Submitted:

09 August 2024

Posted:

09 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

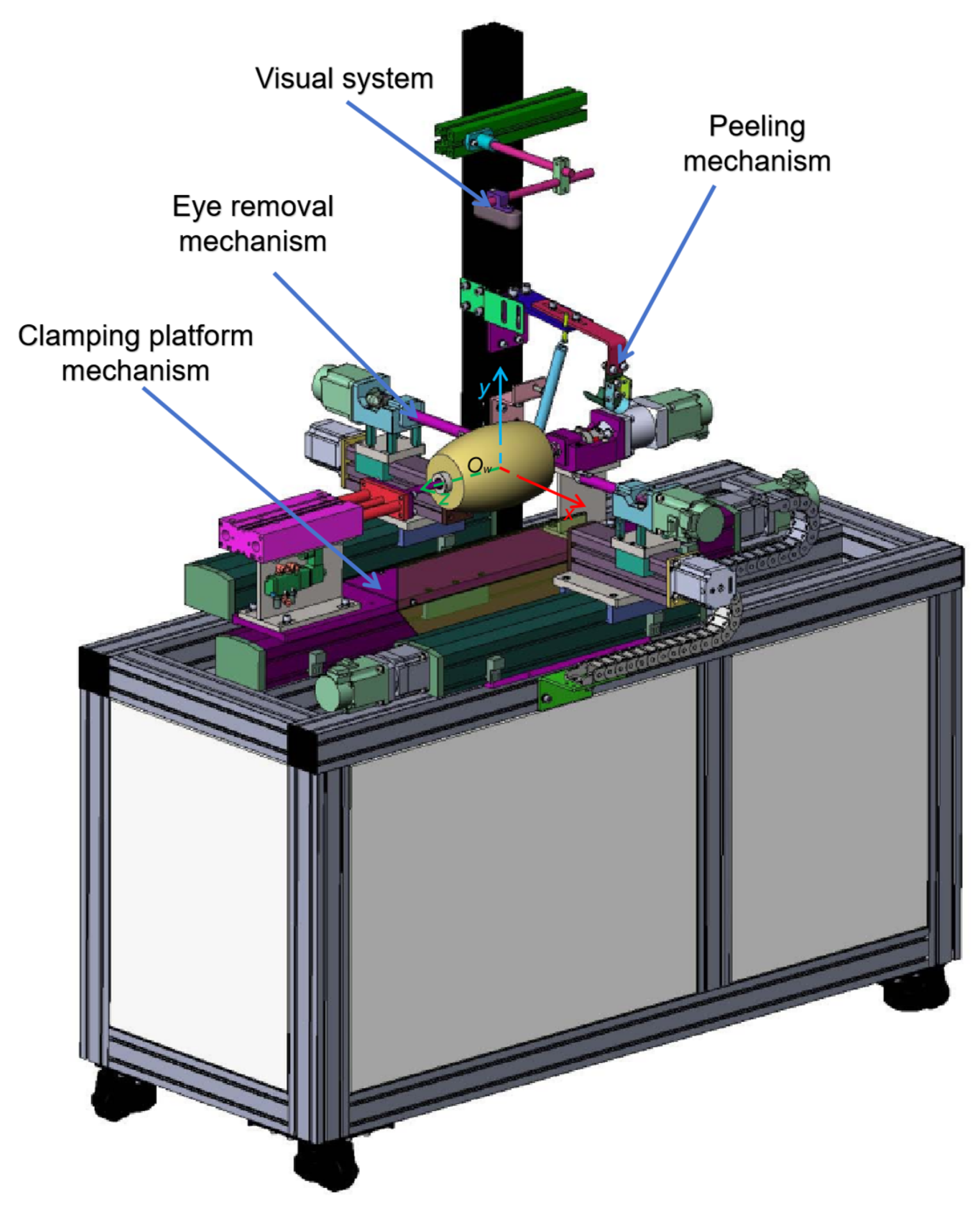

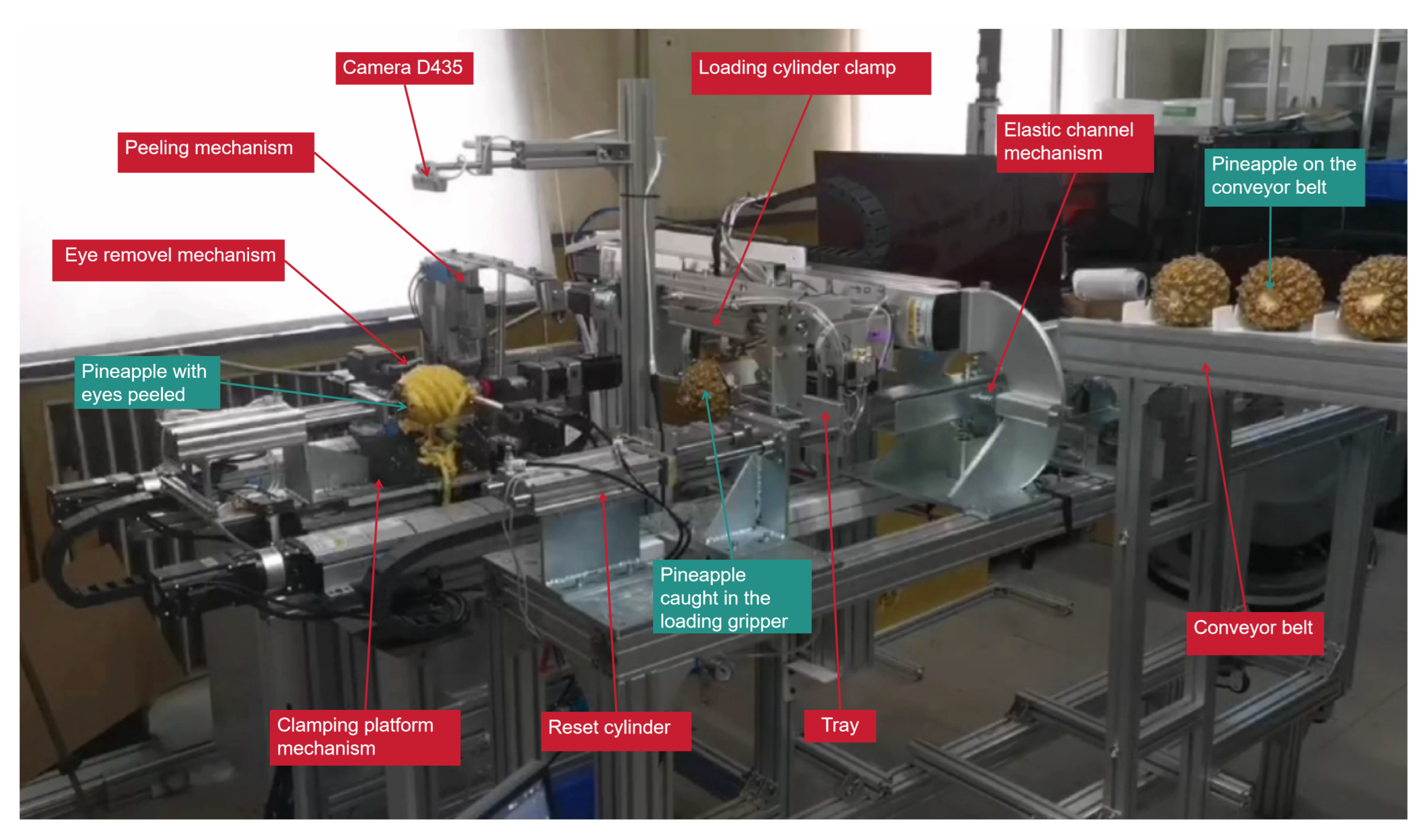

2. Materials and Methods

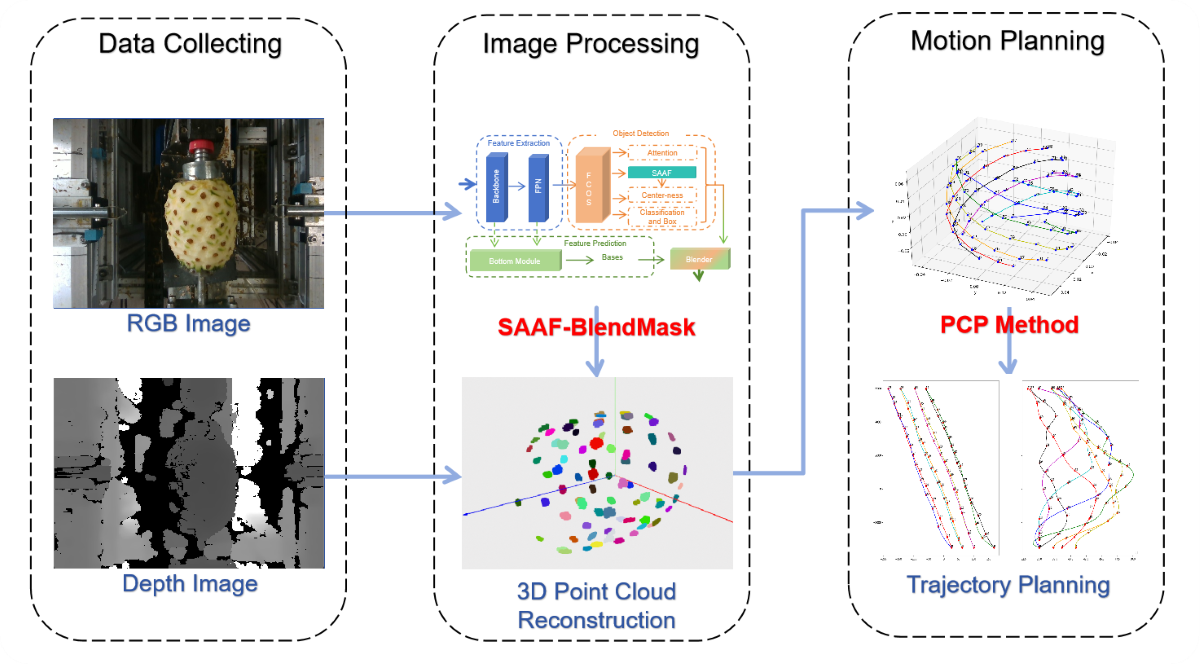

- (1)

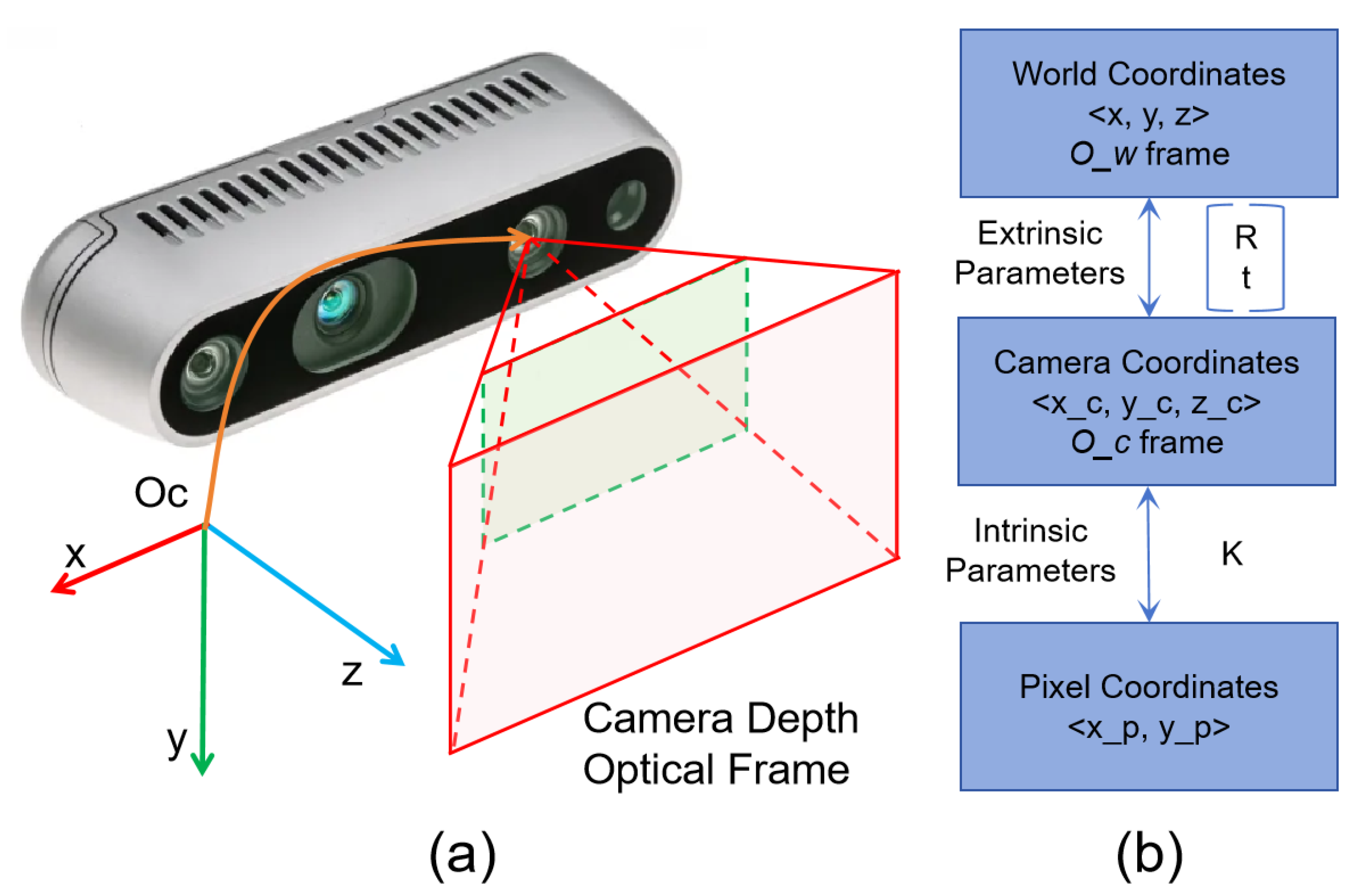

- Data collecting - employing RGB-D camera to uniformly capture six images of each peeled pineapple, comprising both RGB imagery and depth information;

- (2)

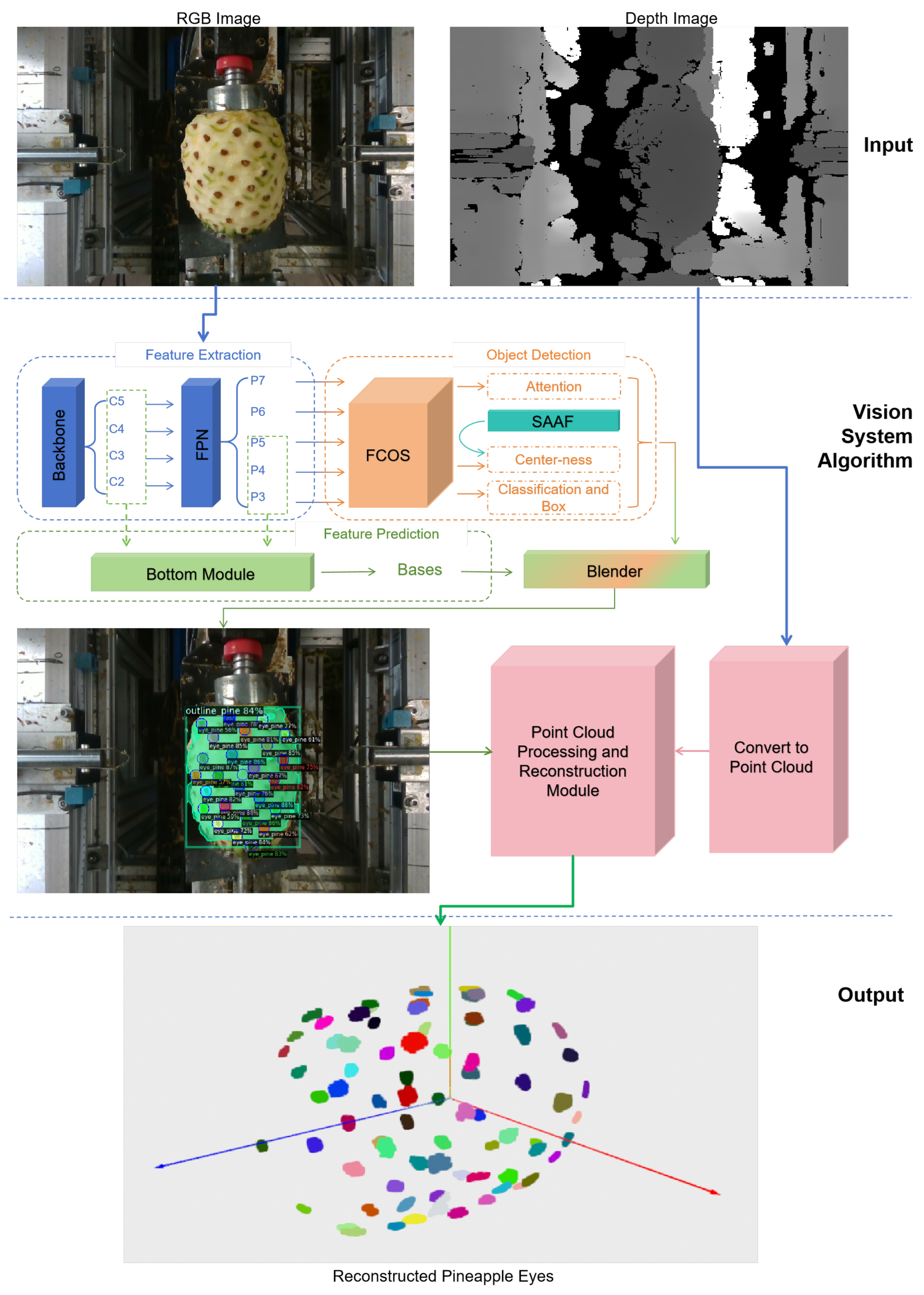

- Image processing - utilizing an improved BlendMask algorithm (SAAF-BlendMask) for the identification of pineapples and pineapple eyes, followed by the reconstruction of the point cloud distribution of pineapple eyes;

- (3)

- Motion planning - planning of cutting paths (PCP method) and trajectories based on the distribution of pineapple eyes and cutting the pineapple eyes following the planned trajectories.

2.1. Data Collecting

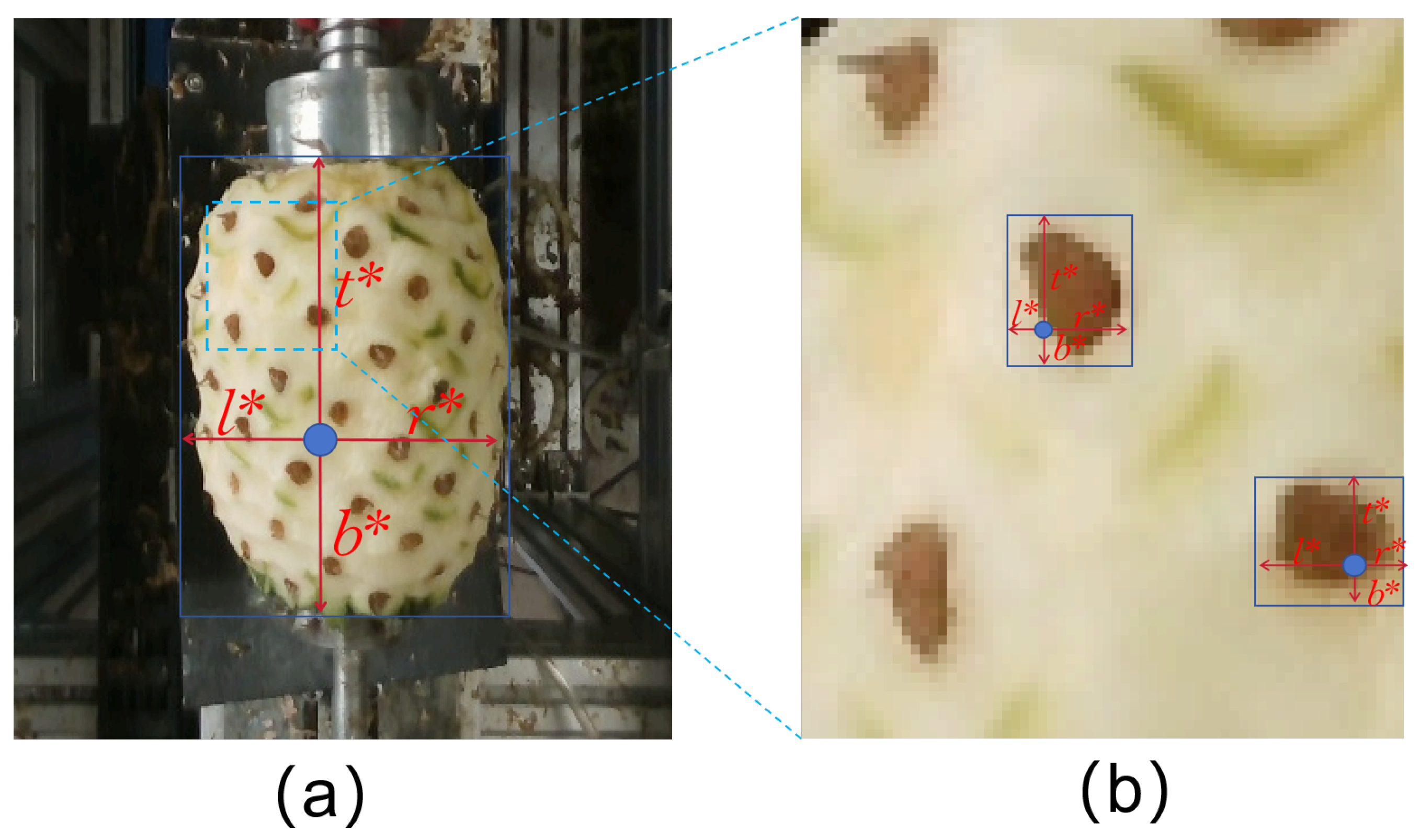

2.2. SAAF-BlendMask Algorithm

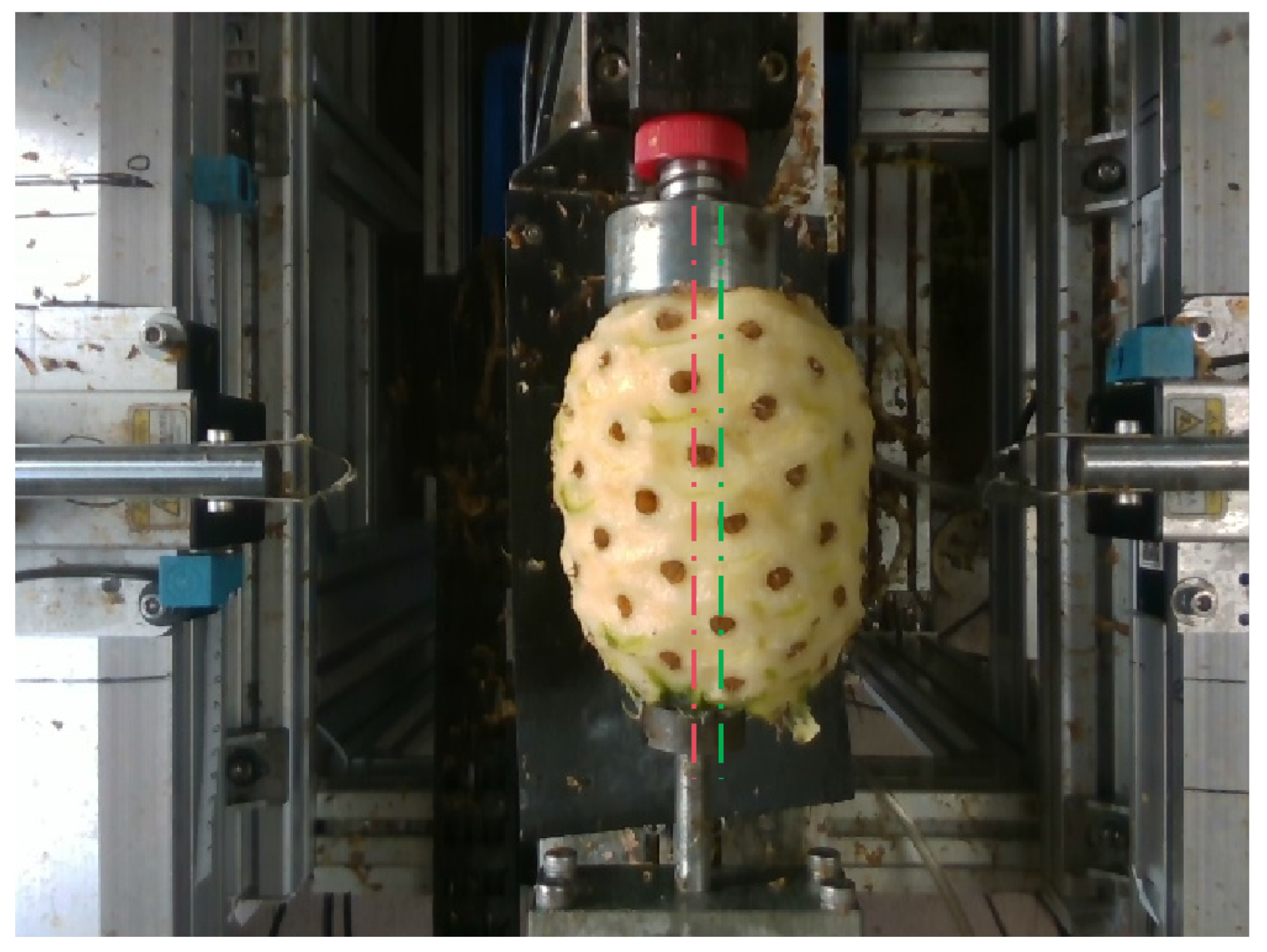

2.3. Pose Correction Planning (PCP) Method

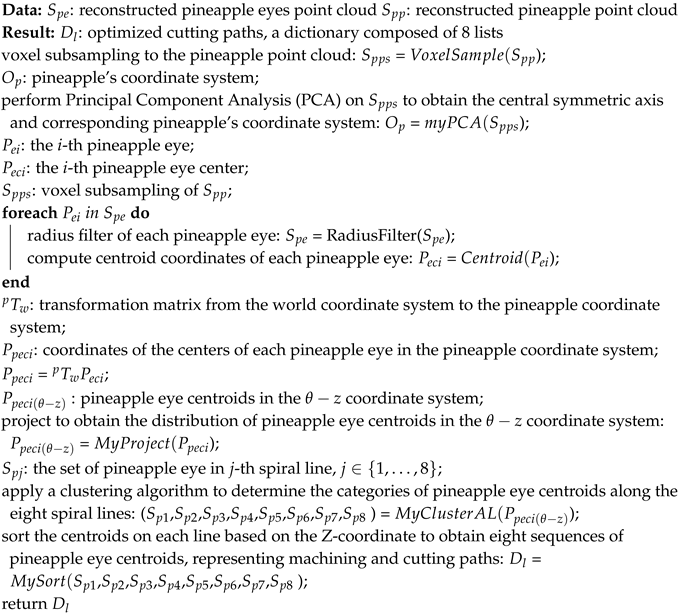

| Algorithm 1:PCP(Pose Correction Planning) Method |

|

- 1)

- Uniform sampling of the pineapple surface point cloud () yields a consistent and well-distributed point cloud () of the pineapple surface.

- 2)

- Use Principal Component Analysis () to determine the pose or coordinate system () of the pineapple.

- 3)

- Compute the centroid () of the pineapple eye surface point cloud obtained with previous sections of the paper.

- 4)

- Calculate the coordinates () of the point cloud centroid in the pineapple coordinate system.

- 5)

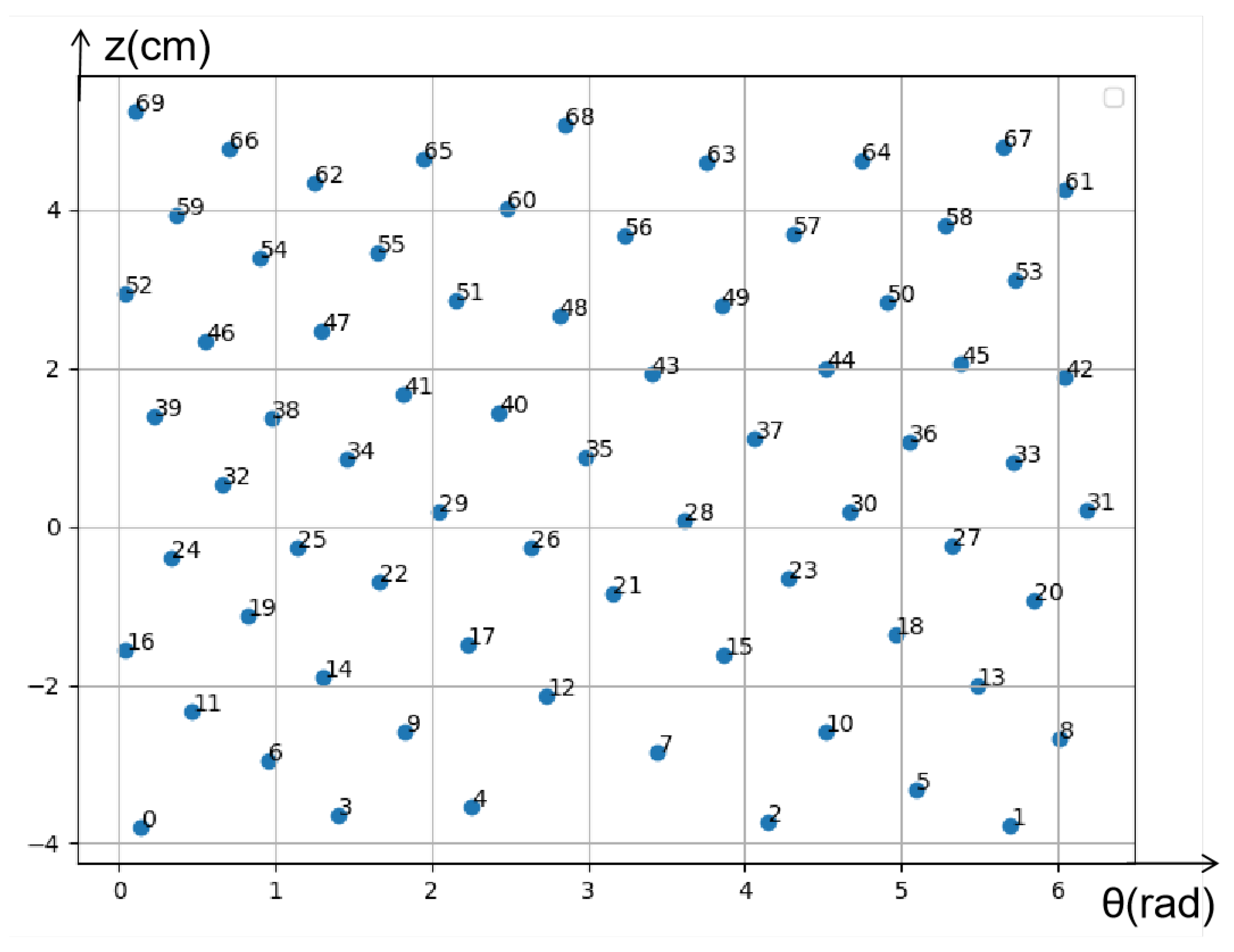

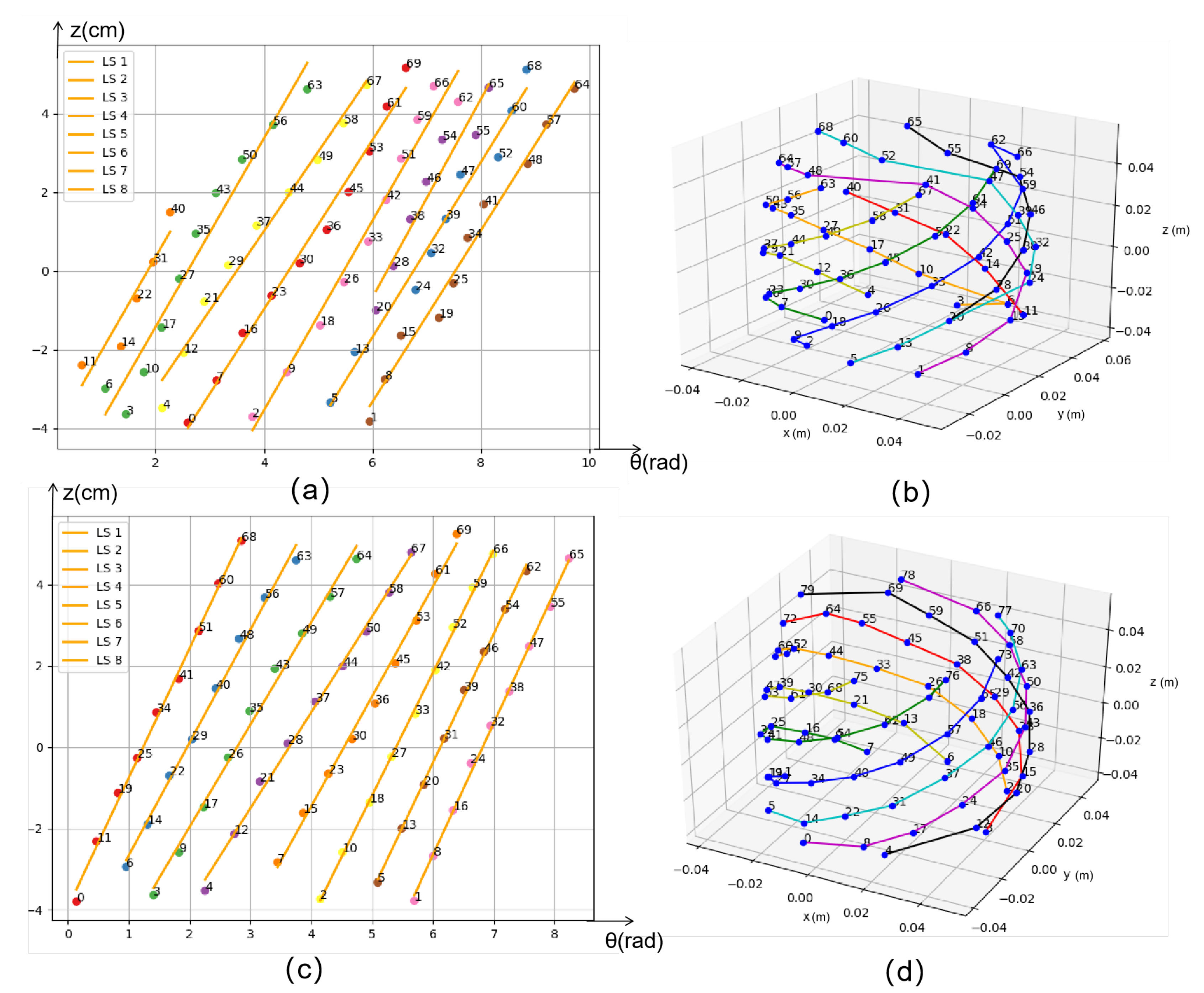

- The distribution of point cloud centroids () is transformed from the pineapple coordinate system to the radian-height coordinate system (), where the radian is the horizontal axis () and the is the vertical axis, as shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that the distribution of the pineapple eyes in this coordinate system is quite regular, with the pineapple eyes on the same spiral line essentially aligned in a straight line. Therefore, we thought of using clustering to distinguish the pineapple eyes on each spiral line.

- 6)

-

Since the distribution radian of the pineapple eyes range from 0 to , we first need to shift the pineapple eyes on the same spiral line before clustering. Assuming the slope of the straight line formed by the distribution of pineapple eyes is k, and the original coordinates of pineapple eyes are , the shifted coordinates are:Then we rotate the obtained by and calculate the value, ranges from to . The relationship between and k is as follows:The coordinates after rotation, , are:With each rotation, we perform clustering () to obtain 8 groups matrices (). Each element represents a pineapple eye, where j is the index of the spiral line (ranging from 1 to 8), and i is the number of pineapple eyes on each spiral line (ranging from 1 to ). If , then can be represented as . The cost function () is designed to evaluate the quality of a given scheme by penalizing the variance of different variables. Specifically:where, , and are hyperparameters that adjust the weight of each term in the overall cost function. represents the variance calculation. The calculation of is as follows:

- 7)

- In the mechanism coordinate system, sort the pineapple eyes on each helical line according to their Z-axis values to obtain an ordered set of pineapple eyes for each helical line. Connect the pineapple eyes on each helical line with line segments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Result Analysis of Pineapple Eyes Detection

3.2. Result Analysis of Pineapple Eyes Cutting Path Planning

3.3. Comparison of Different Pineapple Processing Methods

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohsin, A.; Jabeen, A.; Majid, D.; Allai, F.M.; Dar, A.H.; Gulzar, B.; Makroo, H.A. Pineapple. Antioxidants in fruits: Properties and health benefits, 2020, 379-396.

- Rohrbach, K.G.; Leal, F.; d’Eeckenbrugge G.C. History, distribution and world production. In The pineapple: botany, production and uses, 2003, 1-12.

- Jia, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, W.; Hou, S.; Ji, Z.; Liu, G.; Yin, X. Foveamask: A fast and accurate deep learning model for green fruit instance segmentation, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2021, 191, 106488. [CrossRef]

- Kasinathan, T.; Singaraju, D.; Uyyala, S.R. Insect classification and detection in field crops using modern machine learning techniques, Information Processing in Agriculture, 2021, 8, 446-457. [CrossRef]

- Koirala, A.; Walsh, K.B.; Wang, Z.; McCarthy, C. Deep learning-method overview and review of use for fruit detection and yield estimation, Computers and electronics in agriculture, 2019, 162, 219-234. [CrossRef]

- Indira, D.; Goddu, J.; Indraja, B.; Challa, V.M.L.; Manasa, B.A. review on fruit recognition and feature evaluation using cnn, Materials Today: Proceedings, 2023, 80, 3438-3443. [CrossRef]

- Shakya, D.S. Analysis of artificial intelligence based image classifica- tion techniques, Journal of Innovative Image Processing, 2020, 2, 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, D.; Gong, W.; Li, Z.; Lu, Q.; Yang, S. Food image recognition with convolutional neural networks, in Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 12th International Conference on Ubiquitous Intelligence and Computing and 2015 IEEE 12th International Conference on Autonomic and Trusted Computing and 2015 IEEE 15th International Conference on Scalable Computing and Communications and Its Associated Workshops (UIC-ATC-ScalCom),Beijing, China, 10-14 August 2015; pp.690-693.

- Matsuda, Y.; Hoashi, H.; Yanai, K. Recognition of multiple-food images by detecting candidate regions, in Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, Melbourne, Australia, 9-13 July 2012; pp.25-30.

- Liu, G.; Nouaze, J.C.; Touko Mbouembe, P.L.; Kim, J.H. Yolo-tomato: A robust algorithm for tomato detection based on yolov3, Sensors, 2020, 20, 2145. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement, arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767, 2018.

- Yu, Y.; Zhang K.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D. Fruit detection for strawberry harvesting robot in non-structural environment based on mask-rcnn, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2019, 163, 104846. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Doll´ar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn, in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22-29 October 2017; pp.2961-2969.

- Wang, X.A.; Tang, J; Whitty, M. Deepphenology: Estimation of apple flower phenology distributions based on deep learning, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2021, 185, 106123. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition, arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014.

- Chen, S.W.; Shivakumar, S.S.; Dcunha, S.; Das, J.; Okon, E.; Qu C.; Taylor, C.J.; Kumar, V. Counting apples and oranges with deep learning: A data-driven approach, IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 2017, 2, 781-788. [CrossRef]

- Kisantal, M.; Wojna, Z.; Murawski, J.; Naruniec, J.; Cho, K. Augmentation for small object detection, arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.07296, 2019.

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection, arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10934, 2020.

- Haris, M.; Shakhnarovich, G.; Ukita, N. Task-driven super resolution: Object detection in low-resolution images, in Proceeding of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing, Sanur, Bali, Indonesia, 8-12 December 2021; pp.387-395.

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, M.; Ghanem, B. Sod-mtgan: Small object detection via multi-task generative adversarial network, in Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8-14 September 2018; pp.206-221.

- Lin, T.-Y.; Doll´ar, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp.2117-2125.

- Singh, V.; Verma, D.K.; Singh, G. Development of pineapple peeler- cum-slicer, Pop. Kheti, 2013, 1, 21-24.

- Kumar, P.; Chakrabarti, D.; Patel, T.; Chowdhuri, A. Work-related pains among the workers associated with pineapple peeling in small fruit processing units of north east india, International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 2016, 53, 124-129. [CrossRef]

- Anjali, A.; Anjitha, P.; Neethu, K.; Arunkrishnan, A.; Vahid, P.A.; Mathew, S. M. Development and performance evaluation of a semi- automatic pineapple peeling machine, International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 2019, 8, 325-332. [CrossRef]

- Jongyingcharoen, J.S.; Cheevitsopon, E. Design and development of continuous pineapple-peeling machine. Agriculture and Natural Resources, 2022, 56, 979-986.

- Siriwardhana, P.G.A.L.; Wijewardane, D.C. Machine for the pineapple peeling process, Journal of Engineering and Technology of the Open University of Sri Lanka (JET-OUSL), 2018, 6, 1-15.

- Kumar, P.; Chakrabartiand, D. Design of pineapple peeling equipment, in Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Conference on Advanced Production and Industrial Engineering, Delhi, India, 18-19 June 2021; pp.545-556.

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. Fcos: Fully convolutional one- stage object detection, in Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Korea (South), 27 October-2 November 2019; pp.9627-9636.

- Chen, H.; Sun, K.; Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Huang, Y.; Yan, Y. Blendmask: Top-down meets bottom-up for instance segmentation, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13-19 June, 2020; pp.8573-8581.

- Ekern, P.C. Phyllotaxy of pineapple plant and fruit, Botanical Gazette, 1968, 129, 92-94.

- Hikal, W.M.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Said-Al Ahl, H.A.; Bratovcic, A.; Tkachenko, K.G.; Kacaniov´a, M.; Rodriguez, R.M. Pineapple (ananas comosus l. merr.), waste streams, characterisation and valorisation: An overview, Open Journal of Ecology, 2021, 11, 610-634. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, D.P.; Hawkins. R.A.; Lopez. J.A. Hawaii pineapple: the rise and fall of an industry, HortScience, 2012, 47, 1390- 1398. [CrossRef]

- Liu. A.; Xiang. Y.; Li. Y.; Hu. Z.; Dai. X.; Lei. X.; Tang. Z. 3d positioning method for pineapple eyes based on multiangle image stereo- matching, Agriculture, 2022, 12, 2039. [CrossRef]

| m | n | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APs | APl | infer time(ms) |

| 1 | 20 | 72.34 | 94.17 | 82.31 | 62.05 | 83.19 | 0.020311 |

| 10 | 20 | 72.33 | 94.48 | 80.68 | 60.72 | 83.94 | 0.020599 |

| 20 | 20 | 74.27 | 94.95 | 82.47 | 62.44 | 86.11 | 0.020481 |

| 30 | 20 | 73.37 | 94.96 | 82.71 | 61.82 | 84.92 | 0.01985 |

| 1 | 30 | 73.04 | 95.44 | 83.62 | 62.54 | 83.56 | 0.020537 |

| 10 | 30 | 72.10 | 92.25 | 82.87 | 62.35 | 82.25 | 0.020342 |

| 20 | 30 | 70.83 | 92.78 | 81.74 | 62.69 | 79.00 | 0.020744 |

| 30 | 30 | 70.57 | 91.86 | 81.29 | 62.56 | 78.24 | 0.020971 |

| Methods | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APs | APl | infer time(ms) |

| Mask-RCNN | 72.85 | 92.69 | 81.77 | 62.29 | 83.42 | 0.053034 |

| BlendMask | 70.26 | 94.41 | 77.59 | 56.55 | 83.96 | 0.019867 |

| SAAF-BlendMask(Ours) | 73.04 | 95.44 | 83.62 | 62.54 | 83.56 | 0.020537 |

| Weight Group (kg) | < 1.2 | 1.2 - 1.7 | 1.7 - 2.2 | > 2.2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pineapples | 22 | 62 | 19 | 7 | 110 |

| Total Weight (kg) | 22.65 | 92.51 | 37.41 | 17.16 | 169.73 |

|

Peeling Waste with Our Method (kg) |

5.68 | 22.34 | 8.79 | 3.97 | 40.78 |

|

Peeling Waste with Traditional Method (kg) |

6.34 | 24.92 | 10.14 | 4.78 | 46.18 |

| Methods | IS | LLC | LFW | EP | AIM | EM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Full Manual Processing [22,24] |

à | à | à | à | à | |

|

Automatic Processing [32] |

à | à | ||||

|

Semi-auto Peeling[25] |

à | à | à | à | à | |

|

Spiral Peeling Processing [26] |

à | à | à | à | à | |

|

Visual Recognition Pineapple Eyes[33] |

à | à | à | à | à | |

| Ours |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).