Submitted:

20 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Serological Panels and Participant Profile

2.3. Cloning, Expression, and Purification of DxCruziV3

2.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays

2.5. Lateral Flow Immunochromatographic Assay Preparation

2.6. Indirect Immunofluorescence

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

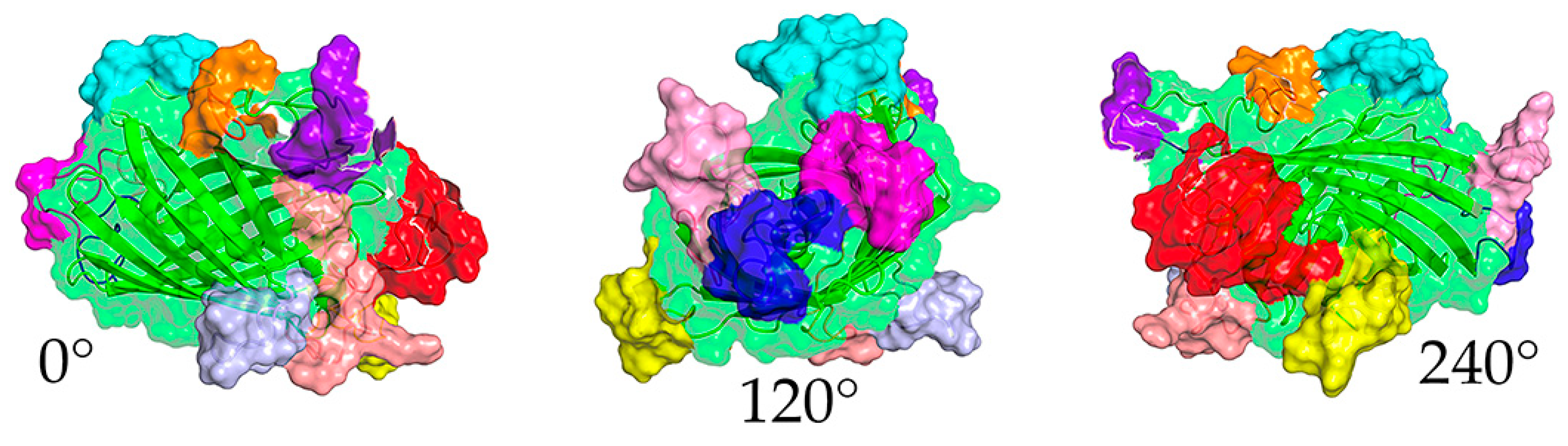

3.1. Design and Production of DxCruziV3

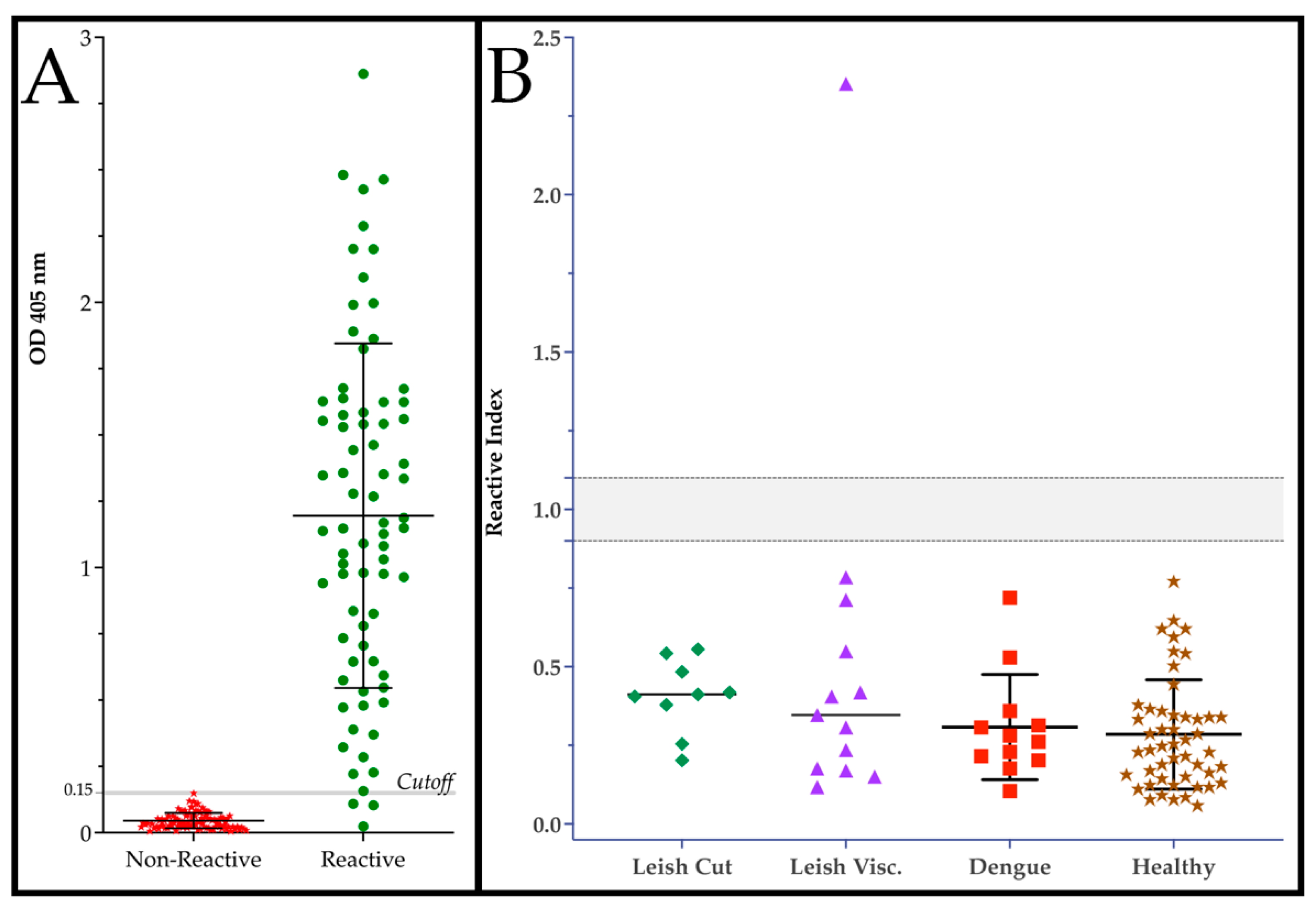

3.2. Performance of DxCruziV3 in ELISAs

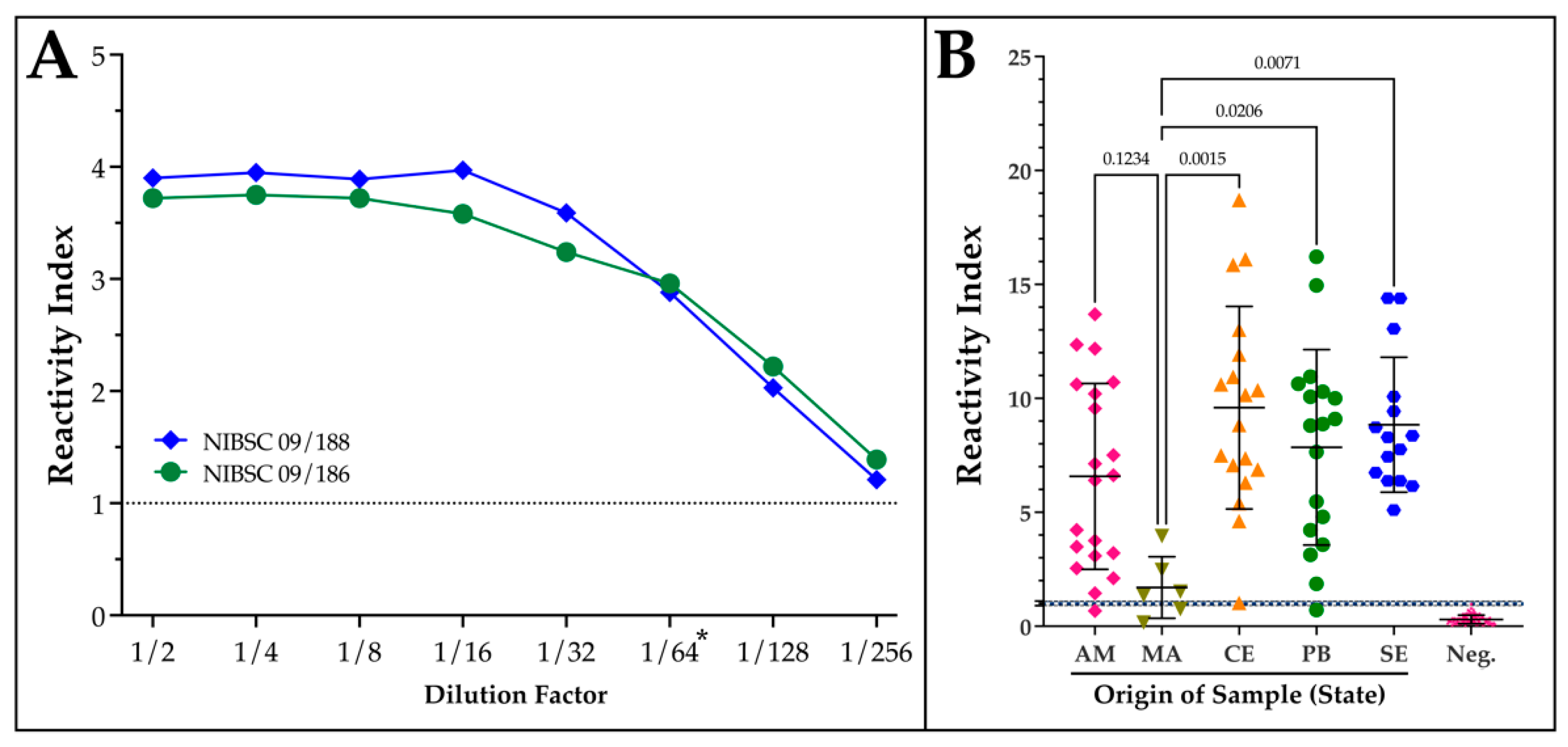

3.3. Analytical and Geographical Sensitivity of DxCruziV3

3.3. Lateral Flow Immunochromatographic Prototypes

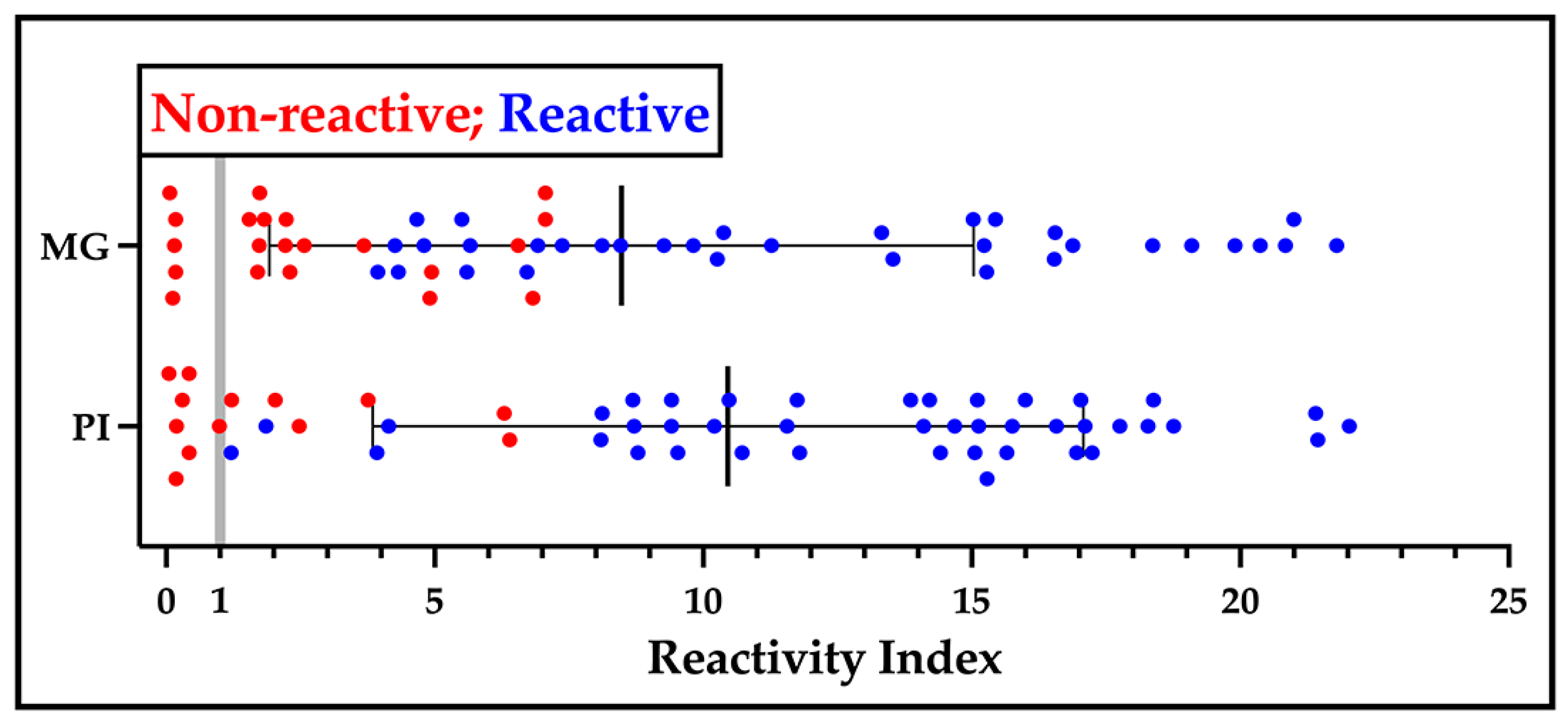

3.4. Performance of the LFA Prototypes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medina-Rincón, G.J.; Gallo-Bernal, S.; Jiménez, P.A.; Cruz-Saavedra, L.; Ramírez, J.D.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Medina-Mur, R.; Díaz-Nassif, G.; Valderrama-Achury, M.D.; Medina, H.M. Molecular and Clinical Aspects of Chronic Manifestations in Chagas Disease: A State-of-the-Art Review. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massad, E. The Elimination of Chagas’ Disease from Brazil. Epidemiol Infect 2008, 136, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.L.; Silva, T.P. [Transmission Elimination of Chagas’ Disease by Triatoma Infestans in Brazil: An Historical Fact]. 2006.

- Coura, J.R. The Main Sceneries of Chagas Disease Transmission. The Vectors, Blood and Oral Transmissions--a Comprehensive Review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanda Coutinho de Souza; José Rodrigues Coura; Catarina Macedo Lopes; Angela Cristina Verissimo Junqueira Eratyrus Mucronatus Stål, 1859 and Panstrongylus Rufotuberculatus (Champion, 1899) (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae): First Records in a Riverside Community of Rio Negro, Amazonas State, Brazil. Check List 2021, 17, 905–909. [CrossRef]

- Coura, J.R.; Viñas, P.A.; Junqueira, A.C. Ecoepidemiology, Short History and Control of Chagas Disease in the Endemic Countries and the New Challenge for Non-Endemic Countries. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coura, J.R.; Vinas, P.A. Chagas Disease: A New Worldwide Challenge. Nature 2010, 465, S6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 8Coura, J.R.; Dias, J.C. Epidemiology, Control and Surveillance of Chagas Disease: 100 Years after Its Discovery. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104 Suppl 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Chagas Disease (American Trypanosomiasis). 2023.

- Rassi, A.; Marcondes de Rezende, J. American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas Disease). Infect Dis Clin North Am 2012, 26, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, J.C.; Ramos, A.N.; Gontijo, E.D.; Luquetti, A.; Shikanai-Yasuda, M.A.; Coura, J.R.; Torres, R.M.; Melo, J.R.; Almeida, E.A.; Oliveira, W.; et al. [Brazilian Consensus on Chagas Disease, 2015]. Epidemiol Serv Saude 2016, 25, 7–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benziger, C.P.; do Carmo, G.A.L.; Ribeiro, A.L.P. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: Clinical Presentation and Management in the Americas. Cardiol Clin 2017, 35, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.C.P.; Beaton, A.; Acquatella, H.; Bern, C.; Bolger, A.F.; Echeverría, L.E.; Dutra, W.O.; Gascon, J.; Morillo, C.A.; Oliveira-Filho, J.; et al. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Current Clinical Knowledge and Management: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 138, e169–e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, E.C.; Nunes, M.C.P.; Blum, J.; Molina, I.; Ribeiro, A.L.P. Cardiac Involvement in Chagas Disease and African Trypanosomiasis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoni, N.R.; de Oliveira-da Silva, L.C.; Gonçalves, A.C.O.; Quintino, N.D.; Ferreira, A.M.; Bierrenbach, A.L.; Padilha da Silva, J.L.; Pereira Nunes, M.C.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Oliveira, C.D.L.; et al. Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Chagas Disease: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2024, 110, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, R.O. Management of Esophageal Dysphagia in Chagas Disease. Dysphagia 2021, 36, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Camargo, C.L.; Albajar-Viñas, P.; Wilkins, P.P.; Nieto, J.; Leiby, D.A.; Paris, L.; Scollo, K.; Flórez, C.; Guzmán-Bracho, C.; Luquetti, A.O.; et al. Comparative Evaluation of 11 Commercialized Rapid Diagnostic Tests for Detecting Trypanosoma Cruzi Antibodies in Serum Banks in Areas of Endemicity and Nonendemicity. J Clin Microbiol 2014, 52, 2506–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáez-Alquezar, A.; Junqueira, A.C.V.; Durans, A.M.; Guimarães, A.V.; Corrêa, J.A.; Borges-Pereira, J.; Zauza, P.L.; Cabello, P.H.; Albajar-Vinãs, P.; Provance, Jr., DW; et al. Geographical Origin of Chronic Chagas Disease Patients in Brazil Impacts the Performance of Commercial Tests for Anti-T. Cruzi IgG. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2021, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Durans, A.M.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Reis, F.C. G.; Dias, E.R.; Machado, L.E.S.F.; Lechuga, G.C.; Junqueira, A.C.V.; De-Simone, S.G.; Provance, Jr., D.W. Chagas Disease Diagnosis with Trypanosoma Cruzi Exclusive Epitopes in GFP. Vaccines (Basel) 2024.

- Ministry of Health PORTARIA No 57. 2018.

- Edwards, M.S.; Montgomery, S.P. Congenital Chagas Disease: Progress toward Implementation of Pregnancy-Based Screening. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2021, 34, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Close, D.W.; Paul, C.D.; Langan, P.S.; Wilce, M.C.; Traore, D.A.; Halfmann, R.; Rocha, R.C.; Waldo, G.S.; Payne, R.J.; Rucker, J.B.; et al. Thermal Green Protein, an Extremely Stable, Nonaggregating Fluorescent Protein Created by Structure-Guided Surface Engineering. Proteins 2015, 83, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2011, 1–244.

- Coura, J.R.; Junqueira, A.C. Ecological Diversity of Trypanosoma Cruzi Transmission in the Amazon Basin. The Main Scenaries in the Brazilian Amazon. Acta Trop 2015, 151, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. M. Saravia, S.; F. Montero, I.; M. Linhares, B.; A. Santos, R.; A. F. Marcia, J. Mineralogical Composition and Bioactive Molecules in the Pulp and Seed of Patauá (Oenocarpus Bataua Mart.): A Palm from the Amazon. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2020, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. I-TASSER Server for Protein 3D Structure Prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Kucukural, A.; Zhang, Y. I-TASSER: A Unified Platform for Automated Protein Structure and Function Prediction. Nat Protoc 2010, 5, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.C.; Longobardo, M.V.; Carmelo, E.; Marañón, C.; Planelles, L.; Patarroyo, M.E.; Alonso, C.; López, M.C. Mapping of the Antigenic Determinants of the T. Cruzi Kinetoplastid Membrane Protein-11. Identification of a Linear Epitope Specifically Recognized by Human Chagasic Sera. Clin Exp Immunol 2001, 123, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaglia, C.A.; Alfonso, J.; Campetella, O.; Frasch, A.C. Tandem Amino Acid Repeats from Trypanosoma Cruzi Shed Antigens Increase the Half-Life of Proteins in Blood. Blood 1999, 93, 2025–2032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- bañez, C.F.; Affranchino, J.L.; Macina, R.A.; Reyes, M.B.; Leguizamon, S.; Camargo, M.E.; Aslund, L.; Pettersson, U.; Frasch, A.C. Multiple Trypanosoma Cruzi Antigens Containing Tandemly Repeated Amino Acid Sequence Motifs. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1988, 30, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.M.; Teixeira, M.G.; Shreffler, W.G.; Pereira, J.B.; Burns, J.M.; Sleath, P.R.; Reed, S.G. Serodiagnosis of Chagas’ Disease by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Using Two Synthetic Peptides as Antigens. J Clin Microbiol 1994, 32, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.C.; Fernández-Villegas, A.; Carrilero, B.; Marañón, C.; Saura, D.; Noya, O.; Segovia, M.; Alarcón de Noya, B.; Alonso, C.; López, M.C. Characterization of an Immunodominant Antigenic Epitope from Trypanosoma Cruzi as a Biomarker of Chronic Chagas’ Disease Pathology. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012, 19, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M.; Shreffler, W.G.; Rosman, D.E.; Sleath, P.R.; March, C.J.; Reed, S.G. Identification and Synthesis of a Major Conserved Antigenic Epitope of Trypanosoma Cruzi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 1239–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, R.L.; Benson, D.R.; Reynolds, L.D.; McNeill, P.D.; Sleath, P.R.; Lodes, M.J.; Skeiky, Y.A.; Leiby, D.A.; Badaro, R.; Reed, S.G. A Multi-Epitope Synthetic Peptide and Recombinant Protein for the Detection of Antibodies to Trypanosoma Cruzi in Radioimmunoprecipitation-Confirmed and Consensus-Positive Sera. J Infect Dis 1999, 179, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3Balouz, V.; Cámara, M.L.; Cánepa, G.E.; Carmona, S.J.; Volcovich, R.; Gonzalez, N.; Altcheh, J.; Agüero, F.; Buscaglia, C.A. Mapping Antigenic Motifs in the Trypomastigote Small Surface Antigen from Trypanosoma Cruzi. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2015, 22, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.; Zingales, B. Trypanosoma Cruzi: Characterization of Two Recombinant Antigens with Potential Application in the Diagnosis of Chagas’ Disease. Exp Parasitol 1993, 76, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, C.; Gomes, L.P.; Coura, J.B.; Provance, D.W.J.; De-Simone, S.G. Chagas Disease-Specific Antigens: Characterization of Epitopes in CRA/FRA by Synthetic Peptide Mapping and Evaluation by ELISA-Peptide Assay. BMC Infect Dis 2013, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studier, F.W.; Moffatt, B.A. Use of Bacteriophage T7 RNA Polymerase to Direct Selective High-Level Expression of Cloned Genes. J Mol Biol 1986, 189, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagas, C. Nova Tripanozomiaze Humana. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1909, 1, 159–219. [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide, A.C.; Salo, W.; Madden, M.; Streitz, J.; Buikstra, J.; Guhl, F.; Arriaza, B.; Renier, C.; Wittmers, L.E.; Fornaciari, G.; et al. A 9,000-Year Record of Chagas’ Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 2034–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhl, F.; Jaramillo, C.; Yockteng, R.; Vallejo, G.A.; Cárdenas-Arroyo, F. Trypanosoma Cruzi DNA in Human Mummies. 1997.

- Coura, J.R. The Discovery of Chagas Disease (1908-1909): Great Successes and Certain Misunderstandings and Challenges. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2013, 46, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Castro, O.; Moo-Llanes, D.A.; Ramsey, J.M. Impact of Climate Change on Vector Transmission of Trypanosoma Cruzi (Chagas, 1909) in North America. Med Vet Entomol 2018, 32, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030. 2020.

- Porrás, A.I.; Yadon, Z.E.; Altcheh, J.; Britto, C.; Chaves, G.C.; Flevaud, L.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Ribeiro, I.; Schijman, A.G.; Shikanai-Yasuda, M.A.; et al. Target Product Profile (TPP) for Chagas Disease Point-of-Care Diagnosis and Assessment of Response to Treatment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0003697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, Z.C.; Sousa, O.E.; Marques, W.P.; Saez-Alquezar, A.; Umezawa, E.S. Evaluation of Serological Tests to Identify Trypanosoma Cruzi Infection in Humans and Determine Cross-Reactivity with Trypanosoma Rangeli and Leishmania Spp. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2007, 14, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daltro, R.T.; Leony, L.M.; Freitas, N.E.M.; Silva, Â.A.O.; Santos, E.F.; Del-Rei, R.P.; Brito, M.E.F.; Brandão-Filho, S.P.; Gomes, Y.M.; Silva, M.S.; et al. Cross-Reactivity Using Chimeric Trypanosoma Cruzi Antigens: Diagnostic Performance in Settings Where Chagas Disease and American Cutaneous or Visceral Leishmaniasis Are Coendemic. J Clin Microbiol 2019, 57, e00762-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, M.; Hockley, J.; Bracho, C.G.; Rijpkema, S.; Luguetti, A.O.; Duncan, R.; Rigsby, P.; Albajar-Viñas, P.; Padilla, A. Evaluation of Two International Reference Standards for Antibodies to Trypanosoma Cruzi in a WHO Collaborative Study. WHO Technical Report 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saez-Alquezar, A.; Junqueira, A.C.; Durans, A.M.; Guimarães, A.V.; Corrêa, J.A.; Provance, J., DW; Cabello, P.H.; Coura, J.R.; Viñas, P.A. Application of WHO International Biological Standards to Evaluate Commercial Serological Tests for Chronic Chagas Disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, A.D.; Bracco, L.; Salas-Sarduy, E.; Ramsey, J.M.; Nolan, M.S.; Lynn, M.K.; Altcheh, J.; Ballering, G.E.; Torrico, F.; Kesper, N.; et al. The Trypanosoma Cruzi Antigen and Epitope Atlas: Antibody Specificities in Chagas Disease Patients across the Americas. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coura, J.R.; Junqueira, A.C.; Ferreira, J.M.B. Surveillance of Seroepidemiology and Morbidity of Chagas Disease in the Negro River, Brazilian Amazon. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2018, 113, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- William Provance, D.; da Matta Durans, A.; Lechuga, G.C.; da Rocha Dias, E.; Morel, C.M.; De Simone, S.G. Surpassing the Natural Limits of Serological Diagnostic Tests. hLife 2024, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.G.; de Souza, K.R.; Júnior, P.A.S.; Câmara, C.C.; Castelo-Branco, F.S.; Boechat, N.; Carvalho, S.A. Tackling the Challenges of Human Chagas Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Treatment Strategies in the Chronic Phase and Emerging Therapeutic Approaches. Acta Trop 2024, 256, 107264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Padilla, J.; López, M.C.; Esteva, M.; Zrein, M.; Casellas, A.; Gómez, I.; Granjon, E.; Méndez, S.; Benítez, C.; Ruiz, A.M.; et al. Serological Reactivity against T. Cruzi-Derived Antigens: Evaluation of Their Suitability for the Assessment of Response to Treatment in Chronic Chagas Disease. Acta Trop 2021, 221, 105990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Padilla, J.; Abril, M.; Alarcón de Noya, B.; Almeida, I.C.; Angheben, A.; Araujo Jorge, T.; Chatelain, E.; Esteva, M.; Gascón, J.; Grijalva, M.J.; et al. Target Product Profile for a Test for the Early Assessment of Treatment Efficacy in Chagas Disease Patients: An Expert Consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Epitope | Sequence | Insertion Site1 | Color2 | Protein Origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KFAELLEQQKNAQFPGK | N-term | Red | KMP11 | [29] |

| 2 | DSSAHSTPSTPA | 50 | Blue | SAPA | [30] |

| 3 | GDKPSPFGQAAAADK | 114 | Yellow | PEP-2 | [31,32] |

| 4 | FGQAAAGDKPS | 127 | Magenta | TcCA-2 | [33] |

| 5 | AEPKPAEPKS | 153 | Lt. Blue | TcD-2 | [34,35] |

| 6 | TSSTPPSGTENKPAT | 167 | Cyan | TSSA | [36] |

| 7 | GTSEEGSRGGSSMPS | 183 | Salmon | TcLo1.2 | [35] |

| 8 | SPFGQAAAGDK | 244 | Pink | B13 | [32,37] |

| 9 | KAAIAPA | C-term | Purple | TcE | [35] |

| 10 | KQRAAETK | C-term | Orange | CRA | [38] |

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Likelihood Ratio | Pos. Likelihood Ratio | Neg. Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96.0% | 100% | 98.6 | 98.8% | 95.3% |

| Assay | Repititions1 | Volume | Reactive | Non-reactive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V3ib-LFA Field2 | 1 | 10 µl | 43 | 124 |

| sV3-LFA Field2 | 1 | 10 µl | 43 | 124 |

| V3ib-LFA Lab3 | 0-1 | 5 µl | 45 | 25 |

| sV3-LFA Lab (Lot#1)3 | 0-1 | 5 µl | 44 | 123 |

| sV3-LFA Lab (Lot #2)4 | 1 | 5 µl | 36 | 131 |

| V3ib ELISA (in-house) | 3-8 | 0.5-2 µl | 39 | 128 |

| ELISA Wiener | 2-3 | 10 µl | 32 | 135 |

| ELISA Bioclin | 2 | 10 µl | 61 | 106 |

| Immunofluorescence Indirect | 1-2 | 5 µl | 48 | 119 |

| Assay | Non-Divergent (n=150) | Final Call (n=167) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Field V3ib LFA | 100% | 100% | 95.2% | 97.6% |

| Field sV3 LFA | 100% | 100% | 90.5% | 96.0% |

| V3ib-ELISA | 87.5% | 98.3% | 87.5% | 97.6% |

| ELISA Wiener | 71.9% | 97.5% | 64.3% | 96.0% |

| ELISA Bioclin | 90.6% | 79.7% | 83.3% | 79.2% |

| Immunofluorescence | 93.8% | 88.1% | 76.2% | 87.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).