Introduction

Lettuce (

Lactuca sativa L.) belongs to the plant family

Asteraceae and is one of the most widely consumed leaf vegetables worldwide. Among the diseases of lettuce, lettuce drop is one of the most common and destructive diseases in lettuce production throughout the lettuce producing in Bulgaria and other lettuce-growing regions of the world (Hao and Subbarao, 2003) [

1]. Diseases are considered a major restrictive factor to lettuce production with only a few resistant cultivars available (Abawi et al. 1980; Whipps et al. 2002, Mamo et al. 2019) [

2,

3,

4]. The losses due to this disease vary from 10% to 75 % depending on cultural (cropping history, irrigation, and cultivation methods) and environmental factors (Foley et al. 2016) [

5]. One of the pathogens that causes Lettuce drop is

Sclerotinia minor which produces only soil-born mycelia (Grube and Ryder, 2004) [

6]. Current management strategies of

Sclerotinia spp. in lettuce are similar to management programs for control rely on breeding disease resistance cultivars and mostly on heavy reliance on chemical applications.

Sclerotinia spp. produces sclerotia that can survive in soil for more than 8 years without a host. Sclerotia of

S. minor are quite small (0.5 - 2 mm diameter) and primarily germinate eruptive, producing infective mycelia that penetrate lettuce plants only nearby. Sclerotinia minor is believed to be a heterothallic, a condition in which male and female reproductive structures are produced in different thallus, and require sexual mating between two compatible isolates for the production of apothecia. Therefore, the fungus infects plants primarily by hyphae from myceliogenic germination of sclerotia (Imolehin et al. 1980) [

7]. The development of sclerotia also depends on several factors like location of sclerotia along the soil profile, moisture, temperature, and microflora in the soil (Hao et al. 2003) [

8]. In Bulgaria, the management of

Sclerotinia fungi relies primarily on the strategic application of synthetic fungicides. In an attempt to find alternative strategies for the management of the disease, four naturally occurring bacterial isolates were screened for antagonism to this pathogen. Biological control is a result of interaction among microorganisms and includes mycoparasitism, antibiosis, competition for site and nutrient and induced resistance. It is one of the most important non-chemical strategies evaluated for the management of several plant pathogens in several cropping systems. Against diseases, several mycoparasites that attack both sclerotia and mycelia of

Sclerotinia spp., have been evaluated both in laboratory and field conditions by utilization of Trichoderma spp. (Jones and Stewart, 1997) [

9],

Sporidesmium sclerotivorum (Del Rio et al. 2002) [

10], and

Coniothyrium minitans (Partridge et al. 2006).

Trichoderma spp., are perhaps the most widely used mycoparasites and numerous commercial formulations exist (Elias et al. 2016) [

11]. Although, many studies have been conducted to determine the effects of chitinolytic fungi on the growth and development of several fungal pathogens. Larena and Melgarejo, 1996 [

12] applied chitinolytic actinomycetes and bacteria for the control of lettuce drop disease with possible production of chitinase, β-1,3-glucanase, and diffusible and volatile antifungal metabolites. Prokaryotic cells, under iron-limited conditions, certain fungi and plants elaborate multiple low-molecularweight siderophores (often < 1000 Da), high-affinity chelating agents, which solubilizes ferric iron in the environment and transport it into the cell (Crosa and Walsh, 2002) [

13]. Siderophore-producing bacteria have been used as biocontrol agents to combat plant pathogens (Gram, 1996) [

14]. Growth of some species may be inhibited and this has been attributed to be one of the mechanisms by which biocontrol agents act in inhibiting the growth of pathogens in the rhizosphere (Kiyohara et al., 1982) [

15]. Bacillus subtilis QM3, a siderophore producer, investigated in this paper was illuminated to be a potential biocontrol agent (Hu et al., 2008) [

16].

Studies of biological control of lettuce drop using bacterial antagonists

Pseudomonas chlororaphis and

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens were conducted by Fernando et al. 2007 and Saharan and Mehta 2008 and a significant reduction of

Sclerotinia infection has been observed [

17,

18]. Antagonistic bacteria inhibit the germination of ascospores through the production of antimicrobial substances like cyclic lipopeptides, such as iturin, fengycin, surfactin (Sabaté et al. 2008; Alvarez et al. 2012) [

19,

20] and siderophores (Ribeiro et al. 2021) [

21] on ascospores growth and development. This investigation focuses mainly on the development of biocontrol strategies as the main component of integrated disease management for the management of lettuce drop in greenhouse production. This study reports the in vitro evaluation of the antifungal activity of B. subtilis, B. megaterium, B. safensis, and B. mojavensis against

S. minor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria

B. subtilis JAN25-4 accession OR731944.1, B. megaterium JAN33-2 accession OR731941.1 (NCBI submission sub13929898/ 29.10.2023) and B. safensis CAM24K3 with accession PP797578.1 and B. mojavensis CAM23K1 accession PP797576.1 (NCBI submission sub14450584/ 08.06.2024, were isolated from soil intercropping with camelina (Camelina sativa L.) and vetch (Vicia sativa L.) on the experimental field of Agricultural University Plovdiv.

2.2. Amylolytic Activity of Tested Bacillus Strains

The isolated four different strains of the genus

Bacillus were qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated for the presence of amylolytic activity by the agar diffusion method (Agati et al., 1998) [

22]. Starch agar plate, g/L: wheat starch – 10; peptone – 5; yeast extract – 5; MgSO

4.7H

2O – 0.25; FeSO

4.7H

2O – 0.01; agar –15; pH 6.8 ± 0.2. In the agar-diffusion method, the nutrient medium is poured in 15 cm

3 and after solidification in the petri dish, 4 wells with a diameter of 8 mm are made. For each strain, two samples were prepared: CM-culture medium from a 24-h suspension of the strain and CFS-cell-free supernatant obtained by centrifugation of culture fluid at 5000 x g (Universal 320 R, Marvel Ltd.). The bacterial suspension or CFS from each isolate was instilled in 100 µl. After incubation at 30°C for 48 h, the Petri dishes were treated with Lugol's solution (3% KI) to form a blue-colored starch-iodine complex. A halo area is observed around the amylolytic bacterial colonies. The result is reported by measuring the diameter of the formed halo zone in mm.

2.3. Proteolytic Activity of Bacillus Strains

The proteolytic activity of tested bacteria was tested by inoculation on milk agar according to Nabrdalik (2010) [

23] containing: casein 0.5%, yeast extract 0.25%, dextrose 0.1%, skimmed milk powder 2.5% and agar 1.5%. Bacterial isolates were pre-activated in TSA broth. The proteolytic activity of each strain was investigated as culture fluid - CM obtained from 24 h culture and cell-free supernatant - CFS obtained by centrifugation of culture fluid. Wells with a diameter of 9 mm were formed on agar medium with added skimmed milk, in which 100 µl of the previously prepared cultures and cell-free extracts were placed. The samples were cultured at 30°C and the result as the diameter of the proteolytic zones measured in mm was reported after 24, 48, and 72 hours (Petkova et al. 2020) [

24].

3. Quantification of the Synthesized Secondary Metabolites with Phytohormonal Activity

The synthesis of microbial phytohormones by soil microorganisms is associated with signal changes in the root and stimulation of plant growth. The presence of a particular phytohormone in the microbial culture supernatant is insufficient to prove the molecule's functional role in its interaction with the plant. A number of studies have observed a correlation between plant growth and hormone concentration measured in the culture medium or in colonized plant tissues in experiments and

in situ (Spaepen, 2015) [

25].

3.1. Quantification of Indole-3-Acetic Acid Using the Salkowski Reagent

For quantification of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) produced, bacterial isolates were grown in a tube in medium with or without 0.1% (w/v) L-tryptophan (L-Trp) and incubated in the dark at 30°C and for 5 days as was published previously by Petkova et al. 2022 [

26]. One milliliter of the cells was pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 g for 5 min, and 0.5 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.5 mL of Salkowski's reagent (2 mL of 0.5 M iron (III) chloride and 98 mL of 35% perchloric acid) (Gordon & Weber 1951) [

27]. After 30 min, color development (red) was quantified using a spectrophotometer (Unico 1200-Spectrophotometer, USA) at 530 nm. A calibration curve using pure indole-3-acetic acid was established to calculate IAA concentration. IAA production of each bacterial isolate was determined by inoculating L-tryptophan medium containing 0.1% (w/v) L-tryptophan with and incubated in the dark at 20 C. After incubation, the IAA produced was quantified spectrophotometrically.

3.2. Screening for Dissolution of Inorganic Phosphates

Screening for dissolution of inorganic phosphates was performed using Pikovskaya's medium (PVK) as was published by Patil, 2014 [

28] containing: glucose, 10 g; Ca(PO

4)

2, 5 g; (NH

4)

2SO

4 , 0.5 g; NaCl, 0.2 g; MgSO

4·7H

2O, 0.1 g; KCl, 0.2 g; yeast extract, 0.5 g; MnSO

4·H

2O, 0.002 g; and FeSO

4·7H

2O, 0.002 g.

3.3. ZnO Dissolution Screening

Isolates were tested for zinc solubilization ability using a modified ZnO medium (Khande et al. 2017) [

29]. The medium included: 10.0 g glucose, 1.0 g ammonium sulfate, 0.2 g potassium chloride, 0.2 g dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, 0.1 g magnesium sulfate, 0.1% insoluble zinc from a ZnO source in 1000 ml distilled water at pH 7.0. From a 24 hour culture of isolates, 100 μl were dropped onto 10 mm petri wells containing the said medium and incubated at 30ºC for 72 hours. Colony diameter and halo areas counted were recorded. The solubility index was calculated using the clear zone diameter/colony diameter formula (Ramesh et al. 2014) [

30].

4. Antimicrobial Activity against Sclerotinia minor

4.1. The Production of Siderophores

CAS (Chrome Asurol S) blue agar was prepared using 60.5 mg CAS dissolved in 50 ml distilled water and mixed with 10 ml iron (III) solution (1 mM FeCl and 10 mM HCI). Under stirring, this solution was slowly added to 72.9 mg HDTMA. (Hexadecyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide) dissolved in 40 ml water. The resultant dark blue liquid was autoclaved for 20 min and also autoclaved a mixture of 750 ml water, 15 g agar, and the pH was adjusted with NaOH to 6.8. The CAS reaction rate was determined by measuring the intensity of color-change in the CAS-blue agar from blue to purple or orange color.

4.2. Dual Culture Assay for the Screening of Biocontrol of Syderophore-Produsing B. mojavensis

Bacterial isolate of

B. mojavensis were tested for

in vitro antagonistic activity against the

S. minor by dual-culture assay as described by Sakthivel and Gnanamanickam (1986) [

31].

B. mojavensis was plated in CAS (Chrome Azurol S) blue agar. A fungal disc (≈9 mm

2) was placed in the centre of a potato dextrose agar (PDA) plate, which contained 0.7% agar. The plates were incubated at 28°C for 7 days. The growth of

S. monor was observed under microscope and compared with the control plate with and without examined

Bacillus mojavenisis strain.

4.3. Isolation of Sclerotinia minor Pathogen and Antimicrobial Activity against Sclerotinia minor

The tested bacterial strains were tested to determine their antifungal activities against

S. minor. The pathogen was cultivated at 28 °C on yeast extract medium (10 g yeast extract, 20 g glucose and peptone, and 20 g agar) for 7 days. Then, the conidia were collected by washing with cold sterile distilled water and used to prepare an inoculum at a concentration of 1x 10

4 spores/ml.

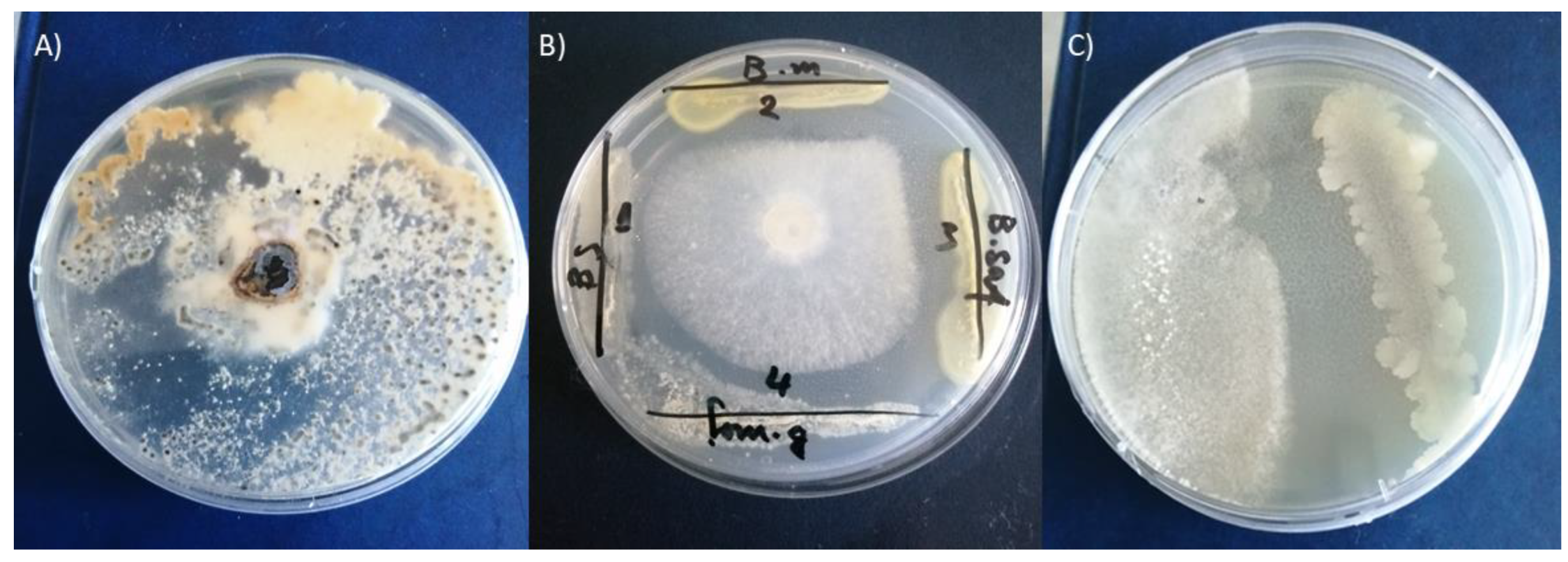

S. minor infected plants were used in the plant pathogenicity tests according to

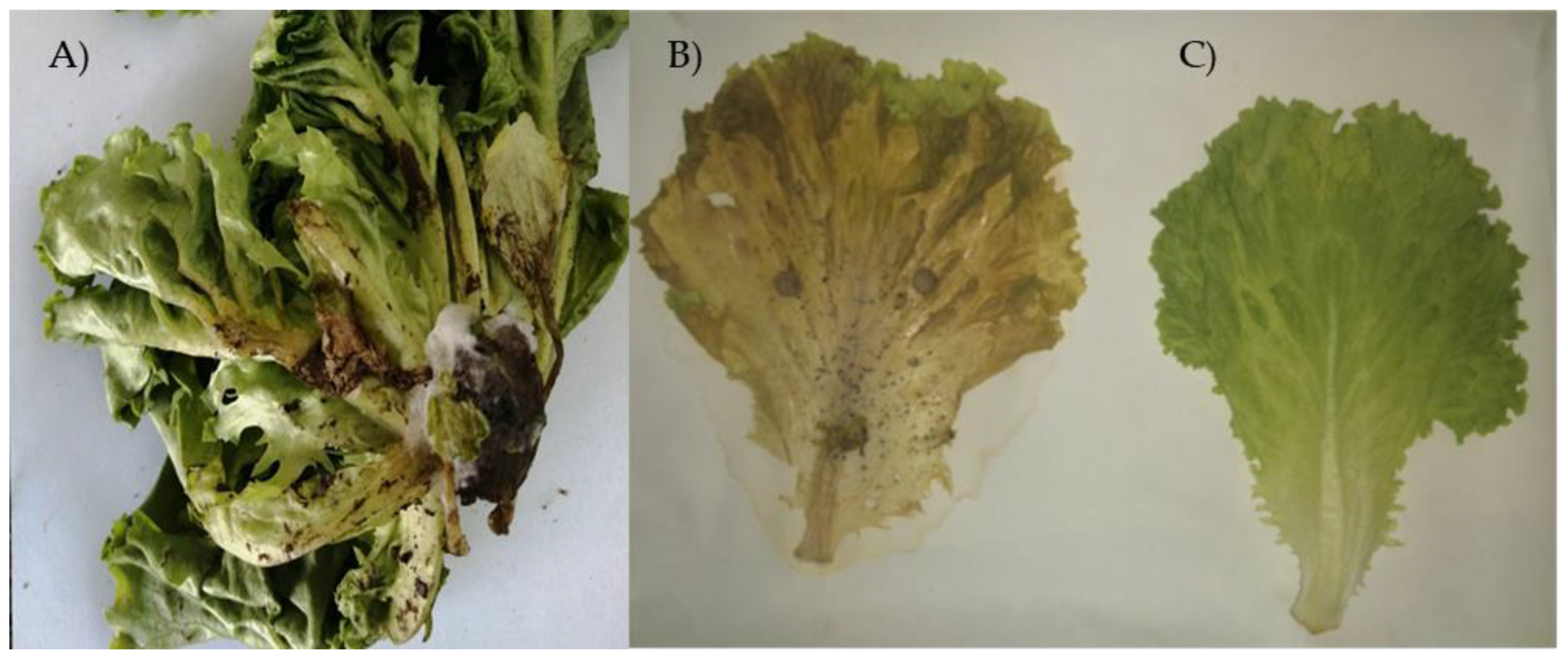

Koch's postulates for the infection of the lettuce leaves is shown in

Figure 1 A. The pathogen was isolated from the damage plants (

Figure 1A) and cultured on yeast extract medium (5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L glucose and 20 g/L agar) at 28 °C for 5 days. Then, the 9 mm dicks were cut used to re-infects the healthy lettuce leaves after surface sterilization (

Figure 1B). After infection, the fungal phytopathogen caused wilting and yellowing of lower leaves on 5–7 days of incubation (

Figure 1 B). White, cottony fungal growth mycelia were observed on the basal plant surfaces and black structures called sclerotia detected within the cottony growth (

Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A)S. minor infected plants B) Inoculation of lettuce leaves after surface sterilization with S. minor dicks and symptoms of the disease C) Displays the state of a control lettuce leaf.

Figure 1.

A)S. minor infected plants B) Inoculation of lettuce leaves after surface sterilization with S. minor dicks and symptoms of the disease C) Displays the state of a control lettuce leaf.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Selection of the Isolated Bacillus Strains According to Their Amylolytic Activity

The main criterion for selecting isolated bacteria is their ability to grow in a medium with starch as the main carbon source. When using solid nutrient media, an indicator of the presence of amylolytic activity is areas of lightning around the colonies assimilating starch, which can be observed after treatment with Lugol's solution (

Table 1). The amylolytic activity occurring on solid culture media is mainly due to cell-bound amylases. The expression of which depends on multiple factors.

The isolates did not show the same amylolytic activity on all media. The reasons are due to different genes involved in the breakdown of carbon sources. As a result of the hydrolysis tests, the tested Bacillus strains were used which showed the ability to digest wheat starch. Bacteria have extracellular amylase enzyme activity can hydrolyze starch (amylose and amylopectin) and they can the degraded starch as result a clear zone around the bacterial colonies appeared. The most active bacteria with amylolytic activity were B. safensis with a reported starch digestion area of 29.263 ± 1.1654b mm. followed by B. subtilis with an area of 22.365 ± 1.983 mm and P. megaterium. 22.166 ± 1.912 mm. The lowest amylolytic activity showed B. mojavensis cell-free supernatant – 15.823 ± 1.028 mm.

Тhe higher amylolytic activity was also observed in the cell-free supernatant of

B. safensis with a reported starch digestion area

of 12.207 ± 0.725 mm, flowed by

P. megaterium 11.052 ± 0.828 mm and

B. subtilis 10.821 ± 0.938 mm zone of activity (

Table 1).

3.2. Study of Proteolytic Activity of Tested Bacillus sp.

The nature and extent of the proteolytic processes are important for preserving good antimicrobial characteristics. The isolates are characterized by the highest proteolytic activity.

Bacillus sp. involve in specific degradation processes became of proteins whose activities are required to fulfil a specific function (e.g. cell cycle. differentiation process. stress response) (Harwood and Kikuchi, 2022) [

33]. Three days after inoculation (on 72

nd hour) the most active bacteria with proteolytic activity remained

B. safensis with a reported starch digestion area on 72 hour of 48.2 ± 0.803 mm of cultured cells and 16.3 ± 0.820 mm of cell-free supernatant. Very good activity demonstrated cultured cells of

B. subtilis and

P. megaterium of 38.6 ± 0.561mm and 40.6 ± 0.324 mm, respectively. The lowest proteolytic activity displayed cells of

B. mojavesis – 28.3±0.193 mm, as well as its cell-free supernatant 10.3 ± 0.563 mm (

Table 2).

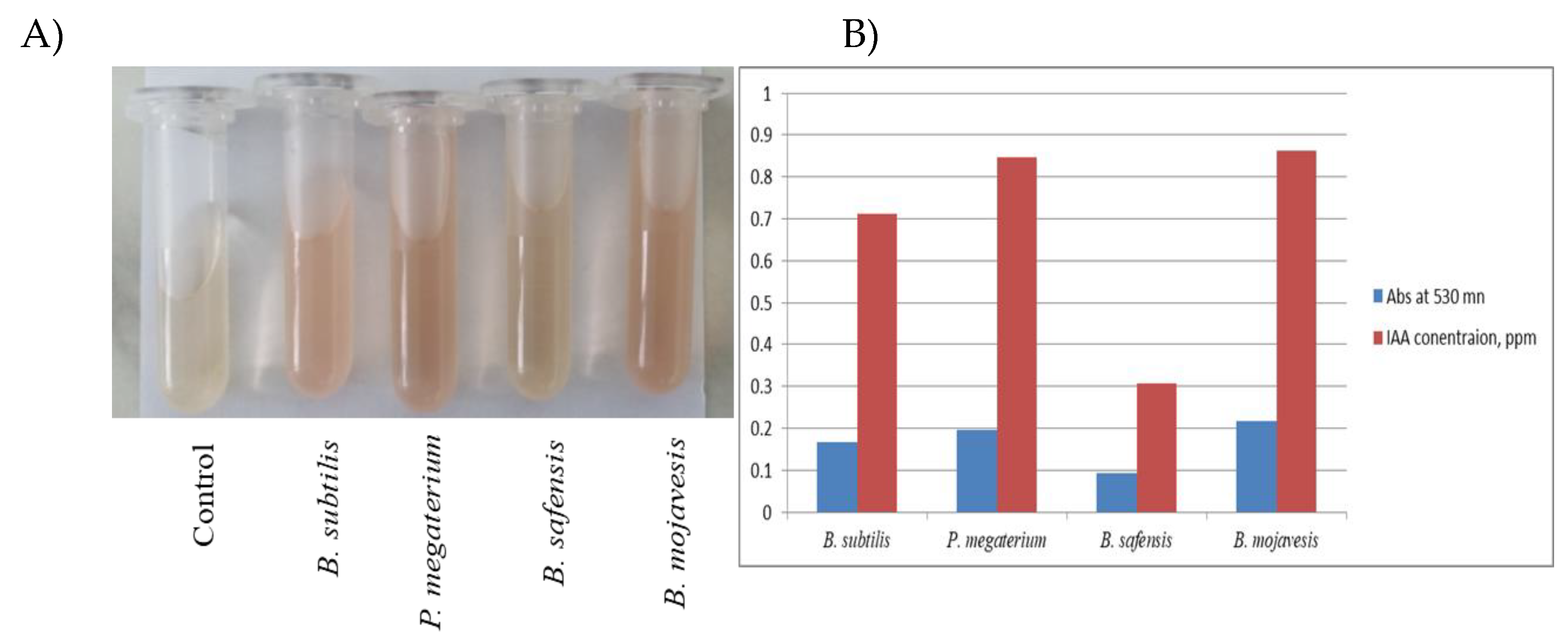

3.3. Quantification of Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA)

The four bacterial strains exhibited weak IAA prodution. The results obtained are shown in

Figure 2. From the results, it can be concluded that the bacteria have a low level of IAA synthesis when there is 0.1% L-trypophan in the medium of 0.712 ppm (µd/ml) in

B. subtilis, 0.848 ppm in

P. megaterium, the highest concetration was measured 0.862 ppm in

B. mojavensis and lowest IAA synthesis in 0.304 ppm in

B. safensis.

The synthesis of microbial phytohormones by bacteria is associated with signalling changes in the root and stimulation of plant growth. The presence of a particular phytohormone in the microbial culture supernatant is not sufficient to prove the functional role of that molecule in its interaction with the plant. A number of studies have observed a correlation between plant growth and hormone concentration measured in the culture medium or in colonized plant tissues in experiments and

in situ (Spaepen. 2015; Spaepen and Vanderleyden, 2011) [

25,

34].

3.4. Screening for Dissolution of Inorganic Phosphate and ZnO

Acid phosphatases and phytases synthesized by rhizosphere microorganisms are involved in the organic solubilization of soil phosphorus (Thaler and Pages, 1998) [

35]. The strains were found to possess high (solubilization zone greater than 2 cm) phosphate-solubilizing activity on PVK medium. The established ability of three of the investigated strains to improve the solubility of inorganic phosphates is an important characteristic of PGP microorganisms. The results of the present study showed that cell free supernatant of

B. subtilis,

P. megaterium, and

B. safensis did not exhibit such activity (

Figure 4). The highest dissolution index was observed in

B. mojavesis cell free culture was 2.670 ± 0.264 cm (

Figure 3 A). The established ability of the investigated strain to improve the solubility of inorganic phosphates is an important characteristic of PGP-microorganisms.

ZnO is insoluble in water and soluble in most of acids (Klingshirn, 2007) [

36]. Carboxylic groups of organic acids can complex metal cations and displace anions to convert insoluble forms of Zn, such as ZnO, into more soluble forms (Chen et al., 2009) [

37]. Several laboratory studies have reported that microbs, which produce siderophores or CO

2, may contribute to environmental Zn solubilization, depending on species of organism and their growth conditions (Kushwaha et al. 2020; Saleem et al., 2023) [

38,

39].

B. mojavesis showed the Zn solubilising activity, while the remaining strains showed no zinc solubilizing ability (

Figure 3 B).

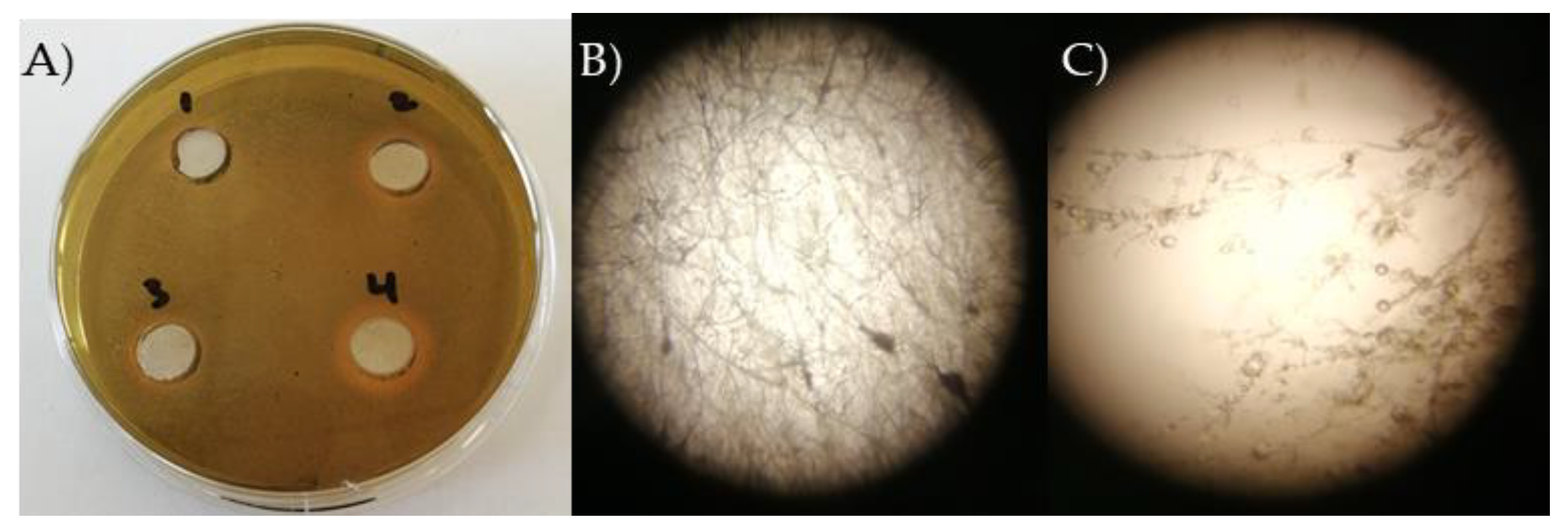

3.5. The Production of Siderophores

A change to yellow was found in

P .megaterum (2), B. safensis (3) and

B. mojavensis (4), with a zone of 0.323 ± 0.078 cm, 0.167 ± 0.032, 0.598 ± 0.233 cm, respectively (

Figure 4 A). Exogenous application on two layers CAS/PDA agar of the bacterial siderophore to fungal cultures resulted in decreased colony size, increased filament length, and changes in hyphal branching pattern (

Figure 4 B and C).

Figure 4.

A) Siderophores production by B. subtilis, P. megaterum, B. safensis, and B. mojavensis strains, expressed as a halo zone on CAS agar plate. B) S. minor filament growth, and С) changes in hyphal branching pattern after treatment with B. mojavensis siderophores on two layers CAS/PDA agar.

Figure 4.

A) Siderophores production by B. subtilis, P. megaterum, B. safensis, and B. mojavensis strains, expressed as a halo zone on CAS agar plate. B) S. minor filament growth, and С) changes in hyphal branching pattern after treatment with B. mojavensis siderophores on two layers CAS/PDA agar.

In the current investigation, the siderophore production was detected the CAS reagent which revealed a change in blue to orange color by

P .megaterum (2),

B. safensis (3) and

B. mojavensis (4). The result is in accordance with the findings of De Los Santos-Villalobos, 2012; Mehri et al. 2012 [

40,

41] that reported different doses of zinc and magnesium also play a major role in the induction of siderophore production by the formation of yellow-green fluorescent pigment around them on nutrient agar medium. Several studies revealed that siderophores are involved in the stimulation of plant growth and also protecting the plants against various biotic stress phytopathegens Ramos-Solano et al., 2010 [

42] including

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary Ribeiro et al. (2021) [

43].

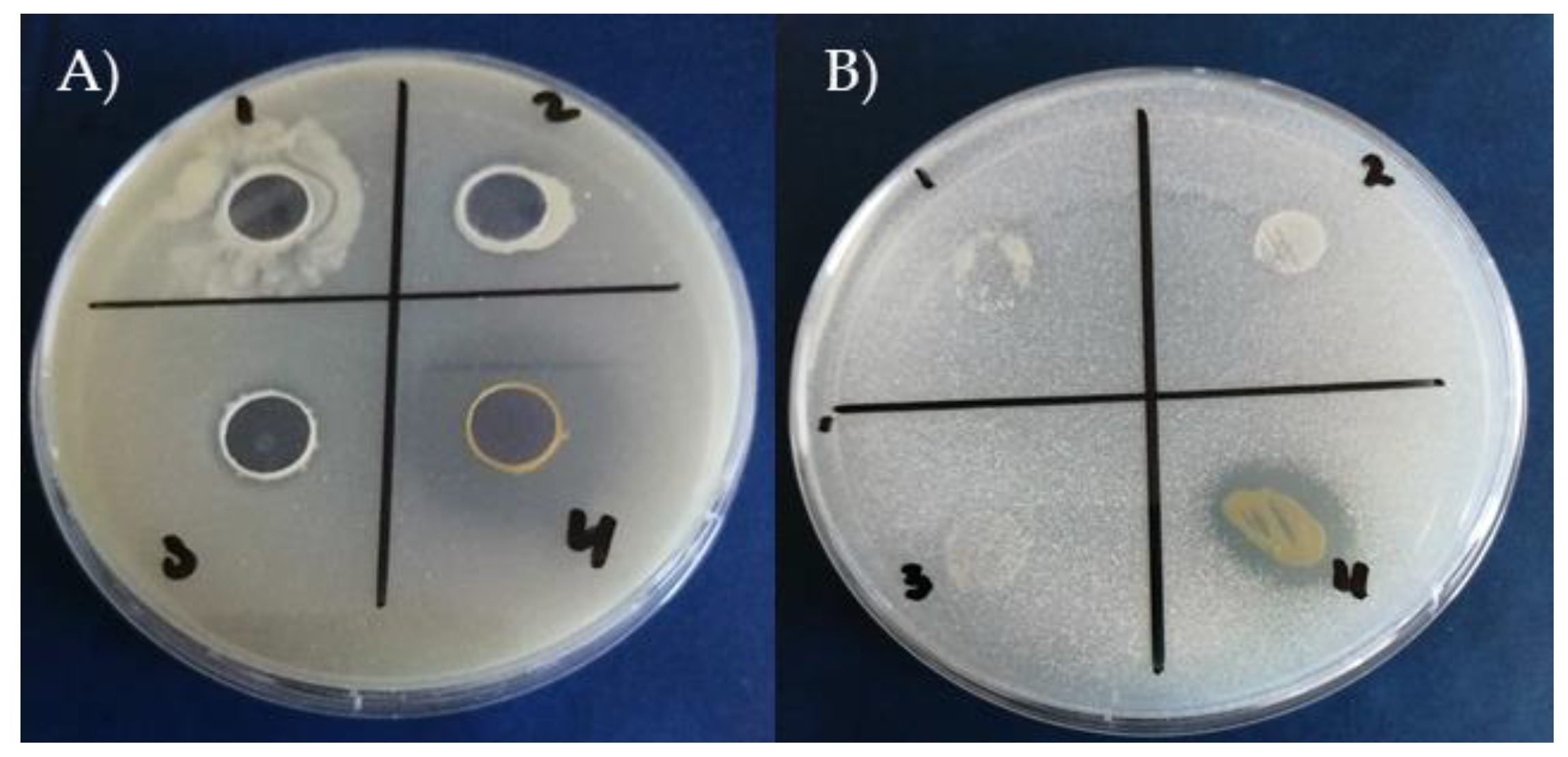

3.7. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of the Tested Bacillus Strains

Many active bacterial strains have been described as biocontrol agents due to their common ability to produce various antifungal metabolites. The antifungal activity of the four tested strains inhibited

S. minor and the calculated inhibition effects are presented in

Figure 5. From the obtained results, all four strains of tested bacteria completely inhibit the growth of

S. minor (

Figure 6).

S. minor produces mycotoxins which are unsuitable for human consumption.

S. minor has become one of the most economically important and studied fungal plant pathogens. Environmental pollution caused by excessive use of chemical pesticides has led to considerable changes in people’s attitudes toward their substation with biological control with antagonistic microorganisms (

Figure 5).

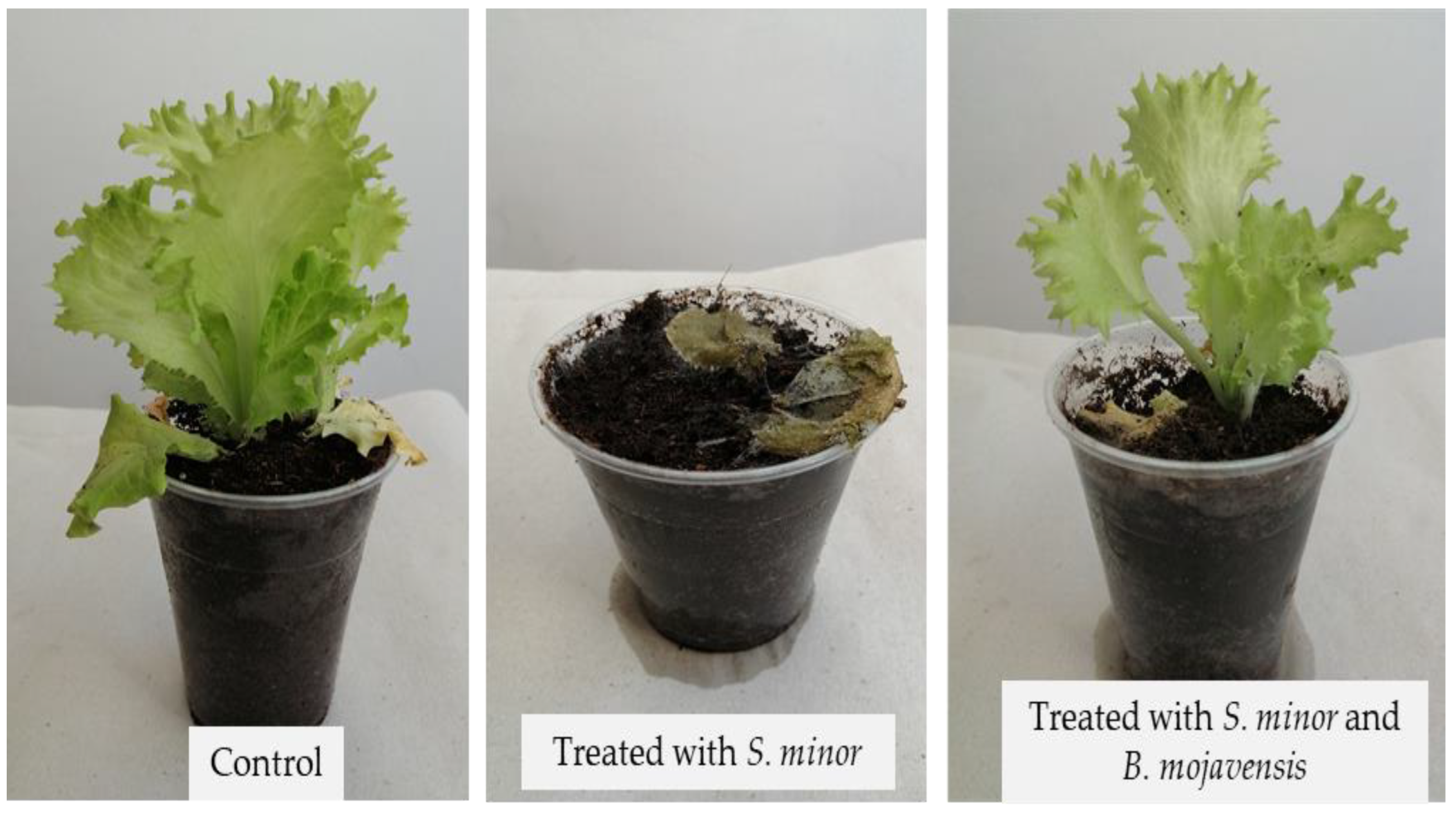

In vivo, the antibacterial efficacy of

B. mojavensis against

S. minor in lettuce showed inhibition on the seventh day after infection (DAI) (

Figure 6). On the seventh DAI symptoms was observed with from the plant tissues without treatment with beneficial bacteria. In the absence of

B. mojavensis, the fungal pathogen caused 100% infection with lesions of the lettuce plants (

Figure 6). In the presence of the

B. mojavensis, a decrease in infection was observed on the seventh DAI (

Figure 6). The results demonstrate a promising potential for the suppression of the

S. minor infection of

Lactuca sativa and expand the knowledge on antimicrobial applications of

Bacillus strains.

In conclusion, Bacillus sp. can promote plant growth and suppress phytopathogens by producing amylolytic, proteolytic enzymes nad siderophores. In the pot trials, when lettuce plants were grown in soils contaminated with S. minor, a 100% pathogen attack was determined when plants were without treatment B. mojavensis CAM23K1. Lettuce treated with bacteria reduces the effect of the pathogen. The antagonistic B. mojavensis CAM23K1 suppressed S. minor disease in the pot experiment and promoted lettuce growth and development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.P. and M.D; methodology, M.P.; M.D. microbiological analysis, M.P. plant experiments; M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; M.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hao, J.J.; Subbarao, K.V.; Duniway, J.M. Germination of Sclerotinia minor and S. sclerotiorum sclerotia under various soil moisture and temperature combinations. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abawi, G.S.; Robinson, R.W.; Cobb, A.C.; Shail, J.W. Reaction of lettuce germ plasm to artificial inoculation with Sclerotinia minor under greenhouse conditions. Plant Disease 1980, 64, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, B.E.; Hayes, R.J.; Truco, M.J.; Puri, K.D.; Michelmore, R.W.; Subbarao, K.V.; Simko, I. The genetics of resistance to lettuce drop (Sclerotinia spp.) in lettuce in a recombinant inbred line population from Reine des Glaces × Eruption. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2019, 132, 2439–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whipps, J.M.; Budge, S.P.; McClement, S.; Pink, D.A. A glasshouse cropping method for screening lettuce lines for resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. European journal of plant pathology 2002, 108, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.E.; Doğramacı, M.; West, M.; Underwood, W.R. Environmental factors for germination of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum sclerotia. Journal of Plant Pathology & Microbiology 2016, 7, 379–383. [Google Scholar]

- Grube, R.; Ryder, E. Identification of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) germplasm with genetic resistance to drop caused by Sclerotinia minor. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2004, 129, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imolehin, E.D.; Grogan, R.G.; Duniway, J.M. Effect of temperature and moisture tension on growth, sclerotial production, germination, and infection by Sclerotinia minor. Phytopathology 1980, 70, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.J.; Subbarao, K.V.; Duniway, J.M. Germination of Sclerotinia minor and S. sclerotiorum sclerotia under various soil moisture and temperature combinations. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.E.; Stewart, A. Biological control of Sclerotinia minor in lettuce using Trichoderma species. In Proceedings of the New Zealand Plant Protection Conference 1997, Vol. 50; pp. 154–158.

- Del Rio, L.E.; Martinson, C.A.; Yang, X.B. Biological control of Sclerotinia stem rot of soybean with Sporidesmium sclerotivorum. Plant Disease 2002, 86, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, L.M.; Domingues, M.V.P.; Moura, K.E.D.; Harakava, R.; Patricio, F.R.A. Selection of Trichoderma isolates for biological control of Sclerotinia minor and S. sclerotiorum in lettuce. Summa Phytopathologica 2016, 42, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larena, I.; Melgarejo, P. Biological Control of Monilinia laxa and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici by a Lytic Enzyme-Producing Penicillium purpurogenum. Biological control 1996, 6, 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Crosa, J. H, Walsh C. T. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. R. 2002, 66, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gram, L. The influence of substrate on siderophore production by fish spoilage bacteria. J. Microbiol. Meth. 1996, 25, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyohara, H.; Nagao, K.; Yana, K. Rapid screen for bacteria degrading water-insoluble, solid hydrocarbons on agar plates. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1982, 43, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.P. , Xu, J. G., Song, P, Song, J. N, Chen, W.L. Isolation and identification of a potential biocontrol agent Bacillus subtilis QM3 from Qinghai yak dung in China. World. J. Microb. Biot. 2008, 24, 2451–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, W.D.; Nakkeeran, S.; Zhang, Y. 13 Ecofriendly methods in combating Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary, 2004.

- Saharan, G.S.; Mehta, N. Sclerotinia Diseases of Crop Plants: Biology, Ecology and Disease Management. Springer, Dordrecht, 2008.

- Sabaté, D.C.; Brandan, C.P.; Petroselli, G.; Erra-Balsells, R.; Audisio, M.C. Biocontrol of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary on common bean by native lipopeptide-producer Bacillus strains. Microbiological research 2018, 211, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, F.; Castro, M.; Príncipe, A.; Borioli, G.; Fischer, S.; Mori, G.; Jofré, E. The plant-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strains MEP218 and ARP23 capable of producing the cyclic lipopeptides iturin or surfactin and fengycin are effective in biocontrol of sclerotinia stem rot disease. Journal of applied microbiology 2012, 112, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, I.D. A.; Bach, E.; da Silva Moreira, F.; Müller, A.R.; Rangel, C.P.; Wilhelm, C.M.; Passaglia, L.M. P. Antifungal potential against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary and plant growth promoting abilities of Bacillus isolates from canola (Brassica napus L.) roots. Microbiological Research 2021, 248, 126754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agati, V.; et al. "Isolation and characterization of new amylolytic strains of Lactobacillus fermentum from fermented maize doughs (mawe and ogi) from Benin. " Journal of Applied Microbiology 1998, 85, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabrdalik, Małgorzata, Katarzyna Grata, and Adam Latała. Proteolytic activity of Bacillus cereus strains. Proceedings of ECOpole 2010, 4.

- Petkova, M.; Stefanova, P.; Gotcheva, V.; Kuzmanova, I.; Angelov, A. Microbiological and physicochemical characterization of traditional Bulgarian sourdoughs and screening of lactic acid bacteria for amylolytic activity. Journal of Chemical Technology & Metallurgy 2020, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Spaepen, S. Plant hormones produced by microbes. In Principles of plant-microbe interactions: microbes for sustainable agriculture; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; pp. 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Petkova, M.; Gotcheva, V.; Dimova, M.; Bartkiene, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Angelov, A. Screening of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains from Sourdoughs for Biosuppression of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae and Botrytis cinerea in Table Grapes. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.A.; Weber, R.P. Colorimetric estimation of indoleacetic acid. Plant physiology, 1951, 26, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, V.S. Bacillus subtilis: A potential salt tolerant phosphate solubilizing bacterial agent. International Journal of Life Sciences Biotechnology and Pharma Research 2014, 3, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Khande, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Ramesh, A.; Sharma, M.P. Zinc solubilizing Bacillus strains that modulate growth, yield and zinc biofortification of soybean and wheat. Rhizosphere 2017, 4, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Sharma, M.P.; Yadav, N.; Joshi, O.P. Inoculation of zinc solubilizing Bacillus aryabhattai strains for improved growth, mobilization and biofortification of zinc in soybean and wheat cultivated in Vertisols of central India. Applied Soil Ecology 2014, 73, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, N.; Gnanamanickam, S.S. Toxicity of Pseudomonas fluorescens towards rice sheath-rot pathogen Acrocylindrium oryzae Saw. Current Science, India 1986, 55, 106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, R.; McSpadden Gardener, B.B. Identification and characterization of novel genetic markers associated with biological control activities in Bacillus subtilis. Phytopathology, 2006, 96, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, C.R.; Kikuchi, Y. The ins and outs of Bacillus proteases: activities, functions and commercial significance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2022, 46, fuab046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaepen, S.; Vanderleyden, J. Auxin and plant-microbe interactions. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2011, 3, a001438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, P. and Pages, L. Modelling the influence of assimilate availability on root growth and architecture. Plant and soil 1998, 201, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingshirn, C. ZnO: From basics towards applications. physica status solidi (b) 2007, 244, 3027–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Dahlgren, R.A. Heavy metal sources identification and sampling uncertainty analysis in a field-scale vegetable soil of Hangzhou, China. Environmental pollution 2009, 157, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, P.; Kashyap, P.L.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Kuppusamy, P.; Srivastava, A.K.; Tiwari, R.K. Bacterial endophyte mediated plant tolerance to salinity: growth responses and mechanisms of action. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 36, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Malik, A.; Khan, S.T. Prospects of ZnO-nanoparticles for Zn biofortification of Triticum aestivum in a zinc-solubilizing bacteria environment. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2023, 23, 4350–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Santos-Villalobos, S. Burkholderia cepacia XXVI siderophore with biocontrol capacity against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehri, I.; Khessairi, A.; Yousra, T.; Neila, S.; Imen, D.; Marie, M.J.; Abdennasseur, H. Effect of dose response of zinc and manganese on siderophores induction. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 8, 143–15163. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Solano, B.; García, J.A.L.; Garcia-Villaraco, A.; Algar, E.; Garcia-Cristobal, J.; Mañero, F.J. G. Siderophore and chitinase producing isolates from the rhizosphere of Nicotiana glauca Graham enhance growth and induce systemic resistance in Solanum lycopersicum L. Plant Soil. 2010, 334, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.D. A.; Bach, E.; da Silva Moreira, F.; Müller, A.R.; Rangel, C.P.; Wilhelm, C.M.; Passaglia, L.M. P. Antifungal potential against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary and plant growth promoting abilities of Bacillus isolates from canola (Brassica napus L.) roots. Microbiological Research 2021, 248, 126754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).