1. Introduction

The Valsalva maneuver is a particular way of breathing, which is performed by forceful exhalation against closed rima glottidis. Modifications of this maneuver comprise closing the mouth together with pinching the nose, or blowing into empty syringe or a similar container; for the purpose of scientific investigations such containers can be standardized [

1,

2,

3]. Valsalva maneuver results in an increased pressure in the chest, which is also transmitted to the abdominal cavity. There are several physiological responses to Valsalva maneuver, particularly an activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, an increase of the arterial blood pressure and decreased cardiac output [

4,

5,

6].

Since an increased intra-abdominal pressure stabilizes the torso, this type of breathing is commonly used during strength physical exercises, such as lifting weights or doing sit-ups [

7,

8]. Therefore, the Valsalva maneuver and its physiological effects remain within the scope of the sport medicine [

9,

10,

11]. It is well known, that in addition to the physiological effects of the Valsalva maneuver in the organs of the thoracic and abdominal cavities, this way of breathing changes morphology and flow pattern in the lower extremity veins. During Valsalva maneuver these veins dilate, and if their valves are incompetent, there is a reversed flow (reflux) in these blood vessels. Therefore, this maneuver is routinely used during ultrasonographic examination of the lower extremity veins, in order to reveal pathological refluxes [

3,

12]. Of note, it has been postulated that positional dilatations of the lower extremity veins are likely to be associated with an increased risk of varicose veins. Such a positional dilatation is seen during standing, hence a higher prevalence of varicose veins in the individuals working in the standing position. Still, Valsalva maneuver represents a particularly stressful condition for the veins of the lower extremities. Therefore, this maneuver, if performed frequently, might also be a risk factor of varicose veins, even if scientific evidence of such an association is weak.

Interestingly, yoga practitioners are discouraged from Valsalva maneuver during exercises, even if many of them, like kumbhakasana (plank pose) or utkatasana (chair pose), also require torso stabilization. Instead, yoga practitioners are recommended to use the ujjayi (victorious) breath, which consists of unstopped breathing, yet through the narrowed, but not closed glottis, like during whispering [

13,

14,

15]. Such breathing should theoretically be less stressful for the lower extremity veins, yet these blood vessels were never examined at such conditions.

The aim of this study was to assess vein diameters and valve function in the area of the sapheno-femoral junction during Valsalva maneuver and ujjayi breath, in order to evaluate the influence of these modes of breathing on the lower extremity veins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Particpants and Study Design

This study was an observational research performed in healthy participants. For this purpose, we recruited 10 healthy individuals, 8 women and 2 men, without clinical or ultrasonographic signs of lower extremity venous pathology, and with an experience in yogic breathing. They were aged 28-59 years, mean 42.6 years. In all of them ultrasonographic examination of the veins in the groin area was performed. These examinations were done on both sides; thus 20 areas of the sapheno-femoral junction (SFJ) were studied.

Inclusion criteria of this study comprised:

Exclusion criteria of the study comprised:

varicose veins;

incompetence of the terminal or pre-terminal valve of the great saphenous vein revealed during ultrasonographic examination;

history of lower extremity vein thrombosis, or another clinically relevant pathology of the lower extremity veins;

co-morbidities or physical disability, which may interfere with the physical activity.

All examinations were done in the standing body position, during lifting a small weight in both hands, which stimulated the torso stabilization. Ultrasound examinations were performed with the GE Versana Active ultrasound system (GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA), using the 10 MHz linear probe and the Lower Extremity Vein preset. Cross-sectional areas of the following veins were measured:

- ▪

femoral vein 2 cm above the SFJ;

- ▪

femoral vein at the level of the SFJ;

- ▪

femoral vein 2 cm distally from the SFJ;

- ▪

great saphenous vein between the terminal and pre-terminal valves;

- ▪

great saphenous vein 1 cm distally from the pre-terminal valve.

We also evaluated the competence and function of the terminal and pre-terminal valves of the great saphenous vein. All these measurements were done during:

- ▪

normal breathing;

- ▪

Valsalva maneuver, which was performed through deep inhalation followed by forceful exhalation against the closed glottis (without pinching the nose);

- ▪

ujjayi breath, which was performed in a standard way [

15].

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals participating in this survey. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study protocol has been approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of Opole; approval No UO/0032/KB/2023.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

In order to statistically assess the differences between cross-sectional areas of the examined veins, the paired t-test and the one-way ANOVA test were used. The significance of P values was set at P < .05. We also calculated the F values and the -squared of the ANOVA test. The statistical analysis was performed using the PAST data analysis package (version 3.0; University of Oslo, Norway).

3. Results

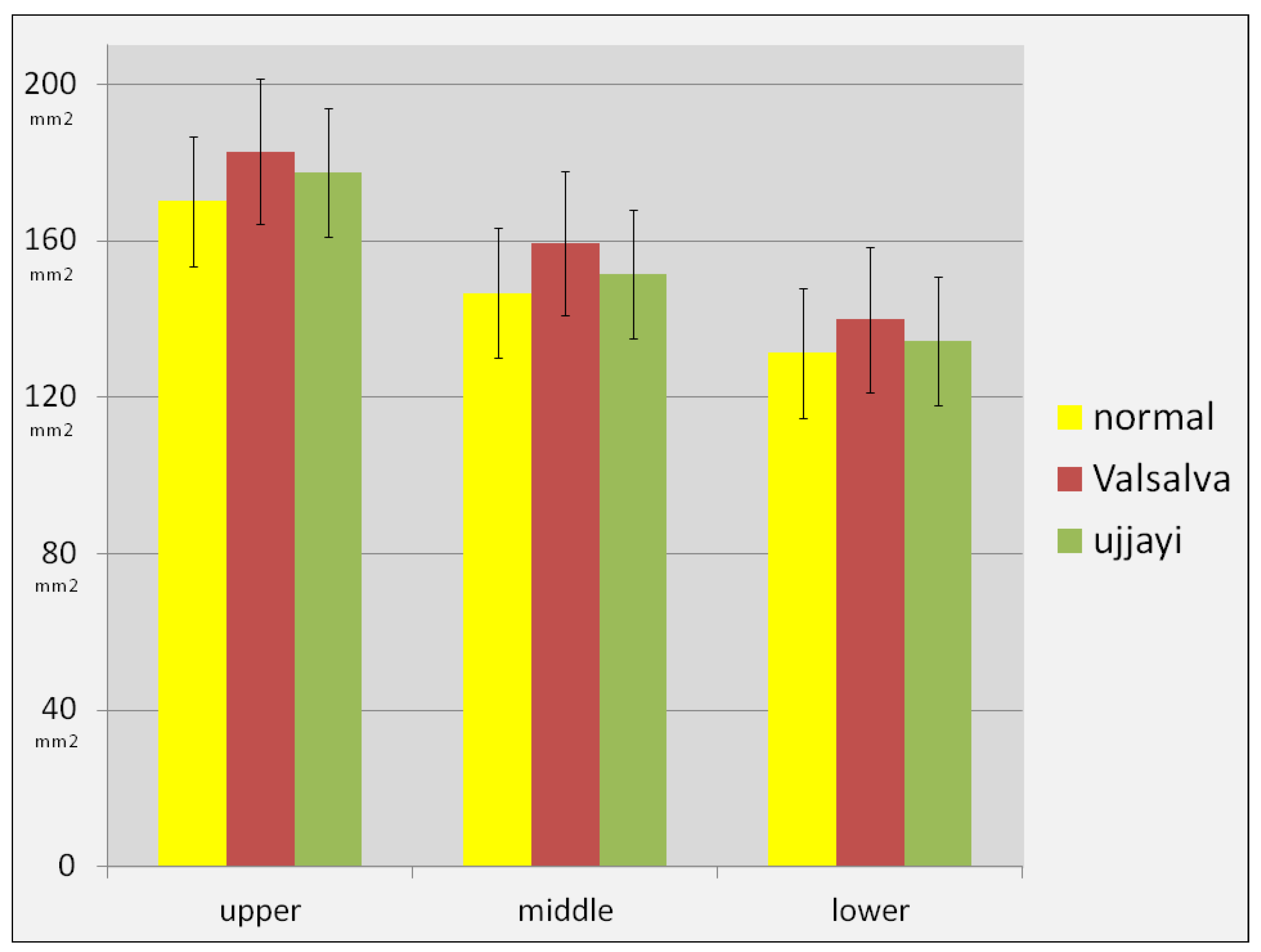

In comparison with normal breathing, there were only slight dilatations of the examined veins both during Valsalva and ujjayi breath. On average, in comparison with the normal breathing, the cross-sectional area of the femoral vein increased by 7-9% during Valsalva and 2-4% during ujjayi. The mean cross-sectional area of the femoral vein above the SFJ increased from 170.15 mm

2 during normal breathing, to 182.85 mm

2 during Valsalva and 177.50 mm

2 during ujjayi. The mean cross-sectional area of the femoral vein at the level of the SFJ increased from 146.70 mm

2 during normal breathing, to 159.30 mm

2 during Valsalva and 151.40 mm

2 during ujjayi, and the mean cross-sectional area of the femoral vein below the level of the SFJ increased from 131.30 mm

2 during normal breathing, to 139.90 mm

2 during Valsalva and 134.35 mm

2 during ujjayi (

Figure 1). Still, these rather small differences were not statistically significant (P > .05, and the F values were smaller than the critical ones at given degrees of freedom. The η-squared ranged .015-.032, indicative of a small effect size.

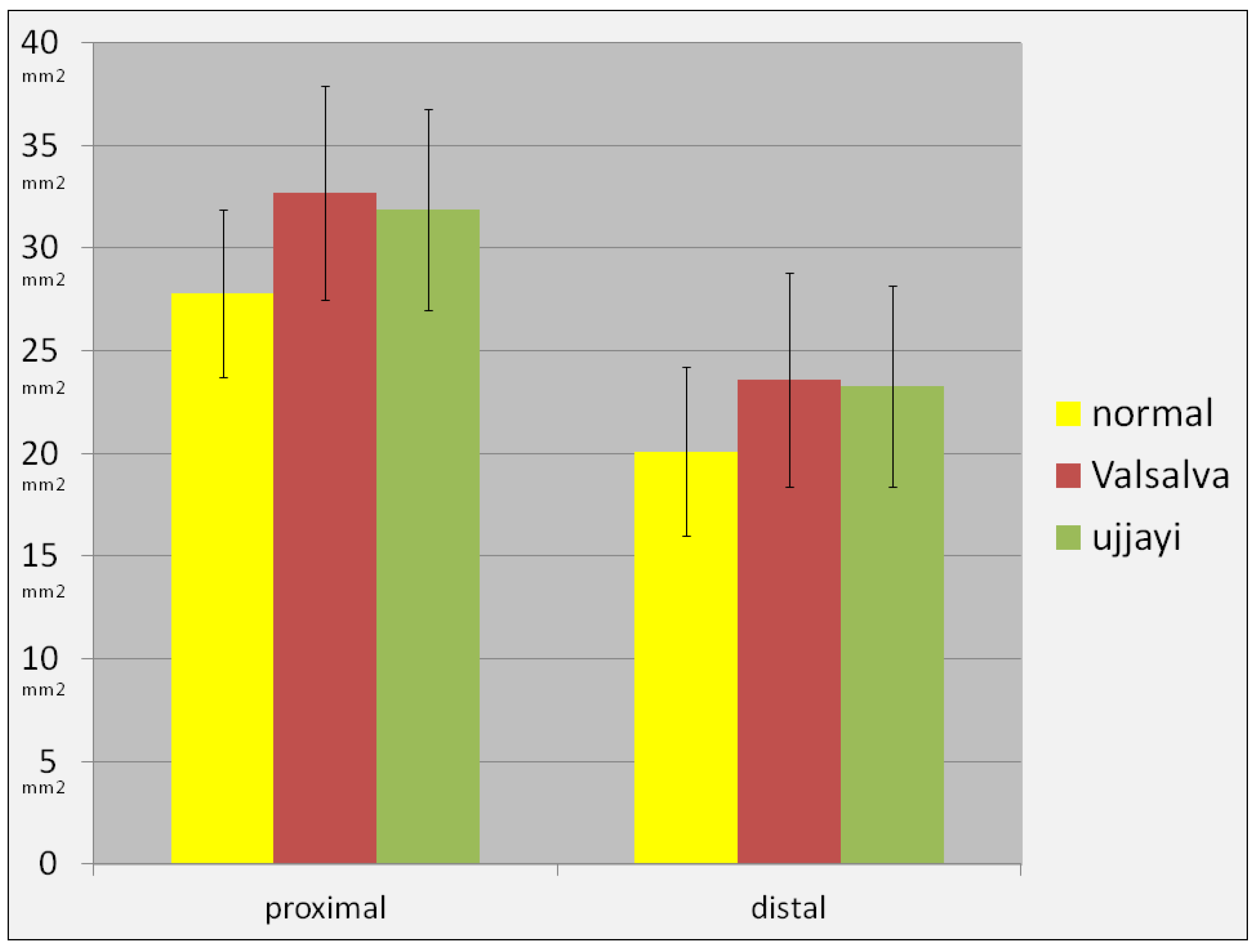

Similarly, the cross-sectional area of the GSV between terminal and preterminalną valve increased by 18% during Valsalva and 15% ujjayi breath, from 27.75 mm

2 to 32.70 mm

2 and 31.90 mm

2, respectively; while the cross-sectional area of the GSV distally from the pre-terminal valve increased by 17% during Valsalva and 16% during ujjayi breath, from 20.05 mm

2 to 23.55 mm

2 and 23.25 mm

2, respectively. Also these differences were statistically insignificant, with P > .05 and small F values, while the -squared was .034 and .047, which revealed a small effect size (

Figure 2).

In all participants the terminal and pre-terminal valves were competent and no refluxes were detected. However, there was one important difference regarding function of the terminal valve. While the Valsalva maneuver was associated with complete closure of this valve. It can be seen in

Video S1. Here, the terminal valve of the GSV (yellow arrows) is completely closed during Valsalva, and there is blood stagnation in the proximity of this valve, seen as the change of color from black to whitish (GSV – great saphenous vein; FV – femoral vein; FA – femoral artery).

During ujjayi breath this valve was opening and closing, following the breathing (

Video S2). There was almost constant flow across the terminal valve (yellow arrows). The function of the terminal valve during ujjayi breath was similar to that during normal breathing (

Video S3). There was also a continuous flow across the terminal valve (yellow arrows) toward the femoral vein. Thus, during Valsalva maneuver, there was a blood stagnation distally from the terminal valve. On the contrary, during ujjayi breath, the flow from the GSV toward the femoral vein was not disturbed.

4. Discussion

In this study we demonstrated that in the standing body position, in comparison with normal breathing, during Valsalva and ujjayi breathing there are only slight dilatations of the femoral and great saphenous veins. It means that in this body posture the veins in the groin area are already submaximally dilated and that an increase of intra-abdominal pressure results only in a small increase of their cross-sectional areas. The effect of both Valsalva and ujjayi on the cross-sectional areas of these veins is similar, although we revealed slightly larger dilatations after Valsalva, which probably reflected a minimally higher intra-abdominal pressure associated with this type of breathing. Yet, these more pronounced dilatations could also be associated with the stagnation of flow during Valsalva. We also revealed a contrasting behavior of the terminal valve of the great saphenous vein. During Valsalva maneuver there was a complete closure of this valve, while during ujjayi breath it opened and closed normally, preventing the flow stagnation distally from this valve. Consequently, the results of this study suggest that during strength physical exercises, such as lifting weights, torso stabilization by Valsalva maneuver should be avoided. It particularly concerns individuals with already present small varicose veins or those at risk of the development of chronic venous disease, for example due to positive family history. Yogic type of breathing, particularly the ujjayi breath, offers a valuable and safe alternative to the Valsalva maneuver.

To the best of our knowledge the effect of Valsalva maneuver and yogic breathing on the lower extremity veins has not been studied in the standing body position. All published studies examined these veins in the context of breathing in the supine body position. It is well known that in the horizontal body position, due to gravitational effects, lower extremity veins are partially collapsed. During Valsalva maneuver, when the intra-abdominal pressure increases, this pressure is transmitted through the valveless iliac veins to the femoral veins [

17]. Consequently, the femoral veins dilate. Also other previously collapsed veins of the lower limb may dilate, especially if their valves are incompetent. In the supine body position this change of cross-sectional areas of the femoral vein has been demonstrated to be quite significant, at the level of 40-80% [

1,

2,

3].

However, in real life Valsalva maneuver is rarely performed in the horizontal body position. People use this type of breathing predominantly while sitting or standing. In our study, we have demonstrated that in the standing body position the femoral and the great saphenous vein also dilate during Valsalva maneuver. Yet, these dilatations were quite small, at the level of few percentages. In our material these differences were statistically insignificant, still the number of individuals assessed was small, hence probably the statistical insignificance of these increases. Possibly, if there were, for example, 30 instead of 10 participants, the

P value would be less than .05. Nonetheless, these small changes are probably without clinical relevance. On the other hand, the behavior of the terminal valve is of potential clinical importance. The great saphenous vein is the main superficial vein of the lower extremity. It is located at the medial aspect of the limb, and in the groin it drains into the femoral vein. The great saphenous vein provides the main outflow route from the superficial structures of the lower leg and thigh, and also from the foot during contraction of the lower leg muscles. The most proximal part of the great saphenous vein, in the proximity of its connection with the femoral vein, is referred to as the SFJ. Here, typically two valves are present: the terminal valve, which is located at the estuary of the great saphenous vein, and the pre-terminal valve, which is located a few centimeters distally. These two valves are pivotal for the proper outflow from the great saphenous vein, and play an important role in the pathogenesis of varicose veins [

16]. In our study were revealed the stop of flow across the terminal valve during Valsalva maneuver. This phenomenon, together with flow stagnation distally from this valve, in a long–run may theoretically result in a steadily dilatation of the proximal segment of the great saphenous vein, finally leading to the development of varicose veins. Although this scenario cannot be proved experimentally, in addition to the known cardiovascular, neurological and ophthalmological sequelae of the Valsalva maneuver, it is another argument against performing Valsalva during physical exercises and sport activities, if other methods of torso stabilization are available.

Physical activity, including the gym exercises, are widely recognized as an important part of the healthy lifestyle. Yet, many gym exercises are associated with non-physiologic conditions, which, at least theoretically, may have undesired health consequencies. For example, lifting weights and similar exercises, like squats or push-ups, require torso stabilization. It is usually achieved using Valsalva maneuver, which secures the lumbar part of spinal column through an increased pressure in the abdominal cavity [

17]. Indeed, many sportsmen and people training in the gym use Valsalva maneuver, even if they are unaware of it. Still, in addition to the obvious benefits of Valsalva maneuver, especially the protection of the spinal column, there are many side effects associated with this type of breathing. They particularly concern the increased intra-thoracic pressure, which leads to several cardiovascular responses. Consequently, Valsalva maneuver is contraindicated in people with coronary artery disease, severe arterial hypertension, aortic aneurysms, valvular heart disease and retinopathy. Of note, in real life a complete avoidance of the Valsalva maneuver is not possible, since it is used for example during defecation. Also, Valsalva is unavoidable during professional weight lifting and some other sports. Yet, a majority of sport activities that require torso stabilization can be done in the way, which is practiced in yoga. Unfortunately, in spite of a long history of yoga, its scientific background in rather slim. There were only a few scientific investigations on clinical effects of yogic breathing (actually, there are many types of breathing used in yoga, and ujjayi is only one of the many). Besides, a majority of these studies are of low scientific quality. Effects of various types of yogic breathing have been investigated primarily in the context of the respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological disorders [

15,

18,

19,

20]. Interestingly, in one of such studies it was demonstrated that ujjayi breath improved the cardio-respiratory control in patients with spinal cord injury [

14].

We acknowledge that there are some important limitations of our study. We examined only 10 individuals. Yet, considering the fact that standard deviations of the measurements were rather small (

Figure 1 and

2), the results in a larger cohort would probably be similar. Besides, we examined only veins in the area of the SJF. Obviously, an assessment of other lower extremity veins during different modes of breathing would provide more complete functional picture. Since the current study was actually planned to be a pilot one, results presented in this paper would provide a useful framework for future investigations on this topic.

Acknowledging the limitation of this small group study, there are several practical implications of this research. Firstly, the results of our study suggest that during strength physical exercises, such as lifting weights, torso stabilization by the Valsalva maneuver should be avoided whenever possible. It may particularly concern the individuals with already present small varicose veins or those at risk of the development of chronic venous disease, for example, due to the positive family history. Secondly, a yogic type of breathing, particularly the ujjayi breath, offers a valuable and safe alternative to the Valsalva maneuver while stabilizing the torso during physical exercises.

5. Conclusions

In the standing body position, veins in the area of the SFJ are already submaximally dilatated, and both Valsalva and ujjayi breath have minimal effect on their cross-sectional areas. On the other hand, ujjayi breath allows for undisturbed flow through the SFJ, while the Valsalva maneuver interrupts this flow, resulting in blood stagnation distally from the terminal valve of the great saphenous vein. Potential long-term pathological consequences of this phenomenon remain to be investigated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Video S1: Flow through the sapheno-femoral junction during Valsalva; Video S2: Flow through the sapheno-femoral junction during ujjayi breath; Video S3: Flow through the sapheno-femoral junction during normal breathing.

Video legends: Video 1 - Flow through the sapheno-femoral junction during Valsalva. The terminal valve (yellow arrows) is completely closed and there is blood stagnation in the proximity of this valve, seen as the change of color from black to whitish. GSV – great saphenous vein; FV – femoral vein; FA – femoral artery.

Video 2 – Flow through the sapheno-femoral junction during ujjayi breath. There is almost constant flow across the terminal valve (yellow arrows). GSV – great saphenous vein; FV – femoral vein; FA – femoral artery.

Video 3 - Flow through the sapheno-femoral junction during normal breathing. There is constant flow across the terminal valve (yellow arrows) toward the femoral vein. GSV – great saphenous vein; FV – femoral vein; FA – femoral artery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.K., P.L., M.S.; Data curation, U.K.; Investigation, U.K., M.S.; Methodology, U.K., A.K., K.B.; Project administration, K.B., M.S.; Resources, K.B.; Supervision, M.S.; Validation, P.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; Writing—review and editing, U.K., P.L., M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of Opole; approval No UO/0032/KB/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Prana Yoga School in Jastrzębie-Zdrój and the “Na Ciepłej” Adult Daycare Centre in Wrocław for their help in organizing this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fronek, A.; Criqui, M.H.; Denenberg, J.; Langer, R.D. Common femoral vein dimensions and hemodynamics including Valsalva response as a function of sex, age, and ethnicity in a population study. J Vasc Surg 2001, 33, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeanneret, C.; Jäger, K.A.; Zaugg, C.E.; Hoffmann, U. Venous reflux and venous distensibility in varicose and healthy veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007, 34, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanneret, C.; Labs, K.H.; Aschwanden, M.; Bollinger, A.; Hoffmann, U.; Jäger, K. Physiological reflux and venous diameter change in the proximal lower limb veins during a standardised Valsalva manoeuvre. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1999, 17, 98–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, W.; Pilis, W.; Laskowska, D.; Gąsiorowska, A.; Cybulski, G.; Strasz, A. Effects of a brief Valsalva manoeuvre on hemodynamic response to strength exercises. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2012, 32, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pstras, L.; Thomaseth, K.; Waniewski, J.; Balzani, I.; Bellavere, F. The Valsalva manoeuvre: physiology and clinical examples. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2016, 217, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looga, R. The Valsalva manoeuvre--cardiovascular effects and performance technique: A critical review. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2005, 147, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, D.A.; Chow, C.M. The Valsalva maneuver: Its effect on intra-abdominal pressure and safety issues during resistance exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2013, 27, 2338–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cholewicki, J.; Juluru, K.; Radebold, A.; Panjabi, M.M.; McGill, S.M. Lumbar spine stability can be augmented with an abdominal belt and/or increased intra-abdominal pressure. Eur Spine J 1999, 8, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haykowsky, M.J.; Eves, N.D.; Warburton, D.E.R.; Findlay, M.J. Resistance exercise, the Valsalva maneuver, and cerebrovascular transmural pressure. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003, 35, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, B.G.; De Hamel, T.; Thomas, K.N.; Wilson, L.C.; Gibbons, T.D.; Cotter, J.D. Cerebrovascular haemodynamics during isometric resistance exercise with and without the Valsalva manoeuvre. Eur J Appl Physiol 2020, 120, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linsenbardt, S.T.; Thomas, T.R.; Madsen, R.W. Effect of breathing techniques on blood pressure response to resistance exercise. Br J Sports Med 1992, 26, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, E.M.; Kistner, R.L.; Eklof, B. Prospective study of duplex scanning for venous reflux: Comparison of Valsalva and pneumatic cuff techniques in the reverse Trendelenburg and standing positions. J Vasc Surg 1994, 20, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, H.; Vandoni, M.; Debarbieri, G.; Codrons, E.; Ugargol, V.; Bernardi, L. Cardiovascular and respiratory effect of yogic slow breathing in the yoga beginner: What is the best approach? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013, 2013, 743504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, M.D.; Hamner, J.W.; Anand, A.N.; Taylor, J.A. Cardiorespiratory effects of yogic versus slow breathing in individuals with a spinal cord injury: An exploratory cohort study. J Integr Complement Med 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoji, A.A.; Raghavendra, B.R.; Manjunath, N.K. Effects of yogic breath regulation: A narrative review of scientific evidence. J Ayurveda Integr Med 2019, 10, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simka, M.; Czaja, J.; Kawalec, A. Clinical anatomy of the lower extremity veins—topography, embryology, anatomical variability, and undergraduate educational challenges. Anatomia 2024, 3, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willenberg, T.; Clemens, R.; Haegeli, L.M.; Amann-Vesti, B.; Baumgartner, I.; Husmann, M. The influence of abdominal pressure on lower extremity venous pressure and hemodynamics: A human in-vivo model simulating the effect of abdominal obesity. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011, 41, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawardena, R.; Ranasinghe, P.; Ranawaka, H.; Gamage, N.; Dissanayake, D.; Misra, A. Exploring the therapeutic benefits of pranayama (yogic breathing): A systematic review. Int J Yoga 2020, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, T.; Elliot, C.A.; Stoner, L.; Higgins, S.; Paterson, C.; Hamlin, M.J. Association between yoga participation and arterial stiffness: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.G.; Aithala, M.R.; Das, K.K. Effect of yoga on arterial stiffness in elderly subjects with increased pulse pressure: A randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Med 2015, 23, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).