Submitted:

19 August 2024

Posted:

19 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of the SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies

2.2. SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 (Pirola), JN.1 and EG.5 (Eris) Variants Sequence Retrieval, Modifications, and Modeling

2.3. NAb/SARS-CoV-2 RBD Reference Models’ Selection and Modification

2.4. RBD/S309 Complexes Construction

2.5. Complex Binding Affinity Analysis

2.6. RBD 3D Model Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 (Pirola), JN.1 and EG.5 (Eris) Variants

3. Results

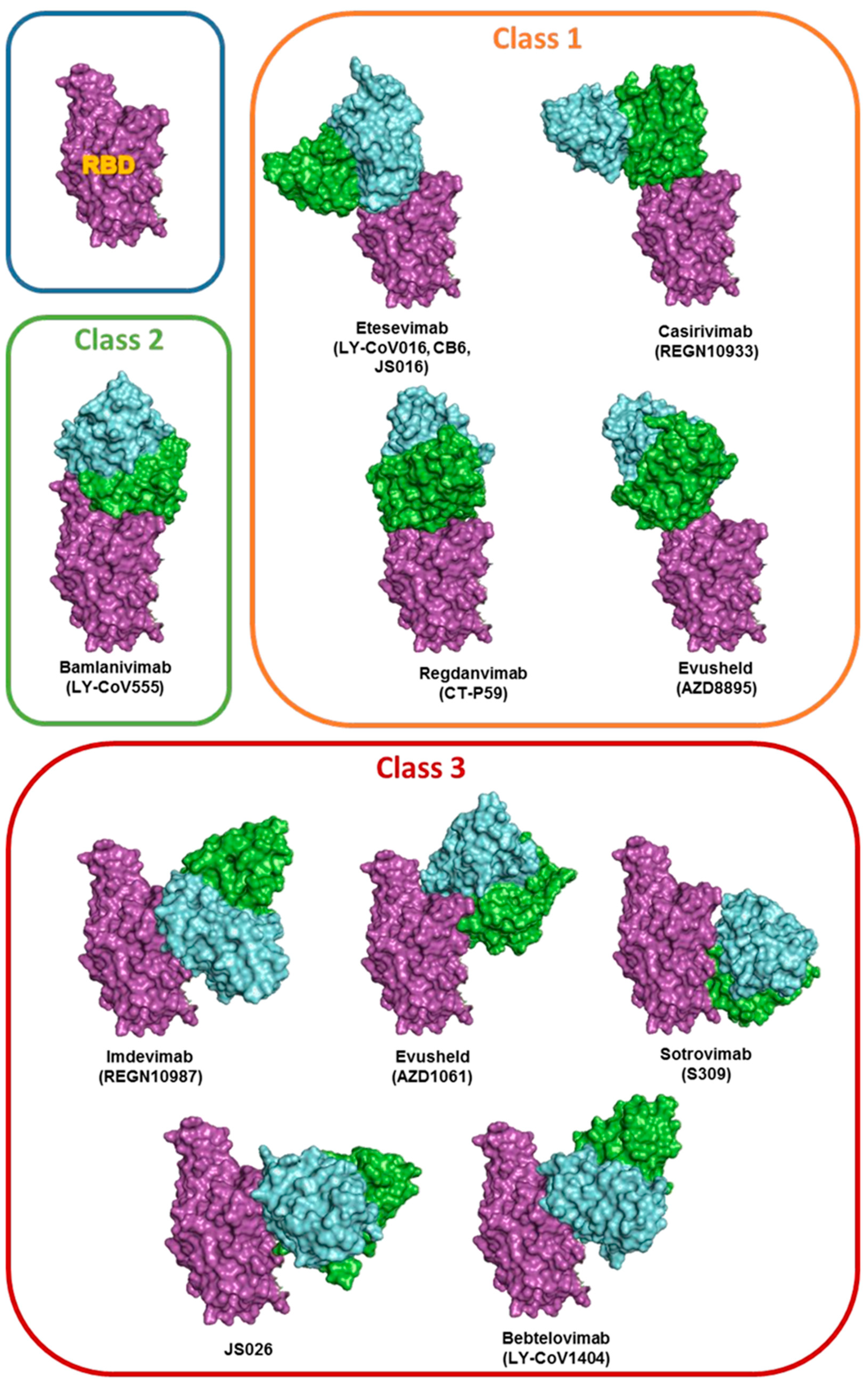

3.1. Antibodies Selection

3.2. Models’ Generation

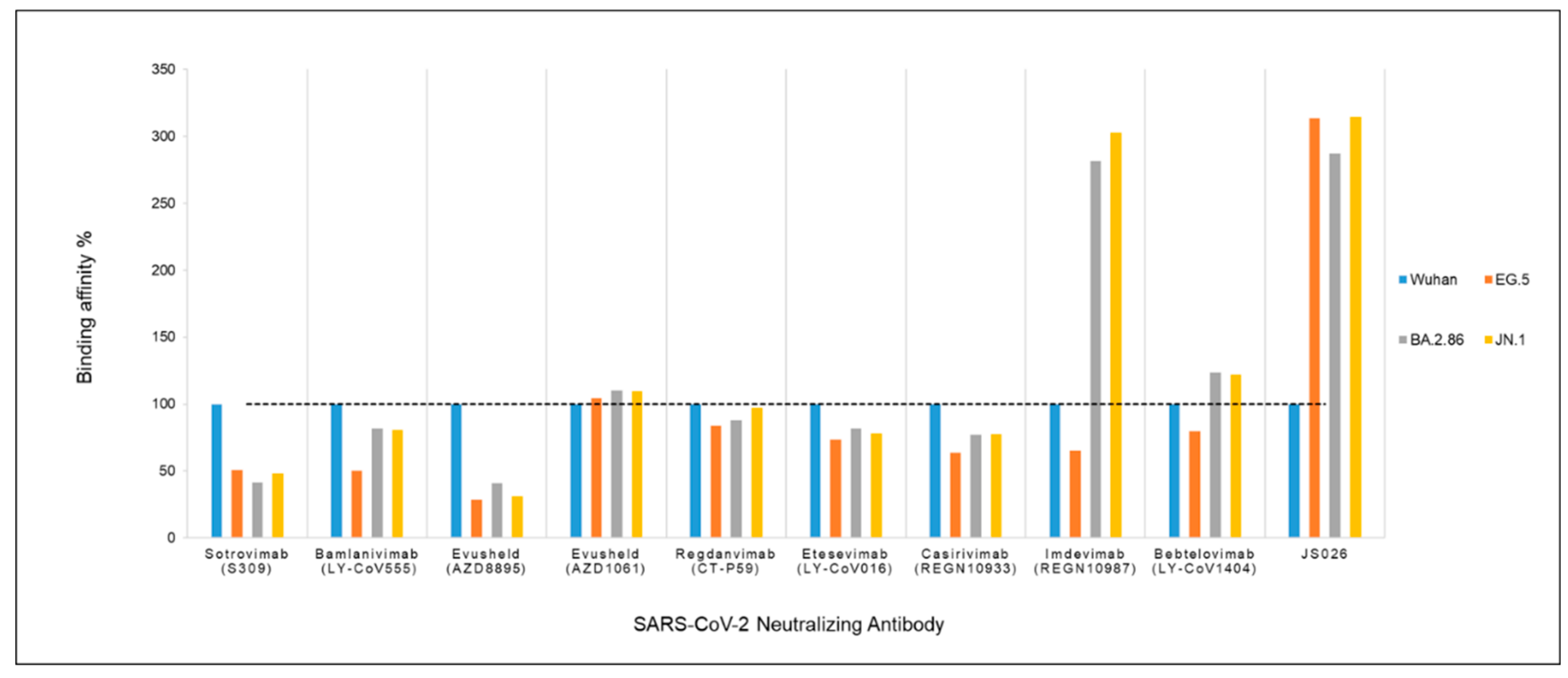

3.3. Binding Affinity Analysis

3.4. Analysis of Imdevimab and JS026 Molecular Interactions with the RBD Domain of the New Variants EG.5 and BA.2.86

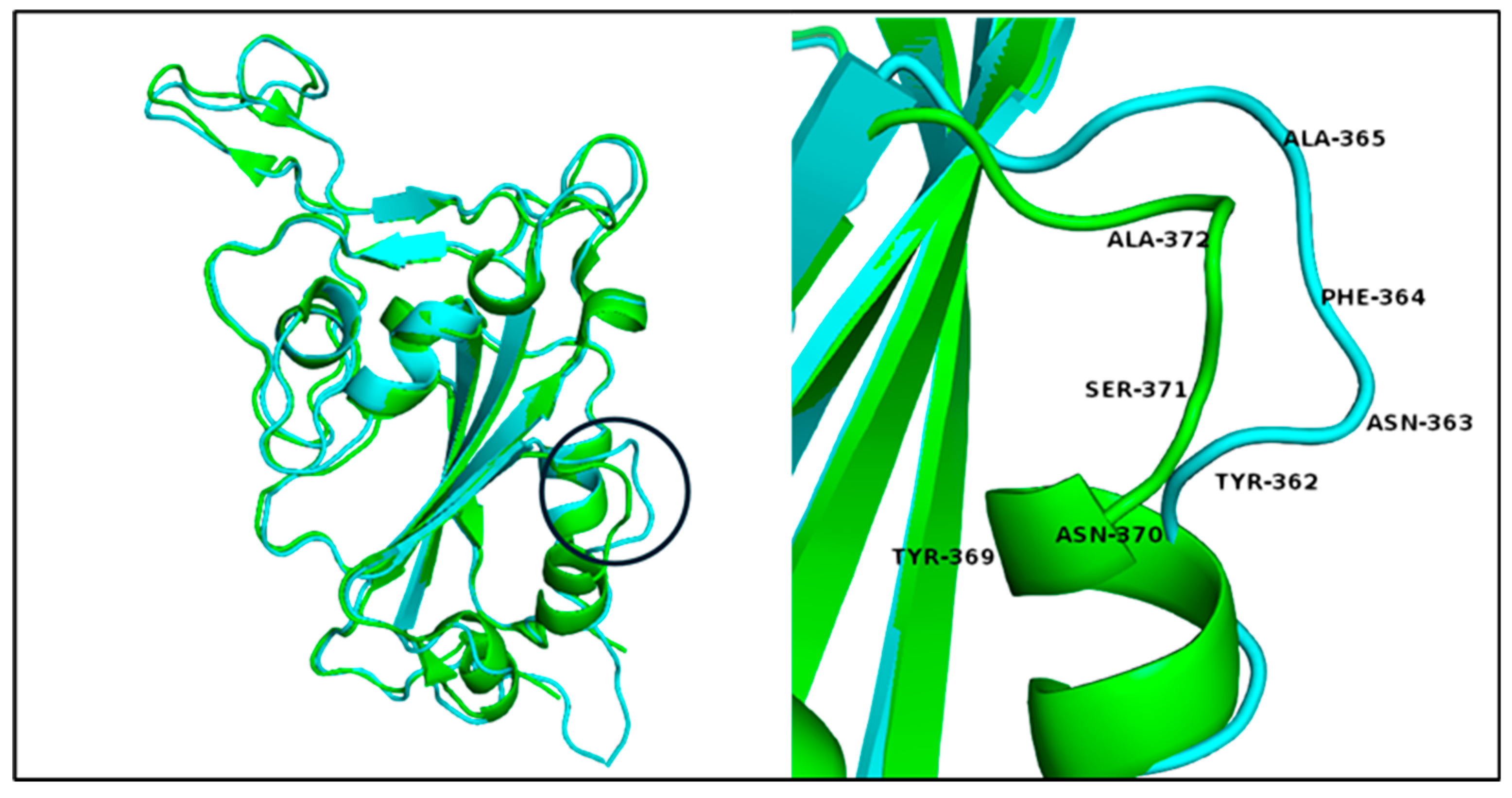

3.5. Variants’ 3D RBD Model Alignment and Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Antibody | Wuhan ΔG | EG.5 ΔG | BA.2.86 (Pirola) ΔG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sotrovimab (S309) |

-7.05 | -3.58 | -2.93 |

| Bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) |

-16.15 | -8.14 | -13.15 |

| Evusheld (AZD8895) |

-9.58 | -2.71 | -3.93 |

| Evusheld (AZD1061) |

-10.84 | -11.32 | -11.91 |

| Regdanvimab (CT-P59) |

-15.05 | -12.62 | -13.22 |

| Etesevimab (LY-CoV016) |

-15.9 | -11.67 | -13 |

| Casirivimab (REGN10933) |

-14.31 | -9.11 | -11.03 |

| Imdevimab (REGN10987) |

-4.51 | -2.95 | -12.69 |

| Bebtelovimab (LY-CoV1404) |

-9.87 | -7.84 | -12.2 |

| JS026 | -2.64 | -8.27 | -7.58 |

References

- Casadevall, A.; Dadachova, E.; Pirofski, L.-a. Passive antibody therapy for infectious diseases. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2004, 2, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.C.; Adams, A.C.; Hufford, M.M.; De La Torre, I.; Winthrop, K.; Gottlieb, R.L. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for treatment of COVID-19. Nature Reviews Immunology 2021, 21, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Jiang, J.; He, M.; Zheng, Z.; Yu, H.; Li, T.; Xue, W.; Tang, Z.; Ying, D.; Li, Z. Viral neutralization by antibody-imposed physical disruption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 26933–26940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, A.; Muecksch, F.; Lorenzi, J.C.C.; Leist, S.R.; Cipolla, M.; Bournazos, S.; Schmidt, F.; Maison, R.M.; Gazumyan, A.; Martinez, D.R. Antibody potency, effector function, and combinations in protection and therapy for SARS-CoV-2 infection in vivo. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2020, 218, e20201993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency Use Authorization for bebtelovimab. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/156152/download (accessed on.

- FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of sotrovimab. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/149534/download (accessed on.

- FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency Use Authorization for Evusheld (tixagevimab co-packaged with cilgavimab). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/154701/download (accessed on.

- Imai, M.; Ito, M.; Kiso, M.; Yamayoshi, S.; Uraki, R.; Fukushi, S.; Watanabe, S.; Suzuki, T.; Maeda, K.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y. Efficacy of Antiviral Agents against Omicron Subvariants BQ. 1.1 and XBB. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Iketani, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Bowen, A.D.; Liu, M.; Wang, M.; Yu, J. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell 2023, 186, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takashita, E.; Yamayoshi, S.; Halfmann, P.; Wilson, N.; Ries, H.; Richardson, A.; Bobholz, M.; Vuyk, W.; Maddox, R.; Baker, D.A. In vitro efficacy of antiviral agents against òmicron subvariant BA. 4.6. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 2094–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Oliveira, A.; Praia Borges Freire, D.; Rodrigues de Andrade, A.; de Miranda Marques, A.; da Silva Madeira, L.; Moreno Senna, J.P.; Freitas Brasileiro da Silveira, I.A.; de Castro Fialho, B. The Landscape of Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibodies (nAbs) for Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19. Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. COVID-19 Epidemiological Update, Edition 162 published 22 December 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update---22-december-2023 (accessed on 2024).

- Dyer, O. Covid-19: Infections climb globally as EG. 5 variant gains ground. BMJ 2023, p1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.; Møller, F.T.; Gunalan, V.; Baig, S.; Bennedbæk, M.; Christiansen, L.E.; Cohen, A.S.; Ellegaard, K.; Fomsgaard, A.; Franck, K.T. First cases of SARS-CoV-2 BA. 2.86 in Denmark, 2023. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28, 2300460. [Google Scholar]

- Looi, M.-K. Covid-19: Scientists sound alarm over new BA. 2.86 “Pirola” variant. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online) 2023, 382, p1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R.M.; Ho, J.; Mohri, H.; Valdez, R.; Manthei, D.M.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D.D. Antibody neutralization of emerging SARS-CoV-2: EG. 5.1 and XBC. 1.6. bioRxiv 2023, 2023–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lasrado, N.; Ai-ris, Y.C.; Hachmann, N.P.; Miller, J.; Rowe, M.; Schonberg, E.D.; Rodrigues, S.L.; LaPiana, A.; Patio, R.C.; Anand, T. Neutralization escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariant BA. 2.86. Vaccine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Lee, S.-S.; Dhama, K.; Chakraborty, C. Antibody evasion associated with the RBD significant mutations in several emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants and its subvariants. Drug Resistance Updates 2023, 101008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Guo, H.; Jian, L.; Xiao, J.; Yao, X.; Yu, H.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Evolving spike mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants facilitate evasion from breakthrough infection-acquired antibodies. Cell Discovery 2023, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheward, D.J.; Yang, Y.; Westerberg, M.; Öling, S.; Muschiol, S.; Sato, K.; Peacock, T.P.; Hedestam, G.B.K.; Albert, J.; Murrell, B. Sensitivity of the SARS-CoV-2 BA. 2.86 variant to prevailing neutralising antibody responses. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, e462–e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uriu, K.; Ito, J.; Kosugi, Y.; Tanaka, Y.L.; Mugita, Y.; Guo, Z.; Hinay, A.A.; Putri, O.; Kim, Y.; Shimizu, R. Transmissibility, infectivity, and immune evasion of the SARS-CoV-2 BA. 2.86 variant. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, e460–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Initial Risk Evaluation of JN.1, 19 December 2023. 2023.

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, L. Fast evolution of SARS-CoV-2 BA. 2· 86 to JN. 1 under heavy immune pressure. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2023.

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Uriu, K.; Hinay, A.A.; Chen, L.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Kobiyama, K.; Ishii, K.J. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN. 1 variant. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, C.L.; Hiergeist, A.; Schuster, P.; Rohrhofer, A.; Medenbach, J.; Gessner, A.; Peterhoff, D.; Schmidt, B. Targeted escape of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro from monoclonal antibody S309, the precursor of sotrovimab. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 966236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.; An, R.; et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature 2022, 602, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, J. What to Know About EG.5, the Latest SARS-CoV-2 "Variant of Interest". Jama 2023, 330, 900–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashoor, D.; Marzouq, M.; Fathallah, M.D. In silico evaluation of anti SARS-CoV-2 antibodies neutralization power: A blueprint with monoclonal antibody Sotrovimab (preprint). 2023. [CrossRef]

- Starr, T.N.; Czudnochowski, N.; Liu, Z.; Zatta, F.; Park, Y.-J.; Addetia, A.; Pinto, D.; Beltramello, M.; Hernandez, P.; Greaney, A.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies that maximize breadth and resistance to escape. Nature 2021, 597, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.E.; Brown-Augsburger, P.L.; Corbett, K.S.; Westendorf, K.; Davies, J.; Cujec, T.P.; Wiethoff, C.M.; Blackbourne, J.L.; Heinz, B.A.; Foster, D.; et al. The neutralizing antibody, LY-CoV555, protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in nonhuman primates. 2021, 13, eabf1906. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Shan, C.; Duan, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Song, J.; Song, T.; Bi, X.; Han, C.; Wu, L.; et al. A human neutralizing antibody targets the receptor-binding site of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 584, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurini, E.; Marson, D.; Aulic, S.; Fermeglia, A.; Pricl, S. Molecular rationale for SARS-CoV-2 spike circulating mutations able to escape bamlanivimab and etesevimab monoclonal antibodies. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 20274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Zost, S.J.; Greaney, A.J.; Starr, T.N.; Dingens, A.S.; Chen, E.C.; Chen, R.E.; Case, J.B.; Sutton, R.E.; Gilchuk, P.; et al. Genetic and structural basis for SARS-CoV-2 variant neutralization by a two-antibody cocktail. Nature Microbiology 2021, 6, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Ryu, D.-K.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.-I.; Seo, J.-M.; Kim, Y.-G.; Jeong, J.-H.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, P.; et al. A therapeutic neutralizing antibody targeting receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Baum, A.; Pascal, K.E.; Russo, V.; Giordano, S.; Wloga, E.; Fulton, B.O.; Yan, Y.; Koon, K.; Patel, K.; et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. 2020, 369, 1010-1014. [CrossRef]

- Westendorf, K.; Žentelis, S.; Wang, L.; Foster, D.; Vaillancourt, P.; Wiggin, M.; Lovett, E.; van der Lee, R.; Hendle, J.; Pustilnik, A.; et al. LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab) potently neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cell reports 2022, 39, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Li, L.; Dou, Y.; Shi, R.; Duan, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Wu, J.; He, Y.; et al. Etesevimab in combination with JS026 neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2022, 11, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Han, X.; Yan, J. Structure-based neutralizing mechanisms for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2022, 11, 2412–2422. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford-University. SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online: https://covdb.stanford.edu/variants/omicron_ba_1_3/ (accessed on 2023).

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic acids research 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gunsteren, W.F.; Billeter, S.R.; Eising, A.A.; Hünenberger, P.H.; Krüger, P.; Mark, A.E.; Scott, W.R.P.; Tironi, I.G. Biomolecular simulation: the GROMOS96 manual and user guide. Vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich, Zürich 1996, 86, 1–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Myung, Y.; Pires, D.E.V.; Ascher, D.B. CSM-AB: graph-based antibody–antigen binding affinity prediction and docking scoring function. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 1141–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Swindells, M.B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2011, 51, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E.; Henrick, K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography 2004, 60, 2256–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLano, W. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.4. 0 Schrödinger, LLC. 2002.

- FDA. Emergency Use Authorization. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization#coviddrugs (accessed on 2023).

- EMA. COVID-19 treatments. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/covid-19-treatments (accessed on 2023).

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, P. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Nature reviews Immunology 2023, 23, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touret, F.; Baronti, C.; Bouzidi, H.S.; de Lamballerie, X. In vitro evaluation of therapeutic antibodies against a SARS-CoV-2 Omicron B.1.1.529 isolate. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D.; Casadevall, A. A critical analysis of the use of cilgavimab plus tixagevimab monoclonal antibody cocktail (Evusheld™) for COVID-19 prophylaxis and treatment. Viruses 2022, 14, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Cao, J.; Liang, Q.; Qu, J.; Zhou, M. Serum neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2, BA.2.75, BA.2.76, BA.5, BF.7, BQ.1.1 and XBB.1.5 in individuals receiving Evusheld. Journal of medical virology 2023, 95, e28932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (accessed on 2024).

- Wang, L.; Møhlenberg, M.; Wang, P.; Zhou, H. Immune evasion of neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2023.

- Miller, J.; Hachmann, N.P.; Collier, A.-r.Y.; Lasrado, N.; Mazurek, C.R.; Patio, R.C.; Powers, O.; Surve, N.; Theiler, J.; Korber, B. Substantial neutralization escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants BQ. 1.1 and XBB. 1. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, J.N.; Qu, P.; Goodarzi, N.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Carlin, C.; Saif, L.J.; Oltz, E.M.; Xu, K.; Jones, D.; Gumina, R.J. Immune evasion and membrane fusion of SARS-CoV-2 XBB subvariants EG. 5.1 and XBB. 2.3. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2023, 12, 2270069. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, P.; Evans, J.P.; Faraone, J.N.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Carlin, C.; Anghelina, M.; Stevens, P.; Fernandez, S.; Jones, D.; Lozanski, G. Enhanced neutralization resistance of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BQ. 1, BQ. 1.1, BA. 4.6, BF. 7, and BA. 2.75. 2. Cell host & microbe 2023, 31, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zou, J.; Kurhade, C.; Deng, X.; Chang, H.C.; Kim, D.K.; Shi, P.-Y.; Ren, P.; Xie, X. Less neutralization evasion of SARS-CoV-2 BA. 2.86 than XBB sublineages and CH. 1.1. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2023, 12, 2271089. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, J. What to know about EG. 5, the latest SARS-CoV-2 “Variant of Interest”. Jama 2023.

- Parums, D.V. a rapid global increase in COVID-19 is due to the emergence of the EG. 5 (Eris) subvariant of omicron SARS-CoV-2. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research 2023, 29, e942244–942241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Feng, L.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P. Convergent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 XBB lineages on receptor-binding domain 455–456 synergistically enhances antibody evasion and ACE2 binding. PLoS pathogens 2023, 19, e1011868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D.; Spezia, P.G.; Gueli, F.; Maggi, F. The Era of the FLips: How Spike Mutations L455F and F456L (and A475V) Are Shaping SARS-CoV-2 Evolution. 2023, 16, 3.

- Iketani, S.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Chan, J.F.W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, M.; Luo, Y.; Yu, J.; Chu, H. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 2022, 604, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Iketani, S.; Guo, Y.; Chan, J.F.W.; Wang, M.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Chu, H.; Huang, Y.; Nair, M.S. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2022, 602, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Model | Resolution Å |

Antibody | Heavy chain ID |

Light chain ID |

RBD chain ID |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7R6W | 1.83 | Sotrovimab (S309) | A | B | R | [29] |

| 2 | 7KMG | 2.16 | Bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) | A | B | C | [30] |

| 3 | 7L7E | 3.00 | Evusheld (AZD8895) | A | B | G | [33] |

| 4 | 7L7E | 3.00 | Evusheld (AZD1061) | E | F | G | [33] |

| 5 | 7CM4 | 2.71 | Regdanvimab (CT-P59) | H | L | A | [34] |

| 6 | 6XDG | 3.90 | Casirivimab (REGN10933) | B | D | E | [35] |

| 7 | 6XDG | 3.90 | Imdevimab (REGN10987) | C | A | E | [35] |

| 8 | 7MMO | 2.43 | Bebtelovimab (LY-CoV1404) | A | B | C | [36] |

| 9 | 7C01 | 2.88 | Etesevimab (LY-CoV016) CB6, JS016, LY3832479 |

H | L | A | [31] [32] |

| 10 | 7F7E | 2.49 | JS026 | C | L | E | [37] |

| Antibody | FDA[47] | EMA[48] |

|---|---|---|

| Sotrovimab (S309) | Authorized May 2021 Revoked April 2022 * |

Authorized December 2021 up to date Under the name Xevudy |

| Bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) |

Authorized September 2021 Administered together as a combination (Bamlanivimab/Etesevimab) Revoked January 2022* |

October 2021 Bamlanivimab and Etesevimab EMA ended the rolling review due to withdrawing from the process by the company (Eli Lilly Netherlands BV) |

| Etesevimab (LY-CoV016, CB6, JS016) | ||

| Evusheld (Tixagevimab -AZD8895) | Authorized August 2021 Revoked January 2023 Evusheld (tixagevimab co-packaged with cilgavimab) cocktail No longer authorized* |

Authorized March 2022 up to date Evusheld (tixagevimab co-packaged with cilgavimab) cocktail |

| Evusheld (Cilgavimab-AZD1061) | ||

| Regdanvimab (CT-P59) | No authorization | Authorized November 2021 up to date Under the name Regkirona |

| Casirivimab (REGN10933) | Authorized November 2020 Revoked January 2022 REGEN-COV (Casirivimab / Imdevimab) cocktail No longer authorized* |

Authorized November 2021 up to date Under the name Ronapreve (Casirivimab / imdevimab) cocktail |

| Imdevimab (REGN10987) | ||

| Bebtelovimab (LY-CoV1404) |

Authorized February 2022 Revoked November 2022 No longer authorized* |

No authorization |

| JS026 | Ongoing clinical trials [11] | |

| Antibody | NAb’s class | RBD access |

ACE2 competing |

Viruses neutralized | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sotrovimab (S309) | Class 3 | Up/Down | No | SARS-CoV-2; Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4/5, and BA.2.75 |

[49] |

| Bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) |

Class 2 | Up/Down | Yes | SARS-CoV-2; Alpha | [32,49,50] |

| Etesevimab (LY-CoV016, CB6, JS016 |

Class 1 | UP | Yes | SARS-CoV-2; Alpha and Delta | |

| Evusheld (Tixagevimab -AZD8895) | Class 1 | Up | Yes | SARS-CoV-2,; Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta | [50,51,52] |

| Evusheld (Cilgavimab-AZD1061) | Class 3 | Up/Down | No | SARS-CoV-2,; Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, BA.2, BA.2.75, and BA.5 | |

| Regdanvimab (CT-P59) | Class1 | Up | Yes | SARS-CoV-2; Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta | [49] |

| Casirivimab (REGN10933) | Class 1 | UP | Yes | SARS-CoV-2; Alpha and Delta, BA.2.75 | [49] |

| Imdevimab (REGN10987) | Class 3 | Up/Down | No | SARS-CoV-2; Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, BA.1, BA.2, and BA.4/5 | |

| Bebtelovimab (LY-CoV1404) |

Class 3 | Up/Down | No | SARS-CoV-2; Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4/5, and BA.2.75 | [49] |

| JS026 | Class 3 | Up/Down | No | In combination with Etesevimab. SARS-CoV-2; Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta | [37] |

| SARS-CoV-2 variant | Wuhan interaction epitope | EG.5 interaction epitope | BA.2.86 interaction epitope | JN.1 interaction epitope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imdevimab | Arg346 | Arg339 (Arg346) | Arg339 (Arg346) | |

| Asn440* | Lys436 (Asn440) | Lys433 (Asn440) | Lys433 (Asn440) | |

| Leu441 | Leu437 (Leu441) | Leu434 (Leu441) | Leu434 (Leu441) | |

| Lys444 | Lys440 (Lys444) | Lys437 (Lys444) | Lys437 (Lys444) | |

| Val445 | Pro441* (Val445) | His438* (Val445) | His438* (Val445) | |

| Gly446 | Ser442 (Gly446) | Ser439 (Gly446) | Ser439 (Gly446) | |

| Gly443 (Gly447) | ||||

| Asn444 (Asn448) | ||||

| Gly440 (Gly447) | Gly440 (Gly447) | |||

| Asp443 (Asp450) | Asp443 (Asp450) | |||

| Arg494 (Gln498) | Arg490 (Gln498) | Arg490 (Gln498) | ||

| Pro495 (Pro499) | Pro491 (Pro499) | Pro491 (Pro499) | ||

| Bonds | 1 polar 14 hydrophobic |

1 polar 28 hydrophobic 1 salt bridge |

1 polar 33 hydrophobic 1 salt bridge |

1 polar 33 hydrophobic 1 salt bridge |

| JS026 | Asn343* | |||

| Thr345* | Thr341 (Thr345) | Thr338 (Thr345) | Thr338 (Thr345) | |

| Arg346 | Thr342 (Arg346) | Arg339 (Arg346) | Arg339 (Arg346) | |

| Asn439 | Asn435 (Asn439) | Asn432 (Asn439) | Asn432 (Asn439) | |

| Asn440** | Lys436* (Asn440) | Lys433* (Asn440) | Lys433* (Asn440) | |

| Leu441* | Leu437 (Leu441) | Leu434 (Leu441) | Leu434 (Leu441) | |

| Asp442* | Asp438* (Asp442) | Asp435* (Asp442) | Asp435* (Asp442) | |

| Ser443* | Ser439* (Ser443) | Ser436* (Ser443) | Ser436* (Ser443) | |

| Lys444 | Lys440* (Lys444) | Lys437* (Lys444) | Lys437* (Lys444) | |

| Val445 | Pro441 (Val455) | His438 (Val445) | His438 (Val445) | |

| Asn448 | Asn444* (Asn448) | Asn441* (Asn448) | Asn441* (Asn448) | |

| Tyr451 | Tyr447 (Tyr451) | Tyr444 (Tyr451) | Tyr444 (Tyr451) | |

| Pro499 | Pro495 (Pro499) | Pro491 (Pro499) | Pro491 (Pro499) | |

| Thr500 | Thr496 (Thr500) | Thr492 (Thr500) | Thr492 (Thr500) | |

| Arg509 | Arg505 (Arg509) | Arg501 (Arg509) | Arg501 (Arg509) | |

| Bonds | polar 54 hydrophobic |

4 polar 66 hydrophobic |

6 polar 72 hydrophobic |

75 polar 75 hydrophobic salt bridge |

| Wuhan PBD ID: 7R6W- Chain R |

BA.2.86 and JN.1 | EG.5 |

|---|---|---|

| Tyr 369 Asn 370 Ser 371 Ala 372 |

Tyr 362 Asn 363 Phe 364 Ala 365 |

Tyr 365 Asn 366 Phe 367 Ala 368 |

| - Lys 386 Leu 387 |

Lys 379 Leu 380 - |

Lys 382 Leu 383 - |

| Gly 482 | - | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).