Introduction

Effective waste management and recycling systems are essential for addressing global environmental challenges associated with rising waste generation, particularly in

developing nations where

urban-rural disparities complicate sustainable practices. This global push, fueled by the

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for responsible consumption (SDG 12) and climate action (SDG 13), underscores the need for

efficient, equitable waste systems [

1]. Despite Costa Rica’s reputation as a

sustainability leader in Latin America, the nation faces significant

waste management challenges due to infrastructural gaps and financial constraints. Such urban-rural divides are also evident in other global contexts, where disparities in infrastructure and resource allocation underscore the need for

tailored, inclusive policies to advance sustainable development [

2]. These challenges are common in developing countries, where effective

circular economy practices in waste management remain underdeveloped, especially in the face of inadequate

recycling infrastructure and

open dumping practices [

3]. Studies have highlighted the critical role of

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in mapping recycling facility access, especially for strategic management of

plastic waste in the Global South, suggesting GIS-based approaches as transformative in

reducing plastic pollution [

4]. Social dynamics and internet access have also been shown to play a crucial role in fostering

waste-sorting behaviors in rural areas, supporting sustainable practices [

5]. Urban centers like

San José benefit from dense recycling networks, while rural areas such as Limón and Guanacaste suffer from limited access, resulting in disparities in recycling participation rates across the country [

6]. This study addresses these critical gaps in Costa Rica’s waste infrastructure, aiming to bridge the

rural-urban divide by strategically improving recycling accessibility.

The objectives of this research are fivefold: first, to evaluate current accessibility of recycling facilities across Costa Rican provinces using

geospatial and demographic data; second, to simulate the effects of adding recycling facilities in underserved regions to quantify accessibility improvements; third, to

predict recycling rates across provinces under enhanced infrastructure scenarios using

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) and

Reinforcement Learning (RL); fourth, to assess the

economic feasibility of waste management initiatives through a cost simulation model that integrates ABM, RL, and Monte Carlo methods; and fifth, to recommend

optimal waste management strategies using RL to align with Costa Rica’s sustainability goals.

In a context where economic constraints often pose barriers to sustainable practices, a risk assessment framework based on fuzzy synthetic evaluation can help prioritize and address key financial and operational risks, aiding decision-makers in implementing resilient waste management strategies [

7].

The study’s methodology combines

spatial analysis with

ABM and RL, providing

dynamic insights into infrastructure needs and potential

recycling behavior changes. ABM is increasingly valued in

environmental management for exploring

human-environment interactions and evaluating policies through

scenario-based simulations [

8]. By simulating diverse recycling patterns and optimizing

policy recommendations in real time, this research offers a comprehensive framework for

equitable waste management. Similar applications of RL combined with ABM have proven effective in exploring complex social dynamics, as seen in [

9], which demonstrates how reward structures within an agent-based model can shape collective behaviors, providing valuable insights for policy development in adaptive systems.

To assess the economic feasibility of these strategies, the study integrates a cost simulation model that combines ABM, RL, and Monte Carlo methods. This economic model accounts for setup and maintenance costs for recycling facilities, operational expenses, and processing fees, incorporating variability to reflect uncertainties across regions. Sensitivity analyses applied within both ABM and RL models further enhance robustness, allowing results to be adaptable across varied population densities and facility layouts. Through this integrated framework, the research advances waste management by providing a dynamic assessment of recycling accessibility, policy optimization, and cost impact, contributing valuable insights toward Costa Rica’s sustainability and cost-efficiency goals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Current State of Waste Management

Costa Rica faces significant challenges in waste management, with pronounced regional differences due to socioeconomic and infrastructure variability. In the

Metropolitan Area, the waste generation rate is approximately

0.59 kg per person per day, with

55.9% of the waste stream being organic [

10]. In contrast,

Guácimo reports a slightly lower rate of

0.55 kg per person per day, composed of

35% recyclable materials,

45% biodegradable waste, and

20% destined for landfills [

11]. These discrepancies highlight the

47% share of national waste produced in urban centers like San José, which strains existing infrastructure. The recent closure of the

Los Pinos landfill in Cartago has exacerbated the need for alternative solutions. Developing accurate leachate movement models tailored to Costa Rica’s tropical environment is essential for improved landfill management [

6].

To tackle these challenges effectively, it is essential to analyze the regional distribution of waste types, as detailed in

Table 1.

2.2. Landfill Capacities and Regional Waste Management Practices

Data from the Ministry of Health indicates that

1,282,057 tonnes of waste were directed to landfills in 2021, with only

9.6% deemed recoverable. This highlights considerable shortcomings in Costa Rica's waste management systems, as merely

3.9% of the waste was recycled,

2.7% composted, and

2.4% co-processed [

12,

13]. Urban centers, particularly San José, generate a significant share of organic waste—approximately

58%—which emphasizes the urgent need for expanded composting and organic waste treatment facilities [

14]. Currently,

94% of the nation's solid waste is deposited in landfills, posing substantial environmental challenges. The situation is exacerbated in rural areas where waste collection infrastructure remains inadequate, underlining the critical need for robust policy measures to reduce landfill dependence and address these regional disparities [

15,

16].

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of waste sent to landfills by category, illustrating the limited recovery potential and highlighting areas where improvements could yield significant benefits.

2.3. Costa Rica's Recycling Challenge: A Global Perspective

Costa Rica’s recycling rate remains low at

9.6%, with

83.8% of waste diverted to landfills. In comparison,

Germany and

South Korea boast recycling rates of

69.3% and 50%, respectively, due to strong policy frameworks and high public participation [

13]. Costa Rica could benefit by adopting similar strategies, such as

mandatory recycling quotas and

deposit return schemes, which have driven success in other countries.

Table 3 presents a comparative overview of recycling rates in Costa Rica and other countries, highlighting the gaps in infrastructure and regulatory support that Costa Rica could address.

2.4. Government Initiatives and Policies

The Costa Rican government has introduced key initiatives, such as the

Environmental Health Route policy and the

National Circular Economy Strategy, to increase the national recycling rate to

25% by 2033. These initiatives include specific targets, such as a

10% reduction in per capita waste generation by 2025, enhanced public education on recycling, and development of new processing facilities in underserved areas [

24]. Additionally,

Law No. 9786, targeting single-use plastics, supports these goals by enforcing restrictions and promoting sustainable alternatives [

25,

26].

Table 4 summarizes the primary government initiatives and their objectives, illustrating the Costa Rican government’s multifaceted approach to addressing waste management challenges.

These initiatives underscore Costa Rica’s commitment to waste management reform through policy innovation, infrastructure development, and public engagement.

2.5. Waste Management Innovation Index

The Waste Management Innovation Index offers a comprehensive comparison of waste management practices globally, assessing each country’s progress in technological advancements, policy innovation, public engagement, infrastructure development, and sustainability impact. This index highlights areas where Costa Rica's waste management practices fall short compared to leading countries globally, as shown in

Table 5.

The index underscores Costa Rica’s need for improvement in technology and infrastructure, with Germany, South Korea, and Sweden serving as models for advancing Costa Rica’s waste management practices.

2.5. Innovative Waste and Water Management Initiatives in Costa Rica

The

Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE) has unveiled a significant

biogas initiative aimed at addressing the country’s mounting

waste management crisis. This ambitious project, planned for roll-out over the

next five to six years, focuses on converting

organic waste, which constitutes

53% of the nation’s waste stream, into

renewable energy.

ICE’s executive president, Marco Acuña, highlighted the success of an existing

biogas facility at La Uruca, which generates

140 kilowatts of energy from landfill gas, feeding directly into the

national power grid. This biogas initiative aligns with the Ministry of Health’s

“Waste to Energy” strategy, targeting the development of regional waste-to-energy centers throughout Costa Rica. However,

municipal engagement and infrastructure challenges remain significant hurdles, underscoring the need for strengthened partnerships for comprehensive implementation. As a

medium-term solution, ICE’s biogas project promises to reduce dependency on landfills, alleviating the environmental strain on the heavily impacted

Greater Metropolitan Area [

34].

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

The methodology involved collecting

geospatial and

demographic data. Geospatial data included shapefiles of Costa Rica's

provincial boundaries and the locations of existing and potential

recycling facilities, sourced from previous research [

35]. These shapefiles were processed using GeoPandas in Python, ensuring alignment with the Coordinate Reference System (CRS) for accurate spatial analysis. To refine province-specific analyses, the recycling facility data was filtered to include only facilities within each provincial boundary.

Demographic data, collected from official sources, included

population totals and

average household sizes for each province, as shown in

Table 6 [

36]. This data enabled estimation of household numbers, essential for scaling spatial analyses and aligning simulation results with actual population distributions.

For provinces lacking specific household location data,

simulated household points were generated within provincial boundaries using the population and household size data from

Table 6. This simulation applied

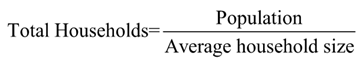

Equation 1, which calculates the total number of households in each province:

The simulated households were incorporated into the spatial analysis, allowing for the evaluation of their proximity to both existing and potential recycling facilities. This ensured a more precise representation of recycling accessibility across Costa Rican provinces.

3.2. Distance Calculations and Household Count in Distance Ranges

For both actual and simulated households, the

straight-line (Euclidean) distance to the nearest existing or proposed recycling facilities was calculated. This distance measurement is standard in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for assessing

geographic proximity between points, commonly applied in infrastructure and accessibility studies [

37].

These distances were categorized into

five intervals: 0-5 km, 5-10 km, 10-20 km, 20-50 km, and >50 km. These intervals were selected to represent significant levels of accessibility to recycling centers. To count the number of households within each distance range, an

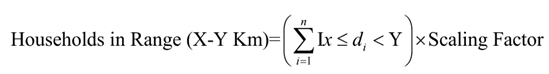

indicator function was applied, assigning a value of 1 if a household's distance did_idi falls within a specified range [X,Y] and 0 otherwise. The total household count for each range [X,Y] was calculated using

Equation 2:

where:

di represents the distance of household i to its nearest facility.

IX≤di<Y is an indicator function equal to 1 if did_idi is within the range [X,Y], and 0 otherwise.

n is the total number of sampled households.

The scaling factor is applied in provinces where household samples were used, to approximate the total population within each distance range.

3.3. Expanded Agent-Based Model for Recycling Rate Prediction

This model simulates provincial recycling rates by generating randomized data within predetermined ranges for each province, facilitating the analysis of recycling rate patterns and the assessment of potential impacts of improved accessibility to recycling facilities.

3.3.1. Simulation Approach

The simulation estimates recycling rates by generating random data points following a

normal distribution, using

mean (μpi) and

standard deviation (}σpi) values from real-world data. Each province undergoes

100 iterations to capture variability in recycling behavior, ensuring statistically realistic outcomes based on

normal distribution sampling [

38]. Using the np.random.normal() function, the simulation calculates recycling rates for each province, producing datasets for analysis and validation.

To obtain the

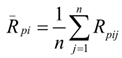

average recycling rate (Rˉpi) for each province, the simulation applies

Equation 3:

Where:

Ṝpi represents the average recycling rate for province i,

n is the number of simulations,

Rpij is the recycling rate from the j-th simulation for province i.

This approach ensures a statistically robust measure of the typical recycling rate, reflecting variability across iterations.

3.3.2. Validation Against Real Data

The simulated recycling rates were validated by comparing them to

official recycling data for each province. Any discrepancies were addressed through parameter adjustments, aligning the simulated results with real-world performance and enhancing predictive reliability [

39].

3.3.2. Recycling Rate Calculation

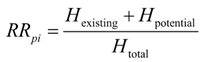

To assess recycling accessibility, a

proximity-weighted formula was used to calculate the

recycling rate (RRpi) for each province, accounting for both existing and potential recycling facilities. The calculation applies

Equation 4:

Where:

Hexisting Households within a certain radius of existing facilities,

Hpotential Households within a certain radius of potential facilities,

Htotal is Total number of households in the province.

This GIS-based accessibility analysis evaluates infrastructure distribution and its impact on recycling rates, providing insights into how strategic facility placement can improve provincial recycling performance.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Recycling Accessibility Model

The sensitivity analysis extends the

proximity-weighted formula from

Section 3.4, evaluating how variations in key parameters impact

recycling accessibility using an

Agent-Based Model (ABM). It examines three variables:

household coverage near existing facilities (Hexisting), coverage near potential facilities (Hpotential), and

proximity adjustment factors. Hexisting assesses accessibility within defined distance ranges (e.g., 0-5 km, 5-10 km), while Hpotential simulates additional coverage from varying site counts (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20).

Proximity adjustment factors alter distance thresholds to simulate improved accessibility, while scaling factors (e.g., 1.0, 1.2, 1.5) adjust household counts to reflect potential population density changes. Using spatial data, the analysis identifies configurations that maximize accessibility by testing these variables across multiple scenarios.

4. Q-Learning Approach for Waste Management Optimization

4.1. Waste Management Optimization Model and Architecture

The Q-learning-based reinforcement learning (RL) model was developed to optimize waste management strategies across Costa Rica’s provinces. It simulates interventions and policies that affect key waste management metrics, focusing on improving recycling rates, reducing landfill reliance, and enhancing biogas production capacity. By evaluating the impact of distinct actions across provincial contexts, each with specific baseline metrics, the model serves as a decision-making tool within a broader waste management framework.

The Q-learning algorithm enables the agent to learn optimal policies over time by receiving feedback on state changes following actions. The model includes 12 discrete actions, representing specific interventions. Examples include:

Action 0: Increase the recycling rate by 5%.

Action 1: Improve waste-to-energy (WtE) technology, increasing WtE investment by 10% and reducing landfill dependence by 2%.

Each action adjusts

state variables such as recycling rates, landfill usage, emissions, and bioenergy production, reflecting their

multi-faceted impacts. The state space is initialized with

province-specific baselines, such as current recycling rates and landfill dependence, to simulate real-world conditions. This approach demonstrates the

flexibility of Q-learning in optimizing complex, multi-variable systems. Similar applications of Q-learning have been effective in minimizing

carbon emissions in recycling line challenges [

40] and improving

human-robot collaboration in waste management processes [

41].

By integrating provincial baselines and intervention strategies, the model provides a robust framework for data-driven optimization of Costa Rica’s waste management goals.

4.2. Dataset and Model Initialization

The model’s dataset comprises

25 variables representing key aspects of waste management, including

waste generation,

landfill capacity,

recycling efforts,

public engagement, and

bioenergy production. These variables, normalized between

0 and 1, ensure computational efficiency and are derived from

official studies and

national reports, ensuring relevance to Costa Rica's waste management context. Key variables and their ranges, outlined in

Table 7, encompass environmental and social metrics vital for simulations, complementing the data discussed in

Section 3.1.

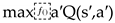

4.3. Q-Learning Configuration

The

Q-learning algorithm employed a learning rate (

α=0.1) and a discount factor (

γ=0.99) to balance

immediate and long-term rewards. An

epsilon-greedy strategy with decay (

ϵ=1.0) facilitated exploration during early training and increased exploitation as learning progressed. The

Q-value updates, governed by

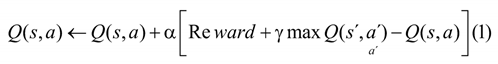

Equation 5, allowed the agent to refine its decision-making:

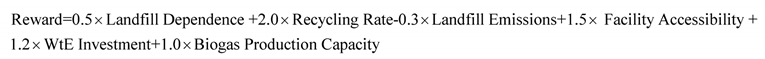

where:

Q(s,a) is the expected cumulative reward for taking action a in state s,

α controls how quickly the model updates beliefs,

γ factors future rewards, and

is the maximum expected reward for the next state.

The

reward function (Equation 6) aligned with Costa Rica’s waste management goals, penalizing

landfill emissions and

water pollution while incentivizing improvements in

recycling rates,

facility accessibility,

public engagement, and investments in

waste-to-energy (WtE) technologies. This function prioritized actions that contributed most to sustainability metrics.

To ensure model robustness, a

sensitivity analysis was conducted on key hyperparameters, including

α,

γ, and

ϵ, as well as reward weights for

recycling and

landfill reduction. Using a custom

WasteManagementEnv class, these parameters were systematically varied across multiple episodes. Results, summarized in

Table 8, identified the most effective configurations for optimizing

recycling rates and

landfill reliance.

4.3. Cost Simulation Methodology for Provincial Waste Management

The cost simulation integrates Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), Reinforcement Learning (RL), and Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate waste management feasibility across Costa Rica. ABM models waste flows (1.5 tons per household annually) and facility expenses, while RL optimizes strategies for recycling rates, landfill reduction, and biogas production. Monte Carlo simulations refine cost projections across 100 iterations, introducing variability in electricity, fuel, and operational costs to highlight cost-effective solutions.

Table 9 summarizes the key cost parameters used, including facility setup, maintenance, and processing expenses, providing a comprehensive overview for decision-making.

5. Results

5.1. Accessibility of Households to Recycling Facilities Across Provinces

The analysis reveals that

adding potential recycling facilities significantly increases household coverage across Costa Rican provinces, particularly in underserved areas (

Supplementary Table 1 provides facility counts/locations by province;

Supplementary Table 2 details household accessibility by distance). This expansion is strategically illustrated in

Figure 1, which visually represents the distribution of both existing and potential recycling facilities, highlighting key placements aimed at improving accessibility and filling service gaps across Costa Rica.

In Alajuela, potential facilities increase 0-5 km access from 23.1 million to 34.7 million households and add 9.2 million households within 10-20 km, effectively reducing travel distances and enhancing service reach. Cartago benefits from new facilities, with an additional 8,550 households within 0-5 km and expanded 20-50 km coverage reaching 52,700 households.

For Guanacaste, where population density is lower, potential facilities reduce the median access distance from 8.7 km to 6.3 km, benefiting 2,719 households. Heredia gains improved access for 74,258 households within 20-50 km, addressing gaps in suburban areas, while Limón shows expanded 0-5 km access from 29,363 to 44,045 households and 10-20 km access for 29,363 households with the addition of new facilities. Puntarenas shows unique coastal distribution patterns, with potential facilities adding 47,250 households within 5-10 km, easing the load on current sites and improving inland service.

In San José, coverage is extensive, with 0-5 km access rising from 26,114 to 46,895 households and 20-50 km access expanding to serve 250,694 households, enhancing both suburban and semi-urban reach. In summary, strategically placed facilities would significantly improve accessibility in Alajuela, Cartago, and San José, while Limón, Puntarenas, and Guanacaste would benefit from increased coverage in intermediate and rural areas. This expanded network of facilities is designed to reduce regional accessibility disparities and support a balanced recycling infrastructure across Costa Rica.

Figure 1 visually represents the distribution of both existing and potential recycling facilities across Costa Rica’s provinces, demonstrating strategic site placement to enhance accessibility and fill current service gaps.

Caption:

Figure 1 shows the distribution of existing (green circles) and potential (purple crosses) recycling facilities across the provinces of Limón, Puntarenas, Alajuela, Guanacaste, San José, Heredia, and Cartago in Costa Rica. Existing sites meet current needs, while potential sites target areas with gaps.

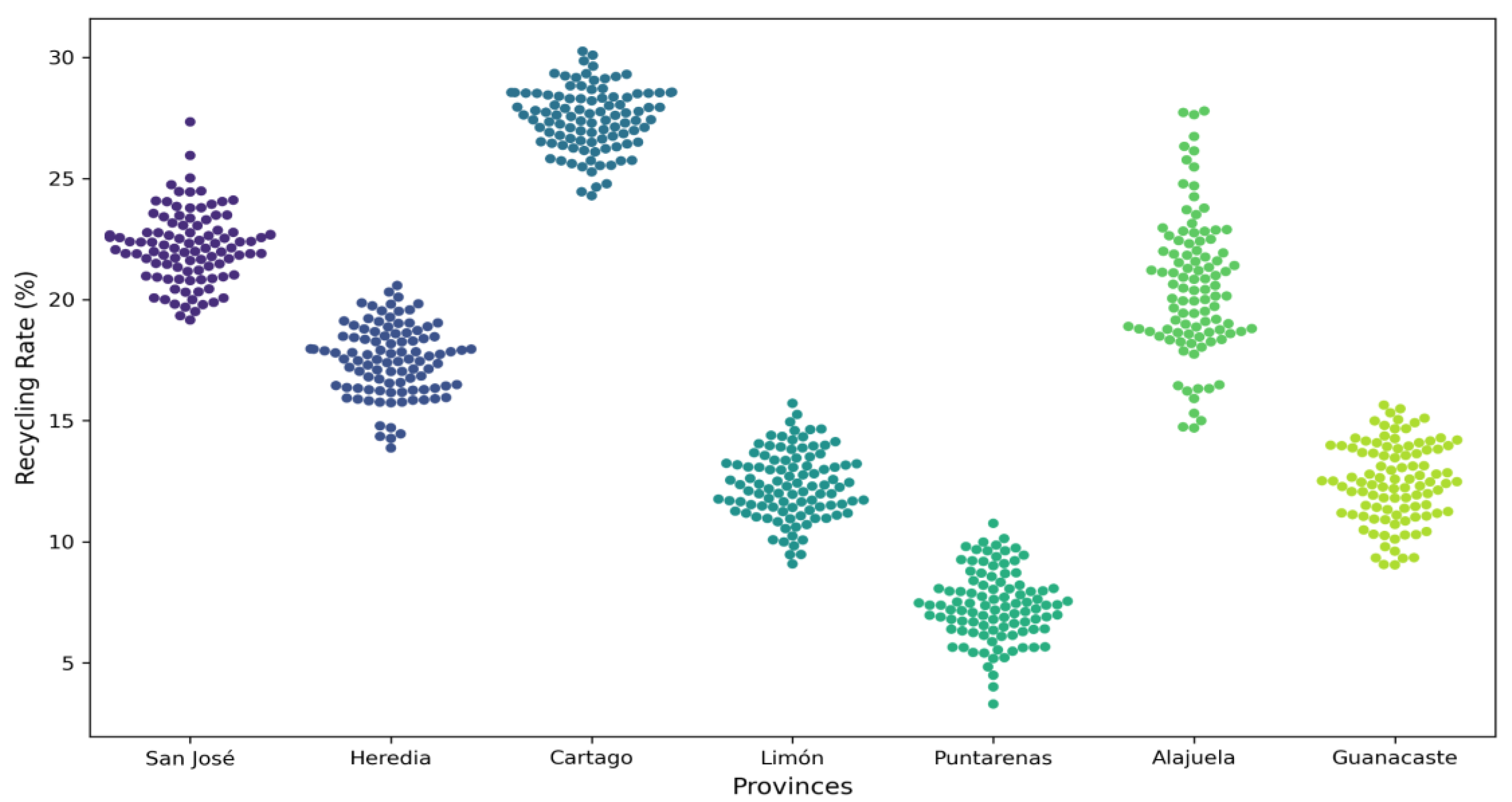

5.2. Simulated Recycling Rates Across Provinces

The

simulated recycling rates reveal substantial regional differences across Costa Rica, influenced by

infrastructure density, geography, and

public engagement.

Table 10 shows average recycling rates and variability, with

Cartago leading at

27.38%, driven by well-distributed facilities that promote widespread participation.

San José follows with

22.29%, benefiting from dense urban infrastructure, while

Heredia (17.82%) has high urban participation but limited reach in peripheral areas.

Limón (12.83%) and

Puntarenas (7.69%) face challenges due to geographic constraints and sparse facility coverage, while

Alajuela exhibits the highest rate variability (

2.88%), reflecting a pronounced urban-rural divide.

Guanacaste (12.50%) similarly experiences limited access outside main towns due to its rural character.

This analysis emphasizes the importance of

strategic facility placement to improve recycling rates and enhance equitable access, especially in underserved rural and suburban areas.

Figure 2 visually depicts the recycling rate distribution across provinces, highlighting regional variability and the distinct challenges faced by provinces with lower rates.

Caption:Figure 2 illustrates the

distribution of simulated recycling rates for each of Costa Rica’s provinces using a

swarm plot. Each point represents an individual simulation of the

recycling rate, and the spread of points highlights the

variability in recycling participation across provinces.

Cartago exhibits the

highest recycling rate, while

Puntarenas shows the

lowest, with substantial disparities observed in the more

rural regions of

Limón and

Guanacaste.

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis for Accessibility-Based Model (ABM)

The sensitivity analysis of the Accessibility-Based Model (ABM) examines how adjustments in facility numbers, population scaling, and distance ranges affect accessibility across Costa Rican provinces, highlighting distinct impacts in rural, suburban, and urban regions.

In rural areas like Guanacaste, household accessibility improves significantly with additional facilities at 10–20 km and 20–50 km distances. Adding 20 facilities and applying a scaling factor of 1.5 notably increased coverage, emphasizing the importance of facility density in sparsely populated regions. For suburban provinces like Alajuela, accessibility gains were most pronounced within 10–20 km when 15 facilities were added, indicating that intermediate placements effectively support suburban zones with moderate densities. In urbanized San José, proximity proved crucial; accessibility gains peaked within 0–5 km distances and a scaling factor of 1.5, showing that densely populated areas benefit most from nearby facilities. Limón and Puntarenas, with dispersed populations, saw the greatest improvements at 20–50 km, highlighting the need to extend reach to remote households. Heredia and Cartago also benefited from additional facilities and scaling factors within 20–50 km, indicating the value of targeted facility placements in semi-urban areas.

Supplementary Figure 1 provides a visual representation of accessibility changes by distance range and scaling factor across provinces, while

Supplementary Table 3 details facility placement and household coverage values.

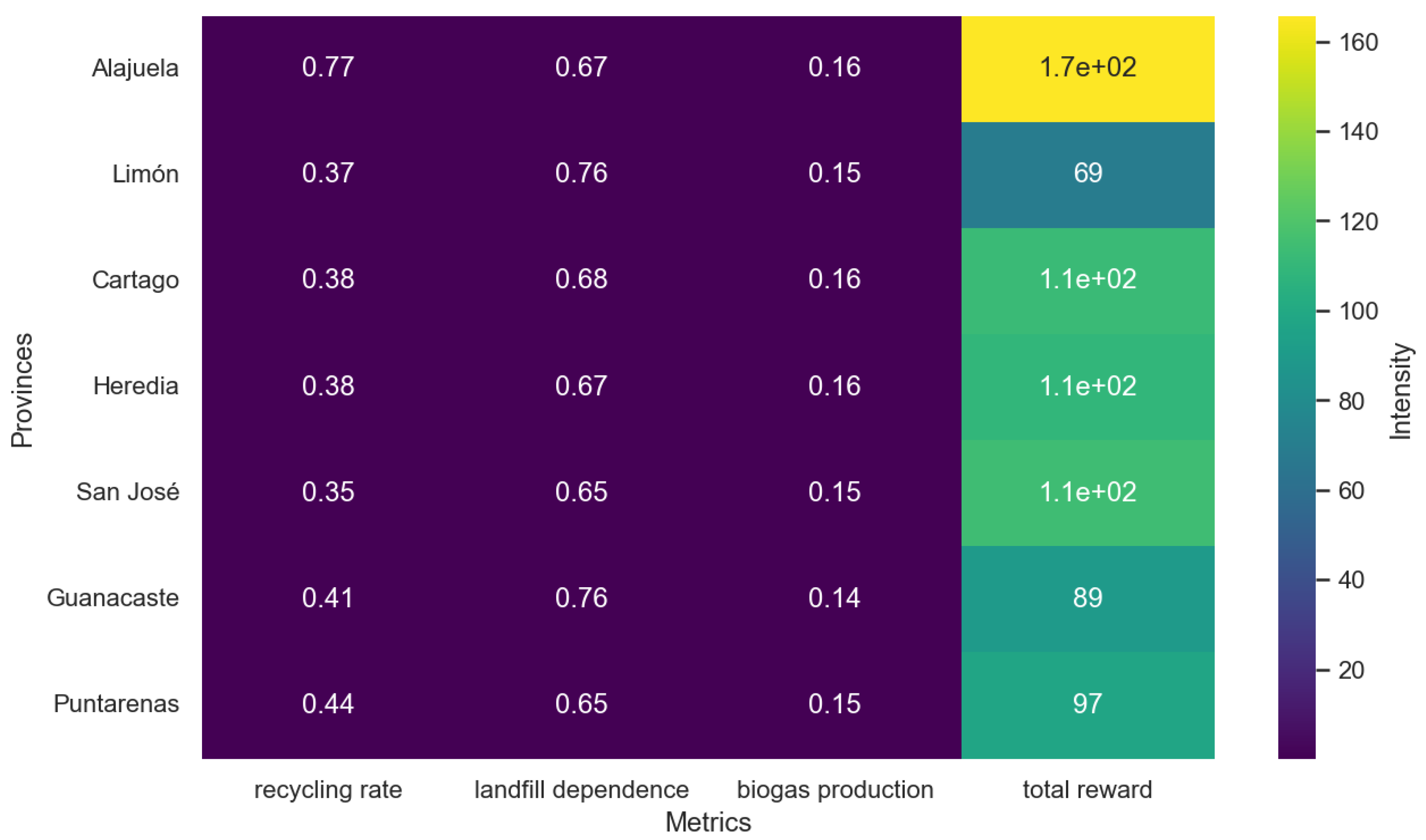

5.3. Reinforcement Learning Model for Optimizing Waste Management

The Reinforcement Learning (RL) model optimizes waste management strategies in Costa Rica’s provinces by targeting recycling rates, landfill reduction, and biogas production. Using a Q-learning algorithm, the model tailors waste management interventions to each province's conditions and simulates their impacts on waste metrics, offering insights into the effectiveness of localized strategies.

Table 11 presents the results for each province, detailing

recycling rates,

landfill dependence,

biogas capacity, and

total rewards after 100 iterations. The results show significant regional differences, with

Cartago achieving the highest recycling rate (53.38%), indicating that well-optimized infrastructure can greatly enhance waste management.

Heredia and Puntarenas also performed well with recycling rates of

47.59% and

48.63%, while

San José exhibited the highest landfill dependence at

81.14%, highlighting a need for expanded recycling facilities and urban engagement.

Limón and

Guanacaste also faced high landfill reliance (64.16% and 74.08%), reflecting the limited infrastructure in rural areas.

The total reward metric, a measure of strategy effectiveness, peaked in Limón (120.35), showing that rural areas can improve with focused interventions. Alajuela and San José, with lower rewards (92.02 and 87.34), could benefit from additional infrastructure and targeted policies to boost recycling and reduce landfill use. These findings emphasize the value of region-specific strategies and demonstrate the RL model’s potential to guide policy, aligning infrastructure expansion and policies to local needs.

Figure 3 provides a

heatmap visualizing these metrics across provinces, highlighting regional disparities in waste management and pinpointing areas for targeted improvements.

Caption:The heatmap illustrates key waste management metrics for seven provinces: Alajuela, Limón, Cartago, Heredia, San José, Guanacaste, and Puntarenas. The metrics include recycling rate, landfill dependence, biogas production, and total reward from recycling and waste processing activities.

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis of the RL-Based Waste Management Model

The sensitivity analysis assesses the RL model's effectiveness across Costa Rican provinces by examining

recycling rate,

landfill dependence, and

biogas production capacity. The

cumulative reward metric indicates the success of each province’s waste management optimization (see

Supplementary Figure 2 for a comparison of these metrics).

Table 12 summarizes the final values, showing the model’s varied impact under different regional conditions.

The analysis reveals substantial regional differences. Heredia achieves the highest recycling rate (67.59%) and a relatively low landfill dependence (68.73%), reflecting the benefits of local infrastructure and engagement. In contrast, San José shows the highest landfill dependence (77.14%), highlighting a need for more recycling facilities and policy support in urban areas. Limón and Guanacaste also struggle with high landfill reliance, reflecting infrastructure limitations in rural areas.

The total reward metric further identifies areas of effective waste management, with Alajuela and Heredia leading at 138.67 and 102.89, indicating significant progress. In contrast, San José (83.62) and Puntarenas (80.90) suggest room for improvement, where intensified efforts and community engagement could enhance outcomes.

5.5. Provincial Cost Simulation for Waste Management

The cost simulation results reveal significant regional cost variations in Costa Rica's waste management, driven by

setup, maintenance, and operational factors unique to each province.

Table 13 provides a breakdown, with

Guanacaste showing the highest costs and

Alajuela the lowest, reflecting regional infrastructure needs. Operational and processing costs also vary, influenced by local waste processing rates and recycling capacities.

Cost savings from RL optimization are modest, with Heredia achieving the highest savings. Conversely, Limón and Cartago show minor negative savings, indicating challenges in RL optimization for these areas. Monte Carlo simulation results further illustrate cost variability, with San José’s mean cost at $422,432.36 USD and a standard deviation of $57,938.49 USD, showing potential cost fluctuations under varying conditions.

These findings highlight the need for tailored regional strategies in waste management, with cost breakdowns guiding policy and investment to enhance sustainability across provinces.

6. Discussion

This study provides a detailed analysis of Costa Rica’s waste management infrastructure, focusing on recycling facility accessibility and policy impacts. Significant accessibility disparities exist between urban and rural areas; for instance, San José achieves 56% household accessibility within a 0–5 km range, while rural regions like Limón and Puntarenas report rates below 30%, underscoring the need for targeted infrastructure development to improve equitable access. Using agent-based modeling (ABM), this study shows that strategic facility placement enhances recycling rates; for example, Cartago achieves a simulated rate of 27.38%, while Puntarenas lags at 7.69% due to geographic constraints. This approach is supported by findings in [

54], which highlight ABM’s suitability for modeling complex waste systems, and [

55], which found that well-placed facilities improve public engagement in urban settings.

The economic analysis reveals notable regional cost differences, with facility setup averaging

$500,000 in rural areas compared to

$300,000–

$400,000 in urban centers. This aligns with [

56], which emphasizes that waste infrastructure investments in Latin America promote job creation, and [

46], which shows that incentive-based waste policies like PAYT reduce waste and costs. This suggests that Costa Rica might adopt similar models to improve financial efficiency and recycling rates. The reinforcement learning (RL) model demonstrates how optimized strategies can enhance recycling rates while reducing landfill use; for instance, Cartago’s recycling rate rose to 53.4% with a 12% decrease in landfill reliance. Additionally, [

57] suggests that integrated solid waste management (ISWM) plays a key role in advancing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by addressing urban-rural waste disparities, indicating that Costa Rica could benefit from similar sustainable approaches.

A sensitivity analysis within the ABM further supports the importance of location-specific facility placements, showing accessibility improvements of up to 25% in rural Guanacaste with facilities added within a 10–20 km range, while San José saw the greatest gains within 0–5 km. These findings align with those in [

58], which report similar infrastructure challenges in urban Colombia, where optimizing facility placement is essential. Improved waste infrastructure provides social and environmental benefits, with increased accessibility potentially reducing landfill volume by up to 15% nationwide, particularly in high-accessibility areas like Alajuela and Cartago. Furthermore, [

59] highlights the role of AI-driven waste categorization for improved accuracy, while [

60] advocates for high-resolution models to enhance infrastructure efficiency, especially in resource-constrained regions. According to [

61], linking waste management practices to the SDGs through systematic waste indicators can strategically support Costa Rica’s sustainability objectives, particularly in urban settings.

[

62] found that incentive-based policies in Canada increased public participation by up to 96.5%, suggesting that Costa Rica could adopt similar models to boost community-driven solutions and tackle rural accessibility challenges. However, limitations in this study include potential data gaps in rural areas and reliance on assumptions in ABM and RL models, which may affect generalizability. Moreover, [

63] demonstrates that waste management interventions in support of a circular economy can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions—a factor critical to Costa Rica’s environmental goals. Finally, [

64] indicates that integrating landfill-based biogas production with leachate treatment aligns with a water-energy nexus approach, further supporting Costa Rica’s goals of sustainable waste and resource management.

Future research could explore tailored engagement strategies for rural communities, advanced RL applications across diverse waste contexts, and AI-driven categorization models for improved efficiency. Longitudinal studies on the impact of infrastructure expansion on recycling and environmental outcomes would provide valuable insights for refining Costa Rica’s waste management policies.

7. Conclusion

This study analyzes Costa Rica’s waste management infrastructure, highlighting significant accessibility disparities between urban and rural areas. Through Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), Reinforcement Learning (RL), and cost simulations, the research identifies critical gaps in access, emphasizing the need for region-specific infrastructure improvements.

The results show that urban centers like San José have household accessibility rates up to 56% within 0–5 km, while rural areas such as Limón and Puntarenas remain below 30%, underscoring geographic and infrastructural barriers in underserved communities. Simulation findings reveal the potential of strategically placed facilities to improve recycling behaviors, with Cartago projected to reach a 27.38% recycling rate compared to Puntarenas at 7.69%. The economic analysis highlights the cost challenges in rural regions, where setup costs average $500,000 versus $300,000–$400,000 in urban areas, reinforcing the need for cost-effective, policy-driven interventions.

The RL model shows that optimized strategies could boost recycling rates by up to 53.4% and reduce landfill dependency by 12% in areas like Cartago, suggesting that data-driven, adaptable approaches could enhance waste management outcomes. Sensitivity analysis also demonstrates that adjusting facility placements to local demographics could significantly improve accessibility in challenging areas.

Achieving sustainable waste management in Costa Rica will require a multi-pronged approach, combining strategic infrastructure expansion, tailored policies, and potentially AI-driven technologies to increase waste processing efficiency. Future research on public engagement and longitudinal studies could provide valuable insights for refining policy and adapting to evolving regional needs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Andrea Navarro Jimenez developed the research idea, designed the study, gathered and analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any particular funding from governmental, corporate, or charitable sources.

Ethics Statement

This study did not involve any research on human subjects, human data, human tissue, or animals. Therefore, no ethical approval was required.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the findings of this study, including the Python scripts and

supplementary materials, is openly available in Mendeley Data under the title: "Optimizing Waste Management in Costa Rica: Leveraging Agent-Based and Reinforcement Learning Models for Equitable Recycling Access" (Navarro, Andrea, 2024), Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/wwf8xxh3py.1.

Conflict of Interest Declaration

The author confirms that no conflicts of interest are associated with the publication of this manuscript.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to improve grammar and readability.

References

-

United Nations. (2023). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

-

Javed, M. W., Saleem, F., Aslam, F., & Ullah, K. (2024). Urban-rural sustainability challenges and infrastructure disparities in developing countries: Policy perspectives for inclusive growth. Journal of Environmental Management, 317, 115721.

-

Ferronato, N., Torretta, V., Gullo, S., & Chiavola, A. (2024). Challenges and perspectives of waste management and circular economy in developing countries. Sustainable Cities and Society, 67, 105919.

-

Graham, C. C. (2024a). The role of Geographic Information Systems in mitigating plastics pollution in the Global South—A spatial analysis of recycling facilities in Costa Rica. Science of the Total Environment, 937, 173396. [CrossRef]

-

Bravo, L. M. R., Cosio Borda, R. F., Quispe, L. A. M., Rodríguez, J. A. P., Ober, J., & Khan, N. A. (2024). The role of internet and social interactions in advancing waste sorting behaviors in rural communities. Resources, 13(4), 57. [CrossRef]

-

Baltodano-Goulding, R., & Poveda-Montoya, A. (2023). Unsaturated seepage analysis for an ordinary solid waste sanitary landfill in Costa Rica. E3S Web of Conferences. [CrossRef]

-

Bhattacharya, S., Kalita, H., & Kumar, R. (2024). Fuzzy synthetic evaluation approach for economic risk assessment in waste management systems. Journal of Environmental Management, 325, 116807.

-

Le Page, C., Becu, N., Bommel, P., & Bousquet, F. (2013). Agent-based modeling and simulation applied to environmental management. Agricultural Systems, 116, 10-15. [CrossRef]

-

Sert, E., Bar-Yam, Y., & Morales, A. J. (2020). Segregation dynamics with reinforcement learning and agent-based modeling. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 11771. [CrossRef]

-

Herrera-Murillo, J., Rojas-Marín, J. F., & Anchía-Leitón, D. (2016). Tasas de generación y caracterización de residuos sólidos ordinarios en cuatro municipios del Área Metropolitana Costa Rica. [CrossRef]

-

Campos Rodríguez, R., & Soto Córdoba, S. M. (2014). Estudio de generación y composición de residuos sólidos en el cantón de Guácimo, Costa Rica. Tecnología en Marcha, 27.

-

Chaves Brenes, K. (2024, February 14). San José: ecoins – promoting the circular economy and decarbonisation through public-private partnerships. International Institute for Environment and Development. Available online: https://www.iied.org/san-jose-ecoins-promoting-circular-economy-decarbonisation-through-public-private-partnerships.

-

OECD. (2023). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Costa Rica 2023. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

-

Becerra, E. (2021, March 18). Waste management ‘one of biggest environmental problems,’ Costa Rica says. The Tico Times. Available online: https://ticotimes.net/2021/03/18/waste-management-one-of-biggest-environmental-problems-costa-rica-says.

-

Quesada Cordero, M. (2024, April 8). How many Costa Ricans participate in recycling? El Colectivo 506. Available online: https://elcolectivo506.com.

-

Ministerio de Ambiente y Energía, Costa Rica. (2023). Estrategias sostenibles de gestión de residuos. Gobierno de Costa Rica. Available online: https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/prensa/43-noticias-2021/866-gobierno-presenta-plan-de-accion-para-la-gestion-integral-de-residuos.

-

European Environment Agency. (2023). Waste recycling in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/waste-recycling-in-europe.

-

Landgeist. (2024). Germany: Recycling Rate. Available online: https://landgeist.com/2024/04/06/recycling-rate/.

-

Recycling Partnership. (2024). State of Residential Recycling in the U.S. Retrieved from the uploaded document. Available online: recyclingpartnership.org.

-

Klein, C. (2024). Recycling rate of waste Japan FY 2013-2022. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1127509/japan-recycling-rate-waste/.

-

Gerden, E. (2024). Brazil’s recycling best is yet to come. Available online: https://recyclinginternational.com/latest-articles/brazils-recycling-best-is-yet-to-come/57145/.

-

Seoul Metropolitan Government. (2023). Seoul to increase recycling rate to 79% by 2026. Available online: https://english.seoul.go.kr/seoul-to-increase-recycling-rate-to-79-by-2026/.

-

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. (2024). Swedish recycling and beyond. Available online: https://sweden.se/climate/sustainability/swedish-recycling-and-beyond.

-

Ministerio de Salud de Costa Rica. (2023). Informe Anual de Gestión Ambiental 2023. Available online: https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/informes-de-gestion.

-

Gómez, C. C. (2023). Circular economy plastic policies in Costa Rica: A critical policy analysis. Circular Innovation Lab. ISBN 978-87-94507-05-9.

-

Holland Circular Hotspot. (2021). Waste Management Country Report: Costa Rica

. Available online: https://hollandcircularhotspot.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Report_Waste_Management_Costa_Rica_20210329.pdf.

-

Procuradoria de la Republica de Costa Rica: "Ley para Combatir la Contaminación por Plástico y Proteger el Ambiente, N° 9786." Sistema Costarricense de Información Jurídica. Available online: http://www.pgrweb.go.cr/scij/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?nValor1=1&nValor2=90187 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

-

Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety, and Consumer Protection (BMUV). (2023). Waste management in Germany 2023: Facts, data, figures

. Available online: https://www.bmuv.de/.

-

World Intellectual Property Organization. (2024). Global Innovation Index 2024: Unlocking the Promise of Social Entrepreneurship. Geneva: WIPO. [CrossRef]

-

Lino, F. A. M., Ismail, K. A. R., & Castañeda-Ayarza, J. A. (2023). Municipal solid waste treatment in Brazil: A comprehensive review. Energy Nexus, 11, 100232. [CrossRef]

-

Kwon, Y., Lee, S., Bae, J., Park, S., Moon, H., Lee, T., Kim, K., Kang, J., & Jeon, T. (2024). Evaluation of incinerator performance and policy framework for effective waste management and energy recovery: A case study of South Korea. Sustainability, 16(1), 448. [CrossRef]

-

Sandhi, A., & Rosenlund, J. (2024). Municipal solid waste management in Scandinavia and key factors for improved waste segregation: A review. Cleaner Waste Systems, 8, 100144. [CrossRef]

-

Arias. (2024). Challenges and opportunities in waste management: Perspectives from Costa Rica for the world recycling day. Arias Knowledge Center. Available online: https://ariasknowledgecenter.com.

-

Tico Times. (2024, November 1). ICE unveils biogas plan to combat Costa Rica’s growing waste management crisis. The Tico Times. Available online: https://ticotimes.net/2024/11/01/ice-unveils-biogas-plan-to-combat-costa-ricas-growing-waste-management-crisis.

-

Graham, H. (2024b). GIS-based approaches in managing plastic pollution: A case study of the Global South. Journal of Environmental Mapping and Assessment, 21(2), 113-130.

-

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. (2022). Estimación de población y vivienda: Provincias de Costa Rica. INEC. Available online: https://inec.cr.

-

Mitchell, A. (1999). The ESRI guide to GIS analysis volume 1: Geographic patterns & relationships. ESRI Press.

-

Devore, J. L. (2011). Probability and statistics for engineering and the sciences (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. Available online: https://faculty.ksu.edu.sa/.

-

Miller, H. J., & Shaw, S. (2001). Geographic information systems for transportation: Principles and applications. Oxford University Press.

-

Zhang, H., Liu, P., Guo, X., Wang, J., Qin, S., Qi, L., & Zhao, J. (2022). An improved Q-learning algorithm for solving disassembly line balancing problem considering carbon emission. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) (pp. 872-877). Prague, Czech Republic: IEEE. [CrossRef]

-

Liu, Y., Zhou, M., & Guo, X. (2022). An improved Q-learning algorithm for human-robot collaboration two-sided disassembly line balancing problems. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) (pp. 568-573). Prague, Czech Republic: IEEE. [CrossRef]

-

Fernandez, I. (2024, July 17). Costa Rica on the brink of a garbage crisis. The Tico Times. Available online: https://ticotimes.net/2024/07/17/costa-rica-on-the-brink-of-a-garbage-crisis.

-

Espinosa-Aquino, B., Gabarrell Durany, X., & Quirós Vargas, R. (2023). The role of informal waste management in urban metabolism: A review of eight Latin American countries. Sustainability, 15(1826). [CrossRef]

-

Estado de la Nación. (2010). Data on CO₂ emissions from Costa Rican landfills. Available online: https://estadonacion.or.cr/.

-

Hidalgo Arroyo, I. (2021, July 2). Ahora podrá adquirir ecoins cada vez que deposite residuos ordinarios de forma correcta. Delfino CR. Available online: https://delfino.cr.

-

Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad (ICE) (2022), Biogas Project. Available online: https://www.grupoice.com/.

-

Vega, L. P., Bautista, K. T., Campos, H., Daza, S., & Vargas, G. (2024). Biofuel production in Latin America: A review for Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica, and Colombia. Energy Reports, 11, 28-38. [CrossRef]

-

Messina, G., Tiezzi, E., Marchettini, N., & Bastianoni, S. (2023). ‘Pay as you own’ or ‘pay as you throw’? A counterfactual evaluation of alternative financing schemes for waste services. Ecological Economics, 207, 107701.

-

Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad. (2024). Tarifas enero 2024: Alcance N°257 Gaceta N°237. Available online: https://www.tarifas.cr.

-

GlobalPetrolPrices.com. (2024). Costa Rica Precios de la gasolina. Available online: https://es.globalpetrolprices.com/Costa-Rica/gasoline_prices/.

-

Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. (2021). Solid waste management in Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org.

-

Ministerio de Salud de Costa Rica. (2021). Report waste management Costa Rica. Available online: https://www.wastemanagementcostarica.cr.

-

Ministerio de Salud de Costa Rica. (2022). Política Nacional de Gestión Integral de Residuos 2022-2032: Línea base para la gestión integral de residuos. Available online: https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/.

-

Ding, L., Zheng, Y., Wang, X., & Lu, W. (2018). System dynamics versus agent-based modeling: A review of complexity simulation in construction waste management. Sustainability, 10(7), 2484. [CrossRef]

-

Qiao, Z., Li, J., & Huang, X. (2024). Incorporating decentralized facilities into the food waste treatment infrastructure in megacity: A locational optimization in Beijing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 427, 135981.

-

Esteves, F., Molina-Perez, E., Kalra, N., Syme, J., & Vogt-Schilb, A. (2024). Job creation and decarbonization synergies in Latin America: A simulation-based exploratory modeling analysis. Frontiers in Climate, 6, 1339877. [CrossRef]

-

Elsheekh, K. M., Kamel, R. R., Elsherif, D. M., & Shalaby, A. M. (2021). Achieving sustainable development goals from the perspective of solid waste management plans. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science, 68(5). [CrossRef]

-

Giraldo-Almario, I., Rueda-Saa, G., & Uribe-Ceballos, J. R. (2024). Wasteaware adaptation to the context of a Latin American country: Evaluation of the municipal solid waste management in Cali, Colombia. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 26(3), 908-922. [CrossRef]

-

Spirito, C. (2024). Artificial intelligence applications in reverse logistics: How technology could improve return and waste management creating value (Master's thesis, Politecnico di Torino). Available online: https://https://webthesis.biblio.polito.it/.

-

DelaPaz-Ruíz, N., Augustijn, E.-W., Farnaghi, M., & Zurita-Milla, R. (2023). Modeling spatiotemporal domestic wastewater variability: Implications for measuring treatment efficiency. Journal of Environmental Management, 351, 119680. [CrossRef]

-

Ram, M., & Bracci, E. (2024). Waste management, waste indicators, and the relationship with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 16(8486). [CrossRef]

-

Fontaine, M., Wang, C., & Boulanger, P. (2024). Sustainability and environmental performance in selective collection of residual materials: Impact of modulating citizen participation through policy and incentive implementation. Resources, 13, 151.

-

Paes, M. X., Puppim de Oliveira, J. A., Mancini, S. D., & Rieradevall, J. (2024). Waste management intervention to boost circular economy and mitigate climate change in cities of developing countries: The case of Brazil. Habitat International, 143, 102990. [CrossRef]

-

Abedi, S., Nozarpour, A., & Tavakoli, O. (2023). Evaluation of biogas production rate and leachate treatment in landfill through a water-energy nexus framework for integrated waste management. Energy Nexus, 11, 100218. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

is the maximum expected reward for the next state.

is the maximum expected reward for the next state.