1. Introduction

According to the WHO, in some developing countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, 80% of the population relies on traditional medicine, especially in rural areas, because of the proximity and accessibility of this type of care at an affordable cost and mainly because of the lack of access to modern medicine for these populations [

1].

In Burkina Faso, more than 80% of the population regularly relies on traditional medicine and medicinal plants to treat various ailments. This situation is based on traditional medical knowledge that is deeply rooted in the local culture. The development of this traditional medical knowledge offers a wealth of potential and prospects in healthcare for African countries [

2,

3].

With scientific progress, phytotherapy is evolving towards modern phytotherapy, also known as "rational phytotherapy" or "medical phytotherapy", which uses modern methods to extract the active ingredients contained in medicinal plants and validates their beneficial properties for health through a scientific approach of biochemical and pharmacological analyses supported by computer power, as well as clinical trials [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Modern herbal medicine is based on scientific evidence and uses active plant extracts, standardised and marketed as finished products in phytomedicines.

Phytomedicines (PMs) and Improved Traditional Medicines (ITMs) are a vital alternative to health spending in most African countries, which are still 90% dependent on foreign pharmaceutical companies and laboratories [

8].

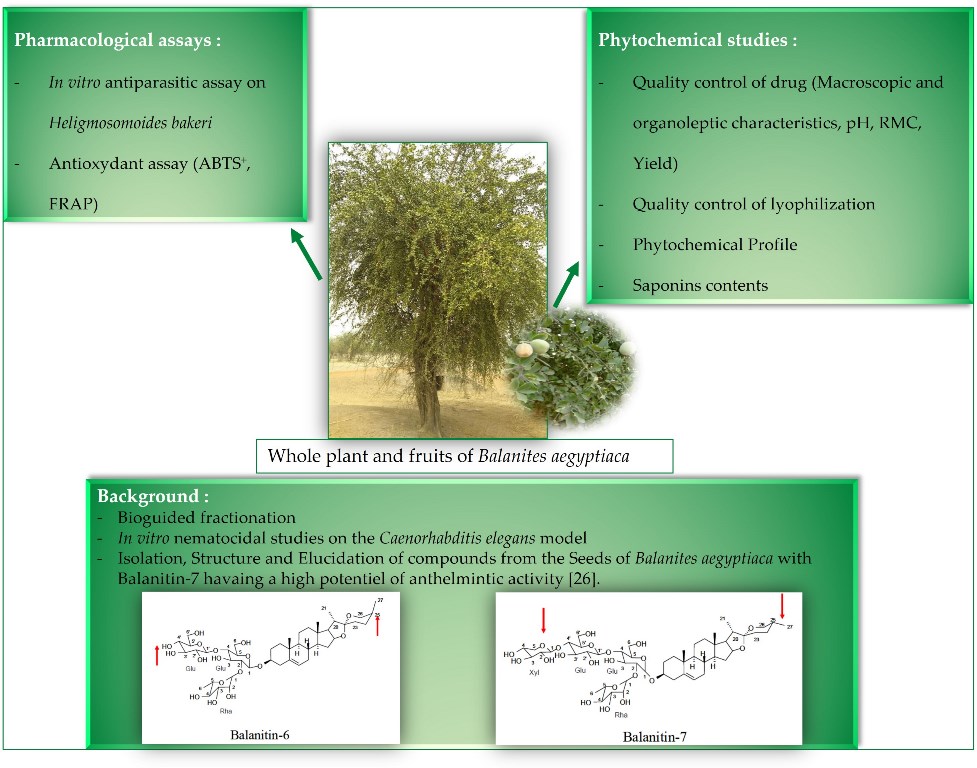

Because of the high medical, scientific and socio-economic stakes involved in the industrial exploitation of research results, the “Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé (IRSS)” has developed a phytomedicine based on the seeds of

Balanites aegyptiaca (B. aegyptiaca).

B. aegyptiaca, or desert date palm, is a very thorny phanerophyte found in the arid regions of tropical Africa, from the Sahara to Palestine, Arabia and India. Balanites aegyptiaca is widely used in traditional human and veterinary medicine throughout Africa for its many properties [

9]. Throughout the world, the different parts of this plant are used to treat many diseases, such as bacterial and fungal infections, haemorrhagic menstruation, goitre, bilharzia, malaria, colic, yellow fever, haematuria, hydrocele, haemorrhoids, dermatitis, abdominal pain, colds, diabetes, arterial hypertension and helminthic infections [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Numerous studies based on ethnopharmacology have reported evidence of using

B. aegyptiaca seeds in treating parasitosis for over twenty years [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Several studies have also been carried out at the IRSS on extracts of the plant, demonstrating the antiparasitic properties of its seeds [

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, the method of obtaining these extracts still needs to be optimised and standardised in order to obtain products that meet quality standards, have higher yields and are safe for industrial production. The aim of this work is to optimise the conditions for obtaining freeze-dried

B. aegyptiaca seeds for the formulation of phytomedicines by studying several factors that may affect the yield and quality of the final extract.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, and the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3. Discussion

The plant material was yellow, with a coarse texture, a very characteristic odor, and a bitter taste. Aqueous extraction was performed as recommended by the health tradipratician. Water, the most polar solvent, was used to extract a wide range of polar compounds. It has the advantage of dissolving many substances; it is inexpensive, non-toxic, non-flammable and highly polar [

28,

29]. The lyophilizates varied in color from yellow to light yellow, depending on the mass to volume ratio, with a bitter-sweet taste, the sweetness being more pronounced in lyophilizates with a low mass to volume ratio and a fine texture. These changes in characteristics are thought to be related to extraction [

30]. Organoleptic and macroscopic characteristics are parameters used in the identification and quality control of raw materials. These data help to establish quality control and assurance standards and to define the purity of herbal or synthetic drugs [

31]. Visual assessment of appearance sometimes allows rapid identification of certain herbal drugs, checking their degree of purity according to the presence or absence of foreign elements, moulds, etc., and possibly detecting adulteration or falsification. A color change may indicate deterioration due to poor drying or storage conditions [

29,

32].

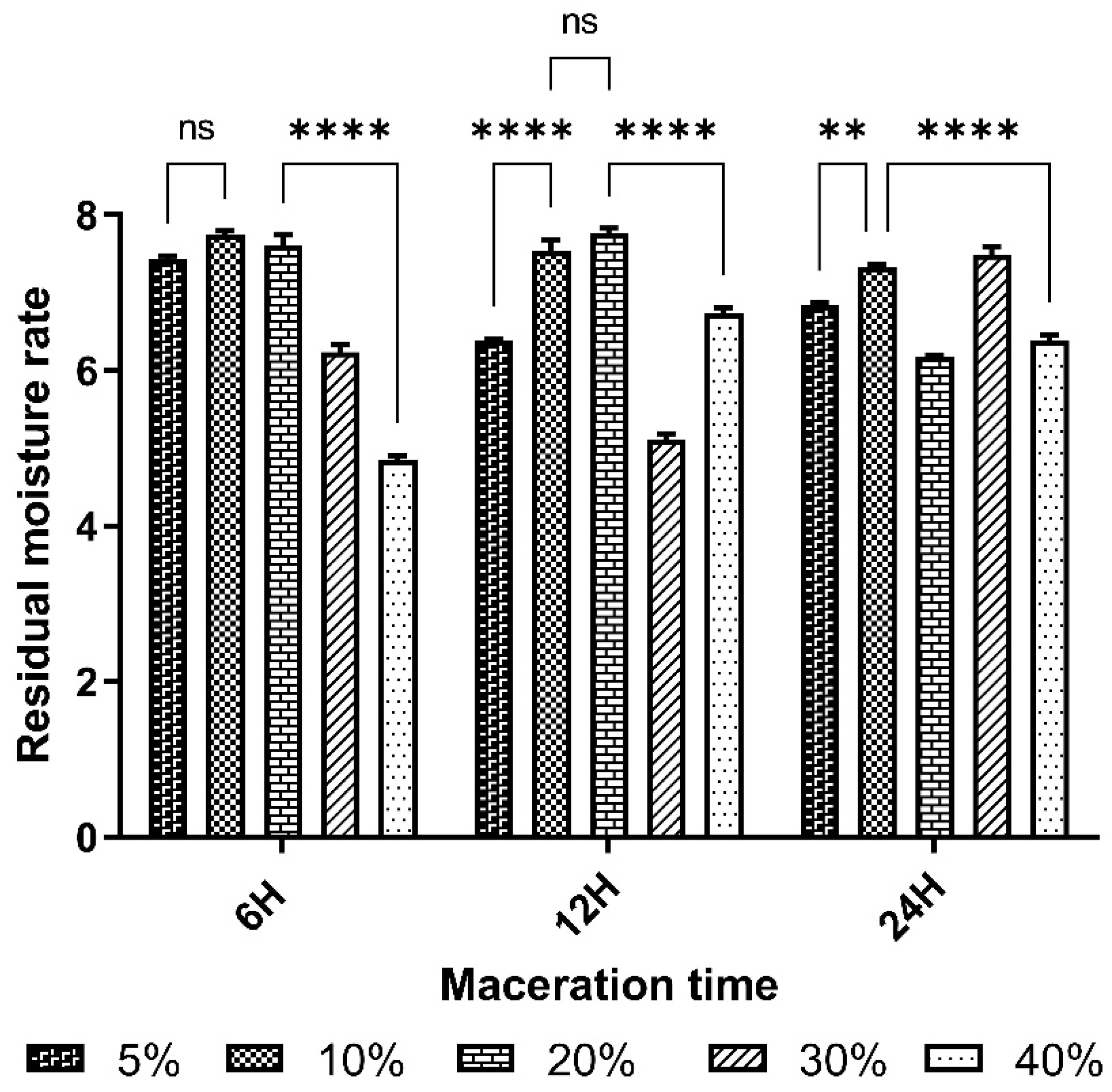

The result for the residual moisture content of the plant material was 4.84 ± 0.06. The control of this parameter reduces errors in estimating the actual weight of the plant material and guarantees the quality during the storage period [

33]. This value, below 10%, indicates that the powder is sufficiently dry and can be stored during the handling period without the development of molds or yeasts, according to the standards of the European Pharmacopoeia [

31]. In fact, too high a water content (above 10%) could promote enzymatic reactions with negative consequences on the appearance of the plant drug, its organoleptic characteristics and its therapeutic properties during the shelf life of the plant material powder. High residual moisture also favors the proliferation of microorganisms such as bacteria, yeasts and moulds. These results are similar to those obtained by Sanfo [

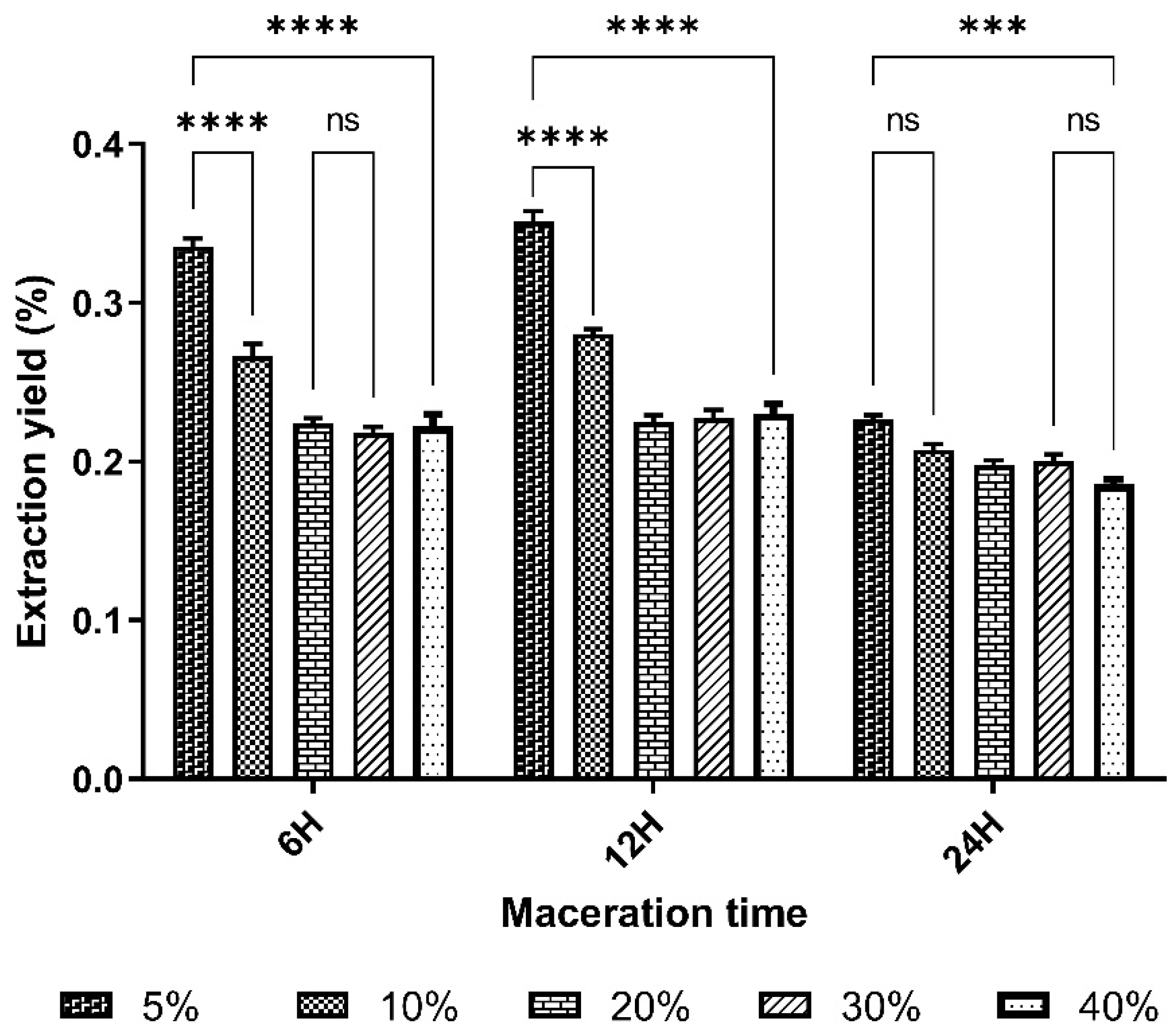

24], who obtained THRs below 10%, i.e. 4.26%. The RMC of lyophilisates varied from 5.11% to 7.76%, with an average of 6.65%. These lyophilises were more or less dry and could be stored without mould or yeast growth. The best yields, 35.12±1.1% and 33.54%, respectively, were obtained from extracts macerated for 12 h and 6 h at a mass/volume ratio of 5%.

The mass/volume ratio parameter has a significant effect on yield. The yield results show that increasing the solvent volume by decreasing the m/v ratio improves the extraction yield up to a ratio of 5%; in fact, the best yields are obtained with the lowest m/v ratio. This is consistent with the principle of mass transfer, which states that the driving force during extraction is the concentration gradient between the solid and the external liquid medium. This force becomes important when the liquid/solid ratio used is higher [

34]. Similar results were obtained by Cacace who evaluated the effect of the solids ratio on the extraction rates in their studies [

34]. They found that increasing the volume of solvent had a positive effect on extraction regardless of the type of solvent used.

Increasing the extraction time can often improve the extraction yield. This is mainly due to the fact that a longer contact time between sample and solvent allows a better solubilisation of the target compounds in the solvent. This more efficient solubilisation leads to a more complete extraction of the desired compounds, thus increasing the overall extraction yield [

35]. We can stated that a long extraction time would allow for good extraction and therefore good yield.

However, in this study, after 6 hours, increasing the time did not significantly improve the yield. This could be explained by the phenomenon of extraction saturation when time is extended over a long period [

36]. This result is similar to that of Tiendrebeogo who found that the time parameter alone in maceration was not sufficient to significantly improve extraction [

36]. The results of our study show that the conditions for optimal crude yield from aqueous maceration of

B. aegyptiaca seeds crush would be maceration for 6 h at a mass/volume ratio of 5%.

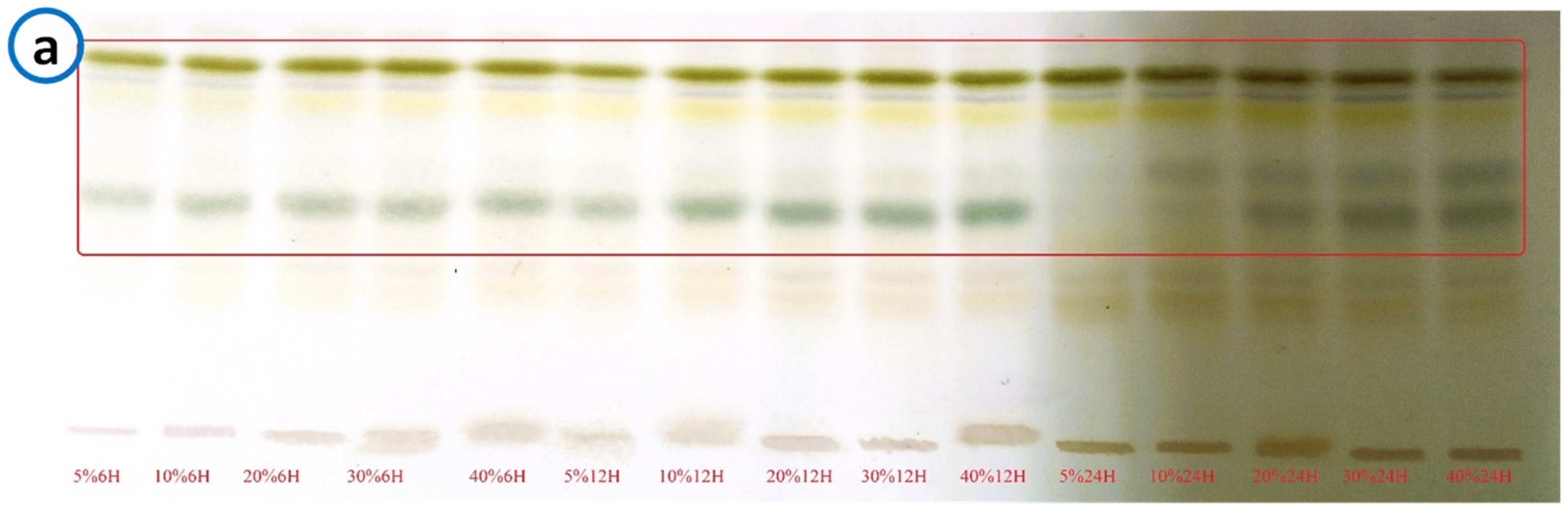

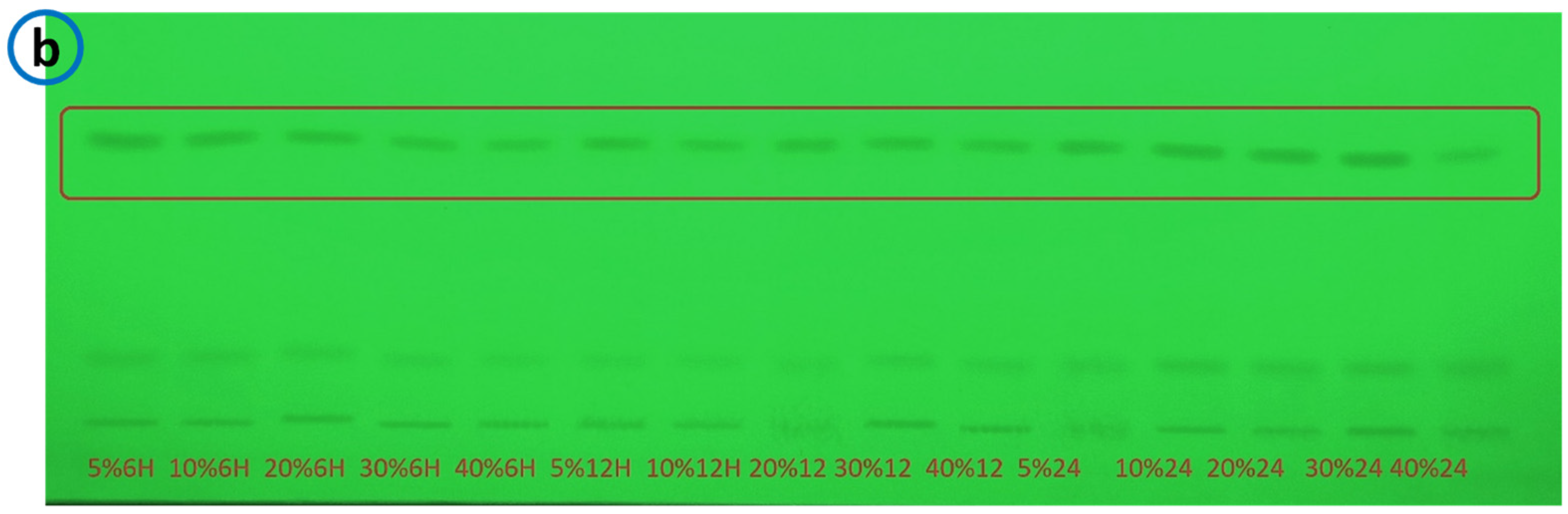

Phytochemical screening of the extracts by thin-layer chromatography on chromatoplates using the methods described by Wagner and Bladt revealed metabolites such as saponins and flavonoids. Saponins were the most essential compounds in the extracts, as significant precipitation reactions were obtained with appropriate reagents. Chemical screening revealed spots of equal intensity in all extracts.

Assay results ranged from 9.27±0.07 mg/g to 13.81±0.04 mg/g. Analyses show that the highest levels were obtained at the 12-hour maceration time with 13.81±0.04mg/g at 10%, 12.89±0.06mg/g at 30%, 12.59±0.02mg/g at 40%, 12.32±0.07mg/g at 5%. The most significant content obtained with 12 hours time parameters and 10% mass/volume ratio was 13.81±0.04mg/g.

The antioxidant activity results by ABTS ranged from 3.57±0.21 μg/mL to 4.82±0.10μg/mL. The most active extracts (4.82±0.10), (4.54±0.13) and (4.52±0.19) were obtained at 6 h of the 5% and 10% ratios and 12 h of the 5% ratio, respectively. The lower the concentration (IC

50), the higher the antioxidant effect [

37]. The phytochemical groups identified, namely flavonoids, tannins and saponins, are thought to be responsible for the antioxidant activity of the extracts [

38,

39].

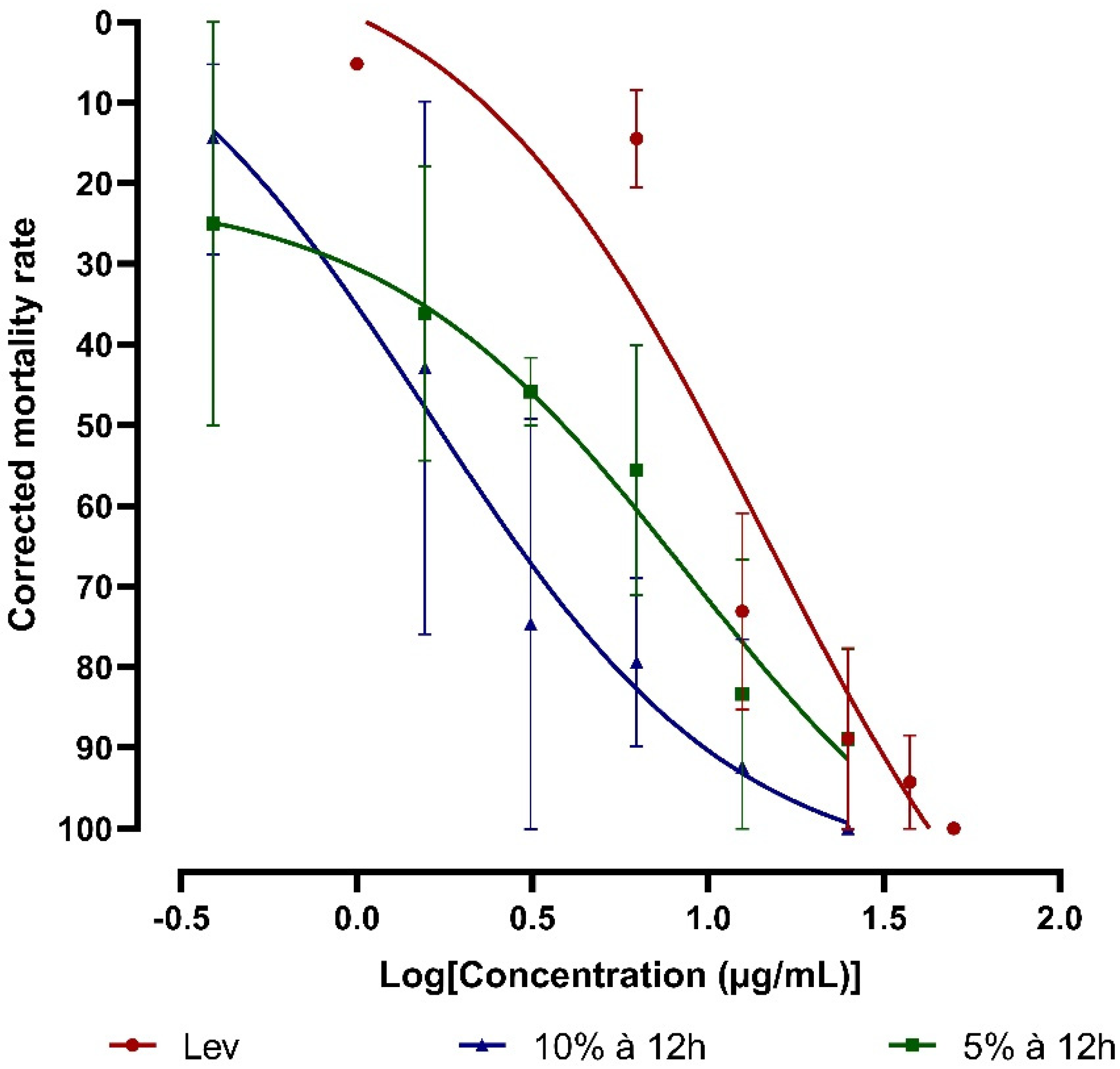

These tests allowed us to determine the anthelmintic activity of the two

B. aegyptiaca seeds extracts with the highest yields while maintaining their physicochemical properties against

H. bakeri L

1 larvae [

40,

41]. The results obtained show an interesting larvicidal effect. Indeed, the 5% extract showed a maximum effect of 84.64% larval mortality at a concentration of 25 µg/mL, while the 10% extract resulted in 100% mortality of

H. bakeri L

1 larvae at the same concentration—also, the IC

50 (extract at 5%) < IC

50 (extract at 10%). Therefore, we can say that the 10% extract at 12h is more effective and potent than the 5% extract. The difference in the activity of the extracts tested may be due to the content of secondary metabolites, especially saponins, which are antiparasitic substances present in the extracts [

42,

43].

B. aegyptiaca has been chemically investigated for various classes of constituents. It is reported to contain several secondary metabolites and bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, alkaloids, glucosides, phenols, steroids, saponins, furanocoumarins, diosgenin, N-trans-feruloyl tyramine, N-cis-feruloyl tyramine, trigonelline, balanitol, fatty acid [

26,

44]. The 10% extract at 12 h has the highest saponins content compared to the other extracts. In

B. aegyptiaca fruits, saponins such as balanins 4, 5, 6 and 7 have been isolated.

The activity of the different extracts obtained by successive depletion of

B. aegyptiaca seeds powder was evaluated on

C. elegans. Aqueous and methanolic extracts resulted in worm mortality. However, the aqueous extract (IC

50 = 1.0 mg/mL) was much more nematocidal on

C. elegans than the methanolic extract (IC

50 = 25.3 mg/mL). Pure balanitin-7 obtained after successive column fractions showed very high nematocidal activity (IC

50 = 0.1μg/mL, expressed as aqueous extract equivalent) [

26]. Based on the results of his study, Gnoula hypothesised that the major nematocidal agent present in the seeds of

B. aegyptiaca may be balanitin-7 (Bal-7), a heteroside of the diosgenyl saponins family [

26]. Since the 10% 12 h extract is rich in saponins, we can assume that the larvicidal activity on

H. bakeri is related to the high presence of this phytochemical group.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

The plant's raw material is the fruit of B. aegyptiaca. These fruits were harvested in March 2021 in Manga, in the south-central region of Burkina Faso, 100 km from the capital Ouagadougou. A plant sample was collected and identified at the Joseph KI-ZERBO University Herbarium under identification number 17928 with herbarium reference number 6916.

4.2. Quality Control of Drug

Macroscopic and organoleptic characteristics: The organoleptic characteristics (taste and smell) were determined by tasting and sniffing the powder [

45].

Determination of pH: The pH was determined by putting the pH-meter electrode (Eutech, Singapore) in 1% (w/v) aqueous solutions of each vegetable material (thrice). The test was performed in triplicate, and the mean and standard deviation were calculated (m ± standard deviation, n = 3).

Residual moisture content: The residual moisture content of the powders was determined according to the thermogravimetric method of the European Pharmacopoeia 10th edition in an oven [

31]. The assay was performed in triplicate on one (01) gram of powder. The mean and standard deviation were calculated (n = 3, mean, standard deviation).

Total ash content: Total ash levels were determined according to the European Pharmacopoeia 10e edition by calcining one (01) gram of each plant powder in a furnace (Bouvier, Belgium) at about 600°C. Total ash content was expressed as percentage.

Microbiological quality: The microbial load assayed were total microbial flora, Salmonella and thermo-tolerant coliforms. Total microbial flora and Salmonella were determined by the method of the European Pharmacopoeia 6th edition. Thermo-tolerant coliforms were determined according to ISO 7218. Colony counts were performed for calculations of the number of colony forming units per gram (CFU / g).

4.3. Quality Control of Lyophilisation

It involves the maceration of B. aegyptiaca almond powder, varying the parameters of mass/volume ratio and maceration time to obtain a higher yield of lyophilisation, using a technique that does not involve the use of an organic solvent, such as cryoconcentration. A 50 g test sample of B. aegyptiaca seed powder is macerated in different volumes of distilled water (1000 mL, 500 mL; 250 mL, 165 mL, 125 mL) at ratios of 5%, 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% and stirred manually. The mixture is macerated at room temperature for 6, 12, 24 or 48 hours.

At the end of the maceration time, the extracts obtained are filtered through a nylon filter. The filtrates are delipidated by freezing for 5 hours, and then the supernatant (lipid) is removed. The filtrates are centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes and filtered again. The final filtrates are frozen and lyophilised for further analysis.

4.4.1. Macroscopic and Organoleptic Characteristics

Characteristics such as texture, color, taste and odor were determined by the method described in the 10th edition of the European Pharmacopoeia, using the sense organs. The study was carried out with three persons and the similar results obtained by the majority were accepted. Color was determined by observation with the naked eye, taste by tasting the powders, odor by sniffing, and texture by touching the powders [

31].

4.4.2. Determination of pH

It is determined using a pH meter. After stabilisation, dip the pH meter electrode in a pH 7.00 buffer solution and rinse with distilled water; place the electrode in the plant material or lyophilizate and shake until the pH is stable, take the pH reading, and finally, rinse the electrode with distilled water.

4.4.3. Residual Moisture Content

The residual moisture content of the plant material or Balanites lyophilises was determined by the gravimetric method.

A test sample of 1 g of powder in an aluminium dish was placed in the halogen desiccator at a temperature of 105°C for 15 mins. After the allotted time, the RMC value is displayed, calculated according to the following formula:

THR= [(Mi-Mt)] /Mi x 100

Mi: test sample

Mt: Mass after drying

4.4.4. Extraction Yield

The extraction yield is determined by the following formula:

R = (P×100) / P0

R: extraction yield

P: weight (g) of dry extract obtained after lyophilisation

P0: weight (g) of plant material test sample.

4.5. Determination of Phytochemical Profile of Plant Material and Lyophilizate

Phytochemical screening of extracts is performed by thin-layer chromatography on chromatophores according to the methods described by Wagner and Bladt. The metabolites sought are saponins, terpene and steroid compounds, flavonoids, tannins, etc.

TLC is a separation technique in which the compounds to be separated are absorbed and partitioned according to their affinity between a solid phase (silica gel) and a mobile phase (migration solvent). TLC analyses are performed according to the method described by Wagner and Baldt [

46]. A 20 mg mass of lyophilizate was dissolved in 5 mL of distilled water. A 2µL volume of the sample obtained was applied to a chromatoplate (Silica 60 F254; 10cm×5cm; rigid aluminum support). Deposits are eluted along a 7cm path in a glass tank containing a solvent system whose composition depends on the chemical group of interest. After elution, the chromatoplates are removed and dried at room temperature (25°C), then in a ventilated oven (40°C) for 5 minutes.

4.6. Saponins Contents

The following color developing reagent solutions were prepared: (A) 0.5 mL p-anisaldehyde and 99.5 mL ethyl acetate, and (B) 50 mL concentrated sulfuric acid and 50 mL ethyl acetate. 2 mL of 1 mg/mL diluted extract solution was added to a 10 mL test tube. One mL each of reagent solutions (A) and (B) were added and the test tube was sealed with a glass stopper. After shaking, the test tube was placed in a water bath maintained at 60°C for 10 minutes to develop color, and then allowed to cool in a water bath maintained at room temperature for 10 minutes. Since the boiling point of ethyl acetate is 76°C, the temperature of the water bath must be carefully controlled. The absorbance of the developed color solution was measured. Methanol was used as a control for the absorbance measurement. Solutions containing diospogenin and 2 mL of methanol were used to obtain a calibration curve [

47].

4.7. Pharmacological Study

4.7.1. ABTS+ Free Radical Scavenging Assay

The original ABTS+ assay was based on the activation of metmyoglobin with hydrogen peroxide in the presence of ABTS to produce the radical cation in the presence or absence of antioxidants. This has been criticised on the basis that the faster reacting antioxidants may also contribute to the reduction of the ferryl myoglobin radical. A more appropriate format for the assay is a decolorisation technique in which the radical is directly generated in a stable form prior to reaction with putative antioxidants. The ABTS

-+ radical scavenging assay was used to determine the antioxidant capacity of the extract according to Re et al. [

48]. ABTS cation radical was generated by mixing in water to a concentration of 7 mM. ABTS radical cation (ABTS

-+) was generated by reacting ABTS stock solution with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate and allowing the mixture to stand in the dark at room temperature for 12-16 h before use. Ethanol was added to the prepared solution to adjust the absorbance. To evaluate the extract, 200 µL of ABTS

-+ radical solution was added to 20 µL of extract in a 96-well microplate. The blank for this assay was a mixture of ABTS and ethanol. Absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a BioRAd spectrophotometer (model 680, Japan) after 30 min incubation in the dark at 25°C. Trolox was used as a positive control. The data were the mean of three determinations. The antioxidant capacity using the ABTS method was expressed as trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC).

4.7.2. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

The reducing power of the extracts was determined by a method previously described by Ibe et al. [

49]. A concentration of 1 mg/mL (0.5 mL) of sample extracts was mixed with 1.25 mL (0.2 M, pH 6.6) sodium phosphate buffer and 1.25 mL 1% potassium ferricyanide. The mixture was vortexed and incubated at 50°C for 30 minutes. After incubation, 1.25 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (w/v) was added and the mixture was centrifuged at 1000 rpm in a refrigerated centrifuge for 10 min at room temperature. The top layer (0.625 mL) was mixed with 0.625 mL of deionised water and 0.125 mL of 0.1% ferric chloride (FeCl

3), and the absorbance of the reaction mixture was evaluated at λ max of 700 nm.

The extract concentration giving 0.5 of the absorbance (IC50) was calculated from the graph of the absorbance registered at 700 nm against the corresponding extract concentration, and ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The assay was performed in triplicate.

4.8. In Vitro Evaluation of Larvicidal Activity against Heligmosomoides Bakeri

The tests were conducted with the extracts that gave the best yields and maintained their physicochemical characteristics. These were the 5% and 10% extracts of

B. aegyptiaca seeds. To test the effects of the extracts, 1 mL of a solution containing 50-60 parasite larvae was added to 14 Petri dishes (10 mm by 35 mm diameter) at two concentrations [

50]. The concentrations were 0.39, 1.56, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5 and 25 μg/mL for the different extracts. The tests were repeated 6 times for each treatment and the controls. Levamisole (Lev) was used as a positive control at concentrations of 1; 6.25, 12.5; 25, 37.5 and 50 μg/mL. The plates were covered and the larvae were incubated at room temperature for 24 hours, after which 2 to 3 drops of formalin were added to each plate to fix the different stages of the parasite life cycle. At the end of the time, the number of dead or immobile larvae per Petri dish was counted using a light microscope (at 10X magnification). The adjusted mortality rate (%) is calculated according to the method of Wabo et al. [

51]:

With : Mc % Corrected mortality rate

Mce is the mortality rate during the test

Ms is the mortality rate obtained with the control negative

4.9. Statistical Analysis

The mortality rates were analysed with GraphPad Prism 10.0.2 software. Two-way ANOVA followed by "Tukey" Multiple Comparison Test was used to compare the extracts. P < 0.05 was considered significantly different. The results were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The variation was considered significant at P < 0.05. ns is considered not significant. n = 3. Statistical significance was defined as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.