1. Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) represents a serious condition with symptoms like decreased concentration and hopeless mood observed in 10% to 20% of all postpartum women [

1,

2,

3]. Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) is most often used in order to diagnose clinical PPD. Although the risk factors are well known, less than half of women with PPD are diagnosed [

4]. Starting with pregnancy, women’s organism achieves different adaptation in order to maintain fetal development. Interestingly, messages from placenta to fetus are important in sustaining its normal state [

5]. Further, it seems that placenta could influence the fetus sex and sustains its physio-pathological implication in pregnancy [

6,

7]. However, male fetus has shown to lead to chronic inflammation of the placenta with activated pro-inflammatory cytokines in the circulation [

8,

9]. Similar studies have attributed a role to male babies on maternal reproductive hormone levels by increasing inflammation [

9,

10]. Therefore, we suppose that further maternal depressive symptoms will be influenced by the fetus’ gender, with a higher tendency on male pregnancies. One study sustains this fact, by which PPD had higher percentage of developing in women carrying a male fetus along with other birth complications [

11].

Besides gender, seasonal birth is also shown to influence the appearance of PPD. To reinforce this hypothesis, some studies showed that more cases of women with PPD were seen in winter season [

12,

13]. In contrast, Henriksson and contributors show that seasonal pattern does not influence depressive symptoms [

14].

However, the authors showed that the seasonal patterns correlated with newborn gender seems to depends on other factors related to specific climatic conditions [

14]

. Therefore, if fetus gender and seasonality can affect PPD, public health systems should take further measures to detect and prevent the appearance of PPD in such groups of women.

Knowing how depressive symptoms influence the women’s postpartum period according to newborns characteristics (i.e., the months in which they were born or premature delivery, birth weight or gender), would also contribute to a better understanding of the appearance of PPD. Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to show the impact of newborns characteristics in women with PPD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

We conducted an observational prospective study on immediate postpartum women who delivered in the Obstetrics & Gynecology Department, “Sf. Apostle Andrei”, Emergency Clinic County Hospital of Constanta (South-East of Romania). A sample of 904 women at high risk of depression in the 2nd day of postpartum period was used, divided in 2 groups: women with PPD (n=236) and control (i.e., women without PPD, n=668), by using EPDS (i.e., women who delivered a single baby).

2.2. Newborns Characteristics Information

Between August 2019 and April 2021, characteristic information on newborns from medical electronic records were assessed as follows: the months in which they were born, premature delivery (<37 gestational weeks vs. ≥37 gestational weeks), birth weight in grams (<2500 g vs. ≥2500 g), and newborns sex (male vs. female). Newborns were eligible to take part in the study if they were 2-3 days of age, and if they resided in the study area. Newborns with obvious, severe congenital abnormalities, hemoglobin <7 g/dL (normal values=13.4-19.8 g/dl), and those who were receiving special nutritional supplements as part of a feeding program were excluded.

All participants were informed regarding the aims and procedures, having the possibility to withdraw from the study at any time. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration on Human Rights and the informed consent from all participants in the study as well as the Agreement of the Ethics Commission were obtained.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS statistics software version 28 and Excel. The procedures used were descriptive statistics, graphs, and non-parametric statistical tests. Data are presented as mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum, for continuous variables, or as percentages for categorical variables. For hypotheses testing, Independent Samples Mann Whitney U test, Independent Samples T-test, Chi-Square Test of association, and Chi-squared test for the comparison of two proportions were used, depending on the type of analyzed variables. The significance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

From the total number of patients (n=904), the presence of PPD resulted in 26.10% (n=236); the control group consisted of 668 patients (73.9%).

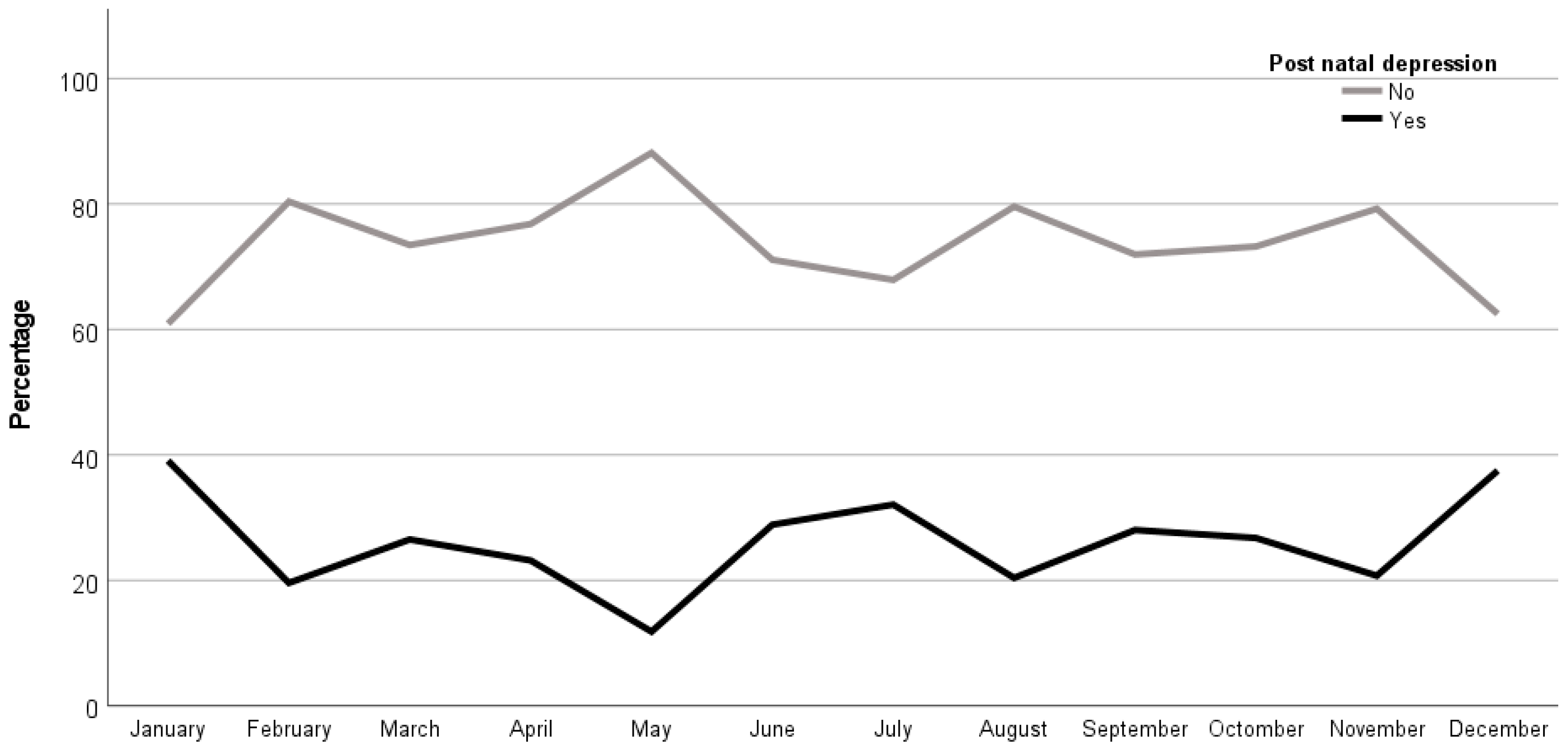

By comparing the association between the month of birth and the presence of PPD, it was shown that there was a higher value for newborns from women with PPD in the months of winter (i.e., December with 37.5%, n=3, and January with 39.1%, n=34) than the newborns from women without PPD in the summer months (i.e., May with n=67, 88.2% and August with n=78, 79.6%), all these being statistically significant (p=0.018). Therefore, the births within the winter months lead to higher proportion of women with PPD (

Figure 1).

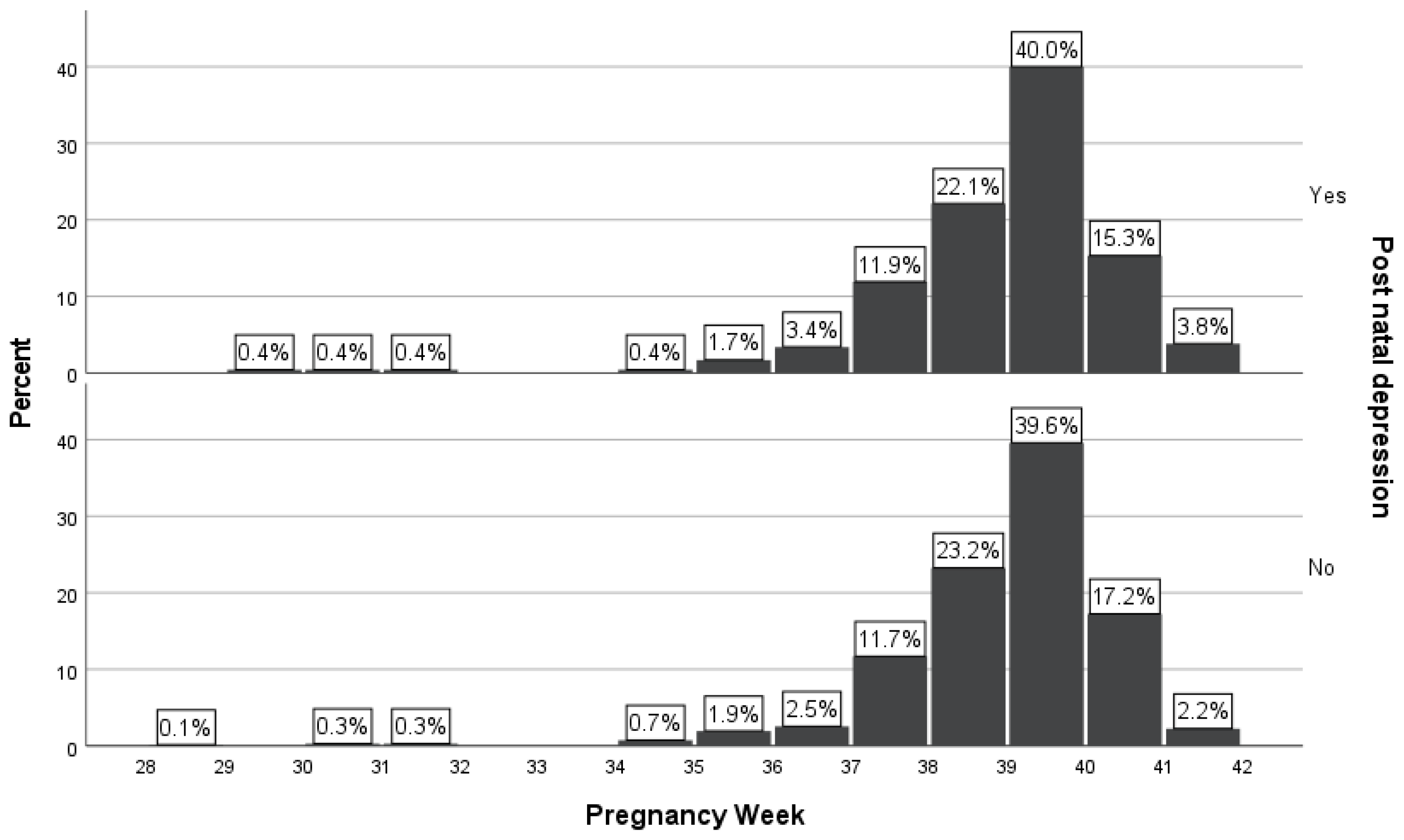

Comparing the two groups of newborns, it was shown that it was no statistically significant association of premature birth (i.e., < 37 gestational weeks) between women with PPD and without PPD (p=0.654). From the group of women with PPD (n=236, 26.1%), 16 (6.8%) newborns were premature (i.e., < 37 gestational weeks), in comparison with the group of women without PPD (n=668, 73.9%), in which 40 (6.0%) newborns were born prematurely. The number of newborns from women with PPD (n=219, 93.2%) born at ≥ 37 gestational weeks was similar with newborns from women without PPD (n=628, 94.0%) born at ≥ 37 gestational weeks (

Table 1 and

Figure 2).

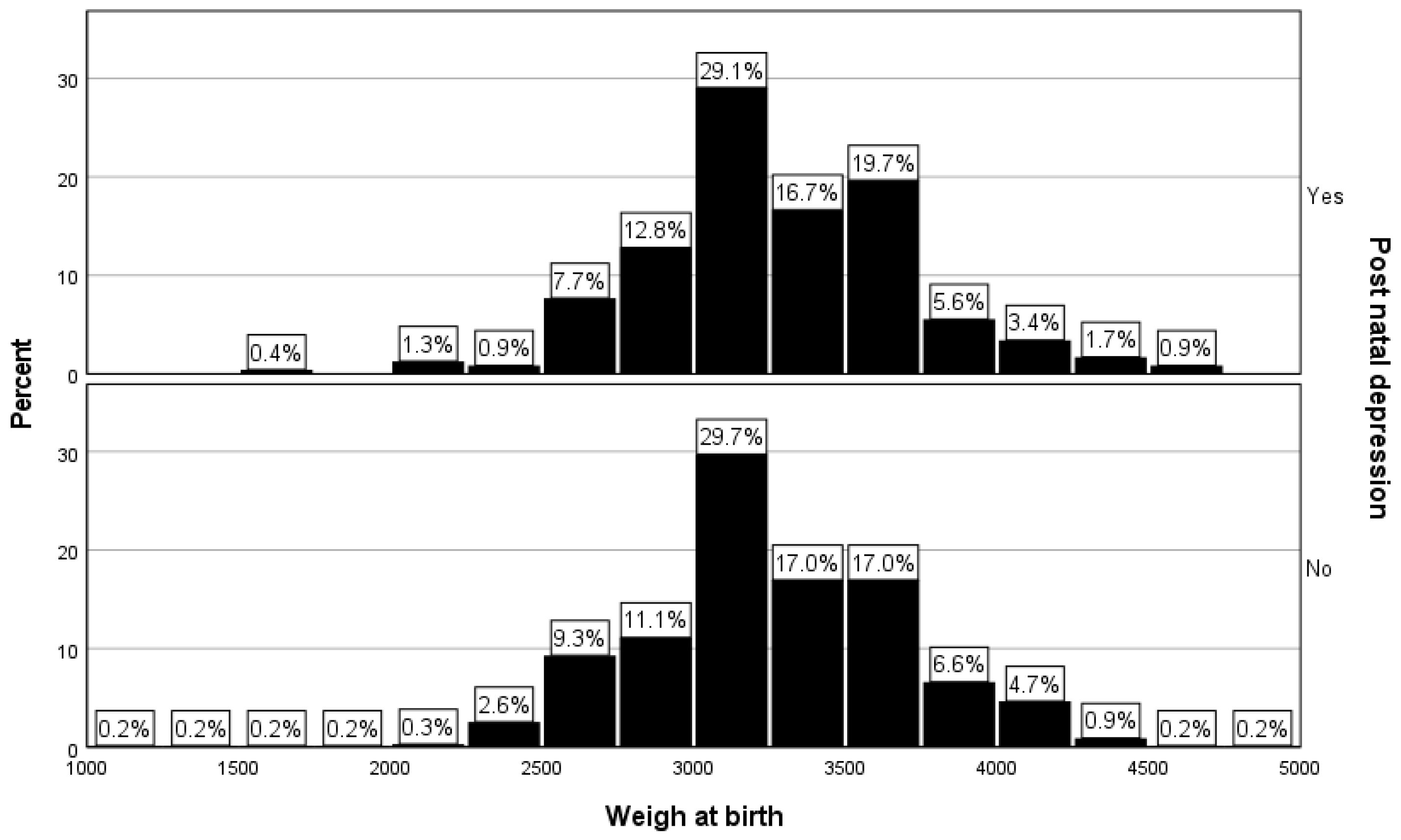

The percentage of low-birth weight newborns was 2.6% (n=6) in the PPD group, while for the women without PPD the percentage of low-birth weight newborns was 3.4% (n=23). The observed difference was not statistically significant (p=0.51,

Table 1 and

Figure 3).

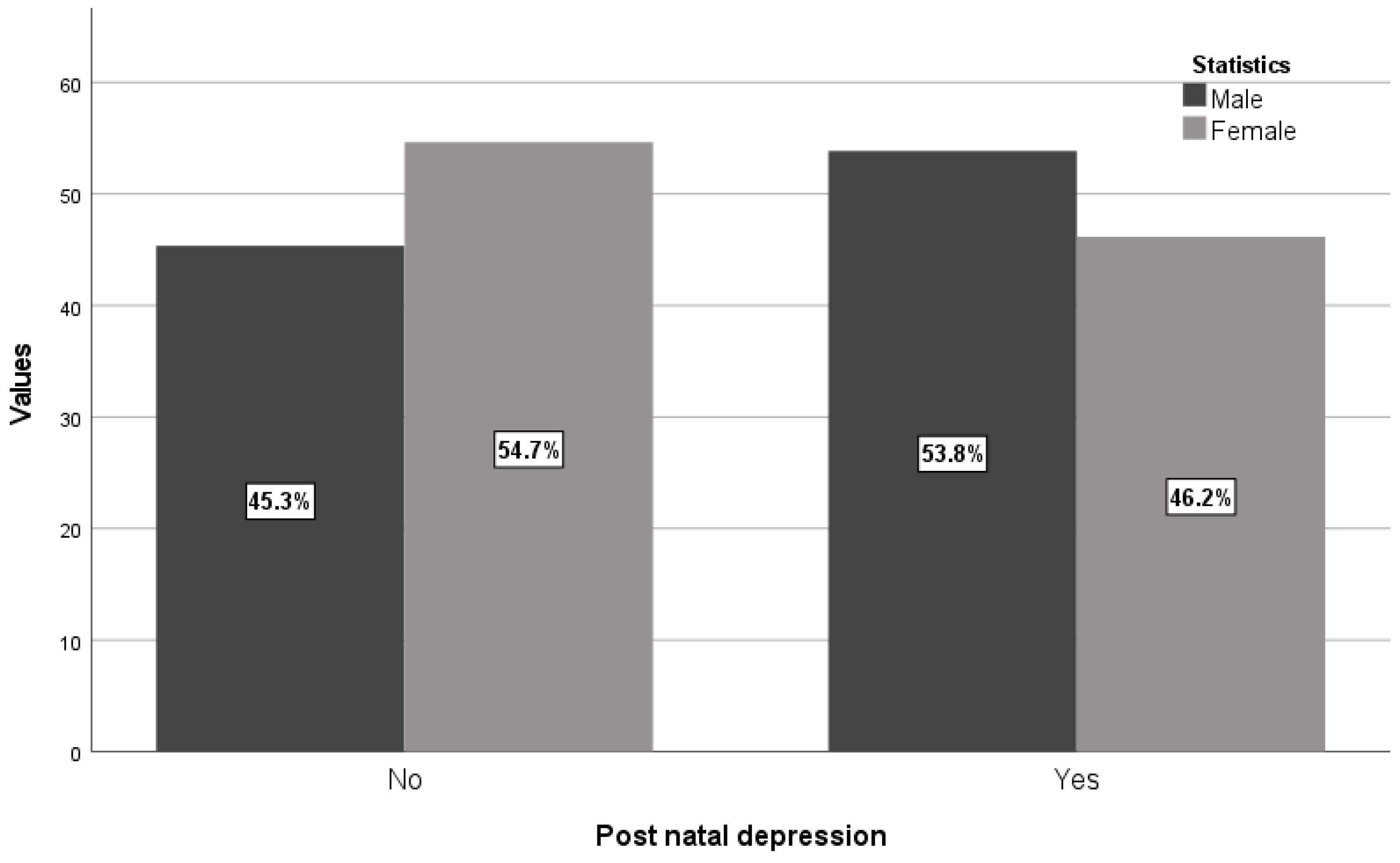

There were more male fetuses compared with female fetuses from women with PPD (53.8% vs. 45.3%) in contrast with values of newborns from women without PPD (46.2% vs. 54.7%) having statistically significant association (p=0.025,

Table 1 and

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

In the present study, from all newborn’s characteristics such as the months in which they were born, premature delivery, birth weight and infant’s sex, only the months of birth (i.e., winter season) and the newborns male sex from women with PPD were statistically significant compared to women without PPD. Our results are in accordance with another study conducted on 298 postpartum women from United Kingdom who found that the rate of PPD was up to 71-79% among women giving birth to male infants, along with birth complications [

11].

Another study found that 181 women with PPD was associated with male gender, significantly reducing the quality of life [

15]. Another study achieved from Sweden showed that the women had a higher risk of PPD 5 days after delivery of a male fetus [

16].

Some physiological mechanisms like sex-differential shifts and biomarkers from maternal reproductive system reinforces our statements. Estradiol, the hormone which inflects the serotonergic system together with progesterone levels are decreasing [

17]. However, the association between fetal gender and PPD is still under debate. Some studies showed the contrary. Another study found that dysfunctional self-reported supradiaphragmatic reactivity in the second and third trimester of pregnancy was a significant predictor of PPD at one month [

18].

The results of our study are of great clinical value on postpartum women, starting even from pregnancy. Therefore, screening for PPD in such women could lead to the decreasing of the depressive symptoms [

19,

20]. The seasonal mechanisms like winter season causing the appearance of PPD is still not well defined. When the women are exposed to higher intensity light, i.e., during the summer time, it was shown to have a positive impact on their mental health, in contrast to the winter season, when the day becomes much shorter [

21,

22]. Blume and contributors also had the same results which show that reduced day-length, and less exposure to light, may be correlated with depressive disposition [

23]. When a woman suffers from many hormonal changes starting with pregnancy, an increased level of PPD was observed [

24]. Promoting support for these women, especially by rising the connection with other people during winter season could reduce the symptomatology of PPD [

25]. A protective role was seen when such support comes much earlier in high-risk postpartum women [

26]. Moreover, it is desirable to contact hospital health professionals (immediately after birth), in order to solve such problems in the early stages [

27,

28].

However, the association between birth season, male fetal gender and PPD could help exploring much deeply what the cause of PPD is, thus preventing the occurrence of PPD in certain families.

5. Conclusions

Clinicians should pay careful attention to recognizing mothers who give birth to male infants, and who are at risk of PPD especially during the winter season. Finally, this should be taken into consideration by all health public systems to make overall decisions in PPD prevention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O. and V.T.; methodology, S.O.; software, S.C.; validation, S.O. and V.T.; formal analysis, S.R. and C.N.; data curation, S.O., M.R., C.N. and GMB; writing—original draft preparation, S.O. and D.B.; writing—review and editing, S.O., C.D. and V.T.; supervision, V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration on Human Rights. The informed consent from all participants in the study as well as the Agreement of the Ethics Commission from University Emergency County Hospital Constanta were obtained (No 29726/31.05.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cox, J.L.; Chapmand, G.; Murray, D.; Jones, P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J. Affect. Disord. 1996, 39, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, I.; Mehendale, A.M.; Malhotra, R. Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression. Cureus 2022, 14, e30898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, K.; Admon, L.K.; Winkelman, T.N.A.; Muzik, M.; Hall, S.; Dalton, VK.; Zivin, K. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, serious mental illness, and delivery-related health outcomes, United States, 2006-2015. BMC Womens Health. 2020, 20(1), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgarlou, Z.; Arzanlou, M.; Mohseni, M. The Importance of Screening in Prevention of Postpartum Depression. Iran J. Public Health. 2021, 50, 1072–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inkster, A.M.; Fernández-Boyano, I.; Robinson, W.P. Sex Differences Are Here to Stay: Relevance to Prenatal Care. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broere-Brown, Z.A.; Adank, M.C.; Benschop, L.; Tielemans, M.; Muka, T.; Goncalves, R.; Bramer, W.M.; Schoufour, J.D.; Voortman, T.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Franco, O.H.; Schalekamp-Timmermans, S. Fetal sex and maternal pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2020, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funaki, S.; Ogawa, K.; Ozawa, N.; Okamoto, A.; Morisaki, N.; Sago, H. Differences in pregnancy complications and outcomes by fetal gender among Japanese women: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, A.E.; Mitchel, O.R.; Gonzalez, T.L.; Sun, T.; Flowers, A.E.; Pisarska, M.D.; Winn, V.D. Sex at the interface: the origin and impact of sex differences in the developing human placenta. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2022, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, Z.M.; Kishk, E.A.; Elzamlout, M.S.; Elshahat, A.M.; Taha, O.T. Fetal gender, serum human chorionic gonadotropin, and testosterone in women with preeclampsia. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2020, 39, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykgraaf, R.H.M.; Schalekamp-Timmermans, S.; Adank, M.C.; van den Berg, S.A.A.; van de Lang-Born, B.M.N.; Korevaar, T.I.M.; Kumar, A.; Kalra, B.; Savjani, G.V.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Louwers, Y.V.; Laven, J.S.E. Reference ranges of anti-Müllerian hormone and interaction with placental biomarkers in early pregnancy: the Generation R Study, a population-based prospective cohort study. Endocr. Connect. 2023, 12, e220320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.; Johns, S.E. Male infants and birth complications are associated with increased incidence of postnatal depression. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 220, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sit, D.; Seltman, H.; Wisner, K.L. Seasonal effects on depression risk and suicidal symptoms in postpartum women. Depression and Anxiety. 2011, 28, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, TC.; Peng, H.C.; Chen, C.; Chen, C.S. Mode of Delivery Is Associated with Postpartum Depression: Do Women with and without Depression History Exhibit a Difference? Healthcare (Basel). 2022, 10(7), 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, H.E.; Sylven, S.M.; Kallak, T.K.; Papadopoulos, F.C.; Skalkidou, A. Seasonal patterns in self-reported peripartum depressive symptoms. European Psychiatry. 2017, 43, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Tychey, C.; Briancon, S.; Lighezzolo, J.; Spitz, E.; Kabuth, B.; de Luigi, V.; Messembourg, C.; Girvan, F.; Rosati, A.; Thockler, A.; Vincent, S. Quality of life, postnatal depression and baby gender. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylven, S.M.; Papadopoulos, F.C.; Mpazakidis, V.; Ekselius, L.; Sundstrom-Poromaa, I.; Skalkidou, A. Newborn gender as a predictor of postpartum mood disturbances in a sample of Swedish women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2011, 14, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’ Brien, S.; Sethi, A.; Gudbrandsen, M.; Lennuyeux-Comnene, L.; Murphy, D.G.M.; Craig, M.C. Is postnatal depression a distinct subtype of major depressive disorder? An exploratory study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2021, 24, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solorzano, C.S.; Grano, C. Predicting postpartum depressive symptoms by evaluating self-report autonomic nervous system reactivity during pregnancy. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2023, 174, 111484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.A.; Alkhatib, A.; Luo, J. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in the Middle East: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021, 21, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Hamel, C.; Thuku, M.; Esmaeilisaraji, L.; Bennett, A.; Shaver, N.; Skidmore, B.; Colman, I.; Grigoriadis, S.; Nicholls, S.G.; Potter, B.K.; Ritchie, K.; Vasa, P.; Shea, B.J.; Moher, D.; Little, J.; Stevens, A. Screening for depression among the general adult population and in women during pregnancy or the first-year postpartum: two systematic reviews to inform a guideline of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Lonstein, J.S.; Nunez, A.A. Light as a modulator of emotion and cognition: Lessons learned from studying a diurnal rodent. Hormones and Behavior. 2019, 111, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.; Patel, R.; Evans, J.; Greenwood, R.; Hicks, J. The relationship between perinatal circadian rhythm and postnatal depression: an overview, hypothesis, and recommendations for practice. Sleep Science Practice. 2022, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, C.; Garbazza, C.; Spitschan, M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie. 2019, 23, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Scior, K. Self-esteem and its relationship with depression and anxiety in adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic literature review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2023, 67, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.L.; Nath, S.; Sokolova, A.Y.; Lewis, G.; Howard, L.M.; Johnson, S.; Sweeney, A. The relationship between social support in pregnancy and postnatal depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoudi, P.; Strömwall, L.A.; Åhlen, J.; Fredriksson, A.K.; Dencker, A.; Andersson, E. Women’s experiences of psychological treatment and psychosocial interventions for postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Women’s Health. 2023, 23, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubu, R.A.; Ajayi, K.V.; Dhaurali, S.; Carvalho, K.; Kheyfets, A.; Lawrence, B.C.; Amutah-Onukagha, N. Investigating the Role of Race and Stressful Life Events on the Smoking Patterns of Pregnant and Postpartum Women in the United States: A Multistate Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Phase 8 (2016-2018) Analysis. Matern. Child Health J. 2023, 27 (Suppl 1), 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea-Holhoș, L.B.; Delcea, C.; Siserman, C.V.; Ciocan, V. Age Estimation of Human Remains Using the Dental System: A Review. Ann Dent Spec. 2023, 11, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).