Submitted:

10 August 2024

Posted:

13 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Wheel factors: Geometry (diameter, conicity, tread width, contact angle), machining (roughness), material (properties), load and previous wear.

- Wagon factors: Configuration (bogies or axles distribution and type of bogies), type of suspension, braking system, running speed and load distribution (axle load).

- Railway superstructure factors: Track gauge, line layout (curve radii, windiness, sagitta, gradient, etc.), layout quality (excess or deficiency in cant, transition curves, etc.), type of rail (welded or with joints), track materials (properties) and track previous degradation (previous rail wear, specially).

- External factors: Temperature, humidity, wind, rain, snow and weather in general. The presence of moisture, leaves and pollutants (saltpeter, oil, etc.) is in here too.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. List of Abbreviations

2.2. Hypthoteses

- (a)

- The procedure is based on global calculations for the contact patch, without discretizing it into finite elements.

- (b)

- It is stationary, that is, it does not consider the variation of variables over the time. At transition curves, where these variations are greater, mean values are computed.

- (c)

- It disregards any rail wear and it does not consider the previous wheel wear either (it does not update the contact parameters as the profile wears out, but this profile is assiduously renovated).

- (d)

- It is applied on all of the bogie wheels. For each wheel, the parameters and wear calculations are separately saved. This is because the wear is not the same for all of the wheels mounted on the same bogie (Rovira, 2012).

- (e)

- It is applied on one bogie belonging to a wagon. A wagon normally consists of two bogies, but they can mostly rotate independently with respect to the other.

- (f)

- It disregards the tractive and compressive forces that some wagons transmit to the next ones through couplings when curving, which is due to the existing coupling slacks (Moody, 2014).

- (g)

- It can consider up to 2 contact patches at the same wheel: one of them on the tread and the other on the flange. The load percentage of each patch will be controlled by means of a parameter (Pellicer & Larrodé, 2021).

- (h)

- In Kalker’s and Polach’s equations, the spin is assumed to be positive when it is clockwise, as it must comply with the sign convention applied for creepage. This spin is later passed on to the energy transfer model employed.

- (i)

- Creepage is obtained from a kinematic analysis of the wheelsets rather than from the non-dimensional slips (these include partial derivatives which are usually not applied to global calculations).

- (j)

- In the whole study, the radial deformation is disregarded with respect to the wheel radius (this is a usual hypothesis in these studies because ).

- (k)

- As (in fact, , judging by the values obtained in (Pellicer & Larrodé, 2021)), the effect of on can be disregarded as well.

- (l)

- In contrast, the effect of on the wear happening at transition curves is not considered, given that it increases the wear slightly.

- (m)

- In this kinematic analysis, the displacements from bogie suspensions and anti-yaw are not included.

- (n)

- The variation of the wheel and rail curvatures at transition curves is discarded, given that, although the location of the rail-wheel contact varies along the wheel and rail widths (and their curvatures as a consequence), these variations are usually very small. When these variations are great, the most unfavorable values are directly taken (for instance, the curvatures of flange-rail contact when this contact is predicted to appear at a certain transition curve).

- (o)

- Only abrasive and adhesive wear are considered, without considering defects such as cracks, spalling, squats, flats, etc. (Ortega, 2012), (RENFE, 2020).

- (p)

- RCF is only predicted, without computing the extent of the damage produced, often sub-surface cracks (Ortega, 2012).

- (q)

- The bogie wheels are considered to be non-powered, so at the wheel-rail interfaces.

- (r)

- The bogie wheels are considered to be equipped with disk brakes, which do not wear the wheels out (Pellicer & Larrodé, 2021).

- (s)

- The railway vehicle is presumed to negotiate curves (circular or transition ones) at a constant speed, so it brakes (if necessary) before negotiating them, so at a curve. There is an exception when the vehicle is running downhill, as explained in the next hypothesis.

- (t)

- The railway vehicle is assumed to brake slightly when running downhill and reducing or cutting off traction is not enough to keep a constant speed at curves: when the slope is less than 10 ‰, the vehicle brakes will be off, when the slope is between 10 and 15 ‰, the brakes will brake 5 % of the accelerating force at each wheelset, and when the slope is greater than 15 ‰, the brakes will brake 10 % of the accelerating force.

- (u)

- The infrastructure parameters that modify the wear conditions, such as warp, rail deflection, joints, impacts against switch frogs and track devices and track irregularities are not considered (Larrodé, 2007).

- (v)

- The influence of manufacturing or assembly tolerances of any element is not considered.

- (w)

- By not considering rail deflection or manufacturing and assembly tolerances, it is possible to assume that the longitudinal rail curve radius () tends to infinity, so that the associated curvature () tends to zero and can be taken as such.

- (x)

- The bogie wheels are assumed not to derail or block (this was numerically verified in (Pellicer & Larrodé, 2021)). Also, and they are assumed not to displace laterally under cant deficiency or excess and low static friction conditions (Pellicer & Larrodé, 2021).

- (y)

- There is not any hunting oscillation at the speed ranges considered (this was numerically proven in (Pellicer & Larrodé, 2021)).

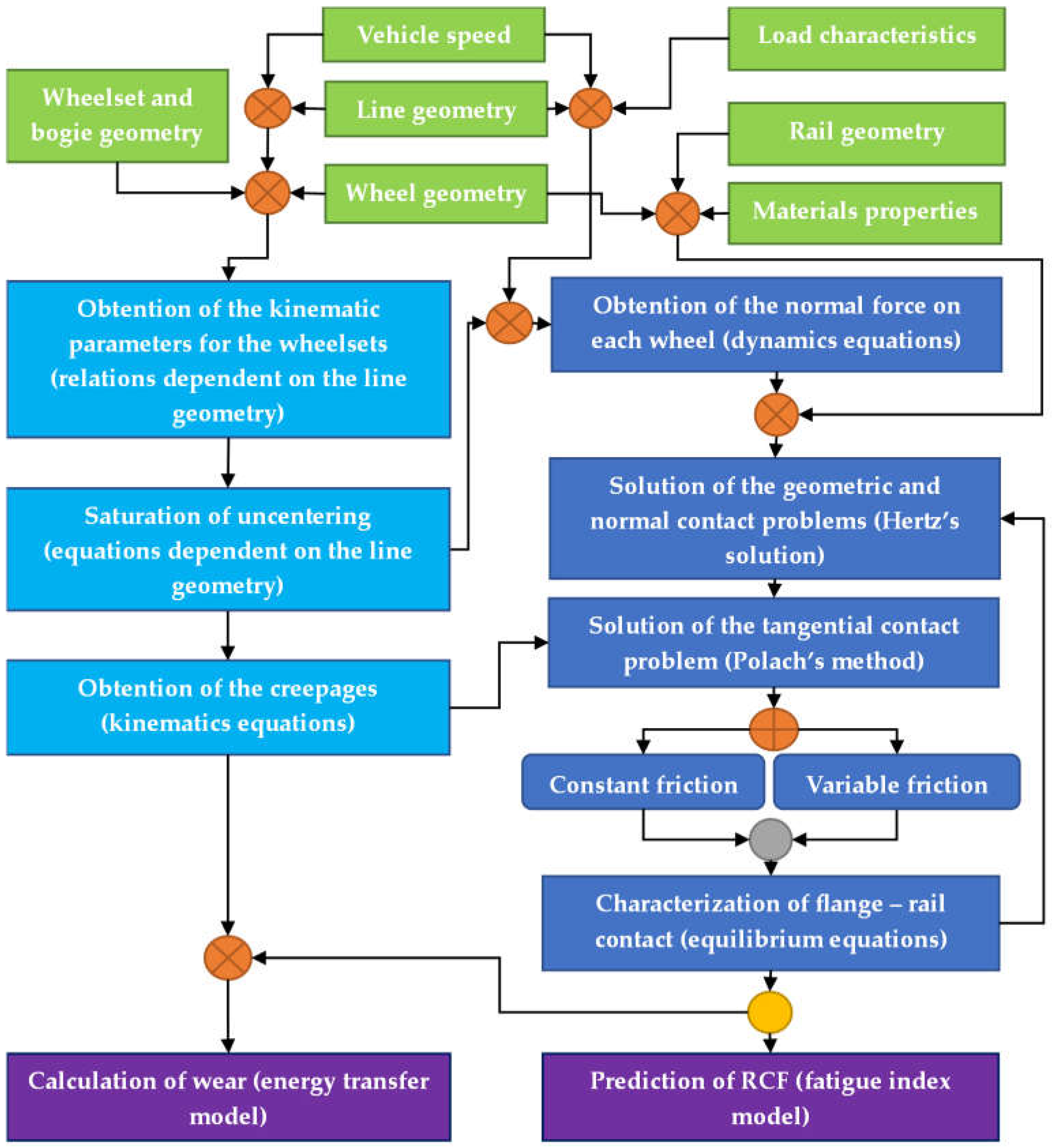

2.3. Calculation Process

- At the top of the algorithm, the input data is entered to the calculation blocks. The data is arranged in blocks that are added before going down to the main branches. These blocks gather information on the wheelset and bogie geometry, vehicle speed, railway line geometry, wheel geometry, load characteristics, rail geometry and contact materials properties.

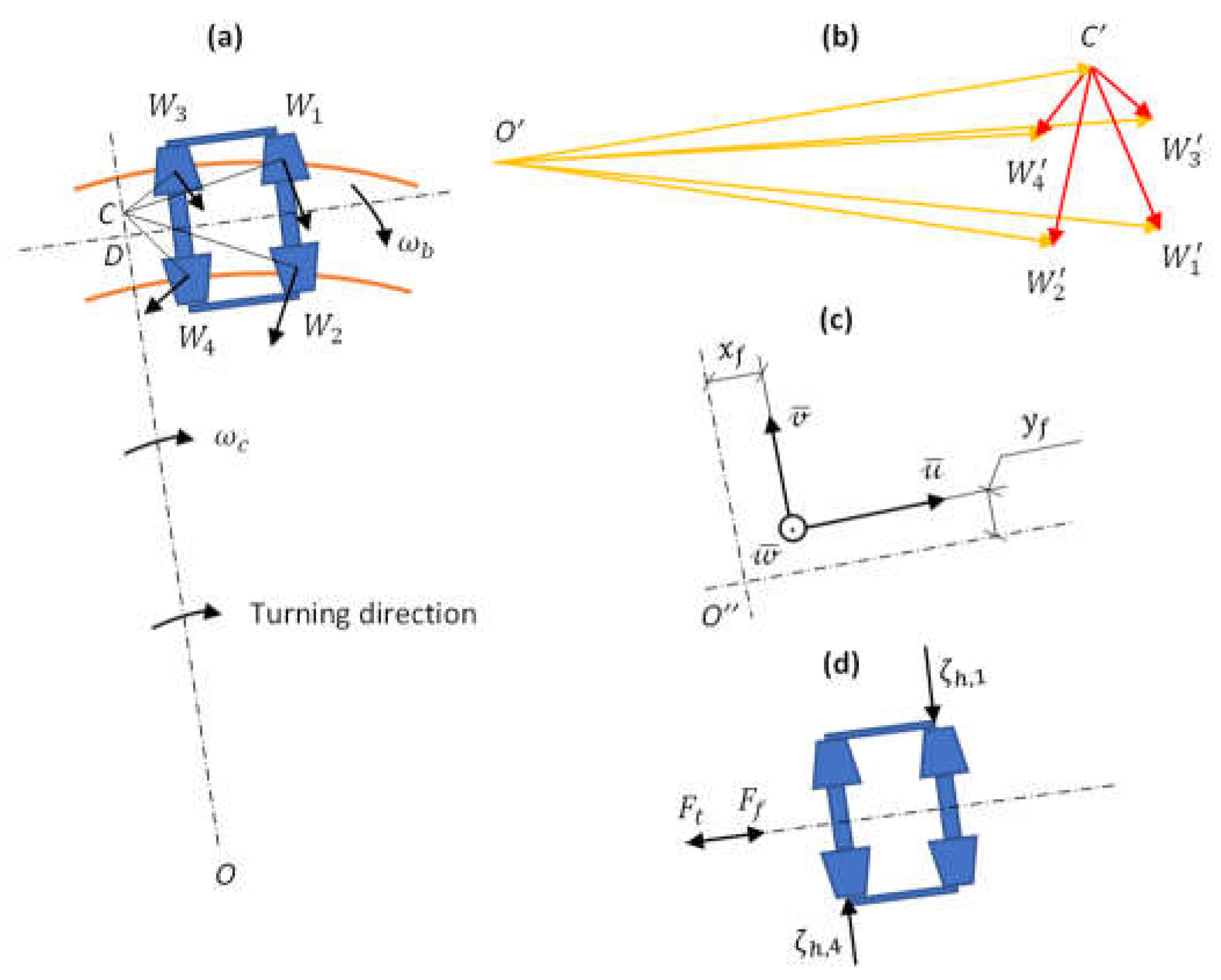

- On the left, in the 3 central blocks, the kinematic parameters for the wheelsets are obtained through relations dependent on the line geometry after inputting information on the wheelset and bogie geometry, vehicle speed, railway line geometry and wheel geometry. After that, the uncentering of each wheelset is saturated through equations dependent on the line geometry and, finally, creepages are obtained through kinematics equations.

- On the right, in the 6 central blocks, the normal force on each wheel is computed by means of dynamics equations after entering data on the vehicle speed, line geometry, load characteristics and some results coming from the left main branch after the saturation of uncentering. Afterwards, the geometric and normal contact problems are solved by means of Hertz’s solution, for which data on the wheel and rail geometries and the contact materials properties is needed. The results of Hertz’s solution and the creepages computed in the left main branch allow applying Polach’s method. This solution can be applied either with constant or variable friction. At the end of this branch, the flange – rail contact is characterized by means of equilibrium equations.

- At the bottom of the algorithm, the wheel wear is computed through the energy transfer model and the appearing of RCF is predicted with the fatigue index model.

2.4. Calculation Model

2.4.1. Reference Frames Definition

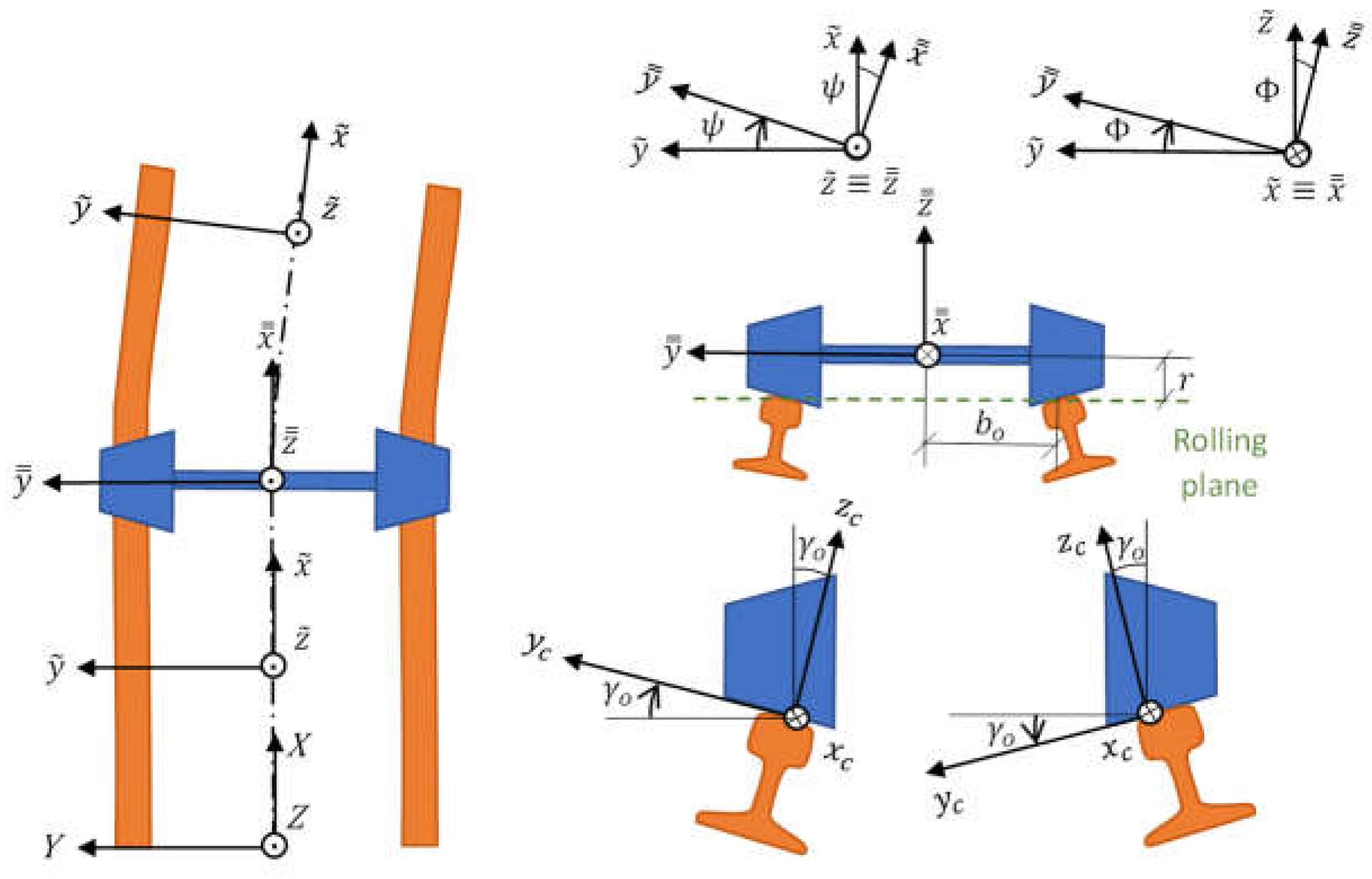

- Absolute reference frame , clockwise, fixed and whose origin set on the rolling plane, anchored to the track beginning and centered between the rails.

- Track reference frame , clockwise, mobile at the vehicle speed and whose origin is set on the rolling plane and along the track middle line, holding the axis always tangent to that line.

- Axle reference frame , clockwise, mobile at the axle speed and whose origin is set at the gravity center of the wheelset.

- Contact area reference frame , clockwise, mobile at the contact area speed and whose origin is set on the center of the area.

2.4.2. Obtention of the Kinematic Parameters

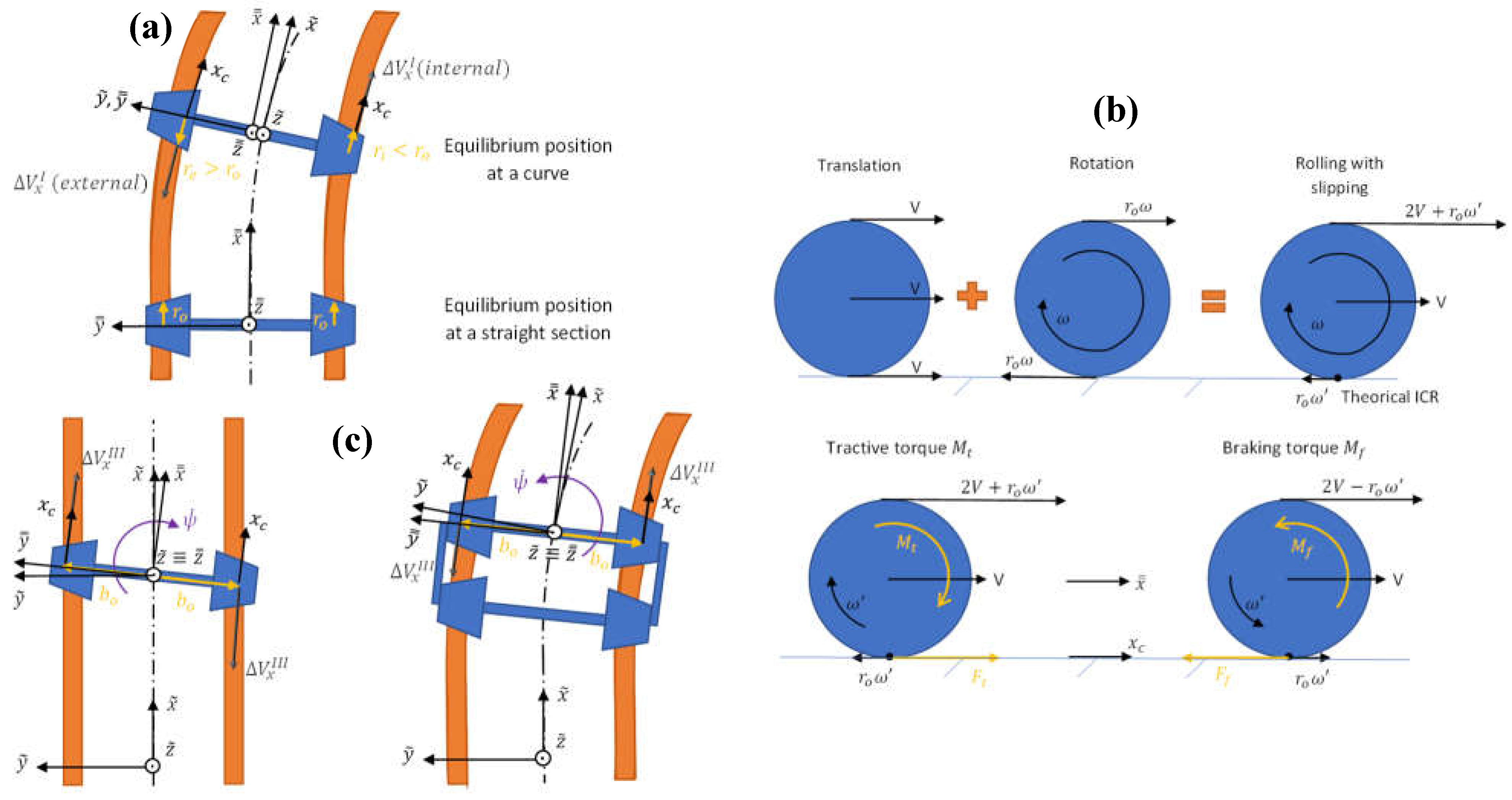

- Straight section.

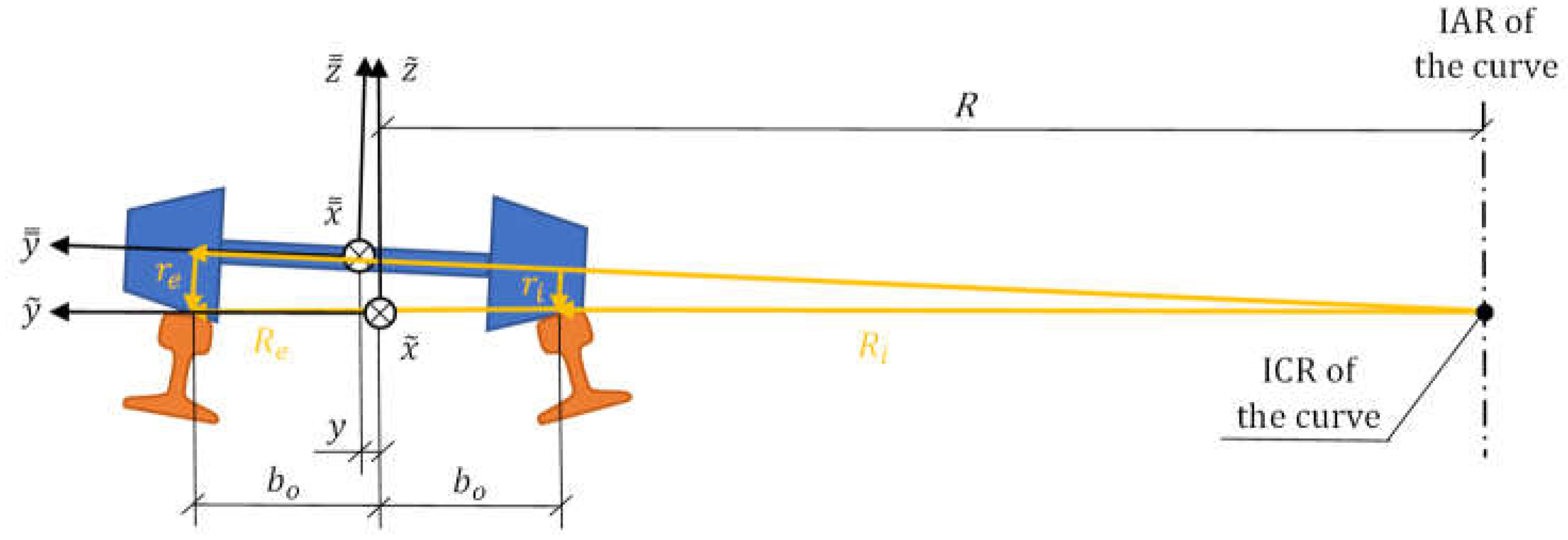

- Circular curve.

- Transition curve: Clothoid, quadratic parabola or cubic parabola.

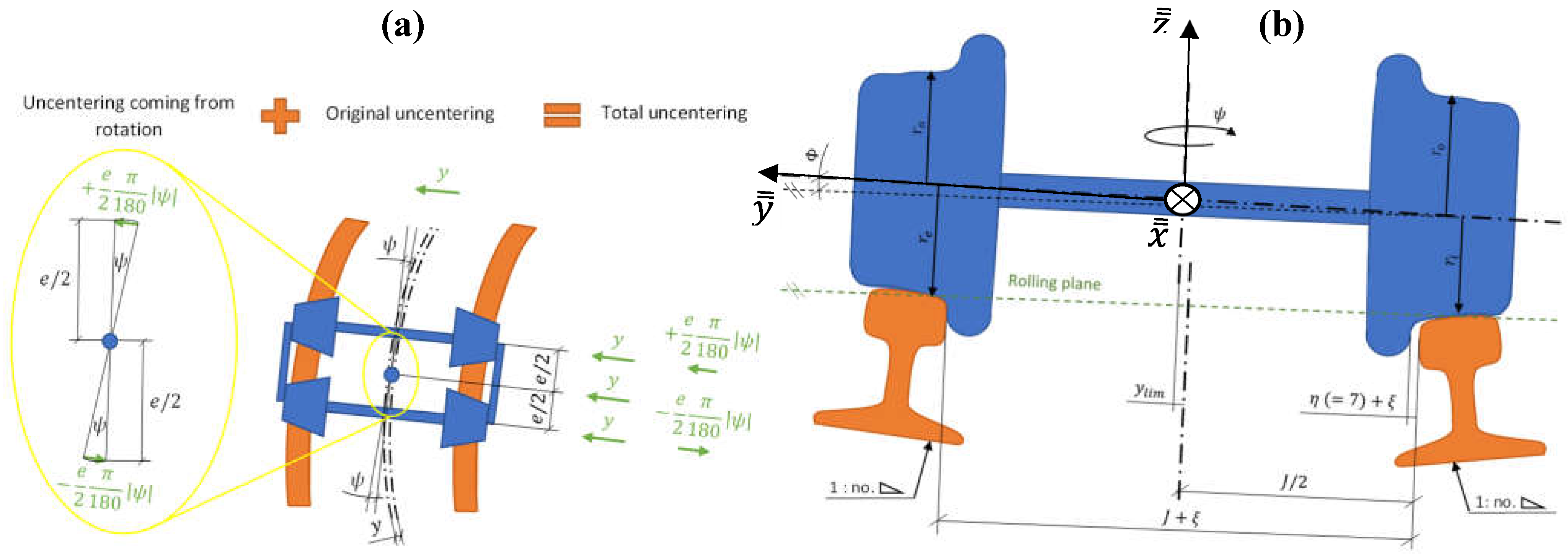

- Uncentering and uncentering speed.

- Average uncentering and uncentering speed.

- Yaw angle and yaw angle variation speed / rate.

- Average sinus of yaw angle and of yaw angle variation.

- Average yaw angle.

- Combination of the uncentering and yaw angle effects.

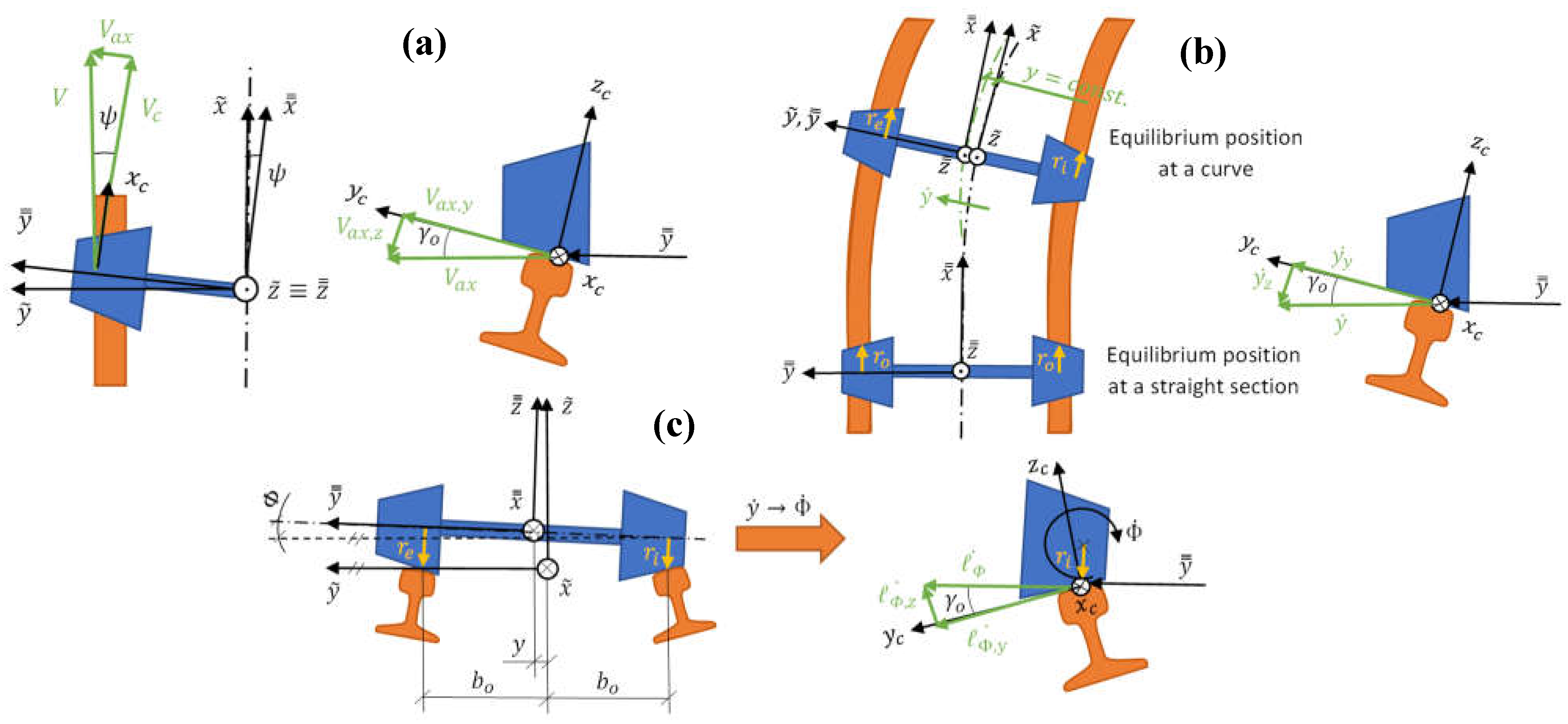

- Angle of longitudinal displacement of the contact area.

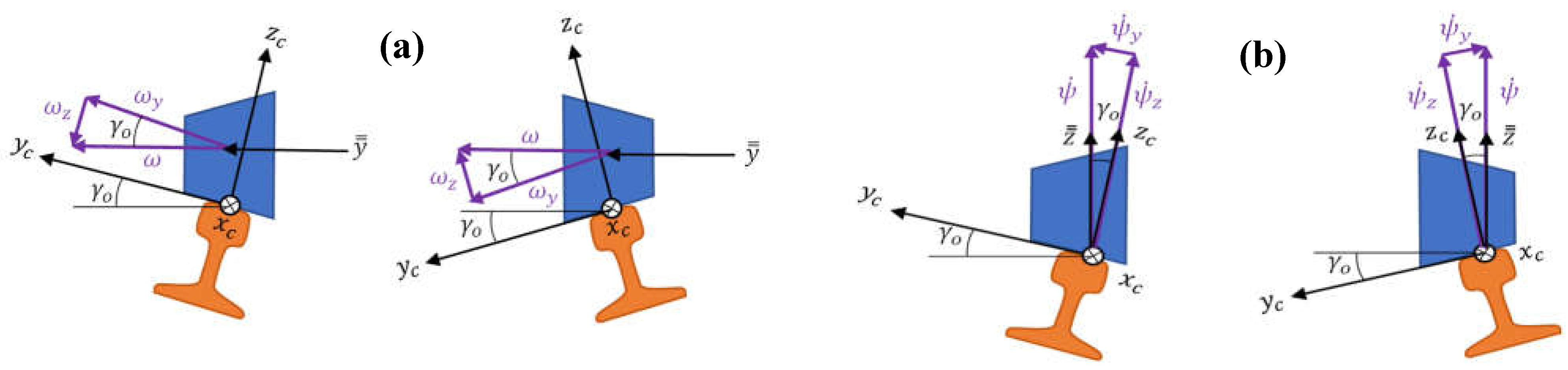

- Tilt and tilt speed / rate.

2.4.3. Saturation of Uncentering

- SC – Rolling radius ().

- SC – Track gauge (for Iberian gauge).

- SC – Rail inclination ( for Iberian gauge).

- SC – Track play / slack (.

- C – Curve radius ().

- C – Gauge widening ().

- C – Curve sagitta ().

- C – Total uncentering () and uncentering limit ( or ).

- C – Outer | inner wheel rolling radius ().

- C – Yaw () and tilt angles ().

- C – Angle of longitudinal displacement of the contact area ().

2.4.4. Obtention of the Creepages

- Difference between the nominal wheel radius and the real rolling one (generating ).

- Application of tractive or braking torques to the wheel (generating ).

- Variation of yaw angle (generating ).

- Not null yaw angle (generating ).

- Adoption of a new equilibrium position by the wheelset (generating ).

- Not null tilt angle (generating ).

- Conicity (generating , alternatively known as the camber effect (Ortega, 2012)).

- Variation of yaw angle (generating ).

2.4.5. Obtention of the Normal Force on Each Wheel

- Axle load (), which obtained from the payload, tare and number of axles.

- Center of gravity of the axle load (), considering the contribution of each load.

- Gradient angle (), which is directly inferred from the inclination ().

- Cant angle (), which depends on the cant and the distance between contact areas.

- Lateral acceleration (), which considers the effect of cant excess or deficiency.

- Wheel contact angle () and longitudinal displacement angle of the contact patch ().

2.4.6. Solution of the Geometric and Normal Contact Problems

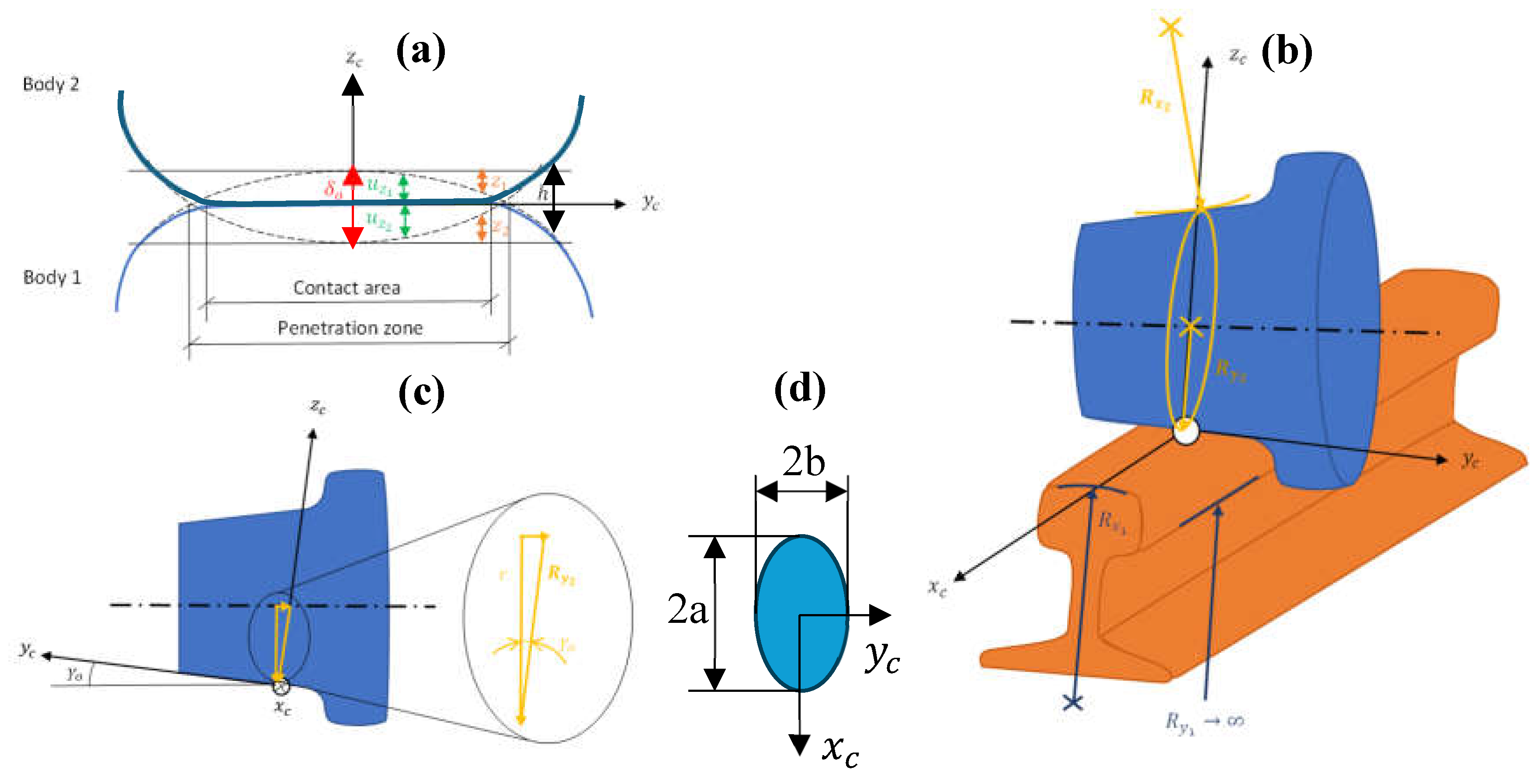

- Hertzian contact theory: This theory was the first satisfactory analysis for the stresses appearing at the contact zone between 2 elastic solid bodies and solves the geometric problem at the same time if a series of hypotheses are fulfilled. According to this theory, the contact area is the intersection of two perfect paraboloids: a perfect ellipse.

- Kik – Piotrowski theory: This is a quasi-Hertzian theory and is also based on the virtual interpenetration between surfaces. It assumes the same pressure distribution in the longitudinal direction as Hertz, but not in the lateral direction as the curvature is not always constant in that direction. It is interesting to point out that this theory disregards the real shape of the bodies and replaces them by elastic half-spaces, which allows employing Boussinesq’s influence functions.

- Ayasse – Chollet: This is also a quasi-Hertzian theory, a variant of the previous one.

- Stiff approach: This theory is based on a stiff contact in which there is a theoretical contact point for which a series of constraints are imposed.

- The bodies in contact are homogeneous, isotropic and linear elastic.

- Displacements are supposed to be infinitesimal (much smaller than the bodies’ characteristic dimensions).

- The bodies are smooth at the contact zone, that is, without any roughness.

- Each body can be modeled as an elastic half-space, which requires a non-conformal contact.

- The bodies’ surfaces can be approximated by quadratic functions in the vicinity of the maximum interpenetration point. This implies that the curvatures (the second derivates of the functions) are constant.

- The distance between the undeformed profiles of both bodies at the maximum interpenetration point can be approximated by a paraboloid.

- The contact between the bodies is made without friction, so only normal pressure can be transmitted.

2.4.7. Solution of the Tangential Contact Problem

- Analytical: The values are globally computed for the whole contact patch. A set of analytical equations are used, and the tangential problem can be decoupled from the geometric and normal ones because non-conformity and quasi-identity are satisfied.

- Finite-element: The values of the variables are locally computed and are added thereafter so as to obtain the global values. For that, the contact patch is meshed.

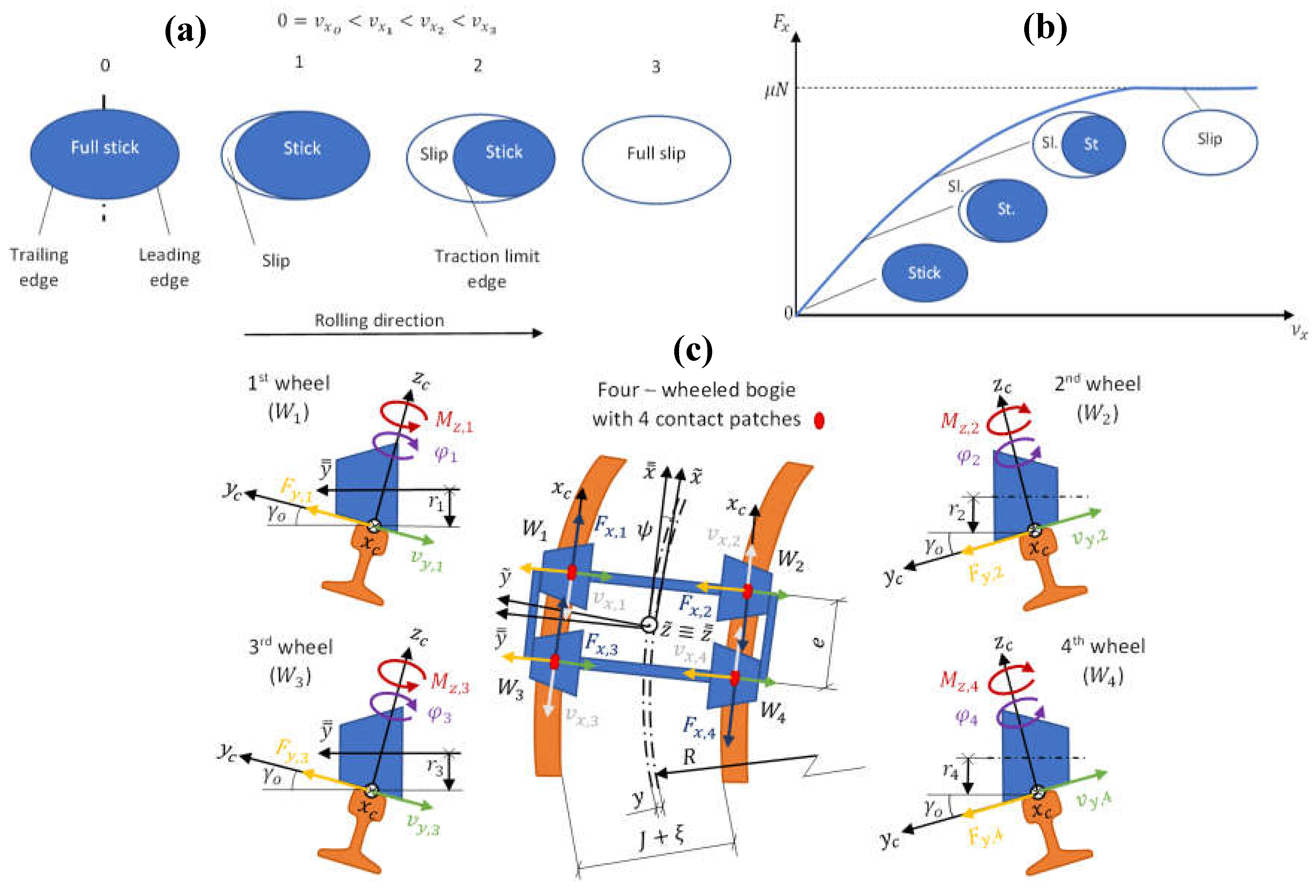

- Carter’s theory: This was the first theory ever. Carter coined the term “creepage” as “the ratio of the distance gained by a surface with respect to the other divided by the distance run“. He stated that the longitudinal dimension of Hertz’s ellipse in the unworn profiles was, in general, greater than the lateral one, but, as a consequence of wear, profiles flattened, giving rise to a uniform-width strip. He assumed that the wheel and rail profiles could be approximated by two parallel-axis cylinders, so the problem was reduced to a plane stress problem, that is, bi-dimensional.

- Johnson’s theory: Johnson published the first contact theory for circular contacts. In this theory, the stick region is circle-shaped and it touches the leading edge at a single point, although he later showed that this hypothesis leads to a contradiction: tangential stress does not oppose slip at the slip region adjacent to the leading edge. He also derived relations between creepages that were decreasingly small and tangential forces. Finally, he showed that the spin effect also contributes to lateral force.

- Johnson – Vermeulen’s theory: Johnson worked later with Vermeulen and both extended the theory of circular contacts under pure creepage (no spin) conditions to cases of elliptical contact. They used the solution for slipping contacts with microslip derived by Deresiewick for elliptical contact, with the only difference being that the stick region touches the leading edge at a single point with the purpose of reducing the erroneous area for a rolling contact case. However, in this theory there was still a region where the friction law was not fulfilled.

- Kalker’s theory: At first, Kalker established a linear relation between the tangential forces and decreasingly – small creepages. At such a restrictive situation, it is possible to assume that the whole contact area is in adhesion (there is no slip region). This first linear theory was also known as “non-slip theory” in which the friction law and the friction coefficient were discarded. Due to the lack of saturation of this theory (Coulomb – Amonton’s law would be the only saturation), this theory was improved with linear and cubic saturation approaches (CONTACT and SHE methods, respectively).

- Polach’s theory: Even with the improvements, Kalker’s theory was not enough for computing the lateral tangential force accurately when the spin grows beyond a certain threshold. Polach proposed a method to tackle this problem: (1) Tangential forces computation considering null spin. (2) Tangential forces computation considering pure spin. (3) Addition of the forces computed in steps (1) and (2) and saturation according to the traction limit. For this method, Polach assumed that the ellipse semi-axis in the rolling direction () tends to zero, so the position of the spin center tends to the ellipse center. He extended this assumption to higher semi-axes ratios ().

2.4.8. Characterization of Flange – Rail Contact

2.4.9. Calculation of Wear

- The equations are parametrized for abrasive wear and not for adhesive wear because: (1) Plastic deformation appears, but it is difficult to model without finite-element methods, which come with a high computing cost. (2) It is reasonable to assume that the major contribution is abrasive wear. (3) When the mathematical tools are calibrated with experimental data, both phenomena are already included in the resulting wear law.

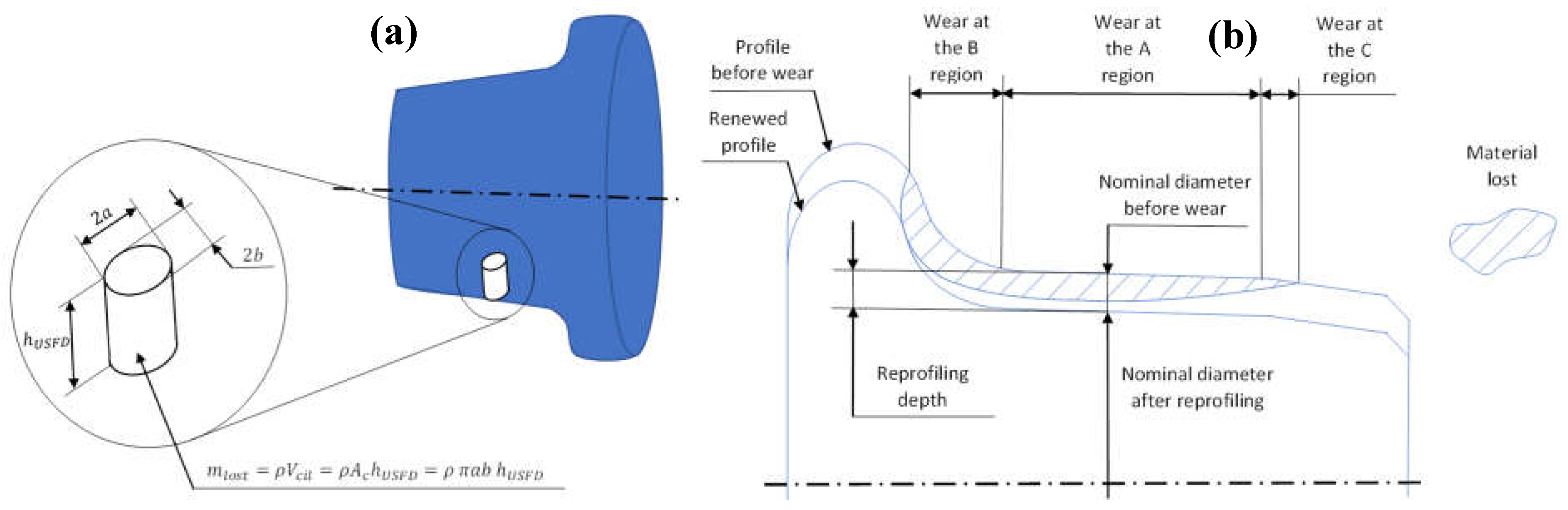

- The different mathematical tools study the wear on the wheel profile, where the wear estimated at every instant is cumulative.

- Wear is assumed to be regular: the variation of the transversal profile is studied, not pattern formation along the longitudinal (circumferential) direction. Thus, the wear at a certain position and instant is extrapolated to the whole circumference.

- At the contact interface there are not any pollutants. The effect of pollutants is considering by modifying the friction coefficient or introducing new wear laws.

- Energy transfer models: These models compute the energy dissipated at the wheel – rail interface and associate it with the wear rate, which can be ultimately associated with the wear depth. There are various models, each with its own wear law: Zoroby’s model, which is based on the energy flow; the model developed by the British Railway Research (BRR), which is based on a non-continuous wear law depending on the wear regime (mild, transition, severe); and the model developed by the University of Sheffield (USFD), which is based on a continuous wear law divided into several regimes (mild, severe, catastrophic).

- Reye – Archand – Khruschchov (RAK) model: This is the simplest model and characterizes the abrasive wear appearing at the slip zone of the contact area. In this model, the volume of material lost is expressed as function of the slip speed, normal force, hardness of the wheel material (steel) and a coefficient coming from a wear chart divided in wear zones depending on the normal pressure and the slip speed.

2.4.10. Prediction of RCF

- If , RCF is not enough for initiating cracks since the tangential force is moderated (utilized friction).

- If , this is the limit situation. Cracks are not initiated as the shear stress at yield () has not been reached yet.

- If , RCF initiates cracks on the surface since the tangential force is elevated (utilized friction).

2.5. Software Choice

2.6. Calculation Scenarios

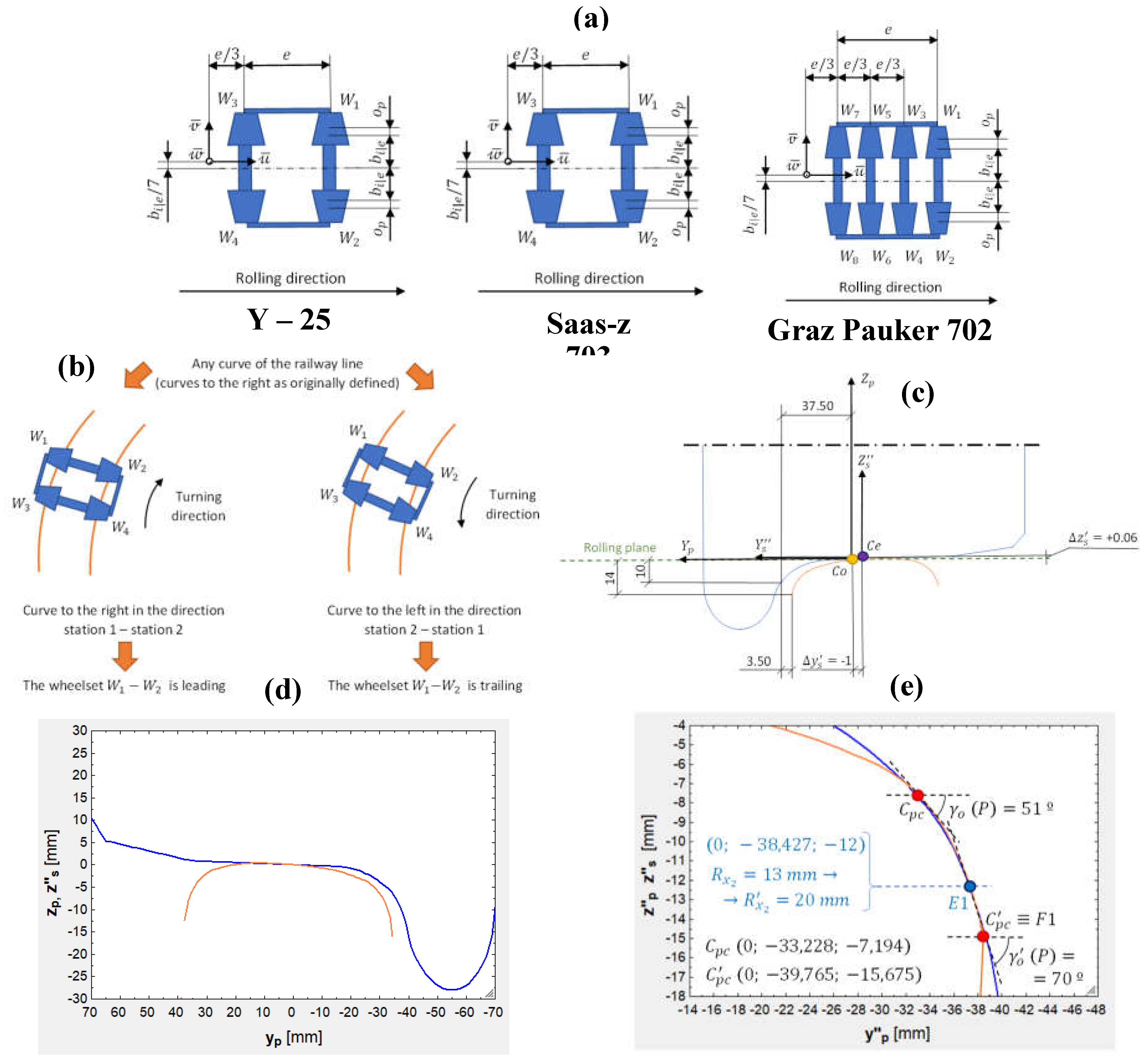

- Y – 25: This bogie consists of four wheels (thus, it is composed of two wheelsets) and it can take up 45 t in total (22.5 t/axle) at a maximum speed of 120 km/h. The total wheelbase () is variable and the wheels are braked, in general, by brake shoes. The wheel nominal diameter () ranges from 920 mm (original, maximum) to 840 mm (operational minimum).

- Saas-z 703: This bogie also consists of four wheels (so two wheelsets) and it can take up 32 t (16 t/axle) at 100 km/h. The total wheelbase () is variable and the wheels are braked by brake disks. The wheel nominal diameter () ranges from 680 mm to 630 mm.

- Graz Pauker 702: This bogie is composed of eight wheels (so four wheelsets) and it can withstand 20 t (5 t/axle) at 100 km/h. The total wheelbase () is variable and the wheel nominal diameter () ranges from 355 to 335 mm.

- Axle load (): If a constant axle load value were given for all of the cases, then the wheels would be overloaded in some scenarios, while underloaded in others. On the one hand, some values as high as 22.5 t/axle would be unrealistic and unfeasible for the 680 and 355-mm wheels. On the other hand, some values as low as 5 t/axle would be realistic and feasible, although the smallest wheel (355 mm) would be fully loaded, working at maximum normal pressure and tangential stresses at the tread – rail interface, while the biggest wheel (920 mm) would be barely loaded, working at low values of those variables. In order to ensure (as much as possible) the same conditions, the axle load generating the same normal pressure is to be chosen. Specifically, the axle load generating a 1,235 MPa normal pressure, given that that is a common maximum value (maximum axle loads usually induce 1,100 – 1,300 MPa on the wheel and the mean value is 1,235 MPa), even if the axle load of the smallest wheel surpasses the manufacturer’s limit.

- Flange radius (): It is the addition of the nominal rolling radius , which is a half of ) and a constant. So decreases in proportion with .

2.7. Input Data

- Initial and final metric points ( and , respectively).

- Type of stretch: RECTA (straight), CIR (circular curve), CLO (clothoid), PARACUAD (quadratic parabola) or PARACUB (cubic parabola).

- Direction of the curve: NING (the stretch is straight), IZDA (curve to the left) or DCHA (curve to the right).

- Position of the bogie at the curve: NING (the stretch is straight), ENT (the bogie is entering the curve), SAL (the bogie is exiting the curve).

- Curve radius (), cant () and inclination ().

- Initial and final maximum speed allowed ( and , respectively).

3. Results

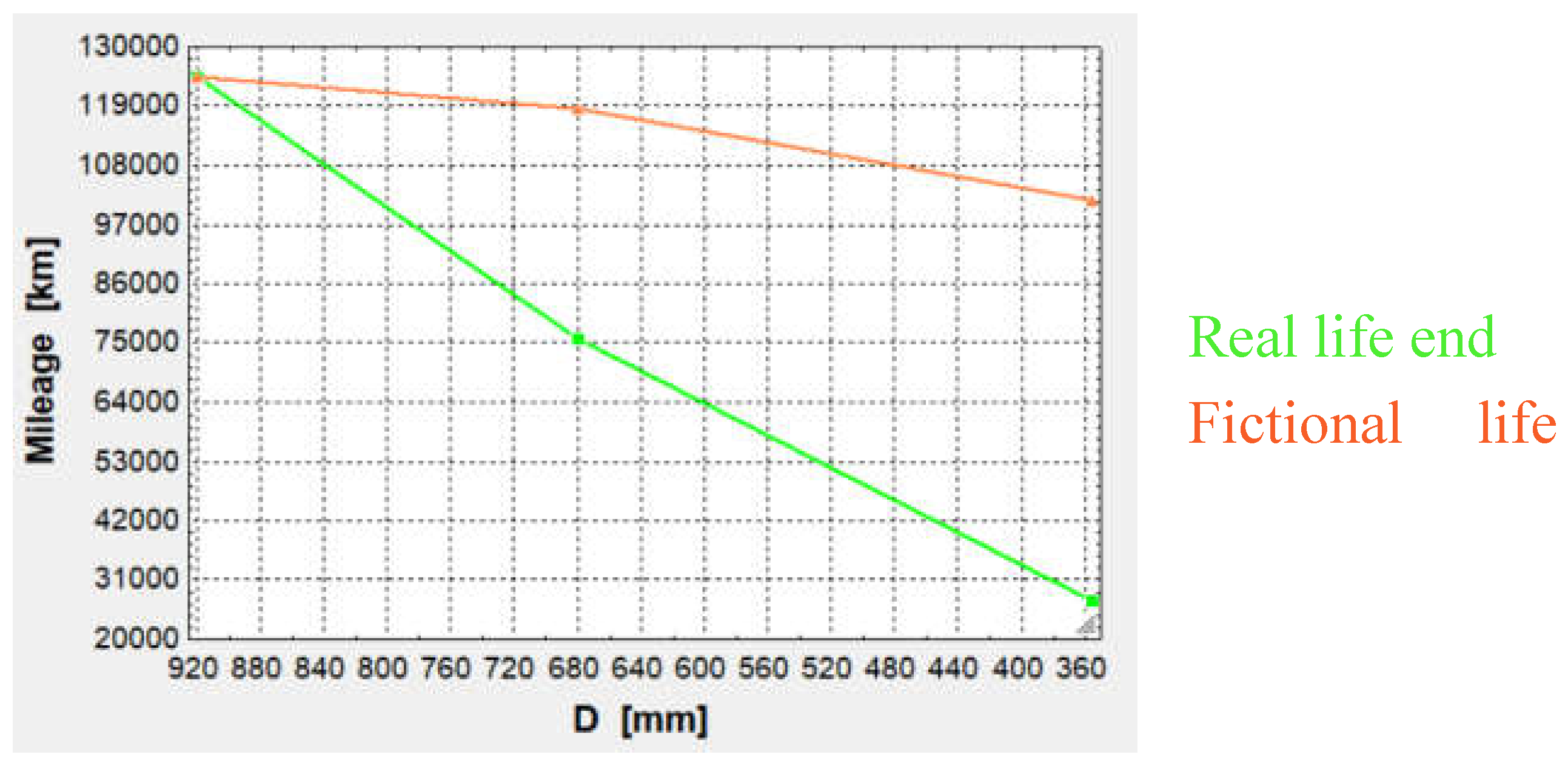

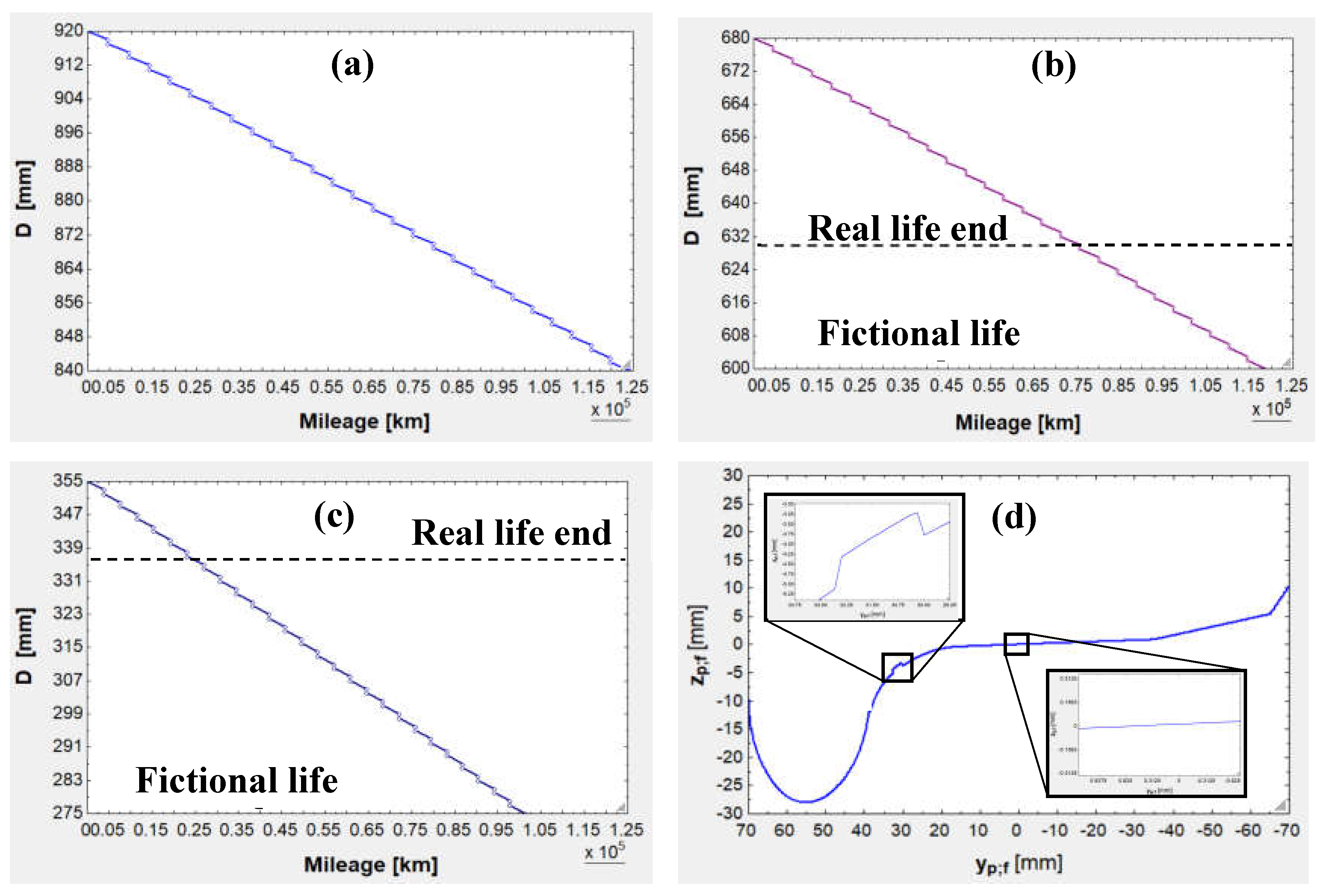

- 920-mm wheels can travel for 124,275 km until reaching an 840-mm diameter, losing 2 mm in diameter at every reprofiling cycle. At that point, the worn-out profile will be discarded for safety and operational reasons.

- 680-mm wheels are able to travel for 75,648 km until reaching their minimum allowed diameter: 630 mm. This is the real life end for this wheel, yet the wear – reprofiling cycles have been extended, as if the final diameter could be 600 mm for the difference between 680 and 600 is the same as that of 920 and 840. In this fictional situation, the wheel would have traveled 118,683 km (fictional life end).

- 355-mm wheels are capable of traveling 26,983 km until reaching their minimum allowed diameter: 335 mm. This is the real life end for this wheel, yet the wear – reprofiling cycles have been extended, as if the final diameter could be 275 mm for the difference between 355 and 275 is the same as that of 920 and 840. In this fictional situation, the wheel would have traveled 101,433 km (fictional life end).

4. Discussion

- Comparing the real life ends (124,275; 75,648 and 26,985 km) in percentual terms with respect to the first value, it is obtained that 680-mm wheels’ life is 30.13 % shorter and the 355-mm wheels’ is 78.29 % shorter.

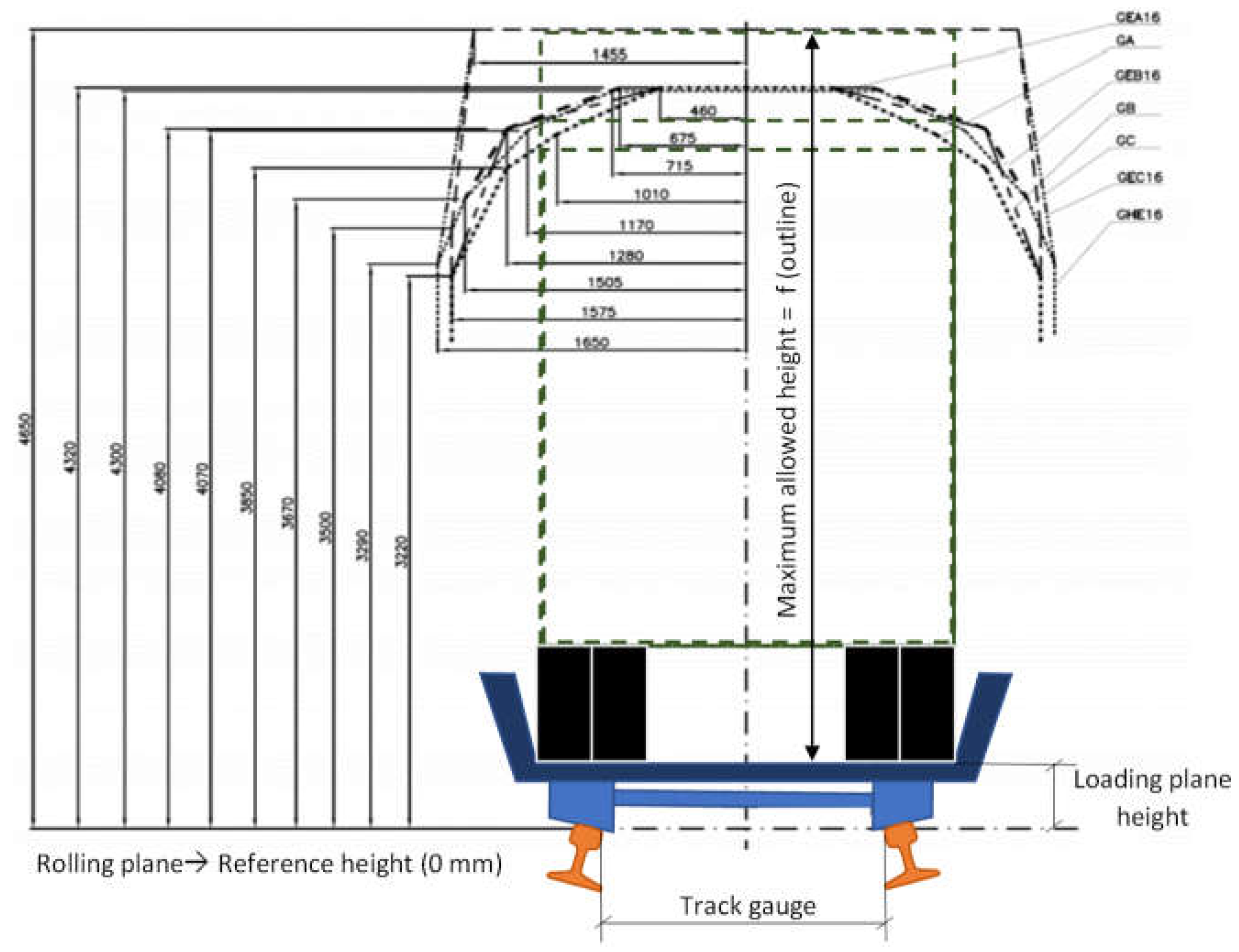

- Due to the elevated life shortening of 355-mm wheels, operators prefer using bigger wheels. For example, in Ref. (Pellicer & Larrodé, 2021), 380-mm wheels, which are mounted on the Saadkms690 bogie, are presented, which can be reprofiled until reaching 335 mm and the difference between both values (45 mm) is 25 mm higher than for 355-mm wheels (20 mm). Escalating the life of 355-mm wheels heuristically with the ratio 45/20, the result is 43,176 km, only 65.26 % shorter than 920-mm wheels’ life. This is very advantageous despite the elevation in 25 mm of the loading plane height, so replacing 355-mm wheels by 380-mm wheels will ultimately depend on the application (semi-trailers’ heights and tunnels and bridges’ loading gauges).

- The distance difference between reprofiling (the reprofiling span) is very variable when reprofiling a same wheel and, obviously, when moving across wheels, so adopting arithmetic mean values is required. The mean value is 4,603 km for 920-mm wheels, 4,396 km for 680-mm ones and 3,757 km for 355-mm ones.

- Should the wagons perform routes Albarque – Zacarín – Albarque (75.272 km) a week, then reprofiling periodicity should be . Using the average value 4,250 km, the approximate result obtained is .

- If all of the wheels were reprofiled the same number of cycles (always eliminating 80 mm in diameter), then the wheels’ life (fictional, as eliminating 80-mm would be against the manufacturers and operators’ regulations) would be: 118,683 km for 680-mm wheels and 101,433 km for 355-mm wheels. The former value es 4.50 % lower than that of 920-mm wheels (124,275 km), while the latter value is 18.38 % lower.

- These trends are summarized in Figure 17, where it can be seen that neither the behavior of the real life end nor that of the fictional life end are linear:Figure 17. Trends summary.

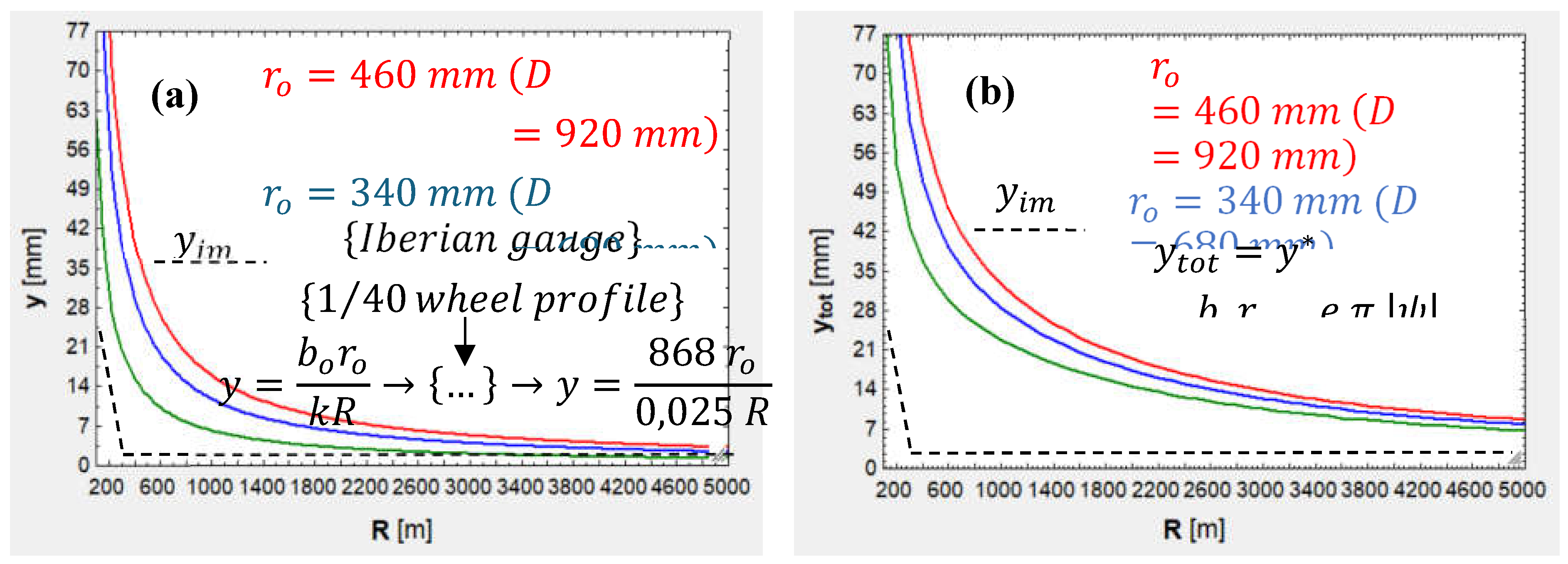

- This non-linear behavior responds to the different kinematic response of reduced-diameter wheels when negotiating curves. As demonstrated by Redtenbacher’s formula, uncentering is proportional to wheel radius (to wheel diameter in turn, as radius is the half), so not only do reduced-diameter wheels uncenter less than ordinary-diameter ones, but also their flanges will push against the rails less intensely. Moreover, the bogies where reduced-diameter wheels are mounted are less loaded, which will further reduce the force exerted by the rail on the flange (coming from force and torque balances). Figure 18(a) illustrates partial uncentering (differential effect) for the three scenarios and shows how saturation () is reached at a lower radius threshold for reduced-diameter wheels, while Figure 18(b) shows total uncentering (adding bogie rotation) in the worst case (leading wheelset, outer wheel), but even in this case, flange – rail contact is less aggressive owing to dynamics:Figure 18. (a) Partial uncentering for different and values; (b) Total uncentering for the same values.Figure 18. (a) Partial uncentering for different and values; (b) Total uncentering for the same values.

- The results for the three scenarios have been obtained for a 1,235-MPa normal pressure at the tread contact area with the rail when the wheels run on straight tracks, attaining such value by adjusting axle load for each scenario. Pressures existing at the flanges have not been equated due to the variability of the force exerted by the rail on the flange on the curve radius, which would make it very difficult to obtain unique axle load values.

- It is necessary to limit axle load on reduced-diameter wheels, as their contact area with the rail is reduced as well and the normal pressure is proportional to the load – area ratio. This reduction in the contact area responds to the decrease in the longitudinal radius , which is proportional to the wheel diameter. With a lower value a greater longitudinal relative curvature () is obtained, which dismishes the intersection between the theoretical paraboloids and, as a result, the contact patch size (as diminishes, the longitudinal semi-axis (a) does as well).

- Flange wear is between 10 and 1,000 times more intense than tread wear, so the former has been taken for elaborating the curves. This is due to the fact that lateral radii are very reduced for flange – rail contact ( mm, mm), opposing tread – rail contact radii ( mm, ), increasing in turn the relative lateral curvature (), which diminishes the intersection between the theoretical paraboloids and, as a result, the contact patch size (as diminishes, the longitudinal semi-axis (b) does as well). This size is smaller than that of the tread contact patch.

- Wheel diameter is more influential on tread wear than on flange wear. This owes to the fact that the radius (proportional to wheel diameter) is dominating, along with the radius (which is in the same order of magnitude), at the tread ( and ). In contrast, at the flange, is not the dominating radius, being dominated by and values, which are in a lower order of magnitude ( and ), and and hold constant independently of wheel diameter.

- RCF is predicted for every flange – rail contact (except for isolated cases where the 355-mm wheel is negotiating a curve with a radius closely below 1,850 m, being this the threshold radius in this case) as a consequence of the high normal pressure (5 – 7 GPa) at the flange contact area with the rail. Although the contact patch size is smaller than that of the tread contact patch, such a high pressure is withstandable by the material since indentation is elevated (0.2 – 0.3 mm) and pressure can stack in many layers (isobaric surfaces), as in hydrostatics.

- RCF effects can be mitigated by setting a reduced wear depth limit and in the current work it has been so due to the hypothesis established. In real operation, it is the economical factor the one prioritized, which forces to find the trade-off between crack growth and wear depth limit.

- As a consequence of RCF and the fatigue induced during reprofiling (which leaves residual stresses) and also for operational safety reasons, operators’ internal regulations forbid eliminating more than 80 mm in diameter for a 920-mm wheel, more than 60 for a 680-mm one and more than 20 for a 355-mm one.

- Last, Table A4 (Appendix C) gathers the RCF and wear results for the three different wheels when negotiating the tightest curve, the one with the 265-m radius. As it can be seen, even though the forces and RCF are less aggressive for reduced-diameter wheels, the wear depth increases as the wheel diameter decreases, for reduced-diameter wheels must revolve more times around its diameter so as to cover the same linear distance. However, the increase in wear depth is not simply inversely proportional to diameter (Figure 17 shows the same non-linear trend).

5. Conclusions

- Regarding kinematics, reduced-diameter wheels negotiate curves more smoothly than ordinary-diameter wheels, as their uncentering is lower, so their flanges touch the rails less frequently (the threshold radius is lower as well).

- Regarding dynamics, flange – rail contact is softer. When reduced-diameter wheels’ flanges touch the rails, they do it less intensely (uncentering forces are not so intense). Also, the force exerted by the rails on the flange is lower because the bogies based on reduced-diameter wheels are less loaded, so the force and torque balances lead to lower rail – flange forces.

- Variation of other parameters different from nominal wheel diameter so as to study their influence on wheel wear.

- Reformulation of the algorithm in order to mesh the contact patch and execute calculations globally, including all of the elastic microslips.

- Consideration of conformal contacts, also by means of finite elements as it is not possible to apply Hertz’s solution to this type of contacts.

- Addition of rail wear, which would have an impact on wheel wear as the rail curvatures would change (favorably, in general) and the contact positions would differ.

- Update of the contact parameters immediately after the wheel starts to wear out. Clearing out the “wear slope” at every instant would allow for the computation of the actual semi-conicity, contact angle and contact radii.

- Inclusion of the wheel and rail surface roughness, which would require a powerful software, able to characterize surfaces with a micrometric resolution. However, experiments could be performed on unworn profiles, whose roughness is higher.

- Consideration of a different friction coefficient for the tread and the flange since it is not always the same. Flange lubrication could also be considered, trying to optimize the friction value minimizing flange wear at narrow curves.

- Study of the effect of brake shoes on the tread. The shoes would tend to increase tread wheel, yet the overall effect is not very pronounced (the shoes wear out first) and the shoes are also helpful for wiping pollutants off of the wheels (for example, leaves).

- Optimization of the maximum wear depth taking into account economic factors: often reprofiling would lower derailment and crack-failure risks; however, that would come at a high cost, so the trade-off point should be optimized.

- Computation of the speed effects through finite elements, proving more accurate results by obtaining the elastic distortions for every different speed.

- Computation of the exact load distribution between the tread and the flange in the event of simultaneous contacts. Finite elements would allow knowing the real deformations, strains, stresses and forces at both areas.

- Inclusion of more superstructure factors modifying wheel (and rail) wear, such as warp, rail deflection, joints, irregularities and cant excess and deficiency under low static friction conditions.

- Inclusion of impacts between the wheels and the superstructure, especially those of the wheels with the switch frogs and track devices.

- Inclusion of other types of wheel damage shortening wheel life, such as cracks, flats and spalling.

- Extension of the algorithm to cover any other bogies belonging to the wagon (wagons have at least one more bogie).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Abbreviation | Definition | Unit (SI) | Abbreviation | Definition | Unit (SI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal semi-axis of Hertz’s ellipse | Degree of the function deceleration - time | ||||

| Lateral acceleration experienced by the vehicle | Number of axles on the vehicle | ||||

| Relative longitudinal curvature | Number of axles on the bogie | ||||

| Hertz’s ellipse area | Lateral Hertz’s coefficient | ||||

| Ratio between the minimum friction coefficient (infinite slip speed) and the maximum (null slip) | Reaction force of the rail on the wheel on the normal contact direction (normal force) | ||||

| Lateral semi-axis of Hertz’s ellipse | Reaction force of the rail on the wheel in the normal direction to the contact area at the (tread flange) at a wheel experiencing flange – rail contact | ||||

| Distance from track center to the rolling radius of the (inner| outer) wheel in relation to the curve | Normal force acting on the (outer| inner) wheel in relation to the curve | ||||

| Distance from track center to rolling radius | Normal force component in the radial |tangential direction (the tangential one is perpendicular to the radial one) | ||||

| Relative lateral curvature | Normal force component acting on the wheel (perpendicularly| tangentially) to contact area | ||||

| Exponential constant at friction law | Existing offset between the track gauge minus the flange – rail play and the distance between the nominal radius center of the wheelset wheels | ||||

| Effective size of contact patch | Horizontal distance between the center of the flange contact area center and the center of the wheel | ||||

| Contact tangential stiffness | Maximum contact normal pressure | ||||

| Contact tangential stiffness for the pure spin case | Initial | final metric point | ||||

| Longitudinal| lateral| vertical Kalker’s coefficient | Theorical rolling radius of the (outer| inner) wheel in relation to the curve | ||||

| Kalker’s coefficient (longitudinal |lateral) corrected according to non-dimensional slip components | Rolling radius of the (outer| inner) wheel in relation to the curve including the displacement due to the yaw angle | ||||

| Kalker’s coefficients on plane | Nominal rolling radius | ||||

| Nominal wheel diameter | Wheel radius measured until the flange contact patch | ||||

| Total bogie wheelbase (measured from its leading to trailing wheelset) | Real rolling radius | ||||

| Partial bogie wheelbase (measured between 2 next wheelsets) | Vertical Hertz’s coefficient | ||||

| Equivalent Young’s modulus of the materials in contact | Curve radius (measured from its center to the track axis) | ||||

| Young’s modulus of the rail | wheel | Rail lateral radius | ||||

| Sagitta of the inner rail in relation to the curve | Wheel lateral radius | ||||

| Magnitude of tangential force vector | Rail longitudinal radius | ||||

| Braking force | Longitudinal wheel radius | ||||

| Traction force | Magnitude of non-dimensional slip vector | ||||

| Longitudinal |lateral tangential force | Longitudinal| lateral non-dimensional slip | ||||

| Longitudinal |lateral tangential force translated to the reference frame | Magnitude of non-dimensional slip corrected with the spin contribution | ||||

| Lateral tangential force (lateral force) corrected with the spin contribution | Lateral non-dimensional slip corrected with the spin contribution | ||||

| Increase in lateral force due to spin | Wear index for the USFD law | ||||

| Maximum tangential force before rolling contact fatigue appears | Coordinate in the axis of the wheel contact area, in the reference frame | ||||

| Fatigue index | Coordinate in the axis of the flange outer part, in the frame | ||||

| Gravity acceleration | Coordinate in the axis of the wheel contact area, in the frame | ||||

| Equivalent shear modulus of the materials in contact | Coordinate in the axis of the flange outer part, in the frame | ||||

| Shear module of the rail | wheel | Longitudinal| lateral creepage | ||||

| Real cant of the railway line | Vehicle speed | ||||

| Center of gravity of height over the rolling plane | Final |initial vehicle speed | ||||

| Center of gravity of height over the rolling plane | Longitudinal| lateral slip speed | ||||

| Center of gravity of height over the rolling plane | Wheel width | ||||

| Total wheel wear depth (USFD law) | Wear rate (USFD law) | ||||

| Railway line gradient / slope | Wheelset uncentering | ||||

| Track gauge | Total wheelset uncentering | ||||

| Wheel semi-conicity or inclination | Available play for the bogie leading wheelset when it uncenters towards the outside of a curve | ||||

| Reduction coefficient for the initial slope of the traction curve at the stick | slip region | Available play for the bogie trailing wheelset when it uncenters towards the inside of a curve | ||||

| Auxiliary coefficient for the calculation of | Wheelset uncentering rate | ||||

| Length really rolled by a wheel | Total wheelset uncentering rate | ||||

| Longitudinal Hertz’s coefficient | Number of wheels on the bogie | ||||

| Spin torque |

| Abbreviation | Definition | Unit (SI) | Abbreviation | Definition | Unit (SI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction of the force normal to the wheel falling on the flange contact patch | Initial friction coefficient or maximum (null slip speed) | ||||

| Gradient angle | Equivalent Poisson’s ratio of the materials in contact | ||||

| Wheel contact angle | Poisson’s ratio of the rail | wheel | ||||

| Maximum indentation between the two bodies in contact | Gauge widening (at tight curves) | ||||

| Auxiliary coefficient for the obtention of coefficient | Density of the wheel material | ||||

| Tangential stress gradient at the stick region | Longitudinal displacement angle of the contact patch | rad | |||

| Tangential stress gradient at the stick region for the pure spin case | Maximum tangential stress transmitted | ||||

| Load (horizontal| vertical) on the flange contact patch | Tangential yield stress of the wheel material | ||||

| Play between the flange and the rail | Tilt angle | ||||

| Hertz’s angle | rad | Variation angle of tilt angle | |||

| Real cant angle | rad | Spin (rotational creepage) | |||

| Axle load | Yaw angle | ||||

| Vehicle tare | Variation rate of yaw angle | ||||

| Payload transported by the vehicle | Angular slip speed when braking per unit length | ||||

| Dynamic friction coefficient (or adhesion coefficient) |

Appendix B

| Variable | Value | Variable | Value | Variable | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| () | 0.400 | () | 1.235 – 2.747 | (◦) | 1.432 |

| (s/m) | 0.600 | () | 1 | (◦) | 1.432 |

| (m) | 1.800 | () | 0.400 | (◦) | 51 – 70 |

| (Pa) | (m) | (m) | |||

| (Pa) | (m) | (kg) | 20,000 | ||

| (m·s-2) | (m) | () | 0,400 | ||

| (Pa) | (m) | () | 0.550 | ||

| (Pa) | (m) | () | |||

| (m) | 0.512 | (m) | () | ||

| (m) | 1.573 | () | 0 | (kg·m-3) | |

| (m) | (m) | (Pa) | |||

| () | 0.025 | (m) | 0.140 | ||

| () | 0.025 | () | 0.750 |

Appendix C

| Variable | 920-mm wheel | 680-mm wheel | 355-mm wheel |

|---|---|---|---|

| (m) | 0.920 | 0.680 | 0.355 |

| (m) | 265 | 265 | 265 |

| () | 0.433 | 0.426 | 0.409 |

| () | 6.401109 | 6.599109 | 6.584109 |

| 468.088 | 367.463 | 367.887 | |

| 10.030 | 8.249 | 6.276 | |

| 0.636 | 0.611 | 0.881 | |

| 20.031 | 15.834 | 17.360 | |

| () | 23.368 | 23.207 | 21.192 |

| 55 | 55 | 55 | |

| 2.295 | 2.427 | 3.538 | |

| (N) | 1274 | 1034 | 1009 |

| (N) | 41,159 | 32,931 | 34,760 |

| (N·m) | 197.200 | 112.100 | 55.280 |

| () | -3.01310-3 | -2.91710-3 | -2.58110-3 |

| () | -5.76010-3 | -5.76010-3 | -5.76010-3 |

| 1.152 | -1.559 | -2.986 | |

| (N) | 85,465 | 69,622 | 76,224 |

References

- ADIF. Calificación, geometría, montaje y diseño de la vía; ADIF: Madrid, Spain, 1983 – 2021.

- ADIF. Declaración sobre la red. Annual Report. 2023. Available online (in Spanish): https://www.adif.es/sobre-adif/conoce-adif/declaracion-sobre-la-red (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- AENOR. Aplicaciones ferroviarias. Ruedas y carriles; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2011 – 2021.

- Alba, M. V. Optimización de la Política de Reperfilado de Ruedas para el Citadis 302, en la explotación de Metro Ligero Oeste. Revista Vía Libre Técnica 2015, 9, 29 – 38.

- Andrews, H. I. Railway Traction. The Principles of Mechanical and Electrical Railway Traction, 1st ed.; ElSevier Science: Oxford, 1986.

- Bosso, N.; Magelli, M.; Zampieri, N. Simulation of wheel and rail profile wear: a review of numerical models. Railway Engineering Science 2022, 30(4), 403 – 436. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W. et al. Experimental and numerical analysis of the polygonal wear of high-speed trains. Wear 2019, 440 – 441 (203079). [CrossRef]

- Chunyan, H. et al. A finite element thermomechanical analysis of the development of wheel polygonal wear. Tribology International 2024, 195(109577).

- Cooper, D. H. Tables of Hertzian Contact – Stress Coefficients. Report no. 387 from the Coordinated Science Laboratory. 1968. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/158319603.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Dirks, B.; Enblom, R.; Ekberg, A.; Berg, M. The development of a crack propagation model for railway wheels and rails. Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures 2015, 18(12), 1478 – 1491. [CrossRef]

- European Council. Directive 96/53. Official Journal of the European Communities 1996, L 235/59.

- Fissette, P. Railway vehicle dynamics. Teaching content. Catholic University of Louvain, Louvain. 2016. Available online: https://es.scribd.com/document/559372304/RailVehicles (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- González – Cachón, S. Tribological behavior of micro-alloyed steels and conventional C – Mn in pure sliding condition. PhD Thesis, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain, 2017. Available online (in Spanish): https://digibuo.uniovi.es/dspace/handle/10651/44961 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Greenwood, J. A. Hertz theory and Carlson elliptic integrals, Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2018, 119, 240 – 249.

- Hertz, H. R. Über die Berührung fester elastische Körper. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 1882, 92, 156 – 171.

- Jaro, L.; Folgueira, C. A. Las Autopistas ferroviarias: ¿Una apuesta de futuro en líneas mixtas de alta velocidad? Revista de Alta Velocidad 2012, 2, 73 – 96.

- Jiménez, P. Ferrocarriles. Teaching content. Polythecnical University of Cartagena. 2016. Available online (in Spanish): https://ocw.bib.upct.es/course/view.php?id=162&topic=al (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Kalker, J. J. Rolling contact phenomena - linear elasticity, CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences, 411th ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2000; Volume 411.

- Klein, S.A. Development and integration of an equation-solving program for engineering thermodynamics courses. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 1993, 1(3), 265–275. [CrossRef]

- Larrodé, E. Ferrocarriles y tracción eléctrica, 1st ed.; Editorial Copy Center: Zaragoza, España, 2007.

- Lyu, K. et al. Influence of wheel diameter difference on surface damage for heavy-haul locomotive wheels: Measurements and simulations. International Journal of Fatigue 2020, 132 (105343). [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. et al. The initiation mechanism and distribution rule of wheel high-order polygonal wear on high-speed railway. Engineering Failure Analysis 2021, 119(104937). [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Fomento; Ministère de l’Environnement, de l’Énergie et de la Mer. Servicios de Autopista Ferroviaria (AF) en los ejes Atlántico y Mediterráneo. Convocatoria de manifestaciones de interés. Consulta a los fabricantes y diseñadores de material móvil. Report. 2018. Available online (in Spanish): https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/180410_AMI_Constructeurs_rapport_ES-min.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Ministerio de Fomento. Orden FOM/1630/2015, de 14 de julio, por la que se aprueba la “Instrucción ferroviaria de gálibos”. Boletín Oficial del Estado 2015, 185.

- Montenegro, P.A.; Calçada, R. Wheel–rail contact model for railway vehicle–structure interaction applications: development and validation. Railway Engineering Science 2023, 31(3). [CrossRef]

- Moody, J. C. Critical Speed Analysis of Railcars and Wheelsets on Curved and Straight Track. Bachelor’s Thesis. Bates College, Lewison, USA, 2014. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/230689735.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Oldknow, K. Wheel – Rail Interaction Fundamentals. Course content. 2015. Available online: https://www.coursehero.com/file/185769149/PC-1-3-Wheel-Rail-Interaction-Fundamentals-WRI-2017-20170604pdf/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Ortega, E. Simulación del contacto rueda – carril con Pro/ENGINEER, Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Carlos III, Madrid, España, 2012. Available online (in Spanish): https://e-archivo.uc3m.es/entities/publication/1ad42047-7a29-4236-a081-52f4c2ec2646 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- de Paula Pacheco, P. A. et al. The effectiveness of different wear indicators in quantifying wear on railway wheels of freight wagons. Railway Engineering Science 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40534-024-00334-8 (accessed on 15 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, D. S.; Larrodé, E. Analysis of the rolling phenomenon of a reduced-diameter railway wheel for freight wagons, as a function of operating factors. Master’s Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2021. Available online (in Spanish): https://deposita.unizar.es/record/64448 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Pellicer, D. S.; Larrodé, E. Supplementary material of “Analysis of the rolling phenomenon of a reduced-diameter railway wheel for freight wagons, as a function of operating factors”. Mendeley Data, 3rd version, 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17632/xw3hxy5xcx.3 (accessed on 15 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Peng, B. et al. D. Comparison of wear models for simulation of railway wheel polygonization. Wear 2019, 436 – 437. [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, J.; Chollet, H. Wheel – rail contact models for vehicle system dynamics including multi-point contact. Vehicle System Dynamics 2005, 43(6 – 7), 455 – 483. [CrossRef]

- Pires, A. C. et al. The effect of railway wheel wear on reprofiling and service life. Wear 2021, 477 (203799). [CrossRef]

- Polach, O. A Fast Wheel – Rail Forces Calculation Computer Code. Vehicle System Dynamics 2000, 33(1), 728 – 739. [CrossRef]

- Polach, O. Creep forces in simulations of traction vehicles running on adhesion limit. Wear 2005, 258(7 – 8), 992 – 1000. [CrossRef]

- RENFE. Temario específico para las pruebas presenciales de la Especialidad Máquinas – Herramientas. Material de studio. 2020. Available online (in Spanish): https://www.renfe.com/content/dam/renfe/es/Grupo-Empresa/Talento-y-personas/Empleo/2024/ingenier%C3%ADa-y-mantenimiento/04.%20IYM%20Manual_%20Especialidad_Maquinas_Herramientasv2.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Rincón, L. A. Circulación en curva, esfuerzos y solicitaciones verticales en el ferrocarril convencional. Master’s Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2018. Available online (in Spanish): https://eupla.unizar.es/sites/eupla/files/archivos/AsuntosAcademicos/TFG/2013-2014/Civil/convocatoria_3/5rincongarcia.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Rovira, A. Modelado del contacto rueda-carril para aplicaciones de simulación de vehículos ferroviarios y estimación del desgaste en el rango de baja frecuencia. PhD Thesis, Polytechnical University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2012. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/14671 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Salas – Vicente, S.; Pascual – Guillamón, M. Use of the fatigue index to study rolling contact wear. Wear 2019, 436 – 437 (203036).

- de San Dámaso, R. La vía de tres carriles. Situación actual y perspectivas. Informe de la Dirección General de Operaciones e Ingeniería – Dirección Ejecutiva de Operaciones e Ingeniería de Red de Alta Velocidad. 2017. Available online (in Spanish): https://cip.org.pt/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Ref-33.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Sang, H. et al. Theoretical study on wheel wear mechanism of high-speed train under different braking modes. Wear 2024, 540 – 541 (205262). [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, J.; Vadillo, E. G.; Gómez, J. Influence of creep forces on the risk of derailment of railway vehicles. Vehicle System Dynamics 2009, 47(6), 721 – 752. [CrossRef]

- Sichani, M. S. On Efficient Modelling of Wheel – Rail Contact in Vehicle Dynamics Simulation. PhD Thesis, KTH Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. Available online: https://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?dswid=6030 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Sui, S. et al. Effect of wheel diameter difference on tread wear of freight wagons. Engineering Failure Analysis 2021, 127(105501). [CrossRef]

- Tao, G. et al. Polygonisation of railway wheels: a critical review. Rail Engineering Science 2020, 28(4), 317 – 345. [CrossRef]

- Tipler, P. A.; Mosca, G. Physics for Scientists and Engineers Vol. I, 6th ed.; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 2014.

- Vera, C. Proyecto Constructivo de una Línea Ferroviaria de Transporte de Mercancías y su Conexión a la Red Principal. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Seville, Seville, Spain, 2015. Available online (in Spanish): https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/44482 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Yassine, B. Los trabajos topográficos en la ejecución de una vía de ferrocarril de alta velocidad. Bachelor’s Thesis, Polytechnical University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2015. Available online (in Spanish): https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/54675 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Zeng, Y. et al. An Optimal Life Cycle Reprofiling Strategy of Train Wheels Based on Markov Decision Process of Wheel Degradation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23(8). [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value for 920-mm wheels scenario | Value for 680-mm wheels scenario | Value for 355-mm wheels scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| (m) | 0.920 | 0.680 | 0.355 |

| () | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| (m) | 0.467 – 0.475 | 0.347 – 0.355 | 0.185 – 0.193 |

| (kg) | 18,784 | 15,325 | 6,996 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).