Submitted:

31 July 2024

Posted:

01 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ 1: What are the research trends of T-CSTs?

- RQ 2: What are the future T-CSTs’ research opportunities?

2. The Collection of Research Samples

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Overview of Publication

3. The Analysis of Research Construction

3.1. Theoretical Frameworks of T-CSTs Research

3.2. Research Aims

3.3. Design Solutions of T-CSTs

3.4. Prototyping Technologies

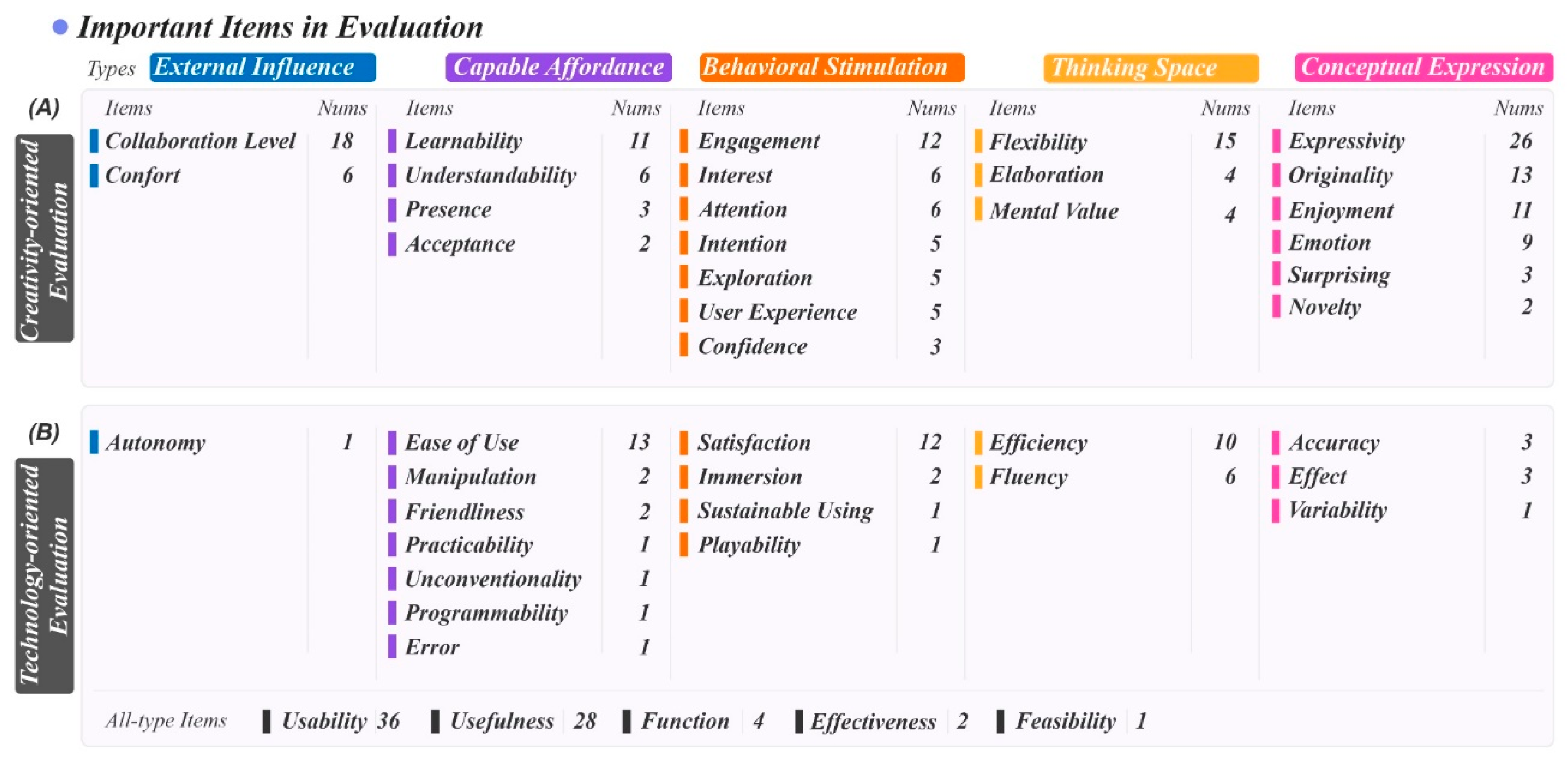

3.5. Evaluation of T-CSTs Solutions

4. Discussion

5. Reflection & Opportunities

5.1. Emphasize the Research on Everyday Creativity Assistance

- Hybrid materiality and interactive forms influence how interactivity is perceived by individuals, making affordance of TUI difficult to measure (Jung et al., 2017). However, using personalized intervention in TUI’s component design can help users to build in-depth and controllable mental models during interaction. For example, by incorporating AI or generative components into hardware, e.g., the detection of users’ creativity preferences, users can customize manipulation components and interaction forms to their cognitive processing, then facilitate long-term adoption of T-CSTs.

- T-CSTs could guide individuals to reflect on their self-directed and expression rather than providing excessive assistance. With reflection design, users can build a deeper understanding of creative space and give insight into the problems in everyday creation (Baumer et al., 2014).

- Evaluating the enhancement of everyday creativity by conducting experiments and workshops might be challenging to define augmented performance. Combining long-term and in-situ research approaches could capture the creators’ variation of augmented indicators and avoid various biases, e.g., the novelty effect (Rutten et al., 2021).

5.2. Utilize the Inclusiveness of the Tangible User Interface for Patients

- The concept of gamification can supply more engaging and satisfying experiences for users by arousing users’ mental flow (Xiao et al., 2022). Based on gamification in component design, T-CSTs encourage patients to engage in physical activities to develop their collaboration, motor skills, and spatial cognition.

- T-CSTs could introduce therapy research through collaboration with professional rehabilitation scholars. Some effective therapies could be explored, such as Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for the elderly and caregivers (Fink, 2010; Pric and Tinker, 2014), meditation (Ding et al., 2014), aerobic exercise (Román et al., 2018) and yoga (Donnegan et al., 2018), alpha/theta neurofeedback for musical learners (Gruzelier, 2014).

5.3. Design Artifacts to Boost Creativity Expression

- Emotional assessment method in our sample tends to be single, relying on qualitative methods, such as self-report (Jang et al., 2019) and observation (Jones et al., 2020) and questionnaire (Peng et al., 2020). Researchers could improve the quality and accuracy of emotion caption with implicit and quantitative approaches (e.g., language, facial expressions, and galvanic skin response).

- It is worthwhile to explore emotional creativity in telematic usage scenarios. Some remote T-CSTs cases were distributed artifacts but did not concentrate on emotional creativity, like online sketching and idea-generation tools for remote meetings (Lee et al., 2017), telematic synchronous system for music learning (Thorn et al., 2021), motion-capture-based VR stage space for immersive dance (Lottridge et al., 2022). Researchers could conduct extensive emotion-related research for emotional scenarios in T-CSTs.

- There was no theoretical consensus regarding the relationship between emotion and creativity, such as viewpoints disputed in the positive and negative states (Lofy, 1998; Charyton et al., 2009), self-regulation from the properties of creative task (Zenasni and Lubart, 2002) and the activation level (De Dreu et al., 2008). Therefore, the individualized emotional mechanism of creativity needs to be further explored to elicit diversified emotional effects.

- Personality-supported cases use AI to amplify human personalities in design. T-CSTs researchers could further expedite the collaboration between humans and AI, allowing users to generate personality efficiently. For example, an AI-based multi-media environment could integrate users’ personalities to build a more rhythmic, aesthetic, and immersive setting for better personalized expression.

5.4. Interact with Biological Data

- First, most current biological mechanisms for creativity used emotion as predictive mediator, other traits did not receive much attention. Researchers could consider multiple factors for augmenting creativity to decrease the bias of bio-based prediction. Take attention as an example, researchers could take it as one of the predictors with others, e.g., emotion, motivation, and choose to correspond biological modal to actualize.

- Second, using a single biological modality to understand the creation process may not be precise enough. Multi-modal design techniques can free user’s mental resources to reduce mental workload (Oviatt, 2006). A well-designed multi-modal system fusing two or more information sources can reduce recognition uncertainty (Oviatt, 2002). Multi-modal data facilitates the development of reliable and accurate recognition model for creativity.

- Researchers should promote the robustness of the devices and consider whether sensing devices might undermine the effects of creative expression. Some creative behaviors involve physical activities, such as dancing, performing, and brainstorming. For robustness, users’ adaptivity, ongoing task, dialogue, environmental context, and input modes collectively generate constraints for the biological status detection.

5.5. Decrease Physical & Cognitive Load for Natural Interaction

5.6. Balance and Standardize the Evaluation Process

6. Limitation

7. Conclusions

Appendix

Screening Samples of Review

| Authors and Times | Entry Point(s) | Augmented Factor(s) | Application | Name of Artifacts | Technological Actualization | Design Purposes | Contribution type | Used Scale & Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Lottridge et al., 2022) | Integration;Expression | Situation;Emotion;Driven Force | Art | BeatSaber (Demo), OhShape, Tilt Brush | VR Applications with Matching handle | Reinforcement of user experience | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (El-Zanfaly et al., 2022) | Integration; | Cooperation; | BusinessInnovation | Sand Playground | Tabletop Systems with a Projection system | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Ali et al., 2022) | Integration;Execution | Cooperation;Mindset;Rhythm | Education | Escape!Bot | Social Robots with GUI Application | Formation of mindset | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Guo et al., 2022) | Availability; | Ability; | BusinessInnovation | VibeRate | Productivity tools | Optimization of threshold and skill | Quantitative study | SUS |

| (Senaratne et al., 2022) | Availability; | Knowledge; | Rehabilitation | TronicBoards | IoT Toolkits | Optimization of threshold and skill | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Blanco et al., 2022) | Integration; | Cooperation; | Education | Nikivision | IoT Toolkits with a Projection system | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Quantitative study | Educational data mining (EDM) |

| (Matthews et al., 2022) | Integration;Execution | Cooperation;Mindset; | Education | Animettes | IoT Toolkits | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Endow et al., 2022) | Availability; | Ability; | Art | Embr LCTD | IoT Toolkits | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Li et al., 2022) | Integration;Availability | Cooperation;Ability;Mindset | Education | stayFOCUSed, Group Hexagon, Tower, Remolight, Glowing Wand | IoT Toolkits | Ideal manifestation | Mixed-Method study | User experience |

| (Lahav et al., 2022) | Availability; | Ability; | Education | Osmo Tangram | IoT Kits with GUI Application | Improvement of intelligence | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Thorn, 2021) | Implementation; | Motivation; | Education | Unnamed | Wearable products with GUI Application | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Urban Davis et al., 2021) | Integration;Expression | Cooperation;Situation;Personality | BusinessInnovation | Calliope 3D modeling | VR Applications | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Alex et al., 2021) | Implementation;Integration | Motivation;Situation; | Rehabilitation | Unnamed | VR Applications | Reinforcement of user experience | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Ali et al., 2021) | Integration; | Cooperation;Situation; | Education | Jibo | Social Robots with GUI Application | Ideal manifestation | Mixed-Method study | TCT-DP |

| (Hubbard et al., 2021) | Execution;Implementation | Mindset;Rhythm;Driven Force | Entertainment | DIY Fluffy Robots | Social Robots with GUI Application | Improvement of cognition and knowledge | Mixed-Method study | Affinity diagramming and thematic analysis |

| (Hu et al., 2021) | Integration; | Cooperation;Situation; | Art | Kuri | Social Robots with a Projection system | Ideal manifestation | Mixed-Method study | Factors of Divergent Thinking |

| (Elgarf et al., 2021) | Integration;Execution | Cooperation;Situation;Rhythm | Entertainment | CUBUS and NAO robot | Social Robots with GUI Application | Formation of mindset | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Ali et al., 2021) | Integration;Execution | Cooperation;Situation;Mindset | Entertainment | Jibo | Social Robots with GUI Application | Formation of mindset | Mixed-Method study | TTCT, TCT-DP |

| (Belakova and Mackay, 2021) | Integration;Implementation | Situation;Driven Force; | Work | SonAmi | Productivity tools with Cup | Ideal manifestation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Somma et al., 2021) | Availability;Execution | Ability;Mindset;Driven Force | Rehabilitation | Unnamed | IoT Toolkits with GUI Application | Improvement of cognition and knowledge | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Chen et al., 2021) | Availability; | Ability;Knowledge; | Education | FritzBot | IoT Toolkits | Optimization of threshold and skill | Quantitative study | USE, NASA-TLX |

| (Hirsch et al., 2021) | Availability;Implementation | Knowledge;Motivation; | Art | Unnamed | IoT Products | Improvement of cognition and knowledge | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Tseng et al., 2021) | Implementation;Availability | Motivation;Ability;Emotion | Entertainment | PlushPal | IoT Kits with GUI Application | Ideal manifestation | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Martelloni et al., 2021) | Availability;Implementation | Ability;Driven Force; | Art | Unnamed | Instruments | Reinforcement of user experience | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Im and Rogers, 2021) | Expression;Implementation | Emotion;Motivation; | Education | Draw2Code | AR Applications with GUI Application | Improvement of cognition and knowledge | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Jones et al., 2020) | Implementation; | Motivation; | BusinessInnovation | Wearable Bits | Wearable products | Optimization of threshold and skill | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Segura et al., 2020) | Implementation;Integration | Motivation;Situation; | Education | VR-OCLS | VR Applications with Matching handle | Promotion of environment and situation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Neate et al., 2020) | Availability; | Knowledge;Ability; | Rehabilitation | CreaTable | Tabletop Systems with GUI Application | Optimization of threshold and skill | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Kim, 2020) | Execution;Implementation | Mindset;Driven Force; | Education | EPL-based robot | Social Robots | Formation of mindset | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Alves-Oliveira et al., 2020) | Execution;Implementation | Mindset;Motivation;Driven Force | Education | YOLO | Social Robots | Formation of mindset | Quantitative study | TCT-DP, CREA |

| (Peng et al., 2020) | Expression;Execution | Emotion;Mindset; | Education | Unnamed | Social Robots | Emotional awakening | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Lin et al., 2020) | Integration;Implementation | Cooperation;Motivation; | BusinessInnovation | Cobbie | Social Robots | Reinforcement of user experience | Mixed-Method study | CSI |

| (Sabuncuoglu, 2020) | Availability;Integration | Ability;Situation; | Rehabilitation | Unnamed | IoT Toolkits | Optimization of threshold and skill | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Cox and Semwal, 2020) | Integration; | Situation; | Art | Line-Storm Ludic System | IoT Toolkits with GUI Application | Promotion of environment and situation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Jessen et al., 2020) | Availability; | Ability; | BusinessInnovation | Unnamed | AR Applications | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | Objective definition |

| (Le Goc et al., 2020) | Integration; | Cooperation; | Entertainment | Zooid | AR Applications with Lego Mindstorms | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Costa et al., 2019) | Integration; | Situation; | Art | Songverse | VR Applications with Matching handle | Reinforcement of user experience | Mixed-Method study | SUS |

| (Rond et al., 2019) | Integration; | Situation; | Art | ImprovBot | Social Robots | Ideal manifestation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Jang et al., 2019) | Implementation; | Motivation;Driven Force; | Work | Monomizo | Productivity tools | Reinforcement of user experience | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Aslan et al., 2019) | Availability;Integration | Ability;Situation; | Work | Unnamed | Productivity tools with GUI Application | Reinforcement of user experience | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Bellucci et al., 2019) | Availability; | Ability; | Life | T4Tags 2.0 | Life and home supple | Ideal manifestation | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Tamashiro et al., 2019) | Implementation; | Motivation; | Education | Unnamed | IoT Toolkits | Ideal manifestation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Chou et al., 2019) | Implementation;Execution | Motivation;Driven Force;Mindset | Education | e-Tuning | IoT Toolkits with GUI Application | Optimization of threshold and skill | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Masril et al., 2019) | Availability;Execution | Ability;Mindset; | Entertainment | Lego Mindstorms | IoT Toolkits | Formation of mindset | Quantitative study | TKF |

| (Cullen and Metatla, 2019) | Availability;Implementation | Ability;Motivation; | Rehabilitation | Unnamed | IoT Kits | Formation of mindset | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Chen et al., 2019) | Expression; | Emotion; | Entertainment | Humming box | IoT Kits | Formation of mindset | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Scheidt and Pulver, 2019) | Availability; | Ability; | Education | Any-Cubes | IoT Kits | Improvement of cognition and knowledge | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Law et al., 2019) | Integration; | Situation; | BusinessInnovation | Nameless HRCD system | Interactive Systems with GUI Application | Management of workspace | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Dube and ince, 2019) | Integration; | Situation; | Art | Nameless device | AR Applications with GUI Application | Reinforcement of user experience | Quantitative study | Think-aloud approach, User Interaction Satisfaction (QUIS), the Computer Usability Satisfaction Questionnaire, NASA Task Load Index (NASA TLX) |

| (Sarkar et al.,2019) | Integration;Execution | Cooperation;Mindset; | Education | Unnamed | AR Applications with GUI Application | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Mixed-Method study | Guilford’s test of divergent thinking |

| (Men and Bryan-Kinns, 2018) | Availability;Integration | Ability;Situation; | Art | LeMo | VR Applications with Matching handle | Management of workspace | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Eteokleous et al., 2018) | Availability;Execution | Knowledge;Mindset; | Education | Multi-prototype | Social Robots | Formation of mindset | Quantitative study | TTCT |

| (Yang et al., 2018) | Integration; | Situation; | BusinessInnovation | Unnamed | VR Applications with Matching handle | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | K-DOCS, EEG |

| (Fujinami et al., 2018) | Execution; | Mindset; | Art | UnicrePaint | Tabletop Systems with GUI Application | Ideal manifestation | Mixed-Method study | CSI |

| (Baur et al., 2018) | Availability; | Ability; | Rehabilitation | ARMin+musical environment | Social Robots with GUI Application | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | IMI |

| (Ehrenberg et al., 2018) | Integration; | Situation; | Work | SENSE-SEAT | Productivity tools | Promotion of environment and situation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Mäkelä and Vellonen, 2018) | Availability; | Ability;Knowledge; | Education | Makey Makey | IoT Toolkits | Optimization of threshold and skill | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Treepong et al., 2018) | Availability; | Ability; | Life | Unnamed | AR Applications with GUI Application | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Vishkaie, 2018) | Implementation; | Motivation; | Education | Unnamed | AR Applications with Wearable product | Reinforcement of user experience | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Nguyen et al., 2017) | Integration; | Situation; | Work | Vremire | VR Applications with GUI Application | Promotion of environment and situation | Qualitative study | SSQ |

| (Kountouras and Zannos, 2017) | Integration;Implementation | Cooperation;Motivation; | Education | GESTUS | Tabletop Systems | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Lee et al., 2017) | Integration; | Cooperation; | Work | All4One | Tabletop Systems with the Projection system | Ideal manifestation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Yamaguchi and Kadone, 2017) | Expression;Availability | Emotion;Ability; | Education | TwinkleBall | IoT Products with GUI Application | Optimization of threshold and skill | Quantitative study | LMA |

| (Seo et al., 2017) | Execution; | Mindset; | Rehabilitation | Unnamed | IoT Kits | Formation of mindset | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Cibrian et al., 2017) | Availability; | Ability; | Rehabilitation | BendableSound | Interactive Systems | Optimization of threshold and skill | Mixed-Method study | SUS |

| (Bouville et al., 2016) | Integration; | Situation; | Art | Unnamed | VR Applications | Promotion of environment and situation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Jackson et al., 2016) | Integration; | Situation; | Art | Lift-Off | VR Applications with Intelligent pen | Ideal manifestation | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Kahn et al., 2016) | Execution;Availability | Mindset;Ability; | Education | ATR’s Robovie | Social Robots with Sand table | Formation of mindset | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Tintarev et al., 2016 | Availability; | Ability;Knowledge; | Education | Unnamed | IoT Toolkits | Optimization of threshold and skill | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Zhi et al., 2015 | Implementation; | Motivation;Driven Force; | Education | Unnamed | Social Robots with Lego Mindstorms | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | EEG |

| (Strawhacker and Bers, 2015) | Integration;Execution | Situation;Mindset; | Education | LEGO WeDo | IoT Toolkits with GUI Application | Promotion of environment and situation | Mixed-Method study | Solve Its |

| (Jou and Wang, 2015) | Execution; | Mindset; | Education | Unnamed | Interactive Systems | Formation of mindset | Quantitative study | CCTST, PAC |

| (Kahn et al., 2014) | Integration;Availability | Situation;Ability; | BusinessInnovation | ATR’s Robovie | Social Robots with GUI Application | Ideal manifestation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Cosentino et al., 2014 | Integration; | Situation; | Art | WB-4 robot system | Social Robots | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Wang et al., 2014) | Execution; | Mindset; | Education | StoryCube | IoT Kits with GUI Application | Formation of mindset | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Branje and Fels, 2014) | Availability; | Ability;Knowledge; | Art | Vibrochord | Instruments | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | Instrument characteristics |

| (Salvador-Herranz et al., 2014) | Integration; | Cooperation; | Work | Unnamed | AR Applications with a Projection system | Formation and implementation of collaboration | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Campos et al., 2014) | Execution; | Mindset; | Work | Second Look | AR Applications | Ideal manifestation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Yamaoka and Kakehi, 2013) | Integration; | Situation; | Work | DePENd | Productivity tools with GUI Application | Promotion of environment and situation | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Nasman and Cutler, 2013) | Availability; | Ability;Knowledge; | BusinessInnovation | Unnamed | Interactive Systems with a Projection system | Optimization of threshold and skill | Mixed-Method study | Subjective definition |

| (Barbosa et al., 2013) | Availability;Implementation | Ability;Driven Force; | Art | Illusio | Instruments | Reinforcement of user experience | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Giannoulis and Sas, 2013) | Expression | Emotion | BusinessInnovation | VibeRate | Wearable | Ideal manifestation | Quantitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Schmitt et al., 2012) | Integration; | Cooperation; | Work | Unnamed | Tabletop Systems with a Projection system | Ideal manifestation | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

| (Liu et al., 2012) | Expression;Availability | Emotion;Ability; | Education | Unnamed | IoT Products with GUI Applications | Optimization of threshold and skill | Quantitative study | LMA |

| (Thieme et al., 2011) | Implementation;Expression | Motivation;Driven Force;Emotion | life | Lovers' box | Life and home supple | Optimization of threshold and skill | Qualitative study | Subjective definition |

References

- Alahakone, A. U., & Senanayake, S. M. N. A. (2009). Vibrotactile feedback systems: Current trends in rehabilitation, sports and information display. 2009 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, 1148–1153. [CrossRef]

- Alex, M., Wünsche, B. C., & Lottridge, D. (2021). Virtual reality art-making for stroke rehabilitation: Field study and technology probe. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 145, 102481. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Devasia, N. E., & Breazeal, C. (2022). Escape!Bot: Social Robots as Creative Problem-Solving Partners. Creativity and Cognition, 275–283. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Devasia, N., Park, H. W., & Breazeal, C. (2021). Social Robots as Creativity Eliciting Agents. In FRONTIERS IN ROBOTICS AND AI (Vol. 8). [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Park, H. W., & Breazeal, C. (2021). A social robot’s influence on children’s figural creativity during gameplay. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 28, 100234. [CrossRef]

- Alladi, S., Meena, A., Kaul, S., & others. (2002). Cognitive rehabilitation in stroke: Therapy and techniques. Neurol India, 50(suppl), S102–S108.

- Allen , V. P., Hanchett Hanson, M., Baer, J., Barbot, B., Clapp, E. P., Corazza, G. E., Hennessey, B., Kaufman, J. C., Lebuda, I., Lubart, T., Montuori, A., Ness, I. J., Plucker, J., Reiter-Palmon, R., Sierra, Z., Simonton, D. K., Neves-Pereira, M. S., & Sternberg, R. J. (2020). Advancing Creativity Theory and Research: A Socio-cultural Manifesto. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(3), 741–745. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. (2018, May 12). THE POWER OF CREATIVITY IN 21ST CENTURY LEARNING. CHAPEL HILL CHUAUNCY HALL. https://blog.chch.org/the-power-of-creativity-in-21st-century-learning.

- Alves-Oliveira, P., Arriaga, P., Cronin, M. A., & Paiva, A. (2020). Creativity Encounters Between Children and Robots. 2020 15th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 379–388.

- Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357–376. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, I., Weitz, K., Schlagowski, R., Flutura, S., Valesco, S. G., Pfeil, M., & André, E. (2019). Creativity Support and Multimodal Pen-Based Interaction. 2019 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 135–144. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J., Calegario, F., Teichrieb, V., Ramalho, G., & Cabral, G. (2013). Illusio: A drawing-based digital music instrument. Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression, 499–502.

- Barnes, J. A. (1969). Graph Theory and Social Networks: A Technical Comment on Connectedness and Connectivity. Sociology, 3(2), 215–232. [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009, March). Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media (Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 361-362). [CrossRef]

- Baumer, E. P. S., Khovanskaya, V., Matthews, M., Reynolds, L., Schwanda Sosik, V., & Gay, G. (2014). Reviewing Reflection: On the Use of Reflection in Interactive System Design. Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Baur, K., Speth, F., Nagle, A., Riener, R., & Klamroth-Marganska, V. (2018). Music meets robotics: A prospective randomized study on motivation during robot aided therapy. In JOURNAL OF NEUROENGINEERING AND REHABILITATION (Vol. 15). [CrossRef]

- Belakova, J., & Mackay, W. E. (2021). SonAmi: A Tangible Creativity Support Tool for Productive Procrastination. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, ACM SIGCHI-. [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A., Vianello, A., Florack, Y., Micallef, L., & Jacucci, G. (2019). Augmenting objects at home through programmable sensor tokens: A design journey. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 122, 211–231. [CrossRef]

- Best, J. R. (2010). Effects of physical activity on children’s executive function: Contributions of experimental research on aerobic exercise. Developmental Review, 30(4), 331–351. [CrossRef]

- Benedek, M., Bruckdorfer, R., & Jauk, E. (2020). Motives for Creativity: Exploring the What and Why of Everyday Creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(3), 610–625. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, B. B., Rodriguez, J. L. T., López, M. T., & Rubio, J. M. (2022). How do preschoolers interact with peers? Characterising child and group behaviour in games with tangible interfaces in school. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 165, 102849. [CrossRef]

- Bonnardel, N., & Zenasni, F. (2010). The Impact of Technology on Creativity in Design: An Enhancement? Creativity and Innovation Management, 19(2), 180–191. [CrossRef]

- Bouville, R., Gouranton, V., & Arnaldi, B. (2016). Virtual reality rehearsals for acting with visuet alffects. Proceedings - Graphics Interface, 0, 125–132.

- Bown, O., & Blevis, E. (2015). Approaches to evaluation in HCI. Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

- Branje, C., & Fels, D. I. (2014). Playing vibrotactile music: A comparison between the Vibrochord and a piano keyboard. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 72(4), 431–439. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, C., & Canina, M. (2019). Creativity 4.0. Empowering creative process for digitally enhanced people. The Design Journal, 22(sup1), 2119–2131. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T. (1960). Blind variation and selective retentions in creative thought as in other knowledge processes. Psychological Review, 67, 380–400. [CrossRef]

- Campos, P., Goncalves, F., Martins, M., Campos, M., & Freitas, P. (2014). Second Look: Combining wearable computing and crowdsourcing to support creative writing. Proceedings of the NordiCHI 2014: The 8th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Fun, Fast, Foundational, 959–962. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, E. A. (2011). Convergence of Self-Report and Physiological Responses for Evaluating Creativity Support Tools. Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Creativity and Cognition, 455–456. [CrossRef]

- Charyton, C., Hutchison, S., Snow, L., Rahman, M. A., & Elliott, J. O. (2009). Creativity as an Attribute of Positive Psychology: The Impact of Positive and Negative Affect on the Creative Personality. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 4(1), 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Tang, Y., Xie, T., & Druga, S. (2019). The humming box: AI-powered Tangible Music Toy for Children. CHI PLAY 2019 - Extended Abstracts of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., Xu, L., & Zhu, K. (2021). FritzBot: A data-driven conversational agent for physical-computing system design. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 155, 102699. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. K., Der, C. S., Sidhu, M. S., & Omar, R. (2011). GUI vs. TUI: engagement for children with no prior computing experience. Electronic Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology, 3(1).

- Cho, I.-Y. (2015, October 31). Technology Requirements for Wearable User Interface. Journal of the Ergonomics Society of Korea. The Ergonomics Society of Korea. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-H., Su, Y.-S., & Chen, H.-J. (2019). Interactive teaching AIDS integrating building blocks and programming logic. Journal of Internet Technology, 20(6), 1709–1720.

- Cibrian, F. L., Peña, O., Ortega, D., & Tentori, M. (2017). BendableSound: An elastic multisensory surface using touch-based interactions to assist children with severe autism during music therapy. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 107, 22–37. [CrossRef]

- Colton, S., Charnley, J., & Pease, A. (2011, December 1). Computational creativity theory: The FACE and IDEA descriptive models.

- Cosentino, S., Petersen, K., Lin, Z., Bartolomeo, L., Sessa, S., Zecca, M., & Takanishi, A. (2014). Natural human-robot musical interaction: Understanding the music conductor gestures by using the WB-4 inertial measurement system. Advanced Robotics, 28(11), 781–792. [CrossRef]

- Costa, W., Ananias, L., Barbosa, I., Barbosa, B., De’ Carli, A., Barioni, R. R., Figueiredo, L., Teichrieb, V., & Filgueira, D. (2019). Songverse: A Music-Loop Authoring Tool Based on Virtual Reality. 2019 21st Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality (SVR), 216–222. [CrossRef]

- Cox, H., & Semwal, S. K. (2020). Line-Storm Ludic System: An Interactive Augmented Stylus and Writing Pad for Creative Soundscape. Computer Science Research Notes, 3001, 63–72. [CrossRef]

- Cropley, A. (2006). In Praise of Convergent Thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 18(3), 391–404. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, K., & Cakir, M. (2016). Evaluating the design and use of tangible user interfaces in educational settings: A review of the literature. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 94, 41-56.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and Creativity. Namta Journal, 22(2), 60-97.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperPerennial, New York, 39.

- Cullen, C., & Metatla, O. (2019). Co-designing Inclusive Multisensory Story Mapping with Children with Mixed Visual Abilities. In PROCEEDINGS OF ACM INTERACTION DESIGN AND CHILDREN (IDC 2019) (pp. 361–373). [CrossRef]

- Davis, N., Winnemöller, H., Dontcheva, M., & Do, E. Y.-L. (2013). Toward a Cognitive Theory of Creativity Support. Proceedings of the 9th ACM Conference on Creativity & Cognition, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C. K. W., Baas, M., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). Hedonic tone and activation level in the mood-creativity link: Toward a dual pathway to creativity model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 739–756. [CrossRef]

- Derda, I. (2022). “Did you know that David Beckham speaks nine languages?”: AI-supported production process for enhanced personalization of audio-visual content. Creative Industries Journal, 0(0), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, C. G. (2013). The neuromodulator of exploration: A unifying theory of the role of dopamine in personality. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Tang, Y.-Y., Tang, R., & Posner, M. I. (2014). Improving creativity performance by short-term meditation. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 10(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Donnegan, K. F., Setti, A., & Allen, A. P. (2018). Exercise and Creativity: Can One Bout of Yoga Improve Convergent and Divergent Thinking? Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 2(2), 193–199. [CrossRef]

- Dube, T. J., & İnce, G. (2019). A novel interface for generating choreography based on augmented reality. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 132, 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Dym, C. L., Agogino, A. M., Eris, O., Frey, D. D., & Leifer, L. J. (2005). Engineering Design Thinking, Teaching and Learning. Journal of Engineering Education, 94(1), 103–120. [CrossRef]

- Dziedziewicz, D., & Karwowski, M. (2018). Development of children's creative visual imagination: A theoretical model and enhancement programmes. In Creativity and Creative Pedagogies in the Early and Primary Years (pp. 23-33). Routledge.

- Ehrenberg, N., Silva, J. L., & Campos, P. (2018). SENSE-SEAT: Challenging Disruptions in Shared Workspaces Through a Sensor-Based Seat. In PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWELFTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON TANGIBLE, EMBEDDED and EMBODIED INTERACTION (TEI’18) (pp. 260–265). [CrossRef]

- Elgarf, M., Skantze, G., & Peters, C. (2021). Once upon a Story: Can a Creative Storyteller Robot Stimulate Creativity in Children? Proceedings of the 21st ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, IVA 2021, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- EL-Zanfaly, D., Huang, Y., & Dong, Y. (2022). Sand Playground: Designing Human-AI Physical Interface for Co-Creation in Motion. Creativity and Cognition, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Endow, S., Rakib, M. A. N., Srivastava, A., Rastegarpouyani, S., & Torres, C. (2022). Embr: A Creative Framework for Hand Embroidered Liquid Crystal Textile Displays. Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. [CrossRef]

- Eteokleous, N., Nisiforou, E., & Christodoulou, C. (2020). Creativity Thinking Skills Promoted Through Educational Robotics. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 946 AISC, 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Falcao, C., Lemos, A. C., & Soares, M. (2015). Evaluation of Natural User Interface: A Usability Study Based on the Leap Motion Device. Procedia Manufacturing, 3, 5490–5495. [CrossRef]

- Fink, A., Grabner, R. H., Benedek, M., Reishofer, G., Hauswirth, V., Fally, M., Neuper, C., Ebner, F., & Neubauer, A. C. (2009). The creative brain: Investigation of brain activity during creative problem solving by means of EEG and FMRI. Human Brain Mapping, 30(3), 734–748. [CrossRef]

- Fink, A., Grabner, R. H., Gebauer, D., Reishofer, G., Koschutnig, K., & Ebner, F. (2010). Enhancing creativity by means of cognitive stimulation: Evidence from an fMRI study. NeuroImage, 52(4), 1687–1695. [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, A. W. (2005). Frontotemporal and dopaminergic control of idea generation and creative drive. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 493(1), 147–153. [CrossRef]

- Foglia, L., & Wilson, R. A. (2013). Embodied cognition. WIREs Cognitive Science, 4(3), 319–325. [CrossRef]

- Ford, C. M. (1996). A Theory of Individual Creative Action in Multiple Social Domains. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1112–1142. [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J.P. (Ed.). (2006). Affect in Social Thinking and Behavior (1st ed.). Psychology Press. [CrossRef]

- Frayling, C. (1993). Research in art and design. Royal College of Art Research Papers, 1, 1–5.

- Frich, J., MacDonald Vermeulen, L., Remy, C., Biskjaer, M. M., & Dalsgaard, P. (2019). Mapping the Landscape of Creativity Support Tools in HCI. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Frich, J., MacDonald Vermeulen, L., Remy, C., Biskjaer, M. M., & Dalsgaard, P. (2019). Mapping the Landscape of Creativity Support Tools in HCI. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Fujinami, K., Kosaka, M., & B., I. (2018). Painting an apple with an apple: A tangible tabletop interface for painting with physical objects. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(4). [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A., Monticolo, D., Camargo, M., & Bourgault, M. (2016). Creativity support systems: A systematic mapping study. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Gemperle, F., Kasabach, C., Stivoric, J., Bauer, M., & Martin, R. (1998). Design for wearability. Digest of Papers. Second International Symposium on Wearable Computers (Cat. No.98EX215), 116–122. [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, S., & Sas, C. (2013). VibeRate, an affective wearable tool for creative design. 2013 Humaine Association Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction, 594–599.

- Glăveanu, V. P. (2013). Rewriting the Language of Creativity: The Five A’s Framework. Review of General Psychology, 17(1), 69–81. [CrossRef]

- Glaveanu, V. P., Hanchett Hanson, M., Baer, J., Barbot, B., Clapp, E. P., Corazza, G. E., Hennessey, B., Kaufman, J. C., Lebuda, I., Lubart, T., Montuori, A., Ness, I. J., Plucker, J., Reiter-Palmon, R., Sierra, Z., Simonton, D. K., Neves-Pereira, M. S., & Sternberg, R. J. (2020). Advancing Creativity Theory and Research: A Socio-cultural Manifesto. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(3), 741–745. [CrossRef]

- Groskop, V. (2021). The democratization of creativity: How the internet is changing the way we make things. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/apr/12/the-democratisation-of-creativity-how-the-internet-is-changing-the-way-we-make-things.

- Gruzelier, J. H., Holmes, P., Hirst, L., Bulpin, K., Rahman, S., Run, C. van, & Leach, J. (2014). Replication of elite music performance enhancement following alpha/theta neurofeedback and application to novice performance and improvisation with SMR benefits. Biological Psychology, 95, 96–107. [CrossRef]

- Gruzelier, J. (2009). A theory of alpha/theta neurofeedback, creative performance enhancement, long distance functional connectivity and psychological integration. Cognitive Processing, 10(1), 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. McGraw-Hill.

- Guo, S., Shi, Y., Xiao, P., Fu, Y., Lin, J., Zeng, W., & Lee, T.-Y. (2022). Creative and Progressive Interior Color Design with Eye-Tracked User Preference. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Posada, J. E., Hayashi, E. C. S., & Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2014). On Feelings of Comfort, Motivation and Joy that GUI and TUI Evoke. In A. Marcus (Ed.), Design, User Experience, and Usability. User Experience Design Practice (pp. 273–284). Springer International Publishing.

- Hirsch, L., Mall, C., & Butz, A. (2021). Do Touch This: Turning a Plaster Bust into a Tangible Interface. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, ACM SIGCHI-. [CrossRef]

- Hollender, N., Hofmann, C., Deneke, M., & Schmitz, B. (2010). Integrating cognitive load theory and concepts of human–computer interaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1278–1288. [CrossRef]

- Horan, R. (2009). The Neuropsychological Connection Between Creativity and Meditation. Creativity Research Journal, 21(2–3), 199–222. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Feng, L., Mutlu, B., & Admoni, H. (2021). Exploring the Role of Social Robot Behaviors in a Creative Activity. Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021, 1380–1389. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F., Fan, J., & Luo, J. (2015). The neural basis of novelty and appropriateness in processing of creative chunk decomposition. NeuroImage, 113, 122–132. [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, L. J., Chen, Y., Colunga, E., Kim, P., & Yeh, T. (2021). Child-Robot Interaction to Integrate Reflective Storytelling Into Creative Play. Creativity and Cognition. [CrossRef]

- Im, H., & Rogers, C. (2021). Draw2Code: Low-Cost Tangible Programming for Creating AR Animations. Proceedings of Interaction Design and Children, IDC 2021, 427–432. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, H. (2008). "Tangible bits". Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on Tangible and embedded interaction - TEI '08. pp. xv. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, H., & Ullmer, B. (1997, March). Tangible bits: towards seamless interfaces between people, bits and atoms. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 234-241).

- Jackson, B., & Keefe, D. F. (2016). Lift-Off: Using Reference Imagery and Freehand Sketching to Create 3D Models in VR. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 22(4), 1442–1451. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S., Kim, S., Noh, B., & Park, Y.-W. (2019). Monomizo: A tangible desktop artifact providing schedules from E-ink screen to paper. DIS 2019 - Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 1123–1130. [CrossRef]

- Jansson, D. G., & Smith, S. M. (1991). Design fixation. Design Studies, 12(1), 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Jauk, E. (2019). A bio-psycho-behavioral model of creativity. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 27, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Jessen, A., Hilken, T., Chylinski, M., Mahr, D., Heller, J., Keeling, D. I., & Ruyter, K. de. (2020). The playground effect: How augmented reality drives creative customer engagement. Journal of Business Research, 116, 85–98. [CrossRef]

- Jones, L., Nabil, S., McLeod, A., & Girouard, A. (2020). Wearable bits: Scaffolding creativity with a prototyping toolkit for wearable e-Textiles. TEI 2020 - Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction, 165–177. [CrossRef]

- Jou, M., & Wang, J. (2015). The use of ubiquitous sensor technology in evaluating student thought process during practical operations for improving student technical and creative skills. In BRITISH JOURNAL OF EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY (Vol. 46, Issue 4, pp. 818–828). [CrossRef]

- Jung, H., Wiltse, H., Wiberg, M., & Stolterman, E. (2017). Metaphors, materialities, and affordances: Hybrid morphologies in the design of interactive artifacts. Design Studies, 53, 24–46. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, P. H., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H., Gill, B. T., Shen, S., Ruckert, J. H., & Gary, H. E. (2016). Human creativity can be facilitated through interacting with a social robot. ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 2016-April, 173–180. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, P. H., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H., Shen, S., Gary, H. E., & Ruckert, J. H. (2014). Creative Collaboration with a Social Robot. Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. U. (2020). A Comparative Study on the Effects of Hands-on Robot and EPL Programming Activities on Creative Problem-Solving Ability in Children. Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Modern Educational Technology, 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Kitchner, K.S. (1983). Cognition, metacognition and epistemic cognition: A three-level model of cognitive processing.Human Development, 26, 222–232. [CrossRef]

- Kongkasuwan, R., Voraakhom, K., Pisolayabutra, P., Maneechai, P., Boonin, J., & Kuptniratsaikul, V. (2016). Creative art therapy to enhance rehabilitation for stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(10), 1016–1023. [CrossRef]

- Kounios, J., & Beeman, M. (2009). The Aha! Moment: The Cognitive Neuroscience of Insight. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 210–216. [CrossRef]

- Kountouras, S., & I., Z. (2017). Gestus: Teaching soundscape composition and performance with a tangible interface. Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression, 336–341.

- Lahav, O. & Ana Wolfson. (2022). Enhancing spatial skills of young children with special needs using the Osmo Tangram based on tangible technology versus a Tangram card game. Virtual Reality. [CrossRef]

- Law, M. V., Jeong, J., Kwatra, A., Jung, M. F., & Hoffman, G. (2019). Negotiating the Creative Space in Human-Robot Collaborative Design. Proceedings of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 645–657. [CrossRef]

- Le Goc, M., Zhao, A., Wang, Y., Dietz, G., Semmens, R., & Follmer, S. (2020). Investigating Active Tangibles and Augmented Reality for Creativity Support in Remote Collaboration. In C. Meinel & L. Leifer (Eds.), Design Thinking Research: Investigating Design Team Performance (pp. 185–200). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Je, S., & Bianchi, A. (2017). All4One: A Moderated Sketching Tool for Supporting Idea-Generation with Remote Users. IASDR 2017, 7th International Conference. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Kothiyal, A., Weber, T., Rossmy, B., Mayer, S., & Hussmann, H. (2022). Designing Tangible as an Orchestration Tool for Collaborative Activities. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 6(5). [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., Guo, J., Chen, Y., Yao, C., & Ying, F. (2020). It Is Your Turn: Collaborative Ideation With a Co-Creative Robot through Sketch. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–14). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C., Liu, K.-P., Wang, P.-H., Chen, G.-D., & Su, M.-C. (2012). Applying tangible story avatars to enhance children’s collaborative storytelling. In BRITISH JOURNAL OF EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY (Vol. 43, Issue 1, pp. 39–51). [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. (2010). Natural user interface- next mainstream product user interface. 2010 IEEE 11th International Conference on Computer-Aided Industrial Design & Conceptual Design 1, 1, 203–205. [CrossRef]

- Lofy, M. M. (1998). The impact of emotion on creativity in organizations. Empowerment in Organizations, 6(1), 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Lottridge, D., Weber, R., McLean, E.-R., Williams, H., Cook, J., & Bai, H. (2022). Exploring the Design Space for Immersive Embodiment in Dance. 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Lubart, T. (2005). How can computers be partners in the creative process: Classification and commentary on the Special Issue. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 63(4), 365–369. [CrossRef]

- Lubart, T.I., & Thornhill-Miller, B. (2019). Creativity: An overview of the 7C’s of creative thought. In R.J. Sternberg & J. Funke (Eds.), The psychology of human thought. Heidelberg, Germany: Heidelberg University Press.

- Luckenbach, T. A. (1986). Managers at Work: Encouraging “Little C” and “Big C” Creativity. Research Management, 29(2), 9–10. [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, S., & Vellonen, V. (2018). Designing for appropriation: A DIY kit as an educator’s tool in special education schools. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 118, 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Malinin, L. H. (2016). Creative Practices Embodied, Embedded, and Enacted in Architectural Settings: Toward an Ecological Model of Creativity. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. [CrossRef]

- Martelloni, A., McPherson, A., & Barthet, M. (2021). Guitar augmentation for Percussive Fingerstyle: Combining self-reflexive practice and user-centred design. Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression. [CrossRef]

- Martindale, C. (1999). Biological bases of creativity. Handbook of creativity, 2, 137-152.

- Masril, M., Hendrik, B., Theozard Fikri, H., Hazidar, A. H., Priambodo, B., Naf’An, E., Handriani, I., Pratama Putra, Z., & Kudr Nseaf, A. (2019). The Effect of Lego Mindstorms as an Innovative Educational Tool to Develop Students’ Creativity Skills for a Creative Society. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1339(1). [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S., Kaiser, K., & Wiles, J. (2022). Animettes: A design-oriented investigation into the properties of tangible toolkits that support children’s collaboration-in-making activities. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 33, 100517. [CrossRef]

- Mayseless, N., Eran, A., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2015). Generating original ideas: The neural underpinning of originality. NeuroImage, 116, 232–239. [CrossRef]

- Mednick, S. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Review, 69(3), 220–232. [CrossRef]

- Men, L., & Bryan-Kinns, N. (2018). LeMo: Supporting Collaborative Music Making in Virtual Reality. 2018 IEEE 4th VR Workshop on Sonic Interactions for Virtual Environments (SIVE), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Merrotsy, P. (2013). A Note on Big-C Creativity and Little-c Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 25(4), 474–476. [CrossRef]

- MIT Media Lab. (2022). Tangible Media Group | Vision. Retrieved November 23, 2022, from https://tangible.media.mit.edu/vision/.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, DG., The PRISMA Group. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Nasman, J., & Cutler, B. (2013b). Evaluation of user interaction with daylighting simulation in a tangible user interface. Automation in Construction, 36, 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Neate, T., Roper, A., Wilson, S., Marshall, J., & Cruice, M. (2020). CreaTable Content and Tangible Interaction in Aphasia. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, ACM SIGCHI-. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C., DiVerdi, S., Hertzmann, A., & Liu, F. (2017). Vremiere: In-headset virtual reality video editing. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, 2017-May, 5428–5438. [CrossRef]

- Norman, D. (2004). Introduction to This Special Section on Beauty, Goodness, and Usability. Human-Computer Interaction, 19, 311–318. [CrossRef]

- Norman, D. A. (2010). Natural User Interfaces Are Not Natural. Interactions, 17(3), 6–10. [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, S. (2002). Breaking the Robustness Barrier: Recent Progress on the Design of Robust Multi-modal Systems (M. V. Zelkowitz, Ed.; Vol. 56, pp. 305–341). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, S. (2006). Human-Centered Design Meets Cognitive Load Theory: Designing Interfaces That Help People Think. Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 871–880. [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, S. (2006). Human-Centered Design Meets Cognitive Load Theory: Designing Interfaces That Help People Think. Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 871–880. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Feng, Y.-L., Wang, N., & Mi, H. (2020). How children interpret robots’ contextual behaviors in live theatre: Gaining insights for multi-robot theatre design. 2020 29th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 327–334. [CrossRef]

- Price, K. A., & Tinker, A. M. (2014). Creativity in later life. Maturitas, 78(4), 281–286. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J. (2009). Interactions of attention, emotion and motivation. In N. Srinivasan (Ed.), Attention (Vol. 176, pp. 293–308). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Remy, C., MacDonald Vermeulen, L., Frich, J., Biskjaer, M. M., & Dalsgaard, P. (2020). Evaluating Creativity Support Tools in HCI Research. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 457–476. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, M. (1961). An Analysis of Creativity. The Phi Delta Kappan, 42(7), 305–310.

- Robinson, J. R. (2008). Webster’s Dictionary definitions of creativity. Online Journal of Workforce Education and Development 3(2). http://wed.siu.edu/Journal/VolIIInum2/Article_1.pdf Accessed 20.06.11 Accessed 20.06.11.

- Román, P. Á. L., Vallejo, A. P., & Aguayo, B. B. (2018a). Acute Aerobic Exercise Enhances Students’ Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 30(3), 310–315. [CrossRef]

- Rond, J., Sanchez, A., Berger, J., & Knight, H. (2019). Improv with Robots: Creativity, Inspiration, Co-Performance. 2019 28th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A. (2014). “Big C, Little c” Creativity as a False Dichotomy: Reality is not Categorical. Creativity Research Journal, 26(1), 131–132. [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161–1178. [CrossRef]

- Rutten, I., Bogaert, L. V. den, & Geerts, D. (2021). From Initial Encounter With Mid-Air Haptic Feedback to Repeated Use: The Role of the Novelty Effect in User Experience. IEEE Transactions on Haptics, 14(3), 591–602. [CrossRef]

- Sabuncuoglu, A. (2020). Tangible music programming blocks for visually impaired children. TEI 2020 - Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction, 423–429. [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Herranz, G., Bañó, M., Contero, M., & Camba, J. (2014). A collaborative design graphical tool based on Interactive Spaces and Natural Interfaces: A case study on an international design project. Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 18th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), 510–515. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P., Sakhardande, P., Oza, U., & Pillai, J. (2019). Study of augmented reality interaction mediums (AIMs) towards collaboratively solving open-ended problems. ICCE 2019 - 27th International Conference on Computers in Education, Proceedings, 1, 472–477.

- Scheidt, A., & Pulver, T. (2019). Any-Cubes: A Children’s Toy for Learning AI: Enhanced Play with Deep Learning and MQTT. Proceedings of Mensch Und Computer 2019, 893–895. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L., Buisine, S., Chaboissier, J., Aoussat, A., & Vernier, F. (2012). Dynamic tabletop interfaces for increasing creativity. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1892–1901. [CrossRef]

- Segura, R. J., del Pino, F. J., Ogayar, C. J., & Rueda, A. J. (2020). VR-OCKS: A virtual reality game for learning the basic concepts of programming. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 28(1), 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, H., Ananthanarayan, S., & Ellis, K. (2022). TronicBoards: An Accessible Electronics Toolkit for People with Intellectual Disabilities. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, ACM SIGCHI-. [CrossRef]

- Sengewald, T., & Roth, A. (2020). User Experience of Creativity Support Tools-A Literature Review in a Management Context. Wirtschaftsinformatik (Zentrale Tracks), 1857–1869.

- Seo, J. H., Aravindan, P., & Sungkajun, A. (2017). Toward Creative Engagement of Soft Haptic Toys with Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGCHI Conference on Creativity and Cognition, 75–79. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L., & Spaulding, S. (2021). Embodied Cognition. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/embodied-cognition/.

- Shneiderman, B. (2009). Creativity Support Tools: A Grand Challenge for HCI Researchers. In M. Redondo, C. Bravo, & M. Ortega (Eds.), Engineering the User Interface: From Research to Practice (pp. 1–9). Springer London. [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B., Fischer, G., Czerwinski, M., Resnick, M., Myers, B., Candy, L., Edmonds, E., Eisenberg, M., Giaccardi, E., Hewett, T., Jennings, P., Kules, B., Nakakoji, K., Nunamaker, J., Pausch, R., Selker, T., Sylvan, E., & Terry, M. (2006). Creativity Support Tools: Report From a U.S. National Science Foundation Sponsored Workshop. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 20(2), 61–77. [CrossRef]

- Somma, F., Di Fuccio, R., Lattanzio, L., & Ferretti, F. (2021). Multisensorial tangible user interface for immersive storytelling: A usability pilot study with a visually impaired child. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2817.

- Statista. (2022). Revenue of short video platforms worldwide from 2019 to 2022. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1168456/revenue-short-video-platforms-worldwide/.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2006). Creating a vision of creativity: The first 25 years. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts, S, 2–12. [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press.

- Sternberg, R. J., & Karami, S. (2021). What Is Wisdom? A Unified 6P Framework. Review of General Psychology, 25(2), 134–151. [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J., & Karami, S. (2022). An 8P Theoretical Framework for Understanding Creativity and Theories of Creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 56(1), 55–78. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R. (2019). Cords and Chords: Exploring the Role of E-Textiles in Computational Audio. Frontiers in ICT, 6. [CrossRef]

- Strawhacker, A., & Bers, M. U. (2015). “I want my robot to look for food”: Comparing Kindergartner’s programming comprehension using tangible, graphic and hybrid user interfaces. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 25(3), 293–319. [CrossRef]

- Tamashiro, M. A., Burd, L., & Roque, R. (2019). Creative Learning Kits for Physical Microworlds: Supporting the Making of Meaningful Projects Using Low-Cost Materials. Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 514–519. [CrossRef]

- Thieme, A., Wallace, J., Thomas, J., Chen, K. L., Krämer, N., & Olivier, P. (2011). Lovers’ box: Designing for reflection within romantic relationships. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69(5), 283–297. [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S. (2021). Telematic Wearable Music: Remote Ensembles and Inclusive Embodied Education. Audio Mostly 2021, 188–195. [CrossRef]

- Tik, M., Sladky, R., Luft, C. D. B., Willinger, D., Hoffmann, A., Banissy, M. J., Bhattacharya, J., & Windischberger, C. (2018). Ultra-high-field fMRI insights on insight: Neural correlates of the Aha!-moment. Human Brain Mapping, 39(8), 3241–3252. [CrossRef]

- Tintarev, N., Reiter, E., Black, R., Waller, A., & Reddington, J. (2016). Personal storytelling: Using Natural Language Generation for children with complex communication needs, in the wild…. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 92–93, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Treepong, B., Mitake, H., & Hasegawa, S. (2018). Makeup Creativity Enhancement with an Augmented Reality Face Makeup System. In COMPUTERS IN ENTERTAINMENT (Vol. 16, Issue 4). [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T., Murai, Y., Freed, N., Gelosi, D., Ta, T. D., & Kawahara, Y. (2021). PlushPal: Storytelling with Interactive Plush Toys and Machine Learning. Proceedings of Interaction Design and Children, IDC 2021, 236–245. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2022, September 17). Cultural Times. The First Global Map of Cultural and Creative Industries. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/creativity/files/culturaltimesthefirstglobalmapofculturalandcreativeindustriespdf.

- Urban Davis, J. anderson, F., Stroetzel, M., Grossman, T., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2021). Designing Co-Creative AI for Virtual Environments. Creativity and Cognition. [CrossRef]

- Vishkaie, R. (2018). The Role of Wearable Technology in Children’s Creativity. In A. Sourin, O. Sourina, C. Rosenberger, & M. Erdt (Eds.), 2018 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CYBERWORLDS (CW) (pp. 443–446). [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., He, L., & Dou, K. (2014). StoryCube: Supporting children’s storytelling with a tangible tool. The Journal of Supercomputing, 70(1), 269–283. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Dai, Y., Li, Q., & Zhu, H. (2022). The Dilemma and Strategies to Realize Smart Manufacturing under the Concept of “Human-machine Collaboration + Short Video Communication” in Greater Bay Area. Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Creative Industry and Knowledge Economy (CIKE 2022), 46–54. [CrossRef]

- Weiser, M., & Brown, J. S. (1996). Designing calm technology. PowerGrid Journal, 1(1), 75-85. http://www.powergrid.com/1.01/calmtech.htm.

- Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a Theory of Organizational Creativity. Academy of Management Review, 18(2), 293–321. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R., Wu, Z., & Hamari, J. (2022). Internet-of-Gamification: A Review of Literature on IoT-enabled Gamification for User Engagement. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 38(12), 1113–1137. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T., & Kadone, H. (2017). Bodily Expression Support for Creative Dance Education by Grasping-Type Musical Interface with Embedded Motion and Grasp Sensors. Sensors, 17(5). [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, J., & Kakehi, Y. (2013). DePENd: Augmented sketching system using ferromagnetism of a ballpoint pen. UIST 2013 - Proceedings of the 26th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 203–210. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Lin, L., Cheng, P.-Y., Yang, X., Ren, Y., & Huang, Y.-M. (2018). Examining creativity through a virtual reality support system. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(5), 1231–1254. [CrossRef]

- Zabelina, D. L. (2018). Attention and creativity. In R. E. Jung & O. Vartanian (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the neuroscience of creativity (pp. 161–179). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Zagalo, N., Branco, P. (2015). The Creative Revolution That Is Changing the World. In: Zagalo, N., Branco, P. (eds) Creativity in the Digital Age. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer, London. [CrossRef]

- Zaidel, D. W. (2014). Creativity, brain, and art: Biological and neurological considerations. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zenasni, F., & Lubart, T. (2002). Effects of mood states on creativity. Current psychology letters, (8), 33-50. [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D., Wu, Z., Li, W., Zhao, J., Mao, X., Li, M., & Ma, M. (2015). Education-oriented portable brain-controlled robot system. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), 1018–1023. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J., & Forlizzi, J. (2014). Research Through Design in HCI. In J. S. Olson & W. A. Kellogg (Eds.), Ways of Knowing in HCI (pp. 167–189). Springer New York. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, O., & Gal-Oz, A. (2013). To TUI or not to TUI: Evaluating performance and preference in tangible vs. Graphical user interfaces. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 71(7), 803–820. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L. (1998). Creativity and Aesthetic Sense. Creativity Research Journal, 11(4), 309–313. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).