Submitted:

02 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Development

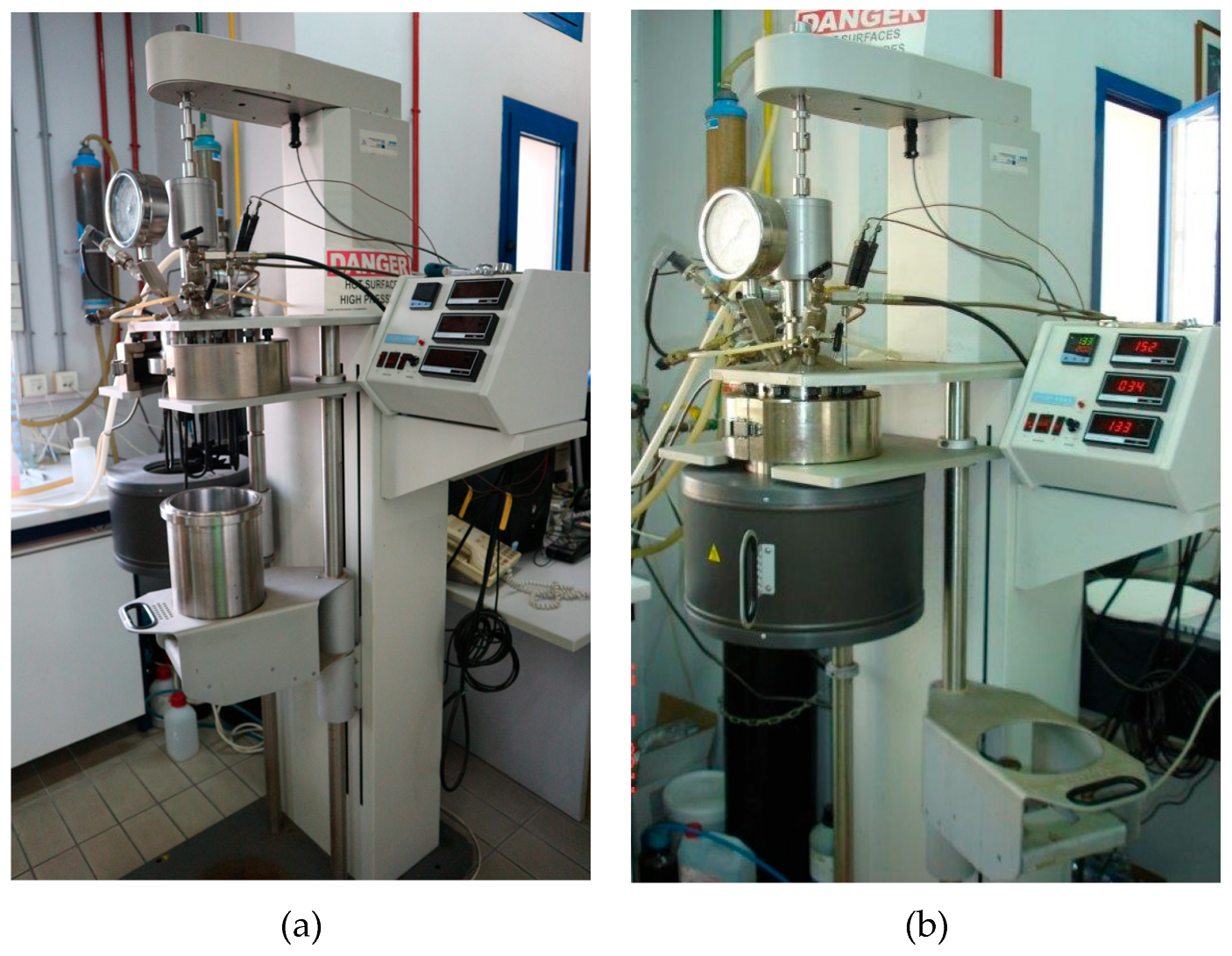

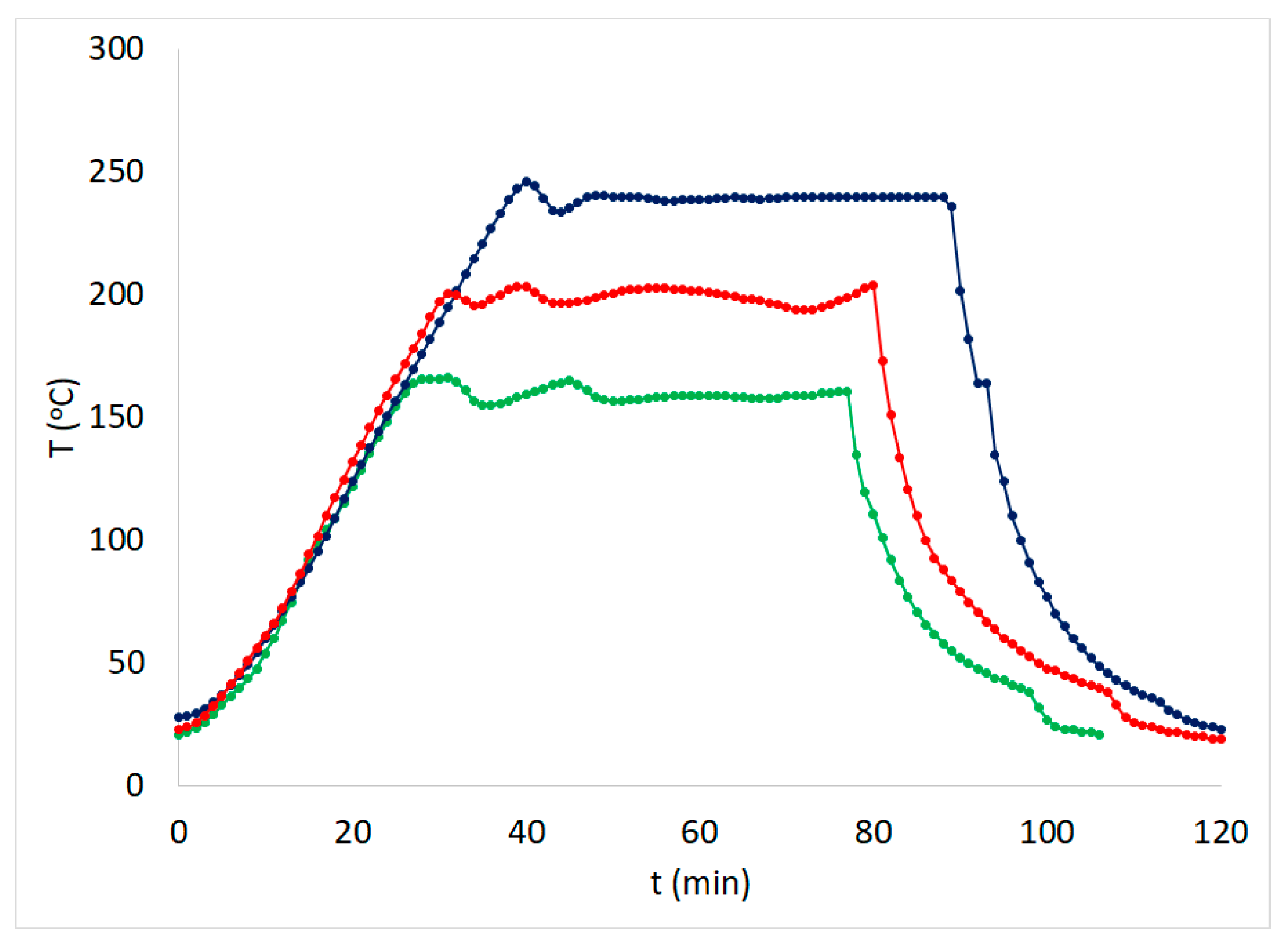

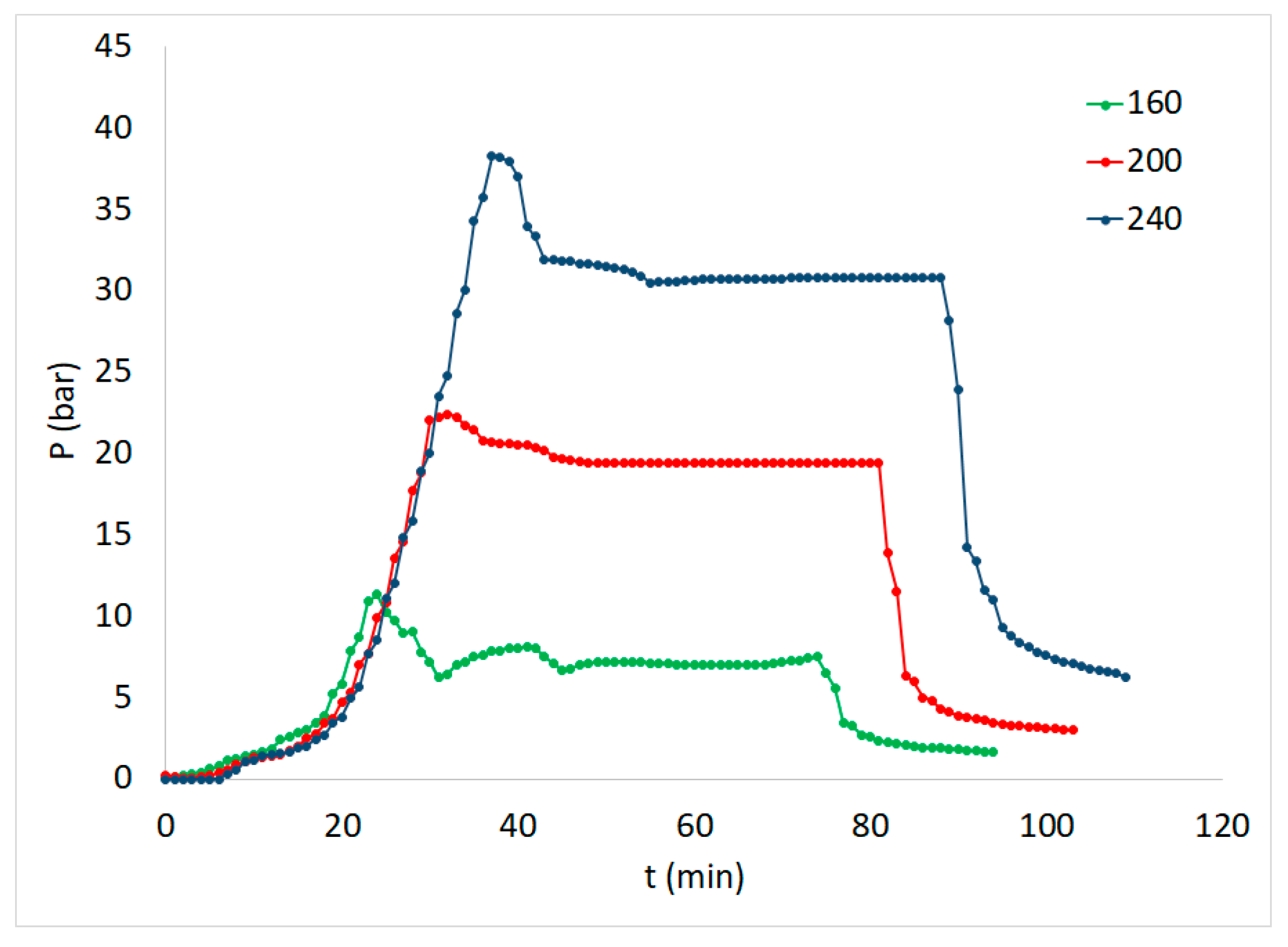

2.2. Sawdust-Brine Treatment Process

2.3. Adsorbate

2.4. Adsorption Isotherms Studies

2.5. Kinetics of Adsorption

2.6. Experimental Design

2.7. Combined Severity Factor

2.8. Other Analytical Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

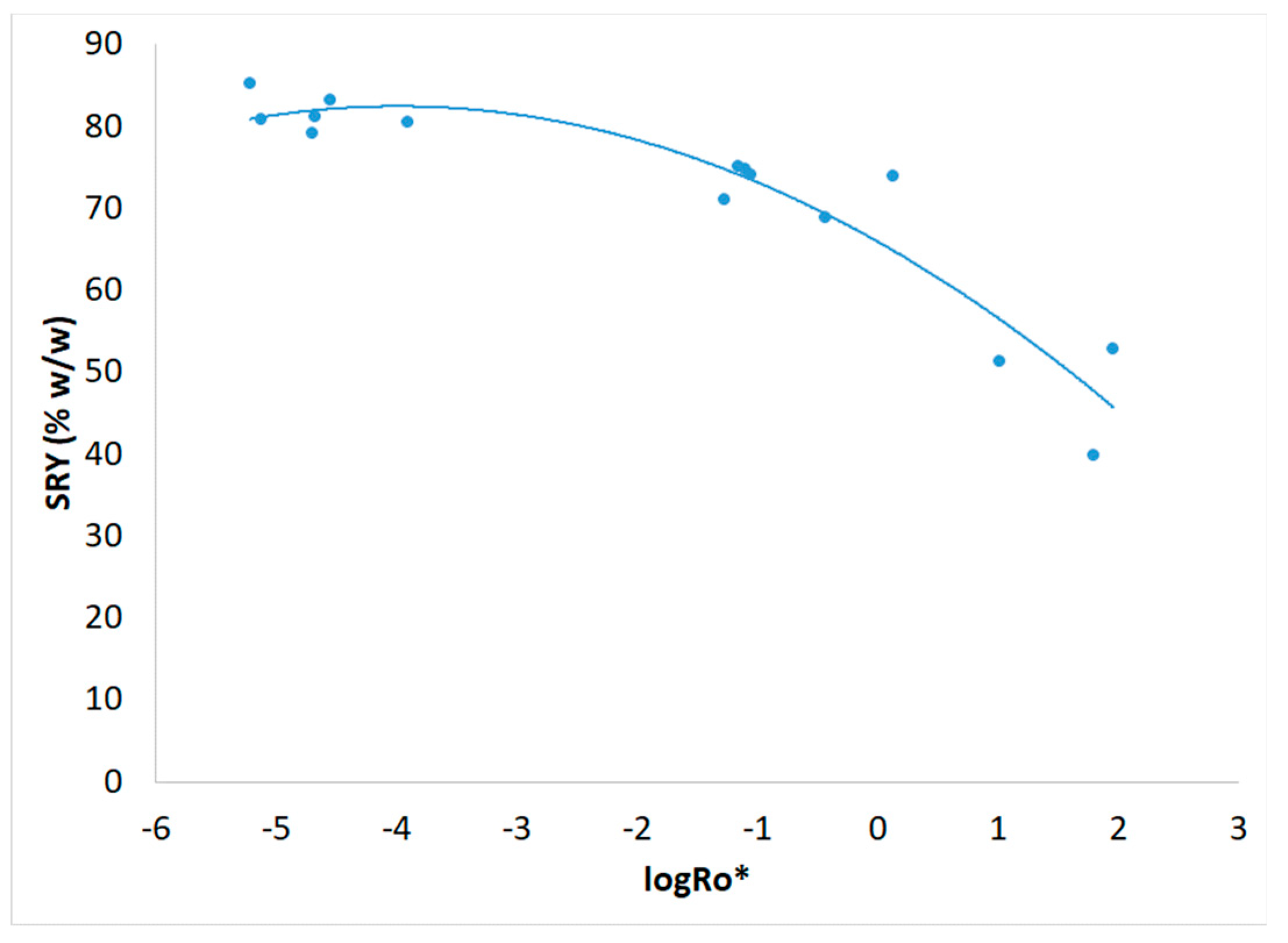

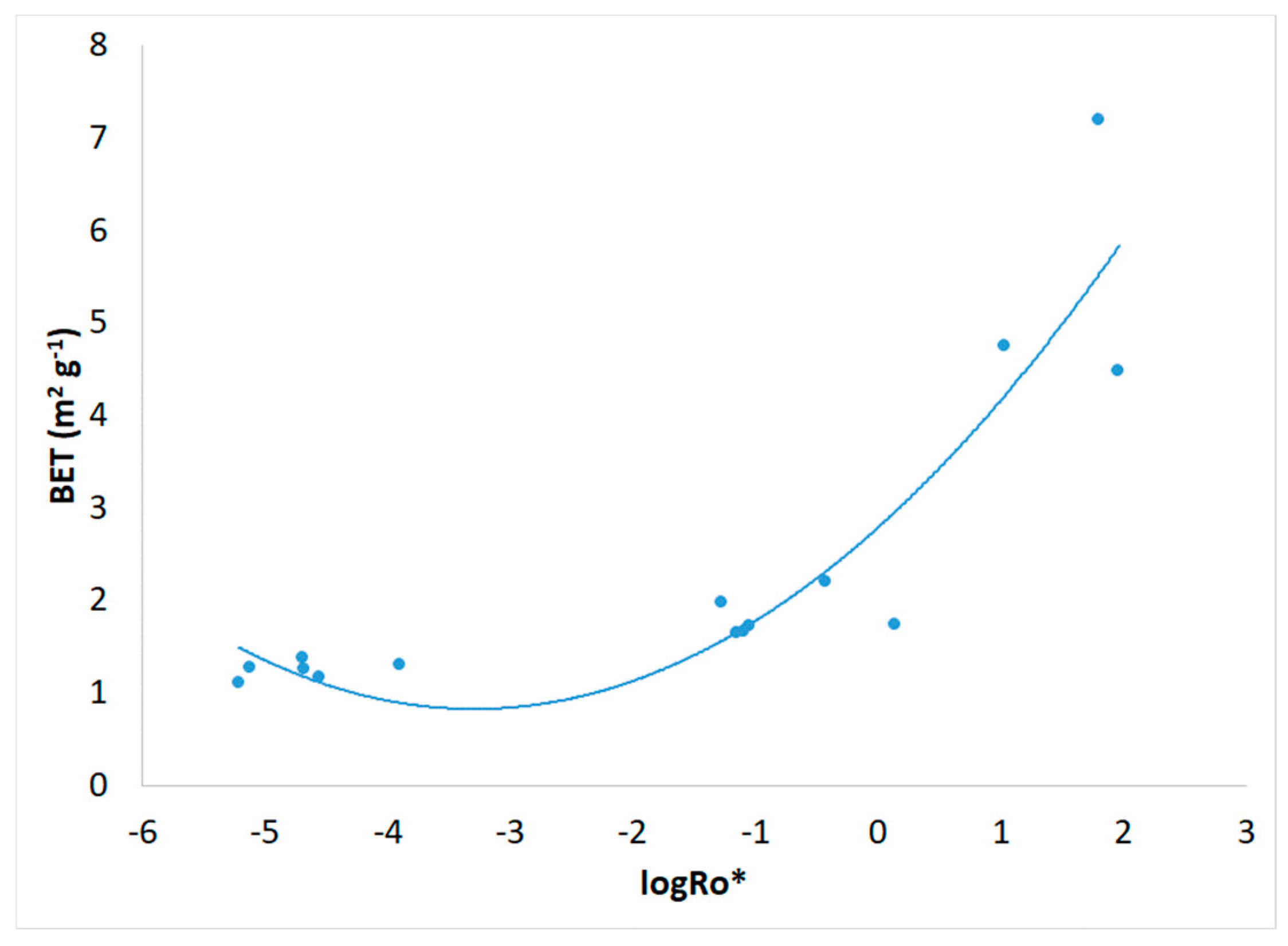

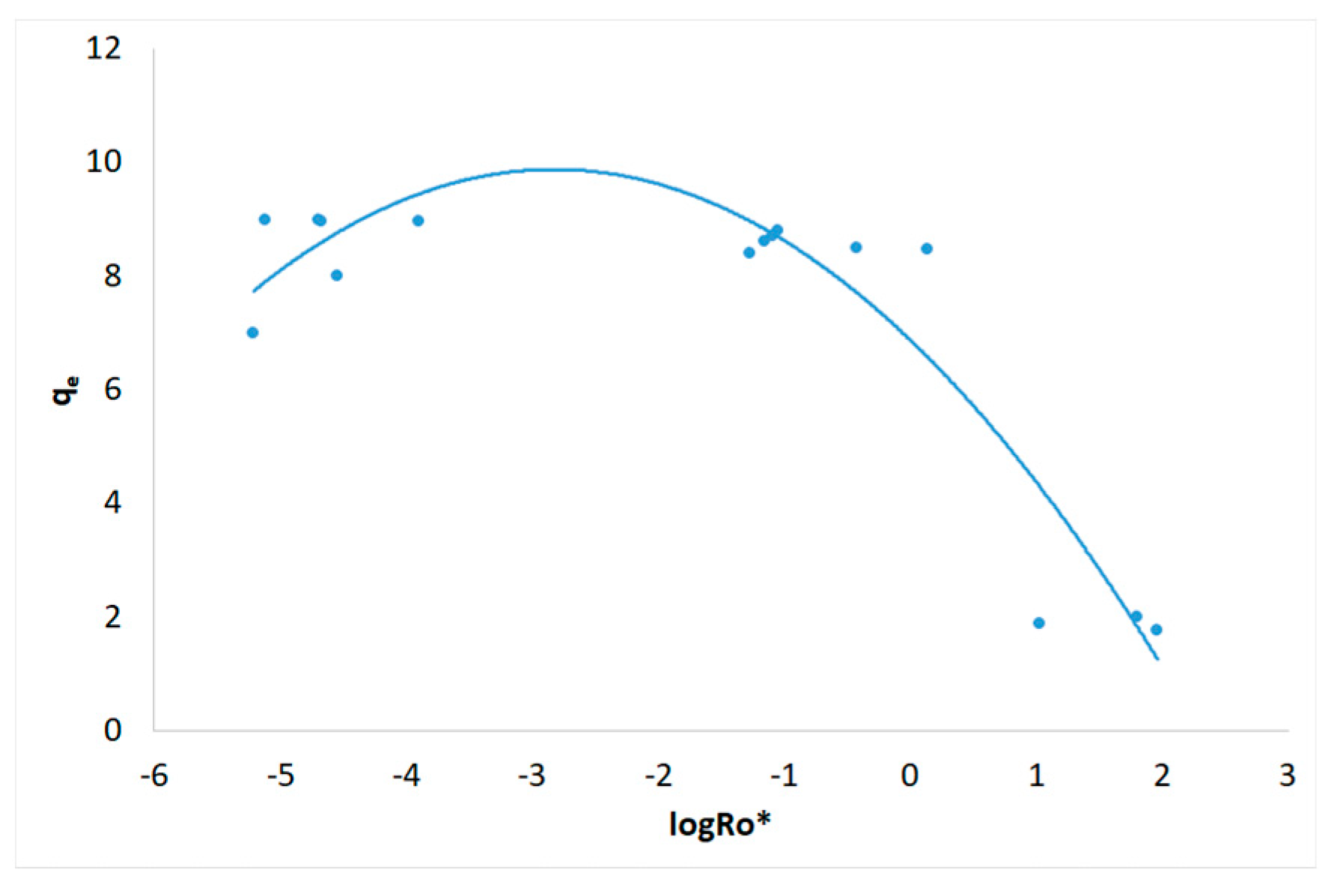

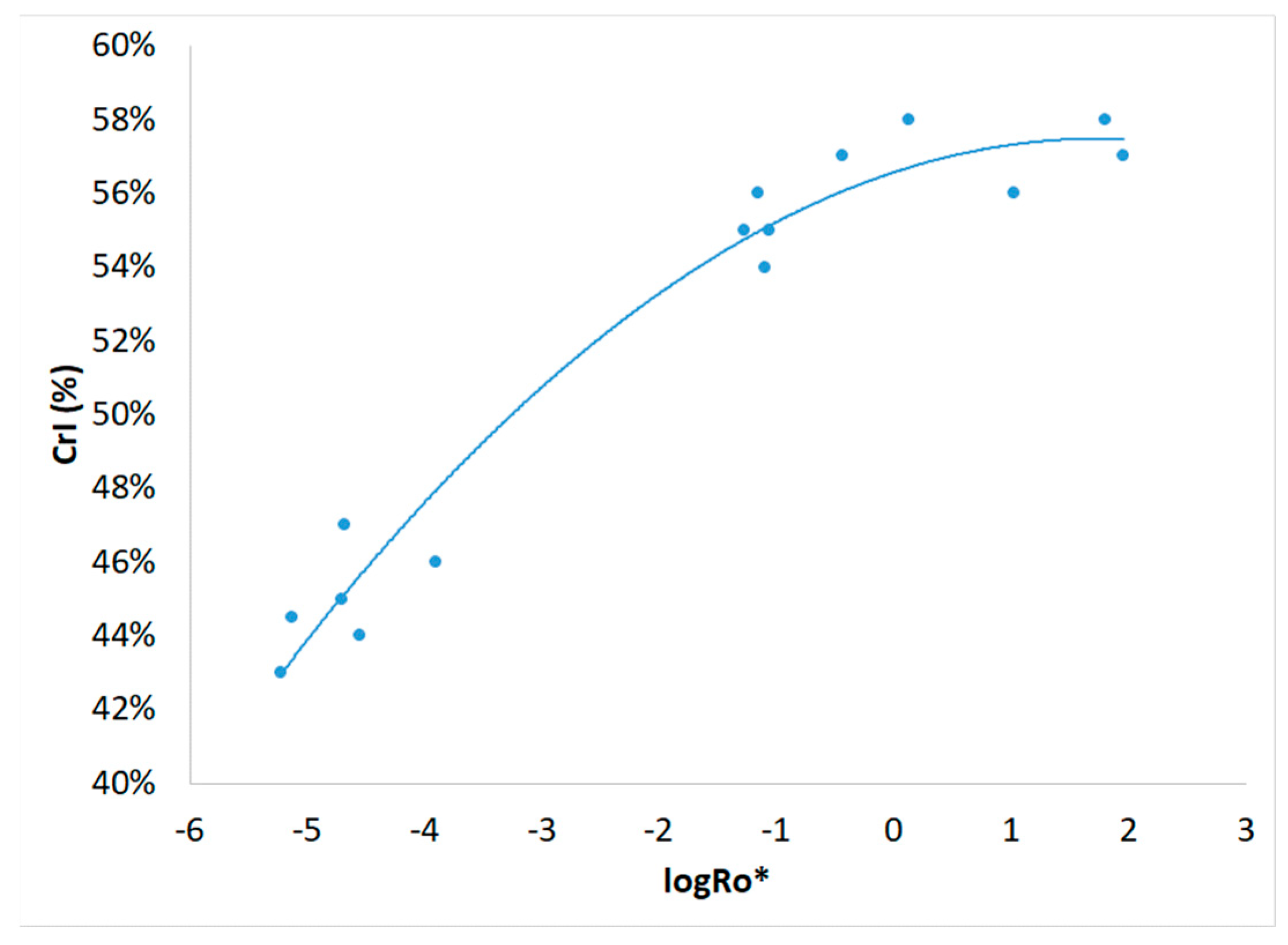

3.1. Severity Factor and Combined Severity Factor Calculations

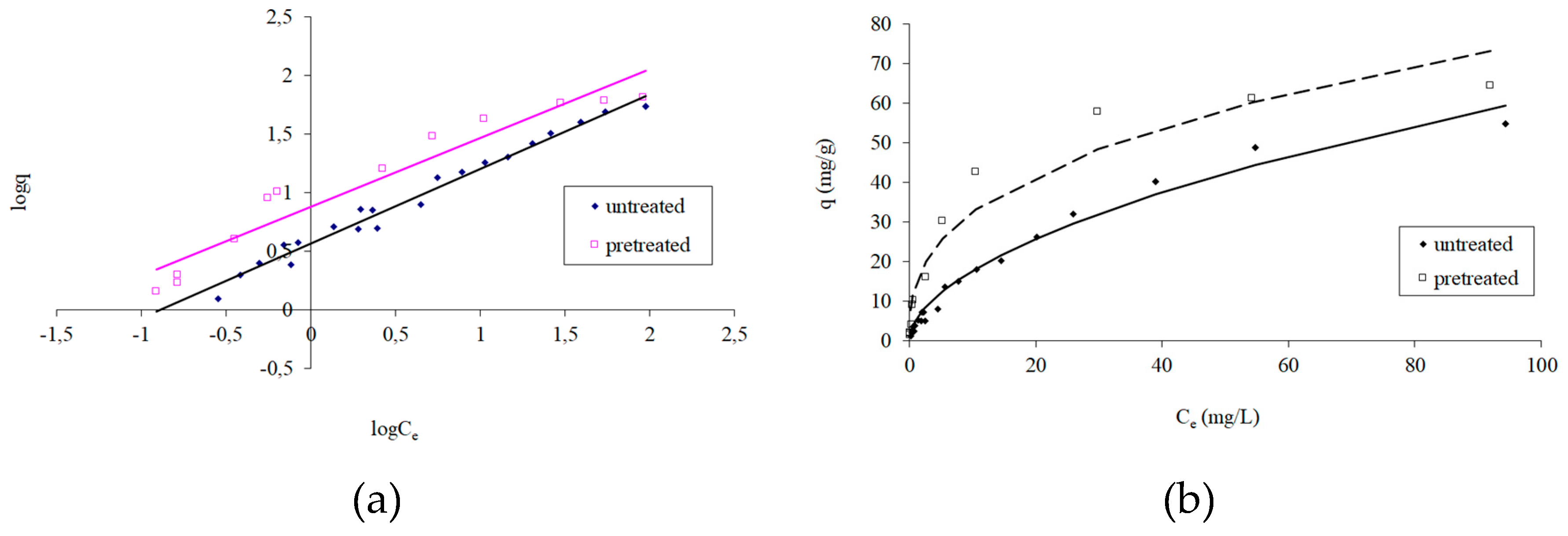

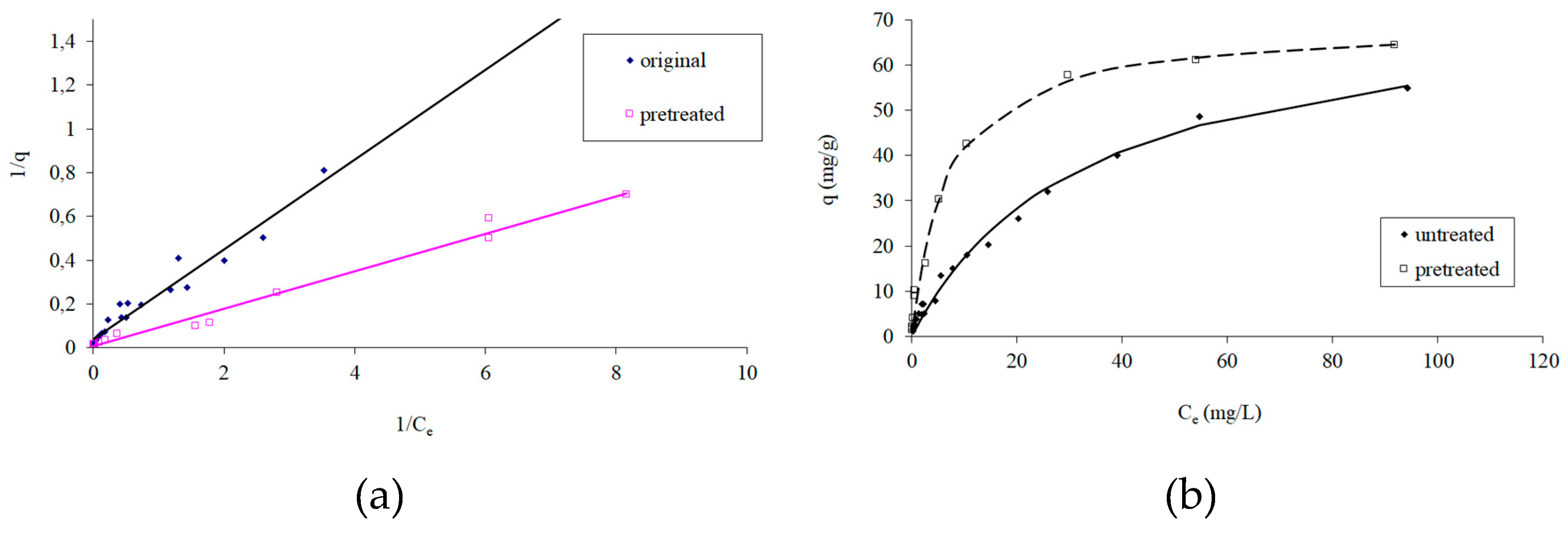

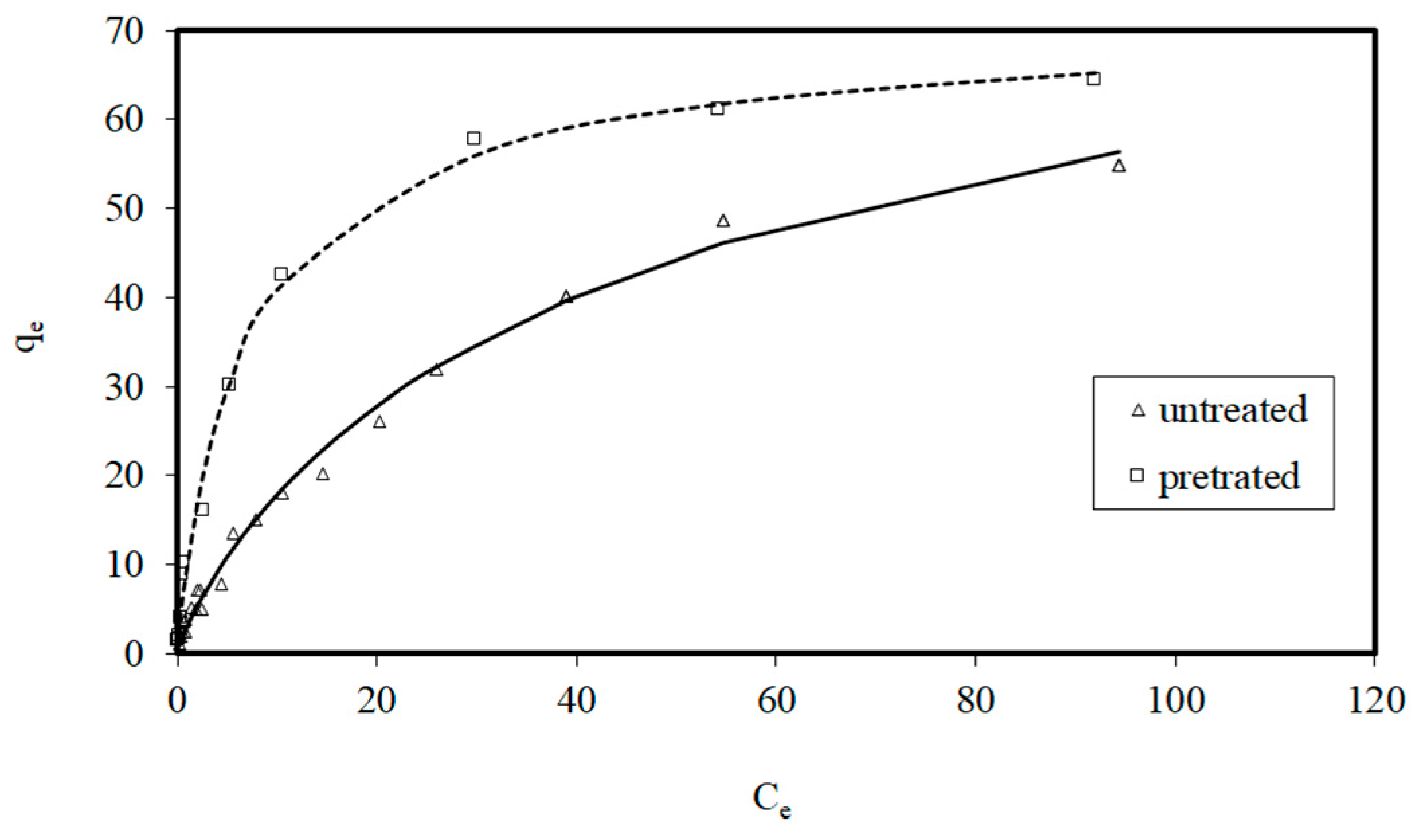

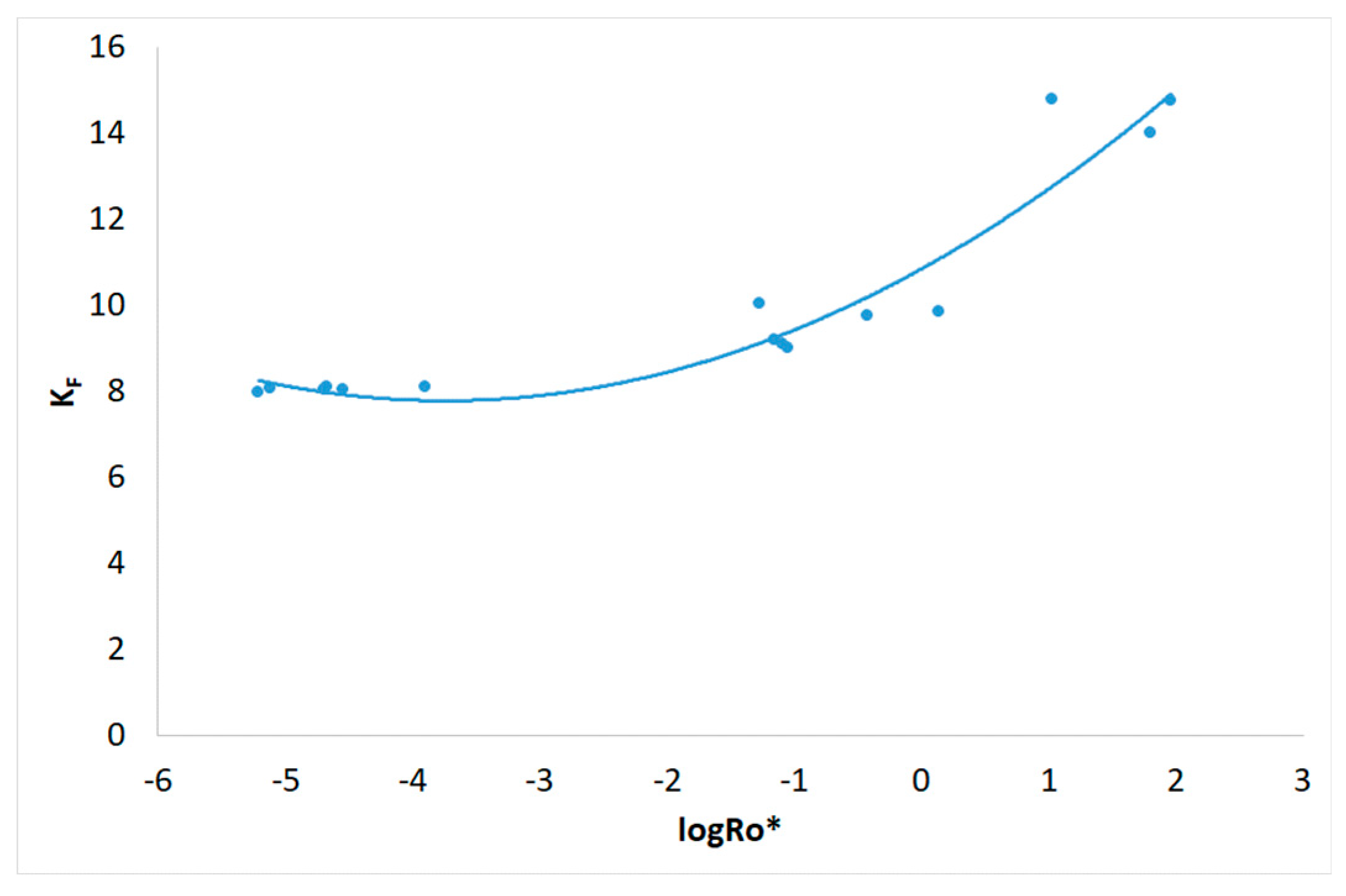

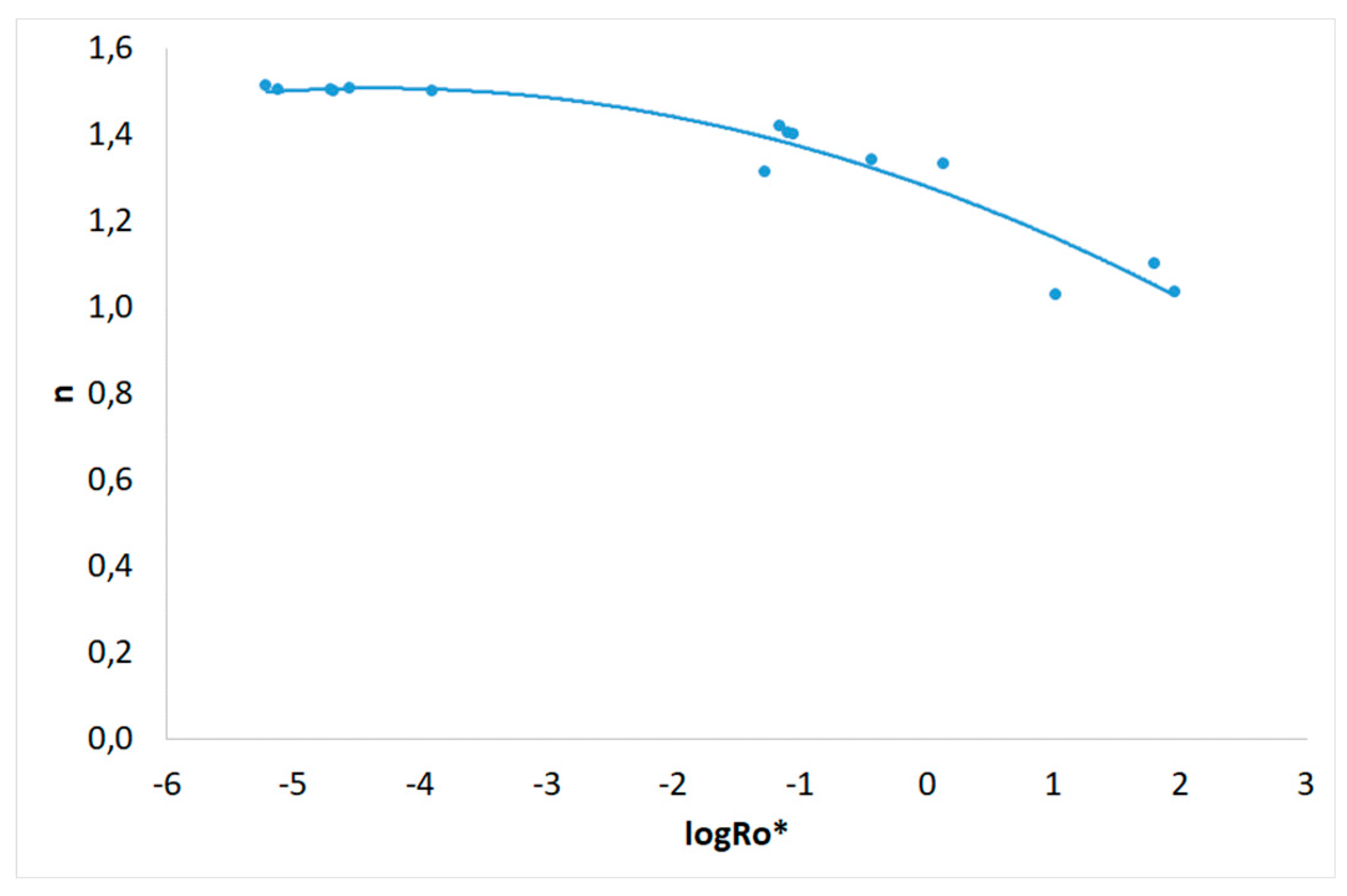

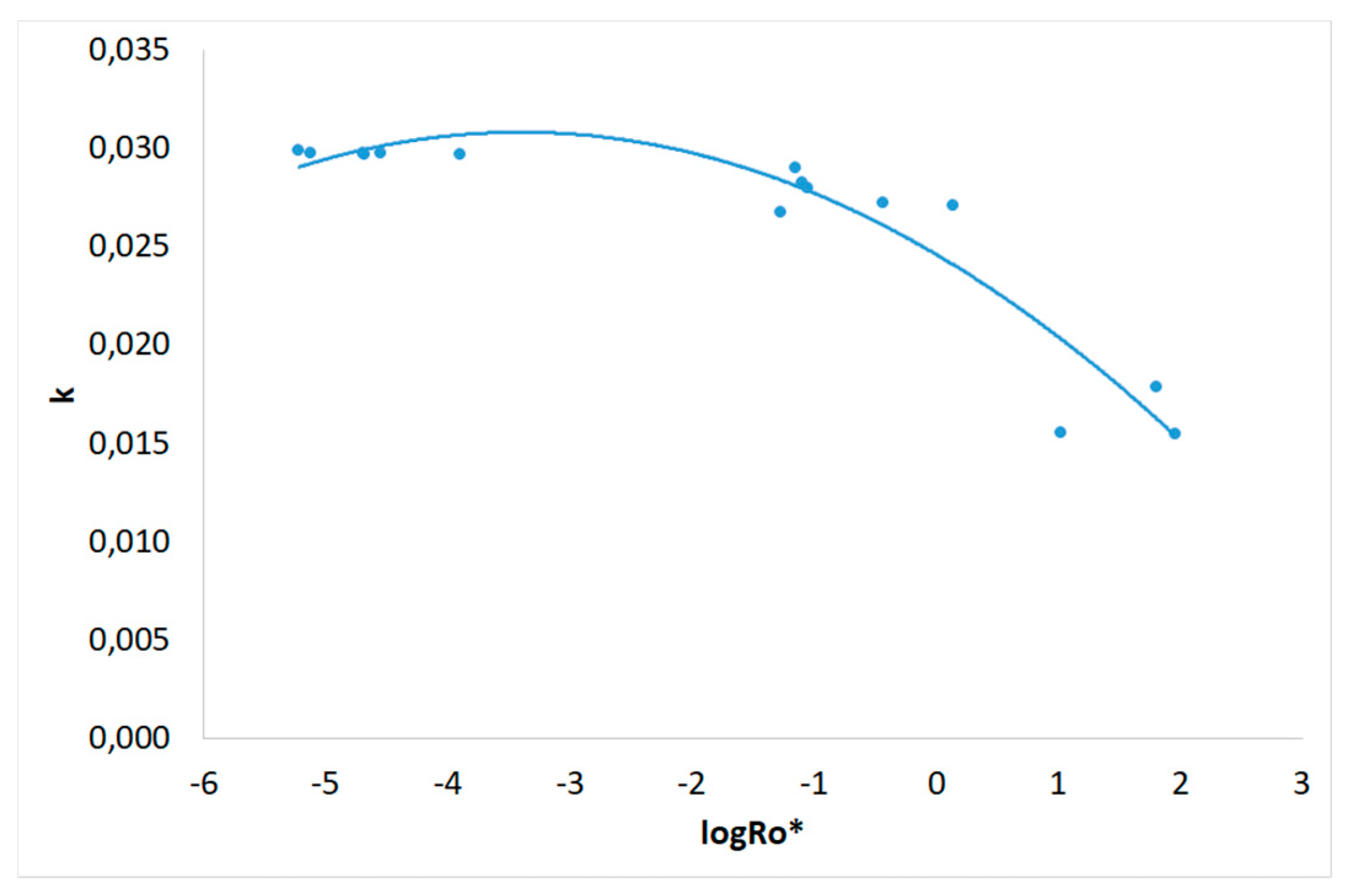

3.2. Adsorption Isotherms

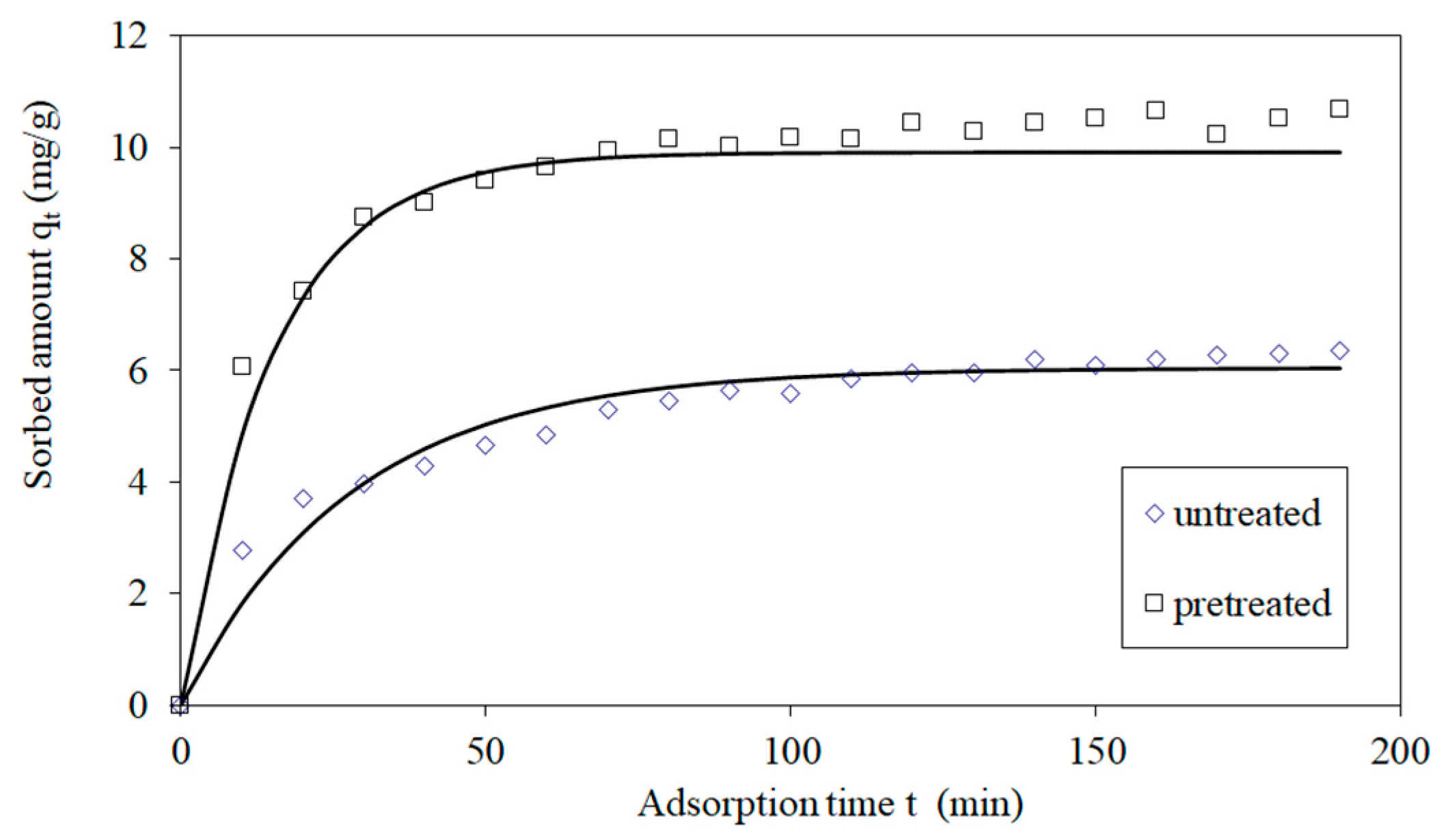

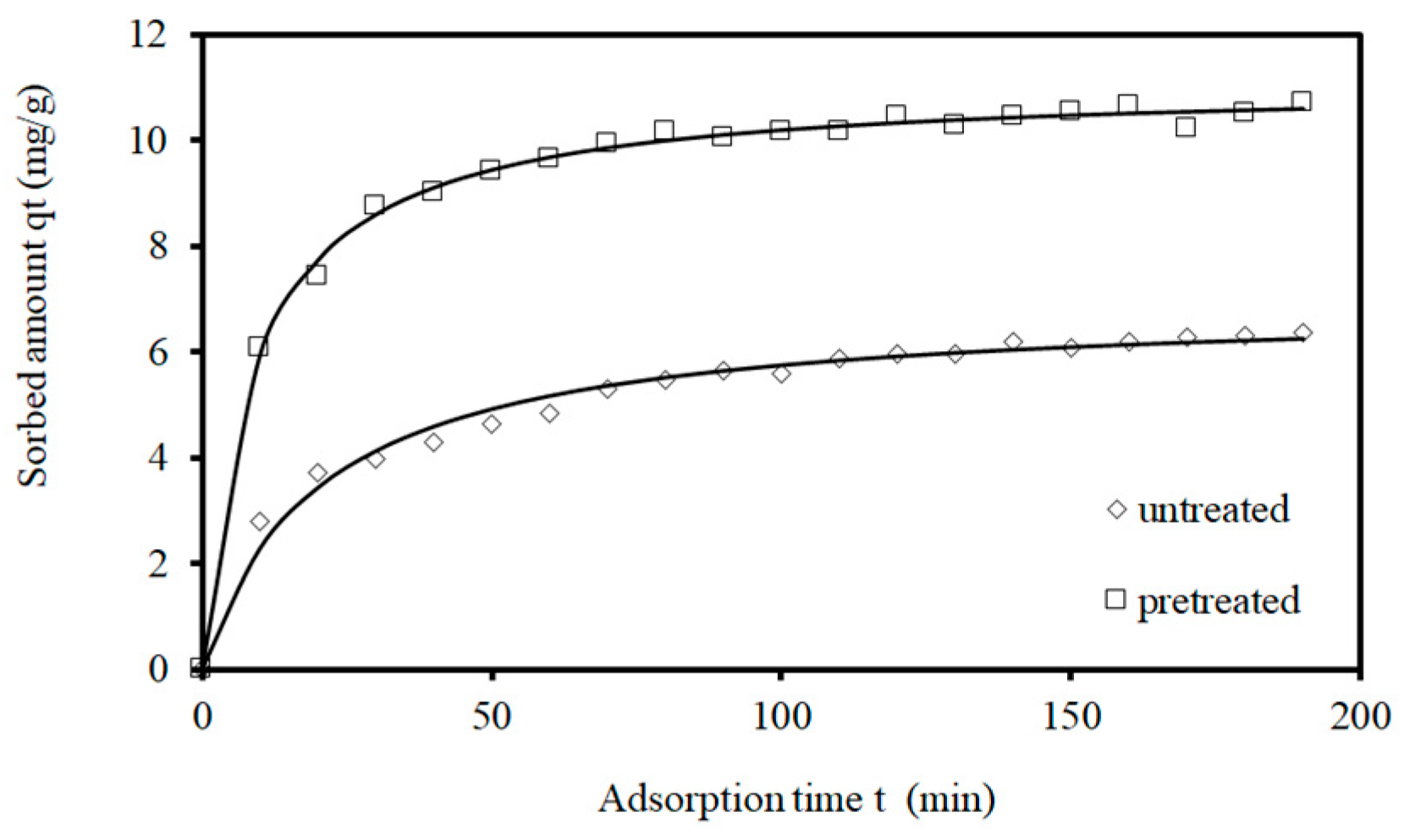

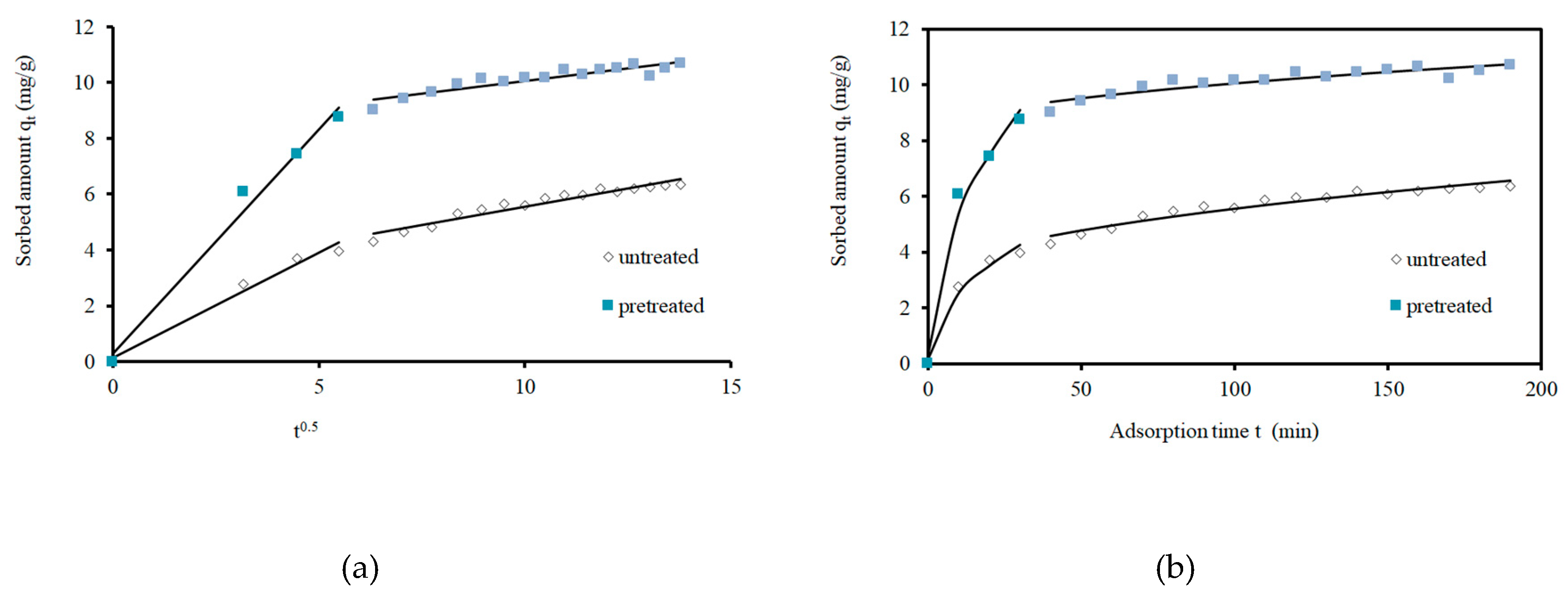

3.3. Kinetics of Adsorption

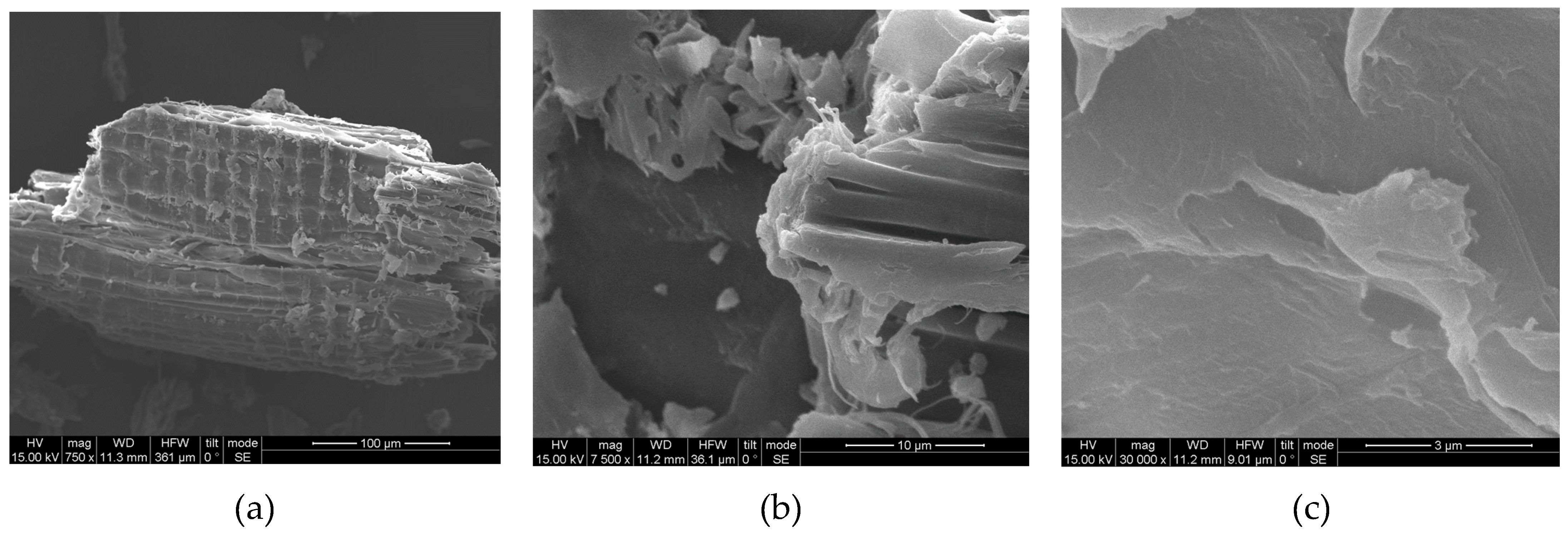

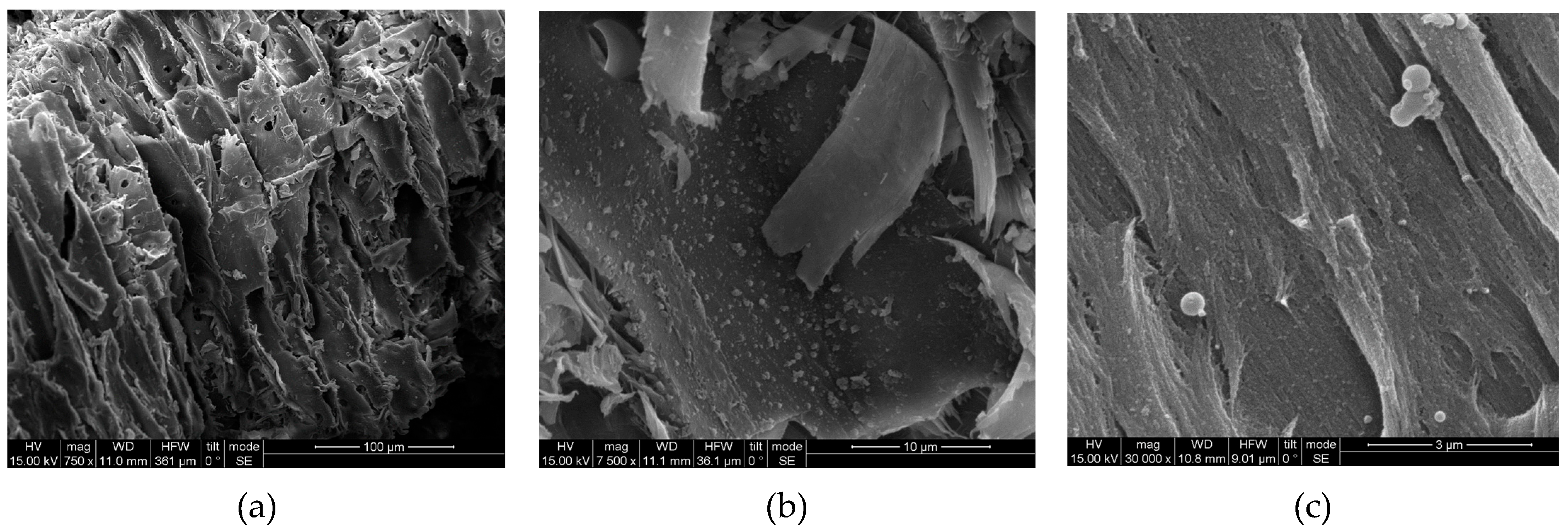

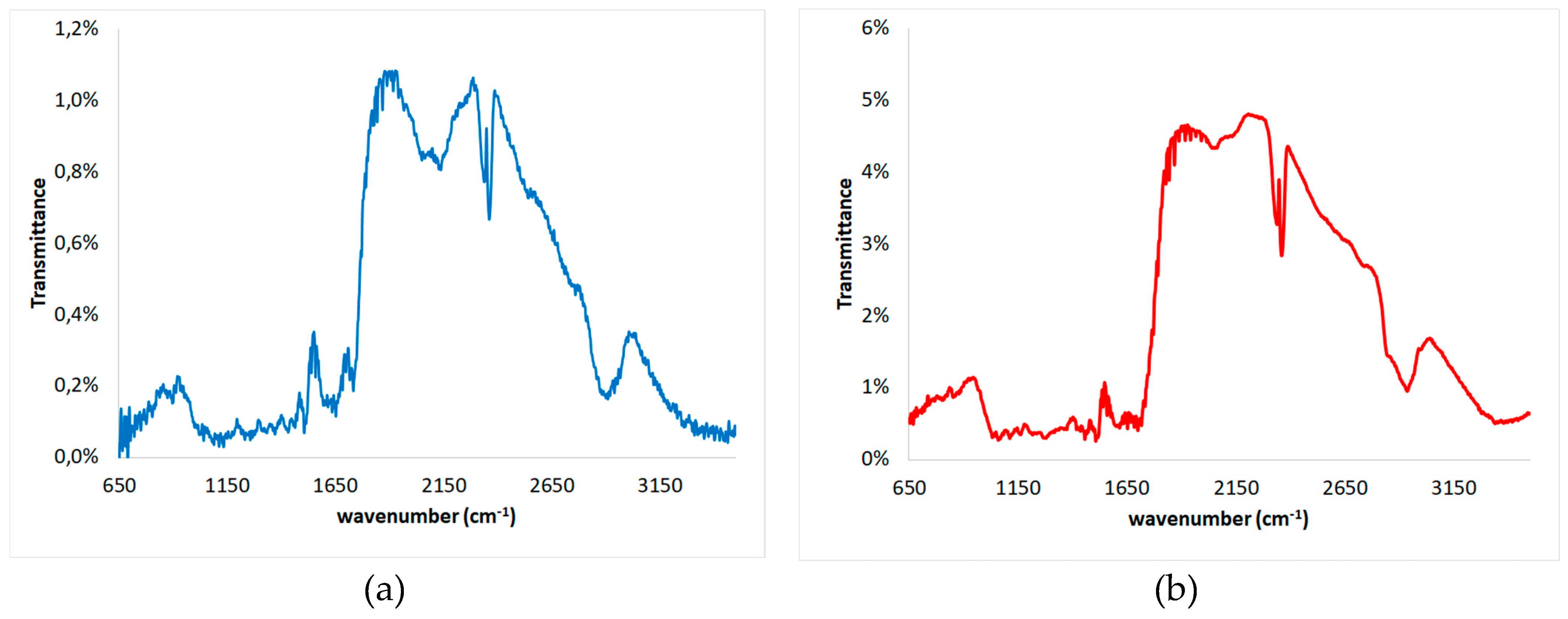

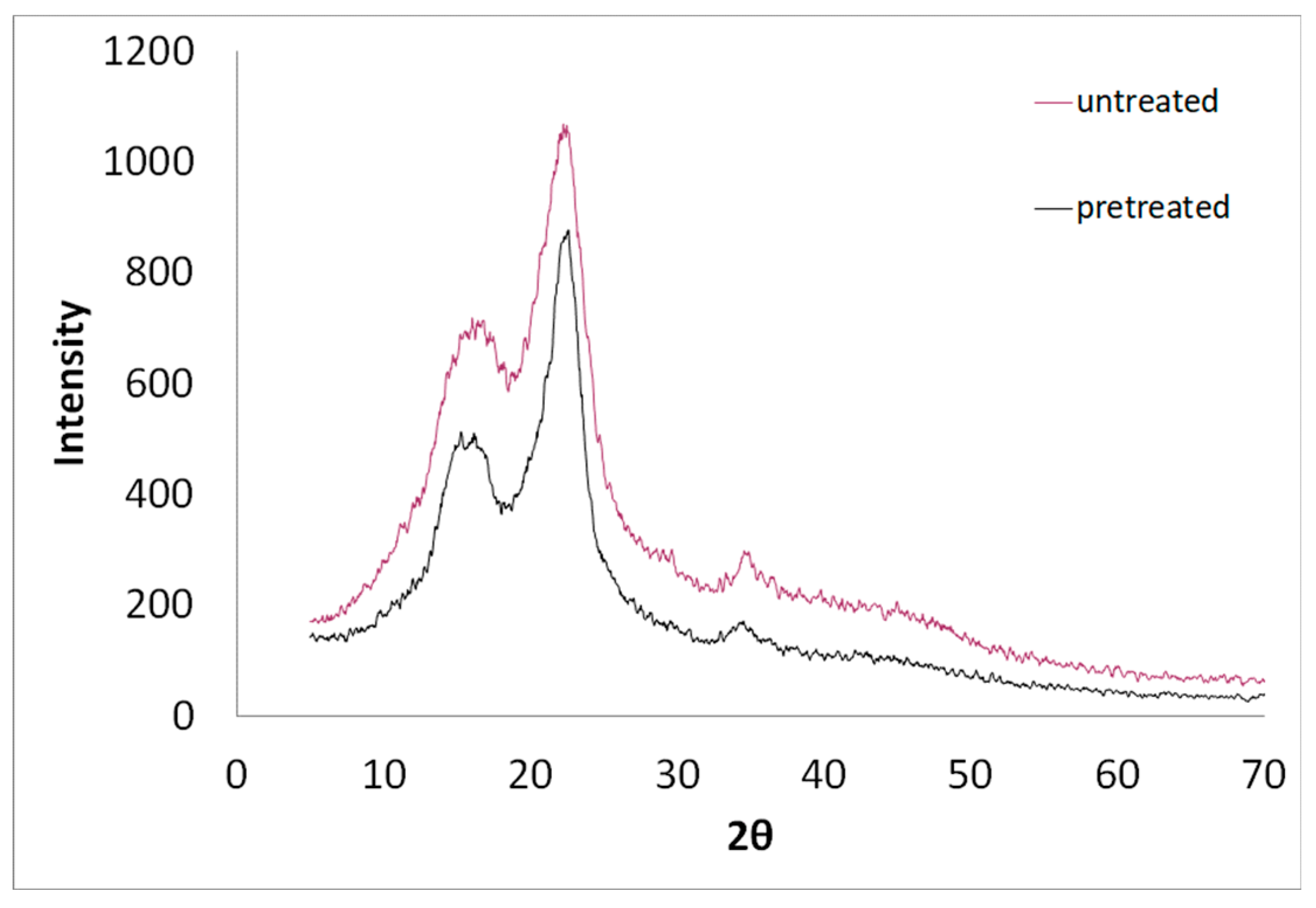

3.4. SEM, FTIR and XRD of Untreated and Modified Spruce Sawdust

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roa, K.; Oyarce, E.; Boulett, A.; ALSamman, M.; Oyarzún, D.; Del, G.; Pizarro, C.; Sánchez, J. Lignocellulose-based materials and their application in the removal of dyes from water: A review. Sustain Mater Techno 2021, 29, e00320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, H.; Ahmadi, S.; Ghosh, S.; Othmani, A.; Osagie, C.; Meskini, M.; AlKafaas, S.S.; Malloum, A.; Khanday, W.A.; Oluwaseun Jacob, A.; Gökkuş, O.; Oroke, A.; Chineme, O.M.; Karri, R.R.; Lima, E.C. Recent advances on sustainable adsorbents for the remediation of noxious pollutants from water and wastewater: A critical review. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Fraceto, L.F.; Fazeli, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Savassa, S.M.; Araujo de Medeiros, G.; Pereira, A.E.S.; Mancini, S.D.; Lipponen, J.; Vilaplana, F. Lignocellulosic biomass from agricultural waste to the circular economy: a review with focus on biofuels, biocomposites and bioplastics. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedula, S.S.; Yadav, G.D. Wastewater treatment containing methylene blue dye as pollutant using adsorption by chitosan lignin membrane: Development of membrane, characterization and kinetics of adsorption. J. India Chem Soc 2021, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, G.; Thakur, A. Distinct approaches of removal of dyes from wastewater: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Bahadur Pal, D.; Mohammad, A.; Alhazmi, A.; Haque, S.; Yoon, T.; Srivastava, N.; Gupta, V.K. Biological remediation technologies for dyes and heavy metals in wastewater treatment: New insight. Bioresour. Technol 2022, 343, 126154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katheresan, V.; Kansedo, J.; Lau, S.Y. Efficiency of various recent wastewater dye removal methods: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4676–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachiyar, C.V.; Rakshi, A.D.; Sandhya, S., Britlin Deva Jebasta, N., Nellore, J. Developments in treatment technologies of dye-containing effluent: A review CSCEE 2023, 7, 100339.

- Mashkoor, F.; Nasar, A. Magsorbents: Potential candidates in wastewater treatment technology – A review on the removal of methylene blue dye. J. Magn. Magn. Mater, 2020, 500, 166408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Gupta, B.; Srivastava, S.K.; Gupta, A.K. Recent advances on the removal of dyes from wastewater using various adsorbents: a critical review. Materials Advances, 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Xu, J.; Bu, X.-H. Recent advances about metal–organic frameworks in the removal of pollutants from wastewater. Coord. -Chem. Rev. 2019, 378, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, A.; Naebe, M.; Wang, X.; Kandasubramanian, B. Biopolymer – A sustainable and efficacious material system for effluent removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozola-Davidane, R.; Burlakovs, J.; Tamm, T.; Zeltkalne, S.; Krauklis, A.E.; Klavins, M. Bentonite-ionic liquid composites for Congo red removal from aqueous solutions. J.Mol.Liq, 2021, 337, 116373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, E.; Ediati, R.; Kusumawati, Y.; Bahruji, H.; Sulistiono, D.O.; Prasetyoko, D. Review on recent advances of carbon based adsorbent for methylene blue removal from waste water. Mater. Today Chem, 2020, 16, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoye, O.; Ajiboye, T.O.; Omotola, E.O.; Oyewola, O.J. Methylene blue dye: Toxicity and potential elimination technology from wastewater. Results in Engineering, 2022, 16, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Yadav, V.K.; Gacem, A.; Ali, I.H.; Dave, D.; Khan, S.H.; Yadav, K.K.; Rather, S.-U. Ahn, Y.; Son, C.T.; Jeon, B.-H. Recent and Emerging Trends in Remediation of Methylene Blue Dye from Wastewater by Using Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Water, 2022, 14, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, M.; Mendoza, J.; Figueroa, K. Adsorption of methylene blue dye using common walnut shell (juglans regia) like biosorbent: implications for wastewater treatment. GCLR 2024, 17, 2362257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fito, J.; Abewaa, M.; Mengistu, A.; Angassa, K.; Ambaye, A.D.; Moyo, W.; Nkambule, T. Adsorption of methylene blue from textile industrial wastewater using activated carbon developed from Rumex abyssinicus plant. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.I.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Aniagor, C.O.; Hosny, M.; Farghali, M.; Rashad, E.; Ejimofor, M.I.; Lopez-Maldanado, E.A.; Ihara, I.; Yap, P.-S.; Rooney, D.W.; Eltaweil., A.S. Methods to prepare biosorbents and magnetic sorbents for water treatment: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2337–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wang, L.; Nan, H.; Cao, Y. Phosphorus adsorption by functionalized biochar: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, A. Beneficiation of saline effluents from seawater desalination plants: Fostering the zero liquid discharge (ZLD) approach - A techno-economic evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkh, B.A.; Al-Amoudi, A.A.; Farooque, M.; Fellows, C.M.; Ihm, S.; Lee, S.; Li, S.; Voutchkov, N. Seawater desalination concentrate—a new frontier for sustainable mining of valuable minerals. npj Clean Water, 2022, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, A.; Giannika, V. Decarbonized and circular brine management/valorization for water & valuable resource recovery via minimal/zero liquid discharge (MLD/ZLD) strategies J. Environ Manage 2022, 324, 116239. [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulos, A.; Haralambous, K.-J.; Loizidou, M. Desalination brine disposal methods and treatment technologies - A review. Sci.Total Environment, 2019, 693, 133545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, A. Brine management (saline water & wastewater effluents): Sustainable utilization and resource recovery strategy through Minimal and Zero Liquid Discharge (MLD & ZLD) desalination systems. Chem. Eng. Process. 2022, 176, 108944. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Absi, R.S.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Brine management strategies, technologies, and recovery using adsorption processes. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021, 22, 101541. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D1141 - 98(2021) Standard Practice for Preparation of Substitute Ocean Water Active Standard ASTM D1141 | Developed by Subcommittee: D19.02 Book of Standards Volume: 11.02S.

- Ferreira, S.L.C.; Bruns, R.E.; Ferreira, H.S.; Matos, G.D.; David, J.M.; Brandão, G.C.; da Silva, E.G.P.; Portugal, L.A.; dos Reis, P.S.; Souza, A.S.; dos Santos, W.N.L. Box- Behnken design: an alternative for the optimization of analytical methods. Anal Chim Acta. 2007, 597, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Santelli, R.E.; Oliveira, E.P.; Villar, L.S.; Escaleira, L.A. Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta, 2008, 76, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. E. P.; Wilson, K. B. On the experimental attainment of optimum conditions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B, 1951, 13, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasch, D.J.; Free, K.W. Prehydrolysis-kraft pulping of Pinus radiata grown in New Zealand. Tappi 1965, 48, 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Overend, R.; Chornet, E. Fractionation of lignocellulosics by steam-aqueous pretreatments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., 1987, 131, 523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Chum, H.H.; Johnson, D.K.; Black, S.K.; Overend, R.P. Pretreatment- catalyst effects and the combined severity parameter. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1990, 13, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, N.; Chornet, E.; Belkacemi, K.; Overend, R.P. Phenomenological kinetics of complex systems: the development of a generalized severity parameter and its application to lignocellulosics fractionation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1992, 47, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, T.A.; Wyman, C.E. Combined sugar yields for dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of corn stover followed by enzymatic hydrolysis of the remaining solids. Bioresour Technol. 2005, 96, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabel, M.A.; Bos, G.; Zeevalking, J.; Voragen, A.G.J.; Schols, H.A. Effect of pretreatment severity on xylan solubility and enzymatic breakdown of the remaining cellulose from wheat straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2034–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiras, D.; Batzias, F.; Ranjan, R.; Tsapatsis, M. Simulation and optimization of batch autohydrolysis of wheat straw to monosaccharides and oligosaccharides. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 10486–10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinwurm, F.; Turk, T.; Denner, J.; Whitmore, K.; Friedl, A. Combined liquid hot water and ethanol organosolv treatment of wheat straw for extraction and reaction modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiras, D.K.; Nazos, A.G.; Giakoumakis, G.E.; Politi, D.V. Simulating the Effect of Torrefaction on the Heating Value of Barley Straw. Energies, 2020, 13, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeman, J.F.; Bubl, J.L.; Harris, E.E. Quantitative saccharification of wood and cellulose. Ind. Eng. Chem. Anal. Ed., 1945, 17, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J Am Chem Soc 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Creely, J.J.; Martin, A.E.; Conrad, C.M. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using X-ray diffractometer. Textile Research Journal, 1959, 29, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; French, A.D.; Condon, B.D.; Concha, M. Segal crystallinity index revisited by the simulation of X-ray diffraction patterns of cotton cellulose Iβ and cellulose II. Carbohydr. Polym., 2016, 135, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freundlich, H.M.F. Über die adsorption in lösungen, Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie.1906, 57, 385-471.

- Langmuir, I. The constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Journal of American Chemical Society, 1916, 38, 2221–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sips, R. Structure of a catalyst surface. Journal of Chemical Physics, 1948, 16, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. Zur theorie der sogenannten adsorption gelöster stoffe. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens, Handlingar 1898, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.S.; Ng, J.C.Y.; McKay, G. Kinetics of pollutants sorption by biosorbents: review. Sep Purif Methods, 2000, 29, 189–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.J.; Morris, J.C. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. J. Sanit. Eng. Div. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1963, 89, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, F.; Koubaa, M.; Kallel, F.; Chaari, F.; Driss, D.; Ghorbel, R.E.; Chaabouni, S.E. Efficiency of almond gum as a low-cost adsorbent for methylene blue dye removal from aqueous solutions. Ind. Crops prod. 2015, 74, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, T.; Rajgopal, S.; Miranda, L.R. Chromium(VI) adsorption from aqueous solution by Hevea Brasilinesis sawdust activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 124, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadarina, A.B.; Al-Muhtasebb, A.H.; Al-laqtaha, N.A.; Walker, G.M.; Allena, S.J.; Ahmada, M.N.M. Biosorption of toxic chromium from aqueous phase by lignin: Mechanism, effect of other metal ions and salts. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 169, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattachatjee, C.; Dutta, S.; Saxena, V.K. A review on biosorptive removal of dyes and heavy metals from wastewater using watermelon rind as biosorbent. Environmental Advances 2020, 2, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, K.O.; Madyira, D.M. Comparative Analysis of the Effects of Five Pretreatment Methods on Morphological and Methane Yield of Groundnut Shells. Waste Biomass Valor 2024, 15, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; Mondal, M.K. Exhaustive characterization on chemical and thermal treatment of sawdust for improved biogas production. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2018, 8, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxenfans, T.; Buchoux, S.; Larcher, D.; Husson, G.; Husson, E.; Sarazin, C. Enzymatic saccharification and structural properties of industrial wood sawdust: Recycled ionic liquids pretreatments, Energy Conversion and Management, 2014, 88, 1094–1103.

- González-Peña, M.M.; Hale, M.D.C. Rapid assessment of physical properties and chemical composition of thermally modified wood by mid-infrared spectroscopy. Wood Sci Technol 2011, 45, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báder, M., Németh, R., Sandak, J. et al. FTIR analysis of chemical changes in wood induced by steaming and longitudinal compression. Cellulose 2020, 27, 6811–6829.

- Javier-Astete, R., Melo, J., Jimenez-Davalos, J. et al. Classification of Amazonian fast-growing tree species and wood chemical determination by FTIR and multivariate analysis (PLS-DA, PLS). Sci Rep 2023, 13, 7827.

- Julia Kruyeniski, Paulo J.T. Ferreira, Maria da Graça Videira Sousa Carvalho, María E. Vallejos, Fernando E. Felissia, María C. Area, Physical and chemical characteristics of pretreated slash pine sawdust influence its enzymatic hydrolysis, Industrial Crops and Products, Volume 130, 2019, Pages 528-536, ISSN 0926-6690.

- Ahamad, Z.; Nasar, A. Design and evaluation of a polyaniline-Azadirachta indica composite for efficient dye removal: insights from experimental and theoretical simulations. Mater Today Sustain, 2024, 100926.

| Experiment | Temperature T (oC) | Time t (min) | Brine concentration (NaCl in g L-1) |

| 1 | 160 | 0 | 98.12 |

| 2 | 240 | 0 | 98.12 |

| 3 | 160 | 50 | 98.12 |

| 4 | 240 | 50 | 98.12 |

| 5 | 200 | 0 | 24.53 |

| 6 | 200 | 0 | 178.71 |

| 7 | 200 | 50 | 24.53 |

| 8 | 200 | 50 | 178.71 |

| 9 | 160 | 25 | 24.53 |

| 10 | 160 | 25 | 178.71 |

| 11 | 240 | 25 | 24.53 |

| 12 | 240 | 25 | 178.71 |

| 13 | 200 | 25 | 98.12 |

| 14 | 200 | 25 | 98.12 |

| 15 | 200 | 25 | 98.12 |

| Experiment | R0 | R0* | logR0* |

| 1 | 198 | 6.12.10-6 | -5.213 |

| 2 | 5.51.104 | 5.39.10-2 | -1.269 |

| 3 | 3.28.103 | 2.12.10-5 | -4.674 |

| 4 | 7.21.105 | 64.3 | 1.808 |

| 5 | 2.97.103 | 1.27.10-4 | -3.897 |

| 6 | 2.46.103 | 7.60.10-6 | -5.119 |

| 7 | 4.62.104 | 0.376 | -0.425 |

| 8 | 4.92.104 | 1.39 | 0.142 |

| 9 | 1.81.103 | 2.03.10-5 | -4.693 |

| 10 | 1.75.103 | 2.83.10-5 | -4.548 |

| 11 | 3.97.105 | 10.7 | 1.029 |

| 12 | 4.02.105 | 92.0 | 1.964 |

| 13 | 2.84.104 | 8.15.10-2 | -1.089 |

| 14 | 2.92.104 | 8.94.10-2 | -1.049 |

| 15 | 2.73.104 | 7.10.10-2 | -1.149 |

| Wavenumber [cm−1] | Assignment | Components | ||

| untreated | pretreated | increase | ||

| 3465 | 3350 | -115 | O-H stretching of bonded hydroxyl groups | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose, Lignin |

| 2910 | 2940 | 30 | Aromatic methoxyl groups and in methyl and methylene groups of side chains symmetric C-H stretching in | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose, Lignin |

| 2362 | 2362 | 0 | N-H stretching | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose, Lignin |

| 1734 | 1710 | -24 | Unconjugated xylans C=O stretching | Hemicelluloses |

| 1699 | 1700 | 1 | R-OH aliphatic carboxyl groups | Lignin |

| 1654 | 1651 | -3 | Aromatic skeletal vibration, C=O stretching in lignin, H-O-H deformation vibration of adsorbed water | Hemicelluloses, Lignin |

| 1617 | 1616 | -1 | C=C stretching of phenol group | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose, Lignin |

| 1576 | 1576 | 0 | Aromatic skeletal vibration, C=O stretching, | Lignin |

| 1507 | 1506 | -1 | C=C stretching of the aromatic ring and aromatical skeletal vibration in Lignin | Lignin |

| 1435 | 1457 | 22 | C-H deformation in methyl and methylene | Lignin |

| 1374 | 1375 | 1 | C-H bending, C-H stretching in methylene | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose, Lignin |

| 1335 | 1314 | -21 | CH2 wagging, C5 substituted aromatic units C-O stretching | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose, Lignin |

| 1268 | 1278 | 10 | C-O stretching of guaiacyl unit | Lignin |

| 1180 | 1173 | -7 | C-H aromatic in plane deformation | Lignin |

| 1134 | 1132 | -2 | C-O-C stretching | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose |

| 1042 | 1060 | 16 | C-OH stretching vibration, C-O deformation | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose, Lignin |

| 1031 | 1038 | 7 | C-O stretching, C-H aromatic in plane deformation | Cellulose, Lignin |

| 902 | 867 | -35 | C-O-C stretching | Hemicelluloses, Cellulose |

| 805 | 852 | 47 | C-H aromatic out of plane bending | Lignin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).