1. Introduction

The objective of this article is to present a systemic-structural approach [

1] – or simply, a “structural approach” – for the concurrent teaching of the basic notions of 1) propositional calculus and 2) set theory at an introductory level. The term “systemic” refers to the presentation of isomorphisms existing between the “parallel disciplines” considered (in this case, propositional calculus and set theory). For this purpose, from these disciplines the pairs of corresponding operations will be discussed in section 2, and then, the pairs of corresponding laws, or theorems, in section 3.

This instructional method is based mainly on the structure of the subject matter presented, and not on the diverse possible ways of communicating it, such as presential or virtual classes, using different amounts of audiovisual resources, or having a majority of lectures or discussion groups. The basic hypothesis of this instructional approach is the following: The structure itself is what facilitates learning. For this reason, the term “structural” is used for the approach considered.

It is supposed that those reading this article teach in high school or college and are already familiar with the notions of logic and mathematics to be considered here. For this reason, they will not be covered too formally or exhaustively; a simple review of some of their main characteristics will be provided instead. In the remainder of this section, brief consideration will be given to some of these notions which are important for this article.

A proposition – or statement – is a linguistic expression to which a truth value may be assigned: According to classical bivalent logic, each proposition is either true or false. Thus, for example, “Caballito is a neighborhood of the Argentine capital, Buenos Aires” can be considered a proposition. That does not occur with “What is your name?” or “Sit down!”.

In this article, when considering a sole proposition, it will be called “q”. When considering more than one proposition, the denominations , , , … will be used. The negation of a proposition will be symbolized by a horizontal bar above that proposition. Thus the negation of the proposition q – that is, not q – will be symbolized as . Of course, any negated proposition, such as , is also a proposition.

In set theory, the universal set is the set to which all the elements that can belong to a set – according to the topic covered – belong. If within the framework of that only one other set is considered – that is, a set to which some of the elements in that belong – that sole set will be denominated C. If more than one set of that type is considered, those sets will be denominated , , , ….

The operator of complementation of a set will be symbolized by the symbol placed above the denomination of the set whose complement is sought. Thus, the complement of C is symbolized as . All of the elements belonging to the universal set considered that do not to belong to C belong to the set . The complement sets of , , , … will be symbolized as , … respectively.

Given that all the elements which can be considered when covering a particular topic belong to the universal set symbolized as , no element will belong to its complement, which will be symbolized as . For this reason, will be called the empty set and will be symbolized as ⌀; that is, = ⌀.

In this article it will be admitted that whenever an operation involving sets is carried out, the corresponding universal set considered will be known.

For an introduction to topics of logic and set theory, one may consult [

2]. For a more detailed treatment of topics of logic, [

3,

4] may be consulted. For a more advanced coverage of set theory, one may consult, for example [

5].

2. Pairs of Operations Corresponding to 1) Propositional Calculus and 2) Set Theory

The presence of a zero – 0 – in the truth table of a proposition is equivalent to the truth value “false” of that proposition. The presence of a zero – 0 – in the membership table of a set C (or rather, , , , …) means that an element belonging to the universal set considered does not belong to that set C (that is, to , , , …).

The presence of a one – 1 – in the truth table of a proposition is equivalent to the truth value “true” of that proposition. The presence of a one – 1 – in the membership table of a set C (or rather, , , , …) means that an element belonging to the universal set considered does belong to that set C (that is, to , , , …).

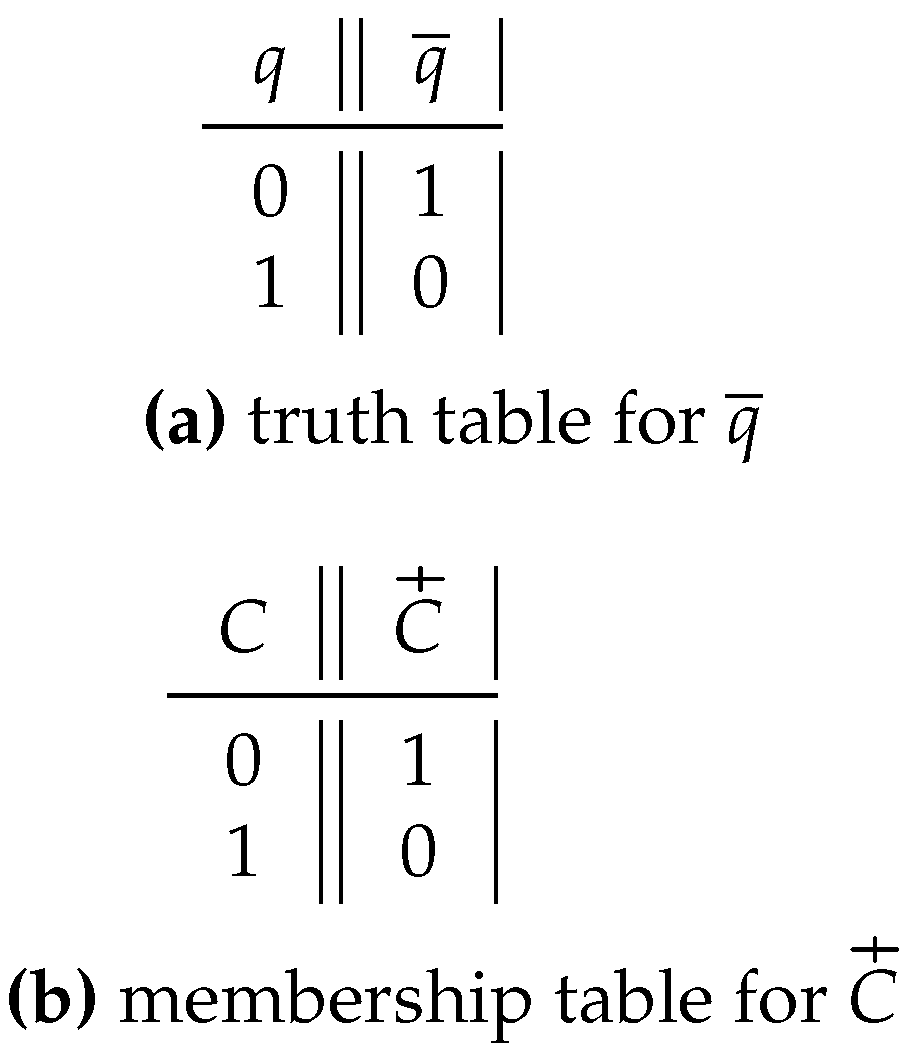

Figure 1 presents a) the truth table of the negation

(not

q) of the proposition

q and b) the membership table of the complement

of a set

C.

The first row of the truth table represented in

Figure 1a is

. The first digit – 0 – in that numerical sequence in column

q means that it is accepted that

q is false. The second digit – 1 – in that numerical sequence means that it is accepted that

is true. In other words, if the proposition

q is false, then its negation (the proposition

) is true.

The second row of the truth table represented in

Figure 1a is

. The first digit – 1 – in that numerical sequence in column

q means that it is accepted that

q is true. The second digit – 0 – in that numerical sequence means that it is accepted that

is false. In other words, if the proposition

q is true, then its negation (

) is false.

The first row of the membership table in

Figure 1b is 0, 1. The first digit – 0 – in that numerical sequence in column

C means that a certain element belonging to the universal set

considered does not belong to the set

C. The second digit – 1 – in that numerical sequence means that the element does belong to the complement set

of

C. In other words, if any element belonging to the universal set

considered does not belong to a set

C, then it does belong to the complement set

of that set.

The second row of the membership table in

Figure 1b is

. The first digit – 1 – in that numerical sequence in column

C means that a certain element belonging to the universal set

considered does belong to the set

C. The second digit – 0 – in that numerical sequence means that the element does not belong to the complement set

of

C. In other words, if any element belonging to the universal set

considered belongs to the set

C, then it does not belong to the complement set

of that set.

The symbol corresponding to the operator of the conjunction of two propositions and will be ∧. The symbol corresponding to the operator of the intersection of two sets and will be symbolized as ∩.

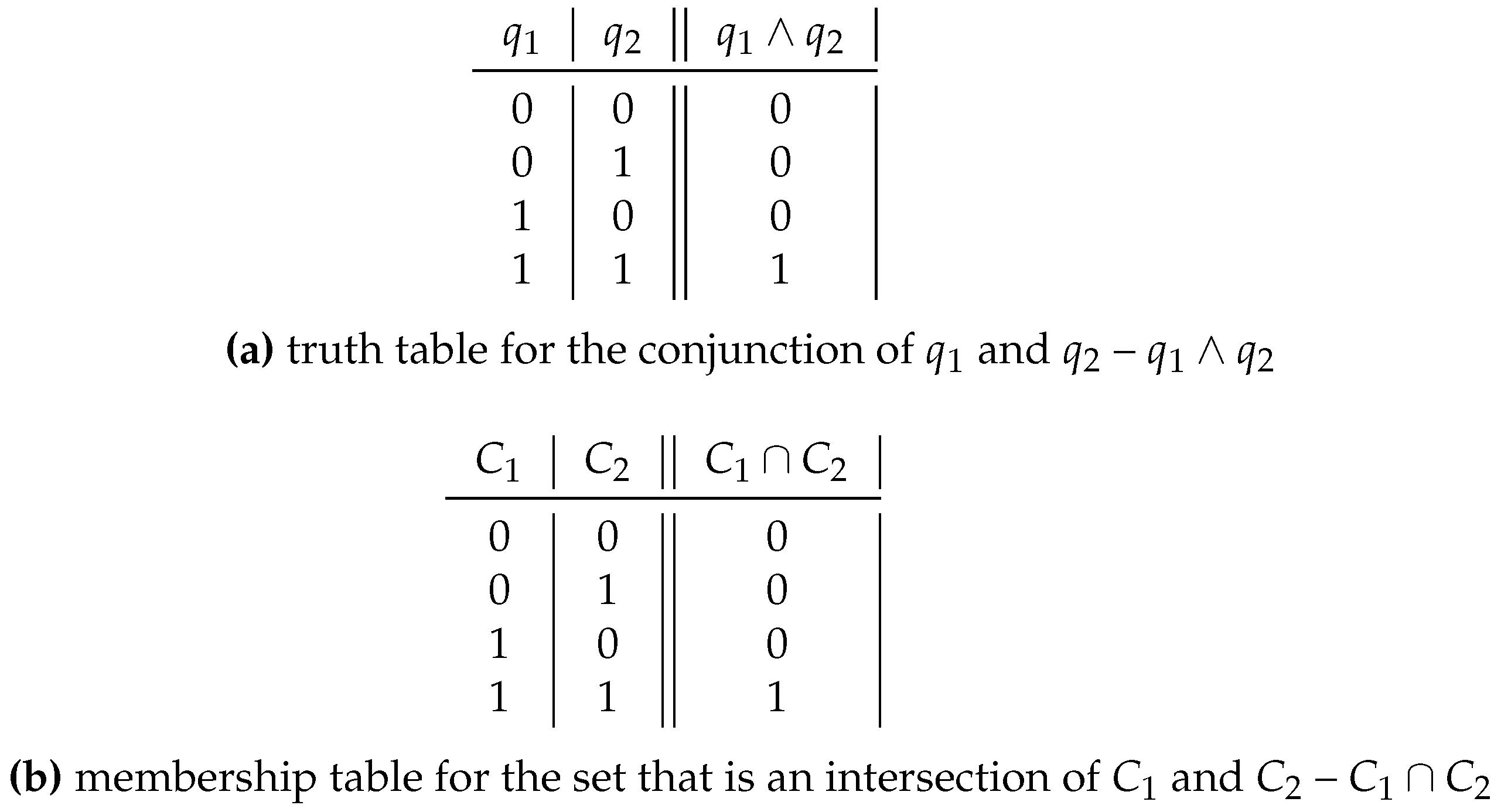

Figure 2 presents a) the truth table for the conjunction

(

and

) and b) the membership table for the intersection set (

) of

and

.

As seen in

Figure 2a, only in the fourth row of the above truth table (where the numerical sequence 1, 1, 1 appears) is there a 1 in the column corresponding to

. In other words, only if

is true as indicated by the first 1 in that numerical sequence, and

is also true as indicated by the second 1 in that numerical sequence, is

also true, as indicated by the third 1 in the numerical sequence considered. In the other three possible cases, considered in the first, second and third rows of the truth table in

Figure 2, there is a 0 in the column corresponding to

, indicating that the proposition is false.

As seen in

Figure 2b, only in the fourth row of the membership table (where the numerical sequence 1, 1, 1 appears) is there a 1 in the column corresponding to

. In other words, only if any element belonging to the

considered belongs to

, as indicated by the first 1 in that numerical sequence, and also belongs to

, as indicated by the second 1 in that numerical sequence, does that element belong to

(the intersection set of

and

).

If

is made to correspond to

,

to

, the operator of conjunction ∧ in propositional calculus to the operator of intersection ∩ in set theory (and as a result the correspondence between

and

is established), the isomorphism existing between the truth table in

Figure 2a and the membership table in

Figure 2b can be observed. In effect, for every 0 in the first table there is a corresponding 0 in the second table, and for every 1 in the first table there is a corresponding 1 in the second table.

The symbol of the inclusive disjunction (inclusive or) of the two propositions and will be ∨. The symbol of the exclusive disjunction (exclusive or) of two propositions and will be . The symbol corresponding to the inclusive union of two sets and will be ∪. The symbol corresponding to the exclusive union of two sets and will be .

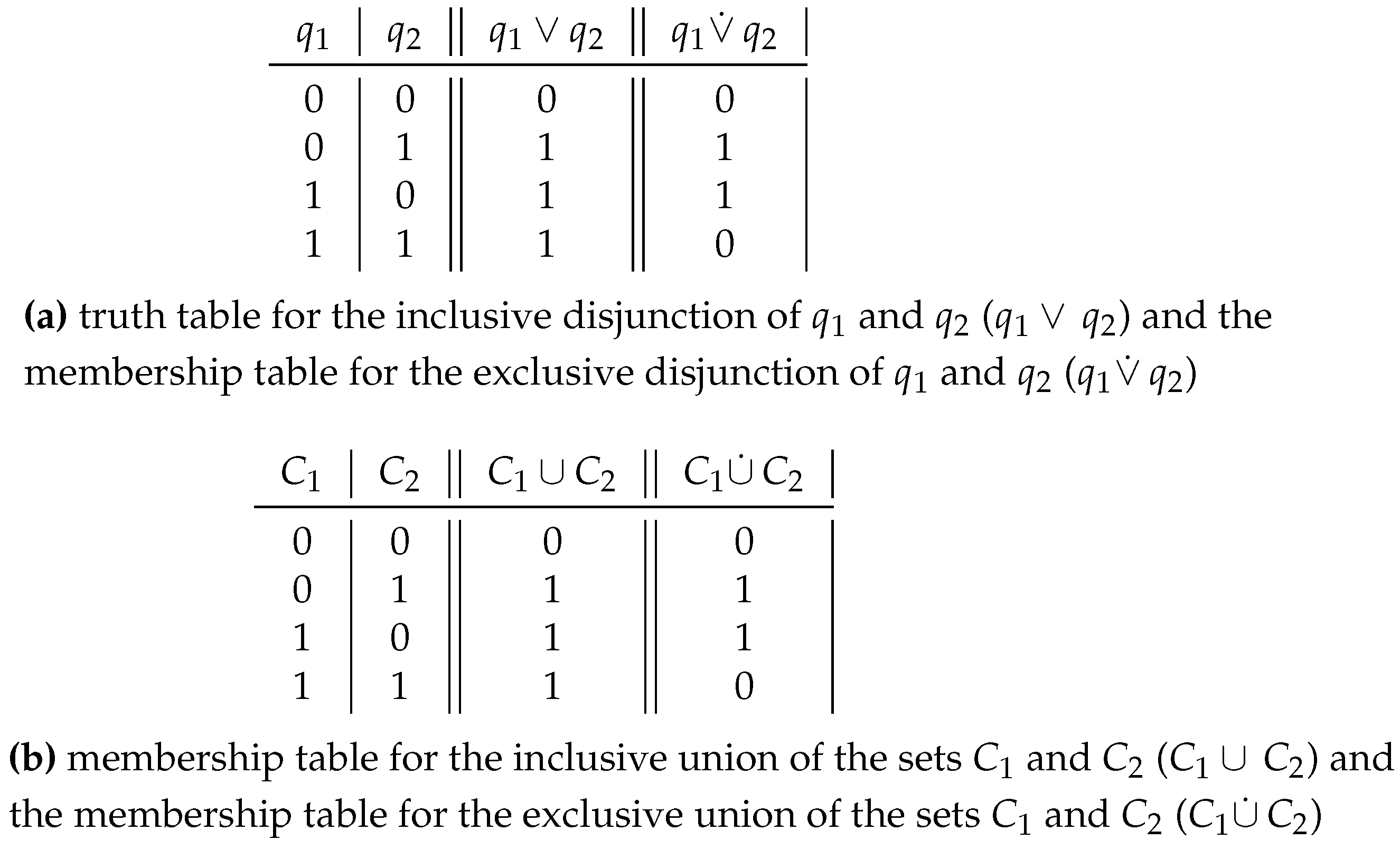

Figure 3 presents a) the truth tables corresponding to the inclusive disjunction of

and

(

) and to the exclusive disjunction of

and

(

), along with b) the membership tables for the inclusive union set of

and

(

) and of the exclusive union set of

and

(

).

If is made to correspond to , to , the operator ∨ in propositional calculus to the operator ∪ in set theory, and the operator in propositional calculus to the operator in set theory, note may be taken of 1) the isomorphism between the truth table corresponding to and the membership table for (given that for every 0 in this truth table, there is a 0 in the membership table), and 2) the isomorphism between the truth table for and the membership table for , for the same reason mentioned in the above isomorphism.

Note that in the column corresponding to there is a sole 0 indicating that the inclusive disjunction is false only when both and are false, as shown by the zeros in the first row both in the column and in the column. Likewise, note that in the column corresponding to there is a sole 0 indicating that any element belonging to the universal set considered does not belong to , only when that element belongs neither to nor to , as shown by the zeros present in the first row both in the column and in the column.

Note that in the truth table for the proposition this proposition is true if only one of the two propositions and is true. Likewise, in the membership table corresponding to it can be seen that only the elements belonging to the universal set considered that belong only to one of the two sets and belong to that set ().

The operator of material implication in propositional calculus is symbolized as →. The proposition (that is, materially implies ) can be read as “If , then ”. The proposition (that is, materially implies ) can be read as “If , then ”. In the proposition , is known as the antecedent of that proposition and is its consequent. In the proposition , is the antecedent of that proposition and is its consequent.

Given two sets and , the use of the operator of membership implication makes it possible to generate the sets C1 ⇸ C2 and C2 ⇸ C1.

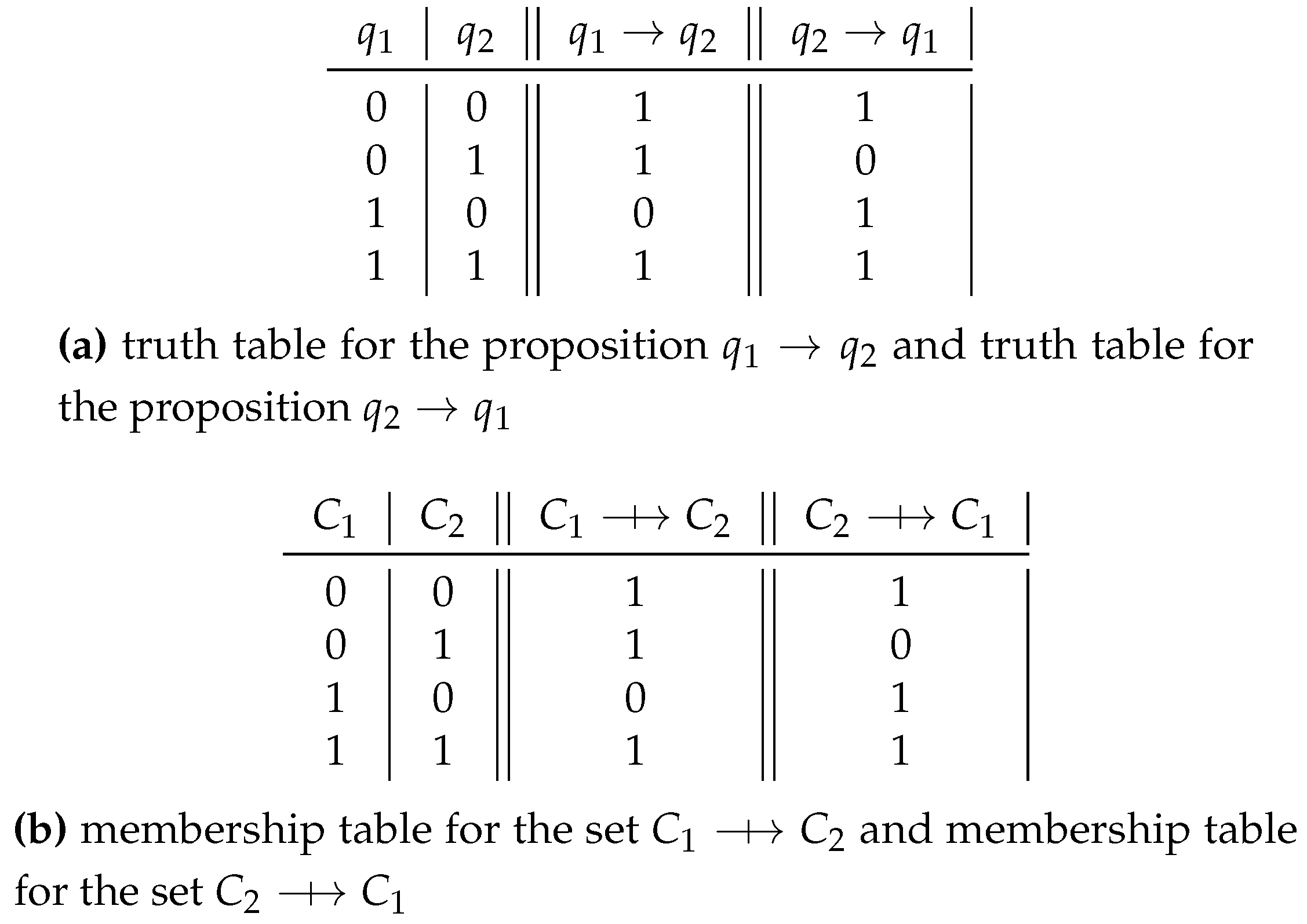

Figure 4 presents 1) the truth table for the proposition

and the truth table for the proposition

, and 2) the membership table for the set

C2 and the membership table for the set

C2 ⇸

C1.

Note that the proposition is false only when is true and is false. Likewise, any element belonging to the universal set considered does not belong to the set only if that element belongs to the set C1 but not to the set C2.

Note also that the proposition is false only when is true and is false. Likewise, any element belonging to the universal set considered does not belong to the set only if that element belongs to the set C1.

The truth table for is isomorphic to the membership table for (Both tables are the same from a purely numerical view point.) This also occurs with the truth table for q2 → q1 and the membership table for C2 ⇸ C1.

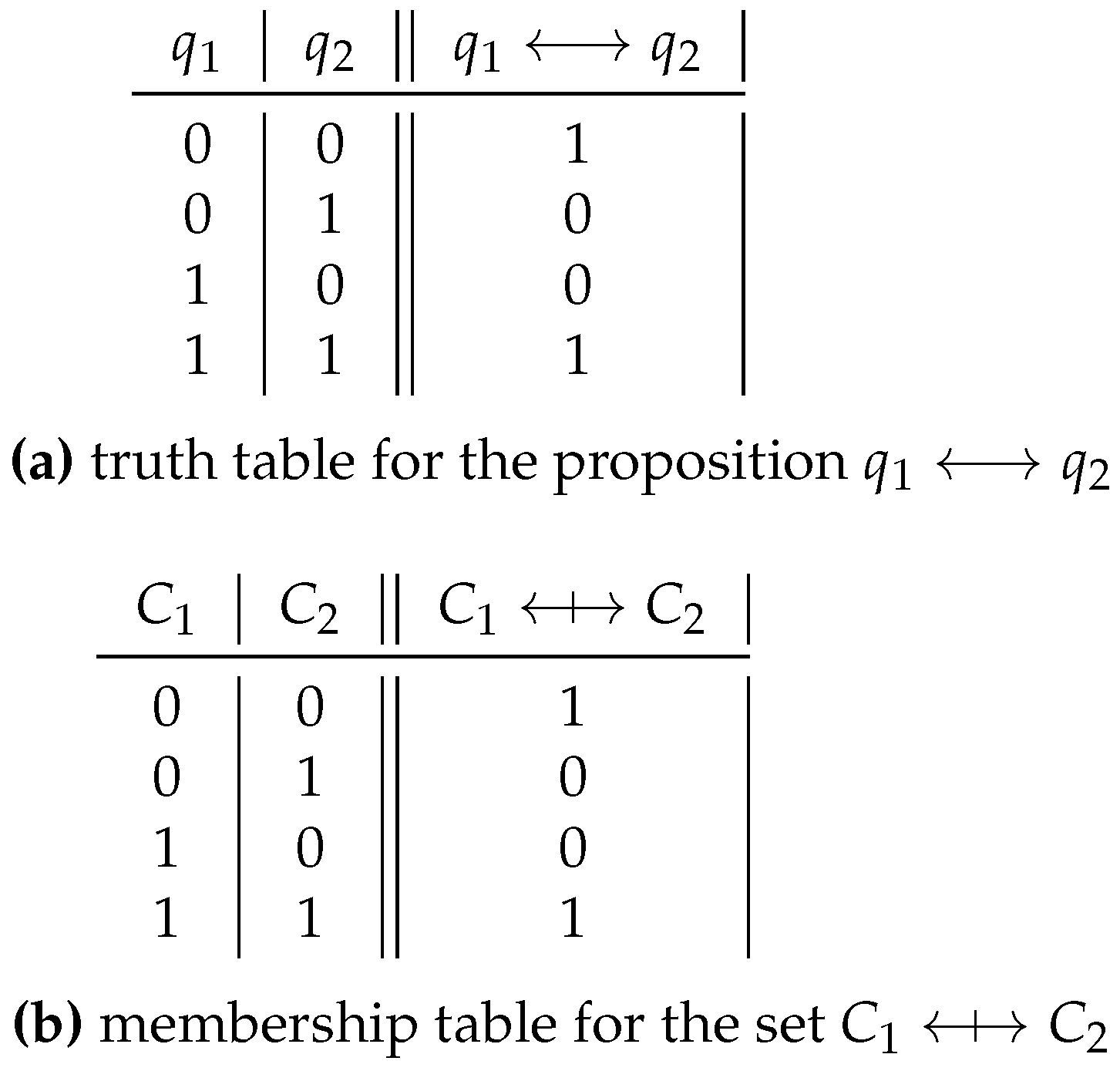

The operator of logical equivalence (or of material bi-implication) in propositional calculus will be symbolized as ⟷. The operator of membership bi-implication in set theory will be symbolized as

.

Figure 5 presents a) the truth table for the proposition

q1 ⟷

q2 (that is, “

q1 is logically equivalent to

q2”) and b) the membership table for the set

C1 ⇹

C2.

In the truth table for it is seen that the proposition is true in only two of the four possible cases: the cases in which and have the same truth value (that is, if both propositions are false or if both propositions are true). These cases are considered in rows 1 and 4 of the truth table. In the membership table for it is seen that any element belonging to the universal set considered belongs to the set only in two of the four possible cases: if that element belongs neither to the set nor to the set , or if that element belongs both to the set and to the set . These cases are considered in rows 1 and 4 of the membership table.

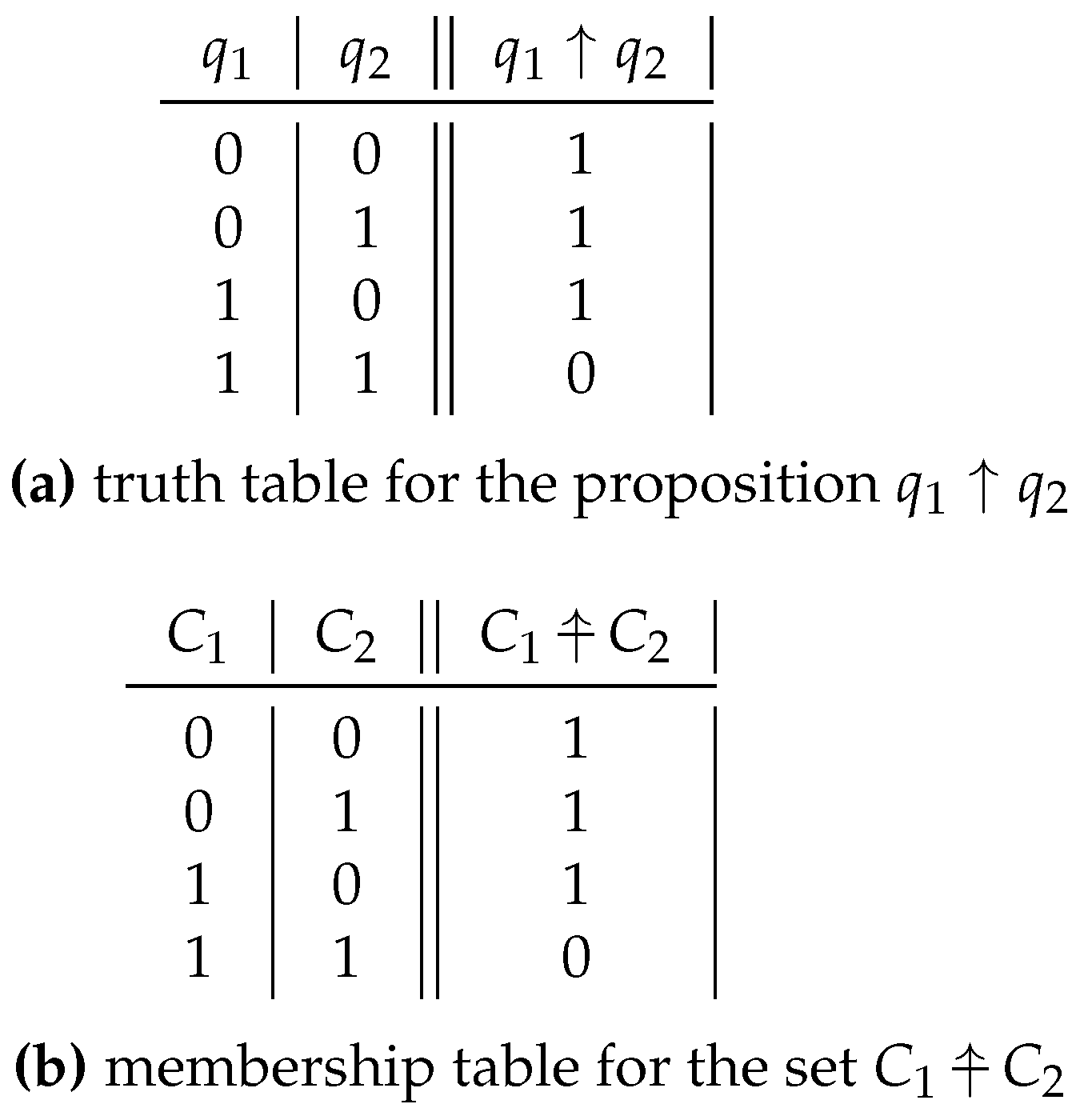

The Sheffer stroke operator – or NAND, the negation of the conjunction of two propositions

and

– will be symbolized as ↑. The Sheffer stroke operator in set theory will be symbolized as ↑.

Figure 6 represents a) the truth table for the proposition

, and b) the membership table for the set

↑

.

In the truth table for the proposition it is seen that in only one of four possible cases is the proposition false: that in which both and are true. In the membership table for ↑ it is seen that in only one of four possible cases, does any element whatsoever belonging to the universal set considered not belong to the set ↑: that in which that element belongs both to and to .

If the proposition is made to correspond to the set , the proposition is made to correspond to the set , the operator ↑ in propositional calculus to the operator ↑ in set theory – and therefore, to ↑ – it can be seen that the truth table for is isomorphic to the membership table for ↑. (Note that both tables are the same from a purely numerical viewpoint.)

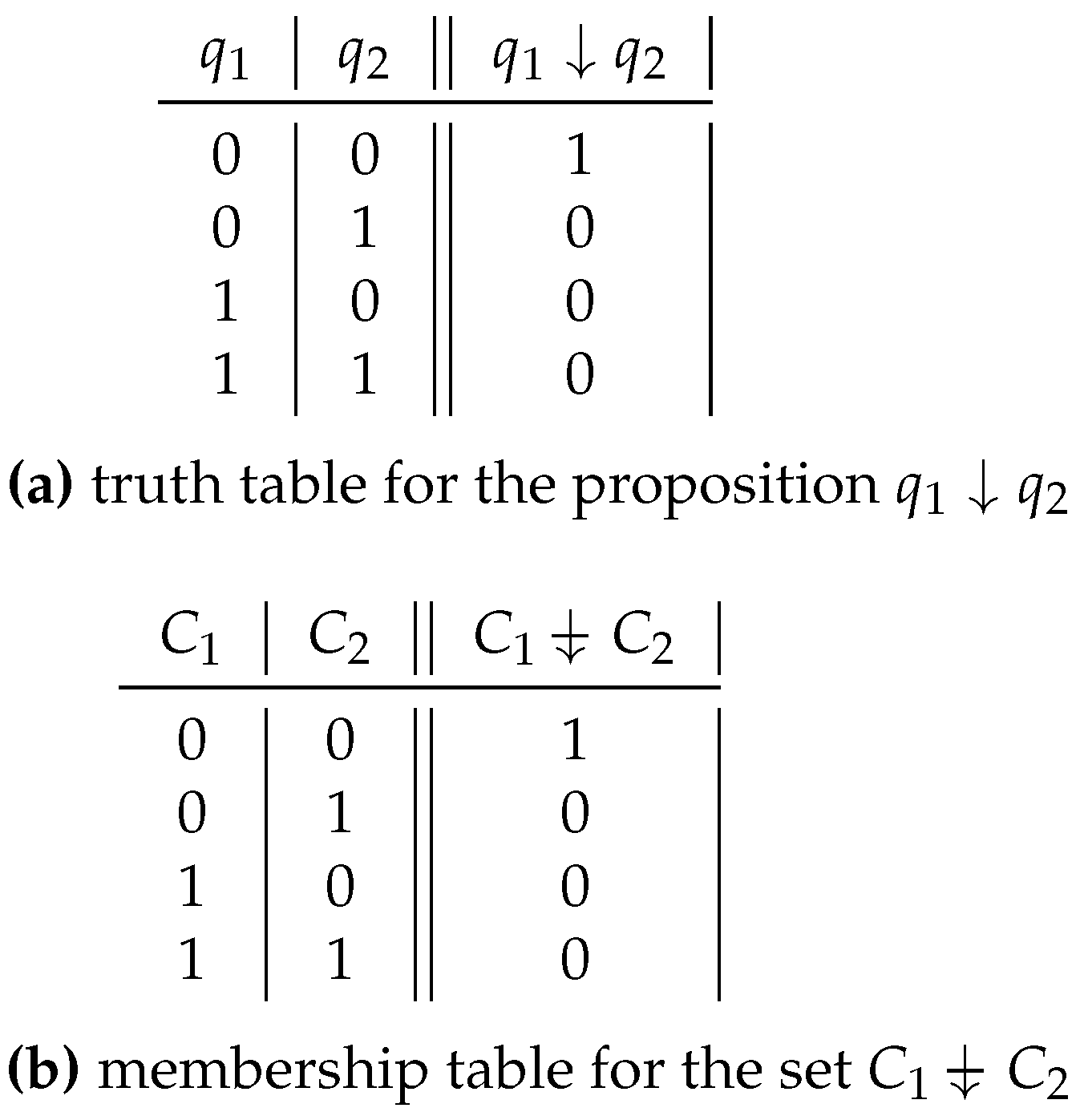

The operator Peirce’s arrow – or NOR, the negation of the inclusive disjunction of two propositions

and

– will be symbolized as

. The operator Peirce’s arrow in set theory will be symbolized as ↓.

Figure 7 presents a) the truth table for the proposition

and b) the membership table for the set

↓

.

In the truth table for the proposition it is seen that in only one of four possible cases is the proposition true: that in which both and are false. In the membership table for ↓ it is seen that in only one of four possible cases does any element whatsoever belonging to the universal set belong to the set ↓: that in which that element belongs neither to the set nor to the set .

If the proposition is made to correspond to the set , the proposition to correspond to the set , the operator ↓ in propositional calculus to the operator ↓ in set theory – and therefore, to ↓ – it can be seen that the truth table for is isomorphic to the membership table ↓. (Note that both tables are the same from a purely numerical viewpoint.)

3. Each Law – or Tautology – of Propositional Calculus Is Isomorphic to an Expression Corresponding to a Set Equal to the Universal Set Considered

Any proposition resulting from operations between n propositions, for , which is true because of its logical form, regardless of the truth value of each of those n propositions, is known as a law (or tautology) in propositional calculus.

In this section reference will be made to several laws (or tautologies) of propositional calculus. For each a specification will be given, according to section 2 above, of the corresponding set which is isomorphic to that law. A representation will be provided of 1) the truth table for that law and 2) the membership table for that set.

In each truth table it will be possible to note in the corresponding column that, regardless of the truth values of n propositions considered to construct it, the proposition that qualifies as a law is true. In each membership table it will be possible to note how, regardless of whether any element of the universal set considered belongs or not to one of the n sets considered to construct the set corresponding to that law – which is isomorphic to it – that element belongs to this latter set. Therefore, that set is equal to the universal set considered.

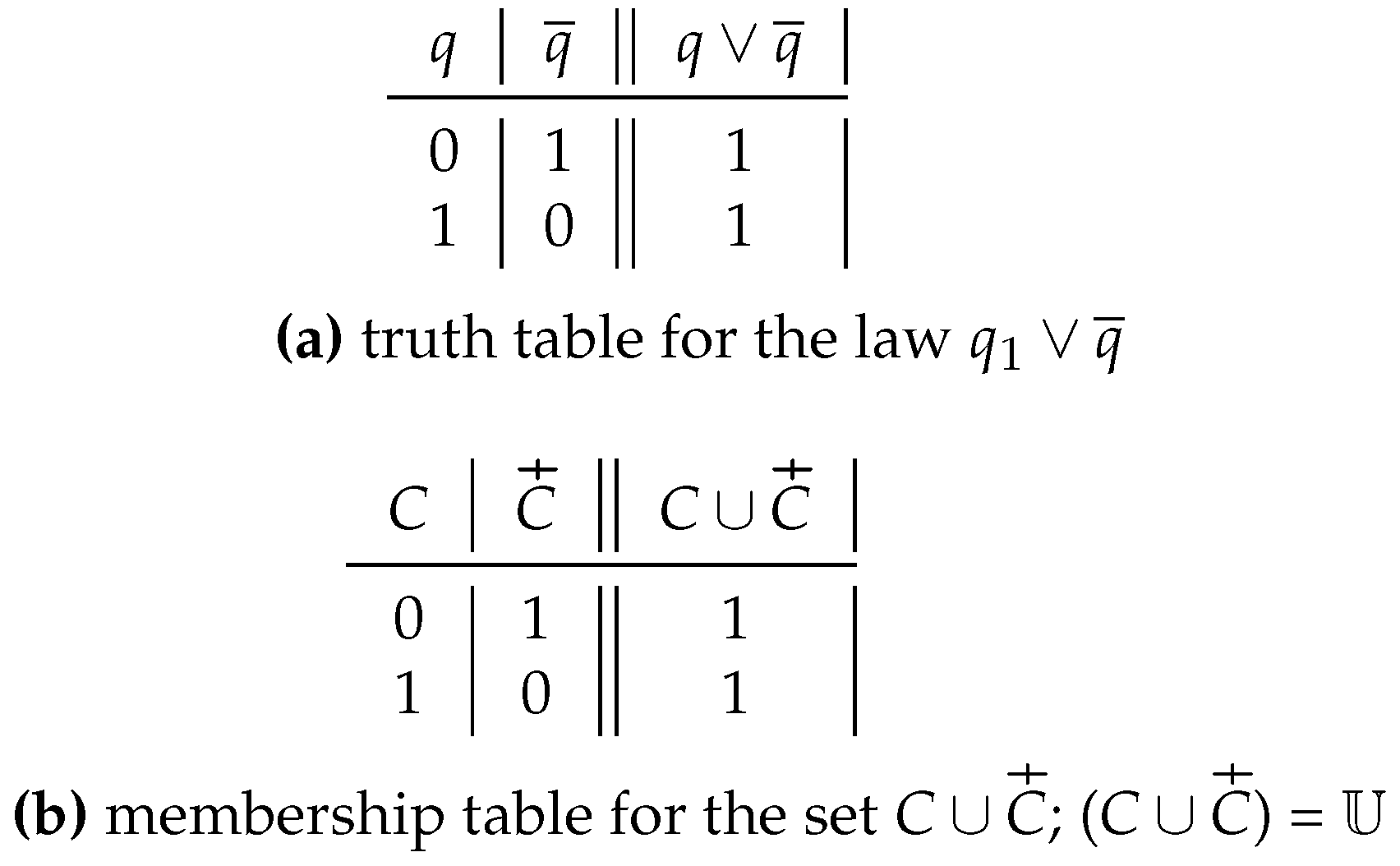

First of all consider in

Figure 8 the “law of the excluded middle”:

. In this case

.

The set corresponding to the law – or which is isomorphic to it – is the following: .

Consider in

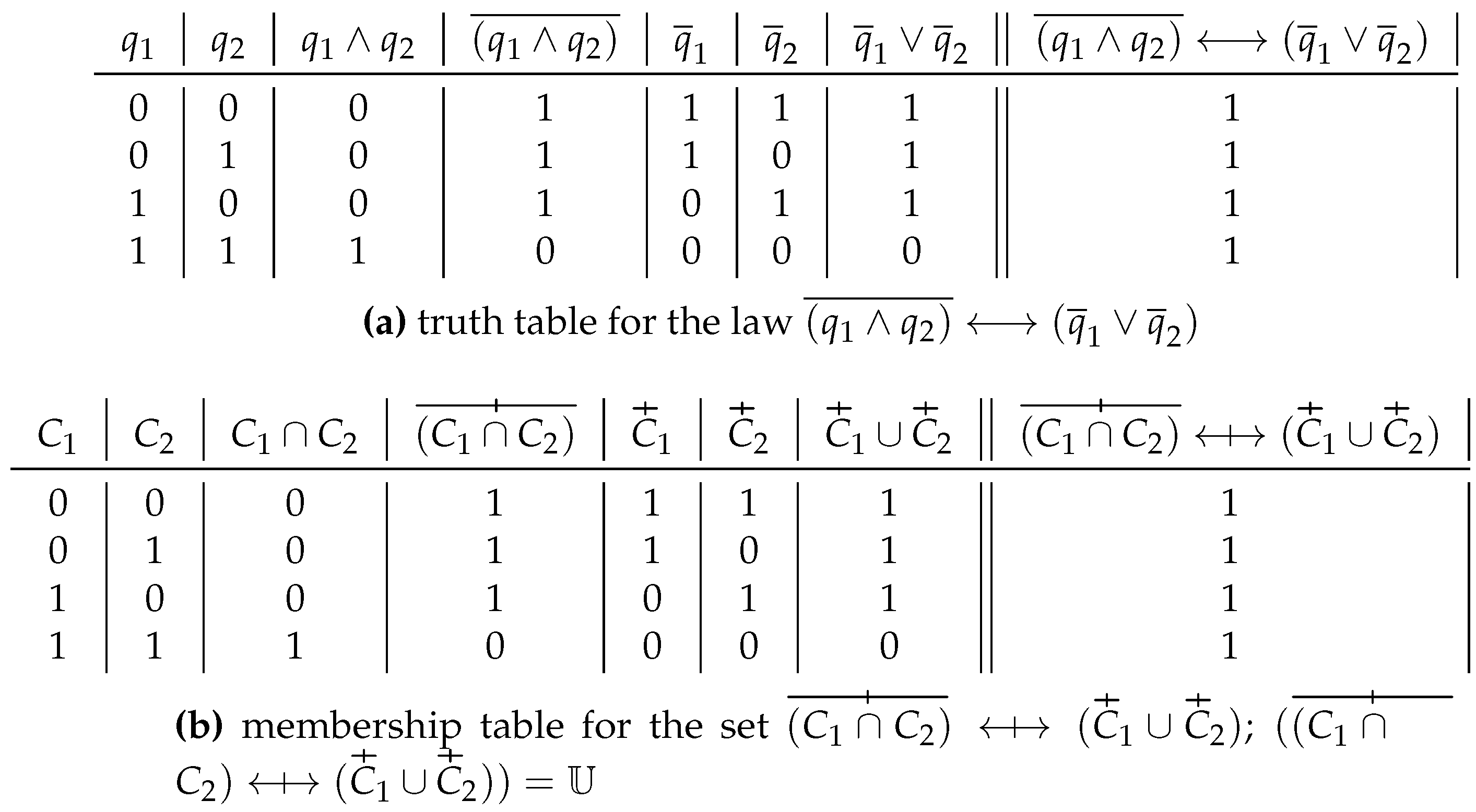

Figure 9 one of the De Morgan’s laws in propositional calculus:

. In this case

.

The set corresponding to the law – or which is isomorphic to it – is the following: .

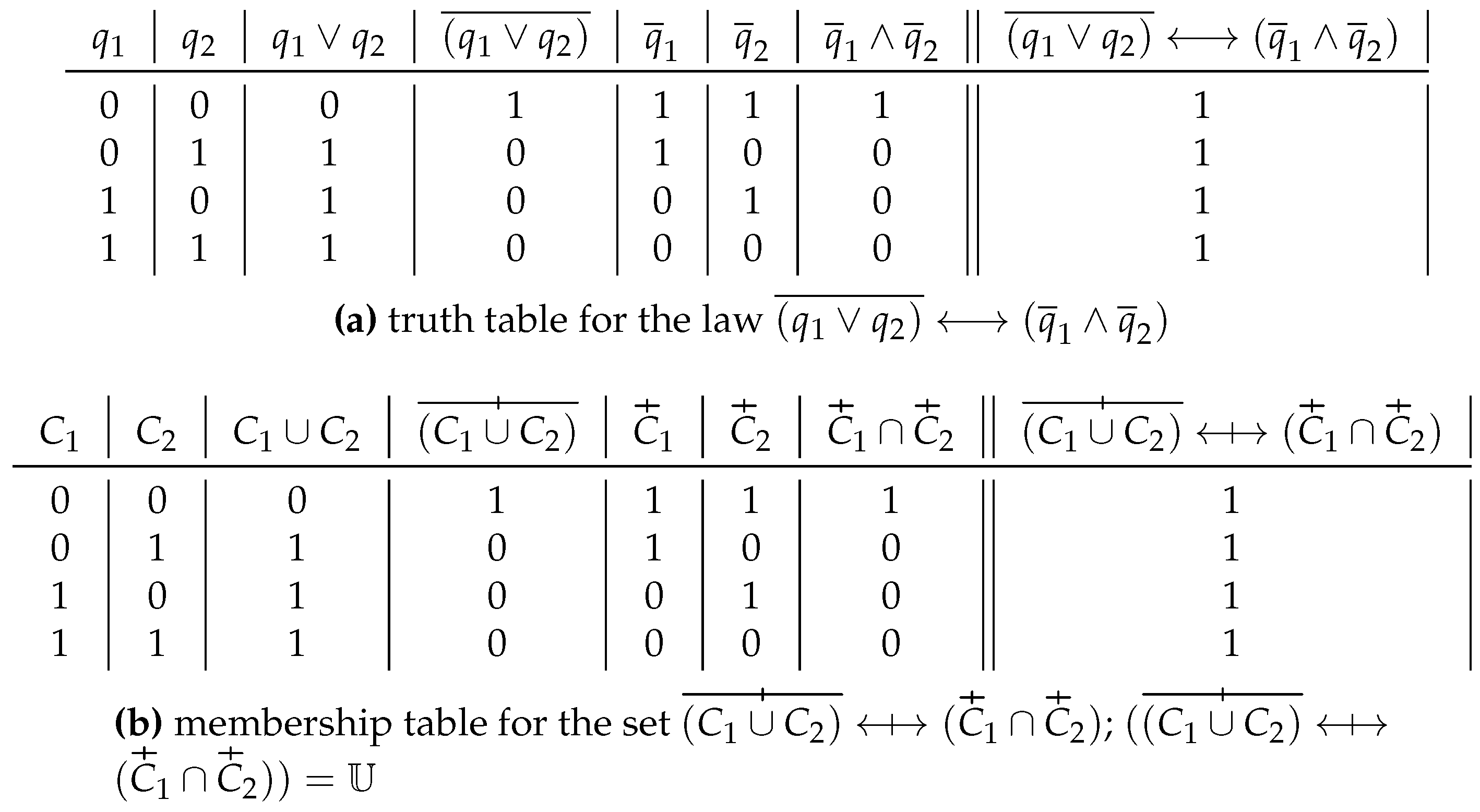

Consider in

Figure 10 another De Morgan’s law in propositional calculus:

. In this case

.

The set corresponding to the law – or which is isomorphic to it – is the following: .

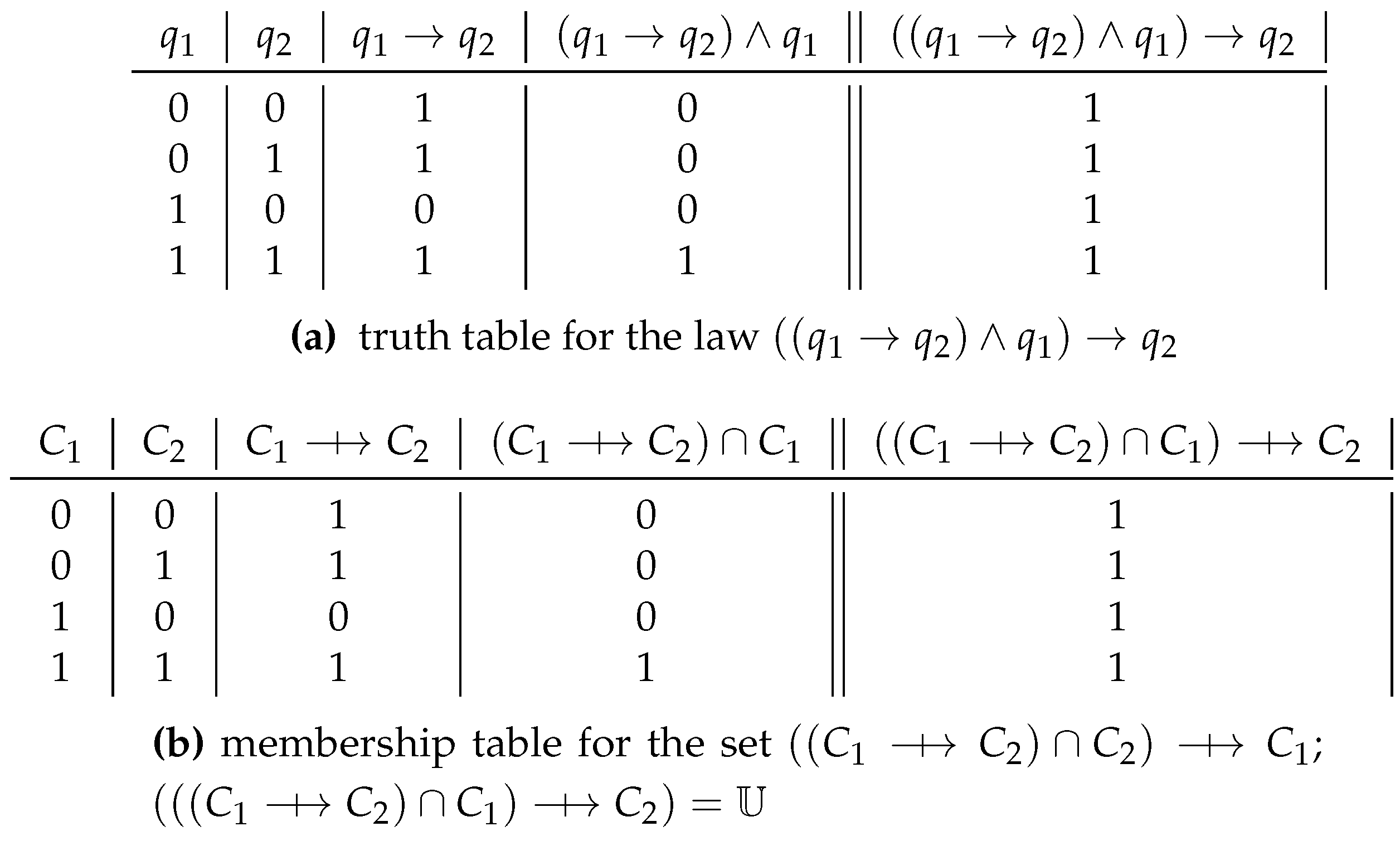

Consider in

Figure 11 the law of propositional calculus “modus ponendo ponens”:

. In this case

.

The set corresponding to the law – or which is isomorphic to it – is the following: C2) C1) ⇸ C2.

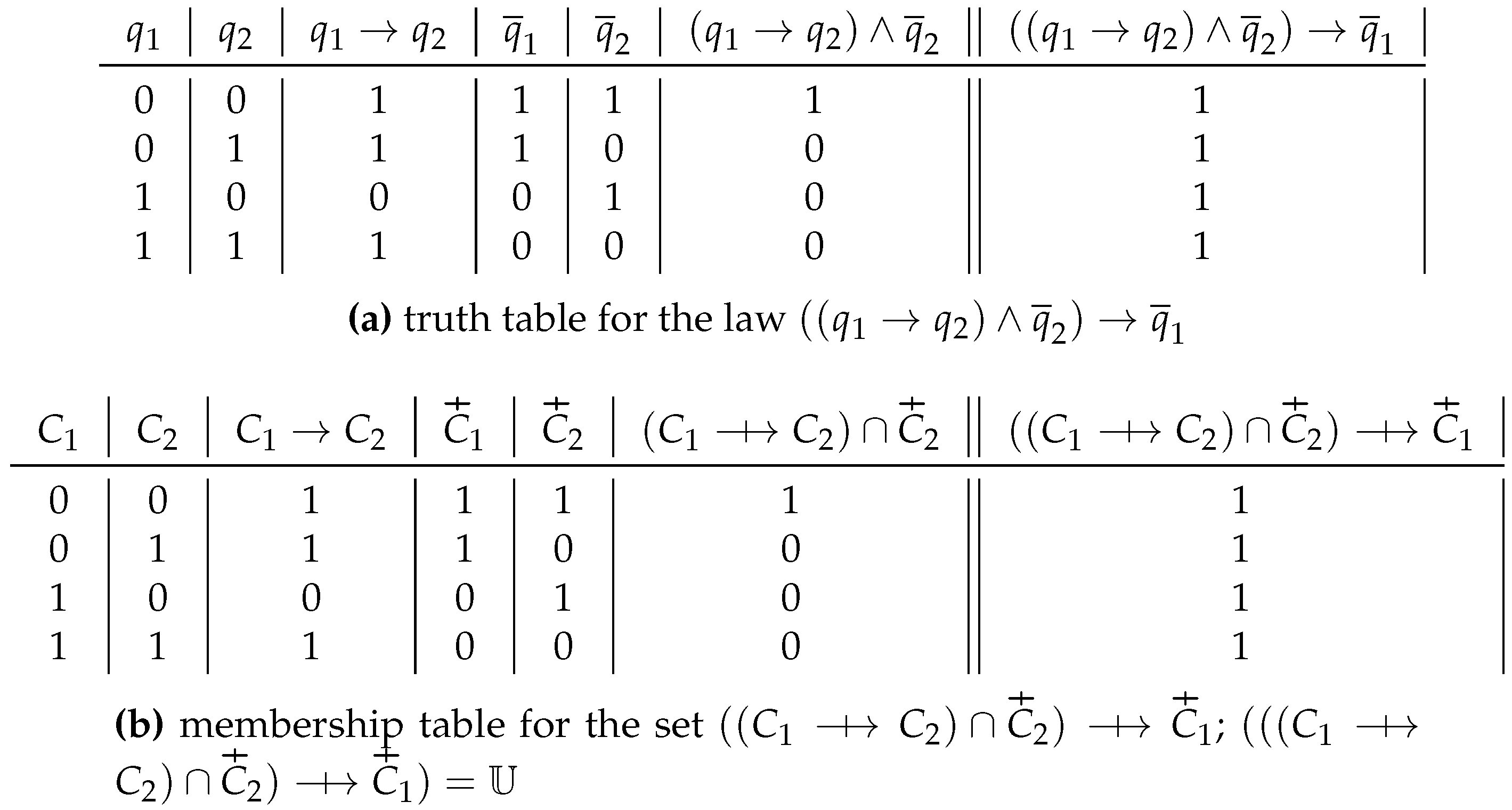

Consider in

Figure 12 the law of propositional calculus “modus tollendo tollens”:

. In this case

.

The set corresponding to the law – or which is isomorphic to it – is the following: .

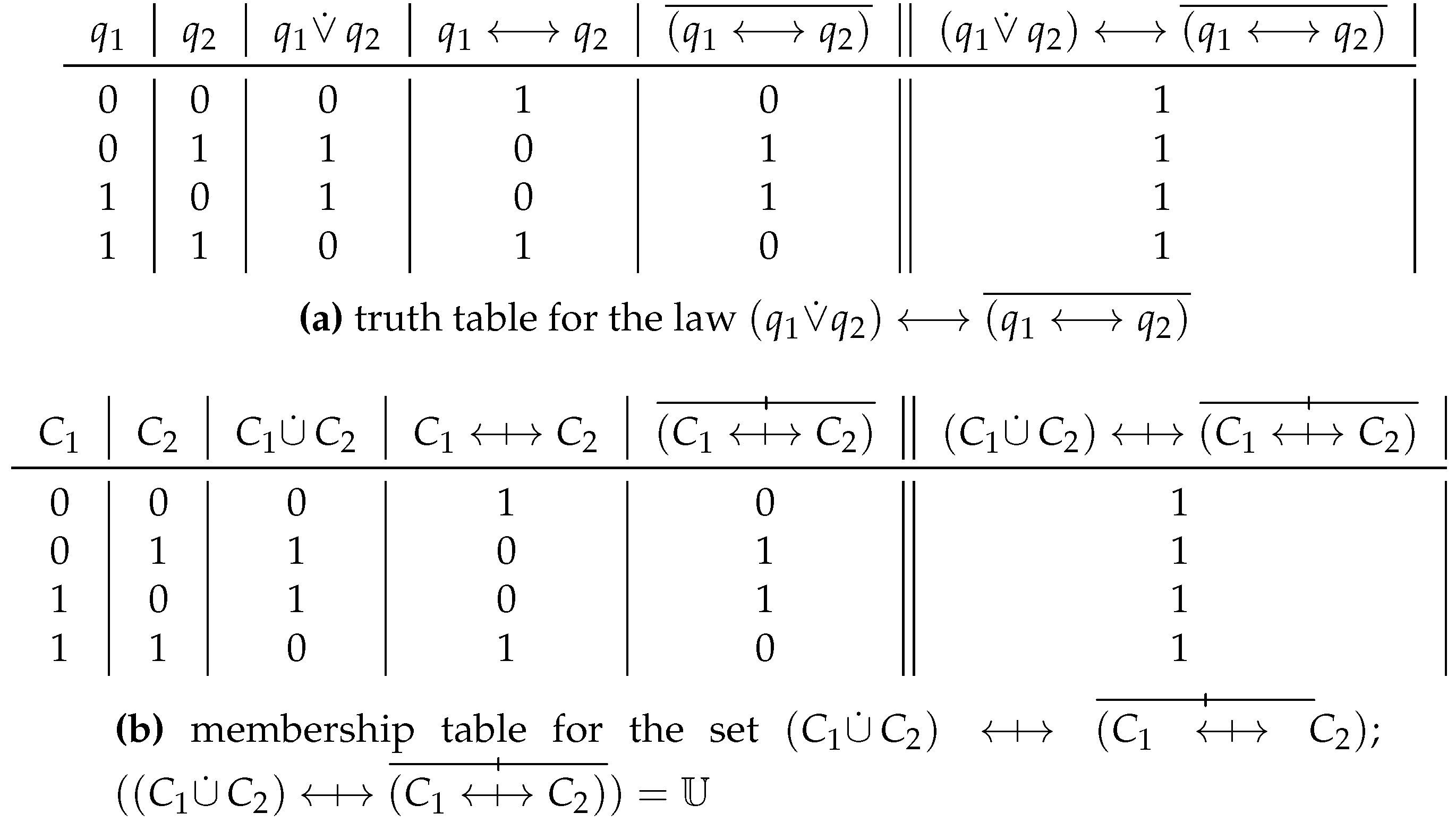

Consider in

Figure 13 the law

in propositional calculus. In this case

.

The set corresponding to the law – or which is isomorphic to it – is the following: .

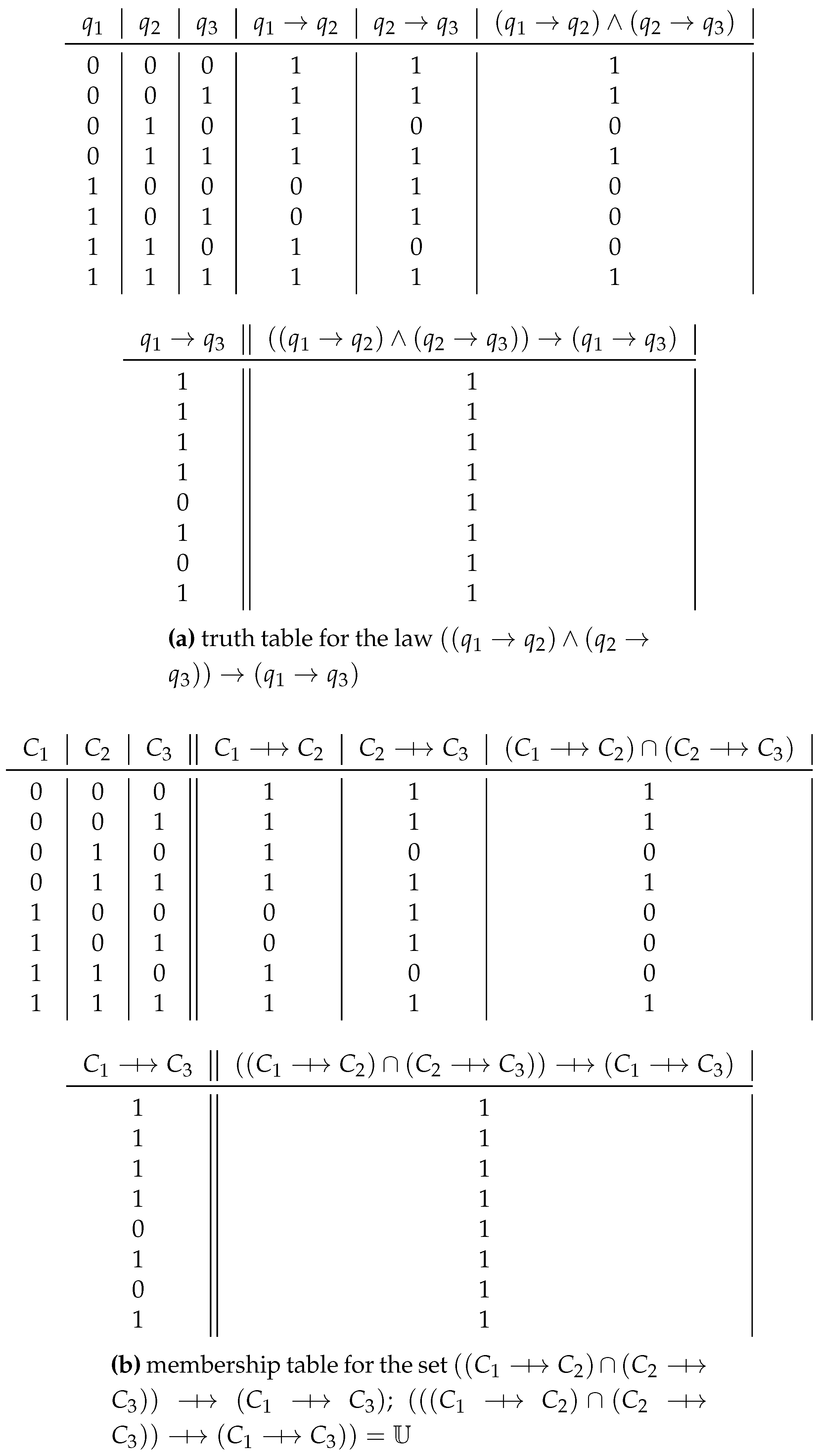

Consider in

Figure 14 the law of transitivity of material implication in propositional calculus:

. In this case

.

The set corresponding to the law – or which is isomorphic to it – is the following: C2) C2 ⇸ C3)) ⇸ (C1 ⇸ C3).