2.1. The topological representation of spin by knot

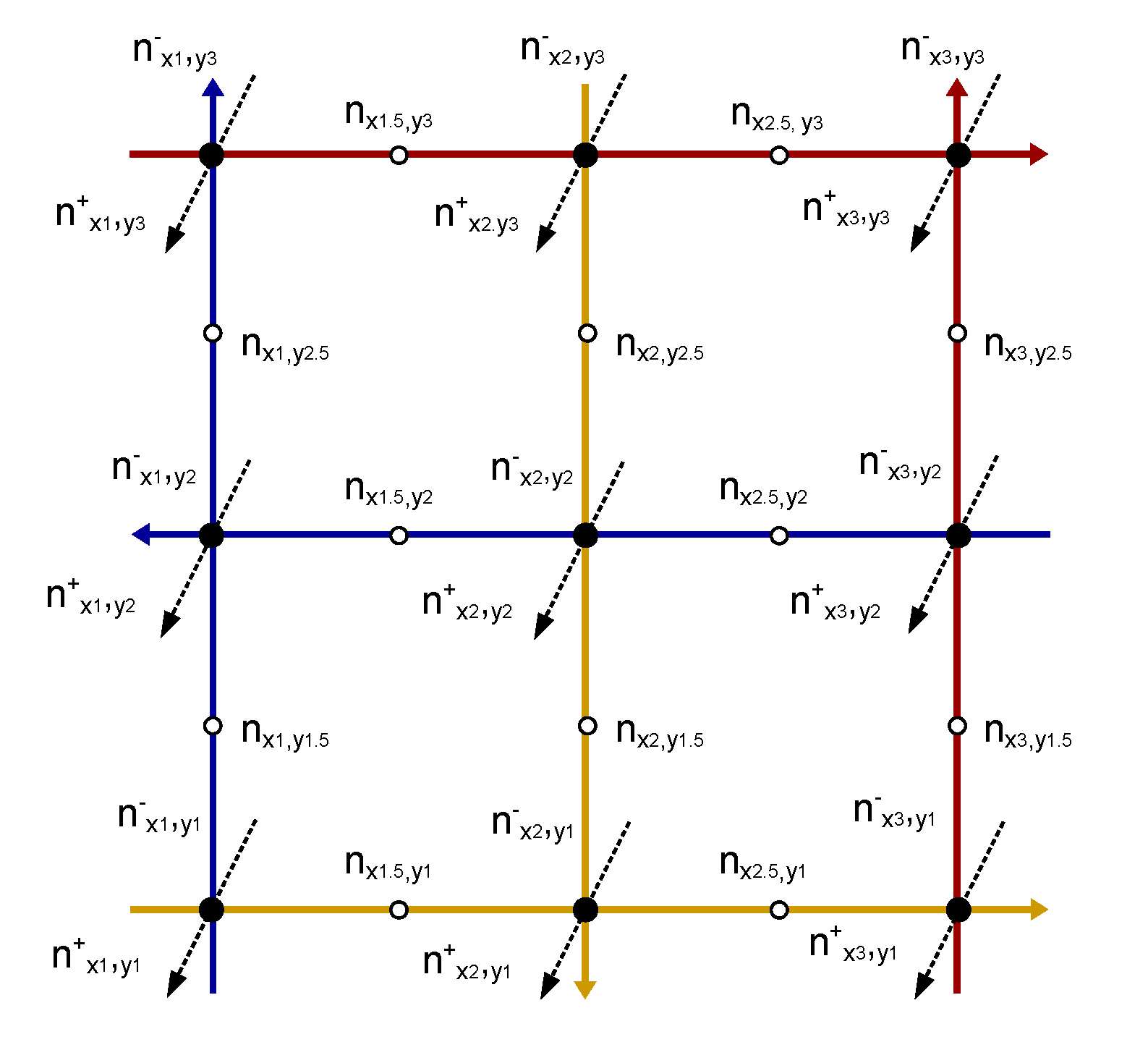

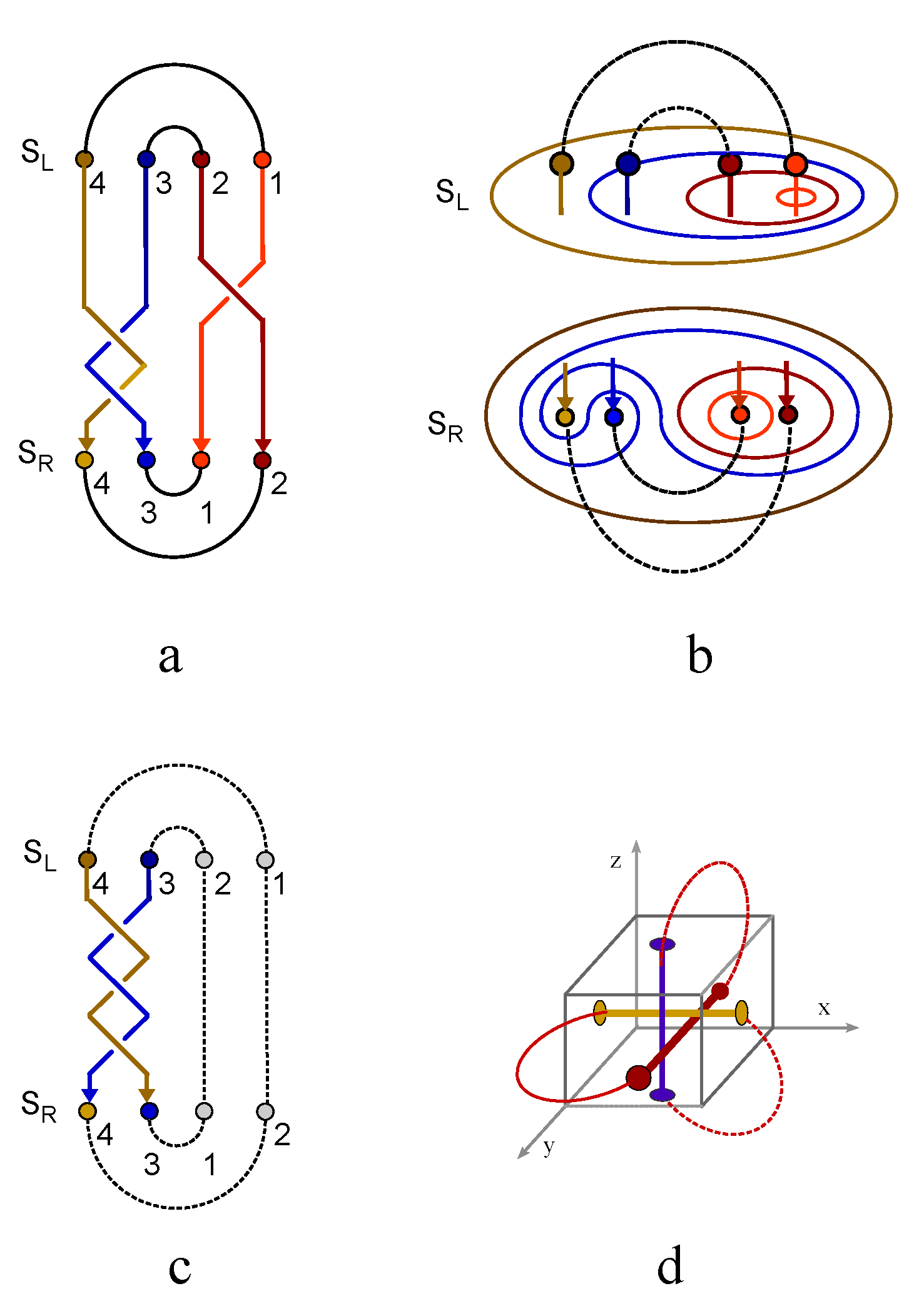

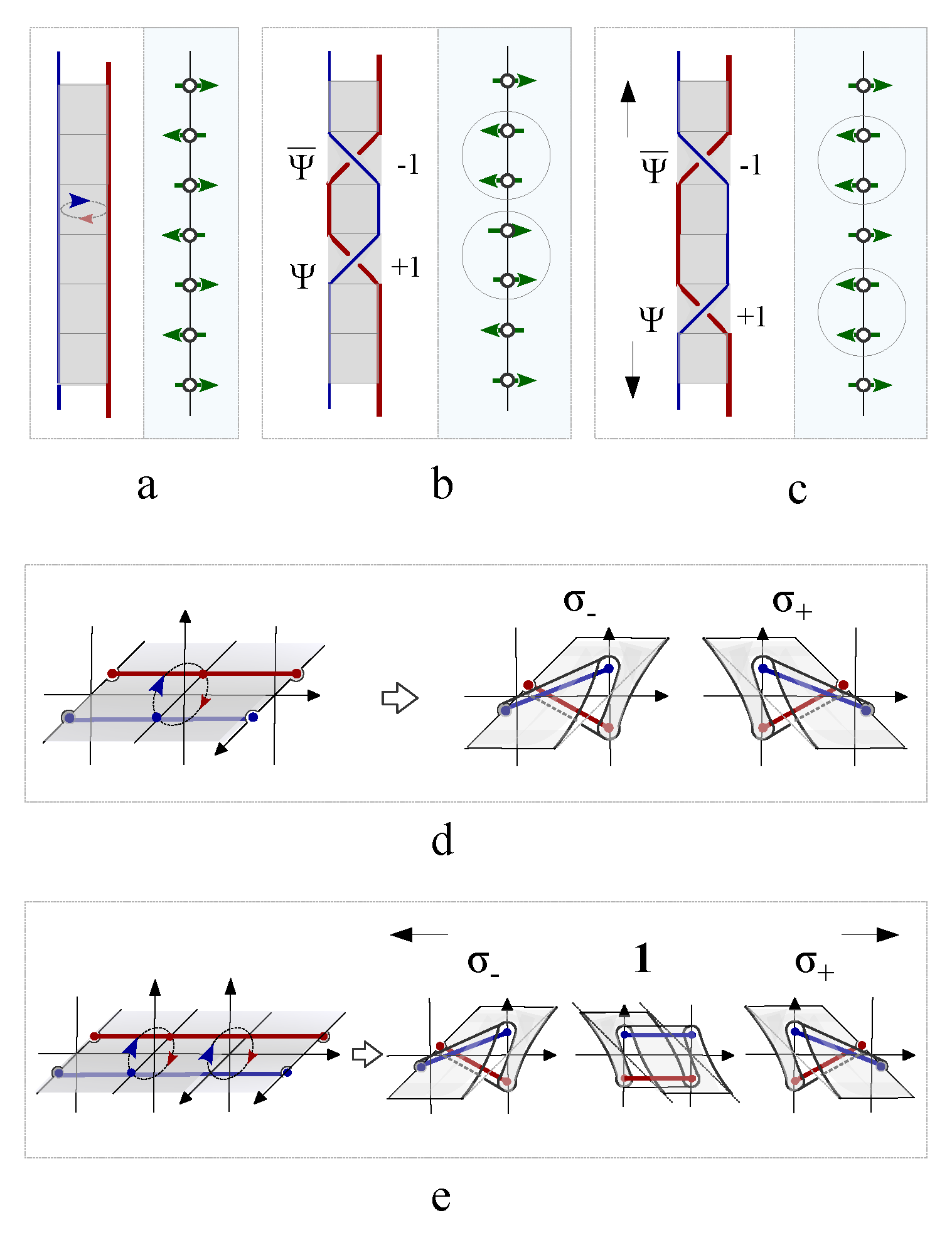

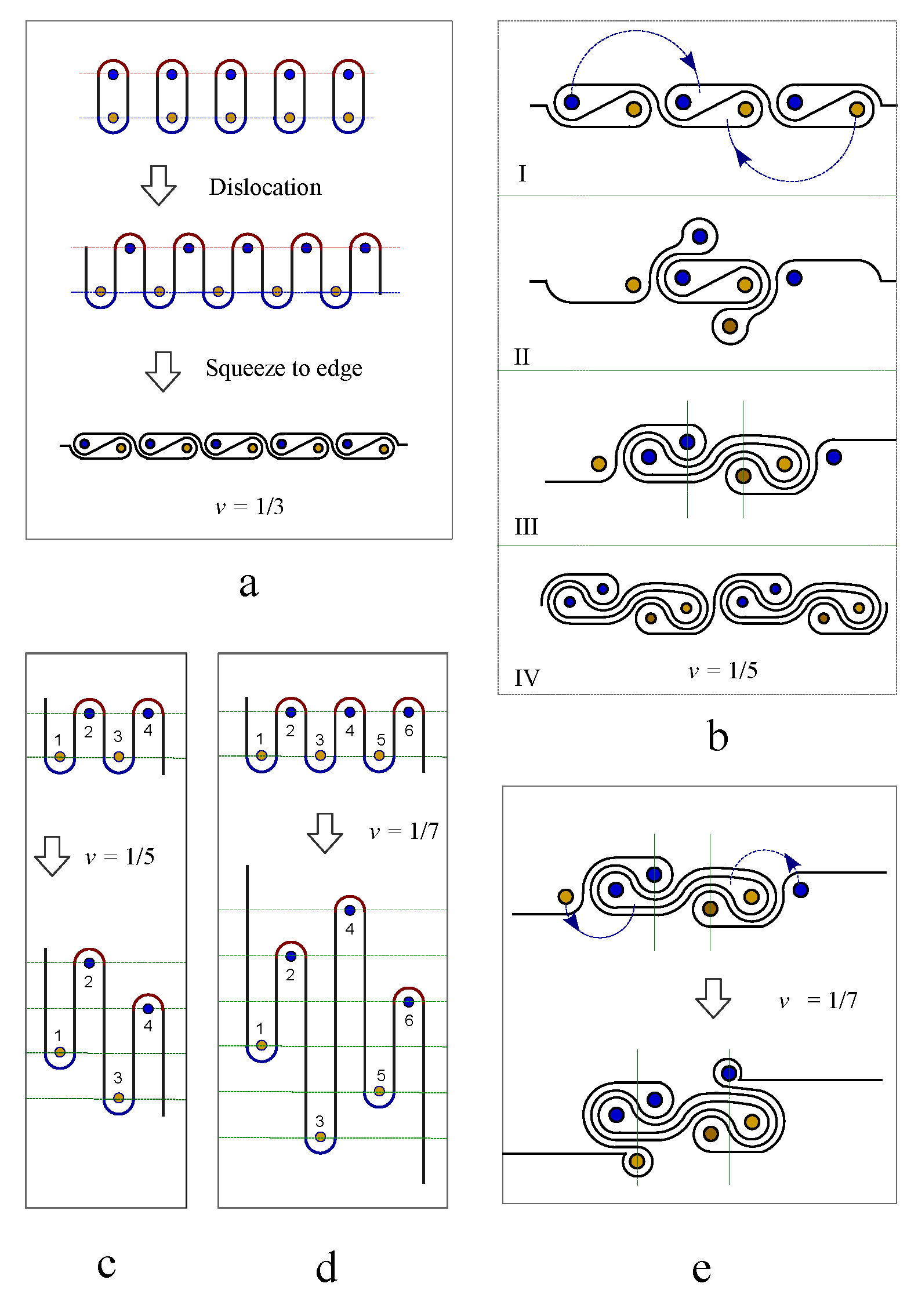

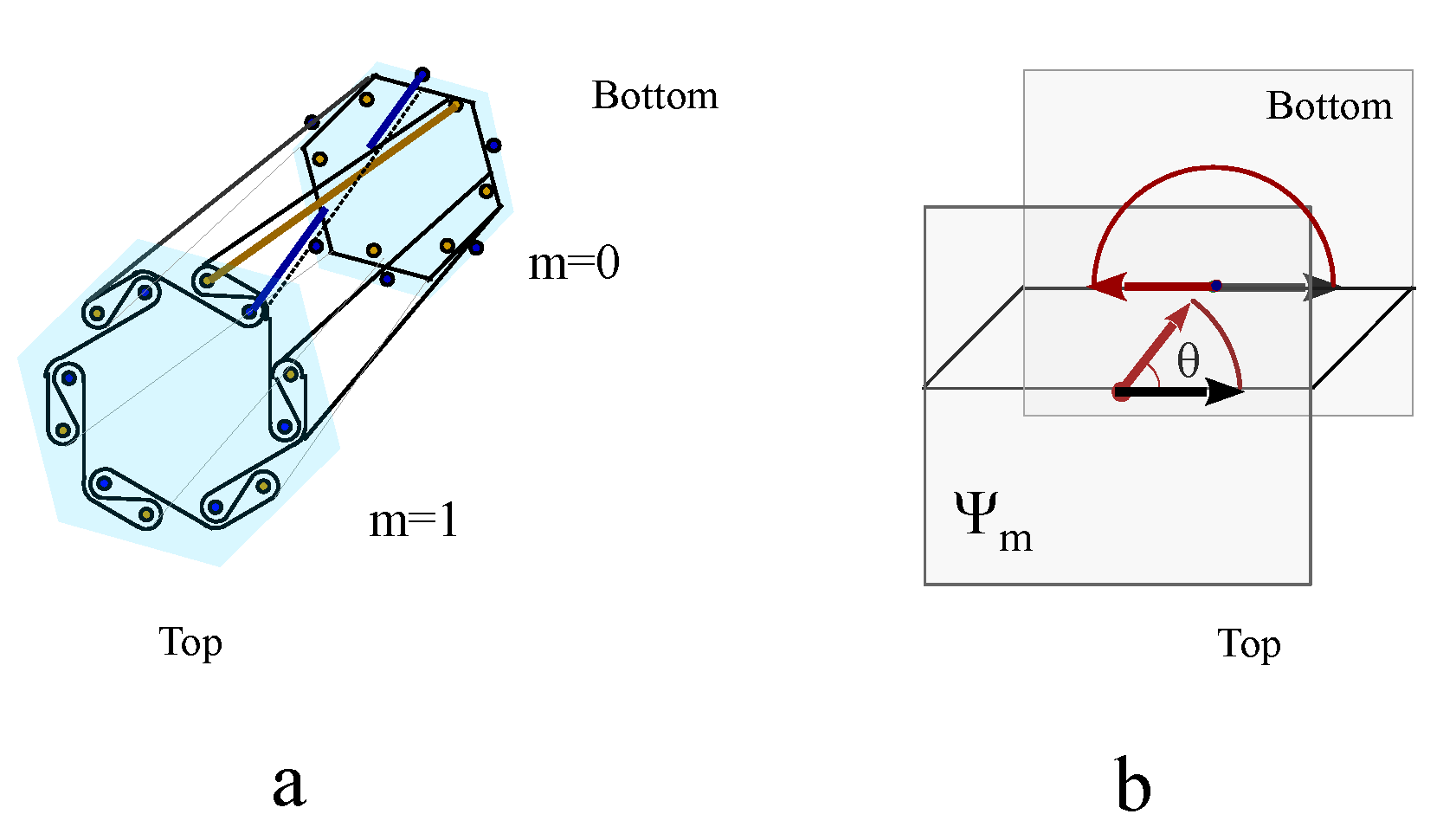

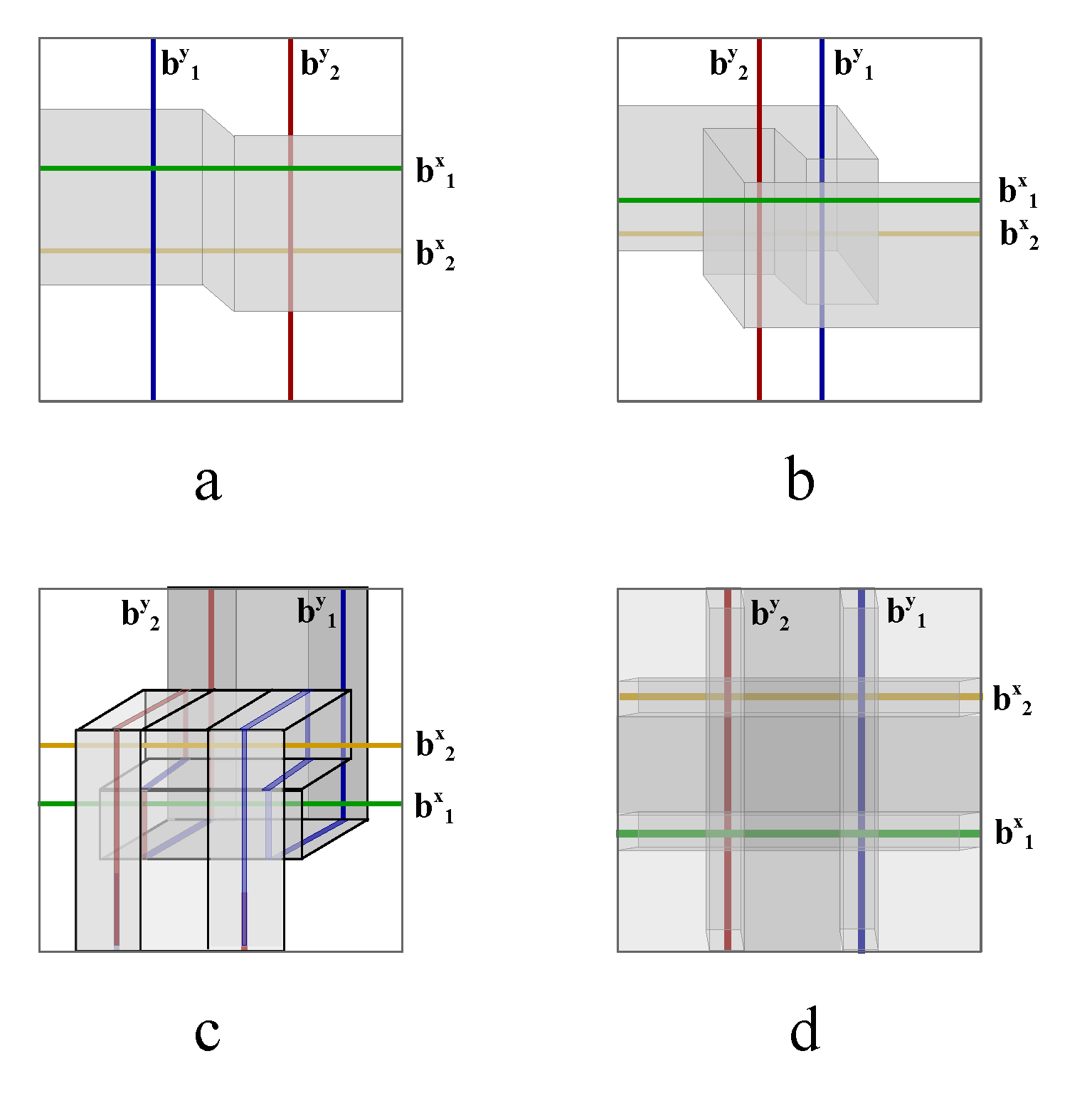

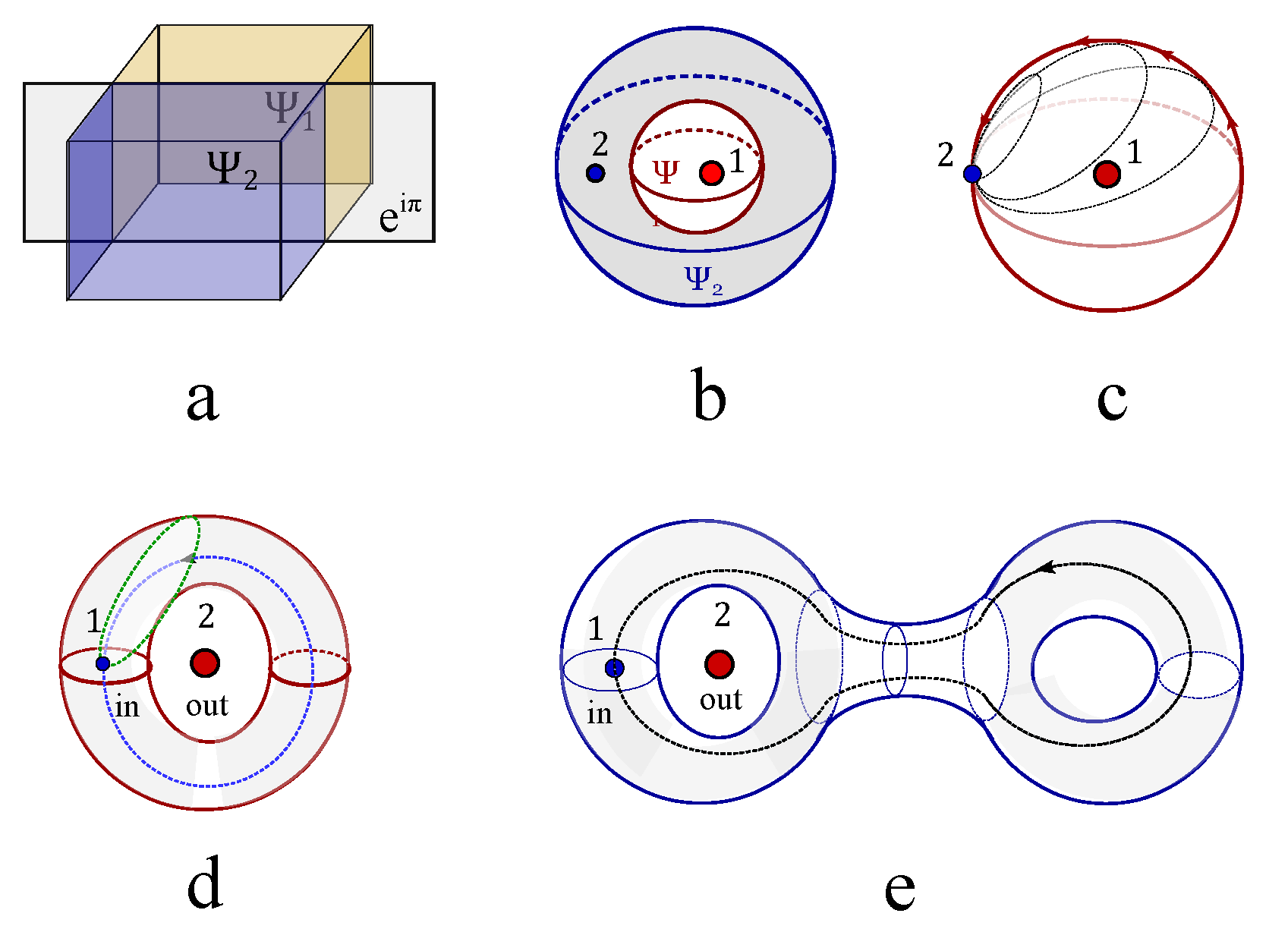

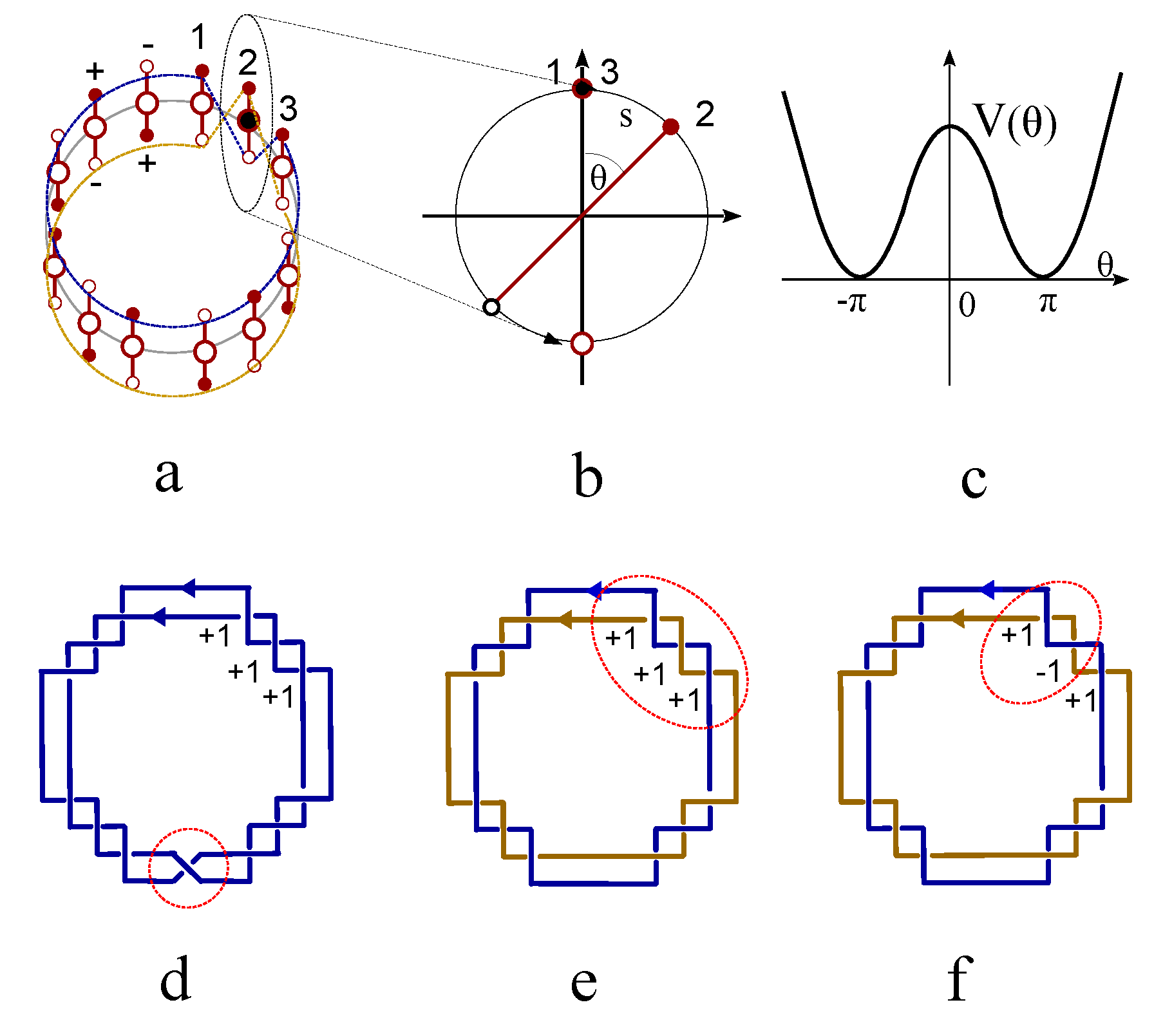

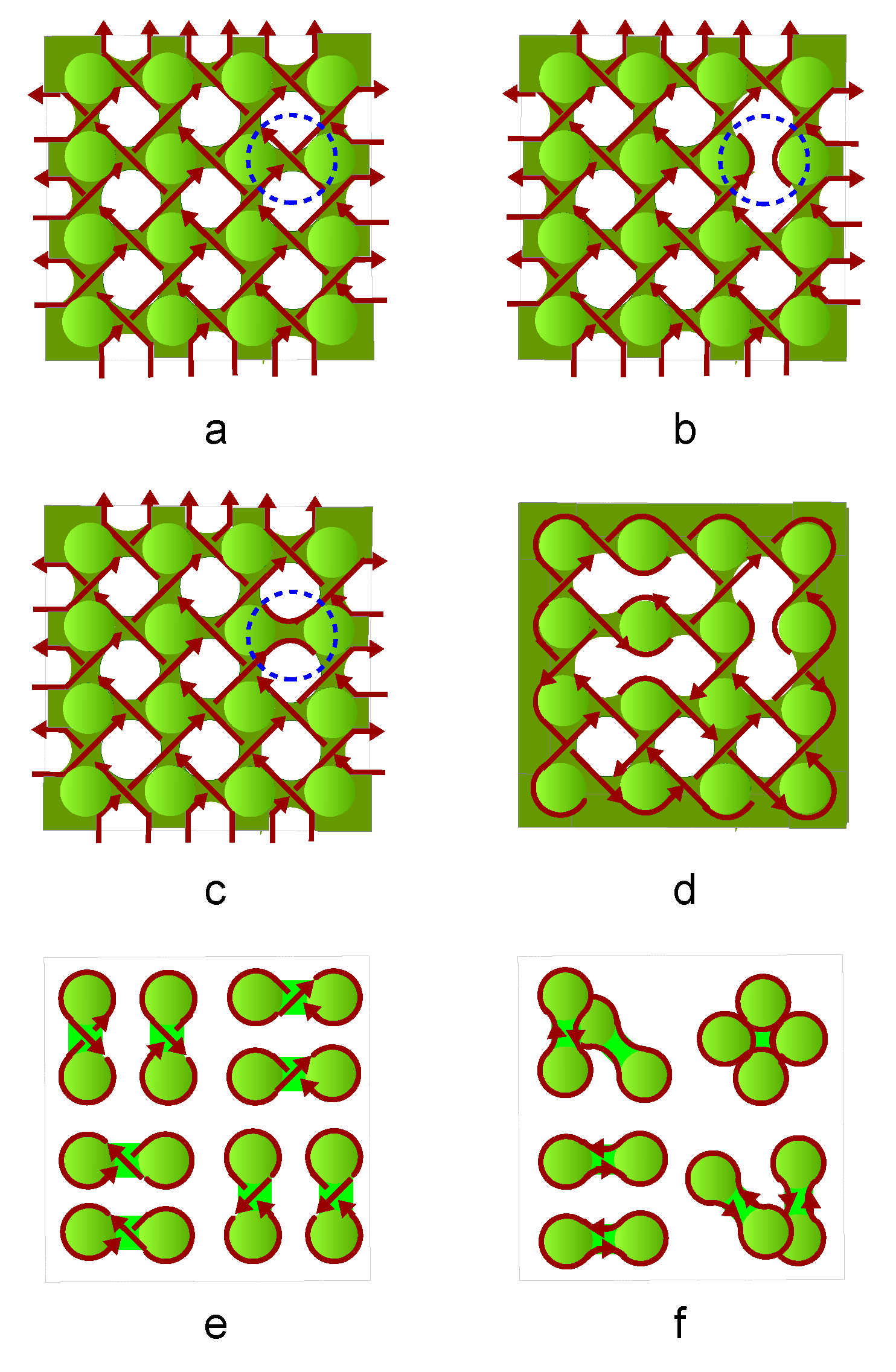

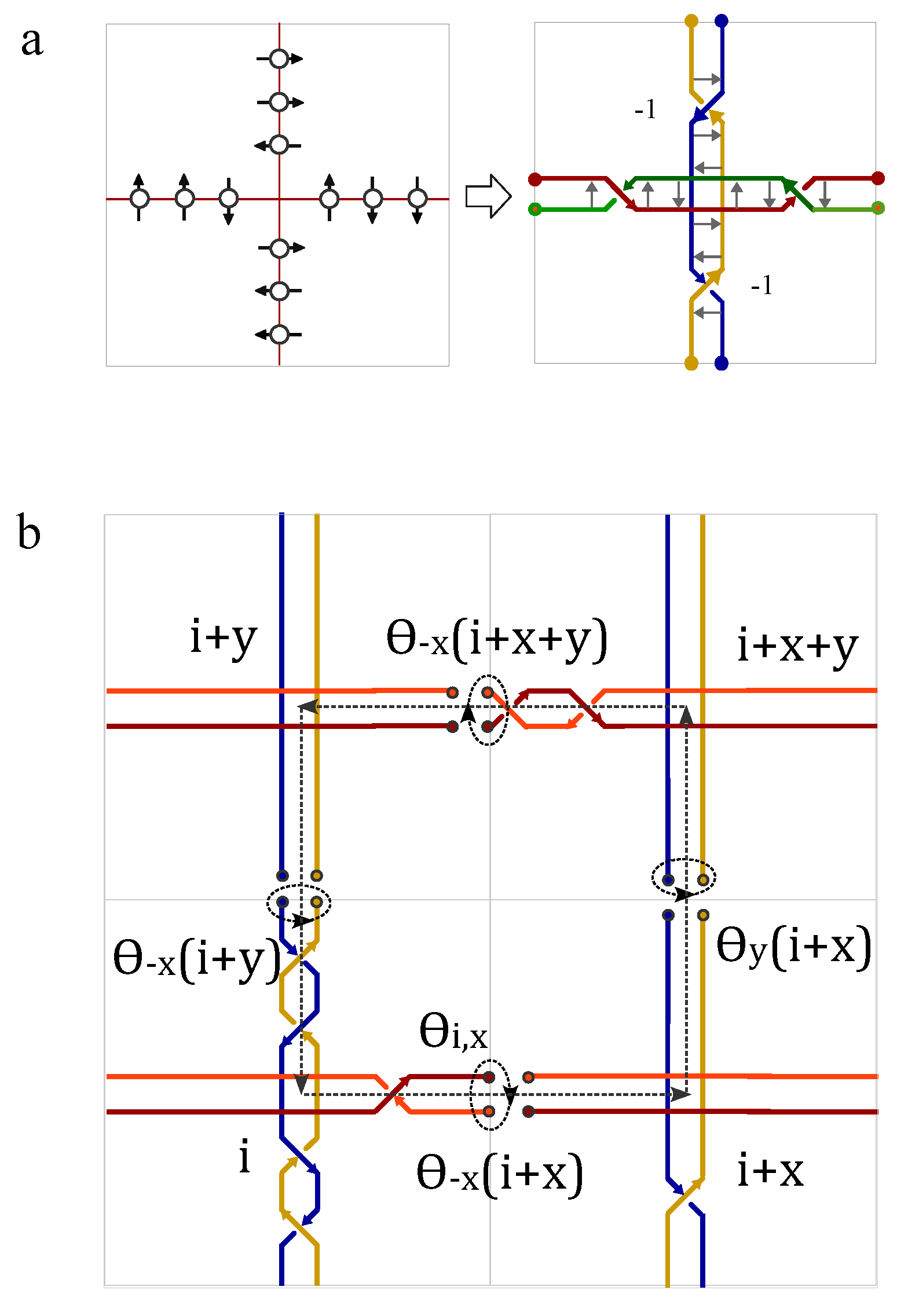

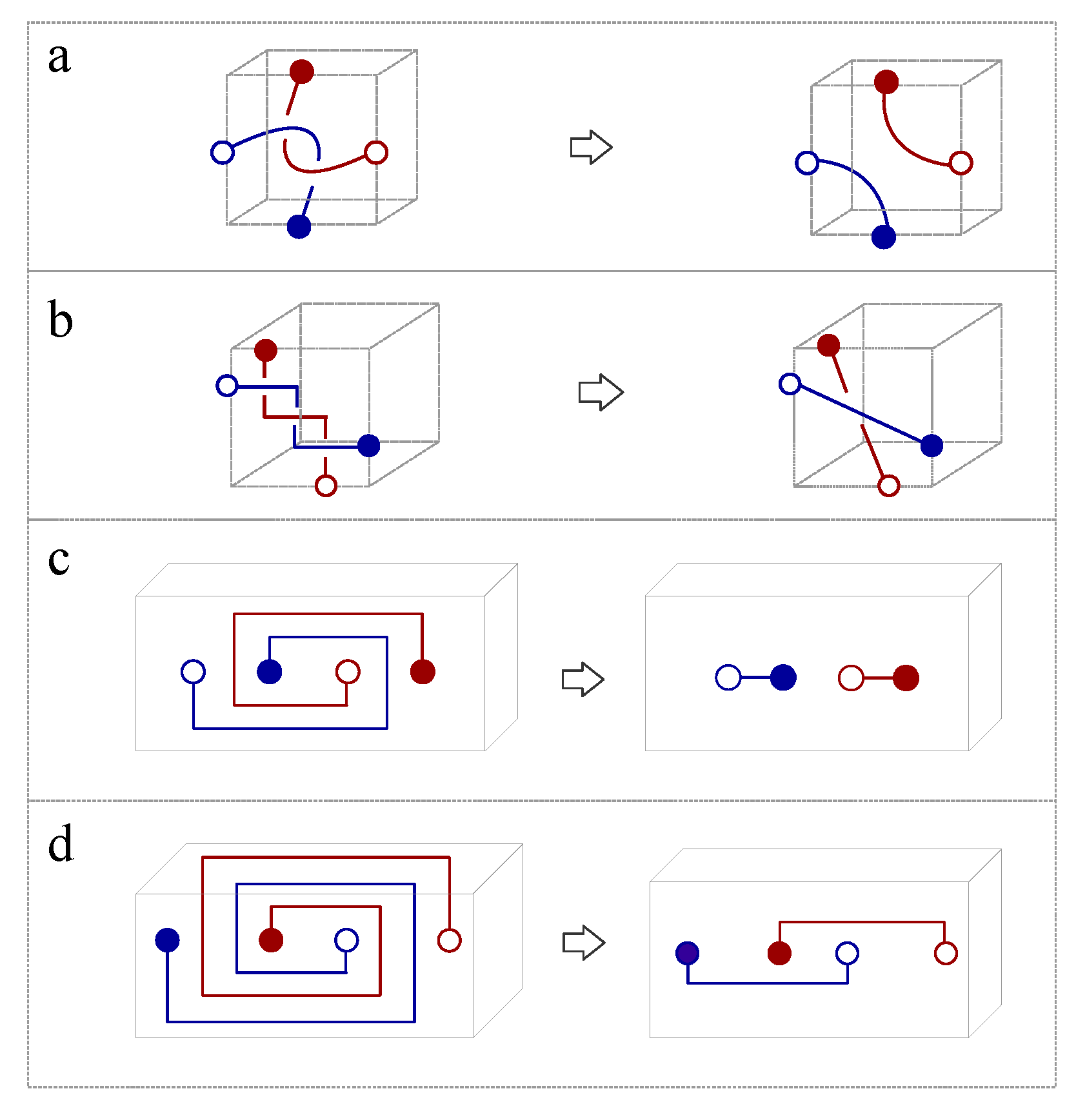

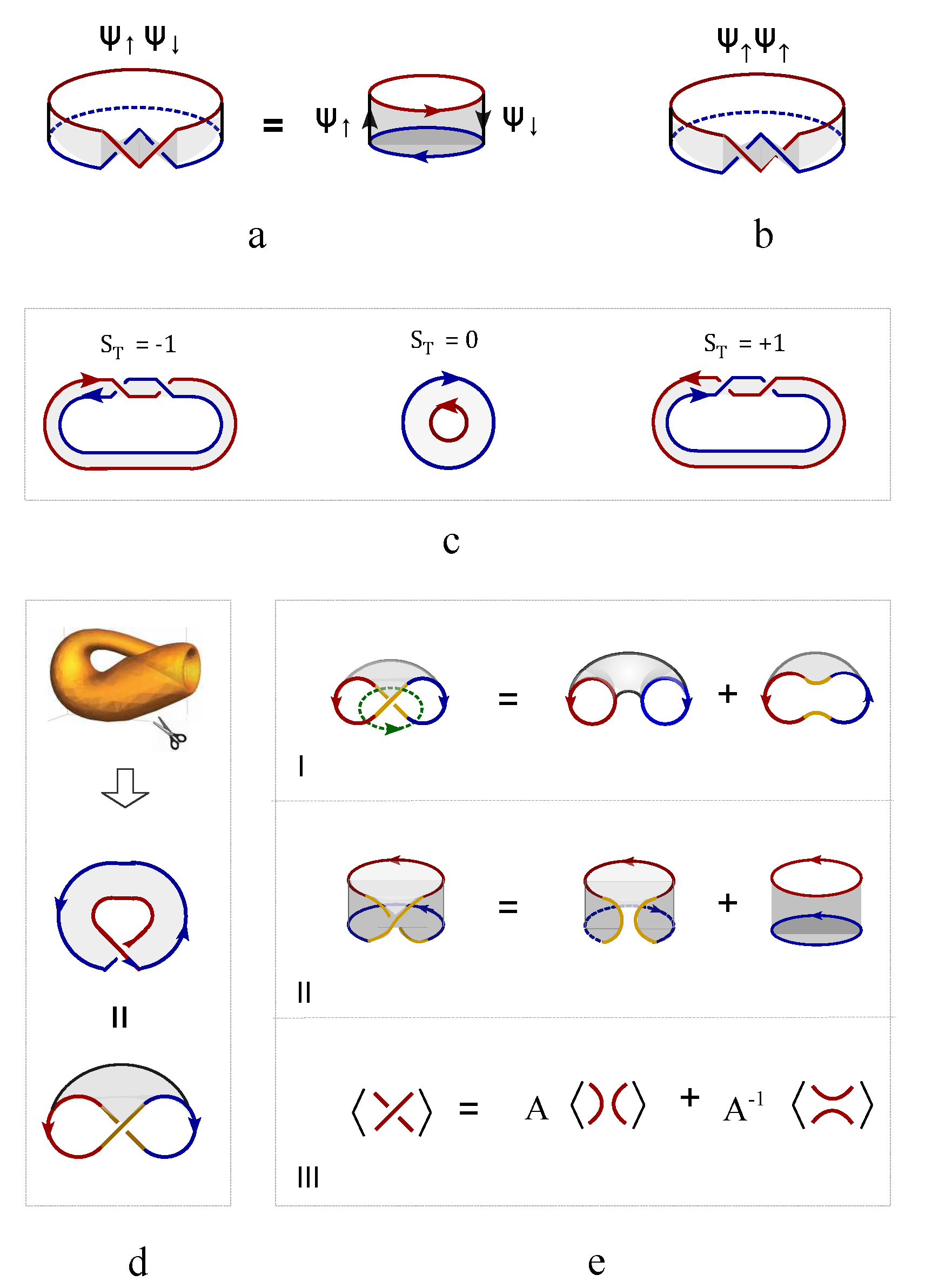

The classical Ising spin

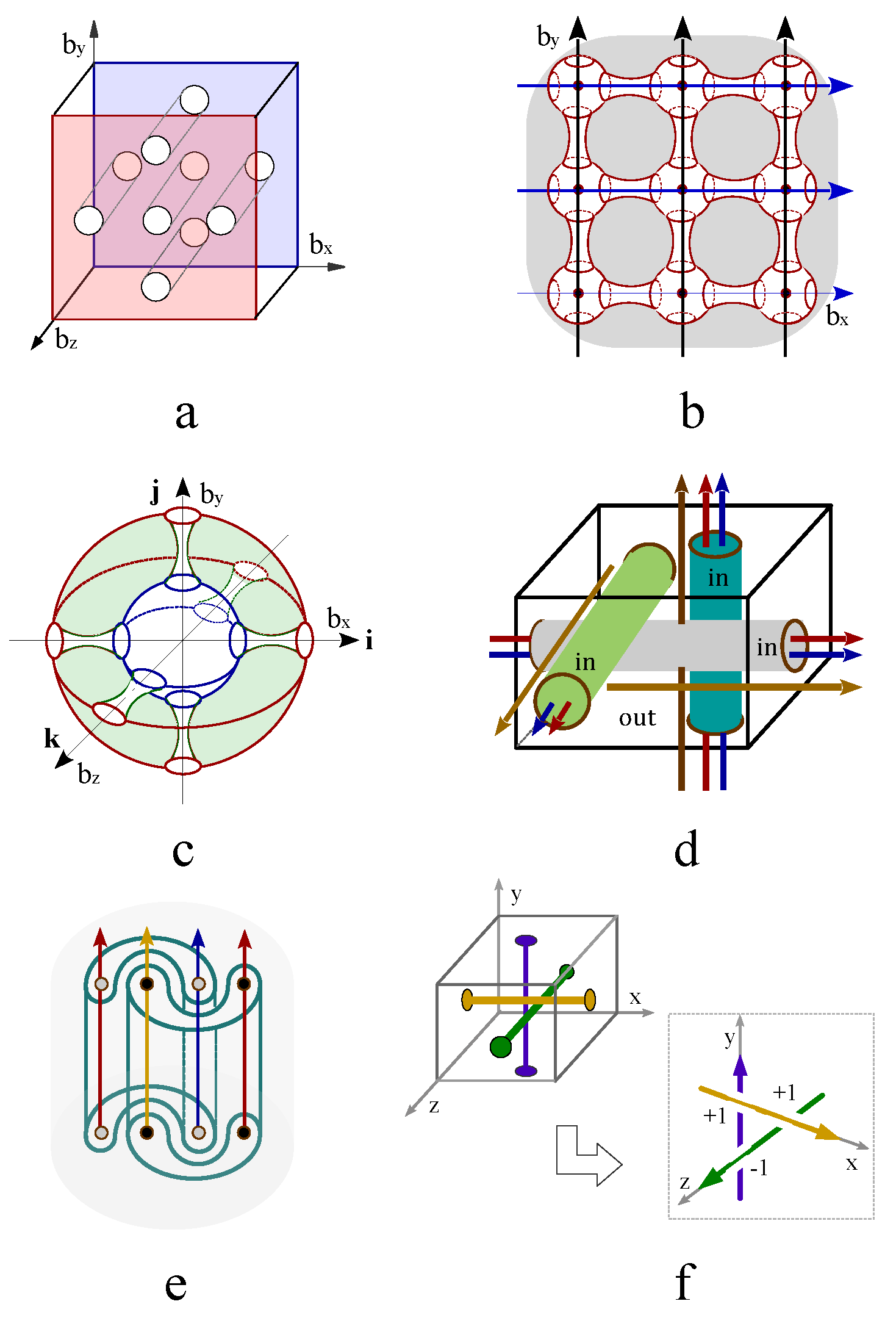

is modeled as a rotating quantum fluid droplet, featuring two topological defects at the north and south poles, each carrying an identical winding number

(

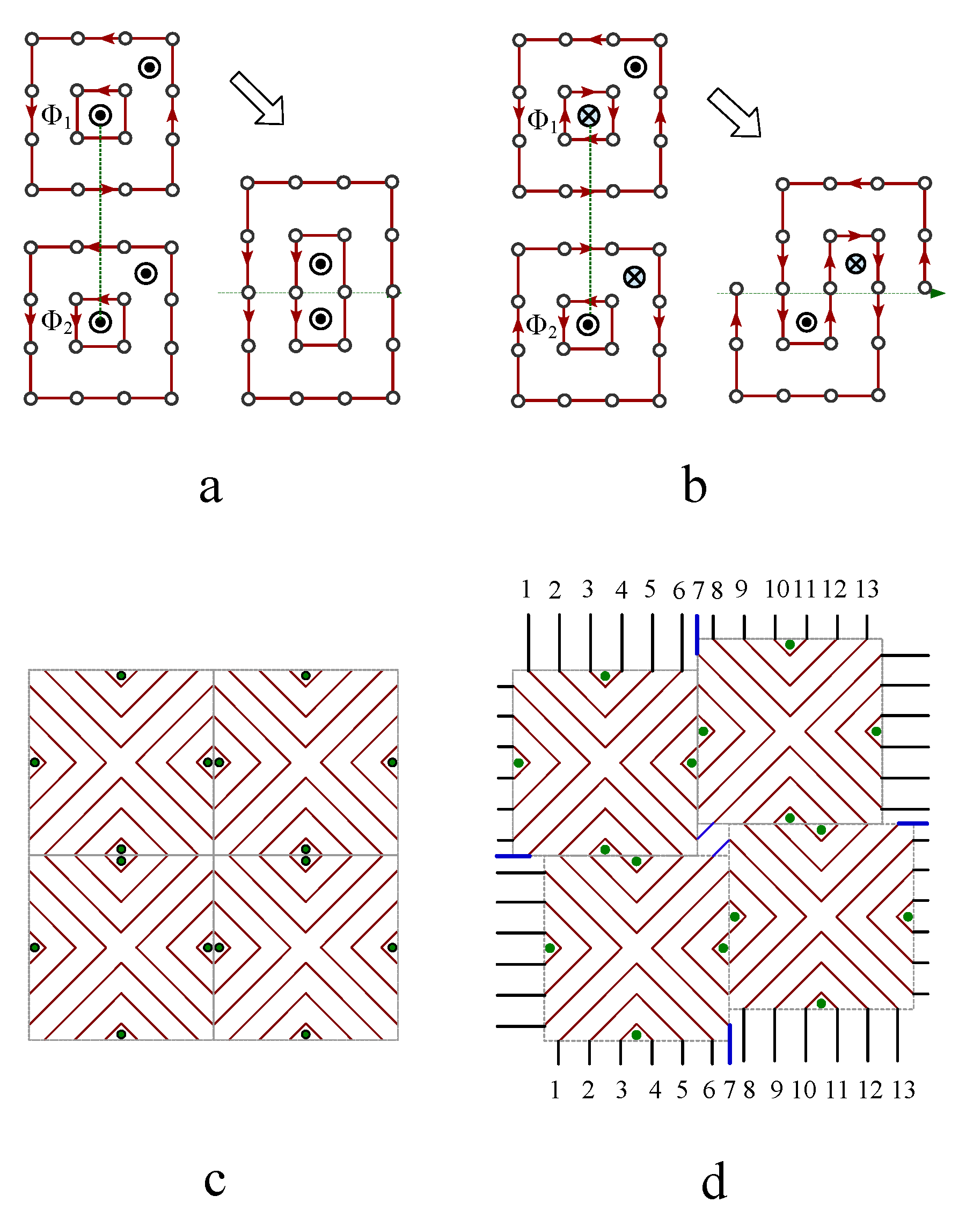

Figure 1a). This Ising spin characterize the angular momentum of a rotating charged fluid, which is ideally simplified into an electric current loop (

Figure 1b). The Ising spin represents the two opposite states of magnetic dipole moment (

Figure 1b). This topological representation of Ising spin satisfies the topological constraint that the sum of the winding numbers equals the Euler number (or Chern number) of the underlying manifold,

. The spherical surface of quantum droplet results in

. Duan’s topological current theory [

21] suggests there exist a topological line defect along which the density of wave function vanishes (

Figure 1a),

where

the vectorial velocity field that is tangential to the surface of the droplet. The line defect connects the north pole and south pole. Even though the two topological defects carry the same topological charge, but are assigned with opposite magnetic charges (

Figure 1c). Free spins without interaction are represented by directed loops without intersections (

Figure 1d). Interacted spins are represented by intersecting loops(

Figure 1e-h), i.e., cutting each loop current to generate two ending points and glue them with the open endings of another loop (

Figure 1e-h). The ferromagnetic coupling is represented by one giant loop made of the fusion of two small loops without self-crossings (

Figure 1e). For the antiferromagnetic coupling, the self-crossing of the giant loop made of two nearest neighboring loops is inevitable (

Figure 1f). Different crossing states are characterized by chiral index,

, where

indicated a positive chirality that the four fingers of the right hand first point into the direction of the current above the crossing point and then bend to the direction of the current underneath the crossing point (

Figure 1g), while the opposite case is labeled by a negative crossing index (

Figure 1h).

A classical rotating droplet is a good representation of Ising spin, but is inadequate to take into account of the phase factor of a quantum particle. A quantum fluid droplet is described by a wavefunction

that obeys Schr

dinger equation

. The Schr

dinger equation is equivalently transformed into a pair of fluid dynamic equations by Bohm [

20],

The quantum character of a particle is governed by the potential combination of a classical potential

V and the well known Bohm potential

,

Here we substitute the identity equations,

into the Bohm potential Eq. (

3) to decomposes

into the sum of two terms,

The Bohm potential approaches to negative infinity at the zero points of wave function

. For a nonzero wave function

, the first term on the right hand side of Bohm potential Eq. (

5) vanishes. The second term of Bohm potential Eq. (

5) is determined by the gradient of wavefunction. The Bohm potential turns into zero at the extremal points of wavefunction, i.e.,

. According to Duan’s topological current theory [

21], the sum of topological charges of zero points of wavefunction is determined by the topology of spacetime manifold. Therefore a quantum particle is born to carry the topological information of the space time manifold at

, which usually is eliminated in local dynamics. The Bohm potential reaches the minimal (maximal) point when the gradient of wavefunction

is positive (negative). The particle moves along the minimal points of Bohm potential under the mathematical constraints

. The quantum fluid droplet deforms into different oscillating modes following Bohm potential. The velocity field on the surface of quantum droplet is defined as

The velocity field

as showed in

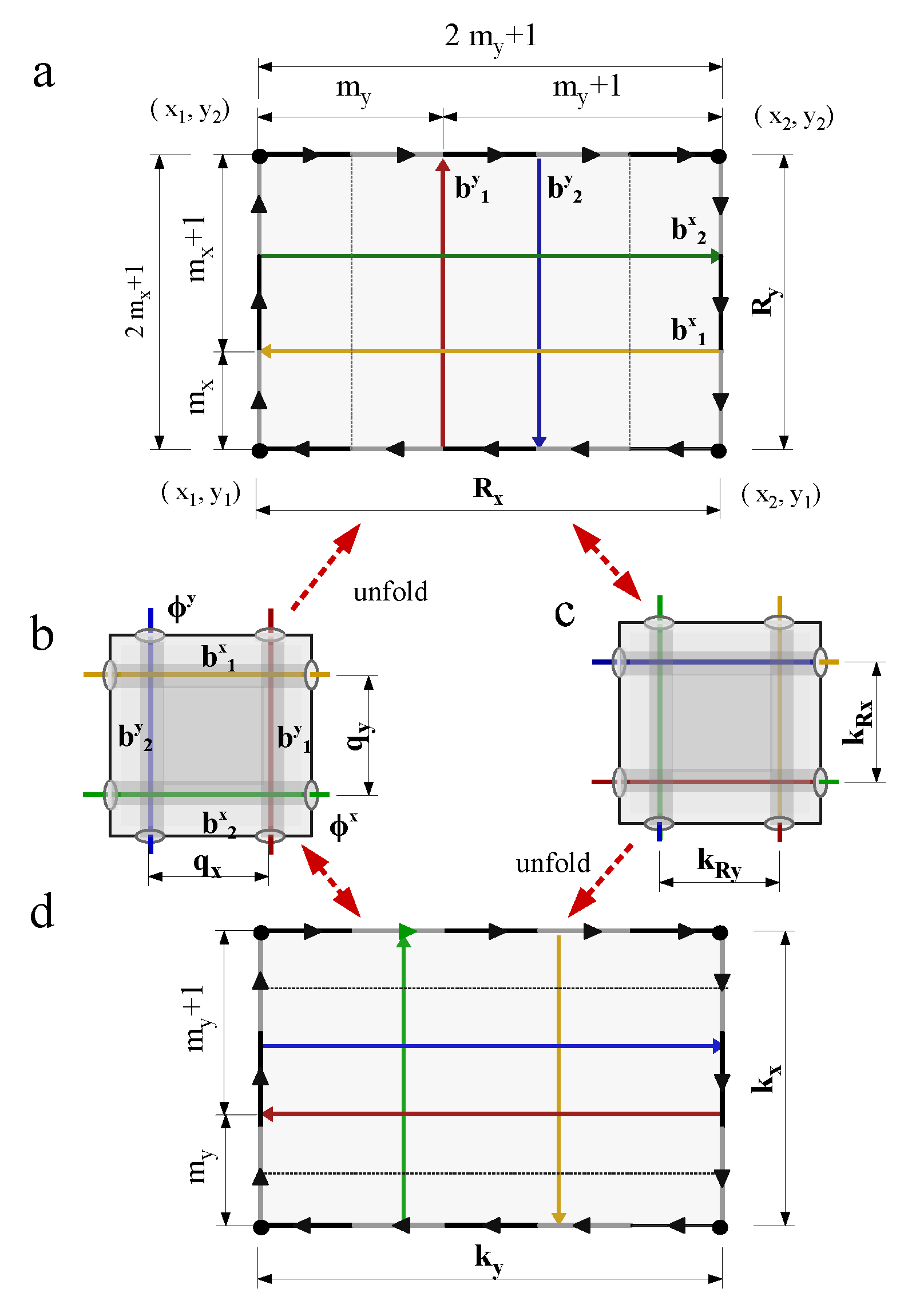

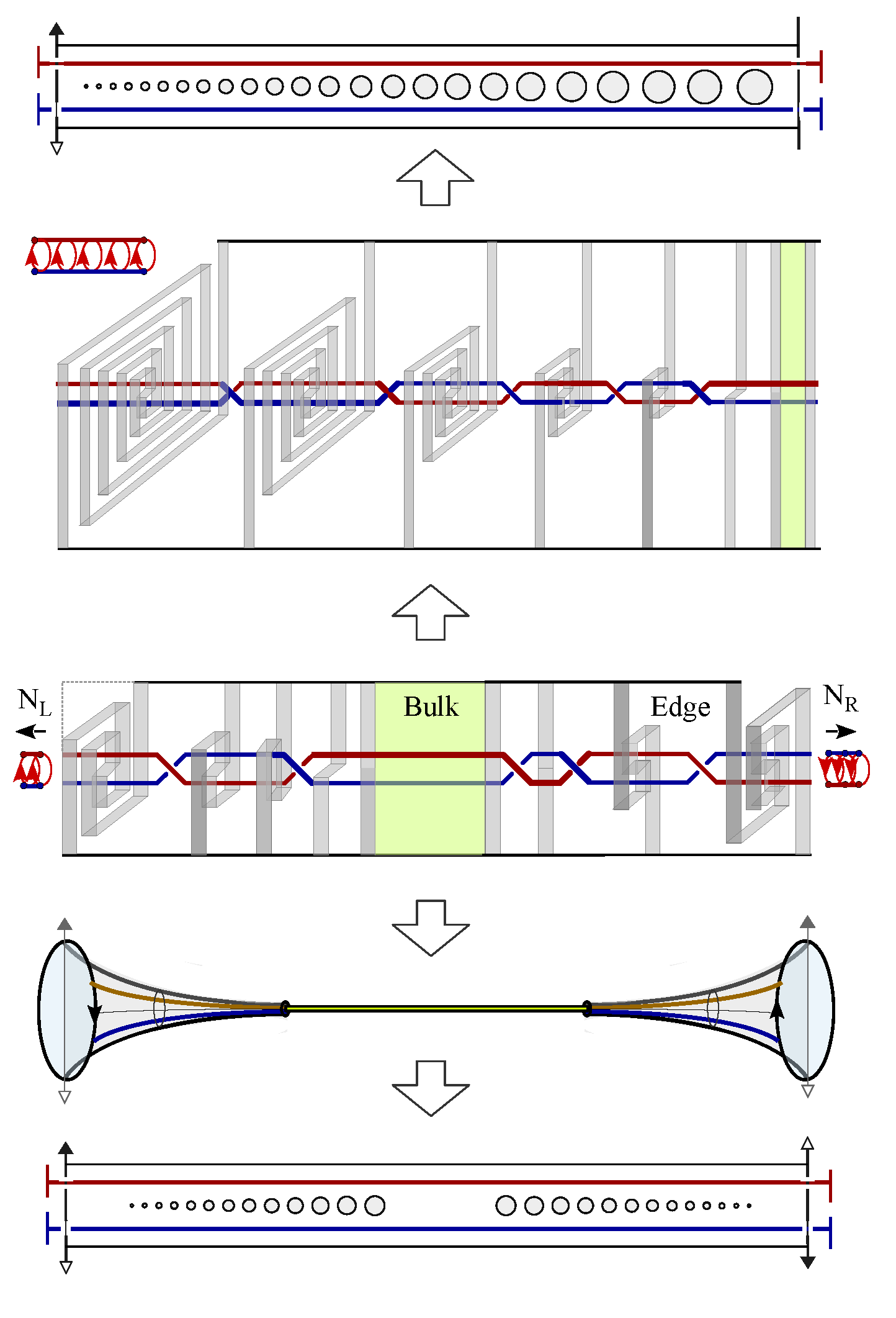

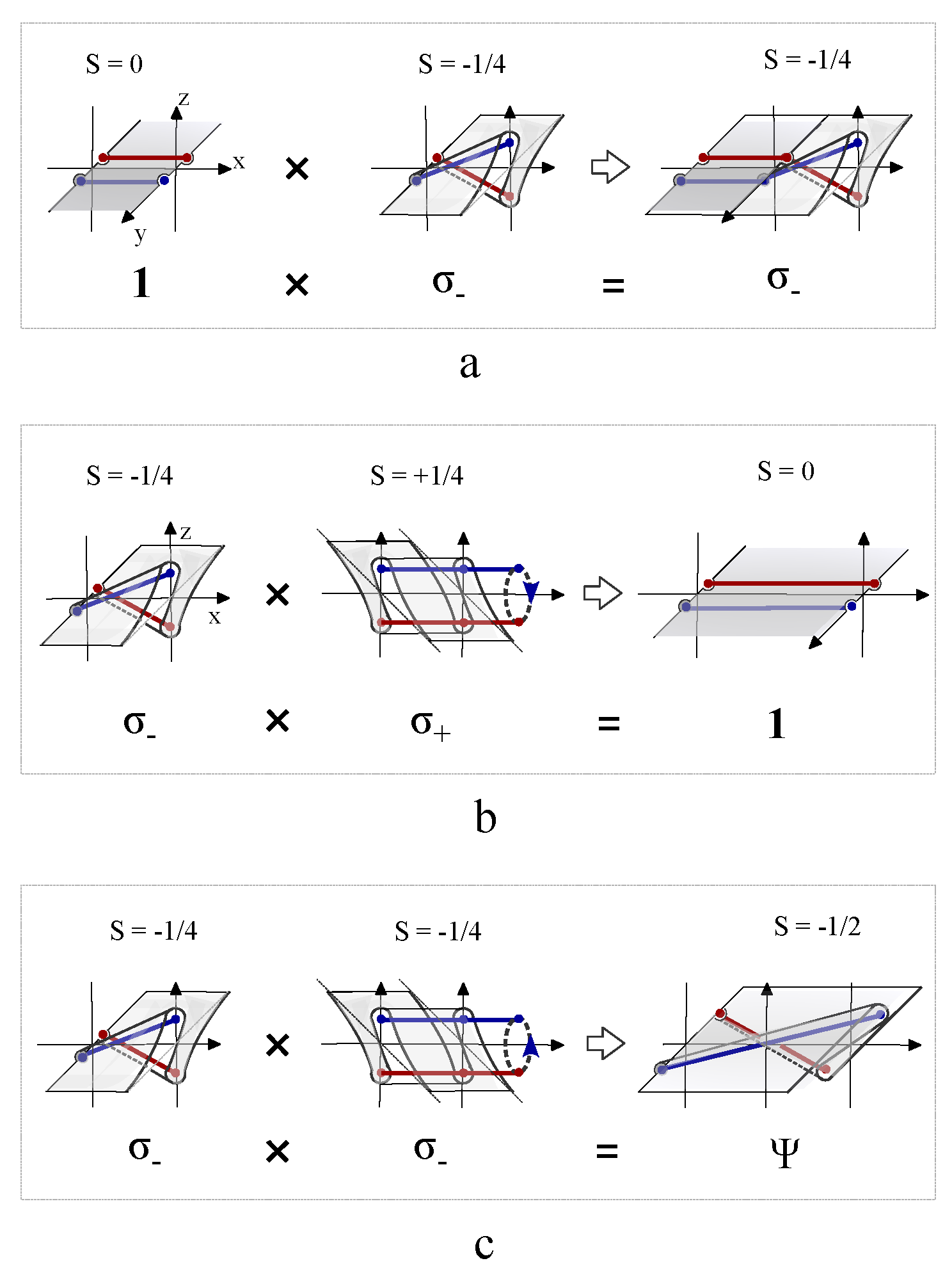

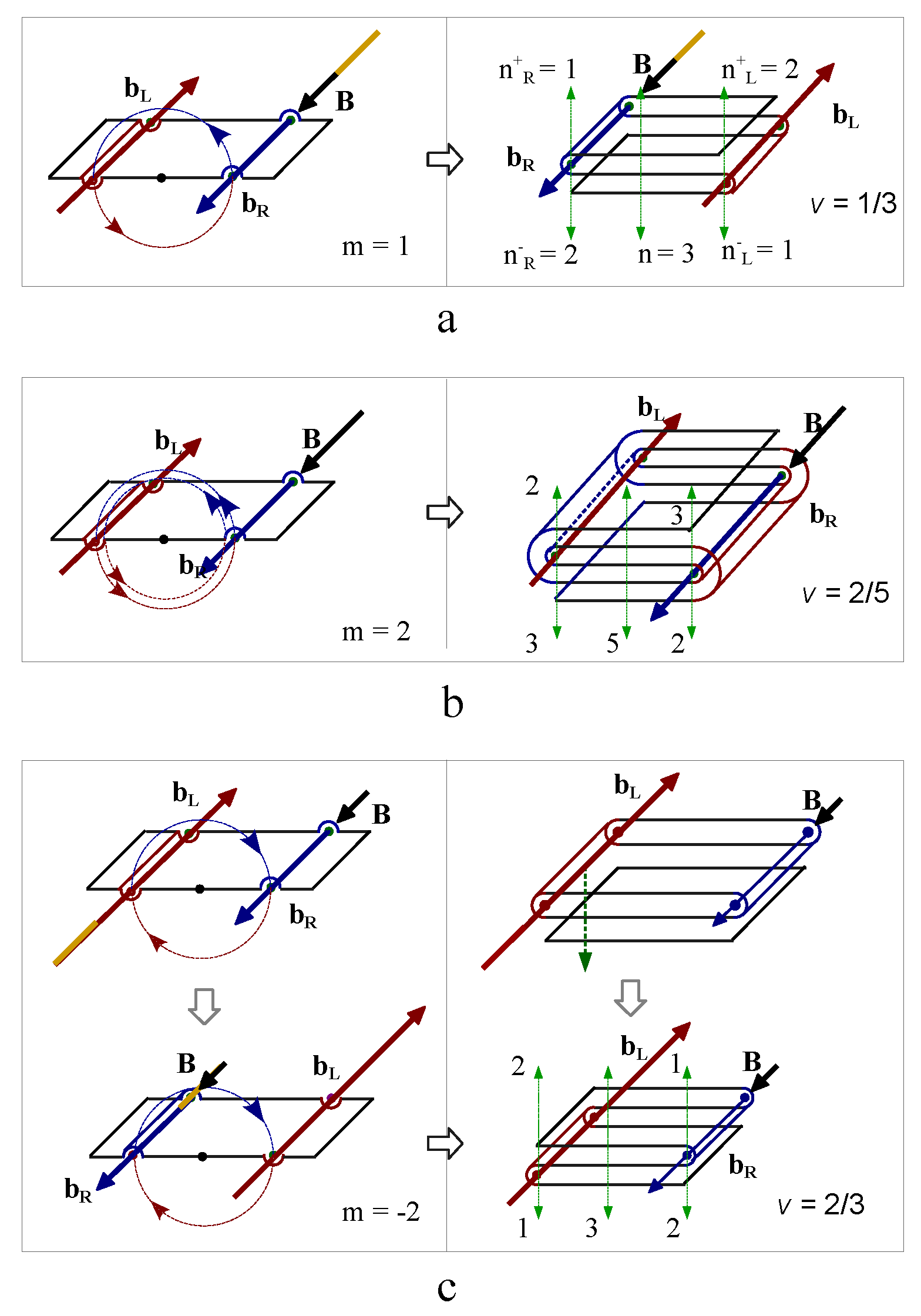

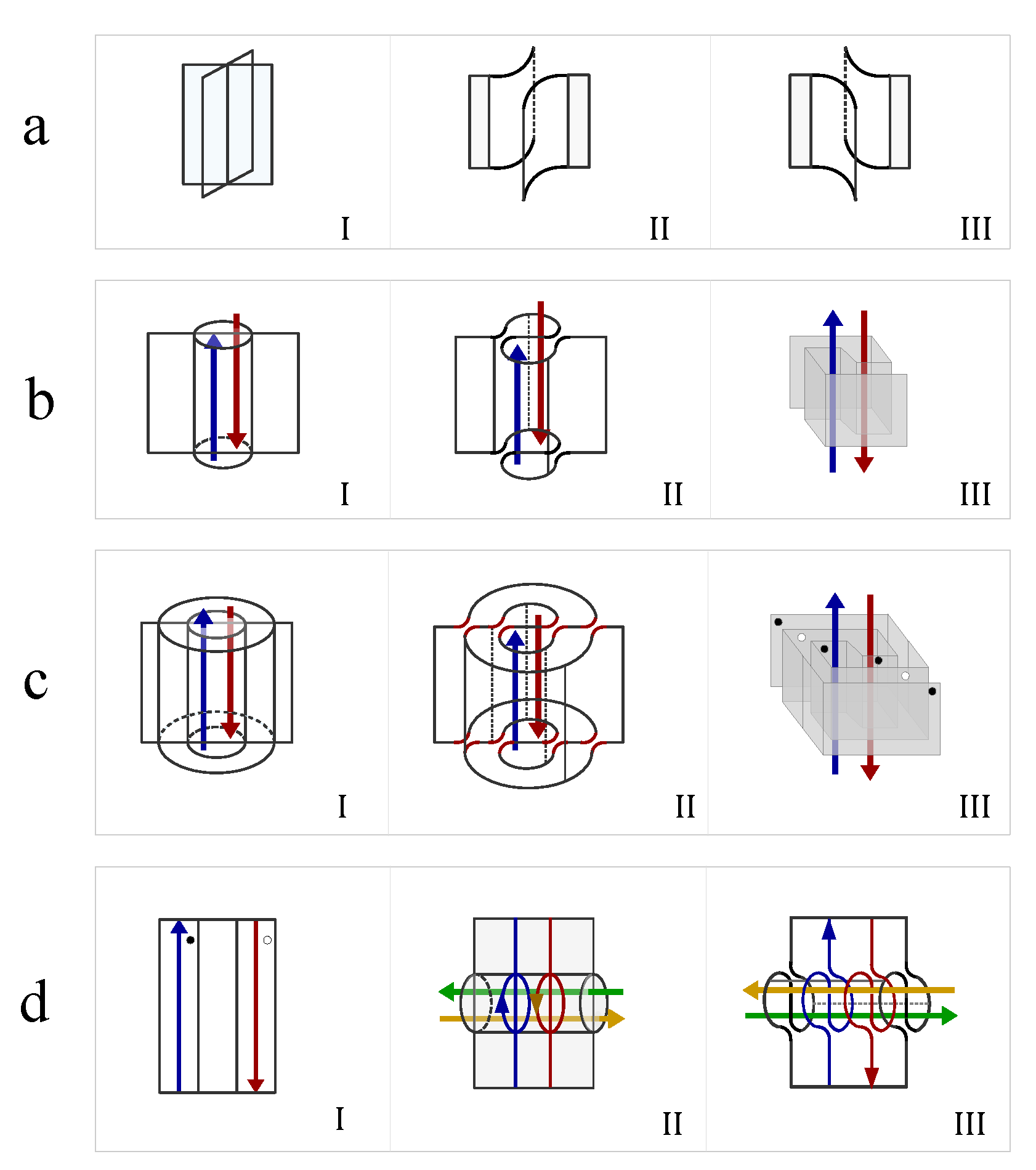

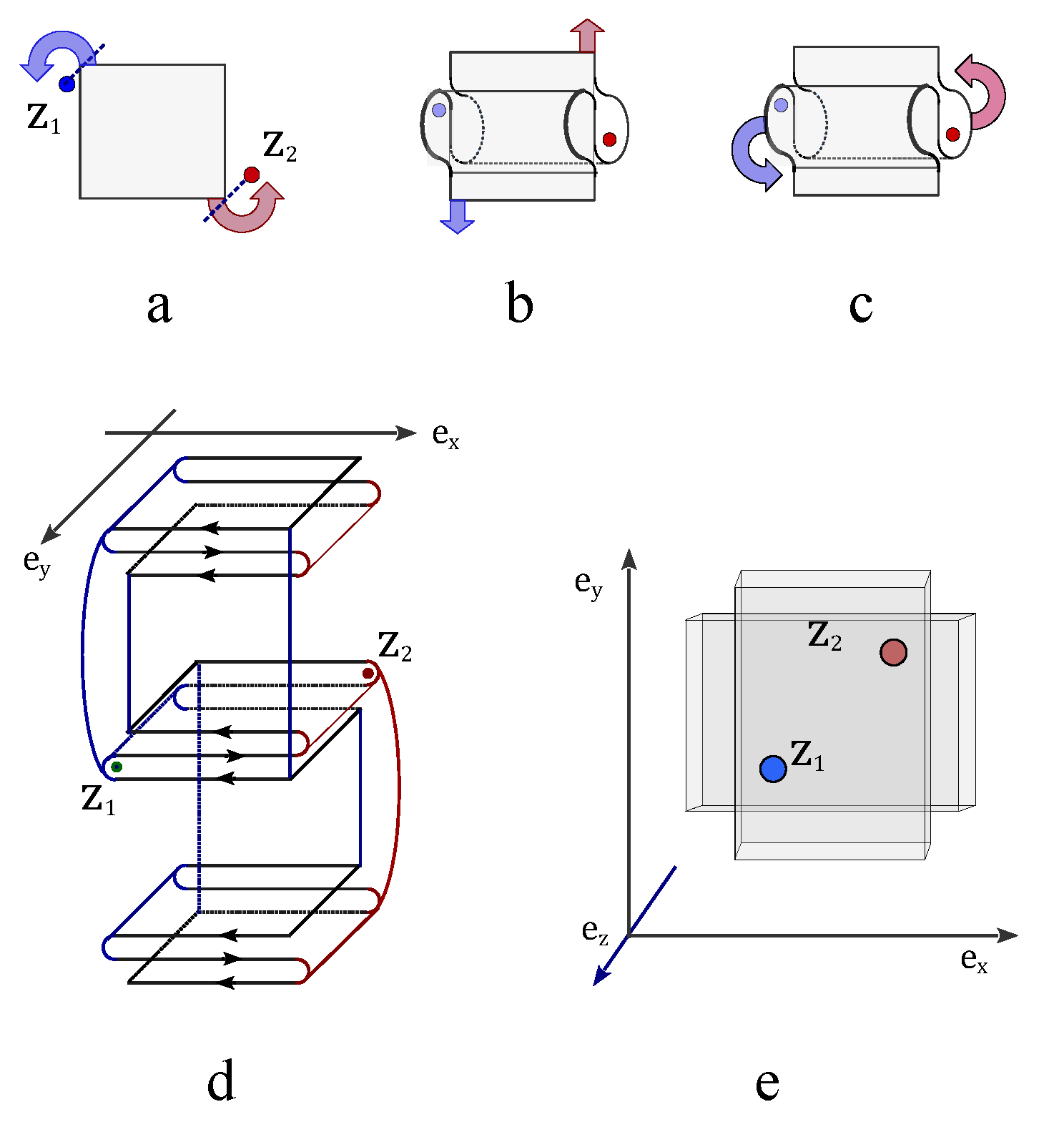

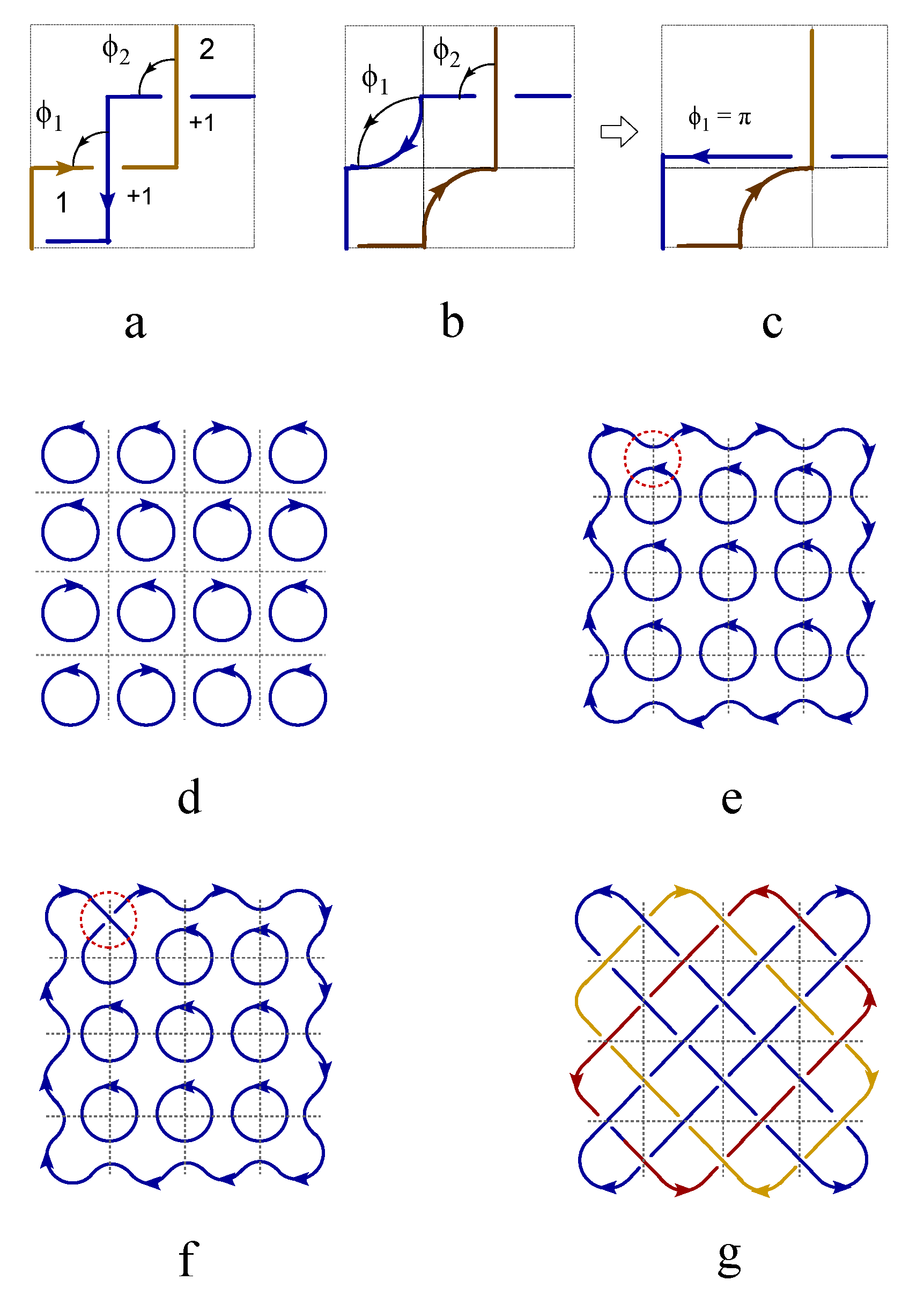

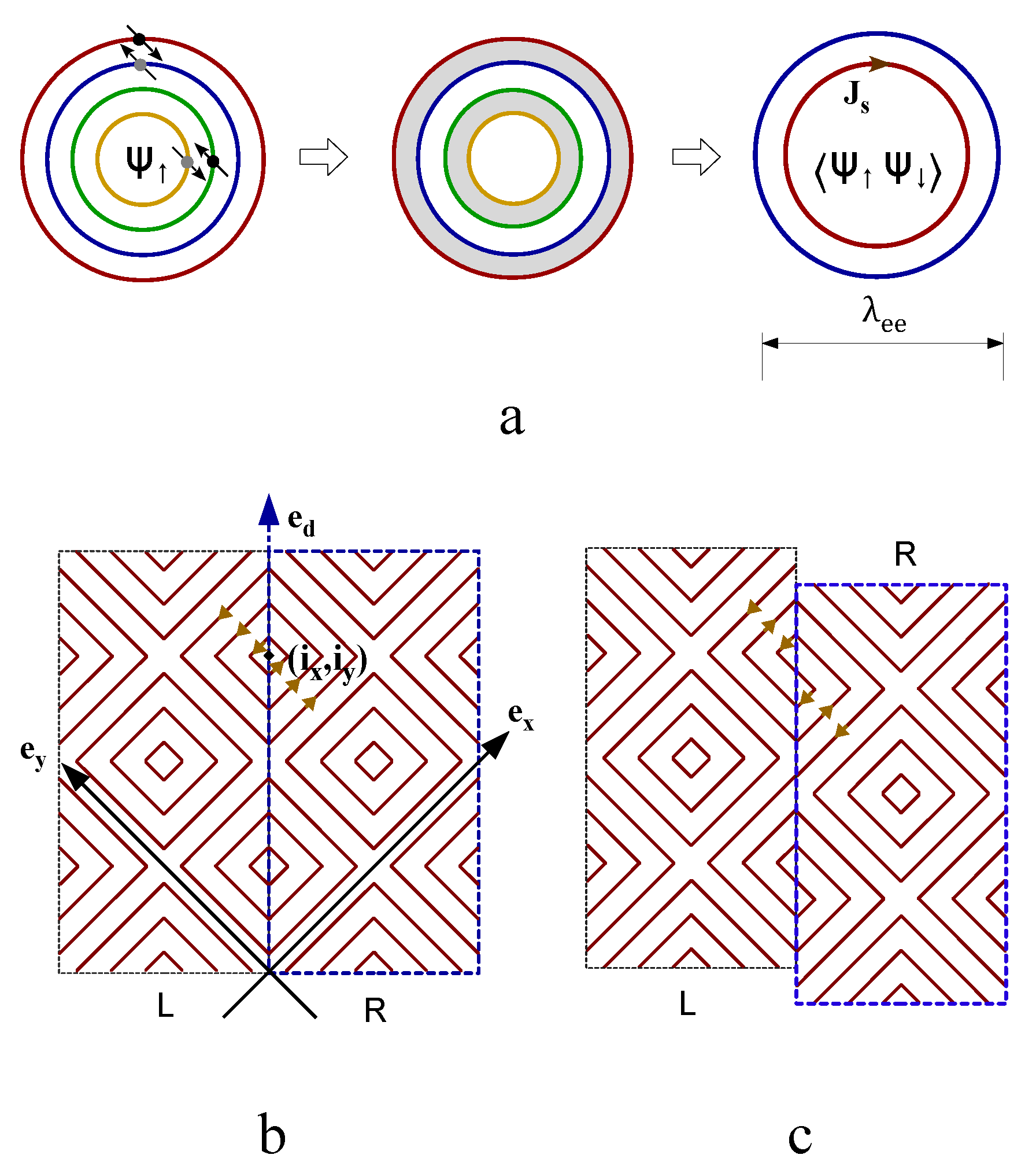

Figure 1a shows two topological defect on the north pole and south pole of the spherical droplet. The spherical droplet deforms into a solid torus when the line defect penetrate through the north pole, south pole and the mass center. A moving particle going around the topological line defect twice provides an effective representation of spinor wavefunction for

(

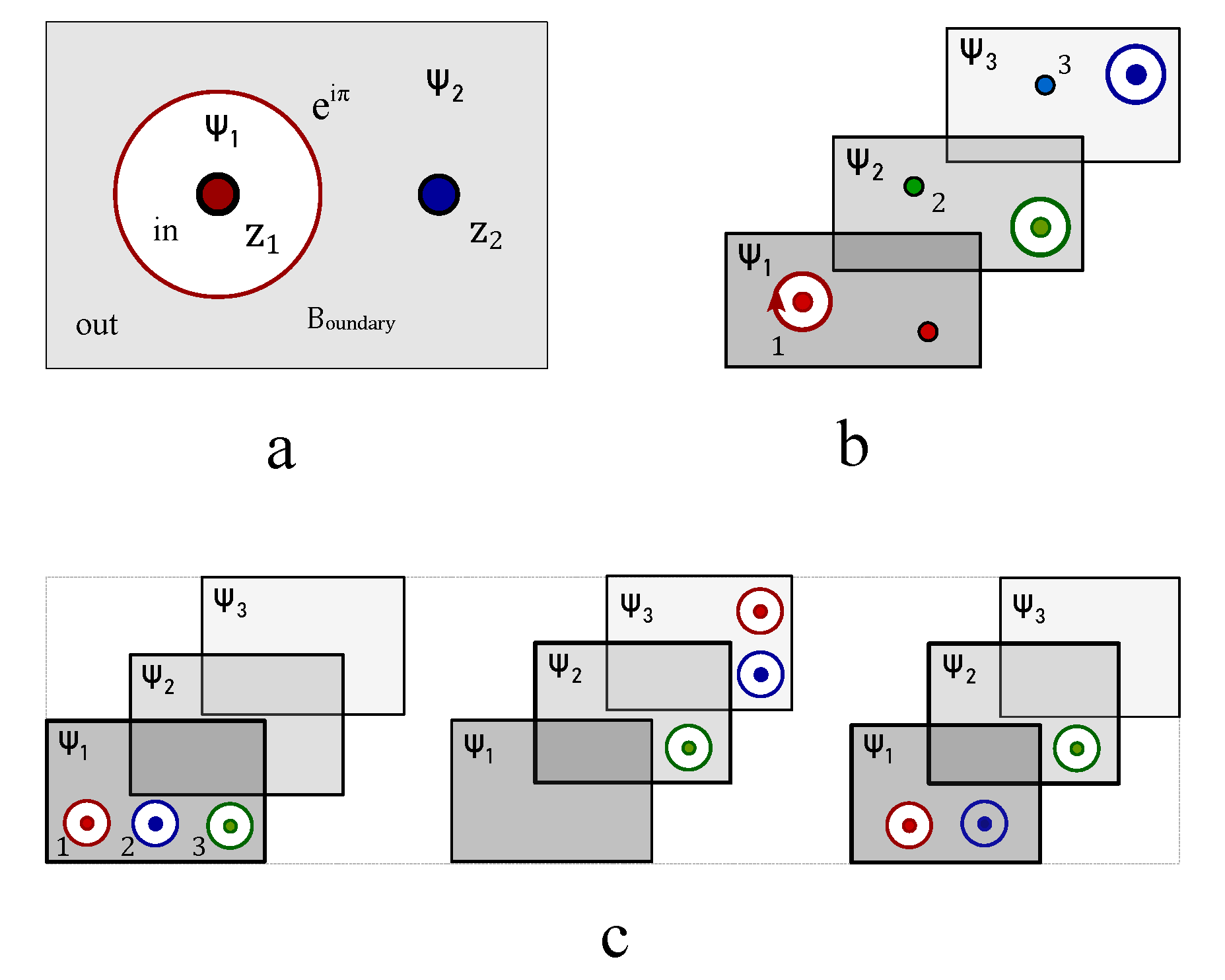

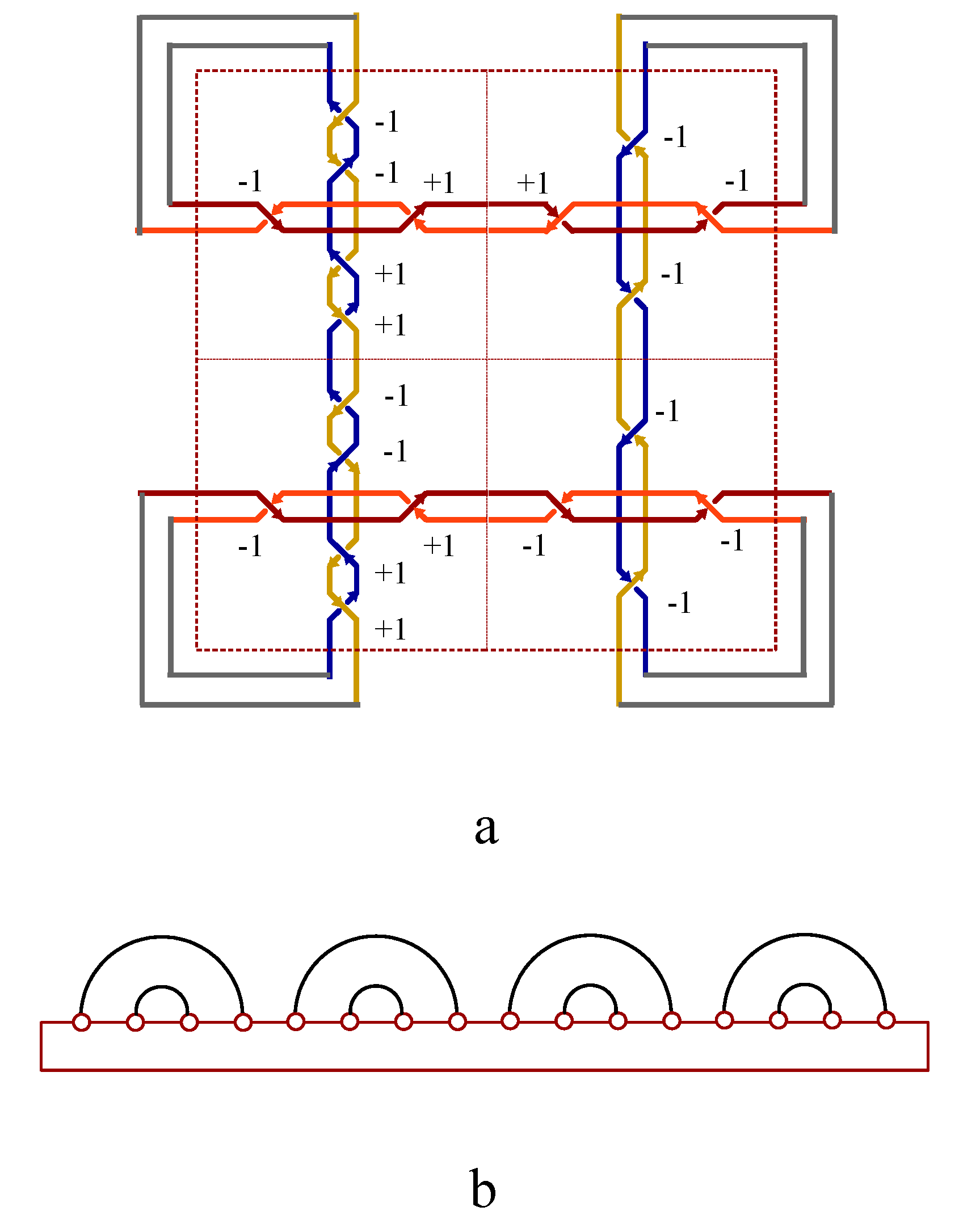

Figure 2a),

An equivalent topological deformation of solid torus is M

bius strip. The edge of the M

bius strip locates along the extremal points of Bohm potential. An electron winds around the topological line defect

to form a closed path in

Figure 2a. The periodicity of the other phase factor

is still

. The eigenvalues of the spin operator are

, which represents the chirality of flowing current in M

bius strip.

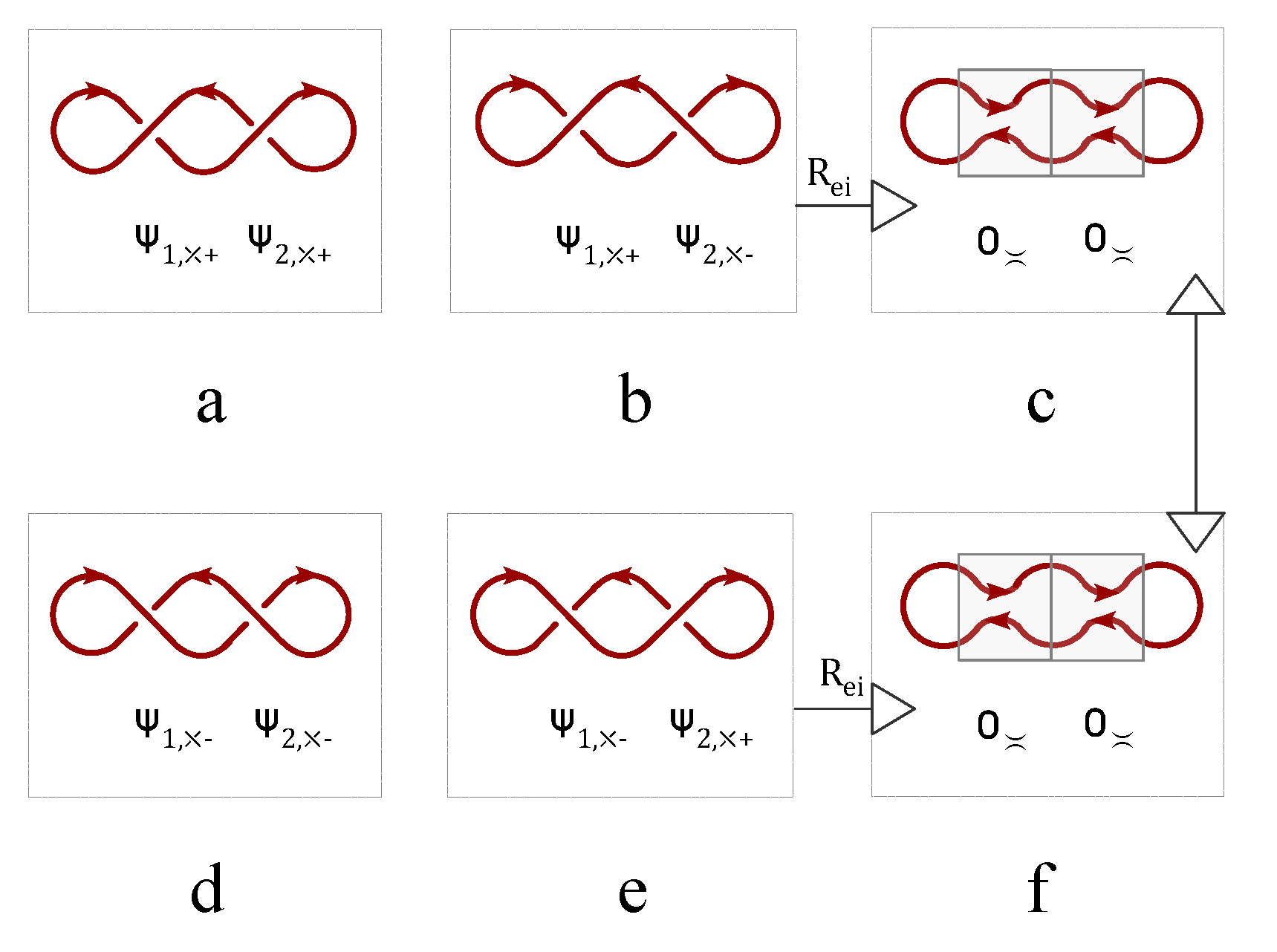

Unfolding the edge of M

bius strip into an

∞-shaped knot preserves the topology of quantum fluid torus and the

periodicity of spinor wavefunction. The

Figure 2a represents the wavefunction of topological spin state

, which defines a topological representation of electron spin

. The spin states of

∞-shaped knot crossing,

and

, are represented by complex wavefunctions with four components,

It must be pointed out that magnitude of wave function for knot crossing is not normalized to unity, instead it is normalized by Jones polynomial,

.

Figure 2b (

Figure 2c) represents the two components of wavefunction for topological spin state with

(

). The tangential velocity of circling fluid in the knots of

Figure 2b-c is determined by the gradient of phase field of wavefunction. Opposite gradient fields generate opposite tangential flow fields. A crossing state in

Figure 2a-b transforms into uncrossing state in two different ways, as showed in

Figure 2d-e. The uncrossing states are topological vacuum states, denoted by

and

,

Both the topological crossing basis and vacuum basis are not normalized and orthogonal, but a set of orthogonal basis always exists to expand the two sets of topological basis into the same Hilbert space,

The conventional Jones polynomial are projected into the orthogonal basis

. The eigenvalue of topological spin with respect to vacuum states is zero,

or

. Once the two currents are oriented to form the horizontal vacuum state

, the vertical vacuum state

is forbidden under continuity constraint of topological invariant. The magnitude polynomial of the topological spin states transform into one another following Kauffman decomposition rule in knot theory[

18],

which are further reformulated into matrix equation,

Substituting the orthogonal Eq. (

9) of topological vacuum states into the decomposition Eq. (

12) yields the transformation equation between the crossing basis

and uncrossing basis

,

The basis transformation equation an unitary matrix, which is expanded by the generators of SU(2) group,

where the crossing state vector

and uncrossing state vector

are denoted as

Both the crossing state and uncrossing state have four open endings. In order to form closed path that is topologically equivalent to circles, edge states with two open endings are introduced as following.

where

,

represents the left, the right, the top and the bottom edges respectively. The topological edge state of single current branch locates along the edge of knot lattice. Once the edge current configuration is fixed, its collective configuration remains invariant when the bulk knot lattice transform from the crossing basis to the uncrossing basis. The product of two edge states of opposite semicircles,

or

, are defined as closed vacuum state

. The closed vacuum state can be represented by unit matrix. The simplest representation of

is U(1) group element,

In knot theory [

18], the polynomial with respect to the combination of a closed loop and general link is defined as

This decomposition rule is derived from two coupled crossings, that decomposes according to Eq. (

11).

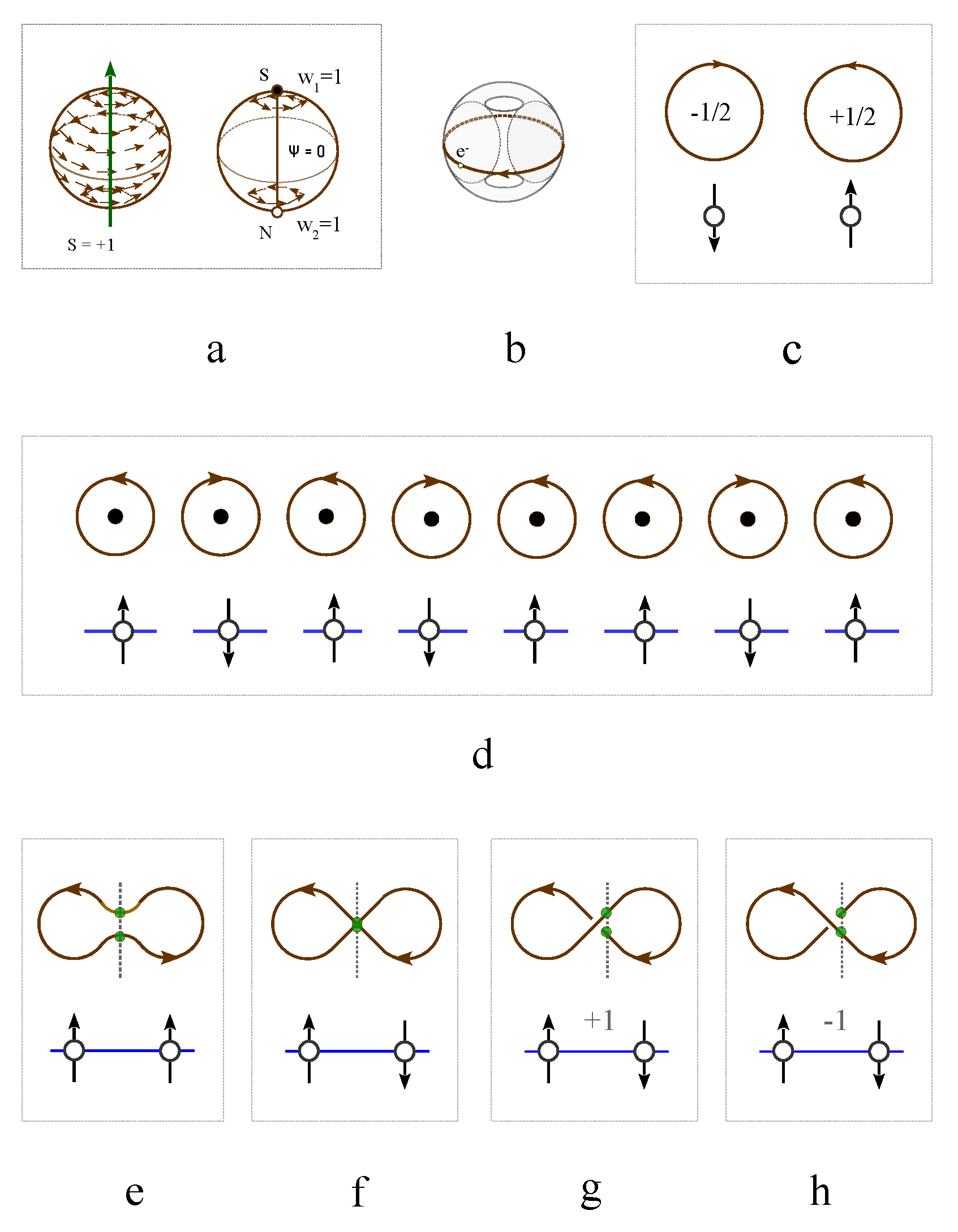

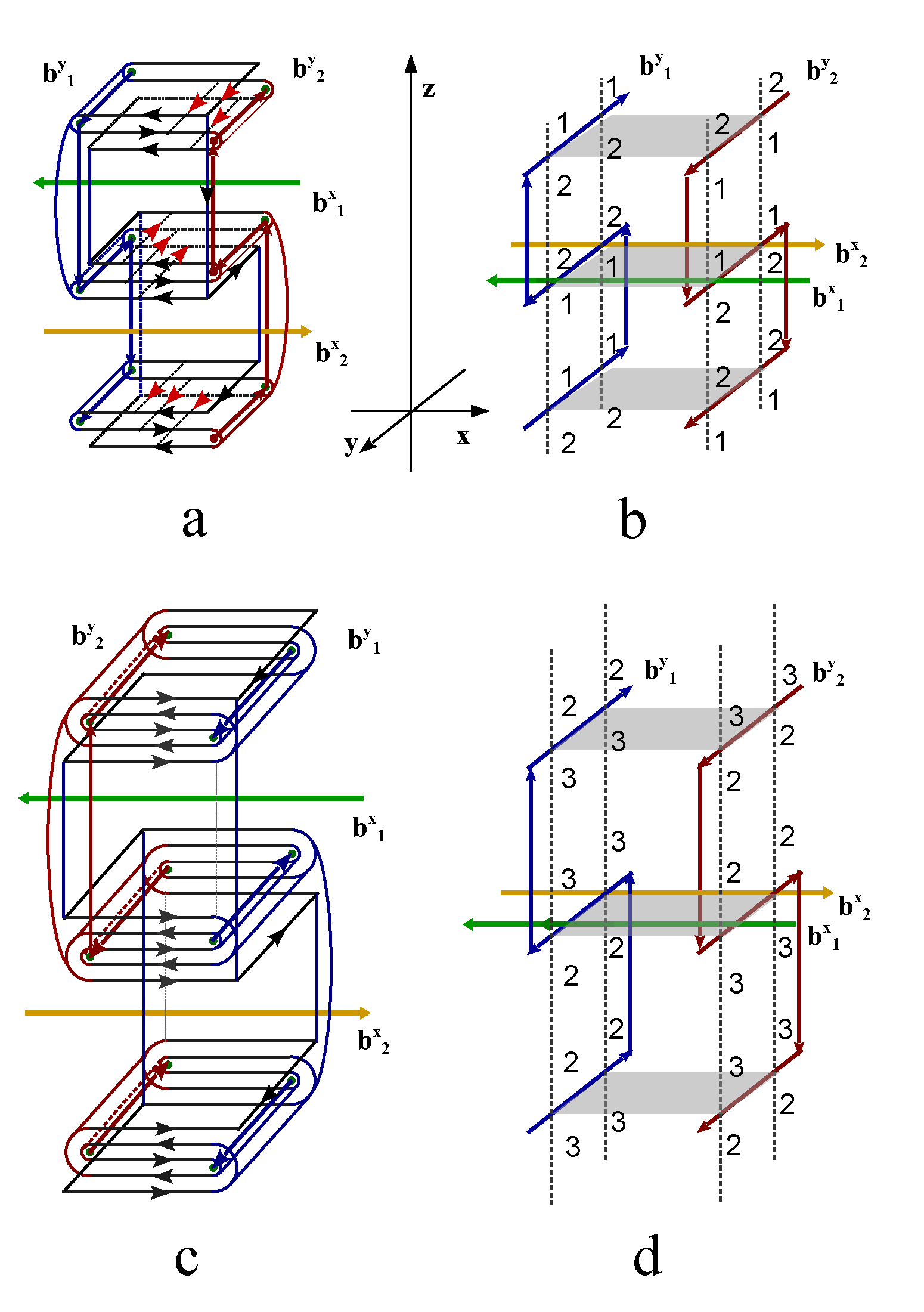

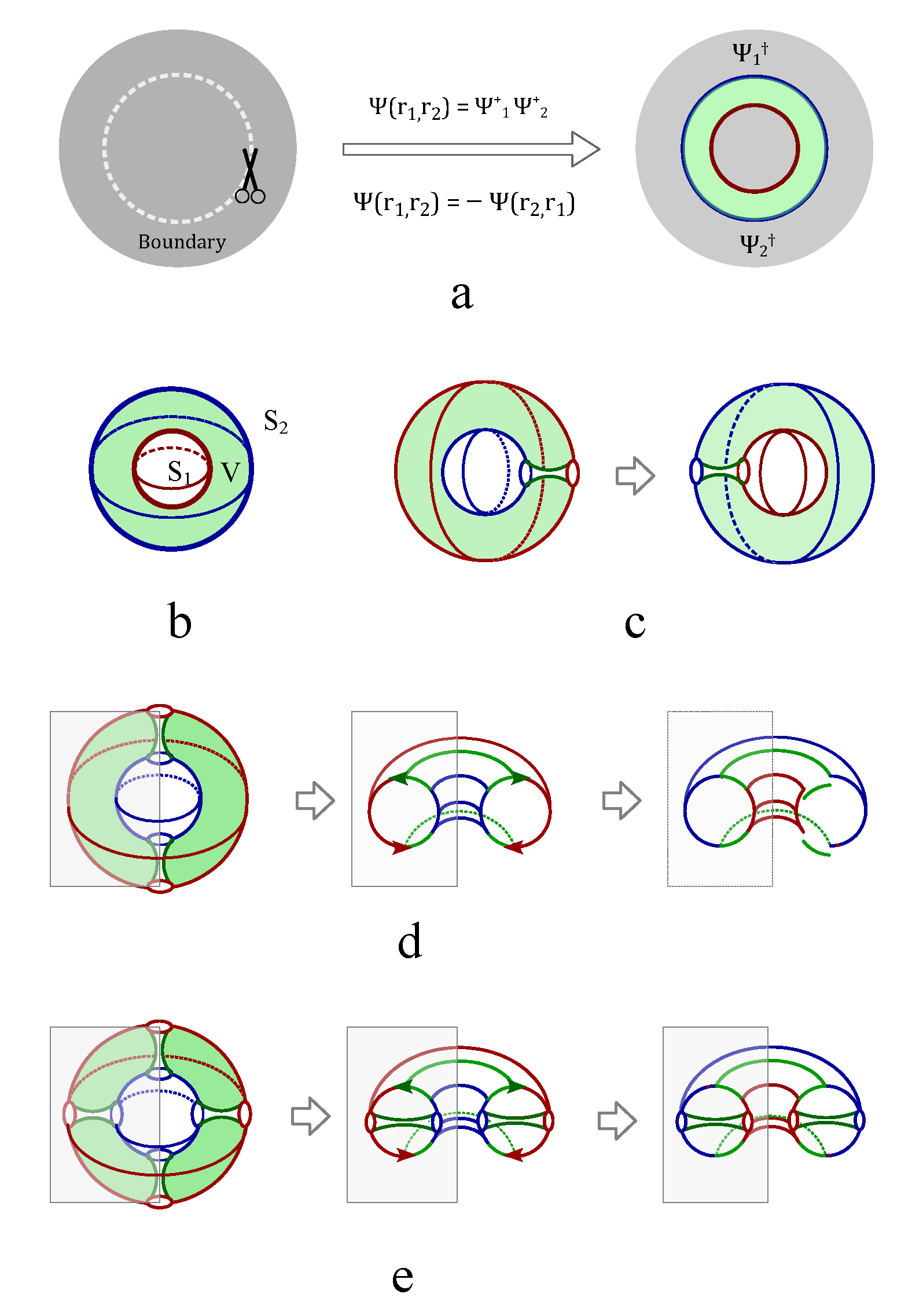

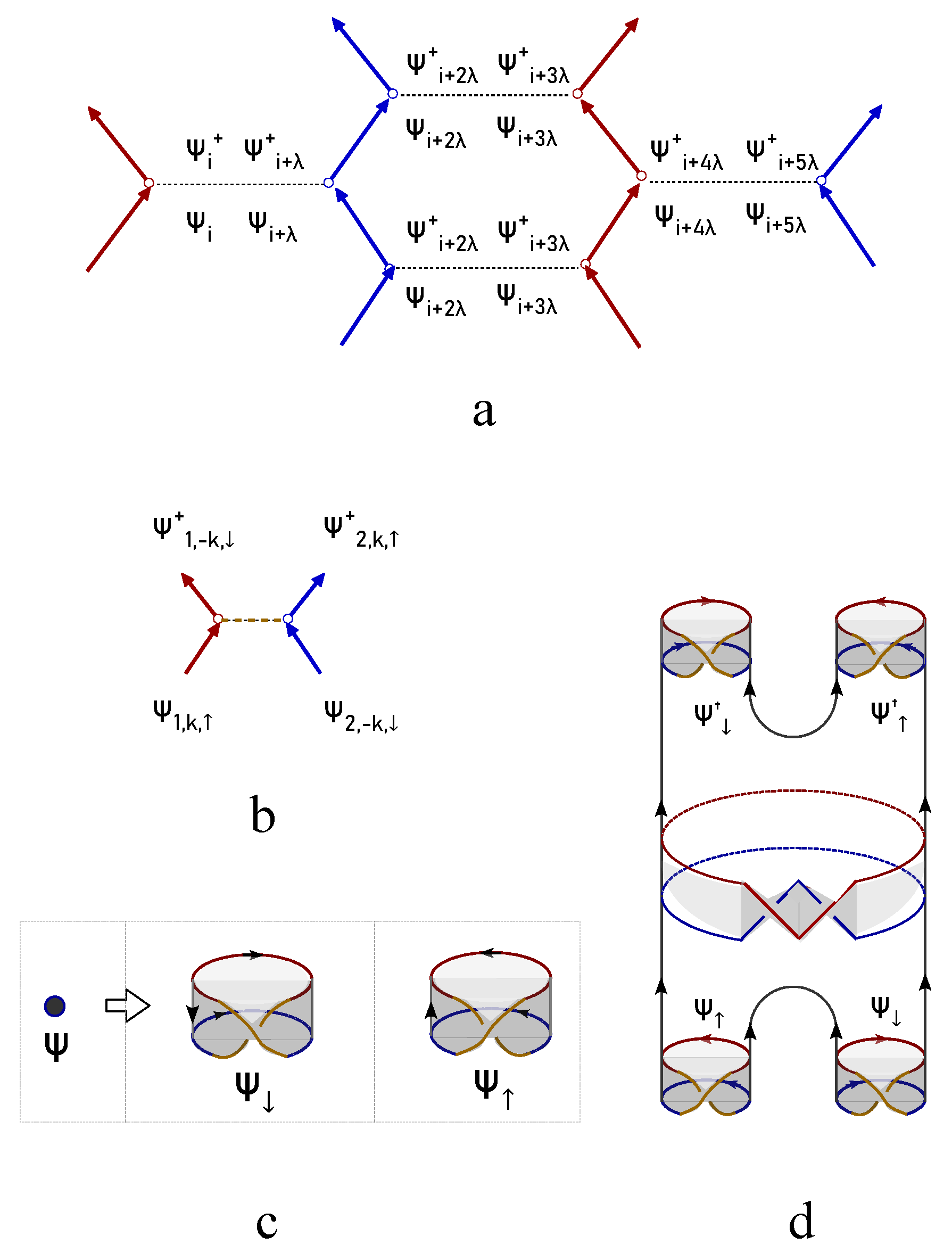

Two coupled crossings with independent topological spin numbers generate four possible crossing states,

,

,

and

as shown in

Figure 3. Unlike the four independent basis of two coupled spins in quantum mechanics, the two crossings with opposite topological spin are transformed into the same product state of two vacuum states under Reidemeister moves,

where

is the operator of the Reidemeister move. As showed in

Figure 3b-c and

Figure 3e-f. Applying the Kauffman decomposition rules for the four crossing basis transforms them into four vacuum basis of two coupled spins,

In mind of the orthogonal relations between different basis, i.e.,

,

,

, the transformation matrix of knot polynomial is mapped into the transformation matrix between the two four dimensional basis vectors,

The polynomial vector of

N coupled crossings

transforms into

N coupled uncrossings

following the same decomposition rules as above,

. The transformation matrix

U is a matrix of Kauffman polynomial, which is equivalent to Jones polynomial.

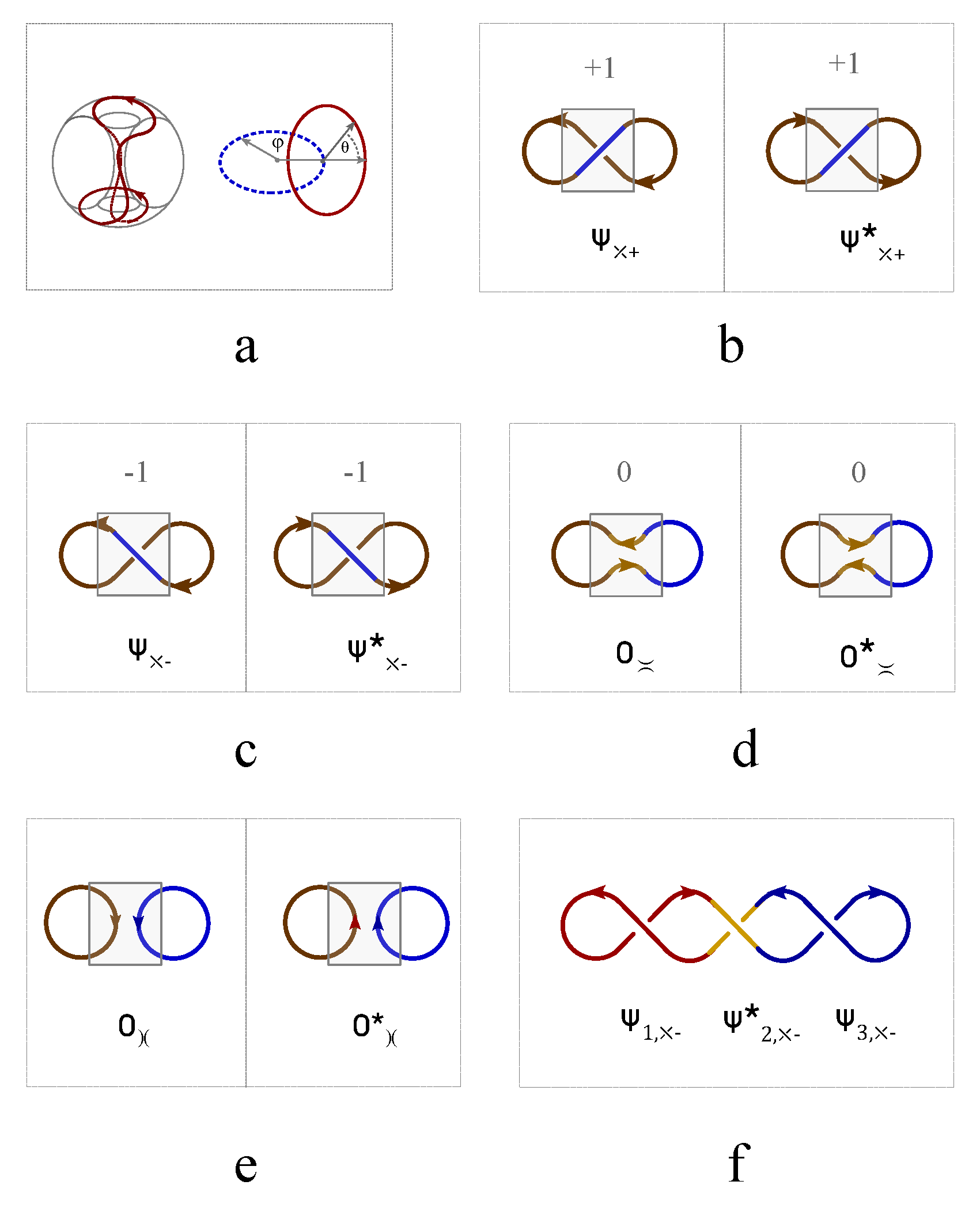

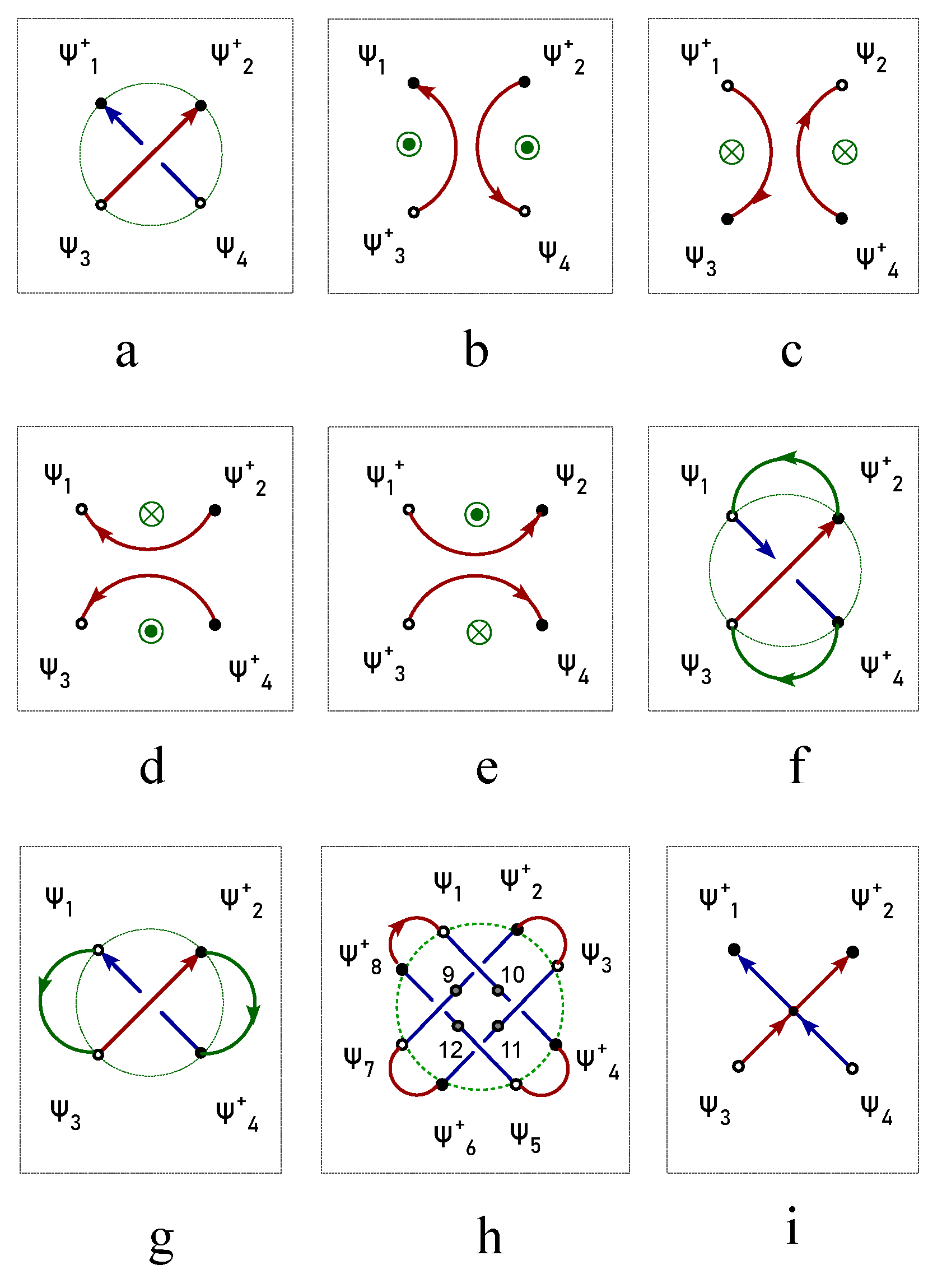

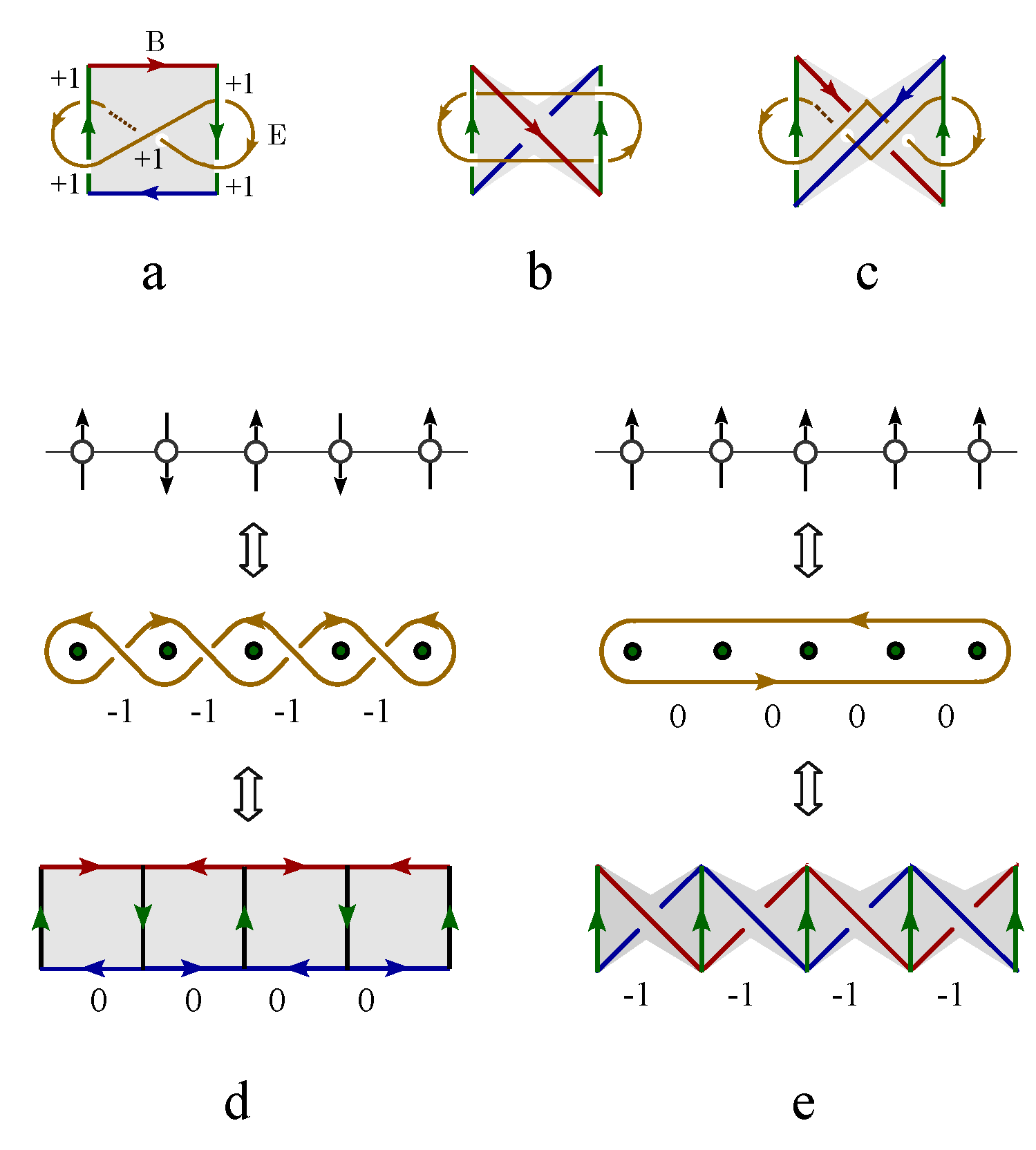

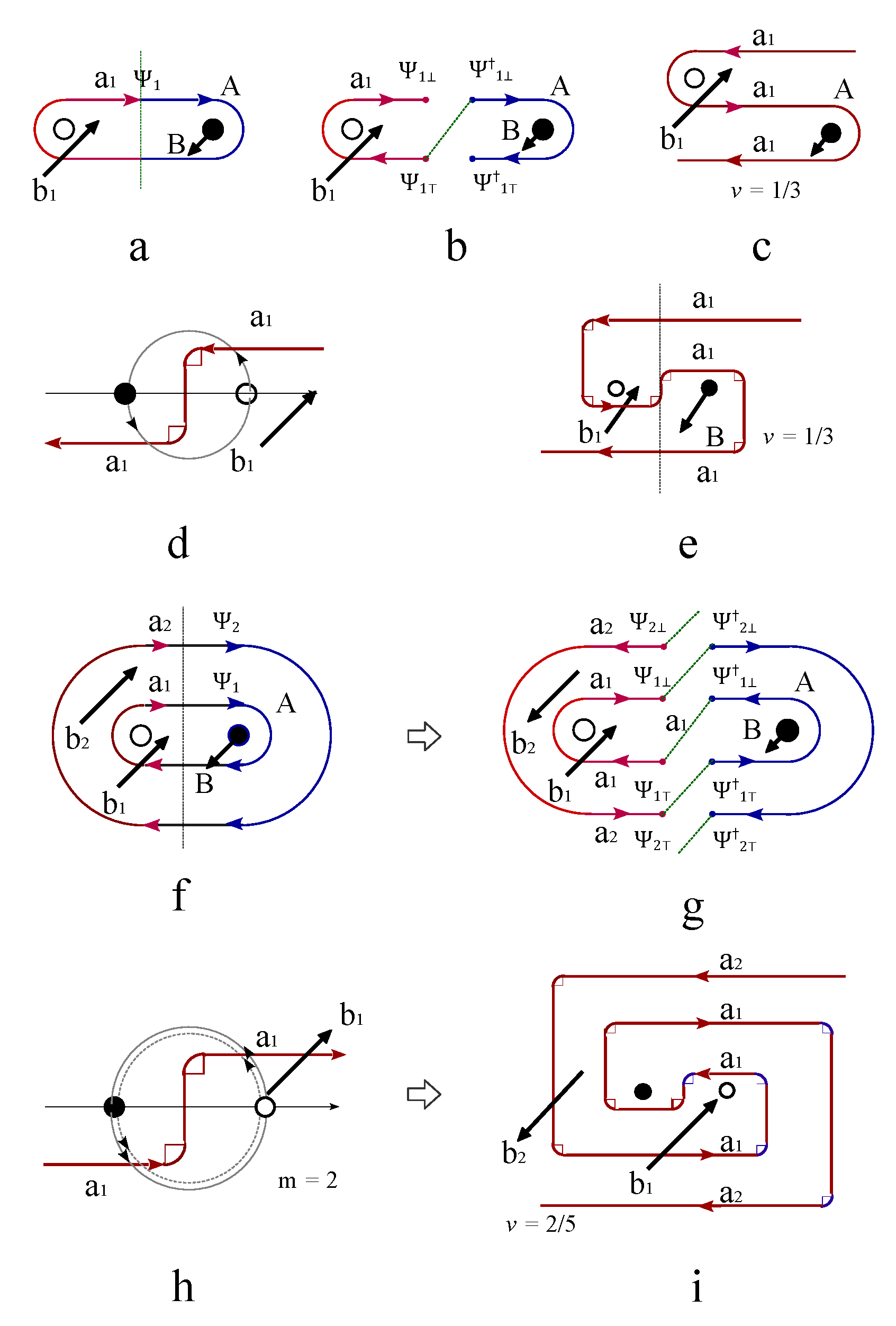

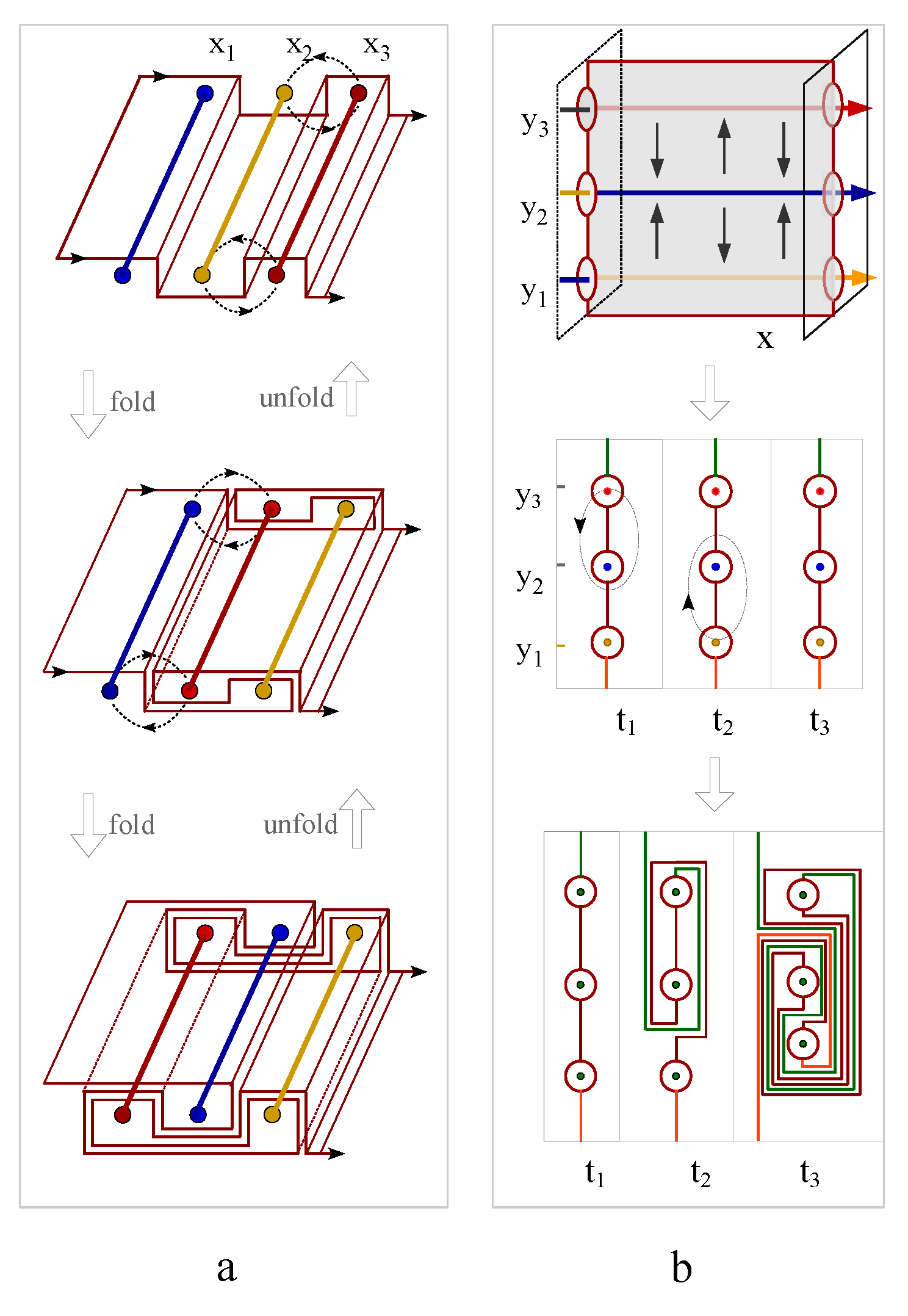

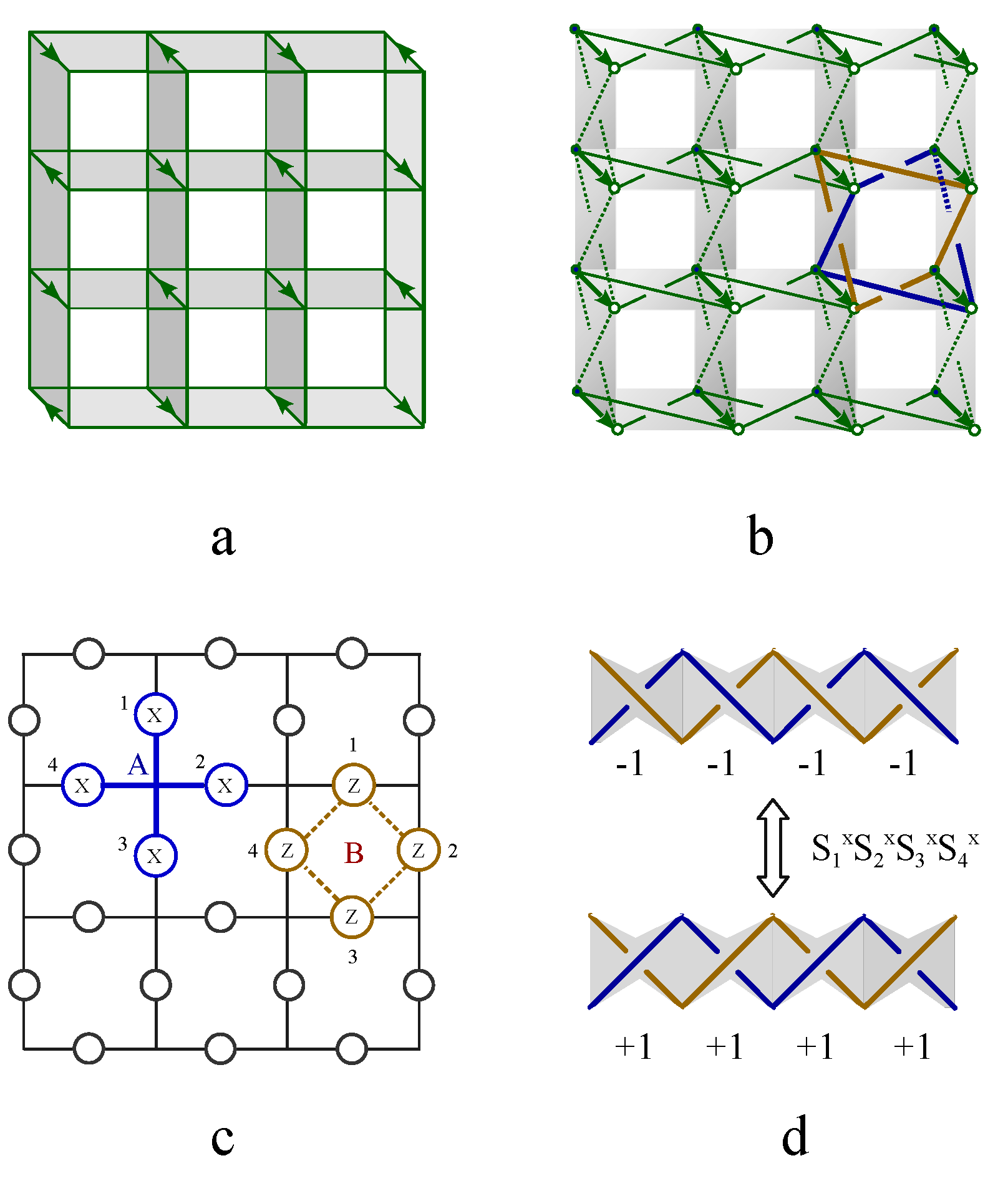

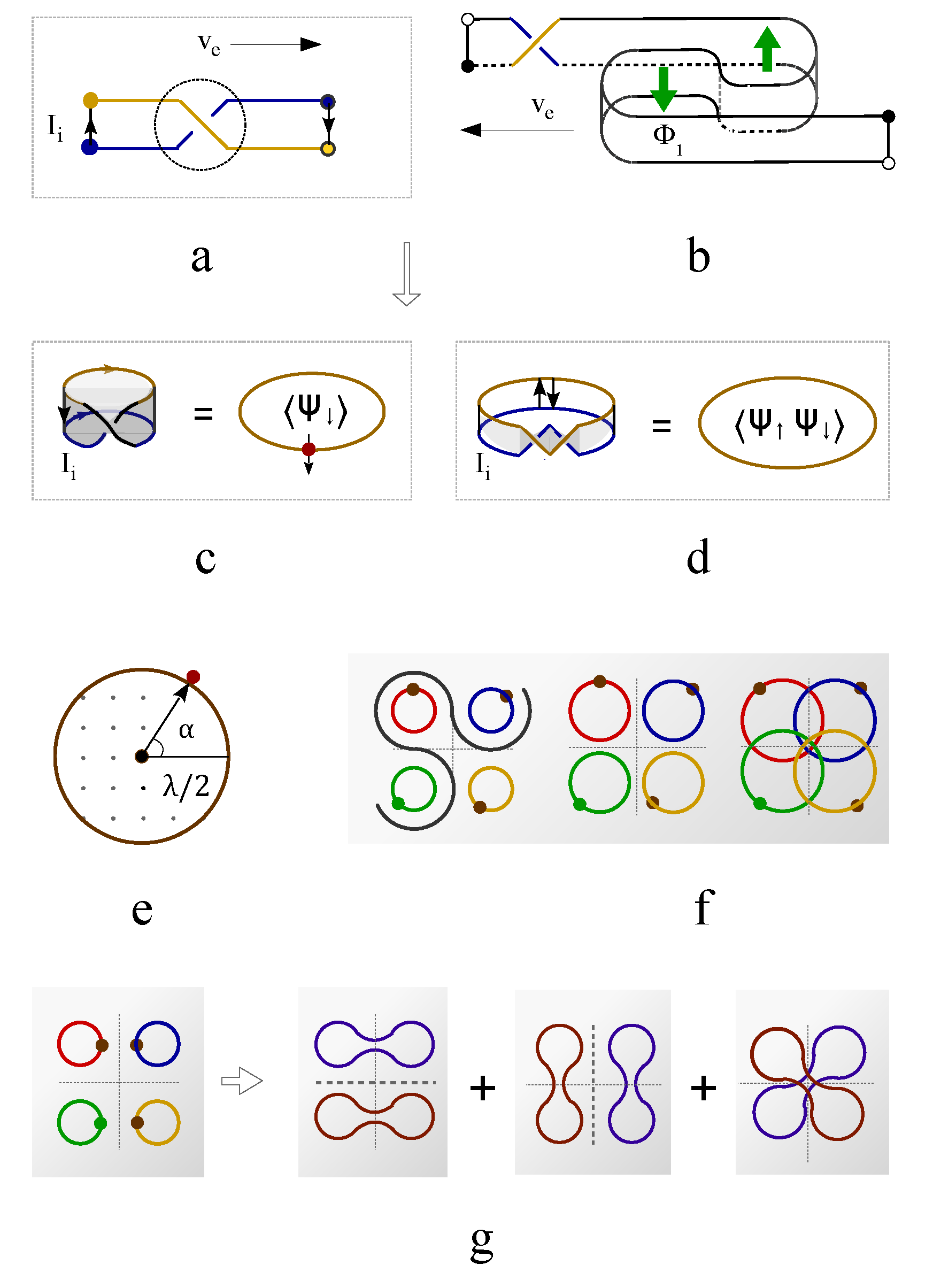

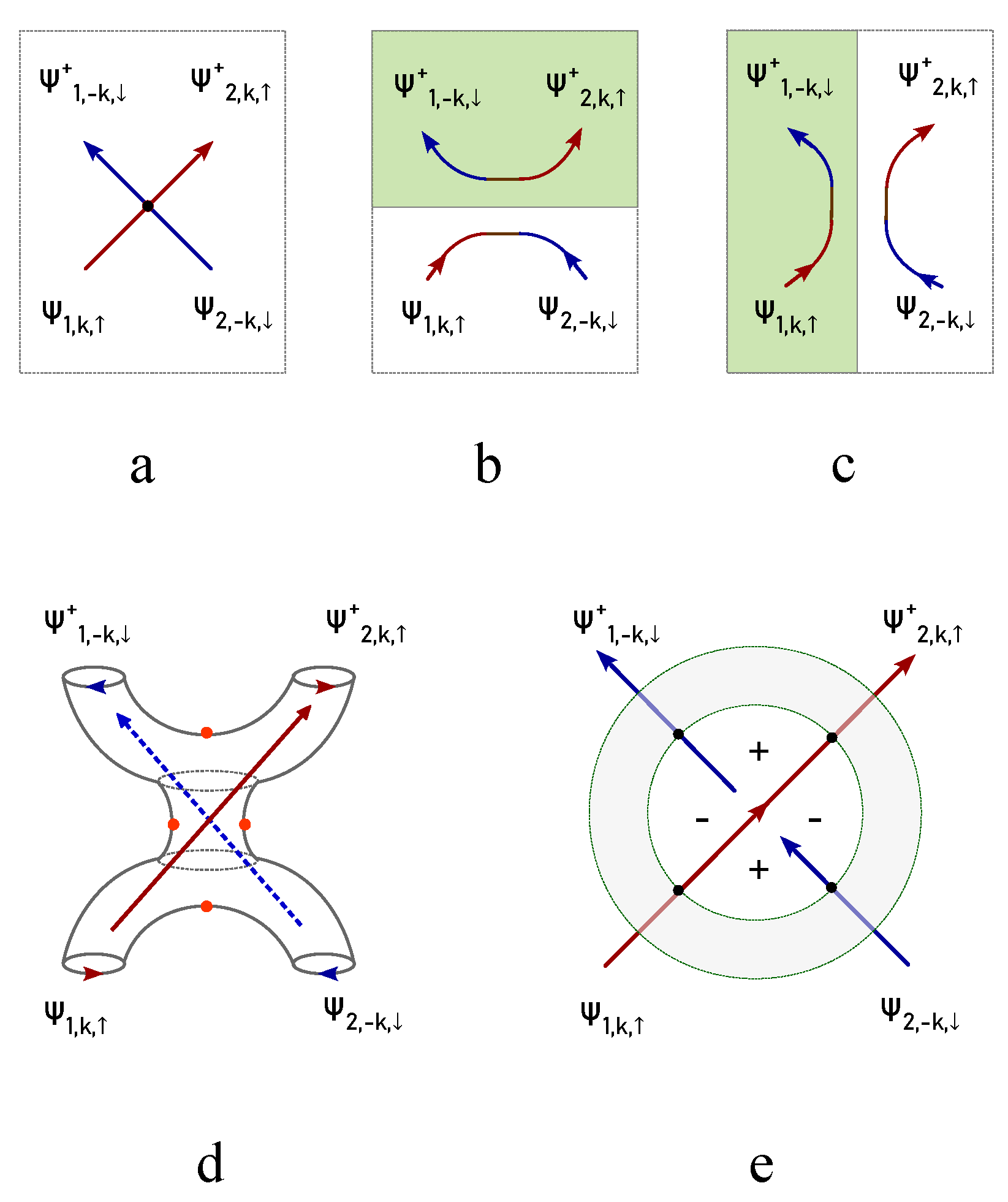

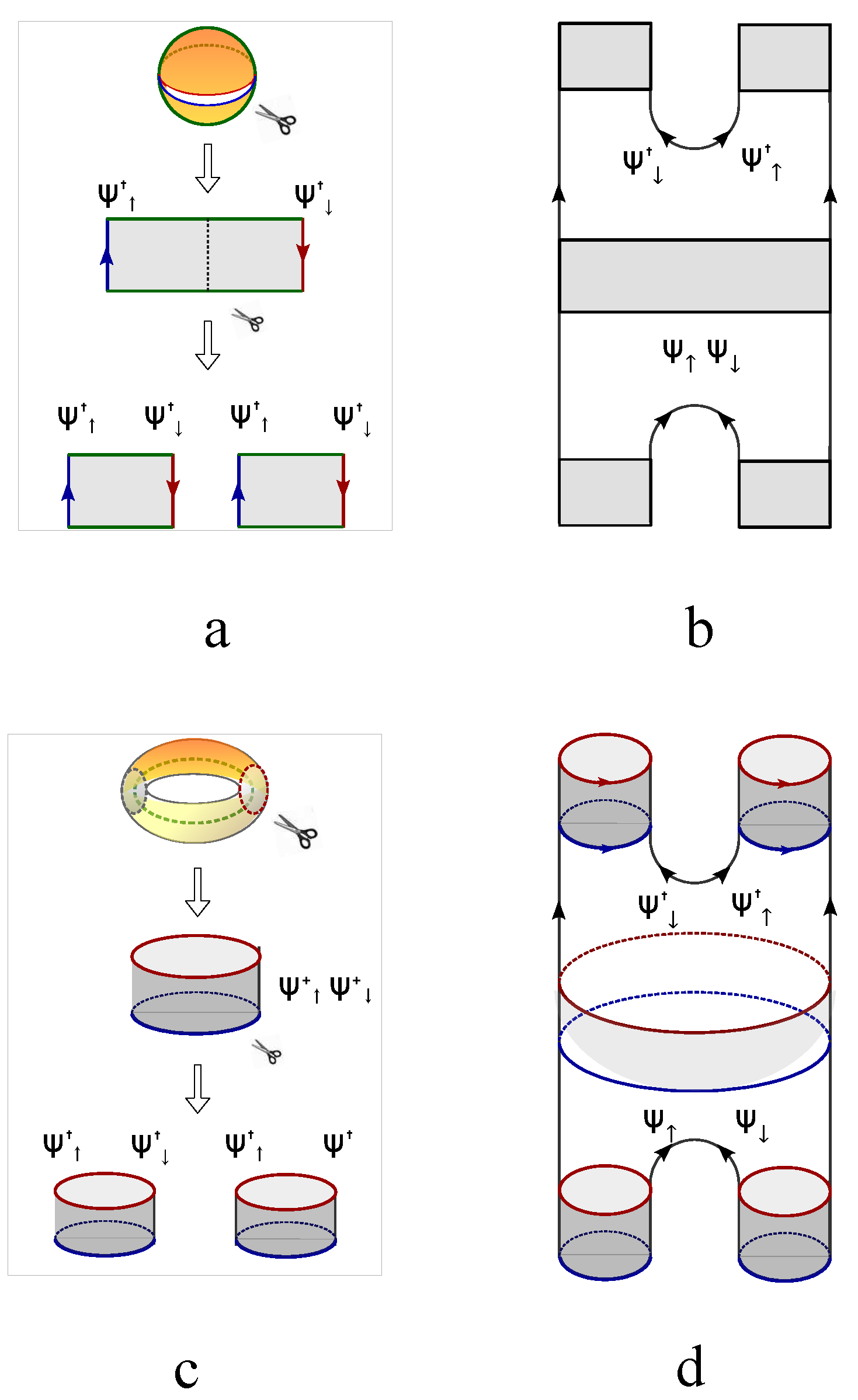

Beside the quantum wavefunction representation of knot, the knot lattice has a straight forward representation by matrix of quantum creation and annihilation operators. Cutting one cross out of its surrounding network generates four open endings in

Figure 4a. The directed flow along the current line is represented by the product of a creation operator and an annihilation operator, i.e.,

and

. The crossing in

Figure 4a is represented by a matrix equation,

where

h is the hopping rate.

is fermion operator and obeys anticommutative relations,

The hopping rate in Eq. (

22) is multiplied by a topological phase term

, where the topological spin is quantified by

where

is the gauge field potential along the current lines. The two crossing current lines that avoid touching each other always bend into opposite directions, since the four ending points are projected into the same plane. When the topological spin

flips to

by exchange the top and bottom lines, the divergence field

or

flips its orientation respectively. The topological spin Eq. (

24) is essentially the abelian Chern-Simons action,

defined on a local crossing. The quadratic fermion operator Eq. (

22) is equivalent to Hamiltonian equation with

t measures the kinetic energy of a hopping particle. Therefore the representation matrix

is termed as topological Hamiltonian matrix here. The topological vacuum state for two uncrossing current lines in

Figure 4b is also represented by four fermion operators which interact with one another following the Hamiltonian equation

,

Since the two current lines in vacuum state avoid crossing each other, the topological spin is defined by the product of the divergence field of the two arc lines,

The divergence of the two arcs in

Figure 4b are oriented in the same direction, denoted by the black dot surrounded by a circle, therefore the eigenvalue of topological spin is

. The topological spin Eq. (

27) for vacuum states shares similar definition with the second Chern number in four dimensional manifold,

The conjugate of

is represented by the same two arcs in

Figure 4c, in which both the flow field and divergence field of the two arcs are reversed simultaneously to preserve the value of topological spin

. When the two arcs in vacuum state generate opposite divergence fields, the topological spin of vacuum state is

. For example, the

Figure 4d is composed of two arcs with opposite divergence, the topological spin in the Hamiltonian matrix,

is

, which is invariant in the conjugate vacuum state

, because both the two opposite divergence fields reversed their orientations (

Figure 4e).

The open endings are connected by edge currents to form a closed loop. In the quantum operator representation of knot, the edge current are also the product of a creation and an annihilation operator. The Hamiltonian matrix of the "8"-shaped knot in

Figure 4f reads

where

is the hopping rate of edge current. A

∞-shaped knot is generated by adding the other two edge states,

and

, on the cross in

Figure 4a. The corresponding Hamiltonian matrix is

The

∞-shaped knot and "8"-shaped knot share the same topology but are distinguishable by the Hamiltonian matrix. This Hamiltonian matrix representation of knot lattice has a straight forward extension to more complex knot lattice. For example, the chiral flow in the knot lattice of

Figure 4h is described by the chiral Hamiltonian matrix

where

is the complex hopping rate. This topological Hamiltonian representation spontaneously eliminated the intersecting current lines out of knot lattice (

Figure 4i), where the product terms of four fermion operators emerges. The dimension of the Hamiltonian matrix of a knot lattice is determined by the total number of nontrivial endings. Each ending represents one fermion particle. This quantum representation provides a natural explanation on the assumption in knot theory, i.e,

. The collective quantum state of a trivial circle composed of

N endings is denoted as

where

is the occupation number on the

ith ending. The Hamiltonian matrix representation of the circle is

dimensional diagonal matrix. The knot polynomial is derived from determinant of the Hamiltonian matrix,

If the occupation number at any one ending points is zero, the track chain remains open, the polynomial equation of circle is spontaneously zero.

The topological Hamiltonian

for a knot lattice is independent of dynamics of interacting crossings. Interacting crossings in knot lattice is described by dynamic Hamiltonian. When the crossing states transform into another crossing states under thermal fluctuation or external field stimuli, the knot lattice is in superposition state of different crossing patterns. For the simplest superposition state of single crossing with opposite topological spin

, the wavefunction is denoted as

, the density matrix is defined as

counts the probability of the cross in the state with topological spin

.

counts the probability of the cross state with

.

or

counts transition rate between the two opposite crossing states. The density matrix obeys the Heisenberg equation of motion,

A general Hamiltonian for the crossing transition dynamics is

measures the reversing frequency of the chiral current in knot.

measures the hopping strength between opposite crossing states. Notice here the Hamiltonian and density operator are expressed by the same basis. If the density operator is expressed by superposition state of topological vacuum basis

The density matrix in the vacuum space is an unitary transformation of the density matrix in the crossing space,

The vacuum state

is transformed into topological crossing state according to the inverse of Eq. (

14),

. The dynamic Hamiltonian Eq. (

37) in the crossing basis also has an equivalent expression in the vacuum basis,

The dynamic Hamiltonian Eq. (

40) is self-consistently applicable on a density matrix originally expressed by topological vacuum states. If the quantum system is a hybrid four level system of two crossing states and two vacuum states, the corresponding dynamic Hamiltonian is expressed by both the crossing basis and the vacuum basis,

The topological invariant polynomial maps the vacuum basis to the crossing basis, providing a topological constraint equation on the hopping process between vacuum state and crossing state. The dynamic hopping in non-topological electron fluid is governed by quantum electrodynamics. The hopping process between different energy levels of topological fluid must take the knot invariant into account.

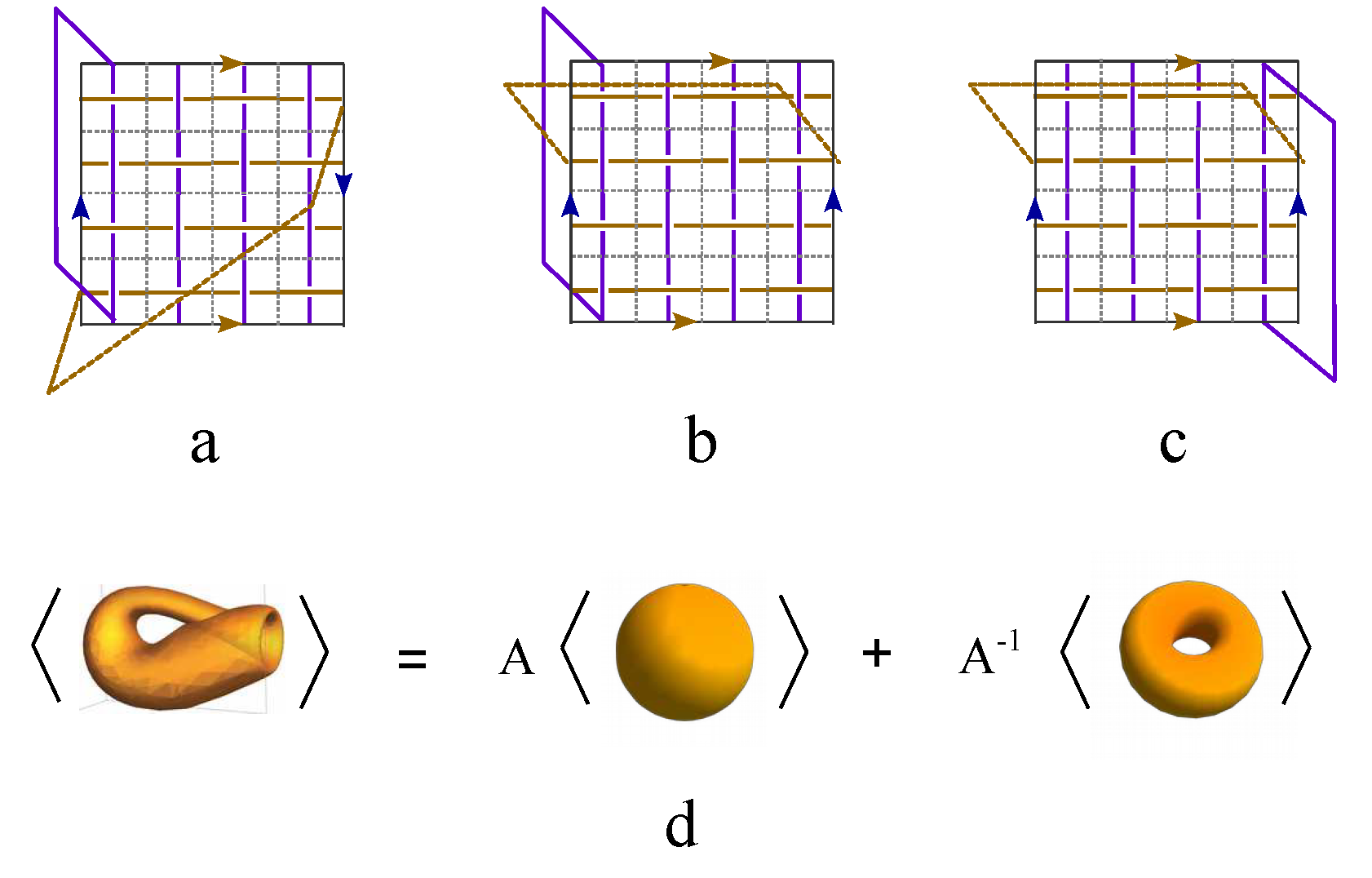

The Kauffman polynomial of knot lattice

is equivalently mapped into Jones polynomial

by multiplying

with

the writhing number, i.e.,

. The Jones polynomial is equivalent to an evolution operator that maps the initial crossing states of linked knot lattice into all possible full loop states with inequivalent topology,

where

denotes the

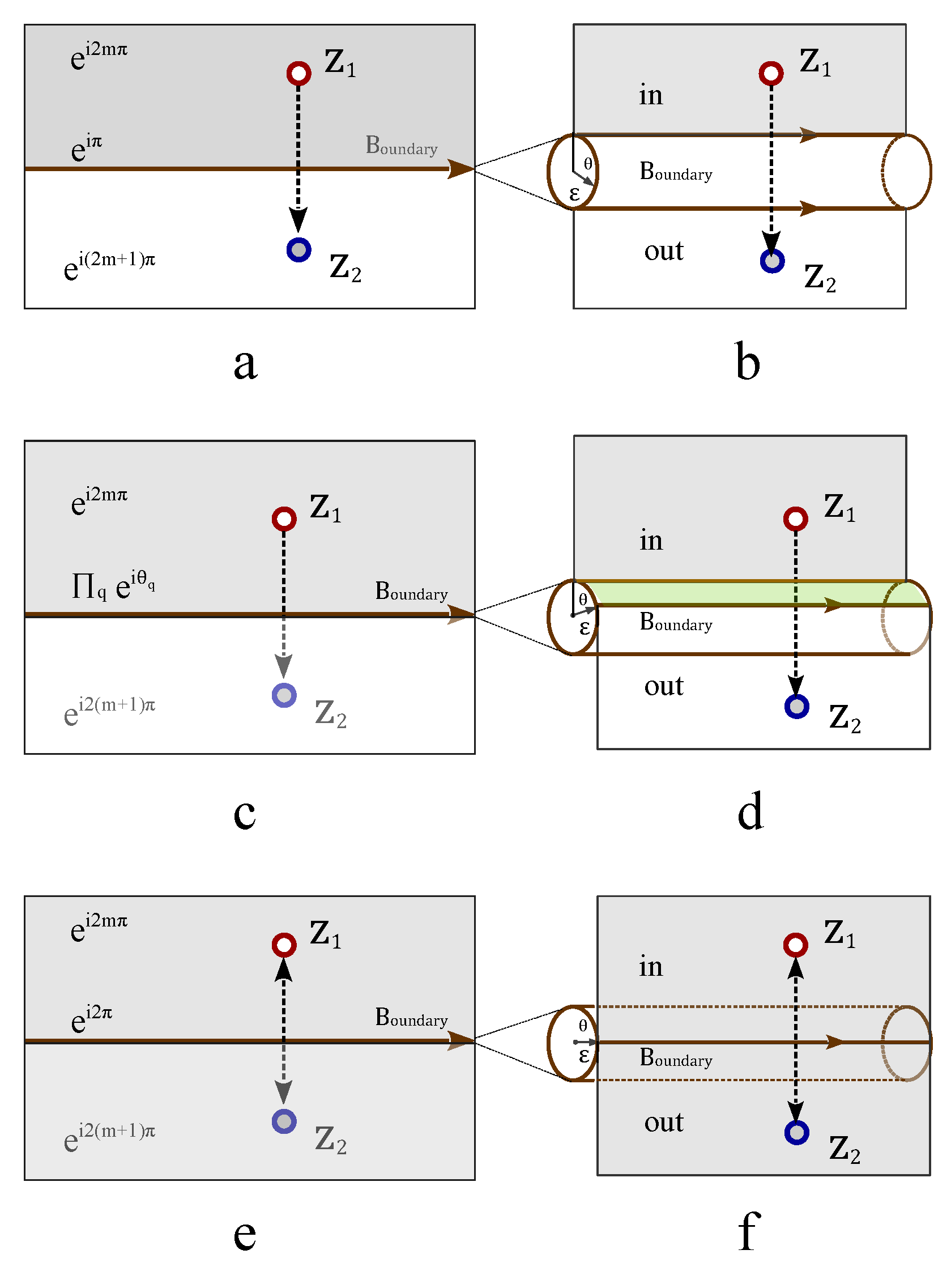

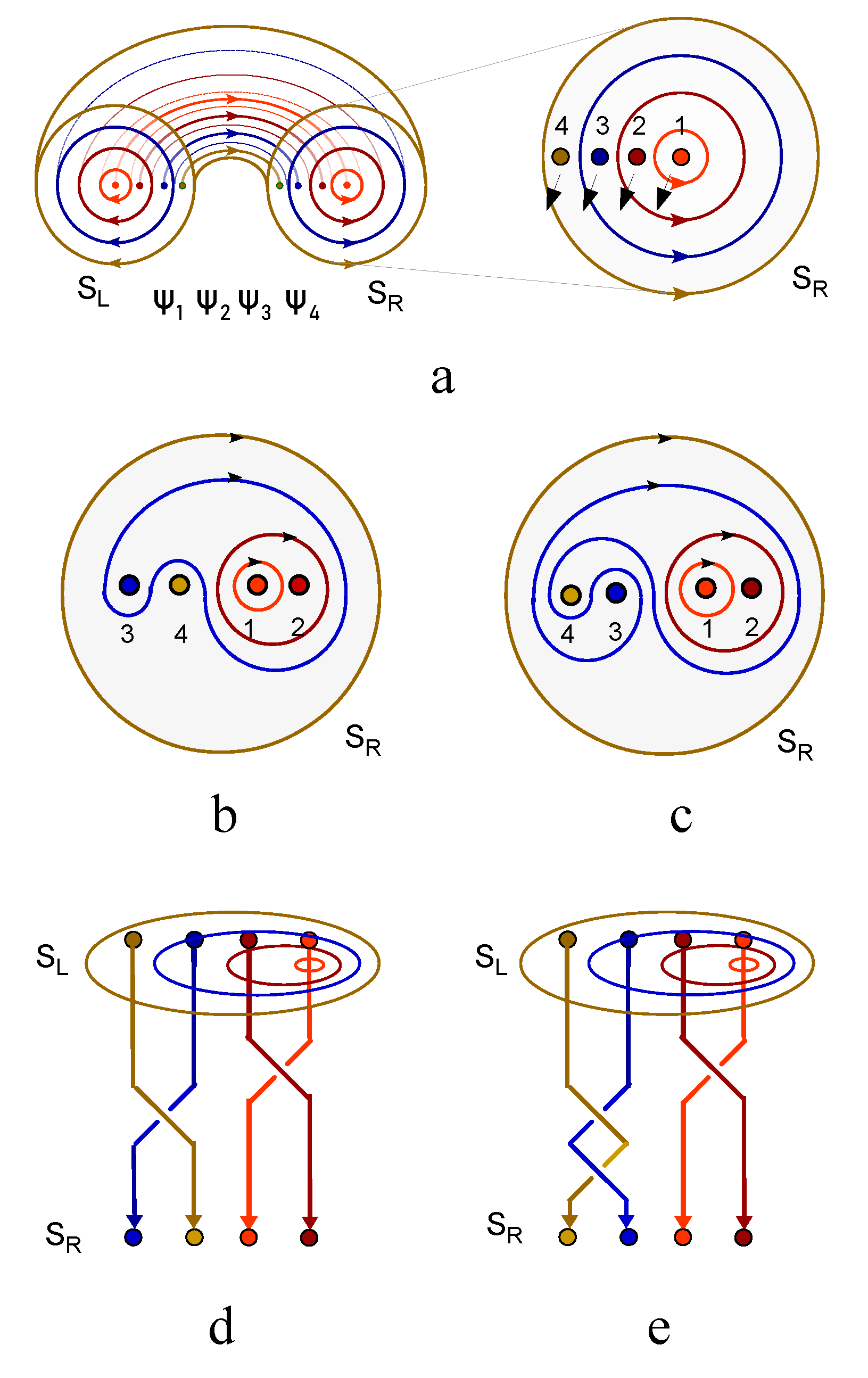

ith full loop state. For the initial knot crossing state of the right handed trefoil knot in

Figure 5,

, decomposing the three crossings of

leads to eight possible full loop states,

The four vacuum states with two loops,

,

,

and

, are topologically equivalent. The three vacuum states with one loop,

and

, share the same topology. There is only one vacuum state with three loops,

. The power indices in Jones polynomial with respect to the right handed trefoil knot in

Figure 5 encoded the total number of topologically inequivalent loops state,

where

. The Jones polynomial of the left handed trefoil knot reads

. The Jones polynomial is independent of the sequential order of decompositions of the three crossings. Permutating the spatial locations of the three crossings in decomposition always leads to the same eight vacuum states and the same Jones polynomial. The Jones polynomial of the left handed trefoil knot is expressed by the same counting sequence

, except that the variable

t is replaced by

in Eq. (

44). In the Ising model of knot lattice, the polynomial variable

t is a Boltzmann factor with respect to different energy,

. The value of local spin

with respect to crossing state is

(

) in the right (left) handed trefoil knot. This physical interpretation coincides exactly with the rigorous proof in knot theory. On the other hand, different vacuum states also evolve into different excited states under thermal fluctuation, i.e., different loop configurations evolves into different knot lattices, therefore the Jones polynomial builds a robust bridge between zero energy states and excited states with non-zero spins, as long as thermal fluctuation does not destroy the topology of knot lattice.

The right handed trefoil knot in

Figure 5,

, is one of the eight crossing basis,

with

. The vacuum basis also has eight components,

with

. The

matrix of Jones polynomials is a transformation matrix from the vacuum space to the crossing space,

This transformation equation holds for the most general case of a knot lattice with

N crossings. The Jones polynomial matrix encodes all possible series decay from a knot lattice of crossings to a lattice of full loops, because the knot lattice with crossings is in excited state and unstable, the fluctuating current lines inevitably touch each other at some time point and fuse into vacuum states. The full loop state is the most stable state against thermal fluctuations.

The Jones polynomial determines the partition distribution of loop states with different number of loops in zero energy state. In the highly degenerated Hilbert space of zero energy state with respect to the right handed trefoil knot (

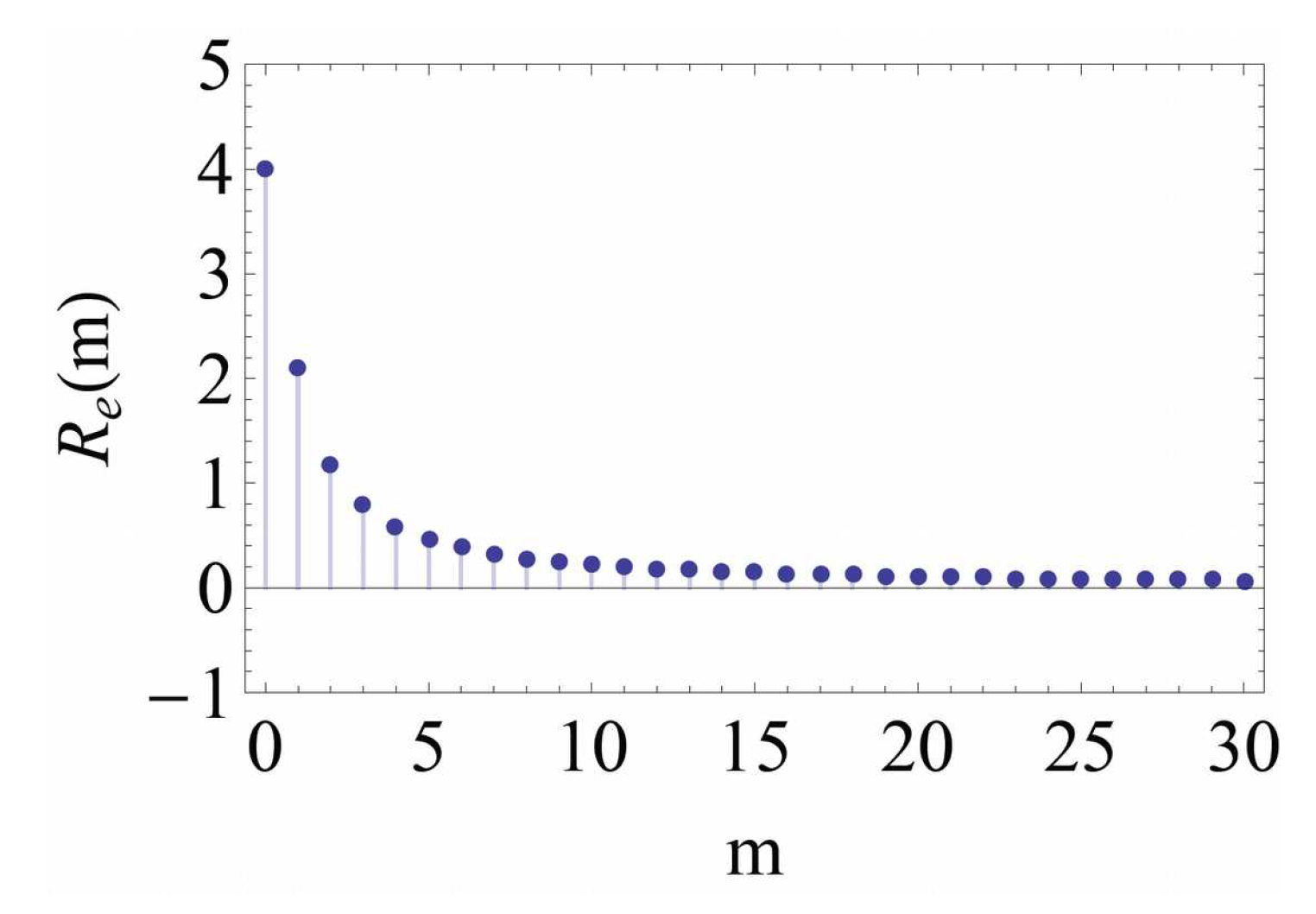

Figure 5), the loop states with three loops contributes the major part to the Jones polynomial. On the contrary, the three loop states contributes the minimal part to the Jones polynomial. This conclusion holds for link on a general knot lattice with many crossings. Only chiral flow in knot lattice survives during thermodynamic evolutions, the flow in knot lattice with opposite chirality exponentially decays to zero (as shown in

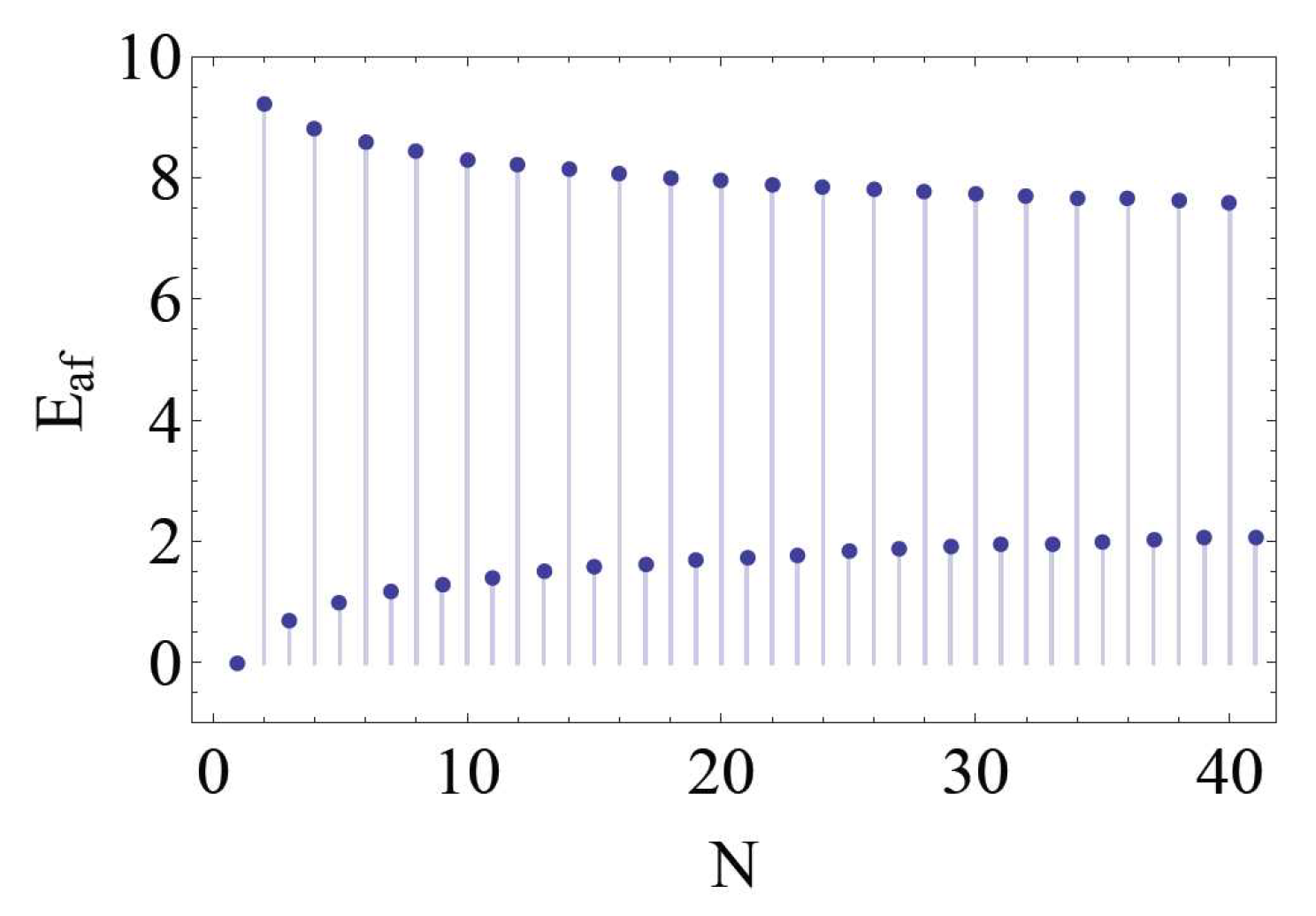

Figure 6). Therefore the series decay of knot lattice prefer choosing a chiral path.

The energy of the three crossings of trefoil knot

Figure 7a is quantified by an effective Hamiltonian,

. The high energy state

is defined by three crossing states with the same positive topological spins across the cutting surface in

Figure 7b. The low energy state

is a crossing state formed by two fluxes without penetrating through the boarder. Every topological vortex costs at least two continuous braiding operations as well as two identical crossing states. The total energy of many topological vortices on boarder surface is counted by the linking number of the knot lattice of magnetic fluxes,

The eigenenergy of Hamiltonian Eq. (

46) counts the total energy of the 12 topological vortices in

Figure 7b. When the docking points of the four fluxes in cross section

or

are connected to fuse the four separated flux loops into one flux loop, the knot pattern in Figure 55e realizes a chiral trefoil knot in

Figure 7a. The flux segment that connects the edge points of flux No. 2 and flux No. 3 cross the boarder surface once, while the edge flux segment has to cross three boarder surface to connect flux No. 1 and No. 4. There are four topological vortices created in the left-hand cross section

. On the right-hand cross section

, the edge flux connecting flux No. 1 and No. 3 intersect with four boarder surfaces and created four topological vortices swirling around the intersecting point. Four topological vortices are also created along the edge flux segment connecting flux No. 2 and No. 4. There are eight topological vortices in total in the right-hand cross section

(

Figure 7b). The total number of topological vortices in

grows with respect to an increasing number of periods of braiding.

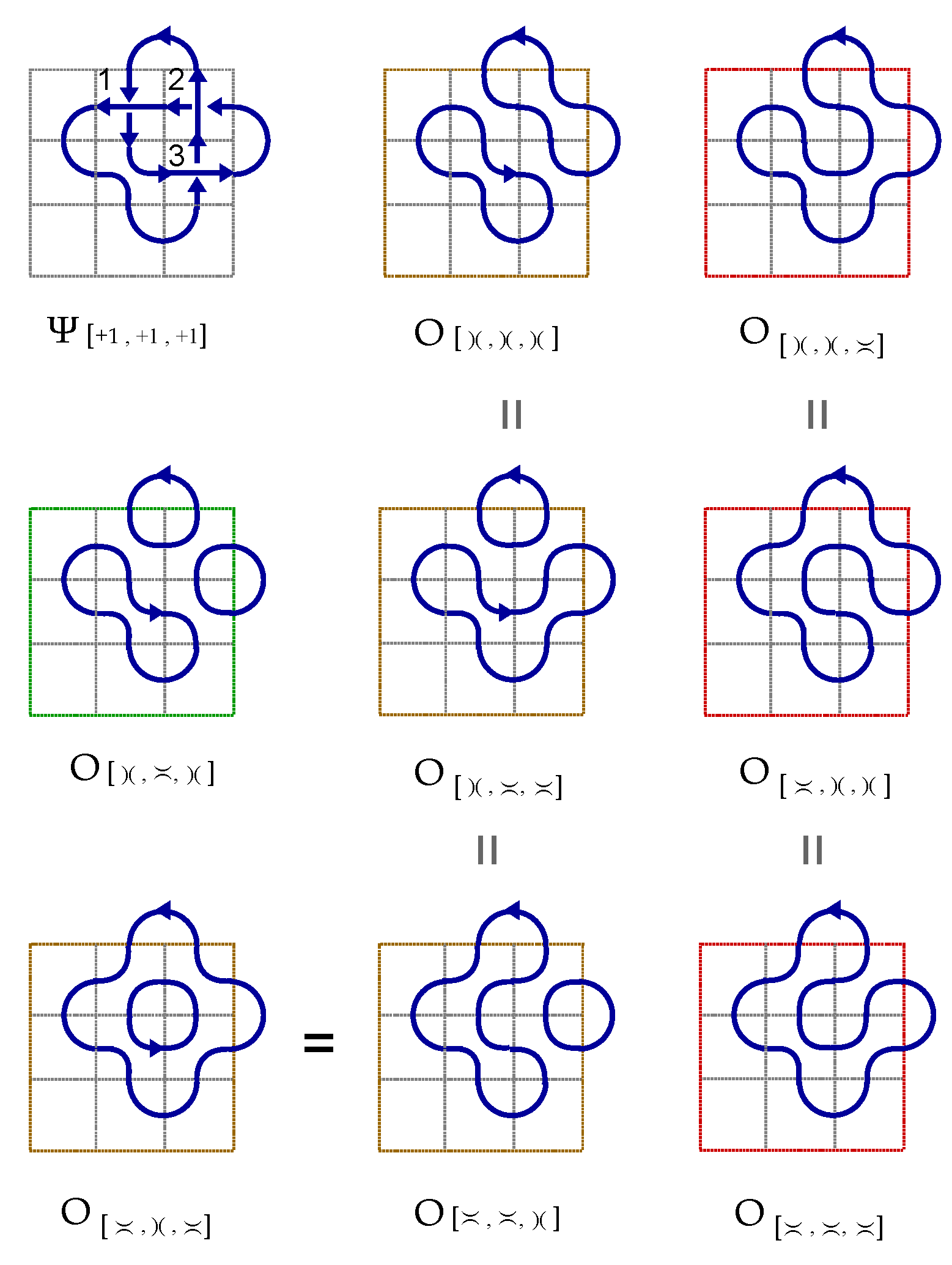

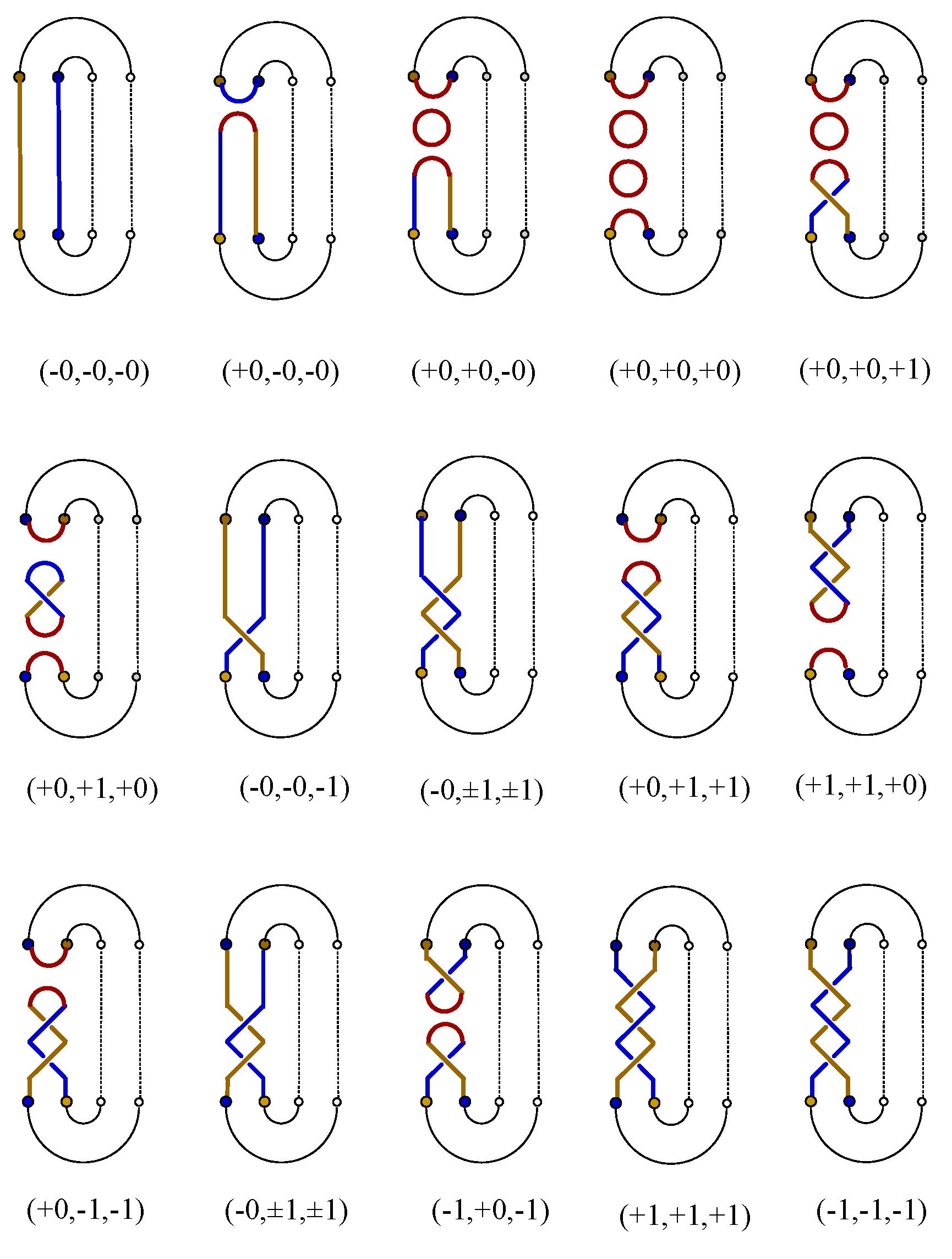

The Hilbert space of three spin 1 particles is expanded by

basic knot patterns, 15 exemplar knots are listed in

Figure 8. Every knot pattern is labeled by a general quantum state

The left-handed trefoil knot is denoted as

The ferromagnetic state

represents the right-hand trefoil. The Kauffman bracket polynomial of the left-hand trefoil reads

The Kauffman bracket polynomial of the right-hand trefoil is

, in which the parameter

A is

The chirality of the trefoil knot is distinguished by the Kauffman bracket polynomial. Since the trefoil knot in

Figure 7c is created by

braiding operations, the highest power of

A in bracket polynomial Eq. (

47) is

. The fractional quantum Hall state in the cross section

of

Figure 7c carries fractional charge

. Therefore the chiral edge modes in FQHE is distinguishable by Kauffman bracket polynomial. When the ferromagnetic state

flips to

, the total spin

flips to

, driving the Kauffman polynomial of the left-hand trefoil into that of the right-hand trefoil. The chirality of trefoil knot is spontaneously mapped into chiral Jones polynomial as well as Kauffman polynomial,

The Jones polynomial is equivalent to Kauffman polynomial under the exact map of variables

. The trefoil knot in

Figure 7a is mapped to crossing state of three mutually perpendicular fluxes in three dimensions with a special boundary condition (

Figure 7c). Both Jones polynomial and Kauffman polynomial can be interpreted as the Boltzman weight of collective spin state

with respect to eigenenergy

.

At high temperature, a magnetic flux within low magnetic field could cut another flux and reconnect to each other, this dynamic process drives an overcrossing flipping to undercrossing (or vice versa). In the plasma analogy theory of FQHE, the inverse of total number of braiding operations is proportional to effective temperature. At finite temperature, the partition function of three topological spin1 is the sum of Boltzmann weights of all possible collective states of the three crossings,

where

indicates all possible collective spin configurations of three crossings. The simplest formulation of the total energy of three crossings is

. The coupling interaction between crossings leads to more complex energy formulations. The partition function with

is not a topological invariant due to the absence of boundary condition with respect to each knot state. The Kauffman bracket polynomial is the eigenfunction

with respect to eigenenergy

. The Hamiltonian of three crossings

is equivalent to a renormalized writhing number of single loop,

. Therefore topologically nonequivalent knots are classified by writhing number, i.e., the total spin,

The partition function of three crossings is the sum of the Boltzmann weights with respect to different knots states,

where

is the writhing number of the

nth knot states. The Boltzmann weight measures the occupation probability of a knot state at finite temperature.

The knot polynomial of all possible knots that are generated out of three crossings is derived by Kauffman decomposition rules in knot theory,

where

and

. The polynomial of knot including closed loops are decomposed following the conventions,

and

. In

Figure 8, the knot state of

represents two linked loops,

(

) represents two loops circling in the same (opposite) direction. The writhing number equation for

is equivalent to the linking number of two interlocking loops,

. The Kauffman bracket polynomial of nontrivial knot states in

Figure 8 are derived from Kauffman decomposition rules,

An implementation of the knot variable

A by periodical wave

transforms the bracket polynomials into the superposition wavefunction. The simple bracket polynomials

are eigenfunctions of angular momentum operator

. The eigenvalue of

equals to the number of braiding operations as well as the writhing number of single loop, i.e.,

or

. The knot states with the same topology in

Figure 8 are represented by the same Kauffman polynomials,

However the knot states with the same topology do not share the same energy due to the geometric bending or twisting of the loop. Three coupled spins generate 64 possible collective states in total. The total number of knot states with respect to the writhing number

is denoted as

and counted as following,

The energy of knot is assumed to be proportional to the writhing number

,

. The thermodynamic partition function of three coupled topological spins is

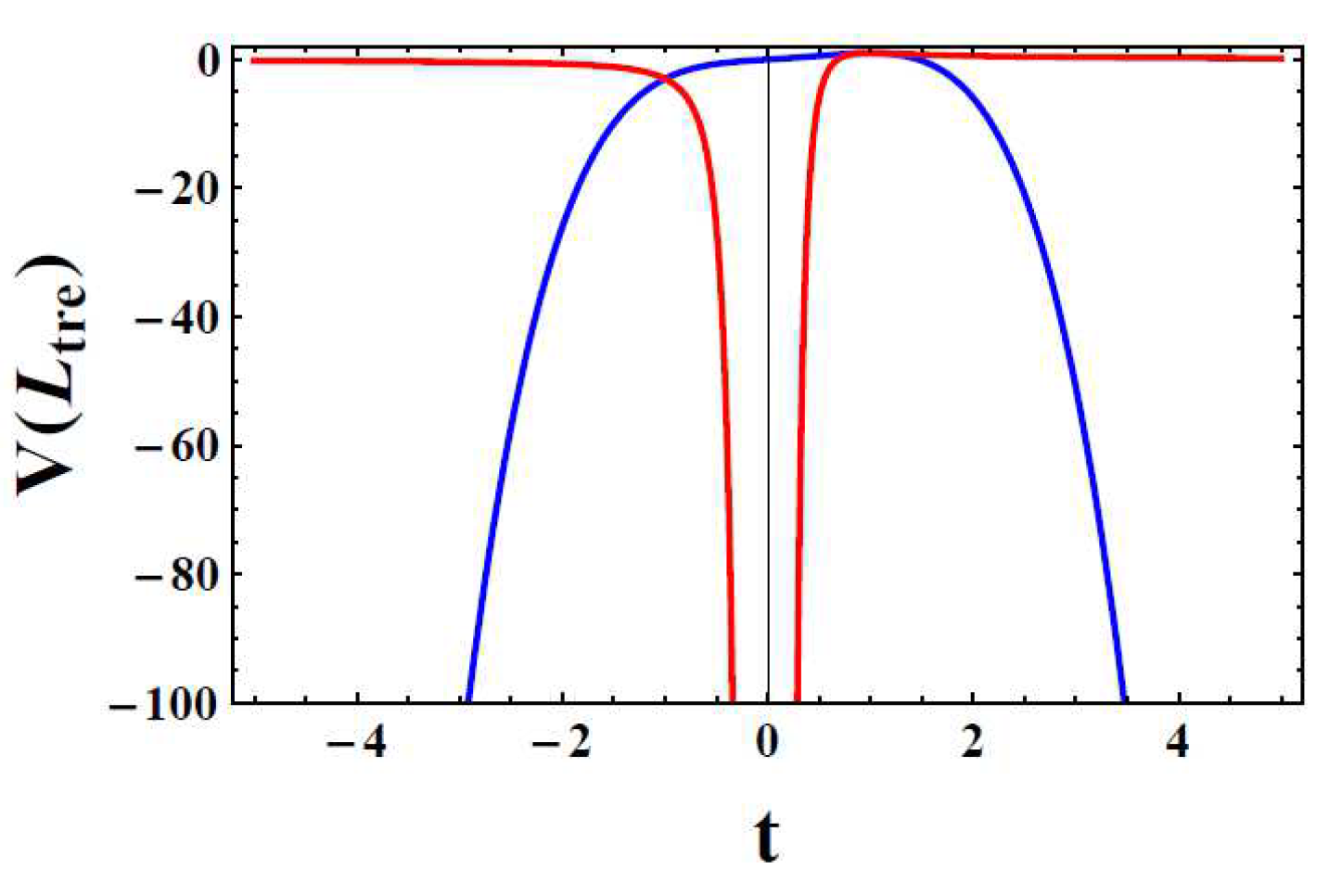

The free energy

and thermodynamics entropy

are spontaneous output of this partition function,

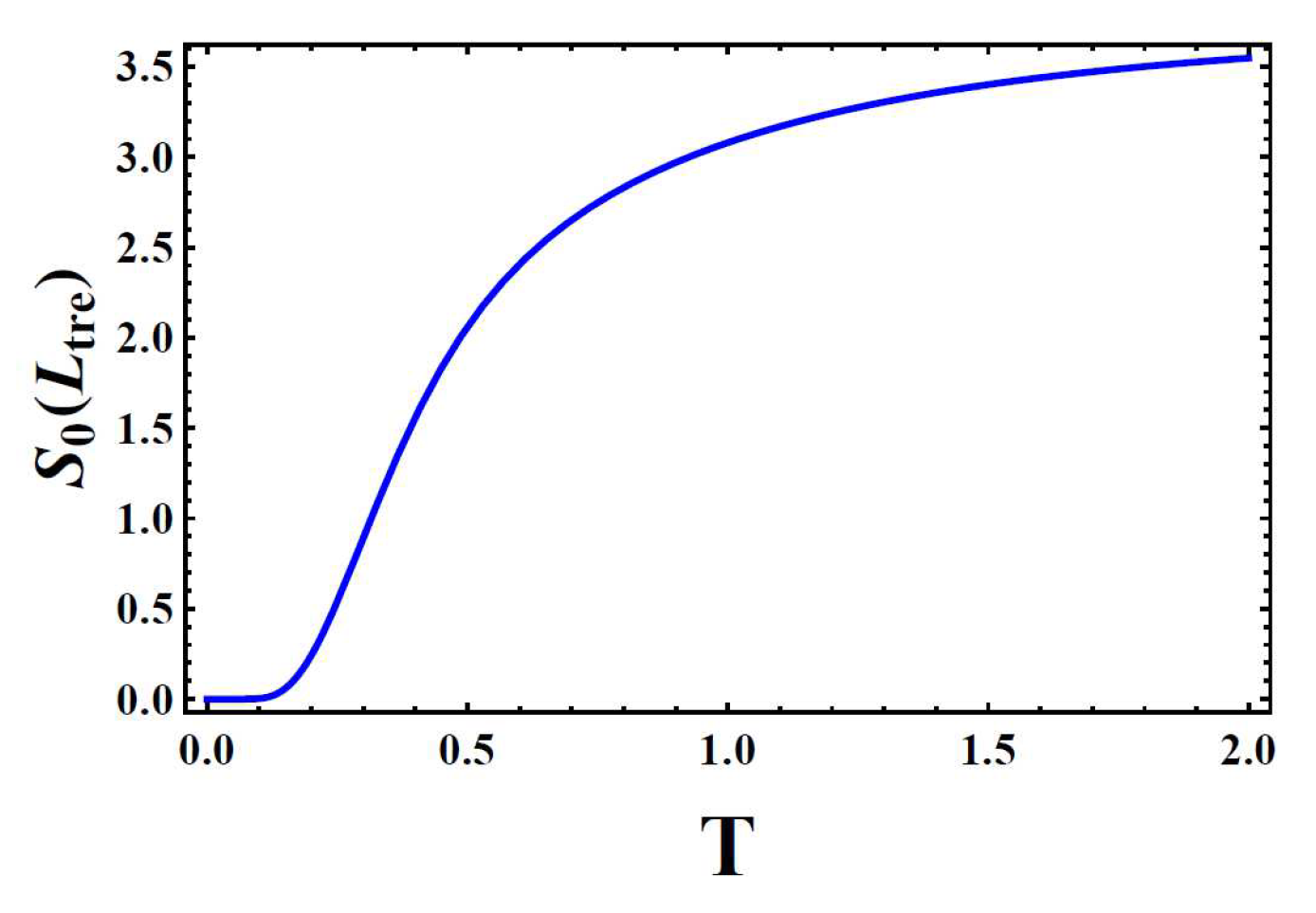

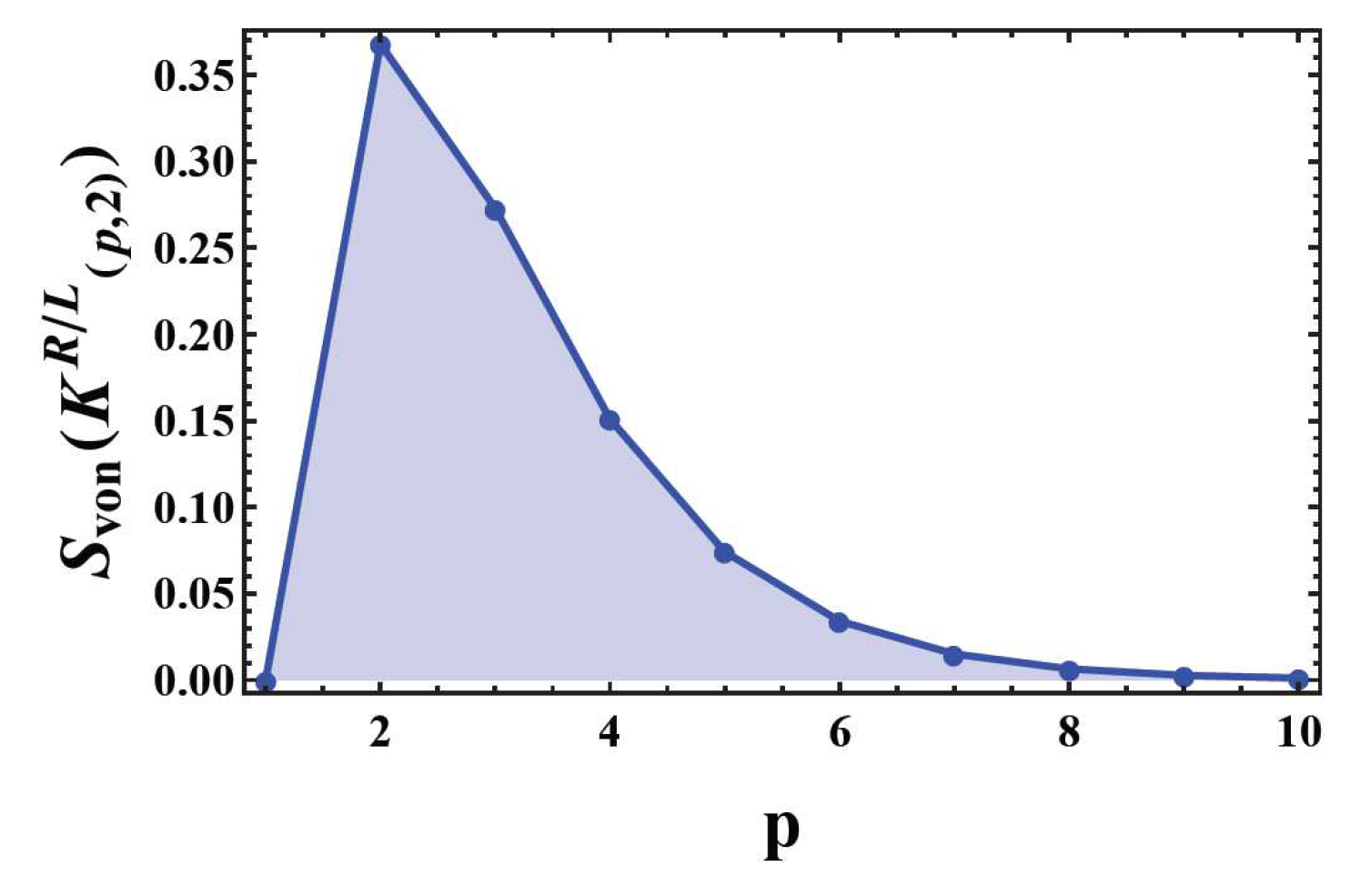

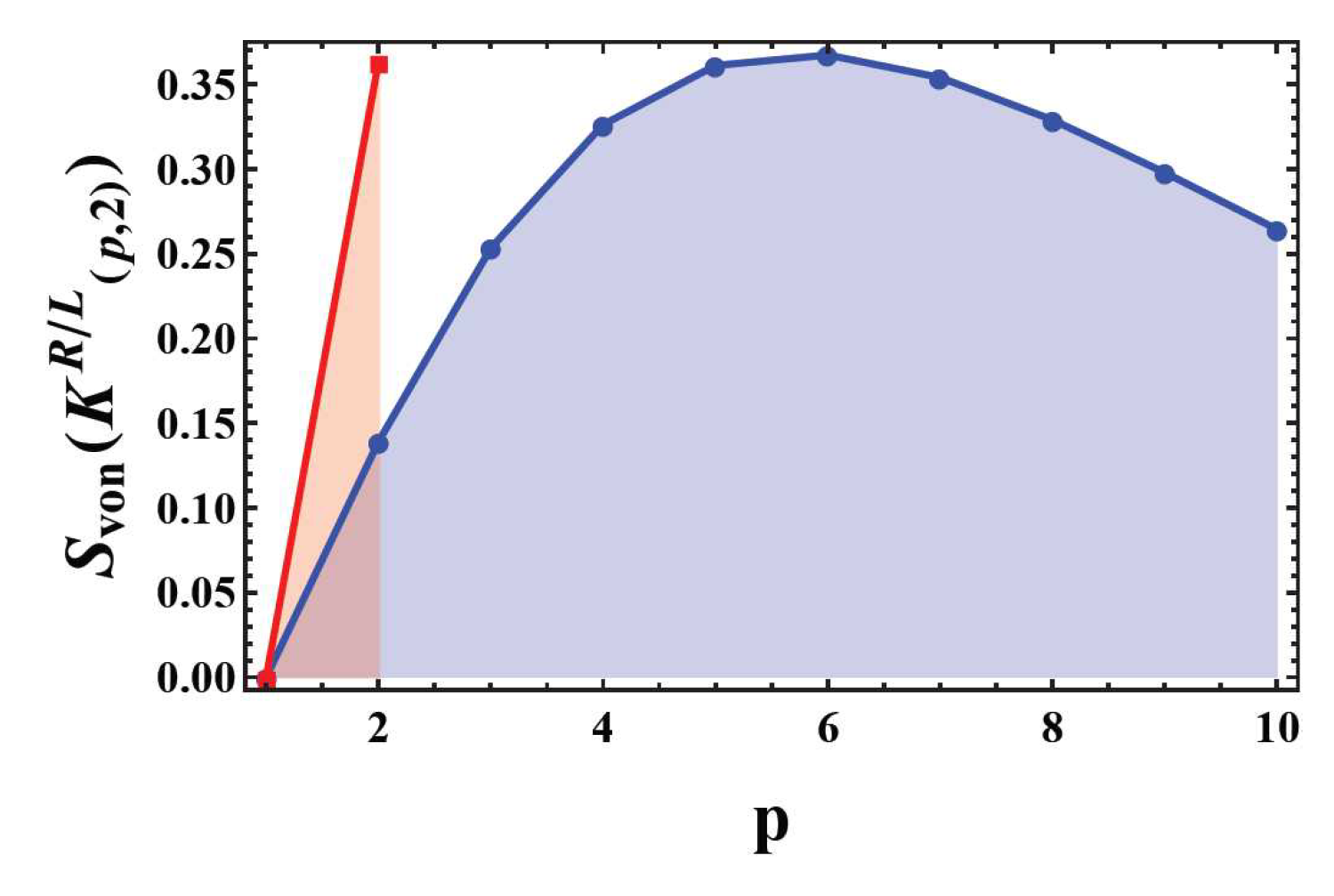

The entropy

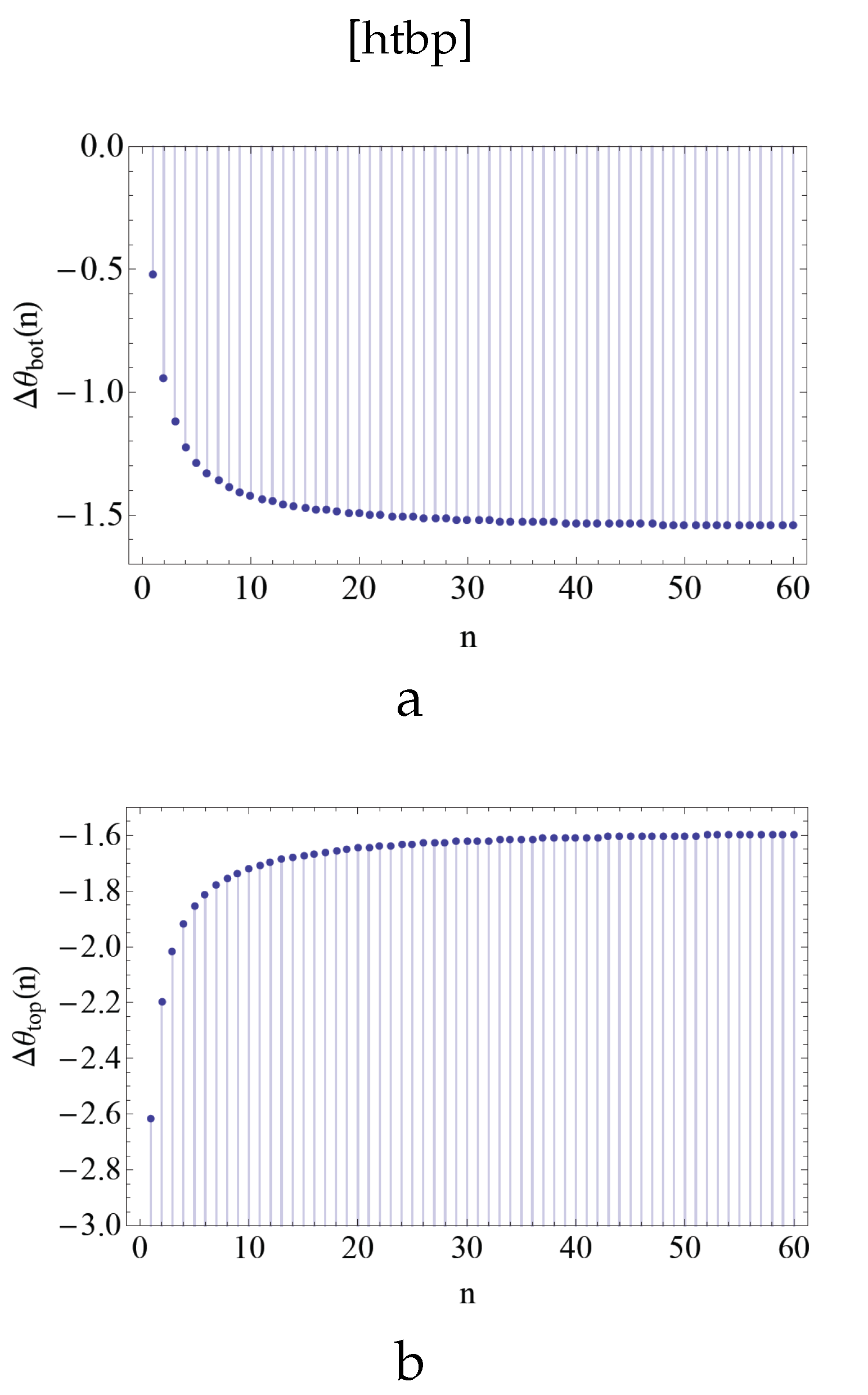

approaches to zero when temperature decreases to zero (

Figure 9). The three knot crossings tend to orient their spins in the opposite direction of external field

h. There is no coupling between different crossings. Therefore the entropy of three free crossings (as showed in

Figure 9) is similar to that of three free Ising spins. The crossings in knot lattice are always strongly correlated with one another. It is a reasonable assumption that the left handed trefoil knot shares the same energy as the right handed trefoil knot in absence of external field. Therefore the total Hamiltonian of knot lattice in external field is the sum of the coupling interaction and the interaction with external fields,

where

is the total number of crossings. The output energy of

acting on the knot configurations in

Figure 8 are listed as following,

The eigenenergy of states with writhing number

includes the coupling interaction between a positive crossing and a negative crossing, which is spontaneously eliminated by Hamiltonian

. The corresponding thermodynamic partition function of a knot with three crossings reads

The coupling interaction between crossings introduced non-topological factors into partition function. The thermodynamic entropy

with respect to

is similar to entropy

Eq. (

56) on the cross sectional surface of

, but expands into the extra dimension defined by coupling strength

J.

The knot configurations with different eigenenergy (i.e. writhing number) may share the same topology. The knot with only one crossing keeps its topology invariant when it hops from excited state

to ground state

under thermal fluctuations. The topology experiences a sudden change when the knot hops from the left-hand or the right-hand trefoil knot to ground state with

. The dynamics hopping between the two chiral trefoil knot states,

and

, is governed by the effective Hamiltonian,

Notice here

, the Jones polynomial wavefunction is expressed by orthogonal basis,

The density operator of a mixed state

with the probability

being

and probability

being

is defined as

where

and

. The uncertainty of the mixed state

is measured by the von Neumman entropy,

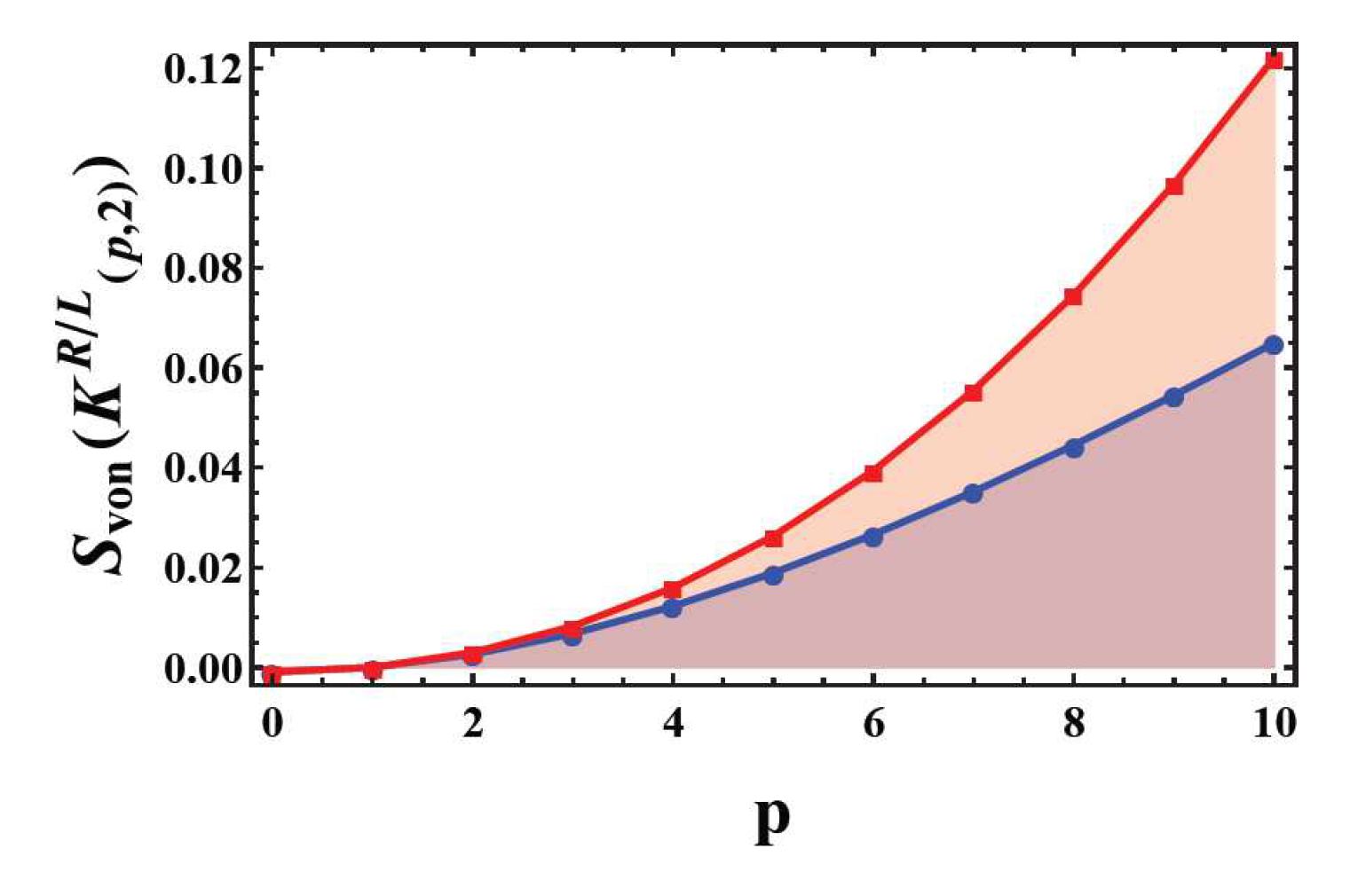

Because the right hand trefoil knot state is not a pure state in the orthogonal basis space, itself is a mixed state in the orthogonal basis space. Substituting the Kauffman polynomial Eq. (

54) into the von Neumman entropy of the pure state

yields

Substituting the Boltzmann factor

into Eq. (

65) yields the von Neumman entropy that evolves with temperature,

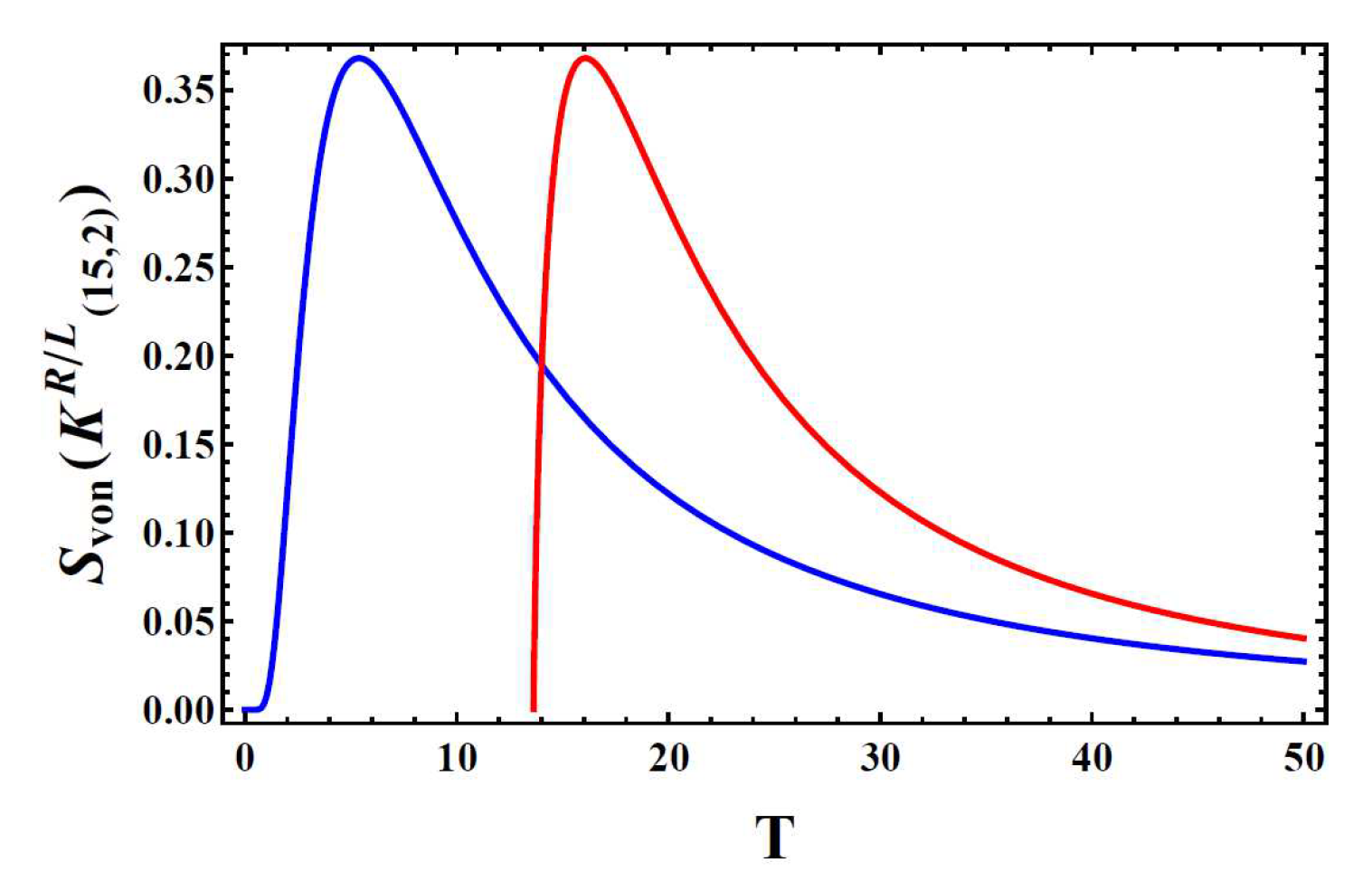

Figure 10 shows that the von Neumman entropy of the right hand trefoil knot reaches the maximal value before it decays to zero near zero temperature. The entropy of the left hand trefoil knot vanishes at finite temperature (

Figure 10). The entropy of other pure states is derived in a similar way of combining Kauffman polynomial Eq. (

54) and the von Neumman entropy Eq. (

64). The entropy of the single loop state

(as shown in

Figure 8) is constantly zero, so does its topological equivalent configuration

in

Figure 8.

A complex topological fluid is composed of many different knots. These knots entangle with one another to form a knot lattice when temperature drops. As temperature gradually increases, the viscous topological fluid gains more kinetic energy to breaks into discrete flowing zones, decomposing a knot lattice into many isolated small loops. The Jones polynomial governs the topological decomposition process, offering an effective density operator to measure the number of all possible states with respect to certain number of loops. For a general knot lattice with

n crossings, the knot polynomial wavefunction is not the direct product of the polynomial of single crossing, instead it is a nonlinear function,

where

denotes topological index of local crossing state. The two crossing states

and topological vacuum state

at the

ith lattice sites are denoted as a vector of two components,

The crossing wavefunction transform into the uncrossing wavefunction under the decomposition operator

, which is derived from the Kauffman decomposition rule in knot theory,

The modular square of the crossing wavefunction is defined as the conventional Jones polynomial or Kauffman polynomial,

. As a result, the transformation operator

between Jones polynomials is the product of the decomposition operator

and its conjugate operator

,

acts on the polynomial with

crossings

. The polynomial with

crossings is further decomposed into the sum of polynomial with

crossings,

The iterative decomposition operation generates a series of Jones polynomials that maps the knot lattice with

i crossings into free loops configuration. The Jones polynomial of knot lattice with

n crossings reads,

The von Neumman entropy of the knot lattice with

n crossings is

The Jones polynomial is a topological invariant, as a result, the entropy Eq. (

73) is the topological entropy of knot lattice.

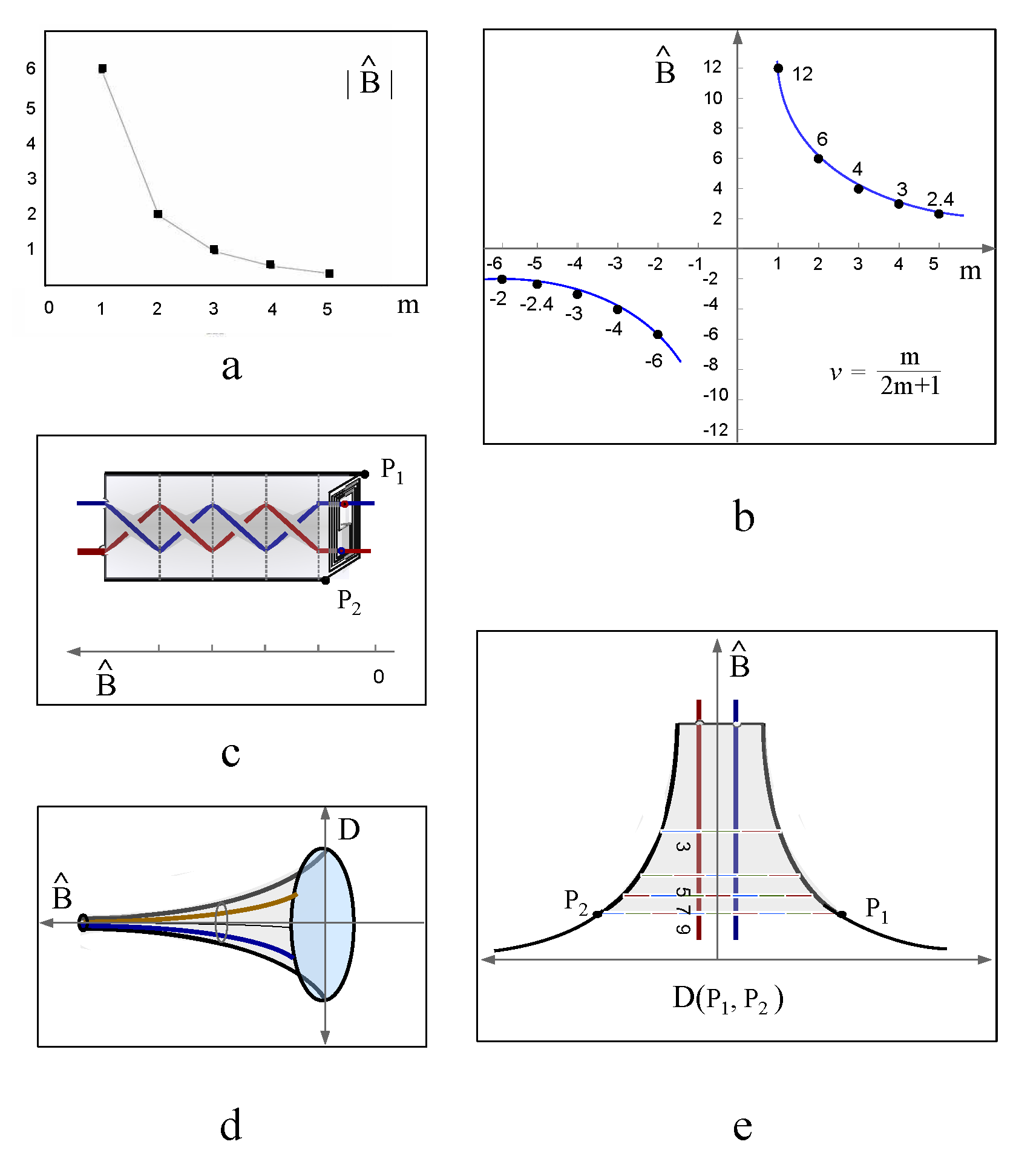

2.2. The knot invariant of chiral spin liquid of one dimensional spin chain

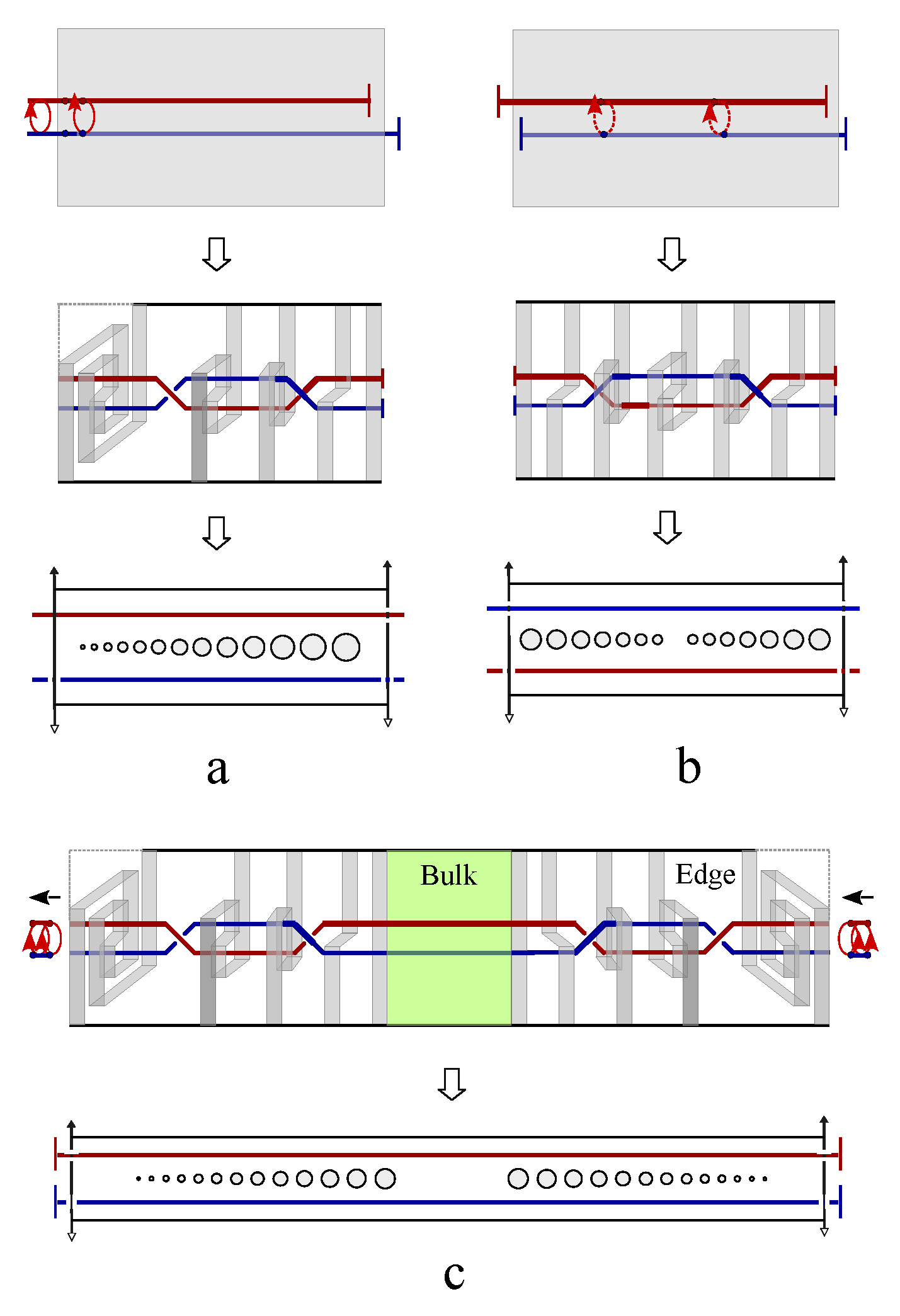

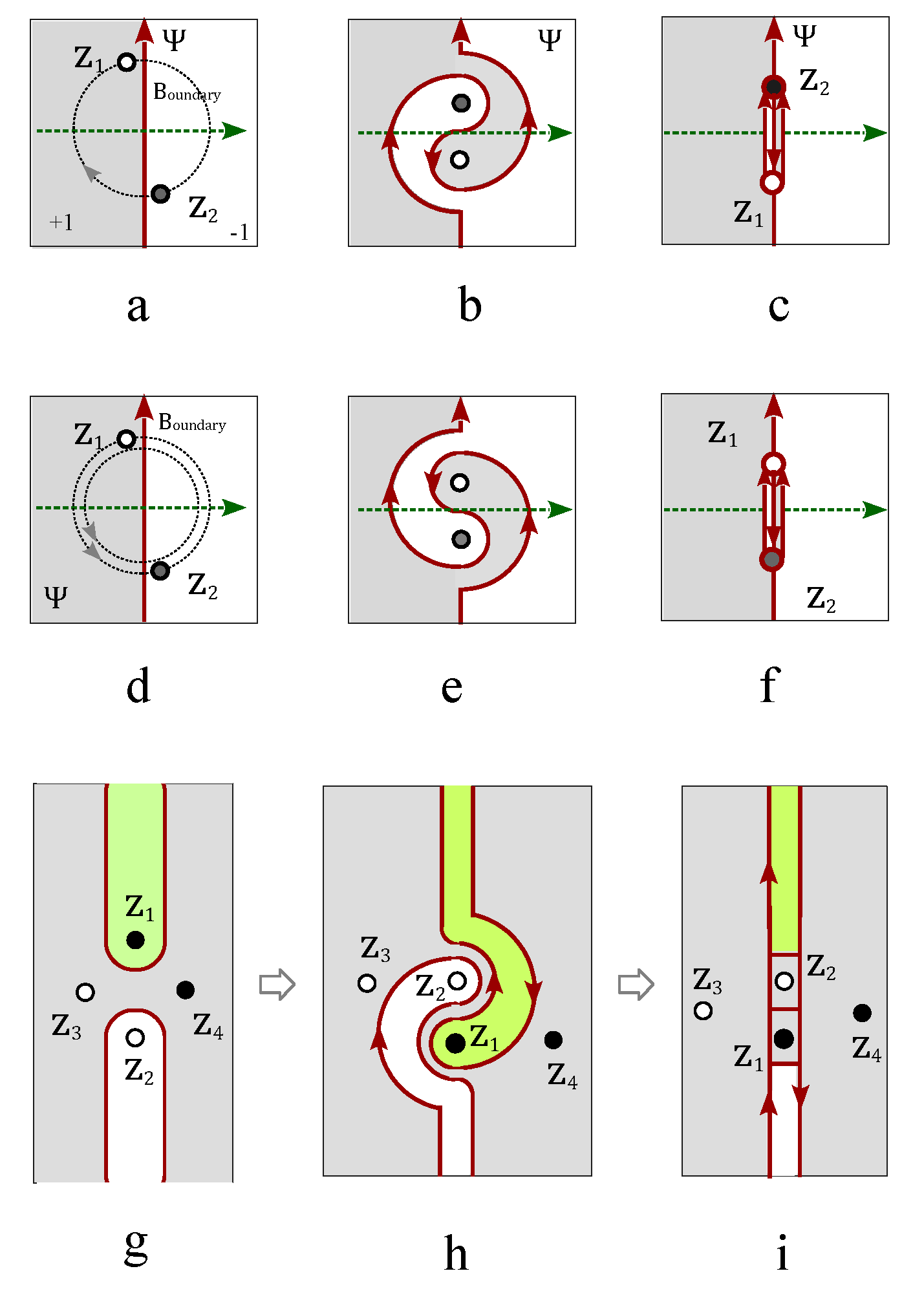

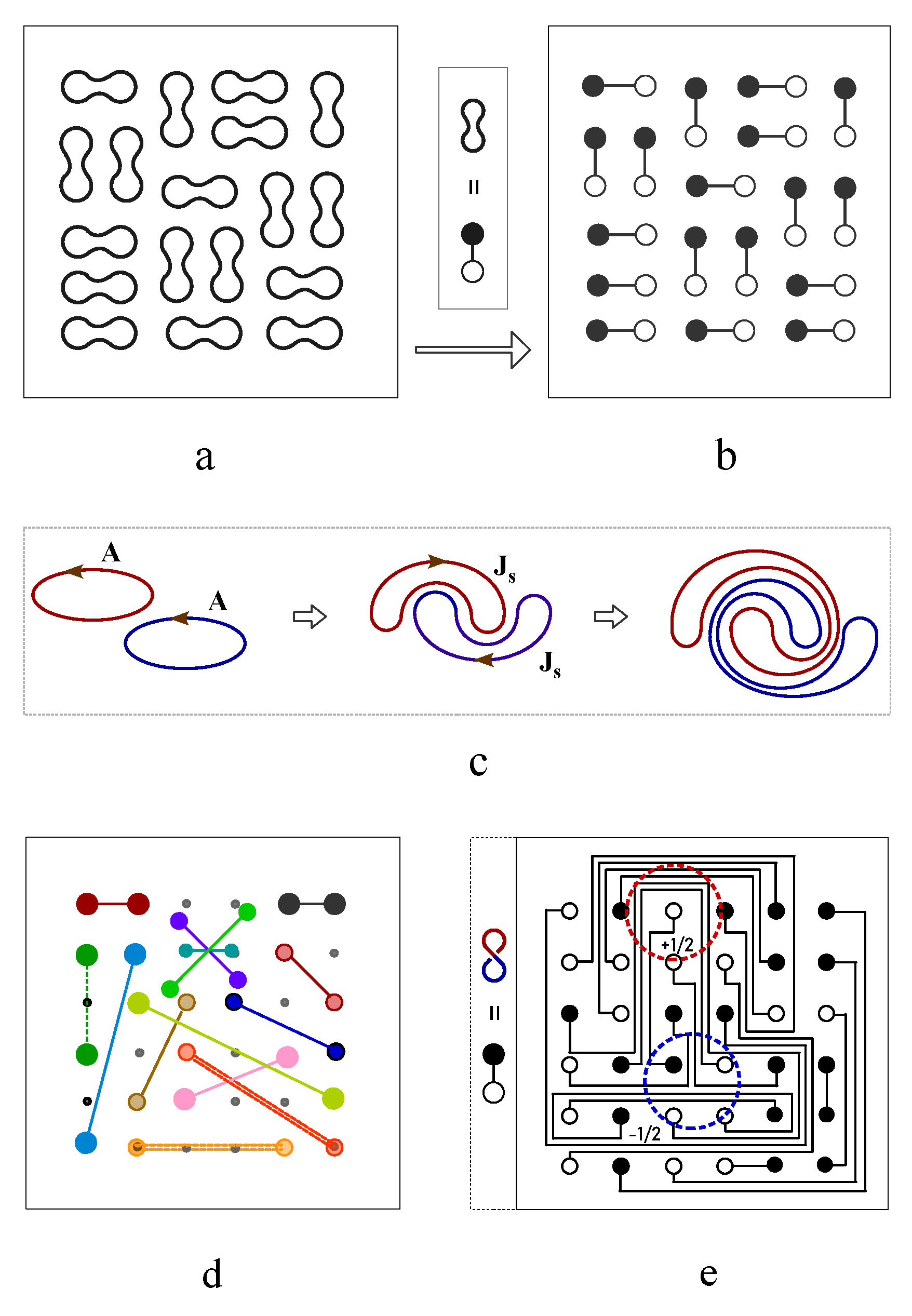

Every electric knot interlocks with an induced magnetic knot current. The electric knot with only one self-crossing interlocks with a simple magnetic loop (

Figure 11a) without self-crossing following electromagnetic induction effect. The link of this electric loop and magnetic loop is characterized by a topological invariant number—Linking number,

where

is the total number of positive (negative) crossings. The link in

Figure 11a has a linking number

. Flipping one of the two spins in

Figure 11a either unties the self-crossing into parallel lines (

Figure 11b) or generates one more crossing both on the electric loop and magnetic loop (

Figure 11c). This linking number is invariant during the flipping process. For a more general case of many coupled spins along one dimensional chain, the antiferromagnetically coupled spins is either represented by a knot lattice of electric loops or a topologically equivalent magnetic knot lattice (

Figure 11 d), there exist an exact one-to-one correspondence between the electric knot lattice and magnetic knot lattice. This exact correspondence also holds for a ferromagnetically coupled spin chain as well as an arbitrary spin liquid state.

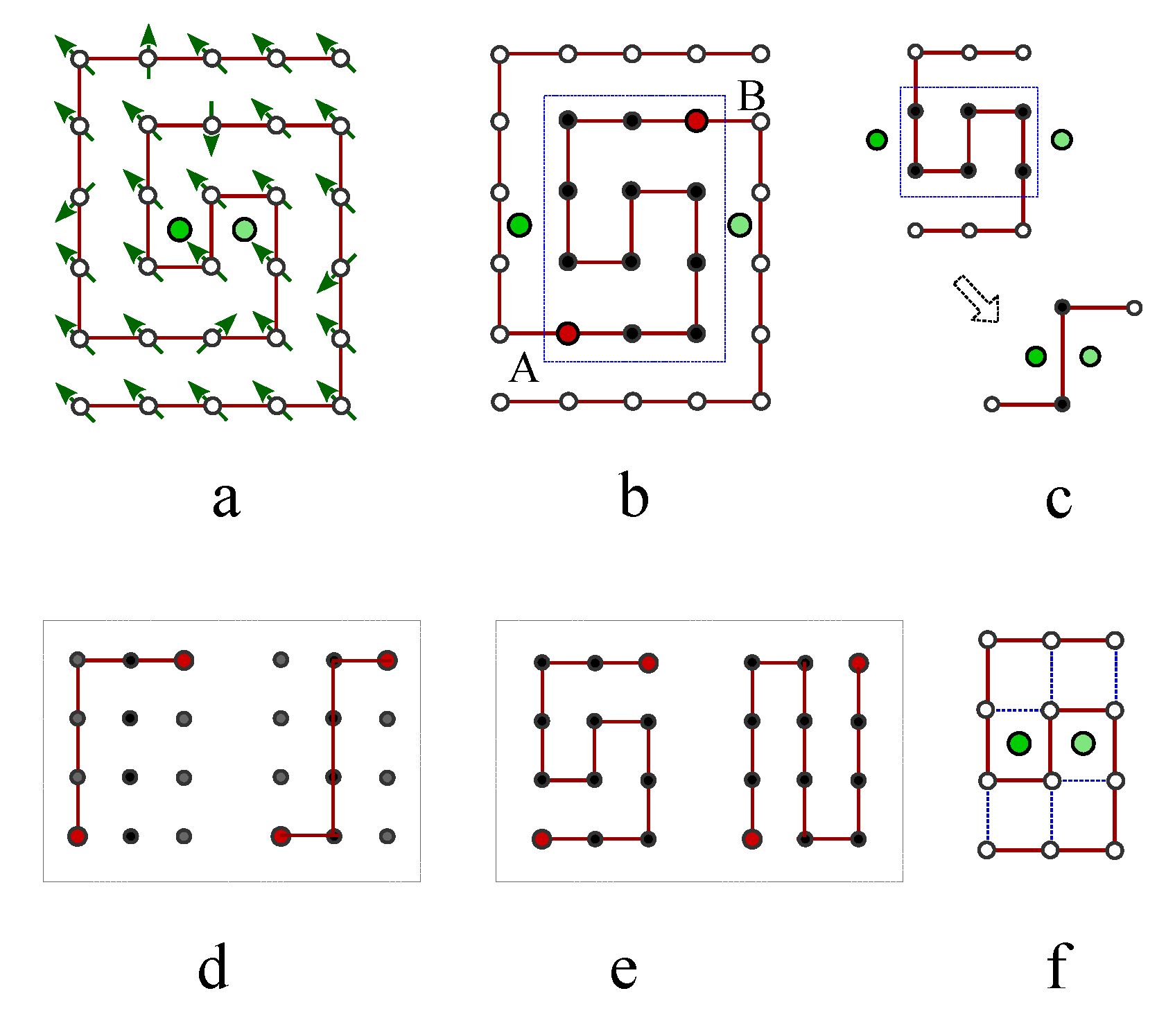

The combination of a knot lattice of magnetic fluxes and Thurston’s train track pattern constructs an unique topological representation of a spin liquid state.

Figure 12a shows an exemplar spin liquid state, where Ising spins are represented by arrows pointing up or down. Based on the convention of constructing magnetic knot lattice in

Figure 11 a-b, two antiferromagnetically coupled spins are represented by two parallel magnetic lines, while ferromagnetically coupled spins are represented by crossing magnetic lines. A magnetic line segment always connects two poles of the spin arrows with opposite magnetic charges (

Figure 12c). The linking number of the knot lattice formed by connected magnetic lines is independent of local direction of the line segments, therefore the knot lattice is further mapped into the same knot lattice generated by two magnetic fluxes that are oriented in opposite direction, as represented by the blue and red lines in

Figure 12d. When the two magnetic fluxes are immersed in an electronic fluid, the flowing electron fluid form laminar layers winding around the two magnetic fluxes under the propulsion of Lorentz force,

. To reconstruct exactly the same knot lattice as

Figure 12d, the left endings of the two magnetic fluxes are first fixed, and their corresponding right endings are braid in a designed protocol so that the cross section of the right ending of the electric laminar layer generates a winding path that is described by a topology theory called Thurston’s train track (

Figure 12e). As an application of Thurston’s train track theory, the number of layers of electric line segments on the two opposite sides of the magnetic fluxes are counted and labeled by

and

correspondingly. An integral electric charge splits into fractional charges passing thorough the train tracks,

leading to fractional Hall resistivity in fractional quantum Hall effect [

12]. The train track pattern in

Figure 12e generates two fractional charges,

and

.

The train track of electric current on the boundary is a stable topological pattern against local perturbations on spins in the bulk chain. In the exemplar spin configuration of spin liquid state in

Figure 13a,

two ferromagnetic domains are separated by a topological kink soliton, (indicated by the orange dash line on the left hand side of the spin pair of red arrows. Flipping the local spin pairs labeled by red arrows does not annihilate the kink,

but transferred it to the right hand side. Therefore,

and

share the same eigenenergy,

. Flipping the local spin pair labeled by red arrows in

Figure 13b annihilates two kinks simultaneously and leaves only one kink behind.

The eigenenergy of this spin liquid state is the energy gap of one kink,

. Topological kink solitons always generate or annihilate by pairs to keep the total topological charge invariant. The linking number of the knot lattice is invariant during these local flipping operations in the bulk,

so does the train tracks on the boundary. The fractional charges on the boundary is quantized by the topological linking number,

where

is the total number of effective braiding operations. As proved by the topological path fusion theory of fractional quantum Hall effect [

12], this fractional charge straightforwardly determines the fractional Hall resistivity,

Therefore, the fractional Hall resistivity is quantized by topological linking number, this quantization rule is different from that of integral quantum Hall effect that is quantized by Chern number [

22].

The linking number of the knot lattice determines the energy gap of the spin liquid state, which is similar to the Haldane gap in one-dimensional Heisenberg chain with spin S antiferromagnetic coupling, i.e., an unique gapped ground state exists for an integral Spin [

23]. Here an integral linking number indicates two fully separated magnetic fluxes without any touching point (

Figure 14a). For half-integral linking number, there always exist two vortices penetrating through the electric laminar layer that acts as a boundary layer separating the two magnetic fluxes (

Figure 14b). The two vortices glue the two magnetic rings into one big ring with a self-crossing point, which is exactly the boundary of m

bius strip. The magnetic current along the boundary of m

bius strip represents a topological spin

state,

and

, where

represents the two topological vortices that cannot be eliminated by local operations. The local fluctuation of magnetic fluxes can also generate a pair of vortices crossing the electric laminar layer (

Figure 14c) with topological spin 0, however this vortex pair is unstable and tend to annihilate each other under thermal fluctuations (

Figure 14d). There is no topological vortices on the electric boundary layer for a magnetic knot lattice with an integral linking number, for the exemplar

Figure 14e, the knot lattice of two linking magnetic rings generates electric wrinkles with a topological spin

. Braiding the magnetic flux segments of spin 0 states three times generates two half integer spin states with opposite spin S =

and S =

. The fractional charges

and

on the boundary cross section between the two states S =

and S =

(

Figure 14f) are unstable against local thermal fluctuations, reducing to spin 0 state without topological crossing. The unstable fractional charges can also be generated out of spin

state by local braiding (

Figure 14f), the sum of a S = 1 state and S =

state, however the topological vortex pair is always robust against any local braiding or thermal fluctuations.

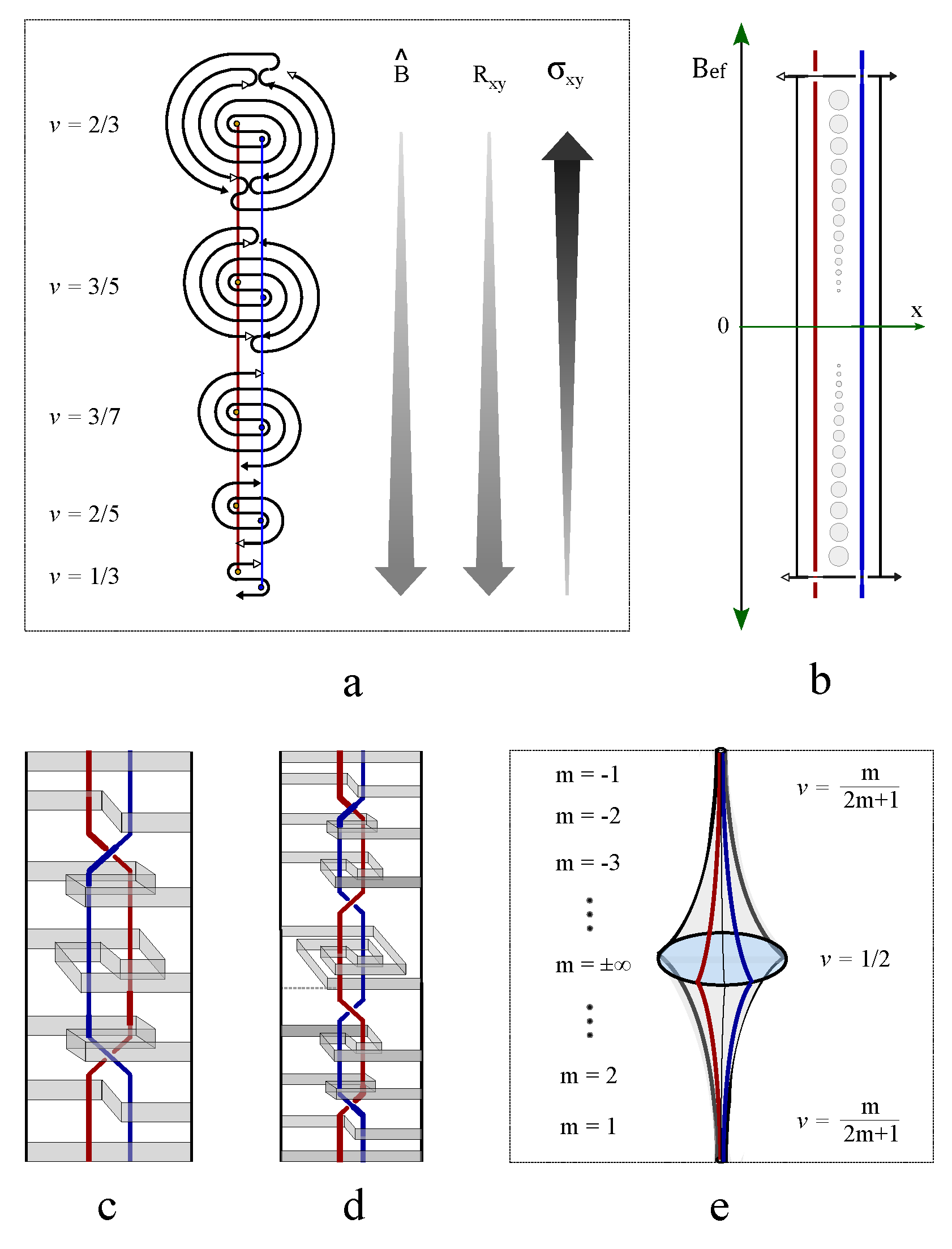

The real spin vectors sandwiched in between two magnetic flux lines represent the spins of real particles. The collective order of real spins fluctuate in thermal environment and transform from one collective phase to another. The two magnetic flux lines form a one dimensional knot chain of crossings, the collective order of many crossings in knot lattice is invariant during thermal fluctuation. A local crossing state in knot lattice is equivalent to topological spin 1,

.

and

represents the overcrossing state, undercrossing state and cross avoiding state respectively in

Figure 15a. The key difference of topological spin 1 from the spin 1 of real particle in nature is that the zero spin state

has two topologically different states, the vertical vacuum and horizontal vacuum states in

Figure 15a III-IV, denoted as

and

respectively. In knot theory, the crossing states in

Figure 15a are represented by Kauffman brackets,

In the knot lattice theory of anyons [

11], the partition function of a spin 1 state is mapped into a Boltzmann weight factor within external magnetic field

h,

which counts the occupation probability of a topological spin 1 on state

with eigenenergy

. The Boltzmann factors are exactly the corresponding Jones polynomials with respect to different crossing states, satisfying the Skein relationship

where the coefficients in Eq. (

83) are

The Jones polynomial is mapped exactly to Kauffman polynomial by redefining the variable

A in Kauffman bracket as

The Kauffman brackets Eq. (

Figure 8) transforms into brief formulations of Boltzmann distribution,

The Kauffman polynomial of spin zero state

measures the probability of finding spin up or spin down,

In statistical physics, the conventional partition function is the sum of Boltzmann weights of all possible states

The magnetization of the knot lattice is topological linking number

[

11], which is an integer at zero temperature but deviates from integer at finite temperature,

The linking number

equivalently counts the total number of braiding,

, where

counts the total number of clockwise (counterclockwise) braiding. In the train track representation of abelian FQHE, the one dimensional knot lattice of magnetic fluxes is generated by

periods of identical braiding, leading to average fractional quantum Hall resistivity

,

Substituting linking number Eq. (

89) into Eq. (

90) yields average fractional Hall resistivity at finite temperature,

where

t is the same parameter in Jones polynomial. At hight temperature, thermal fluctuation drives a local crossing to fluctuate among many different crossing states, different fractional Hall resistivity may appear simultaneously, Eq. (

91) measures the average fractional filling factors at certain temperature.

The single crossing

of

Figure 15 a-II braids the electron fluid surface into a folded lamination with an edge cross section state of

. More braiding operations in the same direction twists the single crossing

into an alternating knot chain in

Figure 15 b, which is represented by Kauffman bracket polynomial,

where

represents the overcrossings with

. If the left-hand endings of the two fluxes in

Figure 15 b are fixed, the right-hand cross section of the alternating knot generates the train track pattern with fractional filling factor,

The Kauffman bracket polynomial is mapped to the eigenfunction of angular momentum operator

,

The eigenvalue of angular momentum

records the total number of continuous braiding in the same direction,

Negative

indicates braiding operations in opposite direction. The fractional Hall conductivity only exist for the alternating knot chain of

Figure 15 b that is confined rigorously in two dimensions, the knot chain is prevented from flipping back to a trivial circle due to dimension reduction. The renormalized Kauffman polynomial of the alternative knot is

where

is the writhing number of a twisted circle. Here

equals to the sum of the signs of all crossings in the knot chain formed by a circle. The constant value of Kauffman polynomial suggests that the twisted circle shares the same topology with the initial unit circle. The fractional Hall conductivity encoded by alternating knot in

Figure 15 b is unstable at finite temperature due to the simple topology.

The collective configurations of many real spins in one dimensional chain can map into the same knot lattice of intertwined magnetic fluxes (

Figure 12). In

Figure 15 c, the leftmost and the rightmost edge zone of the double hyperbolic surface are covered by ferromagnetic phase of classical Ising spins, while antiferromagnetic phase covers the bulk zone in the middle. If the bulk lattice is composed of an even (odd) number of unit cells, the ferromagnetic phase of the leftmost edge zone orients in the same (opposite) direction to that of the rightmost edge zone (

Figure 15 c-d). The collective phases of far separated edge zones in opposite boundaries are strongly correlated, due to the robust topology of two intertwined magnetic fluxes. This topological correlation is stable against local thermal fluctuations unless the magnetic flux line is cut into discrete segments. The two intertwined magnetic flux loops in

Figure 15 c transform into two far separated loops under Reidemeister moves, which are represented by Kauffman bracket polynomial

. While two interlocking loops in

Figure 15 d is equivalent to two magnetic loops linked in a nontrivial way, described by Kauffman bracket polynomial

. If the left-hand and the right-hand edges of

Figure 15 c-d are fixed, a pair of hyperbolic surfaces of electron fluid lamination with opposite normal directions is generated in the middle zone. Each cross section of the hyperbolic lamination represents a qusiparticle with fractional charge

. These quasiparticles are always generated or annihilated by pairs under local fluctuations of real spins in one dimensional chain.

If the collective configuration of real spins in the bulk zone of

Figure 15 e are frozen, finite hyperbolic surfaces of electron fluid lamination are generated on the left-hand and the right-hand edge. Topological quasiparticles carrying opposite topological spin and fractional electric charge as are pushed to the edge zone. The linking number of the two interlocking loops in

Figure 15 e counts the total number of robust crossings which can not be generated or annihilated by local spin fluctuations, unless the loops are cut to reconnect. The two hyperbolic edges are flattened by opposite braiding operations to the initial braiding orientation in

Figure 15 e, the four crossings in bulk zone are transferred to the intertwined magnetic loops in infinity by keeping the topological linking number conserved.

The topological linking number of magnetic flux knot lattice is inadequate to distinguish different boundary states. In

Figure 16, braiding the leftmost edge three times in counterclockwise direction around the left normal direction and braising the rightmost edge three times in clockwise direction around the right normal direction maps into monotonic hyperbolic surface generated by five counterclockwise braiding around the left normal direction. The monotonic hyperbolic surface and double hyperbolic surface in

Figure 16 share the same topological linking number, but their geometric characters and dynamics of electron on the surface are completely different. Therefore quantum states characterized by topological number are usually highly degenerated.

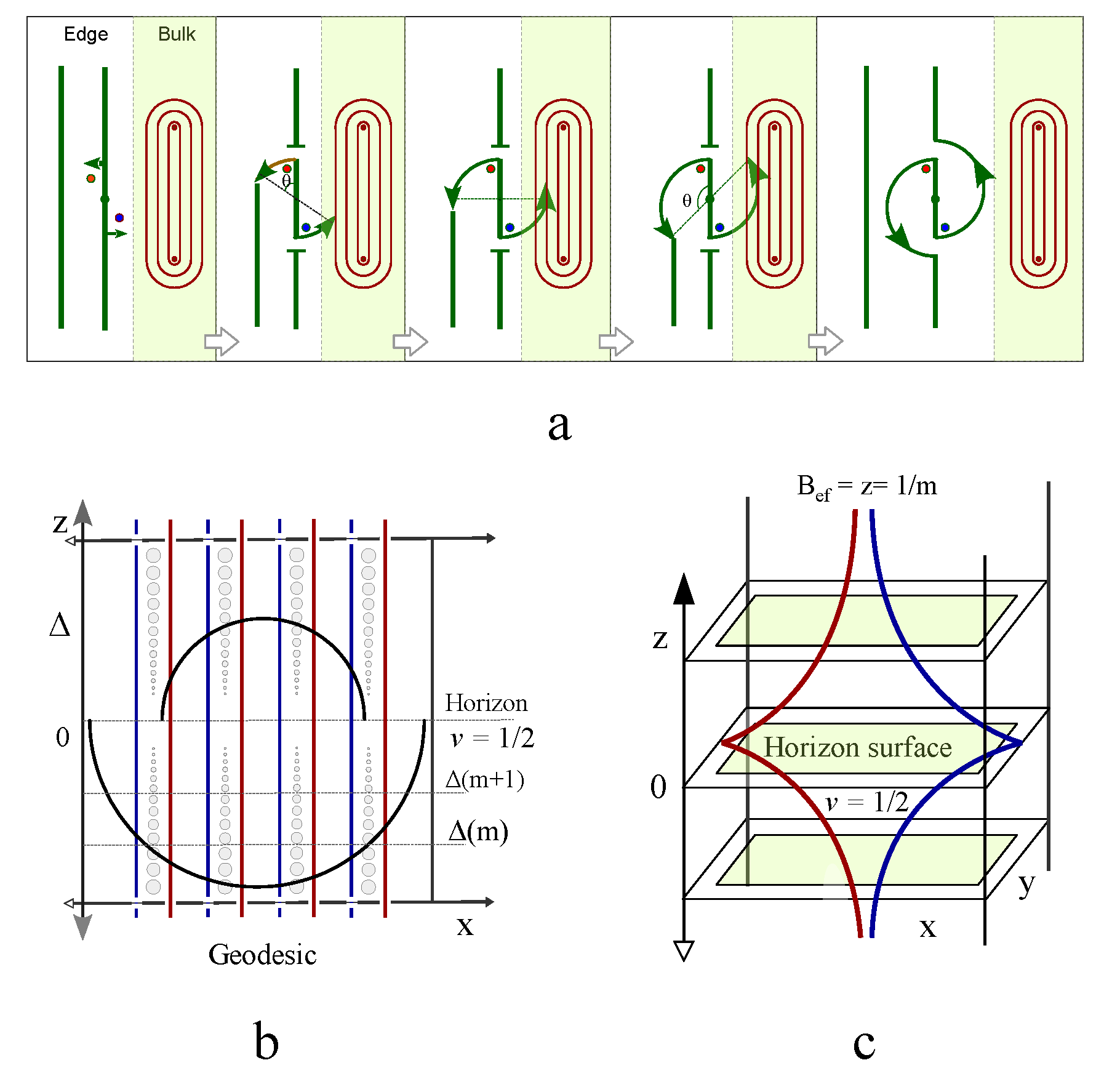

Inhomogeneous magnetic field folds the electron fluid lamination into non-Euclidean geometry, bending the flat lamination into hyperbolic surface with negative curvature. In

Figure 17a, the endings of the flux pairs on the right hand side are fixed. Braiding the endings on the left hand side in counterclockwise direction folds the flat lamination into a hyperbolic surface, which is implementable in experiment by designing a decreasing magnetic field strength from the right hand side to the left hand side. The train track on the left boundary cross section represents fractional filling state

. In

Figure 17b, both the two endings of the flux pair on the left and right hand side are fixed, braiding the middle points of the two fluxes expands the middle zone of the initial flat surface, generating a double hyperbolic surface on which the filling factors decrease from

on the edges to

in the middle.

Figure 17c shows a more complicate magnetic field configuration, a constant magnetic field strength is homogeneously distributed in bulk, but decreases in edge zones on both the left and right hand side. The initial flat lamination in edge zones are folded into hyperbolic surface by braiding operations on the left and right endings of the flux pair in counterclockwise direction. The filling factor decreases from the bulk to the edge, i.e., from

to

, until it reaches

on the outermost boundary. The conducting channel in the edge zone is not pure fractional quantum Hall states, instead is the superposition state of

and

, which forms resistivity in parallel. The resultant edge resistivity in edge zone obeys

Substituting the fractional Hall resistivity Eq. (

179) into edge resistivity Eq. (

97) yields

For a general edge zone covers fractional filling serial

, the resultant edge resistivity obeys the parallel resistivity equation,

Since the electric lamination in the edge zone is continuous during topological braiding, the fractional filling factor equation

for edge lamination in

Figure 17c is generalized to a continuous filling function,

, the resultant edge resistivity obeys

where

and

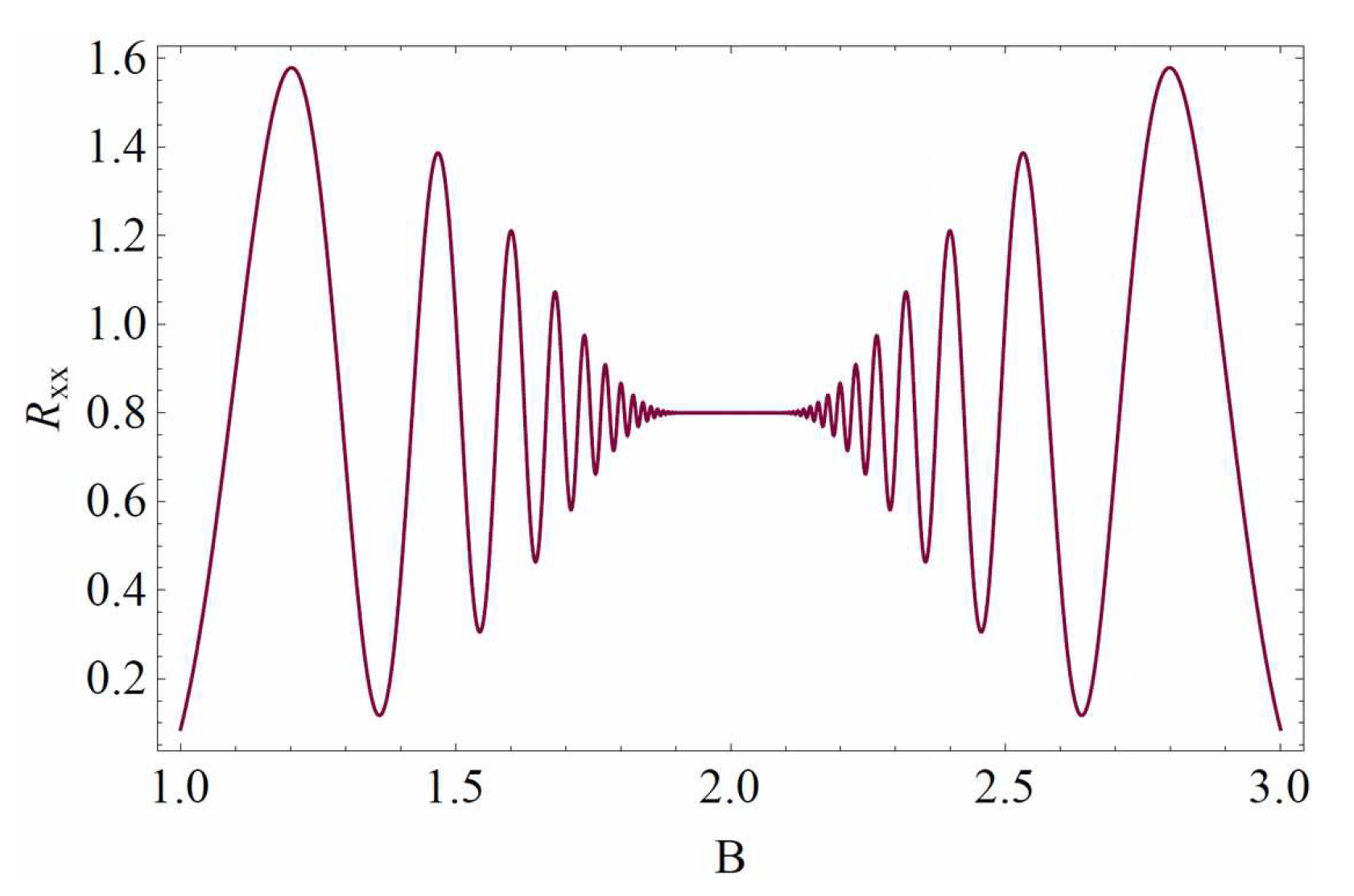

are the initial and final braiding numbers respectively. The resultant edge resistivity decreases approximately to zero when the topological braiding number

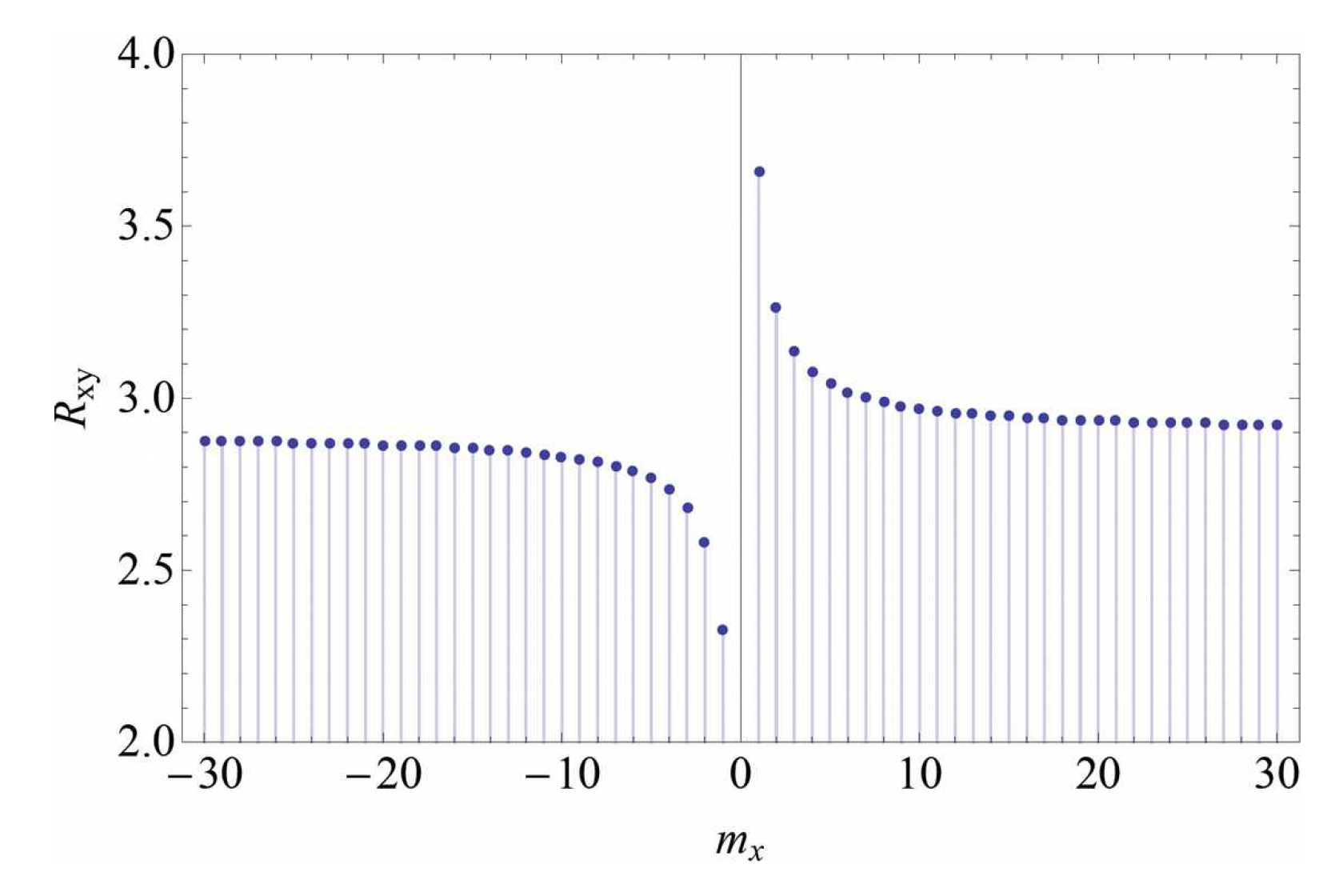

m approaches to 30 as showed in

Figure 18. Every braiding generates a new conducting channel for the electrons in edge zone, the resultant edge resistivity keep decreasing as the number of conducting channels increases. From the point view of hyperbolic geometry, the spatial area of electron fluid lamination expands to infinity as the electrons approach to the horizon boundary of edge zone (

Figure 17c), which corresponds exactly to the outermost boundary line of the edge. The edge space is large enough for electrons to avoid colliding with one another, resulting in zero resistivity.

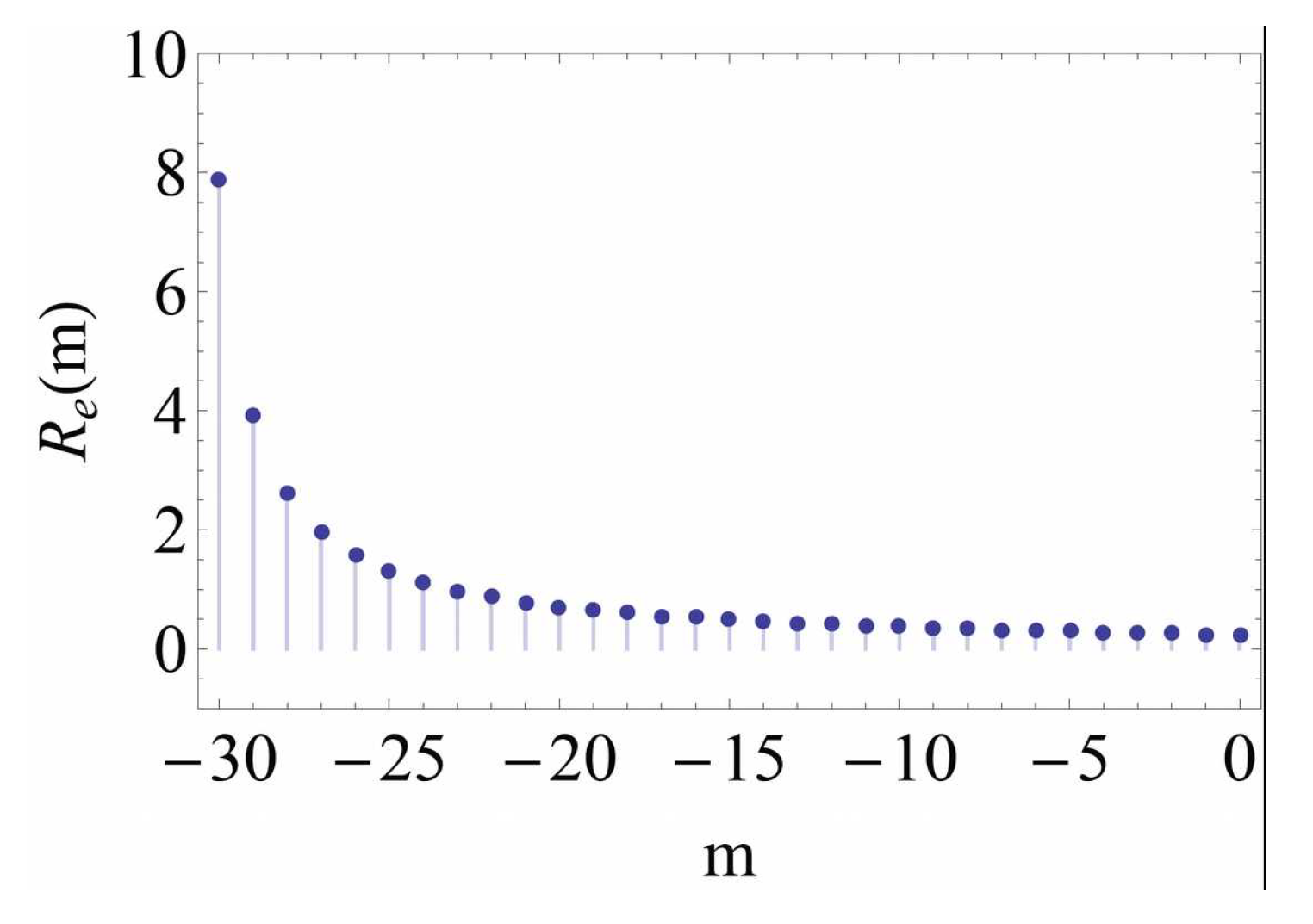

Opposite boundaries of the folded electron fluid lamination can carry different fractional charges, which is determined by the chirality of braiding operations on boundary. In

Figure 16, the middle points of the flux pair is fixed, the left endings of the flux pair is braided in opposite direction to its right endings. The fractional filling factors of train track at the left and the right boundaries are respectively,

In

Figure 16, the filling factor on the rightmost edge zone grows from

to

in the normal direction of the outermost boundary. But the filling factors on the leftmost edge zone decreases from

to

along the normal direction of the leftmost boundary (

Figure 19). The resultant edge resistivity on the left boundary grows to the maximal value as the electrons approaches to the leftmost boundary (

Figure 19). This is because the edge lamination twists in the opposite direction to the motion of electrons. The more closer an electron moves to the leftmost boundary channel, the longer distance it covers a geodesic channel against its forward motion.

2.4. Topological phase transition of folded spin chains

The edge cross section of electric lamination is a train track of electric current, which is equivalently modeled as a compact chain of polarized electrons in high magnetic field. The electric laminar surface propagates as running wave, correspondingly induced a electric current wave sandwiched in between two antiparallel fluxes (as showed in

Figure 22a). The wavy current is straightened to form a one dimensional chain of coupled Ising spins,

where

J is the coupling strength,

B is the external magnetic field strength. There is no electromagnetic interaction between the current bonds connected head to tail in a straight line. When the spin chain folds into a spiral vortex pattern in

Figure 22b, the electromagnetic interacting force between stacked electric current bonds obeys the Bio-Savart law,

Parallel (anti-parallel) current bonds attract (repel) one another. Integrating the force vectors along two independent current bonds yields an effective interacting potential,

This long range interaction results in a one dimensional chain of strongly correlated many current bonds

where

is an effective bond operator with respect to ferromagnetic coupling (

) or anti-ferromagnetic coupling (

) between two nearest neighboring Ising spins (as showed in

Figure 22c).

is dielectric coefficient.

is the length of the current bond.

is the perpendicular distance between the nearest neighboring electric bonds, i.e., the unit lattice space of the one dimensional chain of bonds represented by the diamonds in

Figure 22b.

In one dimensional straight chain of Ising spins (

Figure 22a), all spins gradually align to giving rise to a non-zero macroscopic magnetic moment when temperature keeps dropping to zero. At finite temperature, the fluctuating collective spin configurations equivalently correspond to fluctuating orientation configuration of many current bonds. At low temperature, the nearest neighboring current bonds align to form local ferromagnetic clusters. The collective ordered phase of many current bonds with identical orientation is formed at zero temperature. The ferromagnetic phase of the straight chain of many Ising spins corresponds exactly to a dual antiferromagnetic phase of many electric current bonds in the spiral vortex pattern in

Figure 22b. The spiral vortex of current bonds is incompressible due to the repulsive interaction between nearest neighboring anti-parallel bonds. The total electromagnetic energy of

N antiparallel current bonds reads [

12]

A chain with odd number of current bonds always has lower energy that with even number of bonds (

Figure 23). The collective energy

grows to converge to a limit value when the length of current bond chain increase up to infinity.

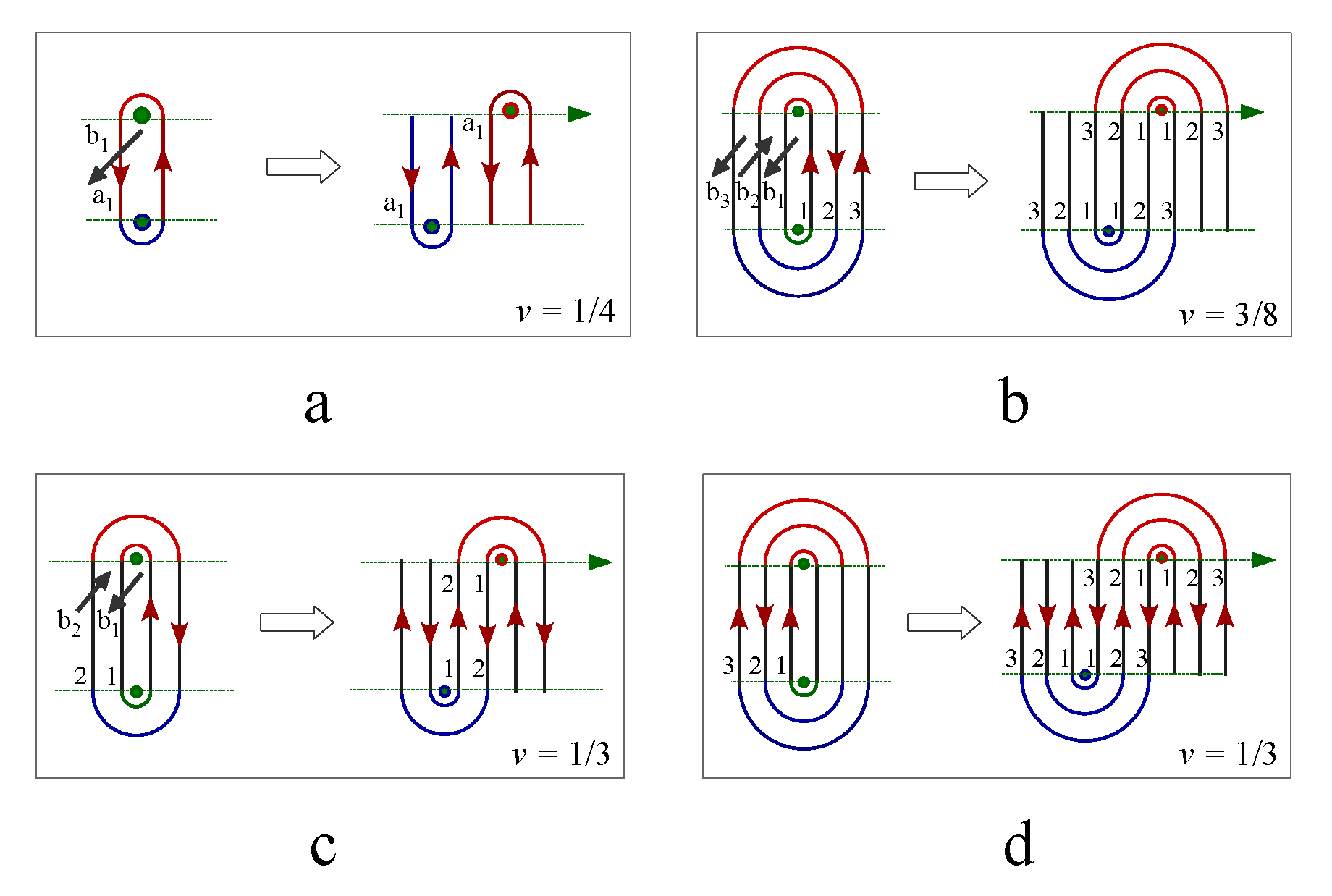

An one dimensional chain with

antiparallel current bonds generates the fractional quantum Hall state with filling factor

.

Figure 22b and

Figure 22d represents the fractional filling states

and

respectively. When the two fluxes in the innermost gaps of

Figure 22c hop outward into the two second innermost gaps, there is no obstacle to prevent the three current bonds sandwiched in between two fluxes from contracting to single bond topologically (

Figure 22d). The train track in

Figure 22d is a topological representation of

state, since there are only two unshrinkable current bonds on the outer side of the two fluxes. The

state is characterized by single unshrinkable current bond on the outer side of the two fluxes (i.e., the leftmost and rightmost side of

Figure 22e). The five current bonds sandwiched in between the two fluxes in

Figure 22e is topologically equivalent to one current bond. Topological contraction of the five antiparallel currents lowers the electromagnetic interaction energy from

to

following Eq. (

108).

The fractional filling factor is characterized by the ratio of winding number of current bonds on the left hand side of

in

Figure 22c-d-e to the winding number of all unshrinkable bonds bridging

and

. In

Figure 22f, when the input point at

winds around

in counterclockwise direction to fuse with the point

right above

, the winding number of the closed loop around

is exactly

. The current bond

bridging

and

winds exactly half of the total phase of the closed loop,

i.e., twice of the topological number of bond

is exactly the winding number,

. Correspondingly, the topological number of the current bond on the right hand side of

is also

. The middle current bond

sweeps over phase

,

The fractional filling factor is a function of topological winding numbers,

The fraction filling factor with respect to

Figure 22f is

. Even though the middle current bond in

Figure 22e is consists of five layers of currents, the phase accumulation along antiparallel path segments canceled each other, the resultant phase accumulation is still

.

The continuity of the winding path around the magnetic fluxes (or singular points) is the top priority for the existence of fractional filling factors as topological invariant. The conservation law of energy or total particle number along the winding path usually changes under topological transformation, thus it is not a sufficient and necessary condition to extract topological character of spin chain. In

Figure 24a, the double core vortex track is pinned down to a square lattice in the presence of two fluxes in the central zone. When the two fluxes move outward away from the central zone and relocate at the outermost gap zone, separated by single track from the free zone, the spiral track on this finite square lattice is a topological representation of

state (In

Figure 24b). A further hopping of the two fluxes to the open free zone results in an integral filling state in

Figure 24c. The winding track in the bulk zone of

Figure 24b (confined by the blue rectangle) can freely winds or shrinks into all possible configurations as long as it keeps its continuity. The shortest path is consists of six spins, isolated the rest six spins out of the spin chain (

Figure 24d). The longest path covers all lattice sites between

A and

B (

Figure 24e). For a spin chain with only the nearest neighboring interactions, all possible paths connecting the lattice site

A in

Figure 24b to the site

B is denoted as

, which leads to

fold degeneracy of the topological state

. A topological transformation is independent of the distance between two points, a physical implementation of topological transformation for spin chain is to established long range coupling between any two lattice sites. In that case, the total number of possible connected paths from

A to

B is

where

counts the possible states of

i Ising spins in the connected path,

and

counts the number of lattice site in

x- and

y-axis.

For the finite middle zone in

Figure 24b, the entropy with respect to

reads

Notice here this entropy

is not topological invariant. The high entropy results in an insulating state of the bulk zone. On the contrary, the entropy of edge tracks is highly suppressed by the two fluxes, leading to superfluid state. The total energy of a path contains

p spins is countable by a long range coupling Ising model

The probability to find

p-path obeys the Boltzman distribution,

The long range coupling interaction is usually smaller than the nearest neighboring coupling interactions, therefore the minimal energy state of the

p-path is the ground state of spin chain with only nearest neighboring coupling. Spontaneous magnetization does not occur in one dimensional chain of many Ising spins. When the one dimensional chain folds to form a spiral vortex pattern covering a two dimensional square lattice, some far separated spins are relocated to become the nearest neighbors, introducing new coupling bonds in extra dimension perpendicular to its original chain. The newly added coupling bonds strengthened the stability of ferromagnetic phase of the original one dimensional chain against thermal fluctuations (

Figure 24f), results in a critical temperature

of spontaneous magnetization, which is predicted by Onsager’s exact solution of two dimensional Ising model,

The critical temperature of spontaneous magnetization in absence of magnetic field is

where

is the average entropy per bond. The critical temperature is proportional to the coupling energy strength

J. The ground state of the folded Ising spin chain is ferromagnetic phase composed of all polarized spins in the bulk zone. In thermal dynamic limit, both the size of bulk zone and the distance between two fluxes grows to infinity, there are large number of inequivalent path configurations even if the path covers the same number lattice sites.

Figure 24e showed exemplar inequivalent paths with the same number of spins. The two inequivalent paths in

Figure 24e becomes indistinguishable in a two dimensional Ising model.

The free energy of the folded spin chain is determined by the energy of the spin chain

and entropy of the folded paths between fluxes

,

The nearest neighboring approximation of the total energy of spin chain in ground state is

. The critical temperature for the phase transition of spin liquid into a ferromagnetic phase obeys

,

Therefore the critical temperature is proportional inversely to the entropy. The fractional quantum Hall state

has the maximal entropy, and the minimal critical temperature of phase transition from normal metal phase to Hall fluid phase.

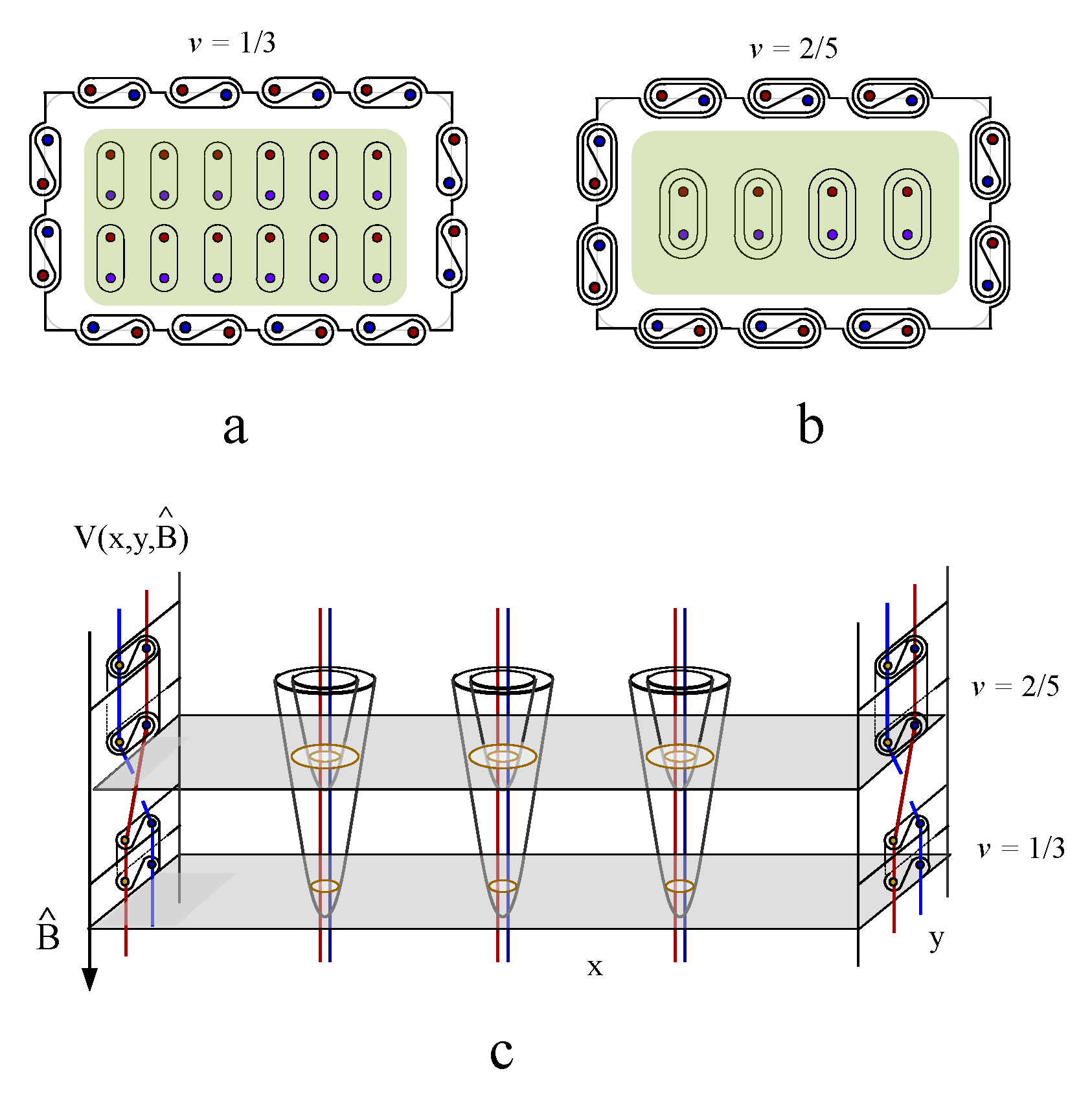

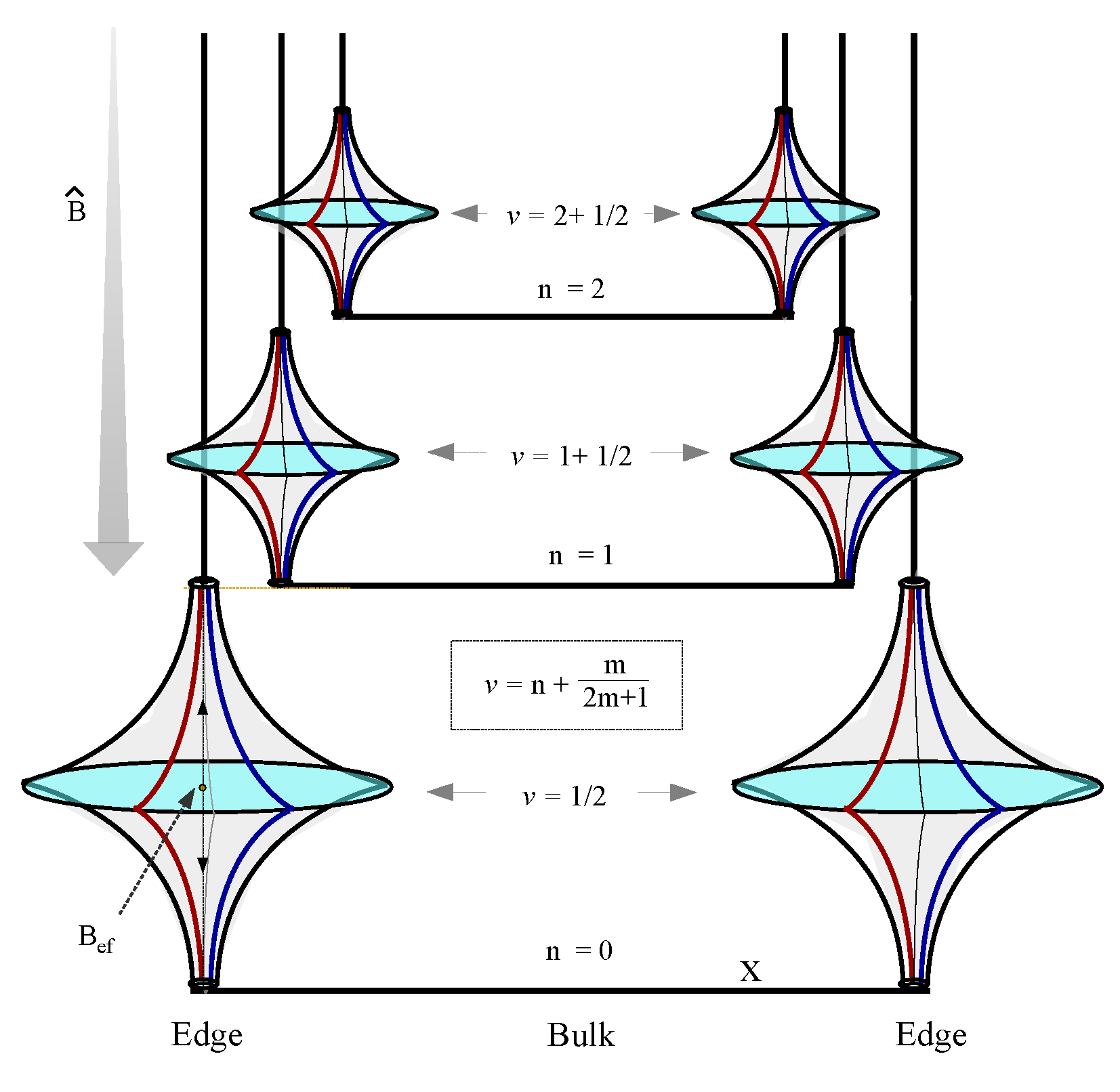

2.5. Fractional quantum Hall effect of topological fluid in vortex lattice

The coupling interaction between two nearest neighboring Ising spins can be effectively represented by a rotating current bond in plane, which corresponds to spin in XY model, i.e.,

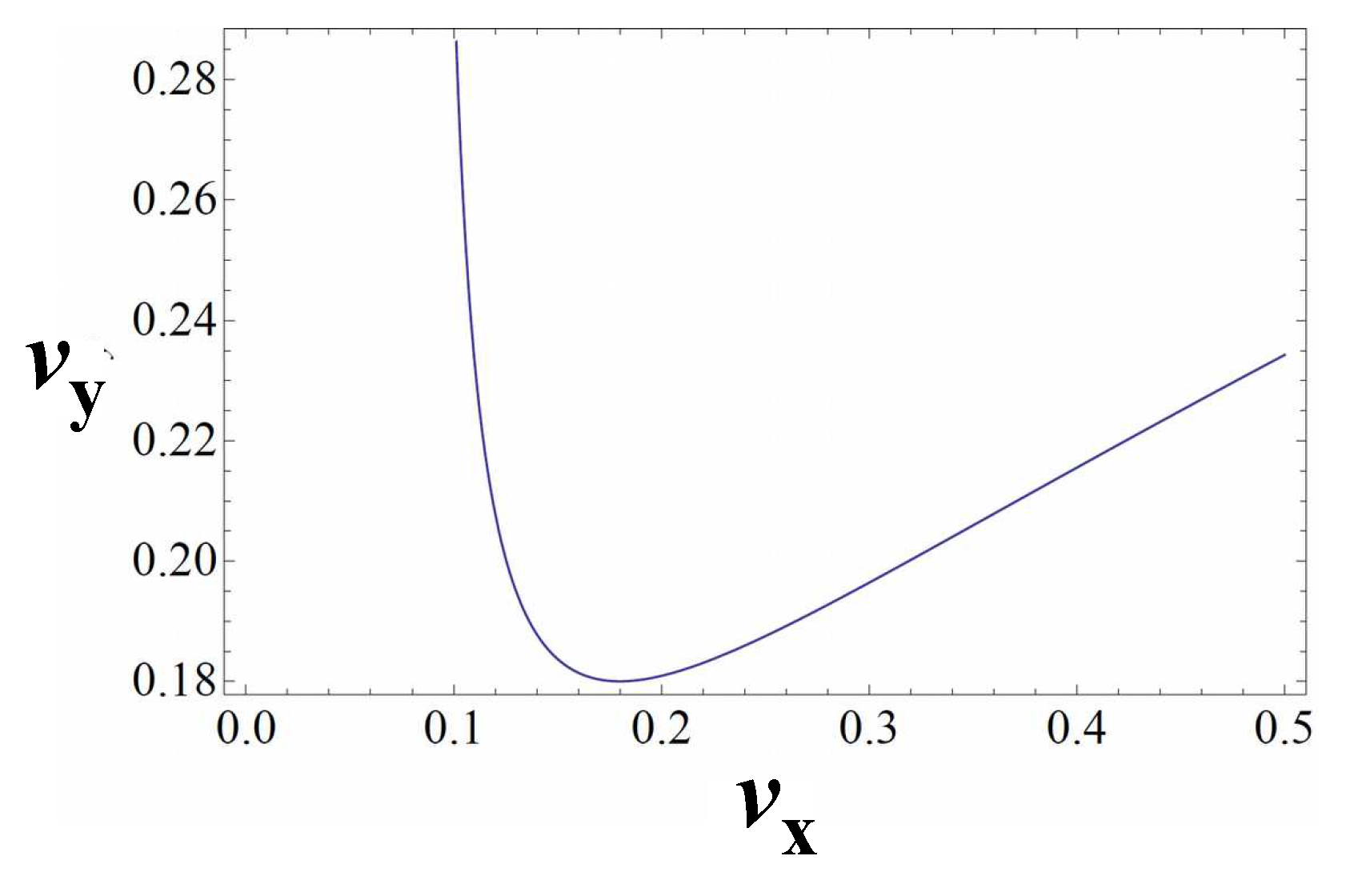

. The total energy of this current lattice is a dual model of 2D Ising model with long range interaction,

If only the nearest neighboring coupling interactions between current bonds are taken into account, the long range coupling model maps to the XY model of many current bonds on square lattice,

A continuous current flowing along the spiral train track requires a small variation of the orientation of current bonds from site to site, i.e.,

. The spiral current track is described by the effective XY-Hamiltonian,

which predicts Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless (BKT) phase transition of vortex. The free energy of a free vortex reduces above a critical temperature

,

where

is winding number of the vortex. Below the critical temperature

, single vortex gains higher free energy and becomes unstable, two vortices prefer binding together to form a pair with lower energy.

When a square lattice of current bonds is immersed in strong magnetic field, the center of square plaquette surrounded by four current bonds is penetrated through by a number of magnetic fluxes

(

Figure 25 ab). The velocity of electrons in the current bonds is generated by the gradient of phase field,

, where

is the phase field without magnetic field,

is phase field generated by gauge potential vector due to the presence of magnetic field. The same (or opposite) gradient of phase field

generates current loops circulating around the two fluxes

and

respectively with the same (or opposite) chirality in

Figure 25a (or

Figure 25b). In a weak magnetic field, the vortices are separated far away from one another. The energy of a vortex around one flux is

, with

L the size of the system and

the unit lattice space. All possible locations of the vortex core in a square lattice with periodic boundary condition is

. Two vortices prefer combining to form a pair below critical temperature

. In a finite system with open boundary condition, the vortex core cannot reach the lattice sites in edge zone unless it splits into two half vortices. The entropy of finite system is smaller than that with periodical boundary condition, leading to higher critical temperature.

Because the distance between two vortices

is smaller than the size of finite system

L, the energy of the vortex pair (

Figure 25ab) is smaller than that of single vortex,

The entropy of unfused vortex pair in

Figure 25ab is approximated by

. The free energy of unfused vortex pair is

The critical temperature

is derived from

,

The distance

between two vortices is larger than the unit lattice space of magnetic fluxes, i.e.,

. When the distance

, the critical temperature of vortex pair

is smaller than that of single vortex. Stable vortex pair exist in the temperature zone

. Below the critical temperature

, the vortex pair prefer binding together to form vortex quaternion.

For vortices with

m layers of concentric current loops around the flux core, the distance between the flux cores of two nearest neighboring unfused vortices in

Figure 25ab is

, the critical temperature of vortex pair reads

The energy of vortex pair grows with respect to a growing number of layers

m, while the corresponding entropy decreases, leading to higher value of critical temperature

. The chirality of circling flow within current loop has strong influence on

. A bosonic vortex is surrounded by

m layers of concentric loop current circling with the same chirality. The vorticity of bosonic vortex is the total winding number of

m layers of concentric loops

A fermionic vortex is surrounded by

m layers of antiparallel loop currents, in which the nearest neighboring loop currents circling with opposite chirality. A fermionic vortex is represented by antiferromagnetic state of many concentric current loops (

Figure 25b). The total vorticity of fermionic vortex is defined by the total topological charge

The

m layers of antiparallel loops generates the winding number

for odd

m, and

for even

m. The vorticity of fermionic vortex is a classical spin that only takes two discrete values

for odd

m. For two vortices with the same vorticity in

Figure 25ab, the antiparallel current segments in the contacting zone repel each other, resulting in positive energy increment in free energy Eq. (

126). While for two vortices with opposite vorticity in

Figure 25ab, the parallel currents in the contacting zone attract each other, generating a negative energy increment in free energy Eq. (

126). Therefore a pair of vortices with opposite winding number has lower energy than that with the same winding number, so does the critical temperature

.

Vortex fusion accompanied by topological change occurs in high magnetic field. The magnetic field can be tuned strong enough to squeeze the two vortex cores (which exactly locate at the center of magnetic flux tube) into one unit plaquette. In that case, unit lattice space between fluxes

is smaller than the unit lattice space

between heavy nucleuses within the crystal lattice. The energy of a vortex is determined by unit lattice space of flux lattice. The current segments in the contacting zone of two vortices with the same vorticity is antiparallel. The high magnetic field reforms the local potential landscape to help the current overcome the potential barrier generated by the repulsive interaction between antiparallel currents in the contacting zone. These antiparallel current segments annihilate one another, and unit the rest segments to generate larger concentric loops flowing only in the outer zone of the flux pair (

Figure 25a). The large vortex with double flux core has lower energy than the two initial separated vortices. The swirling electron fluid during vortex fusion is compressible quantum fluid under strong magnetic field, however the effective repulsion between fermions due to Pauli exclusion principal provides a counterbalance interaction to prevent the concentric current loops from overlapping one another. The flow field around each flux of the double core vortex in

Figure 25a carries fractional winding number

. The energy of the double core vortex is

which is smaller than the energy of binding pair of two separated vortices with integral winding number. The energy of single core vortex

diverges when the system size reaches thermal dynamic limit. However the vortex pair has finite energy

limited by the distance between the cores of two vortices, carrying smaller energy than that of single core vortex. For the case of two vortices with opposite vorticity, the current segments in the contacting zone is parallel, the neighboring parallel currents attract one another and finally fuse into one to reduce the total energy of vortex pair. Since the energy barrier between the two opposite vortices is rather small, it takes a weaker magnetic field to push them into smaller unit cell and fuse into one. The effective energy increment of two opposite vortices above single vortex is smaller than that of two identical vortices. The effective magnetic field strength

is proportional inversely to the distance between the cores of two nearest neighboring vortices,

A weaker magnetic field generates vortex with larger radius as well as higher number of layers

m. In the opposite case, a stronger magnetic field reduces the energy of a double core vortex, resulting in lower critical temperature.

A square lattice of many vortices with identical vorticity is unstable (Fig

Figure 25a). The antiferromagnetic vorticity state of many vortices is a stable phase due to the attractive interaction between parallel current segments between neighboring vortices. For a square lattice composed of many fermionic vortices in antiferromagnetic order (Fig

Figure 25b), a dislocation of flux lattice is favored by energy reduction. To keep the continuity of the fused current within every current loop, the magnetic flux

together with the semicircular currents in

Figure 25b translate to the right hand side by one step and reconnect to the currents around

, generating a continuous spiral current pattern without flow orientation frustrations. The total energy of the spiral current track

is lower than that of two fermionic vortices according to the long range-coupling energy Eq. (

121), because the distance between anti-parallel current segments grows larger during the dislocation of magnetic fluxes. The spiral current in

Figure 25b generates a stable collective phase of incompressible fluid due to the diverging repulsive interaction between antiparallel currents. The spiral currents generated by dislocation has lower energy than vortex lattice. This dislocation mechanism is equivalent to the hopping of one flux to the other side of current and braiding with with its original nearest neighboring flux. Two opposite fermionic vortices contributes opposite winding numbers, hence the total winding number of the vortex pair is zero. After the dislocation of magnetic flux lattice, the winding number around flux

(and

) is

(and

), the total winding number of the spiral current is still zero,

. Therefore winding number is not sufficient enough to distinguish the two topologically different states in

Figure 25b.

The double core bosonic vortex generated by fusing two bosonic vortices in

Figure 25a is equivalent to single core bosonic vortex with renormalized magnetic flux,

The unit lattice space is also renormalized as

. In thermodynamic limit, the spatial size of lattice grows to infinity, the same BKT phase transition also occurs for double core bosonic vortices at the same critical temperature Eq. (

124) (

Figure 25a). Two double-core bosonic vortices prefer binding together to form a tetra-core vortex below the critical temperature

. The vortices keep fusing until all bare fluxes gathered together and are enveloped by

n layers of parallel current loops flowing along the edge, resulting in gapless states with respect to integral quantum Hall effect with filling factor

n. The bulk zone is filled by a forest of bare magnetic fluxes without any currents. Conducting electrons are fully confined in the edge zone. The collective condensation of many bosonic vortices phase fulfills integral quantum Hall state and topological insulator state. The vortex fusion of two double core fermionic vortices occurs by connecting two neighboring spiral tracks head to tail, one of flux pair in the center of a spiral track falls in the same domain as another flux of the other flux pair, the two fluxes can be renormalized as new flux

The length of the spiral track also renormalized as

. The fusion of fermionic vortex leads to continuous open current tracks crossing the whole lattice, which represents fractional quantum Hall states.

The collective phase transition from localized vortex pair state to an extended state represented by an open spiral track in

Figure 25b is obviously a topological phase transition, which can be characterized by Euler number of graph of current tracks. Dislocation of magnetic flux lattice creates many open docking points on edge. Different boundary conditions are defined by different docking patterns. For example, the spiral vortex lattice in

Figure 25d has 13 docking points on its four edges. The periodical boundary condition is defined by connecting the

ith docking point on the upper boundary to the

ith docking point of the bottom boundary. The same periodical boundary condition is defined to connect the docking points on the left and right hand side in

Figure 25d. The whole vortex lattice is composed of four localized vortices surrounded by three layers of current loops, and a loop of spiral vortices connected head to tail at the 7th docking point in

Figure 25d. The spiral loop on torus is equivalent to a boundary enveloping four bosonic vortices in the bulk, generating fractional charges

for fractional quantum Hall state. The bulk filled by localized vortices is in insulating state.

Landau’s symmetry breaking theory of phase transition provides a basic understanding for the phase transition from disordered vortex phase to ordered vortex phase. The square vortex lattice in

Figure 25c can be constructed by either bosonic vortex or fermionic vortex. Every vortex generates a local magnetic momentum, which is equivalent to a macroscopic spin. In an extremely high magnetic field, the local magnetic momentum of all electric current loops are polarized in the same direction, generating ferromagnetic phase of bosonic vortices. In weak magnetic field and low temperature environment, the orientation of electron flow within local current loop fluctuates to align with external magnetic field and reduce its local potential energy, driving the collective phase of vortex lattice into ground state. A vortex at the

ith lattice site is represented by an effective vorticity

which is measured by winding number

. The total energy of all vortices on the vortex lattice is summarized as

where

is the distance between vortices (or anti-vortices).

is external magnetic field in

z-axis. For a lattice of many separated vortices, the strongest coupling interaction is assumed to occur between the nearest neighbors. The long range coupling potential

is approximated by constant term

with

the unit lattice space of vortex lattice. Each of the

m layers of concentric orbital around the double core of vortex contributes a vorticity

. If the phase field of the loop orbital fluctuates in thermal environment, the vorticity of certain loop orbital also fluctuates between

. The possible values of vorticity for

m layers of loop orbital are

.

represents bosonic vortex, while

corresponds to fermionic vortex.

The Hamiltonian Eq. (

133) of vortex lattice is equivalent to Heisenberg model for large spins, which is not exactly solvable. In a mean field approximation, the local vorticity is assumed to has a small deviation away from average vorticity

, i.e.,

. The vorticity of vortex lattice is defined in a similar way of magnetic momentum of spins,

where

N is the total number of vortices. The mean field approximation of Hamiltonian Eq. (

133) reads

where

is the absolute value of vorticity.

p is the total number of the nearest neighbors. The effective magnetic field is denoted as

The eigenenergy of the effective Hamiltonian

take a serial of discrete values,

. The partition function sums over all possible vorticity values,

The vorticity is derived from the partition function in a straightforward way,

A self-consistent solution of the transcendental Eq. (

138) is derived under the first order approximation, which outputs a critical temperature in absence of external magnetic field

,

Below the critical temperature

, the vorticity obeys a power-law growth with respect to a decreasing temperature,

Most vortices are aligned to the same direction due to spontaneous breaking of time reversal symmetry. The maximal vorticity is proportional to

at zero temperature. For large vorticity

, the total number of the nearest neighboring parallel current loops is larger than that of antiparallel loops. All vortices are bosonic vortices at zero temperature.

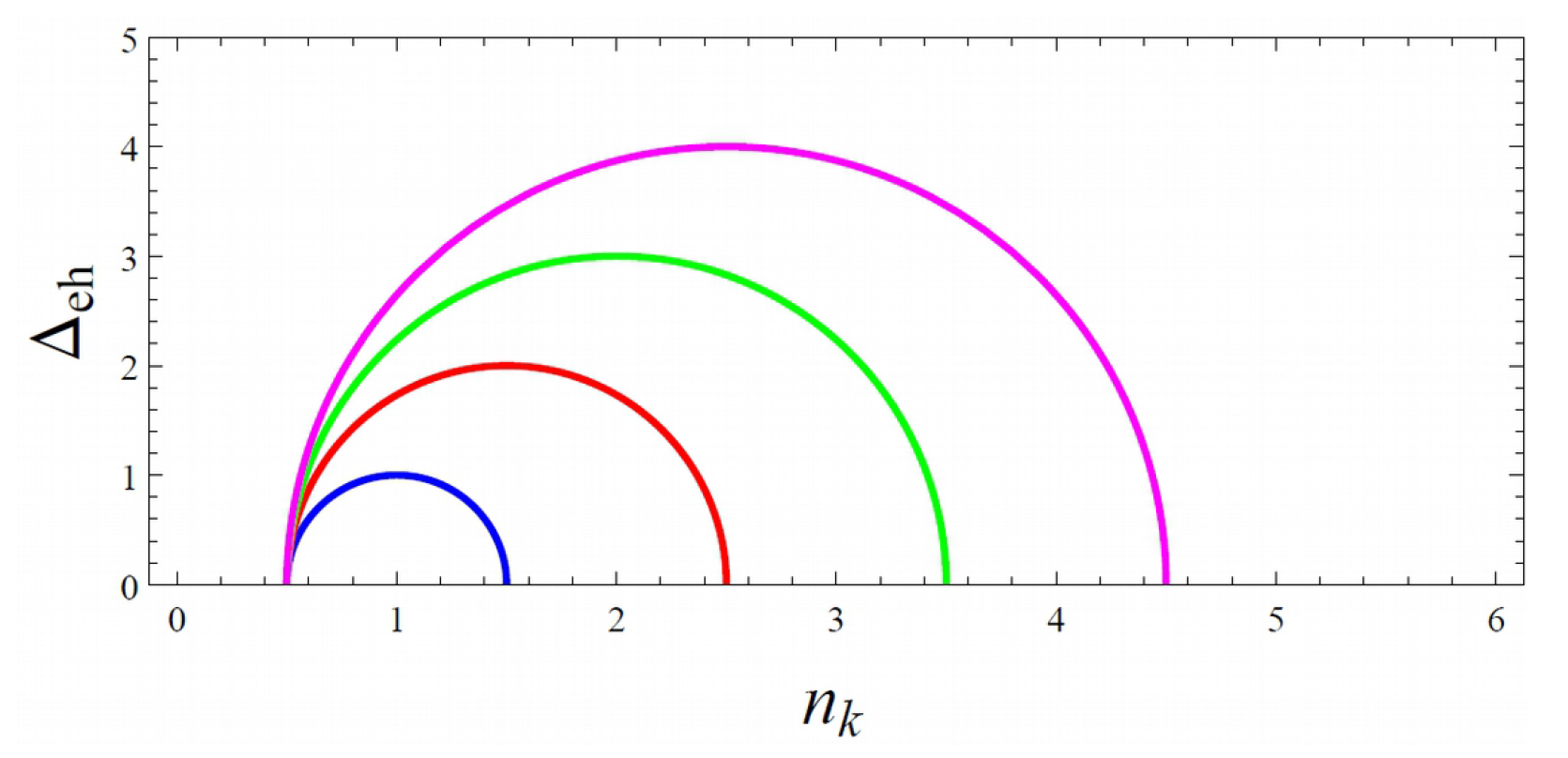

For

, all vortices are spontaneously polarized into fermonic vortices below the critical temperature Eq. (

139), which is consistent with Onsager’s exact solution for two dimensional ising model,

The distance between two vortex cores is

. Notice the spontaneously ordered vortices above are still individual vortices, they are not paired up to form highly ordered state. In the antiferromagnetic phase of many fermionic vortices with double cores, a collective dislocation of magnetic flux lattice occurs to drive the vortex lattice into lower energy state. The

m current loops around double flux core are cut into halves and reconnected to generate spiral current tracks, generating the spiral vortex chain with fractional charge

. These spiral chain is formed by spiral vortex fusion in the edge zone. The spiral vortices connected to one another head to tail to form a closed loop along the edge. All possible locations of the spiral vortex on edge is

. In mind of the internal degree of freedom of spiral vortex, the total number of possible internal state is proportional to

m. As a result, the entropy of the spiral vortex loop in edge zone is

. The effective critical temperature with respect to fractional quantum Hall state with filling factor

reads

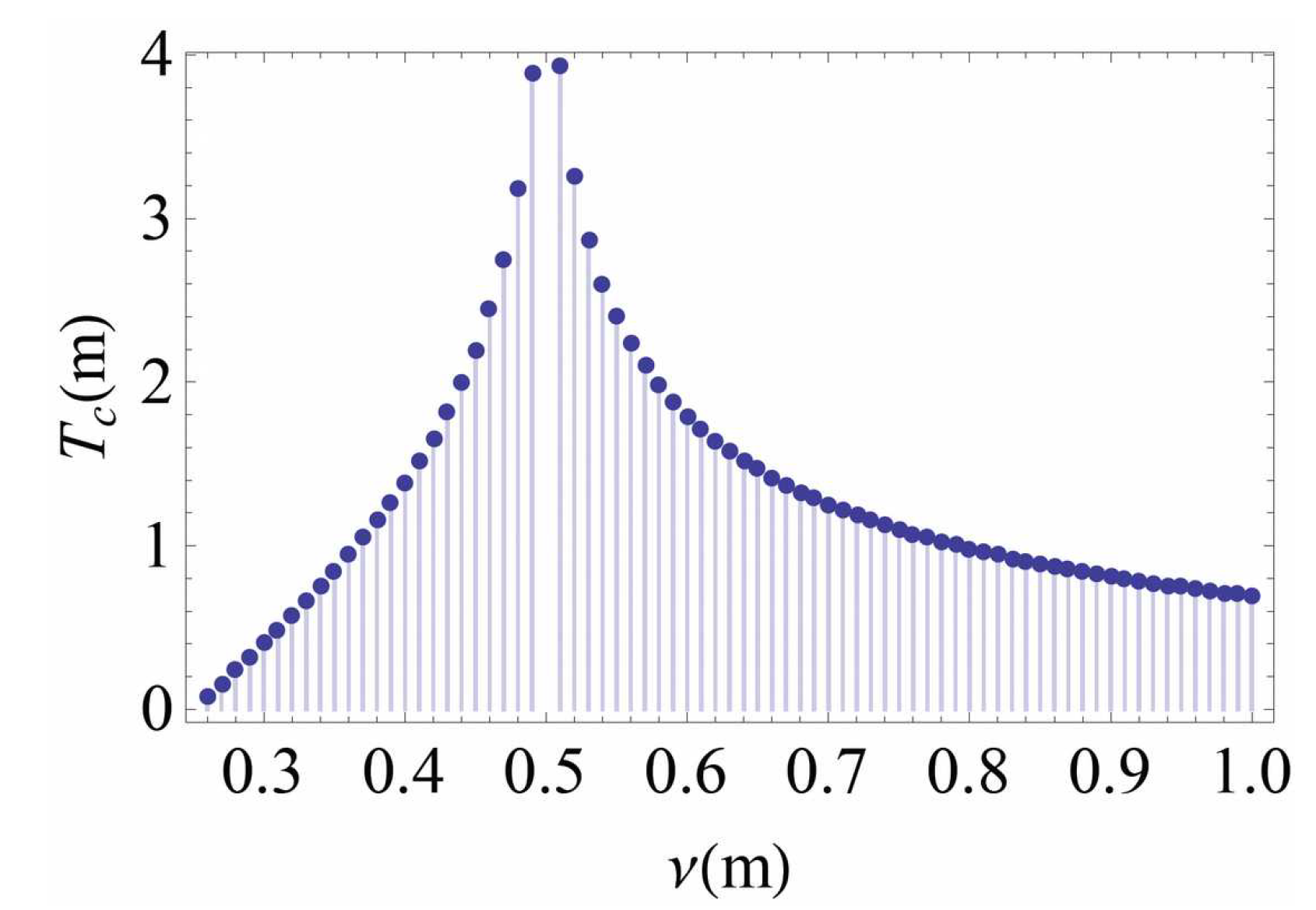

increases with respect to an increasing

m as well as

below half-filling state c (

Figure 26), and decays with respect to growing

.

diverges at half-filling state

, where the energy gap between landau levels approaches to zero, and effective magnetic field is also zero. The electron fluid is in a normal metal state in thermal environment at

. The fractional Hall state

has the lowest critical temperature. A growing system size

L further reduces the effective critical temperature.

The half-filling factor

is a critical point of the effective magnetic field, at which its orientation reverses from

to