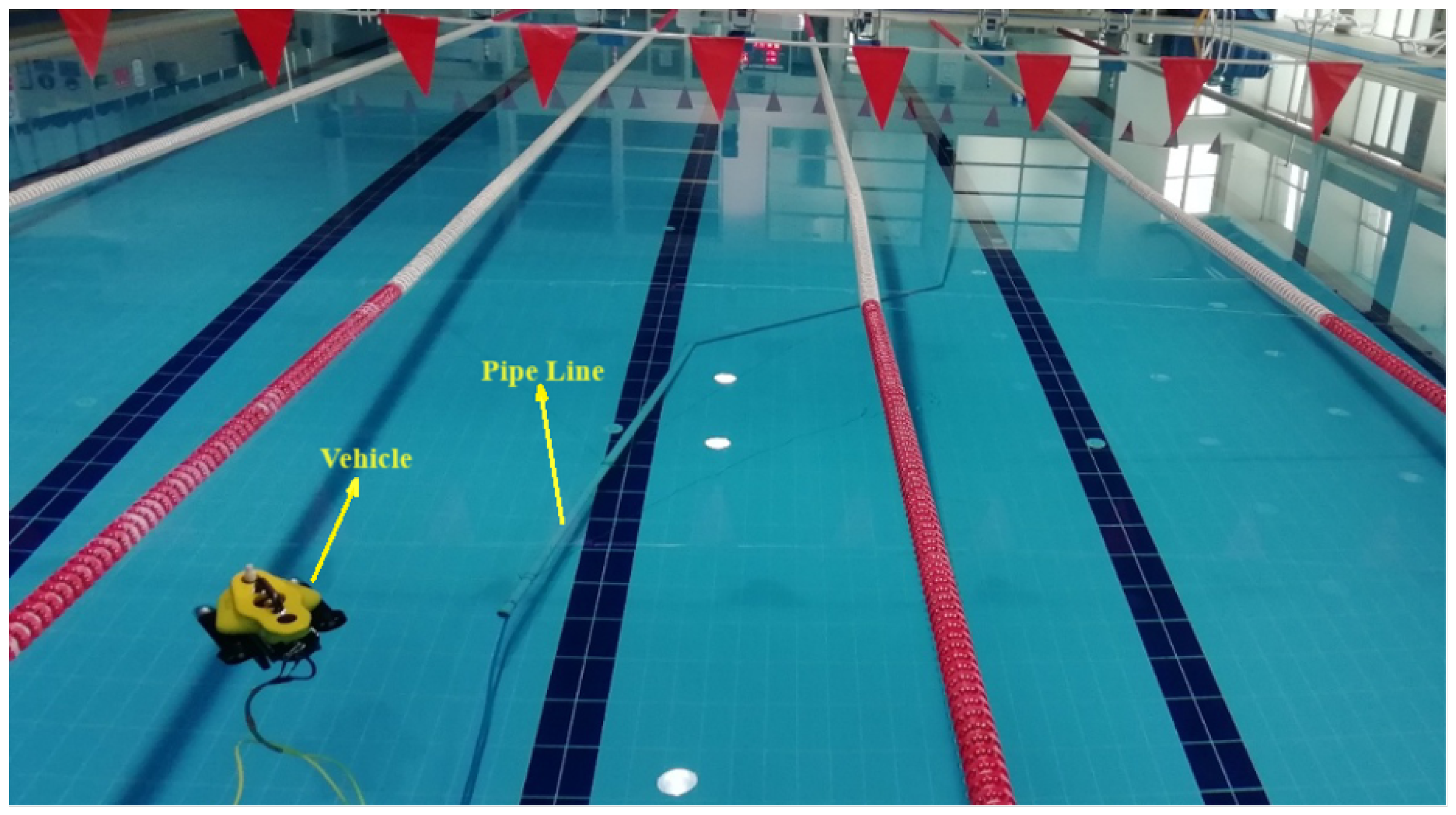

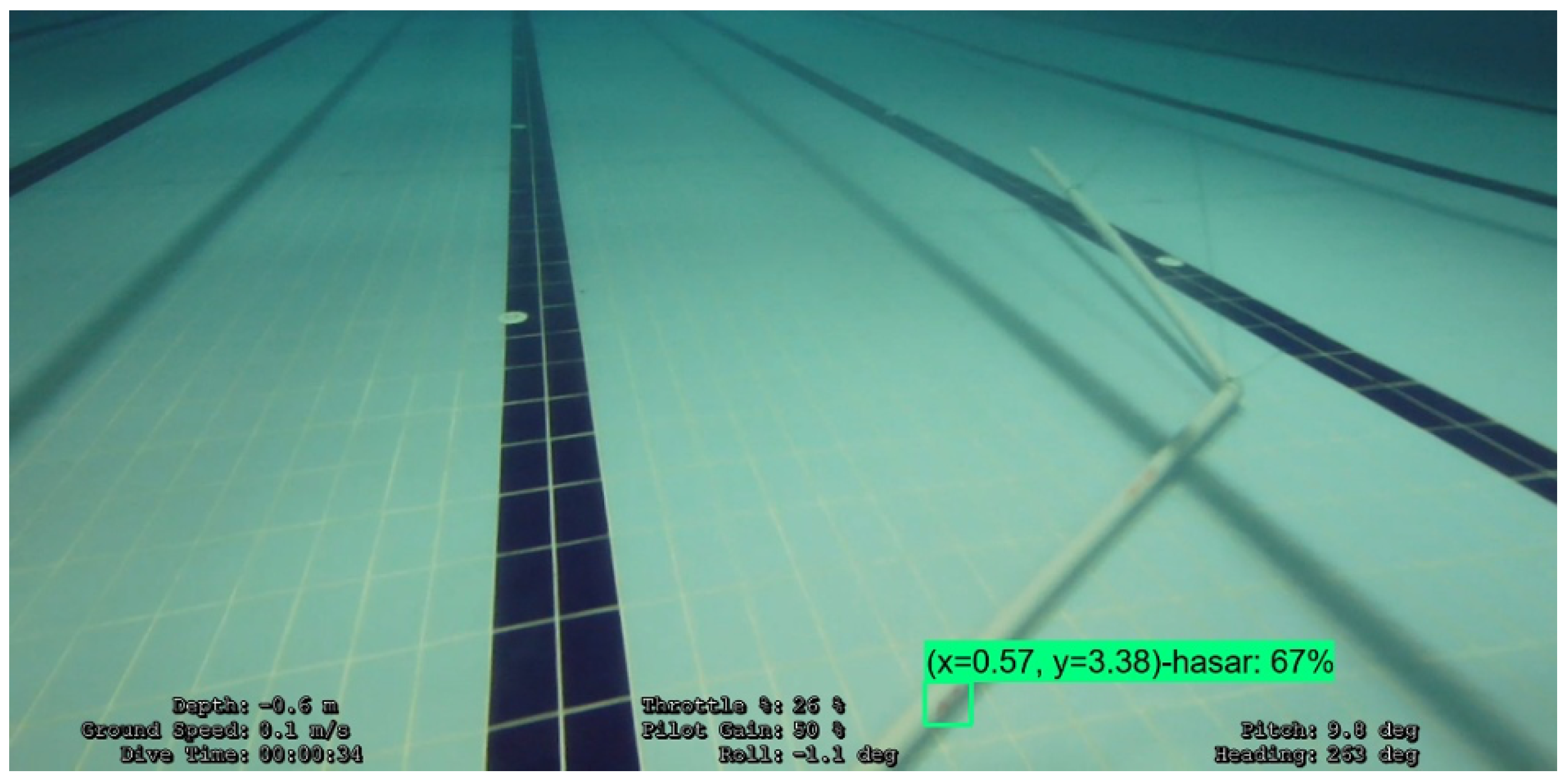

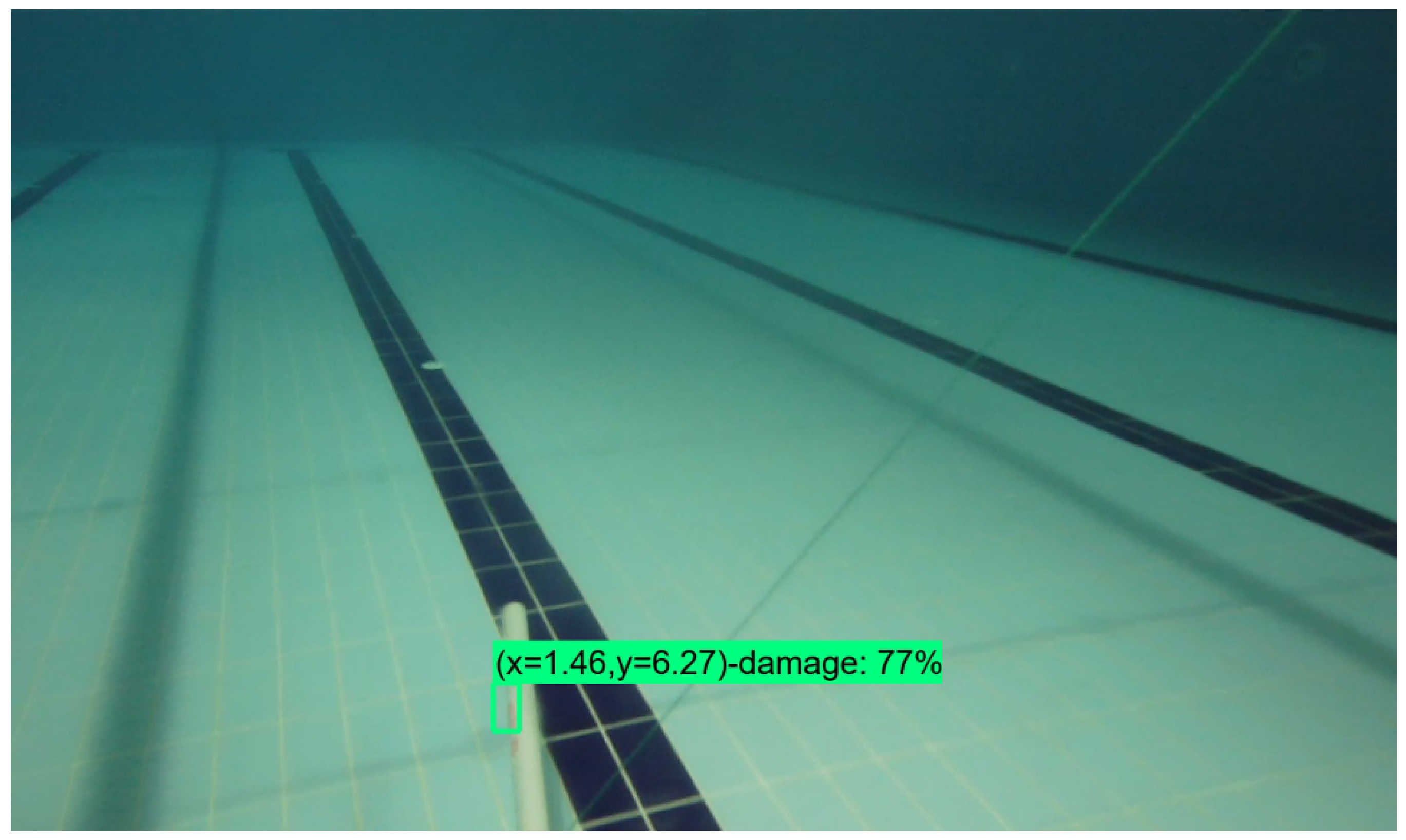

- The experiment of tracking the underwater pipeline with the unmanned underwater vehicle was autonomously and successfully conducted.

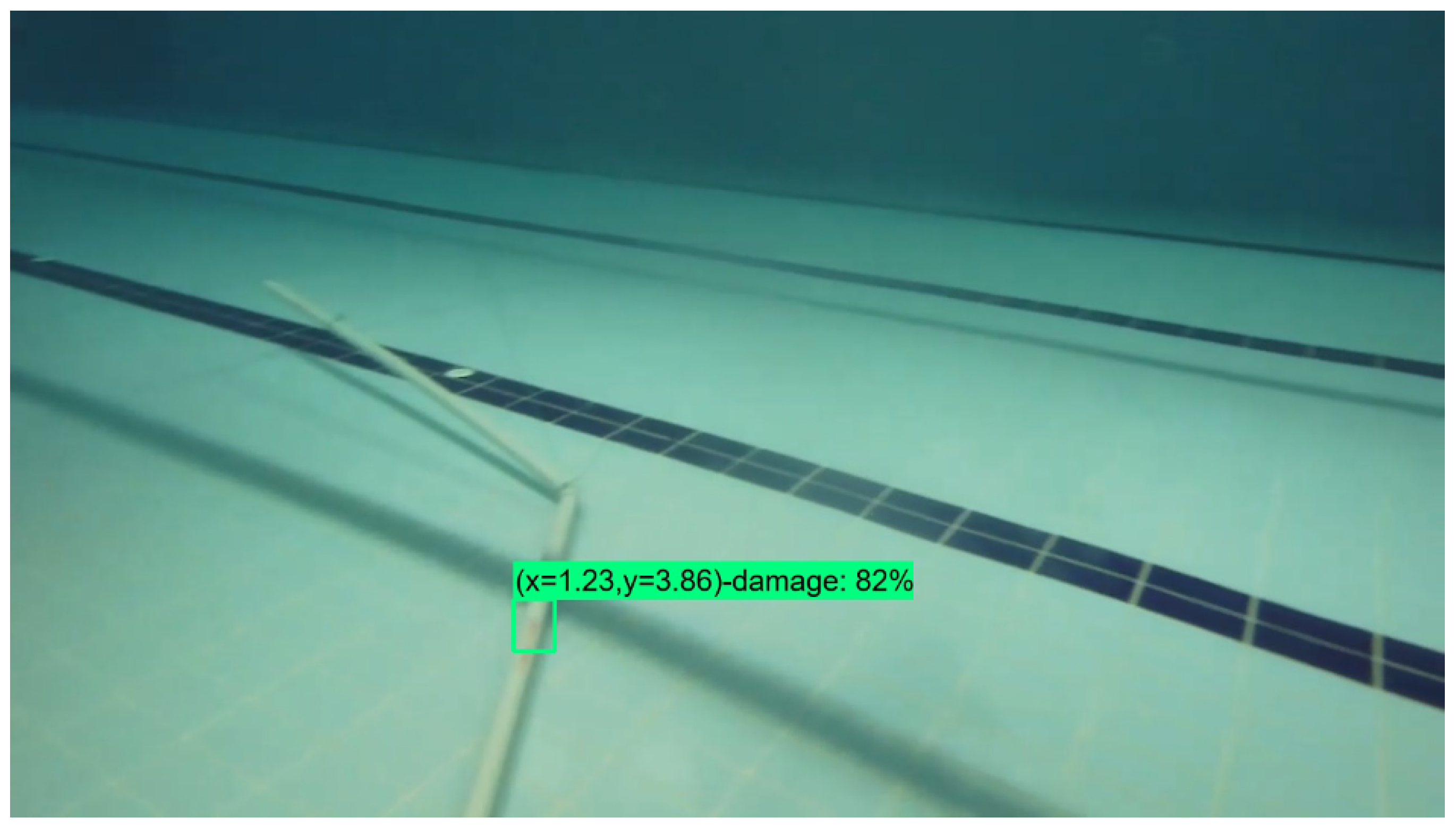

- In the underwater pipeline tracking experiment, the locations of the damages on the pipe were detected.

1.4. Organization

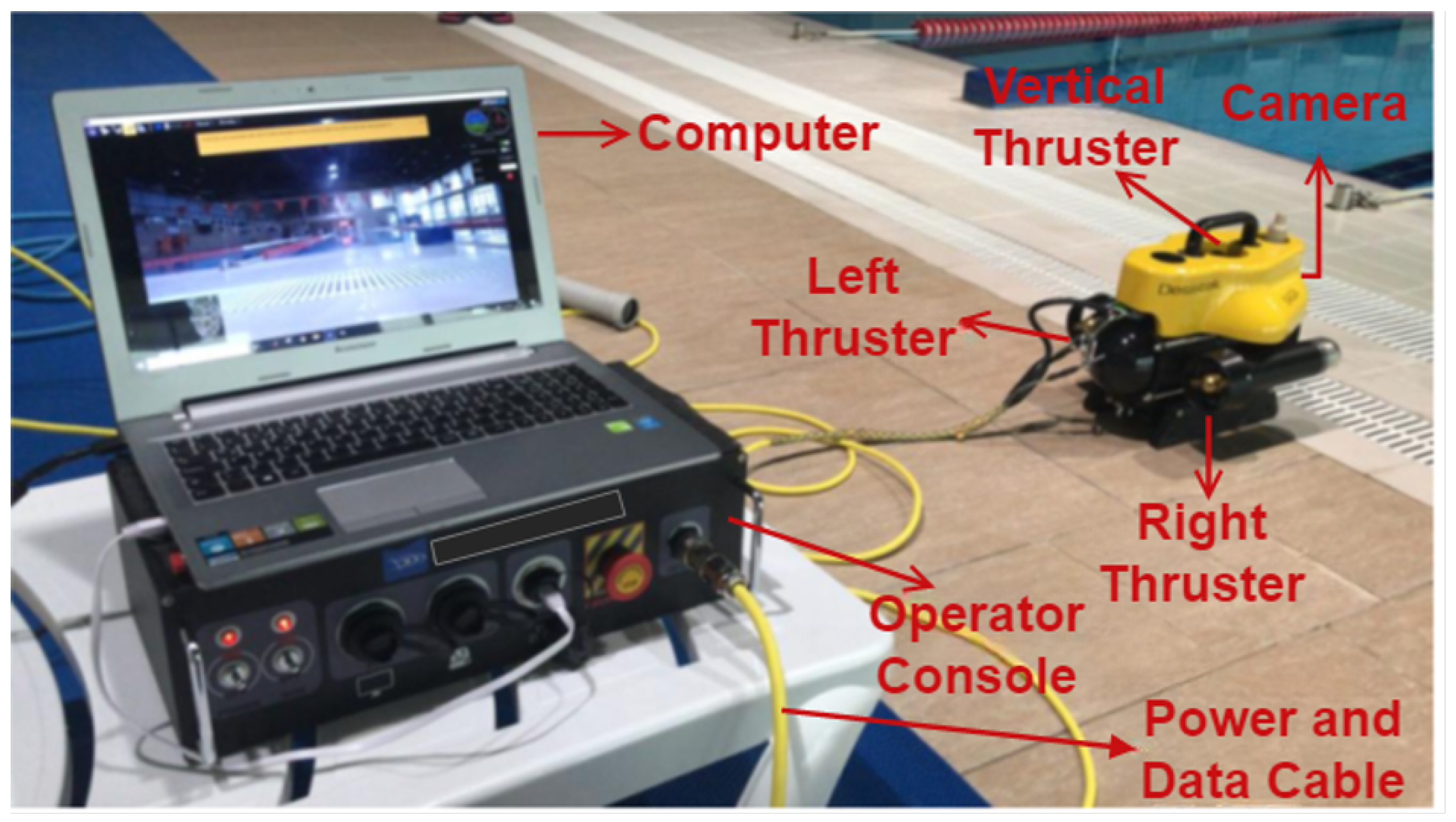

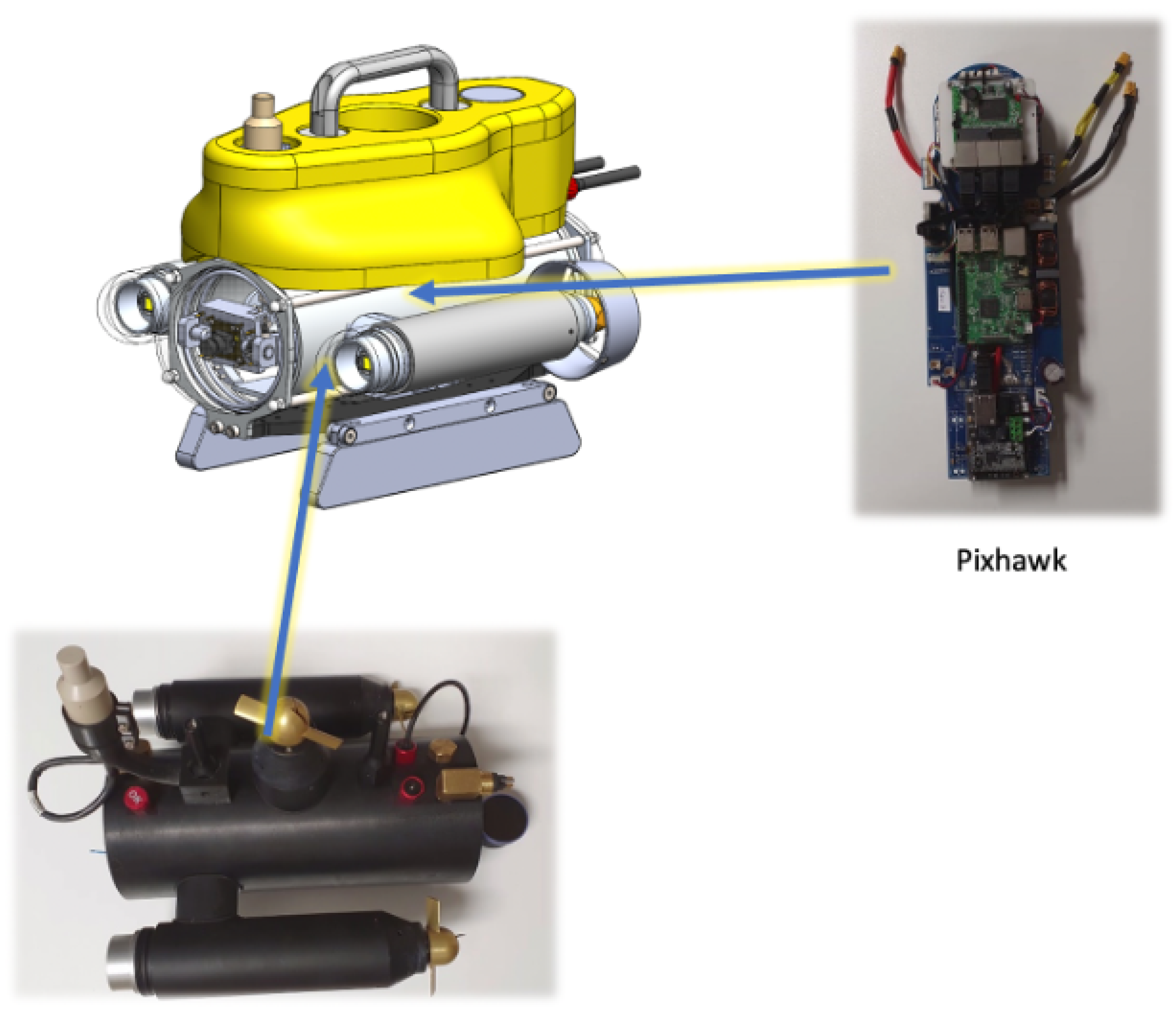

2. Unmanned Underwater Vehicle

3. Underwater Pipe Damage Detection

3.1. Convolutional Neural Network

3.1.1. İnput Layer

3.1.2. Convolutional Layer

3.1.3. Rectified Linear Unit Layer

3.1.4. Pooling Layer

3.1.5. Fully Connected Layer

3.1.6. DropOut Layer

3.1.7. Classifier Layer

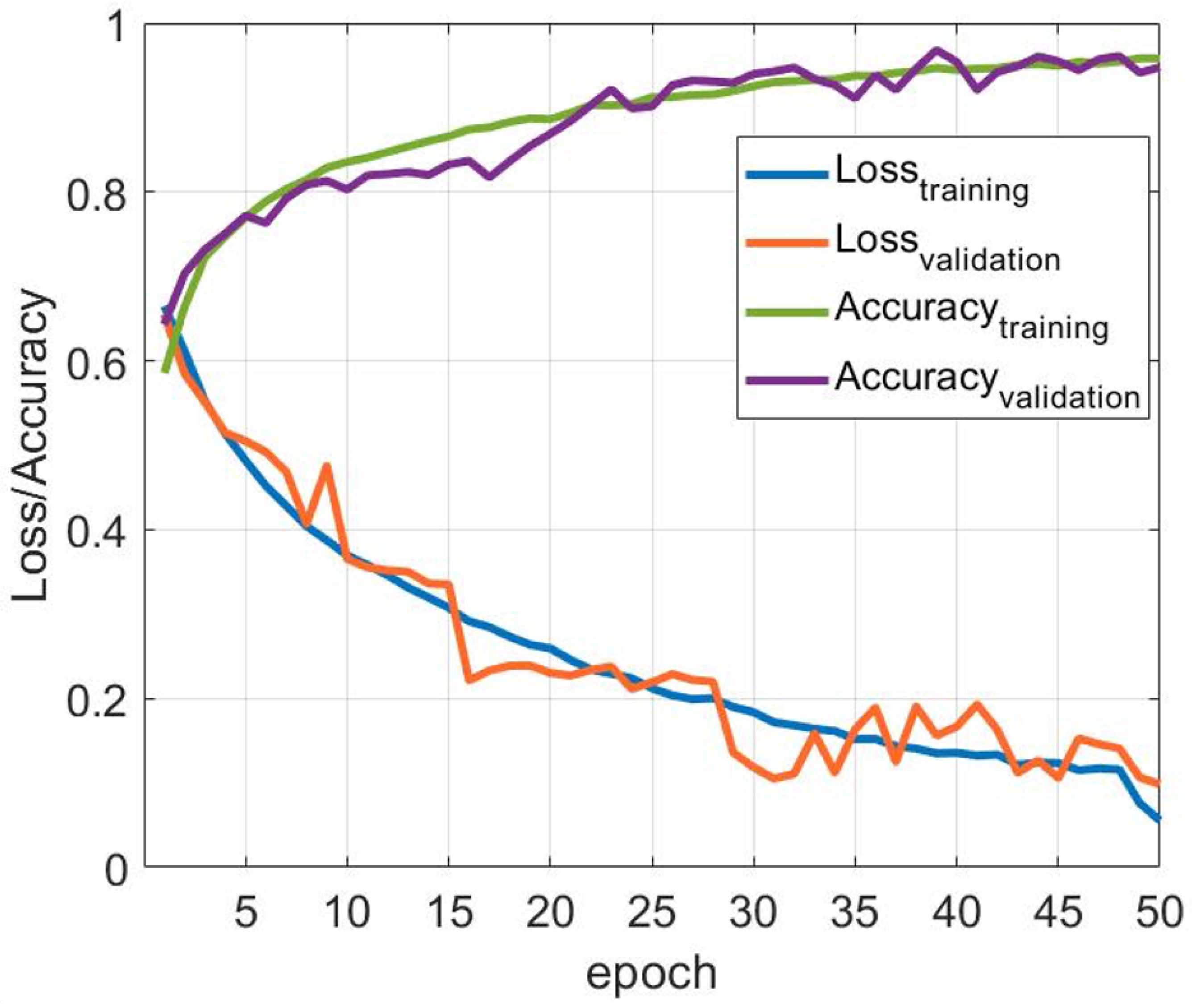

3.2. Convolutional Neural Network Training

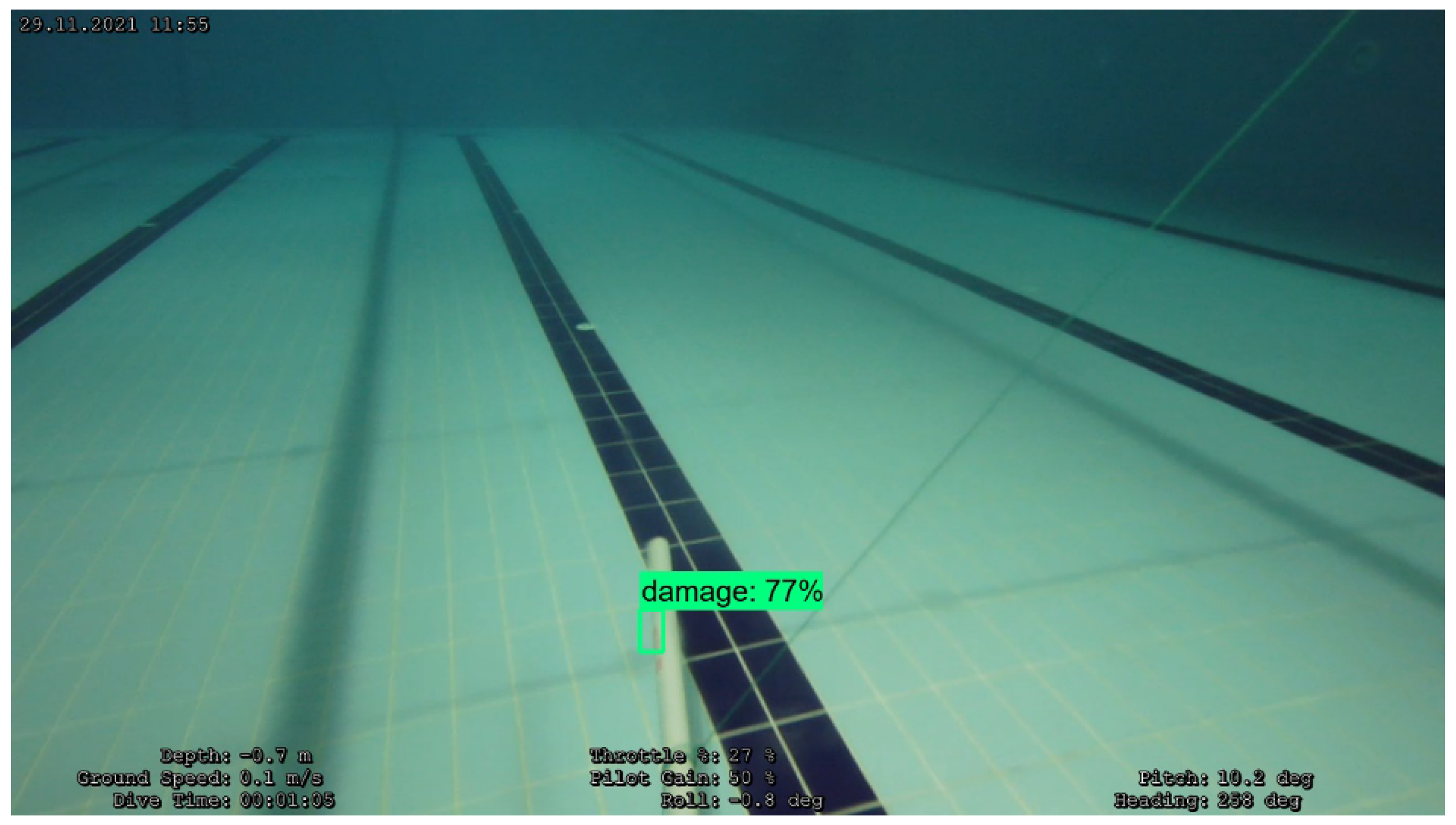

3.3. Underwater Damage Detection Experiment Results

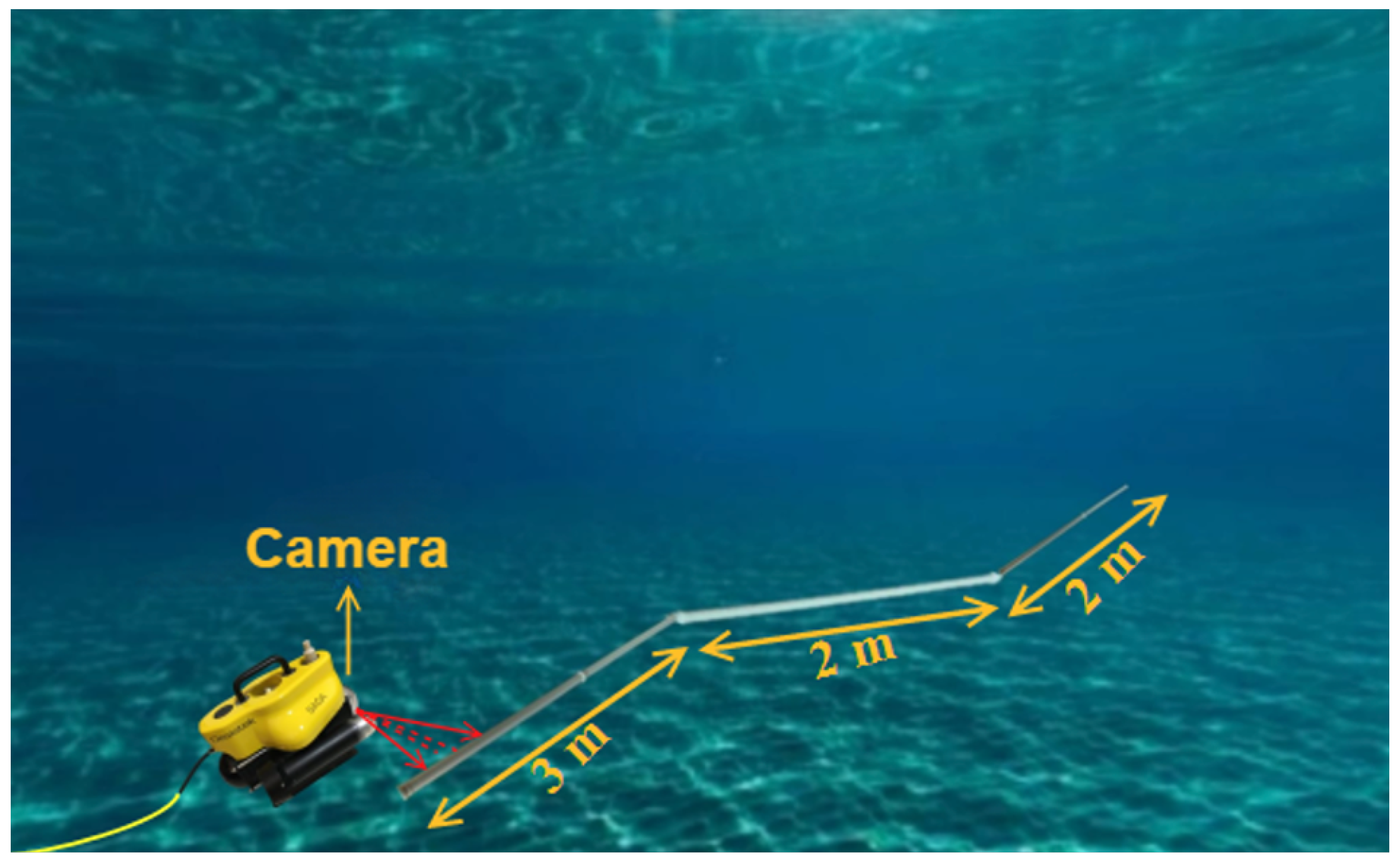

4. Underwater Autonomous Pipe Tracking and Damage Location Detection

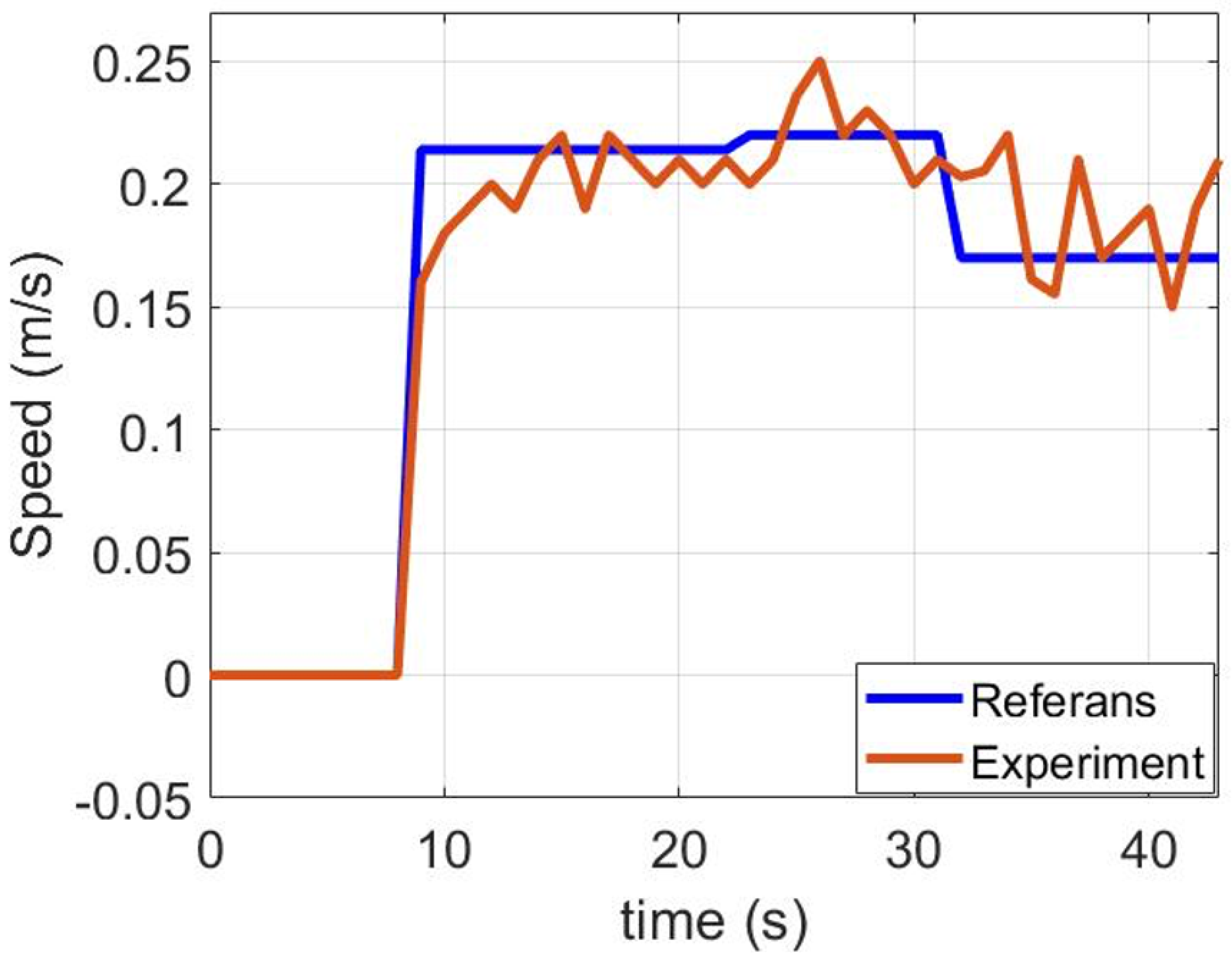

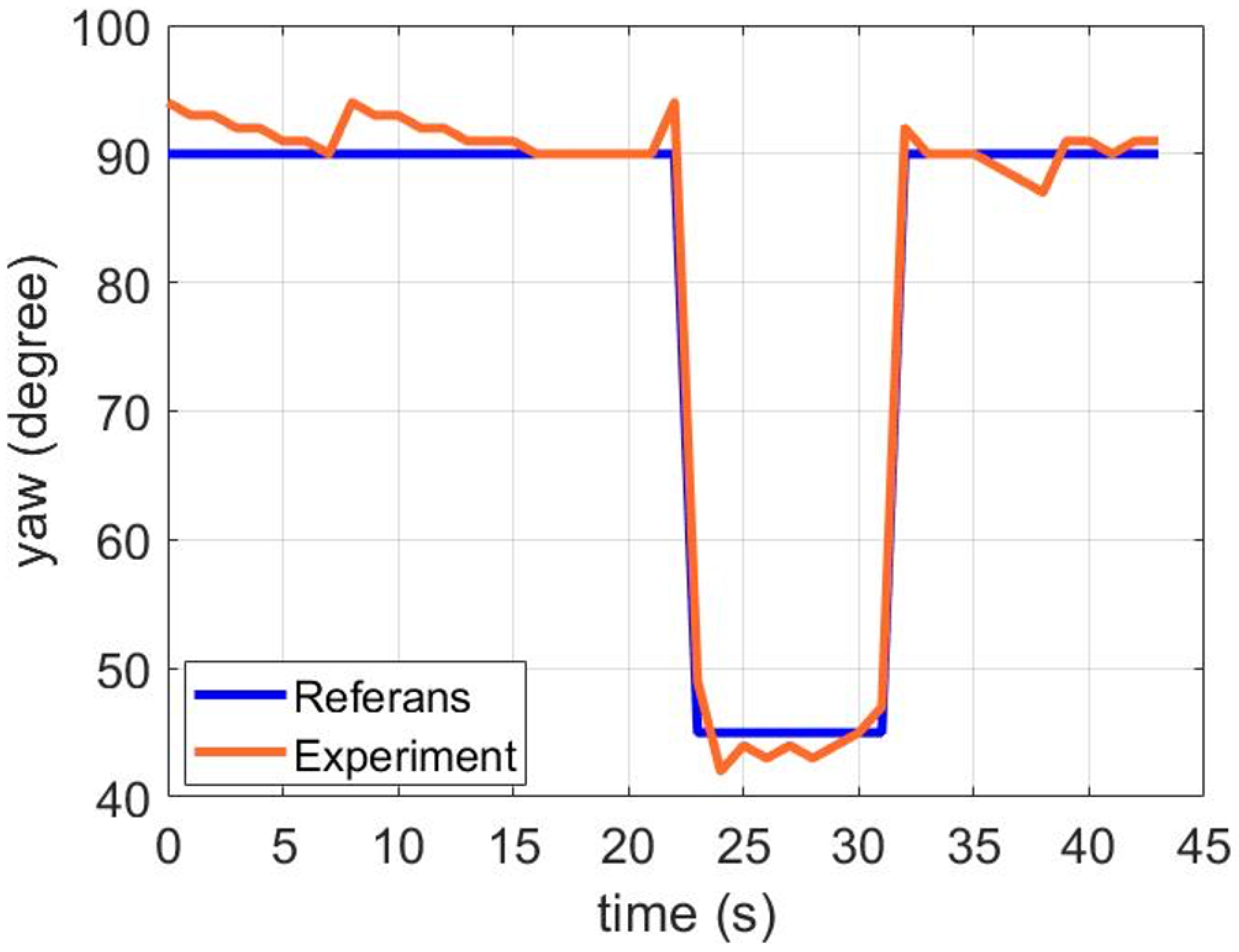

4.1. Navigation of Unmanned Underwater Vehicle

4.2. Autopilot of Unmanned Underwater Vehicle

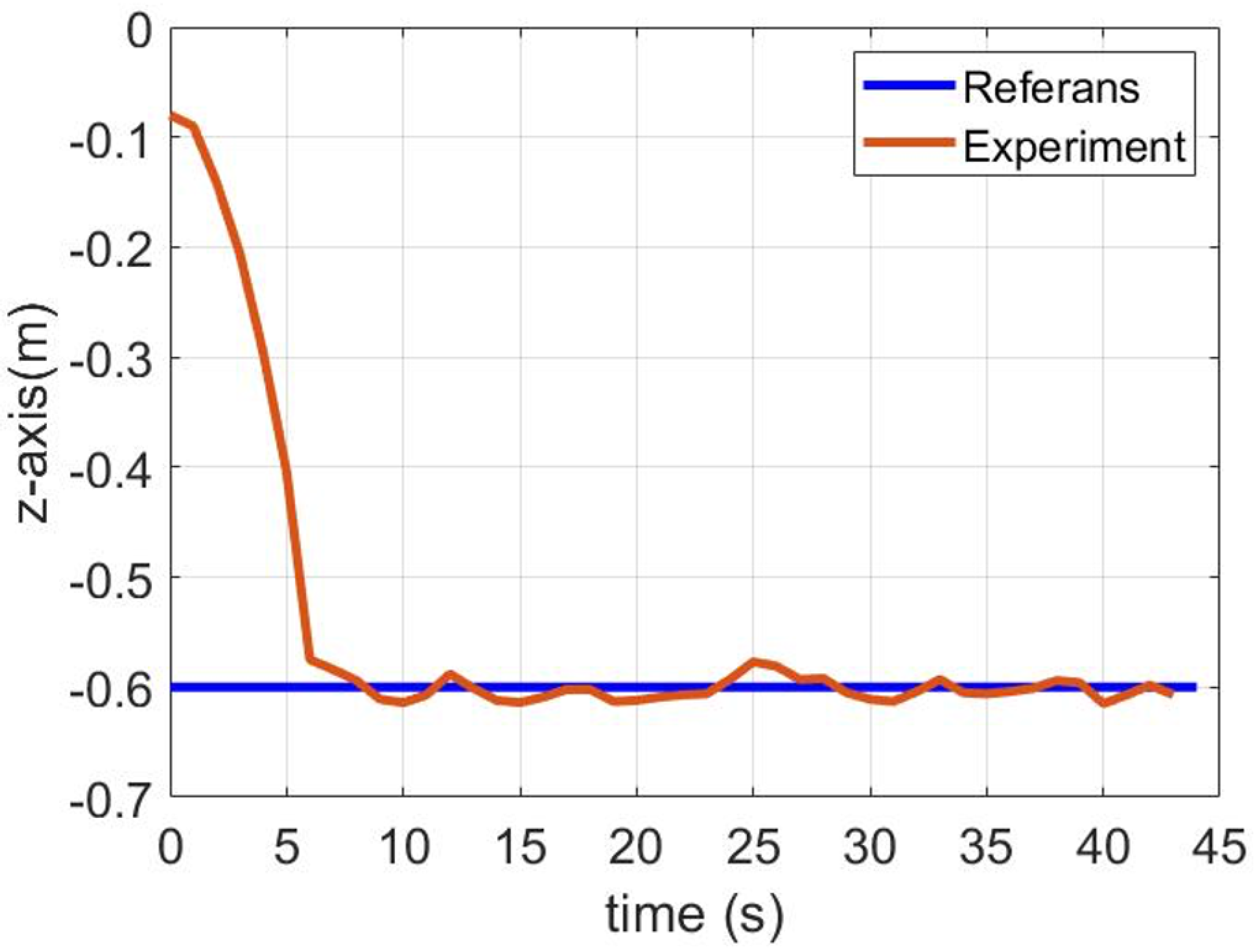

4.3. Pipe Line Damage Location Detection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wynn, Russell B. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): Their Past, Present and Future Contributions to the Advancement of Marine Geoscience. Marine Geology, 352, pp. 451-68, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dinc M., Chingiz H. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Journal of Marine Engineering & Technology, 14(1), pp. 32-43, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A. Redesigning the SLOCUM Glider for Torpedo Tube Launching. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 35(4), pp. 984-91 pp, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G.C. Gravitational Field Maps And Navigational Errors. Proceedings of the 2000 International Symposium on Underwater Technology, pp. 149-54 pp, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Fattah S. A., Abedin F. R3Diver: Remote Robotic Rescue Diver For Rapid Underwater Search And Rescue Operation. 2016 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), pp, 3280-83, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Park, J.-H., Hwang, J.-H., Noh, K., Choi, Y., Suh, J. Artificial Neural Network for Glider Detection in a Marine Environment by Improving a CNN Vision Encoder. J. Mar. Sci. Eng., v(12), pp.1106, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xia, T., Cui, D., Chu, Z., Yu, X. Autonomous Heading Planning and Control Method of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles for Tunnel Detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng., v(11), pp.740, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z., Wang, K., Zhang, J., Zhang, F. An Underwater Multisensor Fusion Simultaneous Localization and Mapping System Based on Image Enhancement. J. Mar. Sci. Eng., v(12), pp.1170, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Cheng, C., Cao, C., Guo, X., Pan, G., Zhang, F. An Invariant Filtering Method Based on Frame Transformed for Underwater INS/DVL/PS Navigation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng., v(12), pp.1178, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kaya Ustabaş G., Kocabaş S., Kartal S., Kaya H., Tekin I. Ö., Tığlı Aydin R.S., Kutoğlu Ş. H. Detection of airborne nanoparticles with lateral shearing digital holographic microscopy. Optics and Lasers in Engineering, v(151),pp.106934, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kartal, S.K., Hacıoğlu R., Görmüş S. K.,Kutoğlu, Ş.H., Leblebicioğlu, M.K. Modeling and Analysis of Sea-Surface Vehicle System for Underwater Mapping Using Single-Beam Echosounder. J. Mar. Sci. Eng., v(10), pp.1349, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Erol, B.; Cantekin, R.; Kartal, S.K.; Hacioglu, R.; Gormus, S.; Kutoglu, H.; Leblebicioglu, K. Estimation of Unmanned Underwater Vehicle Motion with Kalman Filter and Improvement by Machine Learning. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Pure Sci. 2021, 33, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Solomatine D. P., Shrestha D. L. A novel method to estimate model uncertainty using machine learning techniques. Water Resources Research, 45(12), pp. 1–16 pp, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Cortes C., Vapnik V. Support-Vector Networks Machine Learning. Springer, 20, pp. 273-297, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z., Ding S. MBSVR: Multiple birth support vector regressions. Information Sciences. 552, pp. 65-79, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Q., Qin X. A novel prediction method based on the support vector regression for the remaining useful life of lithium-ion batteries. Microelectronics Reliability, 85, pp. 99-108, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Li X., Shu X. An On-Board Remaining Useful Life Estimation Algorithm for Lithium-Ion Batteries of Electric Vehicles. Energies, 10(5), pp. 691, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Oktanisa I., Mahmudy W. F. Inflation Rate Prediction in Indonesia using Optimized Support Vector Regression Model. Journal of Information Technology and Computer Science, 5(1): pp. 104-114, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Manasa J., Grupta R. Machine Learning based Predicting House Prices using Regression Techniques. 2nd International Conference on Innovative Mechanisms for Industry Applications, (ICIMIA), pp. 624-630, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Smola A. J., Schölkopf B. A Tutorial On Support Vector Regression. Statistics and Computing, 14(3): pp. 199-222, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y., Zhang Z. A Hybrid Seasonal Mechanism With A Chaotic Cuckoo Search Algorithm With A Support Vector Regression Model For Electric Load Forecasting. Energies, MDPI, 11(4): pp. 1-21, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Li M. W., Geng J. Periodogram Estimation Based On LSSVR-CCPSO Compensation For Forecasting Ship Motion. Nonlinear Dynamics, 97 (4): pp. 2579-2594, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cheng K., Lu Z. Active Learning Bayesian Support Vector Regression Model For Global Approximation. Information Sciences, 544: pp. 549-563 pp, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z., Ding S. A Support Vector Regression Model Hybridized With Chaotic Krill Herd Algorithm And Empirical Mode Decomposition For Regression Task. Neurocomputing. 410: pp. 185-201, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gu J., Wang Z. Recent Advances İn Convolutional Neural Networks. Pattern Recognition, 77: pp. 354-77, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gu J., Wang Z. Recent Advances İn Convolutional Neural Networks. Pattern Recognition, 77: pp. 354-77, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Niu X., Ching Y. S. A Novel Hybrid CNN-SVM Classifier For Recognizing Handwritten Digits | Pattern Recognition. Pattern Recognition, 45(4): pp. 131825, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky O., Deng J. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. International Journal of Computer Vision, 115(3): pp. 211-52, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan K., Andrew Z. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv:1409.1556 [cs]. pp. 1-14, 2015.

- Szegedy C., Liu W. Going Deeper With Convolutions. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp.1-9, 2015.

- He X., Wei Z. Emotion Recognition By Assisted Learning With Convolutional Neural Networks. Neurocomputing, 291: pp.187-94, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pertusa A., Gallego A. MirBot: A Collaborative Object Recognition System for Smartphones Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Neurocomputing, 293: pp.87-99, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Li X., Min S. Fast Accurate Fish Detection And Recognition Of Underwater İmages With Fast R-CNN. OCEANS MTS/IEEE Washington, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Chavez A. G., Birk A. Stereo-Vision Based Diver Pose Estimation Using LSTM Recurrent Neural Networks For AUV Navigation Guidance. OCEANS-Aberdeen, pp.1-7 pp, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Buß, M., Steiniger, Y. Hand-Crafted Feature Based Classification against Convolutional Neural Networks for False Alarm Reduction on Active Diver Detection Sonar Data. OCEANS MTS/IEEE Charleston, pp.1-7, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Williams D. P. Demystifying Deep Convolutional Neural Networks For Sonar Image Classification. NATO STO Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation (CMRE) Viale San Bartolomeo, 400: pp.513-520, 2019.

- Williams D. P. On the Use of Tiny Convolutional Neural Networks for Human-Expert-Level Classification Performance in Sonar Imagery. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, 46(1), pp.236-260, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Li M., Ji H. Underwater Object Detection And Tracking Based On Multi-Beam Sonar İmage Processing. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), pp.1071-76, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mandic F., Ivor R. Underwater Object Tracking Using Sonar and USBL Measurements. Journal of Sensors, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Xiang X., Caoyang Y. Autonomous Underwater Vehicle with Magnetic Sensing Guidance. Sensors, MDPI, 16(8): pp.1335, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bigoni C., Hesthaven J. Simulation-Based Anomaly Detection and Damage Localization: An Application to Structural Health Monitoring. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 363: pp.112896, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Katija K., Roberts P. Visual Tracking Of Deepwater Animals Using Machine Learning-Controlled Robotic Underwater Vehicles. IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), pp.859-68, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Packard G. E., Kukulya A. Continuous Autonomous Tracking And İmaging Of White Sharks And Basking Sharks Using a REMUS-100 AUV. OCEANS, pp.1-5 pp, 2013.

- Kezebou L., Oludare V. Underwater Object Tracking Benchmark and Dataset. IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), pp.1-6 pp, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fossen T. I., Guidance and Control of Ocean Vehicles, Wiley, 1999.

- The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory. Springer, New York, 2000.

- Kartal S., Leblebicioğlu M. K. Experimental Test of the Acoustic-Based Navigation and System Detection of an Unmanned Underwater Survey Vehicle (SAGA). Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control, 40(8): pp.247-687, 2018.

- Kartal S., Leblebicioğlu M. K. Experimental test of vision-based navigation and system identification of an unmanned underwater survey vehicle (SAGA) for the yaw motion. Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control, 41(8):2160-2170, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Perlin H. A., Heitor S. L. Extracting Human Attributes Using a Convolutional Neural Network Approach. Pattern Recognition Letters, 68: pp.250-59, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Lecun Y., Bottou L. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE, 86(11), pp.2278-2324, 1998.

- Wang G., Zhang L. Longitudinal Tear Detection of Conveyor Belt under Uneven Light Based on Haar-AdaBoost and Cascade Algorithm. IEEE Access, pp.108-341, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zeiler M. D., Rob F. Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks. Computer Vision, Springer International Publishing, pp.818-33, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lecun Y., Yoshua B. Deep Learning. Nature, 521(7553): pp.436-44, 2015. [CrossRef]

- He K., Xiangyu Z. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. Computer Vision, Springer International Publishing, v(37), pp.346-61, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Nair V., Geoffrey E. H. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML10, Omnipress, v(27), pp.807-814, 2010.

- Albawi S., Tareq A. M. Understanding of a Convolutional Neural Network. In 2017 International Conference on Engineering and Technology (ICET), pp.16-21, 2017.

- Albawi S., Tareq A. M. Artificial Convolution Neural Network for Medical Image Pattern Recognition. Neural Networks, 8(7): pp.1201-14, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Pal M., Giles M. F. Feature Selection for Classification of Hyperspectral Data by SVM. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 48(5): pp.2297-2307, 2010.

- DE O., Diulhio C. Using Deep Learning and Low-Cost RGB and Thermal Cameras to Detect Pedestrians in Aerial Images Captured by Multirotor UAV. Sensors, 18(7): pp.2244, sensors, MDPI, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Caccia M., Bibuli R. Basic Navigation, Guidance And Control Of An Unmanned Surface Vehicle. Auton. Robots, v(25), pp.349-365, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P., Supraja B. et al. Real-Time Concrete Damage Detection Using Deep Learning for High Rise Structures. IEEE Access, 9: pp.112312-31, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Edge C., Enan S. et al. Design and Experiments with LoCO AUV. IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS 2020, pp.1761-68, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Manzanlilla A., Sanchez S. et al. Autonomous Navigation for Unmanned Underwater Vehicles: Real-Time Experiments Using Computer Vision. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 4(2): pp, 1351-56, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yu Z., Zhang Y. et al. Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Time-Varying Formation Control of Unmanned Airships With Limited Communication Ranges Against Input Saturation for Smart City Observation. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 33(5): pp.1891-1904, 2022. [CrossRef]

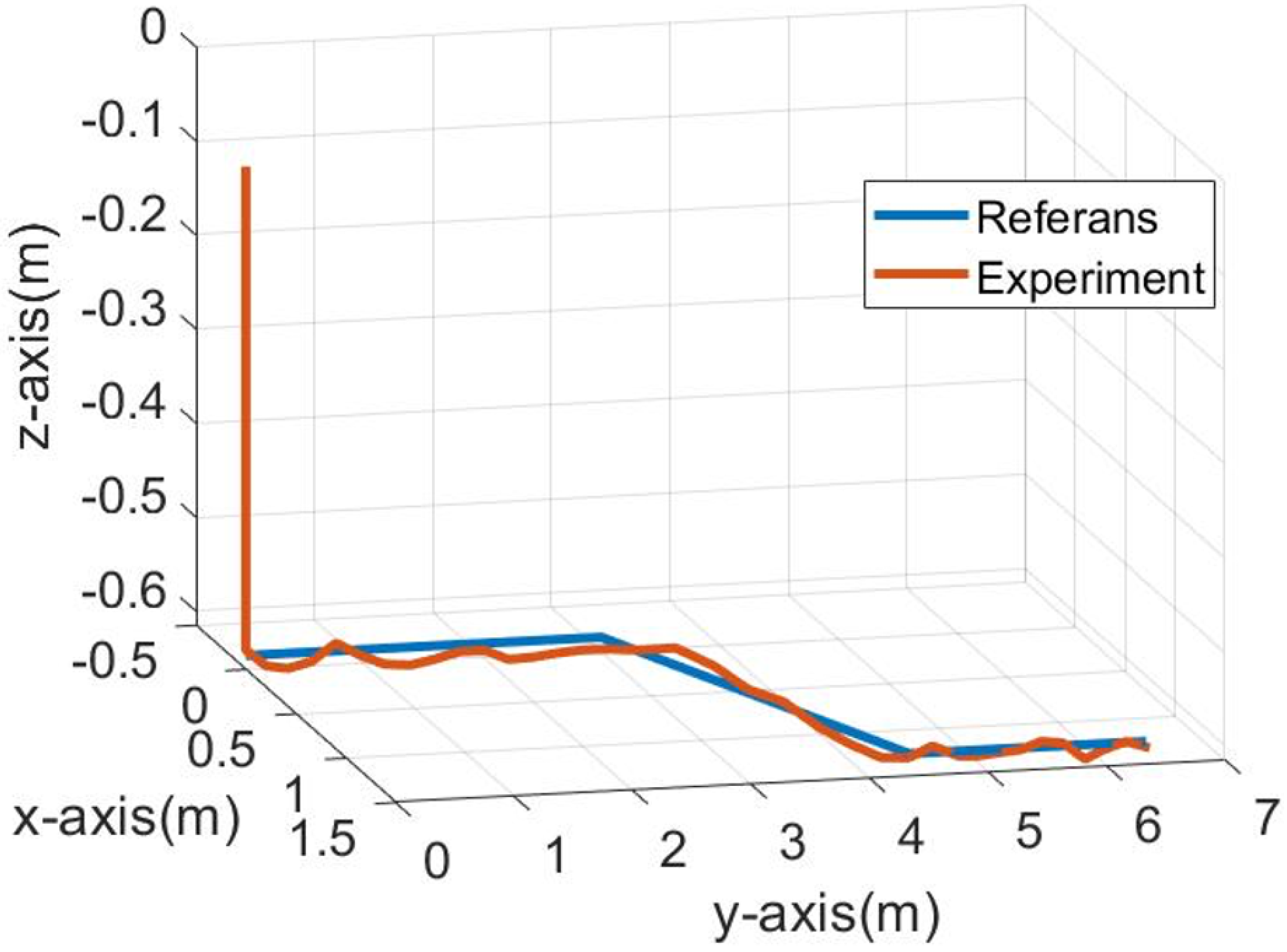

| Position | RMSE |

|---|---|

| x | 0.072 m |

| y | 0.037 m |

| z | 0.161 m |

| yaw | 1.9 deg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).