Submitted:

02 August 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Techniques for MIS Deformity Surgery

2.1. MIS Lumbar Interbody Fusion

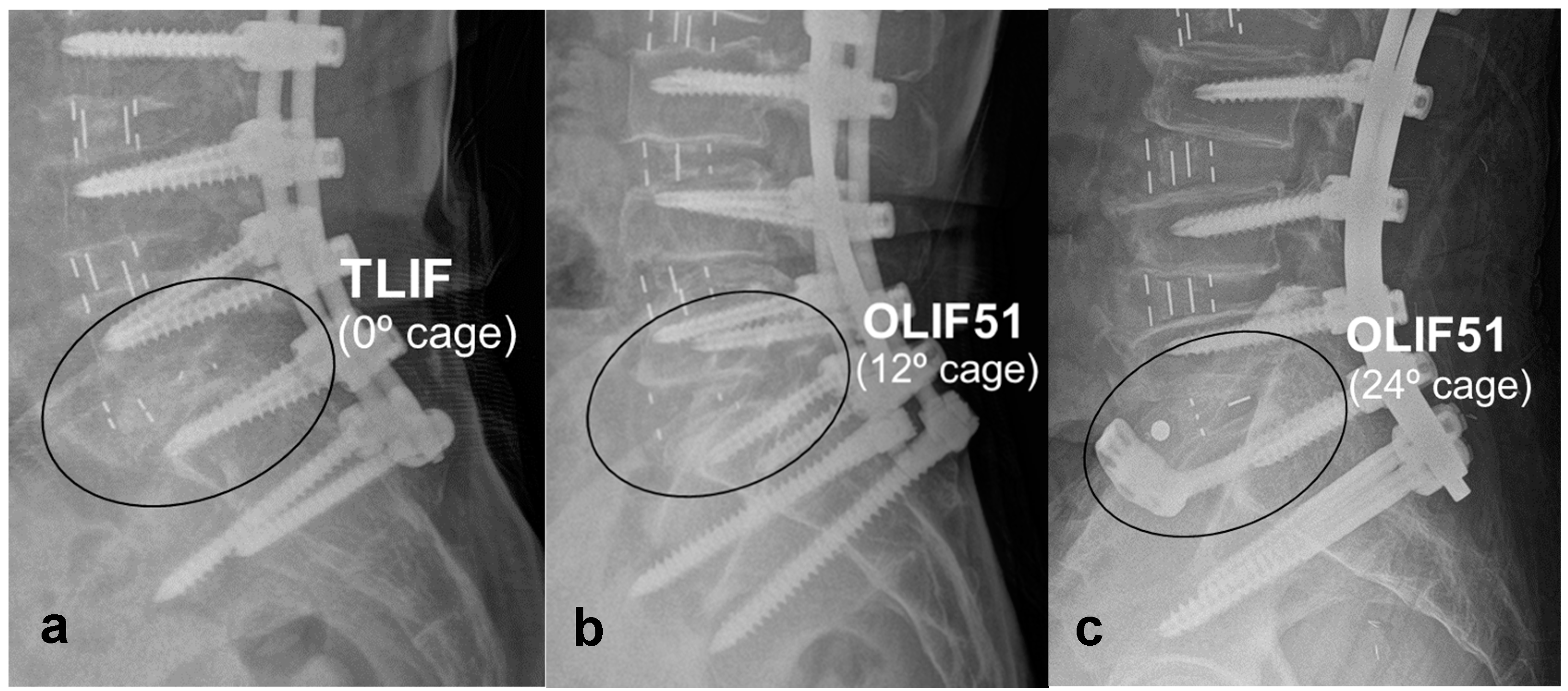

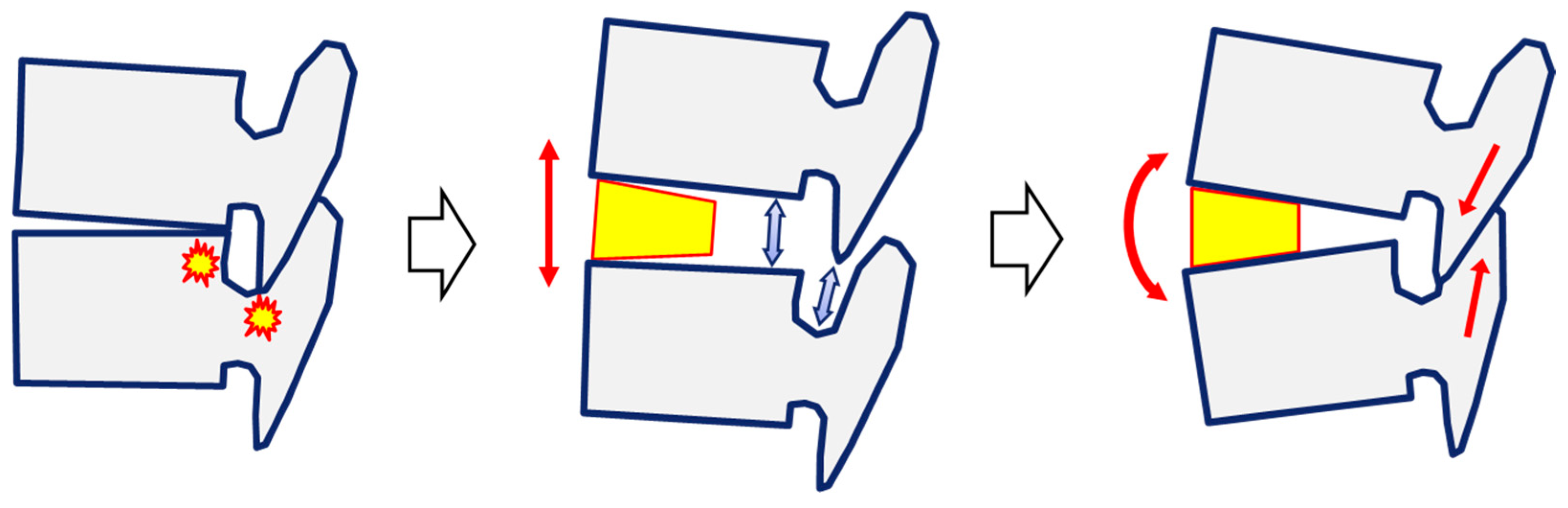

2.2. Effectiveness of LLIF in Sagittal Correction

2.3. Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Fixation

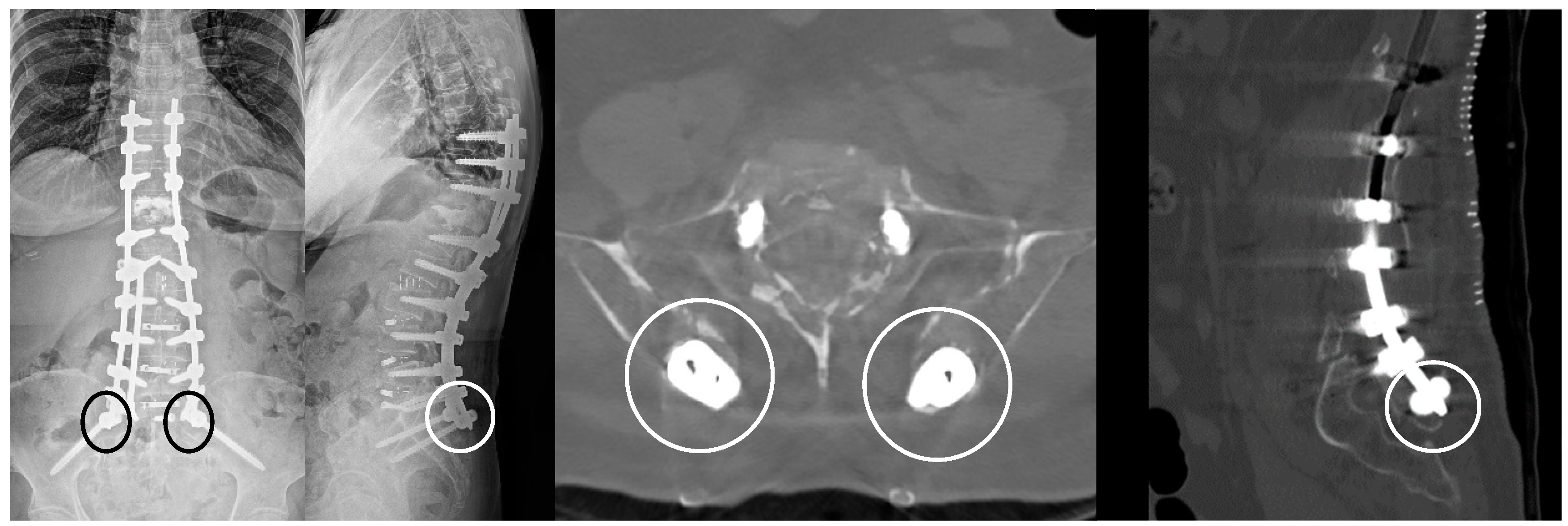

2.4. Avoiding Posterior Corrective Osteotomy

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations of MIS Deformity Surgery

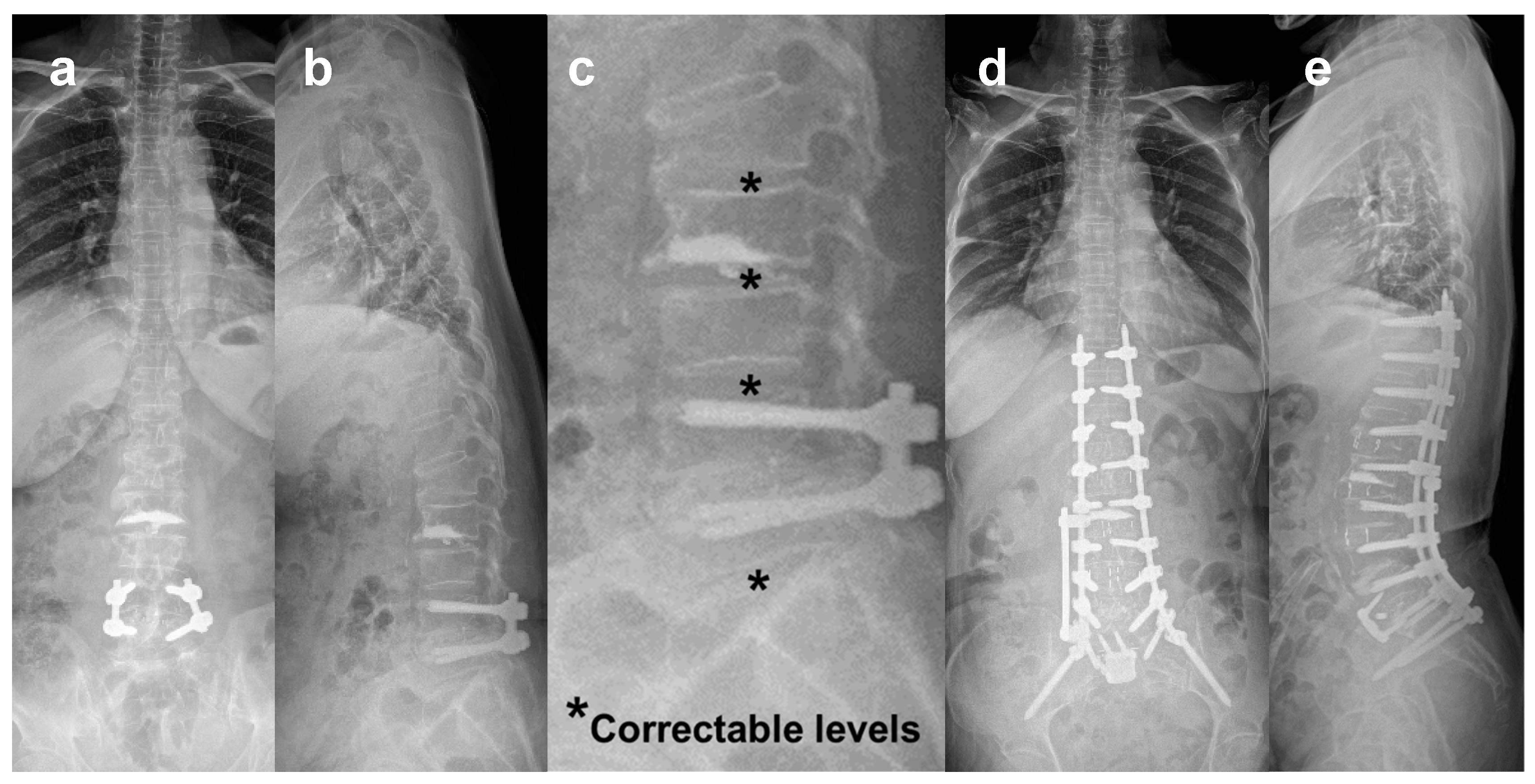

3.2. Correction of Marked Sagittal Deformity

3.3. Concerns of MIS Deformity Surgery

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Obenchain, T.G. Laparoscopic lumbar discectomy: Case report. Journal of Laparoendoscopic Surgery 1991, 1, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momin, A.A.; Steinmetz, M.P. Evolution of minimally invasive lumbar spine surgery. World Neurosurg 2020, 140, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.D.; Canseco, J.A.; Houlihan, N.; Gabay, A.; Grasso, G.; Vaccaro, A.R. Overview of Minimally invasive spine surgery. World Neurosurg 2020, 142, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, N.; Baron, E.M.; Thaiyananthan, G.; Khalsa, K.; Goldstein, T.B. Minimally invasive multilevel percutaneous correction and fusion for adult lumbar degenerative scoliosis: a technique and feasibility study. J Spinal Disord Tech 2008, 21, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundis, G.M.; Akbarnia, B.A.; Phillips, F.M. Adult deformity correction through minimally invasive lateral approach techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010, 35, S312–S321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, R.M.; Mundis, G.M.; Jr Ahmed, Y.; et al. Comparison of radiographic results after minimally invasive, hybrid, and open surgery for adult spinal deformity: a multicenter study of 184 patients. Neurosurg Focus 2014, 36, E13–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mummaneni, P.V.; Shaffrey, C.I.; Lenke, L.G.; et al. The minimally invasive spinal deformity surgery algorithm: a reproducible rational framework for decision making in minimally invasive spinal deformity surgery. Neurosurg Focus 2014, 36, E6–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.P.; Mosley, Y.I.; Uribe, J.S. Role of minimally invasive surgery for adult spinal deformity in preventing complications. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2016, 9, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theologis, A.A.; Mundis, G.M.; Jr Nguyen, S.; et al. Utility of multilevel lateral interbody fusion of the thoracolumbar coronal curve apex in adult deformity surgery in combination with open posterior instrumentation and L5-S1 interbody fusion: a case-matched evaluation of 32 patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2017, 26, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, N.; Kong, C.; Fessler, R.G. A Staged protocol for circumferential minimally invasive surgical correction of adult spinal deformity. Neurosurgery 2017, 81, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, N.; Cohen, J.E.; Cohen, R.B.; Khandehroo, B.; Kahwaty, S.; Baron, E. Comparison of a newer versus older protocol for circumferential minimally invasive surgical (CMIS) correction of adult spinal deformity (ASD)-Evolution over a 10-year experience. Spine Deform 2017, 5, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daubs, M.D.; Lenke, L.G.; Cheh, G.; Stobbs, G.; Bridwell, K.H. Adult spinal deformity surgery: complications and outcomes in patients over age 60. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007, 32, 2238–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.Y. Percutaneous iliac screws for minimally invasive spinal deformity surgery. Minim Invasive Surg 2012, 2012, 173685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pateder, D.B.; Gonzales, R.A.; Kebaish, K.M.; Cohen, D.B.; Chang, J.Y.; Kostuik, J.P. Short-term mortality and its association with independent risk factors in adult spinal deformity surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008, 33, 1224–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.S.; Shaffrey, C.I.; Glassman, S.D.; et al. Risk-benefit assessment of surgery for adult scoliosis: an analysis based on patient age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011, 36, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.Y.; Mummaneni, P.V. Minimally invasive surgery for thoracolumbar spinal deformity: initial clinical experience with clinical and radiographic outcomes. Neurosurg Focus 2010, 28, E9–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheufler, K.M.; Cyron, D.; Dohmen, H.; Eckardt, A. Less invasive surgical correction of adult degenerative scoliosis, part I: technique and radiographic results. Neurosurgery 2010, 67, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, D.S.; Tay, B.K.; Hu, S.S. Adult scoliosis: surgical indications, operative management, complications, and outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999, 24, 2617–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanter, A.S.; Tempel, Z.J.; Ozpinar, A.; Okonkwo, D.O. A Review of Minimally Invasive Procedures for the Treatment of Adult Spinal Deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016, 41 Suppl 8, S59–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, F.L.; Liu, J.; Slimack, N.; Moller, D.; Fessler, R.; Koski, T. Changes in coronal and sagittal plane alignment following minimally invasive direct lateral interbody fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar disease in adults: a radiographic study. J Neurosurg Spine 2011, 15, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyama, A.; Katoh, H.; Sakai, D.; et al. Changes in Spinal Alignment following eXtreme Lateral Interbody Fusion Alone in Patients with Adult Spinal Deformity using Computed Tomography. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12039–12046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heary, R.F.; Kumar, S.; Bono, C.M. Decision making in adult deformity. Neurosurgery 2008, 63, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Mummaneni, P.V.; Fu, K.M.; et al. Less invasive surgery for treating adult spinal deformities: ceiling effects for deformity correction with 3 different techniques. Neurosurg Focus 2014, 36, E12–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakwar, E.; Cardona, R.F.; Smith, D.A.; Uribe, J.S. Early outcomes and safety of the minimally invasive, lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas approach for adult degenerative scoliosis. Neurosurg Focus 2010, 28, E8–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassman, S.D.; Berven, S.; Bridwell, K.; Horton, W.; Dimar, J.R. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.H.; Wong, C.B.; Chen, L.H.; Niu, C.C.; Tsai, T.T.; Chen, W.J. Instrumented posterior lumbar interbody fusion for patients with degenerative lumbar scoliosis. J Spinal Disord Tech 2008, 21, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, D.G.; Revella, J. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus anterior lumbar interbody fusion as an adjunct to posterior instrumented correction of degenerative lumbar scoliosis: three year clinical and radiographic outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009, 34, 2126–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.K.; Kepler, C.K.; Girardi, F.P.; Cammisa, F.P.; Huang, R.C.; Sama, A.A. Lateral lumbar interbody fusion: clinical and radiographic outcomes at 1 year: a preliminary report. J Spinal Disord Tech 2011, 24, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, P.C.; Koski, T.R.; O’Shaughnessy, B.A.; et al. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion in comparison with transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: implications for the restoration of foraminal height, local disc angle, lumbar lordosis, and sagittal balance. J Neurosurg Spine 2007, 7, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwender, J.D.; Holly, L.T.; Rouben, D.P.; Foley, K.T. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005, 18 Suppl, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Jung, T.G.; Lee, S.H. Single-level instrumented mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2008, 9, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Jeon, T.S.; Heo, Y.M.; et al. Radiographic results of single level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in degenerative lumbar spine disease: focusing on changes of segmental lordosis in fusion segment. Clin Orthop Surg 2009, 1, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, R.Q.; Schwaegler, P.; Hanscom, D.; Roh, J. Direct lateral lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative conditions: early complication profile. J Spinal Disord Tech 2009, 22, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgur, B.M.; Aryan, H.E.; Pimenta, L.; Taylor, W.R. Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF): a novel surgical technique for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J 2006, 6, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.T.; Hynes, R.A.; Fung, D.A.; et al. Retroperitoneal oblique corridor to the L2-S1 intervertebral discs in the lateral position: an anatomic study. J Neurosurg Spine 2014, 21, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, K.R.; Billys, J.B.; Hynes, R.A. Technical description of oblique lateral interbody fusion at L1-L5 (OLIF25) and at L5-S1 (OLIF51) and evaluation of complication and fusion rates. Spine J 2017, 17, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.J.; Park, S.W.; Kim, Y.B. Effect of cage in radiological differences between direct and oblique lateral interbody fusion techniques. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2019, 62, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.J.; Park, S.W.; Kim, Y.B. Correction of spondylolisthesis by lateral lumbar interbody fusion compared with transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion at L4-5. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2019, 62, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Park, S.W.; Kim, Y.B. Direct lateral lumbar interbody fusion: clinical and radiological outcomes. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2014, 55, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.D.; Valore, A.; Villaminar, A.; Comisso, M.; Balsano, M. Pelvic parameters of sagittal balance in extreme lateral interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar disc disease. J Clin Neurosci 2013, 20, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Seo, J.Y.; Bae, S.H. Percutaneous posterior instrumentation followed by direct lateral interbody fusion for lumbar infectious spondylitis. J Spinal Disord Tech 2013, 26, E95–E100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepler, C.K.; Huang, R.C.; Sharma, A.K.; et al. Factors influencing segmental lumbar lordosis after lateral transpsoas interbody fusion. Orthop Surg 2012, 4, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, Y.B.; Park, S.W.; Hung, V.T. Clinical and radiological outcomes of a new cage for direct lateral lumbar interbody fusion. Korean J Spine 2014, 11, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, H.Y.; Ko, M.J.; Kim, Y.B.; Park, S.W. Usefulness of oblique lateral interbody fusion at L5-S1 level compared to transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2020, 63, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.J.; Zhang, J.F.; Xu, W.B.; et al. Effect of pure muscle retraction on multifidus injury and atrophy after posterior lumbar spine surgery with 24 weeks observation in a rabbit model. Eur Spine J 2017, 26, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev, G.J.; Lee, Y.P.; Taylor, W.R.; Garfin, S.R.; Kim, C.W. Nerve injury to the posterior rami medial branch during the insertion of pedicle screws: comparison of mini-open versus percutaneous pedicle screw insertion techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009, 34, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimatti, M.; Forcato, S.; Polli, F.; Miscusi, M.; Frati, A.; Raco, A. Pure percutaneous pedicle screw fixation without arthrodesis of 32 thoraco-lumbar fractures: clinical and radiological outcome with 36-month follow-up. Eur Spine J 2013, 22, S925–S932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merom, L.; Raz, N.; Hamud, C.; Weisz, I.; Hanani, A. Minimally invasive burst fracture fixation in the thoracolumbar region. Orthopedics 2009, 32, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.F.; Huang, Y.X.; Chi, Y.L.; et al. Percutaneous pedicle screw fixation for neurologic intact thoracolumbar burst fractures. J Spinal Disord Tech 2010, 23, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korovessis, P.; Repantis, T.; Petsinis, G.; Iliopoulos, P.; Hadjipavlou, A. Direct reduction of thoracolumbar burst fractures by means of balloon kyphoplasty with calcium phosphate and stabilization with pedicle-screw instrumentation and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008, 33, E100–E108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmopoulos, V.; Schizas, C. Pedicle screw placement accuracy: a meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007, 32, E111–E120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

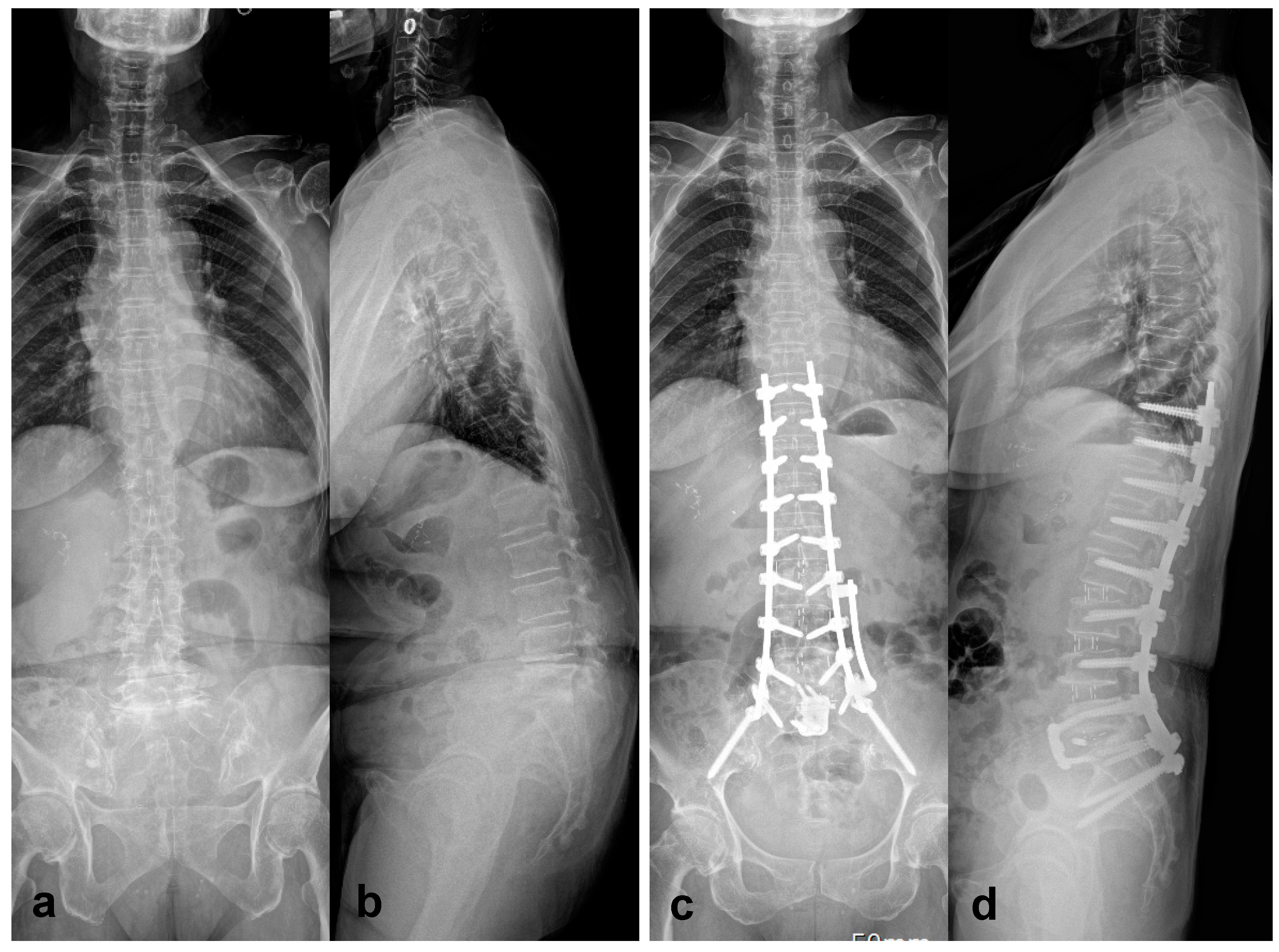

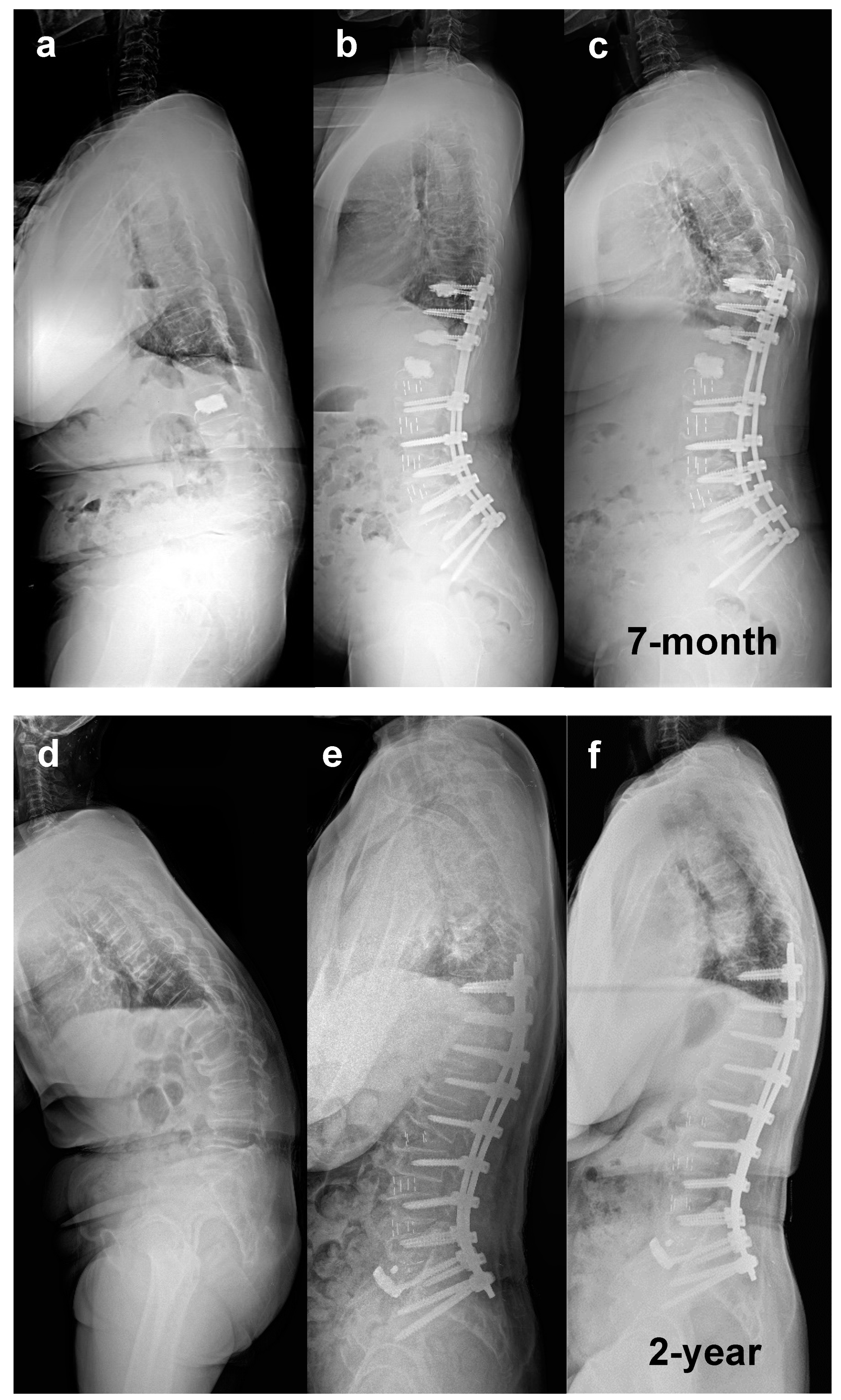

- Park, S.W.; Ko, M.J.; Kim, Y.B.; Le Huec, J.C. Correction of marked sagittal deformity with circumferential minimally invasive surgery using oblique lateral interbody fusion in adult spinal deformity. J Orthop Surg Res 2020, 15, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.Y.; Williams, S.; Mummaneni, P.V.; Sherman, J.D. Minimally invasive percutaneous iliac screws: Initial 24 case experiences with CT confirmation. Clin Spine Surg 2016, 29, E222–E225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Hasan, M.Y.; Wong, H.K. Subcrestal Iliac-Screw: A technical note describing a free hand, in-line, low profile iliac screw insertion technique to avoid side-connector use and reduce implant complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018, 43, E68–E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.J.; Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Berra, A.; Baldus, C. Comparison of Smith-Petersen versus pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the correction of fixed sagittal imbalance. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geck, M.J.; Macagno, A.; Ponte, A.; Shufflebarger, H.L. The Ponte procedure: posterior only treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis using segmental posterior shortening and pedicle screw instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech 2007, 20, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazennec, J.Y.; Neves, N.; Rousseau, M.A.; Boyer, P.; Pascal-Mousselard, H.; Saillant, G. Wedge osteotomy for treating post-traumatic kyphosis at thoracolumbar and lumbar levels. J Spinal Disord Tech 2006, 19, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Loon, P.J.; van Stralen, G.; van Loon, C.J.; van Susante, J.L. A pedicle subtraction osteotomy as an adjunctive tool in the surgical treatment of a rigid thoracolumbar hyperkyphosis; a preliminary report. Spine J 2006, 6, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, C.; Laratta, J.L.; Petridis, P.; Shillingford, J.N.; Lehman, R.A.; Lenke, L.G. Vertebral column resection for rigid spinal deformity. Global Spine J 2017, 7, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enercan, M.; Ozturk, C.; Kahraman, S.; Sarıer, M.; Hamzaoglu, A.; Alanay, A. Osteotomies/spinal column resections in adult deformity. Eur Spine J 2013, 22 Suppl 2, S254–S264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, F.P.; Cordeiro, E.N.; Napoli, M.M. Corrective osteotomy of the spine in ankylosing spondylitis. Experience with 66 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, J.B.; Levin, A.; Burd, T.; Longley, M. Corrective osteotomies in spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008, 90, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchowski, J.M.; Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; et al. Neurologic complications of lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy: a 10-year assessment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007, 32, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.P.; Ondra, S.L.; Chen, L.A.; Jung, H.S.; Koski, T.R.; Salehi, S.A. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of thoracic and lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy for fixed sagittal imbalance. J Neurosurg Spine 2006, 5, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, U.M.; Ahn, N.U.; Buchowski, J.M.; et al. Functional outcome and radiographic correction after spinal osteotomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002, 27, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, S.I.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, S.M.; Chung, E.R.; Nah, K.H. Posterior vertebral column resection for severe spinal deformities. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002, 27, 2374–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, D.D.; Lenke, L.G.; Bridwell, K.H.; Koester, L.A. Risk factors for and assessment of symptomatic pseudarthrosis after lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014, 39, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavadi, N.; Tallarico, R.A.; Lavelle, W.F. Analysis of instrumentation failures after three column osteotomies of the spine. Scoliosis Spinal Disord 2017, 12, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, F.; Ungar, B.; Blondel, B.; et al. Scoliosis Research Society-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: a validation study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012, 37, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrola, K.; Repo, J.; Mecklin, J.P.; Ylinen, J.; Kautiainen, H.; Hakkinen, A. Spinopelvic changes based on the simplified SRS-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: Relationships with disability and health-related quality of life in adult patients with prolonged degenerative spinal disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018, 43, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Lattes, S.; Ries, Z.; Gao, Y.; Weinstein, S.L. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult reconstructive spine surgery results from incomplete restoration of the lumbar lordosis relative to the magnitude of the thoracic kyphosis. Iowa Orthop J 2011, 31, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Cho, S.K.; et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in primary adult deformity surgery: evaluation of 20 degrees as a critical angle. Neurosurgery 2013, 72, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glattes, R.C.; Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Rinella, A.; Edwards, C., 2nd. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity following long instrumented posterior spinal fusion: incidence, outcomes, and risk factor analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruo, K.; Ha, Y.; Inoue, S.; et al. Predictive factors for proximal junctional kyphosis in long fusions to the sacrum in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013, 38, E1469–E1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.S.; Shaffrey, E.; Klineberg, E.; et al. Prospective multicenter assessment of risk factors for rod fracture following surgery for adult spinal deformity. J Neurosurg Spine 2014, 21, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, T.; Kotani, T.; Sakuma, T.; Nemoto, T.; Minami, S. Rod fracture after long construct fusion for spinal deformity: clinical and radiographic risk factors. J Orthop Sci 2013, 18, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafage, R.; Bess, S.; Glassman, S.; et al. Virtual Modeling of Postoperative Alignment after adult spinal deformity surgery helps predict associations between compensatory spinopelvic alignment changes, overcorrection, and proximal junctional kyphosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017, 42, E1119–E1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.K. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis following segmental posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion: minimum 5-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 2045–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Huec, J.C.; Hasegawa, K. Normative values for the spine shape parameters using 3D standing analysis from a database of 268 asymptomatic Caucasian and Japanese subjects. Eur Spine J 2016, 25, 3630–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faundez, A.A.; Richards, J.; Maxy, P.; Price, R.; Leglise, A.; Le Huec, J.C. The mechanism in junctional failure of thoraco-lumbar fusions. Part II: Analysis of a series of PJK after thoraco-lumbar fusion to determine parameters allowing to predict the risk of junctional breakdown. Eur Spine J 2018, 27, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Theologis, A.A.; Strom, R.; et al. Comparative analysis of 3 surgical strategies for adult spinal deformity with mild to moderate sagittal imbalance. J Neurosurg Spine 2018, 28, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janik, T.J.; Harrison, D.D.; Cailliet, R.; Troyanovich, S.J.; Harrison, D.E. Can the sagittal lumbar curvature be closely approximated by an ellipse? J Orthop Res 1998, 16, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussouly, P.; Gollogly, S.; Berthonnaud, E.; Dimnet, J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilgor, C.; Sogunmez, N.; Boissiere, L.; et al. Global Alignment and Proportion (GAP) score: Development and validation of a new method of analyzing spinopelvic alignment to predict mechanical complications after adult spinal deformity surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017, 99, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, J.W.; Patel, A.A. Fixed sagittal plane imbalance. Global Spine J 2014, 4, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannoury, T.; Kempegowda, H.; Haddadi, K.; Tannoury, C. Complications associated with minimally invasive anterior to the psoas (ATP) fusion of the lumbosacral spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019, 44, E1122–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed Rabbo, F.; Wang, Z.; Sunna, T.; et al. Long-term complications of minimally-open anterolateral interbody fusion for L5-S1. Neurochirurgie 2020, 66, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Burch, S.; Mummaneni, P.V.; Mayer, R.R.; Eichler, C.; Chou, D. The effect of obesity on perioperative morbidity in oblique lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine 2020, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, K.; Orita, S.; Mannoji, C.; et al. Perioperative complications in 155 patients who underwent oblique lateral interbody fusion surgery: Perspectives and indications from a retrospective, multicenter survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017, 42, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J. Learning Curve of Minimally invasive surgery oblique lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar diseases. World Neurosurg 2018, 120, e88–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).