Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, affecting millions of people worldwide (1,2). AF is associated with increased risks of stroke, heart failure, overall cardiovascular morbidity and impaired physical function (3). Among the various triggers and mechanisms underlying AF, the pulmonary veins (PVs) play a crucial role (4). The pulmonary veins, have been identified as a major source of ectopic electrical activity that can initiate and sustain AF (4,5). Therefore, PVs ostia received great interest for the electrical activity of the myocardial sleeves arising from the atrial-venous junction because of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation (4,5), while their mechanical properties received little attention. Early anatomic studies in humans postulated that the myocardial fibers extending around the terminal segment of the PVs may have a putative sphincter-like function preventing the backward flow during atrial contraction (6-8), but functional data confirming this mechanical activity are scarce. By serendipity we observed a sphincter-like contractile activity of the pulmonary vein in a patient undergoing cardiac tomography scan (CT scan) for a suspected myocarditis (Video 1). We therefore decided to analyse the functional behaviour of the PVs ostia on CT scan in normal subjects and in patients with history of paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation to evaluate this putative sphincter-like function.

Methods

We developed an anatomical dynamic model to segment the PVs ostia derived from contrast enhanced CT scan to evaluate this putative sphincter-like function in in 45 subjects, 15 healthy, control subjects without AF (CTRL) 15 patients with paroxysmal (PAR) and 15 patients with persistent (PER) AF referred for PVs AF cryo-balloon ablation. They were included in the study if they had the most common four PVs anatomy, left (LSPV) and right (RSPV) superior PVs, left (LIPV) and right (RIPV) inferior PVs and trivial mitral regurgitation on transthoracic echocardiography. Each patient included in this retrospective analysis provided informed consent for the data collection and analysis. CT scan ECG-gated dynamic acquisitions of the heart after contrast medium injection were performed with a 64-slice multi-detector CT scanner (Philips Brilliance 64 CT scanner) in sinus rhythm. From ventricular end diastole, volumetric CT images were reconstructed for a total of 10 phases. Each CT volume was 512x512x200 pixels. The voxel resolution was not isotropic: 0.39 mm on x-y plane and 1 mm of slice thickness, yielding a voxel size of 0.39x0.39x1 mm 3.

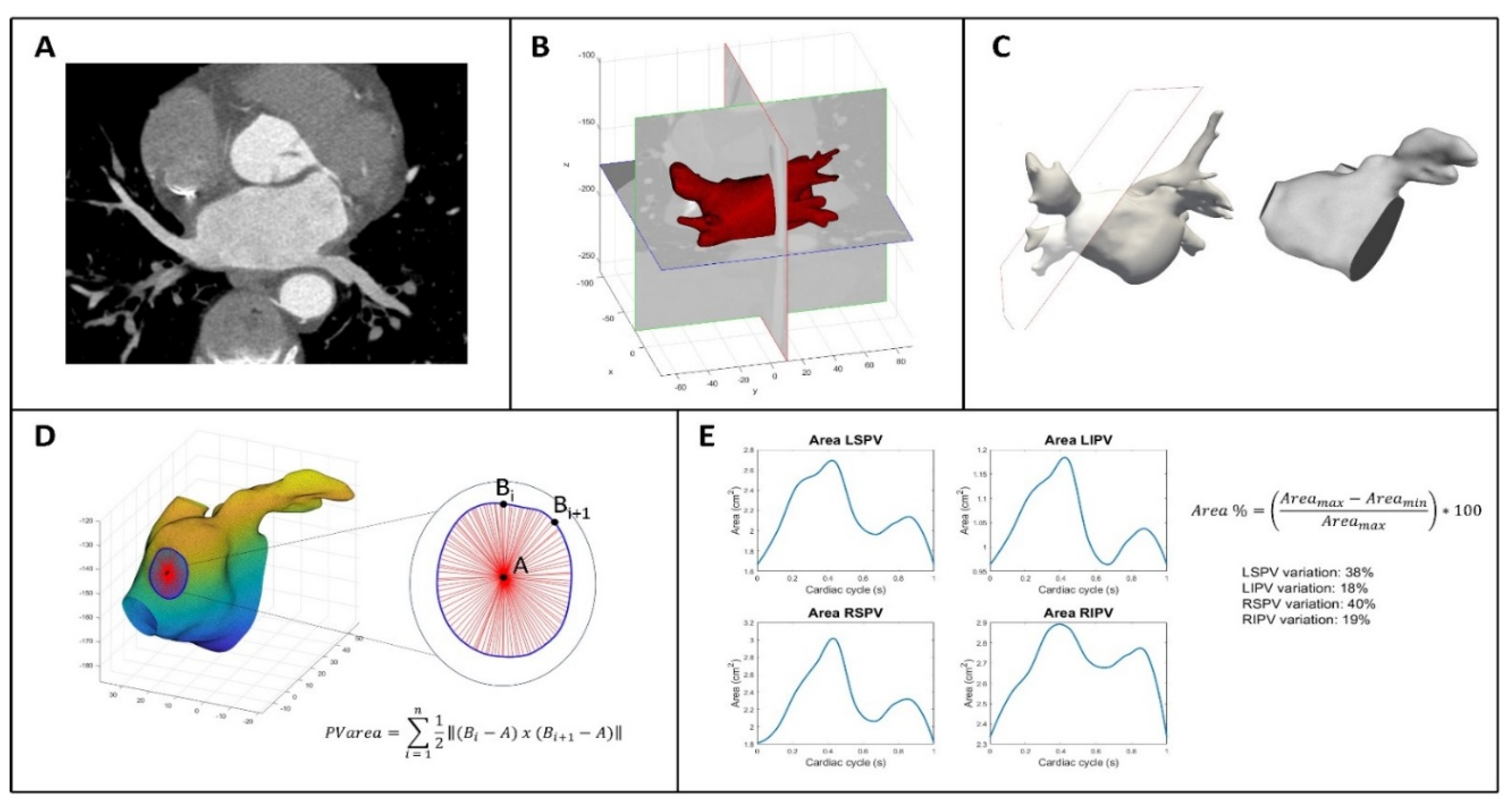

Figure 1 shows the process to analyze CT data and includes several steps that are described in this section. In panel A the first volume acquired for each patient during the cardiac cycle was segmented using an active contour algorithm featured on ITK-SNAP (version 3.8.0, Kitware Inc.). This algorithm initially focused on segmenting the LA including left atrial appendage (LAA) by defining a region of interest. The operator manually selected a seed, which guided the algorithm to grow towards the LA wall and enclose the entire LA anatomy, including the LAA. In order to improve the initial segmentation, its contour was regularized and smoothed using morphological operators and a Laplacian filter, respectively. Finally, the result was exported as a stereolithography file. This entire procedure was executed solely on the first obtained volume of each dynamic dataset. Through the use of Paraview (version 5.10.1, Kitware Inc.), cut planes were applied to delineate the ostia of the PVs. These planes were positioned in accordance with the anatomical ostia of the veins (Panel B and C). Because the cut alters the structure of the surface faces by removing portions of them and attached nodes, the entire surface was remeshed so that the newly established boundaries had new nodes. This was necessary to improve the performance and, consequently, the result of the next step. First, a rigid transformation was applied for an initial alignment, and then subsequently transitioned to an affine registration. The result has been further refined applying a 3D non-rigid registration based on a B-spline transformation model with the mean square difference as cost function (9,10). The dynamic surfaces were now accessible for additional investigation for each dataset. Matlab was used to calculate the area of the PVs by loading the whole dynamic dataset of surfaces for each patient. To do so, the barycenter of each boundary was employed as a reference, as shown in Panel D. The applied formula is simply the area of the triangle as the sum of all triangles inside the boundary:

P V area = ∑ 12 ‖(

Bi −

A)

x (

Bi+1 −

A)‖

ni = 1 where A is the barycenter of the corresponding PV and B are the points on the boundary. This formula is applied iteratively for each PV. The final result is a PV area curve that represent the entire cardiac cycle for each patient. An example is shown in Panel E. In addition, the percentage area variation of each PV is calculated as follows:

Area % = (

Area max −

Area min /

Area max) ∗ 100.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean value ±standard deviation and categorical variables as percentages. For continuous variables ANOVA was used to test differences among groups.

Results

The mean age of the population was 60±10 years, Males 76%. PER were significantly older (normal 57±9 years, PAR 58±10 years, PER 65±8 years, p=0.03). AF patients had significantly larger CT scan measured left atrial volumes (normal 52.1±16.4 ml/m2, PAR 62.8±11.7 ml/m2, PER 73.5±15.2 ml/m2, p=0.002).

Table 1 shows the percentage area changes in the PVs ostia within the single groups, the superior PVs had a significantly higher percentage area changes compared to the inferior inferior (normal p=0.007, PAR-AF p=0.0003 and PER-AF p=0.04) in all groups. As shown in

Table 2 PVs ostia areas did not differ among the three groups for LSPV (p=0.75), RSPV (p=0.6) and RIPV (p=0.71), only LIPVs were significantly smaller in normal subjects compered to PAR-AF and PER-AF (p=0.044). Notably, as shown in

Table 2 percentage changes in ostia area variations were significantly reduced in PAR-AF and PER-AF compared to normal subjects in all PVs (LSPV p< 0.001, RSPV p< 0.001, RIPV p=0.037 and LIPV p< 0.001).

Discussion

Pulmonary veins (PVs) and their atrial junctions are considered thin-walled, highly compliant and mainly passive conduits (11). In normal conditions pulmonary venous blood flow is determined by the pressure gradient between the PVs and the left atrium with a large forward flow during ventricular systole and early diastole and a small reverse flow during atrial systole (11). Early anatomic studies in humans postulated that the myocardial fibers extending around the terminal segment of the PVs may have a putative sphincter-like function preventing the backward flow during atrial contraction (6,8). Pathological studies have established the presence of myocardial sleeves within the pulmonary veins with more prominent extension into the superior veins, in comparison with the inferior veins (6,8). Nathan and Eliakim found that myocardial fibers were often arranged in a circular or ring-like pattern around the pulmonary vein ostia (6). These myocardial sleeves extended at a variable distance within the pulmonary veins with a greater degree of extension in the superior veins (RSPVs 5-25 mm, LSPVs 8-24mm, RIPVs 1-17 mm and LIPVs 1-19 mm) (6). Ho and coll. also confirmed that the greatest extension of myocardium into the pulmonary veins occurred in the superior veins with a maximum length of 25 mm (8). Tan et al. further observed that the muscular architecture at the veno-atrial junction is complex, less developed in the inferior PVs and described three different patterns (12). In pattern 1 PVs sleeves and LA muscle are disconnected, whereas in pattern 2 and 3 there are uninterrupted connection with different myocyte orientation between PVs sleeves and LA muscle (12). Gurfinkel’ et al. recorded the pressure curves in the PVs and in the left atrium in patients with mitral stenosis before and after mitral valvulotomy (7). Analysing the pressure curves the authors suggested the presence of a sphincterial activity of the PVs that failed to operate when the mean pressure in the LA exceeded 20 mm Hg (7). This activity protected the pulmonary vessels from the back pressure wave by blocking the reverse flow (7). With increased pressure in the LA, insufficiency of the pulmonary vein sphincterial activity provoked changes in the small pulmonary vessels, which had the effect of increasing the resistance to blood flow (7). During atrial fibrillation, the PVs sphincterial activity became ineffectual even when the pressure in the LA was moderately raised below 20 mmHg, promoting a relatively early rise of pulmonary vascular resistance (7). We developed this anatomical dynamic model to segment the PVs ostia derived from contrast enhanced CT scan to evaluate non invasively this putative sphincter-like function in a group of healthy subjects without AF and in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF referred for PVs AF cryo-balloon ablation. Our data corroborate early observations by Thiagalingam et al. (13) and Cronin et al. (14) that the behaviour of the PVs ostia cannot be linked only to passive phenomena derived from changes in blood flow. An active contraction of these muscular sleeves in response to the passive distension determined by flow and probably partly driven by Frank– Starling like mechanism has to be considered. In fact, despite the absence of significant differences in the absolute ostial area values among groups, there are significant differences in the area variations between the superior PVs and the inferior ones in which the muscular component is less represented. Moreover, the progressive reduction of PVs ostia area variations in subjects with more advanced AF compared to controls, supports the concept of an active muscular sphincterial activity which is worsened by the well-known atrial myopathy (15) related to AF confirming the previous observations (7). Preserving this sphincterial activity over time, being the PVs without anatomical valves, protects the pulmonary vasculature to an increased in pressure during the entire life.

We have to recognize various limitations of this study. First, the inability to categorize the anatomical pattern of venous-atrial junction, therefore we cannot discriminate the relative contribution to this mechanical activity of the atrial and PVs muscular components. Second, the lack of direct measurement of PVs flow during the cardiac cycle did not allow to quantify the real differences in backward volume flow among the three groups. Third we selected only patients with normal four PVs anatomy therefore we cannot extent our results to other complex anatomical variants of PVs.

In conclusion in this pilot study we developed this 3D anatomical dynamic reconstruction of PVs ostia derived from CT scan acquisition that allows an accurate visualization of the morphology of the PVs, a precise identification of the atrial-venous junction and the evaluation of the dynamic variation of the PVs ostia during the entire cardiac cycle. This sphincter-like activity seems to be particularly evident at the superior compared to the inferior PVs junction and is partially and progressively impaired in AF patients. The impairment of this sphincterial mechanism may have a relevant role in various pathological conditions being the PVs ostia without anatomical valve able to prevent backward flow during atrial contraction.

References

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D’Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004 Aug 31;110(9):1042-6. Epub 2004 Aug 16. PMID: 15313941. [CrossRef]

- Heeringa J, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Kors JA, van Herpen G, Stricker BH, Stijnen T, Lip GY, Witteman JC. Prevalence, incidence and lifetim risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27: 949–953.

- Vinter N, Cordsen P, Johnsen SP, Staerk L, Benjamin EJ, Frost L, Trinquart L. Temporal trends in lifetime risks of atrial fibrillation and its complications between 2000 and 2022: Danish, nationwide, population based cohort study. BMJ. 2024 Apr 17;385:e077209. PMID: 38631726; PMCID: PMC11019491. [CrossRef]

- Jais P, Haissaguerre M, Shah DC, et al. A focal source of atrial fibrillation treated by discrete radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 1997; 95: 572–576.

- Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339: 659–666. [CrossRef]

- Nathan H, Eliakim M. The junction between the left atrium and the pulmonary veins. An anatomic study of human hearts. Circulation. 1966;34(3):412–422. [CrossRef]

- Gurfinkel’, V.S., Kapuller, L.L. & Shik, M.L. Sphincters of the pulmonary veins in man, and their significance. Bull Exp Biol Med 51, 651–653 (1961). [CrossRef]

- Ho SY, Cabrera JA, Tran VH, et al. Architecture of the pulmonary veins: relevance to radiofrequency ablation. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2001;86(3):265–270. [CrossRef]

- Unser M, “Splines: A perfect fit for signal and image processing,” IEEE Signal Process. Mag., 1999;16(6): 22–38. [CrossRef]

- Masci A, Alessandrini M, Forti D, Menghini F, Dedé L, Tomasi C, Quarteroni A, Corsi C. A Proof of Concept for Computational Fluid Dynamic Analysis of the Left Atrium in Atrial Fibrillation on a Patient-Specific Basis. J Biomech Eng. 2020 Jan 1;142(1):011002。 PMID: 31513697. [CrossRef]

- Klein AL, Tajik AJ. Doppler assessment of pulmonary venous flow in healthy subjects and in patients with heart disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1991;4:379-92. [CrossRef]

- Tan AY, Li H, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Chen LS, Chen PS, Fishbein MC. Autonomic innervation and segmental muscular disconnections at the human pulmonary vein-atrial junction: implications for catheter ablation of atrial-pulmonary vein junction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:132-43.

- Thiagalingam A, Reddy VY, Cury RC, Abbara S, Holmvang G, Thangaroopan M, Ruskin JN, d’Avila A. Pulmonary vein contraction: characterization of dynamic changes in pulmonary vein morphology using multiphase multislice computed tomography scanning. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1645-50. [CrossRef]

- Cronin P, Kelly AM, Desjardins B, Patel S, Gross BH, Kazerooni EA, et al. Normative Analysis of pulmonary vein drainage patterns on multidetector CT with measurements of pulmonary vein ostial diameter and distance to first bifurcation. Acad Radiol. 2007;14(2):178–188. [CrossRef]

- Hirsh BJ, Copeland-Halperin RS, Halperin JL. Fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and thromboembolism: mechanistic links and clinical inferences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2239– 2251.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).