Submitted:

11 August 2024

Posted:

14 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Morocco’s Energy Landscape

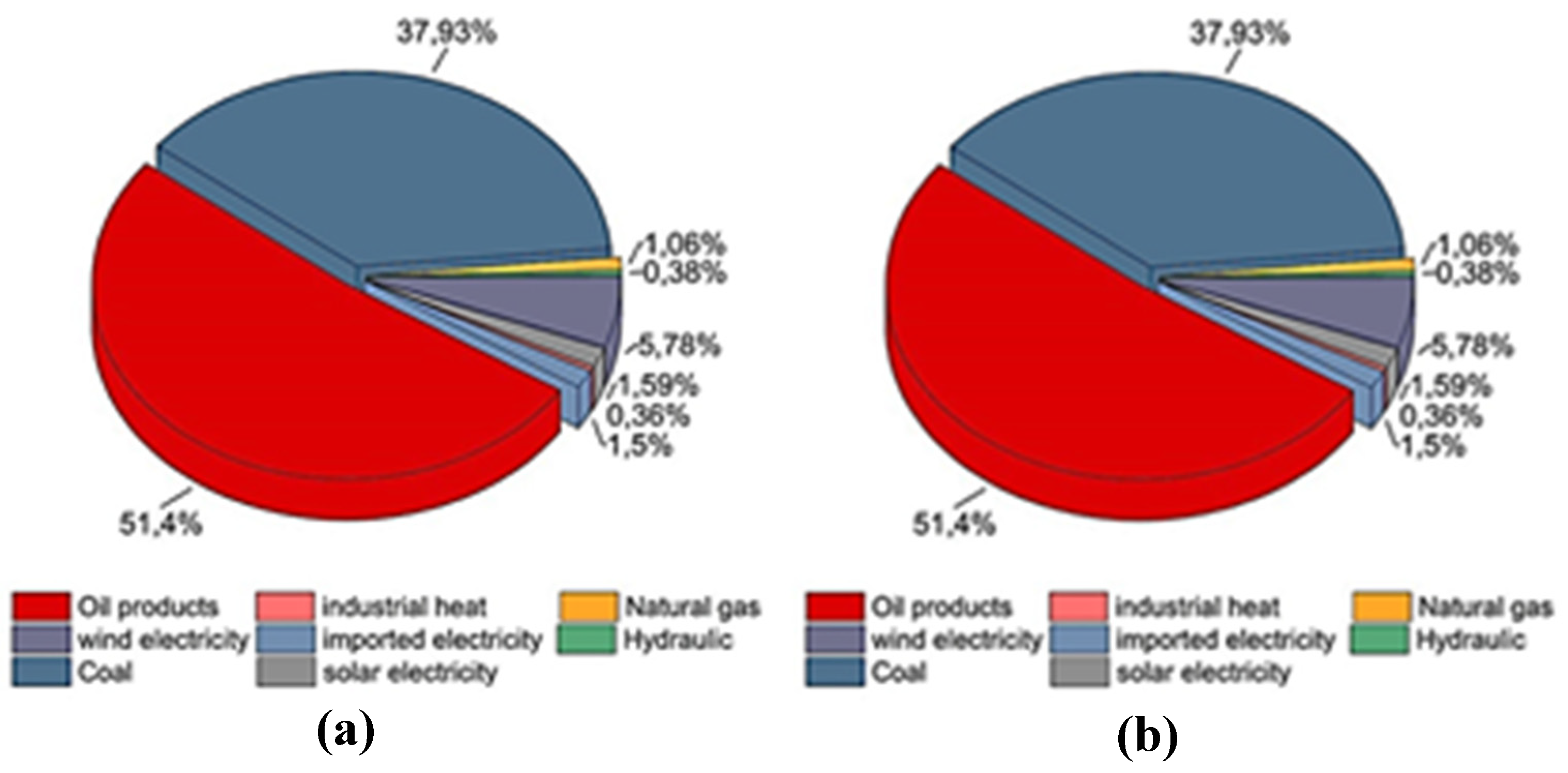

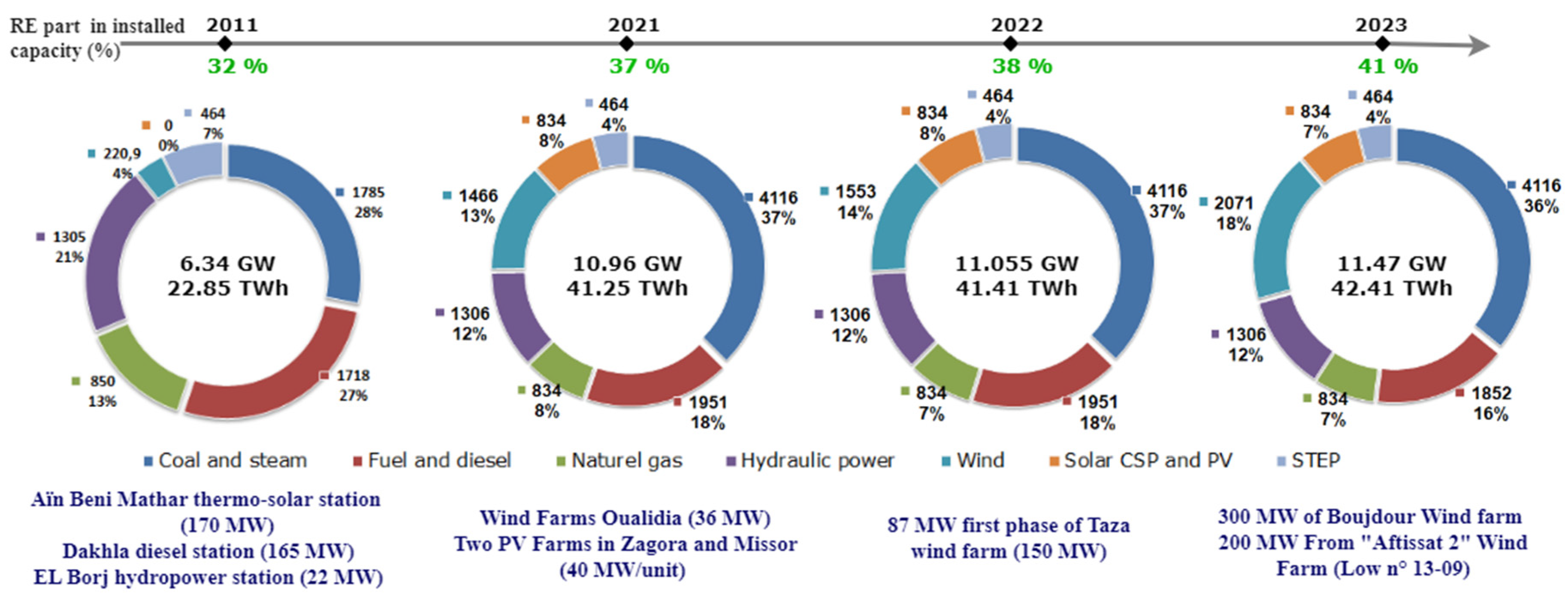

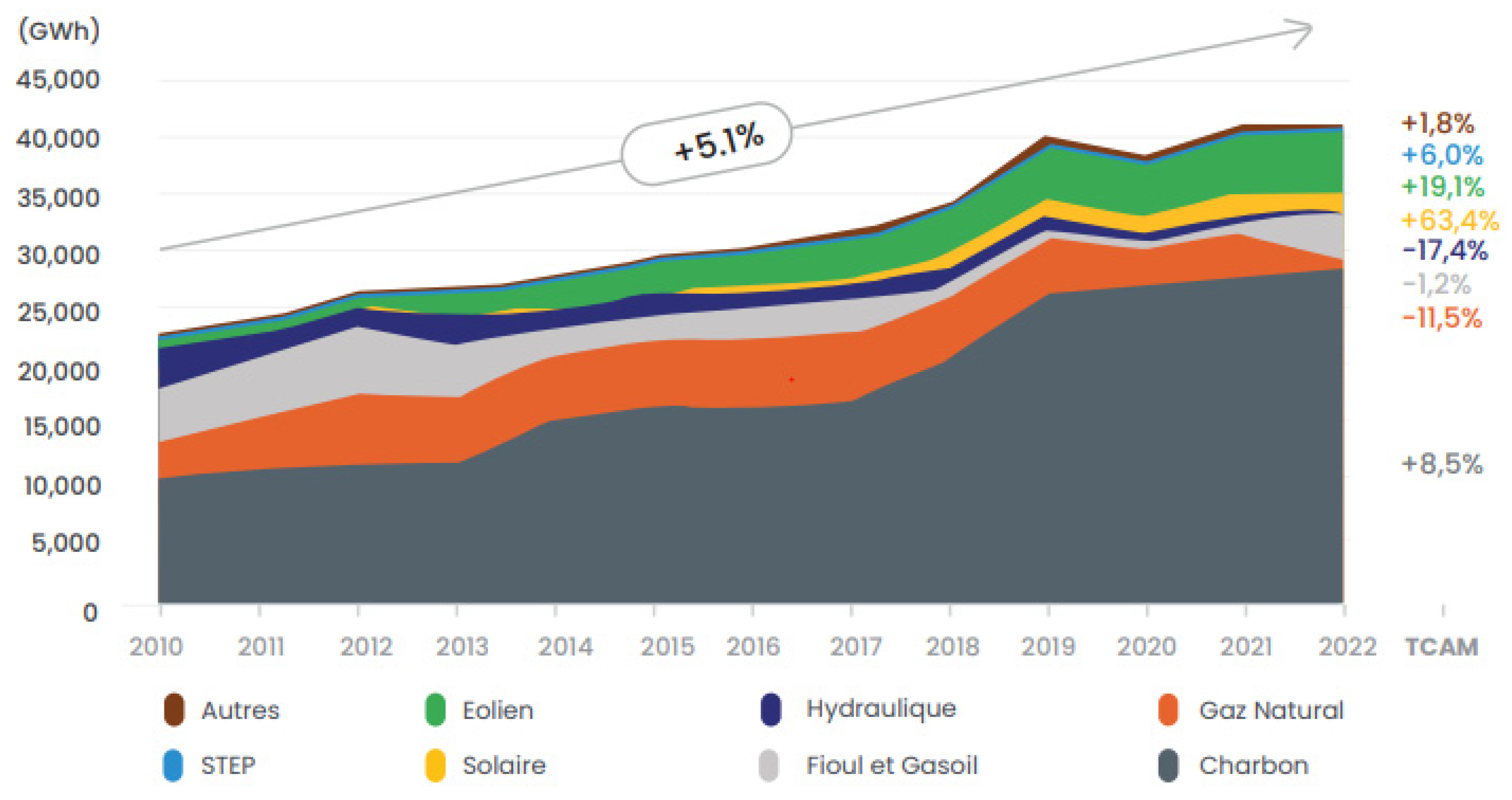

2.1. Moroccan Energy Sector in Numbers

2.2. Moroccan Energy Strategy

2.3. Moroccan Green Hydrogen Strategy

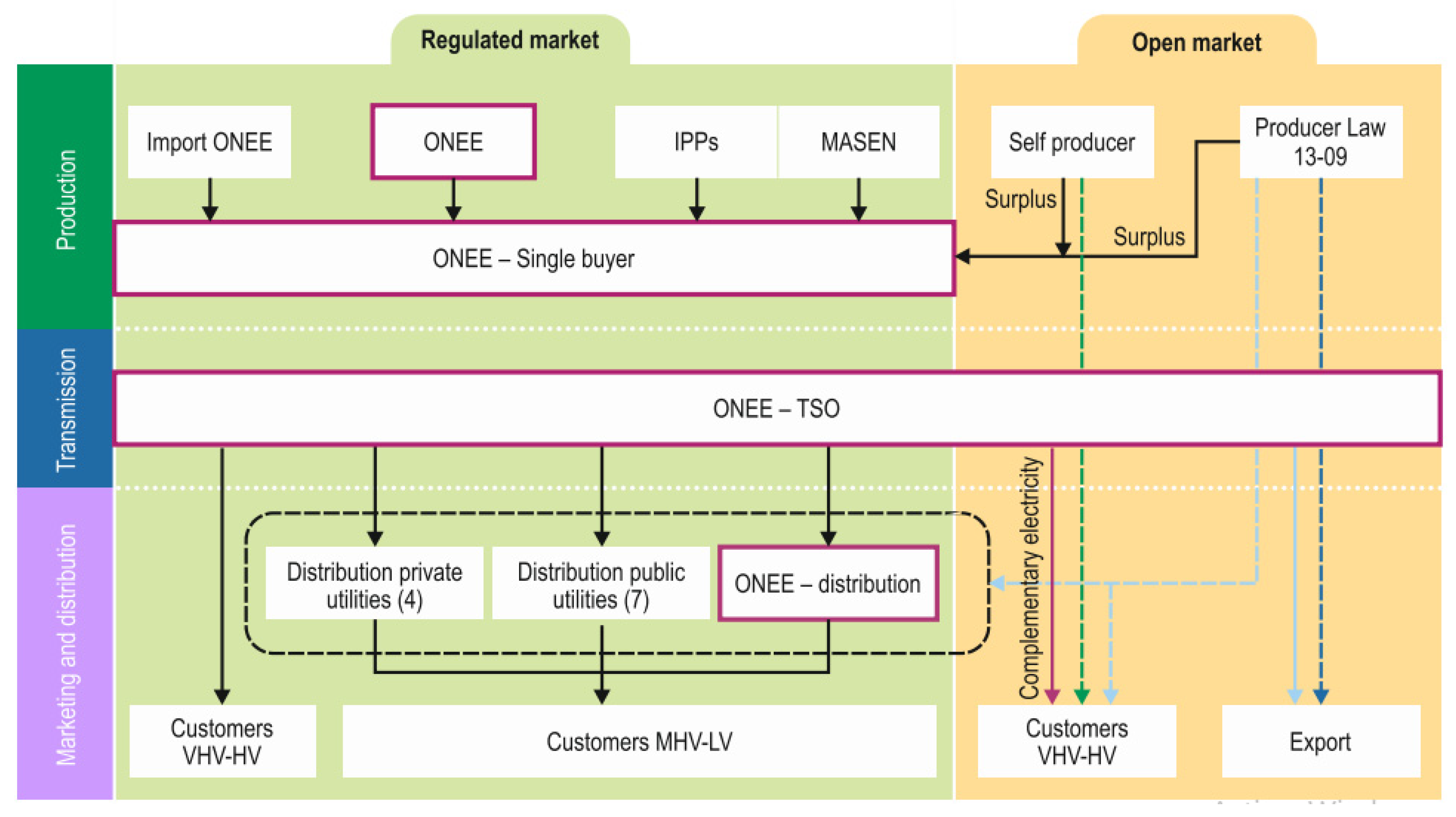

2.4. Electricity Sector Organization

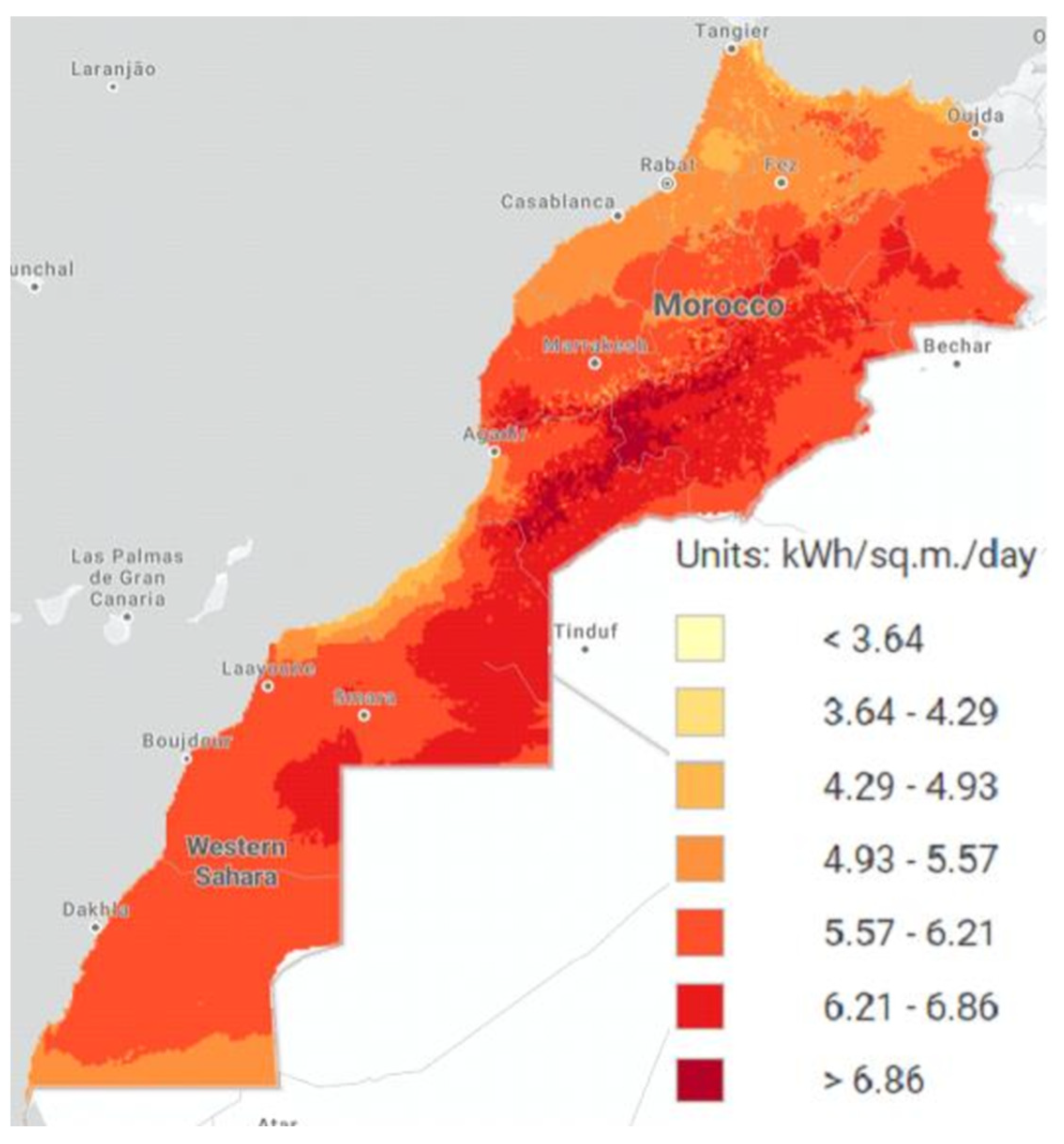

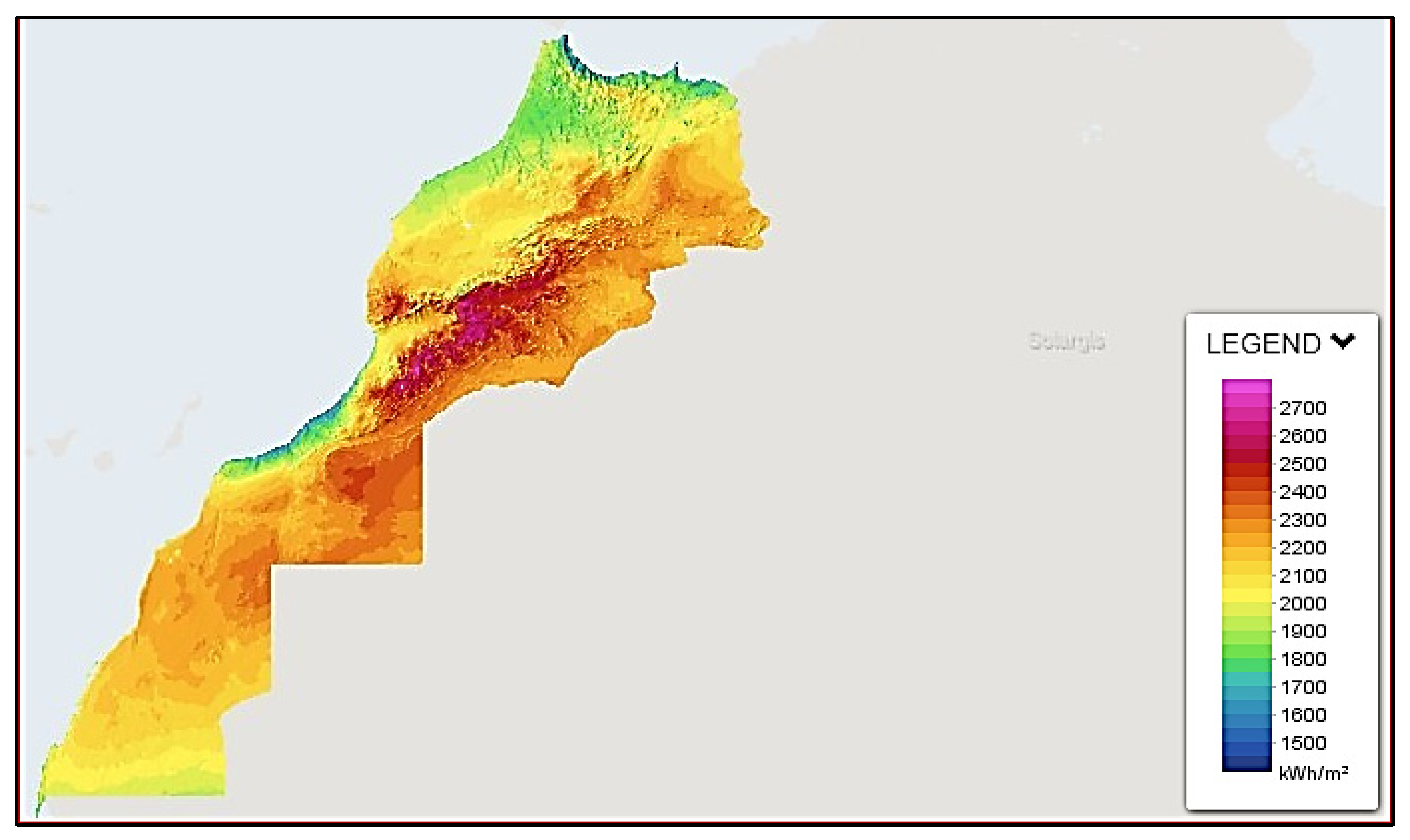

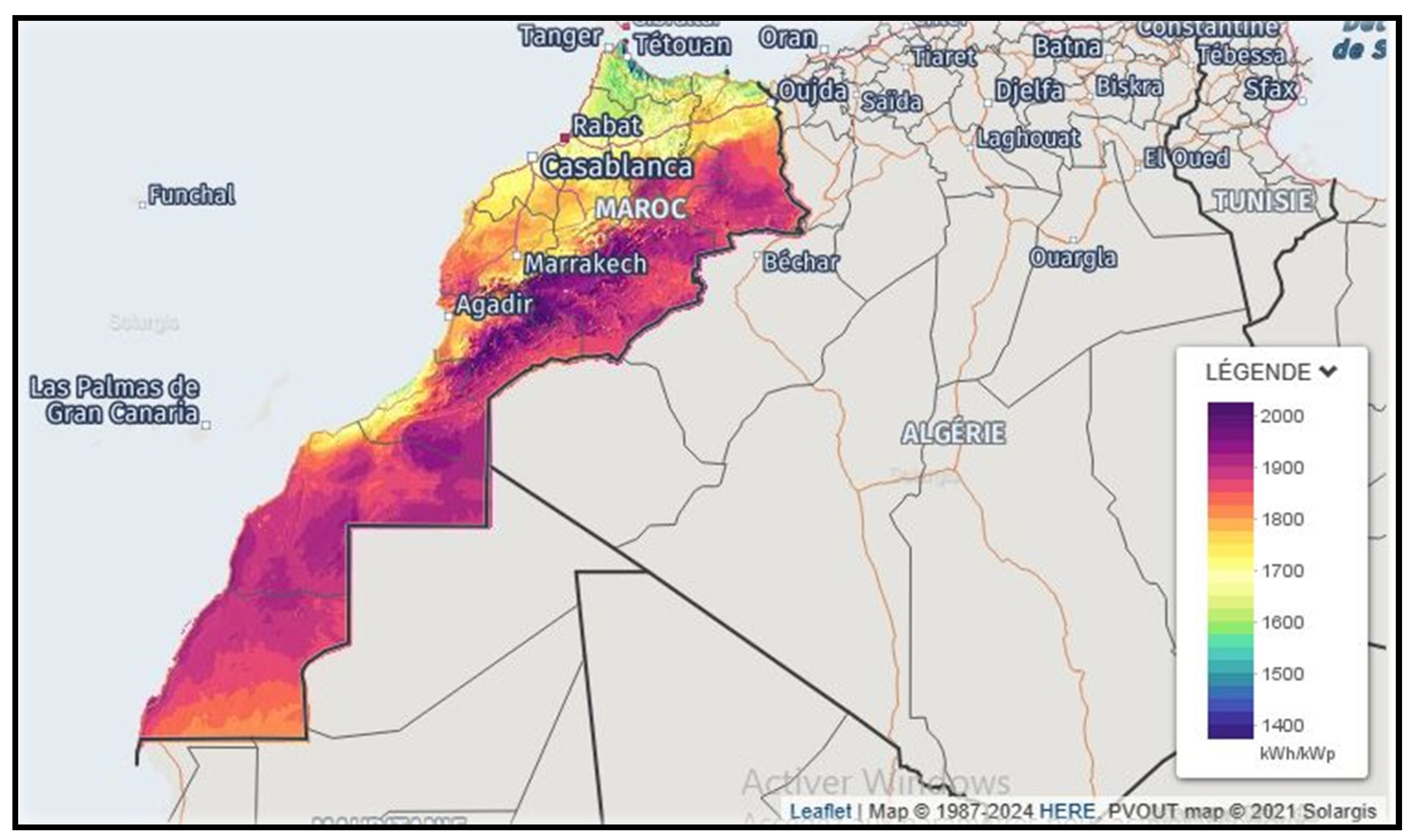

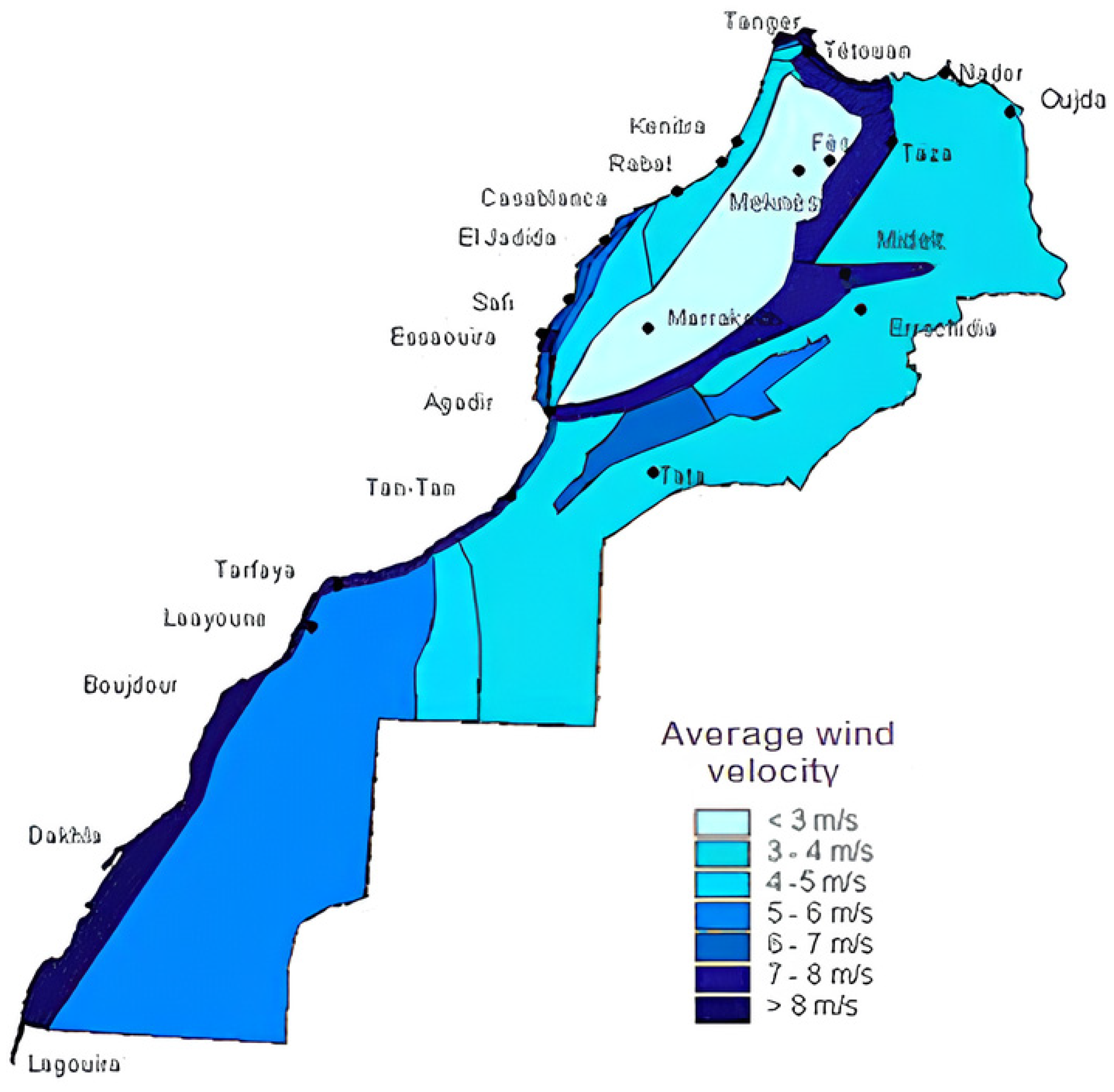

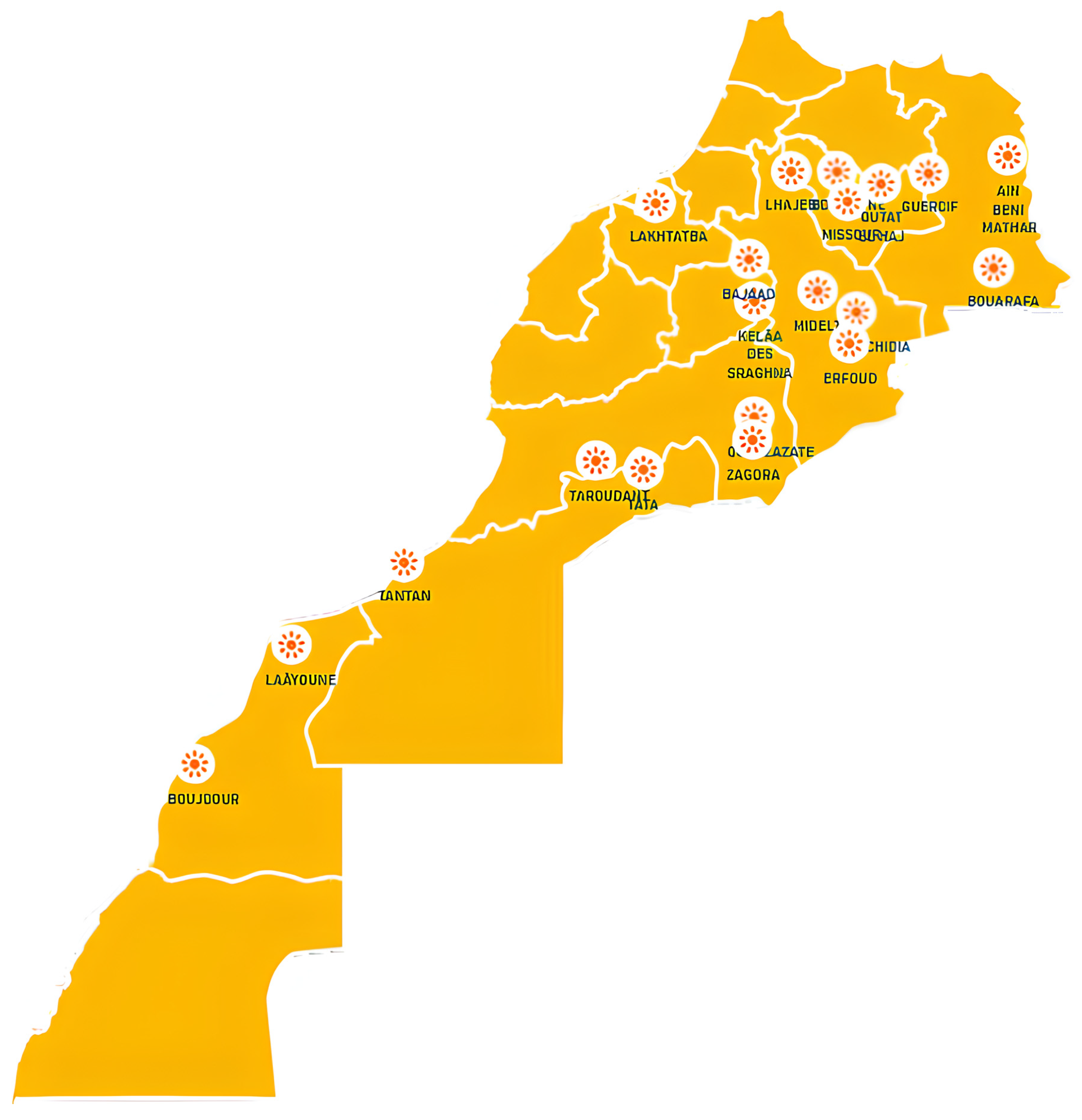

3. Solar Resources Potential in Morocco

4. Current State of Solar Energy in Morocco

4.1. Policies and Regulations

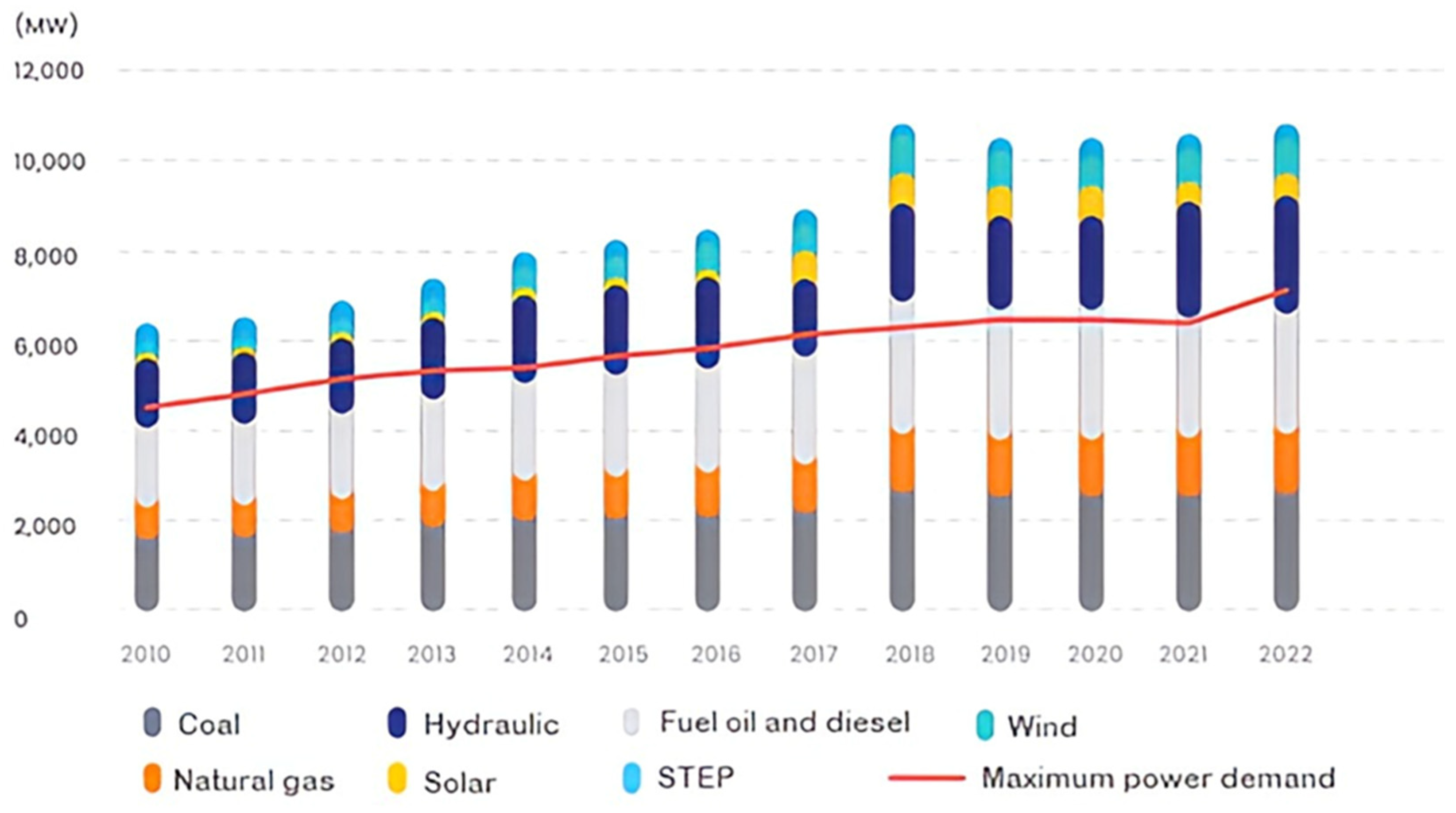

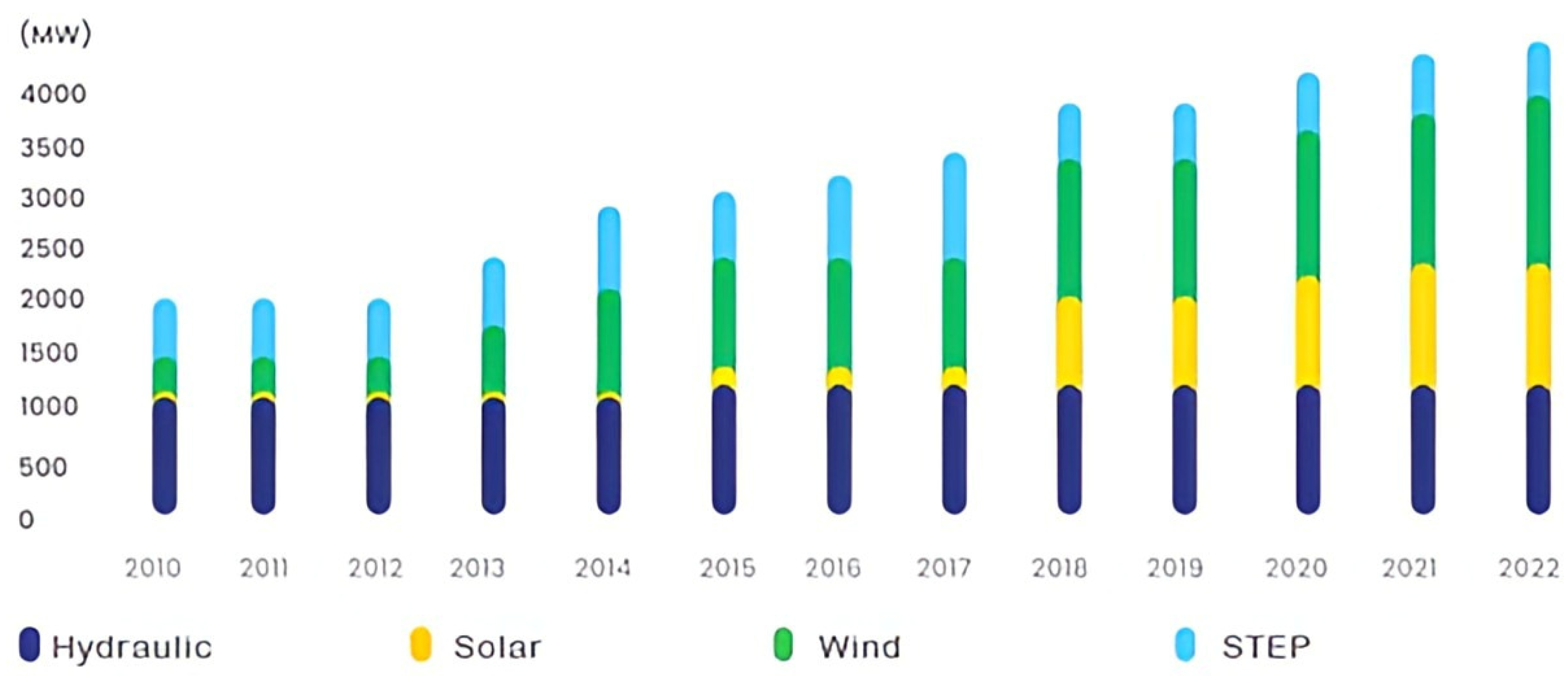

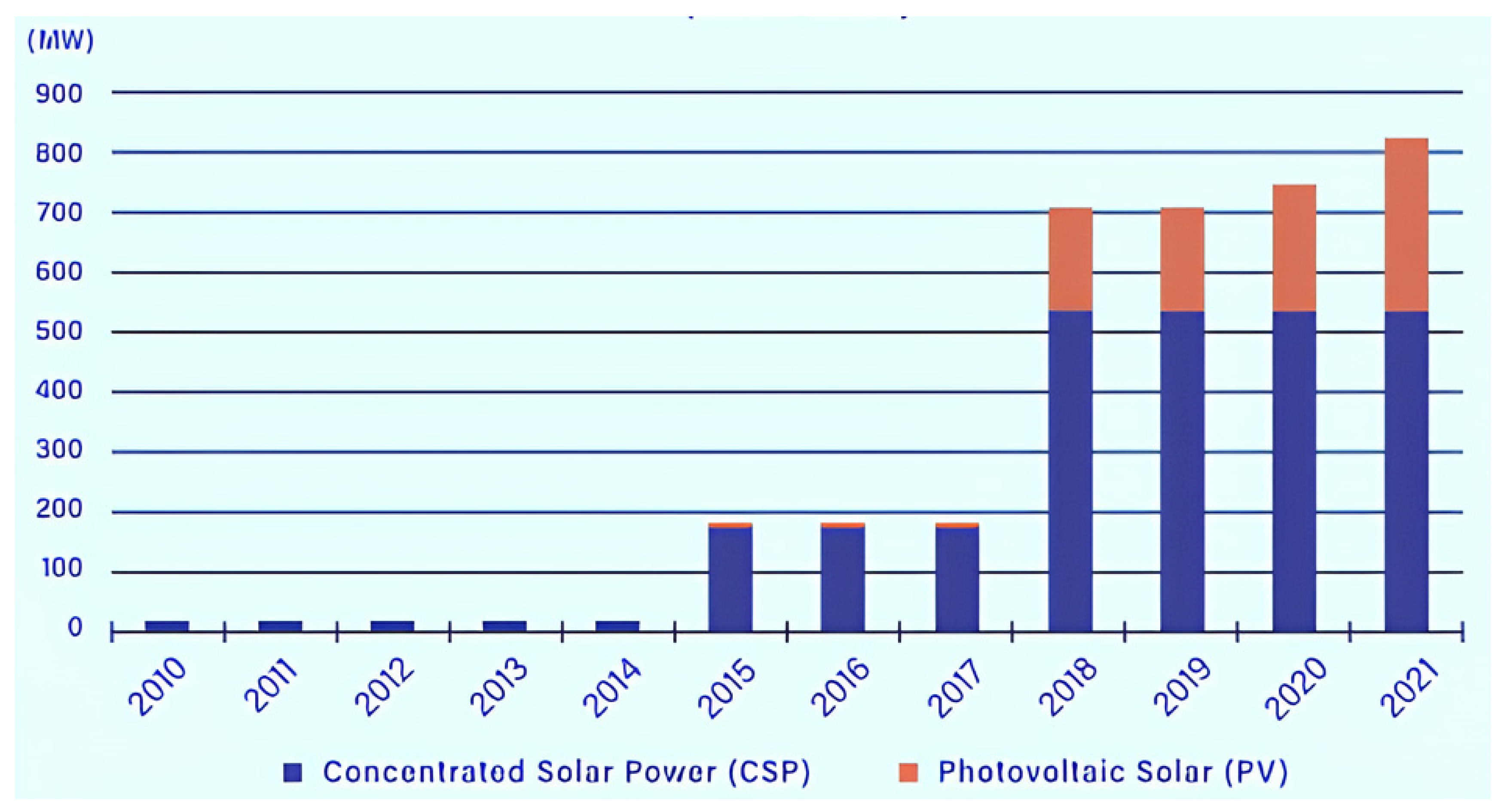

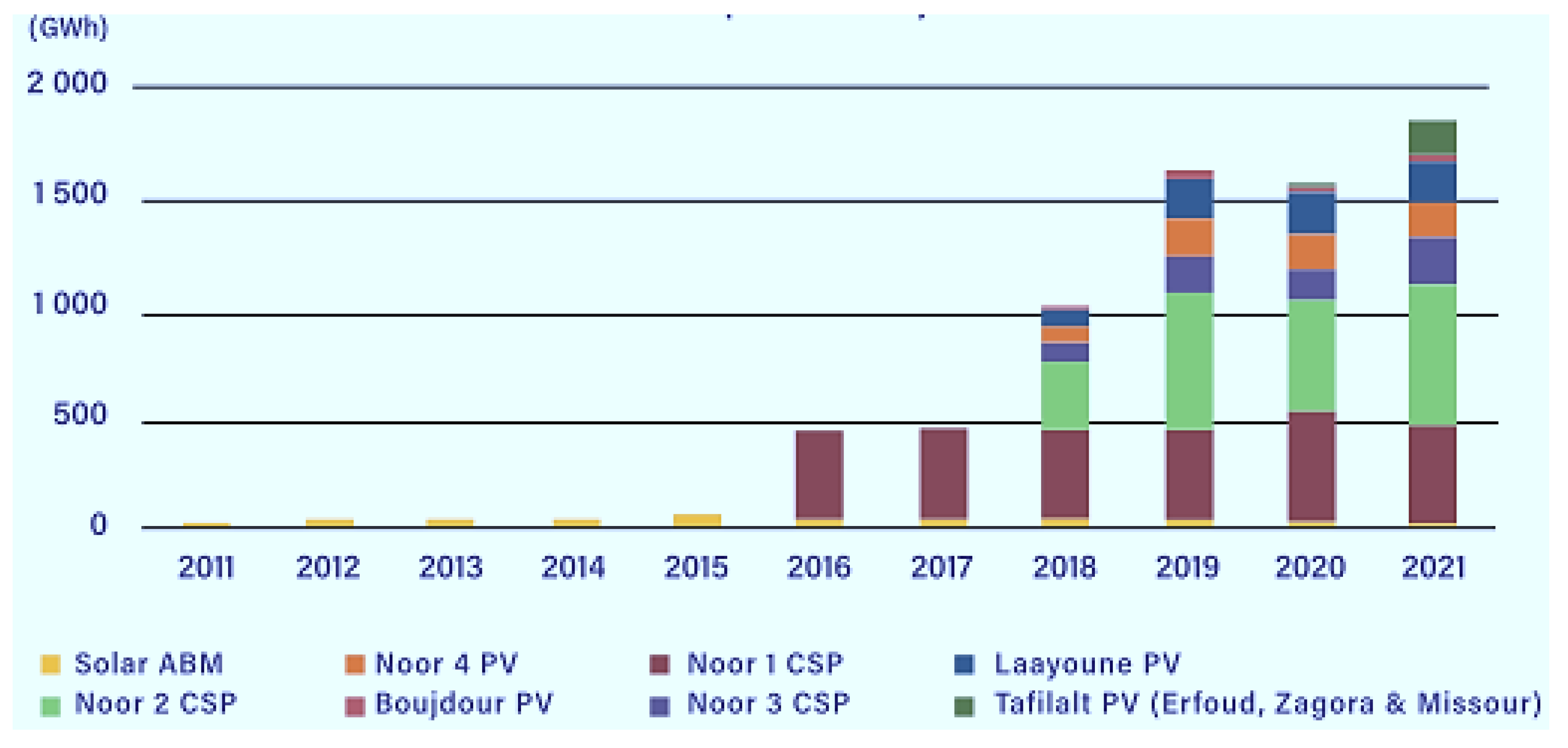

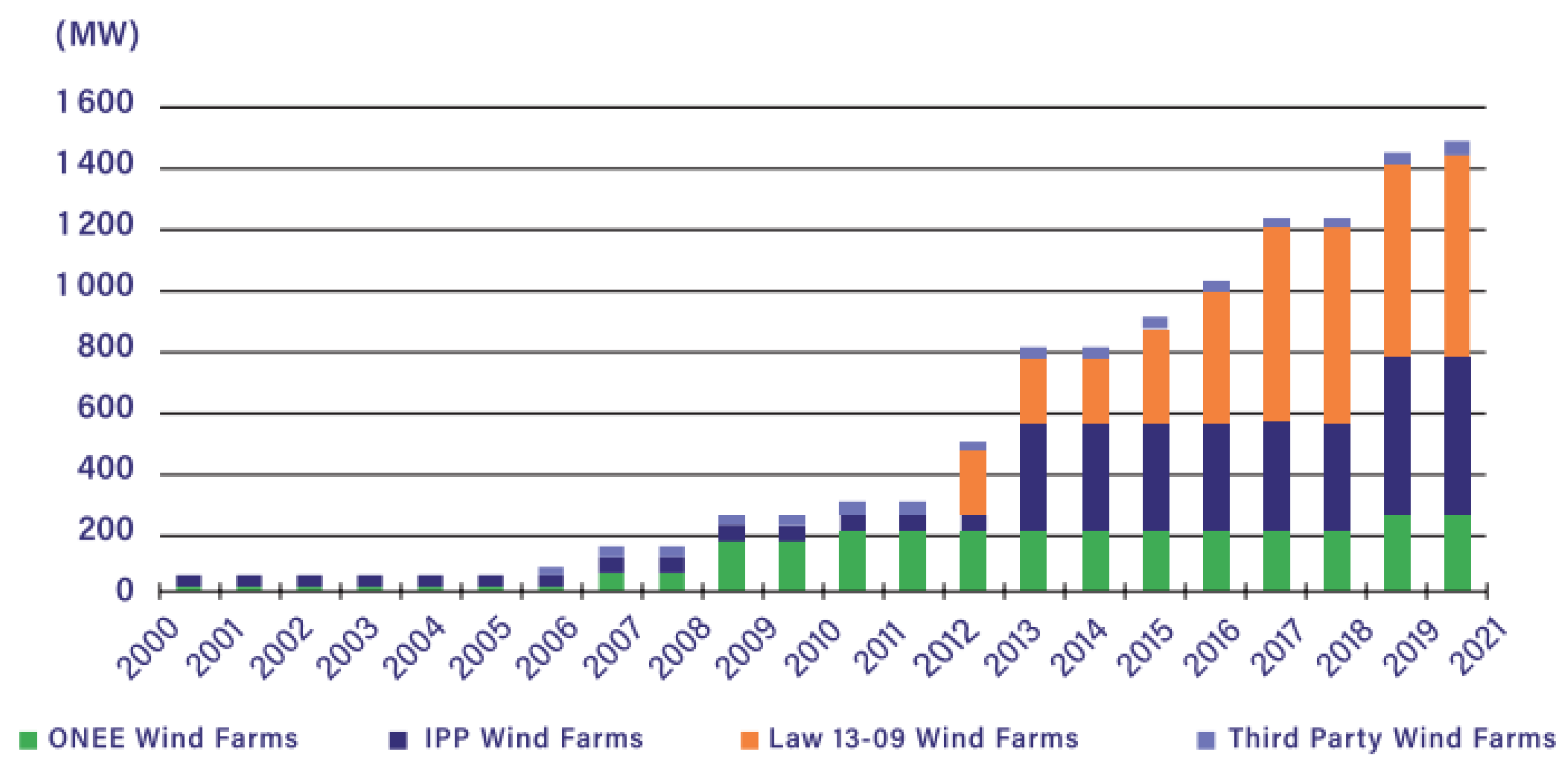

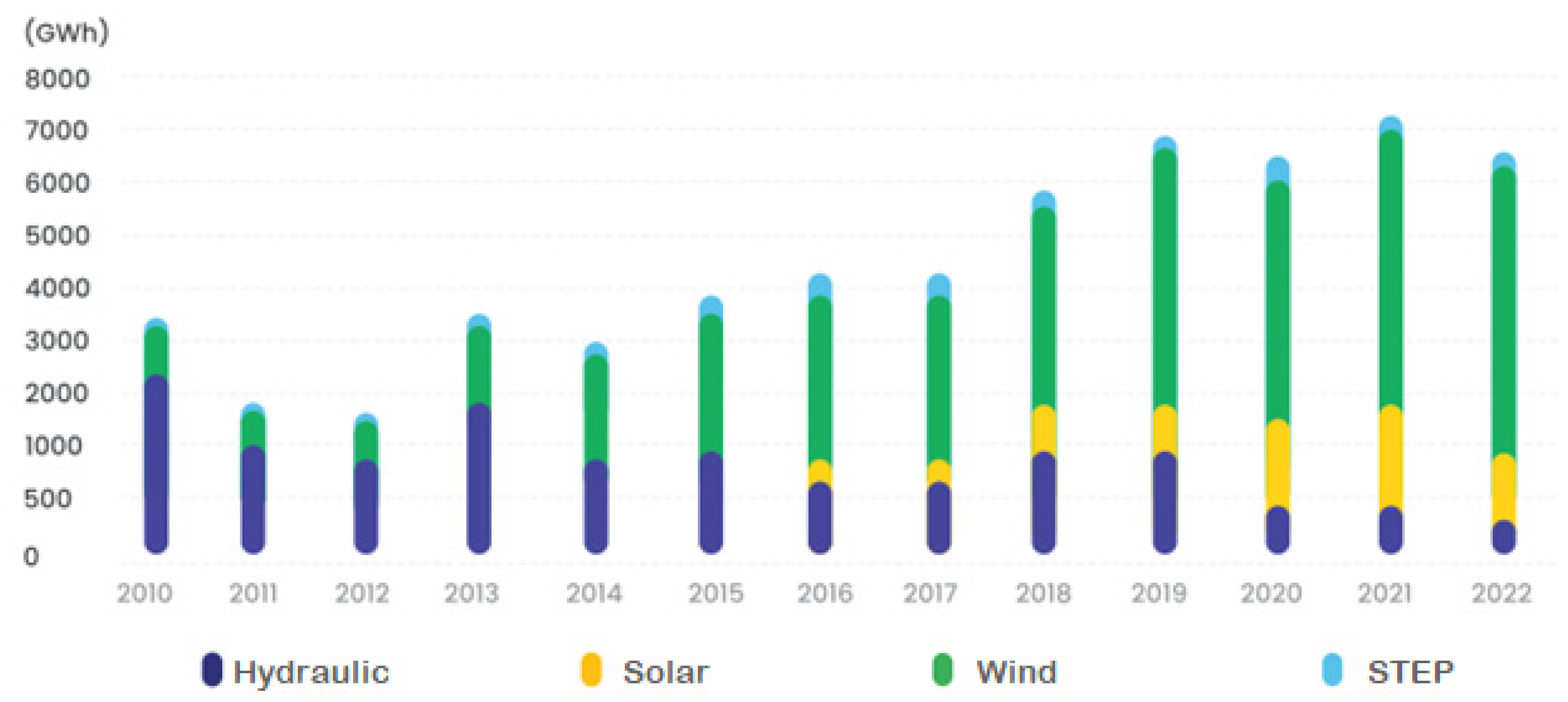

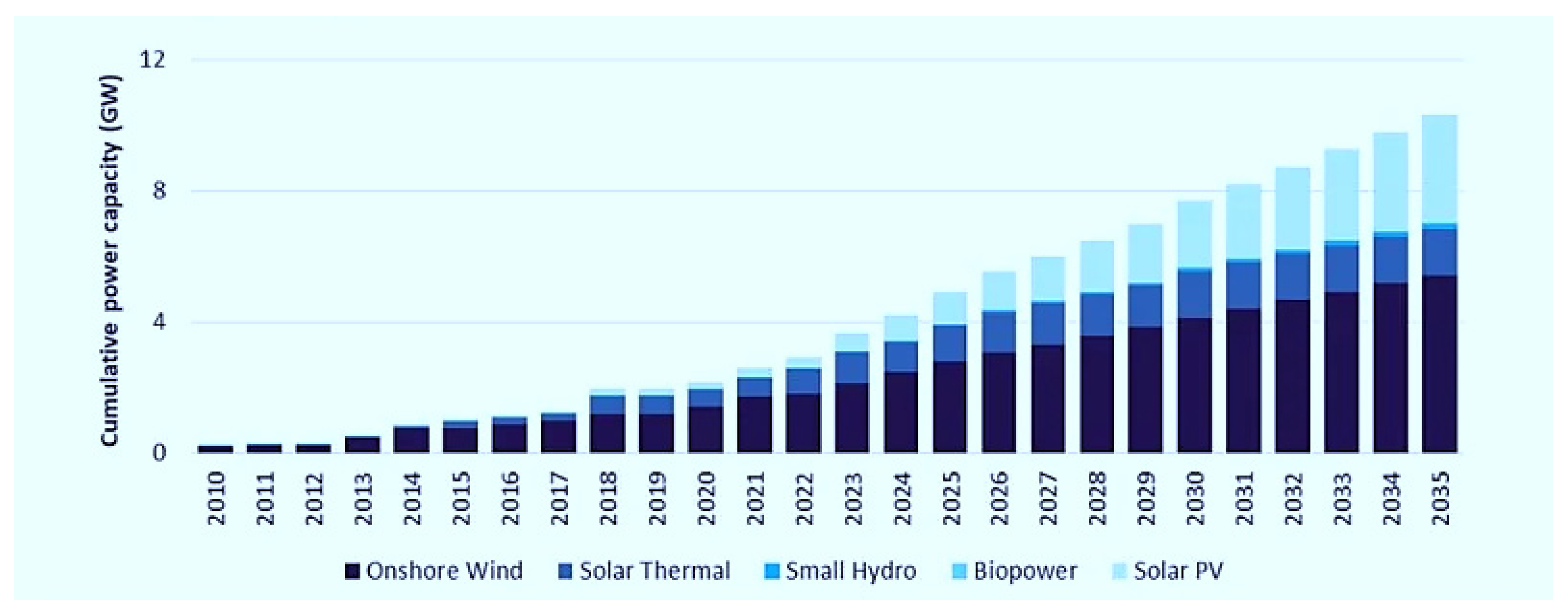

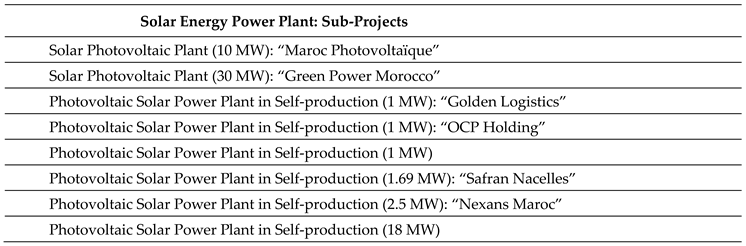

4.2. Installed Capacity

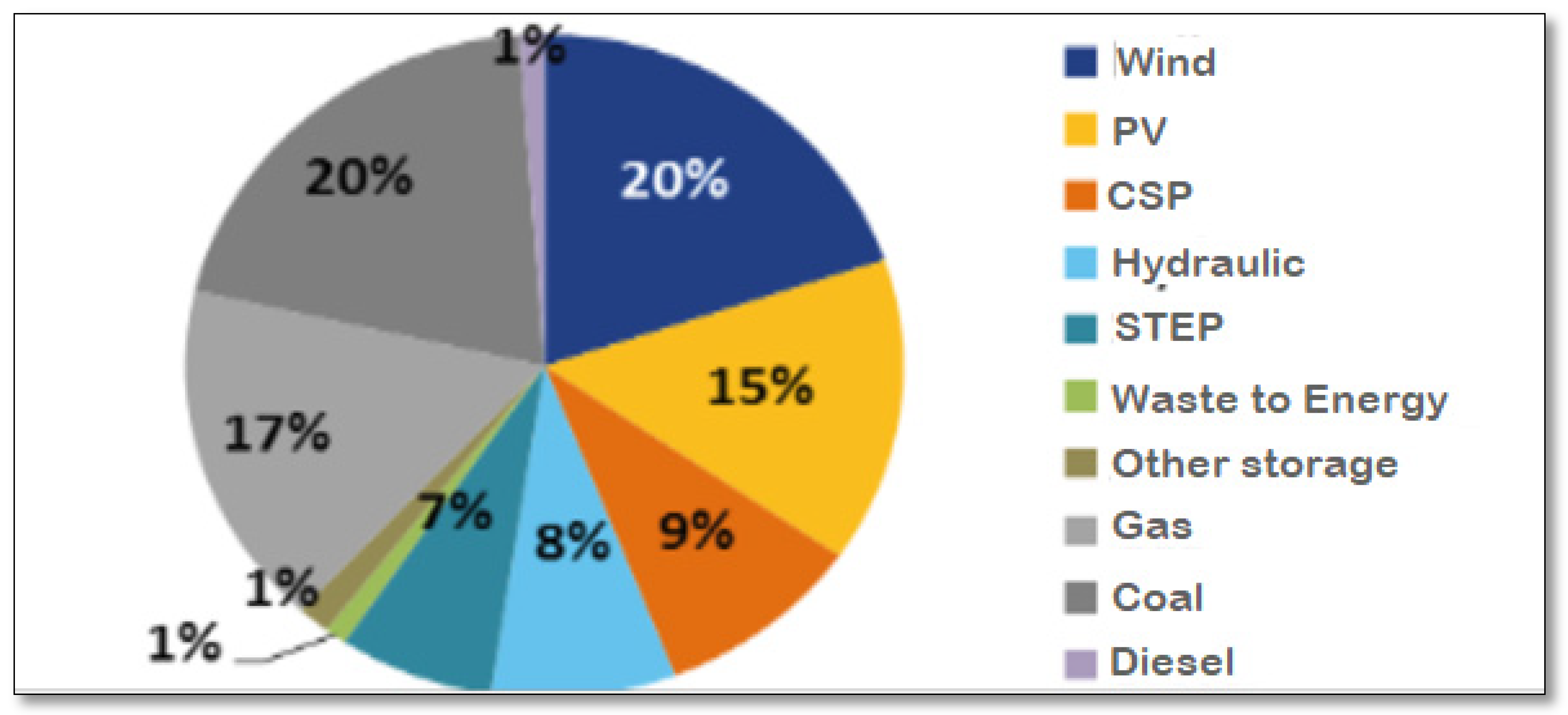

- RE will account for 52% of total installed electrical capacity before 2030, and 70% by 2040.

- By 2030, solar, wind and hydropower are expected to account for 20%, 20% and 12% respectively in the energy mix.10GW of RE must be add between 2018 and 2030: 4560 MW of solar, 4200 MW of wind and 1330 MW of hydropower [33], including those to be carried by the private sector within the framework of Law No. 13-09.

- Investment: 9 billion USD for solar projects

- Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 42% in 2030

- Creation of an industrial base for the solar technologies

- Promotion of capacity building and applied research in PV and CSP technologies (particularly parabolic through and solar tower) and related disciplines.

- Small PV plant in Tit Mellil: 46 kW

- Small PV plant in Ouarzazate: 120 kW

- PV plant in Assa: 800 kW

- PV plant in Kénitra: 2 MW

4.3. Investment and Funding

4.5. Main Challenges and Barriers

5. Future Outlook of Solar Energy in Morocco

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Acronyms

- Ministry for Energy Transition and Sustainable Development (MTEDD). www.mem.gov.ma

- Direction Générale des Collectivités Territoriales (Directorate-General for Local Authorities);

- Moroccan Agency for Energy Efficiency (AMEE) http://www.amee.ma/index.php/en/

- Office National de l’électricité et de l’Eau Potable (Water Branch / Electricity Branch) http://www.one.org.ma

- National Office for Hydrocarbons and Mines (ONHYM)

- ANRE - l’Autorité Nationale de Régulation de l’Électricité: https://anre.ma/en/

- Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy (MASEN), http://www.masen.ma/fr/masen/

- National Inventory Commission (CNI)

- Moroccan Energy Observatory (OME)

- Moroccan Agency for Nuclear and Radiological Safety and Security (AMSSNur)

- National Centre for Nuclear Energy, Science and Technology (CNESTEN)

- Energy Investment Company (SIE), https://www.siem.ma/ which offers consultancy services and assists in project development (energy efficiency, RE) through several actions such as identification of needs, choice of appropriate technologies, financing options, project implementation arrangements, and assessment of the project profitability.

- Société Chérifienne des Pétroles (SCP)

- Institute for Research in Solar Energy and New Energies (IRESEN) for research and innovation, http://www.iresen.org/. The missions of IRESEN include the development and financing of national wide research projects (fund-raising agency) and the development of international collaboration in the sector of solar energy and new energies. Since its creation, IRESEN has financed hundreds of projects and established other research instances (ex. Green Energy Park, Green and Smart Building Institute) in Morocco and Africa.

- Rabat School of Mines National (‘École nationale supérieure des mines de Rabat - ENSMR)

- Moroccan Institute for Standardization (IMANOR)

- Public Testing and Research Laboratory (LPEE)

- Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE)

- 4C Morocco (Platform for dialogue and capacity building on climate issues)

- Concessionary electricity producers. Since 1994, private companies have been authorized to produce electricity solely to meet ONEE’s needs. They are connected to ONEE through long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs). At present, the concessionary electricity producers are: Jorf Lasfar Energy Company, JLEC (2080 MW); Compagnie Éolienne du Détroit, CED (54 MW); Société Energie Électrique de Tahaddart, EET (384 MW); Tarfaya Energy Company, TEC (300 MW) and SAFI Energy Company, SAFIEC (1386 MW).

- Auto-producers Self-generators may produce electrical energy, in one of the following cases, mainly for their own use and the surplus is sold exclusively to ONEE: - The generating capacity to be installed by the producer must not exceed 50 MW; - The generating capacity must exceed 300 MW, with a right of access to the national electricity grid to ensure the transmission of the electrical energy.

- SIE - Société d’Investissement Énergétique: https://www.siem.ma/

- SIE, founded in 2009, is the government’s financial arm for achieving the planned energy mix. The organisation develops projects in the energy sector with the help of partners, investors and developers. SIE has a capacity of 1 billion dirham (around €100 million) available through the Fonds de Développement de l’Électrification (FDE). A quarter of their capacity is allocated to energy efficiency and three quarters to RE.

References

- K. Saidi and B. Mbarek, “Nuclear energy, renewable energy, CO 2 emissions, and economic growth for nine developed countries: Evidence from panel Granger causality tests,” 2016. [CrossRef]

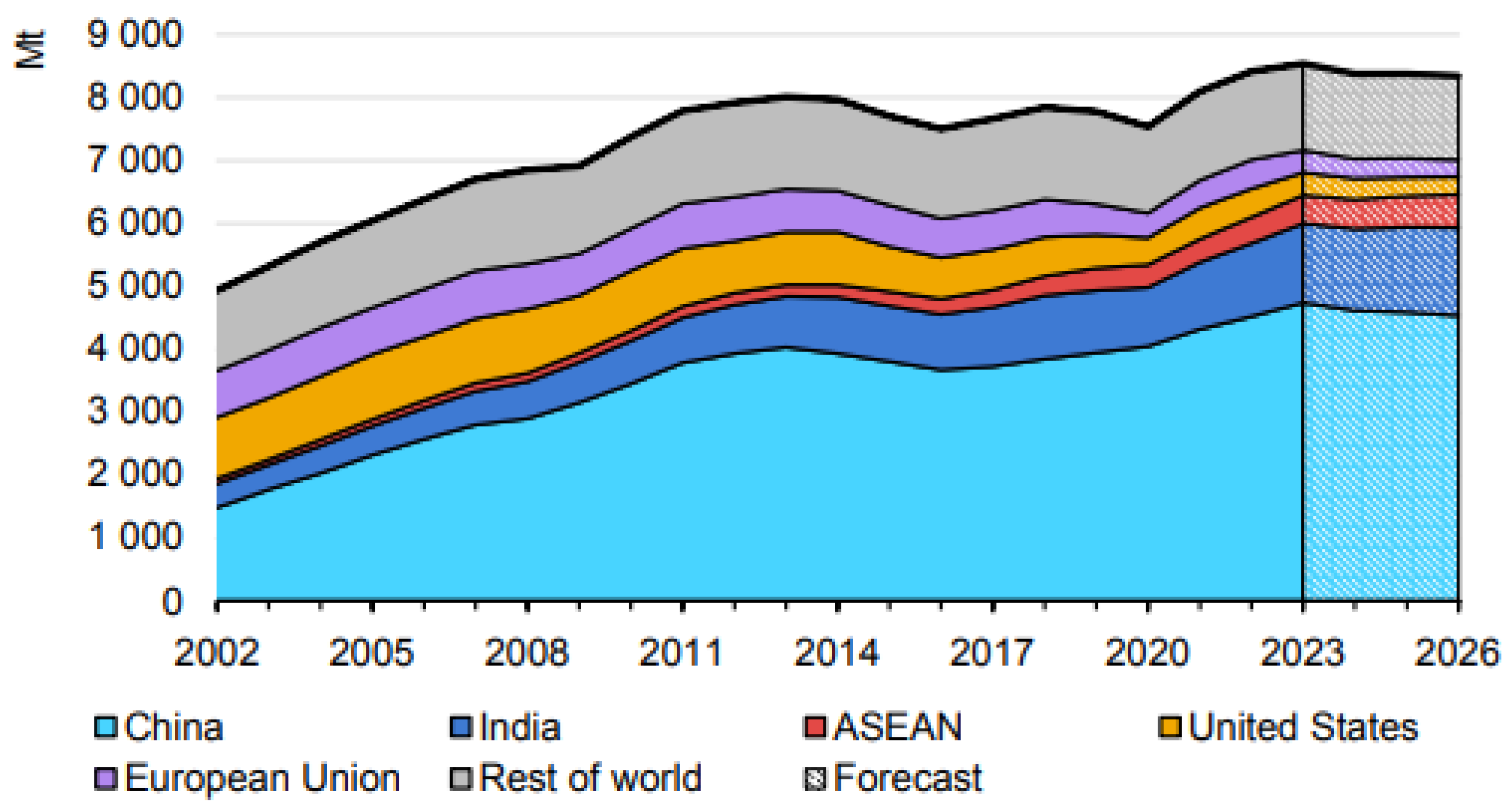

- IEA, “Coal 2023 - Analysis and forcast to 2026,” Int. Energy Agency, pp. 1–170, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/news/global-coal-demand-expected-to-decline-in-coming-years.

- IEA, “CO2-Emissions,” Encycl. Sustain. Manag., pp. 600–600, 2023. [CrossRef]

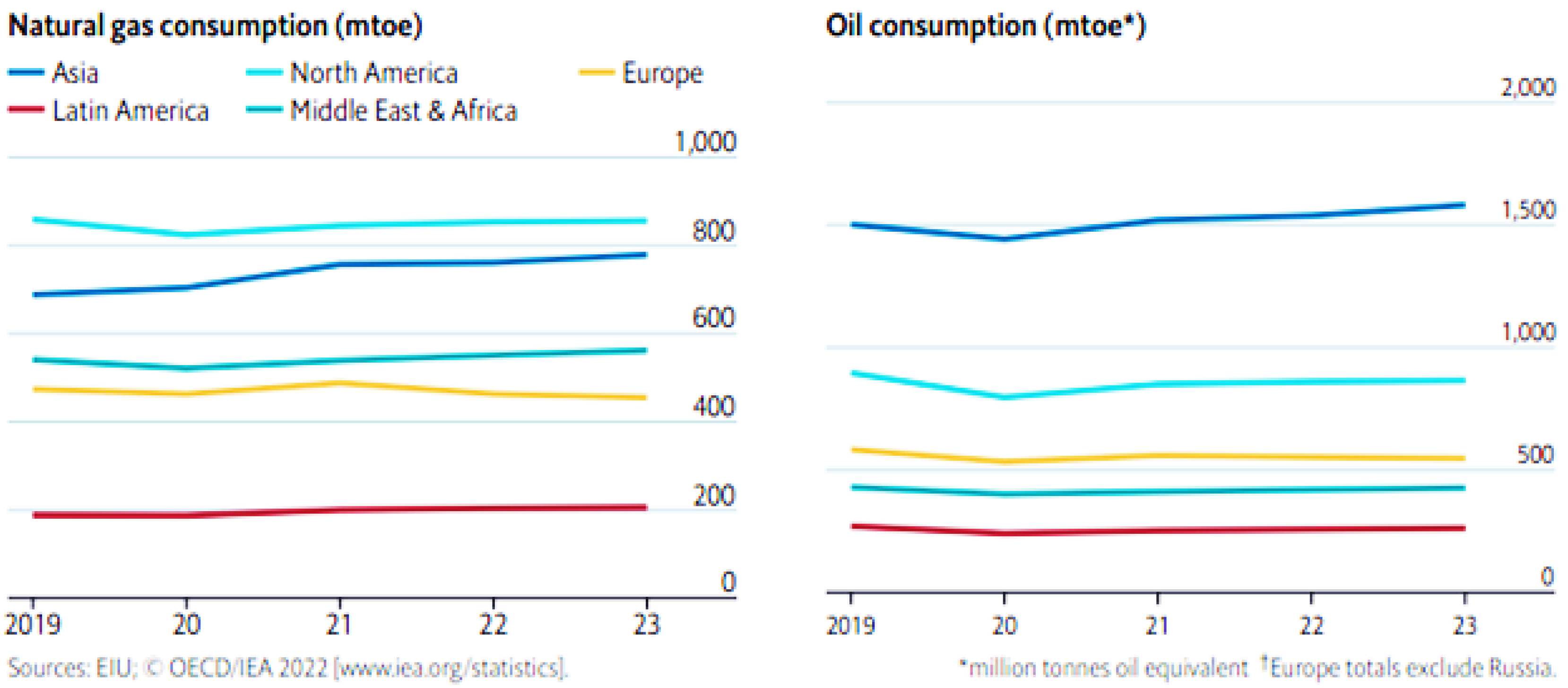

- R. Berahab, “2023_Tendances et perspectives énergétiques à l’horizon 2023,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/2023-01/PB_04_23 %28Rim Berahab%29.pdf.

- IRENA, “A World Energy Transitions Outlook brief TRACKING COP28 OUTCOMES TRIPLING RENEWABLE POWER,” RENA (2024), Track. COP28 outcomes Tripling Renew. power Capacit. by 2030, Int. Renew. Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. Available, 2024, [Online]. Available: www.irena.org/publications.

- A. A. Zeid, “Le Maroc, un champion africain en matière des énergies renouvelables (Amani Abou Zeid),” 2023. https://www.mapnews.ma/fr/actualites/economie/le-maroc-un-champion-africain-en-matière-des-énergies-renouvelables-amani-abou.

- ANRE, “Rapport annuel 2022 anre,” 2022.

- H. Saidi, “développement Renewable energy in Morocco in the era of the new development model,” vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 155–171, 2022.

- D. Ben Mohamed, “Énergies renouvelables : le Maroc, un leader aux portes de l’Europe,” 2023. https://forbesafrique.com/energies-renouvelables-le-maroc-un-leader-aux-portes-de-leurope/.

- A. Šimelytė, Promotion of renewable energy in morocco. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Azeroual, A. El Makrini, H. El Moussaoui, and H. El Markhi, “Renewable energy potential and available capacity for wind and solar power in Morocco towards 2030,” J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 189–198, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Vidican, “The emergence of a solar energy innovation system in Morocco: A governance perspective,” Innov. Dev., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 225–240, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Nakach, O. Mouhat, R. Shamass, and F. El Mennaouy, Review of strategies for sustainable energy in Morocco, vol. 26, no. 2. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Boulakhbar et al., “Towards a large-scale integration of renewable energies in Morocco,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 32, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kettani, J. D. M. Kettani, J. D. De Lavergne, and M. E. Sanin, “HUB SOLAIRE Énergie solaire au Maroc : vers un leadership régional ?,” pp. 37–61, 2021.

- International Trade Administration, “Morocco - Energy - International Trade Administration,” 2023.

- A. Bennouna, “Maroc – 2023 verra sans doute une petite baisse des émissions de gaz à effet de serre Besoins en énergie primaire et émissions de GES associées,” no. July, pp. 9–11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Bennouna, “Energie au Maroc, quoi de neuf en 2022 ?,” Webmagazine EcoActu, no. April, pp. 2–7, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Bennouna, “The State of Energy in Morocco,” Reg. Program. Energy Secur. Clim. Chang. Middle East North Africa Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., no. May, pp. 1–31, 2023.

- Haut Commissariat au Plan, “Morocco in figures,” Haut-comissariat au plan, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/en/mdl-20203177951%0Ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0887-9%0Ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z%0Ahttps://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193%0Ahttp://sersc.org/journals/index.php/IJAST/article.

- D. Lee and A. Rae, “Key Highlights Throughout 2022 and Post Period End.,” no. January 2022, 2023.

- IEA, “Electricity Market Report,” Electr. Mark. Rep., 2020. [CrossRef]

- ANRE, “2021 | 1,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- PAGE, “La transition du maroc vers une économie verte : Etat des Lieux et Inventaire.,” 2022.

- ONEE, “Bilan Electrique Marocain 2023,” 2023, [Online]. Available: http://www.one.org.ma/.

- Z. Romani, A. Draoui, and F. Allard, “Metamodeling the heating and cooling energy needs and simultaneous building envelope optimization for low energy building design in Morocco,” Energy Build., 2015. [CrossRef]

- PEED, “Support de SenSibiliSation Sur l’efficacité énergétique danS leS bâtimentS au maroc,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.peeb.build/imglib/downloads/PEEB_efficacite-energetique-dans-les-batiments-au-maroc_support-de-sensibilation.pdf.pdf.

- A. Laaroussi, “The Energy Transition in Morocco The energy transition in Morocco,” no. January 2020, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. and al Nascimento, “2024 CCPI Climate Change Performance Index,” 2024, [Online]. Available: https://www.legambiente.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/CCPI_-2024.pdf.

- F. Van Eynde, “Flanders investment & trade market survey,” p. 71, 2018, [Online]. Available: https://www.flandersinvestmentandtrade.com/export/sites/trade/files/market_studies/Australia-Food and Beverage Industry 2019.pdf.

- A. Alhamwi, D. Kleinhans, S. Weitemeyer, and T. Vogt, “Moroccan National Energy Strategy reviewed from a meteorological perspective,” Energy Strateg. Rev., vol. 6, no. March, pp. 39–47, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Roadmap Green Hydrogen, “Feuille de route: Hydrogène vert,” p. 93, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.mem.gov.ma/Lists/Lst_rapports/Attachments/36/Feuille de route de hydrogène vert.pdf.

- IEA, “Energy Policies Beyound IEA Countries,” Int. Energy Agency, p. 221, 2019, [Online]. Available: https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/sites/default/files/pdf-actualites/Energy_Policies_beyond_IEA_Contries_Morocco.pdf.

- L. ’ Renouvelables and Efficacite, “Projet Eolien Parc Morocco financing,” Flanders Invest. Trade, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.flandersinvestmentandtrade.com/export/sites/trade/files/market_studies/LE SECTEUR DES ENERGIES RENOUVELABLES ET LEFFICACITE ENERGETIQUE AU MAROC-2021.pdf.

- MOHAMED, “ThsedeDoctorat-Gisements solaires et éoliens au Maroc : estimation et évaluation par intelligence artificielle et systèmes d’information géographique,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362314063_Gisements_solaires_et_eoliens_au_Maroc_estimation_et_evaluation_par_intelligence_artificielle_et_systemes_d’information_geographique/citations.

- S. HIDANE, A. HarBa, J. BENHAMDAN, F. Z. MOKHTARI, and M. EL ALLAM, “Industries des énergies renouvelables - région Casa Settat,” 2023. [Online]. Available: www.amee.ma.

- T. Bouhal et al., “Technical feasibility of a sustainable Concentrated Solar Power in Morocco through an energy analysis,” vol. 81, no. June 2017, pp. 1087–1095, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Masen.ma, “Atlas de la Ressource Solaire au Maroc (masen.ma).” https://solaratlas.masen.ma/map?c=29.61167:-9.074707:5&s=31.625815:-7.989137&m=masen:pvout.

- Z. Usman and T. Amegroud, “Lessons from Power Sector Reforms The Case of Morocco,” no. August, 2019.

- IRENA, Renewable Generation Costs in 2022. 2022.

- IRENA, Renewable Capacity Statistiques 2023. 2023. [Online]. Available: www.irena.org/publications.

- IRENA, Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2020. 2020.

- IEA, “World Energy Outlook 2023,” IEA Publ., pp. 23–28, 2023, [Online]. Available: www.iea.org.

- T. Mrabti et al., “Implantation et fonctionnement de la première installation photovoltaïque à haute concentration ‘CPV’ au Maroc,” J. Renew. Energies, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 351–356, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Barhdadi, “CPV technology for Moroccan solar energy project CPV technology for Moroccan solar energy project,” no. June 2013, 2015.

- Masen, “PLAN D ’ ACQUISITION DE TERRAIN,” no. Pat 1, pp. 1–18, 2016.

- MEMEE, “Contribution Déterminée au niveau National-actualisée,” Ministère l’Energie des Mines l’Eau l’Environnement du Maroc, p. 36, 2021, [Online]. Available: Ministère de l’Energie des Mines de l’Eau et de l’Environnement du Maroc.

- M. P. Stoelting, “Developpement Des Energies Solaire Et Eolienne Au Maroc Enseignements Et Perspectives,” 2020.

- M. Yaneva, “OVERVIEW - Morocco to add 4 GW of wind, solar capacity by 2020,” 2017. https://renewablesnow.com/news/overview-morocco-to-add-4-gw-of-wind-solar-capacity-by-2020-555087/.

- G. Vidican, M. Böhning, G. Burger, E. de S. Regueira, and S. Müller, Achieving inclusive competitiveness in the emerging solar energy sector in Morocco, vol. 79, no. December 2013. 2013. [Online]. Available: http://www.die-gdi.de/en/studies/article/achieving-inclusive-competitiveness-in-the-emerging-solar-energy-sector-in-morocco/.

- K. Mergoul, B. Laarabi, and A. Barhdadi, “Solar water pumping applications in Morocco: State of the art,” Proc. 2018 6th Int. Renew. Sustain. Energy Conf. IRSEC 2018, no. May 2019, 2018. [CrossRef]

- men.gov.ma, “Renewable energy -Solar.” https://www.mem.gov.ma/Pages/secteur.aspx?e=2&prj=3.

- Barradi Touria, “Un Aperçu De La Situation De L’Efficacité Énergétique Des Ménages Au Maroc,” 2019, pp. 10–11, 2019, [Online]. Available: http://www.abhatoo.net.ma/maalama-textuelle/developpement-economique-et-social/developpement-economique/energie-et-mines/energie-et-mines-generalites/un-apercu-de-la-situation-de-l-efficacite-energetique-des-menages-au-maroc.

- F. Z. Gargab, A. Allouhi, T. Kousksou, H. El-Houari, A. Jamil, and A. Benbassou, “A new project for a much more diverse moroccan strategic version: The generalization of solar water heater,” Inventions, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–25, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Benoit-Ivan, “MOROCCO: In the suburbs of Rabat, a factory will manufacture solar water heaters,” 2023. https://www.afrik21.africa/en/morocco-in-the-suburbs-of-rabat-a-factory-will-manufacture-solar-water-heaters/.

- P. H. Vedie, “Les énergies renouvelables au Maroc : un chantier de Règne,” pp. 1–10, 2020.

- men.gov.ma, “HYDROELECTRICITY.” https://www.mem.gov.ma/Pages/secteur.aspx?e=2&prj=2.

- K. Veysel, “Investment Opportunities in Morocco’s Energy Sector,” 2024. https://www.netzerocircle.org/articles/investment-opportunities-in-moroccos-energy-sector.

- S. Zafar, “Renewable Energy in Morocco,” 2022. https://www.ecomena.org/renewable-energy-in-morocco/.

- L. Bennis, “La finance verte au Maroc : enjeux et perspectives à l ’ ère du changement climatique Green finance in Morocco : challenges and perspectives in the era of climate change,” vol. 4, pp. 29–61, 2023.

- AMEE, “GUIDE DES PROGRAMMES DE FINANCEMENT ET D ’ APPUI POUR,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.amee.ma/sites/default/files/inline-files/Guide des Programmes de Financement et D%27appui pour les Entreprises Marocaines.pdf.

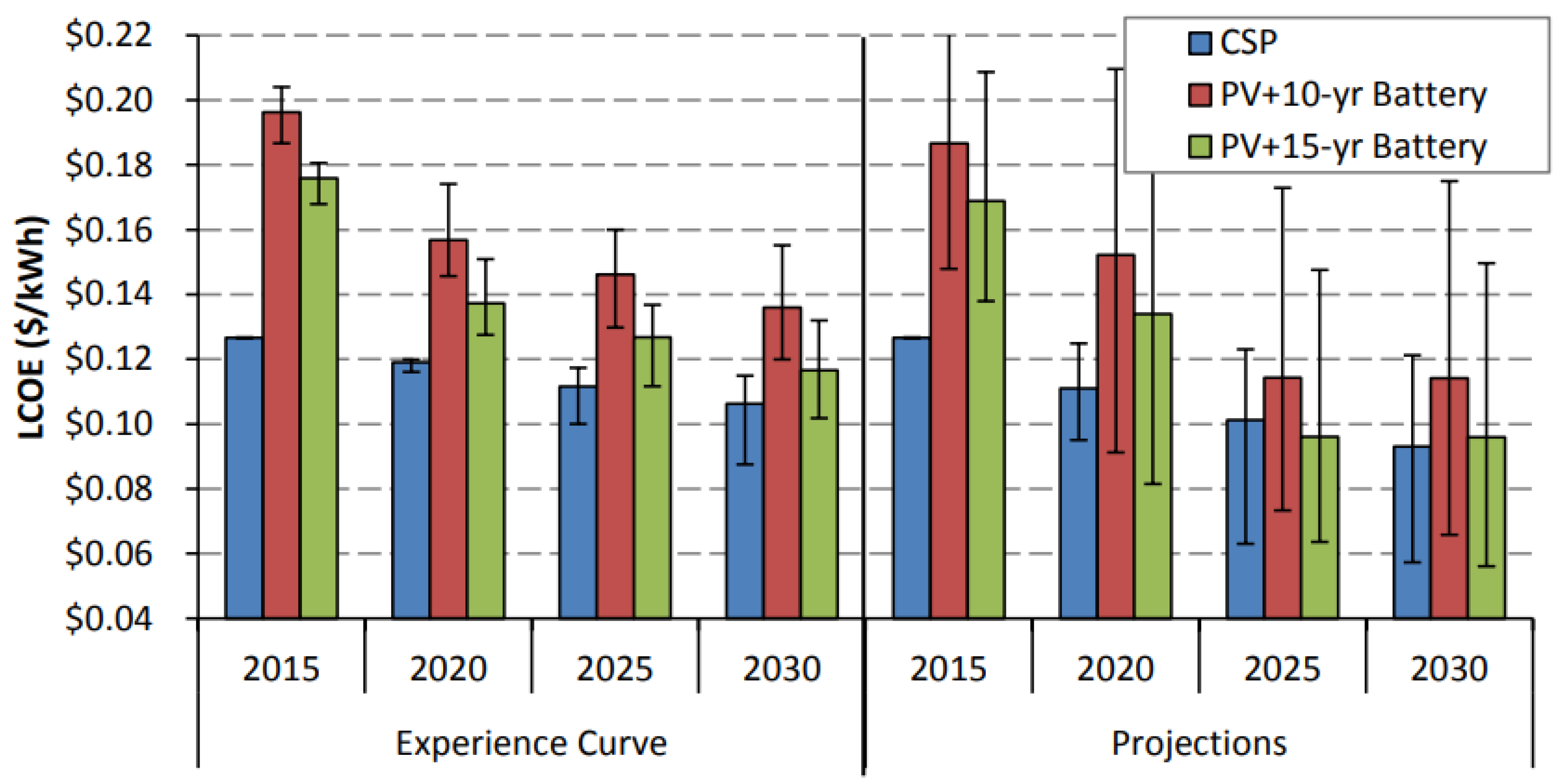

- Feldman et al., “Exploring the Potential Competitiveness of Utility-Scale Photovoltaics plus Batteries with Concentrating Solar Power, 2015 – 2030,” U.S. Dep. Energy, no. August, pp. 1–31, 2016.

- J. Heuzebroc, “Pénurie d’eau : le Maroc tire le signal d’alarme.” https://www.nationalgeographic.fr/environnement/penurie-deau-le-maroc-tire-le-signal-dalarme.

- IRES Maroc, “‘Quel Avenir De L’Eau Au Maroc ?’ Rapport De Synthese Des Travaux De La Journee Scientifique Du 17 Mars 2022,” 2022.

- M. Kettani and P. Bandelier, “Techno-economic assessment of solar energy coupling with large-scale desalination plant: The case of Morocco,” Desalination, vol. 494, no. August, p. 114627, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Law | Main points |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Project Name | Installed Capacity /Annual Production / LCOE | Location | Technology/ Storage Technology |

CO2 Avoided TCO2/year | Project Framework | Investment cost (MDH) | Planned start-up date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ain Beni Mathar | 20 MW / 55 GWh/yr./ 2.4 MAD/kWh | Beni Mathar | ISCC + Parabolic trough | - | ONEE | - | 2018 |

| Noor Ouarzazate I | 160 MW /618 GWh/yr./1.62 MAD/kWh | Ouarzazate | CSP (Parabolic trough) 3h of Storage Molten Salt with 2 tank |

280,000 | Managed by Masen and the construction, operation and maintenance have been awarded to the consortium led by ACWA Power. |

7000 | 2016 |

| Noor Ouarzazate II | 200 MW/ 600 GWh/yr. 1.36 MAD/kWh |

Ouarzazate | Parabolic trough + dry cooling 7h of Storage Molten Salt with 2 tank |

300,000 | 9218 | 2018 | |

| Noor Ouarzazate III | 150 MW/ 500 GWh/yr. 1.42 MAD/kWh |

Ouarzazate | CSP Power Tower + dry cooling 7h of Storage Molten Salt with 2 tank |

222,000 | 7180 | 2018 | |

| Noor Ouarzazate IV | 72 MW /120 GWh/yr. 0.46 MAD/kWh |

Ouarzazate | polycrystalline PV with Tracking - |

86,539 | 775 | 2018 | |

| Noor Laayoune I | 85 MW /200 GWh/yr. 0.46 MAD/kWh |

Laayoune | polycrystalline PV with Tracking | 104,300 | 968 | 2018 | |

| Noor Boujdour I | 20 MW / 45 GWh/yr. 0.46 MAD/kWh |

Boujdour | polycrystalline PV with Tracking |

23,855 | 302 | 2018 | |

| Noor Boujdour II | 350 MW | Polycrystalline PV |

- | - | Will be operated by 2027) | ||

| Noor Tafilalt | 120 MW/ 220 GWh/yr. | Erfoud | Polycrystalline PV | 102,045 | ONEE, developed within the concessional and contractual framework | 1200 | Last 2020 |

| Missour | 2021 | ||||||

| Zagora | 2021 | ||||||

| Noor Midelt I | 800 MW ≈ 0,68 MAD/kWh |

Midelt | Hybrid System CSP Parabolic trough (300 MW)/ PV (500 MW) 5h of storage |

675,360 | Consortium EDF/MASDAR(EAU)/ Green of Africa (Morocco) | 7572 | Planned on 2024 |

| Noor Midelt II | 400 to 800 MW | - | Planned on the horizon of 2030 | ||||

| Noor Atlas | 200 MW distributed on 8 power plants of 30 to 40 MW. 320 GWh/yr. |

Boudnib, Bouanane, Outat El Haj, Enjil, Ain Beni Mathar, Tata, and Tan Tan. | Polycrystalline PV | 204,090 | ONEE developed within the concessional and contractual framework |

2000 | Constructed in 2021 Planned on 2024 |

| Solar Program Noor PV II | 750 MW (distributed on 7 power plant) | Ain Beni Mathar, El Hajeb, Bajaad, Sidi Bennour, Kalaa Sraghna, Taroudant, Guersif | Polycrystalline PV | - | 400 MW will be developed within the framework of law n°13-09 | - | From 2023 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).