Submitted:

14 August 2024

Posted:

15 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bibliometric Research Methodology

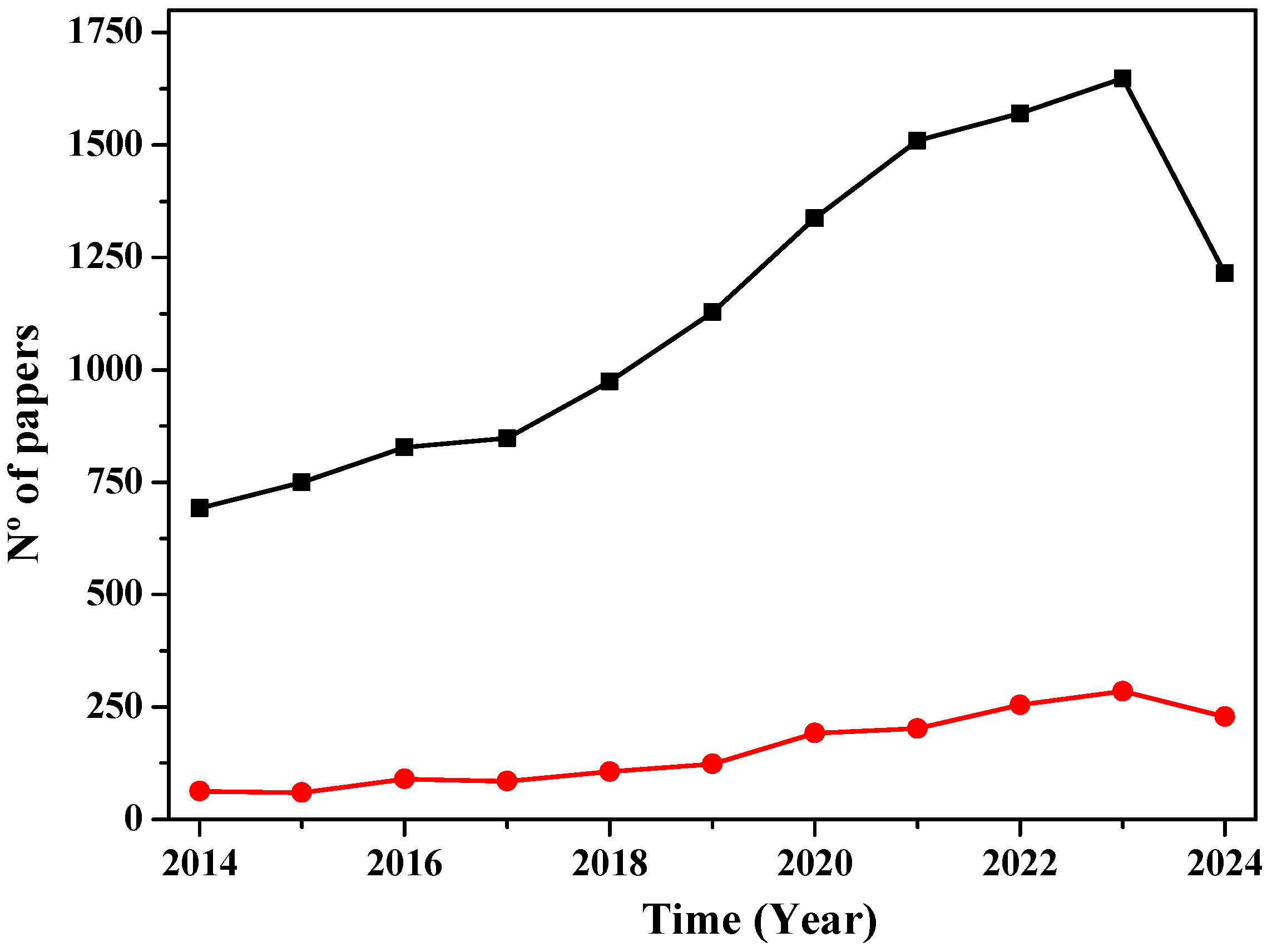

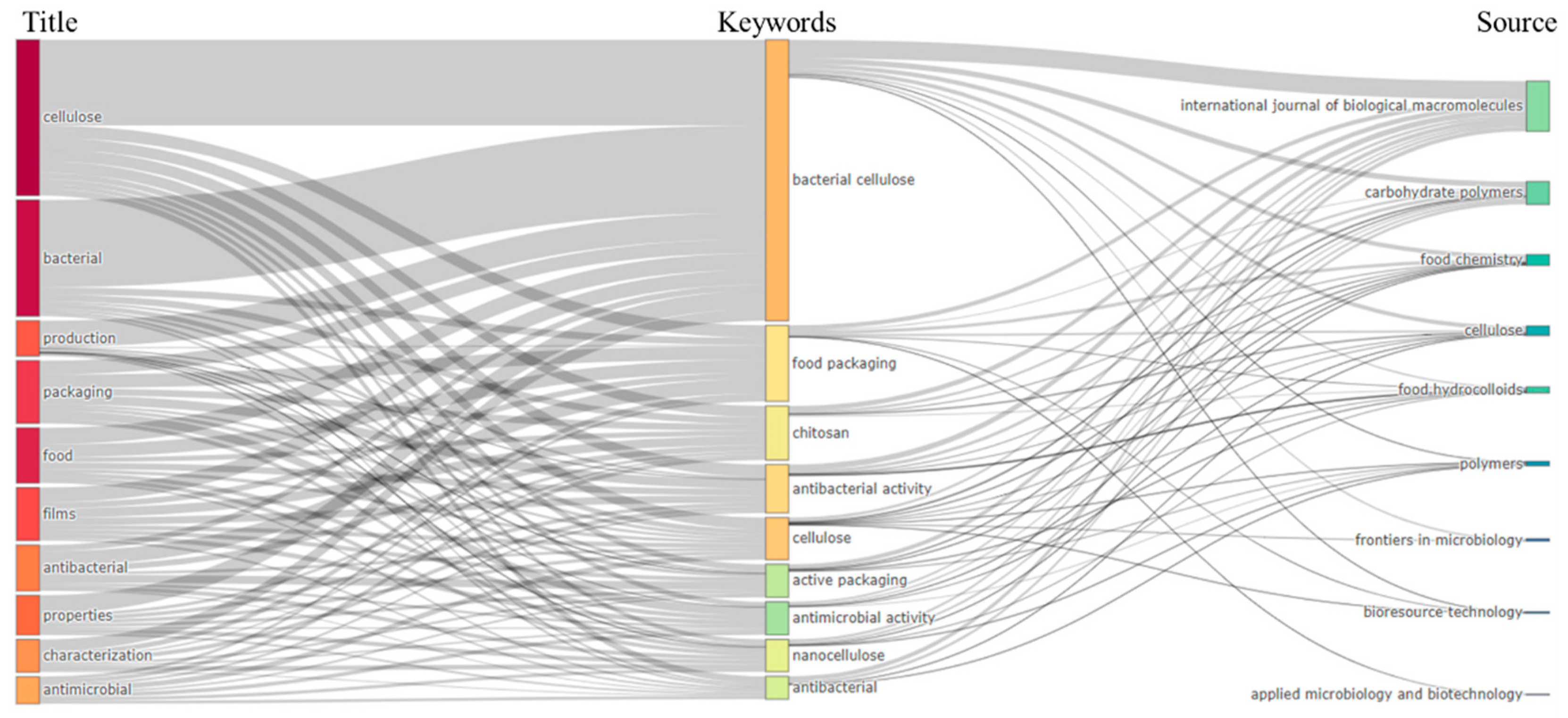

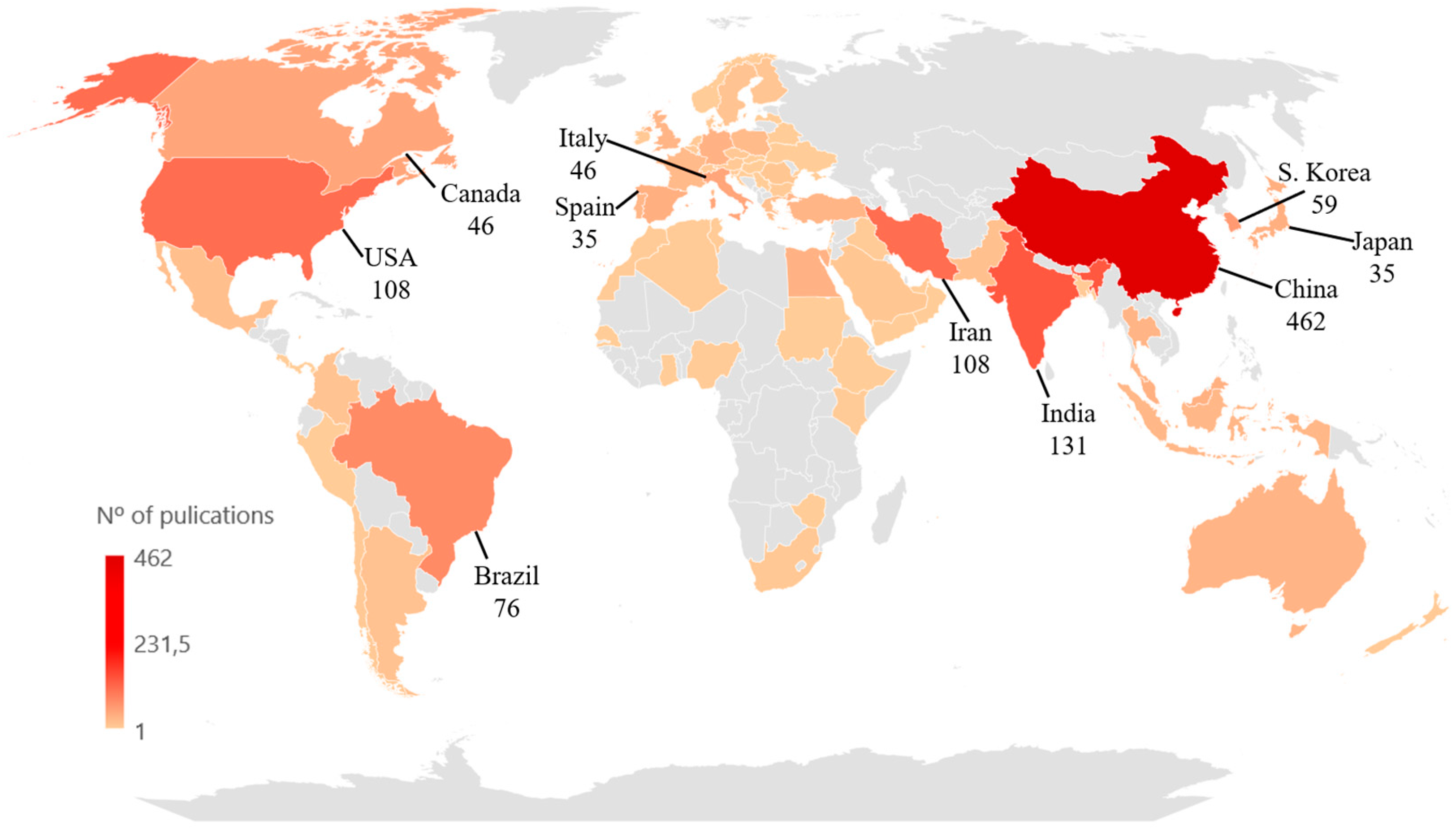

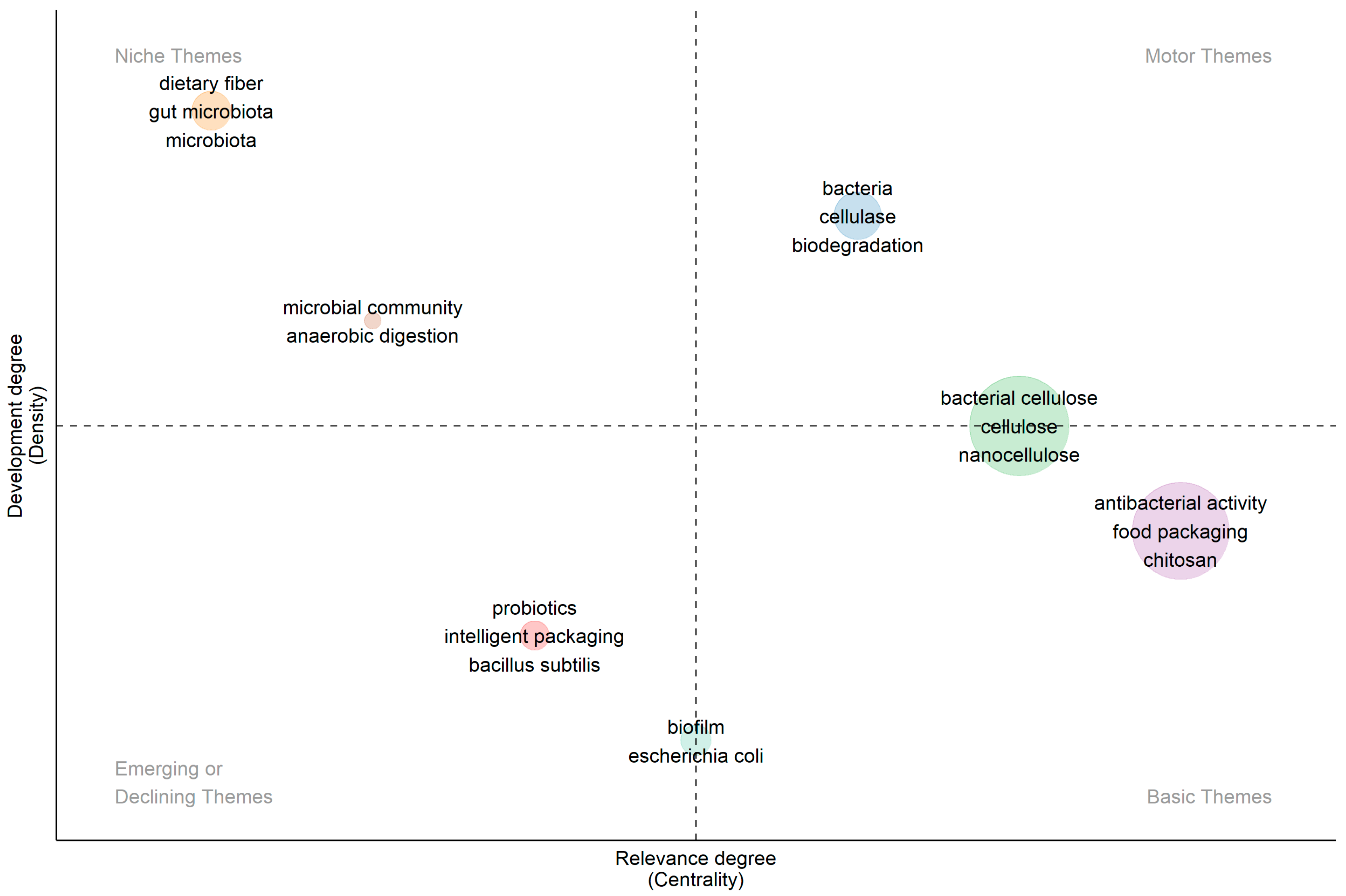

3.1. Defining the Scope of Research

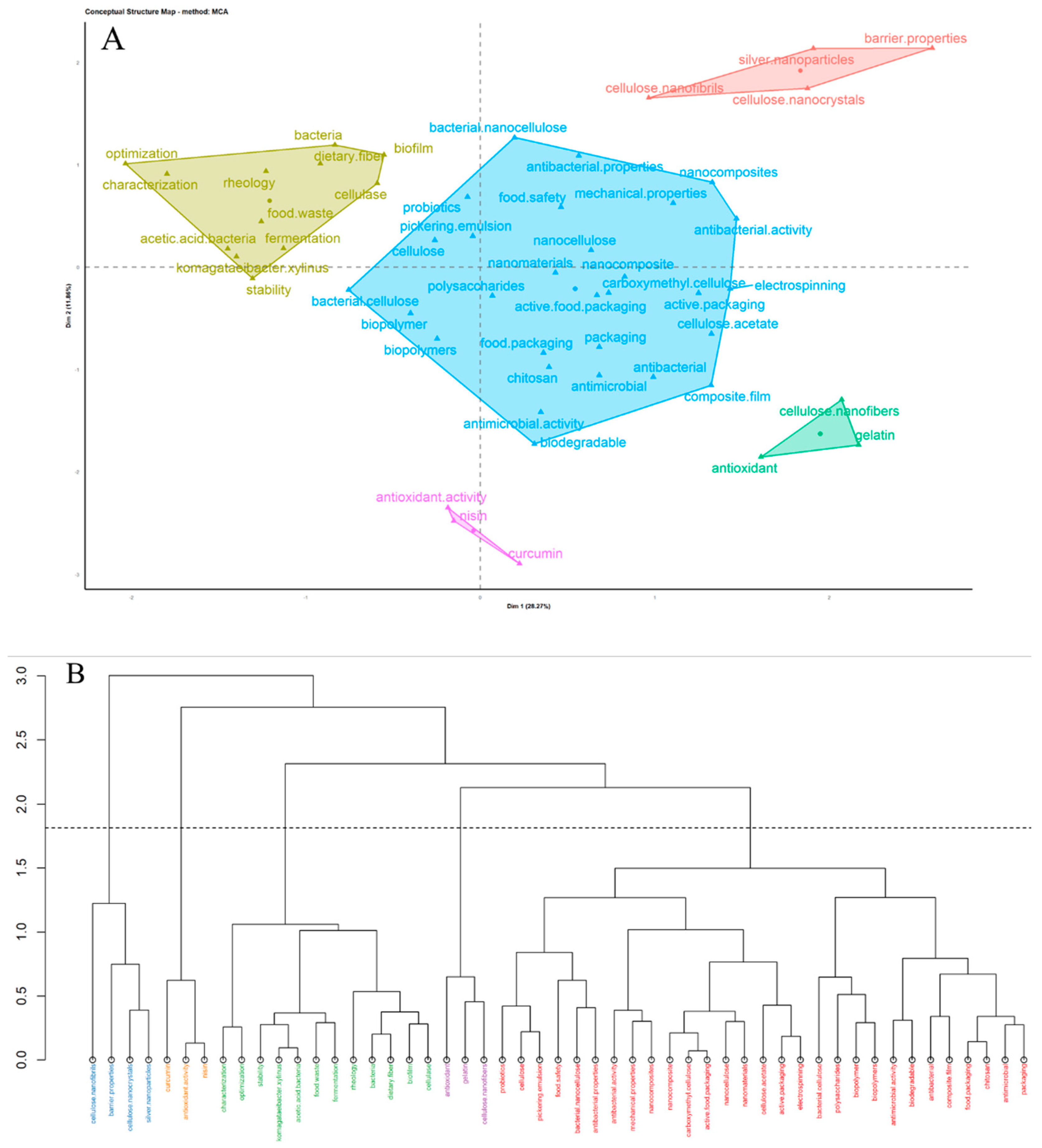

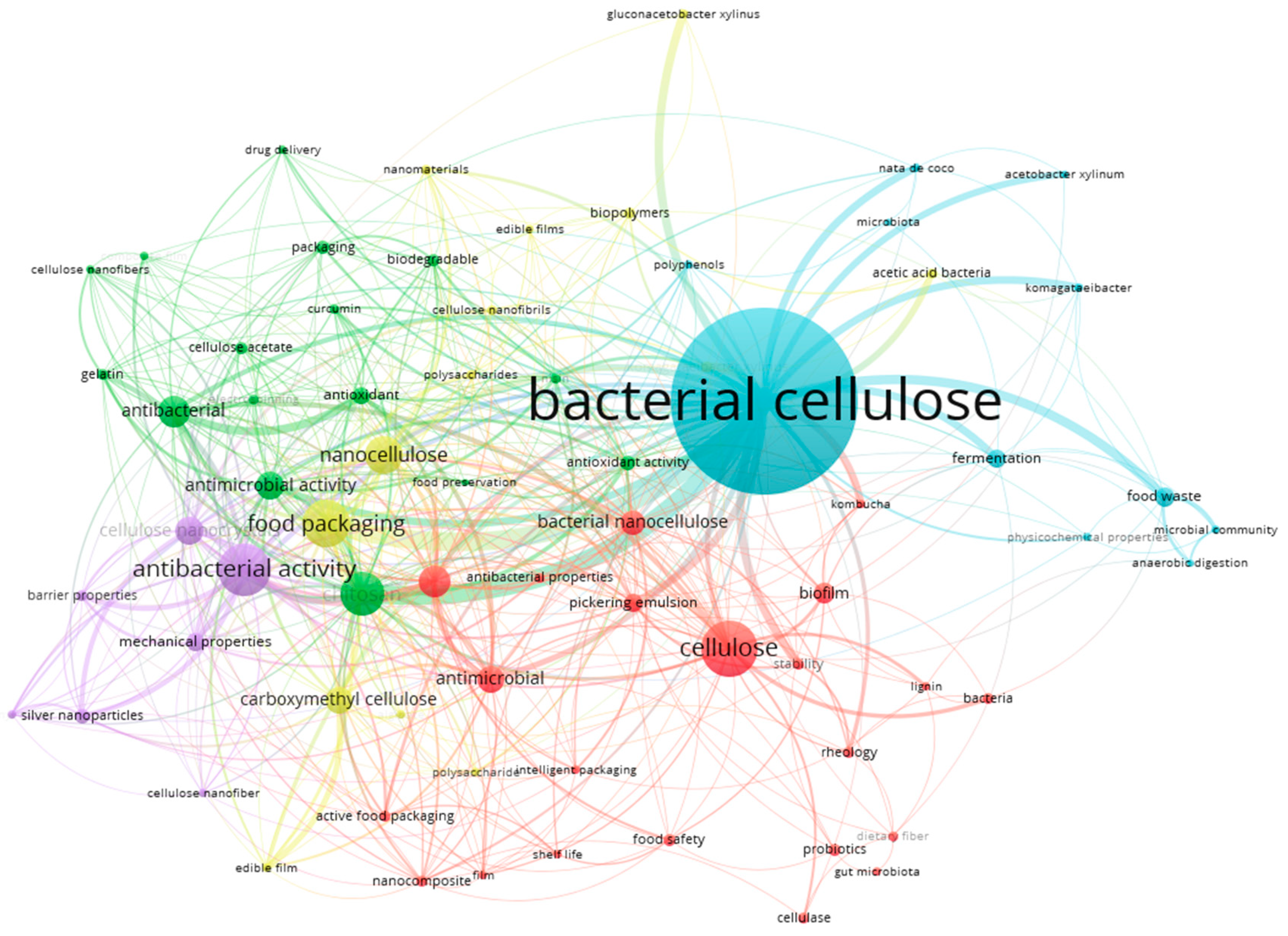

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Bibliometric Research Results

4. Deposited Patents in the Area of BC Production for Packaging

5. BC Properties and Applications

5.1. BC Films

5.2. BC Coatings

6. Enhancing the Properties of Bacterial Cellulose

7. Waste Use and Environmental Impact in CB Production

| Microorganisms | Bacterial Cellulose Production (g/L) | Productivity Rate (g/L day) | Used Waste | Fermentation Conditions (Temperature, pH, Time) | Substrate Preparation Method | Supplementation | BC Characterization | Potential Applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gluconacetobacter entanii | 2.81 | 0.10 | Pecan nutshell | pH 3.5, 30 ºC, 28 days | Sonication | - | SEM, FTIR, XRD, TGA, DSC, XPS | Biocomposites for biomedical applications | [47] |

| Gluconacetobacter sacchari | 1.28 | 0.01 | Dry olive mill | pH 4.5 | Acidic hydrolysis | HS medium | SEM, FTIR, XRD | Biomedical applications | [48] |

| Gluconacetobacter xylinus | 8.2 | 0.59 | Spruce hydrolysate | pH 5.0, 30 ºC, 12-14 days | Alkali treatment | - | - | Biomedical applications | [45] |

| Gluconacetobacter xylinus | 6.56 | 0.38 | Wine industry residue | pH 6.0, 28 ºC, 48 h | Blending | Corn steep liquor | SEM, FTIR, XRD, TGA, DMA | - | [49] |

| Komagataeibacter rhaeticus MSCL 1463 | 6.9 | 0.69 | Cheese whey | pH 4.0, 30 ºC, 10 days | Enzymatic hydrolysis | Corn steep liquor | XRD, SEM | - | [50] |

| Acetobacter xylinus NCIM 2526 | 7.01 | 1.00 | Sweet lime pulp | 28.9 ºC, pH 5.65, 7 days | Sun drying, autoclave | - | SEM, FTIR, XRD, DSC, TGA | Biomedical applications | [51] |

| Acetobacter xylinum ATCC 23767 | 2.66 | 0.44 | Sugarcane bagasse, Moso bamboo, Corncob, Wheat straw, Rice straw | 30 ºC, 6 days | Alkali-catalyzed glycerol organosolv (ALGO) pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis | - | SEM, FTIR, XRD | Biomedical and cosmetics application | [52] |

| Kombucha SCOBY | - | - | Agricultural waste | RT, 15 days | Thermic treatment | Sucrose | SEM, FTIR, XRD, TGA, DSC | Food packaging | [53] |

| Komagataeibacter xylinus | 5.68 | 0.81 | Spent sulfite liquor | pH 5.5, 30 ºC, 7 days. | Ultrafiltration | - | FT-IR, SEC, SEM | Food packing | [54] |

| Gluconobacter oxydans MG2021 and Komagataeibacter hansenii GA2016 | 25.02% (w/w) | - | Bread waste hydrolysate | 30 ºC, pH 4.5, 14 days | Acid hydrolysis | - | FT-IR, TGA, SEM, XRD | Packing applications | [55] |

| Komagataeibacter rhaeticus QK23 | 2.57 | 0.10 | Asparagus peel waste | pH 4.5, 30 ºC, 25 days. | Acid hydrolysis | - | FT-IR, AFM, XRD | Food industry | [56] |

| Stenotrophomonas sp | 8.83 | 0.63 | Banana peel waste | pH 7.0, 30 ºC, 14 days | - | - | FTIR, TGA | Biomedical, food packing, cosmetics and electrical applications | [57] |

| Komagataeibacter intermedius | 12.16 | 1.73 | Jasminum sambac | pH 6.0, 30 ºC, 7 days | Thermal extraction | Glucose | FT-IR, XRD, FIB-SEM | Biomedical and food packing | [58] |

| Komagataeibacter intermedius | 14.58 | 2.08 | Camellia sinensis | pH 6.0, 30 ºC, 7 days | Thermal extraction | Glucose | FIB-SEM, FT-IR, XRD | Biomedical and food packing | [58] |

| Kombucha SCOBY | 47.0 | 7.83 | Soybean whey (SW) | pH 4.5, 28 ºC, 6 days | Enzymatic hydrolysis | - | SEM, AFM, FT-IR, XRD, TGA | Biomedical and paper industry | [59] |

| Kombucha SCOBY | 83.0 | 13.83 | Soybean hydrolysate (SH) | pH 4.5, 28 ºC, 6 days | Enzymatic hydrolysis | - | SEM, AFM, FT-IR, XRD, TGA | Biomedical and paper industry | [59] |

| Gluconacetobacter xylinus | 6.13 | 0.77 | Orange peel hydrolysate | 30 ºC, 8 days | Enzymatic hydrolysis | - | SEM, FTIR | Biomedical applications | [60] |

| Komagataeibacter xylinus | 2.55 | 0.17 | Pineapple core | RT, pH 4.0, 15 days | Thermal treatment | Glucose | SEM, FTIR, XRD, TGA, DSC | Biomedical applications | [61] |

| Achromobacter sp. | 1.22 | 0.09 | Mango peel waste (MPW) | 28 ºc, 14 days | Acid treatment | - | ATR-FTIR, XRD, SEM, HRTEM | Biomedical | [62] |

| Kombucha SCOBY | - | - | Spent coffee grounds (SCK) | 25 ºC, 30 days | Infusion preparation | Sucrose | SEM, TGA, DSC, DPPH | Food packing | [38] |

| Kombucha SCOBY | 6.05 | 0.43 | Kitchen waste (KW) | 28 ºC, 14 days | Enzymatic hydrolysis | - | SEM, Tensile tester | Medicine, food and textiles industries | [63] |

8. Challenges and Limitations for the Use of BC as Food Packaging

8.1. Technical Challenges for Using BC in Packaging Materials

8.2. Economic Aspects for the Application of BC

8.3. Regulatory and Consumer Acceptance Challenges

9. Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Suh, S. Strategies to Reduce the Global Carbon Footprint of Plastics. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwabl, P.; Köppel, S.; Königshofer, P.; Bucsics, T.; Trauner, M.; Reiberger, T.; Liebmann, B. Detection of Various Microplastics in Human Stool. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and Human Health: A Micro Issue? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iguchi, M.; Yamanaka, S.; Budhiono, A. Bacterial Cellulose—a Masterpiece of Nature’s Arts. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, D.; Schumann, D.; Udhardt, U.; Marsch, S. Bacterial Synthesized Cellulose — Artificial Blood Vessels for Microsurgery. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2001, 26, 1561–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozala, A.F.; de Lencastre-Novaes, L.C.; Lopes, A.M.; de Carvalho Santos-Ebinuma, V.; Mazzola, P.G.; Pessoa-Jr, A.; Grotto, D.; Gerenutti, M.; Chaud, M.V. Bacterial Nanocellulose Production and Application: A 10-Year Overview. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Wang, K.; Chen, P.; Cai, D.; Shao, Y.; Xia, R.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Ren, F.; Cheng, X.; et al. Fully Biodegradable Packaging Films for Fresh Food Storage Based on Oil-Infused Bacterial Cellulose. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Vázquez, M. Bacterial Cellulose as a Biodegradable Food Packaging Material: A Review. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiazhou, L.; Yuping, X.; Ronglin, H.; Xin, Z.; Dongqing, Z. Bacterial Cellulose Edible Packaging Product and Production Method Thereof 2011, CN102211689A.

- Jian-Jiang, Zhong; Wei, P.; Lifang, F.; Yaqin, Z.; Guojian, B. Jian-Jiang Zhong; Wei, P.; Lifang, F.; Yaqin, Z.; Guojian, B. Preparation Method of Food Packaging Film Based on Bacterial Nano-Cellulose 2020, CN11147119.

- Hess, A.J.; Smalyukh, I.I.; Liu, Q.; Cruz, J.A.D. La; Abraham, E.; Cherpak, V.; Senyuk, B. Bacterial Cellulose Gels, Process for Producing and Methods for Use 2024, US2024/0158601A1.

- Missoum, K.; Zeboudj, L.; Niederreiter, G. Thermoformed Cellulose-Based Food Packaging 2022, WO2022/048876A1.

- Tajima, K.; Kose, R.; Sakurai, H. Bacterial Cellulose and Bacterium Producing It. 2018, US9879295B2.

- Chen, M.; Wu, V.S.; Falk, D.; Cheatham, C.; Cullen, J.; Hoehn, R. Patient Navigation in Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 504–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, S.K.; Broyles, N.S.; Winuk, A.J.; Hayes, J.C.; Charlotte, E.; Boswell; Arent, L.M. FLEXIBLE BARRIER PACKAGING DERIVED FROM RENEWABLE RESOURCES 2014, US8871319B2.

- Ul-Islam, M.; Khan, S.; Ullah, M.W.; Park, J.K. Comparative Study of Plant and Bacterial Cellulose Pellicles Regenerated from Dissolved States. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marestoni, L.D.; Barud, H. da S.; Gomes, R.J.; Catarino, R.P.F.; Hata, N.N.Y.; Ressutte, J.B.; Spinosa, W.A. Commercial and Potential Applications of Bacterial Cellulose in Brazil: Ten Years Review. Polimeros 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.C.; Barud, H.; Farinas, C.S.; Vasconcellos, V.M.; Claro, A.M. Bacterial Cellulose as a Raw Material for Food and Food Packaging Applications. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lan, W.; Xie, J. Characterization of Active Films Based on Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Integrated with Ginger Essential Oil-Loaded Bacterial Cellulose and Application in Sea Bass (Lateolabrax Japonicas) Packaging. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.; Flórez, M.; Cazón, P. A Strategy to Prolong Cheese Shelf-Life: Laminated Films of Bacterial Cellulose and Chitosan Loaded with Grape Bagasse Antioxidant Extract for Effective Lipid Oxidation Delay. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T.; Cai, R.; et al. Enzymatically Green-Produced Bacterial Cellulose Nanoparticle-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion for Enhancing Anthocyanin Colorimetric Performance of Versatile Films. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesgari, M.; Matin, M.M.; Goharshadi, E.K.; Mashreghi, M. Biogenesis of Bacterial Cellulose/Xanthan/CeO2NPs Composite Films for Active Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 133091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Q. Preservation of Chilled Beef Using Active Films Based on Bacterial Cellulose and Polyvinyl Alcohol with the Incorporation of Perilla Essential Oil Pickering Emulsion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Li, N.; Peng, H.; Yang, X.; Lin, D. The Development of Highly PH-Sensitive Bacterial Cellulose Nanofibers/Gelatin-Based Intelligent Films Loaded with Anthocyanin/Curcumin for the Fresh-Keeping and Freshness Detection of Fresh Pork. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retegi, A.; Gabilondo, N.; Peña, C.; Zuluaga, R.; Castro, C.; Gañan, P.; de la Caba, K.; Mondragon, I. Bacterial Cellulose Films with Controlled Microstructure-Mechanical Property Relationships. Cellulose 2010, 17, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, R.M.M.; Hamed, D.A.; Gomaa, O.M. Red Cabbage Extract Immobilized in Bacterial Cellulose Film as an Eco-Friendly Sensor to Monitor Microbial Contamination and Gamma Irradiation of Stored Cucumbers. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhu, T.; Gou, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Lai, Y. Ecological Packaging: Creating Sustainable Solutions with All-Natural Biodegradable Cellulose Materials. Giant 2024, 18, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, A.P.; Thangarasu, S.; Manoharan, R.K.; Oh, T.H. Ex-Situ Fabrication of Engineered Green Network of Multifaceted Bacterial Cellulose Film with Enhanced Antimicrobial Properties for Post-Harvest Preservation of Table Grapes. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 43, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, N. Native Bacterial Cellulose Films Based on Kombucha Pellicle as a Potential Active Food Packaging. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carullo, D.; Rovera, C.; Bellesia, T.; Büyüktaş, D.; Ghaani, M.; Santo, N.; Romano, D.; Farris, S. Acid-Derived Bacterial Cellulose Nanocrystals as Organic Filler for the Generation of High-Oxygen Barrier Bio-Nanocomposite Coatings. Sustain. Food Technol. 2023, 1, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yue, T.; Cai, R.; Muratkhan, M.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z. A Green Versatile Packaging Based on Alginate and Anthocyanin via Incorporating Bacterial Cellulose Nanocrystal-Stabilized Camellia Oil Pickering Emulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 126134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, X.; Fan, X.; Hu, Y.; Niu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G.; Ullah, N.; et al. Antibacterial Aerogels with Nano-silver Reduced in Situ by Carboxymethyl Cellulose for Fresh Meat Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 213, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, W.; Gu, R.; Shi, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L.; Xiao, H.; Li, C. Indicative Bacterial Cellulose Films Incorporated with Curcumin-Embedded Pickering Emulsions: Preparation, Antibacterial Performance, and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Peng, H.; Zhao, A.; Zhang, R.; Li, T.; Yang, X.; Lin, D. Synthesis of Bacterial Cellulose Nanofibers/Ag Nanoparticles: Structure, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattak, S.; Qin, X.T.; Huang, L.H.; Xie, Y.Y.; Jia, S.R.; Zhong, C. Preparation and Characterization of Antibacterial Bacterial Cellulose/Chitosan Hydrogels Impregnated with Silver Sulfadiazine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agüero, A.; Lascano, D.; Ivorra-Martinez, J.; Gómez-Caturla, J.; Arrieta, M.P.; Balart, R. Use of Bacterial Cellulose Obtained from Kombucha Fermentation in Spent Coffee Grounds for Active Composites Based on PLA and Maleinized Linseed Oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 202, 116971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, K.Q.; Hoang, C.H.; Van Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, D.H.; Mai, H.H. High Microbiostatic and Microbicidal Efficiencies of Bacterial Cellulose-ZnO Nanocomposites for in Vivo Microbial Inhibition and Filtering. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2023, 301, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frota, M.M.; Miranda, K.W.E.; Marques, V.S.; Miguel, T.B.A.R.; Mattos, A.L.A.; Miguel, E. de C.; Santos, N.L. dos; Souza, T.M. de; Salomão, F.C.C.S.; Farias, P.M. de; et al. Modified Bacterial Nanofibril for Application in Superhydrophobic Coating of Food Packaging. Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, T.; Ul-Islam, M.; Fatima, A.; Ullah, M.W.; Manan, S. Cost-Effective Synthesis of Bacterial Cellulose and Its Applications in the Food and Environmental Sectors. Gels 2022, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsouko, E.; Maina, S.; Ladakis, D.; Kookos, I.K.; Koutinas, A. Integrated Biorefinery Development for the Extraction of Value-Added Components and Bacterial Cellulose Production from Orange Peel Waste Streams. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-P.; Huang, S.-H.; Ting, Y.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Cheng, K.-C. Evaluation of Detoxified Sugarcane Bagasse Hydrolysate by Atmospheric Cold Plasma for Bacterial Cellulose Production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 204, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dórame-Miranda, R.F.; Gámez-Meza, N.; Medina-Juárez, L.Á.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M.; Ovando-Martínez, M.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J. Bacterial Cellulose Production by Gluconacetobacter Entanii Using Pecan Nutshell as Carbon Source and Its Chemical Functionalization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Cavka, A.; Jönsson, L.J.; Hong, F. Comparison of Methods for Detoxification of Spruce Hydrolysate for Bacterial Cellulose Production. Microb. Cell Fact. 2013, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrutti, P.; Roldán, P.; García, R.M.; Galvagno, M.A.; Vázquez, A.; Foresti, M.L. Production of Bacterial Nanocellulose from Wine Industry Residues: <scp>I</Scp> Mportance of Fermentation Time on Pellicle Characteristics. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dórame-Miranda, R.F.; Gámez-Meza, N.; Medina-Juárez, L.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M.; Ovando-Martínez, M.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J. Bacterial Cellulose Production by Gluconacetobacter Entanii Using Pecan Nutshell as Carbon Source and Its Chemical Functionalization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.P.; Silva, N.H.C.S.; Trovatti, E.; Serafim, L.S.; Duarte, M.F.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Neto, C.P.; Freire, C.S.R. Production of Bacterial Cellulose by Gluconacetobacter Sacchari Using Dry Olive Mill Residue. Biomass and Bioenergy 2013, 55, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrutti, P.; Roldán, P.; García, R.M.; Galvagno, M.A.; Vázquez, A.; Foresti, M.L. Production of Bacterial Nanocellulose from Wine Industry Residues: Importance of Fermentation Time on Pellicle Characteristics. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesovs, S.; Neiberts, K.; Semjonovs, P.; Beluns, S.; Platnieks, O.; Gaidukovs, S. Evaluation of Hydrolyzed Cheese Whey Medium for Enhanced Bacterial Cellulose Production by Komagataeibacter Rhaeticus MSCL 1463. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, M.K. Novel Low-Cost Green Method for Production Bacterial Cellulose. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 6721–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Huang, C.; Feng, S.; Yang, H.; Tian, D. Valorization of Straw Biomass into Lignin Bio-Ink, Bacterial Cellulose and Activated Nanocarbon through the Trade-off Alkali-Catalyzed Glycerol Organosolv Biorefinery. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreshkov, M.; Takatsuna, Y.; Bismarck, A.; Fritz, I.; Reimhult, E.; Zirbs, R. Sustainable Food Packaging Using Modified Kombucha-Derived Bacterial Cellulose Nanofillers in Biodegradable Polymers. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distler, T.; Huemer, K.; Leitner, V.; Bischof, R.H.; Groiss, H.; Guebitz, G.M. Production of Bacterial Cellulose by Komagataeibacter Intermedius from Spent Sulfite Liquor. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2023, 24, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, M. Valorisation of Bread Wastes via the Bacterial Cellulose Production. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Cerna, C.; Rodríguez-Soto, J.C.; Barraza-Jáuregui, G.; Huanes-Carranza, J.; Cruz-Monzón, J.A.; Ugarte-López, W.; Hurtado-Butrón, F.; Samanamud-Moreno, F.; Haro-Carranza, D.; Valdivieso-Moreno, S.; et al. Bioconversion of Agroindustrial Asparagus Waste into Bacterial Cellulose by Komagataeibacter Rhaeticus. Sustainability 2024, 16, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Sakhrie, M.; Kumar, M.; Vivekanand, V.; Pareek, N. Enhanced Production of Bacterial Cellulose Employing Banana Peel as a Cost-Effective Nutrient Resource. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 2745–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcioglu, N.H. Eco-Friendly Production of Bacterial Cellulose with Komagataeibacter Intermedius Strain by Using Jasminum Sambac and Camellia Sinensis Plants. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Isolation and Characterization of Bacterial Cellulose Produced from Soybean Whey and Soybean Hydrolyzate. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Shieh, C.-J.; Wang, H.-M.D.; Tseng, C.-Y. Hydrolysis of Orange Peel with Cellulase and Pectinase to Produce Bacterial Cellulose Using Gluconacetobacter Xylinus. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardawati, E.; Rahmah, D.M.; Rachmadona, N.; Saharina, E.; Pertiwi, T.Y.R.; Zahrad, S.A.; Ramdhani, W.; Srikandace, Y.; Ratnaningrum, D.; Endah, E.S.; et al. Pineapple Core from the Canning Industrial Waste for Bacterial Cellulose Production by Komagataeibacter Xylinus. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanin, M.S.; Abdelraof, M.; Hashem, A.H.; El Saied, H. Sustainable Bacterial Cellulose Production by Achromobacter Using Mango Peel Waste. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weihua, Q.; Hong, R.; Qianhui, W. Production of Bacterial Cellulose from Enzymatic Hydrolysate of Kitchen Waste by Fermentation with Kombucha. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 13, 14485–14496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aili Hamzah, A.F.; Hamzah, M.H.; Che Man, H.; Jamali, N.S.; Siajam, S.I.; Ismail, M.H. Recent Updates on the Conversion of Pineapple Waste (Ananas Comosus) to Value-Added Products, Future Perspectives and Challenges. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachwał, K.; Waśko, A.; Gustaw, K.; Polak-Berecka, M. Utilization of Brewery Wastes in Food Industry. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, L.; Rodrigues, R.; Fischer, D.; Tovar-Castro, J.D.; Payne, A.; Navone, L.; Hu, Y.; Yan, H.; Pinmanee, P.; Poon, E.; et al. Bacterial Cellulose Cookbook: A Systematic Review on Sustainable and Cost-Effective Substrates. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.; Nag, M.; Dutta, B.; Dey, A.; Sarkar, T.; Pati, S.; Edinur, H.A.; Abdul Kari, Z.; Mohd Noor, N.H.; Ray, R.R. Bacterial Cellulose: Production, Characterization, and Application as Antimicrobial Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, W.; Zeng, W.; Mustapha, A.; Lin, M. Soy Protein-Based Films Incorporated with Cellulose Nanocrystals and Pine Needle Extract for Active Packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciecholewska-Juśko, D.; Broda, M.; Żywicka, A.; Styburski, D.; Sobolewski, P.; Gorący, K.; Migdał, P.; Junka, A.; Fijałkowski, K. Potato Juice, a Starch Industry Waste, as a Cost-Effective Medium for the Biosynthesis of Bacterial Cellulose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsia, A.; Tsouko, E.; Pateraki, C.; Efthymiou, M.-N.; Papagiannopoulos, A.; Selianitis, D.; Pispas, S.; Bethanis, K.; Koutinas, A. Valorization of Wheat Milling By-Products into Bacterial Nanocellulose via Ex-Situ Modification Following Circular Economy Principles. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 29, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Challenges and New Opportunities on Barrier Performance of Biodegradable Polymers for Sustainable Packaging. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 117, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, H.; Sogame, Y.; Purevdorj, U.-E.; Ogata, M.; Tajima, K. Bacterial Cellulose Nanofibers Modified with Quaternary Ammonium Salts for Antimicrobial Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 4854–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, L.F.A.; Mouro, C.; Riool, M.; Gouveia, I.C. Antimicrobial Food Packaging Based on Prodigiosin-Incorporated Double-Layered Bacterial Cellulose and Chitosan Composites. Polymers (Basel). 2022, 14, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.A.G.S.; Dourado, F.; Gama, M.; Poças, F. Nanocellulose Bio-Based Composites for Food Packaging. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, A.K.; Majlan, E.H.; Loh, K.S.; Wong, W.Y.; Alva, S.; Khaerudini, D.S.; Yunus, R.M. Effect of Acid Treatments on Thermal Properties of Bacterial Cellulose Produced from Cassava Liquid Waste. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 57, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, M.I.; Makarov, I.S.; Golova, L.K.; Gromovykh, P.S.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Rheological Properties of Aqueous Dispersions of Bacterial Cellulose. Processes 2020, 8, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillat, A.; Martínez, J.; Valls, C.; Cusola, O.; Roncero, M.B.; Vidal, T.; Valenzuela, S. V.; Diaz, P.; Pastor, F.I.J. Bacterial Cellulose for Increasing Barrier Properties of Paper Products. Cellulose 2018, 25, 6093–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, E.A.; Budaeva, V. V.; Ovchinnikova, E. V.; Gladysheva, E.K.; Kashcheyeva, E.I.; Pavlov, I.N.; Sakovich, G. V. A Technology for Pilot Production of Bacterial Cellulose from Oat Hulls. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C. Industrial-Scale Production and Applications of Bacterial Cellulose. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsouko, E.; Pilafidis, S.; Kourmentza, K.; Gomes, H.I.; Sarris, G.; Koralli, P.; Papagiannopoulos, A.; Pispas, S.; Sarris, D. A Sustainable Bioprocess to Produce Bacterial Cellulose (BC) Using Waste Streams from Wine Distilleries and the Biodiesel Industry: Evaluation of BC for Adsorption of Phenolic Compounds, Dyes and Metals. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, P.K.; Pattnaik, R.; Kumar, S.; Ojha, S.K.; Srichandan, H.; Parhi, P.K.; Jyothi, R.K.; Sarangi, P.K. Biochemistry, Synthesis, and Applications of Bacterial Cellulose: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swingler, S.; Gupta, A.; Gibson, H.; Kowalczuk, M.; Heaselgrave, W.; Radecka, I. Recent Advances and Applications of Bacterial Cellulose in Biomedicine. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanisamy, S.; Selvaraju, G.D.; Selvakesavan, R.K.; Venkatachalam, S.; Bharathi, D.; Lee, J. Unlocking Sustainable Solutions: Nanocellulose Innovations for Enhancing the Shelf Life of Fruits and Vegetables – A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharyya, P.P.; Sarma, M.; Kashyap, A. Recent Advances in Synthesis and Bioengineering of Bacterial Nanocellulose Composite Films for Green, Active and Intelligent Food Packaging. Cellulose 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.; Gottschalk, L.; Freitas-Silva, O. Overview of Nanocellulose in Food Packaging. Recent Pat. Food. Nutr. Agric. 2019, 11, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | Bacterial Cellulose | Plant Cellulose |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Produced by bacteria, especially Gluconacetobacter xylinus | Derived from plants such as cotton, wood, and bamboo |

| Purity | High purity, free of lignin and hemicellulose | Contains lignin, hemicellulose, and other components |

| Structure | Three-dimensional network of nanofibers | Fibers arranged in hierarchical structures |

| Crystallinity | High crystallinity | Varies depending on the source and treatment |

| Mechanical Strength | High tensile strength (up to 200 MPa) | Variable strength (40-200 MPa) depending on the source and treatment |

| Flexibility | High flexibility | Less flexible compared to bacterial cellulose |

| Barrier Properties | Excellent barrier against gases and moisture | Variable barrier properties, generally inferior to bacterial cellulose |

| Biocompatibility | Naturally non-toxic, high biocompatibility | High biocompatibility but may contain impurities that need to be removed |

| Source | Produced by bacteria, especially Gluconacetobacter xylinus | Derived from plants such as cotton, wood, and bamboo |

| Purity | High purity, free of lignin and hemicellulose | Contains lignin, hemicellulose, and other components |

| Structure | Three-dimensional network of nanofibers | Fibers arranged in hierarchical structures |

| Keyword | Occurrence | Total Link Strength | Keyword | Occurrence | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial cellulose | 349 | 314 | Antimicrobial | 41 | 64 |

| Food Packing | 76 | 117 | Antibacterial | 49 | 63 |

| Chitosan | 69 | 109 | Cellulose nanocrystals | 42 | 62 |

| Antibacterial activity | 84 | 104 | Antimicrobial activity | 43 | 61 |

| Cellulose | 92 | 82 | Carboxymethyl cellulose | 41 | 53 |

| Active packing | 48 | 76 | Antioxidant | 24 | 46 |

| Nanocellulose | 58 | 72 | Mechanical properties | 27 | 44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).