1. Introduction

Microwave heating has increasingly garnered attention from both industry and academia due to its unique advantages in thermal processing, such as selective and volumetric heat generation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Its applications are vast, encompassing food processing [

6,

7,

8], biological treatment [

9], chemical reactions [

10,

11,

12,

13] and more. Compared to traditional heating methods, microwave continuous-flow heating offers higher heating efficiency [

1,

14,

15,

16,

17] and better environmental benefits [

1,

18], which are crucial for enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of chemical production. Microwave continuous-flow heating harnesses microwave energy to rapidly and uniformly heat liquid loads, effectively achieving various processing goals such as rapid extraction [

19] and increased reaction rates [

11,

20,

21,

22]. The range of liquids applicable for microwave continuous-flow heating is extensive. Except for substances with very low tangent loss angles [

23], microwave heating can be directly applied to liquids like wastewater [

24], glycerol [

25], etc. However, the geometric characteristics of microwave heating containers significantly impact the distribution of the electromagnetic field [

27]. Additionally, the dynamic changes in the permittivity of loads during heating [

12,

17] can lead to an uneven electromagnetic field distribution within non-tuned heating containers, reducing the efficiency and uniformity of microwave heating [

28,

29] and adversely affecting practical chemical production processes. Therefore, improving the adaptability of microwave heating systems to a large range of dynamic permittivity and ensuring uniform heating of permittivity liquids are key to enhancing heating performance.

To address these issues, scholars have conducted numerous researches. Li et al. designed an efficient single-mode traveling wave reactor for continuous flow processing. This reactor features a large reaction chamber and utilizes a highly efficient single-mode traveling wave based on a rectangular waveguide. It can achieve efficient and uniform heating of loads with different dielectric constants, with heating efficiency exceeding 99% and a COV of less than 0.4 [

30]. Xu et al. proposed a continuous-flow microwave heating system based on a coaxial inner conductor structure, utilizing the uniform sectional electric field distribution in the TEM mode to improve heating uniformity. Additionally, their research explored the effects of different permittivity and loss tangent angles on the heating efficiency of liquid loads in the system [

31]. Through modeling analysis, Kapranov and Kouzaev verified that the coaxial structure of the microwave heating chamber can obtain uniform electric field distribution, resulting in uniform temperature distribution [

32]. Also, Zafar et al. demonstrated that employing a helical tube can effectively enhance the uniformity of microwave heating [

33]. Ye et al. designed a helical screw microwave heating system for biodiesel synthesis, calculating the heating process under different pitch and inlet speed parameters, and determined that adjusting these parameters could optimize the heating performance of the reactor [

34]. Zhu et al. designed an electromagnetic black hole heating system based on metamaterials, achieving high efficiency and stability under large dynamic range variations of permittivity [

35].

Nevertheless, the aforementioned work has some limitations. On one hand, while using a rectangular waveguide can increase power capacity, it also leads to uneven heating of the liquid in the width direction [

30]. Besides, rectangular and circular waveguides are less scalable in engineering applications compared to coaxial waveguides [

32]. On the other hand, most of the heating devices based on coaxial structures proposed before have disadvantages, such as the small volume of heated liquid [

31], the need for additional support structures for the helical tube [

33], and the high costs associated with using metamaterials [

35]. Hence, we develops a novel microwave heating device based on coaxial structure to supply the demands of microwave continuous-flow heating with a large dynamic range of permittivity, high efficiency, great uniformity, and ease of handling.

In this study, we first established a model of the proposed device for microwave continuous heating and performed a simulation. Subsequently, we conducted experiments on liquid loads with different permittivity to validate the accuracy of the model. Simulation analysis shows that the uniform distribution of the sectional electric field in the TEM mode of the coaxial structure can enhance heating uniformity. Furthermore, the efficiency and uniformity of the heating device were analyzed under various permittivity loads, as well as the impact of channel radius on heating efficiency, confirming the stability of the heating device's efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geometric Model

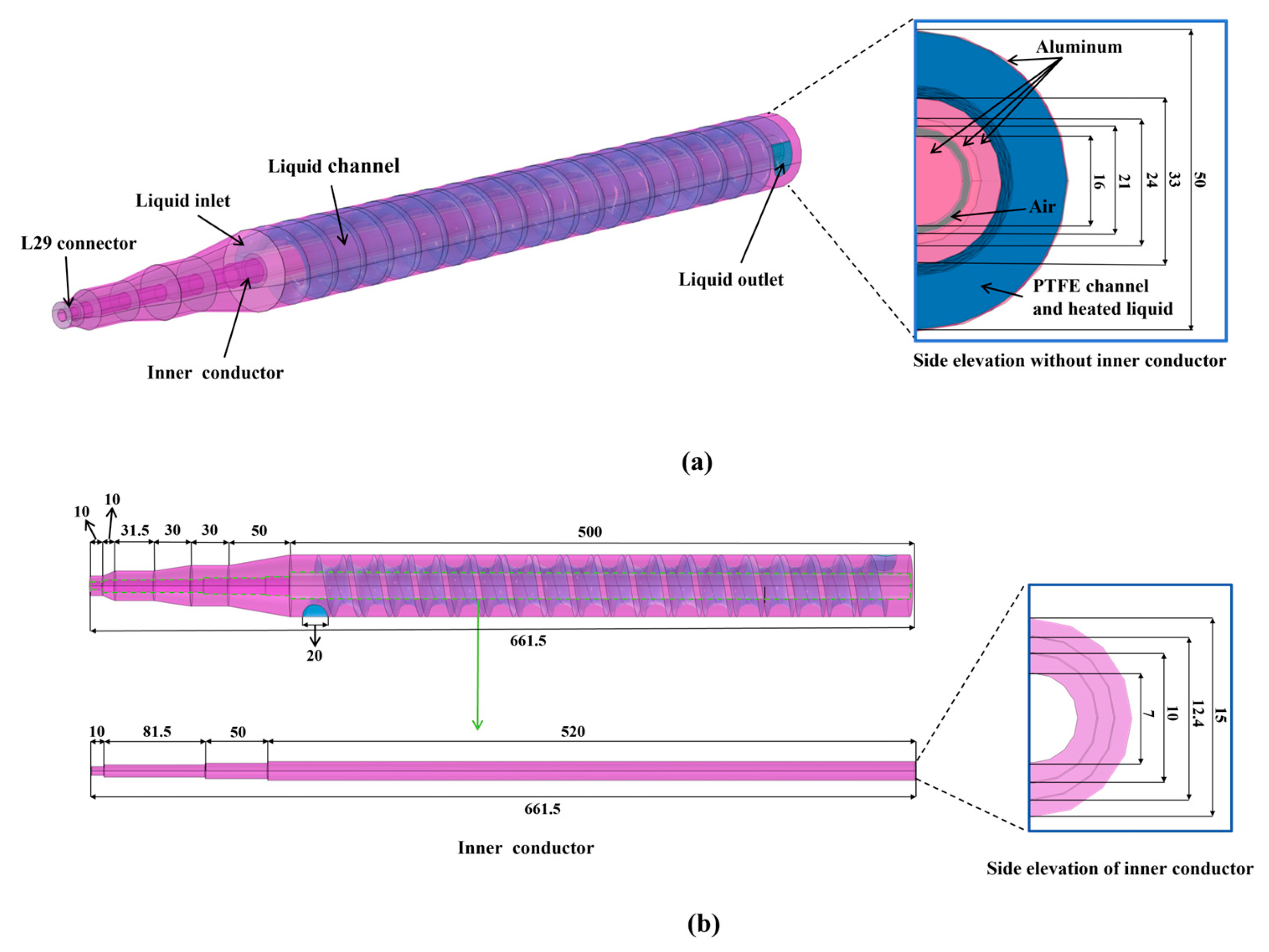

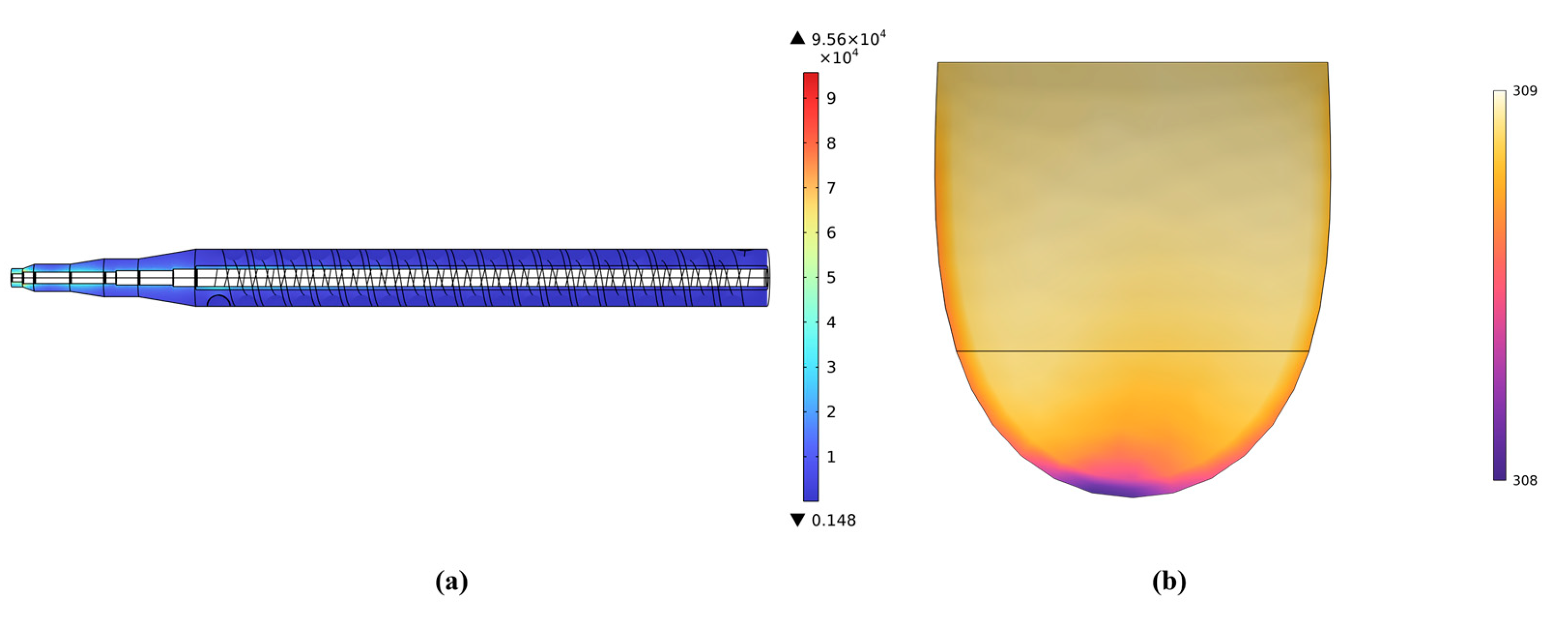

The coaxial microwave heating device was modeled using COMSOL Multiphysics (6.1, COMSOL Inc., Stockholm, Sweden). As can be seen from

Figure 1, the heating device comprises three structures: an L29 connector for microwave input, a stepped impedance transition section, and a coaxial structure, which is the main part of the device.

The L29 connector features an inner conductor radius of 3.5 mm and an outer conductor radius of 8 mm, with a length of 10 mm. The space between the inner and outer conductors is set as air.

For the stepped impedance transition section, the inner conductor begins with a cylinder of a radius of 5mm and a length of 81.5 mm; it then transitions to a radius of 6.2 mm and a length of 50 mm; and finally, to a radius of 7.5 mm and length 20 mm to match the coaxial body’s inner conductor radius. The outer conductor is formed by a frustum of a cone with a radius increasing gradually from 8 mm to 12 mm over a length of 10 mm, followed by a cylinder of radius 12 mm and length 31.5 mm. Then, it becomes a frustum of a cone with a radius increasing gradually from 12 mm to 16.5 mm over a length of 30 mm, followed by a cylinder of radius 16.5 mm and length 30 mm, and another frustum of a cone growing from 16.5 mm to 25 mm over a length of 50 mm, aligning with the coaxial body’s outer conductor radius.

The coaxial main part itself has an inner conductor of radius 7.5 mm, an outer conductor radius of 25 mm, and a length of 500 mm. There are holes drilled at both ends of the outer conductor wall, allowing liquid to flow in through one hole and out through the other.

The liquid channel is crafted from a PTFE rod with an inner radius of 10.5 mm, an outer radius of 25 mm, and a length of 500 mm, featuring a helical groove. The helix has a pitch of 25 mm, with 18.5 turns, and the cutting shape is semicircular with a radius of 10 mm. The initial cut of the semicircle is 20 mm away from the boundary.

Microwaves are fed into the coaxial body through the L29 connector, passing through the stepped impedance transition section to heat the liquid substances. The microwave frequency is 2.45 GHz, with an input power of 200 W, operating in the TEM mode.

2.2. Modeling Assumption

Several assumptions were made in the model of this coaxial microwave liquid heating equipment:

(1) The air was transparent to the microwave; therefore, it was not heated by the microwave, meaning that the temperature of the air between the coaxial line inner conductor remains constant in the heating process.

(2) The fluid was assumed to be incompressible, and the initial velocity of the fluid entering the channel was considered constant.

(3) The surface roughness of channel and cavities was disregarded.

All surfaces of the wave guide were assumed to be perfect electric conductors except for the feed port.

2.3. Governing Equations

The model has integrated the following aspects: electromagnetic waves, heat transfer, and hydrodynamics. Hence, governing equations were derived from these physical fields.

In the uniform dielectric, the Helmholtz equation, which is the wave equation of the electromagnetic filed, can be written as:

where

is the relative permeability;

signifies the electric filed intensities;

and

represent the real part and the imaginary part of the permittivity of the processing material, respectively;

denotes the angular wave frequency; and

is the propagation speed of light in vacuum (

). The equation above can show how the microwave works in the coaxial struture, including all the dielectric, liquid, PTFE, and air.

Accordingly, the electromagnetic power loss

can be calculated by employing electric-field strength and dielectric properties from Equation (1), as follow:

shows the dissipated power of electromagnetic wave in unit volume medium and the density of energy that the water absorbs is in direct proportion to , meaning that the greater is the , the greater is the energy that the water absorbs in.

Besides the equations in the electromagnetic filed above, the equations in the fluid filed are also significant. Fourier's law of heat conduction states that the heat flux in a continuous medium is proportional to the temperature gradient:

where

is the conductive heat flux; and

denotes the material thermal conductivity.

The Fourier equation is used to express how the heat transfer in the fluid:

where

is the liquid density;

is the material specific heat capacity;

represents the temperature of the liquid; and

denotes the velocity of the liquid. So by solving the Fourier equation, the distribution temperature of the heated flowing liquid can be obtained.

To figure out the velocity distribution of the fluid, the continuity equation in hydrodynamics can be expressed as follow:

Equation (5) shows the conservation of mass in the fluid. Since the fluid is supposed to be incompressible, the equation can be simplified as:

Furthermore, the conservation of momentum in the incompressible fluid, which is the Navier-Stokes equation, can be expressed as follow:

where

is the pressure intensity per unit volume;

signifies the constant viscosity of the liquid; and

equates to

, which denotes the divergence of the stress deviator tensor.

2.4. Boundary Conditions and Initial Values

In this study, because all surfaces of the wave guide were assumed to be perfect electric conductors except for the wave port, their boundary condition satisfies:

where

is the unit normal vector of the corresponding surface.

The scattering boundary conditions were utilized in the inlet and outlet regions of the fluid, respectively.

In the wall of the trough, a no-slip condition was employed on the liquid velocity, while a wall function boundary condition was applied using the laminar flow model. Free slip conditions were prescribed at the liquid surface, and the pressure was set equal to atmospheric pressure. Constraints on the outlet of the laminar flow model included pressure and backflow suppression.

The initial temperature of the system was set to be uniform, with a value of 293.15 K. The adiabatic condition was applied at the boundaries of the domain consisting of the heated liquid and PTFE, which can be expressed as:

2.5. Input Parameters

Owing to the variation of material properties with temperature during heating, and the sensitivity of the heating efficiency and uniformity of the continuous-flow microwave heating system to the properties of materials inside the system (such as permittivity, thermal conductivity, dynamic viscosity, specific heat capacity, and density), it is necessary to determine the properties of the materials in the system. The table below provides the properties of various materials within the model. Properties with relatively small changes can be considered constant, whereas those with enormous variations are described by functions [

6,

31,

36].

Table 1.

Input parameter of the model.

Table 1.

Input parameter of the model.

| Property |

Domains |

Value |

Unit |

| Real part of relative permittivity |

Air |

1 |

-- |

| PTFE |

2.1 |

-- |

| Water |

|

-- |

| Ethanol |

|

-- |

| Imaginary part of relative permittivity |

Air |

0 |

-- |

| PTFE |

0 |

-- |

| Water |

|

-- |

| Ethanol |

|

-- |

| Relative permeability |

All |

1 |

-- |

| Thermal conductivity |

PTFE |

0.24 |

W/m⋅K |

| Water |

|

W/m⋅K |

| Ethanol |

|

W/m⋅K |

| Aluminum |

|

W/m⋅K |

| Density |

PTFE |

2200 |

kg/m3

|

| Water |

|

kg/m3

|

| Ethanol |

|

kg/m3

|

| Aluminum |

2700 |

kg/m3

|

| Specific heat capacity |

PTFE |

1050 |

J/ kg⋅K |

| Water |

|

J/ kg⋅K |

| Ethanol |

|

J/ kg⋅K |

| Aluminum |

|

J/ kg⋅K |

2.6. Experimental Setup

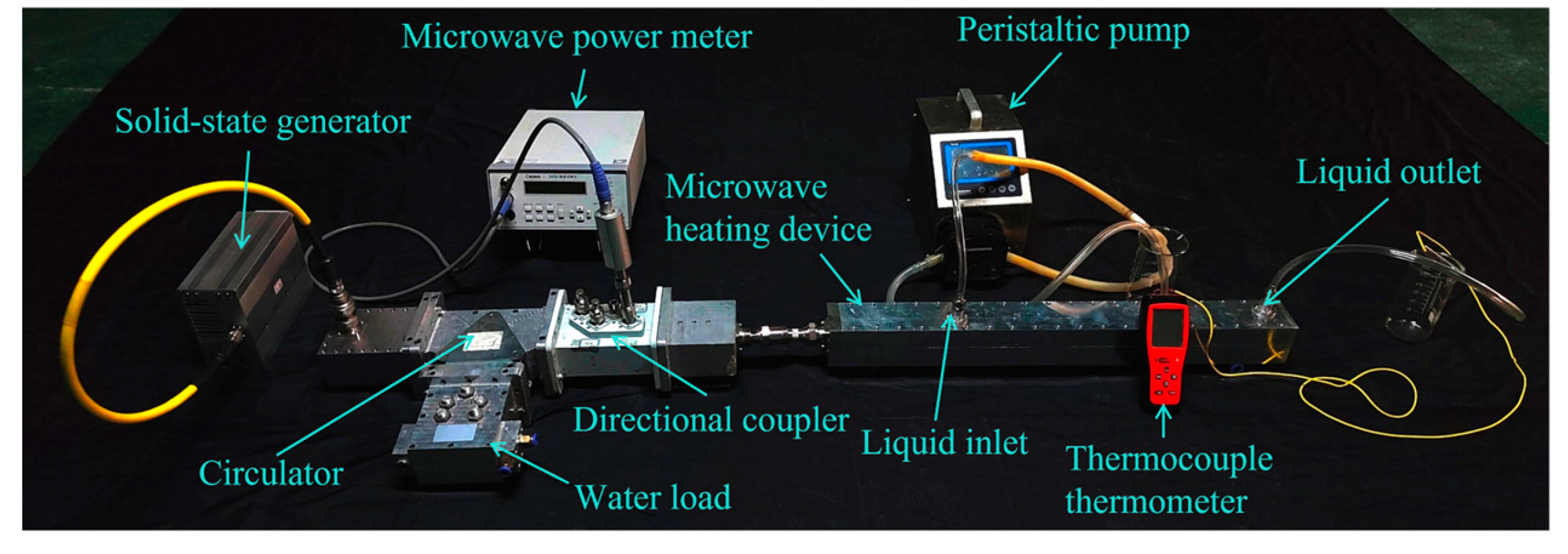

To confirm the accuracy of the simulation model, experiments were conducted. The experimental setup, as shown in

Figure 2, used a solid-state generator (WSPS-2450–1 K-ccwb, Wattsine, Chengdu, China) to provide microwave input, delivering energy to the coaxial heating device through a waveguide coaxial converter and a circulator (CIWG22–2450-2KWA101010, Euler Microwave, Sichuan Province, China). The microwave input power was set to 200 W with a frequency of 2.45 GHz. The opposite terminal of the circulator is linked to a water load for absorbing the reflected microwaves and safeguarding the solid-state generator. A directional coupler (Loop-E22DC40A10N, Euler Microwave, Sichuan Province, Chengdu, China), microwave power meter (AV2433, 41st Institute of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, Anhui Province, China), and the liquid sample ((Wahaha Co., Ltd., Zhejiang, China) in the microwave heating device constituted the microwave power measurement system. The flow rate of the incoming liquid was controlled by a peristaltic pump (V-3 L, Baoding Shenchen Pump Industry Co., Ltd., Hebei Province, China), and the temperature at the center of the liquid outlet was measured using a thermocouple thermometer (TP678, MITIR, Zhejiang Province, Wenzhou, China).

To begin with the experiment, we calibrated the microwave power meter, and measured the microwave network parameters. The liquid was then filled into the tube. Subsequently, the flow rate of the incoming liquid was adjusted utilizing the peristaltic pump. Next, the microwave source with an input power of 200 W was turned on. During the experiment, we observed and recorded the changes in the readings of the power meter and thermocouple. Finally, after heating for 60 s, the microwave generator was turned off.

To validate the accuracy of the simulation, the experiment requires configuring liquids with different permittivity. By mixing ethanol and deionized water (Chengdu Changlian Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., Chengdu, China) in varying volume ratios, solutions with different permittivity can be obtained. This characteristic can be utilized to prepare the various solutions needed for the experiment. Zhu et al. measured the volume ratios of ethanol to water and their corresponding relative permittivity, as shown in the table [

35].

Table 2.

Relative permittivity at different ethanol volume ratios at 293.15 K.

Table 2.

Relative permittivity at different ethanol volume ratios at 293.15 K.

| Volume ratio of ethanol (%) |

Real part of relative permittivity |

Imaginary part of relative permittivity |

| 0 |

83.77 |

10.05 |

| 10 |

75.99 |

11.51 |

| 20 |

65.52 |

12.59 |

| 30 |

60.72 |

14.09 |

| 40 |

55.16 |

15.74 |

| 50 |

45.75 |

15.52 |

| 60 |

38.45 |

15.45 |

| 70 |

31.49 |

15.24 |

| 80 |

18.74 |

12.87 |

| 90 |

14.41 |

11.55 |

| 100 |

8.48 |

7.64 |

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Validation

S parameter is used to describe the transmission and reflection of electromagnetic waves at the system ports. For the evaluation of the efficiency of a single-port microwave heating system, the S11 parameter is commonly used, representing the ratio of reflected energy to input energy at the port. S11 is typically expressed in dB. The relationship between efficiency and S11 parameter is as follows:

It can be calculated that when S11 is less than 10dB, the heating efficiency of the system can exceed 90%.

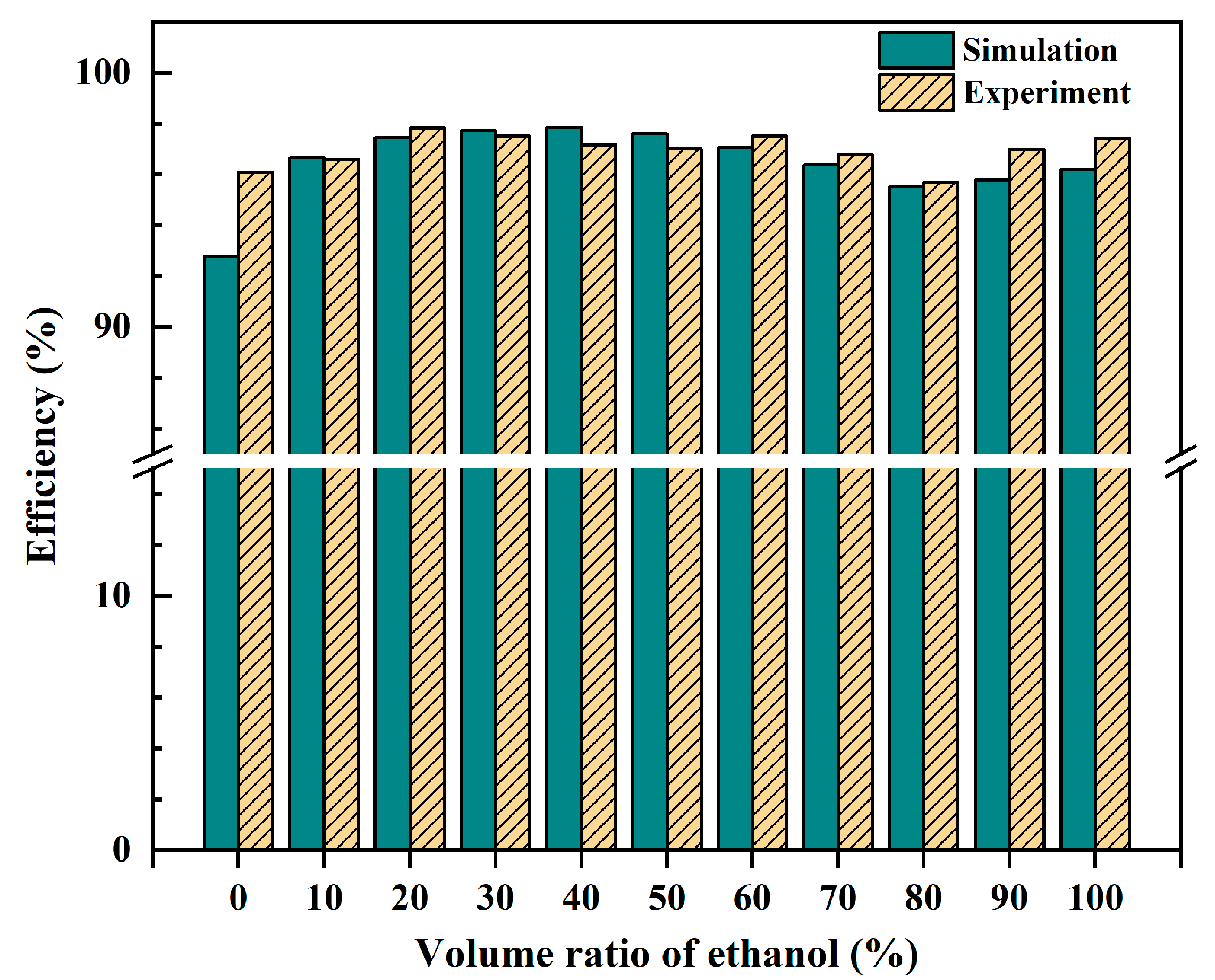

The S11 parameter of the continuous flow system was measured using the microwave power meter during the experiment. As shown in

Figure 3, the experimental results indicate that the heating efficiency of the solution with different ethanol volume ratio exceed 90%, which is basically consistent with the simulation results, proving the accuracy of the simulation model. Both results of the experiment and simulation also verify that the proposed device has a stable heating efficiency.

The discrepancies between the experimental results and simulation results may be attributed to differences between the actual properties of the liquids and theoretical values. Additionally, some insertion losses were neglected. These include the losses introduced during the coupling of L29 connectors with the coaxial structure during processing.

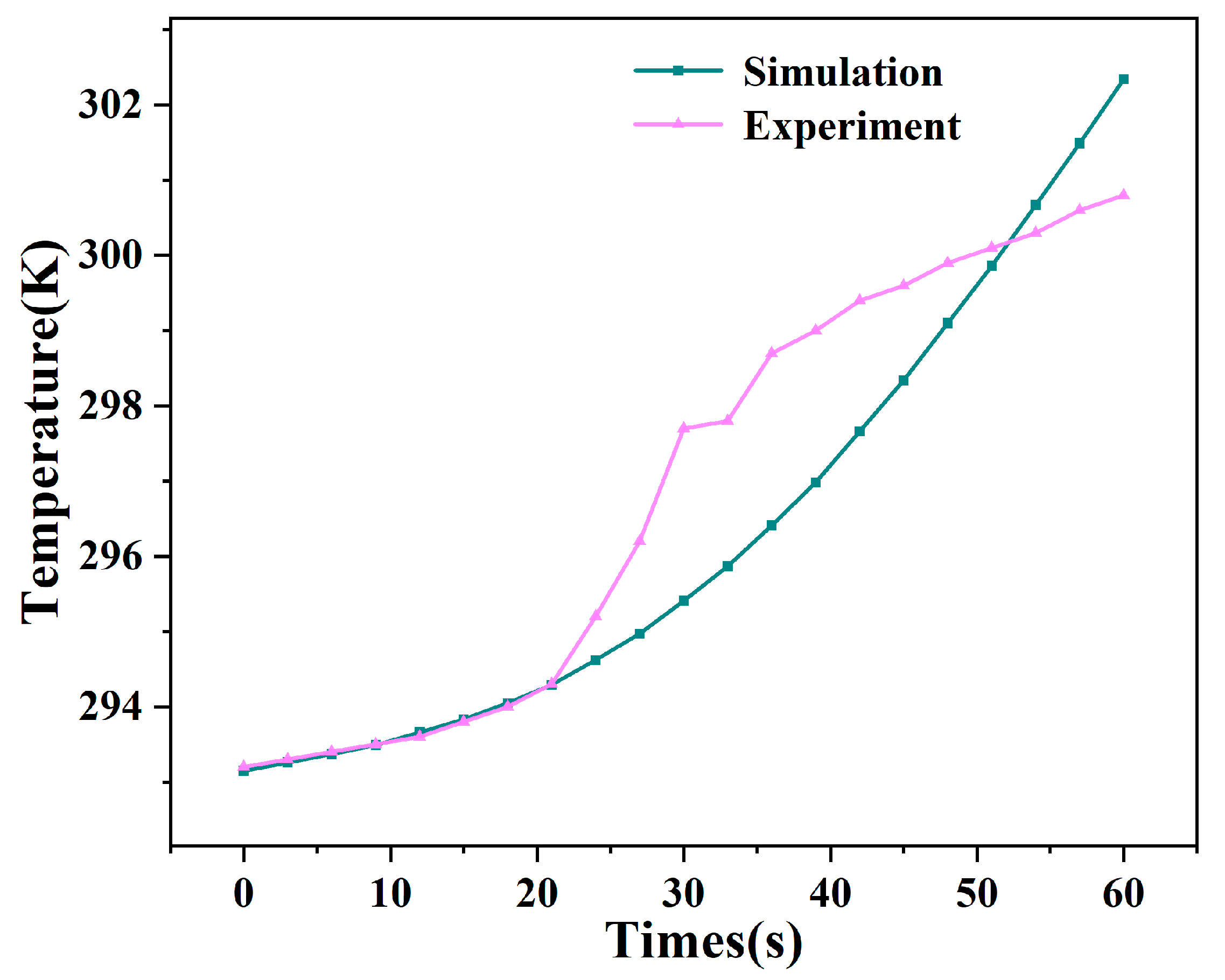

Figure 4 shows the temperature variation at the center point of the outlet cross-section during simulation and experimentation. It can be seen that the experimental and simulation results are in good agreement, further validating the effectiveness of the simulation model.

It can be observed that the measured outlet temperature is slightly higher than the initial simulation temperature. This discrepancy may be due to voltage instability during the experiment, causing the peristaltic pump flow rate to differ from the simulation, leading to the heated water flowing out earlier. Another possibility is the lag in the thermometer's response, preventing real-time data recording [

27]. After reaching a stable temperature, a difference between the simulated and experimental temperatures is observed. This could be due to the small diameter of the pipe, resulting in a mismatch between the ideal and actual measurement points. Moreover, the difference in water temperature between the experiment and room temperature might lead to extra heat exchange. Overall, the experimental results generally align with the simulations, validating the model's accuracy.

3.2. Electric Field Distribution during Water Heating

Using a coaxial structure can achieve a more uniform electric field distribution, resulting in better heating uniformity.

Figure 5(a) illustrates the electric field distribution of water heating calculated by COMSOL. It can be seen that the electric field distribution is relatively uniform for electromagnetic waves operating in the TEM mode within the coaxial structure.

Figure 5(b) shows the temperature distribution at the outlet cross-section after heating for 60 seconds, with a water flow rate of 0.06 m/s. The temperature distribution at the outlet cross-section is very uniform. This verifies that the microwave heating device based on coaxial structure, which is designed in this study, provides good heating uniformity.

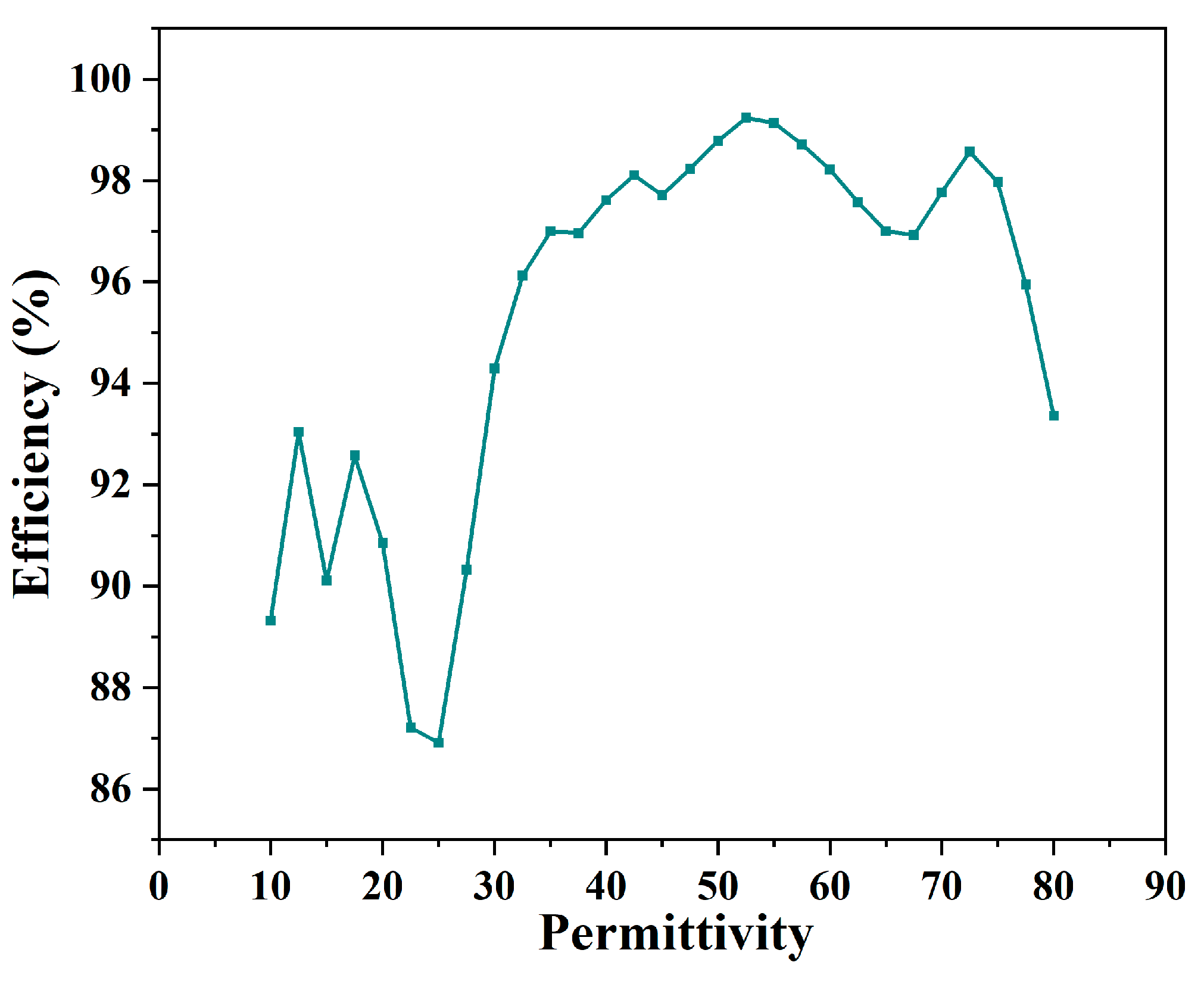

3.3. Heating Efficiency under Different Permittivity

For the coaxial microwave heating device constructed above, we performed simulations using COMSOL software to examine its efficiency variation under a large dynamic range of permittivity. In COMSOL, the range of permittivity for the heated liquid was set from 10 to 80, with a step size of 2.5 for parametric scan, while the loss tangent remained constant at 0.1.

The simulation results are shown in

Figure 6. It can be seen that the coaxial microwave heating device proposed in this paper achieves a heating efficiency of over 90% for most permittivity, with the minimum efficiency being 87%. This indicates that the designed tuning structure can make the device robust to large dynamic changes in permittivity, preserving a high and stable thermal efficiency.

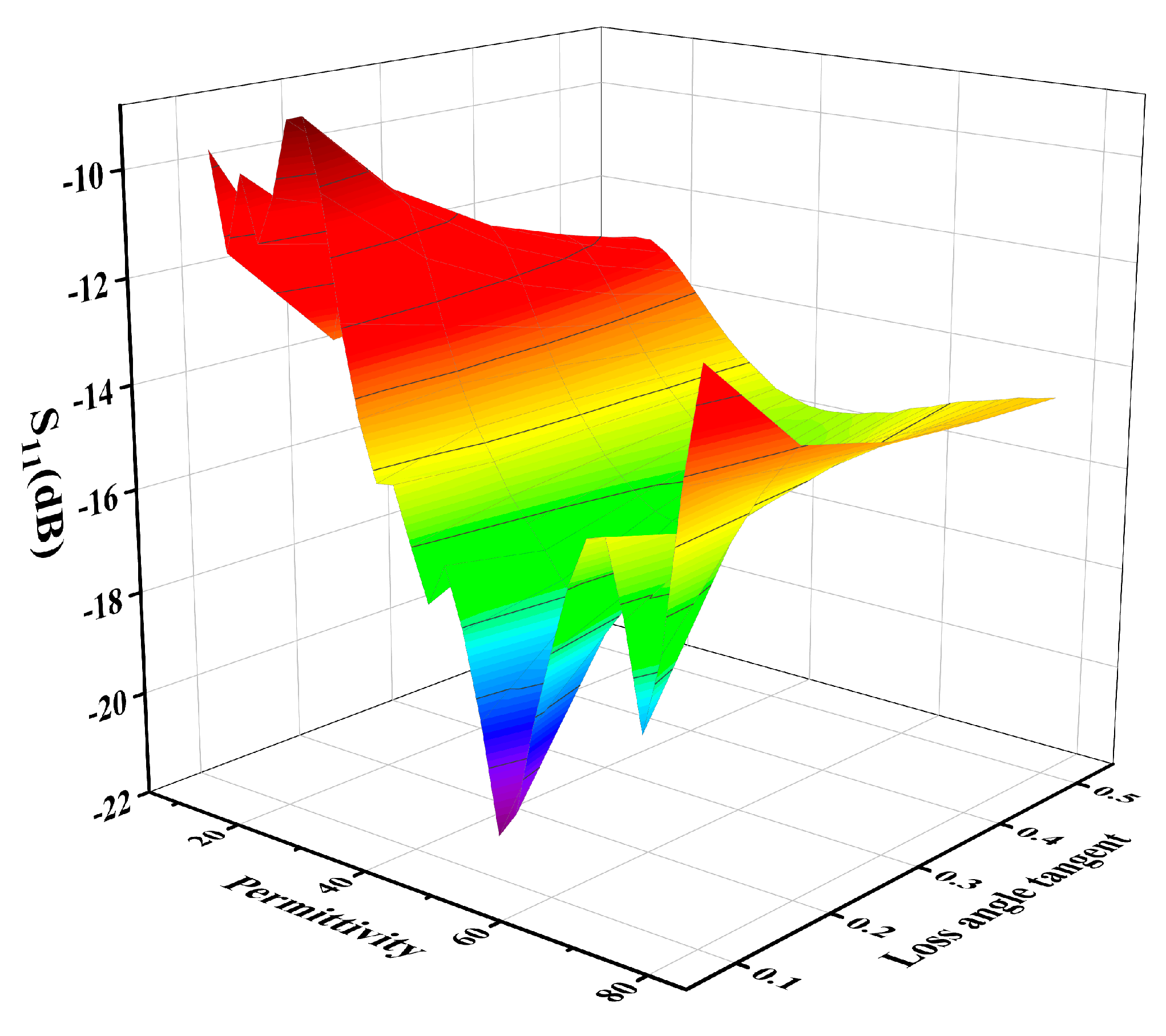

In actual heating processes, the dielectric properties of materials may change. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the impact of different loss tangent angles on heating efficiency.

Figure 7 shows the corresponding changes in the S11 parameter as the loss tangent of the heating liquid varies from 0.1 to 0.5. It can be seen that the heating efficiency of the device remains relatively stable with changes in permittivity and loss tangent. When the loss tangent is between 0.2 and 0.5, the S11 parameter is below -10 for all permittivity, indicating an efficiency of over 90%. Only when the loss tangent is 0.1 does the S11 parameter exceed -10 for some permittivity. This indicates that the proposed microwave heating device has very good efficiency stability.

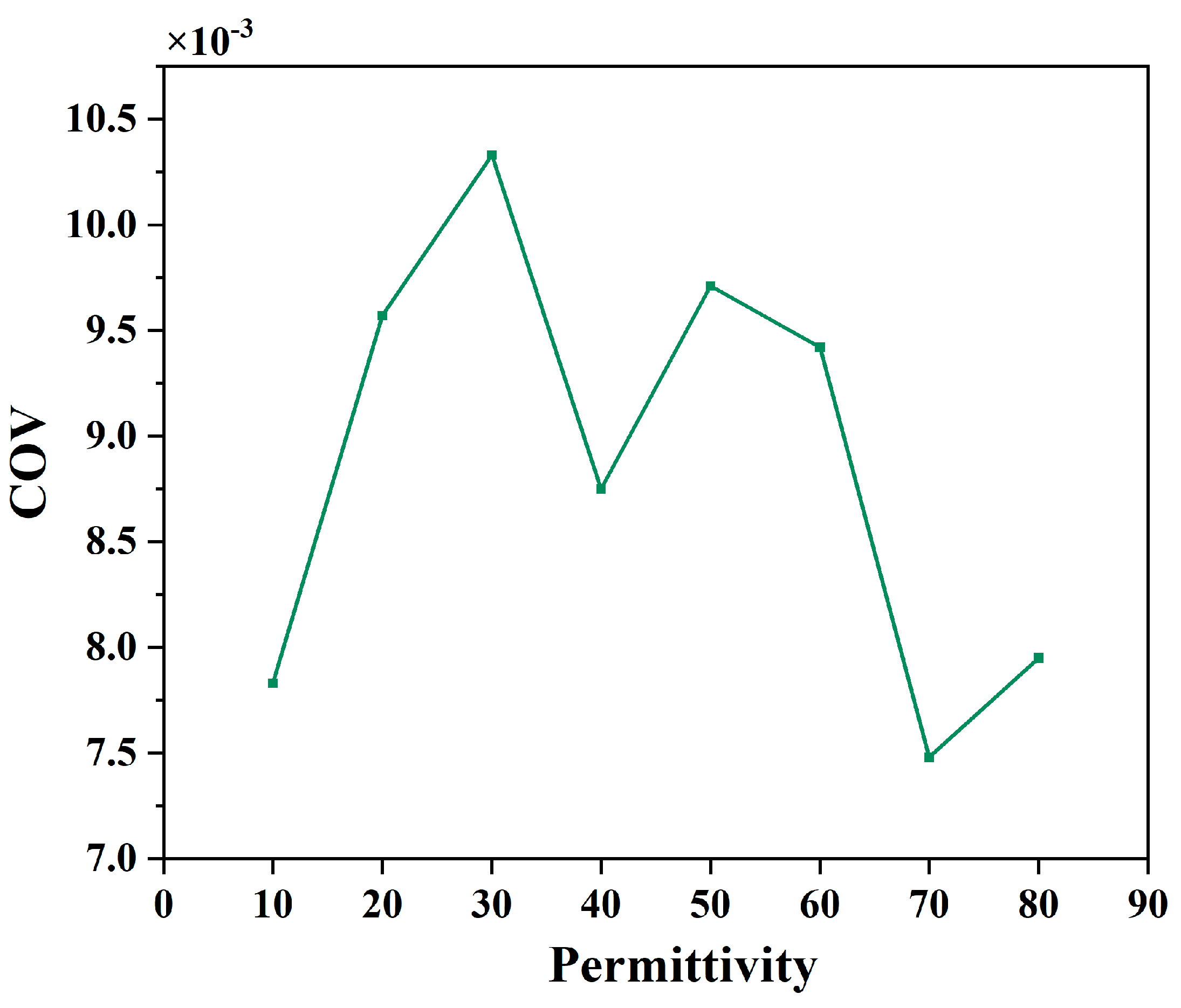

3.4. Uniformity under Different Permittivity

The variation in permittivity also impacts the heating uniformity of heated liquids. To investigate heating uniformity, the concept of the coefficient of variation (COV) is introduced. COV is typically used to quantify the uniformity of temperature distribution. A lower COV indicates a smaller temperature difference, implying better temperature distribution uniformity. The COV can be expressed by the following equation:

where

is the total number of sampling points,

is the temperature of the heated substance at point

i,

denotes the average temperature of the heated substance, and

signifies the initial temperature of the heated substance.

Figure 8 illustrates the variation of COV at the outlet cross-section of the liquid under conditions where the permittivity changes from 10 to 80 in increments of 10. It can be seen that the COV at the outlet of the heated liquid is consistently below

. This result indicates that the proposed device provides great heating uniformity for liquids with different permittivity.

3.4. Influence of Channel Radius

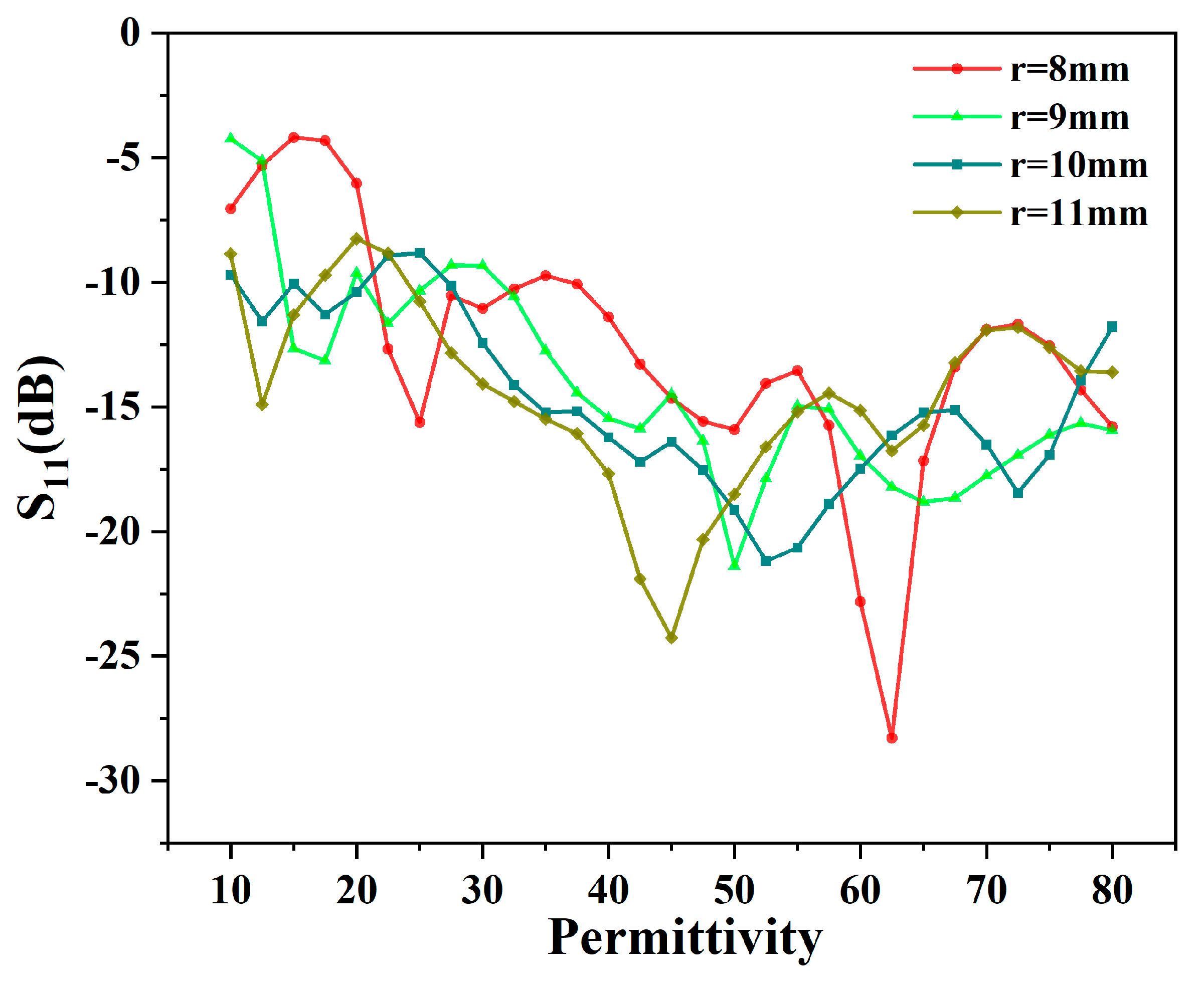

The radius of the helical liquid channel significantly affects the efficiency of this heating device. Simulations were conducted using COMSOL software to model different radius of the helical liquid channel. The channel radius varied from 8 to 11 mm in 1 mm increments, while maintaining a constant number of turns in the helical pipe, resulting in a fixed pitch of 25 mm. The operating frequency was set at 2.45 GHz with an input microwave power of 200 W. In the simulation analysis of the microwave device's S11 parameter, the initial temperature of the heated liquid was 293.15 K. The permittivity varied from 10 to 80 in steps of 2.5, with a loss tangent of 0.1. The simulation results for S11 under different size parameters are shown in

Figure 9.

The simulation results reveal that when the channel radius varies from 8 to 11 mm, the S11 of all models is less than -10 dB for most permittivity, indicating that the heating efficiency exceeds 90%. When the channel radius is 8, 9, or 11 mm, the S11 parameter is particularly high at some specific permittivity, resulting in very low heating efficiency. Conversely, when the channel radius is 10 mm, although the efficiency may fall below 90% at certain permittivity, it remains relatively high compared to other channel radius and shows good overall stability in efficiency. Therefore, the continuous microwave flow heating device with a channel radius of 10 mm is the preferred configuration and is the focus of further investigation in this study.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we developed a high-performance microwave heating device based on a coaxial structure to address the need for continuous-flow heating in chemical production. A multi-physics field model coupling electromagnetic fields, heat transfer, and laminar flow was established. An experimental system was set up to validate this physical field model. The experimental results generally aligned with the simulations, confirming the model's accuracy and validity. By studying the electric field distribution during water heating and the temperature field distribution at the liquid outlet after 60 seconds of heating, we demonstrated that the uniform sectional distribution of electric field in TEM mode achieved by the coaxial structure significantly improves heating uniformity. A robustness analysis of the proposed model was conducted. When the relative permittivity of the heated liquid ranged from 10 to 80, the device's heating efficiency exceeded 90% in most cases. The COV of the liquid outlet surface remained below , indicating excellent heating uniformity. Furthermore, the impact of channel radius on heating efficiency was investigated. The results showed that a channel radius of 10 mm provided the best stability in heating efficiency, which was the parameter adopted in this study. The proposed microwave continuous-flow device can efficiently and uniformly process continuous-flow liquids, exhibiting high heating performance. However, the proposed device remains at a laboratory scale, and the heating efficiency and uniformity require further investigation when scaling up.

Author Contributions

J. D. and W. X.: conceptualization, J. D.: methodology, F. Y. and G. L: software, W. X., H. Z. and Y. Y.: validation, H. Z.: formal analysis, G. L: investigation, Y. Y.: resources, J. D.: data curation, J. D.: writing—original draft preparation, W. X. and H. Z.: writing—review and editing, F. Y.: visualization, H. Z.: supervision, H. Z. and W. X.: project administration, H. Z. and W. X.: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the key project of Hefei city with grant number of 2022-SZD-004 and the Postdoctoral project of the State Key Laboratory of Efficient Utilization for Low Grade Phosphate Rock and Its Associated Resources of Wengfu Group with grant number of YF(2023)018.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baker-Fales, M.; Chen, T.-Y.; Vlachos, D.G. Scale-up of microwave-assisted, continuous flow, liquid phase reactors: Application to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural production. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 454, 139985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Xia, S.; Ho, C.-T. Rapid preparation of the Amadori rearrangement product of glutamic acid - xylose through intermittent microwave heating and its browning formation potential in microwave thermal processing. Food Research International 2024, 181, 114075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, M.T.K.; dos Reis, B.H.G.; Sato, L.N.I.; Gut, J.A.W. Microwave and conventional thermal processing of soymilk: Inactivation kinetics of lipoxygenase and trypsin inhibitors activity. LWT 2021, 145, 111275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapivnitckaia, T.; Ananicheva, S.; Alyeva, A.; Denisenko, A.; Glyavin, M.; Peskov, N.; Vikharev, A.; Sachkova, A.; Zelentsov, S.; Shulaev, N. Theoretical and Experimental Demonstration of Advantages of Microwave Peat Processing in Comparison with Thermal Exposure during Pyrolysis. Processes 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kou, J.; Sun, C. A comparative study of the thermal decomposition of pyrite under microwave and conventional heating with different temperatures. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2019, 138, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Q. Continuous-Flow Microwave Milk Sterilisation System Based on a Coaxial Slot Radiator. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, K.C.; Russo, G.; Fan, D.L.; Gut, J.A.W.; Tadini, C.C. Modeling and experimental validation of the time-temperature profile, pectin methylesterase inactivation, and ascorbic acid degradation during the continuous flow microwave-assisted pasteurization of orange juice. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2024, 144, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.N.; You, K.Y.; Chong, C.Y.; El-Enshasy, H.A.; Mohamed Ali, M.S.; Zainol, N.A.; Ismael, A.H.; Khe, C.S. Optimisation of heating uniformity for milk pasteurisation using microwave coaxial slot applicator system. Biosystems Engineering 2022, 215, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Song, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Ma, C. Microwave pyrolysis of corn stalk bale: A promising method for direct utilization of large-sized biomass and syngas production. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2010, 89, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccioli, O.; Meloni, E.; Renda, S.; Martino, M.; Brandani, F.; Pullumbi, P.; Palma, V. NiCoAl-Based Monolithic Catalysts for the N2O Intensified Decomposition: A New Path towards the Microwave-Assisted Catalysis. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kodgire, P.; Kachhwaha, S.S. Biodiesel production from waste cotton-seed cooking oil using microwave-assisted transesterification: Optimization and kinetic modeling. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 116, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, C.A.; Marzoughi, O.; Hutcheon, R.M. Temperature and frequency dependencies of the permittivities of selected pyrometallurgical reaction mixtures. Minerals Engineering 2023, 201, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; He, Z.; Tang, R.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, C. The Research on Microwave Drying Characteristics of Polyethylene Terephthalate Materials Based on Frequency and Power Tuning Technology. Processes 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, H. High-efficiency and compact microwave heating system for liquid in a mug. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2023, 51, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, O.; Topcam, H.; Altin, O.; Erdogdu, F. Computational study for microwave pasteurization of beer and hypothetical continuous flow system design. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2022, 75, 102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yan, B.; Chen, W.; Fan, D. Prediction and innovation of sustainable continuous flow microwave processing based on numerical simulations: A systematic review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 175, 113183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, K. High-Efficiency Continuous-Flow Microwave Heating System Based on Asymmetric Propagation Waveguide. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2022, 70, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Xiouras, C.; Stefanidis, G.D.; Li, X.; Gao, X. Fundamentals and applications of microwave heating to chemicals separation processes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 114, 109316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendres, A.; Chemat, F.; Maingonnat, J.-F.; Renard, C.M.G.C. An innovative process for extraction of fruit juice using microwave heating. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-P.; Amesho, K.T.T.; Chen, C.-E.; Jhang, S.-R.; Chou, F.-C.; Lin, Y.-C. Optimization of Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil Using Waste Eggshell as a Base Catalyst under a Microwave Heating System. Catalysts 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, M.-C.; Kuo, J.-Y.; Hsieh, S.-A.; Hsieh, P.-H.; Hou, S.-S. Optimized conversion of waste cooking oil to biodiesel using modified calcium oxide as catalyst via a microwave heating system. Fuel 2020, 266, 117114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.K.; Ngoh, G.C.; Yusoff, R.; Aroua, M.K. Microwave-assisted transesterification of industrial grade crude glycerol for the production of glycerol carbonate. Chemical Engineering Journal 2016, 284, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H. Dielectric Loss Mechanism in Electromagnetic Wave Absorbing Materials. Advanced Science 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.; Wu, Y.; Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Lan, J.; Zhu, H. Device Testing: High-Efficiency and High-Uniformity Microwave Water Treatment System Based on Horn Antennas. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocreto, J.B.; Chen, W.-H.; Ubando, A.T.; Park, Y.-K.; Sharma, A.K.; Ashokkumar, V.; Ok, Y.S.; Kwon, E.E.; Rollon, A.P.; De Luna, M.D.G. A critical review on second- and third-generation bioethanol production using microwaved-assisted heating (MAH) pretreatment. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 152, 111679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altin, O.; Skipnes, D.; Skåra, T.; Erdogdu, F. A computational study for the effects of sample movement and cavity geometry in industrial scale continuous microwave systems during heating and thawing processes. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2022, 77, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Yan, B.; Zhu, H.; Gao, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Fan, D. Continuous flow microwave system with helical tubes for liquid food heating. Journal of Food Engineering 2021, 294, 110409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campañone, L.A.; Zaritzky, N.E. Mathematical analysis of microwave heating process. Journal of Food Engineering 2005, 69, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, D.; Ortego, J.; Arauz, C.; Sabliov, C.M.; Boldor, D. Experimental study of the effect of dielectric and physical properties on temperature distribution in fluids during continuous flow microwave heating. Journal of Food Engineering 2009, 93, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, X.; Han, D.; Peng, R.; Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, W. A High-Efficiency Single-Mode Traveling Wave Reactor for Continuous Flow Processing. Processes 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Su, J.; Chen, H.; Ye, J.; Qin, K.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, H. Continuous-flow microwave heating system with high efficiency and uniformity for liquid food. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2024, 91, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapranov, S.V.; Kouzaev, G.A. Study of microwave heating of reference liquids in a coaxial waveguide reactor using the experimental, semi-analytical and numerical means. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2019, 140, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Saleem, Q.; Şaş, H.S.; Bayazıt, M.K. Numerical investigation of heat transfer and temperature distribution in a Microwave-Heated Heli-Flow reactor and experimental validation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 488, 150914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, K.; Vijaya Raghavan, G.S. Dynamic analysis of a continuous-flow microwave-assisted screw propeller system for biodiesel production. Chemical Engineering Science 2019, 202, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Shu, W.; Xu, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, K.; Ye, J. Novel electromagnetic-black-hole-based high-efficiency single-mode microwave liquid-phase food heating system. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2022, 78, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, W.; Wu, X. Frequency- and temperature-dependent dielectric properties of fruit juices associated with pasteurization by dielectric heating. Journal of Food Engineering 2012, 109, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).