1. Introduction

The commercialization of secondary lithium metal batteries holds significant promise for advancing energy storage technologies due to their high energy density and specific capacity. However, the current issue hindering their widespread adoption is the formation of lithium dendrites during charging, which can lead to short circuits and thermal runaway [

1]. This challenge is being very actively addressed by exploring strategies to prevent dendrite growth, such as employing electrolyte additives [

2,

3,

4,

5], designing innovative anode surface modifications [

6,

7,

8,

9], using mechanical stress [

10], as well as exploring new charging procedures [

11]. Along with that, simulation models, that grant a deeper understanding of the electrodeposition process, are constantly evolving [

12]. Successful mitigation of dendrite formation would result in safer, more efficient lithium metal batteries, potentially revolutionizing the energy storage industry and enabling the development of longer-lasting and more powerful portable electronic devices, electric vehicles, and large-scale energy storage systems.

Dendrite growth in lithium metal batteries is influenced by a combination of electrochemical and mechanical factors. At low current densities, lithium tends to grow from the base due to plastic flow of lithium, while at high current densities, growth occurs at the tip driven by the electric field [

13]. The process begins with the nucleation of lithium, which then grows into elongated dendritic structures. A thin layer, called the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI), which is made up of various inorganic and organic compounds, inevitably forms on the lithium surface as a result of electrolyte breakdown. The growing structures experience stress due to molar volume changes and interaction with the SEI. Stress distributions within the dendrite lead to different growth behaviors: compressive stresses at the base promote vertical growth, while localized stresses at the tips cause branching and bifurcation. The electric field and thus the current density is higher at the dendrite tips, enhancing tip growth and leading to high electric fields and current densities that further drive uneven electrodeposition [

12,

13]. Six growth regimes have been identified—thermodynamic suppression, incubation, base-controlled, tip-controlled, mixed, and Sand’s regime—each characterized by specific current density and size-dependent behaviors [

13]. Understanding these regimes and the underlying electrochemomechanical interactions is crucial for developing strategies to suppress dendrite growth, thereby enhancing battery safety and performance.

The models for dendrite growth can be roughly divided into three categories: Brownian statistical models, electromigration-based models, and surface tension models. The Brownian statistics model family for dendrite growth simulations focuses on the random, stochastic movement of lithium ions and their deposition on electrode surfaces. These models simulate the Brownian motion of particles, incorporating probabilistic rules to determine ion interactions and deposition events. By modelling the random walk of ions influenced by thermal energy and electric fields, Brownian statistical models provide insights into the nucleation and growth of dendritic structures. For example, Aryanfar et al. (2014) explored dendrite growth using both pulse charging experiments and Monte Carlo simulations, finding that pulse charging could disrupt continuous growth and promote uniform deposition [

14]. A study by Magan et al. provides a detailed explanation of how the surface reaction kinetics affect the resulting size distribution of the interfacial nanostructures after deposition [

15]. Chen et al. (2023) investigated the impacts of initial nucleation spacing, surface energy anisotropy, and interfacial electrochemical driving force on dendrite growth, concluding that smaller nucleation spacing and lower surface energy anisotropy inhibit dendrite formation and promote smoother deposition [

16].

The Chazalviel’s model describes lithium dendrite growth under high current densities, emphasizing electromigration and space charge effects. When current density is high, lithium-ion concentration near the electrode drops to zero at Sand's time, leading to a build-up of positive charge and a localized electric field. According to this model, dendrite tips grow at a rate similar to the anion drift velocity, highlighting the critical role of ion concentration gradients and electric fields in dendrite formation. The work of Chazalviel provided a theoretical framework for electromigration-limited dendrite growth, showing how high current densities lead to a depletion of lithium ions and subsequent space charge formation [

17]. Later, the influence of electrolyte motion, variation of ion mobility and diffusivity with ionic concentration as well as the effect of polarization cycling have been recognized as necessary improvements of the model [

18].

The Surface Tension Model explains lithium dendrite growth by emphasizing the balance between surface forces and mass transport. The study by Barton and Bockris discusses the role of surface effects in the formation and growth of dendrites during the electrolysis process. They found that the presence of surface roughness and defects on the electrode can significantly influence the initiation of dendrite growth. These irregularities can act as preferential sites for nucleation, where the local electric field is enhanced, promoting the deposition of metal ions [

19]. A paper by Monroe and Newman models dendrite growth in lithium/polymer cells, showing that dendrite propagation accelerates with time and current density, leading to cell shorting at current densities above 75% of the limiting current. Increasing interelectrode distance and lowering current density can delay failure, but surface forces and transport properties have minimal impact on growth under the studied conditions [

20].

Various advanced in-situ and operando imaging techniques have been utilized to characterize dendrite growth. Optical microscopy, due to its accessibility and simplicity, allows real-time observation of lithium dendrite formation, though it is limited by spatial resolution. Confocal Raman microscopy provides insights into Li-ion concentration gradients and dendrite formation with sub-micron spatial resolution but struggles with poor temporal resolution [

21]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) offer high spatial resolution imaging of dendrite structures and the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), although electron microscopy requires vacuum conditions and can introduce beam damage [

22,

23]. X-ray-based techniques such as X-ray contrast imaging enable non-destructive, high-resolution imaging of dendrites within opaque materials [

24]. Neutron imaging, while less common, provides depth profiling and three-dimensional (3D) visualization of dendrite growth [

23]. Additionally, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been employed to study the structural and dynamic aspects of dendrite growth [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Despite the low temporal and spatial resolution of MRI for dendrite characterization, its major benefit is its non-invasive nature, requiring only that the battery housing be non-metallic. Each technique presents unique advantages and limitations, collectively contributing to a comprehensive understanding of lithium dendrite growth mechanisms.

In this study, a simulation model of dendrite growth on a lithium metal electrode is presented. The model is based on a diffusion-limited simulation to estimate the most likely locations of new growth according to the deposition-limited (Sand’s) regime of electrodeposition, where growth is tip-controlled. A single particle diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA) deposition model with a bias towards the electric field is implemented. DLA describes the process by which particles undergoing random motion (Brownian motion) aggregate to form fractal structures, making it a specific type of Brownian dynamics model [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. The simulation was calibrated and the accuracy of its predictions was evaluated based on the actual results of dendrite growth during charging of a lithium symmetric cell, which was measured by sequential 3D MRI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

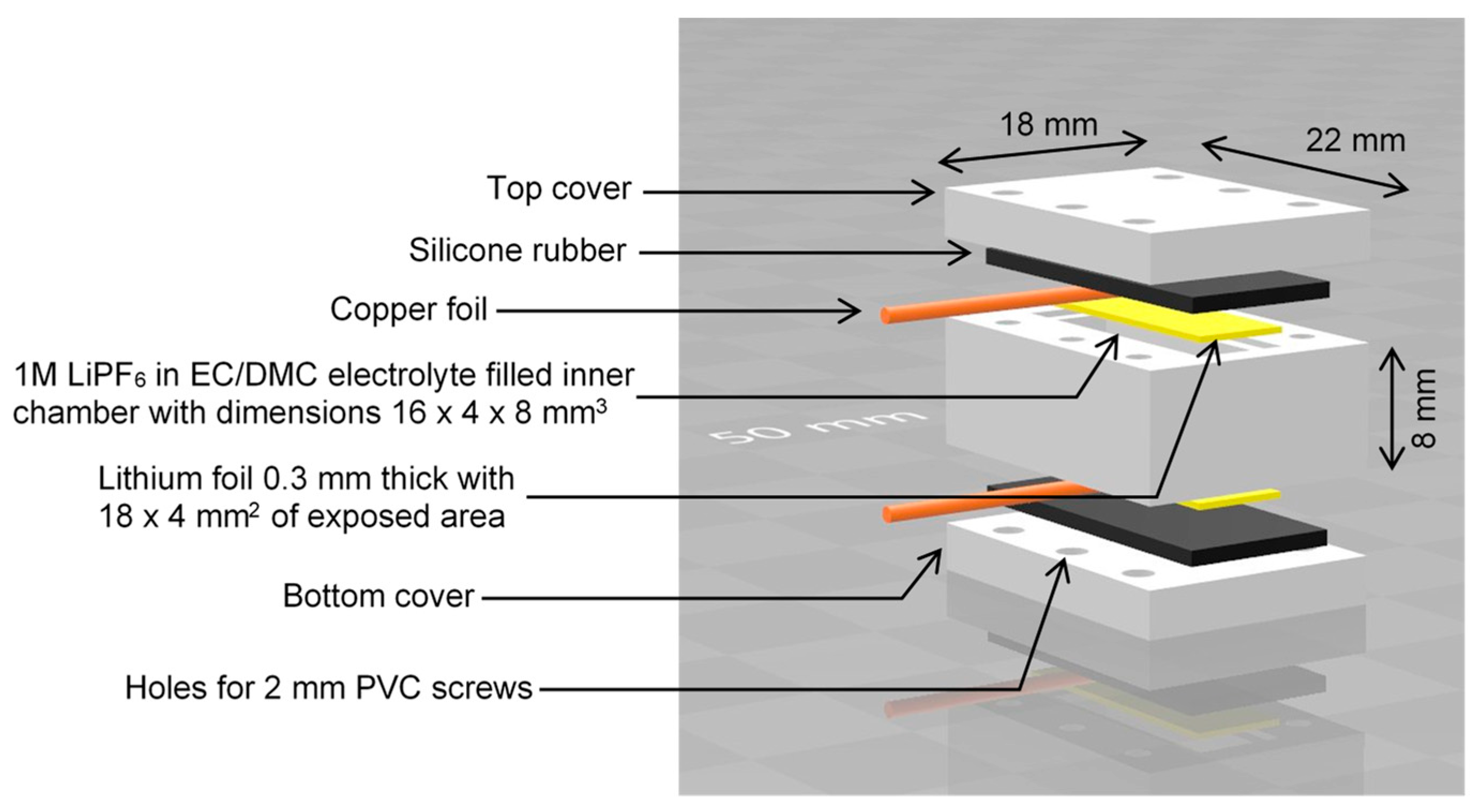

The model battery (lithium symmetric cell) was designed and assembled according to the scheme in

Figure 1. The battery body components were fabricated from PEEK plastic. For the electrodes, two rectangular 0.3 mm thick lithium metal plates were cut from a roll of lithium foil. During assembly, the two electrodes were inserted into the recess provided for this in the main block, then covered with strips of a copper foil which were used as current collectors, covered with silicone rubber gasket and finally pressed from both sides to the main block with covers screwed on. This cell was then filled with electrolyte through a small hole in the side, which was later sealed. The electrolyte was a solution of 1 M LiPF

6 in a 1:1 volumetric mixture of ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC). Battery assembly was performed in an argon-filled glove box (Vigor Gas Purification Technologies, Marktheidenfeld, Germany). Before inserting the battery into the MRI magnet, it was connected to a constant current source.

2.2. MRI Experiments and Image Processing

The MRI experiments were performed using a 9.4 T (400 MHz proton frequency) wide-bore vertical superconducting magnet (Jastec, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Bruker Micro 2.5 gradient system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany), which was controlled by a Tecmag Redstone spectrometer (Tecmag, Houston, TX, USA). Data acquisition was performed with a 30 mm quadrature Bruker 1H RF probe operating in linear polarization mode.

For optimal MR imaging, the cell was aligned inside the magnet so that the B0 and B1 magnetic fields were parallel to the electrode faces. 1H MR imaging of the battery was performed using a 3D RARE sequence with the following parameters: inter-echo time (inter-TE) of 5.8 ms, repetition time (TR) of 2030 ms, and echo train length (ETL) of 8. The field of view was set to 20 × 10 × 5 mm3 across the x, y, and z axes, with a 128 × 64 × 32 signal acquisition matrix in the following directions: read (x), first phase (y), and second phase (z). This setup yielded a 3D image that encompassed both electrodes and the electrolyte region, with an isotropic resolution of 156 μm.

Dendrite growth began concurrently with the start of MR image acquisition, maintaining a constant charging current of 1 mA throughout the experiment, with an upper voltage limit of 4.0 V. Each image acquisition lasted approximately 2 h and 20 min, followed by a 1 h pause before starting the next image acquisition. In total, 10 sequential images were acquired, which corresponded to an experiment time of 33.3 h.

The MR signal originates from the hydrogen atoms contained in the electrolyte [

26], while the dendritic structure and other parts of the battery (housing, electrodes, leads...) do not produce an MR signal, as they do not contain hydrogen atoms. In addition, there is a number of interactions between the metallic dendrites and the electrolyte, such as magnetic susceptibility and RF shielding effects, which lead to a reduction of electrolyte signal. These complex interactions make it difficult to gauge the intensity and reach of each individual interaction, which means that the "signal void" does not necessarily represent the true shape of dendritic structures, but only gives us a rough estimate that is generally larger than the actual dendritic structure [

34].

The first step in image processing was to extract the 3D structure of the dendrite growth from the MR images. Initially, irrelevant areas of the images were trimmed to retain only the volume corresponding to the electrolyte region inside of the cell. Binary filtering was then applied using inverted thresholding, where voxels with values below the selected threshold intensity were assigned a value of 1, these voxels represented dendrites, and other voxels were assigned a value of 0 and represented other parts of the battery. These binary images were then manually corrected slice by slice for each 3D image to address potential artefacts, gas bubbles or other image imperfections.

2.3. Numerical Simulation

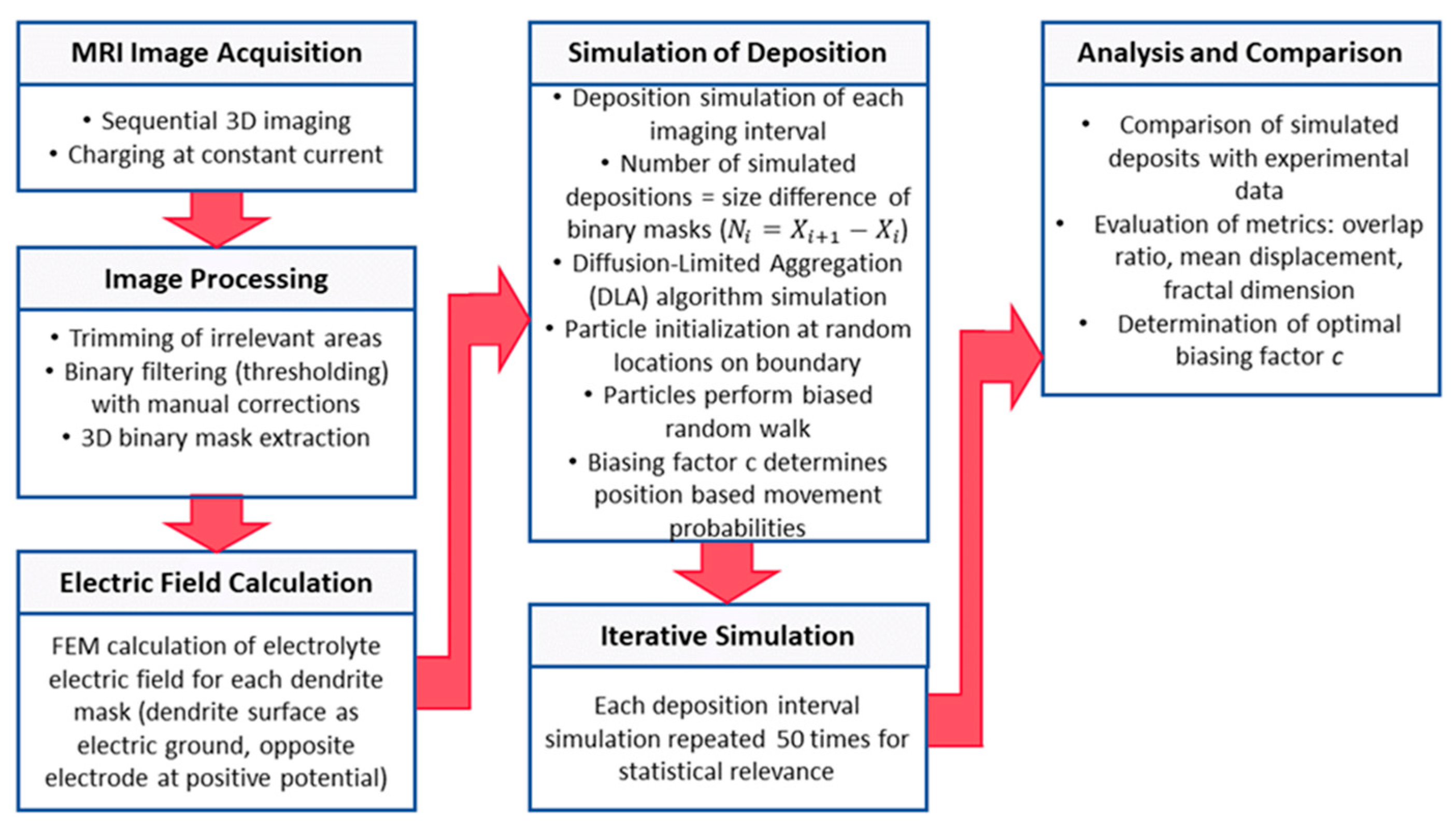

The simulation of dendrite growth followed the protocol shown in the diagram in

Figure 2. Briefly, a sequence of ten 3D MR images was acquired first. These images were then used as a guide to simulate each of the nine deposition intervals, which were simulated in nine independent simulation steps using the same model but with different initial conditions. For each step, deposition sites were extracted. To increase statistical relevance of the calculated deposition sites, each of the nine simulation steps was repeated fifty times. The simulation was performed on a grid representing the inside of the symmetric cell, with voxel dimensions matching those from MRI imaging (156

3 μm

3). Given the cell size of 16×8×4 mm

3, the grid size was 102×51×26.

Initial conditions for each simulation step were set based on binary 3D masks of dendrite structures extracted from MR images, labelling nonzero voxels as dendritic. First, the electric field was calculated for each 3D dendritic mask, with the surface of the dendritic electrode set as electric ground, while the opposing (flat) electrode surface had positive potential, and the surrounding walls were modelled as electric insulators. The current-to-next image deposition simulation used the initial conditions and the calculated electric field from the corresponding 3D dendritic mask. The duration of the simulation step was set proportional to the difference in the number of voxels between the next and the current 3D dendritic mask. The simulation stopped when the required number of voxels were filled with dendrites. A Diffusion-Limited Aggregation (DLA) algorithm was then used to initialize each particle (dendritic voxel) at a random location on the domain boundary opposite the deposition electrode. The particles were subjected to a biased random walk, with the biasing factor

c determining the degree of bias against the electric field. If

c is 0, the walk is unbiased (random); if

c is 1, the particle moves only in the direction of the electric field. Motion probabilities were calculated from the electric field using the following equations:

Here, is the electric field vector, is the electric field vector component of the normalized vector, and and are the motion probabilities of the particle in the positive and negative i direction, respectively. The simulation was performed for biasing factors c in the interval from 0 to 0.9 in steps of 0.1. For the purposes of statistical relevance for result analysis, each individual simulation was repeated 50 times. This gives a total of 4500 simulation runs (9 time intervals, 10 c-values, 50 repetitions). The optimal factor c was determined as the one that yields the best match between the dendrite structures in the experiment and in the simulation, measured using two different metrics.

The first (overlap,

o-value) metric is quite straightforward and is equal to the number of simulated deposition sites that overlap with the deposition sites measured by sequential 3D MRI (

No), divided by the number of total deposition events (

Nd).

The second (mean displacement,

s-value) metric is more complex. It corresponds to the mean displacement of the simulated deposition sites from the measured (actual) deposition sites. Specifically, for each measured deposition site, the distance to the nearest simulated dendritic voxel (

di) is measured and normalized to the largest distance in the cell (space diagonal -

ds). These values are summed and divided by the total number of measured deposition sites (or of simulated ones, as this is identical). This metric provides a more comprehensive assessment of the simulation accuracy. For instance, even if the overlap fraction is low, the deposition sites might still be relatively close to the measured locations, indicating reasonable accuracy.

In addition to the previously mentioned two metrics, dendritic structures, simulated and measured, were evaluated also by the fractal dimension metric, which describes the complexity of a fractal pattern. In the context of dendritic growth, the fractal dimension provides insights into the branching nature and geometric complexity of the dendrites. The box-counting method was used to calculate the fractal dimension [

35]. For each 3D binary representation of dendritic growth, the algorithm started by counting the number of occupied voxels with unit-sized boxes. The box size was then incrementally increased by one voxel until it matched the smallest side of the simulation domain. For each box size

ϵ the number of occupied boxes

N(

ϵ) was recorded. These values were plotted on a log-log scale

vs.

. The fractal dimension

D was determined by fitting a linear regression to the log-log plot, with the slope of the regression line providing the fractal dimension:

The authors of the study programmed the simulation in the Python programming language. Calculations of the electric field and current density were performed using the COMSOL Multiphysics software (Stockholm, Sweden). All simulations were performed on a standard PC.

3. Results

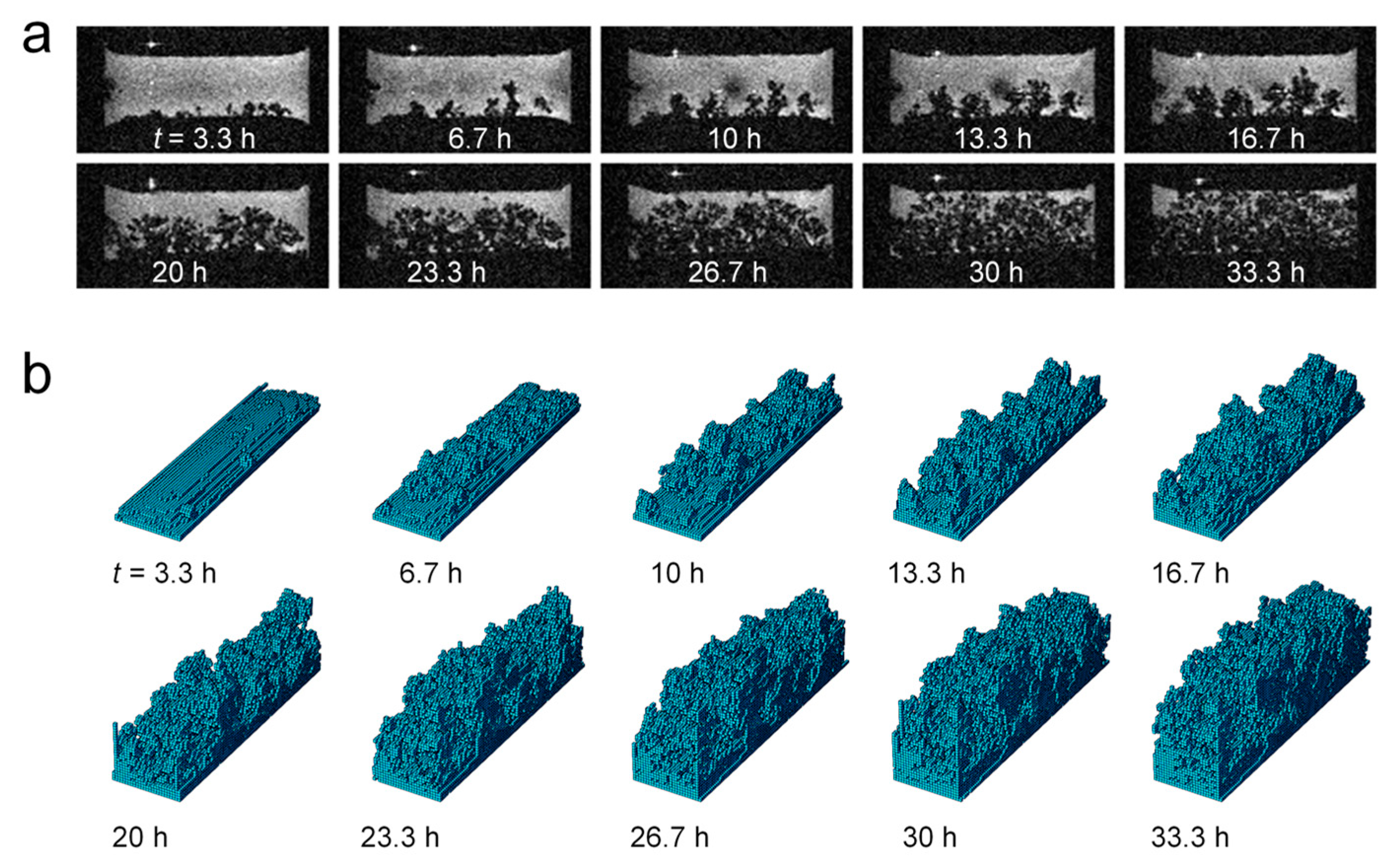

The entire dendritic structure can be optimally visualized by analyzing evolution of the 3D binary mask extracted from MR images of the battery. Images in

Figure 3a show the growth of dendrites in the central slice across the battery from 3.3 h (first image) to 33.3 h (last image) after the onset of battery charging. At 3.3 h, the electrode surface is visible with almost no dendritic growth. It appears, that the electrode is slightly convex. At 6.7 h, the initial stages of dendritic growth are observable in the form of peaks, with minimal to no branching. As time progresses, more substantial branching and growth are evident. This pattern continues with the dendrites becoming more extensive and complex over the subsequent hours. Rapid growth is noticeable up to 26.7 h, and then with further growth the density of the structure only increases. By 30 h, the dendritic growth is substantial, nearly filling the available space, and at 33.3 h, the growth appears to have reached a highly complex and dense state. This progression highlights the continuous and extensive development of dendritic structures over time.

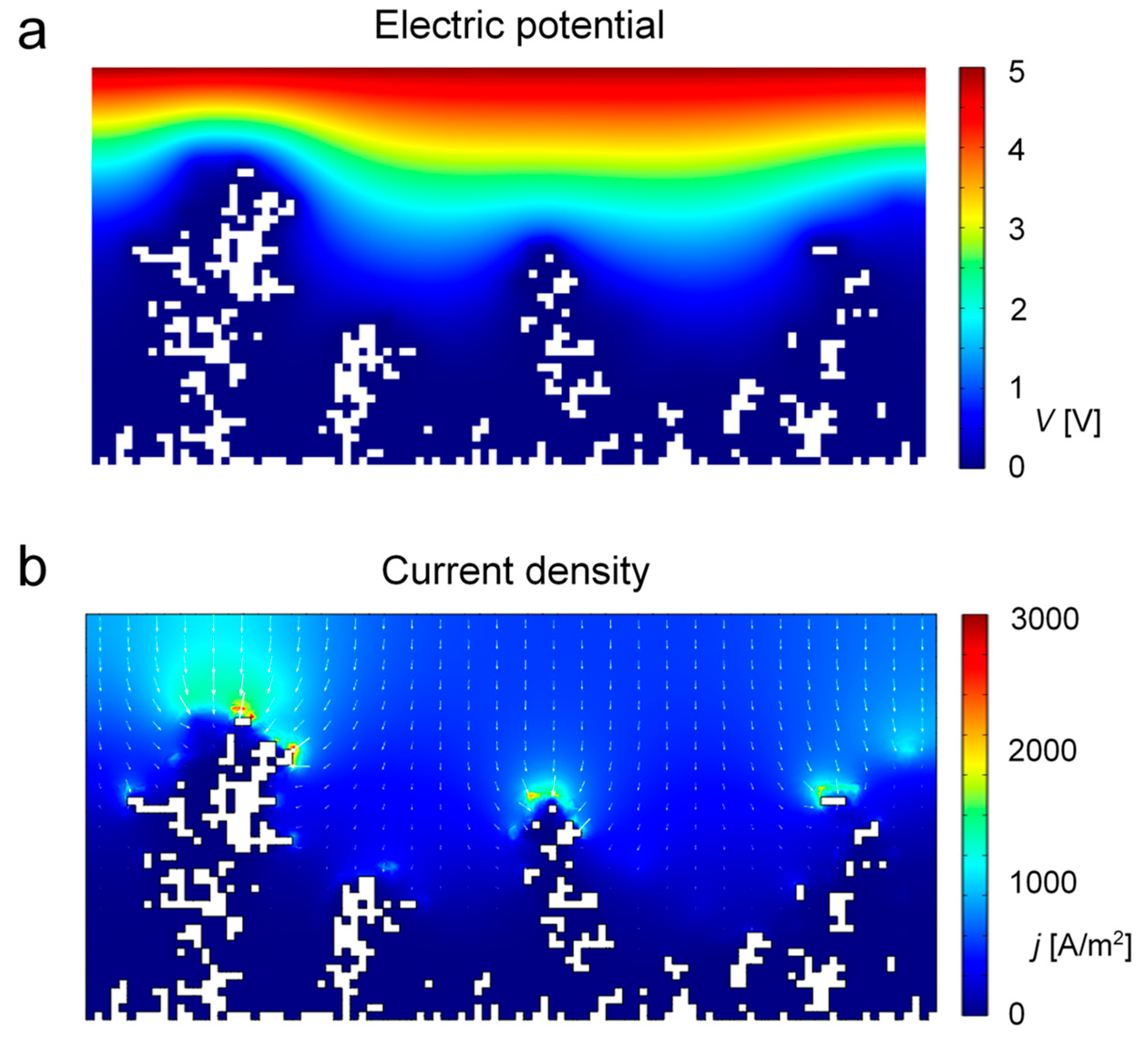

The first step before simulating dendrite growth was to calculate the electric field for the entire simulation domain, i.e., for each three-dimensional dendritic structure, as this data are used as input data for the simulation. A representative example of the calculated electric potential map and the corresponding current density map in a slice across the battery cell with dendrites is shown in

Figure 4. The electric potential map in panel (a) provides a clearer understanding of the preferential direction of electromigration for a hypothetical particle located anywhere in the electrolyte. The potential is the highest near the top where the positive electrode is located and gradually decreases towards the bottom where the dendrites are present and the negative (grounded) electrode is located. The white areas in the maps represent dendritic structures. Areas with intense color changes correspond to areas of high electric fields. As current density is due to uniform and isotropic electrolyte conductivity in the model also proportional to electric field, electric field map (not shown) would be equal to properly scaled current density map in panel (b). The current density map has color-coded intensity, while the vector field indicates the direction of current flow. High current density regions are observed near the dendritic tips, shown in red, where the electric field is the highest. The vectors point towards these high current density regions, demonstrating how dendritic growth causes localized increases in current density and alters the overall current flow within the cell.

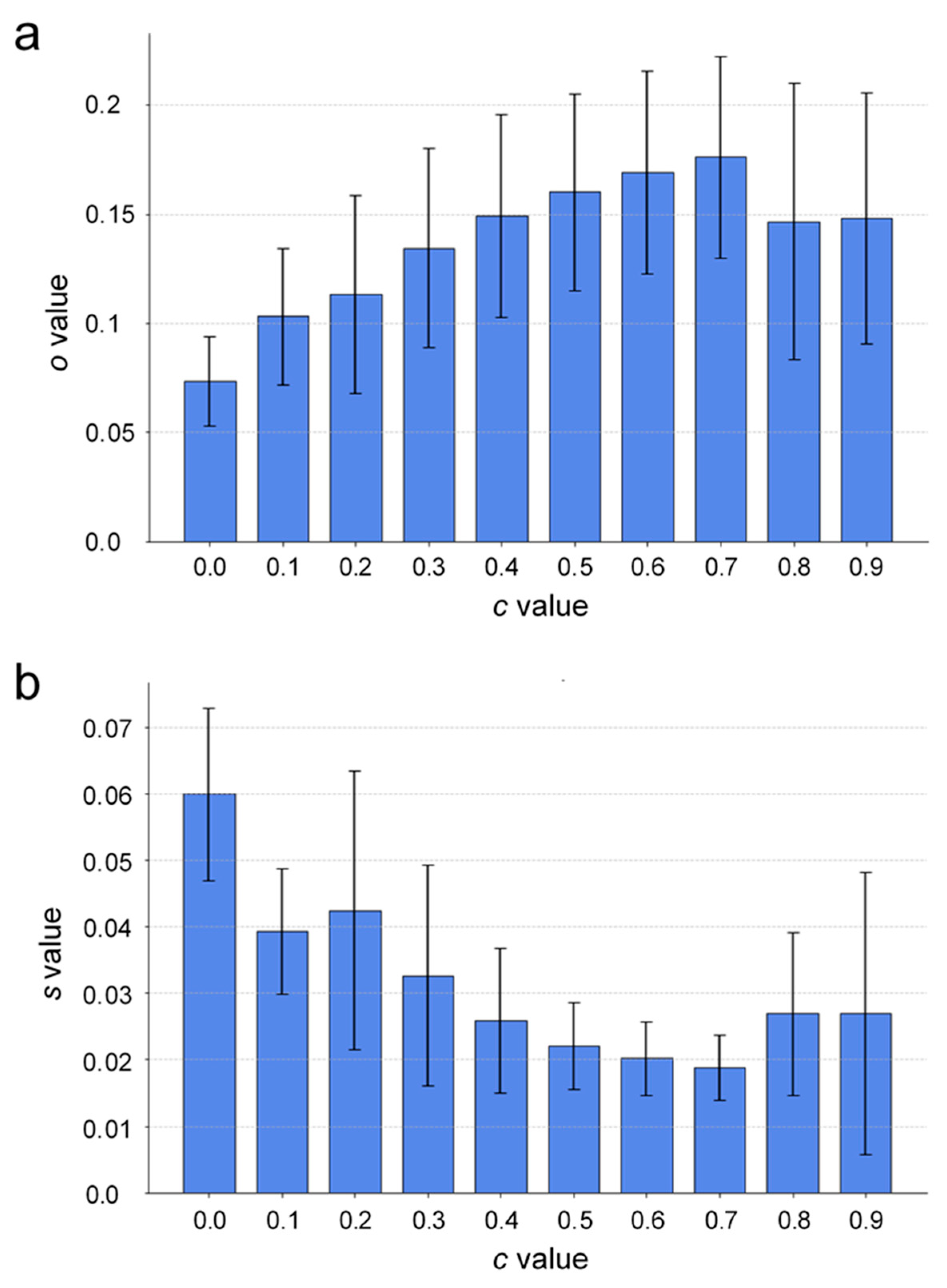

Figure 5 shows two bar graphs that were used to assess how well the simulated dendrites match with the actual ones at different biasing factor values

c using two different metrics. The actual dendrites were extracted from 3D MR images of the battery cell, while the simulation results are represented by 50 simulation runs for the same set of simulation parameters, on which analysis is performed. Panel (a) shows the graph of the mean

o-value in which the fraction of overlap between the actual dendritic voxels and the simulated ones is presented as a function of the biasing factor

c, across all time steps for 50 simulation sets. It can be seen from the graph that the

o-value generally increases with the biasing factor, peaking at around

c = 0.7, and slightly declining after. Panel (b) shows a graph of the mean

s-value, i.e., of the mean voxel displacement as a function of the biasing factor

c, again, across all time steps for 50 simulation sets. The mean voxel displacement corresponds to the average distance from the actual dendritic voxel to the nearest simulated voxel, normalized to the volumetric diagonal of the battery cell. Both

o-values and

s-values have been calculated for each of the individual simulation runs and subsequently averaged across the time intervals, as well as across 50 simulation sets. The error bars show the standard deviation of the distribution of values. It can be seen that the displacement decreases as the biasing factor increases, reaching its lowest value at around

c = 0.7. Lower mean voxel displacement signifies more accurate simulations, with simulated deposition sites closely matching the actual locations of dendrites. For the overlapping ratios (

o-values), the standard deviation increases with

c, while for the voxel displacement (

s-values), the error bars show more variability. Despite this, the lowest absolute deviation and the smallest relative error appears to be around the optimal biasing factor. The graphs of both metrics show that a biasing factor of approximately

c = 0.7 provides the best match between the simulation model and experimental data.

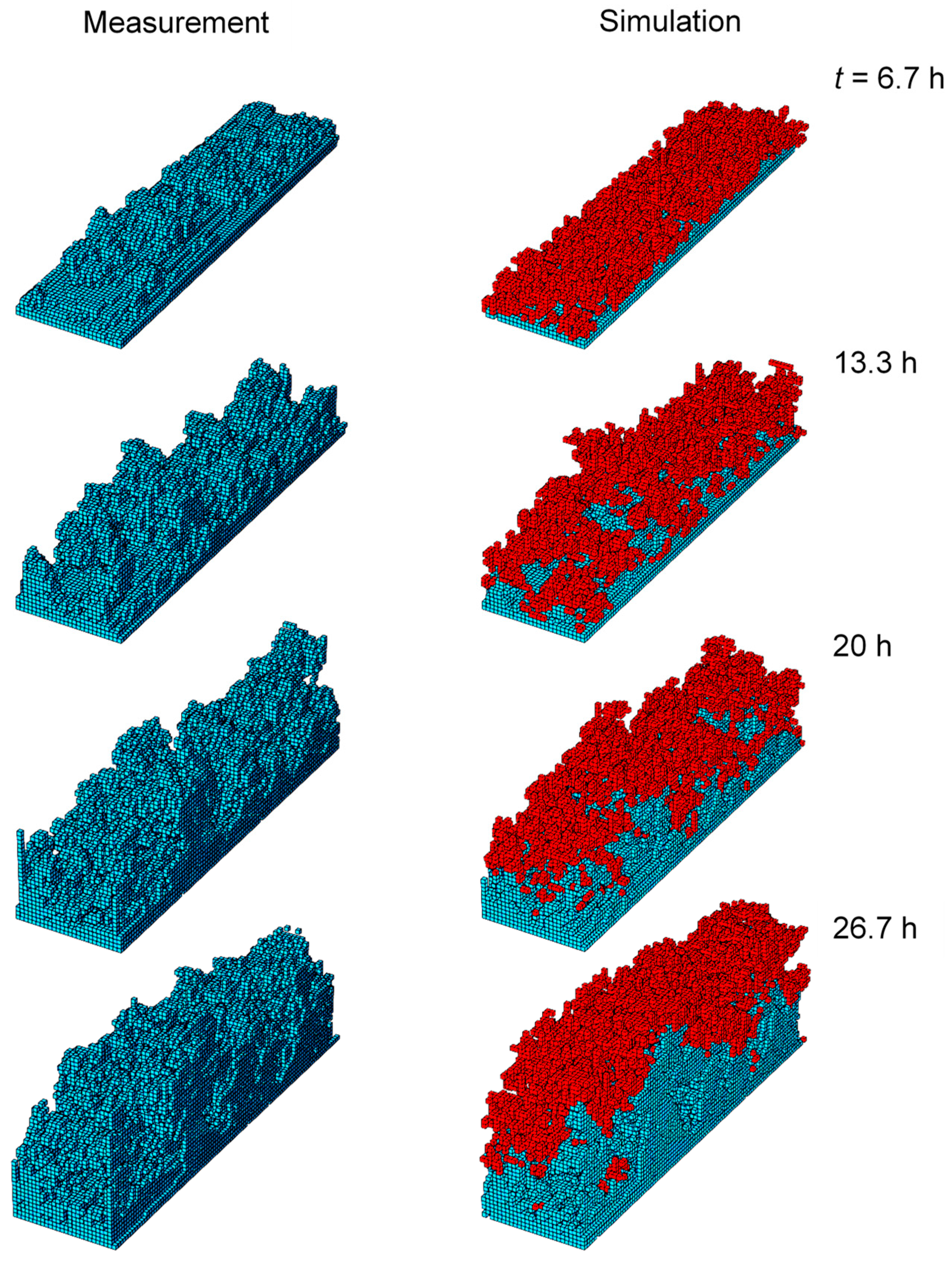

Figure 6 depicts comparison between actual dendritic growth (left column) as measured by sequential 3D MRI and the corresponding simulated predictions (right column) of dendritic growth at matching times and for the biasing factor of

c = 0.7. Each of the shown simulations was randomly selected from a set of 50 simulations for the corresponding time point. The left column shows the actual dendritic growth as measured by MRI, while the right column displays the predicted deposition sites in simulation that are overlaid (in red) on the dendritic growth from the previous MRI image. The predicted deposition sites for all time intervals seem to align well with the measurements, indicating that the simulation adequately captures the development of the dendritic structure for any given time interval. Overall, the comparison demonstrates that the simulation can effectively predict the most likely deposition sites between MRI intervals, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of dendritic growth in lithium metal batteries.

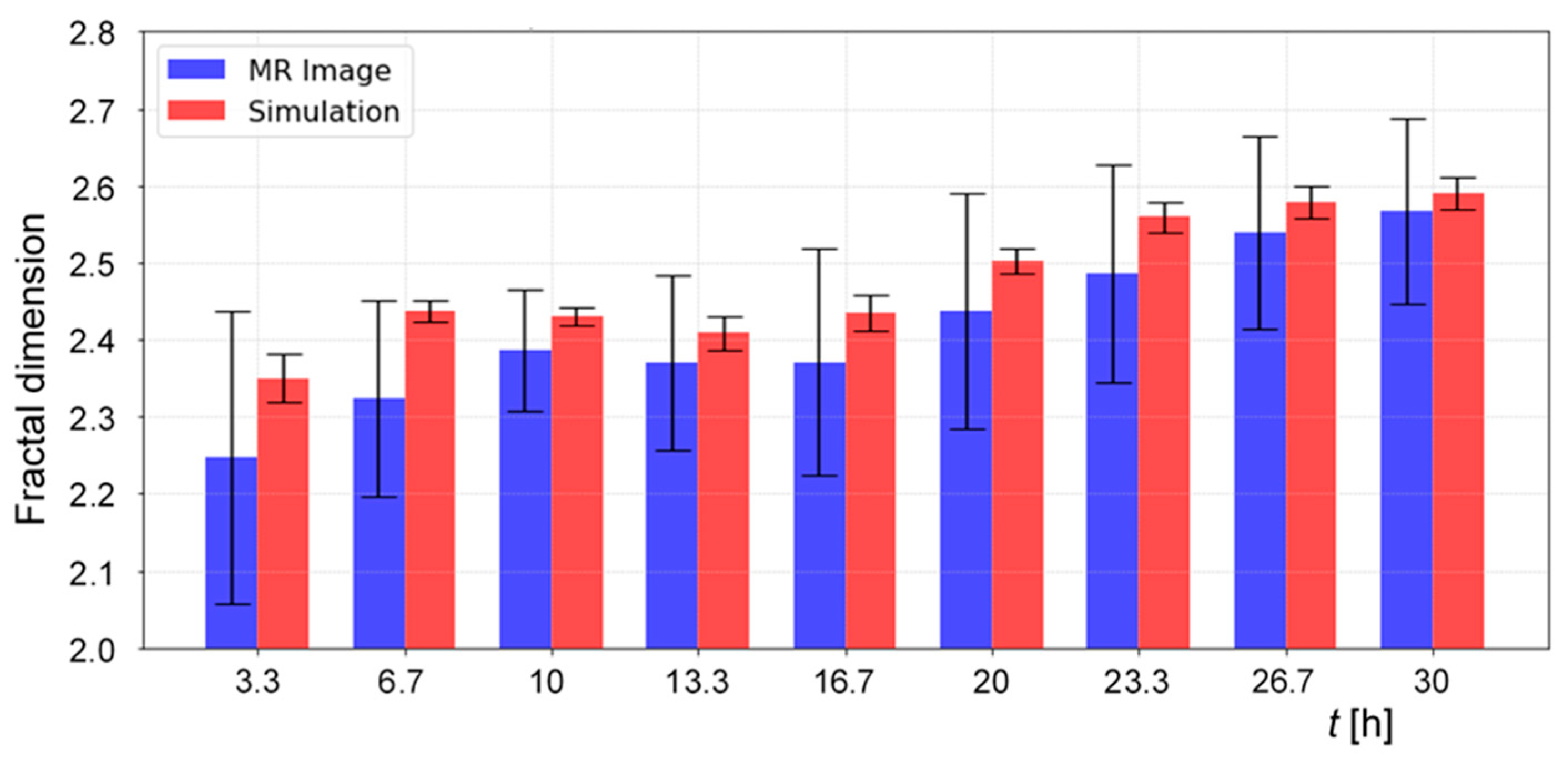

Dendritic growth is also known for its fractal structure. The fractal dimension can be considered as a measure of the complexity and branching nature of the dendritic structures. Therefore, the fractal properties of dendritic structures can be considered as one of the key properties for evaluating the quality of the presented model when simulating actual dendritic structures.

Figure 7 shows a bar graph comparing the fractal dimensions of dendrite growth as a function of time for actual MRI-measured dendrites (blue bars) versus simulated dendrites (red bars). The bars representing the simulation were calculated for the biasing factor of

c = 0.7 and depict the mean fractal dimension across all 50 simulation runs. The error bars in the graph correspond to the standard deviation of fractal dimensions across all simulation runs (in red bars) and correspond to uncertainty in fractal dimension calculation from MRI data (in blue bars). The fractal dimension of MRI measured dendritic structures has an initial value around 2.25, which rises steadily with the deposition of lithium. However, between 10 h and 16.7 h, it plateaus before reaching a final fractal dimension of approximately 2.55. The simulation results align closely with the measurements, staying within the margin of error. For each time point, the majority of the 3D structure remains consistent, with variations only in the latest deposition sites. This consistency implies that the deviations from expected values are minimal, regardless of the biasing factor, especially when averaged over all 50 simulations. Notably, bar heights show strong similarity over time. The chosen optimal biasing factor of

c = 0.7 results in fractal dimensions that closely match the experimental values across the entire range, demonstrating the accuracy of the simulation model.

4. Discussion

Dendrite growth in lithium-ion batteries, particularly in Sand's regime, is significantly influenced by electromigration and ion diffusion. Electromigration drives lithium ions toward locations of the negative electrode with a higher electric field, causing localized ion accumulation and supersaturation at specific points on the surface of that electrode. This localized ion build-up creates nucleation sites for dendrites. On the other hand, the effect of ion diffusion is the opposite, leading to a more uniform ion distribution by migration of lithium ions from regions of higher concentration to those of lower concentration. However, in Sand's regime, the diffusion rate is insufficient to keep up with the rapid deposition of ions at the electrode surface, resulting in the formation of a depletion layer. This depletion exacerbates the conditions for dendrite formation by limiting the availability of lithium ions for uniform deposition and instead promoting the growth of dendritic structures [

17,

18]. The competition between these two processes dictates the rate of dendrite growth: higher electromigration rates accelerate dendrite formation by continuously supplying ions to the growing tips, while inadequate diffusion fails to replenish the depleted regions, further facilitating dendrite elongation. For our simple model, a single parameter, the biasing factor

c, encompasses the ratio of both effects; a higher value of

c represents the domination of electromigration over diffusion. This parameter effectively captures the interplay between electromigration and diffusion, allowing us to predict dendrite growth rates under varying conditions. When

c is high, indicating strong electromigration relative to diffusion, dendrite growth is rapid and more pronounced. Conversely, a lower

c suggests that diffusion is more effective at mitigating the concentration gradients created by electromigration, thereby slowing dendrite formation.

The simple model presented in this study could be of considerable value to other future studies of lithium dendrite growth in lithium batteries, as it provides a computationally efficient method to predict the most likely deposition sites of lithium dendrites in the Sand’s regime. Unlike more complex models, which may require extensive computational resources and detailed parameterization, this model simplifies the problem by using a single biasing factor c that represents the ratio of electromigration to diffusion effects. A higher c value, closer to 1, indicates a greater influence of electromigration, leading to faster and more pronounced dendrite growth, while a lower c value, closer to 0, suggests a stronger role for diffusion in mitigating dendrite formation. This model is particularly advantageous because it balances simplicity and accuracy, making it accessible for rapid iterative testing and refinement. By focusing on the biasing factor, the model can be quickly adjusted to match experimental conditions and predict dendrite growth patterns under various current densities and electrolyte compositions.

In this study, the model’s ability to predict the location and growth rate of dendrites with a reasonable accuracy was validated through comparisons with 3D MRI imaging of actual dendritic structures. It is crucial to note that the characteristic size of features such as electrodeposited columns and branches ranges from 1–3 μm [

24,

36], whereas the MRI's spatial resolution in this study was approximately 156 μm. This disparity means the density of dendrites within each voxel is very low. The MRI signal originates from the electrolyte in the battery, and the impact of presence of metallic objects on this signal is unpredictable due to the complex dependencies on the object's shape and its orientation. Consequently, indirect magnetic resonance imaging is not ideal for characterizing dendrites on a microscopic scale but can still provide an insight in dendritic growth during battery operation on a macroscopic scale. The optimum biasing factor was determined by comparing the dendrites formation form 3D MRI and the corresponding simulation of the same process by comparing the deposition sites and mean displacements, and the quality of the model by comparing the fractal dimensions obtained from MRI and simulations.

From the magnetic resonance images, a clear transition from dense column-like dendrites to highly branched structures is observed over time. This transition is quantitatively supported by the fractal dimension analysis. Fractal dimension in the context of dendrites quantifies the complexity and branching pattern of the dendritic structures. It indicates how the dendrites fill space, with a higher fractal dimension that correspond to more intricate and highly branched growth.

Figure 7 shows an initial plateau followed by a rise, indicating increasingly branched dendrites. Identifying the exact cause of this transition is challenging; however, several contributing factors can be considered. As dendrites grow, local current densities increase, leading to a higher overpotential at the eroding electrode due to the reduced surface area. Concurrently, concentration gradients become steeper as dendrites extend further into the electrolyte. This process is inherently self-accelerating: higher current densities at the tips of dendrites promote further growth, exacerbating the branching and complexity of the dendritic structures.

Some limitations of the model are evident; it is effective only when used alongside an imaging method. On its own, the model has limited utility, especially due to the lack of temporal information. The grid size is also too coarse for discussing "simulation particles"; it is more accurate to refer to deposition locations. However, as shown in both qualitative and quantitative analyses, this simple model has the potential to be a quick predictive tool when combined with a non-intrusive imaging technique, especially with further improvements. One novel aspect of our model is the use of calculated electric fields in conjunction with the DLA algorithm, unlike older models that assume a simple constant electric field. There is potential for further enhancements to improve the model's accuracy or even make it suitable as a standalone tool for electrodeposition. Possible improvements include implementing a multiparticle model with surface diffusion, increasing computational grid resolution, and calculating electrolyte ion concentration and associated overpotentials.