Submitted:

31 July 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

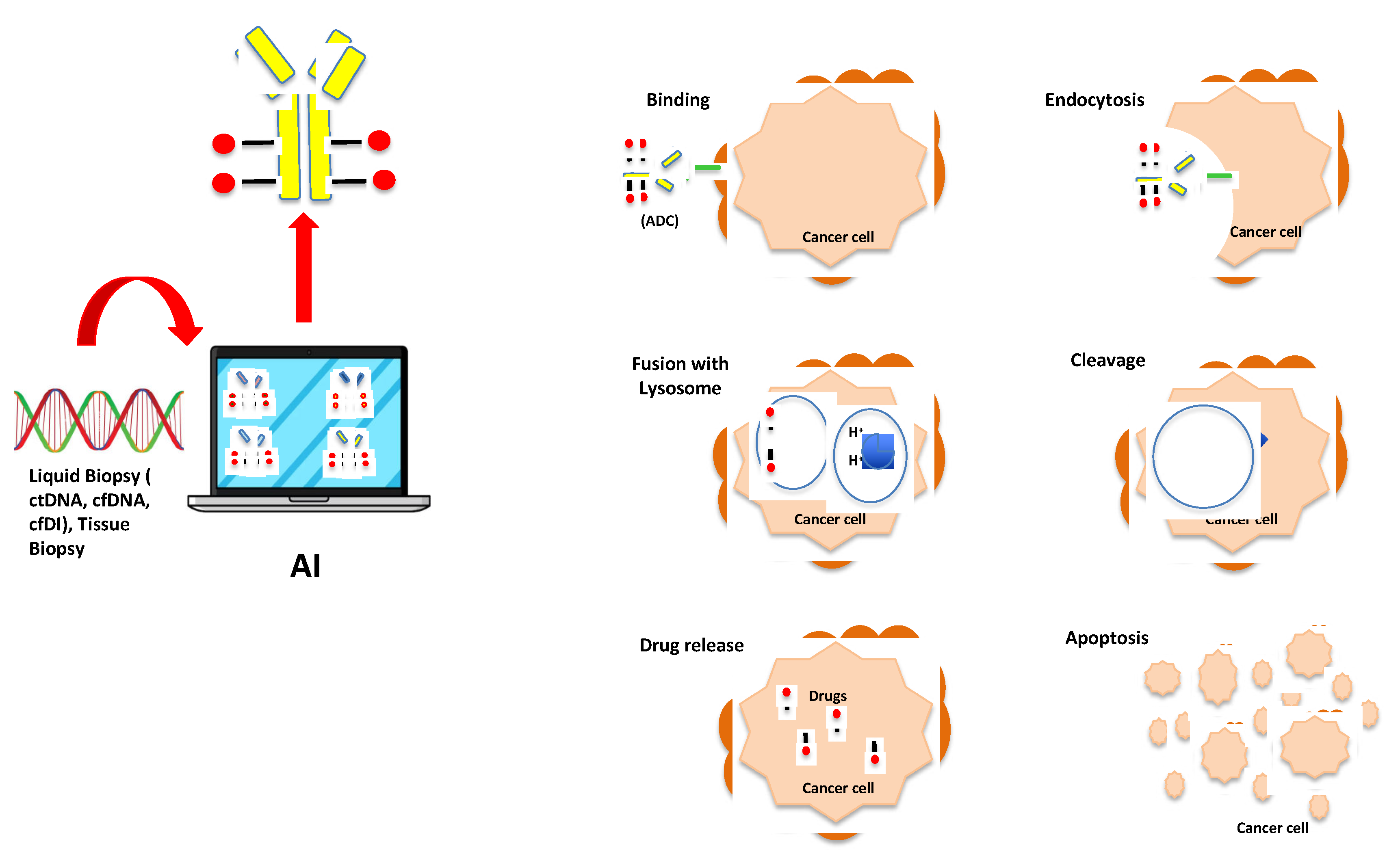

Introduction

Prediction of Cancer Responsiveness and Resistance to ADCs

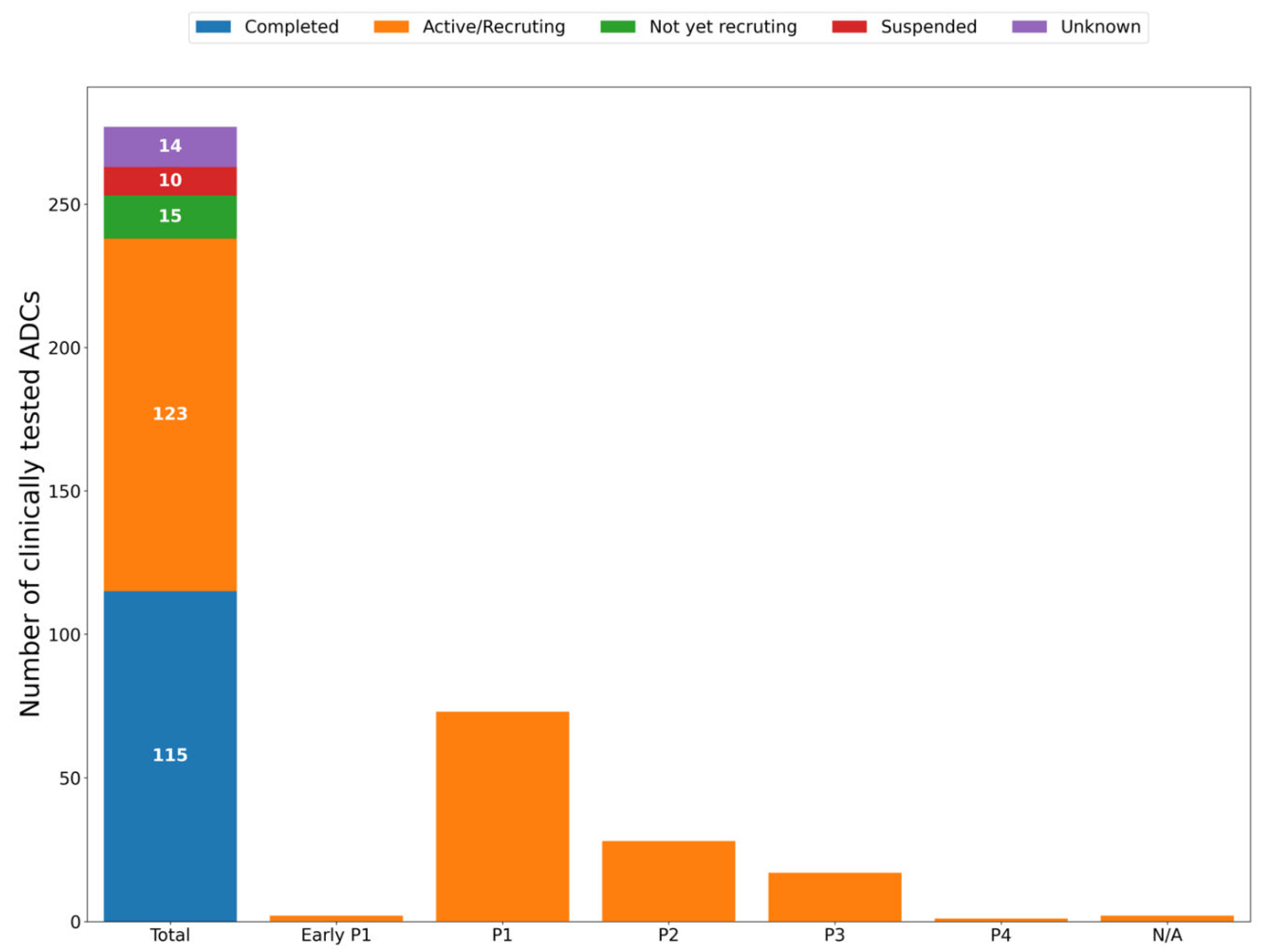

Anticancer ADCs that Have Entered Clinical Trials

Discussion

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Availability of data and material

Competing interests

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Paul, D.; Sanap, G.; Shenoy, S.; Kalyane, D.; Kalia, K.; Tekade, R.K. Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 26, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luc Steels, RB. The Artificial Life Route to Artificial Intelligence (1995).

- Bielecki, A. Models of Neurons and Perceptrons: Selected Problems and Challenges; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AI's potential to accelerate drug discovery needs a reality check. Nature, 622(7982), 217 (2023).

- Schneider, G. Automating drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 17, 97–113 (2018).

- Sobhani, N.; Tardiel-Cyril, D.R.; Chai, D.; Generali, D.; Li, J.-R.; Vazquez-Perez, J.; Lim, J.M.; Morris, R.; Bullock, Z.N.; Davtyan, A.; et al. Artificial intelligence-powered discovery of small molecules inhibiting CTLA-4 in cancer. BJC Rep. 2024, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMasi, J.A.; Grabowski, H.G.; Hansen, R.W. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. J. Health Econ. 2016, 47, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, C.; Brown, S. Antibody–drug conjugates as novel anti-cancer chemotherapeutics. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35, e00225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, N. NEW AND MOST POWERFUL MOLECULES FOR THE TREATMENT AND DIAGNOSIS OF NEUROENDOCRINE CANCERS (NETs) AND THE STEM CELLS OF NETs. In:. Google Patents . (Ed.^(Eds) (Navid Sobhani, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Y.; Yang, M.; Deng, G.; Liu, H. A review of the clinical efficacy of FDA-approved antibody‒drug conjugates in human cancers. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S. Artificial intelligence for drug discovery: Resources, methods, and applications. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2023, 31, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, V.N.; Luna, A.; Yamade, M.; Loman, L.; Varma, S.; Sunshine, M.; Iorio, F.; Sousa, F.G.; Elloumi, F.; Aladjem, M.I.; et al. CellMinerCDB for Integrative Cross-Database Genomics and Pharmacogenomics Analyses of Cancer Cell Lines. iScience 2018, 10, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, K.; Czerwińska, P.; Wiznerowicz, M. Review The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp. Oncol. 2015, 2015, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.G.; Bamford, S.; Jubb, H.C.; Sondka, Z.; Beare, D.M.; Bindal, N.; Boutselakis, H.; Cole, C.G.; Creatore, C.; Dawson, E.; et al. COSMIC: The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D941–D947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.; Domrachev, M.; Lash, A.E. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.; Wilhite, S.E.; Ledoux, P.; Evangelista, C.; Kim, I.F.; Tomashevsky, M.; Marshall, K.A.; Phillippy, K.H.; Sherman, P.M.; Holko, M.; et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets—update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D991–D995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izhar Wallach MD, Abraham Heifets. AtomNet: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Bioactivity Prediction in Structure-based Drug Discovery. arXiv, (2015).

- Sobhani N, Generali D, Zanconati F, Bortul M, Scaggiante B. Cell-free DNA integrity for the monitoring of breast cancer: Future perspectives? World J Clin Oncol, 9(2), 26-32 (2018).

- Conca, V.; Ciracì, P.; Boccaccio, C.; Minelli, A.; Antoniotti, C.; Cremolini, C. Waiting for the “liquid revolution” in the adjuvant treatment of colon cancer patients: A review of ongoing trials. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2024, 126, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobhani, N.; Sirico, M.; Generali, D.; Zanconati, F.; Scaggiante, B. Circulating cell-free nucleic acids as prognostic and therapy predictive tools for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 11, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Cui, P.; Zhu, X.; Lu, H.; Wang, G.; Cai, S.; et al. Circulating cell-free DNA for cancer early detection. Innov. 2022, 3, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.; Laguna, A.; Ikeda, I.; Maxwell, A.W.P.; Chapiro, J.; Nadolski, G.; Jiao, Z.; Bai, H.X. Using Machine Learning to Predict Response to Image-guided Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Radiology 2023, 309, e222891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilo Bzdok NA, Martin Krzywinski Statistics versus machine learning. Nature Methods, 15, 233–234 (2018).

- Morshid, A.; Elsayes, K.M.; Khalaf, A.M.; Elmohr, M.M.; Yu, J.; Kaseb, A.O.; Hassan, M.; Mahvash, A.; Wang, Z.; Hazle, J.D.; et al. A Machine Learning Model to Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma Response to Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2019, 1, e180021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; An, C.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Multi-Task Deep Learning Approach for Simultaneous Objective Response Prediction and Tumor Segmentation in HCC Patients with Transarterial Chemoembolization. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazaheri, Y.; Thakur, S.B.; Bitencourt, A.G.; Gullo, R.L.; Hötker, A.M.; Bates, D.D.B.; Akin, O. Evaluation of cancer outcome assessment using MRI: A review of deep-learning methods. BJR|Open 2022, 4, 20210072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, C.; Wu, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, S.; et al. Real-time automatic prediction of treatment response to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using deep learning based on digital subtraction angiography videos. Cancer Imaging 2022, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma QP, He XL, Li K et al. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Radiomics for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence Prediction After Thermal Ablation. Mol Imaging Biol, 23(4), 572-585 (2021).

- Peng, J.; Lu, F.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Gong, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J. Development and validation of a pyradiomics signature to predict initial treatment response and prognosis during transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 853254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyshchik, A.; Kono, Y.; Dietrich, C.F.; Jang, H.-J.; Kim, T.K.; Piscaglia, F.; Vezeridis, A.; Willmann, J.K.; Wilson, S.R. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the liver: technical and lexicon recommendations from the ACR CEUS LI-RADS working group. Abdom. Imaging 2017, 43, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Software as a Medical Device. 2024.

- Iseke, S.; Zeevi, T.; Kucukkaya, A.S.; Raju, R.; Gross, M.; Haider, S.P.; Petukhova-Greenstein, A.; Kuhn, T.N.; Lin, M.; Nowak, M.; et al. Machine Learning Models for Prediction of Posttreatment Recurrence in Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Pretreatment Clinical and MRI Features: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2023, 220, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puijk, R.S.; Ahmed, M.; Adam, A.; Arai, Y.; Arellano, R.; de Baère, T.; Bale, R.; Bellera, C.; Binkert, C.A.; Brace, C.L.; et al. Consensus Guidelines for the Definition of Time-to-Event End Points in Image-guided Tumor Ablation: Results of the SIO and DATECAN Initiative. Radiology 2021, 301, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Li, Y. Artificial Intelligence Decision-Making Transparency and Employees’ Trust: The Parallel Multiple Mediating Effect of Effectiveness and Discomfort. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang F, Casalino LP, Khullar D. Deep Learning in Medicine-Promise, Progress, and Challenges. JAMA Intern Med, 179(3), 293-294 (2019).

- Calderaro, J.; Seraphin, T.P.; Luedde, T.; Simon, T.G. Artificial intelligence for the prevention and clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 1348–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hippisley-Cox, J.; Coupland, C.; Brindle, P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2017, 357, j2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.C.; Rothwell, P.M.; Nguyen-Huynh, M.N.; Giles, M.F.; Elkins, J.S.; Bernstein, A.L.; Sidney, S. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2007, 369, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.F.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Levy, D.; Belanger, A.M.; Silbershatz, H.; Kannel, W.B. Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease Using Risk Factor Categories. Circulation 1998, 97, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinchoc, M.; Kamath, P.S.; Gordon, F.D.; Peine, C.J.; Rank, J.; ter Borg, P.C. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology 2000, 31, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gorp MJ, Steyerberg EW, Van der Graaf Y. Decision guidelines for prophylactic replacement of Björk-Shiley convexo-concave heart valves: impact on clinical practice. Circulation, 109(17), 2092-2096 (2004).

- Damen, J.A.A.G.; Hooft, L.; Schuit, E.; A Debray, T.P.; Collins, G.S.; Tzoulaki, I.; Lassale, C.M.; Siontis, G.C.M.; Chiocchia, V.; Roberts, C.; et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: systematic review. BMJ 2016, 353, i2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwmeester, W.; Zuithoff, N.P.A.; Mallett, S.; Geerlings, M.I.; Vergouwe, Y.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G.M. Reporting and Methods in Clinical Prediction Research: A Systematic Review. PLOS Med. 2012, 9, e1001221–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; A de Groot, J.; Dutton, S.; Omar, O.; Shanyinde, M.; Tajar, A.; Voysey, M.; Wharton, R.; Yu, L.-M.; Moons, K.G.; et al. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gary S Collins KGMM. Reporting of artificial intelligence prediction models. Lancet, 393(10181), 1577-1579 (2019).

- Gary S Collins JBR, Douglas G Altman & Karel GM Moons Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD Statement. BMC Medicine, 13 (2015).

- Moons, K.G.M.; Altman, D.G.; Reitsma, J.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Macaskill, P.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Vickers, A.J.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Collins, G.S. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, W1–W73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, M. FDA backs clinician-free AI imaging diagnostic tools. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 673–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Dhiman, P.; Navarro, C.L.A.; Ma, J.; Hooft, L.; Reitsma, J.B.; Logullo, P.; Beam, A.L.; Peng, L.; Van Calster, B.; et al. Protocol for development of a reporting guideline (TRIPOD-AI) and risk of bias tool (PROBAST-AI) for diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies based on artificial intelligence. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, A.D.; Fritz, J.M.; Lenardo, M.J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Xie, Z. Artificial intelligence in cancer immunotherapy: Applications in neoantigen recognition, antibody design and immunotherapy response prediction. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 91, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).