Submitted:

14 August 2024

Posted:

15 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Overview

2.1. Export-Led Growth and Regional Trade Flow Sustainability

2.2. Gravity Model and Its Modifications

3. Materials and Methods

| Scale | Russian Federation Date Export (1000 USD) |

Russian Federation`s GDP per capita (USD) |

Russian federation`s GDP (Million USD) |

GDP of Importing Countries (Million USD) |

GDP per capita of Importing Countries (USD) | Distance, kilometer | Russian federation`s Population (Million) | Population of Importing Countries (Million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expijtср | GDP_Rus | GDPpartner | Dist | Pop_RUS | Pop_Partner | |||

| Average | 116779.83 | 10205.85 | 1482893.42 | 391021.81 | 5246.00 | 5150.9 | 144.09 | 79.93 |

| Max | 3358283.00 | 15941.45 | 2292470.08 | 17881783.39 | 53707.98 | 12666.63 |

145.45 | 1412.36 |

| Min | 0.01 | 5910.17 | 345470.49 | 1396.56 | 255.10 | 1644.86 | 142.74 | 2.40 |

| Standard deviation | 308078.55 | 3902.33 | 567907.56 |

1699256.49 | 7812.88 | 2715.49 | 0.95 | 220.39 |

3.1. Traditional Factors

3.2. Structural Trade Barriers

3.3. Policy-Induced Trade Barriers

3.4. Gravity Model

4. Results

4.1. Gravity Model of Russian Grain Exports

4.1.1. Panel Cross-Section Dependence Test

4.1.2. Gravity Results

4.1.2. Analysis of Regression Results

- Importer demand plays a crucial role in increasing grain exports (0.446). The coefficient for this explanatory variable indicates that for every 1% increase in the logarithm of grain demand by a trading partner, the volume of exports from Russia could increase by 0.144%. This underscores the significance of rising consumer demand in bilateral grain trade.

- Geographical distance is important but not decisive for bilateral grain trade (-0.185). The farther the country, the more complex and expensive the logistics. This can be critical for food products, which are essential for all population categories, including the poor. A 1% increase in the logarithm of distance results in a 0.185% decrease in the volume of grain exports from Russia.

- Differences in population size are significant for increasing export volumes. The positive sign of the variable indicates that the smaller the population of the importing country compared to Russia's population, the greater Russia's ability to meet the grain needs of the importing country. A population difference coefficient of 0.101 suggests that a 1% increase in the population gap between Russia and the importing country leads to a 0.101% increase in the logarithm of export volumes.

- The ad valorem tariff negatively impacts grain exports (-0.066). Tariffs serve as a tool for state regulation of domestic market prices. Higher tariffs reduce import volumes, as observed in the model. A 1% increase in the logarithm of ad valorem tariffs results in a 1% decrease in grain imports.

- The level of economic openness of the trading partner is quite significant, with a coefficient of 0.024. Economic openness reflects a country’s commitment to globalization and involvement in external relations. An open economy typically has mechanisms for establishing trade and economic relations with external partners. An increase of 1% in the economic openness variable results in a 0.024% increase in grain exports.

4.2. Trade Potential Estimations

| Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Benin, Brunei Darussalam, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Canada, Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, Congo, DR Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Guinea, Haiti, , Hungary , Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Republic of Korea, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, State of, Lithuania, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mexico, Moldova, Republic of, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Norway, Oman, Palestine, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Singapore, Slovenia, Somalia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Sweden, Switzerland, Syrian Arab Republic, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Tunisia, Türkiye, Turkmenistan, Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of, Viet Nam, Yemen, Zimbabwe | Andorra, Argentina, Bermuda, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Cambodia, Chad, Costa Rica, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eswatini, Greenland, Grenada, Honduras, Hong Kong, China, Iceland, Jamaica, Lesotho, Luxembourg, North Macedonia, New Zealand, Niger, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, South Sudan, Suriname, Uruguay, Zambia, | Bangladesh, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, United States of America |

4.3. The Most Competitive Russian Regions in Cereal Exports: RCA Estimations

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Expfact mln doll | Exppotential mln doll | Expfact | Expfact mln doll | Exppotential mln doll |

| Afghanistan | 10,638.0 | 323.8 | Kenya | 9,669.6 | 1,079.3 |

| Albania | 14,355.5 | 94.4 | Korea. Democratic People's Republic of | 11,986.3 | 43.5 |

| Algeria | 11,568.3 | 3,298.3 | Korea. Republic of | 11,699.5 | 5,227.4 |

| Andorra | 14,589.6 | 0.8 | Kuwait | 14,425.5 | 592.3 |

| Angola | 11,315.2 | 584.9 | Kyrgyzstan | 13,935.3 | 72.9 |

| Argentina | 9,967.2 | 48.7 | Latvia | 14,528.7 | 276.9 |

| Armenia | 14,361.5 | 106.7 | Lebanon | 14,203.5 | 372.4 |

| Australia | 12,086.2 | 266.2 | Lesotho | 14,384.0 | 48.0 |

| Austria | 14,038.5 | 791.8 | Liberia | 14,156.3 | 206.3 |

| Azerbaijan | 13,757.9 | 413.9 | Libya. State of | 14,127.9 | 485.7 |

| Bahrain | 14,500.4 | 121.2 | Lithuania | 14,379.1 | 153.9 |

| Bangladesh | -1,602.8 | 2,232.2 | Luxembourg | 14,561.5 | 70.6 |

| Belarus | 13,700.9 | 93.4 | Macedonia. North | 14,613.1 | 39.4 |

| Belgium | 14,653.6 | 2,770.6 | Madagascar | 14,732.8 | 310.5 |

| Benin | 13,535.3 | 608.5 | Malawi | 14,617.2 | 50.9 |

| Bermuda | 14,588.7 | 1.6 | Malaysia | 12,181.6 | 2,234.2 |

| Bhutan | 14,535.9 | 44.3 | Mali | 12,453.4 | 238.3 |

| Bolivia. Plurinational State of | 13,382.6 | 37.9 | Malta | 14,557.4 | 34.8 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 14,330.2 | 142.9 | Mauritania | 14,241.2 | 266.7 |

| Botswana | 14,401.6 | 159.3 | Mexico | 5,086.2 | 7,479.9 |

| Brazil | -5,918.0 | 2,656.1 | Moldova. Republic of | 14,354.9 | 40.9 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 14,565.9 | 37.6 | Mongolia | 14,282.5 | 63.0 |

| Bulgaria | 13,988.8 | 151.6 | Montenegro | 14,538.2 | 11.5 |

| Burkina Faso | 12,417.7 | 188.3 | Morocco | 12,097.7 | 2,839.5 |

| Burundi | 13,326.7 | 38.6 | Mozambique | 11,588.7 | 628.0 |

| Cabo Verde | 14,566.7 | 41.5 | Namibia | 14,386.4 | 110.8 |

| Cambodia | 12,944.2 | 75.9 | Nepal | 11,781.1 | 531.4 |

| Cameroon | 12,070.3 | 583.2 | Netherlands | 14,569.9 | 3,937.1 |

| Canada | 11,334.6 | 1,483.4 | New Zealand | 14,205.7 | 295.1 |

| Central African Republic | 14,041.8 | 12.6 | Nicaragua | 14,015.0 | 264.7 |

| Chad | 12,835.4 | 8.1 | Niger | 12,187.0 | 432.3 |

| Chile | 13,316.9 | 1,555.6 | Nigeria | -6,186.8 | 2,323.7 |

| China | -12,0252.1 | 17,316.7 | Norway | 14,126.0 | 179.3 |

| Colombia | 10,562.3 | 2,646.2 | Oman | 14,438.8 | 684.5 |

| Congo | 14,056.0 | 129.4 | Pakistan | -8,594.9 | 933.4 |

| Congo. Democratic Republic of the | 4,841.9 | 213.7 | Palestine. State of | 14,635.2 | 89.4 |

| Costa Rica | 14,287.8 | 484.0 | Panama | 14,271.9 | 270.1 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 12,224.6 | 988.5 | Papua New Guinea | 13,694.1 | 257.4 |

| Croatia | 14,254.4 | 120.3 | Paraguay | 13,952.0 | 88.2 |

| Cuba | 13,701.3 | 543.8 | Peru | 12,037.0 | 1,934.7 |

| Cyprus | 14,540.8 | 160.1 | Philippines | 4,621.9 | 3,624.3 |

| Czech Republic | 13,620.5 | 234.0 | Poland | 11,173.6 | 771.4 |

| Denmark | 14,109.7 | 243.2 | Portugal | 14,094.6 | 1,236.1 |

| Djibouti | 14,619.8 | 307.8 | Qatar | 14,435.9 | 257.5 |

| Dominican Republic | 13,750.6 | 638.2 | Romania | 13,036.2 | 834.1 |

| Ecuador | 13,052.7 | 597.1 | Rwanda | 13,292.4 | 164.4 |

| Egypt | 6,318.4 | 6,376.8 | Saudi Arabia | 12,761.7 | 4,115.3 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 14,605.0 | 23.0 | Senegal | 13,260.3 | 880.2 |

| Eritrea | 14,238.5 | 27.6 | Serbia | 13,937.7 | 54.5 |

| Estonia | 14,472.6 | 28.2 | Sierra Leone | 13,800.1 | 146.4 |

| Eswatini | 14,512.7 | 84.4 | Singapore | 14,179.0 | 353.5 |

| Ethiopia | 2,786.7 | 1,116.9 | Slovakia | 14,121.9 | 170.2 |

| Finland | 14,070.7 | 80.2 | Slovenia | 14,438.4 | 125.6 |

| France | 8,250.8 | 1,143.8 | Somalia | 12,953.8 | 246.5 |

| Gabon | 14,414.4 | 131.3 | South Africa | 9,086.3 | 1,153.6 |

| Gambia | 14,351.0 | 58.9 | South Sudan | 13,516.7 | 36.7 |

| Georgia | 14,269.4 | 112.4 | Spain | 12,052.3 | 5,107.8 |

| Germany | 7,937.7 | 4,017.5 | Sri Lanka | 12,574.5 | 469.1 |

| Ghana | 11,443.3 | 441.9 | Sudan | 10,153.8 | 520.3 |

| Greece | 13,793.5 | 582.8 | Suriname | 14,550.7 | 10.5 |

| Greenland | 14,589.7 | 0.8 | Sweden | 13,616.0 | 169.5 |

| Grenada | 14,586.8 | 5.5 | Switzerland | 13,883.7 | 383.8 |

| Guatemala | 13,194.2 | 764.0 | Syrian Arab Republic | 12,454.2 | 150.0 |

| Guinea | 13,394.7 | 411.3 | Tajikistan | 13,740.6 | 313.5 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 14,401.1 | 37.8 | Tanzania. United Republic of | 8,236.8 | 364.3 |

| Guyana | 14,530.9 | 40.8 | Thailand | 8,011.1 | 1,463.1 |

| Haiti | 13,594.9 | 367.5 | Togo | 13,748.8 | 84.2 |

| Honduras | 13,715.6 | 376.1 | Tunisia | 13,937.1 | 1,311.9 |

| Hong Kong. China | 13,963.5 | 270.8 | Türkiye | 8,069.2 | 4,493.4 |

| Hungary | 13,841.0 | 498.7 | Turkmenistan | 13,995.4 | 100.5 |

| Iceland | 14,587.5 | 27.3 | Uganda | 10,067.8 | 385.3 |

| India | -128,016.3 | 100.5 | Ukraine | 10,547.4 | 154.3 |

| Indonesia | -11,195.0 | 4,375.9 | United Arab Emirates | 14,224.2 | 1,297.6 |

| Iran. Islamic Republic of | 8,249.7 | 5,753.3 | United Kingdom | 8,687.0 | 2,052.3 |

| Iraq | 10,808.7 | 1,478.9 | United States of America | -17,692.8 | 3,003.7 |

| Ireland | 14,332.9 | 566.9 | Uruguay | 14,294.6 | 105.8 |

| Israel | 14,134.7 | 1,112.7 | Uzbekistan | 11,360.2 | 740.7 |

| Italy | 10,784.9 | 4,832.6 | Venezuela. Bolivarian Republic of | 12,045.8 | 731.0 |

| Jamaica | 14,402.0 | 209.2 | Viet Nam | 6,843.1 | 4,765.3 |

| Japan | 5,399.8 | 7,780.9 | Yemen | 13,205.7 | 1,356.7 |

| Jordan | 13,915.7 | 1,006.6 | Zambia | 11,246.8 | 47.1 |

| Kazakhstan | 12,774.2 | 303.5 | Zimbabwe | 13,142.5 | 404.7 |

References

- Wang, G.; Li, B.; Liu, X. Evolution of global grain trade network and supply risk assessment based on complex network. New Medit 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Wu, J. Temporal and spatial evolution of global major grain trade patterns. J Integr Agric 2024, 23(03), 1075. [CrossRef]

- Kibik, O.; Kovyrkina, O. The logistics component in the export activity management system of grain traders under global uncertainty. Development of management and governance methods in transport 2023, 2(83), pp. 107–117. [CrossRef]

- Çakır, F. S.; Zehir, S. Y.; Adıgüzel, Z. Examination of the effects of logistics capabilities and learning orientation on financial and growth performance and export performance in export-oriented companies. Uluslararası Yönetim İktisat ve İşletme Dergisi 2022, 18(4), pp. 1089-1109. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Tong, G. The State of Grain Trade between China and Russia: Analysis of Growth Effect and Its Influencing Factors. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1407. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, P.; Khan, Z. A.; Wei, F. Potential of Kazakhstan’s grain export trade. Ciência Rural 2021, 52(1), e20210199. [CrossRef]

- Novikov, Yu.; Baetova, D. Grain export as a factor of sustainable development of rural territories of the Omsk region. Food Processing Technology 2018, 48(3), pp. 50–57. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Taipov, T.; Kantarbayeva, S.; Khan, V. Kazakhstan: Transport and Logistical Risks in Grain Export. Valery, Kazakhstan: Transport and Logistical Risks in Grain Export (June 20, 2017). [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D. F. Too Many Assumptions Researching Grain Markets in Tanzania. Inducing Food Insecurity: Perspectives on Food Policies in Eastern and Southern Africa 1994, 30, 145.

- Syzdykova, A.O.; Azretbergenova, G. Grain exports of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Problems of AgriMarket 2020, 4, pp. 63-69. [CrossRef]

- Kepaptsoglou, K.; Karlaftis, M. G.; Tsamboulas, D. The gravity model specification for modeling international trade flows and free trade agreement effects: a 10-year review of empirical studies. The open economics journal 2010, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. Evaluation of International Import and Export Complexity Based on Trade Gravity model. In International Conference on Data Science and Network Security (ICDSNS), Tiptur, India, 2023, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.A.; Smith, S.L.S. Canadian provinces in world trade: engagement and detachment. The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue Canadienne d’Economique 1999, 32(1), pp. 22–38. [CrossRef]

- Melchior, A. Globalisation and the provinces of China: the role of domestic versus international trade integration. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 2010, 8(3), pp. 227-252. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, S.; Hu, X. Temporary extra-regional linkages and export product and market diversification. Regional Studies 2023, 57(8), pp. 1578-1591. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.; Leichenko, R. M. Regional income inequality and international trade. Economic Geography 2004, 80(3), pp. 261-286. [CrossRef]

- Maschke, A. Exporting unemployment? Assessing the impact of German import competition on regional manufacturing employment in France. Regional Studies 2024, 58(3), pp. 455-468. [CrossRef]

- Biles, J.J. Export-oriented industrialization and regional development: a case study of maquiladora production in Yucatán, Mexico. Regional studies 2004, 38(5), pp. 517-532. [CrossRef]

- Mance, D.; Debelić, B.; Vilke, S. Croatian Regional Export Value-Added Chains. Economies 2023, 11, 202. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, X. Regional Inequality of Firms’ Export Opportunity in China: Geographical Location and Economic Openness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9. [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.M. Exports, employment, and production: A causal assessment of US states and regions. Economic Geography 2000, 76(4), pp. 303-325. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, O.; Drewes, E.; van Aswegen, M.; Malan, G. A Policy Approach towards Achieving Regional Economic Resilience in Developing Countries: Evidence from the SADC. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2674. [CrossRef]

- Carmo, A.S.S.D.; Raiher, A.P.; Stege, A.L. O efeito das exportações no crescimento econômico das microrregiões brasileiras: uma análise espacial com dados em painel. Estudos Econômicos (São Paulo) 2017, 47(1), pp. 153-183. [CrossRef]

- Fedyunina, A.A.; Simachev, Yu.V.; Drapkin, I.M. Intensive and extensive margins of export: determinants of economic growth in Russian regions under sanctions. Ekonomika regiona / Economy of regions 2023, 19(3), pp. 884-897. [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Taylor, L. Economic growth in foreign regions and US export growth. Economic Review-Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City 2013, pp. 31–63.

- Naudé, W.; Bosker, M.; Matthee, M. Export specialisation and local economic growth. World Economy 2010, 33(4), pp. 552–572. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Waheed, A. Pakistan’s potential export flow: The gravity model approach. The Journal of Developing Areas 2015, 49(4), pp. 367–378. [CrossRef]

- Black, A.; Edwards, L.; Ismail, F.’; Makundi, B.; Morris, M. Spreading the gains?: Prospects and policies for the development of regional value chains in Southern Africa. WIDER Working Paper 2019/48. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. [CrossRef]

- Istaiteyeh, R.; Najem, F.; Saqfalhait, N. Exports- and Imports-Led Growth: Evidence from a Time Series Analysis, Case of Jordan. Economies 2023, 11, 135. [CrossRef]

- Black, A.; Edwards, L.; Ismail, F.; Makundi, B.; Morris, M. The role of regional value chains in fostering regional integration in Southern Africa. Development Southern Africa 2021, 38(1), pp. 39–56. [CrossRef]

- Vokony, I.; Sőrés, P.; Németh, B.; Hartmann, B. Market design for cross-border co-optimised energy-reserve allocation. In 21th International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ’23), Madrid, Spain, 24th to 26th May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cont, W.; Barril, D.; Carbó, A. Electricity trade in South America: An analysis based on the gravity equation. Asociación Argentina de Economía Política 2021, 4456. [CrossRef]

- Baier, S.; Standaert, S. Gravity models and empirical trade. In Oxford research encyclopedia of economics and finance 2020. Retrieved 12 Aug. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-327.

- Sinaga, A.M.; Masyhuri, D.D.H.; Widodo, S. Employing gravity model to measure international trade potential. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 546(5), 052072. IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Alamri, Y.A.; Alnafissa, M.A.; Kotb, A.; Alagsam, F.; Aldakhil, A.I.; Alfadil, I.E.; Al-Qunaibet, M.H.; Alaagib, S. Estimating the Expected Commercial Potential of Saudi Date Exports to Middle Eastern Countries Using the Gravity Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2552. [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M. S.; Xin, Q.; Arshad, H.; Aye, G. Competitiveness of Pakistani rice in international market and export potential with global world: A panel gravity approach. Cogent Economics & Finance 2018, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Qin, K.; Jia, T.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, X. Modeling the Interactive Patterns of International Migration Network through a Reverse Gravity Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2502. [CrossRef]

- Groznykh, R.I.; Mariev, O.S. Impact of institutional factors on foreign direct investment inflows: Crosscountry analysis. Zhurnal Economicheskoj Teorii [Russian Journal of Economic Theory] 2019, 16(2), pp. 305–311. [CrossRef]

- Dadakas, D.; Ghazvini Kor, S.; Fargher, S. Examining the trade potential of the UAE using a gravity model and a Poisson pseudo maximum likelihood estimator. J Int Trade Econ Dev 2020, 29(5), pp. 619–646. [CrossRef]

- Coşkuner, Ç.; Sogah, R. Augmented Gravity Model of Trade with Social Network Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14085. [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.D.; Hoff, P.D. Persistent patterns of international commerce. J Peace Res 2007, 44(2), pp. 157–175. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Algorithm analysis of trade gravity model based on PageRank algorithm. In International Conference on Electronics and Devices, Computational Science (ICEDCS), Marseille, France, 2023, pp. 201-204. [CrossRef]

- Bikker, J.A. An international trade flow model with substitution: an extension of the gravity model. Kyklos 1987, 40(3), pp. 315–337. [CrossRef]

- Prastuti, G.; Permatasari, I.; Satmoko, A.S.A.; Imran, A. Detecting Cross-Border Transaction Patterns Using Machine Learning: The Case of Indonesia. Available at SSRN 4736381. [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.D.; Ahlquist, J.S.; Rozenas, A. Gravity's rainbow: A dynamic latent space model for the world trade network. Network Science 2013, 1(1), pp. 95–118. [CrossRef]

- Ciuriak, D.; Kinjo, S. Trade specialization in the gravity model of international trade. Trade policy research 2006, 2005, pp. 189–197.

- Tinbergen, J. Shaping the world economy: Suggestions for an international economic policy. NY: Twentieth Century Fund, 1962. 330 p.

- Anderson, J.E. A theoretical foundation for the gravity equation. Am Econ Rev 1979, 69(1), pp. 106-116. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1802501.

- Anderson, J.E.; Van Wincoop, E. Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. Am Econ Rev 2003, 93(1), pp. 170-192. [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, J.H. The Gravity Equation in International Trade: Some Microeconomic Foundations and Empirical Evidence. Rev Econ Stat 1985, 67(3), pp. 474–481. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.; Kortum, S. Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica 2002, 70(5), pp. 1741–1779. [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, A.V. Determinants of bilateral trade: does gravity work in a neoclassical world? National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998.

- Helpman, E.; Krugman, P. Market structure and foreign trade: Increasing returns, imperfect competition, and the international economy. MIT press, 1987.

- Helpman, E.; Melitz, M.; Rubinstein, Y. Estimating trade flows: Trading partners and trading volumes. Q J Econ 2008, 123(2), pp. 441–487. [CrossRef]

- Shumilov, A. Estimating gravity models of international trade: A survey of methods. HSE Economic Journal 2017, 21(2), pp. 224–250.

- Vashkevich, Y. Gravity model of international trade: assessing the effectiveness of integration in services sector. The scientific heritage 2021, 74(4), pp. 11-16. [CrossRef]

- Kaukin, A.; Idrisov, G. The gravity model of Russian foreign trade: case of a country with large area and long border. Econ Policy 2013, 4, pp. 133–154.

- Aksenov, G.; Li, R.; Abbas, Q.; Fambo, H.; Popkov, S.; Ponkratov, V.; Kosov, M.; Elyakova, I.; Vasiljeva, M. Development of Trade and Financial-Economical Relationships between China and Russia: A Study Based on the Trade Gravity Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6099. [CrossRef]

- Product nomenclature of the foreign economic activity of the Commonwealth of Independent States (ТН ВЭД СНГ) (based on the 6th edition of the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System). Available online: https://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_133442/ (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Putri, K.D.K.; Darmawan, D.P.; Arisena, G.M.K. Kontribusi sektor perikanan terhadap perekonomian provinsi bali. Jurnal Kebijakan Sosial Ekonomi Kelautan Dan Perikanan 2021, 11(1), pp. 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, M.; Teal, F. Aggregation versus heterogeneity in cross-country growth empirics. CSAE working paper series 2010-32, Centre for the study of African economies, University of Oxford.

- Moscone, F.; Tosetti, E. GMM estimation of spatial panels, MPRA Paper 16327, University Library of Munich, Germany, 2009. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/16327 (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Breusch, T.S.; Pagan, A.R. The Lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. Review of Econometric Studies 1980, 47(1), pp. 239–253. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. General diagnostic tests for cross-sectional dependence in panels. Empir Econ 2021, 60(1), pp. 13–50. [CrossRef]

- Gnidchenko, A.; Salnikov, V. Trade intensity, net trade, and revealed comparative advantage. Higher School of Economics Research Paper 2021, WP BRP, 244. [CrossRef]

- Agapkin, A.M.; Makhotina, I.A. The state of the Russian grain market. International trade and trade policy 2021, 7(3). [CrossRef]

- Shchutskaya, A.V.; Ivanova, E.E. Exports of Russian cereals: analysis of the current state and development prospects. SHS Web of Conferences 2019, 62, 08006. [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Unit of Mesurement | Type | Expected Sign | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenuous variable | ||||

| Expijt_av | US$ 1000 | Time-Variant | - | TradeMap.org, UN Comtrade |

| Traditional Factors | ||||

| GDP_RUS, GDP_Partner |

Current US$ | Time-Variant | Positive | WDI, World Bank |

| (DIST)ijt | Kilometres | Time-Invariant | Negative | CEPII database |

| Natural barriers | ||||

| Demand | US$ 1000 | Time-Variant | Positive | TradeMap.org, UN Comtrade |

| Open_Econ (The degree of openness of the economy) | % | Time-Variant | Positive | World Bank |

| GDP_distance | Per capita Current US$ | Time-Variant | Ambiguous | WDI, World Bank |

| REMOT | Kilometres *US$/US$ | Time-Variant | Negative | CEPII database, WDI, World Bank |

| SCALE (Population Distance) | Population, total | Time-Variant | Ambiguous | World Bank |

| Border | (1/0) | Time-Invariant | Positive | CEPII database, YandexMap |

| Sea | (1/0) | Time-Invariant | Positive | CEPII database, YandexMap |

| Artifical trade barriers | ||||

| Tariff_adv | % | Time-Variant | Negative | WTO |

| TPU (Trade and Political Unions) | (1/0) | Time-Variant | Positive | MID RF |

| Variables | Method | Statistic | Prob. | Cross-Sections | Obs | Lag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnExp_av | Im, Pesaran and Shin W-stat | -3.01172 | 0.0013 | 37 | 740 | 1 |

| lnGDP_RUS | -9.80152 | 0.0000 | 37 | 740 | 1 | |

| lnGDP_Partner | -5.74583 | 0.0000 | 37 | 740 | 1 | |

| lnREMOT | -1.83546 | 0.0332 | 37 | 740 | ||

| lnGDP_dist | -9.09617 | 0.0000 | 37 | 740 | 1 | |

| lnOpen_Econ | -11.5769 | 0.0000 | 37 | 740 | ||

| lnSCALE | -9.07452 | 0.0000 | 37 | 740 | 1 | |

| lnTariff_adv | -3.64509 | 0.0001 | 37 | 620 | ||

| lndem | -4.30717 | 0.0000 | 37 | 740 | 1 |

| Пoказатели | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (Std. Error)/(Prob.) |

Coefficient (Std. Error)/ Prob. |

Coefficient (Std. Error)/ Prob. |

Coefficient (Std. Error)/ Prob. |

Coefficient (Std. Error)/ Prob. |

|

| lnGDP_RUS | 1.755 (0.176)/( 0.000) |

0.175 (0.070)/ 0.012 |

|||

| GDP_Partner | 0.283 (0.054)/ (0.000) |

0.086 (0.001)/ 0.001 |

|||

| Dist | -2.112 (0.164)/( 0.000) |

-0.173 (0.073)/ 0.018 |

-0.185 (0.072)/ 0.010 |

||

| REMOT | -0.302 (0.038)/ 0.390 |

||||

| GDP_dist | 0.039 (0.037)/ 0.302 |

||||

| Open_Econ | 0.022 (0.009)/ 0.023 |

0,025 (0.009)/ 0.009 |

0.024 (0.009)/ 0.011 |

||

| SCALE | 0.129 (0.042)/ 0.002 |

0.084 (0.023)/ 0.000 |

0.101 (0.024)/ 0.000 |

||

| Tariff_adv | -0.046 (0.016)/ 0.005 |

-0.083 (0.016)/ 0.000 |

-0.080 (0.016)/ 0.000 |

-0.066 (0.016)/ 0.000 |

|

| Dem | 0.0440 (0.006)/ 0.000 |

0.452 (0.05)/ 0.272 |

0.451 (0.05)/ 0.000 |

0.446 (0.006)/ 0.000 |

|

| Border | -0.130 (0.110)/0.236 |

-0.04 (0.111)/ 0.783 |

|||

| Sea | -0.263 (0.102)/ 0.010 |

-0.116 (0.105)/ 0.272 |

|||

| Trade and Political Unions | -0.139 (0.100)/ 0.169 |

-0.063 (0.100)/ 0.538 |

|||

| c | -33.997 (4.941) |

-4.194 (1.871)/ 0.025 |

-3.710 (1.515)/ 0.015 |

-1.924 (0.833)/ 0,021 |

-0.999 (0.905)/0.270 |

| R-squared | 0.289 | 0.905 | 0.905 | 0.904 | 0.905 |

| Adjusted R-sguared | 0.287 | 0.904 | 0.904 | 0.903 | 0.904 |

| Indicator | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.E. of regression | 2.512 | 0.923 | 0.924 | 0.924 | 0.0921 |

| F-statistic | 110.12 | 955.820 | 848.099 | 1904.172 | 1535.126 |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Root MSE | 2.506 | 0.918 | 0.918 | 0.922 | 0.918 |

| Mean dependent var | 4.286 | 4.286 | 4.286 | 4.286 | 4.286 |

| S.D. dependent var | 2.975 | 2.975 | 2.975 | 2.975 | 2.975 |

| Akaike info criterion | 4.685 | 2.689 | 2.692 | 2.687 | 2.681 |

| Schwarz criterion | 4.708 | 2.741 | 2.749 | 2.716 | 2.716 |

| Sum squared resid | 5117.502 | 686.756 | 687.096 | 692.283 | 686.707 |

| Durbin−Watson stat | 0.670 | 1.607 | 1.640 | 1.624 | 1.620 |

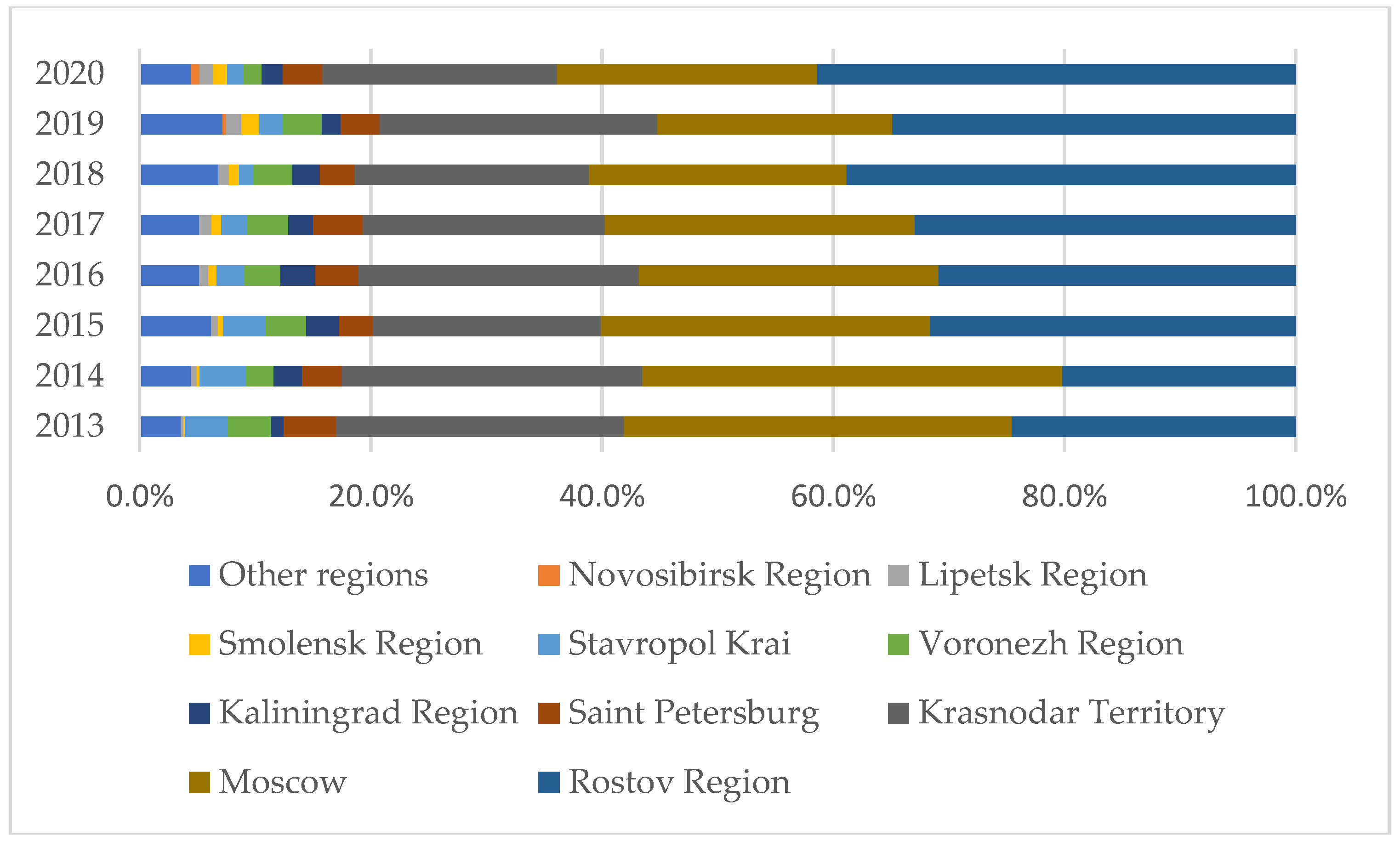

| Russian Subject | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rostov Region | 22.22 | 20.96 | 22.02 | 15.62 | 16.83 | 18.70 | 17.04 | 15.65 |

| Moscow | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Krasnodar Territory | 16.59 | 12.51 | 10.54 | 12.20 | 10.45 | 10.46 | 13.10 | 11.93 |

| Saint Petersburg | 1.07 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.54 |

| Voronezh Region | 12.18 | 7.50 | 8.74 | 7.59 | 9.32 | 9.40 | 11.00 | 4.81 |

| Stavropol Territory | 17.60 | 17.46 | 12.76 | 8.22 | 8.05 | 4.97 | 7.16 | 4.43 |

| Kaliningrad Region | 3.88 | 3.24 | 3.48 | 7.04 | 5.89 | 5.18 | 4.34 | 3.57 |

| Astrakhan Region | 6.46 | 5.79 | 14.39 | 11.47 | 5.67 | 6.85 | 18.84 | 0.00 |

| Lipetsk Region | 0.27 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 1.41 | 1.23 |

| Smolensk Region | 0.42 | 1.06 | 1.64 | 2.08 | 2.58 | 3.12 | 5.29 | 4.02 |

| Volgograd Region | 1.31 | 1.45 | 2.42 | 1.28 | 1.83 | 0.81 | 1.25 | 0.74 |

| Saratov Region | 0.42 | 1.03 | 0.57 | 1.22 | 1.52 | 1.56 | 2.13 | 1.52 |

| Oryol Region | 5.48 | 13.56 | 10.66 | 10.28 | 5.72 | 8.43 | 7.31 | 3.91 |

| Orenburg Region | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 0.64 |

| Omsk Region | 0.00 | 1.08 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.20 | 2.76 |

| Tambov Region | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.36 | 14.79 | 10.75 | 3.23 |

| Kursk Region | 0.00 | 1.04 | 1.99 | 1.69 | 1.65 | 4.63 | 0.00 | 1.19 |

| North Ossetia – Alania | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.16 | 13.22 | 0.00 | 15.84 | 20.77 | 13.96 |

| Primorsky Territory | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.62 |

| Samara Region | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Buryatia | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Chelyabinsk Region | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ulyanovsk Region | 1.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Altai Territory | 0.76 | 1.37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.40 | 1.33 |

| Bashkortostan | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Moscow Region | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Belgorod Region | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ryazan Region | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.18 | 2.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Krasnoyarsk Territory | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sverdlovsk Region | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Omsk Region | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bryansk Region | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.49 | 0.00 |

| Novosibirsk Region | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.78 |

| Chelyabinsk Region | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Russian Federation | 1.37 | 2.23 | 2.62 | 3.24 | 3.56 | 4.01 | 3.18 | 4.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).