1. Introduction

In response to environmental and nutritional stimuli, the central nervous system (CNS) can promote cellular and molecular changes that can affect human health [

1]. For instance, excessive use or prolonged exposure to agricultural pesticides can damage the CNS and result in neurodegeneration [

2,

3]. Rotenone is a widely used pesticide that is associated with systemic toxicity and damage to the CNS [

4,

5,

6] as it induces harmful changes that can cause neuroinflammation and culminate in death cells [

7,

8] however, the use of natural products can be an important way of treating these damages [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Copaifera Reticulata Ducke Oil-Resin (CPOR) is obtained from a plant native to the Amazon rainforest and widely used by native peoples due to its antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activity. Moreover, CPOR has demonstrated potential anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects [

10] throughout the inhibition of mitochondrial dysfunction at several stages of CNS lesions [

9]. However, there is a lack of studies on the evaluation of the effect of CPOR on cells exposed to rotenone. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the cytoprotective effect of CPOR on total cell cultures derived from the ventral midbrain (VMC), hippocampus (HC), and cerebral cortex (CCC) exposed to rotenone at different concentrations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Rotenone, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), L-glutamine, penicillin (10.000 U/mL)/streptomycin (10 mg/mL), poli-l-lysine, dimethylsulfoxide, C2H2OS (Sigma Chemicals Co., St. Louis, USA), trypsin (Amresco Inc., Philadelphia, USA), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) (VitroCell Co., Campinas, Brazil).

2.2. Cell Culture

After approval of the Ethics Committee for Animal Research of the Federal University of Pará (CEPAE-UFPA 216-14), 1- to 3-day-old Wistar rats were decapitated with scissors and placed on 70% ethanol-containing Petri dishes. Sections from the ventral midbrain (VMC), hippocampus (HC), and cerebral cortex (CCC) were dissected in Petri dishes containing ice-cold sterile Hanks’s buffer (160 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 3.3 mM Na2HPO4, 4 mM NaHCO3, 4.4 mM KH2PO4, 5.4 mM C6H12O6) under a laminar flow cabin. After 10 minutes in a 0.05% trypsin solution at 37 °C for enzymatic digestion, the sections were transferred to DMEM culture medium containing 0.2% penicillin/streptomycin + 10% FBS + 2 mM glutamine, and mechanically dissociated by using a Pasteur pipette. Neurons and glial cells were counted by using the trypan blue exclusion method and uniformly seeded at 3x106 cells per well. The cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% O2) until reaching optimal confluence and quantity [

13,

14].

2.3. Rotenone Exposure

VMC, HC, and CCC were exposed to rotenone by following adapted protocols [

15,

16,

17].

2.4. CPOR Exposure

The exposure to CPOR followed adapted protocols for VMC, as well as for HC and CCC [

10,

12].

2.5. Rotenone + CPOR Exposure

The simultaneous exposure to rotenone and CPOR followed adapted protocols for VMC, HC, and CCC [

9,

12].

2.6. Cell Viability

The cell cultures were exposed to yellow 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) and incubated at 36.5 °C for 3 hours. Then, the blue formazan product of cell lysis was measured at 570 nm by using a 96-well plate colorimetric reader [

18,

19]. The viability of untreated cells (control) was set as 100%, while the cell viability after exposure to rotenone and/or CPOR was expressed as percentages of their respective controls.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Cell viability data were presented as percentage means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and groups were compared by using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey multiple comparisons at a significance level of 5% (GraphPad Prism version 8.0, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

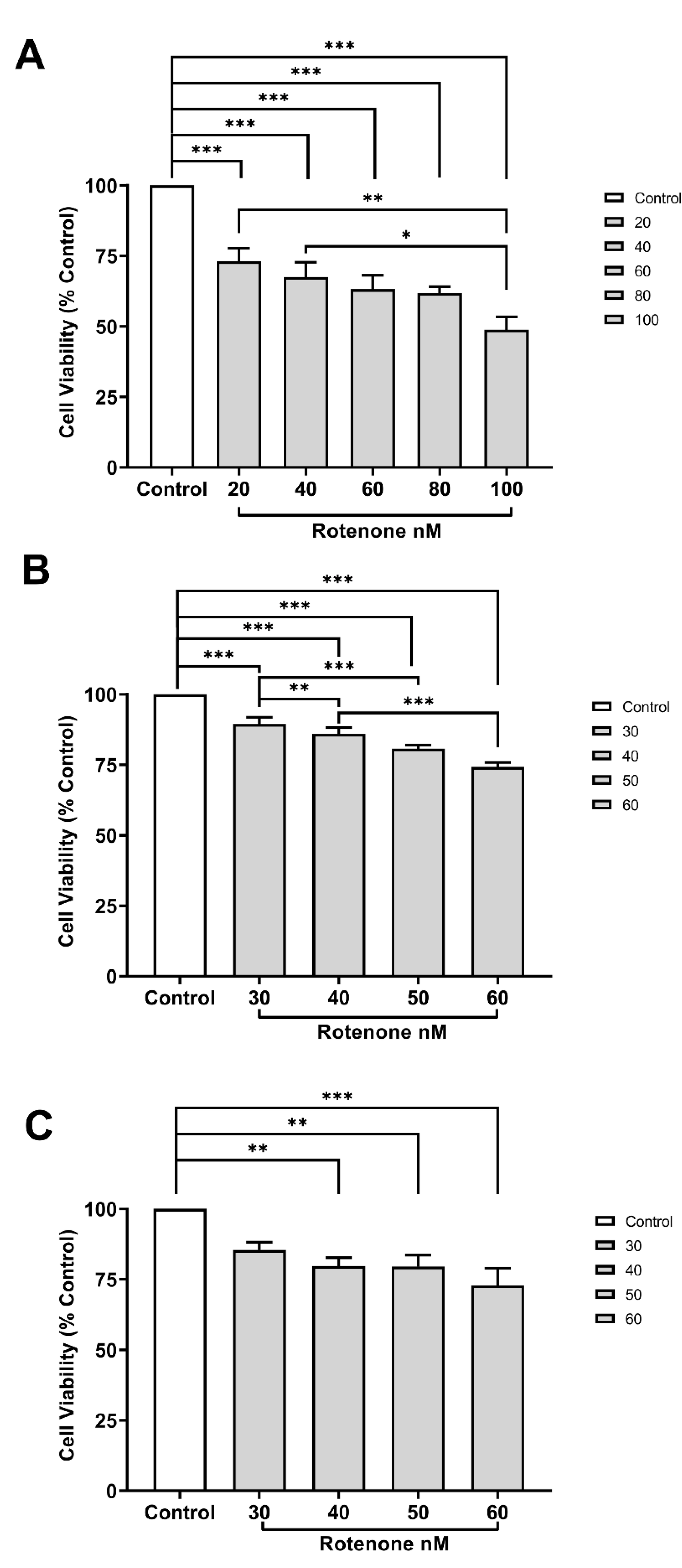

3.1. Cell Viability after Rotenone Exposure

In comparison to the control group, exposure to rotenone at concentrations from above 20 ηM, 30 ηM, and 40 ηM significantly reduced the cell viability of VMC, HC, and CCC, respectively (

Figure 1A–C).

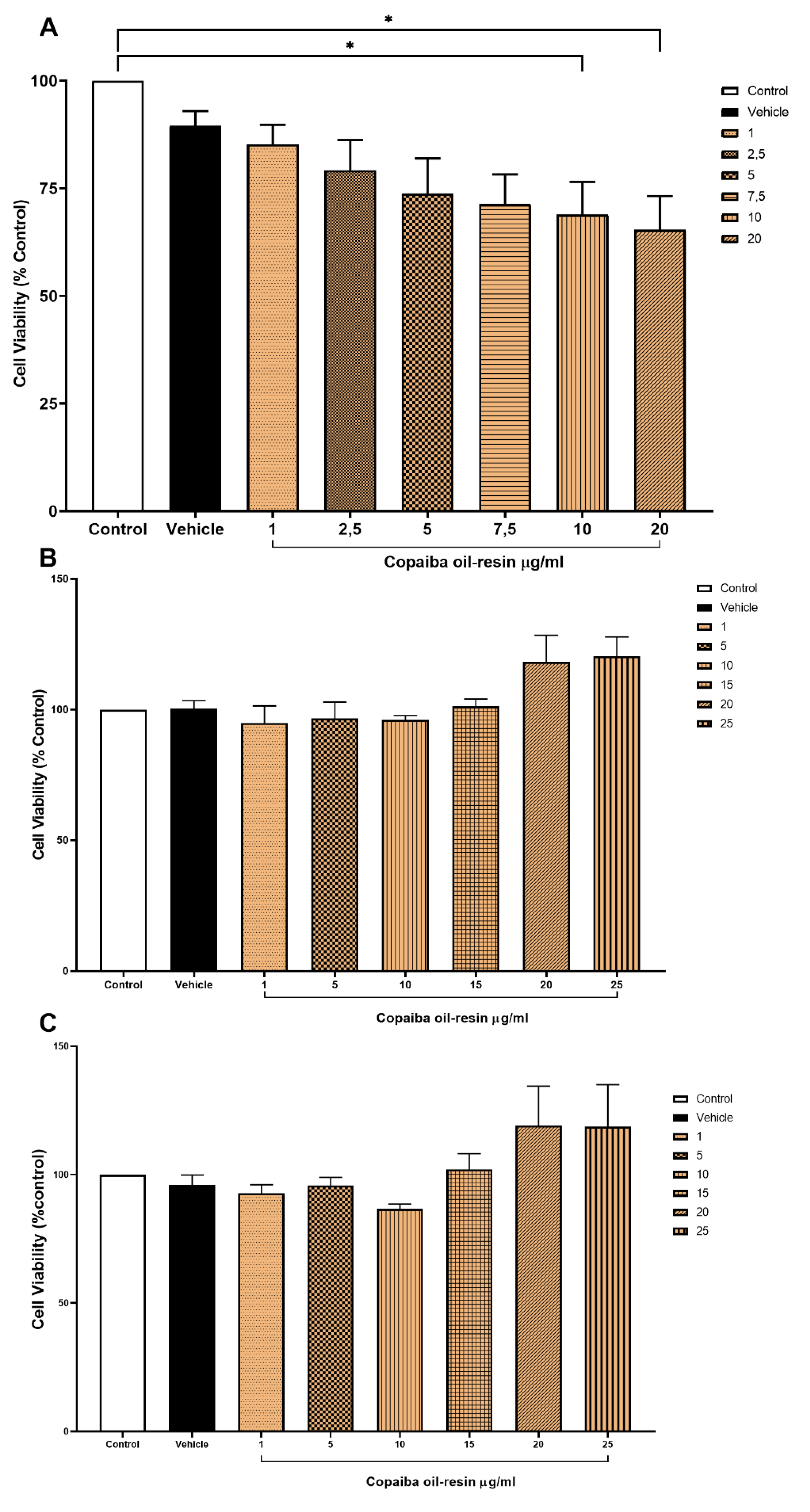

3.2. Cell Viability after CPOR Exposure

In comparison to the control group, exposure to CPOR at 10 and 20 µg/ml significantly reduced the cell viability of VMC (

Figure 2A). Conversely, there was no significant alteration in the cell viability of both HC (

Figure 2B) and CCC (

Figure 2C) exposed up to 25 µg/ml CPOR.

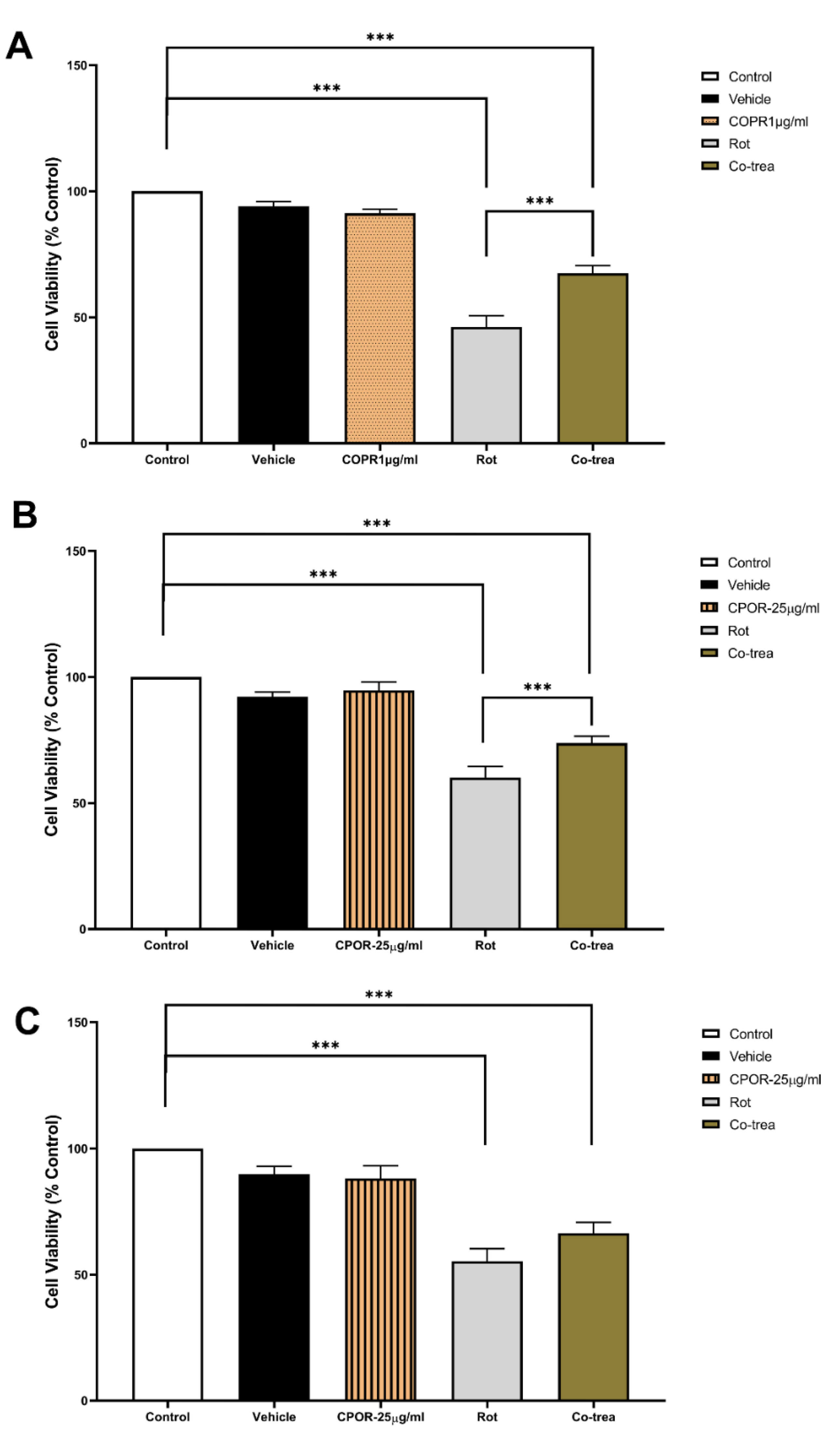

3.3. Cell Viability after Simultaneous Exposure to Rotenone and CPOR

Although significantly lower than the control group, cell viability of VMC simultaneously exposed to 60 ηM rotenone and 1 µg/ml CPOR was significantly higher when compared to VMC exposed only to 60ηM rotenone (

Figure 3A). The same neuroprotective effect on cell viability was observed when HC was simultaneously exposed to 60 ηM rotenone and 25 µg/ml CPOR (

Figure 3B). However, there was no significant difference in the cell viability of CCC only exposed to 60 ηM rotenone and those simultaneously exposed to 25 µg/ml CPOR (

Figure 3C).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicated that exposure to rotenone pesticides reduces the viability of the three cell cultures evaluated. While the exposure to at least 10 µg/ml CPOR decreased the VMC cell viability, the exposure to at least 25 µg/ml CPOR did not change the cell viability of HC and CCC. The simultaneous exposure of cell cultures to both rotenone and CPOR resulted in a neuroprotective effect since cell viability was preserved for VMC (exposed to 1 µg/ml CPOR) and HC (exposed to 25 µg/ml CPOR); however, this effect was not observed for CCC since the cell viability was not different from CCC only exposed to rotenone.

Rotenone is a natural compound found in plants such as timbó and castor beans and is used as an insecticide/pesticide on crops [

20,

21]. Rotenone has toxic effects on the CNS due to its interaction with specific receptors of nerve cells [

22,

23,

24], such as dopamine D2 and NMDA glutamate [

21,

22,

25,

26]. For instance, rotenone binding to dopamine D2 receptors reduces the dopaminergic activity, which consequently increases dopamine concentration in the synaptic cleft; thus, dopamine reuptake by other monoamine receptors is increased, as well as the amount of dopamine inside cells [

22,

25,

26]. The degradation of dopamine by monoamine oxidase (MAO) releases free radicals and the excess of ROS damages neural cells [

21,

22,

25,

26]. Similarly, the interaction of rotenone to NMDA glutamate receptors increases the excitatory cell activity due to the prolonged opening of NMDA channels, which increases the amount of free radicals due to excitotoxicity activity [

22,

25,

26].

Furthermore, rotenone inhibits the activity of both mitochondrial complex I (NADH) [

27,

28] and III (ubiquinone-cytochrome C oxidoreductase), which consequently compromises energy production, increases ROS production, and causes oxidative stress. These events may explain the cell viability reduction observed in this study [

8,

22,

23,

24,

26]. Although cell viability was reduced for cell cultures derived from different brain regions (midbrain, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex), their responses varied in function of different rotenone concentrations. The fact that VMC was more affected by rotenone than HC and CCC (

Figure 1) may be explained by a higher density of receptors and mitochondria in VMC [

21,

23,

29], which increases the chance of mitochondrial damage, activates metabolic pathways that decrease ATP supply, increases ROS production in nervous tissue, and leads to cell death and neurodegeneration [

6,

23,

27].

It has been reported that CNS lesions can be mitigated by using bioactive compounds or natural products extracted from plants such as copaiba oil-resin [

9,

10,

30], which is in line with the neuroprotective effect of CPOR observed in this study. Previous research reported that the effects of copaiba oil-resin on cell viability of WI-26VA and RAW 264.7 lines [

10,

31,

32] are concentration-dependent, which is in line with the results of this study since the cell viability of VMC was only significantly reduced when exposed to above 10 µg/mL CPOR (

Figure 2A). Nevertheless, the cell viability of both HC and CCC were not changed when exposed to CPOR concentrations ranging from 1 to 25 µg/mL (

Figure 2B,C). In comparison to HC and CCC, VMC are more responsive to beta-caryophyllene-containing natural products such as copaiba oil-resin [

9,

10,

33] due to a higher quantity and density of cannabinoid receptors [

34,

35,

36] (

Figure 3A). Furthermore, the cell viability of VMC simultaneously exposed to 60 ηM rotenone and 1 µg/ml CPOR was higher than VMC only exposed to 60 ηM rotenone. The simultaneous exposure to 60 ηM rotenone and 25 µg/ml CPOR resulted in a neuroprotective effect only for HC, while the cell viability of CCC was not preserved (

Figure 3B,C).

The preservation of cell viability observed in this study suggests that CPOR has a neuroprotective effect on those neural e cells with a high number of cannabinoid receptors; in addition, beta-caryophyllene scavenges the free radicals resulting from the metabolic action of rotenone [

9,

11,

12]. Other studies have demonstrated that the interaction between beta-caryophyllene and cannabinoid type I receptors modulates ion channels such as calcium channels (Ca++), which reduces the activation of cell death pathways and the excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters that also could lead to cell death [

35,

36]. The fact that beta-caryophyllene can increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes throughout the modulation of cannabinoid type II receptors and inhibition of Caspase-3 may also be attributed to the neuroprotection effect of CPOR [

34,

35,

36]. Furthermore, the neuroprotective effect may result from the activation of the TrkA receptor through the phosphorylation of one G-protein subunit that is coupled to a cannabinoid receptor; thus, the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase decreases intracellular Ca++ levels and activates the kinases that promote cell survival [

34,

35,

36]. Another explanation for the neuroprotective effect of CPOR against rotenone toxicity is based on the decreased activation of microglial cells induced by cannabinoid type II receptors, which inhibits the apoptosis pathways and consequently promotes cell survival [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. In summary, CPOR figures as a promising neuroprotection agent against the toxicity of pesticides and insecticides, particularly throughout the preservation of VMC and HC cell viability.

5. Conclusions

VMC is more vulnerable to rotenone exposure than HC, which in turn is more vulnerable than CCC. Furthermore, exposure to at least 10 µg/ml CPOR reduced the cell viability for VMC, while HC and CCC did not present significant changes. Even when simultaneously exposed to rotenone, the cell viability of VMC and HC was surprisingly preserved by CPOR; however, this potential cytoprotective effect was not observed for CCC. This evidence may indicate the therapeutic use of CPOR to prevent neuronal damage caused by pesticides/insecticides such as rotenone.

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to complete data and took responsibility for the integrity of the information, text, and analysis accurac. Conceptualization: Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia, Dielly Catrina Favacho Lopes, and Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. Methodology: Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia, Dielly Catrina Favacho Lopes, Elizabeth Sumi Yamada, and Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. Validation: Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia, Anderson Manoel Herculano Oliveira da Silva, Karen Renata Herculano Matos de Oliveira, Arnaldo Jorge Martins Filho, and Walace Gomes Leal. Formal analysis: Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia. Investigation: Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia, Marcio Gonçalves Correa, Rebeca da Costa Gomes, and Rafael Dias de Souza. Resources: Dielly Catrina Favacho Lopes, Elizabeth Sumi Yamada, Arnaldo Jorge Martins Filho, and Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. Data curation: Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia, and Karen Renata Herculano Matos Oliveira. Resources: Dielly Catrina Favacho Lopes, Elizabeth Sumi Yamada, and Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. Writing—original draft preparation: Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia, Marcio Gonçalves Correa, Rebeca da Costa Gomes, Rafael Dias de Souza, and Thais Alves Lobão. Writing—review and editing: Elizabeth Sumi Yamada, Edmar Tavares da Costa, Dielly Catrina Favacho Lopes, Arnaldo Jorge Martins Filho, Walace Gomes Leal, Anderson Manoel Herculano Oliveira da Silva, Karen Renata Herculano Matos Oliveira, and Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. Supervision: Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. Project administration, Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. Funding acquisition: Carlomagno Pacheco Bahia. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, grants 310054/2018-4, 447835/2014-9, 483404/2013-6, 444967/2020-6, and 444982/2020-5) and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, grant PROCAD 21/2018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee on Research with Experimental Animals of the Federal University of Pará (CEPAE-UFPA: 216-14).

Data Availability Statement

The entire statistical analysis of data that supports the findings of this study is freely available and can be requested from Gabriel Mesquita da Conceição Bahia (gabriel.bahia@icb.ufpa.br).

Acknowledgments

The Health Science Institute and the Federal University of Pará are acknowledged for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no commercial or financial relationships that could represent a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Griesbach, G.S.; Hovda, D.A. Cellular and molecular neuronal plasticity. In: ; 2015, 681-690. [CrossRef]

- THOMPSONLA; DARWISHWS; IKENAKAY; NAKAYAMASMM; MIZUKAWAH; ISHIZUKAM Organochlorine pesticide contamination of foods in Africa: incidence and public health significance. J Vet Med Sci. 2017, 79, 751–764. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przedborski, S. The two-century journey of Parkinson disease research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017, 18, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betarbet, R.; Sherer, T.B.; MacKenzie, G.; Garcia-Osuna, M.; Panov, A.V.; Greenamyre, J.T. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000, 3, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, I. Neurodegenerative Diseases and Exposure to Pesticides in the Elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, N.; St-Hilaire, M.; Martinoli, M. , et al. Rotenone induces non-specific central nervous system and systemic toxicity. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 717–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.; Gastaldi, L.; Remedi, M.; Cáceres, A.; Landa, C. Rotenone-Induced Toxicity is Mediated by Rho-GTPases in Hippocampal Neurons. Toxicol Sci. 2008, 104, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.S.; Palmiter, R.D.; Xia, Z. Loss of mitochondrial complex I activity potentiates dopamine neuron death induced by microtubule dysfunction in a Parkinson’s disease model. J Cell Biol. 2011, 192, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, L.M.; de Sousa Vargas, F.; Barbosa, P.C.S.; Neves, J.K.O.; da Silva, J.A.; da Veiga-Junior, V.F. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Terpenoids from Copaiba (Copaifera spp.) Oleoresins. Molecules. 2012, 17, 3866–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães-Santos A, Santos DS, Santos IR, et al. Copaiba Oil-Resin Treatment Is Neuroprotective and Reduces Neutrophil Recruitment and Microglia Activation after Motor Cortex Excitotoxic Injury. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2012, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga Junior, V.F.; Pinto, A.C. O gênero copaifera L. Quim Nova. 2002, 25, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, V.F.; Rosas, E.C.; Carvalho, M.V.; Henriques, M.G.M.O.; Pinto, A.C. Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory activity of copaiba oils from Copaifera cearensis Huber ex Ducke, Copaifera reticulata Ducke and Copaifera multijuga Hayne—A comparative study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 112, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlemeyer, B.; Baumgart-Vogt, E. Optimized protocols for the simultaneous preparation of primary neuronal cultures of the neocortex, hippocampus and cerebellum from individual newborn (P0.5) C57Bl/6J mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2005, 149, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee JM, Shih AY, Murphy TH, Johnson JA. NF-E2-related Factor-2 Mediates Neuroprotection against Mitochondrial Complex I Inhibitors and Increased Concentrations of Intracellular Calcium in Primary Cortical Neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 37948–37956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.E.; Sapkota, K.; Choi, J.H. , et al. Rutin from Dendropanax morbifera Leveille Protects Human Dopaminergic Cells Against Rotenone Induced Cell Injury Through Inhibiting JNK and p38 MAPK Signaling. Neurochem Res. 2014, 39, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currò, M.; Saija, C.; Trainito, A. , et al. Rotenone-induced oxidative stress in THP-1 cells: biphasic effects of baicalin. Mol Biol Rep. 2023, 50, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- an Laar, V.; Arnold, B.; Berman, S. Primary Embryonic Rat Cortical Neuronal Culture and Chronic Rotenone Treatment in Microfluidic Culture Devices. BIO-PROTOCOL. 2019, 9(6). [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denizot, F.; Lang, R. Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival. J Immunol Methods. 1986, 89, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANDRADEJN; COSTANETOEM; BRANDÃOH Using ichthyotoxic plants as bioinsecticide: A literature review. Rev Bras Plantas Med. 2015, 17, 649–656. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, X. , et al. Rotenone-Induced Neurodegeneration Is Enabled by a p38-Parkin-ROS Signaling Feedback Loop. J Agric Food Chem. 2021, 69, 13942–13952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, T.; Chatterjee, A.; Swarnakar, S. Rotenone induced neurodegeneration is mediated via cytoskeleton degradation and necroptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Res. 2023, 1870, 119417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao L; Cao M; G hua, D.; X mei, Q.. Huangqin Decoction Exerts Beneficial Effects on Rotenone-Induced Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease by Improving Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Alleviating Metabolic Abnormality of Mitochondria. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Trombetta-Lima, M.; Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Dolga, A.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases: A focus on iPSC-derived neuronal models. Cell Calcium. 2021, 94, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Aki, T.; Unuma, K.; Uemura, K. Chemically Induced Models of Parkinson’s Disease: History and Perspectives for the Involvement of Ferroptosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Yao, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, X.; Huang, X. Therapeutic and Neuroprotective Effects of Bushen Jianpi Decoction on a Rotenone-Induced Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Teoh SL, ed. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2022, 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.S.; Teixeira, M.H.; Russell, D.A.; Hirst, J.; Arantes, G.M. Mechanism of rotenone binding to respiratory complex I depends on ligand flexibility. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 6738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, M.Z.; Khatoon, R.; Talat, F.; Alam, M.M.; Tabassum, H.; Parvez, S. Melatonin Mitigates Rotenone-Induced Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Drosophila melanogaster Model of Parkinson’s Disease-like Symptoms. ACS Omega. 2023, 8, 7279–7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, Y.L.; Pristupa, Z.B.; Herman, M.M.; Niznik, H.B.; Kleinman, J.E. The dopamine transporter and dopamine D2 receptor messenger RNAs are differentially expressed in limbic- and motor-related subpopulations of human mesencephalic neurons. Neuroscience. 1994, 63, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, M.V.N.; Mesquita da Conceição Bahia, G.; Gonçalves Correa, M., et al. Neuroprotective effects of crude extracts, compounds, and isolated molecules obtained from plants in the central nervous system injuries: a systematic review. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, G.A.G.; da Silva, N.C.; de Souza, J. , et al. In vitro and in vivo antimalarial potential of oleoresin obtained from Copaifera reticulata Ducke (Fabaceae) in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. Phytomedicine. 2017, 24, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondon, F.C.M.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L.; Accioly, M.P. , et al. In vitro efficacy of Coriandrum sativum, Lippia sidoides and Copaifera reticulata against Leishmania chagasi. Rev Bras Parasitol Veterinária. 2012, 21, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Di Minno, A.; Santarcangelo, C.; Khan, H.; Daglia, M. Improvement of Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction by β-Caryophyllene: A Focus on the Nervous System. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SVIZENSKAI; DUBOVYP; SULCOVAA Cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2), their distribution, ligands and functional involvement in nervous system structures — A short review. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008, 90, 501–511. [CrossRef]

- Gertsch J, Leonti M, Raduner S, et al. Beta-caryophyllene is a dietary cannabinoid. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008, 105, 9099–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Gálvez, Y.; Palomo-Garo, C.; Fernández-Ruiz, J.; García, C. Potential of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor as a pharmacological target against inflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2016, 64, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, H.; Azimullah, S.; Haque, M.E.; Ojha, S.K. Cannabinoid Type 2 (CB2) Receptors Activation Protects against Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation Associated Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in Rotenone Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurosci. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, L.C.; Straliotto, M.R.; Engel, D.; Hort, M.A.; Dutra, R.C.; de Bem, A.F. β-Caryophyllene protects the C6 glioma cells against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity through the Nrf2 pathway. Neuroscience. 2014, 279, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).