Submitted:

19 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Evaluation Indicators for the Resilience of Rail Transit Networks Under Flood Conditions

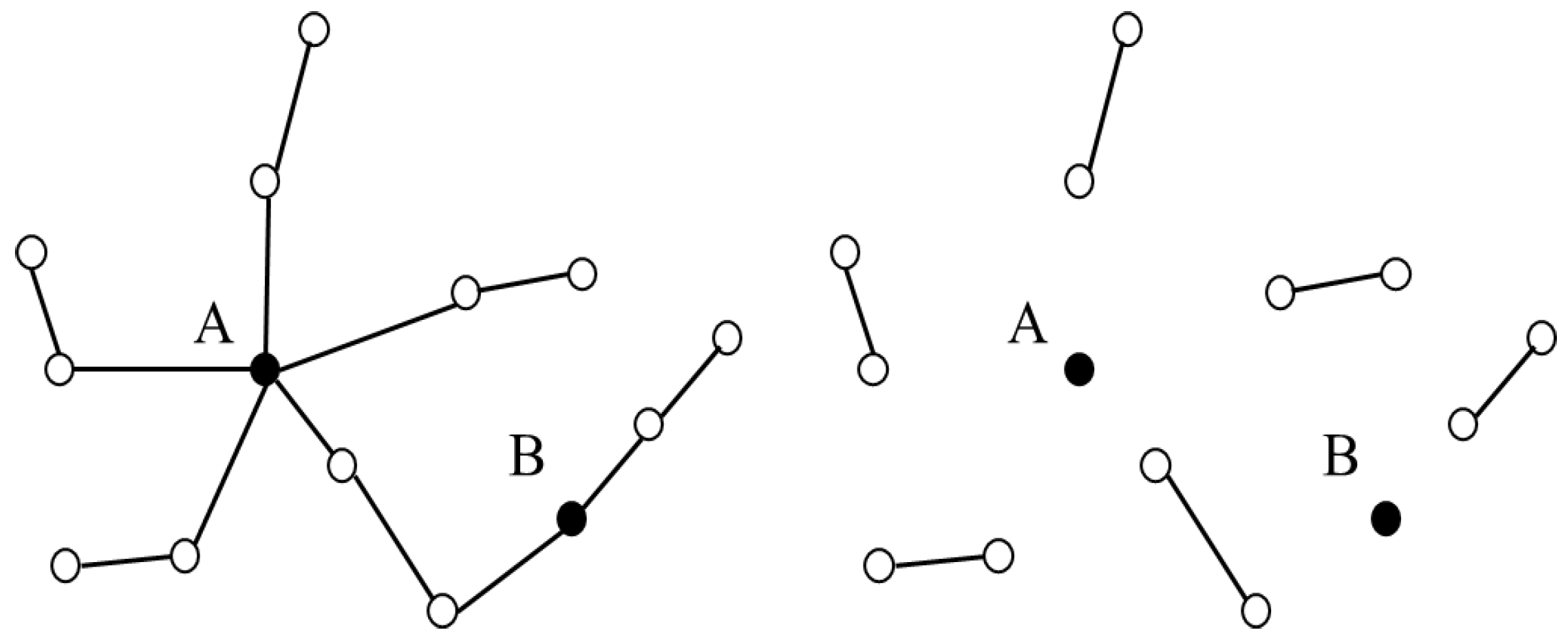

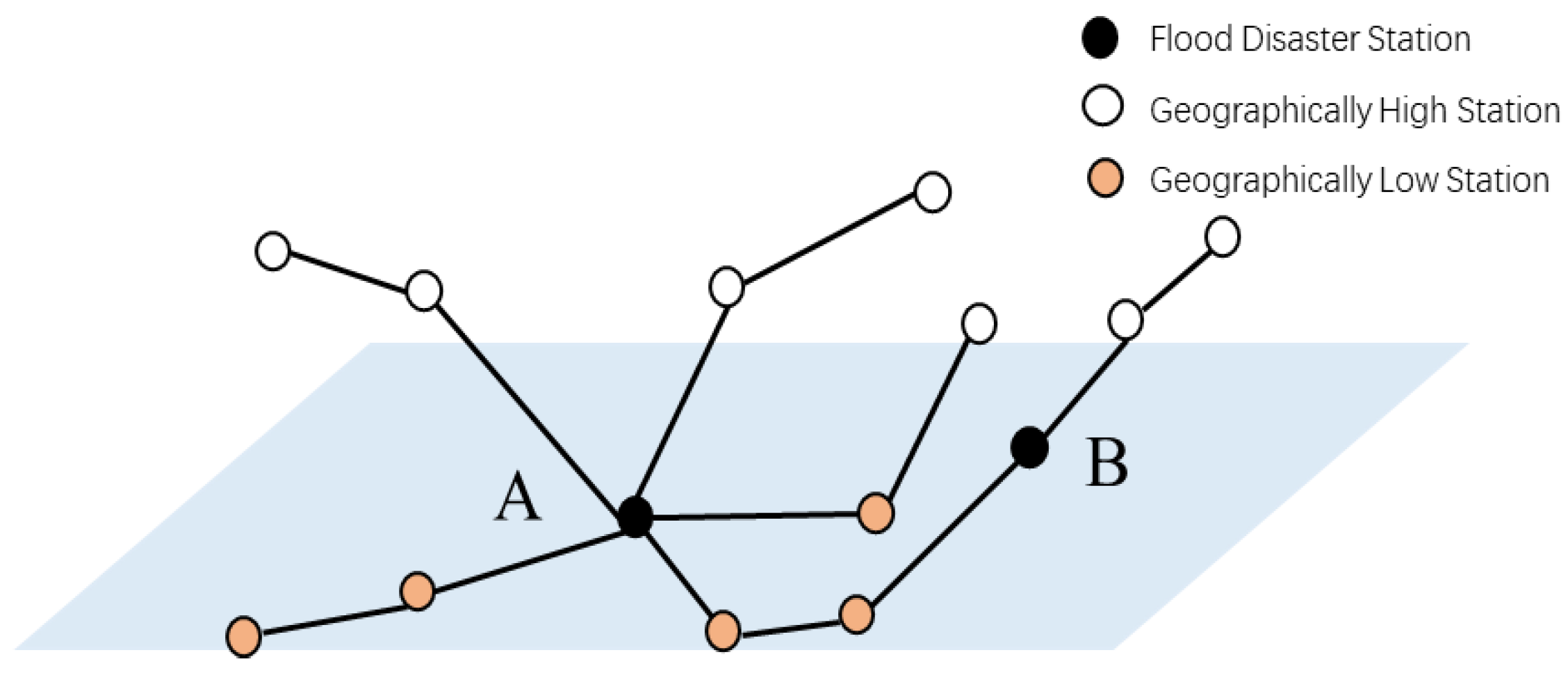

2.1. Rail Transit Network Characteristics

2.2. Geographic Information of Stations

2.3. Stations Dynamic Characteristics of Passenger Flow

3. Modeling and Analysis of Cascading Failures in Rail Transit Networks Based on CML

3.1. Coupled Map Lattice (CML)

3.2. Spatiotemporal State of Network Stations Under Different Conditions

3.3. Resilience Algorithm Process for Cascading Failures in Rail Transit Based on CML

4. Results Cascading Failure Process and Resilience Analysis of the Shanghai Rail Transit Network Under Flood Conditions

4.1. Data Source

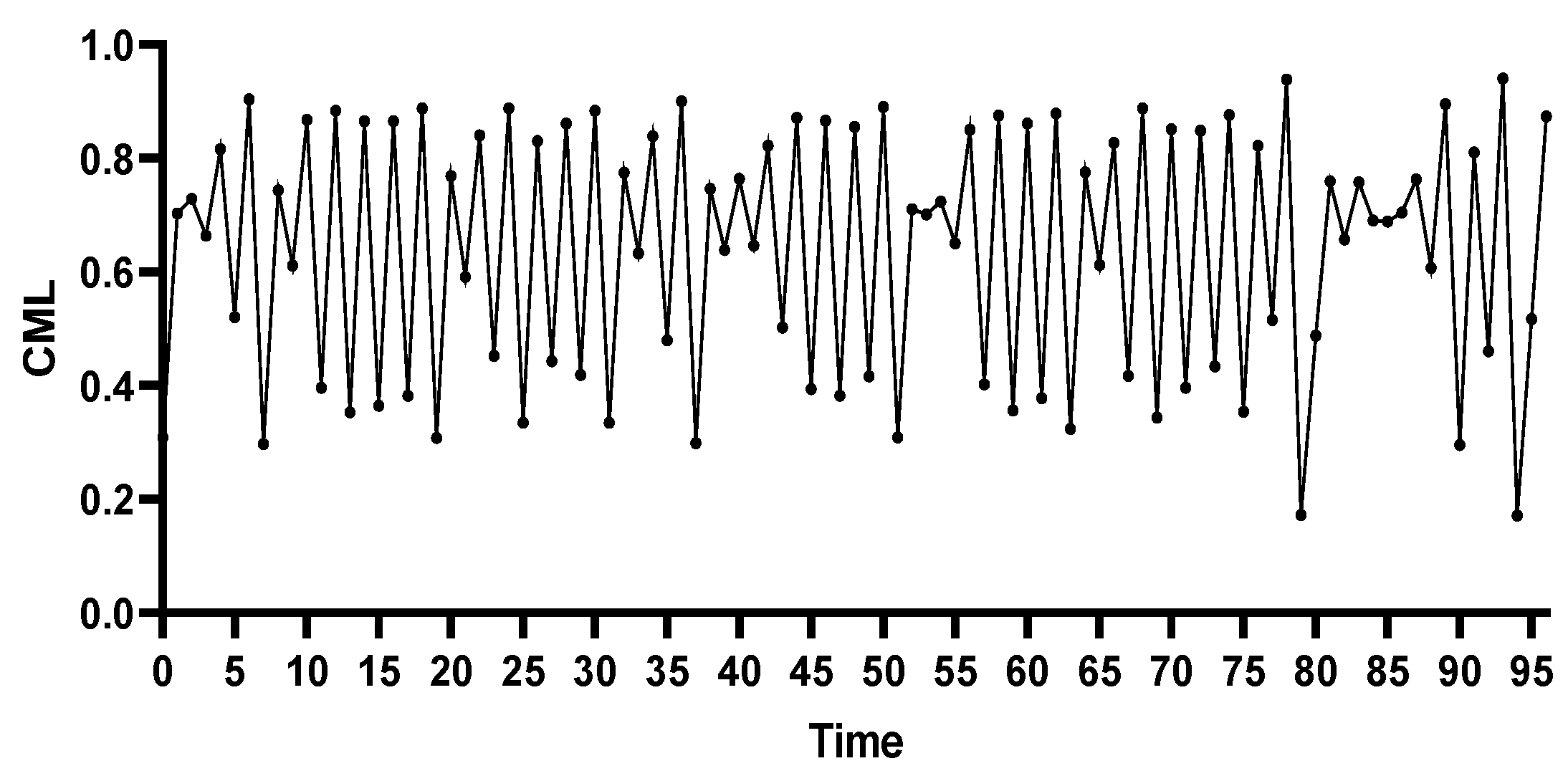

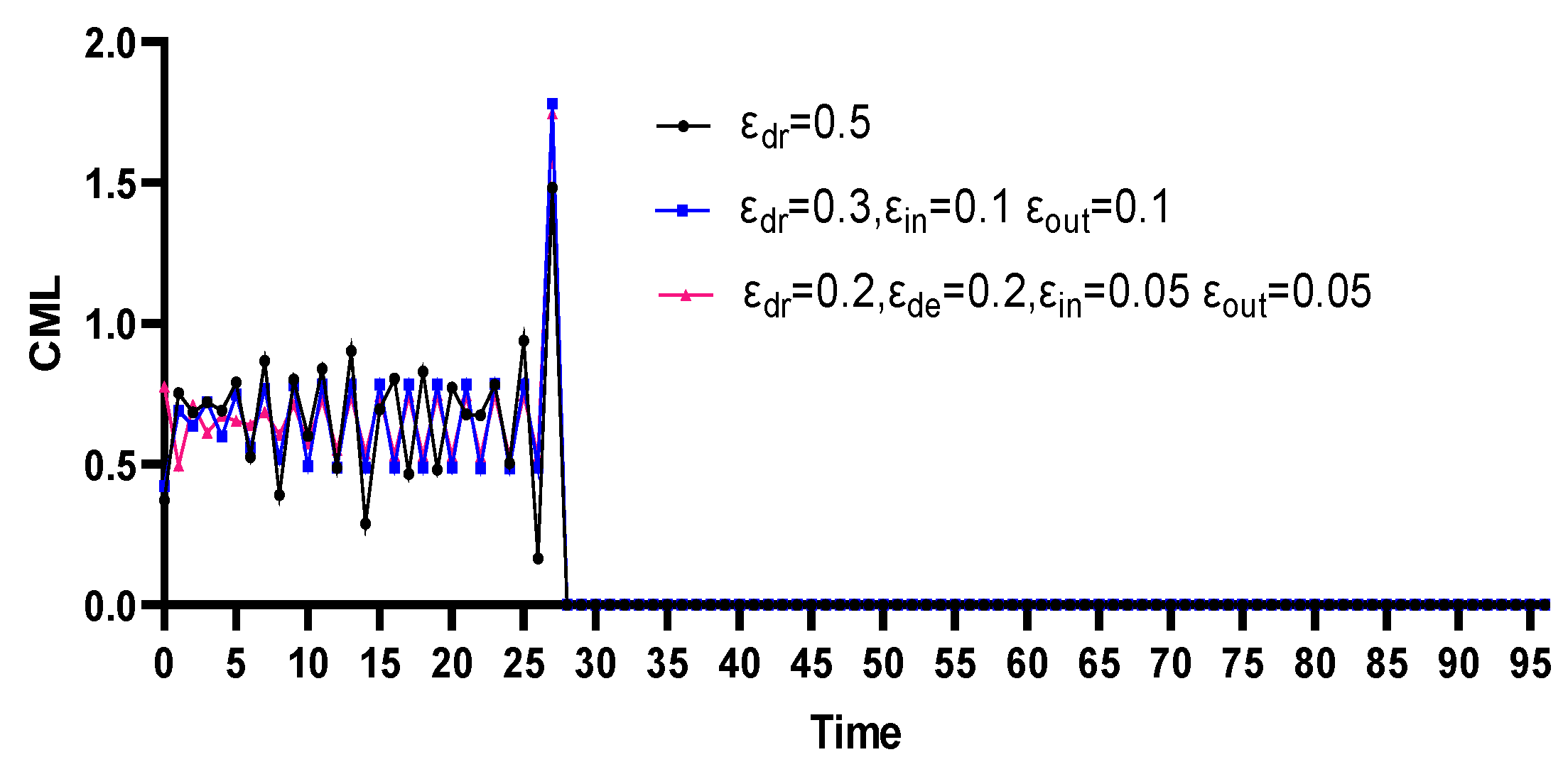

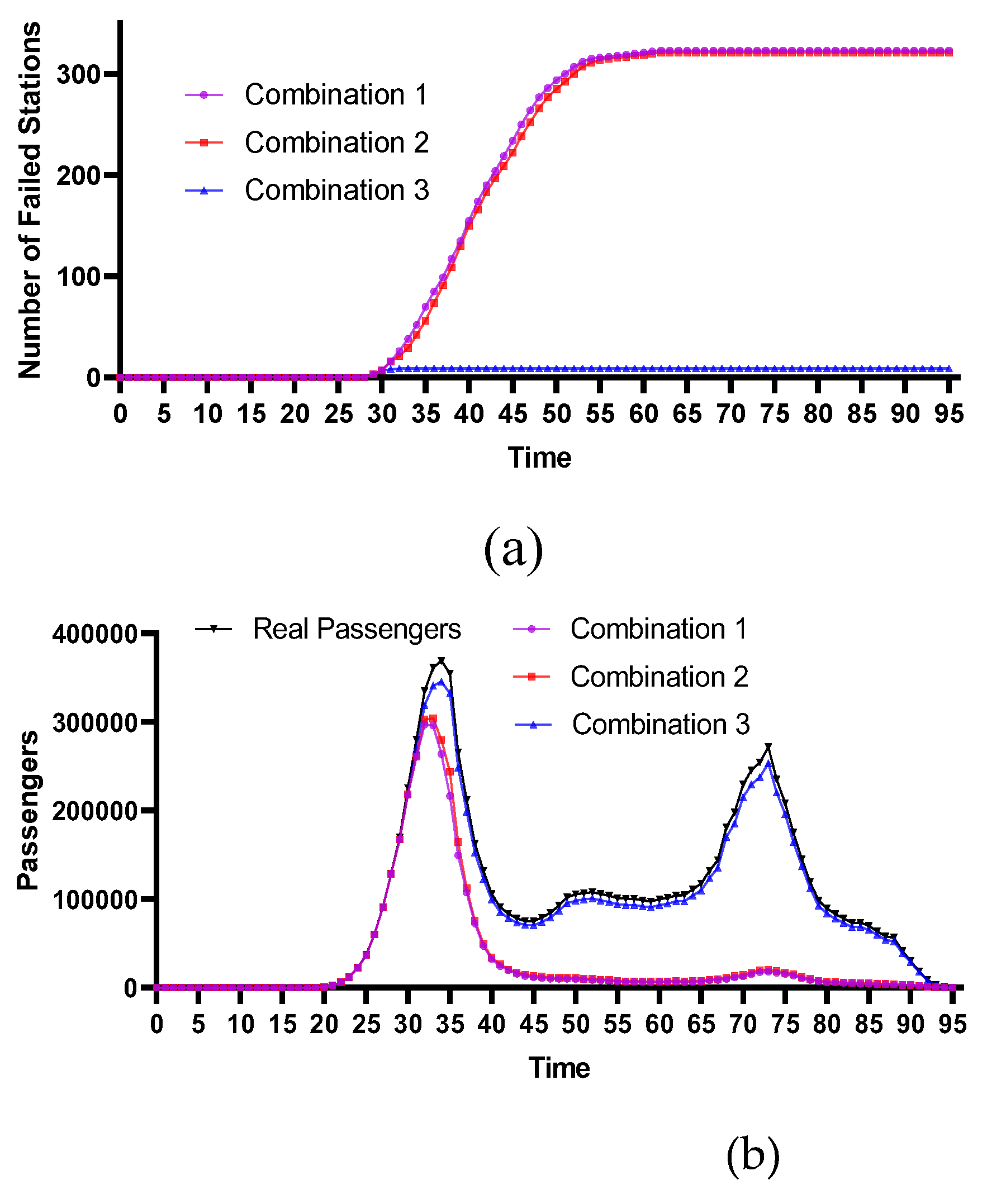

4.2. Analysis of Stepwise Weighted Resilience Changes During the Cascading Failure Process of the Rail Transit Network Under Flood Conditions

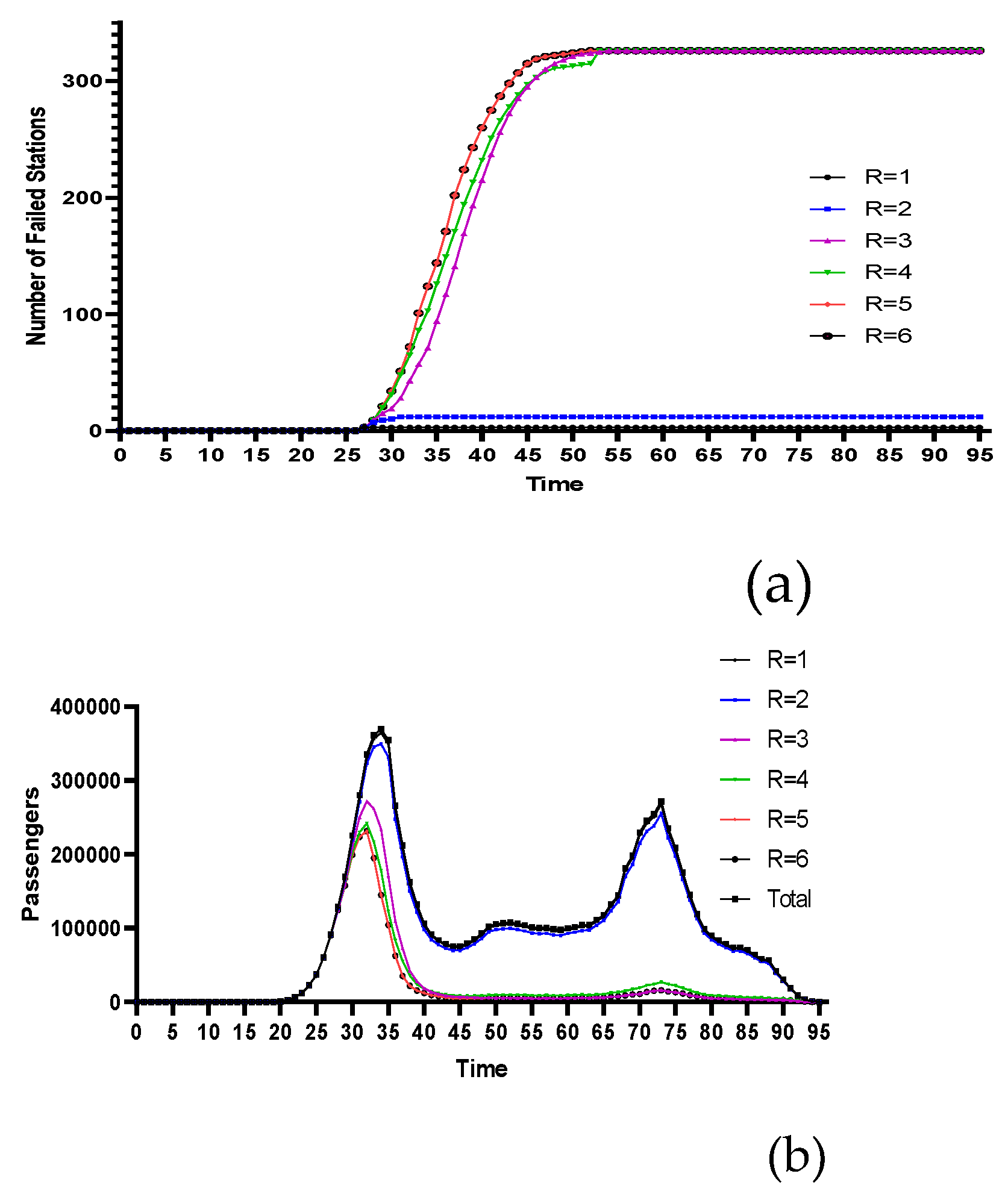

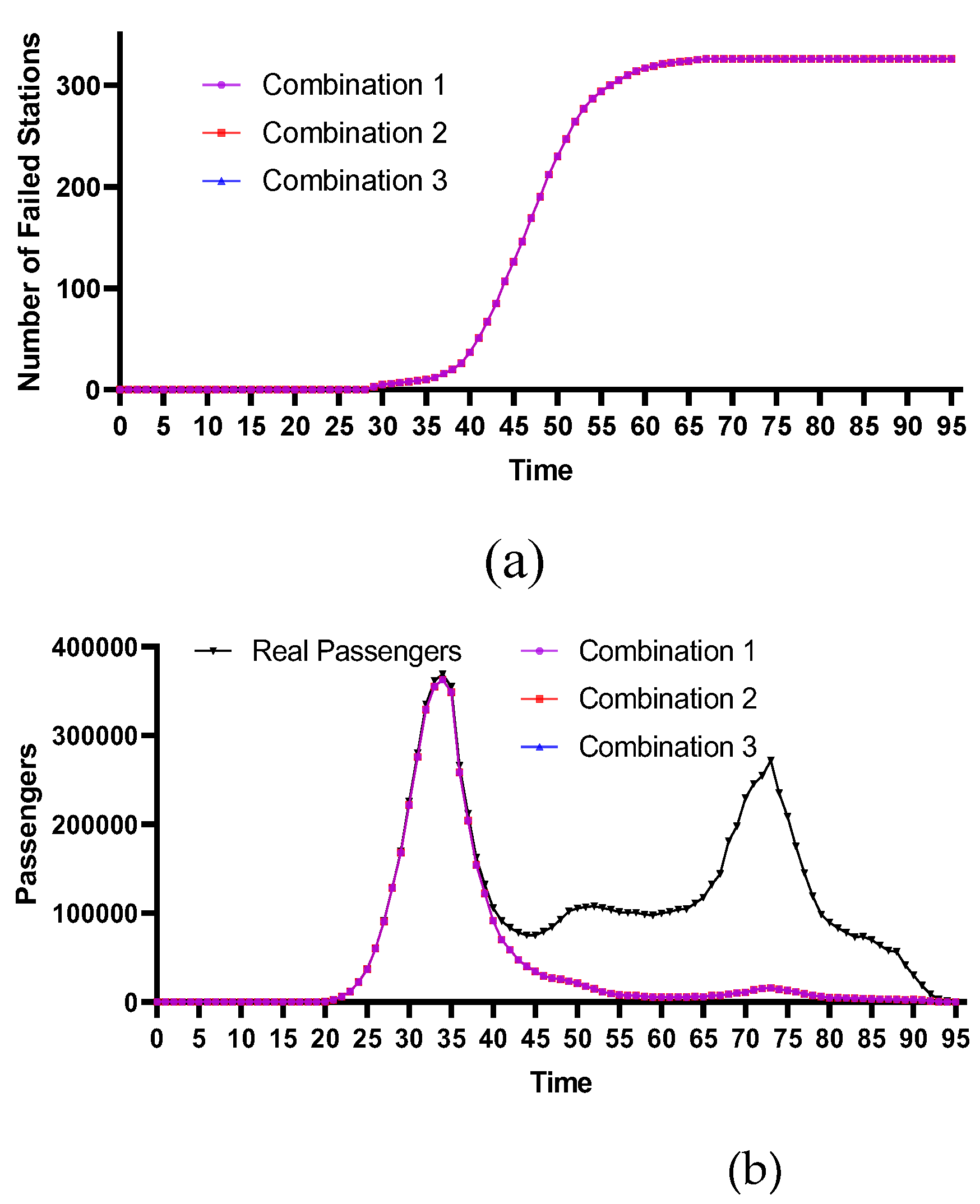

4.2.1. Stations with the Highest Degree Centrality

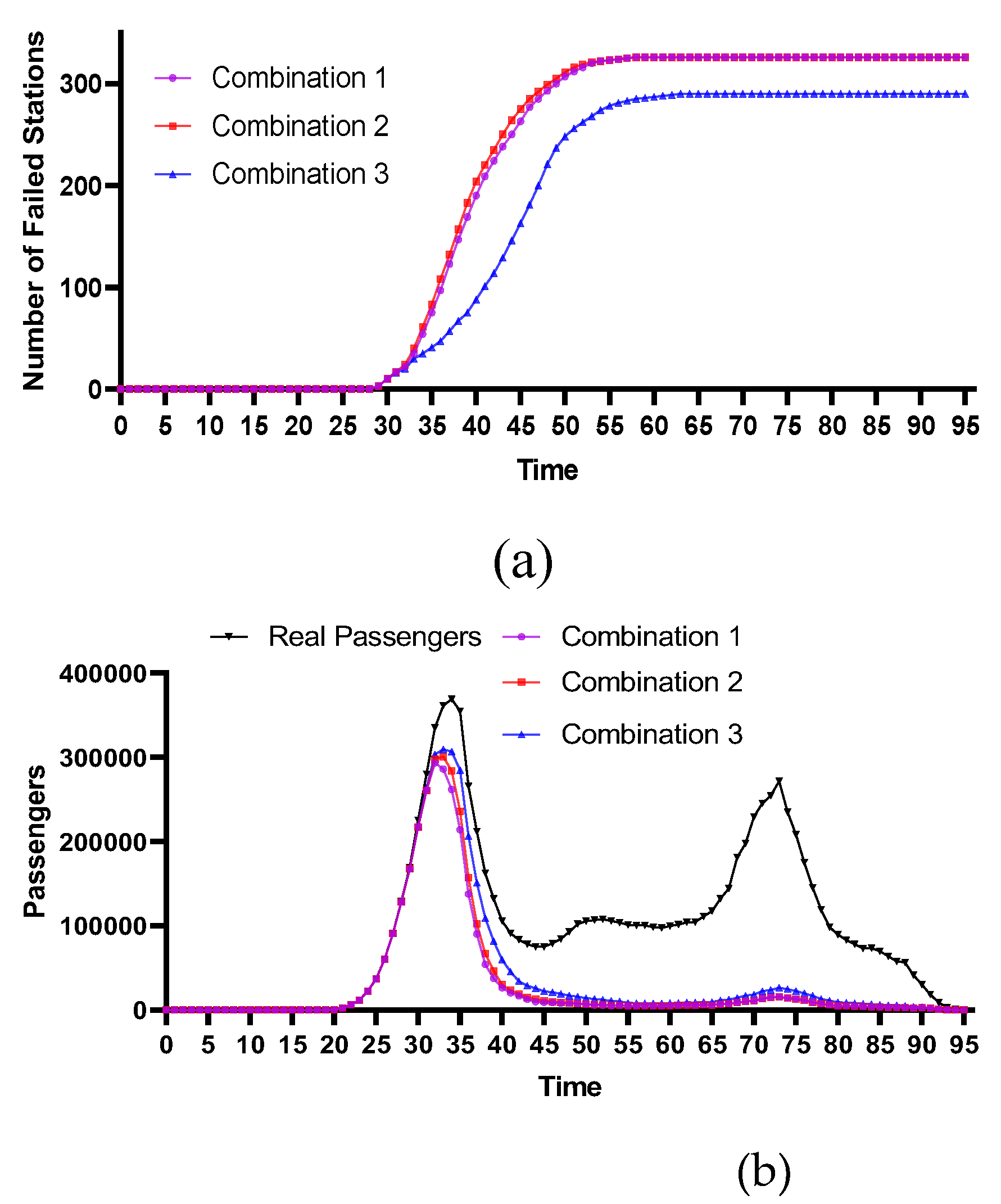

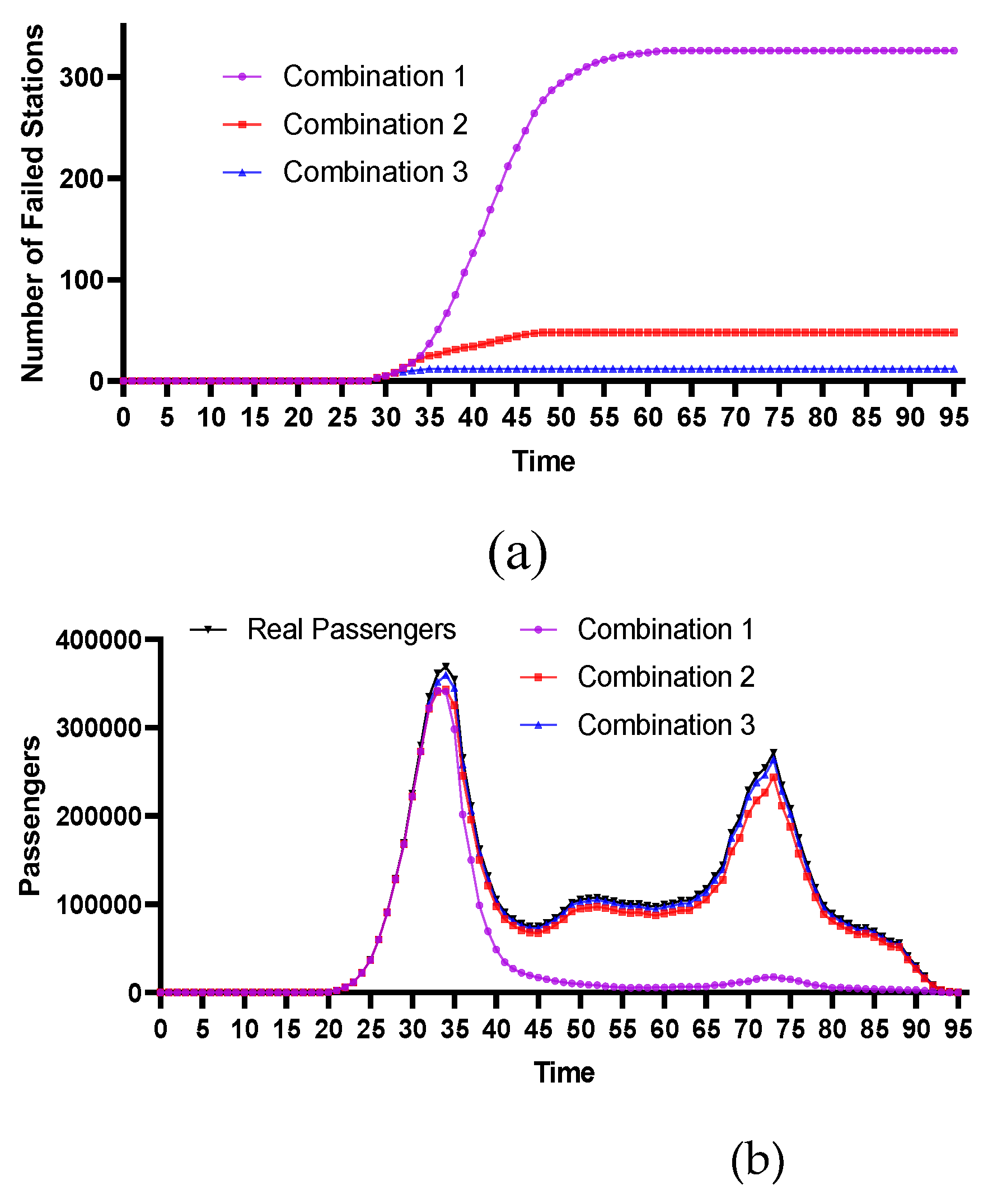

4.2.2. Centrality Stations with Lower Geographical Positions

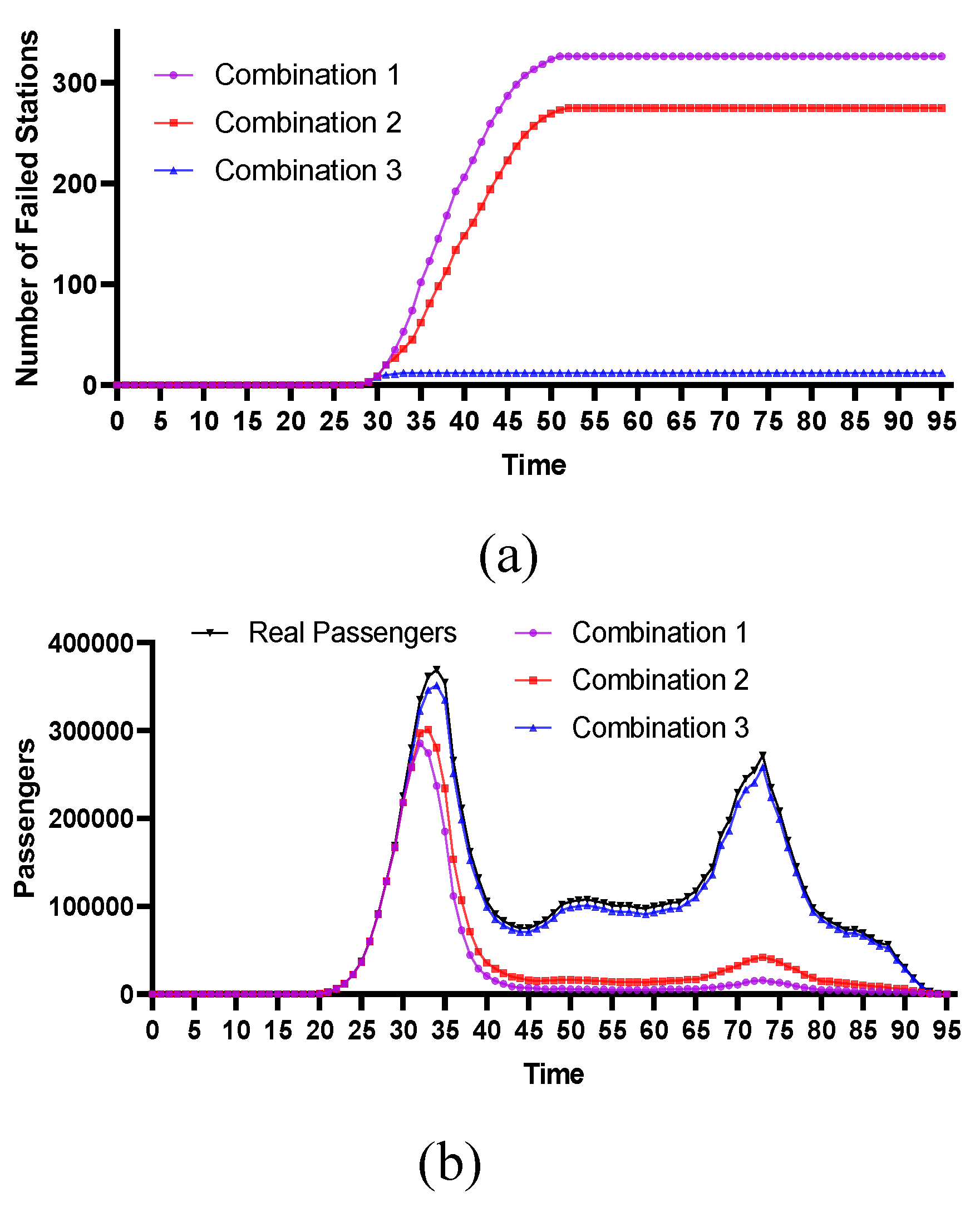

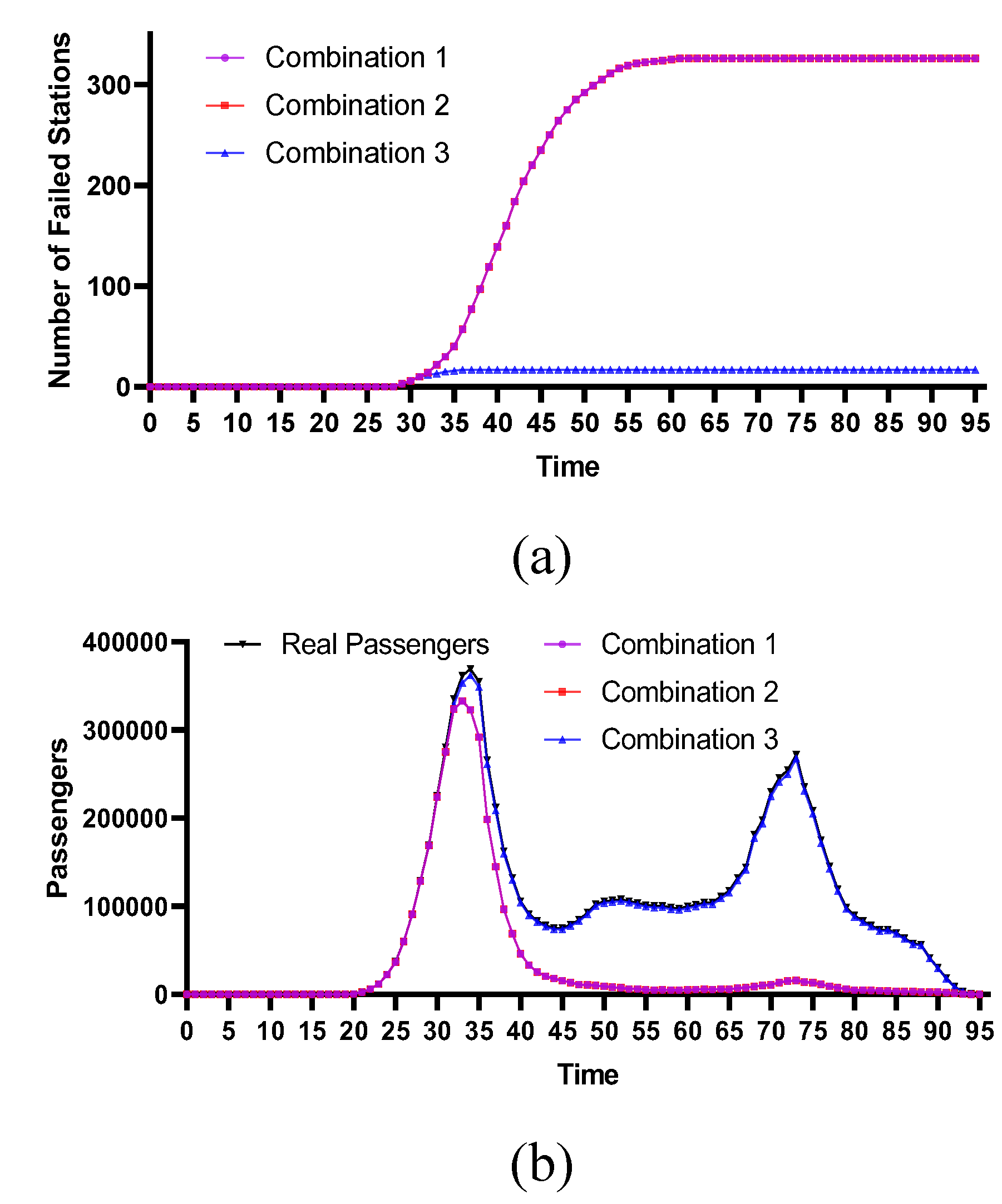

4.2.3. Historical Flood-Prone Stations

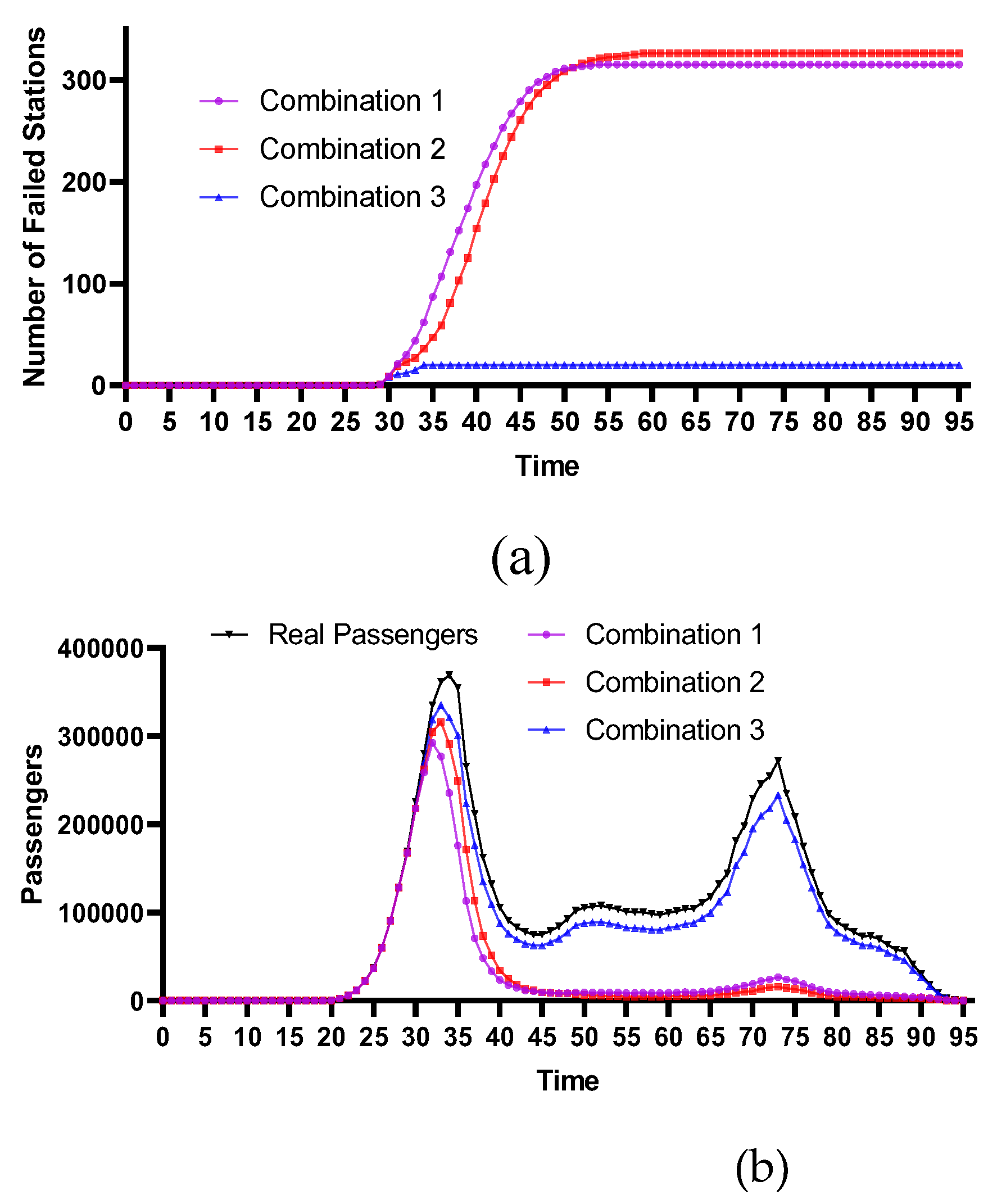

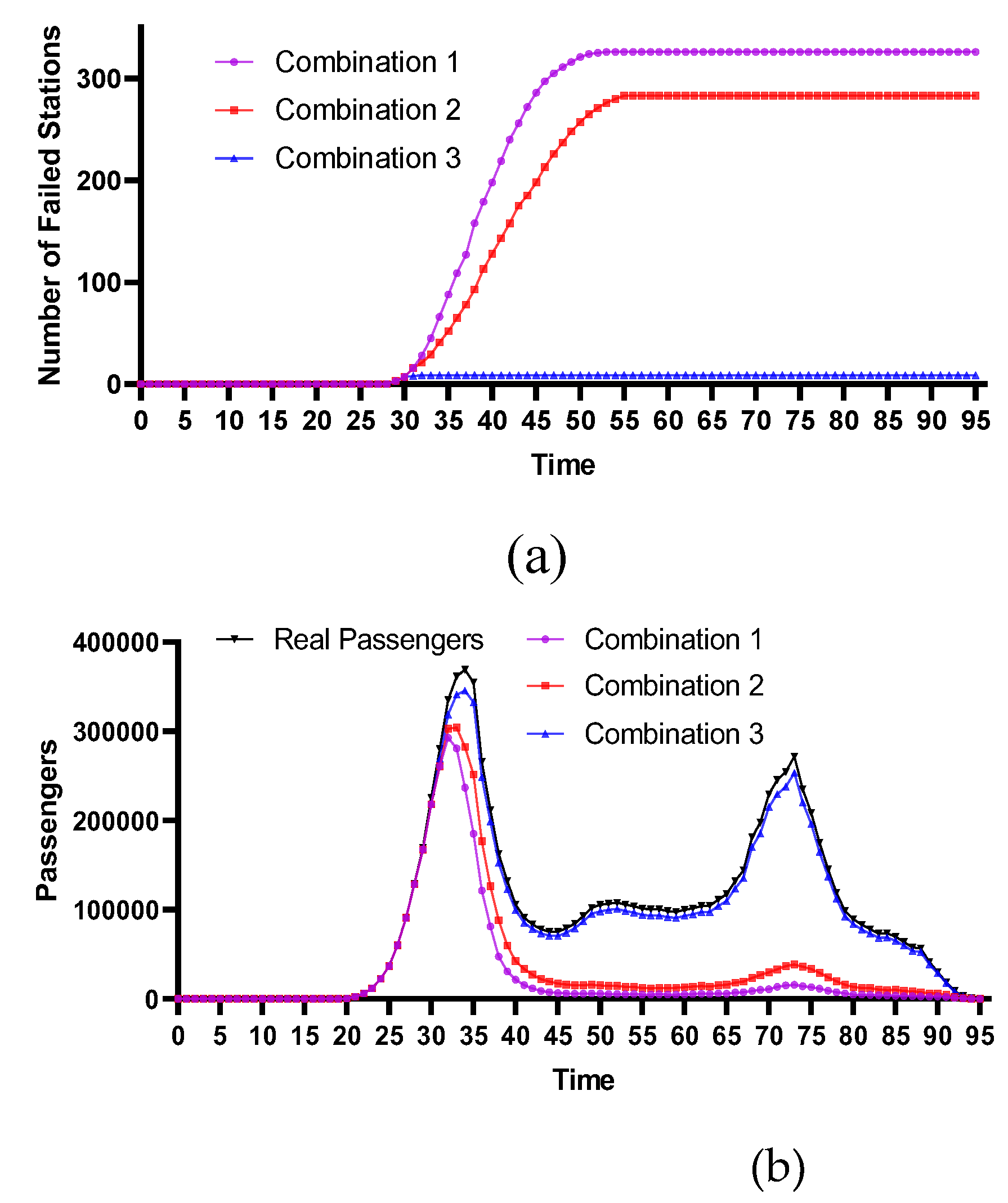

4.2.4. Comparative Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, X.; Qin, Y.; Gao, X. Interpretation of the main conclusions and suggestions of IPCC AR6 working group Ⅰ report. Environmental Protection 2021, 49, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G.; Ahn, J.E. A systematic review: To increase transportation infrastructure resilience to flooding events. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, K.; Yang, Z.; Lai, X.; Teng, J. Method for identifying the emergency points of urban transit networks in rainstorms with road waterlogging. Journal of Transportation Engineering and Information 2021, 20, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Liu, L.Y. Flood risk assessment of subway systems in metropolitan areas under land subsidence scenario: a case study of beijing. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ou-Yang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Yang, Q.; Liu, B.; Xi, Y. Urban rail transit disaster chain evolution network model and its risk analysis —taking subway flood as an example. Railway Standard Design 2020, 64, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, S.; Stanley, H.E.; Gao, J. Local floods induce large-scale abrupt failures of road networks. Nature Communications 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Yin, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C. Network representation learning: A survey. IEEE transactions on Big Data 2018, 6, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Huang, W.; Shuai, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Structural characteristics analysis and cascading failure impact analysis of urban rail transit network: From the perspective of multi-layer network. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2022, 218, 108161. [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Huang, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, F. Analysis of characteristics of complex network and robustness in Shanghai metro network. Engineering Journal of Wuhan University 2016, 049, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, R. Analysis on characteristics of urban rail transit network and robustness of cascading failure. Computer Engineering and Applications 2022, 58, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shuai, B.; Liu, Y. Cascading failure mechanism of urban rail transit network. China Transportation Review 2020, 42, 69-74+120.

- Hu, J.; Yang, M.; Zhen, Y. A review of resilience assessment and recovery strategies of urban rail transit networks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, M.; Han, H.; Mahran, M.G.N.; Abdrabo, K.I.; Yousry, A. Revisiting urban resilience: a systematic review of multiple-scale urban form indicators in flood resilience assessment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nima; Dehmamy; Soodabeh; Milanlouei; Albert-László; Barabási. A structural transition in physical networks. Nature 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, P. Cascading failures in weighted network of urban rail transit. Journal of Transportation Systems Engineering and Information Technology 2016, 16, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Q.; Lu, W. Cascading Failure resistance of urban rail transit network. Journal of Transportation Systems Engineering and Information Technology 2018, 18, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Wu, X.; Guan, W.; Duan, M. Evolution of metro network stability based on weighted coupled map lattice. Journal of Transportation Systems Engineering and Information Technology 2021, 21, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, X. Reliability analysis of urban rail transit system network based on coupled map lattice model. Journal of University of Shanghai for Science and Technology 2021, 43, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Luo, X. Cascading failure analysis on shanghai metro networks: an improved coupled map lattices model based on graph attention networks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 19, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H. Cascading failure analysis of urban rail transit network based on coupled map lattice model. In CICTP 2020; 2020; pp. 2074-2084.

- Shen, Y.; Ren, G.; Ran, B. Cascading failure analysis and robustness optimization of metro networks based on coupled map lattices: a case study of Nanjing, China. Transportation 2019, 48, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, G.; Zuo, B.; Wang, J.; Song, S. Simulation of urban rainstorm waterlogging process based on SWMM and LISFLOOD-FP models - Case study in Jinan City. South-to-North Water Transfers and Water Science & Technology 2021, 19, 1083-1092. [CrossRef]

| Station Characteristics |

Order of Station Failures |

Order of Passenger Flow Impact |

Order of Cascading Failure Speed |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station No. | Degree | Deep | C 1 | C 2 | C 3 | C 1 | C 2 | C 3 | C 1 | C 2 | C 3 |

| 41 | 7 | 0.96 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 19 | 6 | 0.96 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 45 | 6 | 0.93 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| 159 | 4 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 |

| 164 | 4 | 0.99 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 6 |

| 189 | 4 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| 48 | 4 | 0.87 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 8 |

| 104 | 4 | 0.71 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 2 |

| 197 | 4 | 0.98 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).