Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

09 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collection

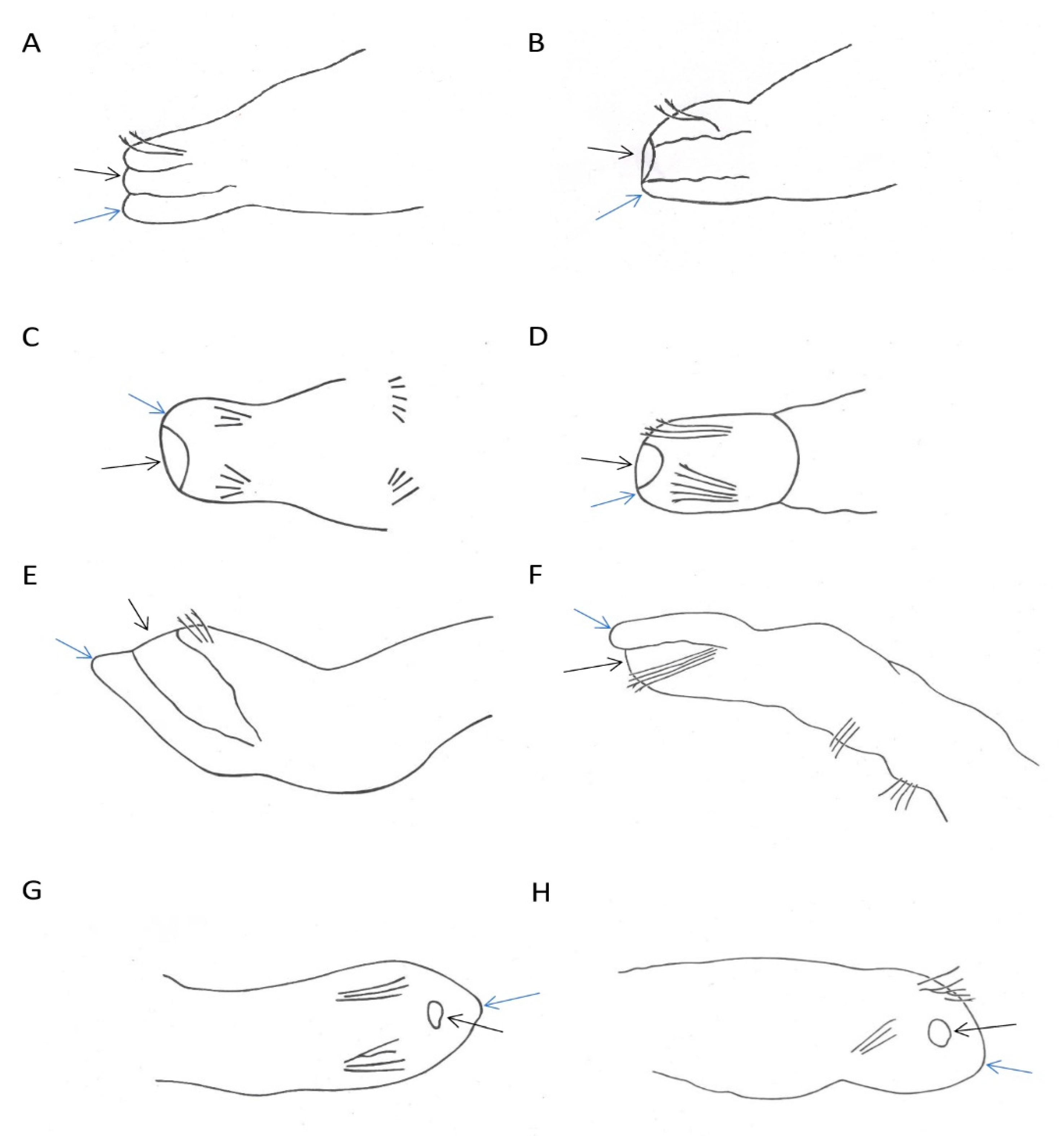

2.2. Morphological Analysis

2.3. Molecular Analyses

2.3.1. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

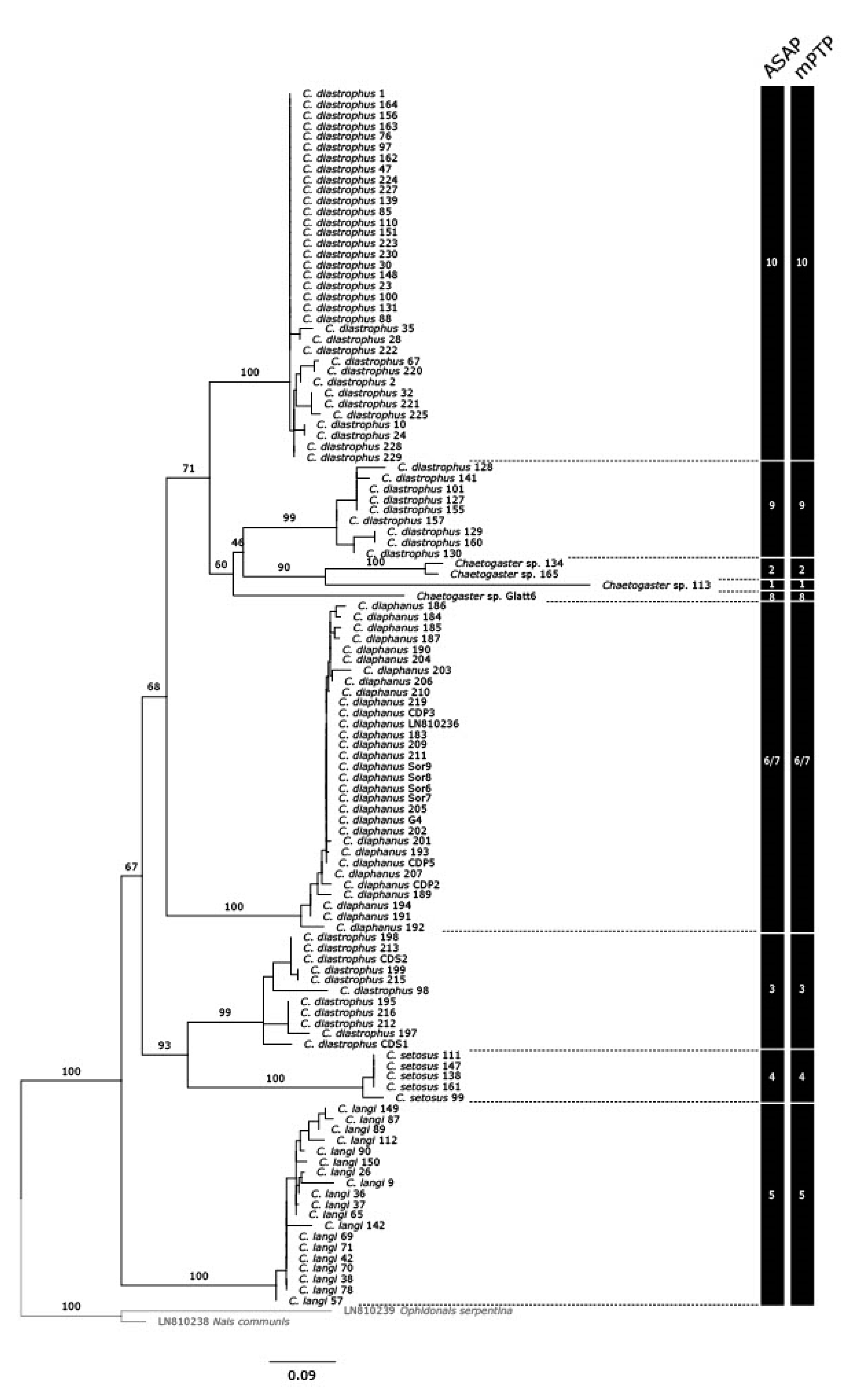

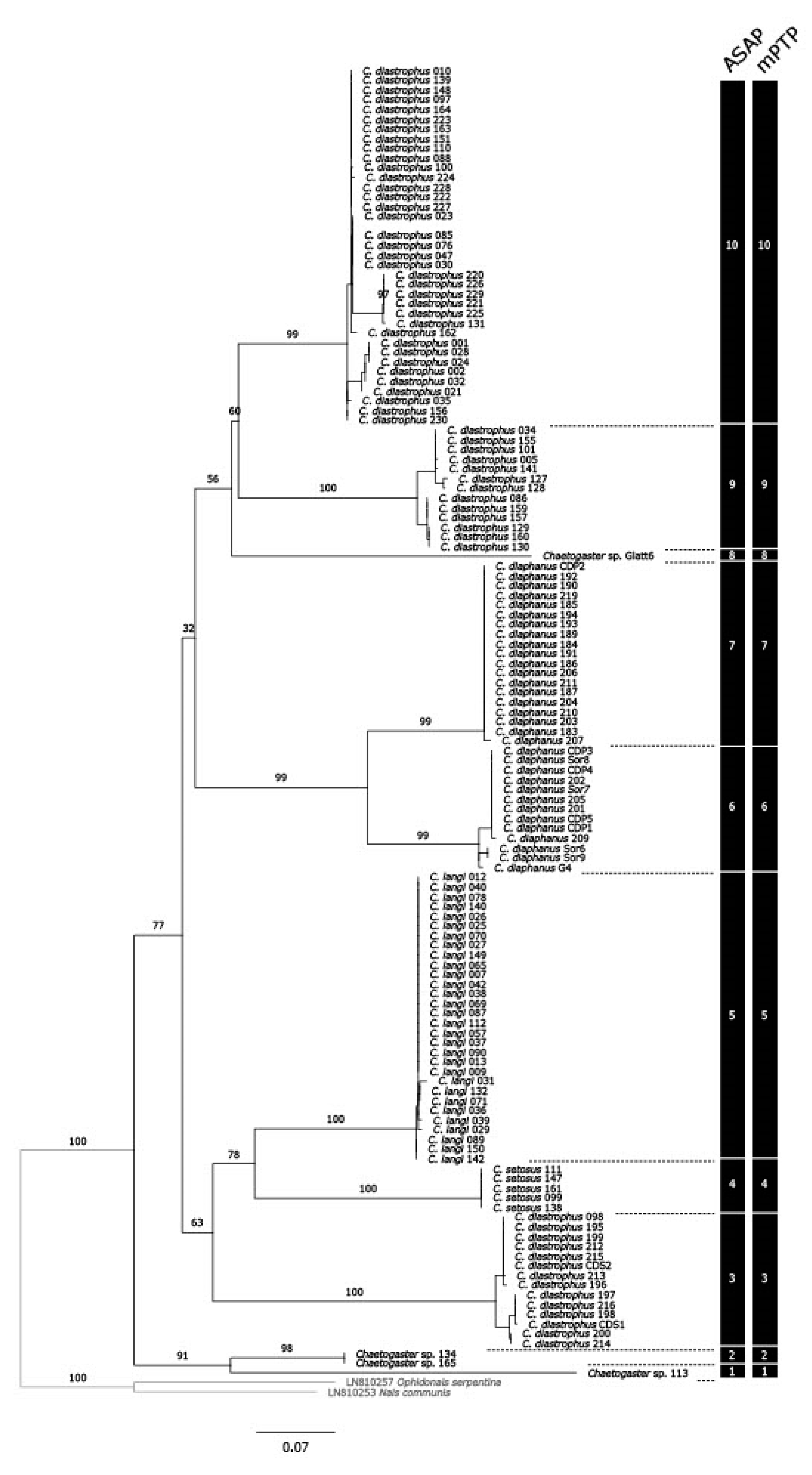

2.3.2. Molecular Phylogeny

2.3.3. Distance Analysis

2.3.4. Single-Locus Species Delimitation

3. Results

3.1. Delimitation of Lineages

3.2. Distance Analyses

3.3. Morphological vs. Molecular Identifications

3.4. Taxonomy

| Morphospecies/group | New species name | Geographical coordinates | Material preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chaetogaster diaphanus MOTUs 6-7 | Isolates Sor6-9: 46.522661oN, 6.573581oE; Isolate G4: 47.419157oN, 9.195899oE; Isolates CDP1-5, No 201-207, 209-211, 219, No 183-187, 189-194: 47.305217oN, 8.327193oE |

DNA voucher of the 32 specimens stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of 31 specimens (all except No 204) preserved (mounted on slides) in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles Lausanne | |

| Chaetogaster diastrophus MOTU10 |

Chaetogaster communis sp. nov. Vivien, Lafont & Martin |

Isolates No 1, 2, 10, 21: 47.419157oN, 9.195899oE; Isolates No 23, 24, 28, 30, 32, 35, 47, 76, 85: 47.414825oN, 9.198461oE; Isolates No 88, 97, 100, 110, 131, 139, 148, 151, 156, 162, 163, 164: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE; Isolates No 220-230: 47.43167oN, 9.17485oE |

Holotype and paratypes: DNA voucher of the 36 specimens stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of 35 specimens (all except No 30) preserved (mounted on slides) in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles of Lausanne |

| Chaetogaster diastrophus MOTU3 | Chaetogaster fluvii sp. nov. Vivien, Lafont & Martin | Isolates CDS1, CDS2, No 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216: 47.305217oN, 8.327193oE; Isolate No 98: 47.152502oN, 7.014924oE |

Holotype and paratypes: DNA voucher of the 14 specimens stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of the 14 specimens preserved (mounted on slides) in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles of Lausanne |

| Chaetogaster diastrophus MOTU9 |

Chaetogaster fluminis sp. nov. Vivien, Lafont & Martin |

Isolates No 5: 47.419157oN, 9.195899oE; Isolates No 34, 86: 47.414825oN, 9.198461oE; Isolate No 101: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE Isolates No 127, 128, 129, 130 46.522661oN, 6.573581oE; Isolates No 141, 155, 157, 159, 160: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE |

Holotype and paratypes: DNA voucher of the 13 specimens stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of 12 specimens (all except No 155) preserved (mounted on slides) in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles of Lausanne |

| Chaetogaster sp. MOTU1 | Chaetogaster suzensis sp. nov. Vivien, Lafont & Martin | Isolate No 113: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE | Holotype: DNA voucher of the specimen stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of the specimen (mounted on a slide) preserved in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles of Lausanne |

| Chaetogaster sp. MOTU2 | Chaetogaster sorgensis sp. nov. Vivien, Lafont & Martin | Isolate No 134: 46.522661oN, 6.573581oE; Isolate No 165: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE |

Holotype and paratype: DNA voucher of the 2 specimens stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of the 2 specimens preserved (mounted on slides) in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles of Lausanne |

| Chaetogaster sp. MOTU8 | Isolate Glatt6: 47.43167oN, 9.17485oE | DNA voucher of the specimen (Glatt 6) stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne | |

| Chaetogaster langi MOTU5 | Isolates No 7, 9, 12, 13: 47.419157oN, 9.195899 oE; Isolates No 25, 26, 27, 29, 31, 36-40, 42, 57, 65, 69-71, 78: 47.414825oN, 9.198461oE; Isolates No 87, 89, 90, 112: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE; Isolate No 132: 46.522661oN, 6.573581oE; Isolates No 140, 142, 149, 150: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE |

DNA voucher of the 30 specimens stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of 27 specimens (all except No 29, 37 and 38) preserved (mounted on slides) in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles of Lausanne | |

| Chaetogaster setosus MOTU4 | Isolates No 99, 111, 138, 147, 161: 47,152502oN, 7.014924oE | DNA voucher of the 5 specimens stored in buffer at -20oC at the Ecotox Center in Lausanne; Anterior part of the 5 specimens preserved (mounted on slides) in the Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles of Lausanne |

4. Discussion

4.1. Species Delimitations and Chaetogaster Diversity in Switzerland

4.2. Description of New Chaetogaster Species for Science

4.3. Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Timm T., Martin, P. J. Chapter 21 - Clitellata: Oligochaeta. In J. H. Thorp & D. C. Rogers (Eds) Thorp and Covich's Freshwater Invertebrates (Fourth Edition) pp. 529-549). Boston: Academic Press, 2015.

- Mack J.M., Klinth M., Martinsson S., Lu R., Stormer H., Hanington P, et al. Cryptic carnivores: Intercontinental sampling reveals extensive novel diversity in a genus of freshwater annelids. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2023, 182, 107748. [CrossRef]

- Vivien, R., Lafont, M., Werner, I., Laluc, M., Ferrari, B.J.D. Assessment of the effects of wastewater treatment plant effluents on receiving streams using oligochaete communities of the porous matrix. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ec. 2019, 420, 18. [CrossRef]

- Lafont M., Jézéquel C., Vivier A., Breil P., Schmitt L., Bernoud S. Refinement of biomonitoring of urban watercourses by combining descriptive and ecohydrological approaches. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2010, 10, 3-11. [CrossRef]

- Martin P., Reynolds J., van Haaren, T. World List of Marine Oligochaeta. Chaetogaster von Baer, 1827. 2024. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=137356 on 2024-05-17.

- Vivien, R., Lafont, M. Note faunistique sur les oligochètes aquatiques de la région genevoise et de Suisse. Rev. Suisse Zool. 2015, 122, 207-212. [CrossRef]

- Vivien R., Ferrari, B.J.D. Assessment of the biological quality and functioning of the Suze River upstream and downstream of the wastewater treatment plant in Villeret (canton of Bern) using oligochaete communities in the porous matrix, Centre Ecotox, Eawag-EPFL, 2023.

- Vivien, R., Werner, I., Ferrari, B.J.D. Simultaneous preservation of the DNA quality, the community composition and the density of aquatic oligochaetes for the development of genetically based biological indices. PeerJ 2018, 6, e6050. [CrossRef]

- Reymond O. Préparations microscopiques permanentes d’oligochètes : une méthode simple. Bull. Soc. Vaud. Sci. 1994, 83, 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Timm T. A guide to the freshwater Oligochaeta and Polychaeta of Northern and Central Europe. Lauterbornia 2009, 66, 1–235.

- Tkach V., Pawlowski J. A new method of DNA extraction from the ethanol-fixed parasitic worms. Acta Parasitol. 1999, 44, 147-148.

- Folmer O., Black M., Hoeh W., Lutz R., Vrigenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294-299.

- Leray M., Yang J.Y., Meyer C.P., Mills S.C., Agudelo N., Ranwez V. et al. A new versatile primer set targeting a short fragment of the mitochondrial COI region for metabarcoding metazoan diversity – application for characterizing coral reef fish gut contents. Front. Zool. 2013, 10, 34. [CrossRef]

- Navajas M., Lagnel J., Gutierrez J., Boursot P. Species wide homogeneity of nuclear ribosomal ITS2 sequences in the spider mite Tetranychus urticae contrasts with extensive mitochondrial COI polymorphism. Heredity 1998, 80, 742–752. pmid:9675873. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson B.G.M., Tillier S., Tillier A., Justine J.-L., Ling E., James S., et al. Phylogeny of the Megascolecidae and Crassiclitellata (Annelida, Oligochaeta): combined versus partitioned analysis using nuclear (28S) and mitochondrial (12S, 16S) rDNA. Zoosystema 2002, 24, 707-734.

- Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 2004, 5, 113. [CrossRef]

- Gouy M., Guindon S., Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 221-224. [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B.Q., Wong T. K. F., von Haeseler, A., Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587-589. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen L.T., Schmidt H.A., von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268-274. [CrossRef]

- Hoang D.T., Chernomor O., von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q., Vinh L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518-522. [CrossRef]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 2731-2739. [CrossRef]

- Dellicour S., Flot J.-F. Delimiting species-poor data sets using single molecular markers: A study of barcode gaps, haplowebs and GMYC. Syst. Biol. 2015, 64, 900-908. [CrossRef]

- Puillandre N., Brouillet S., Achaz, G. ASAP: assemble species by automatic partitioning. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 21, 609-620. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Kapli, P., Pavlidis, P. & Stamatakis, A. A general species delimitation method with applications to phylogenetic placements. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2869-2876. [CrossRef]

- Pons J., Barraclough T.G., Gomez-Zurita J., Cardoso A., Duran D.P., Hazell, S., et al. Sequence-based species delimitation for the DNA taxonomy of undescribed insects. Syst. Biol. 2006, 55, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Dellicour S., Flot J.-F. The hitchhiker's guide to single-locus species delimitation. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 1234-1246. [CrossRef]

- Luo A., Ling C., Ho S.Y.W., Zhu C.D. Comparison of methods for molecular species delimitation across a range of speciation scenarios. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 830-846. [CrossRef]

- Goulpeau, A., Penel, B., Maggia, M.-E., Marchán, D.F., Steinke, D., Hedde, M. & Decaëns, T. OTU delimitation with earthworm DNA barcodes: A comparison of methods. Diversity 2022, 14, 10. [CrossRef]

- Phillips J.D., Gillis D.J., Hanner R.H. Lack of statistical rigor in DNA barcoding likely invalidates the presence of a true species' barcode gap. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kapli P., Lutteropp S., Zhang J., Kobert K., Pavlidis P., Stamatakis A., et al. Multi-rate Poisson tree processes for single-locus species delimitation under maximum likelihood and Markov chain Monte Carlo. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 1630-1638. [CrossRef]

- Schmelz R.M., Beylich A., Boros G., Dózsa-Farkas K., Graefe U., Hong Y., et al. How to deal with cryptic species in Enchytraeidae, with recommendations on taxonomical descriptions. Opusc. Zool. 2017, 48, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y., Fend S.V., Martinsson S., Erséus C. Extensive cryptic diversity in the cosmopolitan sludge worm Limnodrilus hoffmeisteri (Clitellata, Naididae). Org. Divers. Evol. 2017, 17, 477–495.

- Dong X., Zhang H., Zhu X., Wang K., Xue H., Ye Z., et al. Mitochondrial introgression and mito-nuclear discordance obscured the closely related species boundaries in Cletus Stål from China (Heteroptera: Coreidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2023, 184, 107802. [CrossRef]

- Toews, D. P. L. & Brelsford, A. The biogeography of mitochondrial and nuclear discordance in animals. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 3907-3930. [CrossRef]

- Galtier N. An approximate likelihood method reveals ancient gene flow between human, chimpanzee and gorilla. Peer Community J. 2024, 4, e3. [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz K. Species concepts and species delimitation. Syst. Biol. 2007, 56, 879-886. [CrossRef]

- Sperber C. A taxonomical study of the Naididae. Zool. Bidr. Upps. 1950, 29, 45-81.

- Lafont M. Redescription de Chaetogaster parvus Poitner, 1914 (Oligochaeta, Naididae) avec quelques remarques sur la validité de cette espèce et sa répartition dans les eaux douces françaises. Ann. Limnol. 1981, 17, 211-217.

- Juget J. Quelques données Nouvelles sur les oligochètes du Léman: composition et origine du peuplement. Ann. Limnol. 1967, 3, 217-229.

- Bickford D, Lohman D.J., Sodhi N.S., Ng P.K.L., Meier R., Winker K., et al. Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 148-155. PMID: 17129636. [CrossRef]

- Dayrat B. Towards integrative taxonomy. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2005, 85, 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Padial J.M., Miralles A., De la Riva I., Vences M. The integrative future of taxonomy. Front. Zool. 2010, 7, 16. [CrossRef]

- Jörger K.M., Schrödl M. How to describe a cryptic species? Practical challenges of molecular taxonomy. Front. Zool. 2013, 10, 59. [CrossRef]

- Marchán D.F., Díaz Cosín D.J., Novo M. Why are we blind to cryptic species? Lessons from the eyeless, Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2018, 86, 49-51. [CrossRef]

- Jones G.L., Wills A., Morgan A.J., Thomas R.J., Kille P., Novo M. The worm has turned: Behavioural drivers of reproductive isolation between cryptic lineages, Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 98, 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Dupont L, Audusseau H, Porco D, Butt KR. Mitonuclear discordance and patterns of reproductive isolation in a complex of simultaneously hermaphroditic species, the Allolobophora chlorotica case study. J. Evol. Biol. 2022, 35, 831-843. [CrossRef]

- Lowe C.N., Butt K.R. Culture techniques for soil dwelling earthworms: A review. Pedobiologia 2005, 49, 401-413.

- Knutson V.L., Gosliner T.M. The first phylogenetic and species delimitation study of the nudibranch genus Gymnodoris reveals high species diversity (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2022, 171, 107470. [CrossRef]

- Lawley J.W., Gamero-Mora E., Maronna M.M., Chiaverano L.M., Stampar S.N., Hopcroft R.R., et al. The importance of molecular characters when morphological variability hinders diagnosability: systematics of the moon jellyfish genus Aurelia (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa). PeerJ 2021, 9, e11954. [CrossRef]

- Martinsson S., Erséus C. Cryptic Clitellata: Molecular species delimitation of clitellate worms (Annelida): An overview. Diversity 2021, 13, 36. [CrossRef]

- Zamani, A; Faltynek Fric, Z.; Gante, H.F; Hopkins, T.; Orfinger, A.B; Scherz, M. D; Suchacko Bartonova, A.; Dal Pos, D. DNA barcodes on their own are not enough to describe a species. Systematic Entomology 2022, 47, 385-389. [CrossRef]

- Gruithuisen F.V.P. Über die Nais diaphana und Nais diastropha mit dem Nerven-und Blutsystem derselben. Nova Acta Physico-Medica Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolinae Naturae Curiosorum. 1828, 14, 407-420 + Plate I.

- Vivien, R., Holzmann, M., Werner, I., Pawlowski, J., Lafont, M., Ferrari, B.J.D. Cytochrome c oxidase barcodes for aquatic oligochaete identification: development of a Swiss reference database. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4122. [CrossRef]

- Martinsson S., Erséus C. Cryptic diversity in supposedly species-poor genera of Enchytraeidae (Annelida: Clitellata). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2018, 183, 749–762. [CrossRef]

- Envall I, Gustavsson L.M., Erséus C. Genetic and chaetal variation in Nais worms (Annelida, Clitellata, Naididae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2012, 165, 495–520. [CrossRef]

- Martin P., Knüsel M., Alther R., Altermatt F., Ferrari B., Vivien, R. Haplotaxis gordioides (Hartmann in Oken, 1819) (Annelida, Clitellata) as a sub-cosmopolitan species: a commonly held view challenged by DNA barcoding. Zoosymposia 2023, 23, 78-93. [CrossRef]

| No of species found by Mack et al. (2023) | Maximal intra- MOTU variation (%) in COI | Minimal inter- MOTU variation (%) in COI | Maximal intra- MOTU variation (%) in ITS2 | Minimal inter- MOTU variation (%) in ITS2 | |

| C. diaphanus MOTU6 | “C. diaphanus” sp.4 | 2.12 | 9.57 | 4.97 | 7.46 |

| C. diaphanus MOTU7 | “C. diaphanus” sp. 3 | 0.05 | 9.57 | ||

| C. diastrophus MOTU10 | “C. diastrophus” sp. 11 | 3.87 | 11.45 | 4.48 | 9.60 |

| C. diastrophus MOTU3 | “C. diastrophus” sp. 8 | 2.74 | 14.35 | 6.21 | 7.46 |

| C. diastrophus MOTU9 | “C. diastrophus” sp. 12 | 2.89 | 11.45 | 5.58 | 11.59 |

| C. langi MOTU5 | “C. diastrophus” sp. 19 | 0.91 | 13.67 | 5.68 | 10.34 |

| C. setosus MOTU4 | 0.00 | 12.61 | 2.73 | 12.50 | |

| Chaetogaster sp. MOTU1 | NC | 14.89 | NC | 13.86 | |

| Chaetogaster sp. MOTU2 | “C. diastrophus” sp. 1 | 0 | 12.00 | 2.78 | 12.29 |

| Chaetogaster sp. MOTU8 | “C. diastrophus” sp. 18 | NC | 11.89 | NC | 9.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).