Submitted:

21 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

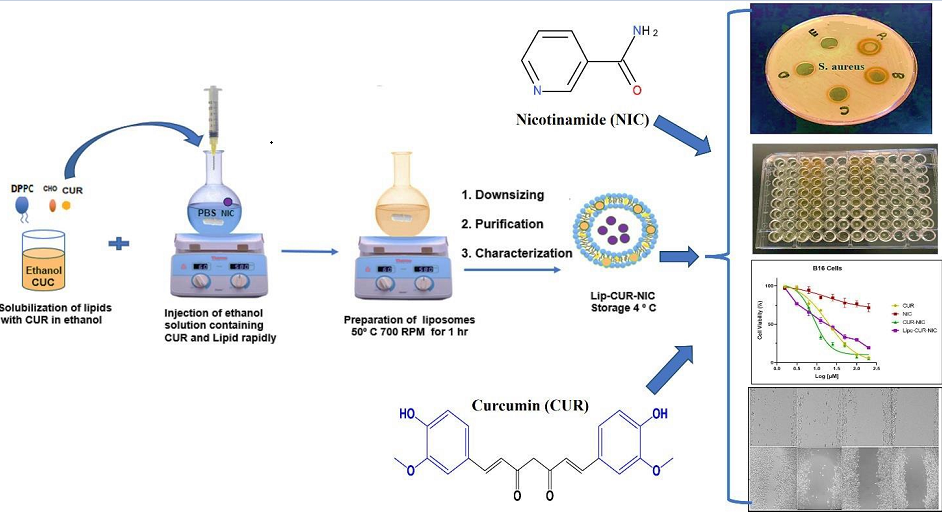

2.1. Liposomal Preparation

2.2. Screening of the Antibacterial Activity

2.2.1. Agar Well-Diffusion Method

2.2.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.2.3. S. aureus Susceptibility

2.3. Cell Culture

2.3.1. Cell Viability Assay (MTT)

2.3.2. Cell Migration Assay

2.4. DPPH Assay

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

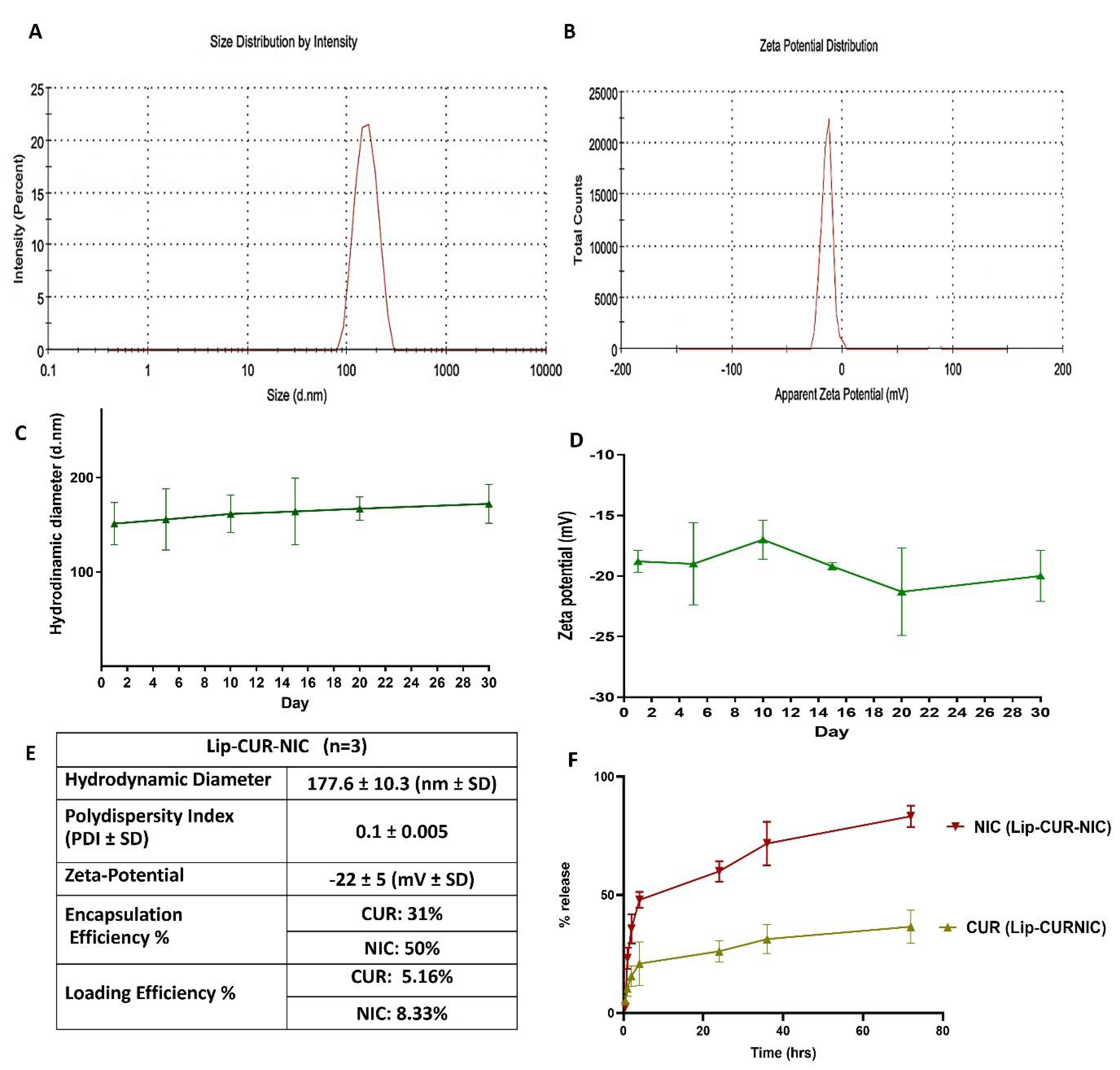

3.1. Liposomal Preparation and Characterization

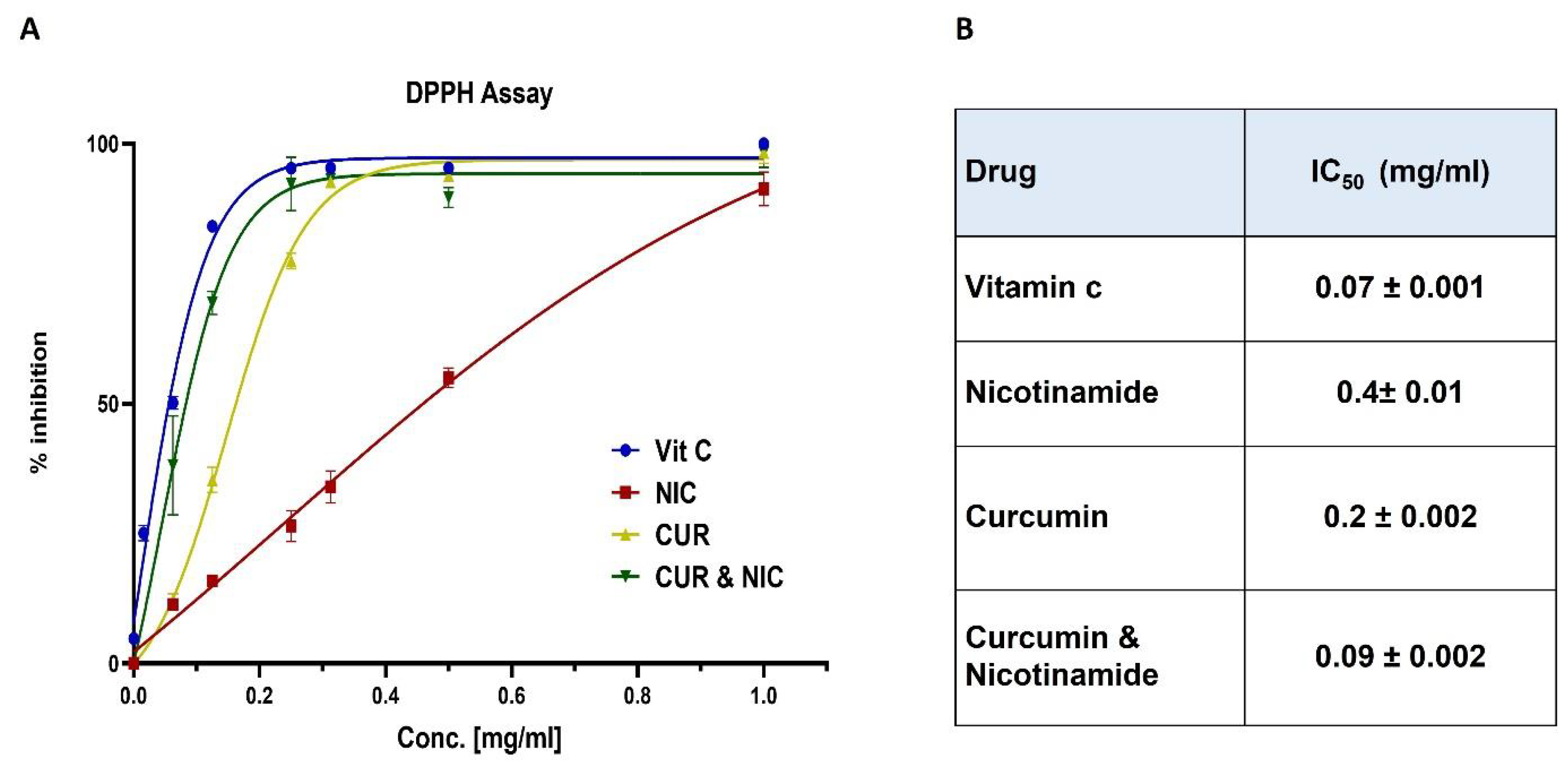

3.2. Antioxidant Activity and DPPH Assay

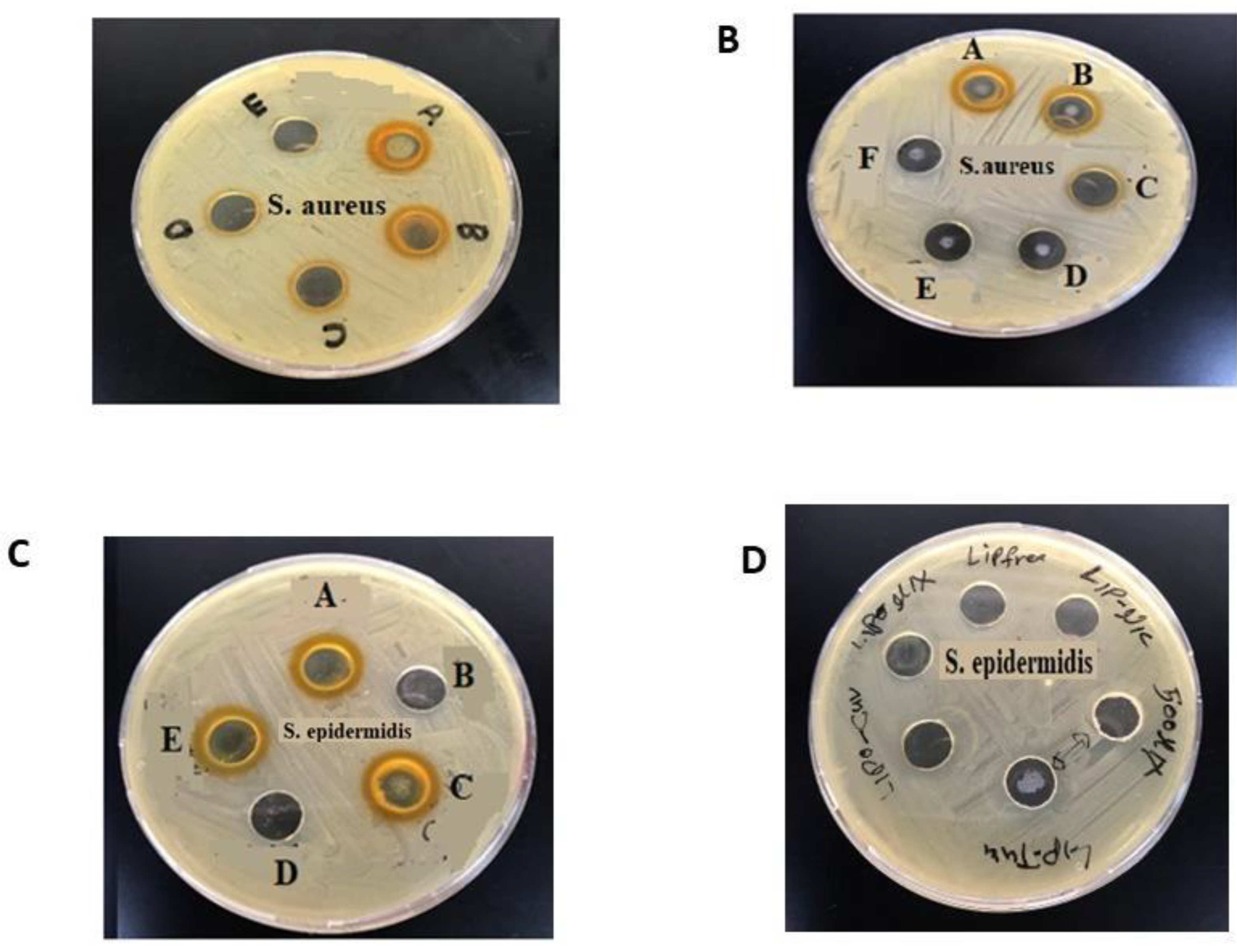

3.3. Antibacterial Activity of CUR, NIC and lip- CUR-NC

3.4. Cytotoxicity study and Anticancer Activity

3.5. Migration Test (Scratch Assay)

4. Conclusion

References

- Sorrenti, V.; Burò, I.; Consoli, V.; Vanella, L. Recent Advances in Health Benefits of Bioactive Compounds from Food Wastes and By-Products: Biochemical Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsairat, H.; Lafi, Z.; Al-Sulaibi, M.; Gharaibeh, L.; Alshaer, W. Impact of nanotechnology on the oral delivery of phyto-bioactive compounds. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafi, Z.; et al. A review Echinomycin: A Journey of Challenges. Jordan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 16, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, H.M.; Imraish, A.; Al-Hussaini, M.; Zihlif, M.; Harb, A.A.; Abu Thiab, T.M.; Lafi, Z.; Nassar, Z.D.; Afifi, F.U. Ethanol Extract of Achillea fragrantissima Enhances Angiogenesis through Stimulation of VEGF Production. Endocrine, Metab. Immune Disord. - Drug Targets 2021, 21, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafi, Z.M.; Irshaid, Y.M.; El-Khateeb, M.; Ajlouni, K.M.; Hyassat, D. Association of rs7041 and rs4588 Polymorphisms of the Vitamin D Binding Protein and the rs10741657 Polymorphism of CYP2R1 with Vitamin D Status Among Jordanian Patients. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 2015, 19, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, R.R.; Bonomo, R.A. Overview: Global and Local Impact of Antibiotic Resistance. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2016, 30, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Y.; Alam, W.; Ullah, H.; Dacrema, M.; Daglia, M.; Khan, H.; Arciola, C.R. Antimicrobial Potential of Curcumin: Therapeutic Potential and Challenges to Clinical Applications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwobodo, D.C.; Ugwu, M.C.; Anie, C.O.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Ikem, J.C.; Chigozie, U.V.; Saki, M. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.; et al. Curcumin: A new candidate for melanoma therapy? International journal of cancer 2016, 139, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laikova, K.V.; Oberemok, V.V.; Krasnodubets, A.M.; Gal’chinsky, N.V.; Useinov, R.Z.; Novikov, I.A.; Temirova, Z.Z.; Gorlov, M.V.; Shved, N.A.; Kumeiko, V.V.; et al. Advances in the Understanding of Skin Cancer: Ultraviolet Radiation, Mutations, and Antisense Oligonucleotides as Anticancer Drugs. Molecules 2019, 24, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainab, L.; Hiba, T.; Hanan, A. An updated assessment on anticancer activity of screened medicinal plants in Jordan: Mini review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafi, Z.; Aboalhaija, N.; Afifi, F. Ethnopharmacological importance of local flora in the traditional medicine of Jordan: (A mini review). Jordan J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 15, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hack, M.E.A.; de Oliveira, M.C.; Attia, Y.A.; Kamal, M.; Almohmadi, N.H.; Youssef, I.M.; Khalifa, N.E.; Moustafa, M.; Al-Shehri, M.; Taha, A.E. The efficacy of polyphenols as an antioxidant agent: An updated review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 250, 126525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munef, A.; Lafi, Z.; Shalan, N. Investigating anti-cancer activity of dual-loaded liposomes with thymoquinone and vitamin C. Ther. Deliv. 2024, 15, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, P. Oral Nicotinamide Prevents Common Skin Cancers in High-Risk Patients, Reduces Costs. . 2015, 8, 13–4. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.C.; Martin, A.J.; Snaidr, V.A.; Eggins, R.; Chong, A.H.; Fernandéz-Peñas, P.; Gin, D.; Sidhu, S.; Paddon, V.L.; Banney, L.A.; et al. Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention in Transplant Recipients. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surjana, D.; Halliday, G.M.; Damian, D.L. Role of Nicotinamide in DNA Damage, Mutagenesis, and DNA Repair. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salech, F.; et al. Nicotinamide, a poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP-1) inhibitor, as an adjunctive therapy for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2020, 12: p. 255.

- Lafi, Z.; et al. Aptamer-functionalized pH-sensitive liposomes for a selective delivery of echinomycin into cancer cells. RSC Advances 2021, 11, 29164–29177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaer, W.; Zraikat, M.; Amer, A.; Nsairat, H.; Lafi, Z.; Alqudah, D.A.; Al Qadi, E.; Alsheleh, T.; Odeh, F.; Alkaraki, A.; et al. Encapsulation of echinomycin in cyclodextrin inclusion complexes into liposomes: in vitro anti-proliferative and anti-invasive activity in glioblastoma. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 30976–30988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, M.P.; Lewis, J.S. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Background, Organization, Functions, and Processes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmig, R.; Babczyk, P.; Gillemot, P.; Schmitz, K.-P.; Schulze, M.; Tobiasch, E. Development and Evaluation of a Prototype Scratch Apparatus for Wound Assays Adjustable to Different Forces and Substrates. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajari, M.; Rostamizadeh, K.; Shapouri, R.; Taghavi, L. Eco-friendly curcumin-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier as an efficient antibacterial for hospital wastewater treatment. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 18, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavri, M.; Piddock, L.J.V.; Gibbons, S. Bacterial efflux pump inhibitors from natural sources. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 59, 1247–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teow, S.-Y.; Ali, S.A. Synergistic antibacterial activity of Curcumin with antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus. . 2015, 28, 2109–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mun, S.-H.; Joung, D.-K.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kang, O.-H.; Kim, S.-B.; Seo, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.-C.; Lee, D.-S.; Shin, D.-W.; Kweon, K.-T.; et al. Synergistic antibacterial effect of curcumin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Pan, C.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, W.; Yin, P.; Yu, X. Combination of Erythromycin and Curcumin Alleviates Staphylococcus aureus Induced Osteomyelitis in Rats. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wu, H.; Lv, F. Study on the antibiotic activity of microcapsule curcumin against foodborne pathogens. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 136, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, H.; et al. Antibacterial effects of curcumin: An in vitro minimum inhibitory concentration study. Toxicol Ind Health 2016, 32, 246–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shailendiran, D.; Pawar, N.; Chanchal, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Bohidar, H.B.; Verma, A.K. Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Nanocurcumin and Curcumin. 2011 International Conference on Nanoscience, Technology and Societal Implications (NSTSI). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–7.

- Hu, P.; Huang, P.; Chen, M.W. Curcumin reduces Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation by inhibiting sortase A activity. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izui, S.; Sekine, S.; Maeda, K.; Kuboniwa, M.; Takada, A.; Amano, A.; Nagata, H. Antibacterial Activity of Curcumin Against Periodontopathic Bacteria. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, X.; Teng, Y.; Yu, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhang, L.; Shen, Y. Improving anti-melanoma effect of curcumin by biodegradable nanoparticles. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 108624–108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes, S.S.; Nogueira, M.L.; Dias, R.B.; Rocha, C.A.G.; Soares, M.B.P.; Vannier-Santos, M.A.; Bezerra, D.P. Combination Therapy of Curcumin and Disulfiram Synergistically Inhibits the Growth of B16-F10 Melanoma Cells by Inducing Oxidative Stress. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).