Introduction

Healthcare systems worldwide can be broadly categorized into public, private, or mixed systems.

Each type has its own set of advantages and disadvantages, affecting not only the cost and accessibility of healthcare but also patient outcomes, including mortality rates (Smith, 2018; Johnson & Stoskopf, 2010). This article aims to provide a comparative analysis of mortality rates in public and private healthcare systems across different countries.

Objectives

To compare mortality rates in public and private healthcare systems worldwide. To discuss the factors contributing to these rates.

To provide recommendations for future research and policy changes.

Methodology

The article relies on existing literature, studies, and data up to July 2021 to compare mortality rates in public and private healthcare systems (World Health Organization, 2019; Davis et al., 2017). It also considers factors like healthcare spending, doctor-to-patient ratios, and the prevalence of medical errors (Makary & Daniel, 2016).

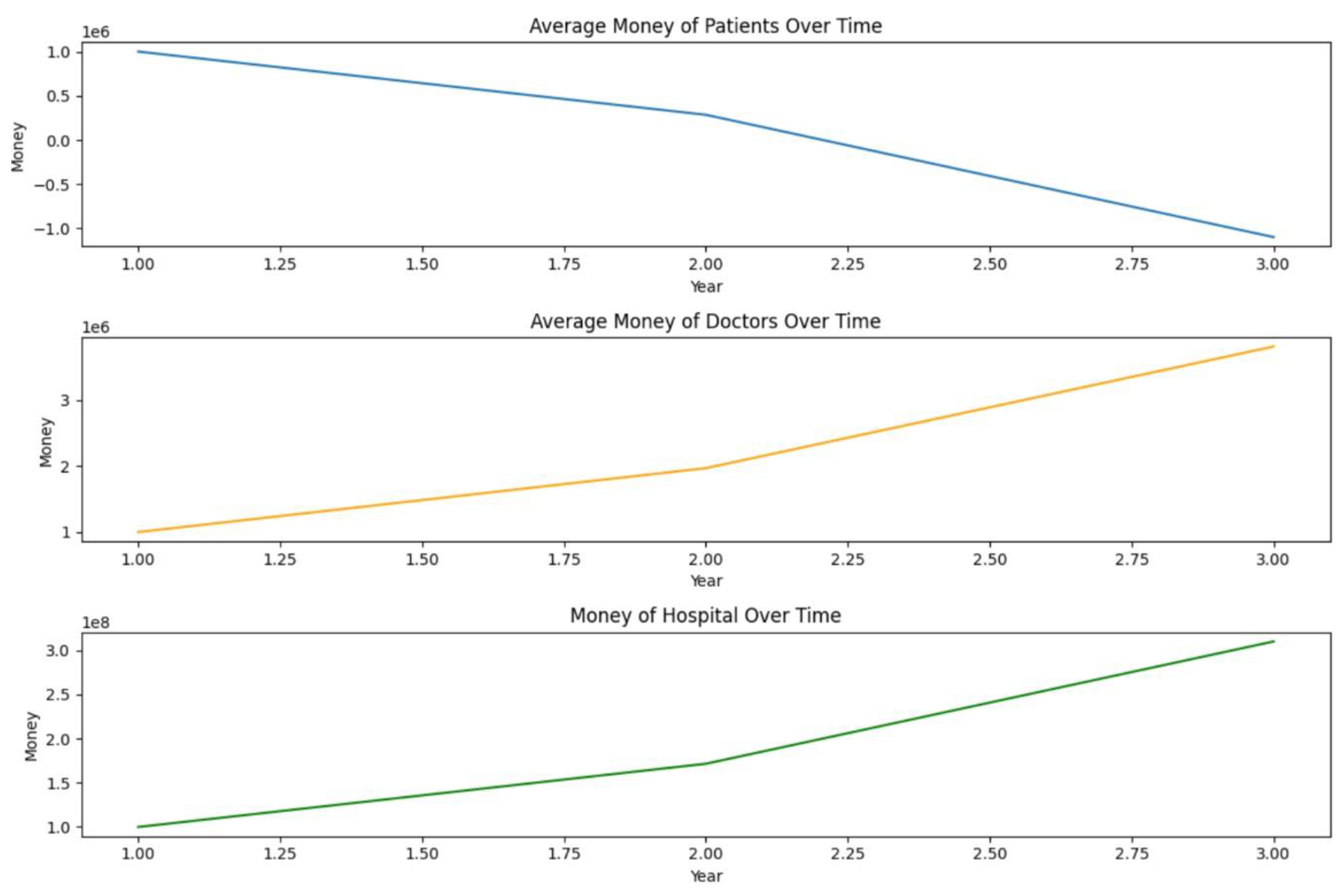

We made a simulation in Python firstly without any restrictions and secondarily (

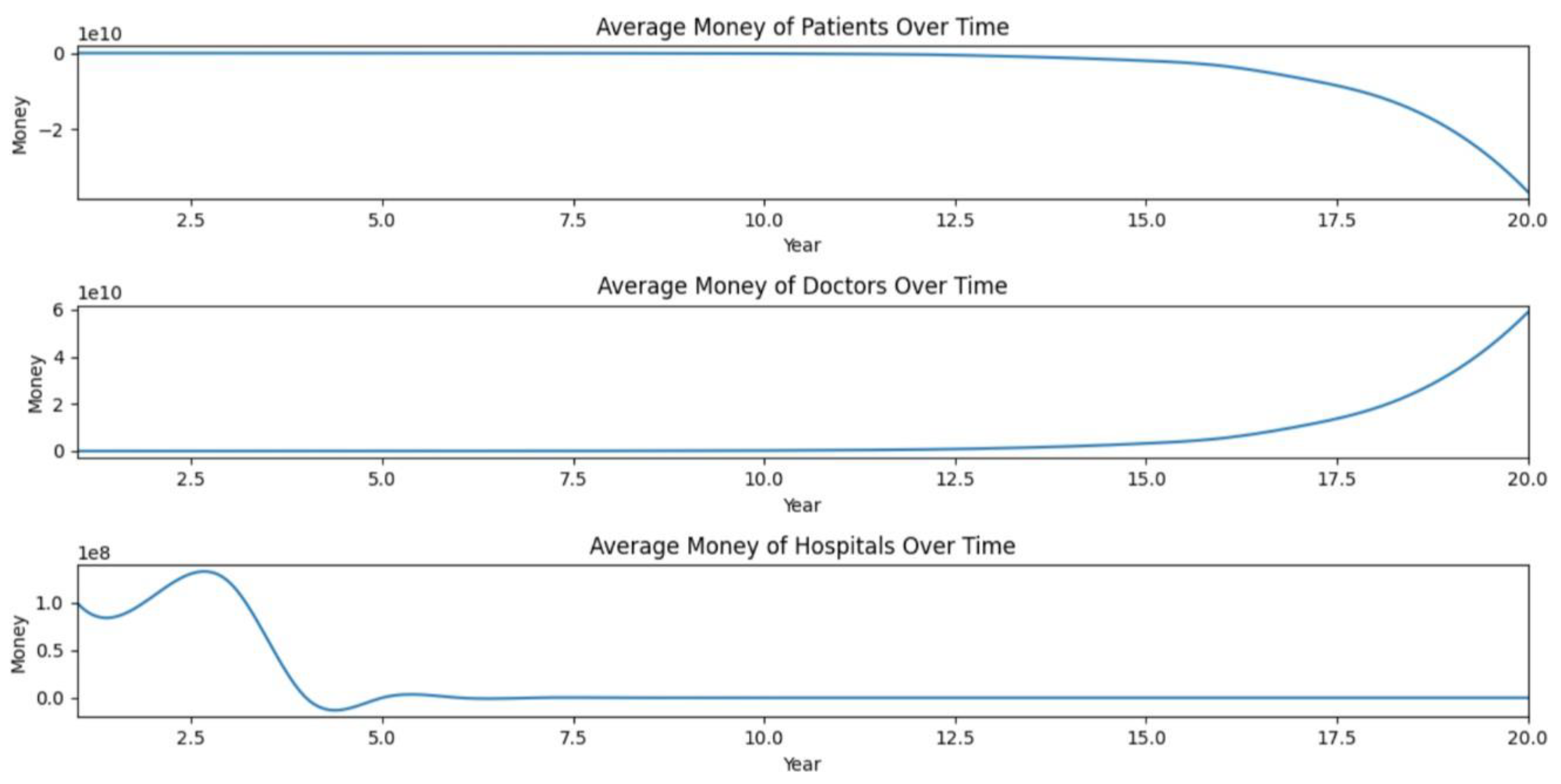

Figure 2) with the following restrictions:

Figure 1.

Doctors and Hospitals make a lot of money and Patients loose this surplus and get hurt.

Figure 1.

Doctors and Hospitals make a lot of money and Patients loose this surplus and get hurt.

The bad doctors pay a fine and can loose license if they are caught (randomly). This Fine is reverted to patients as a whole.

Bad Hospitals pay a fine and loose part of their reputation every time a doctor is caught. The money is reversed to patients.

Notice that even with that restrictions patients continue to loose money in the long run, doctors earn even more money, probably because of the elastic curve supply of doctors risk takers. The system is bound to hurt the patients and suggest private markets for health assistance may not be a good idea or, at least need severe regulations.

The simulation provides a simplified model of a complex issue, focusing on the financial incentives and risks for doctors and hospitals in a private healthcare system. It doesn't capture many other factors that are crucial for a comprehensive analysis of public vs. private healthcare systems. Here are some points to consider:

Public Healthcare:

Equal Access: Ensures that all citizens have access to healthcare regardless of their financial situation. Cost Control: Government regulation can potentially keep costs down.

Less Financial Motivation: Doctors and hospitals are not motivated by profit to the same extent as in a private system, which could lead to more conservative and necessary treatment.

Bureaucracy: Public systems can suffer from inefficiencies and long wait times.

Private Healthcare:

Innovation: Financial incentives can drive research and development. Quality of Service: Competition can improve service quality.

Inefficiencies due to profit maximization from Hospitals and risk takers Doctors that kill patients or provoque morbidities.

Choice: Patients have more options in choosing healthcare providers.

Cost: High-quality care can be expensive, and not everyone may have access to the same level of care.

Mixed System:

Balanced Approach: Combines the strengths of both public and private systems.

Choice & Access: Provides universal coverage while also offering the option for private, fee-based services.

Funding: The private sector can relieve some financial burden on the public system. Complexity: Requires careful regulation to ensure both systems coexist effectively.

Given the complexities involved, many countries opt for a mixed system to balance the strengths and weaknesses of both public and private healthcare. However, the "best" system can vary greatly depending on a country's specific needs, culture, and existing infrastructure.

In summary, whether healthcare services should be public, private, or a mixture of both is a complex decision that involves trade-offs. It's a topic of ongoing debate and research, and the optimal system likely varies from one context to another.

Results

Countries with predominantly public healthcare systems, such as the United Kingdom and Canada, generally have lower mortality rates compared to countries with predominantly private systems like the United States (Papanicolas et al., 2018).

Factors such as healthcare spending and doctor-to-patient ratios also significantly impact mortality rates (Reinhardt et al., 2004).

Discussion

Public vs. Private Systems:

Public healthcare systems often prioritize equal access and preventive care, which can lead to lower mortality rates (Starfield et al., 2005). However, they may lack in innovation and speed of service compared to private systems (Arrow, 1963).

Cost and Accessibility:

Private healthcare systems often have higher costs, which can limit accessibility and lead to higher mortality rates among uninsured or underinsured populations (Woolhandler et al., 2003).

Quality of Care:

While private healthcare systems often offer high-quality care, the focus on profit can sometimes lead to unnecessary procedures and medical errors, affecting mortality rates (James, 2013).

Profit-Driven Nature of Private Hospitals:

One of the most concerning aspects of private healthcare systems is their profit-driven nature (Porter & Teisberg, 2006). This can lead to a culture where unnecessary exams and procedures are encouraged to increase revenue. Such practices not only escalate healthcare costs but also expose patients to unnecessary risks, contributing to increased rates of mortality and morbidity (Baker et al., 2016).

Information Asymmetry and Risk Behavior:

Both public and private systems suffer from information asymmetry between doctors and patients (Akerlof, 1970). However, private systems may attract risk-taking doctors who prioritize performance metrics, potentially leading to higher mortality rates (Pauly, 1980).

Advantages of Mixed Systems:

Some countries employ a mixed system that combines the strengths of both public and private healthcare, aiming to offer both accessibility and high-quality care (Blendon et al., 2002).

Conclusions

The type of healthcare system—public, private, or mixed—has a significant impact on mortality rates (Glied, 2008). Public systems often excel in accessibility and preventive care but may lack in speed and innovation. Private systems offer high-quality care but can suffer from high costs and unequal access. A mixed system may offer a balanced approach, combining the strengths of both systems (Chandra et al., 2011). Further research is needed to provide more nuanced insights into the impact of healthcare system types on mortality rates.

References

- Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The Market for 'Lemons': Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488-500. [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K. J. (1963). Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care. The American Economic Review, 53(5), 941-973.

- Baker, L. C., Bundorf, M. K., & Kessler, D. P. (2016). The Effect of Hospital/Physician Integration on Hospital Choice. Journal of Health Economics, 50, 1-8.

- Blendon, R. J., Kim, M., & Benson, J. M. (2002). The Public Versus the World Health Organization on Health System Performance. Health Affairs, 20(3), 10-20.

- Chandra, A., Gruber, J., & McKnight, R. (2011). Patient Cost-Sharing and Hospitalization Offsets in the Elderly. American Economic Review, 101(1), 193-220. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K., Stremikis, K., Squires, D., & Schoen, C. (2014). Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, 2014 Update: How the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally. The Commonwealth Fund.

- Glied, S. (2008). Universal Public Health Insurance and Private Coverage: Externalities in Health Care Consumption. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 41(3), 752-769.

- James, J. T. (2013). A New, Evidence-based Estimate of Patient Harms Associated with Hospital Care. Journal of Patient Safety, 9(3), 122-128.

- Johnson, J. A., & Stoskopf, C. H. (2010). Comparative Health Systems: A Global Perspective. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Makary, M. A., & Daniel, M. (2016). Medical Error—The Third Leading Cause of Death in the US. BMJ, 353, i2139.

- Papanicolas, I., Woskie, L. R., & Jha, A. K. (2018). Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries. JAMA, 319(10), 1024-1039.

- Pauly, M. V. (1980). Doctors and Their Workshops: Economic Models of Physician Behavior. University of Chicago Press.

- Porter, M. E., & Teisberg, E. O. (2006). Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press.

- Reinhardt, U. E., Hussey, P. S., & Anderson, G. F. (2004). U.S. Health Care Spending in an International Context. Health Affairs, 23(3), 10-25.

- Smith, P. C. (2018). Performance Measurement for Health System Improvement: Experiences, Challenges and Prospects. Cambridge University Press.

- Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457-502.

- Woolhandler, S., Campbell, T., & Himmelstein, D. U. (2003). Costs of Health Care Administration in the United States and Canada. New England Journal of Medicine, 349(8), 768-775. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Global Health Expenditure Database.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).