Submitted:

30 August 2024

Posted:

03 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- participant’s age >18 years,

- no co-morbidities.

- diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease, such as Parkinson disease, Alzheimer disease, or lateral amyotrophic sclerosis,

- history of cerebral stroke,

- history of surgical or endovascular treatment of carotid or vertebral arteries,

- history of cerebral disease of an inflammatory, infectious or vascular etiology,

- clinically relevant circulatory or respiratory insufficiency.

- supine,

- sitting,

- right lateral decubitus, i.e. lying on the right side,

- left lateral decubitus, i.e. lying on the left side.

Statistical Analysis

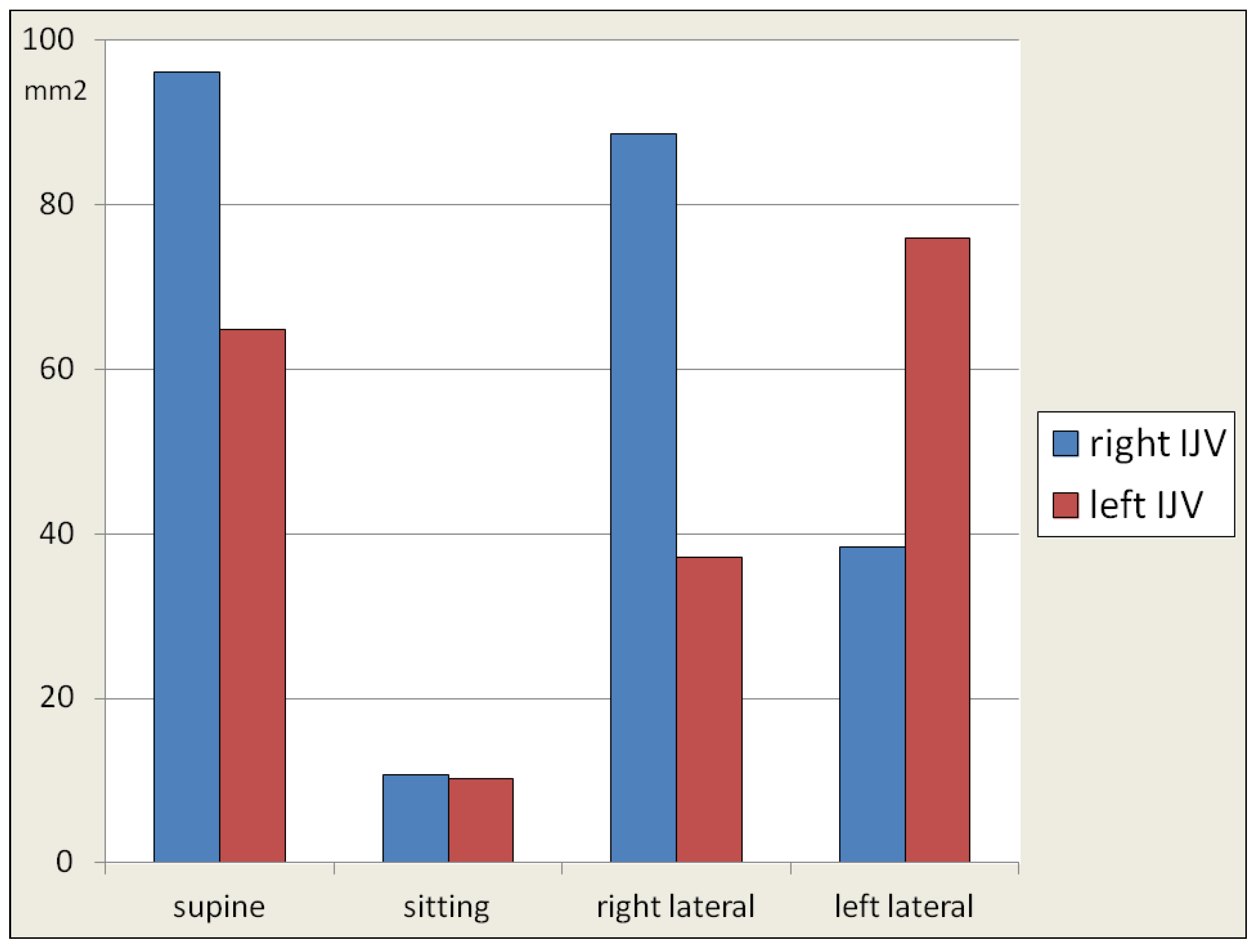

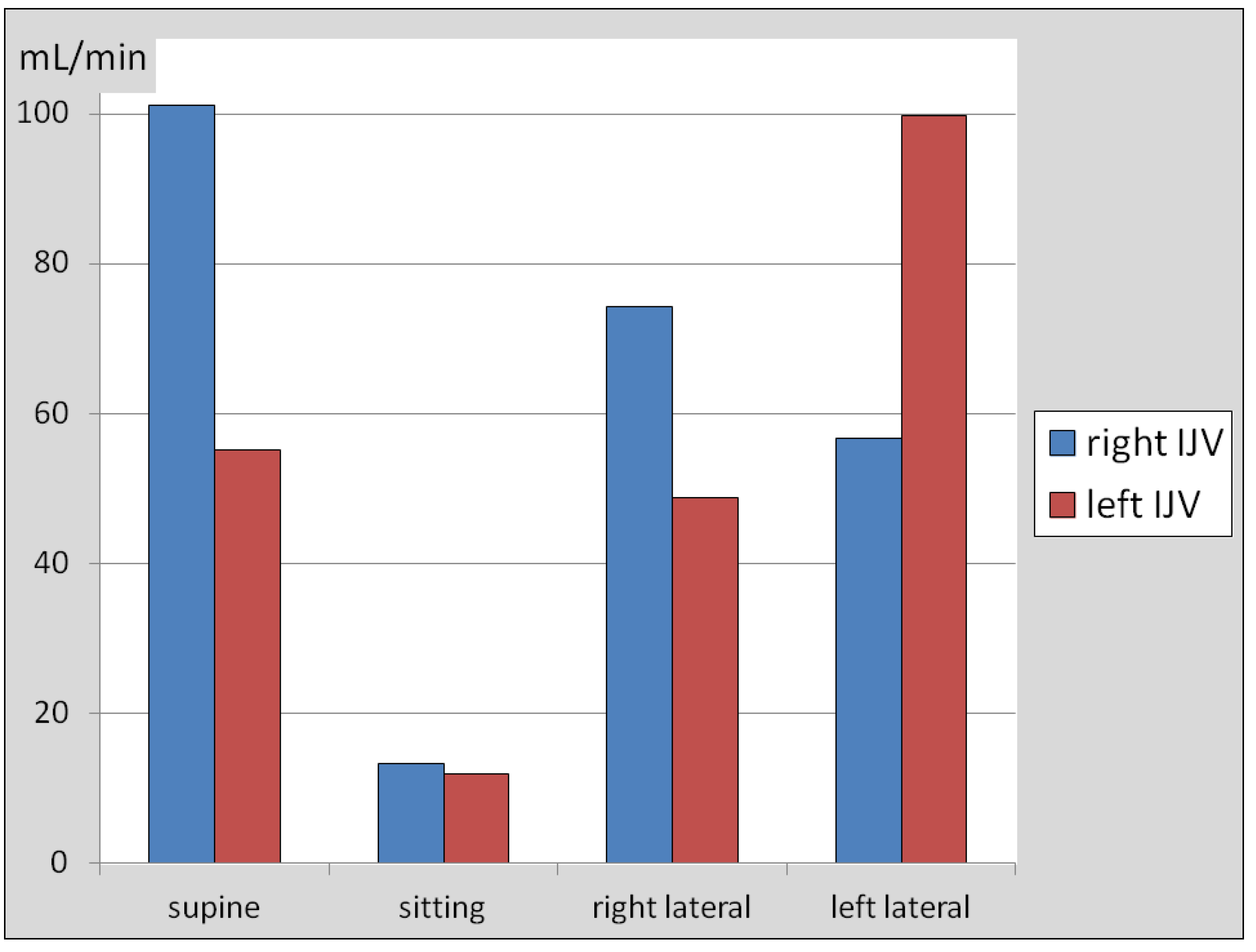

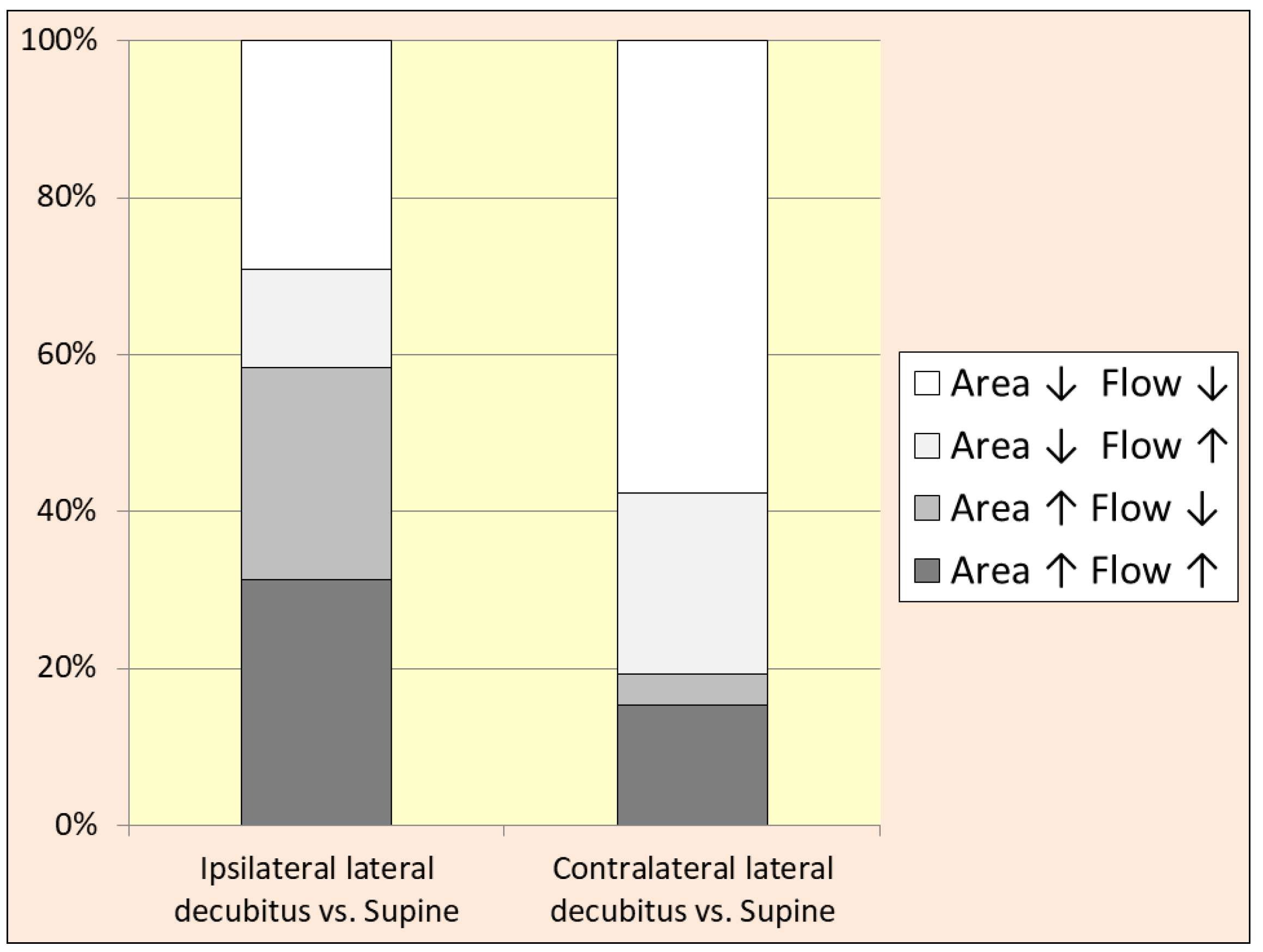

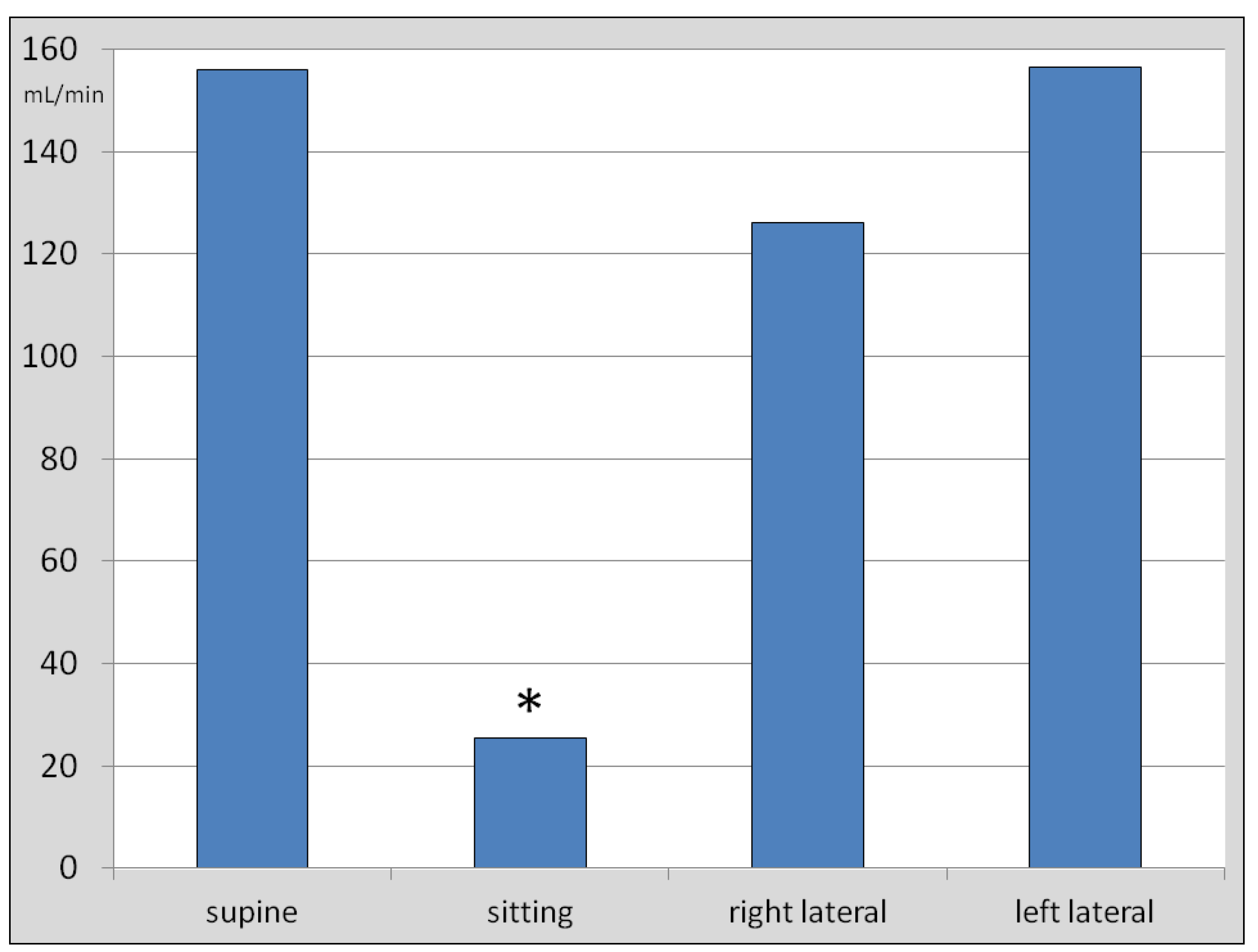

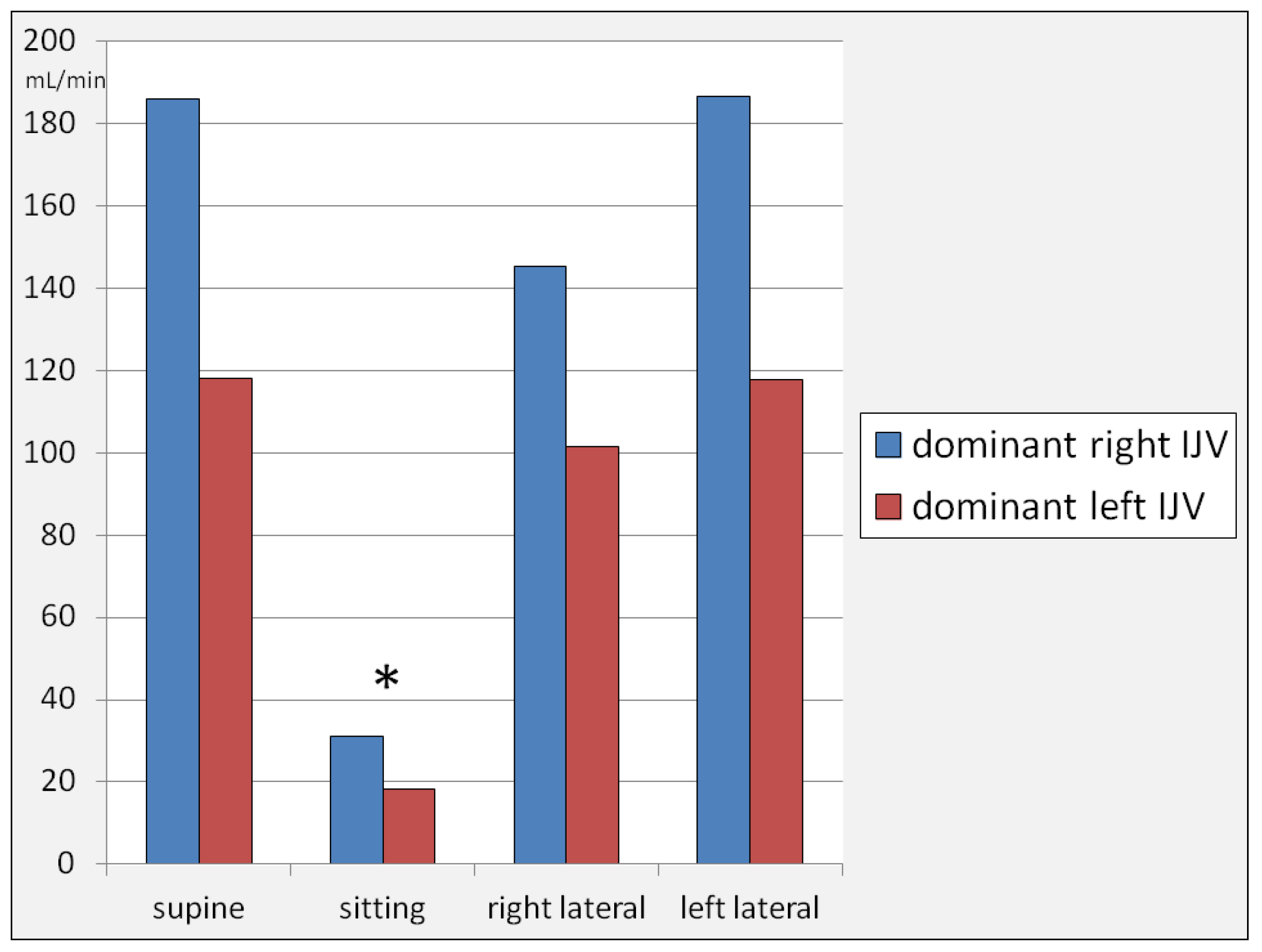

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jessen, N.A.; Finmann Munk, A.S.; Lundgaard, I.; Nedergaard, M. The glymphatic system – a beginner’s guide. Neurochem Res 2015, 40, 2583–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, A.R.; Larrick, J.W. Sleep facilitates clearance of metabolites from the brain: glymphatic function in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Rejuvenation Res 2013, 16, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, H.; Hablitz, L.M.; Xavier, A.L.; et al. , Aquaporin-4-dependent glymphatic sulute transport in the rodent brain. Elife 2018, 7, e40070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plog, B.A.; Nedergaard, M. The glymphatic system in the CNS health and disease: past, present and future. Annu Rev Pathol 2018, 13, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasoff-Conway, J.; Carare, R.O.; Osorio, R.S.; et al. Clearance systems of the brain – implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2015, 11, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benveniste, H.; Heerdt, P.M.; Fontes, M.; et al. , Glymphatic system function in relation to anesthesia and sleep states. Anesth Analg 2019, 12, 747–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, C.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Izzi, F.; et al. , Sleep apneas may represent a reversible risk factor for amyloid-β pathology. Brain 2017, 140, e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, O.C.; van der Werf, Y.D. The sleeping brain: harnessing the power of the glymphatic system through lifestyle choices. Brain Sci 2020, 10, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simka, M. Activation of the glymphatic system during sleep – is the cerebral venous outflow a missing piece of the puzzle? Phlebol Rev 2019, 27, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; et al. , Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, A.; Boag, M.; Magnier, A.; Bispo, D.; Khoo, T.; Pountney, D. glymphatic system dysfunction and sleep disturbance may contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 12928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levendowski, D.J.; Gamaldo, C.; St.Louis, E.K,; et al., Head position during sleep: potential implications for patients with neurodegenerative disease. J Alzheimer Dis 2019, 67,631-638.

- Gnarra, O.; Calvello, C.; Schirinzi, T.; Beozzo, F.; De Masi, C.; Spanetta, M.; Fernandes, M.; Grillo, P.; Cerroni, R.; Pierantozzi, M.; et al. Exploring the association linking head position and sleep architecture to motor impairment in parkinson’s disease: An exploratory study. J Pers Med 2023, 13, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girolami, S.; Tardio, M.; Loredana, S.; Di Mattia, N.; Micheletti, P.; Di Napoli, M. Sleep body position correlates with cognitive performance in middle-old obstructive sleep apnea subjects. Sleep Med X 2022, 4, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Koninck, J.; Lorrain, D.; Gagnon, P. Sleep positions and position shifts in five age groups: an ontogenetic picture. Sleep 1991, 15, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, A.; Zheng, T.; Xiao, H.; Huang, R. The relationship between sleeping position and sleep quality: A flexible sensor-based study. Sensors 2022, 22, 6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simka, M.; Czaja, J.; Kowalczyk, D. Collapsibility of the internal jugular veins in the lateral decubitus body position: a potential role of the cerebral venous outflow against neurodegeneration. Med Hypothes 2019, 133, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russak, A.; Plog, B.A.; Vates, E,; Nedergaard, M. Angiotensin II increases glymphatic flow through a norepinephrine-dependent mechanism. Neurology 2016, 86(suppl.16), P5.214.

- Fultz, N.E.; Bonmassar, G.; Setsompop, K.; Stickgold, R.A.; Rosen, B.R.; Polimeni, J.R.; Lewis, L.D. Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science 2019, 366, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Egroo, M.; Koshmanova, E.; Vandewalle, G.; Jacobs, H.I.L. Importance of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in sleep-wake regulation: Implications for aging and Alzheimer's disease. Sleep Med Rev 2022, 62, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, C.B.; Chung, C.P.; Bergsland, N.; et al. Jugular venous reflux and brain parenchyma volumes in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurology 2013, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.P.; Beggs, C.; Wang, P.N.; et al. , Jugular venous reflux and white matter abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. J Alzheimer Dis 2014, 39, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegatti, E.; Zamboni, P. Doppler haemodynamics of cerebral venous return. Curr Neurovasc Res 2008, 5, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, A,N.; Morovic, P,; Menegatti, E. et al., Screening for chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) using ultrasound - recommendations for a protocol. Funct Neurol 2011,26,229-248.

- Simka, M.; Latacz, P.; Ludyga, T.; Kazibudzki, M.; Swierad, M.; Janas, P.; Piegza, J. Prevalence of extracranial venous abnormalities: results from a sample of 586 multiple sclerosis patients. Func Neurol 2011, 26, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zivadinov, R.; Chung, C.P. Potential involvement of the extracranial venous system in central nervous system disorders and aging. BMC Med 2013, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipo, R.; Ciciarello, F.; Attanasio, G.; Mancini, P.; Covelli, E.; Agati, L.; Fedele, F.; Viccaro, M. Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in patients with Ménière’s disease. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 272, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpini, D.C.; Bavera, P.M.; Hahn, A.; Mattei, V. Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) in Meniere disease. Case or cause? Sci Med 2013, 4, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Haacke, E.M.; Feng, W.; Utriainen, D.; Trifan, G.; Wu, Z.; Latif, Z.; Katkuri, Y.; Hewett, J.; Hubbard, D. Patients with multiple sclerosis with structural venous abnormalities on mr imaging exhibit an abnormal flow distribution of the internal jugular veins. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012, 23, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisolf, J.; van Lieshout, J.J.; van Heusden, K.; et al. , Human cerebral venous outflow pathway depends on posture and central venous pressure. J Physiol 2004, 560, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, B. Physiology of cerebral venous blood flow: from experimental data in animals to normal function in humans. Brain Res Rev 2004, 46, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.J.; Lürtzing, F.; Götze, R.; et al. , Extrajugular pathways of human cerebral venous blood drainage assessed by duplex ultrasound. J Appl Physiol 2003, 94, 1802–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simka, M.; Waligóra, M.; Kowalczyk, D.; Czaja, J. Anatomy and physiology of venous outflow from the cranial cavity. In Horizons in World Cardiovascular Research.Volume 16. Bennington, E.H., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers Inc: New York, USA, 2019; pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zaniewski, M.; Simka, M. Biophysics of venous return from the brain from the perspective of the pathophysiology of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2012, 7, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirovic, S.; Walsh, C.; Fraser, W.D.; Gulino, A. . The effect of posture and positive pressure breathing on the hemodynamics of the internal jugular vein. Aviat Space Environ Med 2003, 74, 125–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niggemann, P.; Kuchta, J.; Grosskurth, D.; Beyer, H.K.; Krings, T.; Reinges, M. Position dependent changes of the cerebral venous drainage--implications for the imaging of the cervical spine. Cent Eur Neurosurg 2011, 72, 32–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zandwijk, J.K.; Kuijer, K.M.; Stassen, C.M.; Ten Haken, B.; Simonis, F.F.J. Internal jugular vein geometry under multiple inclination angles with 3D low-field MRI in healthy volunteers. J Magn Reson Imaging 2022, 56, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Sakuma, I.; Omachi, K.; et al. , Craniocervical junction venous anatomy around the suboccipital cavernous sinus: evaluation by MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2005, 15, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simka, M.; Skuła, M.; Bielaczyc, G. Validation of models of venous outflow from the cranial cavity in the supine and upright body positions. Phlebol Rev 2022, 30, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simka, M.; Czaja, J.; Kawalec, A.; Latacz, P.; Kovalko, U. Numerical modeling of venous outflow from the cranial cavity in the supine body position. Appl Sci 2024, 14, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmlund, P.; Johansson, E.; Qvarlander, S.; Wåhlin, A.; Ambarki, K.; Koskinen, L.D.; Malm, J.; Eklund, A. Human jugular vein collapse in the upright posture: implications for postural intracranial pressure regulation. Fluids Barriers CNS 2017, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simka, M.; Latacz, P. Numerical modeling of blood flow in the internal jugular vein with the use of computational fluid mechanics software. Phlebology 2021, 36, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Iqrar, S.A.; Rashid, A.; Simka, M. Results of numerical modeling of blood flow in the internal jugular vein exhibiting different types of strictures. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, M.; Novelli, E.; Pagani, R. Cross-sectional area variations of internal jugular veins during supine head rotation in multiple sclerosis patients with chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency: a prospective diagnostic controlled study with duplex ultrasound investigation. BMC Neurology 2013, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwak, M.J.; Park, J.Y.; Suk, E.H.; Kim, D.H. Effects of head rotation on the right internal jugular vein in infants and young children. Anaesthesia 2010, 65, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højlund, J.; Sandmand, M.; Sonne, M.; et al. , Effect of head rotation on cerebral blood flow velocity in the prone position. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2012, 2012, 647258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Xie, L.; Yu, M.; et al. , The effect of body posture on brain glymphatic transport. J Neurosci 2015, 35, 11034–11044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, Y.; Chan, C.C.; Fan, C.; Ji, X.; Meng, R. Internal jugular vein stenosis associated with elongated styloid process: five case reports and literature review. BMC Neurol 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivadinov, R.; Bastianello, S.; Dake, M.D.; et al. , Recommendations for multimodal noninvasive and invasive screening for detection of extracranial venous abnormalities indicative of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency: a position statement of the International Society for Neurovascular Disease. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014, 25, 1785–1794.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).