Submitted:

10 August 2024

Posted:

13 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Dual-Readout Concept

2.1. Active regions

2.2. Methods for Separating the Scintillation and Äerenkov Light Components

2.3. Figures of Merit of a Dual-Readout Calorimeter

- Light yield. From general principles of calorimetry, it is well known that the concomitant effects of fluctuations in the development and detection of a particle shower are at the origin of the stochastic term in the energy resolution function. Therefore, experimentalists devote considerable effort to keeping those fluctuations at the smallest possible level. Of course, these arguments apply to both the Äerenkovand scintillation components for a dual-readout calorimeter. Since a hadronic shower has irreducible fluctuations related to the intrinsic fluctuation of the nuclear processes occurring between the shower particles and the detector, we want to keep stochastic fluctuations small compared to the latter. The theoretical limit for the stochastic term due to nuclear effect is ≈10-15% (corresponding to about 30-45 pe/GeV).

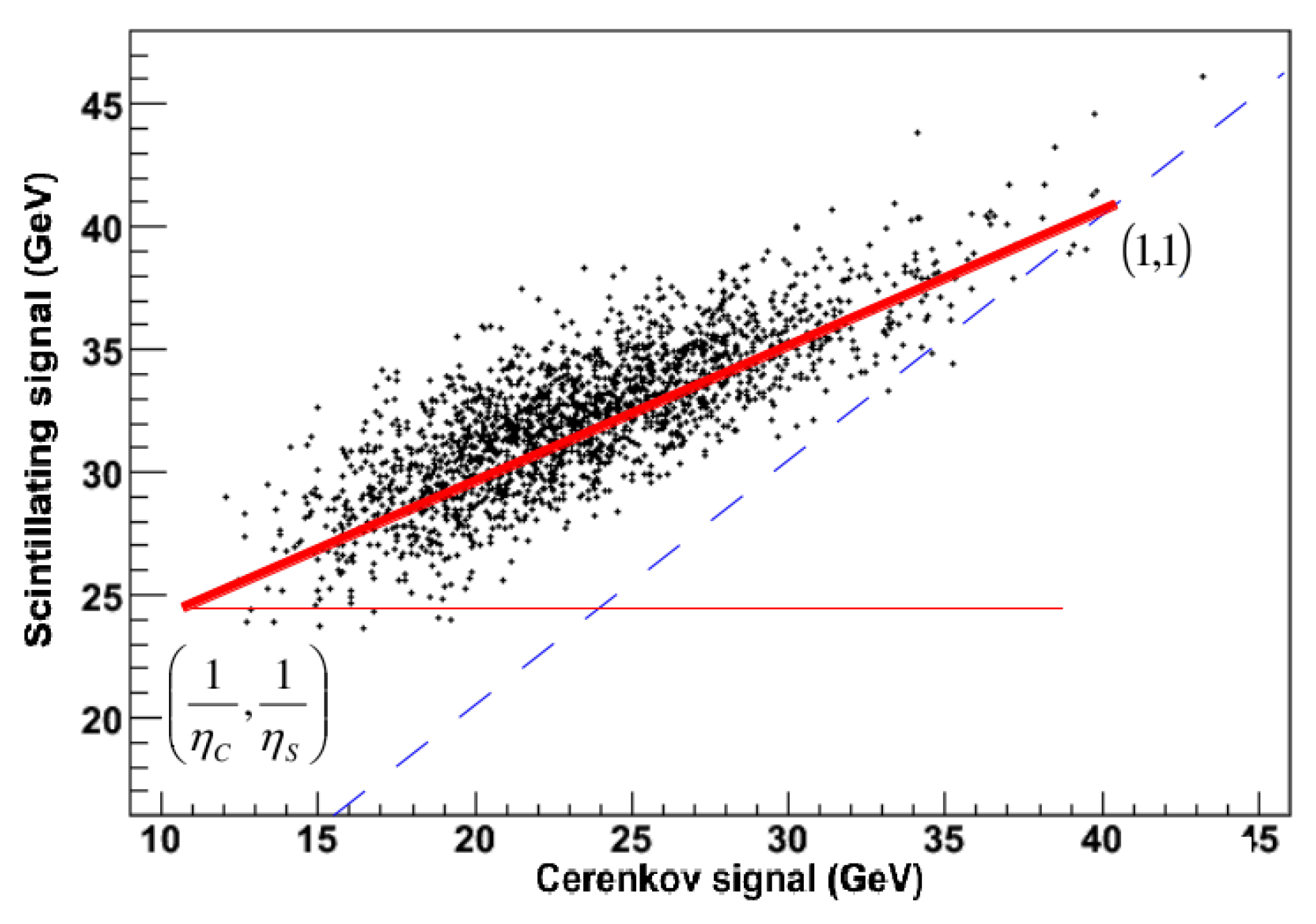

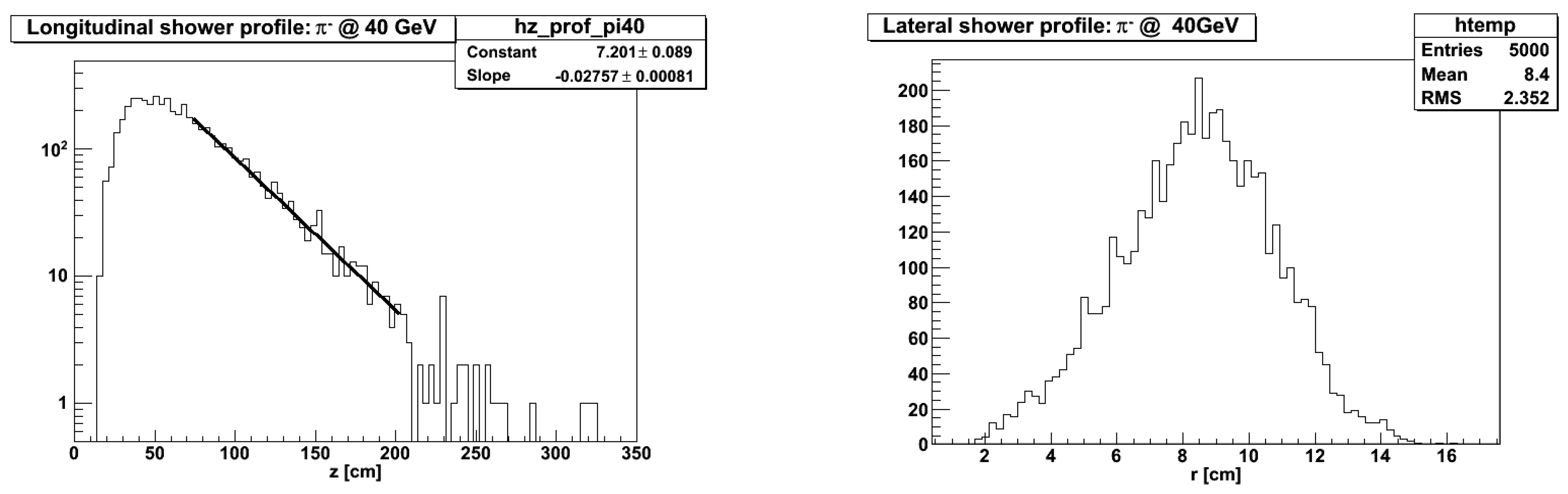

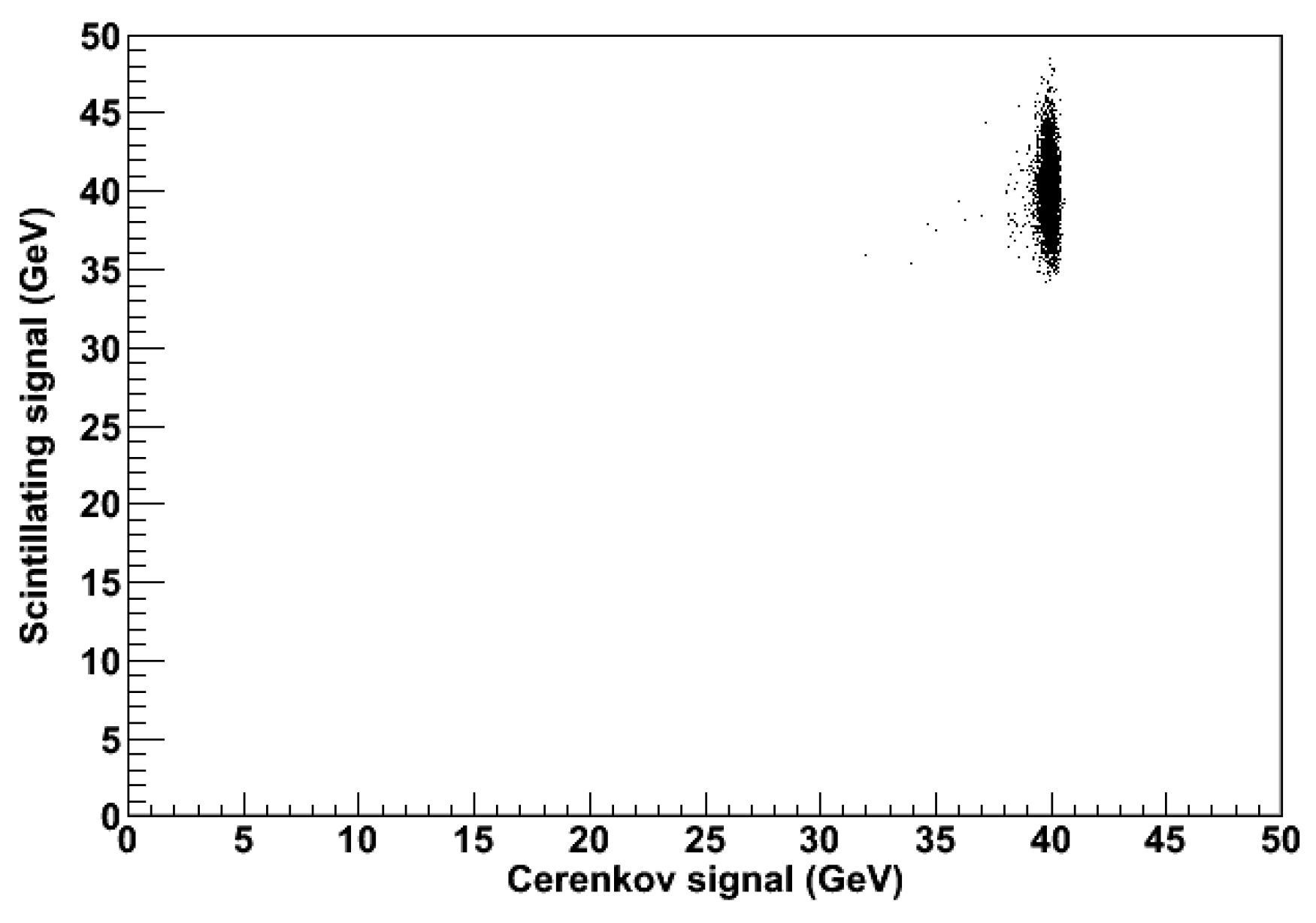

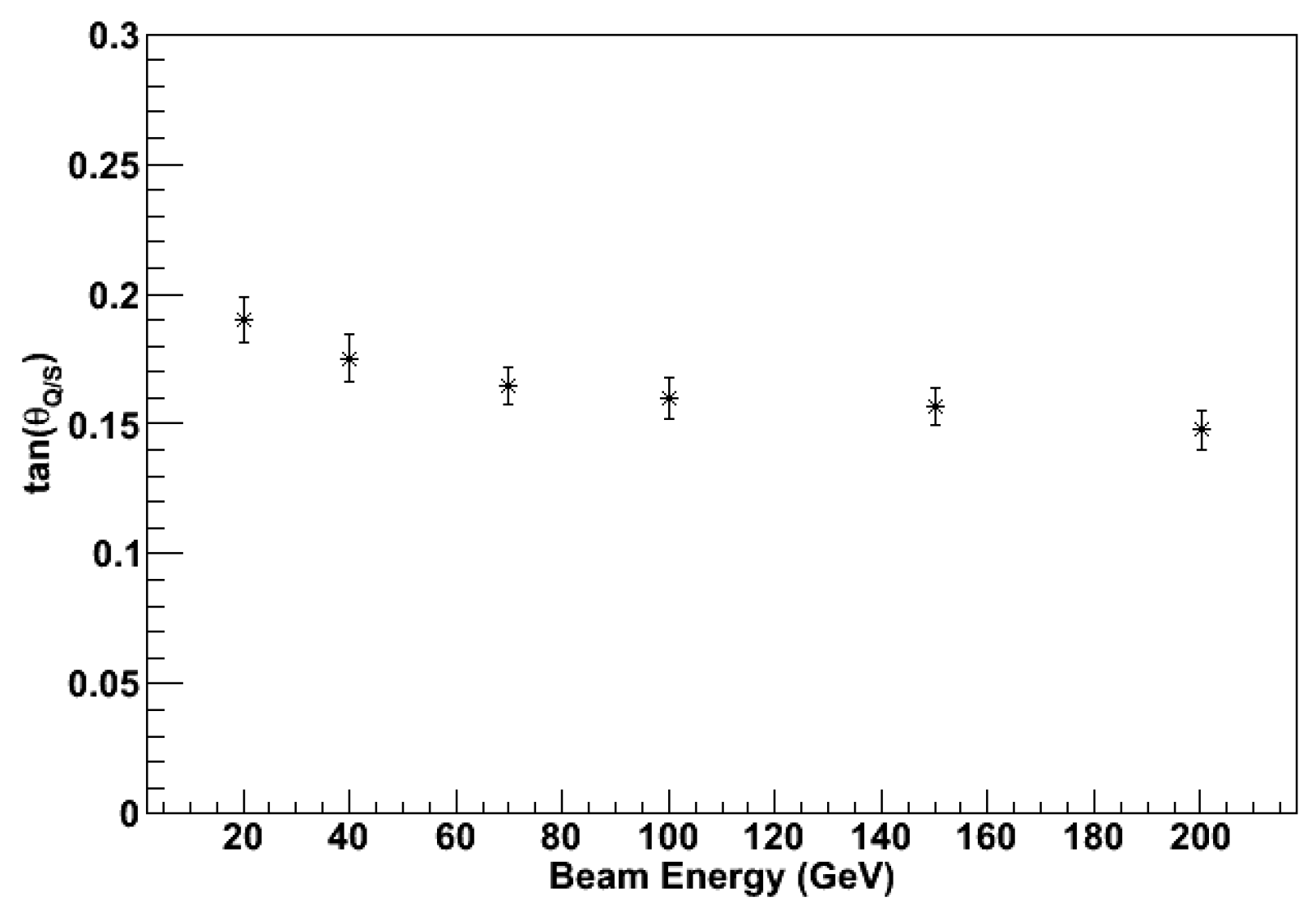

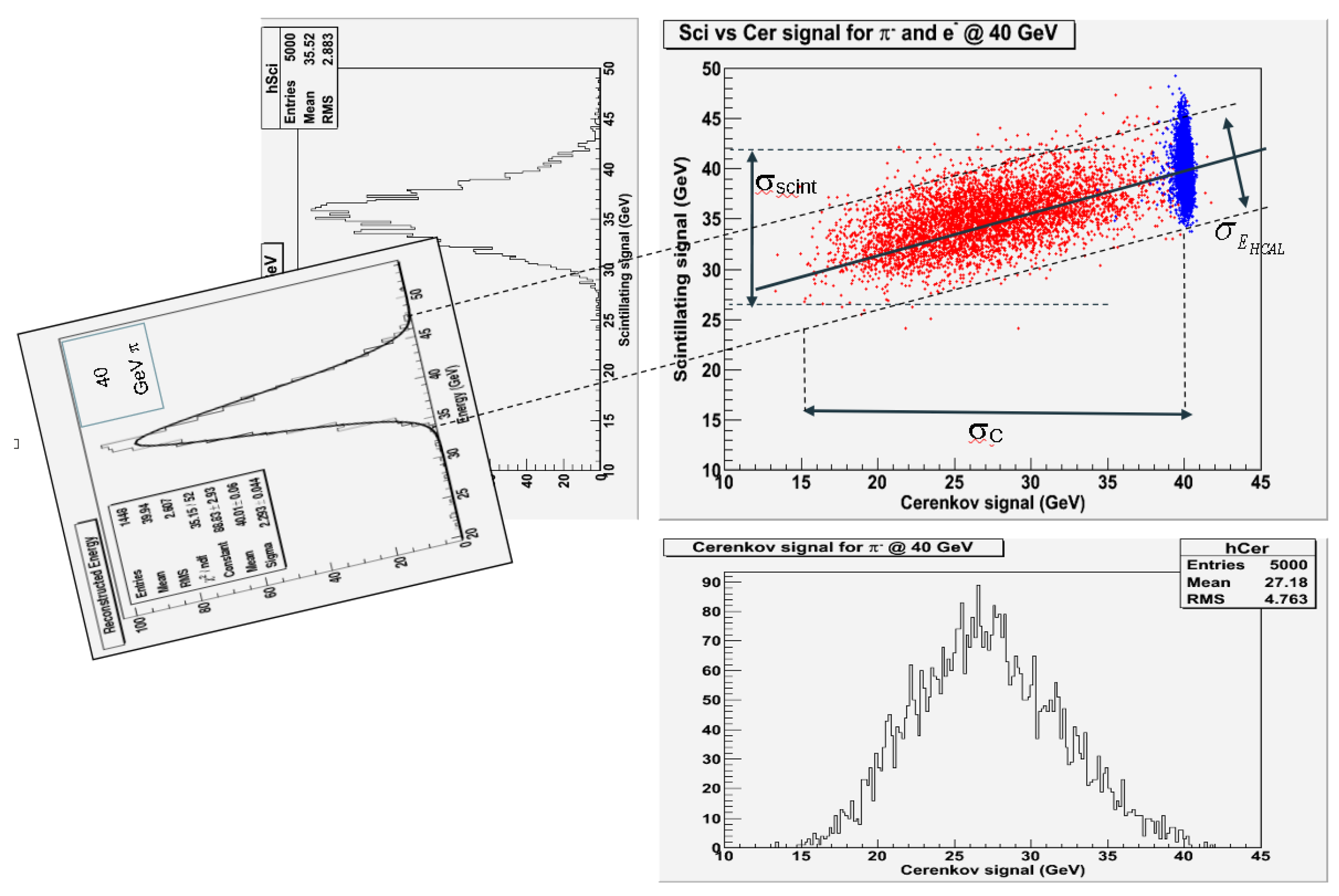

- The angle. The requirement for the system of Eqs. (1,2) to have a solution is that and have different values. In that case, it can be solved for and on an event-by-event basis. In practice, the scintillation and Äerenkov signals provide complementary information regarding the same EM or hadronic shower, which can be exploited to improve energy measurements. If = that complementarity is lost as the two readouts do not provide independent information. This is shown graphically in Figure 2 for a 40 GeV meson impinging onto a typical sampling calorimeter with a brass absorber, and scintillating and quartz fibers spaced by 1 mm. The point of the plot with coordinates corresponds to the cases where the primary particles decay predominantly via EM processes (essentially, and particles). In contrast, the point (1/,1/) corresponds to the opposite extreme case of a shower mostly populated by particles decaying non-electromagnetically. When the above points lie on the line the determinant of Eqs. 1 and 2 is null and the systems cannot be solved. On the other hand, the larger the angle the segment(1/,1/)- forms with the S axis, the more precise is the determination of , since its variance decreases correspondingly (cfr. Eq. 5). Therefore, can be considered as a figure of merit of the compensation power of a dual-readout calorimeter: as already noted in Section 1, the larger , the more compensating is the calorimeter. From Figure 2, we can express in terms of and through the following relationship:

3. Triple-Readout Calorimetry

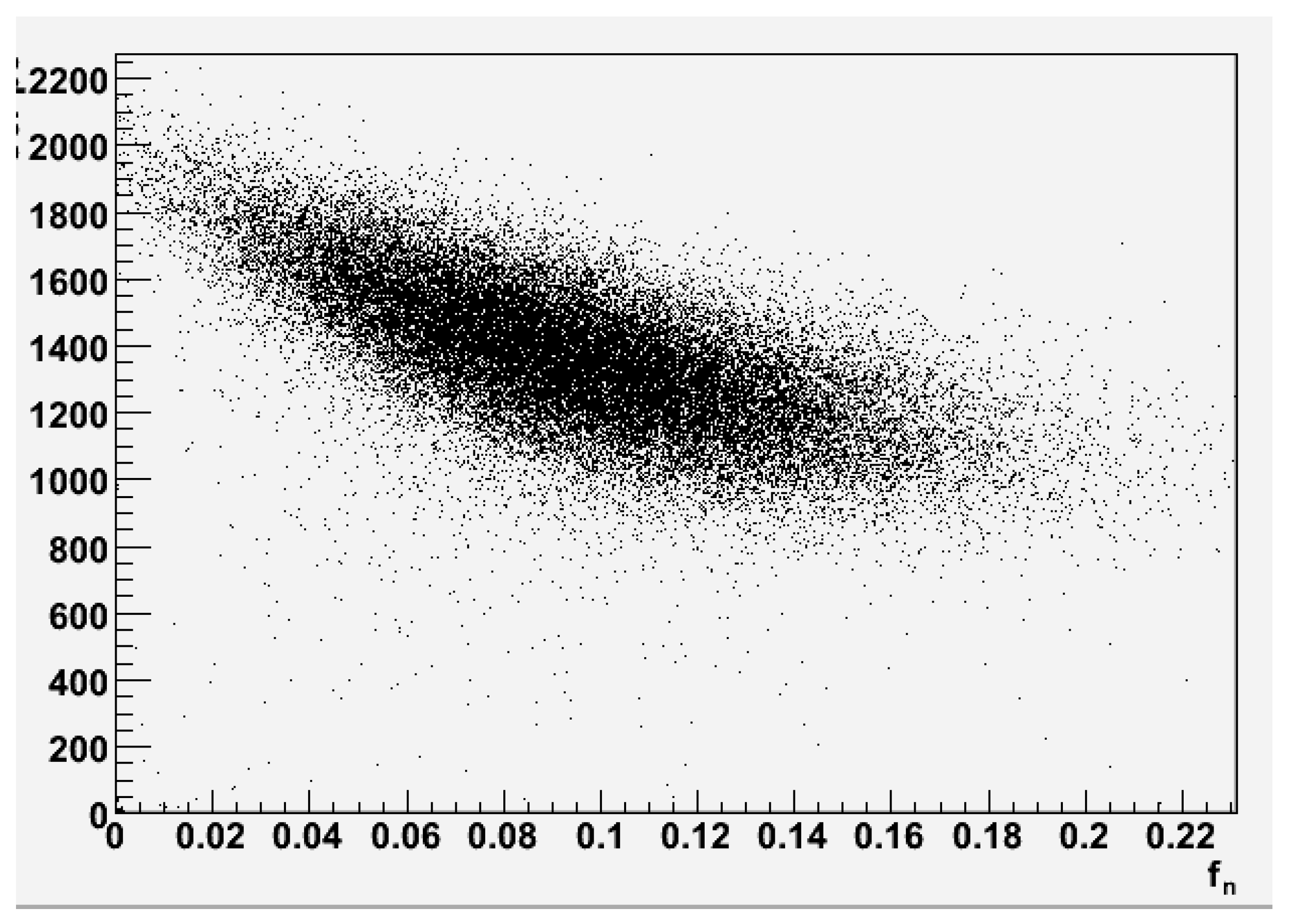

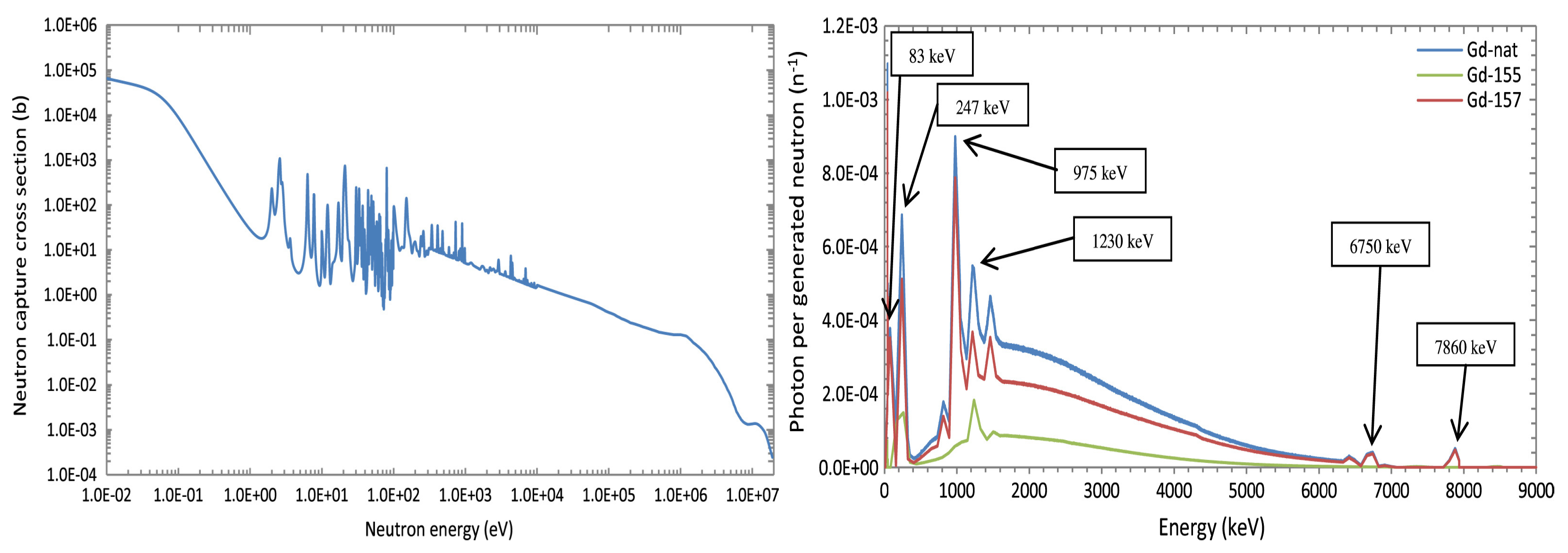

3.1. Neutrons Related Fluctuations

4. The Calorimeter

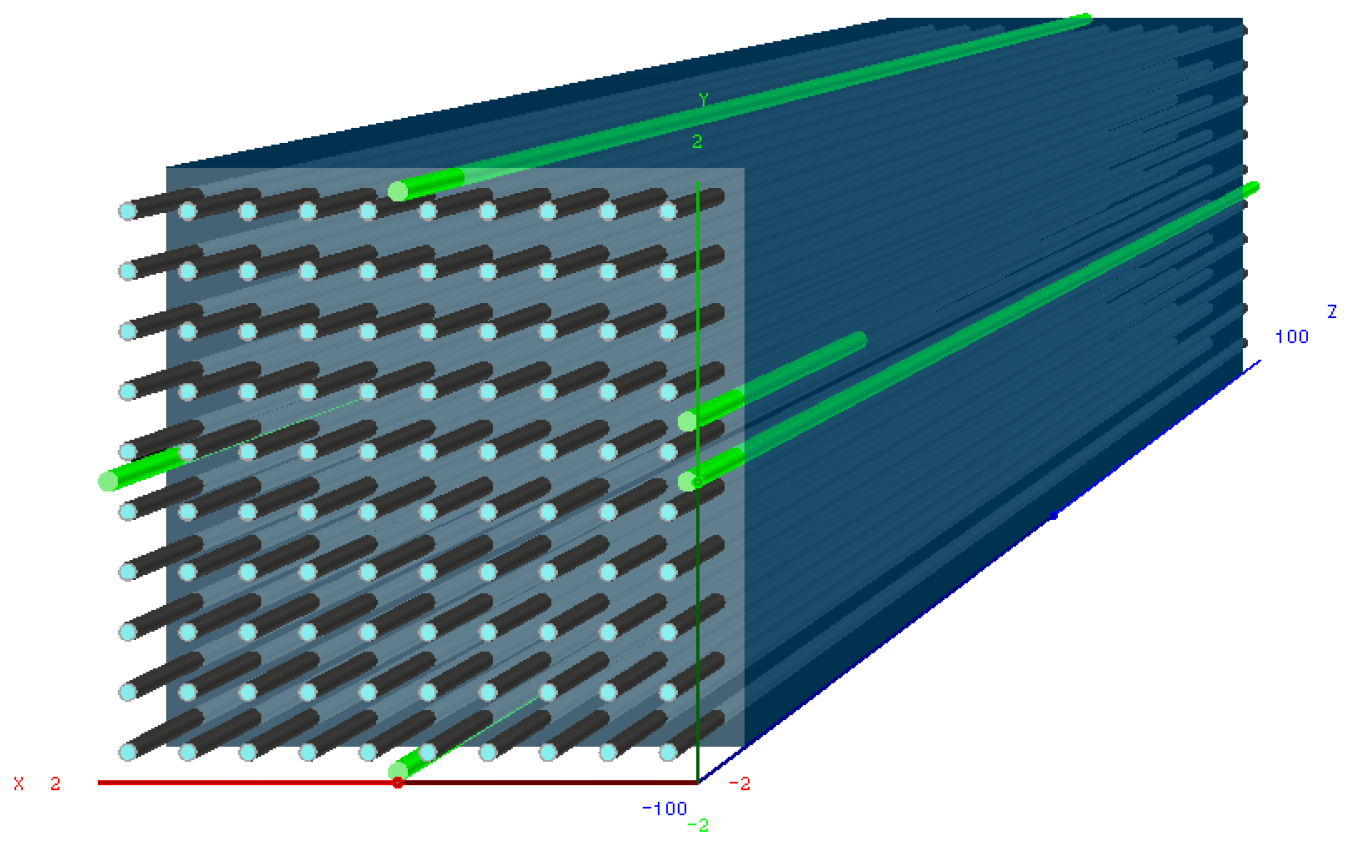

- The scintillation and Äerenkovcomponents are produced in distinguished volumes of the calorimeter, with no cross-talk between them. The light generated in each region is individually transported and read-out by individual photo-detectors.

- The calorimeter is integrally active, with minimal passive material. The latter should be limited to thin walls needed to physically separate the scintillating and Äerenkovregion or to optically shield and protect the outer boundary of a cell.

- It is highly desirable that the volume of the Äerenkovregion be much larger than the scintillation volume. In that case, the detector can be operated also as an EM calorimeter, with no need for a dedicated EM section in front of the hadron calorimeter. This choice is somehow complementary to the latest proposed dual-readout calorimeters (see, for example, Ref. [15]). Another advantage of having a large Äerenkovvolume is in the larger since the EM component of an hadronic shower develops mostly in a narrow core along the direction of the primary particle.

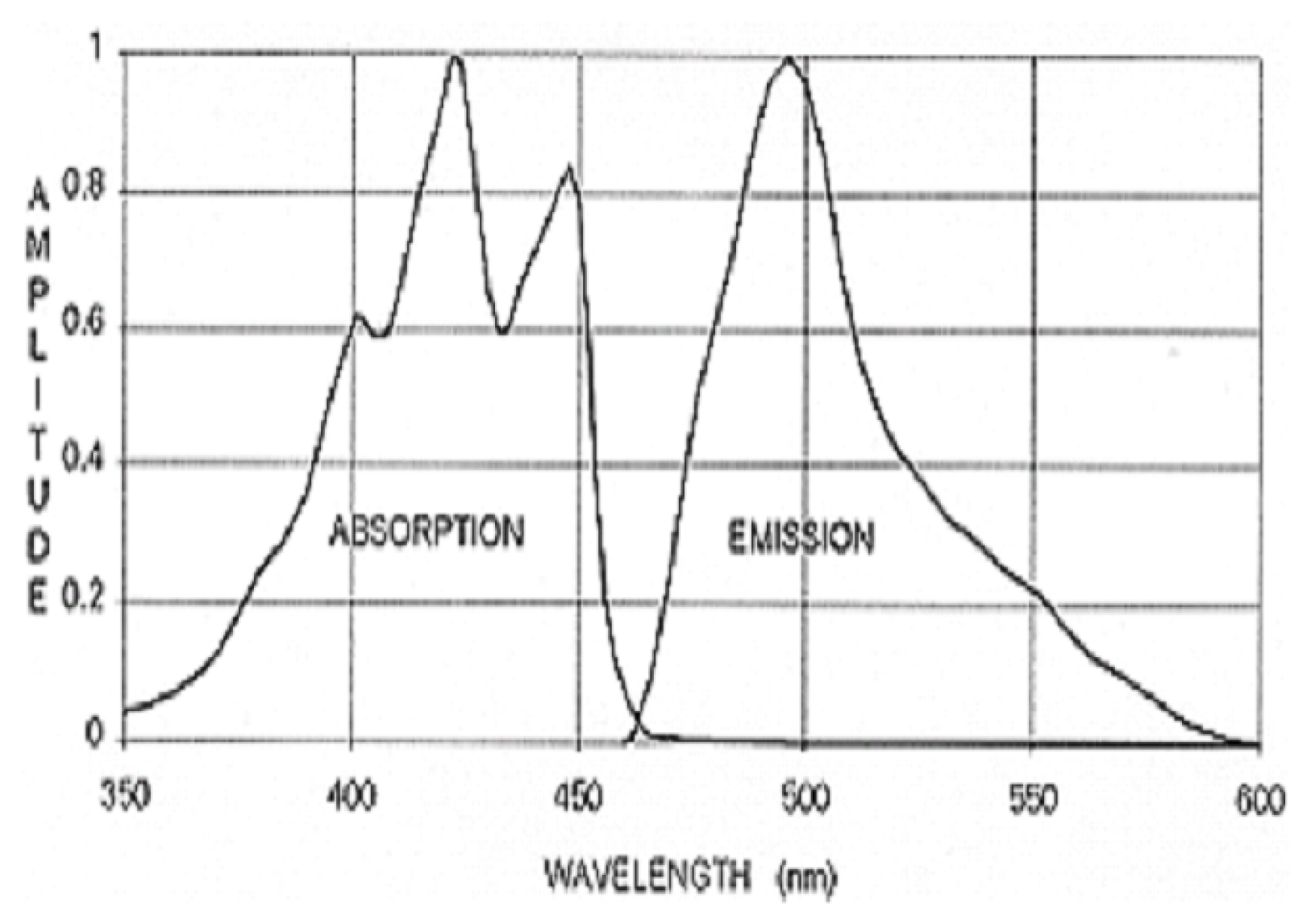

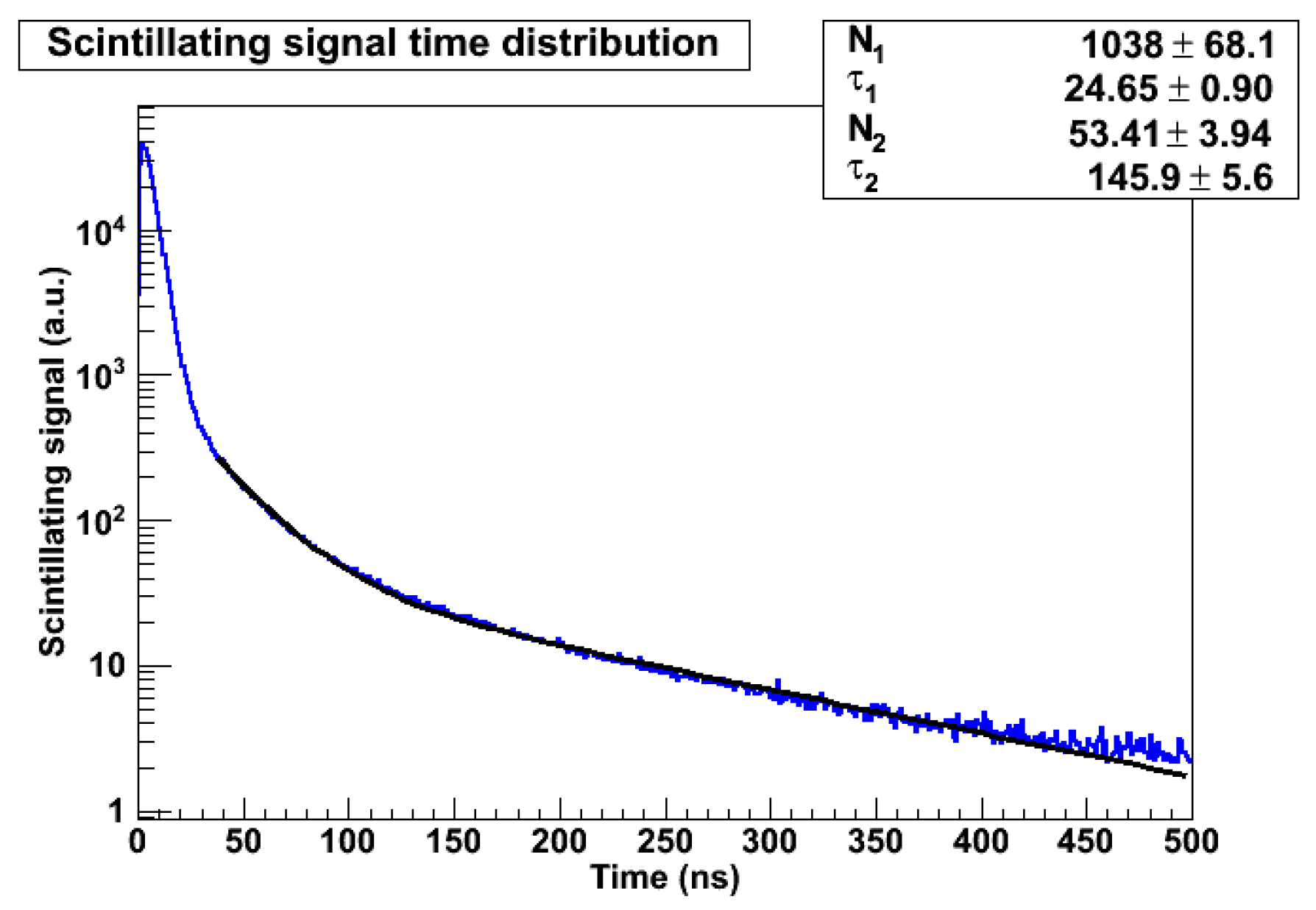

- Scintillation and Äerenkovlight yield need to be at least 150 pe/GeV, namely a factor compared to the equivalent intrinsic nuclear fluctuation (see above) . In the case of Äerenkovsignal, this could be easily obtained with materials with refractive index greater than 1.8. The scintillation light is generated in plastic plates or fibers with volume sufficiently large to yield the required number of photo-electrons. As explained in Section 3.1, this choice will also make the detector sensitive to neutrons and, with a proper front-end electronics, it would allow it to operate in triple-readout mode.

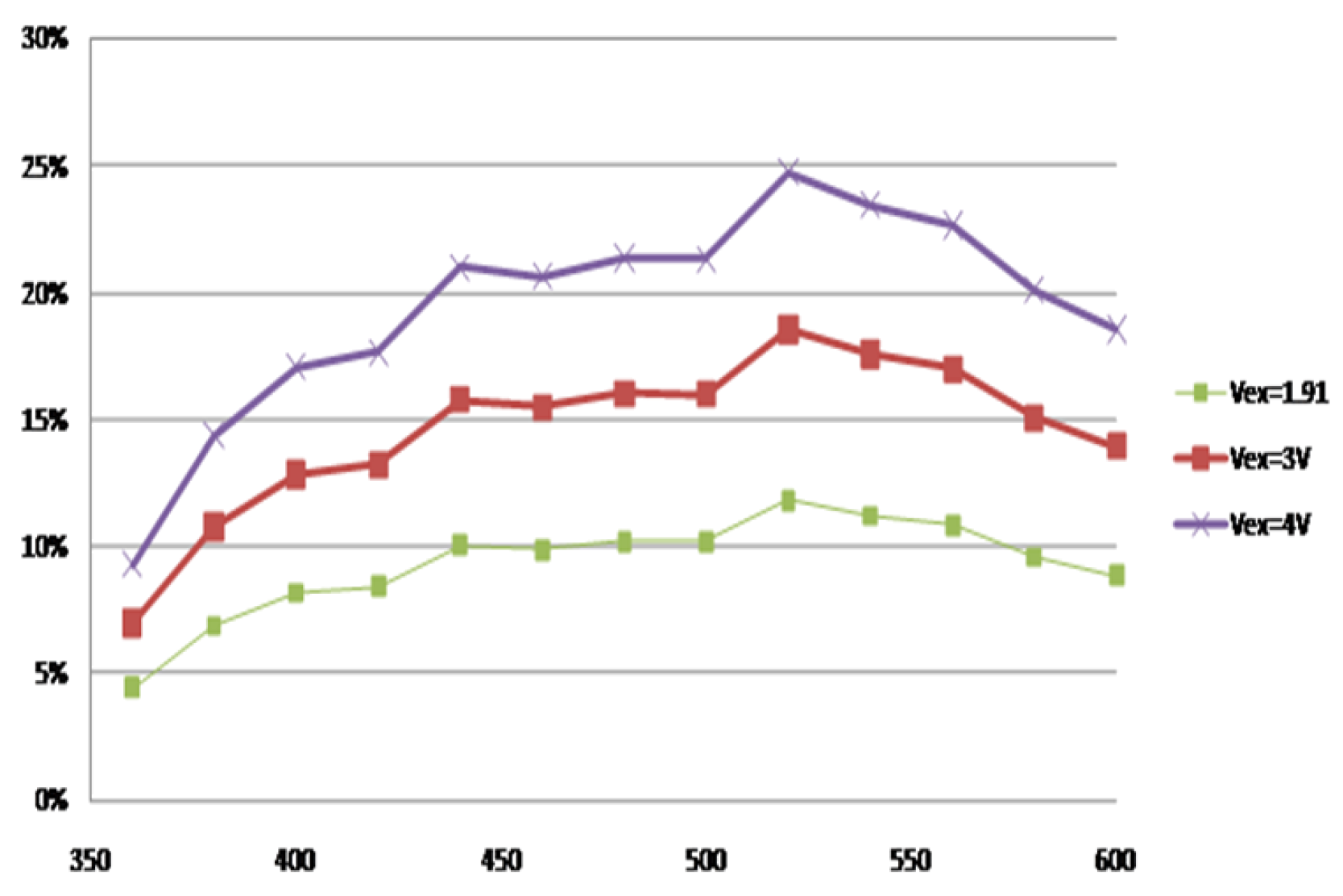

- In order to improve the compensating power of , ratio must be maximized (discussed in Section 2.3). This is most effectively obtained by increasing as much as possible, since, in plastic scintillators, has a narrow range of variation around values of the order of unity. On the other hand, can be easily increased by suppressing the collection of light generated by charged pions with an appropriate choice of the refractive index of the absorber and the critical angle of the light collection system. This mechanism will be discussed in details in the next Section.

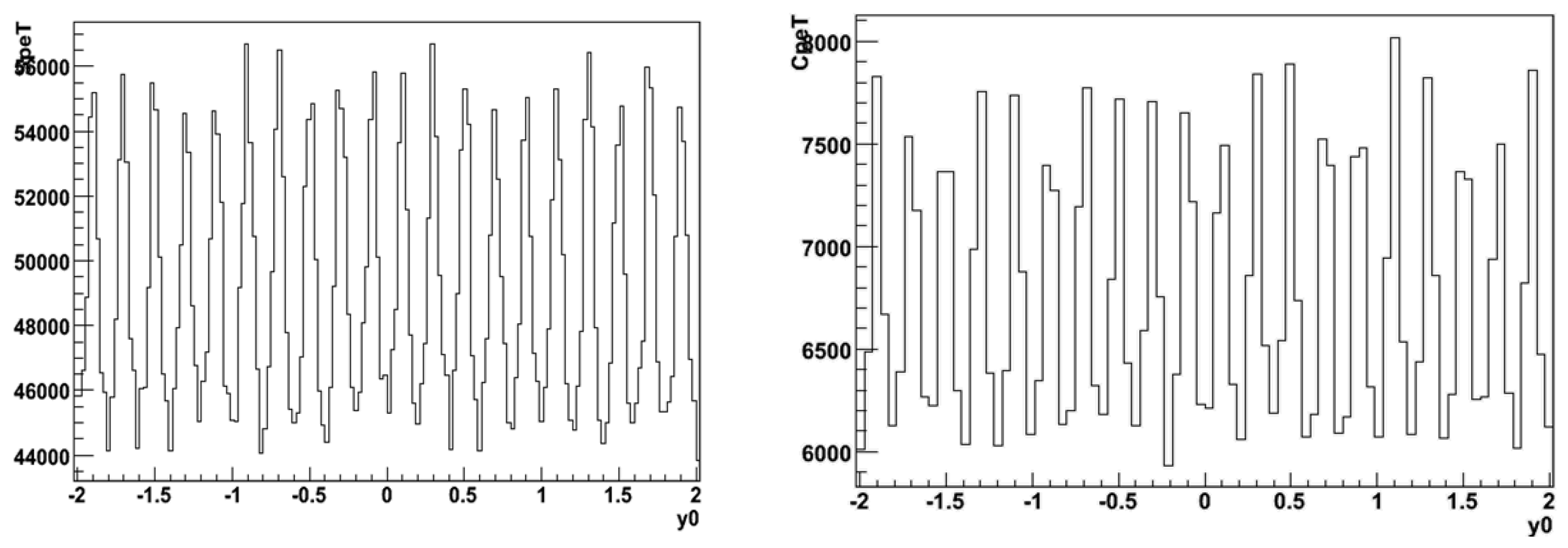

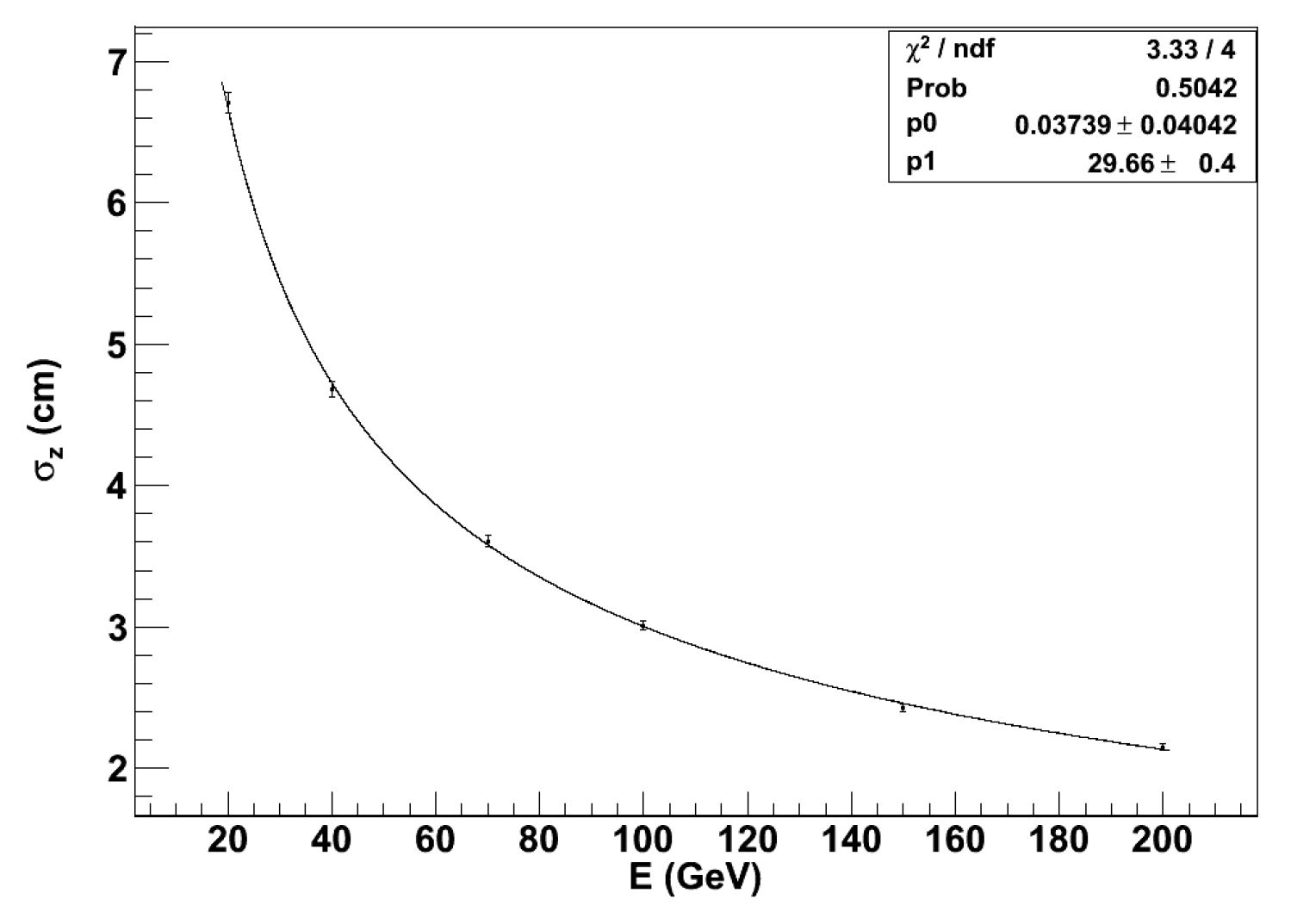

- The calorimeter is designed to be not longitudinally segmented, leading to a 2-D device. The rational behind is that, while a segmented calorimeter provides extra longitudinal information on the shower profile, it also spoils the homogeneity of the calorimeter as it requires extraneous materials (such as sensors, electronics, cables, etc.) in the inner volume of the detector. On the other hand, we can apply for a correction mechanism for shower leakage based on estimating the Center of Gravity () of the shower by a light division method (see Section 7.3 below). A non-segmented calorimeter has a much lower cost of a segmented version. The number of readout channels is much lower with a consequent easier calibration. Construction is also greatly simplified. A non-segmented calorimeter, built using modular, projective towers, is a convenient choice for experiments at colliding beam where showers are predominantly generated by jets. A High-Granularity implementation of is also under study, in either dual-readout and triple-readout configuration. See, for example, Ref. [22,23] and references therein.

- The last requirement is related to the total surface of photo-detector needed to instrument a realistic calorimeter for an experiment at a collider. It becomes impractical (and expensive) to build a detector where the ratio between the active surface of all photo-detector and the total detector surface exceeds few percent. This is especially relevant when the light collection system of such detector is based on optical fibers, as they have to be grouped in separate bunches and routed to their respective photo-detectors. This usually requires that the fibers extend several tens of cm beyond the end of the calorimeter, increasing the complexity of coupling them to the photo-detector. Our goal for the calorimeter is to keep smaller than 10%. For comparison, we have estimated a value of about 21% for the calorimeter proposed by the Collaboration[13] and about 24% for DREAM prototype[9].

4.1. Detector Layout

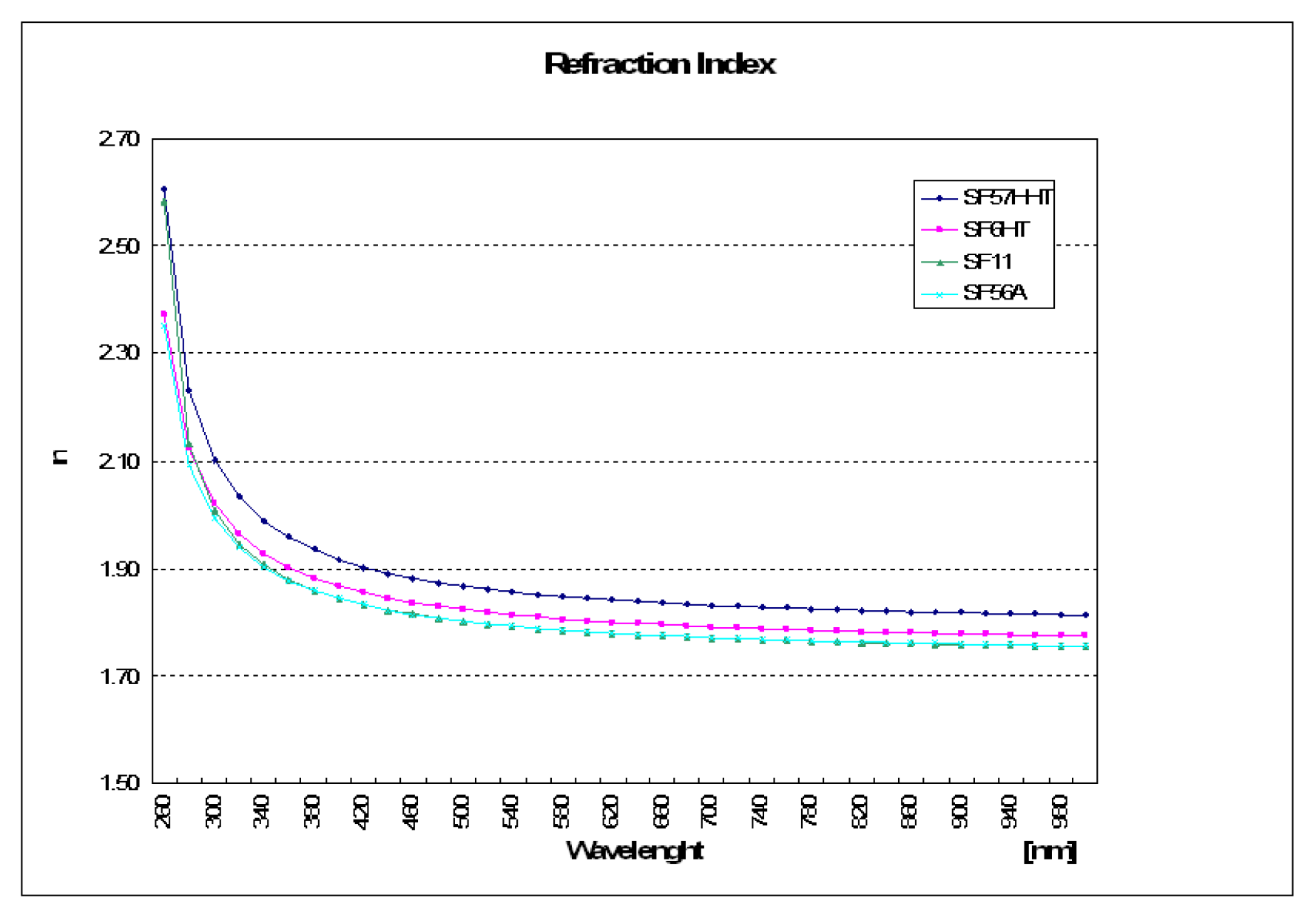

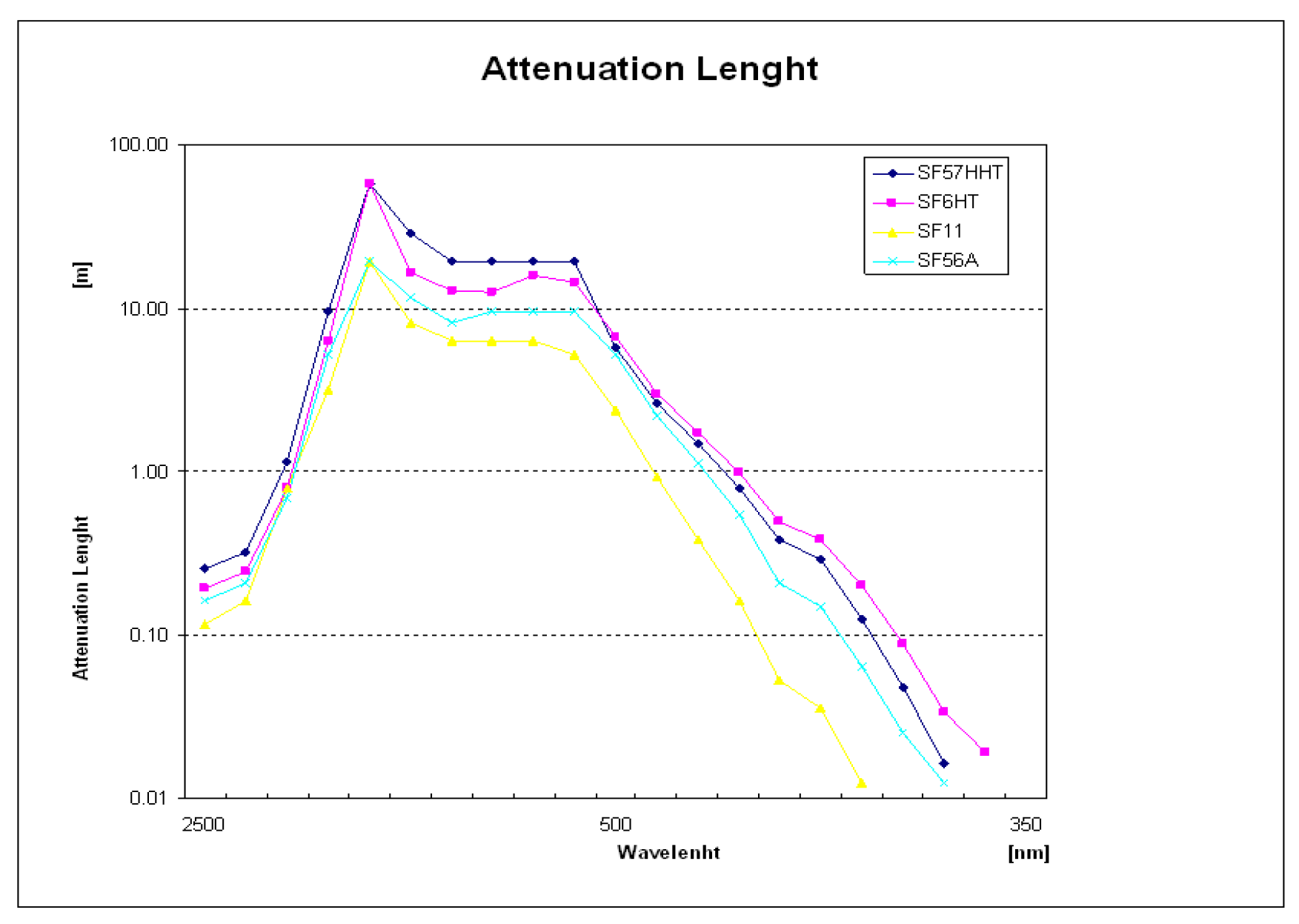

- SF57HHT is a heavy lead glass with a radiation length of about and a Moliére radius of about . In the HEP community the lead glass is often used as active medium of homogeneous electromagnetic calorimeters because of its excellent energy resolution and relatively low costs. This imply that it is also well suited for measuring the electromagnetic component of an hadronic shower.

- The hadronic interaction length of SF57HHT glass is about bringing to a compact longitudinal module and and a detector with fine lateral granularity.

- The SF57HHT glass is produced using a continuous melting technique. Therefore, long slabs up to a few meters in length can easily be obtained for the construction of cells.

- The Äerenkovlight production mechanism depends only on the refractive index of the medium, which is insensitive to changes in ambient parameters. As opposite to crystals, the light yield is also far more insensitive to inhomogeneities, impurities or defects of the medium. As a consequence, manufacturing of lead glass cells is a much more reproducible process than that of crystals;

- The SF57HHT is a glass produced for the optical industries. Therefore, it is a highly transparent medium and, even more important, optically homogeneous. The latter property guarantee than non-uniformity in the light transmission are very low, with corresponding lower contributions to the constant term of the energy resolution function.

- Lead glass is among the cheapest active media available for a calorimeter.

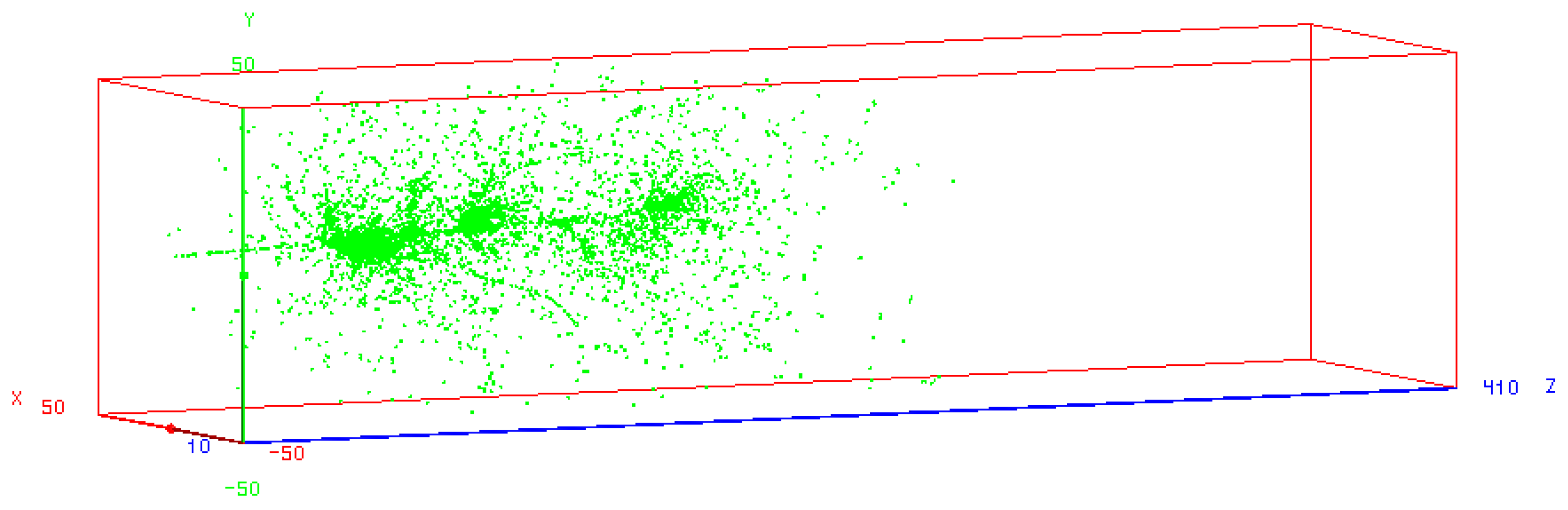

5. Monte Carlo Simulation of an Calorimeter

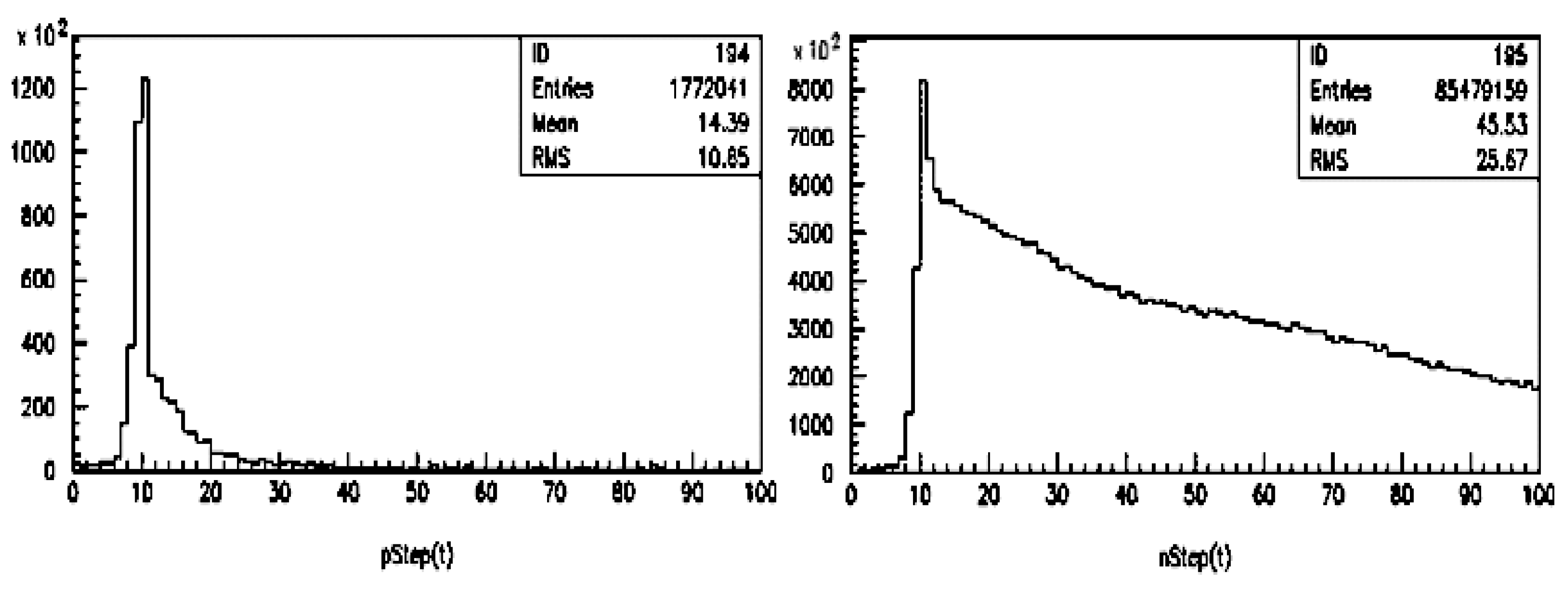

5.1. Monte Carlo Simulation Tools

5.2. Detector Geometry

5.3. Simulation of Detector Response

- Excess Noise Factor (ENF): An ENF of F=1.106 was considered in the simulation of the photodetector. Due to the statistical nature of the multiplication process in a SiPM, a non-negligible ENF induces additional fluctuations in the measured signal, contributing to the stochastic term of the energy resolution function. Although this contribution is very small in ADRIANO due to the large number of primary photoelectrons (estimated to be less than 1% at 40 GeV), the ENF could be relevant in the light division mechanism used for correcting shower leakage (see Section 7.3).

- Non-Uniformity of Scintillating Fiber Response: A non-uniformity of 0.6% was considered for the scintillating fiber response. This parameter value includes contributions from the intrinsic non-uniformity in the production of scintillation light and the non-uniformity in the self-attenuation of the fibers. This figure is derived from measurements performed by the CHORUS Collaboration with a calorimeter prototype employing identical fibers and a layout similar to [5].

- Signal Threshold: A signal threshold of 3 photoelectrons was applied to the simulated electronics response to keep the dark counting rate below 50 kHz.

- Finite Bin Size of ADC: The effect of the finite bin size of a 14-bit ADC was considered when digitizing the front-end electronics (FEE) signals. This effect corresponds to an uncertainty of about 3 photoelectrons, independent of the measured energy. A non-negligible contribution to the constant term of the energy resolution function is expected from this effect.

6. Application of the Dual-Readout Principles to Detector

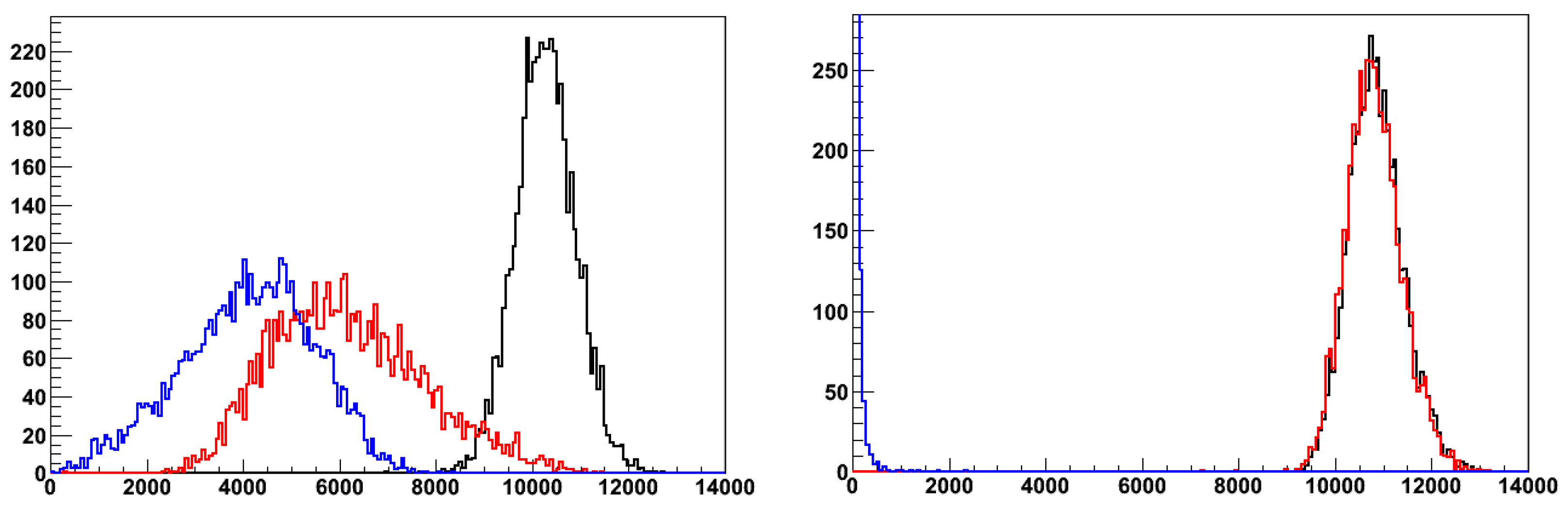

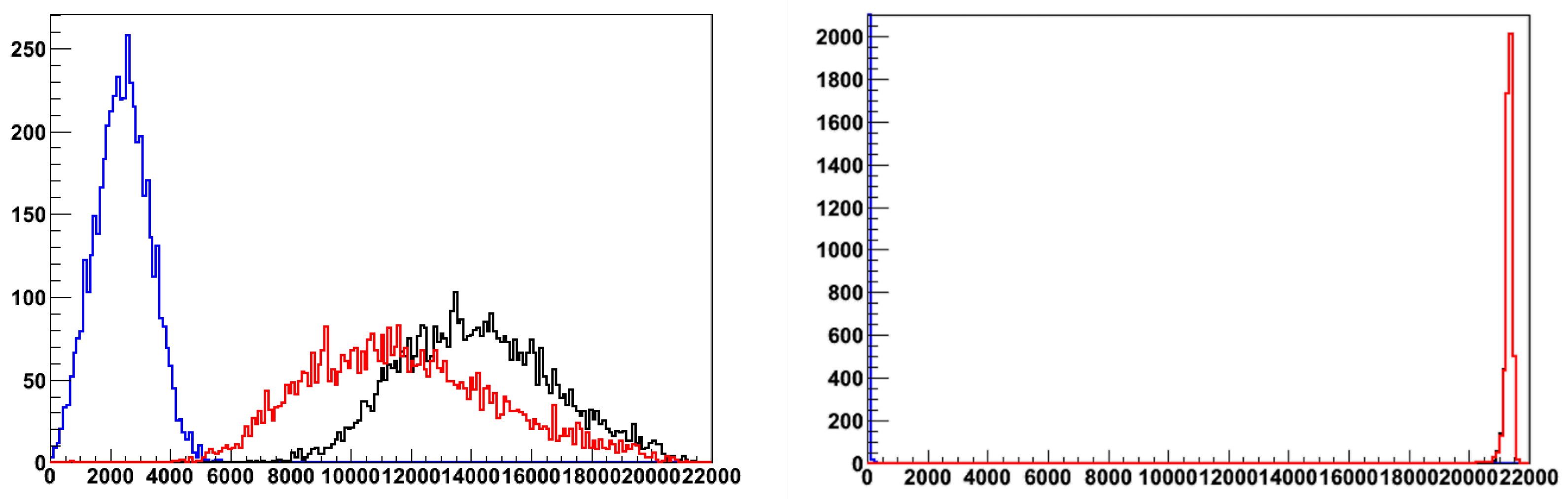

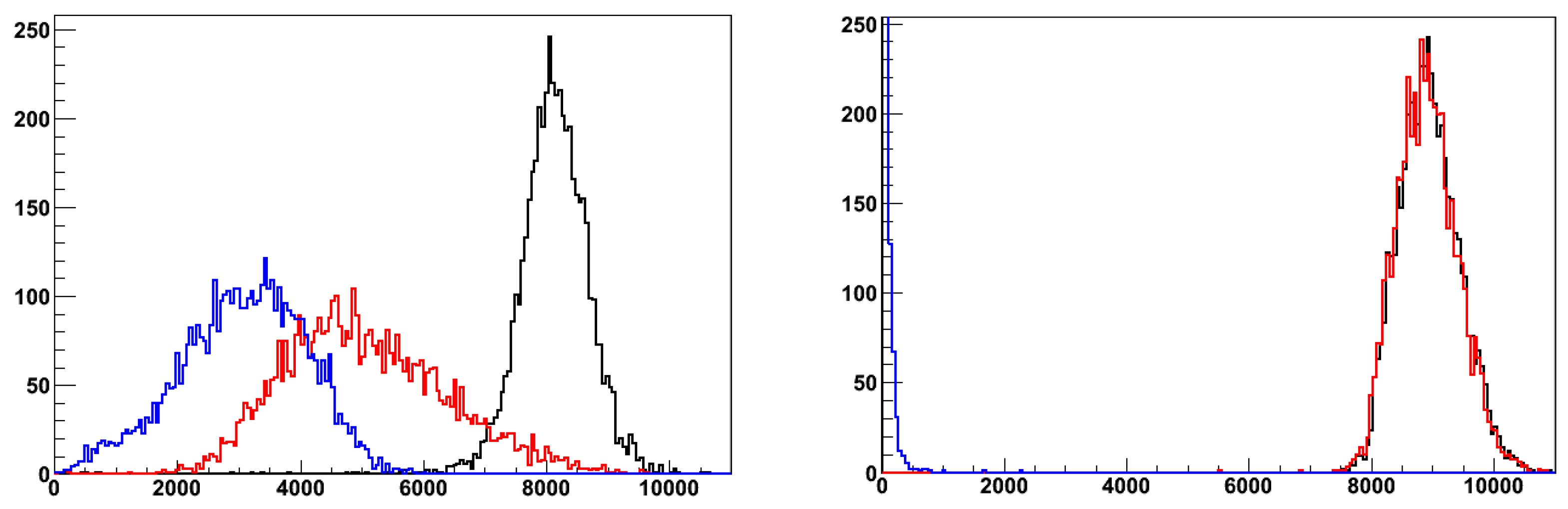

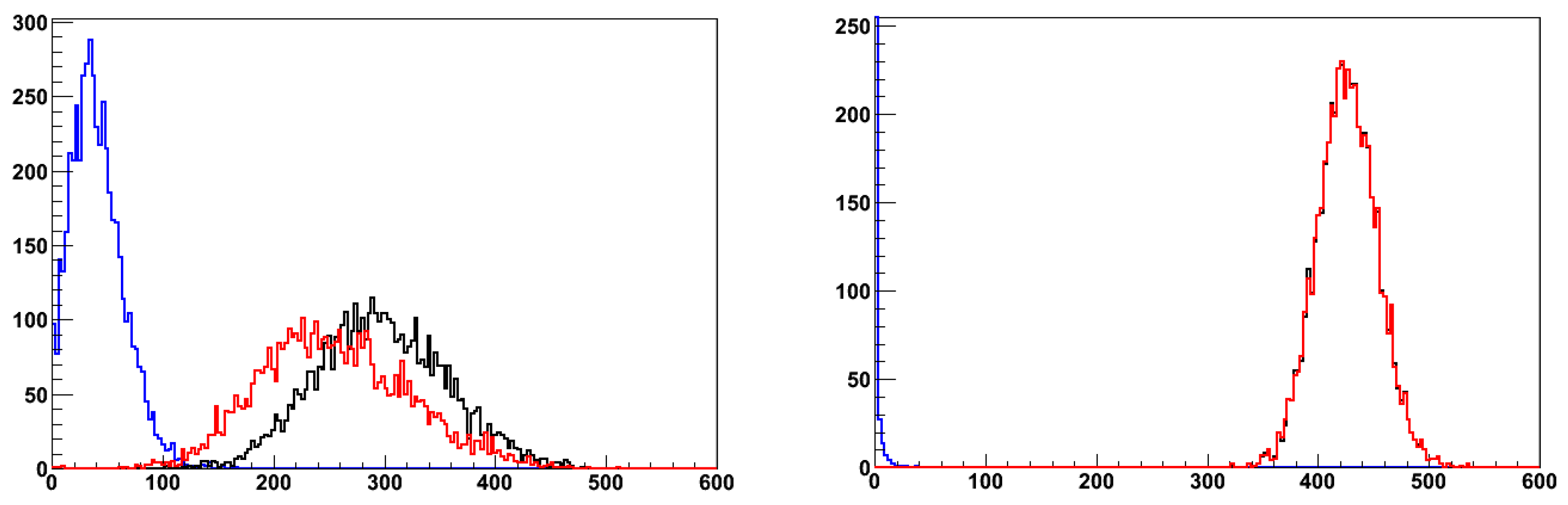

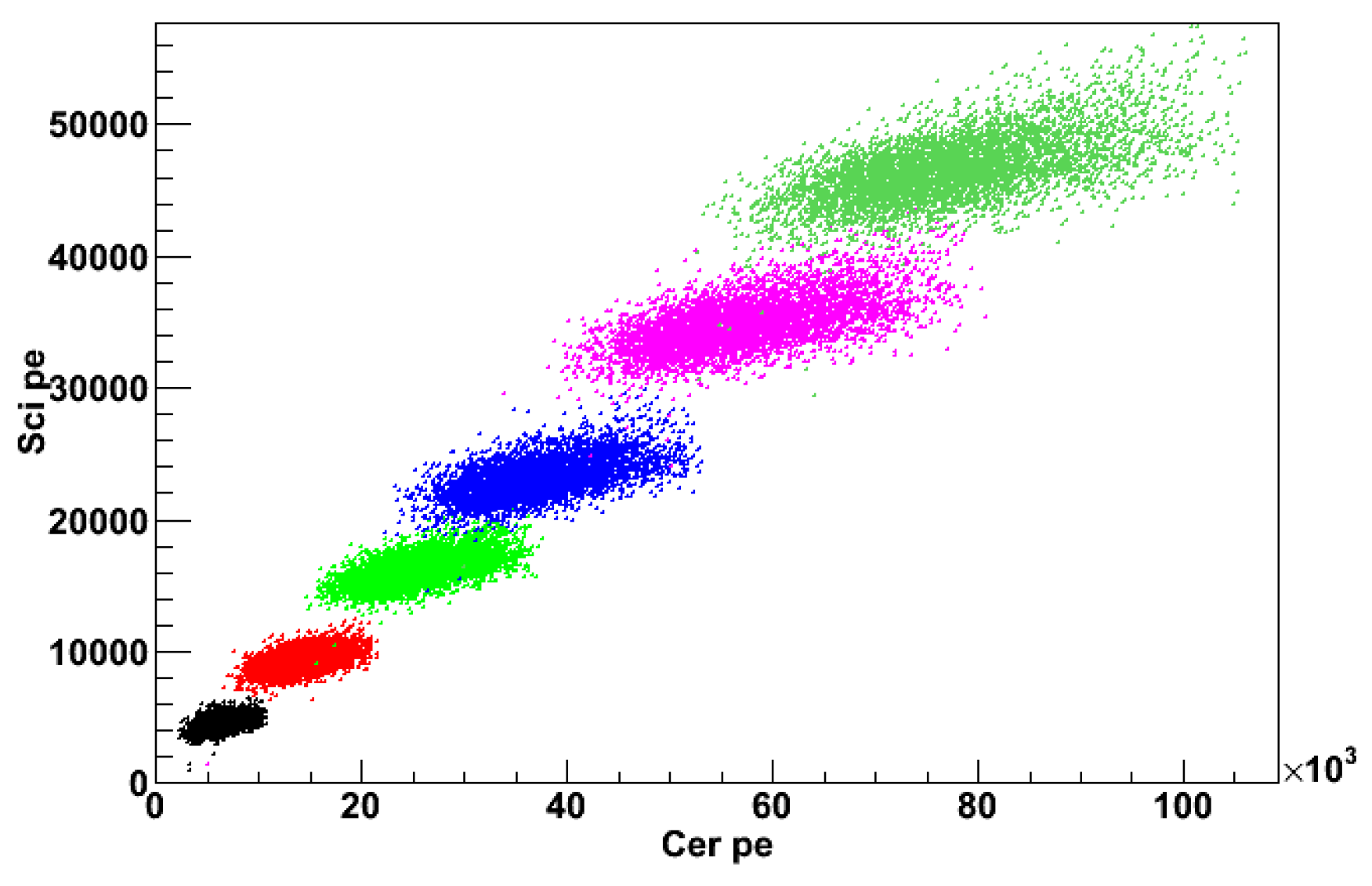

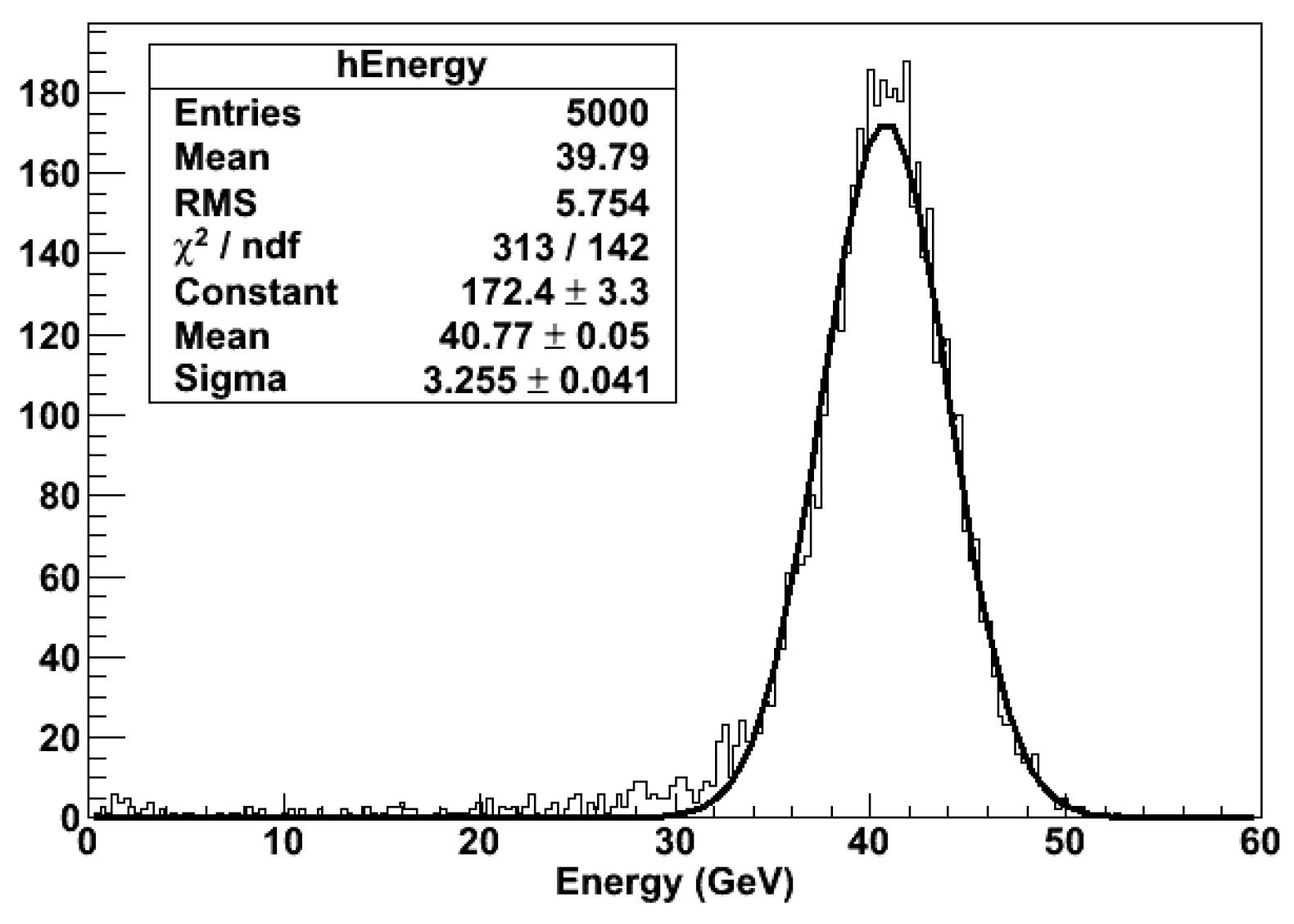

6.1. Raw Detector Response

6.2. Detector Calibration

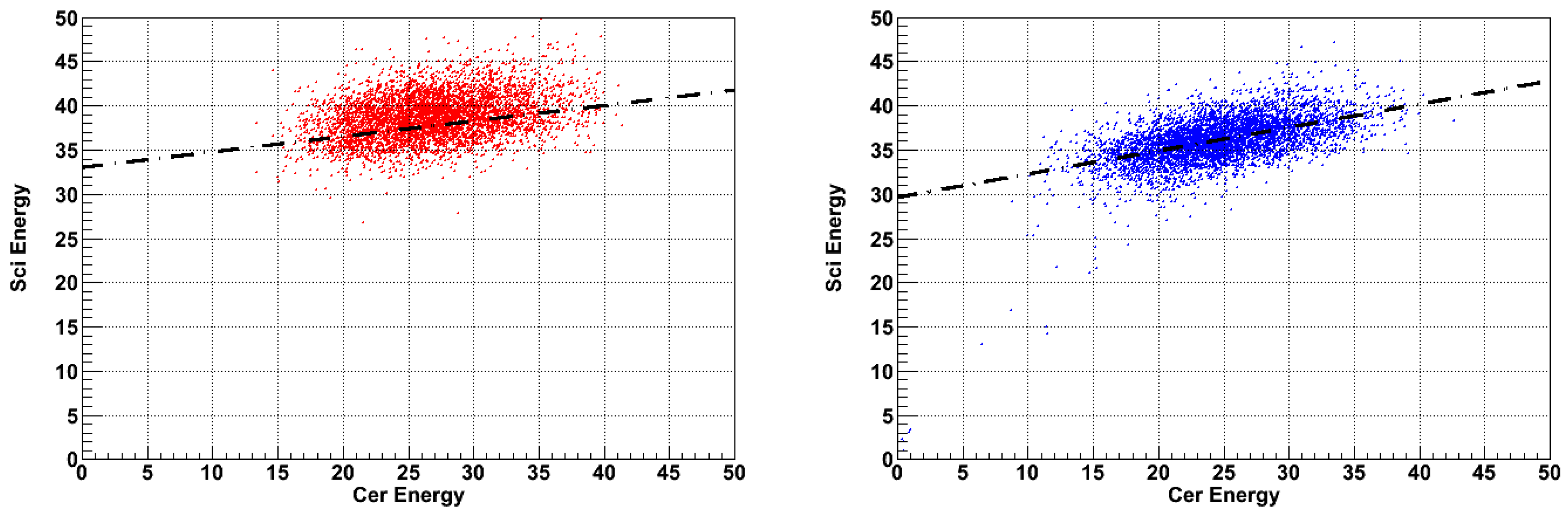

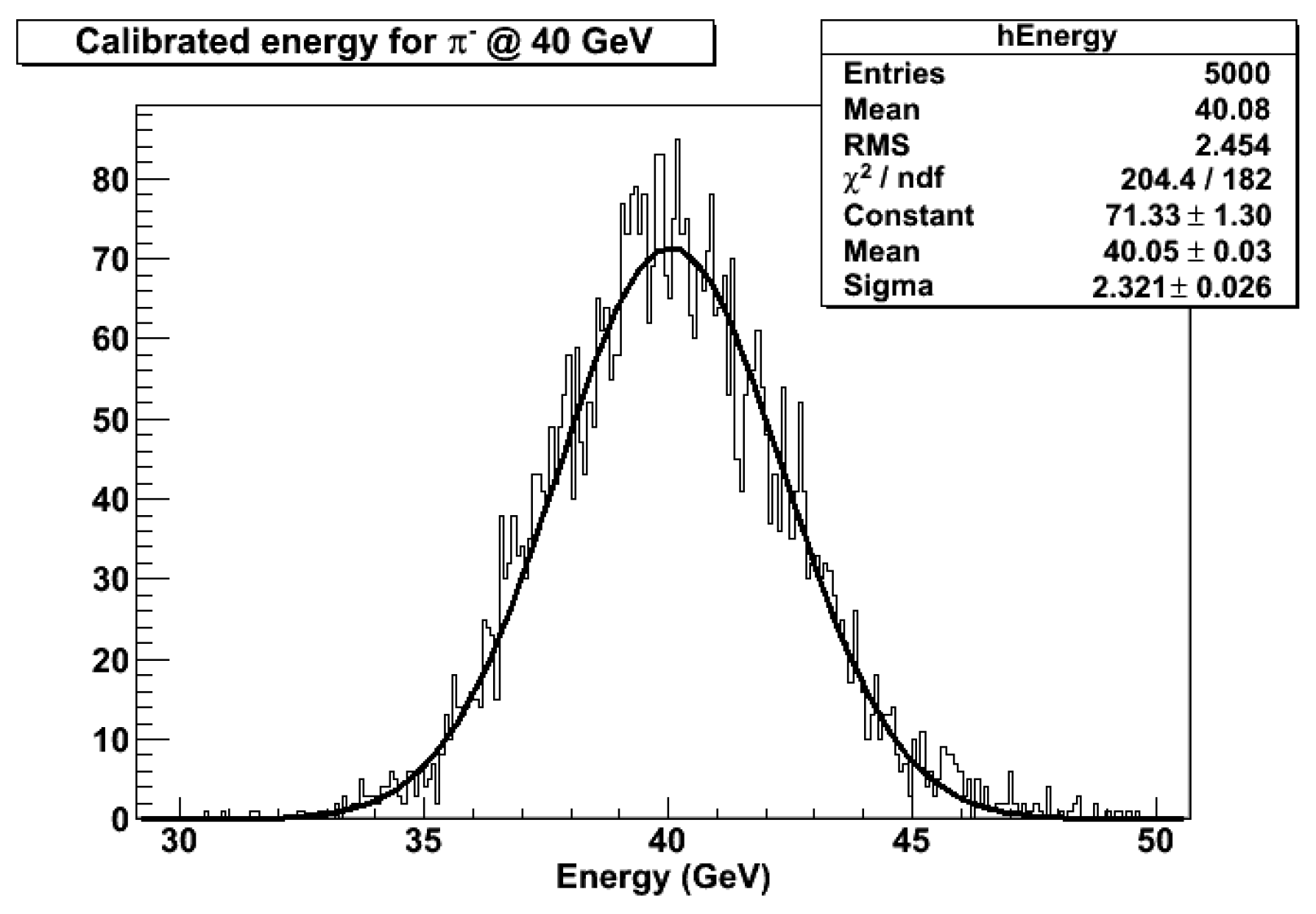

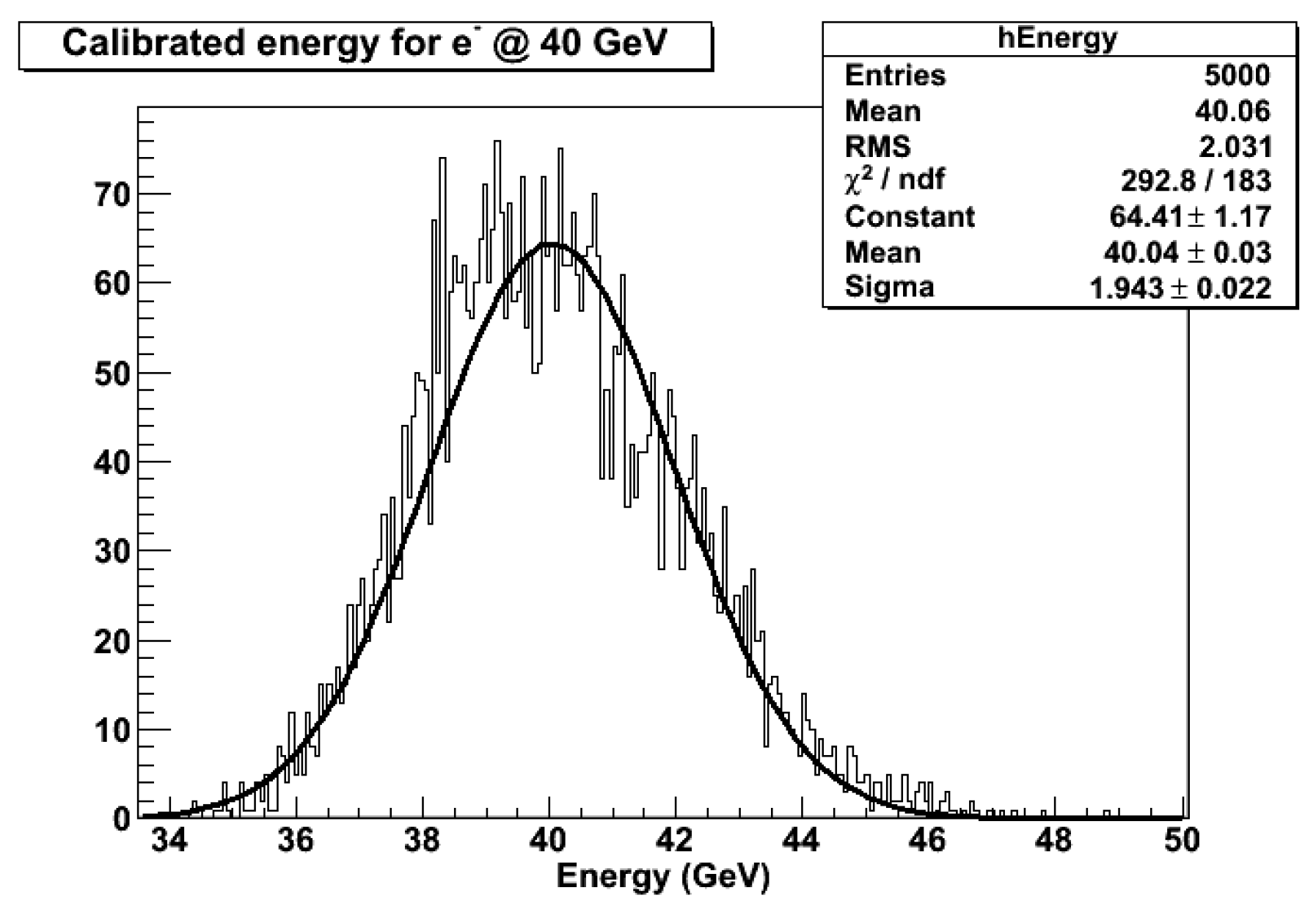

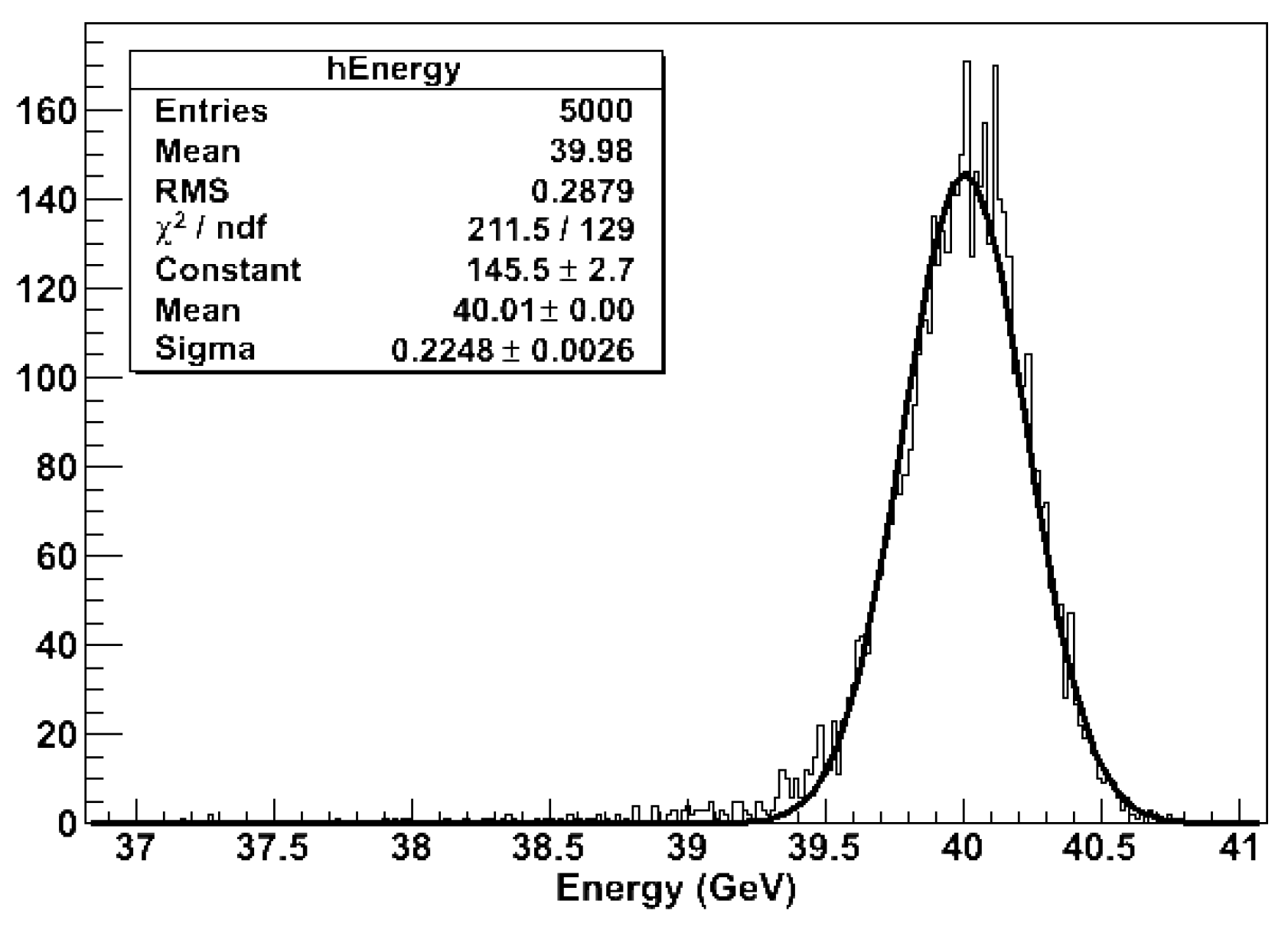

6.3. Detector Calibration with Pion-Only Samples

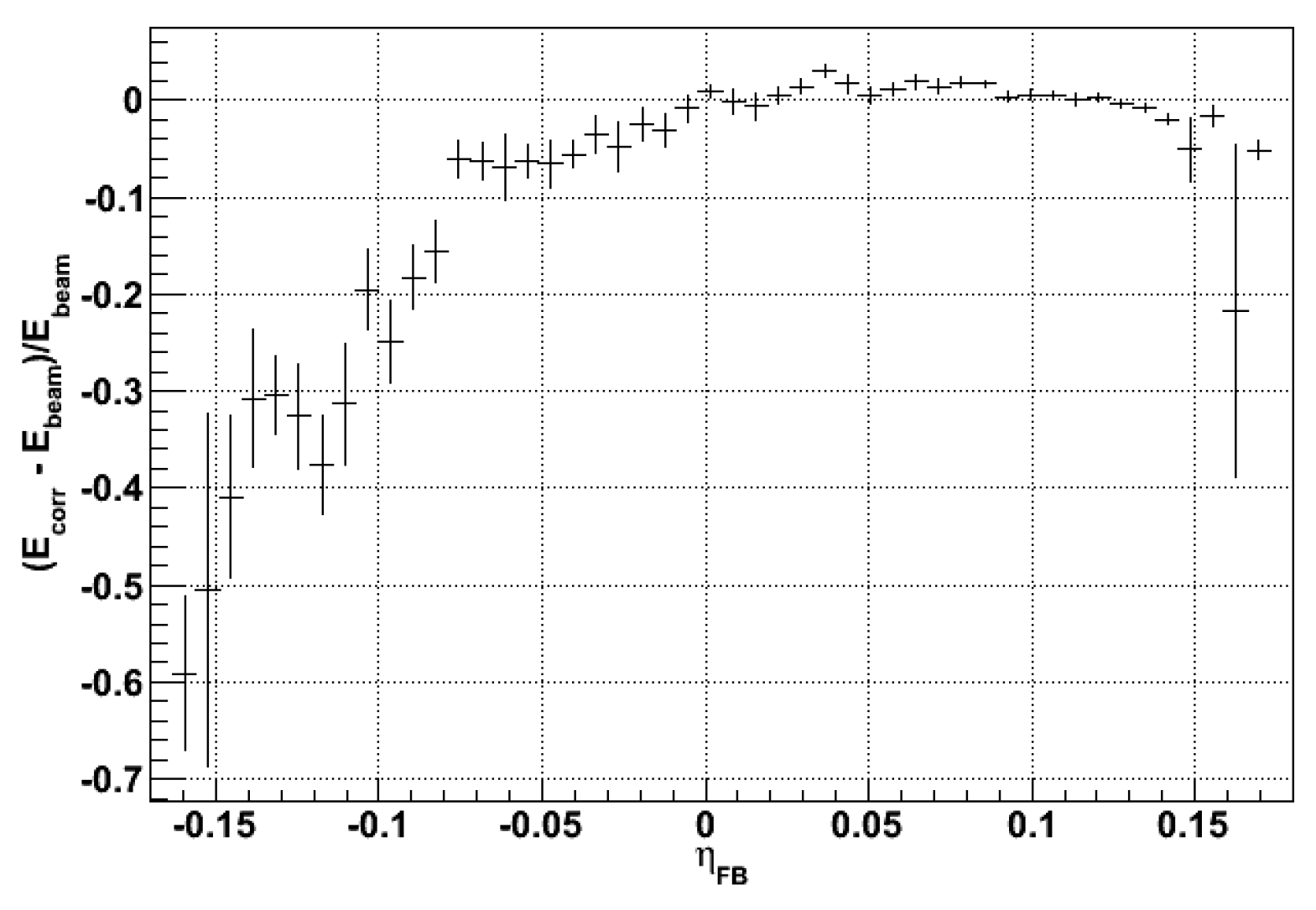

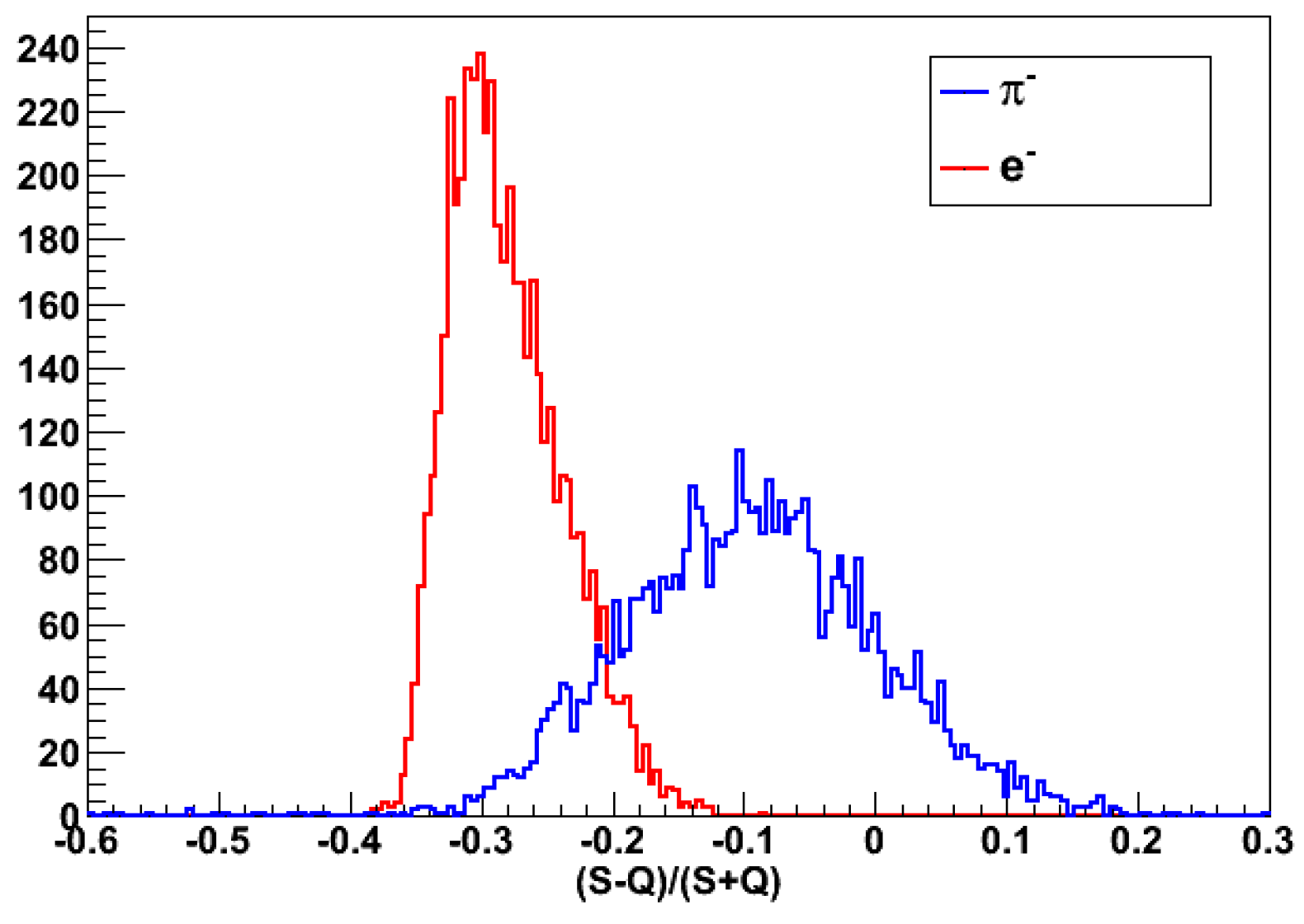

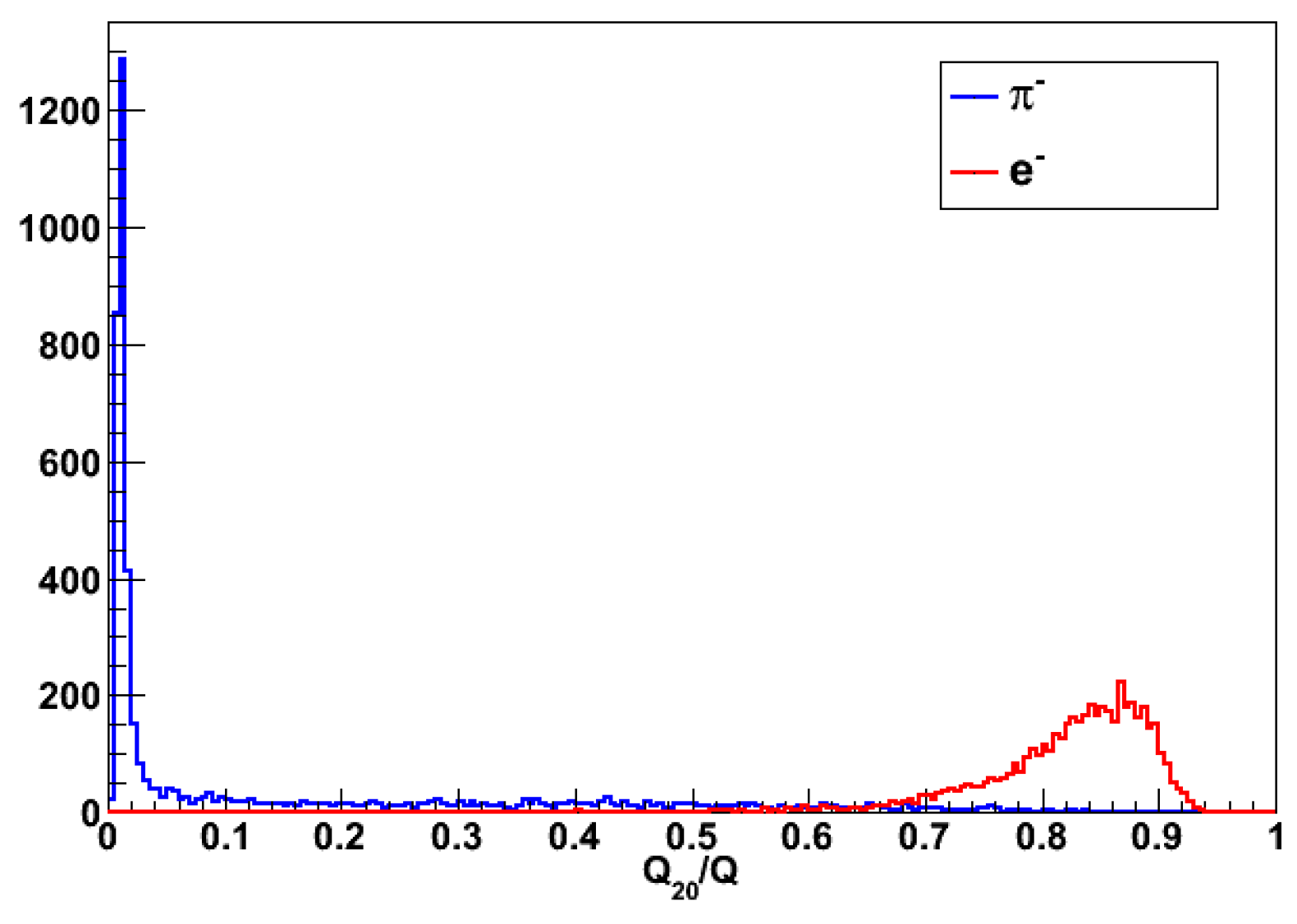

6.4. Energy compensation with dual-readout

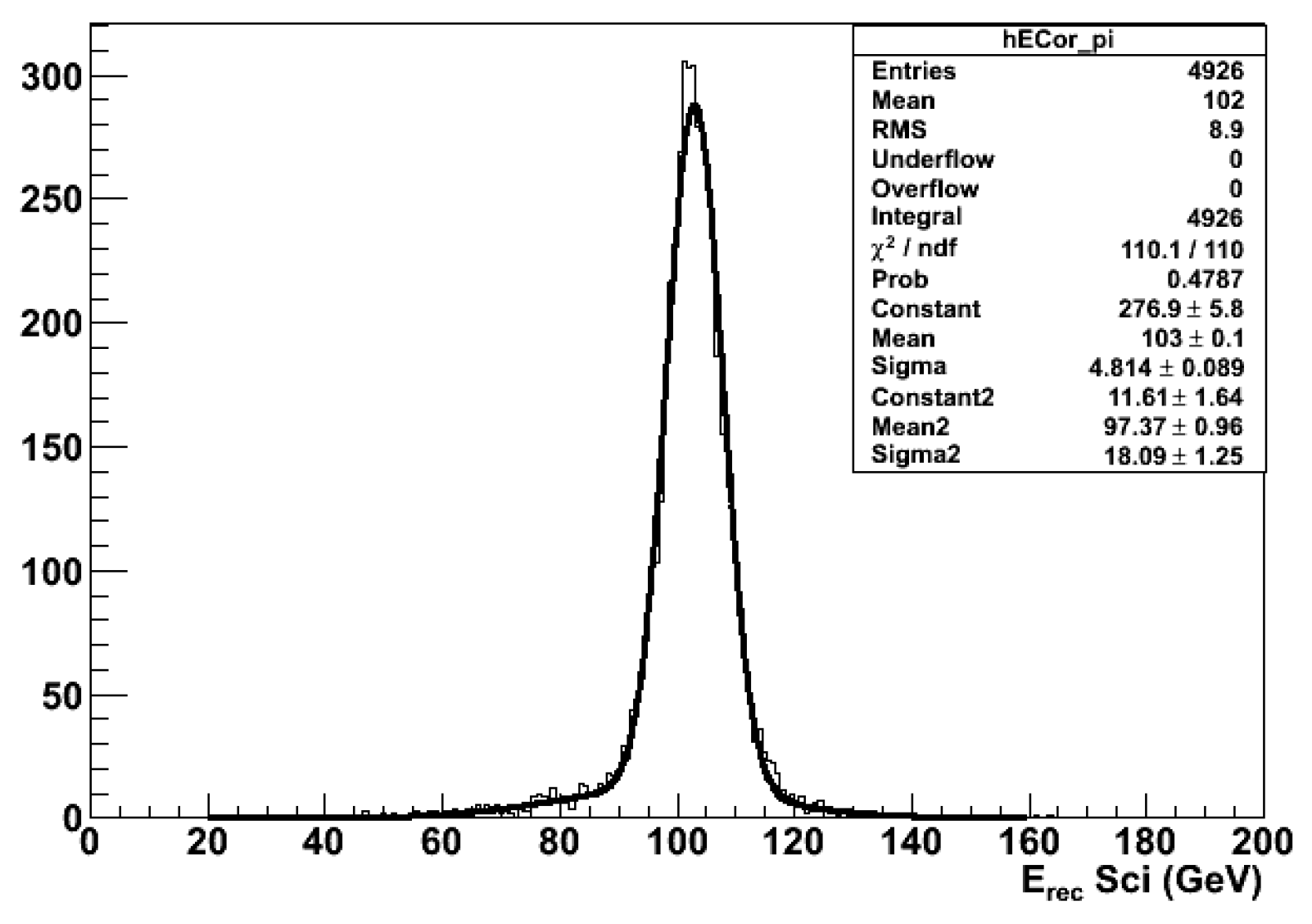

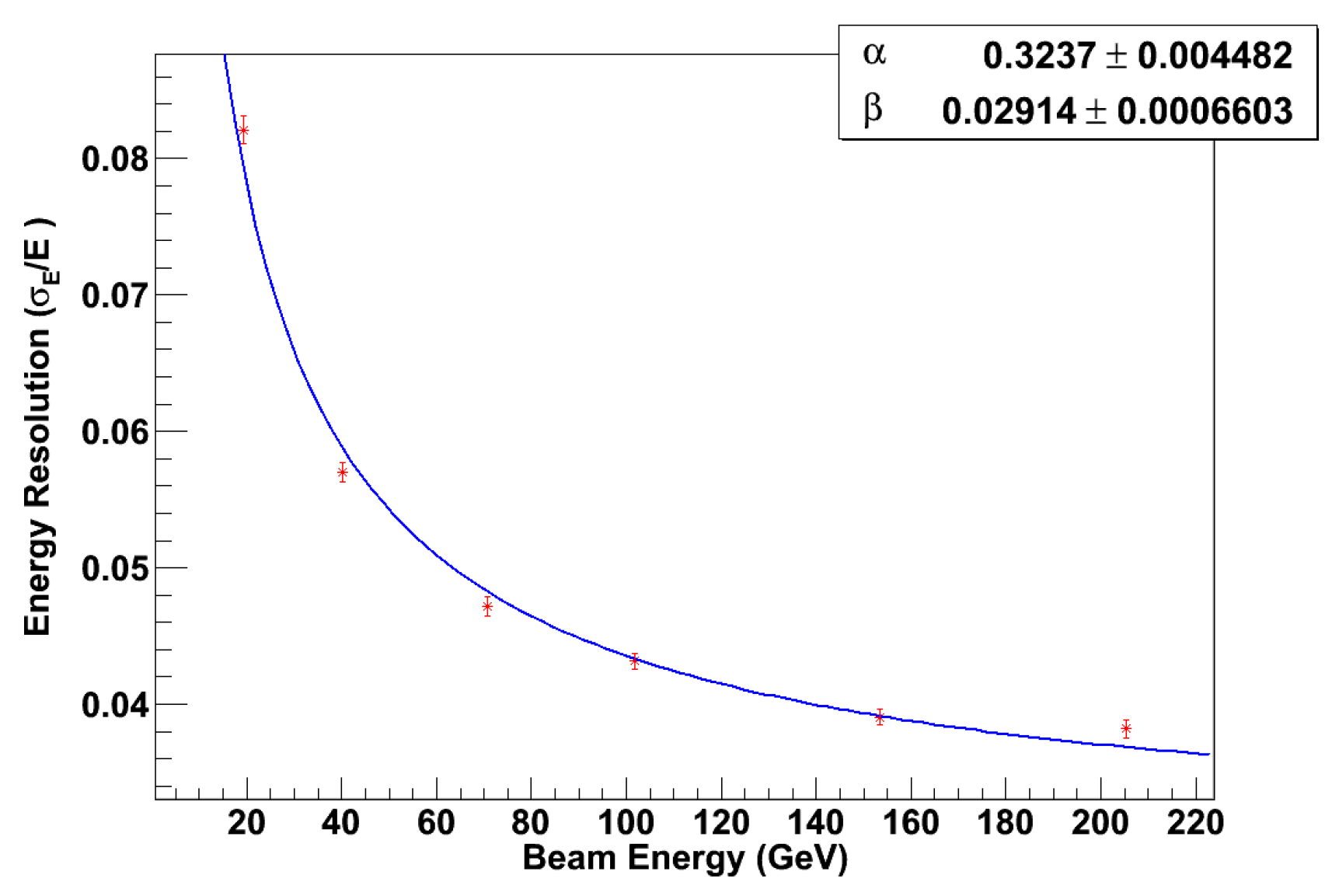

7. Performance of detector

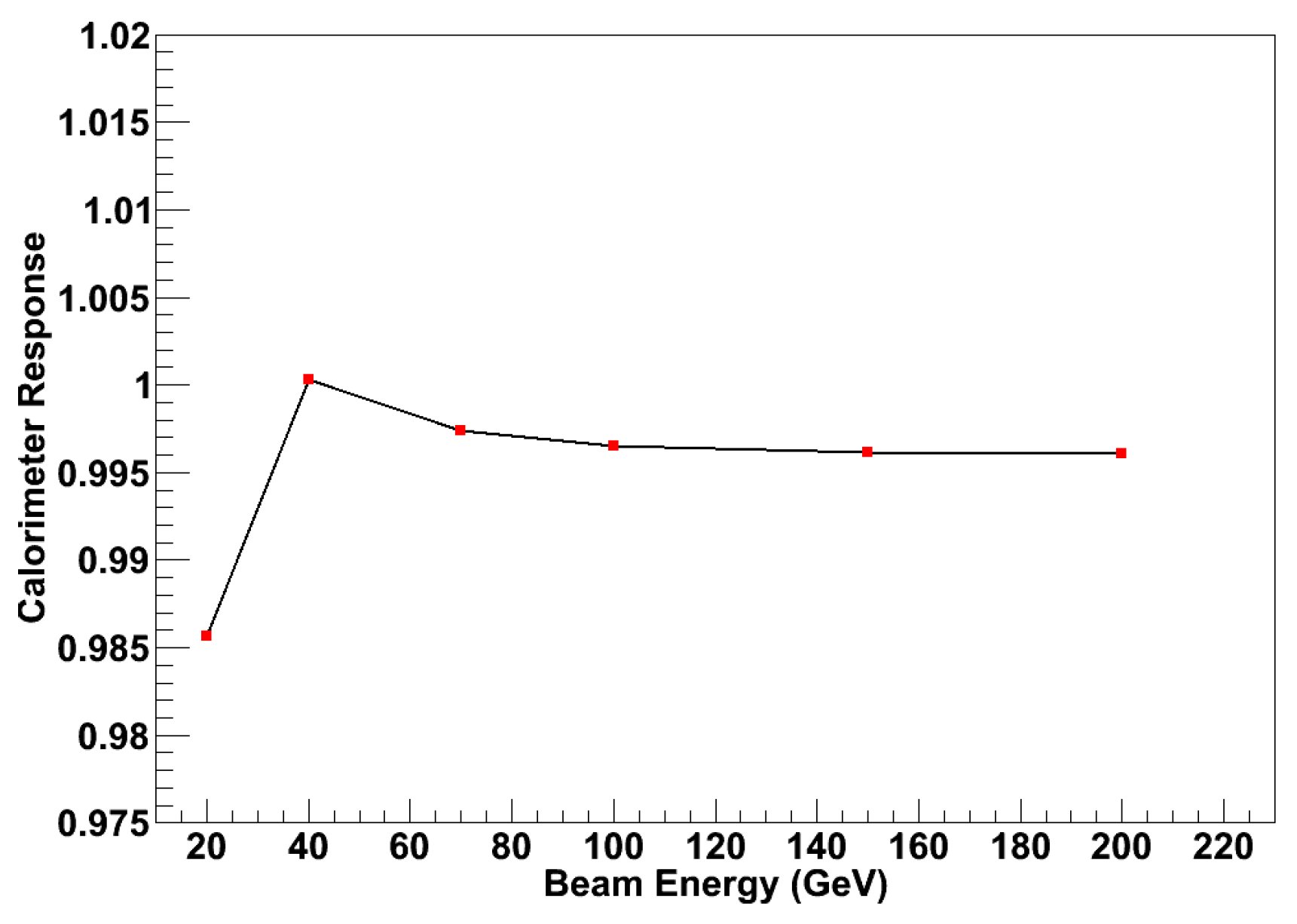

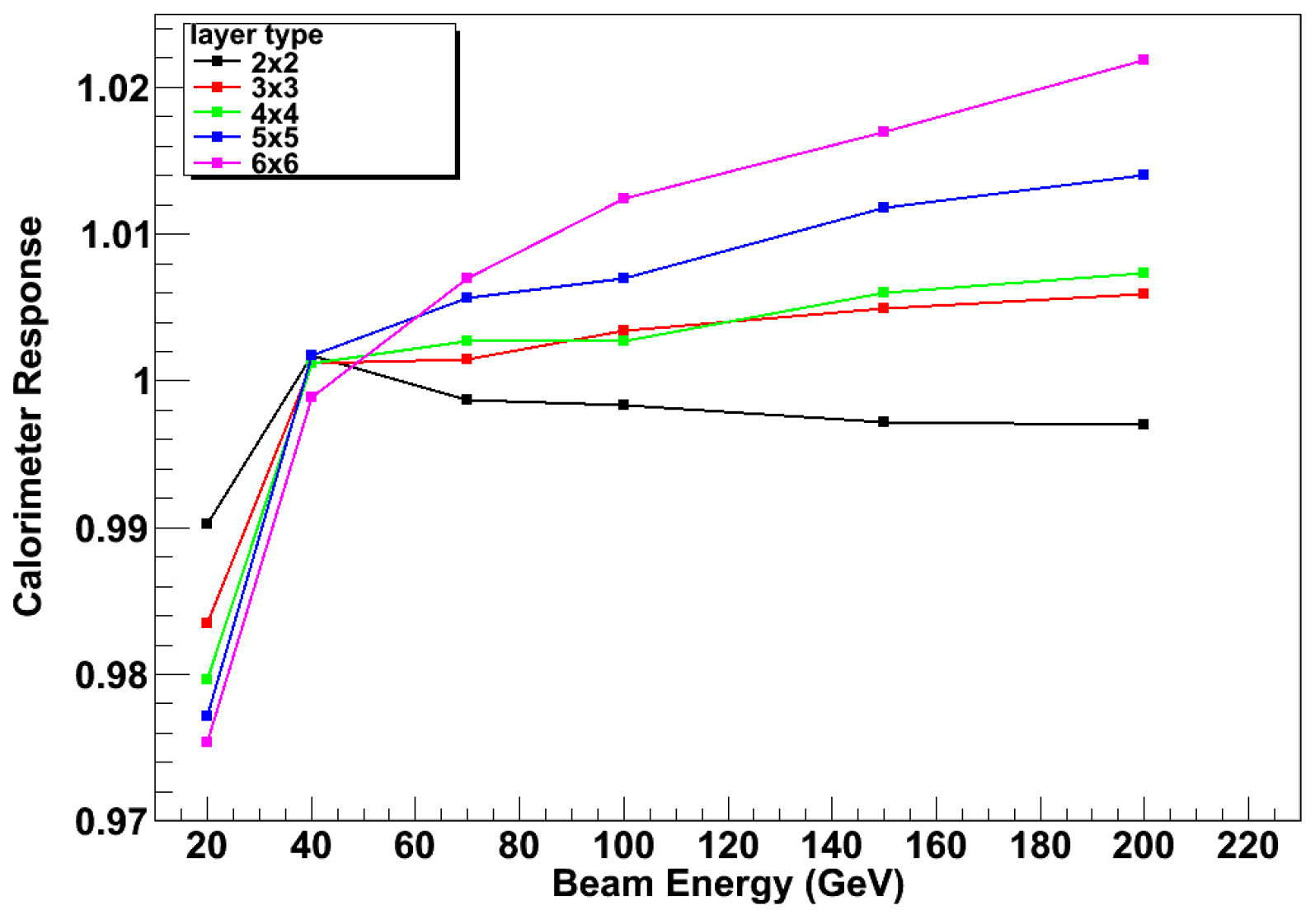

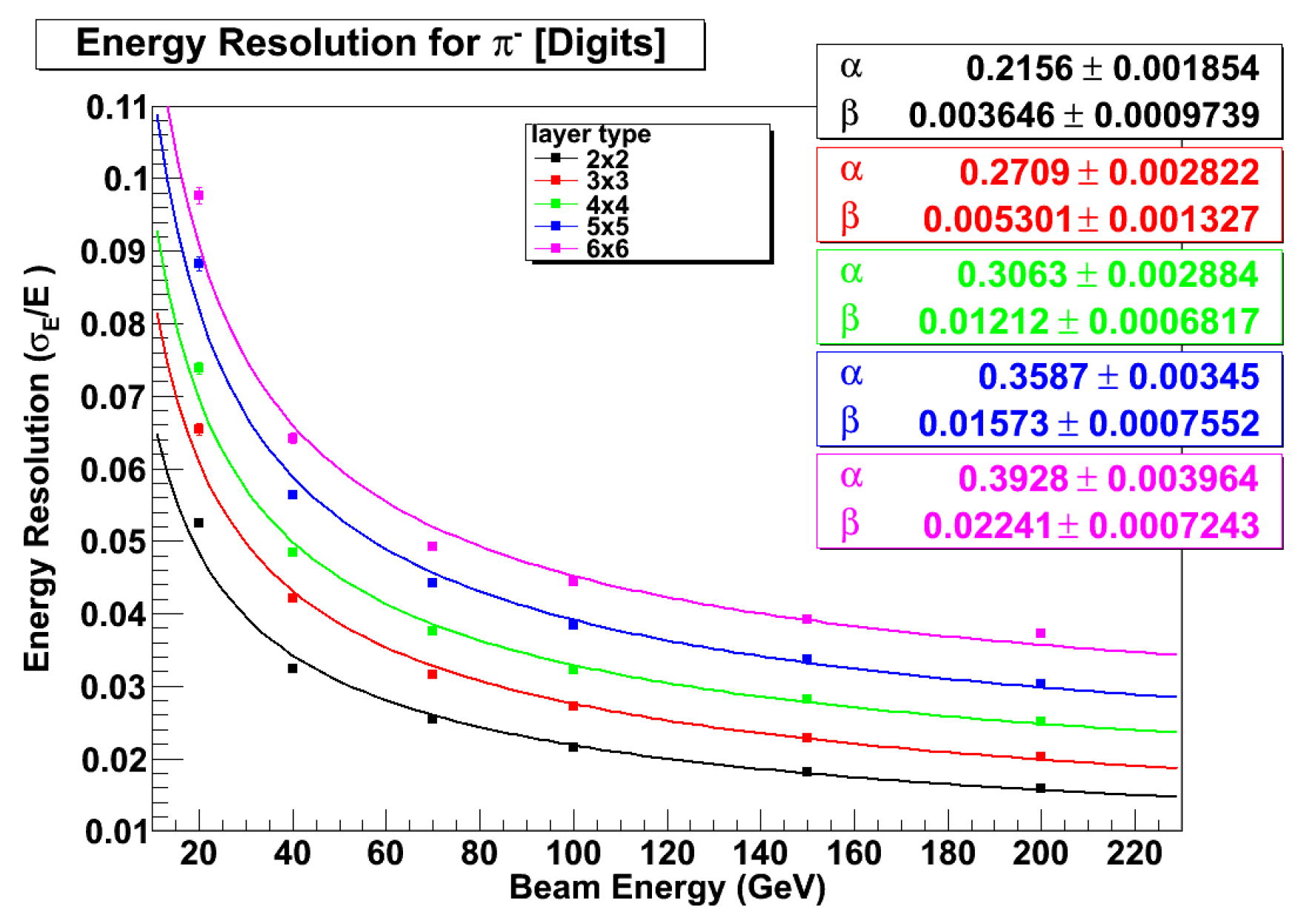

7.1. Performance in Dual-Readout Mode

7.2. Performance in Triple-Readout

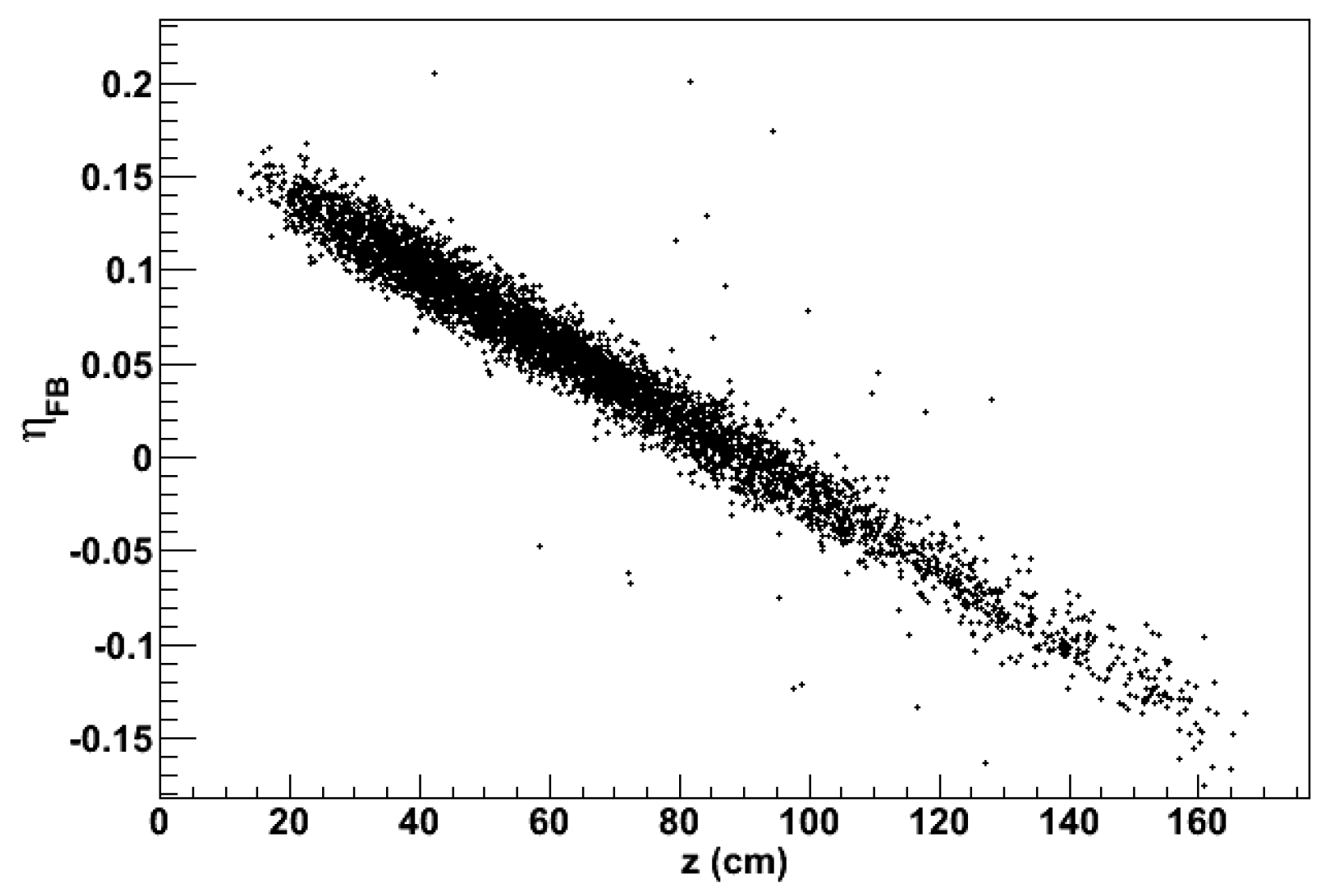

7.3. Effects of leakage

7.4. Performance of a 180 cm long module

- a non-uniformity in the light attenuation process in the fiber equal to 0.8% ;

- a contribution of 0.3% to the fluctuations in the PDE of the photodetector;

- a contribution of 1 photoelectron from electronic noise;

- the finite size of binning of a 14 bits FADC.

7.5. Performance with electrons

- The ratio of the light collected in the foremost of the lead glass and the whole Äerenkov signal;

- The normalized difference of the total scintillating and Äerenkov signal.

8. Discussion of the Results

9. Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgments

| 1 | The quoted authors use, respectively, 1/R and in place of . The reason for the nomenclature introduced in the present article will become clear in Section 2.3. |

| 2 | Most dense and high refractive glasses are reported by their maufacturers to produce a faint fluorescence light when subject to excitation. The lower the purity of the glass, the more intense is such effect. In the following, we will disregard this effect and assume that only Äerenkovlight is produced. |

| 3 | Eq. 8, derived from the known relations for the capture of a photon striking a WLS fiber of diameter d in a square cell of length w and average wall reflectivity R, is expressed as: . |

| 4 |

References

- ILC Reference Design Report, 2007.

- S. Eno et.al., Dual-Readout Calorimetry for Future Experiments Probing Fundamental Physics.(2022) https://arxiv.org/ abs/2203.04312. [CrossRef]

- B. Fleming, I. B. Fleming, I. Shipsey, et.al., Basic Research Needs for High Energy Physics Detector Research & Development: Report of the Office of Science Workshop on Basic Research Needs for HEP Detector Research and Development: -14, 2019 (2019). 11 December. [CrossRef]

- R. Poschl, Recent results of the technological prototypes of the CALICE highly granular calorimeters, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 958 (2020) 162234, proceedings of the Vienna Conference on Instrumentation 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Buontempo et al., “Construction and test of calorimeter modules for the CHORUS experiment”, Nucl. Instr. and Meth. A 349 (1994), p. 250. [CrossRef]

- https://journals.aps.org/rmp/abstract/10.1103/RevModPhys.90.025002, section on calorimetry).

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/016890029190062U?via%3Dihub.

- R. Wigmans, Calorimetry energy measurement in particle physics, in: International Series of Monographs on Physics, vol. 107, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000.

- All DREAM papers are accessible at http://www.phys.ttu.edu/dream, and also http://highenergy.phys.ttu.edu.particle physics, in: International Series of Monographs on Physics, vol. 107, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000.

- https://www.linearcollider.org/ https://clic−study.web.cern.ch/clic−study/.

- D. E. Groom, Energy flow in a hadronic cascade: Application to hadron calorimetry, Nucl. Instr. and Meth. A 572 (2007), p. 633. [CrossRef]

- R.Wigmans,“EnergymeasurementattheTeVscale”,NewJournalofPhysics 10 (2008), 025003.

- 4th Concept Collaboration - Letter of Intent from the Fourth Detector (4th) Collaboration at the International Linear Collider, 2009 also at: http://www.4thconcept.org/4LoI.

- M. Antonelloetal2020JINST15C06015. 6015.

- M.T. Lucchini et al 2022 JINST 17 P06008. [CrossRef]

- I. Pezzotti, et. al. [CrossRef]

- N. Akchurin, et. al, New Crystals for Dual-Readout Calorimetry, Nucl. Instr. Meth. A604(2007)512-526. [CrossRef]

- G. Gaudio 2012 J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 404 012064.

- M.T. Lucchini et al 2020 JINST 15 P11005. [CrossRef]

- R. Instr. Meth. A( 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Dumazert et. al., Gadolinium for neutron detection in current nuclear instrumentation research: A review, Nucl. Instrum. And Meth. A 882, 53, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Gatto et.al, Preliminary Results from ADRIANO2 Test Beams Instruments 6 (2022) 4, 49. [CrossRef]

- B. Bilki, et. The ADRIANO3 Triple-Readout Calorimetric Technique, Submitted to IEEE-2024 conference.

- T. Zhao, et al., A Calorimeter Based on Scintillator and Cherenkov Radiator Plates Readout by SiPMs - A University Program of Accelerator and Detector Research for the International Linear Collider (vol. IV) FY 2006 also at: http://www.hep.uiuc.edu/LCRD/LCRD_UCLC_proposal_FY06/Zhao_UW-FNAL_Calorimeter _Proposal_122705.

- R. Wigmans, “Recent results from the DREAM project”, Journal of Physics: Conference Series 160 (2009) 012018. [CrossRef]

- S. Franchino, “Recent results from the DREAM project”, SocietáItaliana di Fisica - XCIV Congresso Nazionale also at: http://www.pv.infn.it/ franchino/miei_talk/DREAM_Genova.

- K Pauwels et. al, ”Single crystalline LuAG fibers for next generation calorimeters ”, presented at CHEF2013 (2013) also at: https://indico.in2p3.fr/getFile.py/access?contribId=16&sessionId=6&resId=0&materialId =slides&confId=7691.

- K Pauwels, et. al, ”Single crystalline LuAG fibers for homogeneous dual-readout calorimeters”, JINST 8 P09019 (2013) also at: http://m.iopscience.iop.org/1748-0221/8/09/P09019. [CrossRef]

- V. Di Benedetto, “Dual Readout Calorimetry as a technique for detectors at future Colliders.”, Universitá del Salento. Ph.D. Thesis (2011).

- M.G. Albrow et al., Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 256 (1987) 23.

- ZEUS Collaboration, A Forward Plug Calorimeter for the ZEUS Detector, DESY-PRC-97-02.

- C. Gattoetal, ADRIANO: A Dual-readout Integrally Active Non-segmented Option for future colliders, presentedat: 2nd International Conferenceon Technology and Instrumentation in Particle Physics (TIPP 2011)8-14 June 2011, Chicago, USA.also at:http://indico.cern.ch/contributionDisplay.py?contribId=34&confId=102998.

- C. Gatto et al, Preliminary Results from a Test Beam of ADRIANO Prototype, in: XVth International Conference on Calorimetry in High Energy Physics (CALOR2012) 4–8 June 2012, Santa Fe, USA, published in Journal of Physics: Conference Series Volume 404 2012. also at: http://iopscience.iop.org/1742-6596/404/1/012030;jsessionid=8B5D98DEAD55D7DB573654920CE2E734. [CrossRef]

- T1015 Collaboration, http://www-ppd.fnal.gov/FTBF/TSW/PDF/T1015_mou_signed.pdf (2011).

- L. Hu et al., Radiation Damage of Tile/Fiber Scintillator Modules for the SDC Calorimeter, FERMILAB-TM-1769 (1992). [CrossRef]

- R. Wigmans, et al., Dual-Readout Calorimetry for the ILC - A University Program of Accelerator and Detector Research for the International Linear Collider (vol. III) FY 2005 - FY 2007 also at: http://www.hep.uiuc.edu/LCRD/LCRD _UCLC_proposal_FY05/6_16_Wigmans_LCRD1.

- The glass proposed for this project is SF57HHT produced by Schott Glasswerke (Mainz, germany). All simulations have been performed using the corresponding chemical and optical parameters as provided by the manifacturer.

- C. Gatto, “The software system for the 4th Concept experiment”. 4th Concept Collaboration internal document, 2006.

- http://aliweb.cern.ch/Offline.

- S. Agostinelli et al., Nucl. Instr. and Meth. A 506 (2003), p. 250.

- http://root.cern.ch/drupal/content/vmc.

- M.P. Guthrie, R.G. Alsmiller and H.W. Bertini, Nucl. Instr. and Meth. 66 (1968), p. 29.

- J. V. JELLEY,Äerenkovradiation and its applications, Br. J. Appl. Phys. 6 (1955),p. 227.

- We simulated the SiPM’s produced at FBK, Trieste, in 2010. They kindly which provided the PDE tables.

- Investigation of a Crystal Calorimeter Technology with longitudinal Segmentation, Diploma thesis, Humbolt University at BERLIN, 2004.

| Detector | SciFib | SciFib | WLS | WLS | Capillary | Capillary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layout | diam. | pitch | diam. | pitch | Mat. | thick |

| [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [m] | ||

| 2x2 | steel | 150 | ||||

| 3x3 | steel | 150 | ||||

| 4x4 | steel | 150 | ||||

| 5x5 | steel | 150 | ||||

| 6x6 | steel | 150 | ||||

| 4x4_2 | steel | 200 | ||||

| 4x4_3 | steel | 150 | ||||

| 4x4_4 | steel | 150 | ||||

| 4x4_4 | steel | 150 |

| Detector | hadr | EM | Tot | hadr | EM | Tot | Tot | Tot | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layout | |||||||||||

| 2x2 | 630.6 | 424.8 | 1055.4 | 265.7 | 60.6 | 326.3 | 1109.7 | 479.4 | 1.485 | 4.384 | |

| 3x3 | 251.3 | 180.5 | 431.8 | 287.6 | 66.8 | 354.3 | 447.9 | 511.7 | 1.392 | 4.308 | |

| 4x4 | 146.1 | 109.2 | 255.3 | 285.1 | 68.3 | 353.4 | 279.2 | 513.2 | 1.338 | 4.176 | |

| 5x5 | 93.0 | 70.6 | 163.6 | 282.8 | 69.1 | 351.9 | 178.7 | 507.9 | 1.317 | 4.094 | |

| 6x6 | 70.3 | 54.3 | 124.5 | 279.7 | 68.5 | 348.2 | 137.2 | 498.3 | 1.296 | 4.081 | |

| 4x4_2 | 139.7 | 107.9 | 247.6 | 273.6 | 66.4 | 340.0 | 261.4 | 493.2 | 1.295 | 4.122 | |

| 4x4_3 | 296.5 | 211.7 | 508.3 | 282.6 | 67.1 | 349.7 | 527.5 | 509.4 | 1.400 | 4.208 | |

| 4x4_4 | 648.8 | 442.0 | 1090.8 | 270.5 | 63.9 | 334.5 | 1132.7 | 497.2 | 1.468 | 4.230 | |

| DRS Ref.[13] | 126.5 | 79.8 | 206.3 | 6.4 | 1.1 | 7.4 | 231.7 | 11.3 | 1.584 | 5.944 |

| Detector | Fit. par. | Fit. par. | Fit. par. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layout | |||

| 2x2 | 0.23 | 0.014 | 14.37 |

| 3x3 | 0.29 | 0.022 | 4.95 |

| 4x4 | 0.35 | 0.022 | 2.53 |

| 5x5 | 0.43 | 0.022 | 2.08 |

| 6x6 | 0.48 | 0.028 | 1.58 |

| 4x4_2 | 0.36 | 0.020 | 5.89 |

| 4x4_3 | 0.31 | 0.018 | 7.33 |

| 4x4_4 | 0.27 | 0.020 | 1.42 |

| Detector | Fit. par. | Fit. par. |

|---|---|---|

| Layout | a | b |

| 2x2 | 0.22 | 0.004 |

| 3x3 | 0.27 | 0.005 |

| 4x4 | 0.31 | 0.012 |

| 5x5 | 0.36 | 0.016 |

| 6x6 | 0.39 | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).